13. Historicising the Palmwag Tourism Concession, north-west Namibia

©2024 Sian Sullivan, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0402.13

Abstract

The Palmwag Tourism Concession comprises more than 550,000 hectares of the Damaraland Communal Land Area in Kunene Region. To the west lies the Skeleton Coast National Park. Otherwise, the Concession is situated within a mosaic of differently designated communal lands to which diverse qualifying Namibians have access, habitation and use rights: namely, Sesfontein, Anabeb and Torra communal area conservancies on the Concession’s north, north-east and southern boundaries, with Etendeka Tourism Concession to the east. Established under the pre-Independence Damaraland Regional Authority led by Justus ǁGaroëb, Palmwag Concession lies fully north of the veterinary fence or “Red Line” that marches east to west across Namibia. In the 1950s, however, the Red Line was positioned further north with part of the current concession comprising a former commercial farming area for white settler farmers, the expansion of which was associated with evictions of people living here. The iterative clearance of people from this area also helped make possible the 1962 western expansion of Etosha Game Park, followed by the establishment of a large trophy hunting concession between the Hoanib and Ugab rivers in the 1970s. Drawing on archive research, interviews with key actors linked with the Concession’s history, and on-site oral history with local elders through much of the Concession’s terrain, this chapter places the Concession more fully within the historical circumstances and effects of its making. In doing so, competing and overlapping colonial, Indigenous and conservation visions of the landscape are explored for their roles in empowering different types of access and exclusion.

This chapter is dedicated to Ruben !Nagu Sanib, with whom I have worked over the last 10 years. Ruben sadly died on 7 June 2024, as the proofs for this book were being finalised. His knowledge and experiences have contributed significantly to this chapter, especially in Section 13.3.

It has been a great privilege to learn from and journey with Ruben to the area of the

Palmwag Concession he knew as Hurubes.

13.1 Introducing the Palmwag Tourism Concession1

The Palmwag Tourism Concession in north-west Namibia comprises an area of more than 500,000 hectares sitting between the Hoanib River in the north and the Koigab River in the south. As Figure 13.1 shows, the concession is surrounded by a mosaic of different land designations: the Skeleton Coast National Park (SCNP) is to its west, Sesfontein, Anabeb and Torra conservancies are around its north, north-east and southern borders, and Etendeka Tourism Concession is to its east. The area is of high international conservation value, especially for its populations of desert-adapted black rhino (Diceros bicornis bicornis), elephant (Loxodonta africana) and lion (Panthera leo). It is also valued in conservation terms for its positioning between Etosha National Park (ENP) in the east and the SCNP in the west, discussed further in Section 13.4. This positioning led to its promotion in the 2000s as part of a proposed Kunene People’s Park2 that is also listed as a current aim of work by the Namibian branch of the World Wide Fund for Nature.3 In recent decades the concession has become an important tourism destination. Namibia’s Gondwana Collection of Lodges4 now holds the lease to the concession’s main tourism facility, Palmwag Lodge.

Fig. 13.1 Map showing the Palmwag, Etendeka and Hobatere Tourism Concessions in between Etosha National Park in the east and the Skeleton Coast National Park in the west. The yellow asterisk marks the location of Palmwag Lodge, and the black dots mark contemporary rural settlements. Base map © Jeff Muntifering, 2019, for Future Pasts research, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

The Palmwag area is often described in tourism and conservation literature as a pristine “wilderness”. An example is this statement advertising accommodation at Palmwag Lodge: ‘[f]eel the freedom of the north-western corner of Namibia, one of Africa’s last wildernesses […]’.5 I must admit that this was also exactly how I perceived the landscape when I first camped at the lodge’s campsite in 1990. Through research in this area from 1992 onwards, however, I have come to understand that the landscape is replete with cultural histories, identities and memories. Historical documentation tells of people living and moving through this area in the past, being progressively removed from the area, especially as parts of it became commercial farmland for white settler farmers in the mid-1950s (Section 13.2). Oral histories convey the complexities of former dwelling and mobility practices in the area, and the heart-ache experienced through progressive loss of access to localities considered to be home (Section 13.3).6

This chapter seeks to convey some of these historical circumstances and to make experienced histories of the area more visible. It places the creation of the Palmwag Tourism Concession within the historical circumstances of its making: hence the term “historicising” in my title. In Namibia, the notion of a concession for particular kinds of use within a land area dates back to before German colonial times.7 As an example, a deed of transfer endorsed by Major Leutwein in 1896 reads:

‘[t]he purchaser is entitled to graze and water his livestock at any place of his choice on the parish land of Barmen. For this concession, the purchaser shall pay a unique amount of 40 mark’.8 In the case of the Palmwag Tourism Concession today, the term ‘concession’ refers to the rights of a tourism operator to develop and profit from tourism infrastructure, without competition from other operators in the area, through a contract with the ‘concessionaire’ of the area.9 For Palmwag, the concessionaire is currently the “Big 3 Trust”: a Trust formed from the leadership of the three conservancies surrounding the concession, namely Sesfontein, Anabeb and Torra (see Figure 13.1, Section 13.6 and Chapter 3). This situation, however, is a relatively new arrangement. It is built on layers of history that are more-or-less occluded or invisible today.

In attempting to bring more of these layers of history into visibility in the present, I consider the following elements of this history. I start in Section 13.2 by documenting the significance of the 1950s–1970s expansion of white settler farming into the area, made possible by a change in the north-western boundary of the Police Zone in 1955. I then connect this mid-twentieth century history with some of its consequences for people who thought of this area as home, by going back in time chronologically to give some indication of pre-1950s Indigenous use and mobilities through this area (Section 13.3, also see Chapter 12). I then touch on the 1970s creation of the “Damaraland Homeland” that included these areas previously lived in by especially Damara/ǂNūkhoe and ǁUbu peoples. I focus here on the ways this event was articulated as a crisis for conservation by ecologists and conservationists (also see Chapters 2 and 12). I outline alternative conservation visions proposed at this time whose symbolic power remains potent in the contemporary moment (Section 13.4, also see Chapter 3). I also document how a large area including and extending beyond the present-day Palmwag Concession was established as a hunting concession in the late 1970s. In Section 13.5 I outline the subsequent shift to the area’s present form as the Palmwag Tourism Concession, created under the Damaraland Regional Authority (DRA) in the 1980s. Finally, in Section 13.6 I consider some of the recent history of the concession after Independence, in relation to the establishment of conservancies in the area, their new responsibilities as the concessionaire, and various new proposals for enhancing protection of the area. Running throughout these layers of history are juxtapositions and tensions between colonial, Indigenous and conservation visions of this celebrated, but variously constructed, ‘Arid Eden’10 (Figure 13.2) and ‘last wilderness’.11

Fig. 13.2 Popularised through the memoir An Arid Eden by well-known conservationist the late Garth Owen-Smith, ‘the Arid Eden Route’ has become a way of framing and selling tourism in north-west Namibia as ‘Unimagined. Unexpected. Unexplored’. Photo: © Sian Sullivan, 2.11.2014, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

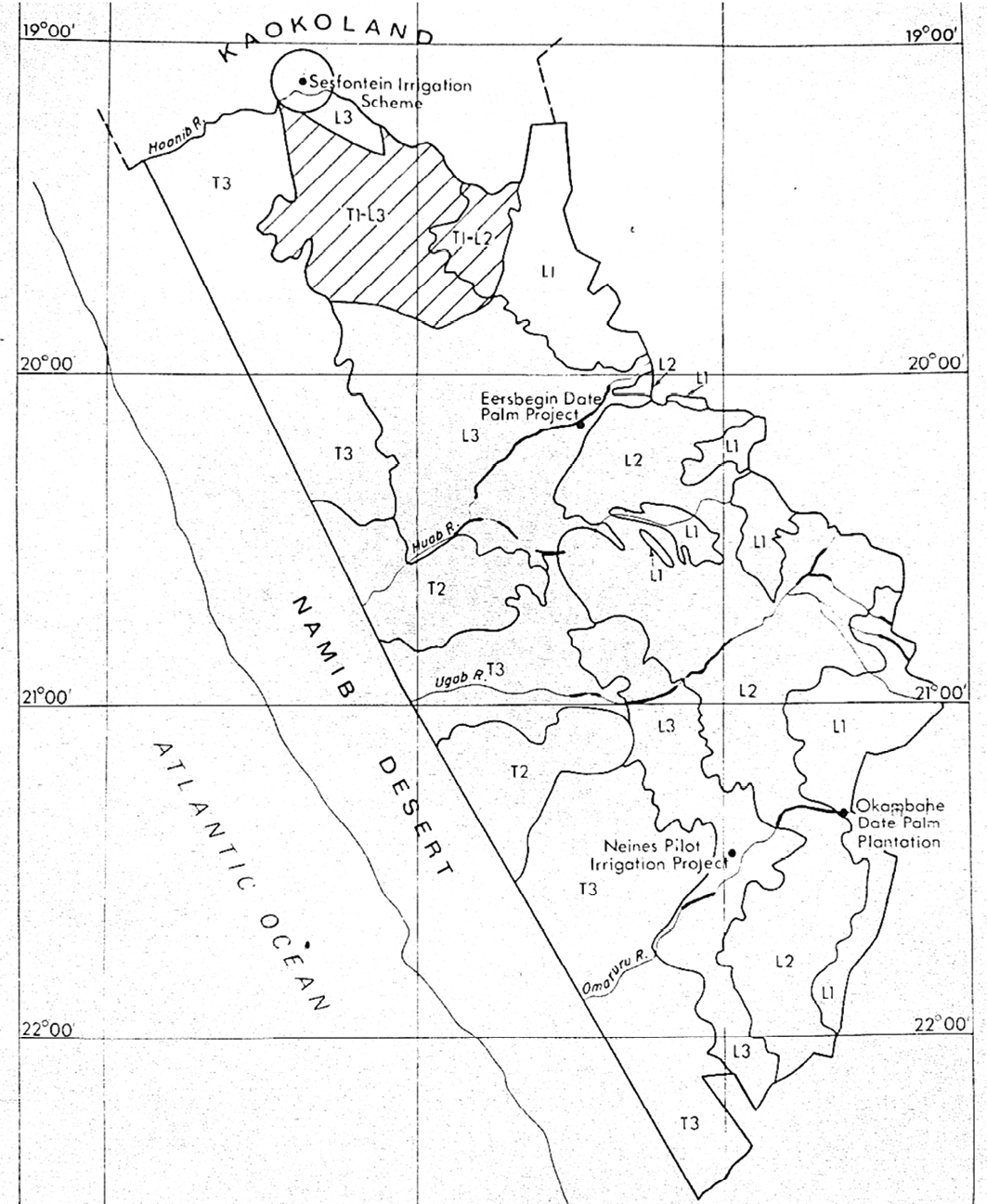

13.2 The “Police Zone” expands into the north-west

A major event in the history of this part of north-west Namibia was the expansion of the so-called “Police Zone” in 1955. As documented in Chapter 2, the Police Zone was the area of former South West Africa (SWA) where the then South African government permitted commercial farming by white settler farmers. Already in 1939 the South West Africa Administration (SWAA) conveyed interest in expanding European settlement in this area, observing that ‘the only portion really suitable for European settlement is the small corner […] now in the cattle-free zone between the Kaokoveld and Outjo districts’.12 In 1955 the Police Zone area was expanded in this north-westerly direction to the limit of the orange area on Figure 13.3. The red line across this map marks both the new northern boundary of the commercial farming sector and a border across which livestock, fresh meat and other agricultural produce from Indigenous farming areas to its north should not cross,13 although it remained unfenced at the time in the north-west.

What many visitors to this ‘last wilderness’ today probably do not realise is that part of the Palmwag Concession was designated in these years as commercial farmland for white settler farmers. The area north of this commercial farmland (coloured in yellow on Figure 13.3) was intended as a “livestock-free” zone, but appears to have been more aspirational than reality—especially in the landscape around settlements in the Hoanib valley such as Sesfontein, Warmquelle and Kowareb.14 This area had long been utilised for herding by varying combinations of Nama, Damara/ǂNūkhoe, ovaHerero and ovaHimba herders, as documented further in Section 13.3. Indeed, only a few years previously (in 1949) the Native Commissioner for Ovamboland—Pritchard Eedes—made a commitment to inhabitants of ‘Kaokoveld’ and ‘Zessfontein’ to supply them with more rifles and ammunition to enable them to destroy ‘certain classes of vermin’, namely predators such as lions and hyena known to attack livestock in these farming areas.15 The expansion of commercial farmland in 1955 nonetheless acted to prevent local land-users from living in, accessing and utilising the newly surveyed and designated lease- and free-hold farming area. The north-westerly boundary of these farms—the areas bounded with straight lines on the map in Figure 13.4—comprised the new Police Zone boundary, as marked on Figure 13.3. Although no fence was constructed here at this time, the Police Zone boundary was etched into the landscape as cleared cutlines that remain visible today.

