6. The politics of authority, belonging and mobility in disputing land in southern Kaoko

©2024 E. Olwage, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0402.06

Abstract

The focus of this chapter concerns the interwoven politics of authority, belonging and mobility in shaping “customary” land-rights in southern Kaoko. I argue that ancestral land-rights need to be understood as a social and political rather than a historical fact, and one which is relationally established and re-established in practice, over time, and at different scales. The chapter draws on research conducted from 2014 to 2016 comprising a situational analysis of a land and grazing dispute in southern Kaoko, in and around Ozondundu Conservancy. It shows how persons and groups were navigating overlapping institutions of land governance during an extended drought period, in a context shaped by regional pastoral migrations and mobility. This case material illuminates how conservancies and state courts have become key technologies mobilised to re-establish the interwoven authority and land-rights of particular groups of people. This dynamic is especially the case, given a post-Independence shift towards more centralised state-driven land governance, amidst deeply rooted political fragmentation in most places, and land-grabbing by some migrating pastoralists. The chapter concludes by arguing for the importance of engaging socially legitimate occupation and use rights, and decentralised practices of land governance, towards co-producing “communal” tenure and land-rights between the state and localities. This emphasis is critical for evidence-based decision-making and jurisprudence in a legally pluralistic context.

6.1 Introduction

This chapter draws on a situational analysis1 of a land and grazing dispute during a multiyear drought in the semi-arid communal rangelands of Namibia’s northern Kunene Region, also known as Kaoko. Whereas average rainfall between 1998 and 2011 was estimated at 377.2 mm per year, during 2012–2014 a reduction of 45.8% was observed for the region.2 For Kaoko’s predominantly pastoral and agro-pastoral societies, this meant not only widespread cattle losses but also extensive livestock and socio-spatial mobilities in northern Kunene Region as crucial drought risk management strategies.3 The Ozondundu Conservancy in southern Kaoko also experienced an influx of “those who were on the move” (sing. omuyenda, pl. ovayenda). Many of these mobilities eventually became a strong bone of contention, culminating into a local and legal dispute (also see Chapter 3). Given the constitutional protection of communal land-rights, some cases were finally taken to the High Court of Namibia in Windhoek.4 In this chapter, I take a closer look at a particular dimension of this dispute: the interwoven politics of authority, belonging and mobility5 in shaping ‘socially legitimate occupation and use rights’.6 In so doing I illustrate how ancestral land-rights in north-western Namibia should be understood as a social and political rather than a historical fact, and one which is relationally established and re-established in practice, over time, and across local and regional scales.

The chapter has two contentions. First, I unpack the resilient myth of kin-based rural “villages” or local “communities” as an often-imagined site of trust, stability, and cohesion, including in decentralised models of land and resource governance. As I illustrate, these localities should be simultaneously conceptualised as sites of ‘mobility and struggle’,7 in which migration often emerges, not only as a response to drought, but also as a ‘critical response to irreconcilable situations of disagreement and dispute’, including between kin.8 This chapter thus looks closely at how complex patterns of migration and mobility shaped and are shaping the social and political embeddedness of communal tenure within the Kunene Region, including through the integration of newcomers.9 Secondly, the chapter aims to address the question of socially legitimate occupation and use rights in a context where state-driven communal land reform ‘do[es] not appear to have removed the uncertainty about legitimate access and rights to land’.10 Rather, in some instances, these provisions are generating and heightening local frictions (also see Chapter 5). The chapter aims to critically engage with these frictions, especially concerning unresolved issues of overlapping jurisdictions and authority over land, perceived as negatively impacting land-rights11 (also see Chapters 3, 4 and 16). In doing so, I explore how tenure was co-produced from the ground-up, including through everyday political, socio-spatial, and legal practices.

The concept of “legal pluralism” is often mobilised to refer to the existence of interacting, simultaneous and competing normative frameworks co-existing within the same social order, or society.12 I approach this concept not as an explanatory theory but rather as a ‘sensitising concept’,13 enabling one to engage with interactions and power relations between formal, codified state law and policy, and local living norms. I regard “custom” as ‘a dynamic domain of African jurisprudence, evolving in tune with vernacular usage and context, and not as a static repertoire of rules established definitively in the past’.14 Such understanding foregrounds the ‘processual nature of local law’ instead of the straightforward application of rules.15

I engaged with the dispute during my PhD research (2014–2016), which included participating in dispute meetings and processes, and conducting ethnographic research within and in the surroundings of Ozondundu Conservancy and neighbouring conservancies, where the dispute took place. The situational or extended case study approach argues for theorising the general ‘through the dynamic particularity of the case’.16 Instead of using case material as “an example”, such material is instead taken as the starting point for wider analysis through a praxis-based lens.17 The first section of this paper provides a discussion on the overlapping institutions of land governance in southern Kaoko. This is followed by a short description of the dispute. Subsequent sections each analyse specific dimensions of the dispute, including interrelated contestations over territory, place, authority, belonging, mobility, and land-rights.

6.2 Overlapping institutions of land governance

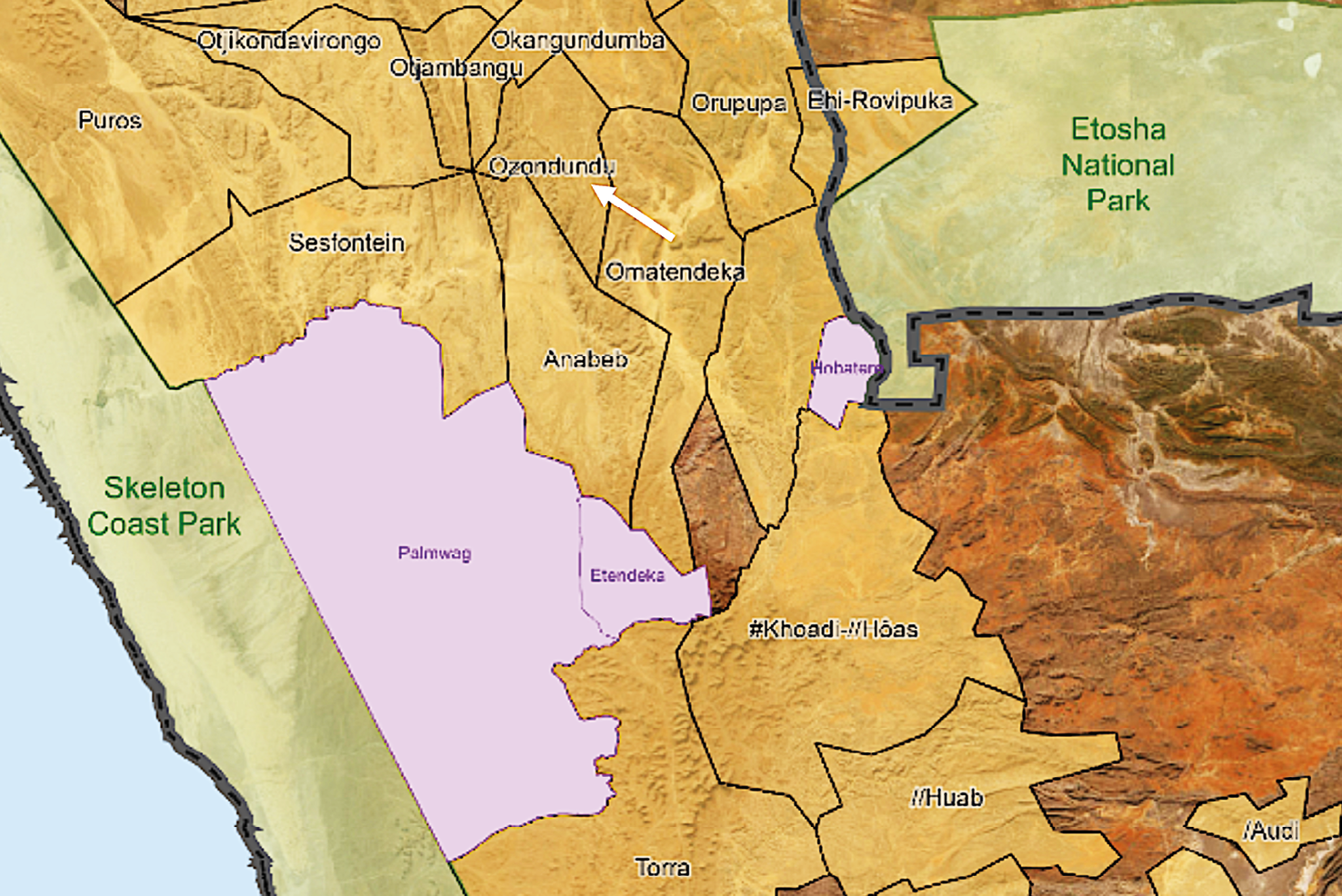

Ozondundu––meaning mountains––is a conservancy that incorporated interrelated settled and cattle-post places within southern Kaoko, with predominantly otjiHerero-speaking homesteads forming part of a historically-constituted and kin-based shared land-use community (see Figure 6.1).

