4. Haiǁom resettlement, legal action and political representation

©2024 U. Dieckmann, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0402.04

Abstract

This chapter considers the destiny of Indigenous Haiǁom after they were evicted from Etosha National Park in the 1950s. Differently to communities further west, Haiǁom were not provided a “Homeland” under the separate development policies of the 1970s, but instead were left without any land. In post-Independent Namibia this meant they had no opportunity to establish conservancies under Namibia’s Community-Based Natural Resources Management programme. Some efforts have been made to compensate Haiǁom by purchasing several farms for them in the vicinity of Etosha National Park, although most Haiǁom residents of the park resisted their resettlement, fearing they would lose all access to the park, i.e. their ancestral land. In 2015, a large group of Haiǁom from various areas dissatisfied with the government’s resettlement approach, launched a legal claim to parts of their ancestral land, mainly within Etosha National Park. This chapter outlines these developments, paying attention to the rather ambivalent role played by the Haiǁom Traditional Authority. It also looks at recent developments, arguing for inclusion of Haiǁom cultural heritage in future planning and implementation of nature conservation and tourism activities in the Etosha area.

4.1 Introduction1

Our hearts are in Etosha and we don’t want to be resettled on farms without any acknowledgement that we are the original inhabitants of Etosha. We don’t want our rich cultural heritage to be forgotten and we strongly believe that the Government can benefit in providing space for our rich cultural heritage within the Etosha National Park. Tourists will also appreciate it and the image of the Park will be improved. After having lost the land [a] long time ago and with it our livelihoods, we ask to start to benefit from the Etosha National Park. We hope to start negotiations with the Namibian Government in order to find solutions for all of us.2

This is an extract of a letter from the Okaukuejo Haiǁom Community Group—an interest group of around 60 Haiǁom residing in Okaukuejo within Etosha National Park (ENP)—addressed to the Minister of Environment and Tourism (MET, now Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, MEFT). It was written on 7 July 2010, during the negotiation process of Haiǁom individuals and groups with the Namibian government after the government had purchased the first resettlement farms in 2008. Two years later Haiǁom had already moved to the farms, mostly from the townships of Outjo and Otavi, but very few from ENP. Subsequently in 2015, after years of preparation and initiated by Haiǁom still living in ENP, a large group of Haiǁom from various areas, dissatisfied with the resettlement approach by the government, launched a legal claim to parts of their ancestral land (mainly ENP).3

Around 10,000 Haiǁom currently live in Namibia, mostly in the Kunene and Oshikoto regions, and to a lesser degree in the Ohangwena and Oshana regions.4 Haiǁom in all regions share a high level of marginalisation and poverty, although there are some variations depending on sites and available livelihood options.5 Due to the large-scale dispossession of their land, neither traditional livelihood strategies (hunting and gathering) nor agriculture can play a significant role in sustaining Haiǁom livelihoods. Formal employment opportunities are rare, and dependence on welfare support provided by the state is high; educational levels are generally low, with low literacy levels, especially amongst the older generations (see also Chapter 16).6

Furthermore, Haiǁom feel highly discriminated against by other ethnic groups and disadvantaged in comparison to others: this experience of marginalisation has become an integral part of a shared Haiǁom identity.7

This chapter first explores colonial legacies affecting Haiǁom, especially concerning land dispossession and the intertwined issue of ethnic ascriptions. It will then outline the land situation of Haiǁom in independent Namibia before looking into the vital aspect of community representation. Afterwards, the chapter deals with two approaches towards land restitution: the Namibian government’s provision of group-resettlement farms via the Haiǁom Traditional Authority (TA); and the reaction by Haiǁom who took steps to launch a legal claim to their ancestral land. It will become evident that the issue of community representation is of major significance regarding the successes and failures of both approaches. In conclusion, the chapter points to a couple of interlinked predicaments, which play a constitutive part in the current situation of Haiǁom.

4.2 Colonial legacies

At the onset of the colonial period, Haiǁom lived in north-central Namibia, in an area stretching from former “Ovamboland” in the north, Etosha, Grootfontein, Tsumeb, Otavi and Outjo, to Otjiwarongo in the south. They lived mainly by hunting and gathering, complemented with other small-scale and localised strategies, dependent on the changing demands and opportunities in the area, e.g. mining and trading in pre-colonial and early colonial times (see Chapter 1), seasonal work for farmers, in mines or road construction, and livestock herding (see Chapters 2, 15 and 16). They were also part of an elaborate trade network with their oshiWambo-, otjiHerero- and Khoekhoegowab-speaking neighbours.8 Haiǁom speak Khoekhoegowab, a different language family to Kx’a to which the dialect cluster Ju (spoken by Ju|’hoan and !Xun, two other groups subsumed under the term “San”, formerly “Bushmen”) belongs—these languages are not mutually understandable.9 At times, Haiǁom shared areas of land and resources with neighbouring groups.10

As outlined in Chapters 1 and 2, the eastern part of Game Reserve No. 2 proclaimed in 1907, covered parts of their former area. For almost fifty years after the proclamation, Haiǁom were accepted as inhabitants of the game reserve, while white settlers increasingly occupied the surrounding area. The game reserve became the last refuge where Haiǁom could practise a hunting and gathering lifestyle. But by the end of the 1940s and early 1950s, the Commission for the Preservation of Bushmen did not consider Haiǁom worth being ‘preserved’ due to their degree of ‘assimilation’ with other groups (see Chapter 2).11 They did not, therefore, receive their own “native reserve” in the area they were living in, and were evicted from ENP in the 1950s. After 1954, a few Haiǁom remained in the park as labourers but could no longer live at the various waterholes. Instead they were limited to staff quarters close to the rest camps at Okaukuejo and Namutoni and near the Lindequist and Ombika/Andersson gates to the east and south of ENP, with no land-rights in the park.12 The other evictees became landless farm labourers eking out a living on the settler farms on Etosha’s borders, their labour sustaining a heavily subsidised white-owned commercial agricultural sector.13

With the implementation of the Odendaal Plan, in 1970 “Bushmanland” was created (east of Grootfontein and bordering Botswana), but at some distance (around 300 km) from the area occupied by Haiǁom. Although the Commission for the Preservation of Bushmen also did not consider Khwe as ‘worthwhile to be preserved’,14 the Odendaal Commission recommended a ‘homeland’ for Khwe (‘Barakwengo Bushmen’) in ‘Western Caprivi east of the Okavango River’.15 Yet, this homeland for Khwe was also not realised, because the administration needed to keep strict control over the area in times of anticolonial resistance in Namibia’s north and Angola. Instead, the area became Caprivi Nature Park in 1963, upgraded to ‘Caprivi Game Park’ in 1968,16 and becoming part of Bwabwata National Park in 2007. Its protected area status not only provided a higher degree of conservation protection, but also better options for social control and later military operations.17

In contrast to Khwe and most other San groups in Namibia, the settlement area of Haiǁom was situated in the centre of colonial activities, and they were in contact with representatives of the colonial state, as well as with other Indigenous groups, for some time.18 Von Zastrow, district officer of Grootfontein, thus commented in 1914 on Haiǁom contact with “Bergdamara” (ǂNūkhoen) in the west and “Kung” in the east.19 This contact and “mixing”, coupled with their speaking Khoekhoegowab rather than a San language, contributed to why Haiǁom were perceived as not representing the stereotype of “pure Bushmen”, even as they were considered “Bushmen” because of their dominant subsistence practices and social organisation.20 Their alleged “assimilation” was crucial for denying them any “native reserve” or “homeland” under the German and South African colonial and apartheid regimes. The category ‘Haiǁom’ therefore shared some of the characteristics of what Eriksen calls a ‘liminal category’:

[f]irst of all, the existence of ethnic anomalies or liminal categories should serve as a reminder that group boundaries are not unproblematic. These are groups or individuals who are “betwixt and between”, who are neither X nor Y and yet a bit of both. Their actual group membership may be open to situational negotiation, it may be ascribed by a dominant group, or the group may form a separate ethnic category.21

In addition, while in pre-colonial and early colonial times land had been shared between different groups and different land use systems,22 during colonial times, land use became increasingly exclusive (see Chapters 1 and 2). Part of the land inhabited by Haiǁom became allocated to white settlers and fenced off, and part of their land became allocated to wildlife as ENP, entirely fenced in. Little land was left, which they continued to share with other human and beyond-human inhabitants (e.g. in former “Ovamboland” and Mangetti West), although on unequal terms. At the time of Namibia’s Independence in 1990, then, Haiǁom found themselves altogether dispossessed of their land.23 They had no access to communal lands24 and therefore no option to establish conservancies (see Chapter 3),25 to keep enough livestock to sustain themselves, or to engage in agriculture. They continue to live scattered over northern-central Namibia, a factor impeding the establishment of a powerful representational organisation (see Section 4.4).