Fig. 13.3 Map showing the 1955 positioning of the Police Zone boundary (marked in red), which permitted the north-westerly expansion of the commercial farming area (in orange) into the area now demarcated as the Palmwag Concession. The yellow-shaded area on land variously designated as “native reserves”, as well as part of Game Reserve No. 2 in the north-west, was intended as a livestock-free zone, but was difficult to police. Source: Map 7 from Miescher (2009: 282, used with permission), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

The most north-westerly farm in this newly expanded settler farming area—Farm 702 on Figure 13.4—became known as Palmwag Farm, the name Palmwag variously translated as ‘Palm wait’, ‘Palm guard’, ‘Palm risk’ or ‘Palm venture’. The current tourism concession is named after this name for the previous commercial farm. Drawing on archival research by Jack Kambatuku regarding the inhabitants of commercial farms in the area that in the early 1970s became designated as Damaraland (see Chapter 2),16 a reconstructed history of Farm 702 indicates that it was settled by various white farmers and their livestock on and off from 1954, until the farm became available for incorporation within the Damaraland Homeland in 1972.

Fig. 13.4 Map showing the expanded commercial farmland area in north-west Namibia: the north-west boundaries of the surveyed farms mark the 1955 Police Zone boundary, and farm 702 is “Palmwag Farm”, now the site of Palmwag Lodge. The names in blue mark the ephemeral westward-flowing rivers of this area. Source: Adapted from Sheet 6, Fransfontein, Surveyor General’s Office Windhoek, undated, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

As Kambatuku documents,17 in August 1954, Farm 702 was advertised for landless white farmers to apply for a grazing license: 9 farmers applied, and J.M.L. Carstens was successful. At this point he was sub-leasing Twyfelfontein farm on the Aba-ǁHuab River further south, and had been moving around in this area for a couple of years. Providing some idea of the sizes of herds brought into the expanded commercial farming area in these years, Carstens moved 808 sheep, 300 goats and seven cattle to Palmwag Farm; also gaining permission from the Land Board for 700 small stock owned by a neighbour to graze there. The farm depended on open water from the !Uniab River with ‘2 wells fitted with portable engines and a dam (impoundment) with a centrifugal engine drawing water from it’.18 In January 1964 Farm 702 was purchased by Carstens using the Administration’s buying option, reportedly for £1,506 [apparently R3,009.86, according to historical data].19 In this same year the farm was tendered for sale back to the Administration and valued at R44,946. It was eventually purchased by the Government for R56,000, with Carstens remaining as a lessee for R83/month from October 1964. If these figures are correct, it appears that the farmer would have gained considerably from this transaction. The stock numbers remained roughly the same through these years, with the addition of two horses and two mules.

In January 1965, the lease was awarded to R.V. Madsen from Gobabis district, but was cancelled in April 1965 because he was not considered to be a bona fide farmer since he was also a businessman who owned a store in Gobabis. Madsen negotiated to remain with his 2,500 sheep, vacating the farm in April 1966, after which it remained unoccupied until February 1969 when it was leased to an H. Steenkamp, with an F. Jooste also awarded a lease contract, but this farmer left due to poor grazing. In 1971, a Mr P. de Wet applied to lease the farm but was not granted the land due to poor pastures in this year. It was only in January 1972 that the farm became available for use by the then Department for Bantu Administration in Pretoria for incorporation within the post-Odendaal Commission communal area of Damaraland. Similar histories conveying the dynamism of use of this farming area in the 1950s and 1960s can be reconstructed for farms throughout the expanded Police Zone area.20

The name “Palmwag” that Farm 702 became known by refers to the tall stands of Hyphaene petersiana palms that cluster at this site of permanent water on the !Uniab River. The settler farmhouse of the 1950s and 1960s was located where the water-tanks for Palmwag Lodge are now positioned (Figure 13.5a).21 Multiple oral histories and other conversations relate that both the farmhouse and the lodge water-tanks are located at the previous site of a livestock-kraal that belonged to Simon ǁHawaxab. In the 1940s and 1950s, Simon was the headman of Sesfontein/!Nani-|aus, a major settlement and native reserve area dating back to German colonial times (see Chapter 1),

situated close to the Hoanib River to the north of the new commercial farming area.

This site that became known as “Palmwag” has an older local name that also invokes the palms at this place. This name is !Gao-!Unias: !Gao means “cut”, and !unias references the name !unis for the Hyphaene petersiana palms standing at this site. This name refers to how the river cuts through the landscape here, and to how the palm trees—!unis—grow prominently in this cut (as can be seen in Figure 13.5a). It is common in this north-western area for a watercourse to be named after a permanent source of water—such as a spring—positioned upstream in the watercourse. Following this principle, it is the presence of the palm—!unis—at sites of permanent water upstream that gives the name !Uniab to this major river that is now a central feature of the Palmwag Concession. In the past people moved up and down this river, as far as the ocean where !nara (Acanthosicyos horridus) melons could be harvested (see Figure 13.5b), as well as between this river and the Hoanib and !Uǂgab rivers to the north and the south (as documented in Chapter 12).

!Gao-!Unias, the place of palms on this river that became the site of a commercial farmhouse and then a high-end tourism lodge, was thus also a place where people lived in the past, utilising its permanent water to support their livestock herding. Referring to !Gao-!Unias as a place amongst those remembered as part of wider dwelling and mobility practices, Ruben Sanib, an elderly man who lived in Sesfontein and whose testimony I will draw on extensively in Section 13.3, relates that,

[m]y name is Sauneib !Nagu. I grew up with my father and mother in Hurubes [referring to the northern mountainous area of the Palmwag Concession]. My family name is |Awise, and we are ǁKhao-a Dama.22 […] I was born at Xom-ti-ǁgaus. My parents were living in the places called Urubao, Tsauguǁgams, Kō, ǂHāǁgams, |Gui-|naran, Barangan, Tsaun, |Nobaran, Soaun, Palm, !Uniab, !Gao-!Unian, Kai-as. These are the places where the old people lived in the past, before they were told no! They must move to Sesfontein and leave Hurubes behind.23

The commercial farming area expansion shown in Figure 13.4, combined with the desire to claim the area north of the new Police Zone boundary as a wildlife area, removed a large tract of land from local use between the Hoanib and !Uǂgab Rivers. It effected the movement of Damara/ǂNūkhoen northwards to Sesfontein and other settlements in the vicinity of the Hoanib River, and southwards towards Okombahe/!Aǂgommes on the !Uǂgab. Speaking of the movement of ‘Damaras’ to ‘Sessfontein’ from ‘Southern Kaokoveld’, in 1952 an Agricultural Officer writes: ‘[t]hese Damaras, comprising 9 men, 12 women, and 22 children with 3 families still to come, are at present at Sessfontein and would seem to be virtually destitute’.24 The late Ben Fuller, who carried out PhD research in Sesfontein and Otjimbingwe/Âtsas, also notes that in the 1950s there was an ‘influx [to Sesfontein] of outlying residents’ termed ‘Namidaman’, during the time of the leadership of chief Simon ǁHawaxab.25 Similarly, in 1951 ‘Bergdama’ are reported to have moved from ‘southern Kaokoveld’ to the Okombahe Reserve.26

Fig. 13.5 The image above shows the former dwelling place of !Gao-!Unias, now Palmwag Lodge, the location of headman Simon ǁHawaxab’s livestock kraal in the 1950s, and the present-day lodge water-tanks; the image below shows the landscape of the !Uniab River, now a prominent part of the Palmwag Tourism Concession, showing !Gao-!Unias/Palmwag Lodge upstream, and the location of !nara (Acanthosicyos horridus) melon plants downstream. Prepared by Sian Sullivan, including data from Landsat / CopernicusData SIO, NOAA, U.S. Navy, NGA, GEBCO, Imagery starting from 10.4.2013. © Etosha-Kunene Histories, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

The land claimed for settler farmers, and the area to its north claimed as a ‘livestock-free zone’, was previously lived in, utilised and moved through by people who were then constrained to “native reserve” areas either to the north or south of the new commercial farmland: namely the Sesfontein and Okombahe reserves respectively. The expansion of settler farming in this area thus had a dramatic impact on local land-use and mobilities. This situation was already the case prior to the south-west expansion of Game Reserve No. 2 in 1958 and the westwards extension of Etosha Game Park in 1962 (as documented in Chapter 2). The progressive displacement of people from this area clearly made it easier to create these new conservation demarcations. In Section 13.3 I consider in more detail the impacts these disruptive events had on people who previously lived in and accessed the area that became the Palmwag Concession.

13.3 ‘This land was ǂNūkhoe land’:27 Indigenous histories of the Palmwag Concession area, pre-1950s

Fig. 13.6 Some key former dwelling places positioned within and near to the Palmwag Tourism Concession, in between the Skeleton Coast and Etosha National Parks. The black place-markers indicate former (and current) living places; the red dots crossing the !Uniab mark the cutline at the western edge of the 1950s commercial farming area; the red boundary lines mark the borders of communal area conservancies, and the fainter red line marks the current veterinary fence. Prepared by Sian Sullivan, including Google Maps data © TerraMetrics 2022, © Etosha-Kunene Histories, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

The 1950s Police Zone expansion caused a split in a large land area known as ‘Hurubes’ or ǁHurubes, which now sits mostly within the Palmwag Concession: ǂKhari (‘small’) Hurubes is in the north, and !Nau (‘fat’) Hurubes is in the south (see Figure 12.17). People were reportedly pressed to decide between moving to the Sesfontein or Okombahe Reserves (as noted in Section 13.2):28

it’s the government who told the people to move. That’s why some Dâureb Dama people moved to !Uǂgab and some Dâureb Damas moved to Sesfontein.29

Previously they had moved regularly between multiple dwelling places and springs in these northern and southern areas (see Figure 13.6), in the course of livestock herding, aggregating to share gathered foods from different areas, and participating in praise song ceremonies and healing dances (as documented in Video 13.1 linked below).

Land (!hūs) and lineage (!haos) groupings of Damara/ǂNūkhoe and ǁUbun families were at this time living throughout the area. As discussed in Chapter 12, for the area of the present-day Palmwag Concession, these land-lineage groupings, broadly-speaking, were as follows: ǁKhao-a Dama were connected with ǂKhari Hurubes (north of the !Uniab); Aogubus-Dama resided in Aogubus—the mountainous area crossing the present-day boundary between the Palmwag and Etendeka concessions; Dâure-Dama were associated with !Nau Hurubes (south of the !Uniab); and ǁUbun resided in the Northern Namib area, but also moved inland and utilised resources of the !Uniab and Hoanib rivers (see Figure 12.17). People moved throughout the area, crossing into these different lands and connecting with others. The permanent freshwater spring of Kai-as in the heart of the present-day Palmwag Concession (see Figures 13.6 and 13.7) was a particularly well-remembered place of dwelling and aggregation for ǁKhao-a Dama and ǁUbun. As Ruben Sanib recalls:

[a]t that time we would go to Kai-as and ǁUbu people would meet us there from !Uniab and we would play together |gais [praise songs] and arus [healing songs]. And from there, ǁUbun would go back again to !Uniab for the !naras and ǁKhao-a Dama came back again to their area [ǂKhari Hurubes] to find the seeds, bosû (Monsonia umbellata) and sâun (Stipagrostis spp.).30

A |gais song, broadly speaking, is a song sung to praise something. |Gais are sung to celebrate entities, people and events that are of value. As Jacobus ǁHoëb, leader of the Hoanib Cultural Group in Sesfontein—known locally as the ‘king of the |gais’—describes,

[m]y grand-parents taught me to play the |gais. The springbok are playing. The zebra are playing, the gemsbok are playing. All the animals are playing when the rain falls. And the people say, “how can we make something to praise the animals?”31

Fig. 13.7 The former Kai-as settlement in the Palmwag Concession. Information from multiple visits and discussion with especially Franz |Haen ǁHoëb, Noag Mûgagara Ganaseb, Ruben !Nagu Sanib, Sophia Opi |Awises and Filemon |Nuab. Prepared by Sian Sullivan, with Google Maps imagery 2023, © Future Pasts, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Arus are sung more specifically to support individual and social healing, and especially to support the strength and insights of healers. In this cultural context, a name for a healer is |nanu-aos or |nanu-aob—meaning literally a woman or man who has been called by the rain (|nanus) and ‘has the rain spirit’.

