8. Eliciting empathy and connectedness toward different species in north-west Namibia

©2024 L. Z. Katjirua, M. S. David & J. Muntifering, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0402.08

Abstract

This chapter turns to research with young people in north-west Namibia to ascertain their perceptions and understandings of “wildlife”. The aim is to better understand how young members of communal-area conservancies in north-west Namibia know and perceive the value of selected indigenous fauna species in these areas, alongside domestic livestock—specifically goats (Capra hircus). This study is set within a context in which tourism in Namibia is understood to greatly contribute to Gross Domestic Product, with Namibia being home to animals whose value is linked with their contemporary scarcity. Such species include black rhino (Diceros bicornis bicornis)—monitored and celebrated through organisations and campaigns such as Save the Rhino Trust and the Rhino Pride Campaign—as well as lion (Panthera leo), and oryx (Oryx gazella), all of which draw tourists to Namibia. Whilst these wild animals need to be protected at a global level, nationally they are also Namibia’s pride, even being pictured as nationally important symbols on Namibian bank notes.

8.1 Introducing a survey on “nature connectedness” in

north-west Namibia

Indigenous fauna in southern Africa is associated with wildlife-based tourism, a means to enhance socio-economic aspects and livelihoods, especially for communities living in association with wildlife (Chapter 3). At the same time, returns to such communities may be questionable and regarded as minimal (see discussion in Chapter 5).1 On the other hand, wildlife and other animal species can make significant contributions that outweigh negative perceptions.2 Additionally, animal species are accorded local values, including relational values and human connectedness.3 To improve outcomes for biodiversity protection, a “new conservation” has advocated for a more people-centred approach that harnesses human values for wildlife.4 Central to this focus on “harnessing values” is designing and delivering interventions that lead to more excellent pro-conservation intentions and behaviours by people, an explicit aim of community-based conservation in Namibia. In particular, the aim of this chapter is to examine and elicit empathy and connectedness amongst young people towards conserving endangered black rhino (Diceros bicornis bicornis) and other animal species.

In addition, support organisations, the government, and local communities are working tirelessly to combat the challenge and consequences of poaching, especially illegal hunting of black rhino, an endangered species with high conservation and tourism value on communal land and protected areas in north-west Namibia.5 Geographically, many of these animals are in areas surrounded by communities that manage and benefit from wildlife through the CBNRM programme. Strict anti-poaching measures, habitat protection, community engagement, and international collaboration are essential to these efforts.6 It is in fact noticeable that in recent years illegal hunting of rhino is more a threat in Namibia’s protected areas and on private farms than on communal land,7 where instead blasting for mining is threatening rhino populations and associated tourism investments.8 To secure a future for rhinos, continued effort is needed to raise awareness, allocate resources, and implement effective strategies to ensure their survival for generations to come.9 Today’s youth will be the future leaders of communal area conservancies in north-west Namibia where rhino and other valued wildlife species are present, with conservancies aimed at both protecting these animals and catering and caring for the communities living alongside them. The possibility of rhino extinction in Africa is a significant concern today, and dehorning has been employed especially in southern Africa to discourage poaching for their horns.10 The loss of these iconic creatures would be a tragedy in terms of biodiversity and would disrupt the delicate balance of the ecosystems they inhabit.

This chapter reports on a survey conducted in 2021 among young people in north-west Namibia (Kunene Region), to shed light on their perceptions and attitudes towards wildlife conservation. Respondents showed a keen interest in engaging with conservation efforts, with a significant majority expressing willingness to contribute. Gender distribution in the survey was balanced, and a large portion of participants had a higher secondary level of education. The survey’s findings reveal that family ties to the tourism industry influenced respondents’ knowledge about different animal species. Goat (Capra hircus) farming is widespread, leading to frequent interactions with goats and a sense of their importance within households. Rhino and lion (Panthera leo) encounters are less common, with family members working in rhino conservation and Lion Ranger roles (as detailed in Chapters 17, 18 and 19) potentially influencing these interactions. Perceptions of various animals were explored, showing diverse viewpoints. The oryx (Oryx gazella, also known as gemsbok) is recognised as a national symbol and an essential contributor to tourism. Goats are valued for their role in livelihoods but face challenges like drought and theft. We proceed by describing our survey methodology and discussing the survey results.

