12. Cultural heritage and histories of the Northern Namib / Skeleton Coast National Park

©2024 Sian Sullivan & Welhemina Suro Ganuses, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0402.12

Abstract

We outline Indigenous cultural heritage and histories associated with the Northern Namib Desert, designated since 1971 as the Skeleton Coast National Park. We draw on two main sources of information: 1) historical documents stretching back to the late 1800s; and 2) oral history research with now elderly people who have direct and familial memories of using and living in areas now within the Park boundary. This material affirms that localities and resources now included within the Park were used by local people in historical times, their access linked with the availability of valued foods, especially !nara melons (Acanthosicyos horridus) and marine foods such as mussels. Memories about these localities, resources and heritage concerns, including graves of family members, remain lively for some individuals and their families today. We argue for the importance of understanding the Northern Namib as a remembered cultural landscape, as well as an area of high conservation value. In doing so, protecting and perhaps restoring access to sites with significant contemporary cultural heritage value, would be appropriate. Such sites include locations of culturally important foods such as !nara, graves of known ancestors, and named and remembered former dwelling places. We hope the material shared here will contribute to a diversified recognition of values for the Skeleton Coast National Park, to shape ecological and heritage conservation practice and visitor experiences into the future.

It can be concluded that the coast in the west of the Kaokoveld was not a no-man’s-land, but rather that there were south-north and north-south relations and migrations of a sparse coastal population and that memories of it have been preserved right down to the recent past.1

12.1 Introduction2

This chapter reviews historical and cultural information for the Northern Namib Desert. We summarise observations from historical texts regarding the area (Section 12.2); followed by oral history research with Khoekhoegowab-speaking people now living in the Sesfontein area, who remember accessing and using resources and sites within and close to the Skeleton Coast National Park (SCNP) boundary in the past (Section 12.3). Suggestions are made for foregrounding an understanding of the Northern Namib as a remembered cultural landscape as well as an area of high conservation value, and for protecting and perhaps restoring some access to sites that may be considered of significant cultural heritage value (also see Chapters 13, 14 and 15). Such sites include locations of culturally important foods, graves of known ancestors, and named and remembered former dwelling places.

The chapter originated as a report3 written by invitation of the current Deputy Director Wildlife Monitoring and Research of Namibia’s Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT), to support development of the new Management Plan for Namibia’s Skeleton Coast National Park, 2021/2022–2030/2031.4 This Management Plan—hereafter the Plan—foregrounds the significance of archaeological and cultural sites in the Northern Namib alongside biodiversity protection, sustainable use, stakeholder participation and a landscape approach to conservation (see Chapter 3).

At the same time, the Plan includes rather little information in terms of historical literatures regarding the Northern Namib, or recall of its prior cultural and livelihood significance for peoples who once accessed and lived in this area.

For example, Chapter 7 of the Plan (Section 7.3) on ‘Archaeological sites’ states that virtually no sites from the Holocene (ca. 11,650 years ago to the present) have been recorded for the Skeleton Coast National Park (SCNP). It is assumed that people ‘may not have inhabited the coastal part of the Northern Namib during the Holocene’; although

their presence is recorded on the eastern margins of the Northern Namib from where they probably conducted temporary forays into the coast as also clear from the huge number of white mussel shells in shell middens (dated approx. 1,000 to 2,700 years old) which may have been the most important marine species used for food.5

The historical and oral history information in Sections 12.2 and 12.3 of this chapter indicates instead that within living memory people accessed and lived in areas that are now part of the Park. Some elderly people now concentrated in the Sesfontein area of the Hoanib River valley retain vivid memories of named places and livelihood practices in the Northern Namib—including harvesting !nara melons (Acanthosicyos horridus) and marine resources such as mussels. Their narratives also affirm cross-generational depth of habitation of this area.

12.1.1 Policy context

Acknowledgement in contemporary times of peoples’ past associations with sites now within the SCNP and on its borders is clearly relevant for those sharing these histories, but is additionally appropriate for a series of policy aims. The material shared here is intended to support the 5th Strategic Management Objective listed in the Plan, namely: ‘[t]o protect and maintain cultural and historic, archaeological, and paleontological assets’.6 It is thus also aligned with Namibia’s National Heritage Act of 2004, as well as recognising the ethos of Article 19 of the Namibian Constitution that:

[e]very person shall be entitled to enjoy, practise, profess, maintain and promote any culture, language, tradition or religion […] subject to the condition that the rights protected by this Article do not impinge upon the rights of others or the national interest.7

For the southern parts of the Northern Namib, the lead organisation neighbouring the SCNP that represents local cultural concerns is the recently formalised Nami-Daman Traditional Authority (TA) (also see Chapter 13).8 This TA considers its jurisdiction to stretch east of the Park boundary from the Hoarusib southwards to the vet fence.9 Although not mentioned in the SCNP Management Plan, this TA is a key stakeholder regarding SCNP management, particularly regarding heritage, historical and cultural concerns relating to the Northern Namib, acting alongside the communal-area conservancies neighbouring the park.

Recognising diverse past cultural, resource management and livelihood associations with this landscape for which fragmented memories remain in the present is also an important means of supporting the “biocultural heritage” of Indigenous peoples: i.e. heritage understood as entangled with specific environmental contexts, whose resilient diversity has the potential to support biological diversity.10 Recognition of, and support for, emplaced cultural environmental knowledge and appreciation—or biocultural heritage—can be viewed as contributing to the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 15 on terrestrial ecosystem health, as well as to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), as acknowledged in Chapter 5 of the SCNP Management Plan. Recognising the presence of Indigenous knowledge custodians regarding the former use of the Northern Namib—as encouraged in Chapter 6 of the Plan;11 as well as enhancing knowledge regarding cultural sites in and close to the Park—as promoted in Chapter 7;12 may widen the appeal and value of the Park whilst respecting prior use and knowledge (as documented in Section 12.3 of this chapter).

12.2.2 Sources

The material shared below outlines cultural histories and remembered resource-use practices linked with the Northern Namib, now protected as the SCNP. It draws on three main threads of research:

- Iterative review of historical literatures regarding !nara harvesting and harvesting peoples connected with the Namibian coastal areas, collated in the following timelines:

- Archaeological and historical records that mention !nara use in Namibia, linked at https://www.futurepasts.net/nara-in-archaeology-and-history, plus map of references to !nara use at https://www.futurepasts.net/archaeological-historical-nara-refs;

- Historical references to habitation of the !Khuiseb delta, linked at https://www.futurepasts.net/khuiseb-historical-habitation.

- Oral history research and interviews over the last 25 years with primarily Khoekhoegowab-speaking individuals now living in the Sesfontein area.

- On-site oral histories and cultural landscapes mapping journeys with elderly individuals who remember living in, moving through, and harvesting from areas now located inside the SCNP. Access to localities in the SCNP was enabled as part of a project led by Dr Gillian Maggs-Kölling, Director of Gobabeb Namib Research Institute, on ‘The significance of the Namib Desert endemic !nara (Acanthosicyos horridus) as a keystone species in ecology, phenology, culture and horticultural potential’. The following statement in Chapter 5 of the Plan derives from this on-site oral histories research:

Acanthosicyos horridus (!nara) colonies associated with all the ephemeral rivers that have supported human occupation in the Namib Desert for thousands of years […] were used by Damara and Nama people in addition to the well-known association with the Topnaar people.13

All interview material shared in Section 12.3 is from field research we have carried out together. Interview transcriptions in Khoekhoegowab and translations from Khoekhoegowab to English were led by Ganuses, and all interpretations of this material worked on by us both, as well as with our local companions in this research. All journeys reported in Section 12.3 were carried out with the guidance of Mr Filemon |Nuab, a “Rhino Ranger” based in Sesfontein whose knowledge of the north-west Namibian landscape is renowned.

12.2 Historicising the Northern Namib

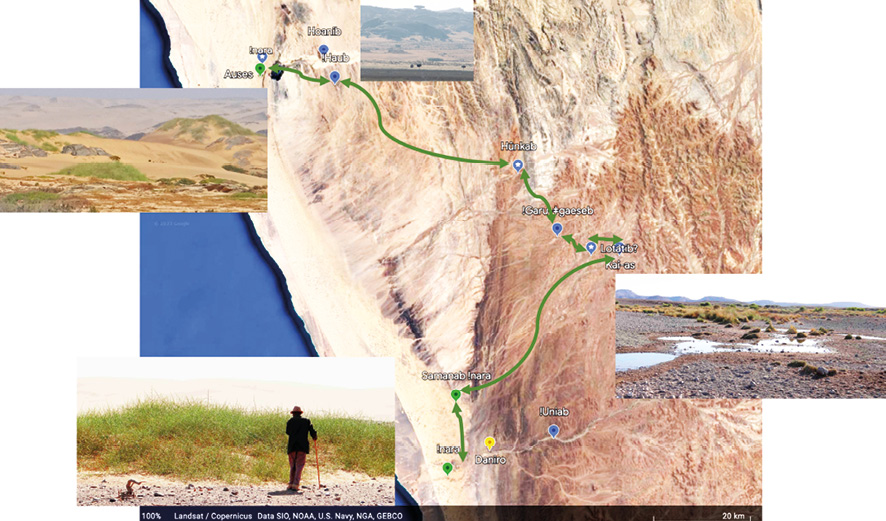

Fig. 12.1 Map of places (red), rivers (blue) and topographical features (yellow) mentioned in this chapter. ǂGîeb’s grave (see Section 12.2.3 and Figures 12.11 and 12.19) is represented by the purple marker. Prepared by Sian Sullivan, including data from Landsat / CopernicusData SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, Imagery starting from 10.4.2013. © Etosha-Kunene Histories, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Mapped historical records of observations and encounters with autochthonous Namibians in the Northern Namib provide background and context to the material documented through peoples’ recall in Section 12.3. Whilst these historical accounts need to be read with a critical eye for accuracy, as well as for the prejudices and racism with which they are often imbued, in the absence of other sources they can be informative regarding the past presence of peoples in localities from which they are now absent: also see Chapters 1, 2, 13, 14 and 15. Several actors are particularly visible in this respect, in part because they left reports documenting encounters and impressions from these journeys.14 Although often focused on the commercial potential of the coastal area—for example, several key journeys were carried out in the course of prospecting for the Kaoko Land and Mining Company (Kaoko Land und Minengesellschaft, KLMG) established during the German colonial period of Namibia’s history—they also report encounters with people in the landscapes through which they travelled. Read together, these accounts clarify that the Northern Namib was lived in and utilised by diverse peoples, up to the recent past. Historical records for the Northern Namib are outlined below for the following periods: pre-German colony (Section 12.2.1); German colonial times (1884–1915) (Section 12.2.2); and post-World War 1 South African rule (Section 12.2.3). For ease of reference, places, rivers and springs named in this chapter are mapped in Figure 12.1.