Video 13.1. The Music Returns to Kai-as. 53 minute version here https://vimeo.com/486865709; 30 minute version here: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/6bf387e8, © Future Pasts, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

People would especially congregate at Kai-as to play these musics after the rains had started. It was a key place on routes between the localities of important food resources. For example, ǁUbun would move between !nara (Acanthosicyos horridus) melon patches in the !Uniab and Hoanib river mouths, via springs at Kai-as and Hûnkab (to the north-west of Kai-as) (as documented in Chapter 12).

The film The Music Returns to Kai-as32 (Video 13.1) documents a process of returning to Kai-as with the Hoanib Cultural Group of Sesfontein, whose elders are and were those who remember accessing these wider areas beyond the places where they are now constrained to live, to play once again these musics at this key place of cultural heritage.

Ruben Sanib further remembers how different groupings of people would move through and meet each other in the area of the Palmwag Concession, known as Hurubes and, in the west, as Namib (see Video 13.2). As he describes:

I sit here at !Hubu spring and I am reminded of all the places where the old people [kai khoen] lived. People lived a lot in this land, and we met with Dâure-dama people and we exchanged things with them. ǁKhao-a Dama met with the people from the ocean [Hurib] side [ǁUbun] and at Kai-as, and we collected [ôau] food [xaira]: bosû, sâub, danib [honey]. And we danced |gaib and arub and we sing he he, hue hue, urr urr!, and suck [xoma] the sicknesses from each other. And it’s here when the elders joined with red women [ǁUbun] and the red men joined with ǂNūkhoe women […] and Dâure-dama men joined with Hoani-dama women, and Aogu-dama women and Aogu-dama men joined with Hoani-daman and Dâure-daman. It is how we lived in this land. 33

Video 13.2. Lands That History Forgot: 2nd Journey, Palmwag Tourism Concession / Hurubes—Ruben !Nagu Sanib, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/6f86e31f, © Future Pasts and Etosha-Kunene Histories, 2024, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

The 1950s disruption of access to, and dwelling in, this western area also constituted a repetition of prior evictions from ‘Southern Kaokoveld’. The Annual Report of the SWAA for 1930 thus emphasises the establishment of a ‘buffer zone between the natives in the Kaokoveld and the occupied parts of the Territory’, ostensibly to control the transmission of lungsickness (bovine pleuropneumonia) from the former to the latter34 (also see Chapters 2 and 14). The late Ben Fuller reports that the first lungsickness inoculation programme in the north-west beyond Kamanjab was undertaken by the State Veterinary Office in 1930. It destroyed approximately 18 animals as well as vaccinating 6,514 cattle, and recommended that cattle from Kaokoveld ‘be prevented from moving into the white farming area’, with ‘regular monitoring of waterholes along the 19th parallel by the police […] [considered] sufficient to prevent the spread of the disease southward’.35

These historical accounts seem connected with oral histories telling of Damara/ǂNūkhoe experiences of evictions from the northern part of the present-day Palmwag Concession. Near to the former dwelling place Gomaxora (‘where the cattle dig’—see Figure 13.6), Ruben Sanib thus described a dramatic experience of eviction that took place prior to the death of a Nama headman of Sesfontein called Nathaniel Husa |Uixamab, who died after being mauled by a lion at the place ǂAo-daos in 1941:36

[w]e were living at |Gui-gomabi-!gaus [west of Gomaxora]. While we were there we were ordered to move the cattle from this land to !Nani-|aus [Sesfontein] area. Some people were living here with their cattle, and my grand-father was at |Gui-gomabi-!gaus with his cattle. When the authorities took the cattle to Gomaxora to be shot, the men in my family took their bull and killed him at the spring near here [so that the authorities could not shoot the bull]. When the bull was killed, they named the place |Gui-gomabi-!gaus [the cave of that one bull].

When we were living here my grand-mother |Uidige died [Ruben’s father’s mother] and we buried her here and moved on to !Nani-|aus. The men living here with their livestock were !Kharuxab, Gaoeb, Ada-ǂkharib, Honab and Ganu-ǂkharib. They were living here with their wives […] The government does not want us to stay in this area with our cattle, and they came and shot the cattle at Gomaxora. And the men do not want the bull to be shot, so they shot the bull with a bow and arrow and ate the meat there at the place they named |Gui-gomabi-!gaus. […] It was Gamab with Honab, Titab [Ruben’s father Sanib] and !Kharuxab [the father of the late Andreas !Kharuxab, headman of Kowareb in the 1990s, interviewed below]. […] The government [ǂhanub] first said take the cattle [goman] out, but you can stay here with goats [birin] only. But some of the cattle remained in the area and the government came and shot those cattle. This land was ǂNūkhoe land. But Herero wanted to move here. They were told to move out and ǂNūkhoe were then also told to move out with their cattle and goats.37

In an earlier interview, Ruben affirmed that this displacement was because:

[t]he government said this is now a wildlife area and you cannot move in here. We had to move to the other side of the mountains—to Tsabididi [the area also known today as Mbakondja]. Government police from Kamanjab and Fransfontein told the people to move from here.38

In 1999 Andreas !Kharuxab also reported that,

[m]y grandfathers planted tobacco. And with that tobacco they bought cattle from the Herero who were living in the district of Kante [Kamdesa, towards Kamanjab]. And then they started farming with those cattle, but the government said that you can’t farm cattle in this area. And then they shot the cattle.39

The 1950s commercial farmland expansion clearly took no account of prior mobilities between named dwelling places, such as those shown in Figure 13.6. To provide one example of the reality of these mobilities, several of the places named on Figure 13.6 were mentioned by the late Andreas !Kharuxab, former Headman of Kowareb settlement on the Hoanib River (Figure 13.8):

[t]here are many places whose names I haven’t said yet. There is |Nowarab, !Hubub, !Gauta, ǂGâob, ǂKhabaga and !Garoab. And there are more places where people lived in that area. !Hagos, Pos and Kai-as were the places where people were living. The people travelled like that (between these places).40

Ruben Sanib’s testimony above mentions the father of Andreas as being amongst those whose cattle were shot by the authorities, and it is clear that Andreas learned about places in the wider landscape from his fore-fathers.

Fig. 13.8 The late Andreas !Kharuxab, former headman of Kowareb, pictured in 1999 and with his family in 1992. Photos: © Sian Sullivan, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Some documented evidence also exists for these prior mobilities from south of the Palmwag Concession, through the present-day concession area, to places beyond its present-day northern boundary. For example, when a settler farmer called David Levin applied for grazing around the spring |Ui-ǁaes—which became known as Twyfelfontein—his neighbour Andries Blaauw of Blaauport Farm mentioned to him that ‘a Damara family lived there with some of their animals’.41 Levin learned that this family moved between |Ui-ǁaes close to the Aba-ǁHuab River, De Riet on the ǁHuab River, springs described as with palm trees in the Grootberg area (i.e. !Gao-!Unias and associated springs), and Kowareb on the Hoanib River.

The following testimonies document further the presence of families inhabiting the area now set aside as the Palmwag Concession. Ruben Sanib relates that,

[n]ow !Abudoeb and his family moved from Soaub to !Nani-|aus [Sesfontein], and Komsi and the other people moved to !Uǂgab. When the people moved to the south and the north the white people moved into the area.42

Ruben and his family were with !Abudoeb at Soaub at the time, having travelled there to attend the burial of Ruben’s grand-father Aukhoeb Ganuseb (see Figure 13.9). Soaub was a living place that was cleared in order that it could become part of Farm 710, known as Rooiplatz, now the site of the high-end tourism facility Desert Rhino Camp, run by Wilderness Safaris. Ruben recalled that when the government told them to move they travelled first to !Uniab (where the Palmwag fuel station is now). His parents were herding goats there with Andreas !Kharuxab and family. They then moved north to !Garoas, to |Gui-gomabi-!gaus, and on to Sesfontein (see Figure 13.6).43 From Ruben’s perspective, it was the new Damara Regional Authority (DRA) after the Odendaal Commission that said,

why are you [the settler farmers] moving in when you told the [ǂNūkhoe] people to move out? You have to go back so that the people can stay at their places. Then, when they told the white people to move out [after the Odendaal Commission in the early 1970s] then the [ǂNūkhoe people moved to those farms. From Khorixas to Sesfontein on the main road they are living there, like Palm, Palm-pos, Palmwag, !Naodais, Gomagu!gaub, Otjihavarero like that. And from Jakkelsvlei, Middle-pos, Swartwater, Swartwater-pos, Bergsig, Bergsig-pos, Driefontein, Tsaurobfontein—those are the places where the Damara people are living.44

At the same time, it was understood that the government of the time did not want people to move back into the western area of Hurubes that had been emptied through previous evictions of people and their livestock (see Section 13.5); even though reportedly people would have moved back if they had been permitted to do so.45

Fig. 13.9 Ruben Sanib sits at the grave of his grand-father Markus Aukhoeb Ganuseb at the former living place Soaub in the Palmwag Concession. Photo: © Sian Sullivan, 15.5.2019, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

The 1950s evictions acted to concentrate people in Sesfontein on the Hoanib River, as well as in Okombahe on the Ugab [!Uǂgab]. I will focus here on the ‘Zessfontein Reserve’, a large circular area around the settlement of Sesfontein, established under the German colonial regime for especially Nama and Damara/ǂNūkhoe inhabitants, in acknowledgement of their histories in this area46 (also see Chapters 1 and 12). Indeed, the place ‘Zessfontein’ and ‘the grazing land belonging to it’ was specifically reserved for the people of Sesfontein in 1885 by Nama captain Jan |Uixamab, when negotiating German commercial prospecting interests in mineral resources in north-west Namibia.47 In 1921, the incoming South African administration confirmed that this reserve consisting of 31,416 ha for ‘Topnaar and Swartbooi Hottentotten’ was ‘to remain undisturbed’.48 It should be noted, however, that the circular area of this ‘reserve’ (visible on Figure 13.4) did not reflect the broader area utilised and known by inhabitants of this area. Indeed, in the SWAA Annual Report of 1939 it was acknowledged that together with the native reserve areas of the northern Kaokoveld, the Zesfontein reserve was ‘much too small’, and ‘a number of the Zesfontein Natives are now living on Crown land’, i.e. beyond the reserve enclave.49

The distress caused by the 1950s (and prior) evictions from this wider area of so-called ‘Crown land’ was clearly articulated to a United Nations Special Committee for South West Africa meeting in Sesfontein in May 1962, in which the loss of land and grazing was high on the agenda of residents’ concerns. Present at this meeting were Mr. Simon Hawahab [ǁHawaxab], ‘Headman of the Topnaar Nama residents’ (36 to 40 persons), Mr Elias Amgab ‘Headman of the Damaras’ (200 to 300 living in the Reserve), and ‘Herero Headman’ Urimunge Kasaona,50 as well as around 100 residents. They stated that,

the people of Sessfontein used to be able to graze their livestock south of the Hoanib River. However, European farmers had taken the land […], and were occupying most of the grazing veld which had been formerly used by the people of Sessfontein. Moreover, the farmers did not want the people of Sessfontein to travel through the land now occupied by the Europeans.51

On top of this rather orchestrated collapse of Indigenous subsistence economies that relied on access to and through this large tract of land, a further dimension of loss is keenly felt by elderly residents of the Hoanib Valley area: namely their inability to access the graves of members of their families buried here. Figure 13.10 shows the mapped locations of some of the graves known to be present in and near to the Palmwag Concession. Many of these graves are of named family members, remembered by those alive today.