8.2 Methodology

Our survey was administered among young people aged between 18 and 35 years, in the town of Khorixas and in Torra and Sesfontein conservancies, Kunene Region. Focus groups and semi-structured interviews were conducted, with a total of 149 questionnaires administered in the study area. This diverse methodological approach allowed for a comprehensive analysis of perspectives and opinions among young people in our Kunene Region study areas. Four different animal species were focused on in this study, as outlined above: namely, lion, rhino, oryx and goat. These four species provided insight in terms of our exploration of human relationship, connectedness and empathy with this selection of animal species.

8.3 Findings

This section dives into the results generated from our survey. We focus first on the demographics of respondents, outlining results by age groups. We then document responses to specific questions used to elicit senses of relationship, connectedness and empathy for our selected animal species.

8.3.1 Demographics

Table 8.1 details the characteristics of our survey respondents (n = 149). The respondents comprised an equal gender distribution (males 49.64% and females 50.36%), indicating a balanced representation of perspectives. A diverse range of ages were represented. Most participants were below 25 years (47.1%), comprising a significant proportion of younger respondents. Those between the ages of 26 to 30 accounted for 21.74% of the sample, demonstrating a substantial mid-range age group. Respondents older than 30 years constituted about a third of the participant pool (31.16%). The survey highlighted that a significant portion of respondents possessed a higher secondary level of education, underlining the relatively well-educated nature of our sample.

The questionnaire survey was administered in two ways: in Group 1, responses were evaluated under specific guidelines whereas Group 2 responded to the questionnaire autonomously. This difference in survey approach provided insights into the impact of structured questioning. Upon concluding the surveys, participants were also queried about their interest in engaging with conservation efforts. The results revealed a notable level of interest, with a majority (83.91%) expressing their willingness to contribute to conservation initiatives. This strong inclination towards conservation participation indicates a positive attitude within the surveyed youth population and suggests potential for impactful involvement in safeguarding the environment.

Table 8.1. Representation of survey participants (n = 149) in relation to the different variables.

|

Category |

Percent % |

|

Variable: Sex |

|

|

Female |

50.36 |

|

Male |

49.64 |

|

Variable: Age |

|

|

Under 25 years |

47.1 |

|

26 to 30 years |

21.74 |

|

31 to 35 years |

31.16 |

|

Variable: Education |

|

|

Lower Secondary |

24.81 |

|

Higher Secondary |

75.19 |

|

Variable: Survey Group |

|

|

Supervised (Group 1) |

48.97 |

|

Independent (Group 2) |

51.03 |

|

Variable: Support for Conservation |

|

|

Yes |

83.91 |

|

No |

2.3 |

|

Maybe |

13.79 |

8.3.2 Responses to survey questions

Below we summarise responses to specific questions in our survey.

1. Does anyone in your family work in the tourism industry?

About 60% of the respondents indicated that they have family members who work in the tourism industry. This connection to the tourism sector has given them a unique avenue to acquire knowledge about various animals, particularly those associated with tourism. Interactions with family members in this industry likely involve conversations, stories, and experiences shared within the familial context. First-hand accounts could encompass insights about wildlife behaviour, conservation efforts, and the significance of preserving natural habitats for tourism. Additionally, family members in tourism might offer guided tours or share educational materials, enhancing the respondents’ understanding of different animal species in touristic environments. Thus, family ties within the tourism sector can serve as an enriching source of information, contributing to these individuals’ awareness and appreciation of the diverse wildlife inhabiting Kunene Region and encountered through tourism-related activities.