12.2.1 Pre-German colony

Overland journeys to the Northern Namib were difficult for the earliest European and American travellers, and recorded observations from the coast are fragmented and tricky to interpret for accuracy. Nonetheless, some pre-German colonial-era observations/projections are relevant in terms of drawing into focus the Northern Namib as an inhabited and utilised landscape.

One narrative, by American sealer Captain Morrell travelling northwards along the coast in 1828–1829, states that some ‘two leagues’15 north-east of ‘Ogden’s Harbour’16 (ǁHuab River mouth—see Figure 12.1) his expedition encountered ‘a small village, inhabited by about two hundred natives’ which he refers to as ‘of the Cimbebas tribe’.17 ‘Cimbebas’ here is understood to invoke the name given for an inland ‘region between Cape Negro and Tropic of Capricorn’ on a 1591 Italian map of Africa (by Filippo Pigafetta), rather than to ‘Tjimba’ (a contemporary term for cattle-less ovaHerero).18 Indeed, Morrell remarks of the people he encountered that they differ ‘but very little from the proper Hottentots19 [i.e. Khoekhoegowab speaking Nama]’, writing enthusiastically of the locality that,

[t]here are […] many fine springs of water, of an excellent quality, in the valley where this village is situated; from which it may be inferred that this would be a fine place for a rendezvous to establish a trade with the interior of the country.20

In the vicinity of Cape Frio further north—if we can trust Morrell’s account—he also writes of an inhabitants’ village ‘about ten miles from the coast’,21 characterised by reed mat huts constructed of ‘closely woven mats of coarse grass’, or ‘of the fibres of some plant’:

[t]he two sides generally correspond with each other, as do also the two ends, with the exception that there is a door or opening in one end, just large enough for the occupants to creep in and out. Each hut is covered with an arched or sloping roof, supported by upright posts fixed in the ground, and thatched with matting. The materials are all so light that they can be removed at a very short notice, and without much trouble. I have seen them taken down and put together again in thirty-five minutes. The value of one of these huts is that of a sheep.22

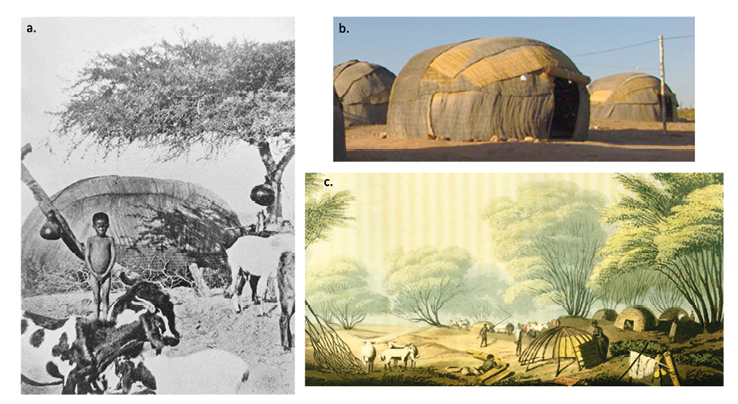

This description matches the well-known reed-mat huts historically specific to Nama/Khoe pastoralists (see Figure 12.2). Such structures were lived in within recent memory in localities connected with present-day SCNP (such as Sesfontein, close to the Hoanib River), where they were no doubt linked with the presence in this area of !Gomen Topnaar and Swartbooi pastoralists (see Chapter 1). The late Philippine |Hairo ǁNowaxas, for example, who described herself as ‘ǁKhao-a Dama’ (see Section 12.3 and Chapter 13), recalled in 1999 that,

[t]hese dung houses we didn’t know about before, in the old time. Now Julia [Ganuses, deceased] is storing the |haru reeds [Cyperus marginatus] in her house to make a reed house [|haru oms]. We make the reed houses like this: we cut the reeds and put some in dung [to blacken them] and some in water and then we weave in the black ones on one side and the white ones on the other side; we built reed houses and we didn’t know about these dung houses. When I was small I lived in the |haru oms.23

Fig. 12.2 Examples of Nama reed mat huts (known in Sesfontein as |haru oms): a) ‘Topnaar hut under Giraffe acacia’, by L. Schultz. Source: scan from Schapera 1965[1930]: Plate XV; b) contemporary Nama hut in the Richtersveld showing anchor stones at the base. Source: https://www.exploring-africa.com/en/namibia/nama-people/nama-huts-and-villages; c) ‘A Hottentot [Khoe] Kraal, on the Banks of the Gariep [i.e. Orange River]’, from Burchell (1822, vol. 1: 325). Source: https://library.princeton.edu/visual_materials/maps/websites/africa/burchell/burchell5.jpg. All out of copyright or public domain images, adapted by Sian Sullivan, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

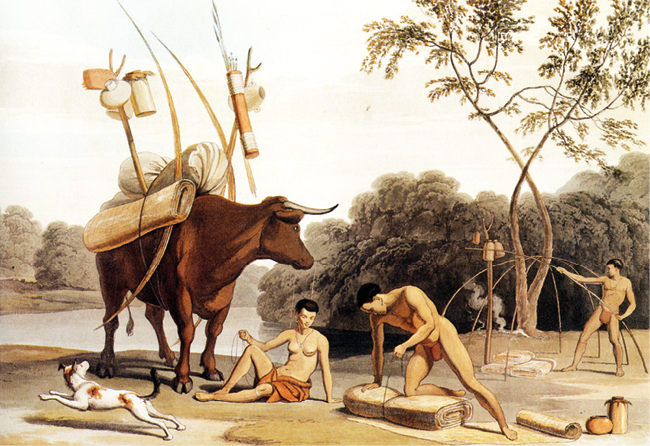

Reed mat huts leave only subtle traces by way of material remains, but may be visible in the archaeological record as a circle of anchor stones used to help fix the frame poles and mats in place:24 see Figure 12.2b. It is tempting to link Morrell’s account above with limited archaeological data for stone hut circles in the Northern Namib confirming the presence of anchor stones for reed mat huts associated with Khoe pastoralists, that would have been transported by oxen25—as depicted in the well-known (and somewhat romanticised) image in Figure 12.3.26 Indeed, wide diameter (around 4 m) circles of hut anchor stones with a central fireplace and room divider have been found near the !Uniab river mouth—within the SCNP and in between Morrell’s observations above—dated to ca. 1,000-1,300 BP and consistent with Nama/Khoe hut construction.27 An eye-witness account from 1896 reported in Section 12.3 also observes ‘deserted, circular reed huts at the Uniab River mouth’.28

Speich writes that,

[t]he production of the [hut] framework is complex and the procurement of the suitable material for the hut frame was probably not possible everywhere. Therefore the frequent occurrence of this type of hut in the arid Uniab Delta […] raises some questions. In any case, however, the frame can be distinguished by its construction.29

Fig. 12.3 ‘Korah-Khoikhoi dismantling their huts, preparing to move to new pastures’, by Samuel Daniell 1805. Source: public domain image at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Samuel_Daniell_-_Kora-Khokhoi_preparing_to_move_-_1805.jpg, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

It should be noted, however, that the poles and mats of which this hut type were built were both durable and portable using pack oxen that were presumably herded in connection with inland pastures.30 These materials were no doubt in part derived from elsewhere in the landscape, being carried by those inhabiting this !Uniab site which was perhaps visited in part so as to access !nara and shellfish. In addition, |haru sedges (Cyperus marginatus) from which the mats were made are found at sites of moisture throughout the Northern Namib and adjacent areas.31 They are in fact common to the coastal spring known into contemporary times as |Garis32 that is close to the !Uniab mouth (Figure 12.4).

Fig. 12.4 Sedges (|haru, Cyperus marginatus) known to be used in the making of Nama reed mat huts, at the water source known in recent times as |Garis at the !Uniab river mouth, Skeleton Coast National Park. Photo: © Sian Sullivan, 24.11.2015, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Archaeologist John Kinahan interprets the presence of apparently Khoe reed mat huts in the Northern Namib as consistent with an hypothesised ‘northward pulse of pastoral expansion’ from the Orange River area; subsequent to westward movements of Khoe pastoralists from the northern Kalahari along the Orange (!Garib) that then branched north and south into the south-western landscapes of present-day Namibia and South Africa.33 The remains of Khoe reed mat huts in the Northern Namib are additionally consistent with possible southwards migrations of Khoe pastoralists from further north.34 These complexities and uncertainties notwithstanding, the archaeological traces of pastoralist reed mat hut structures appear to evidence past Khoe/Nama presence in the Northern Namib, perhaps associated with wetter climatic conditions from around 1,000-1,350 AD:

[d]uring the Middle Ages a humid phase seems to have transformed parts of the Namib desert into a savanna-like ecosystem. Under the hyperarid conditions of the Little Ice Age [ca. 1,500-1,850 AD] the desert margin shifted to the east again. Apparently, the Namib-desert has been no stable arid region during the younger Holocene. Substantial landscape change happened especially in the area of the desert margins.35

Different types of stone hut circles, as well as contemporaneous shell middens indicating consumption of shellfish such as mussels, have also been documented archaeologically at multiple localities in the Northern Namib. In the vicinity of the !Uniab mouth, the remains of huts formed by ‘coarse boulders’ assumed to serve ‘for the fixation of wooden poles and rods […] and covered with leaves, branches, grass, or skins for protection’, are attributed to ‘former Bushmen’.36 Further north, the remains of hut circle settlements have also been documented close to the coast north of the Munutum river mouth, in between the Nadas and Sechomib rivers, and at the Khumib river mouth.37 Note that these Khoekhoegowab names for northern Namib ephemeral rivers have been recorded since the area was first visited and mapped by incoming Europeans, their stability and longevity again indicating the past presence of Khoekhoegowab-speaking peoples in the Northern Namib (as discussed in Chapter 1).