Livelihoods in Ozondundu were rooted in subsistence pastoralism combined with: rain-fed agriculture and harvesting; community-based conservation, hunting and tourism; state social grants; and regular oscillatory migration and travelling to urban centres to engage in wage labour and enterprising activities that may include sending remittances back to the rural areas.

Fig. 6.1 Map showing location of Ozondundu Conservancy in between Etosha National Park and the Skeleton Coast National Park. Source: NACSO’s Natural Resource Working Group, June 2023, adapted from Figure 3.2, Chapter 3, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Situated in the northern Kunene Region, Ozondundu Conservancy is part of Namibia’s communal lands. Post-Independent Namibia inherited a ‘dualistic land tenure structure’18 after more than a century of German (1884–1915) then South African (1917–1990) colonial and apartheid occupation and rule (see Chapters 1 and 2). Whilst around 43% of Namibia’s land area falls under freehold title, 42% constitute “communal lands” or non-freehold land—legally in state guardianship—with remaining areas proclaimed as state land.19 In contrast to freehold title, rights to land within Kaoko’s communal lands are administered through the Kaokoland Communal Land Board (established through the Communal Land Reform Act of 2002) and relevant Traditional Authorities (TAs). They are thus simultaneously legal in a formal sense, as well as applying principles of legalised customary governance and subject to the Constitution.20 Yet here, as elsewhere in Namibia, “communal” tenure evolved and continues to evolve at the intersection of inherited Indigenous land-relations, culturally-informed institutions, and colonial and post-colonial state policies.

Given southern Kaoko’s dryland and mountainous environment, land-use and pastoral practices were negotiated through mobile land-use, with both the socio-spatial mobility of households and herds remaining crucial strategies for coping with drought periods and highly localised rainfall patterns.21 This land-use was socially and spatially organised between interrelated settled and ancestral places (ovirongo vyomaturiro) and adjoining and shifting seasonal cattle-posts (ovirongo vyohambo). Movement between these places was seasonally negotiated, depending on the size of livestock herds, mutual availability of labour, water, pastures, and cultivation possibilities, as well as experiences of drought events. In addition, several households practiced what can be understood as ‘multispatial livelihoods’22 or multilocal households, with their herds and fields separated between localities, and household economies organised between rural and urban mobilities.

Ancestral land-relations and the practice of kinship, specifically dual descent kinship, remain key institutions governing locally nested and bundled rights over land and land-based resources in this context, with land-use boundaries overlapping and networked.23 In any ‘communal’ or ‘customary’ lands, ‘rights to land are intimately tied to membership in specific communities, be it the nuclear or extended family, the larger descent group (clan), the ethnic group, or as is the case in modern property regimes, the nation state’. 24 In the context of this research, kin, and clan-based belonging to one’s matriclan (sing. eanda, pl. omaanda) and patriclan (sing. oruzo, pl. otuzo) were crucial. However, membership in these groups was not “a given” and had to be practiced. In addition, such belongings overlap and intersect with other forms of social and political belonging in shaping locally nested and bundled rights over land and land-based resources.

Historically, and as Bollig25 and Friedman26 have shown, tenure in Kaoko was founded upon an historicised relationship between one’s patrilineal and matrilineal ancestors and specific land-areas (as also explored for diverse residents of Etosha-Kunene in Chapters 12, 13, 14 and 15). Such relationships were and continue to be established through creating material-symbolic ties to the land, such as the ability to locate one’s ancestral graves as well through ‘oral knowledge’27 and performance practices, including praise poetry (sing. omitandu, pl. omutandu).28 Moreover, the remembrance of the social histories of past group migrations (ekuruhungi rwomatjindiro),29 including through narratives of migration and settlement, are a crucial part of rooting ancestral land-relations. These narratives and material-symbolic practices shape both collective and divergent forms of social and political belonging, integrate interrelated (and often translocal) ancestral and cattle-post places, and vernacularly construct place and territorial boundaries.30 Hence, they work as a kind of ‘oral land registry’31, a vernacular and emplaced archive. Place-relations were also reiterated in practice, through everyday land-use and mobilities.

These land-relations were also closely intertwined with the construction of legitimate authority relations in the allocation of rights to access land and land-based resources, with such claims closely intertwined with ancestral and especially patrilineal claims to specific land-areas. Such institutions are reflective of pan-African frontier dynamics in which the ‘principle of precedence’ is ‘intimately intertwined with the legitimacy of authority’, with those longer in residence acquiring (over time) more rights over land and resources, with such rights subsequently ritually expressed.32 Yet first-comer narratives—like any narratives—are socially rather than historically constructed, and are open to contestation and changing interpretations, being important political resources within local and wider struggles over authority and land (see Chapter 1). Prior to colonial indirect rule, and within this form of tenure amongst otjiHerero-speaking pastoralists, senior men connected to first comer homesteads were considered the guardians of the earth/land (oveni vehi) with people settled around them being their patrilineal and matrilineal relatives.33 Any newcomer usually needed his permission to settle.

Subsequently, such authority is now primarily vested in a network of local (and male) headmen (sing. osoromana, pl. ozosoromana), councillors (sing. orata, pl. ozorata) and chiefs (sing. ombara, pl. ozombara), with this political structure historically co-constructed during colonial indirect rule and with state recognition as an important source of outside legitimisation, especially in a context of competing chieftaincies. As shown in Section 6.3, however, the authority to allocate rights to access in southern Kaoko also remains strongly decentralised in institutions of collective deliberation.

The Ozondundu boundaries were only cartographically mapped in the early 2000s with the establishment of communal area conservancies in the region, although its genealogy is constructed both in shared histories of land-use and legacies of colonial tenure policies. The then South African administration established the Kaokoveld “native reserve” and later the Kaokoland “homeland”,34 introducing new administrative structures and internal boundaries (see Chapter 2). From the late 1940s onwards, Kaoko was divided into several ‘wards’,35 administered by state-salaried headmen and sub-headmen, responsible for allocating rights of access within these boundaries.36 This process built on the prior negotiation of indirect rule in which chiefs were appointed, with the wards subsequently incorporated into different and competing chieftaincies.37

This mapping of wards was facilitated by an expansive borehole drilling programme and the parallel construction of a large network of roads, with the goal of introducing more sedentary forms of pastoral land-use, as well as to divide (and rule) Kaoko’s different groups:38 see Chapter 7. Yet this process was also negotiated by local actors. For instance, the Ozondundu households mobilised to claim an independent ward by the 1980s: rooted both in a shift towards more localised forms of transhumance land-use with the drilling of boreholes and the devastating drought of 1981–1982; as well as political histories of fragmentation from neighbouring chieftaincies claiming autonomy in dealing with the state.39

After Independence, the colonial tenure systems—i.e., ward boundaries and the local institution of headmanship—were no longer officially recognised.40 Rather, initial engagement with state-driven communal land reform hinged on the official recognition of customary law and authorities. Consequently, legislative frameworks for the recognition of customary authorities were put in place, now organised as TAs under the Traditional Authorities Act of 2000.41 Local leaders and groups had to rely on competing claims for state recognition within new legislative bounds and blue-print institutional structures, with historical (hereditary) legitimisation being a strong prerequisite and TAs re-structured as a chief and his normally 12 councillors.42 With the gazetting of communal conservancies from the late 1990s onwards, many local headmen mobilised this process in an attempt to reaffirm their jurisdictions and authority, with several conservancy boundaries subsequently mirroring that of the former wards, including the Ozondundu Conservancy.43

Importantly, conservancies as registered entities with elected governing committees, have no legal powers or local duties with regards to land administration.44 Consent by TAs, in this case local headmen, was required, however, in gazetting conservancy boundaries and establishing local land-use plans. Unofficially this involvement provided a tool for local headmen to cartographically (re)assert and document their jurisdictions, including to rally support for state recognition within broader TA structures during a period of transition. There is also no legal basis for either including or excluding local headmen and TAs with Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) governance structures:45 at a local level, elected committees usually do not include them, unless in an advisory role. Still, local headmen and their senior councillors (on a local level) exercise influence in conservancy governance, especially given their long-standing role in governing the allocation of rights to access land and land-based resources, including as mediators.