2. Have you ever seen these specific animals: Oryx, rhino, lion and goat?

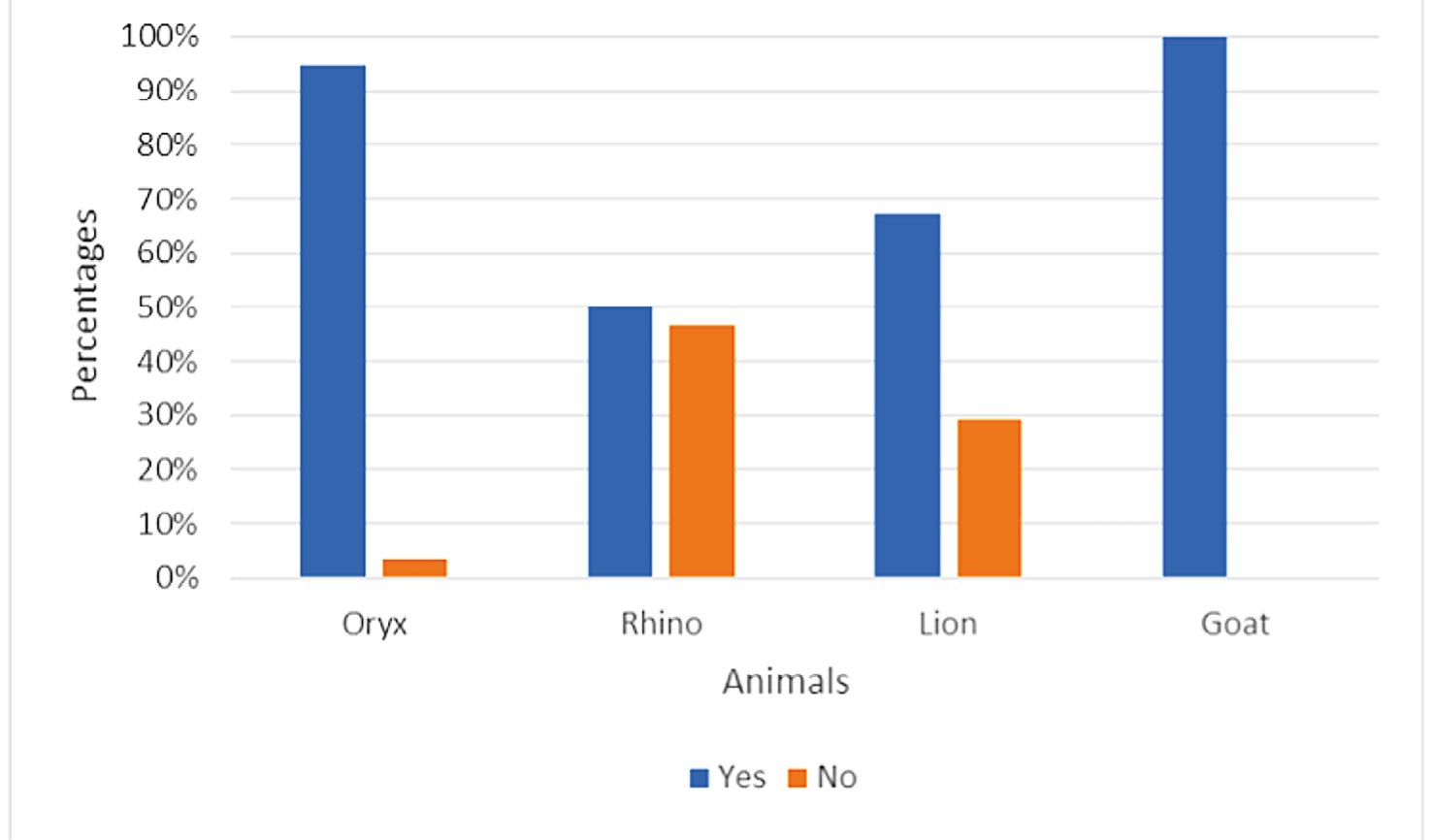

Fig. 8.1 Survey respondents’ sightings of four selected animals in Kunene Region. Source: authors’ data,

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Oryx and goats emerged as the most popular animals among the respondents, with more than half of the respondents reporting having also encountered lions (50.36%) and rhinos (53.02%) (see Figure 8.1). Given that 94.74% of the respondents and their family members engage in goat farming it is unsurprising that all respondents were familiar with goats: this shared agricultural activity creates frequent interaction opportunities with goats, contributing to their familiarity. Conversely, encounters with lions and rhinos were less common. Only a little over half of our respondents (53.02%) had seen rhinos, perhaps due to the involvement of their family members in rhino conservation efforts. A larger proportion of our respondents appear to have had familiarity with lions, perhaps related to lion predation of livestock in the area11 (see Chapter 14). Familial connections with Lion Rangers in the area may also play a role (see Chapters 17, 18 and 19), although it appears at the time of our survey that while there is a notable representation of family members engaged in rhino-related work, fewer family members are working as Lion Rangers (although this may have changed since the survey). Our findings highlight the significant influence that familial activities and occupations have on shaping the respondents’ exposure to and knowledge of these animals, ultimately contributing to their perceptions and preferences.

3. What are your perceptions of these animals?

The perceptions recorded for young people in our survey refer to the sentiments shared with us by our respondents. The results are presented below for the different animal species.

Oryx, Oryx gazella

Opinions provided by respondents regarding the oryx were primarily centred around recognising it as a significant national symbol. They associated the oryx with its distinct features, describing its unique physical attributes. Moreover, respondents acknowledged the oryx’s vital role within the community, particularly in bolstering tourism-related activities. A prevailing sentiment that emerged was the imperative to ensure the protection and conservation of the oryx, an important point given its decline in north-west Namibia over the last decade (see Chapter 3). Interestingly, a higher proportion of male respondents (42%) demonstrated the ability to offer detailed descriptions of the oryx compared to their female counterparts (27%).