Fig. 13.10 The crosses on this map show the locations of graves of known ancestors in and near to the Palmwag Concession, many of which are of known and named ancestors. Author’s research data, including Google Maps data © TerraMetrics 2022, © Future Pasts, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

13.4 Conservation visions: Imagining, creating and lamenting an ‘Arid Eden’

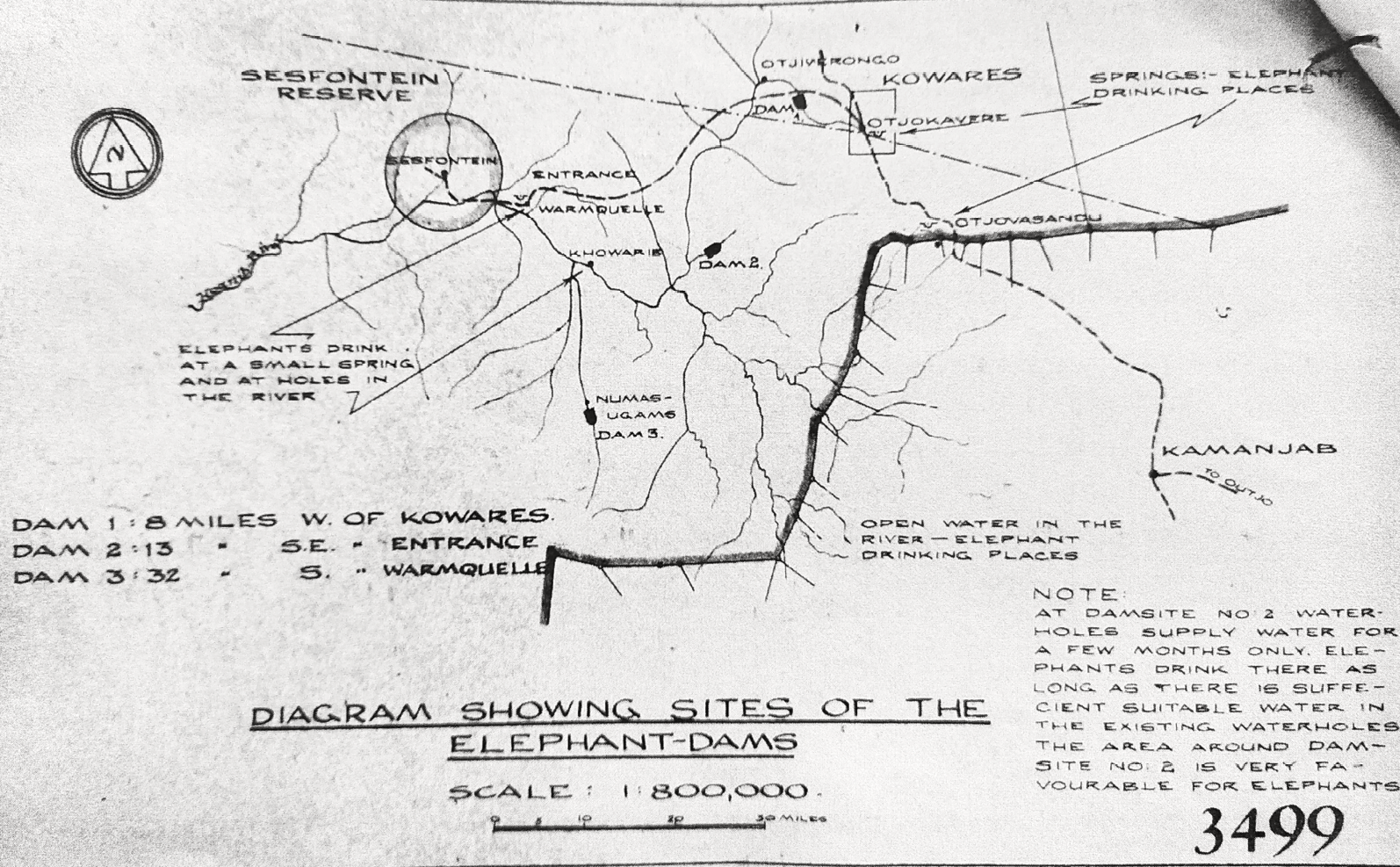

The 1950s clearance of people from areas within and north-west of the newly expanded commercial farming area paved the way for new ideas regarding wildlife conservation in the area. Already in 1957, new water supplies for elephant were being developed north of the newly positioned Red Line in the triangle between Kowares (now often referred to as Otjokowares, in Ehi-Rovipuka Conservancy), Warmquelle and Grootberg:52 Figure 13.11 thus shows the proposed locations of water supplies for elephant with Dam sites 1 and 2 preferred because site 3 was considered to not be in a ‘typical Elephant area’ (although see Chapter 11).53 These developments were a response to complaints by the new settler farmers in the expanded commercial farming area that ‘[e]lephants were damaging their fences, water-supplies, etc.’.54 The government’s reaction was to propose new or expanded dams north of the new settler farming area to which elephants would be attracted. These plans were put in place even though these areas were in localities lived in by local people whose dwelling and mobility possibilities had been highly restricted through expansion of these same farming areas.55

Fig. 13.11 Map showing proposed ‘elephant-dams’ north of the new commercial farming area, marked by the thick black line. Source: © NAN SWAA WAT.74.W.W.71/4 Game Reserve: Kaokoveld Game Reserve. Triangle—Kowares-Warmquelle-Grootberg. Dams for elephants in the Kaokoveld Game Reserve. To the Director of Water Affairs 28.8.1958, used with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Simultaneously, new ideas regarding the creation of a south-western extension of Game Reserve No. 2 were emerging in these years, as documented in detail in Chapter 2.

In 1956, recommendations were made by ‘the Parks Board of South West’ for ‘an additional nature reserve between the Hoab [sic, ǁHuab] and the Hoanib rivers’.56 Also in this year it was confirmed that elephant and rhinos were considered well protected in ‘the area between the present red line and the Native Area in the North’, but that the area should be ‘declared as an extension of the Etosha game park’ and any shooting of animals there should be prohibited57—a rather ironic statement given that two decades later the area was designated as a commercial hunting concession. Nonetheless, respecting the long-established native reserve boundaries where several thousand people lived, the Chief Native Commissioner was clearly not in favour of ‘any further portions of the Kaokoveld Native Reserve or the Sesfontein Native Reserve being included in the Game Reserve’.58 Arguably, then, the south-westwards extension of Game Reserve No. 2 in 1958, and the later Etosha Game Park extension to the west in 1962 (see Chapter 2, Figures 2.2 and 2.3) did not have much additional effect on the people of Hurubes from the Hoanib to the Ugab Rivers, because they had already been iteratively cleared from the landscape. It consolidated rather than created their severance from the resources and living sites of this area, as documented in Section 13.3.

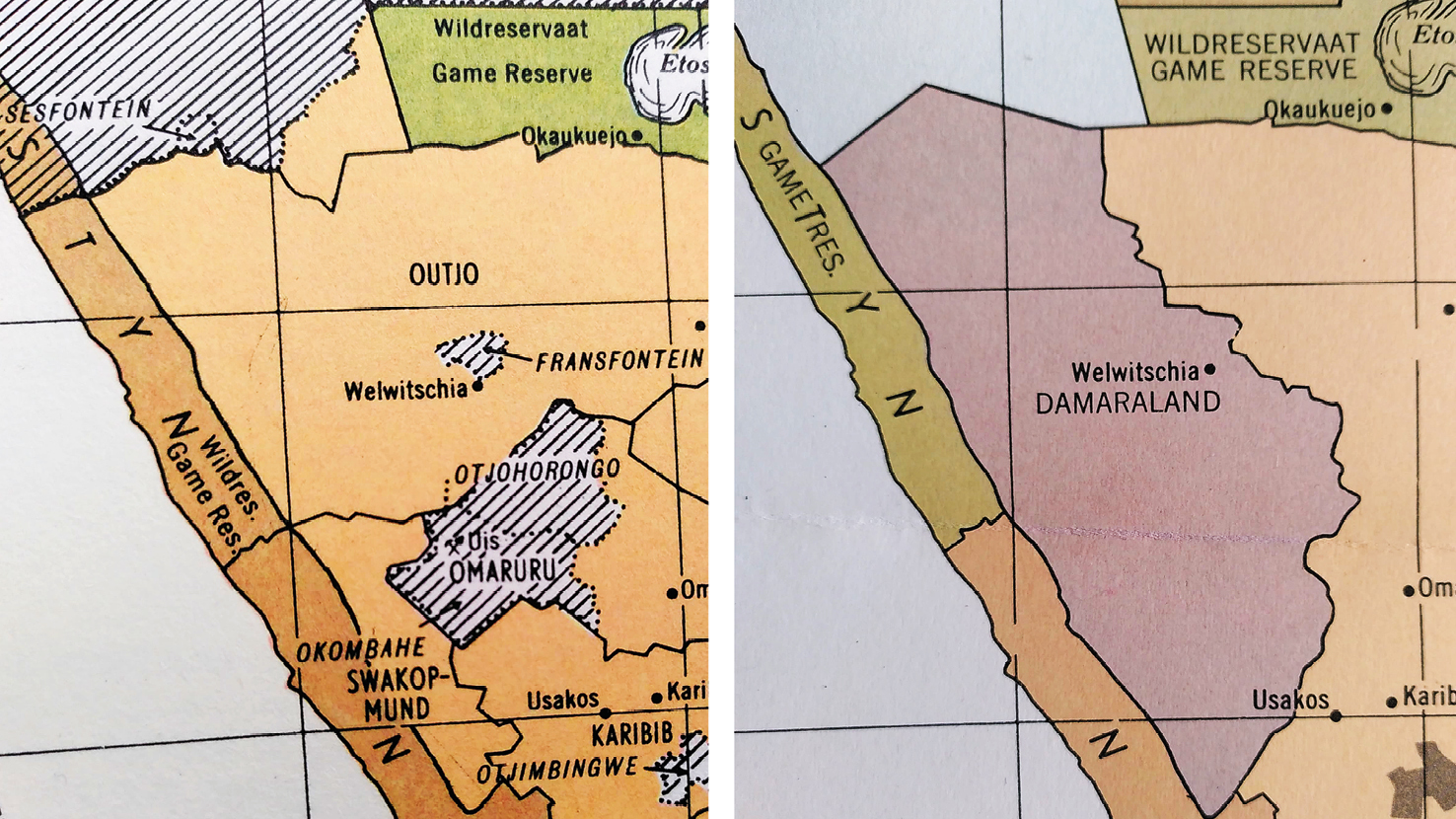

The extended game reserve and game park areas of 1958 and 1962, however, were destined to be very short-lived. In 1964, the published report of South West Africa’s Commission of Enquiry into South West African Affairs (the ‘Odendaal Report’) proposed to reconnect the fragmented Native Reserves of Sesfontein, Fransfontein, Okombahe and Otjohorongo (Figure 13.12). This proposal in part reflected prior mobilities and uses of land between these reserve areas that had been disrupted due to the expansion of the settler farming area, documented in Sections 13.2 and 13.3.

Fig. 13.12 The map on the left, shows the existing ‘native reserves’ in west Namibia, namely Sesfontein, Fransfontein, Otjohorongo and Okombahe, that were to be joined into a single ‘homeland’ called ‘Damaraland’ as shown in the map on the right, thereby also including the known places between the Hoanib and Ugab rivers shown in Figure 13.6. Source: adapted from Figures 9 and 27 of the Odendaal Report (1964), out of copyright, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

For conservation and ecology professionals, many of whom had only become familiar with the landscapes of north-west Namibia from around the late 1960s, these Odendaal recommendations constituted an existential crisis. As Hall-Martin and co-authors write, ‘[c]onservationists saw the deproclamation of much of Etosha as a tragedy’.59 This sense of crisis is represented well in the statement by de la Bat that,

[a]fter Odendaal Etosha resembled a plucked fowl. 17972 square kilometres had to be sacrificed to the land needs of Owambo, Kaokoland and Damaraland.60

Similarly emotive language is repeated in multiple other statements, such as this one from Mitch Reardon’s 1986 book The Besieged Desert declaring that the Odendaal changes would effect a ‘dismembering of the world’s largest conservation area’.61 Writing of the Kaokoveld as ‘southern Africa’s last wilderness’, Owen-Smith similarly asserts that:

[b]efore its deproclamation as a game reserve by the Odendaal Commission in the sixties, the whole Kaokoveld supported a rich and varied spectrum of big game animals.62

This statement is made without mentioning that Kaokoveld was simultaneously a formally declared “native reserve” area prior to this Odendaal moment (as detailed in Chapter 2). This series of dramatic assertions were made even though by the time of implementation of the Odendaal Plans in around 1970, the south-western extension of Game Reserve No. 2, and the western extension of Etosha Game Park, had existed for only 12 years and eight years respectively. Additionally, few personnel or infrastructural developments were in place during these years to make this south-western extension a strong “Protected Area” reality.