Currently, there are 38 gazetted communal conservancies in Kunene Region (as reviewed in Chapter 3). This rapid increase, as both Sullivan46 and Bollig47 have argued, was partly due to local interpretations of conservancy proposals as a land and territorial, rather than an exclusively wildlife management issue (especially in the 1990s and 2000s), with these boundaries now signifying the known jurisdictions of headmen and emerging place identities.

Furthermore, the Communal Land Reform Act (CLRA) of 2002, together with the Traditional Authorities Acts of 1995/2000, situated state-recognised TAs as the ‘supreme power to allocate land or to deny settlement permission according to traditional rules’, given that these do not conflict with constitutional and statutory law.48 This fuelled a degree of centralisation of authority in the TAs and chiefs, rather than local headmen and places, further igniting struggles over recognition. This reform was accompanied by the launching of a programme for codifying and registering communal land-rights in 2003, and the formation of regional Land Boards to ratify such applications.49 The land-right remains for the period of a person’s natural life and can be passed on to next of kin, given that this is done through the state’s processes50 (also see Chapter 13).

Communal land-rights usually focus on a bounded residential and/or farming unit, with sizes relatively established, yet not exceeding 50 ha,51 with most being much smaller than this.

In most of Kaoko, and until recently, there has been limited engagement with this formal titling process given how it conflicts with mobile land-use practices and existing institutions governing nested and bundled rights over land and land-based resources. Additionally, the registration of land-rights only applies to individual and/or private rights on communal land, and does not include similar protection for grazing rights within commonages, including group-based rights,52 which are governed in Kaoko primarily by the state-recognised TAs, and in this case through local-level headmen. Nevertheless, fears and anticipation of such formal titling process have in some instances fuelled regional migrations and land-grabbing. In addition, post-independent reforms signalled a shift away from verbally negotiated and allocated rights to access as practiced in large parts of Kaoko, towards more codified and formalised modes of land governance.53

It is thus within this shifting legal and politically pluralistic context that the dispute took place and was negotiated; with the dispute itself emerging as a crucial arena within which these intersecting normative frameworks were fashioned and refashioned. Hence, as I will illustrate throughout this chapter, within Kaoko long-standing institutional arrangements, instead of being completely abandoned, are revised within existing ‘sedimented layers’ in what has been termed ‘bricolage work’54 (also see Chapter 7). In so doing, I focus specifically on the interwoven politics of belonging, authority and mobility which animated the dispute and how this shaped socially legitimate occupation and use rights, especially land-rights.

6.3 A land and grazing dispute

From 2012 onwards, Ozondundu experienced several in-migrations, including of livestock herds. By the start of 2015, tensions between the so-called residents or dwellers (sing. omuture, pl. ovature) and the newcomers (sing. omuyenda, pl. ovayenda) were heightened as pastures dwindled. This situation culminated in dispute meetings in the shade of a large Leadwood (Combretum imberbe) tree in a place called Otjomatemba (see Figure 6.2). The early meetings were focused on tracing the different newcomers’ genealogies of arrival and to situate them socially and relationally. Complicating the deliberations were cases raised and discussed which involved persons and households not necessarily designated as newcomers, yet whose livestock mobilities and/or belonging were still contested or ambiguously situated. Included in this non-newcomer category were former residents who had moved herds into the area, married women who had returned with their own livestock as well as that of their affinal kin, and migrating and closely related households from neighbouring areas. Distinctions and boundaries between residents and newcomers were thus riddled with ambiguity, often intentionally, to maintain the flexibility required for navigating overlapping land-use boundaries and drought events.

Eventually, however, a contested group of newcomers was differentiated. They included seven heads of homesteads allocated drought-related temporary access-rights in the past and who had left again. A further eight to 10 households were also identified who arrived subsequently, with some claiming they had negotiated their access through the prior newcomers, or that they belonged to these homesteads and thus had rights of access. Such claims and genealogies of arrival were disputed. Moreover, in the previous year, a meeting was held where all those who came because of drought were asked ‘to return to where they had come from’. This request was not adhered to. Such practices were perceived to be a violation of existing social norms governing shared pastures (also see Chapter 3). These “newcomers” were eventually situated as having settled forcefully (ovature wokomasa), or with arrogance (ovature ovana manjengu)—having first arrived by ‘asking for drought’ (omuningire wourumbu) and then refusing to leave.

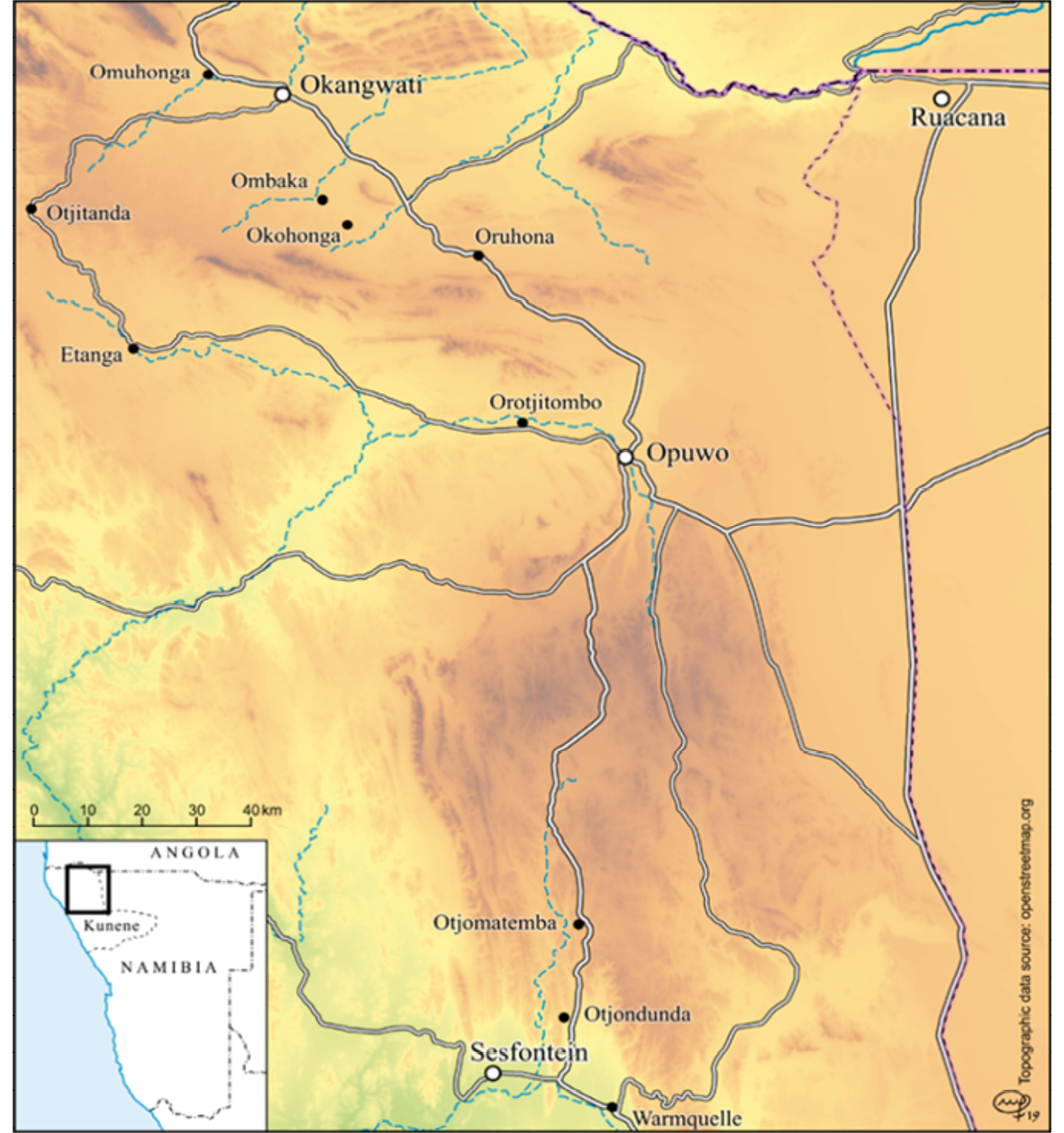

Fig. 6.2 Southern Kaoko places between which migration occurred. © Cartographer Monika Feinen, created for this research and used with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

As the dispute progressed two further critical dimensions surfaced. First, most of these contested newcomers were considered relative strangers, i.e., they had come from afar and did not share a long-standing reciprocal relationship or close kin-relations with the Ozondundu households. The majority were ovaHimba homesteads who, during the previous decade, had initially migrated from northern Kaoko and the Epupa constituency (places like Oruhona, Etanga and Ombaka) south to the Anabeb and Sesfontein conservancies, to places such as Otjondunda and Warmquelle (see Figure 6.2). From 2012 onwards, however, these regional migrations were combined with a general increase in drought-related livestock movements. This meant that several households moved their livestock north again into Ozondundu (especially Otjomatemba) in search of pastures.