A site between the Nadas and Sechomib rivers, for example, includes ‘a total of 35 stone circle features’ and some stone circles including whale bones, as well as stone artefacts, potsherds of ‘Khoi’ pottery, ostrich eggshell beads, bones and hunting blinds found at or near the sites.38 Three dates obtained for the sites were ‘within the period AD 1680 to 1940’, with coastal sites considered strongly connected to the hinterland.39 Soot on potsherds from the site north of the Munutum ‘yielded an unexpected age’ of 840 ± 50 AD.40 Further south, but within or on the eastern edge of the SCNP, John Kinahan41 records ‘high local densities of pastoral settlement’ dated to within the last 1,000 years, whose ‘distinctive archaeological features’—namely ‘stone hut circles with associated livestock enclosures, as well as pottery [used for storage of !nara and grass seed plant foods] and stone artefact assemblages’—comprise ‘the archaeological signature of the ǂNūkhoen’.

Crossing back into the historical (as opposed to archaeological) record, in the 1850s the coastal area west of the ‘Kaoko mountains’ in the north-west (‘the barren Kaoko’42) was recorded by British explorer Francis Galton as inhabited by peoples known as ‘Nareneen’, an appellation presumably connected with their use of !nara in this northern part of the Namib (see Chapter 1 and Figure 1.3). Galton writes specifically that,

[t]he Nareneen lived by the sea, and the Ounip (called by the Dutch Toppners [i.e. ǂAonin]) about the parts of which we are now speaking [presumably Walvis Bay area], and south of these were the Keikouka [Kaiǁkhauan/Rooi Nasie/Red Nation], now represented by the red people, by Swartboy [ǁKhau|gôan], the Kubabees [ǁHabowen/Veldschoendragers], and Blondel Swartz [!Kamiǂnûn/!Gamiǂnûn]. […] The Toppners [ǂAonin], however, not being at that time accustomed to the mountain-passes with which the Ghou Damup [Damara/ǂNūkhoen] were familiar, were, as I said, greatly cut off [towards the coast]. And it is curious, that within very late times (about eight years ago [ca. 1840s]), exactly the same thing occurred to the Nareneen living west of the Kaoko. […] The more northerly Toppners [ǂAonin] were thus quite cut off from all communication with those about Walfisch Bay […]43

As indicated in this quote, the mid-1800s were turbulent times (also see Chapter 1). Oral history recorded in Rhenish Missionary Society (RMS) Chronicles of the 1800s describes the coastal landscape connecting the Northern Namib with Walvis Bay as one of mobilities between ‘Topnaar’44 in the north and those of the Walvis Bay area. ‘Topnaar’ migrating south from Kaokoveld in these years are described as

spread[ing] further south [via the Swakop River mouth] […] allegedly led by their captain Khaxab to one place ǂKisa-ǁguwus commonly known as Kuwis or Sandfontein, located about three miles from the coast and settled south of what is now Walvis Bay.45

Late 19th century archives of the Rhenish Mission, drawing on missionary Baumann (based at Rooibank/|Awa-!haos from 1878–1883), assert that ‘[a]ccording to the ancients, the Topnaars came from the north towards the end of the eighteenth century’, and that ‘[a]t the beginning of the 19th century the Topnaar are said to have reached the mouth of the Swakop (tsoa-xou-b)’, their migration perhaps ‘related to the advance of the Herero into the Kaokoveld’.46

In 1913 at apparently Sandfontein (ǂKhîsa-ǁgubus), south of Walvis Bay, South African anthropologist Winifred Hoernlé,47 relates a conversation with Khaxas48— ‘the daughter of one of the last [Topnaar] chiefs’—and ‘some of the headmen of the last recognized chief of the tribe, Piet ǁEibib [ǁHaibeb]’. In this conversation she learns that according to ‘these old people, the tribe originally lived far to the north in the region to which one branch has again retired’ (i.e. to become the Sesfontein !Gomen Topnaar, !Gomes being the name for Walvis Bay); and that ‘[w]hen they first came to Walvis Bay another Nama people, the “|Namixan”, were in control’.49

It seems that historically recorded Northern Namib mobilities from the 1860s onwards should be understood as connected with the earlier mobilities reported by Galton, Hoernlé and Köhler: in which a section of ‘the Topnaar’ retreated to Kaokoveld ‘after the defeat of the Hottentots by the Herero in the sixties of the last century’, leaving ‘the other section […] in the dunes around Walvis Bay and in the bed of the Kuiseb river at various places’.50 These mobilities became amplified after 1864 when Indigenous Swartbooi Nama (ǁKhau|gôan), then living in Rehoboth in the south, were attacked by Oorlam Nama leader Jonker Afrikaner’s son (Jan Jonker Afrikaner), in retaliation for Swartbooi alliance with the ovaHerero leader Kamaherero against the Oorlam Afrikaners51 (see Chapter 1). The Rehoboth Swartbooi retreated west along the !Khuiseb River, from where they settled at a short-lived RMS mission station called Salem on the Swakop River,52 before moving towards Fransfontein and Sesfontein where they settled in the late 1800s, via !Am-eib in the Erongo mountains. The RMS chronicle of Otjimbingue thus documents that,

Topnaar living in the Kuiseb valley joined forces with the Zwartbooi, headed northward under the leadership of missionary Bohme, and settled in !Am-eib at the Erongo mountains. When the water in !Am-eib became scarce, the Zwartbooi and the Topnaar moved northwards to reach Okombahe, Otjitambi or Franzfontein. From there, many Topnaar moved to Zesfontein (aka Sesfontein), where at that time lived Bushman and Bergdama, who were being influenced by the Herero. The Topnaar were later followed by a smaller group of Zwartbooi who also settled in Zesfontein.53

Through the middle of the 1800s, European travellers found it hard to access present-day Kunene Region in the north-west and few documented encounters with the Northern Namib exist. In 1858, for example, the Anglo-Swedish hunter, naturalist and trader Charles John Andersson travelled through Kaokoveld ‘in a vain attempt to reach the Kunene River’,54 entering a region of arid mountains but being halted by the ruggedness of the area.55 In this pre-German colonial moment commercial concerns affecting the Northern Namib and connected landscapes were linked with the export of ivory from the north through Walvis Bay, in part via a coastal route from north to south through the western desert beyond rival European access.56 In 1877 Rhenish missionaries Böhm and Bernsmann travelled northwards to the east of the Northern Namib. Their route took them from Otjimbingwe on the Swakop River as far as the Hoanib River in the north-west, circling what are named as the Etendeka mountains (also ǂNauraheb, see Chapters 9 and 13) in the uplands of the !Uniab via !Am-eib, Okombahe (!Aǂgommes), Sorris-Sorris on the Ugab river, Urunendis (Uruhûnes), Kai-as, Hûnkab, ‘Ub’ (|Ūb) on the Hoanib (west of Sesfontein), and ‘Zesfontein’, for which they also record an otjiHerero name (Ohamuheke).57

1879 saw two notable crossings of the Kaokoveld that reached the Northern Namib coast, for which fragmented documentation exists. Trekboers returning from the Okavango in this year turned westwards from ‘Ovampoland’ ‘to the so-called Kaokoveld south of the Kunene River and continued on right down to the sea’.58 In this same year, a philanthropic collection organised for the Trekboers by settlers of the Cape led to a relief mission being sent north from ‘Walfish Bay’ bringing ‘clothes, medicine, provisions and ammunition’,59 in the course of which the Trekboer Gert Alberts led ‘a small mounted party down the valley of the Hoarusib River to the sea, in an attempt to collect [the] supplies’ arriving on the coast:60 see Chapter 1. Although containing little information regarding local encounters, these journeys demonstrate how Kaokoveld to the coast was starting to be traversed by colonial-era travellers.

12.2.2 German colonial times, 1884 to 1915

Commercial interests in the north-west intensified as the 1880s ushered in German colonial rule and a consolidated effort to survey and control the colony’s natural and human resources for economic gain. As outlined more fully in Chapter 1 an outcome was the acquisition of mining rights in the north-west, and subsequently a series of expeditions in this area led by surveyor Georg Hartmann to ascertain commercial opportunities, including along the coast of the Northern Namib. Hartmann embarked on his first survey of the ‘Kaoko-Feld’ for the KLMG in 1894, whilst working for the (British-invested) South West Africa Company61 in Otavi District (Gebiet) south of Etosha Pan. He writes that:

[t]he main task of this expedition was the mining and agricultural investigation of the middle Kaoko area to beyond Seßfontein. On top of that it should try to travel along the Hoanib River to the coast and to investigate the landing conditions there. This expedition should therefore be the first attempt to explore the unknown coast at this point and I confess that I accepted with great enthusiasm to execute this expedition.62

Referencing Morrell’s earlier reports, Hartmann additionally observes that,

the whole unknown coast from Swakop-Mund to the northern border is like a blank white sheet of paper, and yet we see a lot of names and numbers there, proof that up to a certain extent the exploration of the coast has been attempted.63

With Nama guides who were clearly familiar with the terrain, Hartmann travelled west of Sesfontein along the Hoanib towards the coast. His impressions are worth quoting in full: for those familiar with the terrain, they are strongly evocative of the Northern Namib and its neighbouring landscapes:

[t]o the west of Seßontein, there seemed to have been little or no rain. The consequence was that we had to march to the coast under great thirst and terrible heat. In addition the stony ground over all was bad for travelling with ox carts. After three days’ west of Seßontein, our ox carts under the engineer Rogers turned south and drove across the mountains in a southerly direction to the west side of the central mountain range [at |Ūb?]. I myself walked along the Hoanib with a small cart and some riding horses to reach the coast. Especially on this leg we suffered from thirst again. The Hoanib itself retained its lush bush vegetation. Gradually towards the coast it became lower and reminded us of the influence of the coastal climate. […] In the Hoanib we suddenly couldn’t go any further, because of a mighty sand dune wall of 50-100 m high, which seemed to extend to the N and S into the infinite distance. My Hottentot guides told me, that the coast was not far on the other side of the sand dunes, and in fact we reached it on horseback after a six-hour ride. The surf was quite significant and seemed to have the same texture both to N and S, as far as we could see […] With our lack of provisions we could only stay for two days and had to try to catch up with our ox carts as fast as possible. From the beach, which was almost without vegetation, we returned over the mighty sand rampart to our camp behind it at the end of the Hoanib River, where our small cart was standing, and from here we drove in a SE direction in order to get the tracks of our ox carts under Rogers’ guidance. When we had the Hoanib River valley behind us, we found ourselves on a mighty plain, the so-called Namieb [Namib], which seemed to extend to the S as well as to the N in an infinite way, and which would have formed a single connected table or terrace, if I may say so, if it had not been cut by the Hoanib River valley. Far to the west, towards the coast, the eerie sand dunes shimmered, of the same nature as those sand dunes which prevented the Hoanib from flowing directly into the sea; on the other side, far to the east, there was a broad front, as it were a wall, the table and cone mountains of the inner Kaoko-Feld.