The impression given is that a longstanding protected wilderness area was to be both cut up, and more-or-less invaded, by resettled Africans with little prior claim to or experience of the area. From the late 1960s there was also a rush to translocate into Etosha valuable animals such as black rhino from settler farms bought up for Damaraland—the assumption being that resettled African farmers would damage the wildlife remaining in the reallocated farm areas: from the late 1960s to early 1970s several dozen of these animals were translocated to the area that became ENP.63

Four alternative conservation proposals were tabled for this western area in this moment. Three of these proposals have been thoroughly reviewed by Michael Bollig in his monograph Shaping the African Savannah.64 I want to take another close look at these proposals, however, for their specific implications for the peoples who had previously accessed the area between the Hoanib and Ugab Rivers.

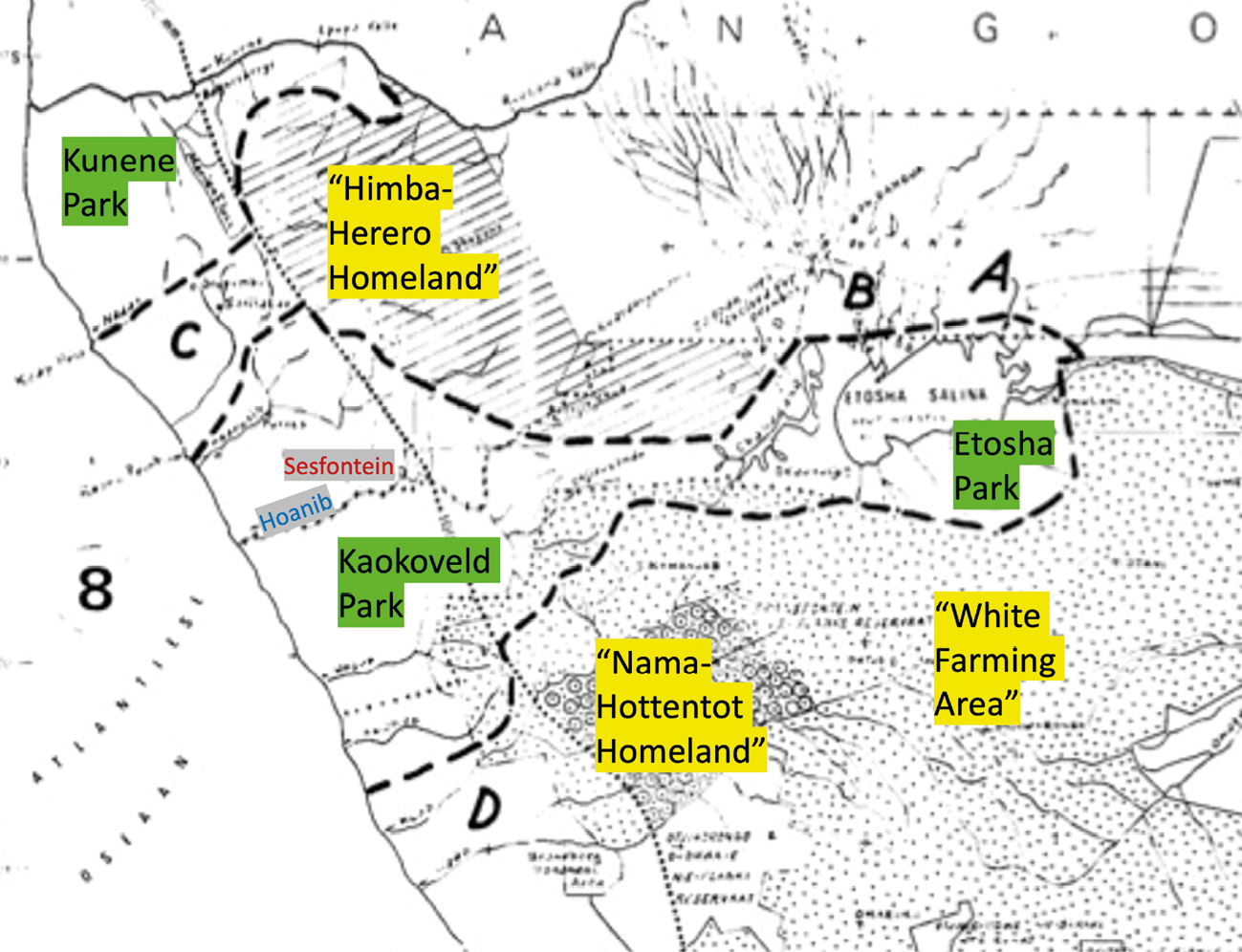

Etosha ecologist Ken Tinley’s proposal, commissioned by the Wildlife Society of South Africa and submitted by them to the Office of the Prime Minister in 1969, was published in the journal African Wildlife in 1971.65 It aimed ‘for a division of land between man and wildlife’,66 and involved creating a ‘Kunene Park’ in the far north-west, and a ‘Kaokoveld Park’ that would create a wildlife corridor to ENP (Figure 13.13). Tinley recommended that the peoples of the Hoanib river valley settlements, including Sesfontein, should be removed to a so-called ‘Nama Homeland’ around the Fransfontein Reserve (included by the South African administration as a ‘First Schedule’ native reserve in 1923): thus, ‘[t]he Nama people at Sesfontein and in the adjacent country should be moved to the same homeland area as the Fransfontein people’.67 Much of the expanded white settler farming area would remain. To justify this proposal, he writes that:

the Nama people at Sesfontein and Warmquella, the extinct Strandlopers, and the Heiqum “Bushmen” are all of […] Nama stock and share the same language. One homeland should suffice, as they are a single language group.68

Three things are noticeable in these statements. First is the recommendation for a wholesale removal of all Khoekhoegowab-speaking inhabitants of the wider north-west area to a small reserve area around Fransfontein. In this recommendation all the diverse historical connections these language speakers have with the Hoanib valley area are completely disregarded. Second is the mention of a ‘Strandloper’ (i.e. coastal) population deemed to be ‘extinct today except for one or two very old individuals living in Sesfontein’.69 Discussion with inhabitants of Sesfontein and its wider area would have shown both that so-called ‘strandlopers’ and their descendants continued to exist in the area, although finding it increasingly difficult to access coastal areas; and that their livelihoods did not rely on ‘strandloping’ only, but on complex mobilities between coastal and inland areas, food sharing with Damara/ǂNūkhoe groupings also living and moving through the area, and techniques of food storage (as documented in Chapter 12).70 Third is the complete absence of any mention of Damara/ǂNūkhoe inhabitants of the area. This is strange because in these decades they are consistently recorded to be the largest population group of the area, as confirmed in the following statistics from surveys in Sesfontein in 1947–1948 and 1991 (Table 13.1).71 This perplexing rhetorical “disappearing” of Damara/ǂNūkhoe and their histories of association with north-west Namibia lingers in multiple texts written about this area, as discussed in Section 13.5.

Fig. 13.13 Edited sketch-map of ecologist Ken Tinley’s 1971 proposals for creation of a Kunene Park and Kaokoveld Park in north-west Namibia (the latter connected with Etosha Park in the east), from which inhabitants should be removed to a ‘Himba-Herero Homeland’ and a ‘Nama Hottentot Homeland’, whilst retaining much of the surrounding ‘white farming area’. Source: adapted from Tinley (1971: 10, public domain article at http://the-eis.com/elibrary/search/17211), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Table 13.1. Population figures for Sesfontein in 1947–1948 and 1991.

|

Population grouping |

||

|

1947/48 |

1991 |

|

|

576 |

±480 |

|

|

396 |

±200 |

|

|

‘other’ |

243 |

±126 |

|

Total |

1,336 |

±806 |

Sources: 1947–1948 figures from van Warmelo (1962[1951]: 40); 1991 figures from National Planning Commission (1991).

In 1971, the late Garth Owen-Smith also writes a report entitled ‘The Kaokoveld: An Ecological Base for Future Development Planning’, a shorter version of which was published in the South African Journal of Science in 1972. Contrary to Tinley,72 Owen-Smith states that,

[d]uring two and a half year’s residence in the Kaokoveld, no signs were found of any large scale migration of game to and from the Etosha saline area [with instead] […] a rather local seasonal cycle, with the water dependent animals, such as elephant, zebra and kudu, concentrating in the vicinity of permanent waterholes during the dry months.73

He thus asserted that ‘there is insufficient evidence for a corridor across valuable ranchland to link these two regions’ [i.e. Etosha Game Park and the western Kaokoveld].74

Invoking the United States’ Wilderness Act of 1964, Owen-Smith argued that,

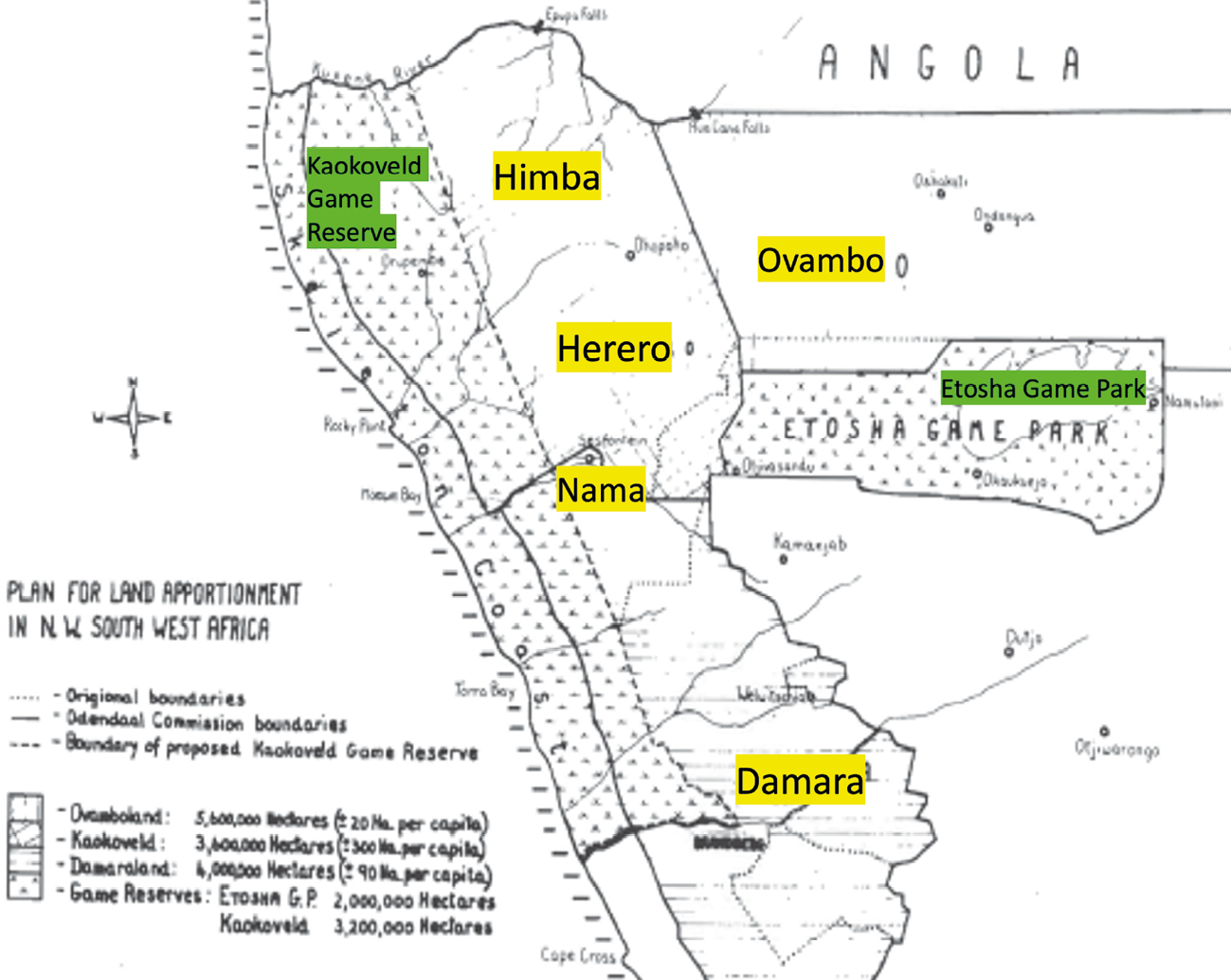

a game reserve in the western Kaokoveld has vast potentials as a tourist attraction, and in time this potential can be turned into an economic asset to the country as a whole and particularly to the people of the neighbouring homelands […] As the situation in the western areas of the new Damara Homeland is essentially similar to that in the Kaokoveld, it should be possible to extend a game reserve southward along the semi-desert to the Ugab river, thus linking it with the existing Brandberg Nature Reserve.75