A second key dimension differentiating the newcomers was that in countering their expulsion, many claimed they had in fact been allocated settlement and/or grazing rights by one headman. At the time of the dispute Ozondundu had two local headmen each affiliated to oppositional Traditional Authorities (TAs). Whereas the state-recognised headman (Muteze) affiliated to the Vita Thom Royal House as a senior councillor in the official structure, a newly locally appointed headman (Herunga)—who at this stage was unrecognised within the official TA structure—was affiliated to the Otjikaoko Traditional Authority (both headmen are ovaHerero) (see Figure 3.8, Chapter 3, for locations of the formally recognised TAs in Etosha-Kunene). For many Ozondundu residents, such local-level divisions were seen as a root cause of the dispute.

In the course of time and after several weeks of deliberations, most of Ozondundu’s residents eventually reached a consensus that the newcomers had to leave in 21 days. Although emphasising expulsion, it was reiterated that homesteads were welcome to return, given that they respect social norms. Eventually, after five weeks passed and with several unsuccessful attempts to evict the homesteads, wider networks were mobilised. These networks involved neighbouring headmen who shared socio-political affiliation: primarily to the Vita Thom Royal House and the Ovaherero Traditional Authority led by the Herero Paramount Chief acting as an umbrella body for all ovaHerero and ovaHimba TAs in Namibia. In a final attempt these groups gathered at the newcomers’ homesteads to subtly coerce them to leave (successfully), and subsequently travelled to other areas to try to do the same with regards to long-standing disputed cases (unsuccessfully).

Despite a dramatic exodus from Ozondundu, with the onset of the dry-season several newcomer households returned. Meanwhile, the dispute shifted to the state courts. Given the constitutional protection of communal land-rights, a case was opened in the High Court in Windhoek. This case involved affiliated chieftaincies in southern Kaoko (specifically the neighbouring Ongango, Otjapitjapi (in Ozondundu), and Ombombo chieftaincies), with specific newcomer cases across all three of these areas.

To better understand what was at stake within this dispute, Sections 6.4 to 6.8 focus on the interrelated dynamics detailed above. I first examine how the dispute was shaped by local struggles and divisions within Ozondundu, specifically over authority and territory, showing how these divisions were embedded within the legacies of a ‘factional dynamic’55 within Kaoko. Building on this analysis, I delineate the mobility and settlement practices characterising the disputed newcomers, including how this triggered a reassertion of social norms and a place-based politics of authority and exclusion. By drawing on cases raised during the dispute, I discuss the micro-politics of belonging in the integration of newcomers. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the politics of belonging and authority in legally disputing land and socially legitimate rights to access within southern Kaoko, including looking at the outcome of the case mentioned above.

6.4 Disputing territory and factional belonging

For many residents and newcomers, the local struggles over authority were situated as a key root cause of the dispute (albeit from different positionings), as well as of the wider land conflicts within southern Kaoko as a then emerging ‘zone of rural immigration’.56 Although orchestrated at a local level, this proliferation of local headmen was embedded in larger and long-standing territorial struggles. Histories of political fragmentation took root already pre-Independence, leading to Kaoko post-Independence emerging as a site of both political struggle and marginality, with particular local implications for land governance.57

Since 1998, multiple TAs were given state recognition within Kaoko, rooted in an historically-constituted factional dynamic. As mentioned in Section 6.3, two oppositional TAs were recognised in southern Kaoko specifically: the Otjikaoko Traditional Authority and the Vita Thom Royal House.58 In addition, although not officially recognised within Kaoko, many local leaders were affiliated with the Ovaherero Traditional Authority. In the official structure, each TA was represented by a chief and his normally 12 councillors, with many of these councillors in turn functioning as local headmen (ozosoromana), with their own local level councillors—creating a layered structure of authority. In addition, there were local headmen who were established during colonial indirect rule but subsequently not recognised in the official TA structures. Importantly, and in contemporary Kaoko, none of these state-recognised TAs had clear territorial jurisdictions: their jurisdictions overlapped, with most conservancies and places divided in terms of affiliation, including Ozondundu.

Implicitly embedded within the Traditional Authorities Act (TAA) was the assumption that recognition hinges on the ‘possession by a group of a “separate identity” based on common ancestry, language, cultural heritage, customs and traditions, a common traditional authority, and the inhabitation of a common communal area’.59 Similar to what has been noted in post-apartheid South Africa, the idea of a ‘traditional community’ combines with the ‘rubric of custom’ to organise ‘space as a territorial patchwork of separate jurisdictions, each of them corresponding to a traditional community that consists of native subjects bound together by their ethno-cultural traits’.60 In the context of southern Kaoko, however, such assumptions of territory, community and jurisdiction are problematic, with jurisdictions overlapping and many land-use communities divided in terms of factional and political belonging (also see Chapters 4 and 16).

Given overlapping jurisdictions and factional dynamics, post-colonial state policies have arguably exacerbated existing struggles between competing TAs over territorial claims. On a local level, this involves competing headmen vying for state and local recognition,61 which, if given, would ensure that such places become territorially integrated into specific TAs, providing them with the legal authority to allocate rights to land within these places. In Ozondundu and neighbouring conservancies specifically, the Otjikaoko Traditional Authority were vying for power and authority in a context historically dominated by leaders affiliated to the Vita Thom and Ovaherero Traditional Authority. Yet migrating households likewise played a role in these struggles over territory, as discussed in Section 6.5.

To better understand how these local place-based struggles were co-shaped by larger contestations over territory, belonging and authority, it is necessary to briefly discuss some of their historical precedents. Importantly, political belonging and affiliation in Kaoko and intertwined struggles over land and authority were, and continue to be, strongly shaped both by complex histories of migration and displacement, as well as the politicisation of ethnic idioms. The majority of Ozondundu households enacted their social belonging to a larger pan-Herero society62 and traced their social histories to central-west Namibia (the Omatjete area, north-west of Omaruru). From here their ancestors fled during the German colonial and genocidal wars (1904–1908). As much as this history is shared, it is also coloured by divergent and idiosyncratic migratory pathways. These migrations, and the movement from place to place it entailed, were mainly negotiated through extended kin-networks, and relations of patronage.63

For instance, along the way some families remained in places further south (for example, in Otjitambi close to Kamanjab). Others again continued north, including to places in eastern Kaoko and some into southern Angola, re-migrating back into Kaoko at a later stage. From here, households incrementally moved to and settled in Ozondundu, especially from 1910 onwards when Angola’s administration changed from military to civil rule, and again with the end of German colonial rule in Namibia 1915.64 Many households who initially settled in southern Kaoko were forced to move north again due to the appropriation of land during the South African colonial regime. Later, the same families were once again forced to migrate north-west (for example from Otjovasandu) between 1929 and 1931, during one of the major forced removals in the South African colonial history.65 These migrations happened as the colonial state consolidated the notorious “Red Line” (later the Veterinary Cordon Fence, VCF), a border-making process which involved negotiation and contestation66 (see Chapters 1, 2, 13 and 14). For instance, during these forced removals one headman (Gideon Muteze) and his followers managed to negotiate with the Native Commissioner in Outjo to be resettled in Otjapitjapi, a place in Ozondundu he had known previously. In other words, Ozondundu, like much of Kaoko, was constituted through overlapping historical and household migrations, including within a wider culturally heterogeneous region (see Chapters 5, 7, 12, 13 and 14).

Yet despite a shared sense of wider ovaHerero belonging, some in Ozondundu identified with what was termed the Ndamuranda section of Kaoko’s society, who display and perform their affiliation to the chiefly line of Maherero (an ovaHerero leader based in Okahandja in central Namibia in the late 19th century): they were thus associated with those who migrated and re-migrated into Kaoko during later years. Divergent migration histories were crucial in shaping political belonging within this context. However, these shifting affiliations and the making of shared identities were also strongly refigured during the period of colonial indirect rule.