While an oryx was associated with good things, there was not an urgent call for specific protection measures for the oryx, although a number of suggestions were made to continue preserving the oryx in the area. There is little difference between female and male youth in terms of how to keep oryx in their areas, with the exception that females emphasised more the beauty of the species and that such an animal should not be killed, while male respondents emphasised the ability of oryx to defend themselves.

Table 8.2. Observations and suggestions regarding the conservation of oryx (Oryx gazella) in north-west Namibia.

|

Response Category |

Respondents % |

|

|

FEMALE |

MALE |

|

|

Avoid killing oryx |

10.0 |

13.0 |

|

I like oryx and don’t want anyone to kill them |

21.4 |

7.2 |

|

Oryx has the ability to defend themselves through their long sharp horns and they use it well |

27.1 |

40.6 |

|

Oryx are animals that stay in the field that are protected by rangers |

5.7 |

7.2 |

|

The game guards look after the oryx |

14.3 |

13.0 |

|

Very important and community must protect the animals themselves |

34.3 |

34.8 |

Notably, within the age group spanning 26 to 30 years, respondents emphasised the oryx’s visual characteristics and the critical importance of its preservation. This variation in responses highlights multidimensional perspectives surrounding the oryx. While some respondents focused on its appearance and the need to safeguard its existence, others emphasised its role as a symbolic representation and a pivotal contributor to community-based tourism. These diverse viewpoints underscore the complex and intertwined nature of cultural, ecological, and economic considerations associated with this captivating animal.

Black Rhino, Diceros bicornis bicornis

Most respondents displayed a pronounced interest in advocating for rhino protection, primarily through engagement in conservation campaigns (53%). Notably, Group 2 exhibited a tremendous enthusiasm for active involvement in these campaigns compared to Group 1, whose responses to the questionnaire had been supervised more closely. Both groups emphasised the potential danger posed by rhinos when they perceive a threat, underscoring their ability to behave aggressively and even attack humans. Additionally, respondents from both groups concurred that the rhino population in the area has dwindled due to poaching, revealing a shared concern for survival of this species. Interestingly, the descriptions of rhinos provided by respondents varied widely. Some participants praised the rhino as being a small, short, and beautiful animal. In contrast, others offered different viewpoints, describing black rhino as having an unappealing, ugly appearance with large body size. The description of these characteristics by the youth is an indication of how they differently perceive the rhino, either by seeing it themselves or hearing from others.

The respondents’ evident interest in rhino protection underscores a collective commitment to conservation efforts. The nuanced differences in their descriptions of the rhino’s physical attributes highlight the diverse perspectives held by the surveyed youth. Moreover, Group 2’s heightened eagerness to engage in campaigns suggests a potential avenue for more dynamic and effective conservation initiatives. Table 8.3 summarises respondents’ responses to protecting the rhino overall. We found additionally that Group 1 were less aware of the work of Save the Rhino Trust (13%) in Kunene Region, believing that the government is solely responsible for protecting the rhino, whereas 50% of those in Group 2 indicated that Rhino Rangers are also responsible for protecting rhino. Both groups indicated that the rhino’s protection is the community’s responsibility as well.

Table 8.3. Responses regarding who bears most responsibility for protecting black rhino (Diceros bicornis bicornis) in Kunene Region.

|

Response (N=149) |

|

|

Community |

43% |

|

Conservancy Rhino Rangers |

41% |

|

Government |

16% |

|

18% |

Lion, Panthera leo

When respondents were queried about their associations with lions, several dominant responses emerged: their mighty roar, their contribution to generating income, their potential to attack humans, their perception as brave creatures, their depiction as serial predators, and their status as a vital member of the renowned Big Five group of animals in safaris. This collection of thoughts highlights the multidimensional perspectives that lions evoke in the participants’ minds. Conversely, when discussing reasons for not favouring lions, distinct viewpoints surfaced. Firstly, respondents expressed concern over lions’ propensity to attack humans. Secondly, a general perception of lions as dangerous and harmful animals came to the forefront. This perception was reinforced by lions’ proximity to human communities and their tendency to prey on domesticated animals, further accentuating their potential threat. The question of lion protection prompted shared sentiments among respondents from both groups. The responsibility for safeguarding lions was primarily attributed to Lion Rangers (whose work is documented in Chapters 17, 18 and 19). These insights illuminate the intricate blend of admiration, respect, and caution lions evoke in the respondents’ minds. The differing viewpoints on youth involvement in lion protection underline the complex nature of conservation strategies and the varying perspectives within the surveyed population.