Fig. 13.14 ‘Plan for land apportionment in N.W. South West Africa’. Source: adjusted from sketch map in Owen-Smith (1972b: 35, public domain article at https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA00382353_9803), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Specifically, he proposed the creation of a large ‘Kaokoveld Game Reserve’ in the west of what is now Kunene Region (Figure 13.14). Whilst somewhat more generous towards local people, his proposals are also framed around the idea that Damara in the north-west are reduced to ‘only a few’, and that the ‘Strandloper’ Bushman has passed from the scene:

[i]t appears likely that in the distant past, both the Bushman and […] Damara were widespread in the Kaokoveld, but within the last twenty years, the ‘Strandloper’ Bushman has passed from the scene, and only a few Damara remain, in the dusty Hoanib river valley between Warmquelle and Sesfontein.76

Framing Damara/ǂNūkhoe and ǁUbu presence in terms of an absence is damaging. The effects of this rhetorical device remain evident today, contributing to a lingering contemporary sense of bias against Khoekhoegowab-speaking peoples in conservation initiatives in this area.77

In 1974 a report commissioned by the Pretoria administration on The Natural Resources of Damaraland recommended that a Game Reserve area be established in the area north of the Grootberg to Sesfontein road to encourage tourism (Figure 13.15). The report stated:

[t]he establishment of a Game Reserve area has been recommended in the area north of the Grootberg—Sesfontein road to the Hoanib river. Here the pastoral potential is low, being confined to the sporadic use of widely dispersed valleys. A nucleus of game exists and the area could be developed to encourage localised game concentrations and to provide access to scenic attractions for tourists. This reserve could be complementary to Etosha Game Park which is singularly lacking in scenic attractions.78

Fig. 13.15 ‘Damaraland recommended land use’. The shaded area south of Sesfontein is the land proposed as a ‘Game Reserve area’. Source: Loxton et al. (1974: Figure 4, publicly shared consultancy report), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Finally, in 1974 a team led by Professor Fritz Eloff, head of zoology at Pretoria University, was appointed by the Pretoria-based administration ‘to prepare a master plan for the conservation, management and utilisation of nature reserves in Damaraland and Kaokoland’.79 Eloff’s team undertook several surveys, proposing a ‘game reserve’ that would include ‘all of the Namib, inner Namib [i.e. pro-Namib] and escarpment country west of the 150 mm rainfall isohyet’.80 The area would stretch from the Kunene to the !Uniab Rivers, and would include a corridor incorporating the settlement areas of the Hoanib and Ombonde Rivers to connect Etosha and Skeleton Coast National Parks; thereby essentially iterating the post-1962 area of Etosha Game Park, as shown in Figure 2.3, Chapter 2.81 It was advocated that all hunting should cease, including ‘pot-licenses’ for administrative staff.82

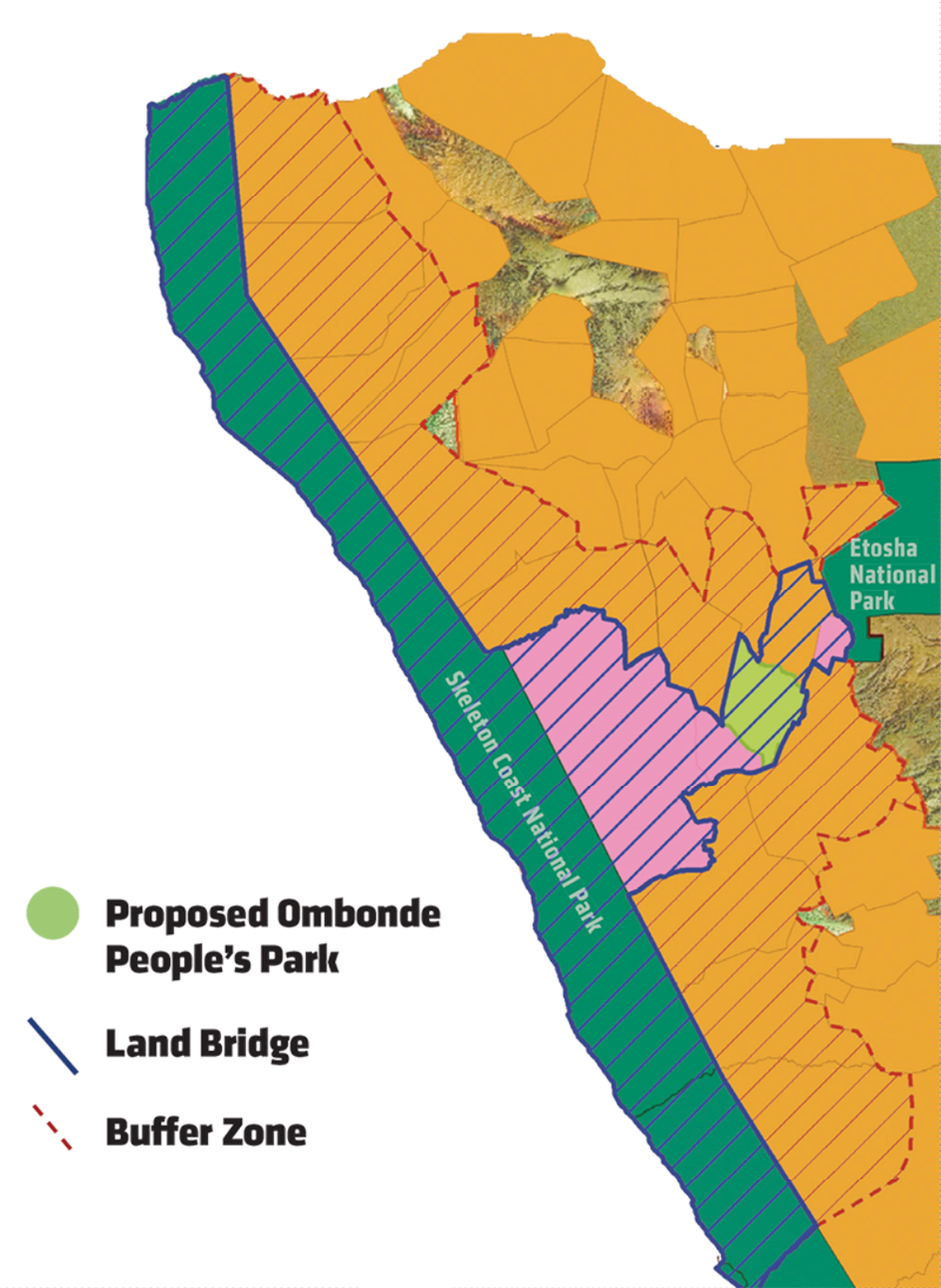

Despite Owen-Smith’s observations recounted above, this notion of a wildlife corridor connecting Etosha with the Skeleton Coast remains an oft-repeated conservation aim to this day, featuring, for example, in proposals for a Kunene People’s Park in the 2000s,83 and now in a new ‘Skeleton Coast-Etosha Conservation Bridge’ initiative (see Chapter 3). Indeed, demonstrating how conservation imaginaries of this area reverberate through the decades, it is illuminating to see how Eloff’s proposals are matched almost exactly in a recent public domain map: see Figure 13.16. Once again, the focus is a connected wildlife conservation corridor between Etosha and the Skeleton Coast, surrounded in this case by a conservation ‘buffer’ in the west stretching from the Kunene River to south of the !Uǂgab River.

Fig. 13.16 ‘Building a land bridge’. Public domain image downloaded from https://www.worldwildlife.org/magazine/issues/summer-2023/articles/moving-forward#popup1, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Returning to the 1970s, Hall-Martin and co-authors report that in the midst of Eloff’s work in north-west Namibia, South African businessman Dr Anton Rupert—founding president of the Southern African Wildlife Foundation which became the Southern African Nature Foundation (SANF) and then WWF South Africa—announced in African Wildlife magazine that a large conservation area in the north-west of South West Africa was about to be created:

[a] contiguous conservation area covering 72 000 square kilometres is being planned for the northern part of South West Africa. This allays many fears which scientists of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and the World Wildlife Fund have had, as regards the future of this important habitat. This conservation area will include the existing Etosha Game Reserve [sic. Etosha National Park] as well as the Skeleton Coast [National] Park and will be more than three times the size of the Kruger National Park and indeed one of the largest in the world.84

Reading these 1970s proposals today, it is striking how audacious they are in certain respects. First, the drawing of boundaries for the huge area of north-west Namibia, based on rather little or limited published consultation with local inhabitants for their own views, expertise and concerns, seems suggestive of “coloniality”. Second, both land and people are radically dehistoricised in these proposals: i.e. their complex histories are downplayed or removed in various ways. Third, Indigenous histories associated with land between the Hoanib-Ugab Rivers seem to be especially “disappeared”. In different ways, these 1970s reports and proposals acted to “naturalise” prior clearances of people from the landscapes of this area. In doing so, an ideological stance mobilising for the expansion of conservation space was consolidated.85

Although none of these proposals were enacted at the time, their ideas, language and suggestions clearly linger in various ways into the present. They find their way, for example, into new proposals for expanded protected areas of various kinds (as shown in Figure 13.16), and in how conservation issues in Etosha-Kunene are consistently framed around the necessity of a conservation corridor between Etosha and the Skeleton Coast.

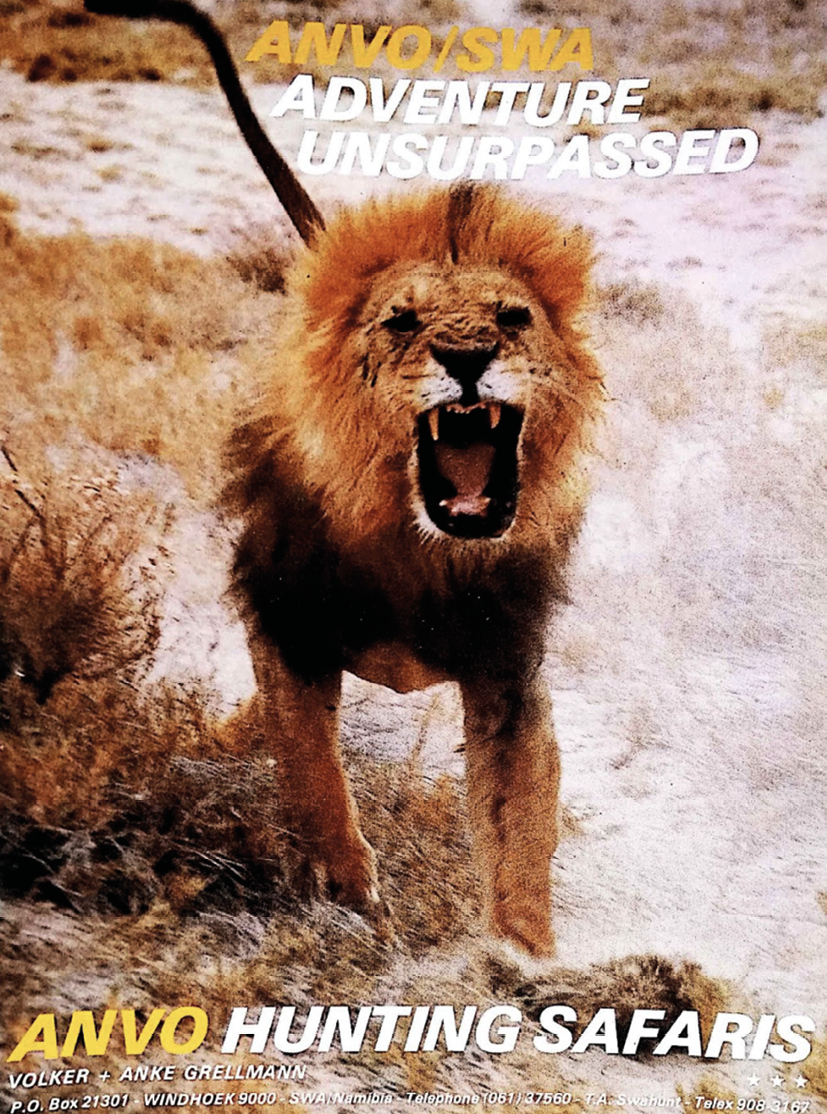

Fig. 13.17 Advert for ANVO Hunting Safaris. Source: scan from SWA Annual (1983: 22), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

What in fact happened in this 1970s moment was rather different to any of the proposals outlined above. In the late 1970s a 10-year trophy-hunting concession of 15,000 km2 was leased by the Pretoria-based Department of Bantu Administration and Development to a German-Namibian hunting business called ANVO Hunting Safaris (see Figure 13.17).86 It was led by a big-game hunter, the late Volker Grellman, described as ‘[o]ne of Namibia’s most famed hunters’ by the pro-hunting organisation Conservation Force, for which he remains listed on the Board of Advisors.87 Grellman’s hunting concession extended from the Hoanib to the Ugab rivers, the area that for a short while had been the ‘western Etosha Game Park’, later described as ‘still game-rich and largely unoccupied’.88 The hunting company’s annual quota was for two trophy elephants north of the ‘Red Line’, which by this point had moved southwards to its present location (see Figure 13.1), plus ‘problem elephants’ as they occurred anywhere in Damaraland, as well as so-called ‘common game’.89 It is in this moment that a hunting camp was created near the site of the house of the former settler farmer at Palmwag Farm, eventually to become Palmwag Lodge,90 although to Khoekhoegowab-speakers in the area it remains known and referred to as !Gao-!Unias.