The Namieb was almost as flat and smooth as a table and travelling on it is extremely pleasant. But the vegetation here was very low: very sparse grass growth, here and there small crippled bushes and also the very occasionally occurring strange Welwitschia. We were in the barren coast region, which, like at Walfisch-Bai and Swakop-Mund, was around 60 km wide. […] The many brackish water points on the Namieb prove no less than the evidence of the sea from which the African continent became raised. By moving diagonally and southeast across the Namieb, we approached the central mountain area of the Kaoko-Feld from which the Namieb ran away. In the western part of this mountainous area we continued our journey to the south. We crossed the |Uni!ãb and ǁHu!ãb river and found our ox carts northwards from the Brandberg. In this last part of our journey in the middle of the mountain country, past deeply cut gorges with steep embankments downwards and just as steep higher up, the ground is literally sown only with rocks which consisted of fist-sized to child-sized pieces of basalt, this part of our journey was extremely tedious and arduous.64

Of particular relevance for the Northern Namib/SCNP is Hartmann’s later encounter with a so-called ‘decimated tribe’ he inscribes in rather derogatory terms as ‘the “Seebuschmänner”, the apparently bastardized Hottentot or crossbreeds between Hottentotten and Berg-Damara’, living ‘at the mouths of the |Uni!ab-river up to the Hoarusib and sleep[ing] where in the dunes the ǂNaras [!naras] fruit is to be found’.65 Hartmann includes in his text a photograph of these ‘Seebuschmänner’,66 reproduced here in Figure 12.5.67 Their body language appears proud and defiant; their attire a combination of what look like springbok and seal skins, as well as a hat worn by their ‘captain’ that seems to be of European design; and with knives worn around their necks, perhaps used for scooping out !nara melon flesh. ‘Seebuschmänner’ huts assumed to be abandoned are also photographed at ‘Rietgrasfontein’ close to the mouth of the Hoarusib River (Figure 12.6): perhaps those using them were simply avoiding Hartmann’s expedition. Also as part of this 1895–1896 expedition, von Estorff observes ‘deserted, circular reed huts at the Uniab River mouth’, and on return a month later finds here ‘a band of 30 “Bushmen” who had just arrived from the Hoanib River. They were living off narra for the most part’, with one ‘narra knife’ reportedly ‘made from elephant rib at the Hoarusib River’.68 In 1910, geologist Kuntz similarly meets “Bergdamaras” upstream on the !Uniab returning from the river’s mouth, where presumably they had been harvesting !nara;69 and writes of well-fed “Bergdamara” families from here to the Hoaruseb River north of Sesfontein.70

Fig. 12.5 ‘Group of sea-bushmen at Hoanib mouth; captain with a woman in the foreground’. Source: Hartmann (1897: 129, out of copyright), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Fig. 12.6 ‘Rietgrasfontein close to the mouth of the Hoarusib, on the north side of the spring, protected from the southwest wind, abandoned huts of the Seebuschmanner; two servants of Dr. Hartmann with horses’. Source: Hartmann (1897: 127, out of copyright), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Overall, Hartmann stresses the potential economic qualities of the Northern Namib. He emphasises: ‘fresh guano’ at ‘Cape Fria’, the Hoanib mouth and ‘|Uni!ãb mouth’; the ‘convenient landing place’ of the Khumib mouth, ‘about 600 km or by ship 3 to 4 days closer to Europe, than the Swakop mouth and Walfisch-Bai’, and which could be connected by railroad to ‘the Otavi mines’; and the ‘[t]he great value of the inland of Kaoko-Feld as cattle breeding land’.71 Drawing on information from his Khoekhoegowab-speaking guides, he also makes an intriguing comment regarding possible environmental change in the preceding decades:

[a]t the mouth of the Hoanib they showed me living sea-bushmen reed grass places between the sand dunes, which only fifty years ago were ponds, on whose islands thousands of birds nested. These ponds stirred from the groundwater of the Hoanib. In the same proportion as the country raised, the water level sank deeper. Today the ponds are dry. The birds can no longer live on the small islands where they were protected from the jackals […] But the fresh guano, which lies here still meters thick, reminds of their activity.72

This observation matches information for the more southerly !Khuiseb Delta area of the Namib. Here, freshwater springs in the dunes bordering the coastal lagoons at Walvis Bay and Sandwich Harbour made possible a rich cultural landscape of more than 220 archaeological sites, with extinct springs evidenced by ‘dense beds of reeds, Phragmites australis’.73

Use and habitation of the Northern Namib by Khoekhoegowab-speaking peoples is also signalled for the German colonial period in various maps, as indicated in Figures 12.7, 12.8 and 12.9 (also see Figure 1.16 in Chapter 1). For example, the Deutscher Kolonial Atlas of 1893 (Figure 12.7) names ‘Hubun’ as one of the peoples of the Northern Namib in the vicinity of the Sechomib, Hoarusib and Hoanib rivers, corresponding with the name ǁUbun referring to a particular grouping of !nara harvesters (as detailed in Section 12.3). This map also positions ‘Hottentot’—i.e. Nama—towards the coastal areas stretching north to south from the Sechomib to the ǁEseb/Omaruru rivers, as does the Karte von Deutsch-Südwestafrika of 1898, which names ‘Hottentot’ as present along the coast from Walvis Bay north to Nadas (Figure 12.8). A few years later a 1905 map of the territory positions ‘Bergdamara’ in the western reaches of the Khumib River area, ‘Owatjimba’ stretching towards the coast in the far north-west, and ‘Topnaar Hottentotten’ (Nama) west and south of ‘Zesfontein’ (Sesfontein) (Figure 12.9).

![Detail from the Deutscher Kolonial Atlas of 1893, showing ‘Hubun’ [ǁUbun] positioned in the vicinity of the Sechomib, Hoarusib and Hoanib rivers, and ‘Hottentot’ [Nama] in the coastal areas stretching north to south from the Sechomib to the ǁEseb/Omaruru rivers.](image/fig-12-7.png)

Fig. 12.7 Detail from Deutscher Kolonial Atlas of 1893, positioning ‘Hubun’ (ǁUbun) in the vicinity of the Sechomib, Hoarusib and Hoanib rivers in the north-west, and ‘Hottentot’ (Nama) in the coastal areas stretching north to south from the Sechomib to the ǁEseb/Omaruru rivers. Source: Sam Cohen Library, Swakopmund, out of copyright,

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

![Map detail from 1898, positioning ‘Hottentot’ [Nama] along the coast from Walvis Bay north to Nadas.](image/fig-12-8.png)

Fig. 12.8 Detail from Karte von Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1898, positioning ‘Hottentot’ (Nama) along the coast from Walvis Bay north to Nadas. Source: https://www.dhm.de/lemo/bestand/objekt/karte-von-deutsch-suedwestafrika-1898.html, out of copyright, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Fig. 12.9 Detail from 1905 map by Herrmann Julius Meyer—Meyers Geographischer Hand-Atlas, positioning ‘Bergdamara’ in the western reaches of the Khumib River area, ‘Owatjimba’ stretching towards the coast in the far north-west, and ‘Topnaar Hottentotten’ (Nama) west and south of ‘Zesfontein’ (Sesfontein). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10997145, out of copyright, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

The extreme disruptions of the German colonial regime in the early 1900s followed hot on the heels of livestock decline caused by rinderpest in 1897 (see Chapter 1), the effects of which radically reshaped the fortunes and governance of peoples living close to and within the present-day SCNP boundary and accessing its coastal resources. Nonetheless, travellers continued to report encounters with people in the Northern Namib. North of the Koigab and ǁHuab rivers in 1906, George Elers—on an expedition to seek northern deposits of guano—built a road so as to travel northwards towards Sesfontein, doing this with ‘a large number of Berg-Damaras who live in this [sic] Velds’ who showed him where water may be found.74 At Sesfontein, by now a German military post with a brick fort under the command of a Lieut. Smidt, Elers was informed that travel further north was ill-advised because of drought, but he nonetheless proceeded with guides westwards down the Hoanib, writing:

although it looked hopeless I decided to try and am glad to say got through to the mouth of the Hoanib. I got the cart down to the high dunes and proceeded over them with carriers.

I found plenty of water in the sand dunes but of very bad quality [e.g. at Auses?] and my oxen would hardly touch it although they had come through a long thirst. I also found much better water on the sea-side of sand dunes [the spring known as ǁGoada?] and there made my base. I stayed and examined all this part of the coast thoroughly. An old sea Bushman remembered the birds [white breasted cormorants] nesting there as he used to kill them for food and take the eggs.