4.3 Current land situation

Following Namibia’s Independence in March 1990 and the first National Conference on Land Reform and the Land Question in 1991, the government took measures to redistribute the country’s land and facilitate land reform. Although the government made some attempts in the 1990s and early years of the new millennium to address the landlessness of San communities, including Haiǁom, these have not made a fundamental difference to their situation26 (also see Chapter 16). Worse still, Haiǁom who had de-facto land-rights (e.g. those living in Mangetti West, see below) faced further land encroachment by other ethnic groups.27

Concerning the various land-tenure systems under which Haiǁom are living, the situation of Haiǁom regarding land can be outlined as follows:

- Haiǁom in ENP have no de-jure land-rights;

- Haiǁom who live and work on commercial farms have no rights to such land at all;

- Haiǁom whose farm employment ceases have no land to call their own, and usually end up in informal settlements in towns in the vicinity, or with family on resettlement farms (many of which are already overpopulated). Most of the Haiǁom in urban areas (e.g. in Outjo, Otjiwarongo or Tsumeb) have no tenure security and are living in informal settlements where residents are regularly threatened with eviction. The communal land in the north where Haiǁom are living as a minority among the large majority of oshiWambo-speaking residents falls under the traditional authorities (TAs) of the respective oshiWambo-speaking groups;28

- in the first 15 years after Independence, some Haiǁom were resettled on group resettlement farms under the national resettlement programme by the Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation (MLRR, since 2015 Ministry of Land Reform, MLR).29 Of the approximately 55 group resettlement farms, about seven of them (Excelsior, Oerwoud, Tsintsabis, Kleinhuis, Namatanga, Queen Sofia, Stilte) have considerable numbers of Haiǁom beneficiaries. However, a high level of dependency on government support exists on these farms, and self-sufficiency is unlikely to be achieved in the near future.30 Furthermore, it is unlikely that any of the resettled Haiǁom beneficiaries have ever received any title deed in their individual names;

- the Haiǁom community of Farm Six in the Mangetti West Block (the area around ‘Farm Six’ east of ENP, see Figure 4.1 in Section 4.5) faces even worse problems regarding access to land.31 For a long time, Haiǁom there had de-facto land-rights and could hunt and, even more so, gather bushfood in the area. These activities came under pressure when the Namibian Development Corporation made four farms in the Mangetti area available for the relocation of oshiWambo-speaking cattle owners who had lost a court battle regarding their illegal cattle grazing activities in western Kavango Region. Although this was meant to be a temporary solution, in 2010 the Owambo farmers’ stay was extended, with their cattle grazing in the area where Haiǁom used to have temporary camps to hunt and gather bush food.

4.4 The issue of community representation

Given this shared experience of land dispossession and marginalisation, Haiǁom see an urgent need to have a “representative” to negotiate on behalf of the Haiǁom with the state.32 In this regard, the most powerful institution is currently the Traditional Authority (TA), provided for by the Traditional Authorities Act (25 of 2000). The main functions of all Namibia’s TAs, as established by the act, are: to cooperate with and assist the government; to supervise and ensure the observance of customary law; to give support and advice, and disseminate information; and to promote the welfare and peace of rural communities.

According to the Act,

“traditional community” means an indigenous homogeneous, endogamous social grouping of persons comprising of families deriving from exogamous clans which share a common ancestry, language, cultural heritage, customs and traditions, who recognises a common traditional authority and inhabits a common communal area, and may include the members of that traditional community residing outside the common communal area.33

This is where the next predicaments come into play: strictly speaking (and disregarding the other questionable phrasing in this definition, e.g. ‘homogeneous’, ‘exogamous clans’), Haiǁom are not a ‘traditional community’ in the terms of the act. Firstly, as has been outlined above, they do not inhabit ‘a common communal area’; and secondly, they do not recognise a ‘common traditional authority’ (see Section 4.6). The Traditional Authorities Act (TAA) is perceived by some to apply as a model the traditional system of oshiWambo-speaking groups (who constitute over 50% of the Namibian population); a model that is characterised by a hierarchical authority structure with a single representative leader for a large group.34 This model does not necessarily work well for all leadership structures in the country: San communities, in particular, find it difficult to use this institution for their own benefit.35 For San communities, it would be more correct to talk about ‘neo-traditional authorities’,36 as it seems that in the past they had no ‘traditional’ hierarchical authority structures, and neither ‘chiefs’ (as ‘supreme traditional’ leaders) nor a ‘Chief’s Council’ or a ‘Traditional Council’.37 Nevertheless, Haiǁom perceive the TA institution as being an important tool for making their voices heard.

Despite these issues, the official Haiǁom TA under Chief David ǁKhamuxab was recognised under the act by the government on 29 July 2004. At this time, some Haiǁom groups already rejected the recognition claiming that the ‘so-called Traditional Authority was nothing but a SWAPO structure’38 and that the TA had not been elected by the Haiǁom community.39 During the following years, most of the development targeting the Haiǁom was channelled through the Haiǁom TA. Currently, dissatisfaction with the chief is evident in most Haiǁom communities, and there is a division amongst Haiǁom between supporters and opponents of the chief.40 Major concerns include the absence of proper elections to appoint the chief, a lack of information and transparency, corruption and favouritism, and therefore a general lack of representation of Haiǁom community interests.41 This conflict is a major impediment to development.42 In recent years, the government has become increasingly aware of this challenging situation, and of the complexities regarding the role Chief ǁKhamuxab plays in community development efforts43 (also see Chapter 16).

These issues can be understood as a conflict between the traditional structures and processes of Haiǁom and those defined by the TAA. The Act stipulates that TAs should be designated in accordance with the customary law of the applicable traditional community. However, unlike the customary laws of many other traditional communities in Namibia, the customary law of Haiǁom (like that of most San communities) does not make any provision for the establishment of overall authorities.44 Furthermore, whereas local and national political leaders come to power through elections, traditional leaders are generally appointed according to customary law, with little transparency in the appointment process. The system is, therefore, open to abuse. In some cases, the process through which a TA comes to power is obscure, and it is often said that party politics have played a role.45 Furthermore, the lack of powerful individual leaders in traditional Haiǁom society means that the TAs lack internal role models to emulate in their own leadership positions. Training for Namibian TAs, monitoring of their performance, and the requirement of accountability are virtually non-existent. Another difficulty is posed by the fact that all TAs in Namibia receive monthly remuneration, as well as a 4x4 vehicle and other provisions from the government and various donors. For many reasons, this access to money, transportation and other benefits is a source of conflict in a community like the Haiǁom, whose traditional values were strongly egalitarian.

Independently of the TA, Haiǁom also attempted to establish several other community-based organisations over the years to either represent specific segments of Haiǁom or the overall Haiǁom community. None of these organisations proved capable of providing Haiǁom with a powerful common political voice.46 As with the TAs, one of the biggest obstacles in the path of any overall Haiǁom organisation is that the former egalitarian structures do not provide for any kind of formal “authority” empowered to speak on behalf of the people. The legacies of colonial history, above all land dispossession (resulting in their geographical scattering), and marginalisation (implying low levels of education and the lack of money and transport), are additional challenges.47 Most importantly, however, and as will become clear, the government is hesitant to accept any other structures than the TA for Indigenous communities to negotiate with.48

4.5 The resettlement strategy of the Namibian government

Awareness of the marginalised and partly desperate situation of the San in Namibia increased significantly with the establishment of the San Development Programme (SDP) under the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM) in 2005. This programme can be attributed to the then Deputy Prime Minister, Dr Libertina Amathila, who was shocked about the living conditions of San in Namibia after a visit to various San communities in the country. She then focused on the “development” of the San during her tenure as Deputy Prime Minister (2005–2010).49 The SDP aimed to ensure integration of San into the mainstream of Namibia’s economy. In 2007, the programme was extended to cover other marginalised communities including Ovatue, ovaTjimba and ovaHimba. The programme was supported by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) from 2008–2013, trying to promote Convention 169 on the Rights of Indigenous and Tribal Peoples. The ILO perceived the existence and potential of the SDP as a platform for promoting Convention 169 in the southern African region as a whole.50 In 2009, the programme was transformed into the Division of San Development (DSD), still under the OPM.51 In 2015, the DSD was renamed the Marginalised Communities’ Division (MCD) and shifted to the Office of the Vice-President (OVP). Around 2019, it was merged with the Division of Disability Affairs as the Division of Disability Affairs and Marginalised Communities, within the Ministry of Gender Equality, Poverty Eradication and Social Welfare.52 The personal initiative of the former Deputy Prime Minister and the ILO involvement were important drivers of the programme in the initial years but the programme lost momentum over the years, perhaps connected with the Namibian government’s lack of recognition of specific rights of “Indigenous Peoples”.53