In the 1970s, however, this land was simultaneously under management by the Damara Regional Authority (DRA) of the second-tier government system, based in Khorixas.91 What then follows appears to be a struggle over who has rights over this area and its wildlife, in a context of drought, war and over-hunting.92 In the late 1970s and early 1980s severe drought decimated wildlife and livestock in north-west Namibia, making indigenous fauna ‘vulnerable to subsistence hunting by the now impoverished Herero and Damara inhabitants in the region’ (exacerbated due to ‘the army’s issue of .303 rifles to several thousand Kaokoland men’93); as well as to ‘[h]unting by government officials, the SADF and other non-residents’,94 whilst larger predators increased during this time.95 Gaob Justus ǁGaroëb who headed the DRA writes of this period in very strong terms, saying:

[…] the colonial Government inaugurated their lackeys who, among others, made a mockery of our conservation efforts by simply granting Trophy Hunting Rights to Anvo hunting Safaris. This Safari Hunting became an embarrassment, worldwide because of their indiscriminate killing of […] specifically elephants in their trophy-hunting spree.96

Following the 1979–1982 drought, the Department of Nature Conservation (DNC) reportedly started negotiations with the Damara Executive Committee (DEC) of the DRA, led by Justus ǁGaroëb, and including Simpson Tjongarero (Education), Johannes Hendriks (Agriculture), and Volker Grellman of ANVO Safaris. As Owen-Smith reports, the aim was to re-proclaim ‘the trophy hunting concession area in northern Damaraland’, with ‘an income sharing and joint management plan for the area’ also worked out.97 Due to low animal numbers and reduced hunting quotas, however, Grellman instead agreed ‘to give up his concession if he was paid out for its remaining five years, as well as for his hunting camp at Palmwag’.98 The DNC did not have the R63,000 needed for this buy-out, but the then SANF stepped in with a grant agreed ‘on the condition that the DNC could guarantee that the area would be proclaimed’,99 presumably along the lines of the Anton Rupert supported Eloff plan mentioned above.

Assuming agreement from the DRA would be a ‘formality’, rather than realising that the DRA needed to be negotiated with as a legitimate and independent authority with powers of decision over territory in the homeland, the SANF paid ANVO in mid-1983 and Anton Rupert announced (once again)—this time on South African television—that ‘the old (pre-1970) Etosha would soon be re-proclaimed’, followed by a similar announcement by DNC officials on SWA television.100 Former Administrator-General W. van Niekerk reportedly proposed to the DRA ‘that a section of northern Damaraland, totaling about 1,2 million hectares, be proclaimed as a nature conservation area’, but that ‘the area would remain the property of the Damara people’ albeit ‘managed as a nature conservation area’.101 No ‘prior consultation with the affected inhabitants of the region had been undertaken’, however, and Justus ǁGaroëb, as Chairman of the DEC, pointed out that ‘the people would turn against them’ since the land was considered traditional land (as documented in Section 13.3).102

Indeed, the DRA and its DEC were unimpressed at having this large area of land allocated to the Damaraland Homeland pulled from underneath them without replacement. The promise by DNC of 25% of revenues from entry into the concession was also a far cry from earlier promises of joint management of the area.103 Early in 1984 the DNC announced that talks regarding the re-proclamation of ‘western Etosha’ had broken down and were asked by SANF to return the money paid in 1983 to Grellman.104 ǁGaroëb is reported to have written in newspapers in 1984 that:

DNC’s proposal for a large national park will compromise 2/3 of Damaraland, the traditional land of the people. This will have far reaching political implications, which means that people will lose control on decision making power and wealth of natural resources from the area, whilst also being disenfranchised from their farming benefits and potential economic opportunities from being traditional land owners.105

13.5 Creating the Palmwag Tourism Concession

The Damara Regional Authority, and especially its leader Justus ǁGaroëb, wished to support conservation in Damaraland and reportedly worked with the DNC to halt the granting of hunting permits in the north-west.106 At the same time, the DRA did not wish to hand over this area of communal land to the government for it to be proclaimed as a ‘park’, as advocated in the proposals outlined in Section 13.4, particularly those by Eloff, Rupert and associates. Gaob (King) ǁGaroëb remembers these struggles with central government in South Africa and South West Africa in the following terms:

the only place where they wanted wildlife was Etosha. And they wanted us to link Etosha with western Damaraland and we did not want that because, firstly our area might be smaller because Etosha was not within Damaraland and we did not have any say on Etosha—now if we decided to join Etosha and western Damaraland that will fall with the central government and we will not have any say whatsoever. So it was a big fight. They wanted to extend Etosha to the western Damaraland. We did not want that. We rather want to extend Damaraland to Etosha so that we can have more say on the wildlife.107

This is the moment in the mid-1980s when the Palmwag Tourism Concession in its present form came into existence, alongside the Etendeka and Hobatere Tourism Concessions (Figure 13.1), an aim being to promote rural development through tourism linked with wildlife, cultural heritage and the spectacular landscapes of Damaraland. As Gaob ǁGaroëb describes, ‘we decided no no, this is not a hunting farm, it’s just to make room for photography and all those good things so that our people could get hold of the areas not to kill but to photograph things’.108 Initially blocked by the DNC on the grounds that tourism development is ‘a central government responsibility’,109 the DRA decided instead ‘to lease out the area to tourism operators, which they were legally entitled to do’.110

Drawing here on a 2002 report by Garth Owen-Smith,111 in the mid-1980s, K.H. Grutemayer became the first operator of the Palmwag Tourism Concession, being leased the western concession of 582,622 ha of communal land by the DRA, with Louw Schoeman who ran Skeleton Coast Fly-in Safaris taking on the southern concession located south of the newly positioned vet fence. At the time Grutemayer already ‘ran occasional 4x4 safaris [through his company Desert Adventure Safari Tours, DAS] through the west of Damaraland’. Palmwag Lodge, consisting of a small campsite and five reed hut shelters converted from the former Palmwag hunting camp, opened in July 1986.112 The DRA derived an annual lease fee and a small levy charged to people driving into the ‘open area’ near to the lodge that remains the ‘Palmwag Day Visitors Area’ today. Access restrictions relied on a 1928 law ‘requiring persons driving off proclaimed roads on State Land to obtain a permit from the “Secretary for South West Africa”’, which in fact continues to be deployed in asserting ‘no entry’ to the area (see Section 13.6). In 1986 the former ANVO hunting concession was split along the Palmwag-Sesfontein road to become the Palmwag and Etendeka concessions to the west and east respectively (see Figure 13.1), with the desert area south of the newly positioned vet fence and !Uǂgab river becoming, for a while, a third concession area. These Concessions were seen by the DRA very much as leases for the exclusive use of an area for a specific identified purpose, in this case, tourism. As ǁGaroëb later writes,

[s]uch [a] Concession Area can only be exclusive in relation to the specific purpose for which it was granted/leased. Concessionaire can therefore not prevent the right of entry by others, such as indigenous peoples of the area who for what ever cultural or religious reasons or for collecting wood, wild food, herbs etc. may want to enter such Concession area without any permission to do so.113

From the Regional Authority’s perspective, the concession was not intended to keep out people who had cross-generational links with the area and its resources. The DRA also intended to support development of a modern tourism route that would enhance self-determination through connecting and promoting different sites through the region. This is clear from an amazingly forward-looking brochure encouraging tourism through the Damaraland Homeland in the 1980s. In the DRA’s tourism vision for the homeland, Palmwag was clearly part of a route that connected sites such as the Brandberg/Dâures, Twyfelfontein/|Ui-ǁaes, Doros Crater and the Sesfontein Fort of German colonial times, which the DRA began to renovate using labour by young people in Sesfontein.114 The brochure combines images of diverse local peoples, livestock and wildlife in ways that strongly prefigure the conservancy ethos and aesthetic that emerged in the 1990s, as shown in Figure 13.18.

|

|

Fig. 13.18 Pages from a mid-1980s brochure produced under the Damaraland Regional Authority (DRA) advertising specific tourism routes through Damaraland and depicting a combination of spectacular landscapes, wildlife, cultural heritage and livelihood practices. Source: DRA (n.d., used with permission), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

13.6 To conclude: The Palmwag Concession, post-Independence

Namibia gained Independence on 21 March 1990, becoming the Republic of Namibia, at which point the second-tier authorities were dismantled. According to Owen-Smith, in 1993 the new Government of the Republic of Namibia (GRN) decided that the tourism concessions of the north-west should fall under the Directorate of Tourism, and were renewed annually until 1995.115 The emphasis of wildlife conservation in this immediate post-Independence moment was on extending wildlife utilisation possibilities into communally-managed areas, i.e. the pre-Independence homeland areas beyond freehold settler farming areas. In 1995 the MET thus published a position paper on ‘Wildlife Management, utilisation and tourism on communal land: Using conservancies and wildlife councils to enable communal area residents to use and benefit from wildlife on their land’.116 The Nature Conservation Amendment Act, 5 of 1996 enabled the establishment of conservancies on communal land, and consumptive use of wildlife in communal areas to facilitate livelihood benefits.

In conjunction with the registration of conservancies in the north-west (see Chapter 3), this process effected a rapid and significant shift away from the former DRA’s emphasis on rather low-key photographic tourism, towards intensive wildlife harvesting (currently in decline due to drought and over-harvesting),117 and external investment into the building of high-end tourism facilities. From 1995 the lessees of the north-west tourism concessions were given 5-year concessions ‘with the option of a five-year renewal’, with a growing emphasis on negotiating benefit-sharing contracts with neighbouring conservancies:118 culminating in the contractual arrangements indicated in Figure 3.3. For the Palmwag Concession the neighbouring conservancies are Torra on its southern border, registered in 1998, and Sesfontein and Anabeb to its north, both registered in July 2003. In 2011 these conservancies ‘were given tourism rights over the Palmwag concession’,119 via the signing of a ‘Head Concession Agreement for the Palmwag Concession, Kunene Region’ with the MET. These conservancies subsequently entered into contractual arrangements with tourism operators in the Palmwag Concession, namely Wilderness Safaris, Antigua Investments, and more recently the Gondwana Collection of Lodges; facilitated by the establishment of a legal Trust—the Big 3 Trust—headed by the Chairmen of the three conservancies. In contrast to the approach of the DRA before Independence, and no doubt connected with recent poaching scares in relation especially to black rhino, a post-Independence emphasis on boundary-marking and access restriction is noticeable (see Figure 13.19).