From Hoanib I proceeded to Hoarusib, I found this the only river that has run for many years. I have no difficulty with water but could not get cart nearer the sea than 40 miles, on account of wash outs and dense reed and bush […] I found some Berg-Damaras and Bushman who live close to the sea and these people are constantly walking up and down the coast in search for whales that come ashore, you will find their Kraals all the way to Khumib and also a long way south to the Hoanib […] North of the Khumib it was impossible to go on account of the drought.75

The German colonial commercialising visions of the Northern Namib outlined above include the area now protected by the SCNP, somewhat belying its contemporary popular visibility as an untouched “wilderness”. It seems likely that the entrepreneurial intentions of the KLMG were already in tension with contemporaneous colonial concerns regarding the over-exploitation of hunted indigenous fauna—especially elephants. As discussed in Chapter 1, in 1907 these concerns played a part in the overlapping designation of the north-west as part of Game Reserve No. 2, stretching from Etosha Pan in the east towards the coast and the Kunene River (see Figure 1.17), and thus incorporating the northern part of the present-day SCNP.

12.2.3 Protectorate and South African administration: 1915–1990

Fragmented accounts through the changing South African administrative period again report local uses of the Northern Namib. For example, in his report of a journey to Kaokoveld in 1917, Major C.N. Manning—Resident Commissioner for ‘Ovamboland’ in the immediate post-WW1 years—refers to ‘Nama or Hottentot speaking people living at Zesfontein and nearer coast’.76 In 1942, Sesfontein Nama were recruited to assist an overland rescue mission to the shipwrecked British liner the Dunedin Star north of Angra Fria. They clearly knew routes and waterholes through the Northern Namib.77 In 1951 a scientific expedition to Kaokoveld financed by businessman Bernhard Carp collected thousands of different insects including ‘over 100 new forms’, underlining ‘the exceptional status of the Kaokoveld as a repository of biodiversity’, as well as ‘the “otherness” of the Kaokoveld’s fauna and people’.78 Bollig79 quotes a letter from Carp to the Administrator of South West Africa mentioning,

a forager population at the mouth of the Hoanib River. He records them as comprising “3 bushmen, 2 bushwomen, 3 Damas and 3 Dama-women”, and continues: “They were called Sandloopers [Strandlopers?] as they lived in the sand and also part of the year on the beaches of the coast, where they ate dead fish etc. Inland their diet consisted of grass veldkos and anything they could catch. They lived in scherms, no proper huts and had a very primitive life.80

This description clearly connects the people encountered on the coast with mobilities inland to acquire complementary foods (see Section 12.3).

In the late 1940s a government ethnologist for the former Dept. of Bantu Administration based in Pretoria also describes in Sesfontein a ‘group of Bushmen [who] calls itself Kubun (with click //ubun)’: ‘the informant said they originally came from a place called !kuiseb which is south of Walvis Bay, near the sea’, with he himself (called !Hu-!gaob) and his nephew |Nanimab ‘born where the !Uniab flows into the sea, about seven days walk from Sesfontein’.81 Van Warmelo’s informant had ‘never had a Bush wife’, but instead ‘had a Bergdama wife with whom he had several children, amongst them three daughters all living in Sesfontein’.82 Revealing preoccupations of the day with “pure” and “wild” “Bushmen” (also see Chapters 2 and 4), he states further that ‘[i]t seems as though there is only one pure Bush woman of this group still surviving’, who ‘also lives in Sesfontein and is married to a Bergdama’; and that only ‘[t]wo other pure Bushmen of this group survive’, who also normally ‘live out in the Namib and along the coast, eating what veldkos they can get and especially fish found along the shore’.83

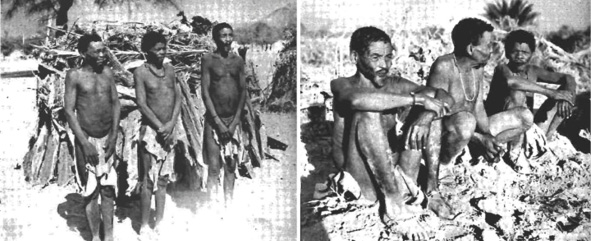

In May 1953 a Mr Louis Knobel from Pretoria in the company of Dr P.J. Schoeman—‘the Game Warden of South West Africa’ (see Chapter 2)—encountered in the Sesfontein community a group of people later described by archaeologist Raymond Dart in a somewhat dated text as:

a small group of coastal Bush-Hottentot folk consisting of three males and an ancient doddering female, said to be their mother, who were reported by the Topnaar Hottentot elders, their overlords, to be the last remnants of what was once a large body of Strandlopers. It was the custom of the Hottentots to allow these Strandloper retainers to go down to the coast each year when the narra fruit was ripe. […] On the coast this Strandloper group still subsists for several months on these fruit and the sea food found along the coast […], especially on the rocks about the mouth of such rivers as the Kumib and Hoarusib.84

Knobel’s photos form the basis of Raymond Dart’s 1955 account of this encounter. He tells Dart that ‘the boy who took them to the isolated huts where the Strandlopers were living informed them that his own father had been a Strandloper, but that his mother was a Topnaar Hottentot’; Schoeman additionally notes that ‘according to these Strandlopers’ own story, their stock had branched off from a Name [sic] Hottentot tribe, somewhere near the Brandberg […] in the Kaokoveld, but their predecessors had lived along the Skeleton Coast and up towards Rocky Point for hundreds of years’.85 The three ‘Strandloper’ men photographed in Sesfontein stand before a circular hut made of ‘pieces of wood, branches and palm fronds’ and are ‘clad in front and back aprons of buck-skin suspended from a girdle string, ear-rings and in one case a necklet of the type usually encountered amongst Bush peoples as well as rude sandals tied about their ankles with leather thongs’:86 see Figure 12.10. The paper proceeds with a rather objectifying account of the physical characteristics of the three men photographed.

Fig. 12.10 (L) ‘Three Strandlopers of Sesfontein S.W.A., standing in front of their rude hut built of wood, bark, palm fronds and grass’; (R) ‘The same three Strandlopers seated or squatting, the tall one on the right side of the previous picture having changed over to the left side in this picture’. Source: Dart (1955: 176, out of copyright), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

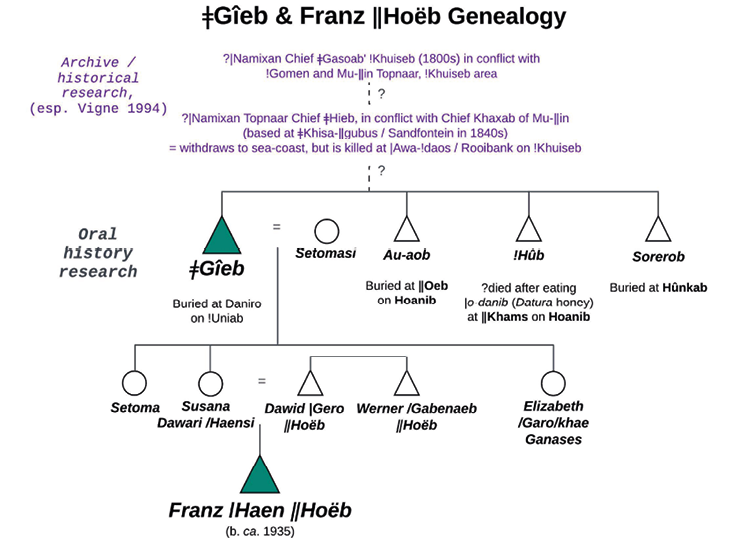

In May 2019, and again in March 2022, these 1955 images were discussed with Sesfontein resident Franz |Haen ǁHoëb, born ca. 1935 at Auses in the lower Hoanib and who grew-up as a !nara harvester of the Northern Namib.87 Franz recognised one of the men photographed here as called |Gabenaeb, known to be an enthusiastic dancer of |gais praise songs. This man is seated on the right, and also standing in the centre of the image on the left. His full name is Werner |Gabenaeb ǁHoëb, and he is an uncle of Franz: Franz’s father David |Gero ǁHoëb is the brother of |Gabenaeb—as indicated in the genealogy shared in Figure 12.11.

Fig. 12.11 Reconstructed genealogy of Franz |Haen ǁHoëb and his maternal grand-father, the remembered ǁUbun leader ǂGîeb (see Figure 12.19), drawing on oral histories with Sesfontein residents, and historical material in Vigne (1994: 8), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Fig. 12.12 Werner |Gabenaeb ǁHoëb (d.) plays goma-khās in Sesfontein. Photo: © Emmanuelle Olivier 1999 (no. 37), digitised by Sian Sullivan in March 2018, identification of musician made by W.S. Ganuses & S. Sullivan in May 2018. Used with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

It has been rather extraordinary to us to realise that |Gabenaeb pictured in these images from the 1950s and recognised in field research some 60 years later, was also recorded in Sesfontein in 1999 as an elderly man playing multiple ‘bow-songs’ (goma-khās), a musical genre formerly commonly played, often simply for ‘self-delectation’,88 i.e. for pleasure, delight, amusement and meditation. The image in Figure 12.12 is of |Gabenaeb, photographed in the early 1950s as an unnamed “strandloper” (Figure 12.10), playing goma-khās in Sesfontein in 1999. In the notes accompanying these recordings from 1999, the late Werner |Gabenaeb ǁHoëb plays songs whose names are suggestive of his preoccupations at this time: ‘We move towards Namib’, ‘Should I stay alone?’, ‘The camp has moved’, ‘Homesick’, ‘Who will cry’, ‘Springbok’, ‘I was left alone in the bush at Tceǁami’, ‘We will meet during the rainy season’, ‘Waterhole’, …

When pursuing this conversation with Franz in March 2022 more information about the men photographed by Knobel in 1953 came to light. The images are not in fact of exactly the same men, as conveyed in Dart’s 1955 paper. The man standing to the left in Figure 12.10 is Alfred |Nabunab, recalled—like |Gabenaeb—as someone who loved to dance |gais praise songs: but he is not photographed in the image on the right. |Nabunab is described by Franz as mostly staying with |Namimab (Huiseb) Xam-khaob, !Hûnib and Au-aob, the third of these men being a brother of Franz’s grand-father ǂGîeb (see Figure 12.11), who we will meet again below. All these men referred to ǂGîeb as their elder: as da kai. It is tempting to speculate that ‘|Namimab’ named here may have been the man referred to by van Warmelo above as ‘|Nanimab’, ‘born where the !Uniab flows into the sea, about seven days walk from Sesfontein’.