Goat, Capra hircus

The respondents offered relatively sparse insights regarding goats. A notable observation, however, was that goats were recognised as holding significant value within households, actively contributing to the sustenance of livelihoods. Respondents highlighted their perception of goats as pivotal assets, vital for supporting households’ economic and practical needs. Additionally, respondents brought attention to the vulnerability of goats to environmental challenges, particularly drought conditions, which were noted as a factor leading to goat mortality. Respondents also acknowledged the unfortunate reality of goats being susceptible to theft due to their relatively easy target status. Both groups of respondents concurred on a critical point: safeguarding goats lies with their owners, also complementing the collaborative effort by NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations) and the national government, through various safeguarding initiatives such as the lighting of kraals, and compensation for losses caused by wild animals (under certain circumstances).12 This shared sentiment underscores the recognition of individual accountability in ensuring the well-being and protection of these valuable animals. While respondents may have offered limited commentary on goats, their shared insights shed light on the crucial role of goats for households, the challenges they face, and the underlying commitment to their care and protection.

8.3.3 How respondents feel

In this section we outline respondents’ feelings toward animals and also to Rhino Rangers, and their senses of connectedness to nature, town and home, as well as their knowledge of the latter.

Respondents reported strong feelings and opinions in relation to the four animal species included in the survey. Goats were clearly the most seen and cared for, followed by the oryx and the rhino. The lion was viewed the least favourably, presumably because of its tendency to see livestock and people as prey (also see Chapter 14).

An exciting observation emerged among respondents in terms of their knowledge and sentiments towards Rhino Rangers. One comment reads, for example, ‘the Rhino Rangers help provide our conservancy benefits from rhinos’. The respondents clearly emphasised the significant role of Rhino Rangers in facilitating sound management principles that will in turn enable them to receive tangible benefits from the local conservancies. This finding highlights respondents’ views of the vital contribution that Rhino Rangers make to the protection of this endangered species and its broader ecological and socio-economic values within conservancies. It is the shared recognition of the positive impacts of rhino rangers to conservancies among the respondents that genuinely captures attention, accentuating the critical role of these individuals in the intricate balance between wildlife conservation and community well-being. No doubt similar perspectives will also be emerging in relation to the newer institution of Lion Rangers in north-west Namibia, as documented in Part V (Chapters 17, 18 and 19) of this book.

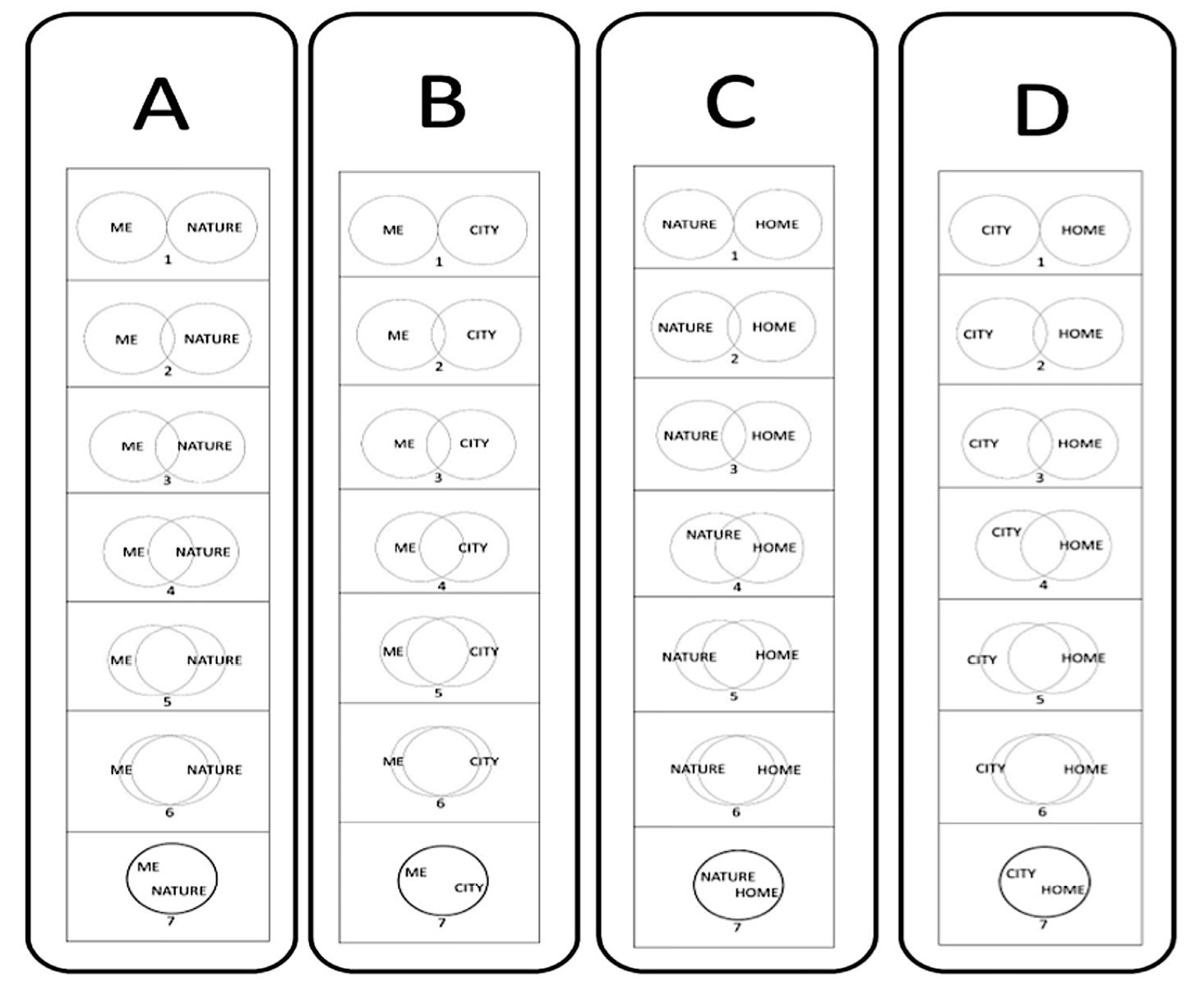

The questionnaire additionally explored respondents’ feelings of connectedness to nature, town, and home, using their responses to the illustrations in Figure 8.2. The outcome of reported feelings of their connectedness to Nature, Town, and Home was as follows:

- ‘Me and Nature’ (A) A significant majority of the respondents (65.81%) believe that they are intricately connected with nature, resulting in a sense of overlap between themselves and the natural world. In contrast, a relatively small proportion (9.4%) expressed that they do not perceive themselves and nature as a unified entity.

- ‘Me and City’ (B) The perception of whether respondents feel they are an integral part of their town exhibited a mixture of responses. This variation may be attributed to respondents not fully grasping the question’s intent or struggling to establish a relatable connection to the query, but also their proximity and association with existing cities.

- ‘Nature and Home’ (C) A noteworthy observation here is that more than half of the respondents (58.06%) articulated that their home and nature coalesce seamlessly, yielding a sense of coexistence.

- ‘City and Home’ (D) In contrast to the previous observation, a trend emerged concerning respondents’ perception of their town and home as a unified entity. Many respondents appeared uncertain about interpreting this question, resulting in various responses contributing to the mixed perceptions surrounding the interconnectedness of their town and home.

Fig. 8.2 Questionnaire illustrations used to clarify respondents’ sense of connectedness to nature, town, and home. Source: authors’ data, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

In summary, these insights collectively underscore the interplay of individuals’ perceptions regarding their connection to nature, their town, and their home. While a strong alignment with nature is prevalent, varying interpretations of the relationships between their town and home indicate the multifaceted nature of these sentiments.

Respondents were also asked about whether they carried feelings towards other people, using three categories: Not True, Sometimes True, and Often True. The results show a response of 63% which exhibit an inclination towards empathy, with the predominant response falling under the ‘sometimes true’. This commonality in responses could be attributed to insights shared by respondents, such as ‘when a friend is angry, I usually know why’. These comments underscore a nuanced understanding of emotional dynamics and interpersonal cues, contributing to the respondents’ empathetic attitudes.

In terms of analysing responses by the respondents regarding their sense of empathy with nature and animals, different patterns were observed. Respondents exhibited a substantial degree of empathy towards nature and animals in that they indicated that they strongly agree (83.2%) they have a strong connection and empathy towards nature and animals. In essence, these data underscore the prevalence of empathetic attitudes towards nature and animals amongst the youth in our survey, showcasing a consistent and robust inclination towards valuing and understanding the well-being of the natural world and its inhabitants.

8.4 Discussion and review of findings

It is evident from our survey findings that most respondents expressed their connectedness to wildlife and have also further portrayed an exciting willingness to contribute towards conservation. Perceptions and willingness to contribute to wildlife conservation have been identified as critical components in preparing for the future of wildlife protection. It also depicts how people learn in their habitual environment, transfer knowledge between different generations, and use citizen science.13 One key finding was that female respondents showed more conservation-oriented behaviours and empathy toward the four species than their male counterparts. The Wildlife Club movement in Africa has strongly emphasised the need to address conservation attitudes and youth behaviours;14 as reflected in the methodology and findings of this chapter which illustrates the mostly positive attitudes amongst the young people included in our research. In addition, such emphasis is meant to analyse and predict the future of conservation and act as a means of creating awareness in the youth, thus safeguarding the prospect of the different wildlife species.15 The chapter further presented findings on empathy toward the four species, which came out both strongly and positively, being complementary to calls for future conservation effort. In particular, it is important to focus on conservation areas beyond zoos that have often been the focus on studies on empathy towards wildlife,16 as has been attempted here in our study of connectedness with nature and selected animal species in the communal land areas of Kunene Region.

Another considerable view on empathy and connectedness of human nature and wildlife is that the narratives used to develop a generalised positive stance differ for every species (as shown in Section 8.2). Specifically, rhinos are sometimes viewed as ugly, giant animals; however, based on the classification of critically endangered species and poaching incidents,17 respondents have shown empathy and the need to conserve them whilst protecting them from extinction. Lions were also not classified as distinctly favoured species as they portray danger to humans. However, respondents also recognise the lion as brave in its hunting skills, roaring character, and in particular the need to preserve it for future generations as well as the species’ ability to create income through tourism.18 On the contrary, goats and oryx were perceived in a more favourable way: empathy and connectedness was derived from how goats and oryx are susceptible to predators, and also from how goats are part of household livelihoods;19 whereas, empathy and connectedness toward the oryx has been linked with its role in national symbols.20

To conclude, then, the issue of relationship and connectedness to animal species has proven to be relatable with cultural and ethical values embodied in practice and in the sentiments shared by respondents. The sample selection of animal species covered a wide range of relationships and connectedness amongst respondents, linked with contributions to livelihoods and with concern for conserving rhinos coming out as particularly strong. Overall, the comprehensive findings from this study shed light on several compelling insights. One observation is that goats hold heightened popularity and garner increased preservation efforts among local community members in the surveyed regions. This stems from goats playing a pivotal role in supporting household livelihoods, effectively cementing their significance within the community fabric.

The survey both generated and imparted knowledge, clarifying how youth participation in conservation relates to wildlife and evidencing young peoples’ sense of connection to various species, except perhaps in the case of lions. The lower level of connectedness with lions can be attributed to instances of human-wildlife conflict (HWC), which have generated caution and reduced the perceived connection to these creatures: although it should be acknowledged that when people lived throughout wider areas of north-west Namibia in the past, more robust knowledge as well as practices for living with and appreciating lions existed21 (see Chapter 15). A noteworthy finding is the pronounced empathy demonstrated towards rhinos. This heightened empathy can be attributed to the endangered status of rhinos, with participants recognising the urgency and significance of preserving these majestic animals. In summary the findings highlight the complex interplay between popularity, preservation efforts, empathy, and ecological and social factors in shaping attitudes towards different species.

Bibliography

Atkins, J., Maroun, W., Atkins, B.C. and Barone, E. 2018. From the Big Five to the Big Four? Exploring extinction accounting for the rhinoceros. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal 31(2): 674–702, https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-12-2015-2320

Atsiatorme, L., Owusu, A. and Kyerematen, R. 2011. Wildlife Clubs of Africa Manual: Guidelines for the Establishment, Development and Management of Wildlife Clubs in Africa. Nairobi: BirdLife International Africa Partnership Secretariat.

Ballard, H.L., Dixon, C.G.H. and Harris, E.M. 2017. Youth-focused citizen science: Examining the role of environmental science learning and agency for conservation. Biological Conservation 208: 65–75, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.024

Beytell, P.C. 2010. Reciprocal Impacts Of Black Rhino And Community-Based Ecotourism in North-west Namibia. Unpublished MA Dissertation, Stellenbosch University.

Chimes, L.C., Beytell, P., Muntifering, J.R., Kötting, B. and Neville, V. 2022. Effects of dehorning on population productivity in four Namibia sub-populations of black rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis bicornis). European Journal of Wildlife Research 68(5): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10344-022-01607-5

Emslie, R., Milliken, T., Talukdar, B., Burgess G., Adcock, K., Balfour, D. and Knight. M.H. 2019. African and Asian Rhinoceroses – Status, Conservation and Trade. A report from the IUCN Species Survival Commission (IUCN/SSC) African and Asian Rhino Specialist Groups and TRAFFIC to the CITES Secretariat pursuant to Resolution Conf. 9.14 (Rev. CoP17). CoP18 Doc. 83.1 Annex 2. Geneva: CITES Secretariat, http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/pdf_files/156/1560170144.pdf

GRN 2018. National Symbols of the Republic of Namibia Act No. 17 of 2018. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia.

Heydinger, J.M., Packer, C. and Tsaneb, J. 2019. Desert-adapted lions on communal land: Surveying the costs incurred by, and perspectives of, communal-area livestock owners in northwest Namibia. Biological Conservation 236: 496-504, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.06.003

Khumalo, K.E. and Yung, L.A. 2015. Women, human-wildlife conflict, and CBNRM: Hidden impacts and vulnerabilities in Kwandu Conservancy, Namibia. Conservation and Society 13(3): 232–43, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26393202

McDuff, M. and Jacobson, S. 2000. Impacts and future directions of youth conservation organizations: Wildlife clubs in Africa. Wildlife Society Bulletin, 28(2): 414–25.

MET 2009. Tourism Scoping Report: Kunene Peoples Park. Windhoek: Ministry of Environment and Tourism.

Muntifering, J.R., Clark, S., Linklater, W.L. et al. 2020. Lessons from a conservation and tourism cooperative: The Namibian black rhinoceros case. Annals of Tourism Research 82: 102918, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102918

Muntifering, J.R., Linklater, W.L., Clark, S.G., !Uri-ǂKhob, S., Kasaona, J.K., |Uiseb, K., Du Preez, P., Kasaona, K., Beytell, P., Ketji, J., Hambo, B., Brown, M.A., Thouless, C., Jacobs, S. and Knight, A.T. 2017. Harnessing values to save the rhinoceros: Insights from Namibia. Oryx 51(1): 98–105, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605315000769

Paul, E.S. 2000. Empathy with animals and with humans: Are they linked? Anthrozoos 13(4): 194–202, https://doi.org/10.2752/089279300786999699

Reuters 2024. Namibia investigates surge in rhino poaching in Etosha park. Reuters 2.4.2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/namibia-investigates-surge-rhino-poaching-etosha-park-2024-04-02/

Save the Rhino Trust 2022 Eliciting Empathy and Connection with Nature to Protect Rhinos in Namibia. A progress report submitted to the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Maryland, USA.

Schneider, V. 2023. Namibian community protects its rhinos from poaching but could lose them to mining. Mongabay 13.3.2023, https://news.mongabay.com/2023/03/namibian-community-protects-its-rhinos-from-poaching-but-could-lose-them-to-mining/

Sullivan, S. 2016. Three of Namibia’s most famous lion family have been poisoned––why? The Conversation

23.8.2016, https://theconversation.com/three-of-namibias-most-famous-lion-family-have-been-poisoned-why-64322

Sullivan, S., !Uriǂkhob, S., Kötting, B., Muntifering, J. and Brett, R. 2021. Historicising black rhino in Namibia: Colonial-era hunting, conservation custodianship, and plural values. Future Pasts Working Paper Series 13 https://www.futurepasts.net/fpwp13-sullivan-urikhob-kotting-muntifering-brett-2021

Togarepi, C., Thomas, B. and Mika, N.H. 2018. Why goat farming in northern communal areas of Namibia is not commercialised: The case of Ogongo Constituency. Journal of Sustainable Development 11(6): 236, https://doi.org/10.5539/jsd.v11n6p236

Young, A., Khalil, K.A. and Wharton, J. 2018. Empathy for animals: A review of the existing literature. Curator 61(2): 327–43, https://doi.org/10.1111/cura.12257

1 Muntifering et al. (2020)

2 Khumalo & Yung (2015)

3 Paul (2000)

4 Save the Rhino Trust (2022)

5 Muntifering et al. (2017); Sullivan et al. (2021)

6 Atkins et al. (2018)

7 Reuters (2024)

8 Schneider (2023)

9 Beytell (2010)

10 Chimes et al. (2022)

11 Sullivan (2016), Heydinger et al. (2019)

12 MET (2009)

13 Ballard et al. (2017)

14 For example, Atsiatorme et al. (2011)

15 Mcduff & Jacobson (2006)

16 Young et al. (2018)

17 Emslie et al. (2019)

18 Heydinger et al. (2019)

19 Togarepi et al. (2018)

20 GRN (2018)

21 Sullivan (2016)