Specifically, the continual political mobilisation of ethnic idioms, embedded within a “tribalistic” discourse and the favouring of the “Herero” section by the colonial state, worsened already existing tensions between emerging sections of Kaoko’s society and chieftaincies.67 These tensions were magnified through the implementation of a livestock-disease control programme during the late 1960s, leading to some leaders eventually agreeing (after initial resistance) to cooperate with the authorities, whilst others resisted. Two strongly opposing factions formed: those perceived to be in close collaboration with the colonial administration, referred to as the “small or minority group” (Okambumba) and who constituted mostly “Herero” (and Ndamuranda) leaders; and those in opposition who became known as the “large group” (Otjimbumba)—the majority group constituting the “Himba/Tjimba” grouping.68

By the 1970s these tensions had spiralled into a violent regional conflict.69 The conflict gave rise to kin-based identities rooted in divergent ‘politico-ethnic formations’70 as well as a nativist politics of autochthony, with the “Herero” section (and particular patriclans in this section) accused of being “intruders” and “outsiders” in the region (also see Chapter 3 for discussion of this discourse of “intruders” in current circumstances in north-west Namibia). Historically a continuity and mutual interdependence between local and regional-scale political organisation emerged,71 with first-comer/late-comer relations and ancestral validation orchestrated and contested at different scales and embedded within an “ethnic idiom”.72 Moreover, ‘what had previously been considered a disparaging ethnic classification’, namely “Tjimba”, which historically had referred to herders who lost most of their livestock, became ‘the foundation for a new form of political consciousness’, including one rooted in struggles against marginalisation and colonial (and elitist) rule.73

This conflict led to a breakdown of cooperation between chiefs and kin-based shared land-use communities and gave rise to new forms of political belonging. As one person74 explained: ‘[w]hen initially […] when you could say because I have found rainwater at Omao and I will take my cattle and simply go and stay, this was no longer the case’. In Ozondundu as well, households were divided in terms of factional belonging. For example, some would associate with a “big group” or “Tjimba” political positioning with such forms of belonging stretching across generations and associated with particular patriclans and competing first-comer and authority claims.75

Moreover, these conflicts happened against the backdrop of the declaration of Kaoko as a military territory in 1976 and the larger national liberation struggle. Between 1978 and 1981–1982 a devastating drought also hit the region, leading to up to 90% livestock losses and famine (also see Chapter 2). Political instability was further exacerbated by the civil war in former Portuguese Angola.76 This complex chain of events forced many men to join the South African army and police in the 1980s.77 Following the Turnhalle Constitutional Conference in 1975, the South African administration introduced ‘second-tier authorities’ meant to be ‘self-governing’ ethnic administrations of the homeland areas78 (also see Chapter 13). This meant that all of Namibia’s otjiHerero-speaking societies, including the ovaHimba, were subsumed under the ‘Herero Representative Authority’.79 This change signalled a shift in which local political belonging was increasingly refigured within emerging national party politics and the liberation struggle.

With the establishment of second-tier authorities, delegates of both the “small” and “big” groups were appointed. Soon, however, members were using the power of the new governing body ‘to appoint their own group’s headmen’, thereby polarising villages.80 During this time the Herero Representative Authority was dominated by the DTA81—a coalition party formed after the Turnhalle Conference backed by the South African administration. Yet with these dynamics, the DTA eventually had to choose sides. In the end, they supported the large group faction and, as a consequence, the small-group leaders opted for SWANU,82 who later allied with the NPF,83 with some later shifting to other affiliations post-Independence, including to SWAPO.84 It was also during this time, with the ‘political party spirit’ being ‘high’, that local leaders and the headman from the ‘area of the mountains’—i.e. Ozondundu—were said to have managed for their area to be proclaimed as an independent ward. 85

As detailed, after Independence, multiple TAs were recognised in southern Kaoko, with jurisdictions overlapping and shared land-use communities divided in terms of affiliation. The Otjikaoko Traditional Authority was politically shaped by autochthonous claims and identified with a former “Himba”/“Tjimba” and “big group” (Otjimbumba) section in Kaoko. The Vita Thom Royal House’s members, on the other hand, were associated with those who migrated and re-migrated into the region during the first decades of the 20th century, and with the legacy of a minority “Herero” or “small group” (Okambumba) section and the colonial state-supported elite. In the context of regional migrations, these long-standing internal tensions found new expression in contested places. Moreover, minority factions and those who felt unrepresented began appointing their own headmen and affiliating to oppositional TAs in a bid for state recognition.

In addition, given Kaoko’s political histories,86 in the first decade after Independence many local leaders and communities were still associated with oppositional political parties, as opposed to the rest of the northern regions where the governing SWAPO party dominated.87 With struggles for state recognition by competing TAs, leaders and headmen, Kaoko soon became embroiled in a protracted power struggle: Ozondundu, for example, was almost equally divided in terms of SWAPO and DTA (now PDM88) supporters in 2015.89

For many, this political fragmentation and the proliferation of local headmen were seen as contributing to the breakdown of local institutions of land and resource governance, and the root cause of the dispute. Such perceptions were not limited to southern Kaoko. In reflecting on this situation, one of the newcomers explained things to me as follows:90

K: In our area, the ovaHimba area, the reason you always hear that people are being chased away is that we don’t settle in a good way. If it was in our ovaHimba area,91 you would have looked at the homesteads they settle in a disorganised order that damages the grazing area, that’s why the cattle are dying because they are overgrazing. If you talk to someone about it, then it’s a big fight so people are just settling the way they want.

E: Has it changed from how people used to settle in the past and now, especially where you come from?

K: It has changed totally because nowadays you cannot tell someone to change the direction of grazing so that you can conserve the grass for calves for later then you end up quarrelling or fighting.

E: Why do you think it has changed now?

K: Why it has changed is because previously the headman was only one in the area and now the political parties also become more, e.g., DTA, SWAPO, UDF92, NPF, etc. so every headman is on his own with his followers and everyone does not mix with the people falling under the leadership of the ones who are settling there. The above-mentioned leaders from the different parties are competing against each other and are jealous of each other because everyone wants to have more followers, e.g., each one needs 50 followers, and all those 50 people will come from Etanga and Owambo land so their family will also want to come and live in the area and they will not refuse because they need to increase the number of their people in their party.

To better understand how these dynamics played out on a local level, Sections 6.5 and 6.6 take a closer look at how the dispute intertwined with these socio-spatial, political, and factional struggles over authority, land and belonging.

6.5 Migratory drift and opolotika

Following Namibia’s Independence, more regional pastoral and household migrations took place within Kunene Region, including in response to environmental and population pressures and drought events. This migration situation was exacerbated by the initial lack of a clear national state policy on the allocation of land within communal areas during the first decade post-Independence.93 Article 21(h) of the Constitution also stipulates that any Namibian citizen can freely settle on communal land—provided he/she follows local procedures for acquiring access. This created a ‘legal vacuum’94 exploited by many seeking to access land, including within Kaoko.95 Internal struggles over authority and factional belonging also generated a perceived and constructed ‘interstitial frontier’;96 it created places which became politically defined and subjectively perceived as open to legitimate “intrusion”.

Bollig97 observed that already during the mid-2000s there was a large out-migration of households southwards from the northern Epupa constituency, as well as north into southern Angola. These migrations were fuelled by the search for better pastures due to high livestock numbers and ecological degradation, with stocking rates in northern Kaoko higher than those in southern and central Kaoko,98 leading to crises concerning pasture management.99 Migrating households had to rely on a range of spatial, social, and political tactics to navigate their mobility. One such strategy was to try and establish satellite and drought-period cattle-posts and to then subsequently negotiate one’s legitimacy and belonging, often through claiming socio-political affiliation as well as through maintaining translocal place-relations.

For example, one of the heads of a newcomer homestead in Ozondundu, Tjimbinaje,100 was in a polygynous marriage with four women. Their household, like many others, had initially migrated from northern Kaoko to Anabeb Conservancy, before creating a satellite cattle-post in Ozondundu from 2012 onwards. During our acquaintance, we mostly met with his third wife and his cousins, nephews and nieces who took care of the livestock. Later, I learned that the senior wife headed and managed the ancestral homestead in Oruhona in northern Kaoko (see Figure 6.2); the second and third wives moved and managed households and livestock between southern Kaoko and Opuwo; and the fourth wife mostly managed another cattle-post in northern Kaoko, at a place called Okorue. Thus, although these north-south migrations were permanent for some, they were temporary for others, generating translocal and gendered place relations and mobilities.

In other words, for many ovaHimba newcomers in Ozondundu, their ancestral homesteads and, in some instances, their main homesteads and other cattle-posts, remained in northern Kaoko (often more than 200 km away)—with livestock herds separated between these multiple and distantly-located places. This separation of livestock herds constituted an important pastoral strategy to mitigate the risk of livestock losses in drylands, whilst simultaneously being an important practice for gaining additional rights of access, over time. Following Diallo,101 a large number of the north-south regional migrations could be characterised as ‘migratory drift’ in which patriclans, over the long-term, gain or try to gain new or additional territory and land. Given the importance of ancestral land-relations in governing land-access within this context, the negotiation and establishment of translocal place-relations produces and re-produces relations across locales, integrating them territorially.102 Hence, people and groups are emplaced even when they move, dynamically moving with and within their institutional embeddedness, including their clan and political belonging. Given this ‘situatedness of mobile actors’,103 together with the socio-spatial and political practices deployed by newcomer homesteads, this situation generated larger concerns not only over dwindling grazing, but additionally over long-term claims to land by particular groups. These translocal mobilities were also locally commented on, valorised, and disputed.

For instance, with the arrival of disputed newcomers in Ozondundu, several residents contested their genealogies of arrival and intentions, as detailed in an interview with a senior stock owner, Karumendu:104

K: The settling of people procedurally starts like for, e.g., some people come to ask and then the surrounding areas will discuss the matter to settle the applicant temporarily who would go back after the drought. These people are settled for a while until rain starts, now they have to go back. If the place from which a person came from didn’t get enough rain, then the place where a person is settled temporarily, his period of stay can be extended. So, whatever is to be agreed upon should be done in consultation with all the people in the area. That was a manner in which things were done when we grew up. Nowadays, things are strange, people from other areas just come to Otjomatemba without any consultation or permission and chase their cattle into a kraal [livestock pen] they have just found in a place and start separating the calves from the cows.

V [translator]: Which kraal?

K: It is an old kraal but it does not belong to them.

E: Meaning that all who came into Otjomatemba did not ask for permission?

K: Seven people asked for settlement and were accepted, after they had received rain, they went back. The current ones never had permission.

There is one person, his boss is at Opuwo, that one has got permission that’s why we didn’t chase him away.

E: Why does he think this problem is starting now, why is it happening now? [Addressing the translator]

K: The problem is with the ovaHimba people, and the reason is unknown, it is them who do not consult but start building kraals everywhere they like because the ovaHimba people are not consulting anyone.

V: Why do they want to be settled everywhere?

E: Does it perhaps work differently to settle in their areas where they are coming from?

K: We found out from people coming from that side that they have also done the same way at the places they came from, and it has created a dispute among them. We don’t talk to each other. At Otjondunda all those people that you find there are illegal, no one is born there. They settled by force and others continued to settle all over without permission. I heard that some people went to report the case to the police.

As noted above, the dispute generated a particular politics of belonging in which “ovaHimba people” or the “Himba” were primarily considered “strangers” or “illegal” migrants. Despite this ethnic idiom, however, what was at stake was rather the perceived forceful settlement practices of some, including by tactically navigating the drought situation. Such practices meant there was animosity from the start, as noted above: ‘we don’t talk to each other’. Such animosity was closely linked to the newcomers’ continually endowed strangerhood—with both the politics and practices of arrival playing a crucial role in the negotiation of sociality and belonging within southern Kaoko and the integration of newcomers (also see Chapter 3).

With the onset of the dispute in Ozondundu, wider tensions in southern Kaoko were already rippling out, in some cases erupting into conflict. As one resident105 of Anabeb Conservancy south of Ozondundu explained:

[w]hen they came, they came to “ask for drought” (omuningire wourumbu), and we accepted. When the rain came, however, they were refusing to leave. This resulted in a conflict and fight at Okanamuva (a cattle-post). We were accusing them of not coming for drought, but rather to win over the place and the land. People were threatening each other with guns. Here (Anabeb Conservancy) there were no rains and even drought, but still, they were refusing to leave. We don’t have a problem with people—but it is bringing conflict to our areas.

Many of these settlement practices were criticised by drawing on a discourse of opolotika. As expressed by an interlocutor106 from the Anabeb Conservancy:

[f]irst, we did not know what they (the newcomers) were looking for. But it is because of opolotika. They want to take this area to belong to them.

Anthropologist John Friedman107 argues that the term opolotika has come to denote a specific material form and practice within Kaoko. Unlike the concept of politics, it does not refer to a “generalised notion of power”, but instead to practices by both political actors and parties, including competing TAs, in relation to Namibia’s post-Independence SWAPO108 government. As a normative discourse, people generally relate opolotika to ‘divisiveness, conflict, violence, death and war’—with it also used as a general ‘derivative of problems, or as a form of criticism, or as the act of quarrelling’.109 As an Ozondundu resident related:110

[i]n the olden days, people were cooperating. Now they brought in opolotika and this is dividing (okuhanika) people. One will settle people here and if you are deciding to leave to let areas recover then others will remain. In the past, people had a small meeting and decided collectively that now they must leave a certain area to allow it to recover. This is no longer the case, if you move now, you move by yourself. Things have changed. These days settlement is motivated by opolotika. It is changing things.

In the context of the dispute, opolotika was used as a social and critical commentary on the breakdown of land governance institutions and how this was connected to the political practices of competing headmen and chiefs, as well as the socio-spatial practices of particular newcomer or migrating homesteads. In mobilising a discourse of opolotika, these mobilities were perceived and commented on as settling primarily through force and/or conflict by negotiating rights access through oppositional TAs and headmen, and hence as dividing shared land-use communities. In addition, these translocal mobility and settlement practices were perceived as attempting to territorially integrate specific places within larger polities, and over time. Moreover, in mobilising a discourse of opolotika, the ‘conflation of local “traditional” chiefship with national party politics’111 was commented upon, including its political and social impacts locally.

For example, similar to Ozondundu and during the dispute, people explained that the newcomer ovaHimba homesteads at Otjondunda (Anabeb Conservancy) were rumoured to have been permitted by only one headman in an area governed by multiple headmen. After some years the situation became out of control, as more and more newcomer herders and livestock migrated into the area and the headman left. Thus, there were recurrent discussions with regards to the belonging of these homesteads—despite most of them having lived there for more than eight to 10 years.112 Similarly, as noted in Section 6.3, during the dispute Ozondundu also had two headmen, each affiliated to different TAs. While the one headman (Muteze) was state recognised, the other headman (Herunga) was not. In becoming appointed as a new headman, Herunga’s claims to authority had to be socially and culturally legitimised. Some of the migrating households tactically navigated this process. For example, in generating counter claims against their proposed expulsion, and to delay their exodus, several ovaHimba newcomers in Ozondundu drew on pastoral notions of conviviality and patronage. As one person113 explained:

[a]ll of the ovaHimbas, when they came to settle, Herunga did not know about them, but it was claimed that they were settled by Herunga because they are in his area, but he said, “How can I settle people while I was in Marine114 or did I settle them while I was there?” He said if people are claimed to be settled by him then they must remain there because he will accept them as they are given to him, so is it how the people became Herungas.

Such practices were welcomed by Herunga in the spirit of expanding his follower base and to strengthen his claims to intersecting ritual and political authority. It thus affirmed his position as the “owner” of the place. Yet, locally, and as shown in Section 6.3 and discussed in more detail below, such authority claims, and settlement practices were disputed, including by mobilising long-standing social norms, competing normative orders, and an ethnicised politics of exclusion.

6.6 Contesting place and authority

Importantly, the boundary between those considered as dwellers or residents (ovature) and those who were on the move (ovayenda) was performed and negotiated during dispute deliberations, rather than as an a priori differentiation. Given that land-use boundaries were overlapping and networked, being and becoming a resident was largely a question of relationality. It was a fact that had to be relationally established, including over time. Consequently, and as I will discuss below, places were often sites of contestation, with interwoven struggles over authority, belonging and mobility a crucial arena in which historically-grounded and situated notions of residency—and thus of land-rights—had to be established and re-established. Key in this process was the question of authority, i.e., who had the legitimate authority to integrate and settle newcomers, with this question of authority closely intertwined with a place-based politics.

As explained by several persons, customarily both grazing and settlement rights within places had to be verbally negotiated according to social norms (okuningira ousemba, literally ‘to talk words’). First, the most senior male or female household member visits the place without bringing any livestock. The person would then approach kin (if there were any) who would refer them to the senior councillors, who in turn would take the message to the headmen. It was also seen as good practice for the newcomer to visit and acknowledge known first-comer homesteads. This process of negotiating access was also bureaucratised, and a livestock moving permit system was institutionalised already during South African colonial rule. Post-Independence, and after the TA Act came into force in 2000, permission papers had to be issued by state-recognised TAs, in this case, local state-recognised headmen. Migrating households require a permission paper both from their place of origin, as well as the place of migration, and have to subsequently present their livestock at the local veterinary extension office or clinic for the issuing of a livestock movement permit. Still, drought-related, and temporary access rights to pastures between overlapping land-use areas, were predominantly allocated through informal verbal agreements, based on mutual reciprocity. It was these practices that opened up spaces of ambiguity where claims could be made on both land and resources, including through relations of patronage and affiliation and specifically within contested places such as Otjomatemba, characterised by political fragmentation and overlapping migrations and mobilities.

Moreover, despite the social norms articulated above, how exactly the place or place-boundaries should be defined that informed who the collective resident households or local authority were, were in many instances a matter of contestation—with especially disputes providing a generative platform in refiguring these boundaries. For example, during the dispute, and for many residents, Otjomatemba was seen and dwelled in as a dry season cattle-post settled during the early 1990s (see Figure 6.2). It was narrated as a cattle-post belonging to Otjapitjapi (an ancestral place in Ozondundu Conservancy) which was subsequently settled, especially with the drilling of its borehole, and hence falling within the jurisdiction of the state-recognised headman, Muteze (see Chapter 7). However, this place-genealogy was contested. From the perspective of others, Otjomatemba was an “old place”, characterised from the start by ancestral homesteads, and established during the 1950s. These divergent histories of place-formation and ‘first-comer narratives’115 were themselves emplaced, i.e. they were narrated and performed through tracing past migratory pathways, the location of graveyards and burial sites, ruins of former homesteads, and the social histories of water wells.116

At the core of Otjomatemba’s competing settlement narratives were local struggles over authority, territory and belonging. In constructing Otjomatemba as an “old place”, a historical narrative in which Herunga’s (classificatory) father was the first to have settled, Otjomatemba was legitimised, making an argument for his claims to ritual authority and as the “owner” of the place. At the same time, and through his political affiliation to the Otjikaoko Traditional Authority, Otjomatemba’s territorial integration within other larger polities was enacted. Such claims were meant to be strengthened through the settling and integration of newcomers.

Yet, in response, others mobilised an inherited hereditary chieftaincy model and colonial tenure boundaries to dispute such claims and to re-assert Otjomatemba’s place-identity within Ozondundu’s jurisdiction. As one senior councillor117 lamented:

[t]here are rules (oveta) for movement and settlement—these rules came from us, but also not from us exactly, it was from the government (ohoromende). In the past, the South African government (ohoromende wa Suid-Afrika) decided to give the power to the headmen. While they were doing that, they were also giving each headman a place to settle, with people supporting them. It was working like that. First, it was the government, but now it is natural. But now things are changing. There were only a few headmen in the past. Now, some are forcing themselves to become headmen, so that they can also get paid by the government. Here, there was only one headman, he was living in Otjapitjapi and was buried in Otjapitjapi [east of Otjomatemba on Figure 6.2]. He was replaced by his son and this son also died, and then Muteze was appointed. It is the headmen deciding if there are too many people in one place. Nowadays they are forcing themselves to become headmen, those who are not established. And the established ones are having trouble.

There is a law (oveta). We set up the meeting. Last year we had the meeting. The reason that we are having so many meetings is because of the two headmen. The people are divided (okuhanika). With that, some people are going behind and telling the Himba homesteads (newcomers) not to leave. And then the Himba homesteads are talking as if they are deciding that for themselves—not like they heard it or were told by someone.

Evident in this quote was an understanding in which headmanship and authority were intimately entangled with the making of colonial indirect rule. In other words, there was an historical consciousness concerning the “invented” character of the institution, although also foregrounded here was its subsequent naturalisation—legitimised within existing institutions. As emphasised: ‘he was living in Otjapitjapi and buried at Otjapitjapi’. Even so, it was the state-recognised and hereditary headman who was ‘controlling the area’ and ‘deciding if there are too many people at one place’, rather than those associated exclusively with institutions of ritual authority. This narrative was strongly contesting competing claims—including how these were perceived to be dividing people, leading to ‘many meetings’.

Likewise, in this context, residents mobilised a discourse of opolotika to comment on these struggles over authority and the territorial integration of Otjomatemba. As one person expressed:

[t]he problem came because Herunga wanted to establish a clinic, and Muteze resisted. Herunga used to be Muteze’s senior councillor. Now they are fighting […] “Where is your father’s grave?” It is just opolotika.118

Generally, this discourse was rooted in a juxtaposition to ombazu (custom, or tradition). As one person emphasised: ‘Herunga just opolotika—Muteze is connected to ombazu’. For Friedman,119 a distinction between ‘tradition’ or ‘custom’ (ombazu) and ‘politics’ (opolotika) can be made as follows: opolotika referred to dynamics which have emerged after or with Independence and which are always changing, whilst ombazu was construed as ‘a permanent thing’ and relating to the inherited ‘patriarchal political order’ of state ‘recognised’ headmen and their territories. In making this distinction, ‘custom’ has come to work as a kind of ‘anti-politics machine’,120 mobilised to deflect the challenging of inherited structures of authority.121 In other words, these discursive practices aimed to delimit the registers within which the institution of local headmanship could or should be translated, delegitimising competing authority claims. At the same time, such discursive practices were reasserting particular territorial claims—more specifically, the integration of all the Ozondundu places under the jurisdiction of Muteze—and by extension larger chieftaincies and polities.

Furthermore, during the dispute, and in response to navigating these local factional politics, social norms were re-asserted, including holding senior councillors and competing headmen accountable. It was thus asserted again and again, that no one person, including the headmen, had the authority to allocate rights to access land: these decisions had to be taken collectively. In this regard the Ozondundu conservancy boundaries and membership were powerful symbolic tools mobilised to assert who exactly this collective was, particularly given that land-use boundaries were overlapping. Hence, internal frictions were eventually set aside in the face of a larger concern: perceived land grabbing by particular migrating households over the long-term.

This was evident in how, during the dispute, a wide-spread ethnicised politics of exclusion emerged (also see Chapter 3). Specifically, shared social norms and values and pastoral belonging were re-asserted through a normative discourse on “Himba mobility” as a negative form of transhumance. As one local councillor122 expressed this in Otjomatemba:

[w]e (referring to the residents of the area) and the ovaHimba, our attitudes, our ways in the home are not the same. While we are here, the ovaHimba […] they will move where the grazing is. They just follow the grass. When it is the rainy season, they are just moving around, creating several cattle-posts. OvaHimba are like this, if they come for drought and to settle at a place, if the rain happens to arrive, and you request them to leave, they will only refuse. And just imagine, their cattle are a lot.

Another senior councillor123 echoed these sentiments:

[t]he ovaHimba are cleverer than all of us. They are moving the cattle beyond the Red Line (now the VCF), even all the way to Outjo and Kamanjab. They separate their cattle. Many people are speaking to them and perhaps think that they are stupid—but you don’t know what is in their heads. The Herero have a different movement. Normally you have your ancestral homestead, with the ancestral shrine you belong to, but often there is no livestock. Rather you would have another established homestead. For example, my ancestral homestead is in Otjomaoru and I am permanently settled in Otjomatemba (both within Ozondundu). I would only go to Otjomaoru when there are funerals, weddings, or for the naming of children—for this reason, it is helpful to maintain a small house there.

OvaHimba grazes only for the animals, not for the veld. They finish the grazing everywhere. They will stay here in Otjomatemba and surrounding areas just for now, and then they will leave, without being chased away by the people. They will only stay until the grazing finishes. They overgraze until the seeds are gone.

“Himba” pastoral practices were thus construed as privileging mobility over sedentariness,124 with such land-use practices framed negatively (omundu wonduriro ombwii). For some, such land-use practices were construed as threatening future possibilities—both for communal conservancies, as well as securing inheritances such as land. As one interlocutor emphasised:125

[i]n Otjomatemba (in Ozondundu) we are working with the conservancy and the ways that the ovaHimba migrate, they will just settle anywhere, and this will chase the wild animals away. Behind the mountains, close to Otjitaime (the spring), we have zoned the area for the wild animals—but some of the homesteads are going that side and making a cattle-post. People in Otjomatemba want to make a rest camp there, for tourists—but now because of the cattle being there, the tourists won’t enjoy it so much, because they want to see the wild animals. People’s concern is also for their children, when the children are adults and then they start to make their homestead—where will there be space? The ovaHimba think that they will be staying permanently and then they will give livestock to their children, who will make a cattle-post, and in the end, it will be us having to leave the place.

In contrast, local spatial practices were presented as being intertwined with a different kind of territoriality. “Herero” mobility was said to be limited only to one area and construed as contained, rational and bureaucratised. Here, then, divergent forms of pastoral land-use and translocal place-relations were an ‘arena of contestation’126 and grounds for expressing shared belonging. Yet, rather than this being inherently about the assertion of ethnic differences and radically different land-use values, it was instead rooted in attempts to re-assert a particular normative and territorial order. In other words, these discourses were aimed at assembling solidarity within larger publics, with “Herero” mobility mirroring that of state rationality, and thus better placed to garner legitimacy. Emplacing these discourses within an ethnic idiom drew on long-standing engagements with the state (including TAs), as well as outsiders: invoking a pan-Herero solidarity that could potentially cut across the deeply seated internal political and factional divisions.

Hence, the dispute clearly generated a pronounced politics of belonging between “Herero” residents and “Himba” newcomers. It is important to emphasise, however, that in the everyday these boundaries were fluid, with both mobility and settlement navigated along intersecting axes of social and political belonging. To illustrate these dimensions, I turn briefly to two cases concerning ovaHimba newcomers whose belonging and settlement, although ambiguously situated, were not legally contested.

6.7 Integrating newcomers: The micro-politics of belonging

Locally, disputes were not necessarily about or only about conflict, but were simultaneously spaces critical for ‘enabling exchange and reciprocity’ and for identifying, establishing, and recognising ‘potential alliances through the process of reckoning relationships’.127 This approach afforded the flexibility and fuzziness characterising group and territorial boundaries in this context, these practices being crucial for maintaining long-term relations of cooperation in drylands (also see Chapter 5). Moreover, these institutions enabled the strengthening of interwoven claims of authority and land-rights by particular clans and lineages—as newcomers could be integrated and legitimate authority relationally performed. Lastly, given the heterogeneity of patterned pastoral mobilities within Kaoko, disputes enabled situated processes of adjudication in which the norms governing rights to access could be (re)articulated in practice, including on a case-to-case basis.

Although access to pastures was a major driving force fuelling regional pastoral and household migrations, these mobilities were simultaneously motivated by other push factors, including interpersonal tensions between people and shared desires for autonomy. In talking with one of the ovaHimba newcomers, Kaire,128 whose settlement was in fact accepted within Ozondundu, he proceeded to provide an example, based on his own personal experience and migration from Etanga (see Figure 6.2):

K: Why we, the ovaHimbas, have started mushrooming in this area is because we are experiencing problems in our area. Let’s say you are staying at a certain place; you are born three and one is the firstborn. This first-born does not want you to stay in that place, so he always troubles you by creating conflict among you. Because you don’t want to have a conflict with him you prefer to go to stay at another place—so that you can only come to visit him for a short time or when there is a family-related problem like a death. When you are leaving you ask like 10 calves to go with you, but you do not tell him the truth: that you are going because of the conflict that he is creating among you, but you rather say you met people from a certain place and asked for grazing and you have been approved. When you have come to the place you ask for permission to stay, and they first will want to know why you have moved from your place. You will tell them the story of why you want to live there. For instance, you would start telling someone that it is your relative that you have a problem with, your elder brother, and you want to start a new homestead so that you can stay alone. They will listen to you and accept you [...] [not clear] then you will be settled. So, you now go and visit him just to see their wellbeing. Some people will just move in because they have been attracted by the area by just driving through or by foot to come and visit here from Etanga. Do you know where Etanga is?

E: Yes.

K: By just passing through by car they are attracted by the beauty of the place and decide to come and stay without asking permission from the local people. After the people have realised his stay, they will ask how he came in and he will say he has asked for permission to stay but then in reality is not the truth. The said person is the one referred to as an illegal resident and he must be prosecuted. That is the situation right here why people are being chased away. Some people came in with permission and some are just sneaking in.

As emphasised, together with respecting the set social norms, the reason for requesting settlement likewise informs the integration of newcomers, with flexible belongings at work. Important here, however, was also his household’s intersecting social, economic, and political locatedness and genealogy of arrival. Kaire’s migration from Etanga to Ozondundu was negotiated through the patronage and livestock movements of his wife’s brother, a headman from Otjihama (close to the urban centre of Opuwo)—matrilineally related to Ozondundu’s state-recognised headman (Muteze). Patron-client relations were thus often characterised by household migration by the “clients”, while the “patrons” negotiated rights to access. Moreover, kin-relatedness—as a key variable in governing rights to access—intersected with socio-political affiliation and livestock wealth to open possibilities for mobility. This case was still mentioned during the dispute, which pointed to the fact that claims to residency was an ongoing process, and one that had to be negotiated over time. For instance, in hearing about the dispute, the headman from Otjihama gifted a goat to be slaughtered for food in support of the dispute proceedings, thereby strengthening the acceptance of his herds and Kaire’s household within the place.

Similarly, another case discussed during the dispute was that of Meundju, the sister of the head of a large ancestral homestead in Ozondundu. She had married an ovaHimba man from Etanga and given tendencies towards ‘patrilocal postmarital residence’129 had initially left Ozondundu. However, she returned some years before to take up the post as a primary school teacher. In so doing, she had brought livestock belonging to her, her husband, and her husband’s family and thus to her affinal kin, mainly due to the severity of the drought in northern Kaoko. Given that Meundju’s husband was employed in South Africa, it was her husband’s family—specifically his younger, married brother—who was taking care of the livestock. Unlike other ovaHimba homesteads, Meundju’s affinal kin were not asked to leave; their newcomer status was shaped by their close kin-relatedness and the fact they followed the “right” procedures in acquiring rights to access. At the same time, their settlement status was still imbued with ambiguity, with some residents mobilising patrilocal settlement norms to contest these livestock movements and in-migration. Counter-claims relegated these tactics to opolotika, and attempts by some to divide resident homesteads.

Importantly, and as shown, membership in kin or clan-based groups are not “a given”, and often intersect with politico-ethnic and factional belonging to shape highly situated forms of belonging. In other words, people’s social positioning is ‘constructed along multiple axes of difference’130—including kinship, gender, and ethnicity—with such axes co-constitute each other in shaping situated rights to use, access and/or dwelling. Moreover, ‘being an insider or an outsider is always work in progress, is permanently subject to renegotiation and is best understood as relational and situational’, with sociality and relationships being key in how ‘being and belonging are translated from abstract claims into everyday practice’.131

In this context, the boundaries between residents and newcomers were often intentionally imbued with ambiguity. This ambiguity allowed for the negotiation and re-negotiation and the reckoning of relationships.132 However, these practices were not devoid of power struggles, mistrust, and division—with especially the legacies of factionalism as a key generative force in place-based politics, including migration. As alluded to, interpersonal tensions combined with the pressures on pastures and land, in some instances becoming a push factor for regional migration—with persons preferring to co-reside with strangers, rather than close kin, as a means to maintain relationships over the long-term. In this case then, kin-relatedness is not always the main or even preferred relational thread opening and closing possibilities for mobility and settlement, with political affiliation and relations of patronage providing alternative migratory and co-residency pathways.

In the context of the dispute, and as shown, what eventually differentiated the contested newcomers were their claims that Herunga, as a then non-state recognised headman affiliated to a minority faction, had allocated rights to access and settlement to them, as well as their initial arrival under the guise of drought-related temporary access. In an attempt to delegitimise such practices, local leaders eventually turned to the state courts.

6.8 Negotiating and re-asserting land-rights

The opening of the legal case was motivated not only by a concern for pastures but linked with the interwoven authority and land-rights of particular groups within southern Kaoko. Specifically, it was informed by the perceived marginalisation of the former “minority”, yet economically and politically powerful group of “Herero” and Ndamuranda, and their leaders within the TA structures after Independence. Such perceptions were fuelled by the centralisation of authority and legal power through state-driven communal land reforms in the TAs.133 Moreover, this situation, combined with the ongoing north-south regional migrations of ovaHimba households, located this dispute as a territorial, as much as a land and grazing, dispute.

The legal case that opened with the dispute documented here was eventually not supported by any state-recognised chiefs within the TA official structure, although it was led by a senior councillor (Muteze) of the Vita Thom Royal House TA. This situation initially weakened their case, resulting in some of those involved declaring that ‘the ovaHimba are ruling’ and that ‘all the chiefs were now ovaHimba’. In recent years, ovaHimba especially (along with other groups in Kaoko) have gained international recognition for their Indigenous rights,134 this recognition bolstering anxieties regarding the ancestral validation of particular groups over others within southern Kaoko. Such anxieties were heightened by the liberal rights engendered by the Namibian constitution. As one person135 who was part of the subsequent legal case reiterated:

[i]t is because of rights—people are misunderstanding it and thinking that everyone has the right to move whenever she/he wants, and to settle wherever. We need procedures. First, we approached the police, then the governor’s office—both of whom did not have any power to force people to move. Then we went to the Ministry’s office. They also did not have the right. Everyone was referring us to the Magistrate’s Court. Then we decided to look for a lawyer. A lawyer is the fastest way.

This rights-based citizenship was seen as threatening vernacular group-based rights to land, with such rights having to be established and re-established over time and through specific practices.136