It seems clear that in the 1950s it was not uncommon for a network of individuals connected with the nodal settlement of Sesfontein to move between the coast and inland, in part so as to harvest !nara in the lower reaches of several rivers traversing the Northern Namib. The Khumib, Hoaruseb, Hoanib, !Uniab and Ugab are all mentioned as part of these mobilities, spanning a north-south distance of more than 200 kms. Figure 12.13 reconstructs reported mobilities between !nara in the !Uniab and Hoanib rivers and inland springs and dwelling places; also see Video 12.1.

Video 12.1. Lands That History Forgot: 1st Journey, Skeleton Coast & Hoanib River—Franz |Haen ǁHoëb, online:

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/49940025. © Future Pasts and Etosha-Kunene Histories, 2024, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

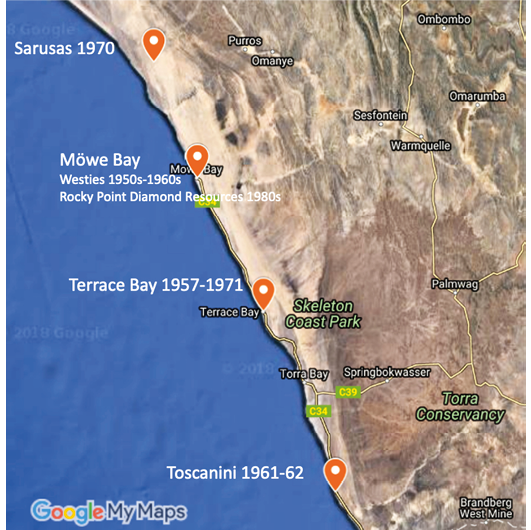

These documented histories and memories notwithstanding, in the early 1970s Etosha ecologist Ken Tinley89 writes of ‘recently extinct Strandlopers along the coast’. This statement is in a report commissioned by the Wildlife Society of South Africa concerning shifts to the then boundaries of Game Reserve no. 2 and Etosha Game Park (see Chapters 2 and 13). Tinley90 describes the previous distribution of these ‘Strandlopers’ as ‘discontinuous as they were governed by the occurrence of freshwater in the mouths of the seasonal rivers crossing the Namib Desert’: although ‘they also extended up some of the rivers traversing the desert’, writing that they ‘are extinct today except for one or two very old individuals living in Sesfontein’. He overlooks the role played in their ‘extinction’ by the establishment of mining concessions for diamonds and semi-precious stones through the northern Namib from the 1950s onwards: at Sarusas in the Khumib River, Möwe Bay, Terrace Bay and Toscanini (see Figure 12.14). Mining is one factor that created the Northern Namib as a restricted area, meaning that peoples using coastal resources were increasingly advised they could no longer access these areas and must become more permanently settled in the inland settlement area of Sesfontein.

Fig. 12.13 Reconstructed mobilities by ǁUbun (and others) to harvest !nara (Acanthosicyos horridus) melons from plants in the !Uniab and Hoanib rivers, now in the Skeleton Coast National Park, via inland dwelling places and springs including Kai-as and Hûnkab, based on site visits and multiple conversations with Franz |Haen ǁHoëb and Noag Mûgagara Ganaseb. Photos: © Sian Sullivan, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

These circumstances are invoked in a short film in which Sesfontein resident, the late Hildegaart |Nuas, tells of how Nama headmen from Sesfontein came to those living in the Hoanib west of Sesfontein saying, ‘you cannot stay here alone, you have to move to Sesfontein so that the government can recognise you’:91 see Video 12.2. Hildegaart’s parents, and her husband the late Manasse |Nuab, continued to go to the Hoanib !naras at the time of the year when they became ripe, bringing !nara cakes back to Sesfontein.92 It is likely that there was not only one event in which people were “encouraged” to remain in Sesfontein: people recall being moved to Sesfontein to work for Nama in the gardens there at the time when Husa |Uixamab—who died in 1941—was “captain”.93 When the Northern Namib became restricted as a mining area, however, it became harder to enter the area to harvest !nara:

now when the whites started making the diamond mines, now the government told the people that they have to move out and stay in Sesfontein. That’s why they are moving out from the places where they are living.94

Video 12.2 The late Hildegaart |Nuas of Sesfontein/!Nani|aus, Kunene Region, remembers harvesting !nara (Acanthosicyos horridus) in the dune fields of the Hoanib River. Video by Sian Sullivan, 2019, at

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/24efb33d, © Future Pasts, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Even then, however, people would travel up and down the Hoanib between Sesfontein and Möwe Bay. For example, Franz ǁHoëb, now resident in Sesfontein, worked as a labourer for both Sarusas and Möwe Bay mining operations, reporting how he and others from Sesfontein would travel to Möwe Bay on donkeys for work in the diamond mine there. Someone would come with them to take the donkeys back to Sesfontein. Others would also come to Möwe Bay bringing goats for consumption by the mine managers. The goats were reportedly grazed at places such as |Garis on the coast at the !Uniab mouth (see Figure 12.4), before being slaughtered for consumption by the mine managers. Sesfontein resident Jacobus ǁHoëb and former headman Simon ǁHawaxab, as well as ovaHimba residents, were also mentioned in this regard, i.e. as those who delivered goats down the Hoanib and across the Namib dunes to Möwe Bay.95

Fig. 12.14 Map showing locations of diamond and semi-precious stone mining in the Northern Namib, pre-1980. Source: data from Mansfield 2006, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

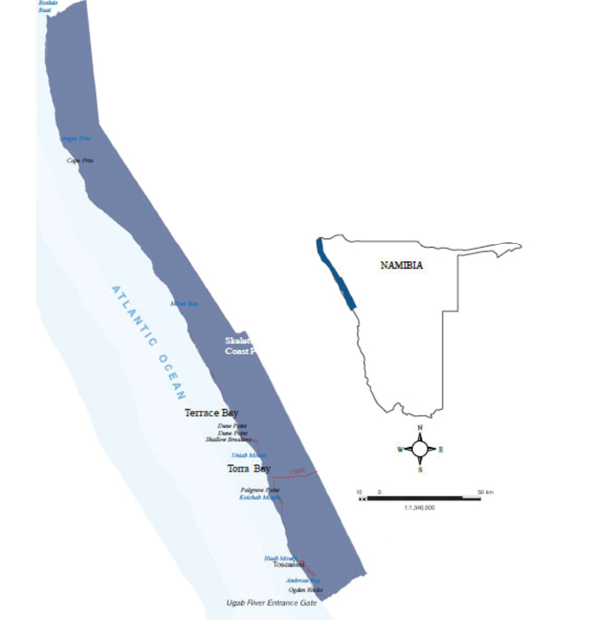

Iterative clearances of people and livestock from landscapes both west and south of Sesfontein (Chapter 13) acted to facilitate the multiple shifts in the boundaries of Game Reserve No. 2 and Etosha Game Park documented in Chapter 2, leading ultimately to incorporation of the Northern Namib as SCNP. The various boundary changes and reorganisations of people and livestock eventually cleared the way for proclamation of what was already a restricted area: in 1971 the Skeleton Coast National Park was established (see Figure 12.15), eventually encompassing the Northern Namib from the Ugab (!Uǂgāb) to the Kunene rivers, with Park entry requiring a permit.

Fig. 12.15 Boundaries of Skeleton Coast National Park, first proclaimed in 1971. Public Domain image,

https://skeletoncoastparkugabgate.wheretostay.na/, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

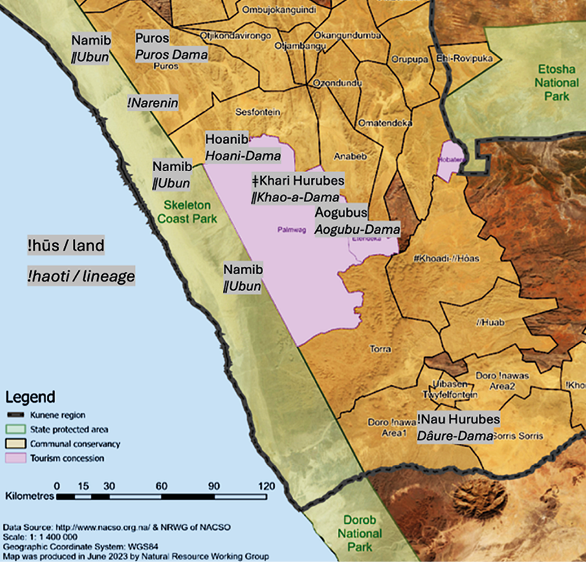

To summarise, Section 12.2 clarifies that for the duration of written accounts about the Northern Namib—overlapping into the pasts recorded in archaeological research and with oral history accounts into the present—a diversity of peoples accessed, used and inhabited this area. As well as those with little by way of livestock, they included Khoe/Nama and Damara/ǂNūkhoe pastoralists, with livelihoods and other practices overlapping in diverse and changing combinations so as to respond to dynamic environmental and political circumstances.96 The historical influences and boundary changes ushered in by European colonial venture, however, acted increasingly to fix new, bounded conceptions of the landscapes of the Northern Namib that restricted and contained prior mobilities, whilst creating new regimes of access, governance and use (Figure 12.15). Section 12.3 brings into further focus ways that the Northern Namib was once accessed and utilised by contemporary Indigenous Namibians, bringing to the fore their own accounts of who they are and why the coastal resources were important to them.