Fig. 13.19 ‘No entry’ sign marking the boundary of the Palmwag Concession, following new contractual arrangements between the then MET, the three conservancies neighbouring the concession, and one of the tourism operators (Wilderness Safaris). Photo: © Sian Sullivan, 20.11.2014, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

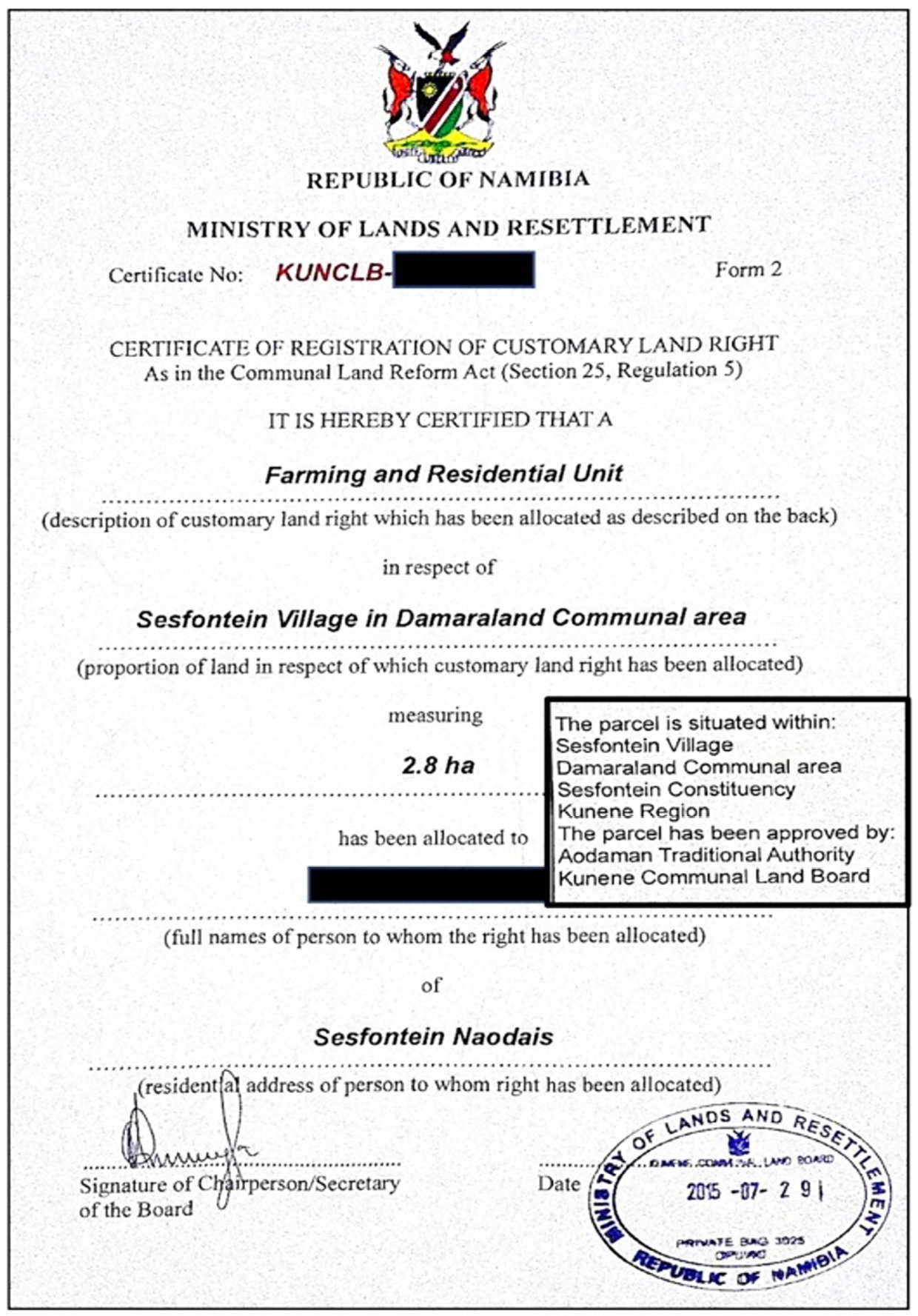

At the same time, however, the concession continues to be located within the Damaraland Communal Land Area, as delineated in Namibia’s Communal Land Reform Act, 5 of 2002.120 A function of this Act is to permit the registration of Customary Land Rights within Communal Land Areas, following approval by both the relevant Regional Land Board and recognised Traditional Authority (TA) under the Namibian Traditional Authorities Act, 25 of 2000 (also see Chapter 6). The Customary Land Rights Certificate shared in Figure 13.20, for example, has thus been approved by the Kunene Communal Land Board and the ǂAo-Dama TA. It seems likely that the Nami-Daman Traditional Authority, formalised in 2021 and working primarily from Sesfontein/!Nani|aus,121 will be an increasingly important actor regarding land issues through this western area into the future. This TA represents families with cross-generational histories connected with this western area, including the Palmwag Concession, as documented in Section 13.3.

Fig. 13.20 An example of a Certificate of Registration of a Customary Land Right for a ‘farming and residential unit’, as per Communal Land Reform Act 2002, plus amendments, showing the Land Board and Traditional Authority approval. Author’s research data, shared with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Indeed, running through the dynamics regarding the Palmwag area and its neighbours seems to be a tension between two key articles in Namibia’s constitution: namely Article 95(l) affirming sustainable use of Namibia’s ‘living natural resources’; and Article 19 affirming the right to ‘enjoy, practise, profess, maintain and promote any culture, language, tradition or religion’.122 In relation to communal areas such as the Damaraland Communal Land Area, in which the Palmwag and other tourism concessions are situated, the former article has tended to be used to promote external investment and profit, on the understanding that fees are paid to conservancies to offset the use of land and living resources for these purposes. As observed elsewhere,123 however, an effect has been a deepening of the loss of access to ‘places and “resources” with which cultural expression is entangled’, giving rise to potential friction between these two dimensions of the constitution (also see Chapters 12, 14 and 15).

In particular, the Indigenous histories and values documented in Section 13.3 remain in the shadows.124 Indeed, conservationists have been urged explicitly to treat with caution Damara/ǂNūkhoe claims to the concessions areas they created, namely Palmwag, Etendeka and Hobatere. In a statement that simultaneously discounts ethnicity whilst promoting ‘local Herero traditional authorities’, Owen-Smith, for example, writes:

[a]lthough the Damara Representative Authority (under Chief Justus Garoeb) can rightly claim to have played a major role in the conservation of wildlife in Damaraland, as well as having created the present tourist concession areas, this institution no longer exists. Consequently, although some of the traditional leaders in the present Damara Royal House were previously Damara Executive Committee members, their claim to benefit from the concession areas in the future should be treated with caution. Namibia’s new constitution no longer recognizes land-rights based on ethnicity and the local Herero traditional authorities—who have steadfastly supported conservation and kept livestock out of the concession areas—could make equal claims to benefit economically from them.125

Since Independence it has indeed been documented for conservancies neighbouring the Palmwag Concession that ‘Damara’ are concerned ‘only the Herero are benefitting [from the conservancy, in this case Anabeb]. They are the ones who come to hunt; they receive the fat meat […]’.126 Following the late Val Plumwood’s environmental justice analysis of ‘shadow places’ as ‘sacrificial’ or ‘denied’ places, it appears that certain groups of people here are constructed and treated as ‘shadow people’: as literally in the shadows of others who, for whatever reason, are able to be more visible, more recognised, although this recognition may ‘rest on the subordination or instrumentalisation’ of others.127 This situation, however, does not make the shared realities of those in the shadows, or the repeated distortions of their histories, any less real. Instead, it poses a challenge to attend to injustices from the past that remain in the shadows, but continue to haunt the present through ongoing real, but poorly understood, concerns, and the frictions they give rise to.

This chapter has documented dynamics in an arguably longstanding tussle between the push for more space for conservation control, Indigenous histories and cultural heritage, and profit-making potential. The dance between these very different “powers” in the specific situation of Palmwag will no doubt continue into the future, making it important to understand their contexts and histories.

Archive Sources

NAN SWAA 2513 Inspection Report: Kaokoveld Native Reserve: September-October 1949, by Native Commissioner Ovamboland [Pritchard Eedes, ‘Nakale’], Ondangua 10.10.1949.

NAN SWAA Inspection of the Kaokoveld by Agricultural Officer. 6.2.1952.

NAN SWAA A 511/1, 1956-58. de la Bat.

NAN SWAA A 511/6, vol. 4 Game Reserves: Boundaries and Fencing 1958-1959. Secretary to Administrator, 26.8.1958.

NAN SWAA A.511/6 Extension of Game Reserve No. 2. 26.8.1958.

NAN SWAA WAT.74.W.W.71/4: Game Reserve: Kaokoveld Game Reserve. Triangle—Kowares-Warmquelle-Grootberg. Dams for elephants in the Kaokoveld Game Reserve. To the Director of Water Affairs 28.8.1958. Game Reserve No. 2: Water Holes. Director of Works to the Secretary for South West Africa, 9.2.1951.

NAN.A/5212/Add.1 Meeting with Headmen and residents of Sessfontein Native Reserve, 10 May 1962, United Nations Special Committee for South West Africa, 20.9.1962: 13–16.

NAN BOP 83 21/2/2. Meesterplan vire die Bewaring, Bestuur en Benutting van Natuurreservate in Damaraland en Kaokoland, 20.2.1975.

SWAA 1921. Territory of South-West Africa, Report of the Administrator For the Year 1921. Windhoek

SWAA 1923. Territory of South-West Africa, Report of the Administrator For the Year 1923. Windhoek

SWAA 1930. Territory of South-West Africa, Report of the Administrator For the Year 1930. Windhoek

SWAA 1939. Territory of South-West Africa, Report of the Administrator For the Year 1939. Windhoek.

Bibliography

ǁGaroëb, J. 1991 Address to the National Conference on Land Reform and the Land Question. Windhoek: Office of the Prime Minister.

ǁGaroëb, J. 2002 Damaraland Conservation Efforts, Pride, Heritage and Concession Areas. Presentation for MET Workshop on Concession Areas, 5-6 December 2002.

ǁGaroes, T.M. 2021. A forgotten case of the ǂNūkhoen / Damara people added to colonial German genocidal crimes in Namibia: We cannot fight the lightning during the rain. (ed. by Sullivan, S.) Future Pasts Working Paper Series 11 https://www.futurepasts.net/fpwp11-garoes-2021

Bluwstein, J., Cavanagh, C. and Fletcher, R. 2024. Securing conservation Lebensraum? The geo-, bio-, and ontopolitics of global conservation futures. Geoforum 153: 103752, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2023.103752

Bollig, M. 1998. The colonial encapsulation of the north-western Namibian pastoral economy. Africa 68(4): 506–36, https://doi.org/10.2307/1161164

Bollig, M. 2020. Shaping the African Savannah: From Capitalist Frontier to Arid Eden in Namibia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108764025

Botha, C. 2005. People and the environment in colonial Namibia. South African Historical Journal 52: 170–90, https://doi.org/10.1080/02582470509464869

de la Bat, B. 1982. Etosha. 75 Years. S.W.A. Annual: 11–26.

Denker, H. 2022. An Assessment of the Tourism Potential in the Eastern Ombonde-Hoanib People’s Landscape to Guide Tourism Route Development. Windhoek: GIZ, https://www.irdnc.org.na/pdf/Report-Ombonde-Hoanib-Assessment-of-Tourism-Potential.pdf

Fuller, B.B. 1993. Institutional Appropriation and Social Change Among Agropastoralists in Central Namibia 1916–1988. Unpublished PhD dissertation, Boston Graduate School, Boston.

GRN 2013[2002]. Communal Land Reform Act, no. 5, 2002. 12.8.2002, plus amendments. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia.

GRN 2014[1990]. Namibian Constitution. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia, https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Namibia_2014

Hall-Martin, A., Walker, C. and Bothma, J. du P. 1988. Kaokoveld: The Last Wilderness. Johannesburg: Southern Book Publishers.

Henrichsen, D. 2010. Pastoral modernity, territoriality and colonial transformations in central Namibia, 1860s–1904. In Limb, P., Etherington, N. and Midgley, P. (eds.) Grappling with the Beast: Indigenous Southern African Responses to Colonialism, 1840-1930. Leiden: Brill, 87–114, https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004178779.i-378.22

Hesse, H. 1906. Die Landfrage und die Frage der Rechtsgültigkeit der Konzessionen In Südwestafrika: Ein Beitrag zur wirtschaftlichen und finanziellen Entwickelung des Schutzgebietes. I. Teil. Jena: Hermann Costenoble.

Jacobsohn, M. 1998[1990]. Himba: Nomads of Namibia. Cape Town: Struik.