The urgent issues acknowledged under the programme included the impact of colonial land dispossession and the current landlessness of San communities, as well as education and unemployment. The programme responded to the land issue by donating resettlement farms to San communities in various regions. Despite well-known challenges associated with group resettlement,54 this model continued to be employed for San resettlement, although it had been stopped for the resettlement of other poor and landless Namibians.55

Dissatisfaction with the collective resettlement of San people on resettlement farms—while other Namibians were resettled as individuals—was also expressed by the Deputy Minister of Marginalised Affairs, Royal |Ui|o|oo (himself a Ju|’hoan), in a 2018 article in The Namibian:

[t]here is a concept of saying it’s a group farm. Why is it always the marginalised groups who are being grouped to make things difficult for them? Why can’t the marginalised, even just one of them, be given a full farm instead of a group thing?56

Some group resettlement farms were earmarked specifically for the Haiǁom. This was also related to the centenary celebrations of ENP in 2007: the government could not ignore the fact that Haiǁom had lost their land due to the establishment and development of the ENP, meaning that the centenary was not a celebratory event for them.57

The MLR had already carried out farm assessments and identified potential farms for purchase before 2007. A consultant was contracted to conduct research on behalf of the MET, resulting in a project implementation plan for resettlement of Haiǁom and recommending the establishment of conservancy-like institutions (see Chapter 3):

[t]he overall approach of the project is to address these problems through resettlement of the San living in the park and those living at Oshivelo on land purchased adjacent to the ENP. The aim is then to assist the resettled people to develop sustainable livelihoods on the land through a diversity of land uses, particularly involving wildlife and tourism, based on the communal area conservancy approach.58

As mentioned in the document, the primary target group for resettlement was the Haiǁom still residing within ENP, of whom only a minority were employed by the MET and Namibia Wildlife Resorts (NWR),59 with the rest retired or unemployed, and staying with their employed relatives. Another target group for resettlement were Haiǁom staying in Oshivelo, a squatter camp at the north-eastern border of ENP (where many former Etosha evictees were residing).60 The plans envisaged that farms be bought for resettlement by the MLR on the eastern side of the park (close to Oshivelo) and at the southern border of the park (close to the Anderson gate and Ombika). The resettled Haiǁom should be assisted to develop sustainable livelihoods on redistributed land through a variety of strategies and land uses, involving the utilisation of wildlife, tourism, and—as in the case of communal areas—the creation of conservancies. There were also discussions about Haiǁom gaining access in the form of concessional rights over specific sites in ENP which were of particular cultural importance to them.61 It is noteworthy that in his report the consultant stressed that there was a considerable need for proper planning at different stages of the project, including a need to carry out certain feasibility studies before some of the proposed activities could be initiated. Moreover, he warned that if the project moved too quickly so as to get results on the ground, then the Haiǁom community would not properly benefit from the project.62 Additionally, the necessity to provide sound capacity-building programmes was stressed. It was anticipated that the project would require commitment from the government and donors over a period of at least 10 years to provide the Haiǁom beneficiaries with sustainable livelihoods based on sound land management, the development of productive businesses and partnerships, and good governance.63

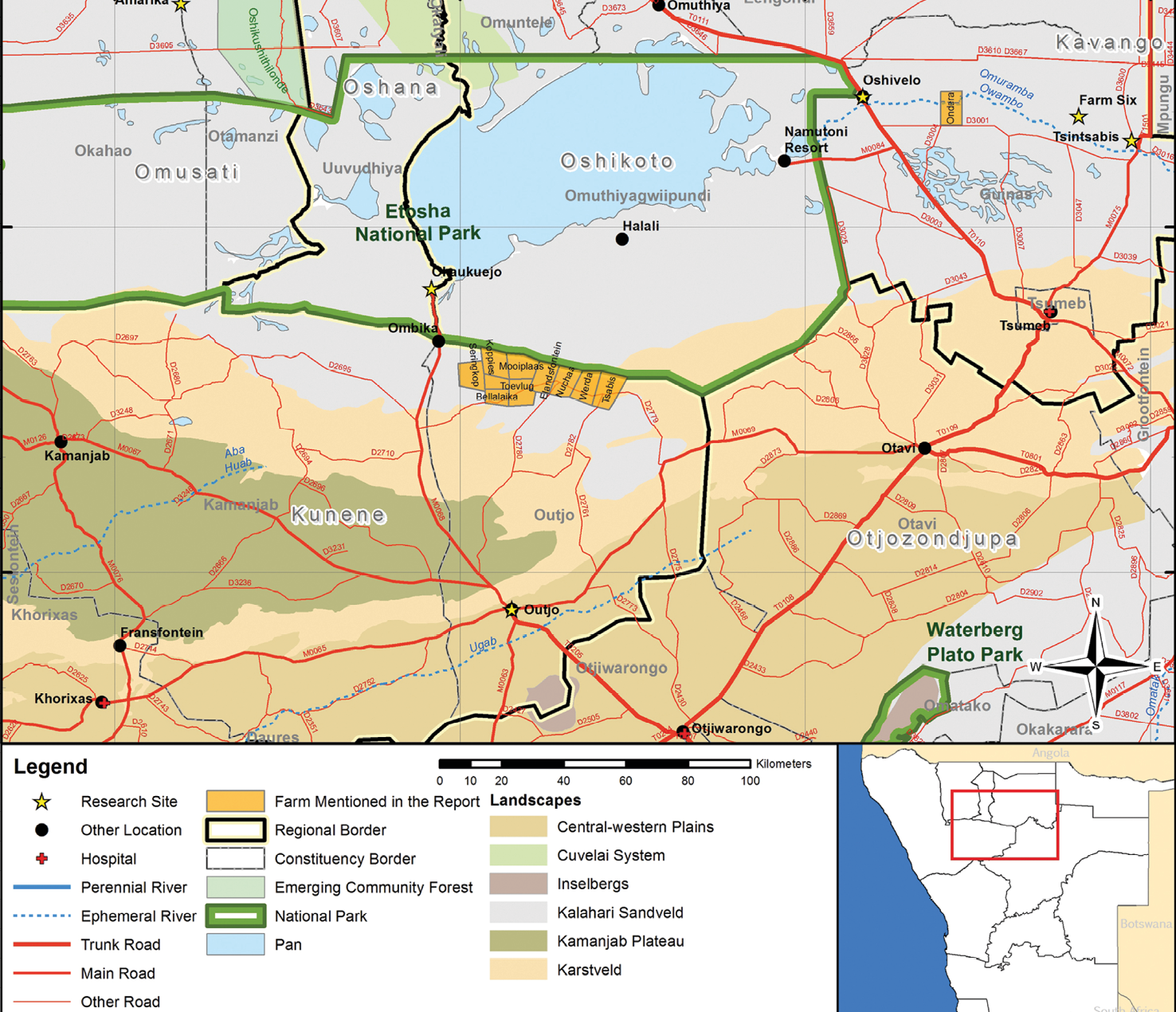

In November 2008, the first farms (Seringkop and part of Koppies, with a total area of 7,968 ha on the southern border of ENP) were officially handed over to the Haiǁom TA. It was the first time in the country’s post-colonial resettlement history that a resettlement farm had been handed over to a particular ethnic group.64 On the one hand, this could be interpreted as a deviation from relevant national policies on land and resettlement, but on the other hand, the Haiǁom, as San, are recognised as a primary target group of the Resettlement Programme. Since 2008, the government has purchased five more farms close to the southern border of ENP specifically for Haiǁom: Bellalaika (3,528 ha), Mooiplaas (6,539 ha), Werda (6,414 ha), Nuchas (6,361 ha) and Toevlug (6,218 ha). In early 2013, Ondera/Kumewa (7,148 ha), a combined farming unit around 30 km east of Oshivelo, was purchased (see Figure 4.1).65

Most of the Haiǁom residents in ENP resisted their relocation, fearing they would lose all access to the park once they had agreed to be resettled on the farms: their priority was to gain employment in the park and to stay there. Since 2012, however, a small number of Haiǁom from ENP agreed to move to the farms, as the MET promised to provide them with housing and other support.66 After the farms Ondera/Kumewa were handed over to the Haiǁom TA in 2013, Haiǁom from Oshivelo and surrounding commercial farms and other resettlement farms started moving there.67 As they had not been living in ENP for some time, there was no notable resistance by these people to move to the farms.

Fig. 4.1 Haiǁom resettlement farms in 2014. Source: © Dieckmann (2014: 174), reproduced with permission,

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

By September 2012, around 690 Haiǁom, including the chief, were living on the seven resettlement farms south of Etosha.68 The fact that a Land Use Plan and Livelihood Support Strategy,69 followed by a Strategy and Action Plan,70 was released only in 2012 indicates that there had been little coordinated planning beyond land purchases in the early stages, standing in stark contrast to the measures proposed in the initial consultant’s report.71 The reports mentioned above had been commissioned by Millennium Challenge Account—Namibia (MCA–N),72 in response to a request from the then MET for planning assistance. Access to the resettlement farms was managed by the Haiǁom TA. The chief received resettlement requests from local Haiǁom people and then provided them with places on the resettlement farms once the farms had been purchased and handed over to the TA. This was a matter of concern for many Haiǁom, who felt that many of those people first resettled were family of the chief, or closely connected to him.

Pension money and food aid were the main livelihood strategies for farm residents. Transport to Outjo for accessing pensions was a problem, however, given that this town is at least 90 km away mostly by gravel road.73 Less than 15% of Haiǁom farm residents owned livestock. Income-generating activities, such as the exploitation of natural resources (firewood, mopane worms—edible caterpillars of Gonimbrasia belina, and medicinal plants), as well as the production of crafts, were relatively undeveloped.74 Gardening (either communal or individual) only took place on a small scale. The resettlement farms received support through a variety of government agencies (e.g. in terms of infrastructure, financial and technical support) and the Namibian—German Special Initiative Programme.75 Some improvement concerning infrastructural development on the farms has taken place over the years (e.g. a primary school and clinic at Farm Seringkop).76

Since the early stages of planning it was additionally envisaged that Haiǁom on the resettlement farms should be enabled to gain additional income through the granting of a tourism concession to the specific area around the waterhole !Gobaub in ENP (see Chapter 15). In 2011, a feasibility study was conducted to assess this option.77 Extensive debate took place between the MET and MCA–N during 2011 and 2012 regarding the type of legal entity such a concession could be granted to, with the latter emphasising the need to have a democratic institution in place. It was most probably the involvement of MCA–N, whose representatives were aware of the internal conflicts around the TA and understood that the community, therefore, had no single representative body, which led to the establishment of an association to operate as “the concessionaire”, instead of the Haiǁom TA.78 Eventually, in September 2012, the !Gobaub Community Association was established to oversee the wildlife tourism concession around the !Gobaub area. The constitution of the association, however, was drawn up by lawyers in Windhoek without proper consultation or participation of the potential members, and without taking the realities on the ground into account.

In restricting the possible membership in the association to Haiǁom residents on the resettlement farms, the MET decided that potential benefits from the concession should only be available to them. This meant that those who had decided to stay in Etosha, as well as other Haiǁom who had lost land during the colonial period but did not stay on the resettlement farms, were excluded from any benefits arising from the !Gobaub concession. This situation arose even though several consultancy reports,79 including the Report on the Strategy and Action Plan for the Haiǁom Resettlement Farms compiled in September 2012, recommended a broader approach to membership: ‘[w]e believe that there is considerable merit in including the Etosha Haiǁom in the membership of the !Gobaub Community Association’.80 This recommendation was based on three arguments:

- First, the Etosha Haiǁom have considerable knowledge of park and tourism management and the Park’s landscape and wildlife. They can bring this knowledge to bear in the development of tourism plans and programmes, including cultural programmes.

- Second, many of the Haiǁom who chose to remain in the Park will do so because they earn livelihoods as Park employees or have family members who are employed in formal or informal livelihood activities. They should not be disqualified from membership in the Association simply because of the need to continue to earn a Park-based livelihood.

- Finally, by including Etosha Haiǁom in the Concession, many of the social and political divisions likely to result from their exclusion would be alleviated.81

These recommendations were ignored, however, and the concession agreement was signed between the MET and the ‘!Gobaub Community Association’,82 meaning that only people from the resettlement farms, as members of the association, were to become beneficiaries of the concession. As with the drafting of the constitution of the ‘!Gobaub Community Association’, participation in drafting the contract by members of the association—let alone by the rest of the Haiǁom—was no doubt rather limited. Their absence becomes evident when reading the agreement. It is phrased in legal language, difficult for many to understand, let alone people with limited reading skills and proficiency in formal English.

Notably, in Annexure 3 of the Head Concession Contract, Haiǁom, as part of the San, are portrayed as the ‘Survivors of the Late Stone Age Era’ and as ‘a “living link with prehistory”’ constituting ‘extant receptacles of a rich source of ancient Indigenous knowledge, traditions and customs’.83 The rights of the concessionaire are limited or impractical.84 It should also be noted in this context that the idea of building a lodge at !Gobaub for the exclusive benefit of Haiǁom was originally developed by the residents in ENP (see Section 4.6).85

Currently, the Division of Disability Affairs and Marginalised Communities within the Ministry of Gender Equality, Poverty Eradication and Social Welfare coordinates and leads the post-resettlement support.86 Yet, even 11 years after resettlement, the residents did not see the desired improvements in their livelihoods. In 2019, residents who had moved to the farms from ENP complained about the lack of job opportunities on the farms and considered moving back to Okaukuejo. Furthermore, predators preying on livestock, especially hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) and lions (Panthera leo) breaking through the ENP fences, remained a problem. Some residents collected firewood or produced charcoal for sale, while a few women received sporadic payments from working on a gardening project. The residents reported not having any papers testifying to their rights to land, and not feeling secure about their right to stay on and use the land.87

In short, land acquisition and resettlement planning and strategy on the resettlement farms south of Etosha were of a piecemeal nature, and the resettlement of Haiǁom was anything but a well-planned and coordinated process. The crucial question of livelihood sustainability was not adequately addressed. Due to the remoteness of the farms, employment opportunities, piece work options, and options to engage in small businesses, were more limited than in larger settlements and towns such as Okaukuejo, Outjo or Otavi. It appears that Haiǁom became even more dependent on government aid on the resettlement farms than they had been beforehand during times when they lived in towns or in ENP. Furthermore, government participation and consultation initiatives were mainly facilitated through the Haiǁom TA, which, as it turned out, complicated issues further and led to more divisions in the community (also see Chapter 16).

Concerning the tourism concession, no tangible progress has been made either. In 2017, The Namibian reported that no investor had been found, although there had already been proposals by Ongava Game Reserve, Namibia Wilderness Safaris and Namibia Wildlife Resorts,88 a situation linked to various factors. The internal disagreements regarding who should negotiate on behalf of the Haiǁom is certainly one of them. While the chief would have liked to take a leading role in this, both the MET and the !Gobaub Community Association persisted in making the association the sole concessionaire; although it appears that this situation hampered negotiations with several tourism companies who expressed an interest in investing and building a lodge at the farm Nuchas. Eventually, on 3 June 2021, an operator contract was signed between Ongava Game Reserve (Pty) Ltd and the !Gobaub Association.89 Since then, however, not much has happened.90 As a result, no benefits have yet been derived from the concession for the Haiǁom.

At first sight, it appears that the situation at the farms to the east of ENP, i.e. Ondera/Kumewa (see Figure 4.1)—handed to Haiǁom in 2013—is better than that on the farms south of ENP. In 2016, a reporter from The Namibian newspaper even referred to Ondera as ‘Namibia’s resettlement jewel’.91 The number of households at Ondera has grown considerably since the early stages of resettlement. In 2016, around 120 households were reported to be living there:92 by 2018, the Deputy Minister of Marginalised Communities, Royal |Ui|o|oo, mentioned 430 households;93 a resident speaking to the Legal Assistance Centre (LAC) team in 2019 estimated around 460 households to be living there.94

At the time when the farm became a resettlement project, it had fully operational dry and irrigation farming systems in place, and agricultural activities were ongoing. The income from sales was kept in a trust account, and people involved in the project were getting a monthly allowance of N$1,200 each from the government. Additionally, between 2014 and 2018 Ondera received support from Namsov Fishing Enterprises (Pty) Ltd in the form of livestock, allowances, a 4x4 vehicle, a tractor and farming implements.95 Still, in 2019, the main sources of income at Ondera were pension money and the garden project. Residents would prefer to have individual plots, rather than the community cultivation project. The allowances and food aid paid by the government were reported to be irregular. Residents were told that the farm’s carrying capacity for all types of livestock was 400. With 460 households living at Ondera, this would amount to less than one head of livestock per household, which cannot possibly represent a significant source of income or food.96

The nearest clinic is at Oshivelo, about 45 km away; there are hospitals at Tsumeb and Oshivelo, and two health workers are working at Ondera. Food is also mainly bought at Oshivelo or Tsumeb but transport remains a problem.97 An Early Childhood Development Centre and a primary school are at Ondera.98 Secondary schools are located at Ombili, Oshivelo and Tsumeb. Residents mentioned the lack of job opportunities as a major stumbling block preventing the completion of schooling, mainly because people are pessimistic about finding work after doing so. Irregular electricity supply and transport appear to be major problems at Ondera and residents complained that the government did not always react and assist when problems, e.g. concerning electricity, were reported. Residents felt insecure regarding land-rights and reported that government officials had told them to leave when they were not willing to work on the farm.99 In sum, compared to the farms south of ENP, Ondera would at first sight seem to have better prospects for development. Considering that 460 households with an estimated population of 2,000 already reside at the farm, however, farming activities (livestock and cultivation) can hardly meet the needs of the inhabitants. The distance to the nearest towns is a major obstacle that limits other income-generating activities.

To date, Haiǁom have been resettled on eight farms with about 44,206 ha of land under the government programme for marginalised communities. Dependency on government support is high, and opportunities to develop self-sustainable livelihoods on these farms seem to be low in the absence of strong and coordinated efforts to establish diversified livelihood options moving beyond small-scale gardening and small-scale livestock production.

4.6 Legal action by Haiǁom: Reclaiming Etosha and Mangetti West

A group of Haiǁom within Etosha, the Okaukuejo Haiǁom Community Group mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, became increasingly unsettled with the developments regarding the resettlement farms south of Etosha after the first farms were handed over to the chief.100 They were reminded of the eviction of Haiǁom in the 1950s and feared that remaining Haiǁom still living in ENP would now also be expelled from their ancestral land. Furthermore, having lived and worked in Etosha for most of their lives, they had hardly any experience in farming and no spiritual connection to the land outside the park (see Chapter 15). Living on a resettlement farm did not seem like a viable option to them. In 2010, they held a meeting with the Prime Minister to raise their concerns.101 The Prime Minister referred them to the then Minister of MET, Netumbo Nandi-Ndaithwa, to discuss the matter. Her opinion was that it was in the Haiǁom’s best interests to move out of Etosha.102 She also visited Okaukuejo to present the government’s plans regarding resettlement and possibly a concession.

The Okaukuejo Haiǁom Community Group felt that their concerns and demands were not being taken seriously, and wrote another letter to the Minister of MET. The extract quoted at the beginning of the chapter is from this letter, in which they also clarified that they did not recognise Chief David ǁKhamuxab as their chief, because he had not been democratically elected by the Haiǁom and was not working on their behalf. For these reasons they requested new elections of a Haiǁom TA. They wanted the government to recognise that Haiǁom are the indigenous inhabitants of ENP and to respect their cultural heritage there. They, therefore, wished to take part in decision-making processes regarding the development of ENP. They stressed that they did not want to be resettled on farms and that they had never requested resettlement farms. They further requested that the government should hand over !Gobaub as a cultural heritage site to the Haiǁom. Furthermore, they asked the government to take affirmative action to address the high level of unemployment amongst Haiǁom youths within the park, pointing out that members from other ethnic groups, originating from other areas, would nowadays get preferential employment in the park.103

The MET did not react to the letter, and the Okaukuejo Community Group decided to ask the LAC for legal assistance with respect to ‘taking government to court’.104 During the following months, on advice of the LAC, the Etosha Haiǁom Association (EHA) was established in order to have a legally recognised voice which could act independently of the TA. Importantly, according to its constitution, the membership of EHA was open, subject to certain conditions, for any person who shared a common cultural identity with the Haiǁom people or the Haiǁom traditional community. The founders of the association travelled to other Haiǁom communities to introduce the organisation and its aims, to secure support for it, and to extend the membership to Haiǁom living outside ENP.

In April 2011, the committee of the EHA wrote another letter to the Minister of Environment and Tourism and other stakeholders to call a stakeholder meeting to discuss their concerns to reach a consensus on the way forward.105 The meeting took place on 30 May 2011 and was attended by representatives from the MET, including the Minister, members of the Haiǁom TA (including the chief), members from MCA–N and several NGOs. It is worth describing the meeting in some detail, as it might have been a turning point in the Haiǁom strategy to be heard.

At the meeting, the MET Permanent Secretary, with the additions of the MCA–N representative, outlined a prosperous Haiǁom future on the resettlement farms with ample support and development (i.e. agriculture, infrastructure, wildlife). But she also stressed that the Haiǁom would need to move out of ENP to the farms, and remarked: ‘[y]ou would still be with the wildlife of Etosha but only on the other side of the fence!’106 The EHA attendees were not convinced and repeated their claims and demands. The EHA Chairperson, the late Kadisen ǁKhumub, gave an emotional speech (which was translated) and asked for recognition of the Haiǁom residents in ENP as an integral part of the park. He requested affirmative action for their children and grandchildren regarding employment in the park and thereby the right to stay in ENP. He said that he had the impression that employing members of other ethnic groups over Haiǁom youths in ENP meant ‘erasing Haiǁom blood from Etosha, to remove the original owners from the park’.107

When the Permanent Secretary wanted to close the meeting after a brief absence, saying she would need to consult with the Minister, the Minister arrived unexpectedly, telling the audience that she had not read the agenda but got to know that the Haiǁom TA was present and thus came to greet the TA and to hear the discussion. When EHA members again raised their various concerns, she pointed out that the MET was not responsible for ancestral land claims, and referred the EHA to the MLR. She stressed that she would work with the chief of the Haiǁom TA. The representatives of the EHA again clarified that the EHA had been established because they did not recognise the chief and because the chief neither took the concerns of the community into account, nor shared any benefits provided to the Haiǁom TA with the community. Shortly thereafter, the Minister closed the meeting.108

The EHA representatives left the meeting with the impression that the MET showed little willingness to discuss their concerns and claims. Even some minor concessions by the MET concerning the various claims made by EHA would have smoothed the way for further negotiations. After the meeting, however, the EHA representatives came to the conclusion that the government’s intention was to remove the Haiǁom from ENP to the resettlement farms, and that Haiǁom would never be included in any development plans for ENP. Against this background, the EHA asked the LAC to initiate further legal action.109

On 31 August 2011, the Minister again came for a meeting at Okaukuejo, when a consultant contracted by MCA–N to conduct a feasibility study on a tourist concession to !Gobaub presented his concept. As was made clear by Kadisen ǁKhumub at the meeting, this feasibility study had been undertaken without proper consultation with Haiǁom in ENP, and he stressed the significance of !Gobaub as a holy place for Haiǁom. He expressed his fear that the significance of !Gobaub for him and other Haiǁom would not be respected in this initiative.110 Notably, the feasibility study explicitly identified as beneficiaries both members of the Haiǁom community who had moved to the resettlement farms neighbouring Etosha, and members of the Haiǁom community who resided within ENP. Furthermore, the study stated that the ‘Haiǁom community’ would need to accept the proposals before any further steps were taken, and that the formation of a legal entity such as a trust or an association of the Haiǁom was advisable.111

In September 2011, the EHA sent a letter again to the Minister of the MET demanding that they also be consulted in future planning regarding the concession.112 Since there was no reply from the MET, five months later the EHA reiterated the claims in another letter to the MET. They stated that: ‘we are left with little option but to assert our rights by way of possible legal action and refuse to be forced out of Etosha. We trust that you will appreciate that you have left us with no other options’.113

This time, the MET did react. In a letter to the Chief Executive Officer of MCA–N, the Minister allowed for the inclusion of ‘the Haiǁom groups’, most likely referring to the EHA, in the Trust (the legal entity to be formed).114 Strangely, though, this decision was not given effect in further developments. As mentioned above, when the !Gobaub Community Association was eventually constituted in September 2012, only the resettled Haiǁom were permitted to be members, and benefits from the concession would therefore only be available to Haiǁom residents on the resettlement farms.

It should be mentioned that Haiǁom had also tried on another front for their cultural heritage to be acknowledged. Since the turn of the millennium, a couple of Haiǁom elders had worked closely with the present author and other researchers and organisations to document their cultural heritage in ENP. The work, which had started rather informally involving various individuals and organisations, became formalised as the Xoms |Omis Project (Etosha Heritage Project), a community trust under the guidance of the LAC.115 The main objectives of the project were to research, maintain, protect and promote Haiǁom heritage associated with ENP and surrounding areas in order to capitalise on that heritage in the tourism sector; and to initiate capacity-building programmes based on this heritage for Haiǁom individuals with a genuine interest in the cultural, historical and environmental heritage of the park: for details see Chapter 15. The project had made several attempts to collaborate with NWR with a view to making products generated through this initiative—maps, posters, postcards, T-Shirts, a tour guidebook and a children’s book116—available in tourist shops in ENP; and to allow traditional dancing and generally increase the visibility of the Haiǁom cultural heritage in ENP. All these attempts were met with no success. It seemed that NWR had no interest at all in allowing attention to be drawn to the former presence of Haiǁom in ENP, and did not consider their presence and histories to be a potential tourist attraction.

During the same period, Haiǁom from different communities also employed a variety of strategies to bring about new elections for a Haiǁom TA. One initiative was a petition filed in 2011 to spark new elections.117 Another was the organisation of Haiǁom according to traditional subgroups118 with individuals representing these subgroups.119 These efforts too were unsuccessful.

The diplomatic strategies for Haiǁom to have their concerns taken seriously and to gain recognition as former inhabitants of ENP seemed to be exhausted, leading Haiǁom to choose legal action as a last resort. During 2013, the LAC and Legal Resource Centre (LRC, South Africa, which offered their support and experience for the legal action) had meetings with Haiǁom in Oshivelo and Outjo to further assess the possibilities and intricacies of a land claim and to garner further support for the case.

The then United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya (2008–2014) visited Namibia in September 2012 (as part of his mandate to examine the human right situation of Indigenous Peoples around the world), meeting stakeholders from government, UN agencies and non-governmental organisations, as well as various San communities, including Haiǁom in and around ENP. Relevant in the context of this chapter (i.e. ENP, the resettlement farms, and San TAs), he recommended the following in his report:

82. Namibia should take measures to reform protected-area laws and policies that now prohibit San people, especially the Khwe in Bwabwata National Park and the Haiǁom in Etosha National Park, from securing rights to lands and resources that they have traditionally occupied and used within those parks. The Government should guarantee that San people currently living within the boundaries of national parks are allowed to stay, with secure rights over the lands they occupy.

83. In addition, the Government should take steps to increase the participation of San people in the management of park lands, through concessions or other constructive arrangements, and should minimize any restrictions that prohibit San from carrying out traditional subsistence and cultural activities within these parks.

84. The Government should review its decision not to allow the Haiǁom San people to operate a tourism lodge within the boundaries of Etosha National Park under their current tourism concession. Further, management of concessions should not be limited to only those Haiǁom groups that opt to move to the resettlement farms. […]

87. Recognition of the traditional authorities of indigenous peoples in Namibia is an important step in advancing their rights to self-governance and in maintaining their distinct identities. The State should review past decisions denying the recognition of traditional authorities put forth by certain indigenous groups, with a view to promoting the recognition of legitimate authorities selected in accordance with traditional decision-making processes.120

Without venturing into legal questions in detail, reference should be made to the issue of locus standi and the subject of land, which were discussed at length amongst the involved lawyers.121 Being aware of the intricacies of the Central Kalahari Court Case, which originally included 243 applicants, a number later reduced to 189 surviving applicants,122 as well as the problematic position of the officially recognised Haiǁom TA and the problem of representation within former hunter-gatherer groups, it was decided to first launch a class action application on behalf of the Haiǁom. Class action lawsuits were not at this stage an option in Namibian law, and the country’s law needed to be developed to allow the applicants to pursue the legal action in a representative capacity on behalf of their community.123 Eight Haiǁom were the applicants in this action. Along with the government and some other stakeholders, the Haiǁom TA was a respondent.

The application was filed in 2015 and after two initial postponements, was heard in November 2018. It was dismissed in a judgement announced on 28 August 2019.124 The rationale for the dismissal was grounded in the Traditional Authorities Act, mentioned above. The judges held that the competent body to launch such an action would be the Haiǁom TA and that the applicants had not exhausted the internal remedies provided by the act, nor had they challenged the constitutionality of the provisions of the act.125

The appellants appealed the judgement in the Supreme Court in November 2021. They had revised their strategy, arguing that the TAA and international law were not in conflict with each other and that international law was ‘better equipped to support the rights of the Haiǁom’.126 As Willem Odendaal explained,

the core of the appellants’ submissions to the Supreme Court was first to show that nothing in the text, context and purpose of the TAA suggest that the Haiǁom, either as “a people” or “minority group” (as termed under international law) or “traditional community” (as termed under the TAA) prevented them from bringing the representative action.127

The Supreme Court, again, dismissed the Haiǁom litigants’ case, but for different reasons to the High Court. The Supreme Court opined that the TAA did not grant the Haiǁom Traditional Authority exclusive powers to pursue the community’s claims. Yet, it argued that the existing remedies in the legal system had not been exhausted by the applicants:

[c]lass action may not be part of our law but that does not mean no other form is available to pursue the claims. The applicants have not at all addressed the question why, failing the class action route, other forms of legal capacity to act do not offer the Haiǁom sufficient recourse to pursue their claims rather than reliance on the amorphous form in which they seek to act—a form which, like the class action is not recognised in our law.128

The Supreme Court pointed to ‘forms of legal organisation which could have been considered to overcome the unavailability of a class action’,129 namely forms of a universitas:

[a] universitas is a legal fiction or incorporeal abstraction which may be created in terms of legislation (eg, companies and close corporations, or other juristic persons specifically created by a statute, such as traditional authorities under the TAA, the Law Society, and various State-owned enterprises). Another form of universitas is an unincorporated association of natural persons also known as a voluntary association. The main characteristics of the universitas are its existence as a separate entity with rights and duties independent from the individual members’ rights and duties and that it has perpetual succession.130

A voluntary organisation, as a form of a universitas, could, according to Namibia’s High Court Rules, sue or be sued in its own name.131

It needs to be emphasised that the actual land claim of the Haiǁom was not yet brought to court, only the issue of locus standi was decided upon in their case. Odendaal comments:

[t]he application for representative action was in essence an effort to solve the question of standing. If the formation of the universitas manages to solve the question of standing, the source to support the merits of the Haiǁom people’s six land claims, […] namely constitutional, customary, common, comparative and international law could still be employed by the Haiǁom people. This is because neither of the two courts in the Tsumib case, have made any significant enquiries into or findings on the merits of ancestral land claims in Namibia. Therefore, the merits of the claims, as were presented in the application still needs testing and as such could be redeployed in a new application, or action if so desired. Indeed, if the universitas accomplishes to solve the Haiǁom people’s standing problem, then there should be no reason why the Haiǁom litigants could not rely on a combination of constitutional, customary, common, comparative and international law to advance their claims under the guise of a universitas.132

Given the enormous time and other resources which court cases like this one consume, it remains to be seen whether Haiǁom will continue with this path.

4.7 Discussion and Conclusion

During the course of developments described in this chapter, it became evident that the situation of Haiǁom in independent Namibia is complex, and the marginalisation most of them are experiencing, is difficult to overcome. This is due to several interrelated predicaments.

The overall predicament is that while ethnicity, ethnic consciousness and ethnic stereotypes are still prevalent in everyday life and lived experiences of Namibians (including Haiǁom) the government arguably fails to adequately address these issues.133 As James Suzman noted in 2001:

[i]n rural areas in particular, ethnic consciousness often prevails as a cipher for social action. The policy of separate development pursued by the apartheid regime polarised relations between different ethnic groups in Namibia, such that by the time of independence ethnic consciousness pervaded Namibian political and social discourse. The GRN’s strategy for dealing with this has been to deny “ethnicity” or ethnic consciousness any status in politics or policy and to subordinate all matters of customary law to the Constitution and laws of Namibia. While this may be the best strategy for dealing with these problems in the long term, as has reportedly been the case in Tanzania (Ndagala pers. comm.), it does have negative short-term consequences. Most significantly it makes few allowances for the role of ethnic consciousness in maintaining and reproducing uneven structural relations.134

The fact that Suzman’s assessment is still by and large correct 22 years later, points to this very predicament. Although the Namibian constitution prohibits discrimination on the grounds of ethnicity, more could be done to combat social stratification according to ethnicity. Namibia’s statistical population data (e.g. Population and Housing Census or Inter-censal Demographic Surveys) do not include ethnic variables but instead include the variable ‘main language spoken at home’, the categories ‘San language’ or ‘Nama Damara languages’ being amongst those listed.135 This categorisation disguises the fact, that Haiǁom and Khwe are both speaking Khoekhoegowab (‘Nama/Damara languages’), and that other San, especially in the northern regions, do not speak a San language anymore.136 Yet most Haiǁom and other San belong to the lowest strata of society in terms of social stratification and economic indicators. Not providing variables able to measure these facts accurately does not contribute to a solution. Furthermore, the government is preferring to talk about ‘marginalised communities’, but in fact refers to specific ethnic groups within its programme (San, Ovatue and ovaTjimba), and not, for instance, to farm workers, charcoal workers, widows, etc. Disguising the fact that ethnicity, and especially ethnic ascriptions, was and still is a major reason for marginalisation and discrimination, impedes appropriate and sustainable action.

The relevance of ethnicity, ethnic ideals and ethnic realities played out specifically in the historical events affecting the Haiǁom, interrelated with other factors. The area that Haiǁom inhabited in pre-colonial and early colonial times, namely northern-central Namibia, was an area highly valued by the colonial powers, both German and South African. It was partly of interest for its agricultural potential, partly as a protected area, and as a buffer zone to the north (of the Police Zone/Red Line).137 Haiǁom and others were not living at the margins but in the centre of the colonial enterprise (see Section 4.2 and Chapters 1, 2, 15 and 16), leading to their discrimination on the grounds of their assimilation with other “groups” and the appropriation of land they were inhabiting for settler farming (Section 4.2), as well as difficulties in terms of their representation with regard to the institution of Traditional Authorities (Section 4.4). As noted in Section 4.2, these factors meant that at Independence, Haiǁom found themselves dispossessed of their land, with no access to communal lands and thus no option to establish conservancies or community forests.

Ethnicity comes into play again, first, because their customs were not accommodated by the TAA, and second, because they continue to be considered as one of the San communities of Namibia. This label and the concomitant ideas are linked to land again. The government, attempting to somehow “restitute” them for the loss of land, employed the group resettlement approach specifically for San much longer than for other social groups who fell under the target groups of its land reform programme. These group resettlement farms proved up to now unable to provide sustainable livelihoods to their “beneficiaries”. They run the risk, in the absence of long-term and coordinated multi-stakeholder support, of becoming rural slums. As Koot and Hitchcock note:

[i]f the resettlement policy continues to be implemented as it is currently, a rural slum like Tsintsabis or a small town like Oshivelo could function as an example of the type of socio-economic problems that are typical of marginalisation and could easily happen elsewhere (for example, in “Little Etosha” [the resettlement farms south of Etosha]). What is interesting is that, although there is a lot of talk about land restitution to undo colonial practices, the loss of land subtly continues for the Haiǁom San. This quiet, yet insidious process may occur for a number of reasons, including: wealthy farmers extending their territories (as in Mangetti West); in-migration placing increasing pressure on resettlement farms (such as Tsintsabis); or Haiǁom being subtly pressured off their ancestral lands (most significantly, Etosha).138

Apart from the continuation or intensification of poverty for Haiǁom who have chosen to move to one of the resettlement farms, in-migration by (more dominant) others is a serious threat, taking place not only at Tsintsabis (see Chapter 16) but also at farms south of Etosha and Ondera.139 Without proper overall Haiǁom representation they have barely a chance to successfully fight former or current land dispossession.

Although the government is aware of the problematic role of the recognised Haiǁom chief, they blame the individual for his shortcomings and failure to adequately perform the tasks demanded by his position.140 But the similarities with other San communities dealing with other TAs, as well as problems encountered with the TAs of other groups,141 suggest that blame should not be laid at the door of the individual chief, but perhaps at the structuring effects of Traditional Authorities legislation in relation to cultures with egalitarian values at the core of their social organisation practices. In fact, the first judgement (the High Court judgment) in the Haiǁom case implied that this door is open.142 Odendaal notes that,

the court found that if the TAA infringes or does not adequately give effect to the constitutional rights of the Haiǁom people, then the applicants would have to challenge the constitutionality of the offending provisions of the TAA.143

Due to the failure of the TA to voice wider Haiǁom concerns, a court case was launched involving an application for class action to claim Haiǁom ancestral land (Section 4.6). A lot of effort was put into the question of representatives who could act on behalf of the Haiǁom community.144 In the first judgement though, the TA issue became the major obstacle preventing Haiǁom from launching an ancestral land claim.145

The government certainly welcomed the first judgement. Yet, the strategy of only negotiating with the Haiǁom TA brought with it its own problems and costs for the government. It is questionable whether this strategy was a hindrance to the goals the government had in mind for the Haiǁom.146 First, having not ensured the support of the wider Haiǁom community in their resettlement plans this situation impeded the government’s plans to resettle the Haiǁom from ENP. The initial issue of unemployed Haiǁom there has not been solved, as the government is loath to involuntarily remove them. Second, the development of the concession has not been taken forward. Third, financial and technical support channelled through the chief does not necessarily reach the wider community, or even all beneficiaries on the resettlement farms, where there are high levels of dependency on government aid and no signs that this might change in the near future.

Finally, in taking the Haiǁom from Etosha seriously, the court case might have been prevented. When Haiǁom from Etosha started corresponding with the government in 2010, they asked for acknowledgement that they were the former inhabitants of ENP, and wanted as such to be involved in decision-making regarding Etosha’s future development. They also wanted recognition that their cultural heritage and history are inseparably connected to the ENP lands, and they therefore asked for !Gobaub as a Haiǁom cultural heritage site. For those still employed in ENP and their descendants, they demanded that Haiǁom should be given preferential status when it comes to employment opportunities in the park. It is noteworthy that at the initial stage of their struggle, no explicit request was made for financial compensation. Considering the estimated market value of the ENP lands being around N$3.8 billion,147 these initial requests appear rather modest. However, the government was not inclined to accommodate any of the requests. With minor admissions, the government could have circumvented litigation and concomitant public and media attention.

Even if the outlook for the future does not currently look too bright for Haiǁom, the second court ruling in the Supreme Court148 is of vital significance. In promoting the legal form of a universitas (e.g. a voluntary organisation), it opens doors for legal claims (e.g. ancestral land claims) in the name of Haiǁom, but not necessarily via the TA. Even outside the courtroom, this judgement hopefully has some influence on the government in reconsidering its strategy of merely negotiating with the Haiǁom TA. It is time that political Haiǁom representation, with or without one or several recognised TAs, becomes stronger and recognised locally, regionally and nationally.

Archive and other primary sources

NAN SWAA A 267/11/1 1956: Report of the Commission for the Preservation of Bushmen in South West Africa.

E.H.A. [Etosha Haiǁom Association] Committee 2011. Letter E.H.A. to Minister of Environment and Tourism, Honorable Minister Mrs. Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, cc’d to Ministry of Lands and Resettlement, Millennium Challenge Account, Namibia Wildlife Resorts, Haiǁom Traditional Authority, Office of the Prime Minister, San Development Programme, The Legal Assistance Centre.

High Court of Namibia 2019. Tsumib and Others versus Government of the Republic of Namibia and Others (A206/2015[2019]) NAHCMD 312 (28.8.2019) (Tsumib).

Jan Tsumib and 8 others v Government of the Republic of Namibia and 19 others, Case Number A206/2015.

Khumub, K. 2011. E.H.A. letter to MET.

Khumub, K. 2012. E.H.A. letter to MET.

Komob, B. 2010a. Letter to the Minister of MET on behalf of the Haiǁom Community Group.

Komob, B. 2010b. Letter to LAC: Okaukuejo Haiǁom are ready to take the Namibia Government to court.

Komob, B. 2011a. Minutes E.H.A. community meeting at Okaukeujo.

Komob, B. 2011b. Minutes of the Presentation on the Draft Proposal Tourism Traversing Rights Concession with Haiǁom Communities in and out Etosha National Park.

Supreme Court of Namibia 2022. Tsumib and Others versus Government of the Republic of Namibia and Others (SA 53/2019) [2022] NASC 6 (16.3.2022).

Bibliography

Amupadhi, T. 2004. New Haiǁom Traditional Authority eyes Etosha. The Namibian 29.7.2004, https://www.namibian.com.na/new-hai-om-traditional-authority-eyes-etosha/

Anaya, J. 2013. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, James Anaya TheSsituation of Indigenous Peoples in Namibia. Online Supplementary Material at https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/762527?ln=en

Boden, G. 2009. The Khwe and West Caprivi before Namibian independence: Matters of land, labor, power and alliance. Journal of Namibian Studies 5: 27–71, https://namibian-studies.com/index.php/JNS/article/view/25/0

Collinson, R. 2011. Feasibility Study: Exclusive Access Tourism Concession Inside Etosha National Park for Direct Award to the Haiǁom Community. Unpublished Report.

Dieckmann, U. 2001. ‘The Vast White Place’: A history of the Etosha National Park and the Haiǁom. Nomadic People 5: 125–53, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43124106

Dieckmann, U. 2007. Haiǁom in the Etosha Region: A History of Colonial Settlement, Ethnicity and Nature Conservation. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Dieckmann, U. 2009. Born in Etosha: Homage to the Cultural Heritage of the Haiǁom. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre.

Dieckmann, U. 2011a. The Haiǁom and Etosha: A case study of resettlement in Namibia. In Helliker, K. and Murisa, T. (eds.) Land Struggles and Civil Society in Southern Africa. New Jersey: Africa World Press, 155–89.

Dieckmann, U. 2011b. Minutes of Meeting E.H.A. with MET. Unpublished.

Dieckmann, U. 2012. Born in Etosha: Living and Learning in the Wild. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre.

Dieckmann U. 2014. Kunene, Oshana and Oshikoto Regions. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 173–232.

Dieckmann, U. 2020. From colonial land dispossession to the Etosha and Mangetti West Land Claim—Haiǁom struggles in independent Namibia. In Odendaal, W. and Werner, W. (eds.) Neither Here Nor There: Indigeneity, Marginalisation and Land Rights in Post-independence Namibia. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre, 95–120, https://www.lac.org.na/projects/lead/Pdf/neither-5.pdf

Dieckmann, U. and Begbie-Clench, B. 2014. Consultation, participation and representation. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 595–616.

Dieckmann, U. and Dirkx, E. 2014a. Access to land. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 437–64.

Dieckmann, U. and Dirkx, E. 2014b. Culture, discrimination and development. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 503–22.

Dieckmann, U. Thiem, M. and Hays, J. 2014. A brief profile of San in Namibia and the San development initiatives. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 21–36.

Eriksen, T.H. 1993. Ethnicity and Nationalism: Anthropological Perspectives. London: Pluto Press.

GRN 2000. Traditional Authorities Act. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia.

GRN 2010. Report On the Review of Post-resettlement Support to Group Resettlement Projects/farms 1991-2009. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia.

GRN 2017. Fifth National Development Plan (NDP5) 2017/18–2021/2022. Windhoek: National Planning Commission, https://www.npc.gov.na/national-plans/national-plans-ndp-5/

Harring, S.L. and Odendaal, W. 2002. ‘One Day We Will All Be equal…’: A Socio-legal Perspective On the Namibian Land Reform and Resettlement Process. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre, https://www.lac.org.na/projects/lead/Pdf/oneday.pdf

Hays, J., Thiem, M. and Jones, B. 2014. Otjozondjupa Region. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 93–172.

Hitchcock, R.K., Sapignoli, M. and Babchuk, W.A. 2011. What about our rights? Settlements, subsistence and livelihood security among Central Kalahari San and Bakgalagadi. The International Journal of Human Rights 15: 62–88, https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2011.529689

Itamalo, M. 2016. Ondera is Namibia’s resettlement jewel. The Namibian 29.7.2016, https://www.namibian.com.na/ondera-is-namibias-resettlement-jewel/

Jones, B. and Diez, L. 2011. Report to Define Potential MCA-N Tourism Project Support to the Haiǁom. Windhoek, Unpublished Report.

Kahiurika, N. 2017. Haiǁom tourism concession in limbo. The Namibian 23.8.2017, https://allafrica.com/stories/201708230930.html

Koot, S. and Hitchcock, R.K. 2019. In the way: Perpetuating land dispossession of the Indigenous Haiǁom and the collective action lawsuit for Etosha National Park and Mangetti West, Namibia. Nomadic Peoples 33: 55–77, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26744808

Krämer, M. 2020. Neotraditional authority contested: The corporatization of tradition and the quest for democracy in the Topnaar Traditional Authority, Namibia. Africa 90(2): 318–38, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972019001062

Lawry, S. and Hitchcock, R.L. 2012. Haiǁom Resettlement Farms: Land Use Plan and Livelihood Support Strategy. Unpublished Report.

Lawry, S., Begbie-Clench, B. and Hitchcock, R.K. 2012. Haiǁom Resettlement Farms Strategy and Action Plan. Unpublished Report.

Marais, F. 1984. Ondersoek na die Boesmanbevolkningsgroup in S.W.A. Edited by Direktoraat Ontwikkelingskoördinering. Windhoek.

Menges, W. 2019. Etosha land rights claim stumbles at first hurdle. The Namibian 29.8.2019, https://www.namibian.com.na/etosha-land-rights-claim-stumbles-at-first-hurdle/

MET 2007. Haiǁom San Socio-economic Development Adjacent to the Etosha National Park. Project Information Document. Windhoek: Ministry of Environment and Tourism.

MET 2012. Head Concession Contract for the Etosha South Activity Concession – Etosha National Park. Windhoek: Ministry of Environment and Tourism.

Miescher, G. 2009. Die Rote Line. Die Gesichte der Veterinär- und Siedlungsgrenze in Namibia (1890er-1960er Jahre). PhD thesis: Basel.

Millennium Challenge Account–Namibia 2010. Request for Proposals MCAN/COM/RFP/2CO2001 for Conservancy Support Development Services. Unpublished.

Ministry of Gender Equality, Poverty Eradication and Social Welfare 2022. Annual Report 2021/2022. Online Supplementary Material at https://mgepesw.gov.na/documents/792320/0/MGEPESW+AWP+20-21+Report.pdf/1f5a05d7-a193-98ec-ae18-dd30e00b48e9

Mumbuu, E. 2018. Farm Ondera on the right trajectory. The Namibian 21.5.2018, https://namibian.com.na/farm-ondera-on-the-right-trajectory/

NSA 2017. Namibia Inter-censal Demographic Survey 2016 Report. Windhoek: Namibia Statistics Agency.

National Planning Commission 2007. Oshikoto Regional Poverty Profile. Windhoek: Central Statistics Office.

Odendaal Report 1964. Report of the Commission of Enquiry into South West African Affairs 1962-1963. Pretoria: The Government Printer.

Odendaal, W. 2022. ‘We Are Beggars On Our Own land…’ An Analysis of Tsumib v Government of the Republic of Namibia and its Implications for Ancestral Land Claims in Namibia. Unpublished Phd Thesis, School of Law, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow.

Odendaal, W., Gilbert, J. and Vermeylen, S. 2020. Recognition of ancestral land claims for indigenous peoples and marginalised communities in Namibia: A case study of the Haiǁom litigation. In Odendaal, W. and Werner, W. (eds.) 2020. ‘Neither Here Nor There’: Indigeneity, Marginalisation and Land Rights in Post-independence Namibia. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre, 121–42, https://www.lac.org.na/projects/lead/Pdf/neither-6.pdf

Oreseb, C. 2011. Reader’s Letter: All is not well with the Haiǁom. New Era 24.6.2011.

Rasmeni, M. 2018. Seringkop community no longer needs to travel to Outjo for primary health care. Namibia Economist 26.6.2018, https://economist.com.na/36279/health/seringkop-community-no-longer-needs-to-travel-to-outjo-for-primary-health-care/

Sapignoli, M. 2015. Dispossession in the age of humanity: Human rights, citizenship, and indigeneity in the Central Kalahari. Anthropological Forum 25: 285–305, https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2015.1021293

Shigwedha, A. 2007. San to get land near Etosha. The Namibian 26.3.2007, https://www.namibian.com.na/san-to-get-land-near-etosha/

Staff Reporter. 2018. Haiǁom San receive N$7m farming boost. The Namibian 1.10.2018, https://namibian.com.na/hai-om-san-receive-n7m-farming-boost/

Suzman, J. 2001. An Assessment of the Status of the San in Namibia. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre, http://www.lac.org.na/projects/lead/Pdf/sannami.pdf

Suzman, J. 2004. Etosha dreams: An historical account of the Haiǁom predicament. Journal of Modern African Studies 42: 221–38, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X04000102