12.3 !Nara harvesters of the Northern Namib:

Contemporary oral history accounts

When the ǁUbun and ǁKhao-a peoples met in the rain time, for example at Kai-as, the ǁUbun would bring !nara [from the coast] and share with the others. The !nara has oil/fat inside. We would mix the !nara and the sâui and bosû together—it was delicious food!97

I was born at Auses where !nara grow, and I grew up in the Hoanib river. And from there we moved to the !Uniab river. And at the !Uniab mouth we collected the !naras. We put them into a big pot and then we strained that juice through a pot that has holes [in the bottom], and spread this juice on the dunes so that it can get “ripe”. And the seeds—we roasted the seeds and then mixed with the cooked juice and stored [the seeds] in the skin of a springbok.98

Many of the fragmented observations recounted in Section 12.2 are visible in recorded oral history accounts that put cultural and experiential flesh onto the bones of the historical records. In doing so, they help to rehumanise and re-individualise the often anonymising and objectifying observations of historical narratives and administrative documents.99 They also confirm that an ‘absence of Khoisan-speaking foragers in the oral record’ of more easterly ‘Himba and Herero informants in the 1990s and 2000s’100 is an artefact of that particular oral record, rather than a reflection of lives lived in the western and coastal areas by those whose accounts are documented below.

This section reports especially on remembered !nara use in interviews and oral histories gathered with Khoekhoegowab-speaking peoples in and around the northern settlement of Sesfontein (also known in Khoekhoegowab as !Nani|aus and ǂGabiaǂGao, and in otjiHerero as Ohamuheke101).102 A number of elderly people now residing in Sesfontein and its environs, and who refer to themselves as ǁUbun, !Narenin, Hoani-Daman and ǁKhao-a Dama (ethnonyms explained in Section 12.3.1), remember growing up in areas of what is now the Skeleton Coast National Park, harvesting from tended !nara “fields” there. Although drawing on research conducted in this area since 1992, most of the recollections below are from more recent oral histories gathered both at peoples’ present homes and on a series of journeys west of Sesfontein to the lower reaches of more northerly westward flowing ephemeral rivers (the !Uniab, Hoanib and Hoaruseb)—images of some of these “key informants” are included by request and with permission in Figure 12.16. Given the terrain of the Northern Namib, and the difficulties of carrying out on-site field research with contemporary elders of the Hoanib communities with direct memories of sites within the SCNP, the localities retrieved in this way are sparse but significant. As documented in more detail below, they should also be understood as forming part of complex past patterns of mobility and livelihood practices connecting coastal sites and resources—especially !nara, but also marine resources such as mussels and seals—with inland sites where a different complement of foods could be obtained (see Figure 12.13).

Fig. 12.16 Portraits of Sesfontein residents who participated in the oral history research shared here. Top, L-R: the late Manasse |Nuab; the late Hildegaart |Gugowa |Nuas; Franz |Haen ǁHoëb; Noag Mûgagara Ganaseb. Bottom, L-R: Christophine Daumû Tauros; the late Michael |Gâmigu Ganaseb; the late Ruben !Nagu Sanib. All portraits commissioned from Oliver Halsey, May 2019, except Manasse |Nuab’s by Sian Sullivan, 1994. © Future Pasts, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

12.3.1 Who and where?

Fig. 12.17 Reconstructed land-lineage groupings for Khoekhoegowab-speaking Damara/ǂNūkhoen and ǁUbun in north-west Namibia. Note that oral history also makes clear that there was much mobility and reciprocity between these lineages and land areas, as well as by other ethnic groups, especially Nama, and ovaHimba/ovaHerero. Authors’ research, © Future Pasts, underlying map adapted from Figure 3.2, used with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

!Narenin were living in the western areas of Hoanib and Hoarusib. Where we were just now [i.e. Hûnkab area] was ǁUbun land. ǁUbu people were living in the places close to the ocean like Hûnkab, !Uniab, |Garis, Xûxûes. Those are the areas of Huri-daman ǁUbun di !huba [lit. the ‘Sea-Dama (i.e. !Narenin) and ǁUbun land’].103

For the Northern Namib within living memory, harvesters and consumers of !nara have tended to be associated with four main land-lineage groupings (!haoti): !Narenin, ǁUbun, Hoanidaman and ǁKhao-Dama (see Figure 12.17), all of whom are now represented by the Nami-Daman TA. In this area of north-west Namibia beyond the “Red Line”, where Damara/ǂNūkhoen and ǁUbun have retained some continuity of habitation for at least several generations, relationships of belonging linking familial groups (!haoti) with named areas of land (!hūs)104 have continued into recent years to shape peoples’ understandings of their identity and histories.105 As noted above, and through circumstances not of their choosing, from especially the 1950s these lineages became concentrated in Sesfontein and associated settlements, whilst continuing to travel to places dwelled in and known from past experience, as well as to retain memories of these places (also see Chapter 13).

!Narenin were/are Damara/ǂNūkhoen associated with the western reaches of the northerly Hoanib and Hoaruseb rivers, who for as long into the past as people can remember, relied significantly on !nara, hence their ethnonym. They harvested !nara from the Hoaruseb River and from near springs called Dumita (towards the mouth of the Hoaruseb), Ganias (north of the Hoanib) and Sarusa (in the Khumib), combining !nara foods with other plants:106

[…] my great, great-grandfathers and mothers were there at Sarusa, and I was born here [in Hoanib] at ǂHoadiǁgams.107

The !Narenin people are the people of Sarusas and down there in Hoanib […].108

[…] my family are the people who are/were living in the !nara area, and they collect the !naras—that’s where the name [!Narenin] is coming from.109

[…] they would move in between the Hoaruseb and Hoanib. In Hoanib in the rain time they came here to collect food, especially ǂares110 and ǂnamib111—the latter is not found in Hoaruseb. At this time they wore leather skirts from springbok leather. They would collect lots and take back bag by bag to the Hoaruseb. The !naras grow ripe in the Hoaruseb at this time and were harvested by !narab Dama [!Narenin].112

Coastal foods were clearly important alongside !nara. The late Michael Ganaseb, for example, described cooking mussels in black ceramic pots—!nomsus—in his early life in the Northern Namib.113 These coil pots were made using clay—sohai—whose sources in the landscape were shrouded in some secrecy.114 In recent generations at least, !Narenin and ǁUbun would interact and intermarry in these northern Namib areas:

[t]he !Narenin people were living in Puros and the ocean side is where the !naras are living, and the ǁUbun were at !Uiǁgams/Auses in the Hoanib. Now when they are looking for the food they meet and it’s where the !Narenin men take the ǁUbun women and the ǁUbun women take the !Narenib,115 like that.116

ǁUbun are Khoekhoegowab-speakers sometimes referred to as ‘Nama’ and at other times as ‘Bushmen’, who had been living in the ocean side north of the !Khuiseb, reportedly for generations.117 They are likely to be amongst those coastal peoples associated with the term “Strandloper” in historical texts. In recent generations they are known to have experienced conflict with !Khuiseb Topnaar when those who became known as ǁUbun requested to be given milk but were refused. The story goes that long ago a woman on the !Khuiseb (at Utuseb) did not want to give her sister the creamy milk (ǁham) that the latter desired,118 leading ǁUbun to retreat northwards close to the ocean (hurib)119—‘[t]hat’s why they called them Hurinin’.120 As Franz ǁHoëb describes,

there in the !Khuiseb there was a conflict between the families. One doesn’t want to give the other the milk of the goat—that’s why they are angry. And they left the !Khuiseb for the !Uniab.121

ǁUbun are linked with many former dwelling sites located in the Namib close to the ocean in this far westerly area. At the !Uniab River, reportedly a !nara plant was found by their dog and when they saw the dog eating the !nara without being harmed they also started eating the !naras there.122 As noted in Section 12.2, the presence in the Northern Namib of people named ǁUbun appears confirmed during German colonial times by the name ‘Hubun’ in the lower reaches of the Hoaruseb and Hoanib rivers on the Deutscher Kolonial Atlas of 1893 (Figure 12.7).

In recent generations, ǁUbun moved between !nara fields in the !Uniab and Hoanib river mouths via Kai-as and Hûnkab springs, now in the Palmwag Tourism Concession:123 see Figure 12.13. They also stayed at Dumita in the lower Hoaruseb where there is a spring,124 and are considered to be:

[…] the people who built the houses at Terrace Bay and Möwe Bay and were living there. Those circle houses with the rocks at !Uniab are also the houses of the ǁUbun—my great grandparents were coming from those rock houses.125

[…] when other people saw them in the Namib with their houses built very close together (‘ǁubero’) they exclaimed over the way the houses were being made—hence the name ‘ǁUbun’.126

[…] the ǁUbun people are the people who are coming from Walvis Bay. Now along the ocean there are the huts of the ǁUbun people they built with ribs of the whale.127

The reference here to ǁUbun building huts with ribs of the whale is intriguing. Archaeological research reported in the SCNP Management Plan, dates a whalebone hut and shell midden located south of the Ugab River mouth in Dorob National Park to approximately 1,000 years ago.128 As mentioned in Section 12.2, whale bone material is also reported in association with hut circles north of the Munutum in the Northern Namib.129 Jill Kinahan130 writes that,

[a]fter catching and stripping the blubber from a whale, the Americans [whalers] would dump the carcass overboard, providing the coastal people with a bonanza of fatty meat, and gigantic bones which could be used for building material.

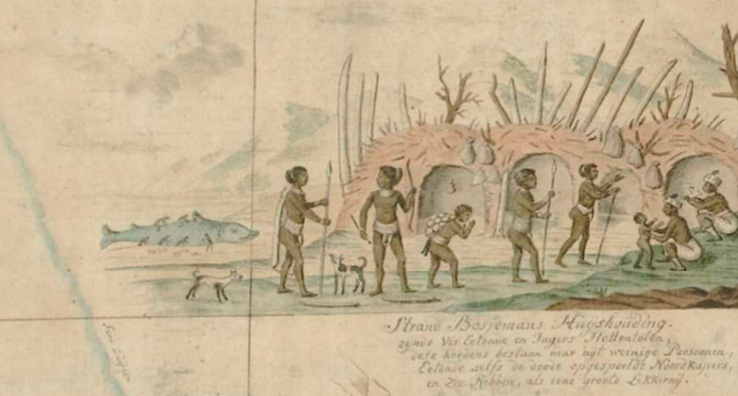

Fig. 12.18 Detail of ‘Strand Bosjmans’ village from ‘Historical map, Orange River to Karas Mts., SWA’, apparently created as a composite of multiple sources of information from different expeditions, including that led by Hendrik Hop in 1761–1762 accompanied by surveyor Carel Brink (Mossop 1947: 50), although attributed to Robert Jacob Gordon 1786. Source: open image Kaart van Zuid-Afrika (RP-T-1914-17-3), https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/object/Upper-northern-half-of-Gordons-great-map-of-Southern-Africa--2e2c01cff5ad98bda9ac53b3d17094ba, Rijks Museum, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Whaling along Namibia’s Atlantic coast took place through the 1700s into the 1800s, so it could be expected that whale bone huts benefitting from whale hunting would also be of a more recent age. A late 1780s image of a ‘Strand Bosjemans’ (‘Beach Bushmen’) village, for example, is constructed of whale bones, and positioned on the coast north of the Orange (!Garib) River: see Figure 12.18. In the image, the huts are placed very close to each other, the family grouping is accompanied by several dogs, a beached whale is being butchered to the left of the huts, and one human figure in the centre is carrying on their back what appears to be a heavy bag filled with ostrich eggs used for storing potable water. It is possible that there may once have been whalebone settlements in the Northern Namib that looked something like this image—as indicated by the whalebone ‘encampment’ at the mouth of the Ugab ‘constructed from ribs and mandibles of the Southern Right Whale Eubalaena australis’.131

It seems possible that contemporary ǁUbun are descendants of a ‘Topnaar group’ called |Namixan who, in the 1800s under their ‘Chief ǂGasoab, lived in the !Khuiseb’, coming into conflict with Topnaar groups called !Gomen and Mu-ǁin, which continued ‘between ǂGasoab’s successor, Chief ǂHieb, and Chief Khaxab of the Mu-ǁin’.132 The |Namixan reportedly withdrew ‘to the sea-coast’ from where ‘Chief ǂHieb and two companions travelled secretly to Rooibank [in the lower !Khuiseb] to look for any of his people left there’, being ‘surprised at a Mu-ǁin werf [settlement] by a commando which attacked from the dunes rather than approaching them along the river, killing Chief ǂHieb and his companions’.133 The |Namixan were again driven away ‘under Chief ǂHieb’s son’.134

Given known naming practices in which sons of lineage leaders in particular may take on their father’s name, the possibility exists that ‘Chief ǂHieb’s son’ mentioned above is connected with the maternal grand-father ǂGîeb remembered by the elderly ǁUbun man Franz ǁHoëb, born at the !nara fields near Auses in the lower Hoanib river and now living in the vicinity of Sesfontein/!Nani|aus: see reconstructed genealogy in Figure 12.11. Franz remembers his family harvesting !nara in the lower Hoanib and moving between !nara fields in the !Uniab and Hoanib via Kai-as. In May 2019, Franz ǁHoëb led us to the grave of his grand-father ǂGîeb in the lower !Uniab river, located exactly as mentioned in numerous prior interactions, in the present-day SCNP (see Figure 12.19). ǂGîeb’s grave is next to the former dwelling site called Daniro (the place of honey, danib), where ǂGîeb and others first encountered German men travelling down the !Uniab; described to Franz as being the first occasion when these ǁUbun had seen white men and encountered food in tins—as recorded in the first journey film in Lands That History Forgot (Video 12.1). This encounter was perhaps the 1896 journey by von Estorff related in Section 12.2, in which ‘Bushmen’ harvesting !nara in the !Uniab mouth are described.135 When we relocated this grave spoken of in previous interviews, there were imprints of footsteps all around it which we later learned were from a running event of around 40 people across the park, held in April 2019. It would mean a lot to descendants of ǂGîeb living in the Sesfontein area today for this grave to be marked and protected from human and animal disturbance into the future.

Fig. 12.19 Franz |Haen ǁHoëb stands at the grave of his grand-father ǂGîeb. The footsteps from a recent sports run across the desert are clearly visible on either side of Franz. Photo: screenshot from the film Lands That History Forgot (2024, Video 12.1), © Future Pasts/Etosha-Kunene Histories, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Hoani-Daman is an ethnonym attributed to Damara/ǂNūkhoe families linked especially with the lower reaches of the Hoanib River, where the plant foods !nara, xoris and ǂares are found. The late Hildegaart |Gugowa |Nuas (née Ganuses), for example, lived her early years with her parents at places where plants of the !nara melon (Acanthosicyos horridus) grow in the dunes of the !Uniab and Hoanib Rivers in what is now the SCNP (see Video 12.2). In the Hoanib, the places where Hildegaart’s parents stayed were called ǁHoas and !Uiǁgams, near Auses waterhole. Here, and as detailed in Section 12.3.3, each family had their own !nara plants from which to harvest.136

When the !nara harvesters of the Northern Namib relocated more fully to Sesfontein, the Nama leadership gave them gardens so they could start planting food. They began wearing European-style clothes instead of the skins of springbok they had worn when ‘in the field’. But Hildegaart’s parents continued to go to the !naras at the time of the year when they became ripe. They would move down the Hoanib and bring !nara cakes back to Sesfontein. Up until the 1990s, Hildegaart’s husband, the late Manasse ǁGam-o |Nuab, continued to go to the !nara fields of the Hoanib, bringing back bags of !nara on a donkey to Sesfontein.137

ǁKhao-a Dama are associated with the area further inland known as ǂKhari (‘small’) Hurubes (also ǁHurubes), and are a grouping that in times past were connected with ǁKhao-as mountain, a large mountain at the confluence of the ǂGâob (Aub) and !Uniab rivers in the present-day Palmwag Tourism Concession (see Chapter 13). Although apparently not harvesting !nara themselves, they appreciated the !nara that was shared by others, as illustrated in the quote opening Section 12.3. The extent of past mobilities of these peoples through the north-west landscape and Northern Namib is often commented on by elderly people interviewed today who lament the loss of access and social autonomy characterising these remembered pasts:

we moved also from Kai-as to the places where the food is. Even we go far away: behind that Puros side it’s also the place where the kai khoen (old people) go for !naras.138

It should be noted that Khoekhoegowab-speaking peoples were/are not the only inhabitants documented in recent decades as accessing the Northern Namib and utilising !nara. After rain in December 1984, anthropologist Margaret Jacobsohn observed possibly Tjimba lineage members spend about three months at ‘Sechomib wet season camp’—described as a few kilometres from ‘Ochams spring’, ‘70kms N-W of Purros’—taking ‘advantage of good local pasture for their goats and a large crop of ripe !nara’.139

12.3.2 When?

Oral histories are clear that the harvesting of !nara required sensitivity to its seasonality, and its complementary use with other seasonally available foods:

[a]nd the people also knew when it’s the !nara time—for collecting, for harvesting—and when the !naras were finished then we would move to Kai-as and collect honey and grass seeds [sâui]. And we were also hunting springbok [Antidorcas marsupialis] and oryx [Oryx gazella]. And if we saw, ok, this is now the time of the !naras then we would go from Kai-as to !Uniab again to collect the !naras.140

Ok, now, from Hûnkab to the other side it’s a ǁUbun area and the ǁUbun people were living in that ocean side [Namib !hūs]. And when it is now the rainy season, and after the rain, June-July, they came to Kai-as and Uruhûnes [Urunendis] looking for sâu, bosû and honey [danib]. And then when it is finished they go back again to the !naras places where the !naras is, and they eat the !naras.141

It is said that Franz’s ǁHoëb’s grandfather ǂGîeb, whose grave is located behind the !Uniab river mouth dunes (Figure 12.9), would observe the fruit of Boscia albitrunca (|hûnis) becoming ripe and would use this as the signal that now is the time for the !naras to also become ripe:

[n]ow that time the people they don’t count the months. They only check it on the trees. They say ok, if the shepherd tree is ripe then they know that the !naras is also ripe and they go [there] at that time to the !Uniab. But the shepherd tree—the time when this is ripe is October.142

ǂGîeb would reportedly walk alone to !Uiǁgams/Auses to check the !nara. When he saw the !nara is ripe he would return to !Uniab side and say to the people you can go now and ‘milk the cattle’, but you must not take the ones that are not ready yet to get calves (i.e. only take the ones that are ripe).143 Franz and his cousin Noag Mûgagara Ganaseb recalled these mobilities which they experienced as children and young people: ‘[w]hen we are young now we move from place to place and when we get tired so we sleep there […] until we reach Auses, for the !nara’.144

12.3.3 How?

The oral histories of !nara harvesters of the Northern Namib echo what is known for practices of ownership, management, harvesting and preparation of the !Khuiseb delta !nara harvesters.145 References to these practices as also those of their ‘great-great-grand-fathers’ indicates cross-generational longevity of !nara harvesting in these areas. The loss of access to this valued food is lamented by those who remember harvesting it in the Northern Namib:

it was the food we are eating in the past and we also want to go and collect it, but now the government doesn’t want the people to collect the !naras. You have to have a permit to go and collect.146

At Auses and elsewhere in the Northern Namib, specific !nara patches were owned and managed in the same ways as described above for !Khuiseb !nara. Thus,

[w]hen they came to the !nara plant, everyone has got their own !nara—they are divided. So if you collect the seeds and the Salvadora berries [xoris] then you can come from Ganias to the !Uniab to collect grass seeds [sâui]. But not the !nara. If you came from Ganias to !Uniab then the people who are there can give you the !naras, but you can’t go and collect [from these plants]. So the thing is also, they divided the plants—when it is the !nara harvest time then everyone goes to their !nara—ǁUbun go to the !Uniab [and Auses], and !Narenins go to the Ganias [north of Auses] for the harvest time. But for the grass seeds time—they came together. And they can move to another place, like the !Uniab, and collect the grass seeds. But when it comes to the !nara time then each person can go to their own places and collect the !nara. Their great-great-grandfathers who were there had those rules to divide the !nara plants. It was their great-great-grandfathers.147

Perhaps unsurprisingly, cooking and preparing !nara fruits and seeds for consumption is also consistent with the processing technologies documented for the !Khuiseb delta !nara: