15. ‘Walking through places’: Exploring the former lifeworld of Haiǁom in Etosha

©2024 Ute Dieckmann, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0402.15

Abstract

This chapter engages with differing conceptions of the land that has become Namibia’s “flagship park” and premier tourist attraction. By tourists, Etosha might be perceived either as an untamed wilderness or a large zoo; for scientists, it might represent an excellent research opportunity to test zoological hypotheses; and for farmers on the border farms, it might be a source of nuisance, its wildlife causing trouble and—at times—economic loss. For Haiǁom, Etosha represents part of their former lifeworld; an ecology of which they were an integral part. Their ancestors lived across the region alongside other Khoekhoegowab- and San-speaking peoples before major immigrations of Bantu speakers during the last 500 years of the second millennium. In the first half of the 20th century, they were mainly living from hunting and gathering, with some families keeping a few goats or cattle, combined with occasional seasonal work and temporary employment. Drawing on a cultural mapping project, combined with oral history and archival research, this chapter explores the lifeworld of Haiǁom in Etosha and their relations to the land, to other humans and to beyond-human inhabitants, prior to their eviction in the 1950s. Anthropologist Tim Ingold’s concept of “meshwork” is drawn on as a suitable concept for capturing Haiǁom’s being-in-Etosha as being-in-relations. The picture emerging from the research is that of a dense relational web of land, kinship, humans, animals, plants and spirit beings, an integrated ecology and an almost forgotten past which should, in line with this publication’s aim, be acknowledged by, and integrated into, future nature conservation policies and practices.

15.1 Introduction1

This chapter aims to (re-)animate the lifeworld of Haiǁom formerly living in the south-eastern area of Game Reserve No. 2, that became Etosha National Park (ENP) in 1967 (for historical contextualisation see Chapters 1 and 2). For Haiǁom, Etosha represents part of their former lifeworld; part of their “homeland”, an ecology of which they were an integral part. Their ancestors lived alongside other Khoekhoegowab and San language speakers across the region before major immigrations of Bantu speakers during the last 500 years of the second millennium.2 White settlers increasingly occupied the surrounding area, with the result that nearly all of the land south of the Veterinary Cordon Fence (VCF) or “Red Line” formerly inhabited by Haiǁom was occupied by settlers in the 1930s. The game reserve became the last refuge where Haiǁom still practised a hunting and gathering lifestyle. Up to the 1940s, Haiǁom were regarded as “part and parcel” of the game reserve. All in all, between a few hundred and 1,000 Haiǁom lived in the park until the early 1950s when they were evicted (also see Chapters 2, 4 and 16).

Drawing on a cultural mapping project in which I was involved, as well as archival and oral history research conducted for my PhD and subsequent research, I explore Haiǁom “being-in-Etosha”,3 their relations to the land, to other humans and to beyond-human inhabitants, prior to their eviction.4 Keith Basso notes that ‘wisdom sits in places’,5 which serves as a guiding principle: via specific places, I try to convey what it might have meant for Haiǁom to be-in-Etosha and to live with the human and beyond-human beings in the area.6 Maybe we realise with Basso that ‘[p]laces … are as much a part of us as we are part of them, and senses of place—yours, mine, and everyone else’s—partake complexly of both’.7

‘Walking through places’ instead of ‘walking to places’ hints at both the methodology of cultural mapping and the structure of the chapter. Cultural mapping involves moving in the landscape, and walking around named places which do not have a fixed boundary, but are “just” places. It is not possible to go “to” places and to stop there as if reaching a target/destination. Cultural mapping involves exploring places, finding threads, and finding tracks to other places. The structure of the chapter follows this walking, and the exploration and investigation of threads emerging around these places.

I first describe the methodology and material on which the chapter is based, before “going through” specific places with particular individuals, aiming at (re-)animating the former lifeworld of Haiǁom in Etosha. All these places lead to specific persons, to beings-beyond-the-human (e.g. animals or ancestors), to other places and other people, and to the past. Following Ingold,8 I visualise these Etosha places with Haiǁom experience as a meshwork of entangled threads, humans, animals, plants, ancestors, and spirit-beings, woven into the land. In this light, I further explore the results of their eviction. Finally, I argue that Indigenous lifeworlds, their experiences and practices, should enter the conservation conversation and be considered for future conservation efforts in Namibia (see also Chapters 12, 13 and 14).

15.2 Exploring meaning: Methodology and outcomes

I went to Etosha on various field trips between 2000 and 2006 to explore the history of the national park, and in particular the developments regarding the former population of the south-eastern part of the park, as part of my PhD research.9 In 2001, due to my ongoing research in Etosha, I became involved in a project which was aimed at the creation of “cultural maps” documenting the historical presence of Haiǁom within the area, the representation of a “forgotten past” to deconstruct the image of Etosha as an untouched and timeless wilderness.10 Other researchers were temporarily part of our project over the years.11 As the process gained momentum, the work, which had started rather informally involving various individuals and organisations, needed to be formalised in a proper organisation, leading to establishment of the Xoms |Omis Project (Etosha Heritage Project) in 2007, under the guidance of the Legal Assistance Centre (LAC) in Windhoek: see https://www.xoms-omis.org/.12

The main objectives of the project were to research, maintain, protect and promote Haiǁom heritage of ENP and its surrounding area in order to capitalise on that heritage in the tourism sector; and to develop capacity-building programmes based on this heritage for Haiǁom individuals with a genuine interest in the cultural, historical and environmental heritage of the Park. Furthermore, we aimed at designing, creating, supporting and implementing sustainable livelihood projects for Haiǁom communities indigenous to, or with strong historical associations with, the park—based on Haiǁom cultural heritage of the Etosha area.

During the research, we worked mainly with a group of elderly Haiǁom men: above all Kadisen ǁKhumub, born around 1940; Willem Dauxab, born around 1938; Jacob Uibeb, born around 1935; Jan Tsumib, born around 1945; Hans Haneb, born around 1929; Tobias Haneb, born around 1925; and Axarob ǁOreseb, born around 1940. All of them were born in Etosha at various settlements in different areas and had partly worked in Etosha and on farms in the vicinity in the years after their eviction. We gained research permission from the then Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET) to work in ENP which permitted us, under specific conditions, to leave the car and to walk around in the park. We regularly undertook journeys in the park, visiting old places of meaning for the Haiǁom, finding places that have never been on or had disappeared from official maps and hearing their stories connected to the places. This ‘on-site oral history’13 as a means of ‘cultural landscape mapping’ proved highly successful, as it revitalised knowledges, practices and experiences (also see Chapters 12 and 13). I follow this way of working with the structure of this chapter: specific places serve as gateways to convey meaning.

Moreover, we worked at the research camp at Okaukuejo (one of the rest camps in the park), sitting in the shade of a sink roof, surrounded by game-proof fences, for deepening and revising the documented information. During the years we worked together, we got more and more familiar with each other and became a well-integrated team with different individuals taking over different roles (e.g. Jan knew the north-eastern part around Namutoni quite well, Hans had most of the stories, but did not provide the necessary context for me, Willem complemented the stories with his knowledge, Kadisen knew how to explain to me in a way that I would understand). It is one of my most impressive and valuable experiences to have worked for many years with this team of elderly men, who often arrived earlier than the time agreed upon, who enjoyed working with me and who never became tired of my (stupid) questions (or at least did not show it). We spoke Afrikaans but recorded place names, plants and important concepts in Haiǁom (part of the Khoekhoegowab dialect continuum). We built up a trusting relationship over the years and we shared a commitment to the work, because we all enjoyed the work and deemed it important. The envisaged products had certainly a motivating force too, but they were not the main driver to continue our work.

The archaeo-zoologist designed a questionnaire on animals in Etosha, which we worked through with the core team for most of the animals in Etosha; questions referred to knowledge on nutrition, reproduction, the behaviour of the specific animal, hunting methods, spoor of the animal, meat processing and distribution, taboos and other usages. The archaeologists of the project undertook an archaeological survey and archaeological investigations of one long-term settlement, ǂHomob (see Section 15.3.2), and archaeo-zoological data were collected at the same site.14 The work in this core team was complemented by interviews with other elderly Haiǁom in Etosha as well as in Outjo (the next town 120 km south of Etosha) for their life stories and oral history. I could not work as much with elderly women as with elderly men, because elderly women were less acquainted with outsiders (who were neither Haiǁom nor employers of domestic workers or cleaners), and often less fluent in Afrikaans. The men who had worked in Etosha had been able to keep their memories alive due to their work-related journeys in Etosha after the 1950s, whilst the women had not been in Etosha (outside the rest camps) for around 50 years and their memory was therefore more buried than the memory of the men. Still, we also undertook several trips with elderly women in Etosha.

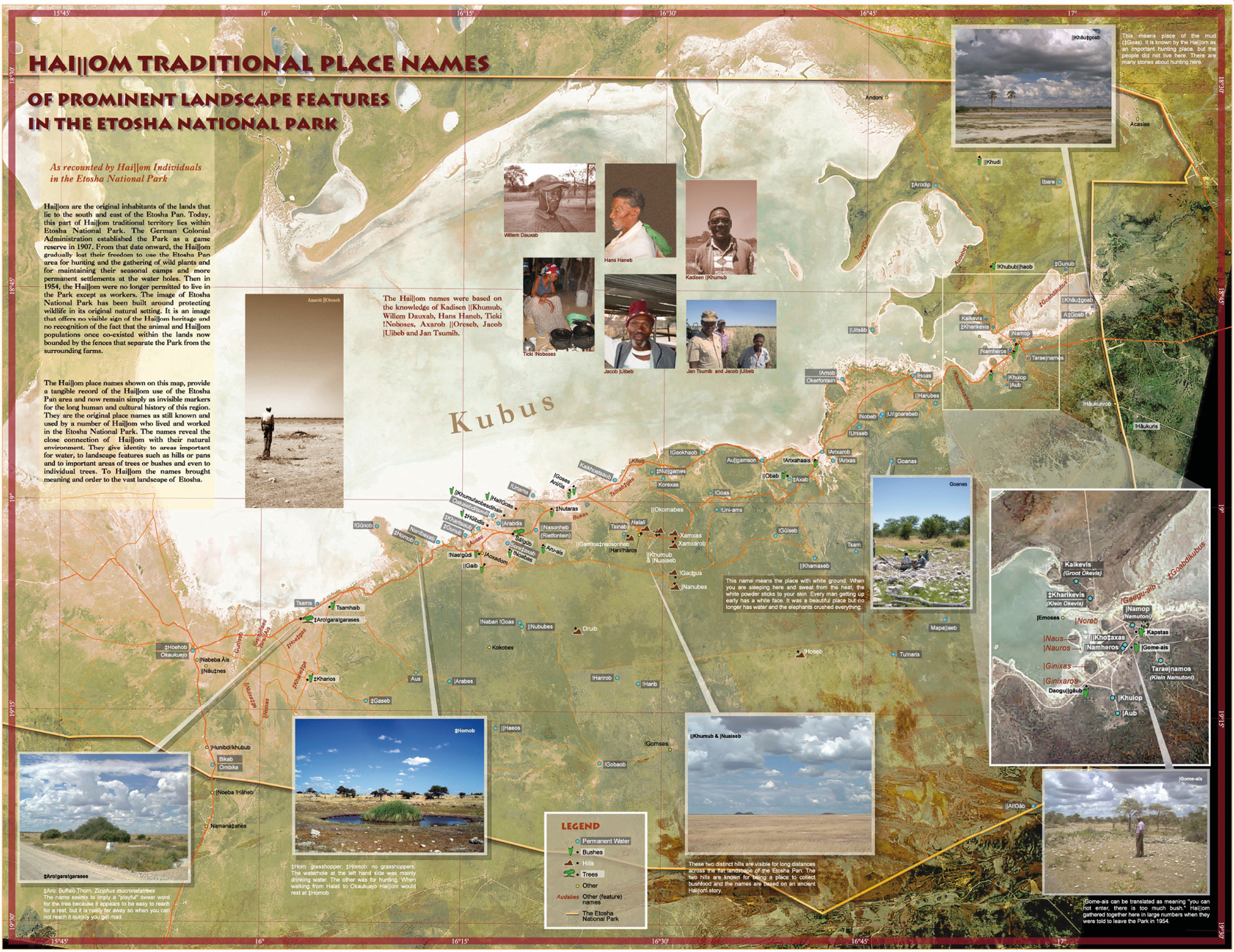

Fig. 15.1 Haiǁom traditional place names of prominent landscape features in Etosha National Park. © Xoms |Omis Project, used with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Within the project, we produced a place name map (Figure 15.1), a map of Haiǁom traditional ways of hunting and distribution of resources, two hunting posters and two bushfood posters, two lifeline maps (drafts) and two community posters which were not published.15 After the main funding came to an end I worked with the core team to write a tour guide book16 and a children’s book,17 and we produced some postcards and T-Shirts with other smaller funding from different donors18 to conserve and promote the cultural heritage of the Haiǁom and to raise some income for the project.

15.3. Walking through places

In this section, I take specific places, explored with specific individuals, as entry points to the meshwork of human, animal, plant, ancestor, and spirit-being threads, woven into the land.19

15.3.1 ǂAro!gara!garases: A tree with its own nickname

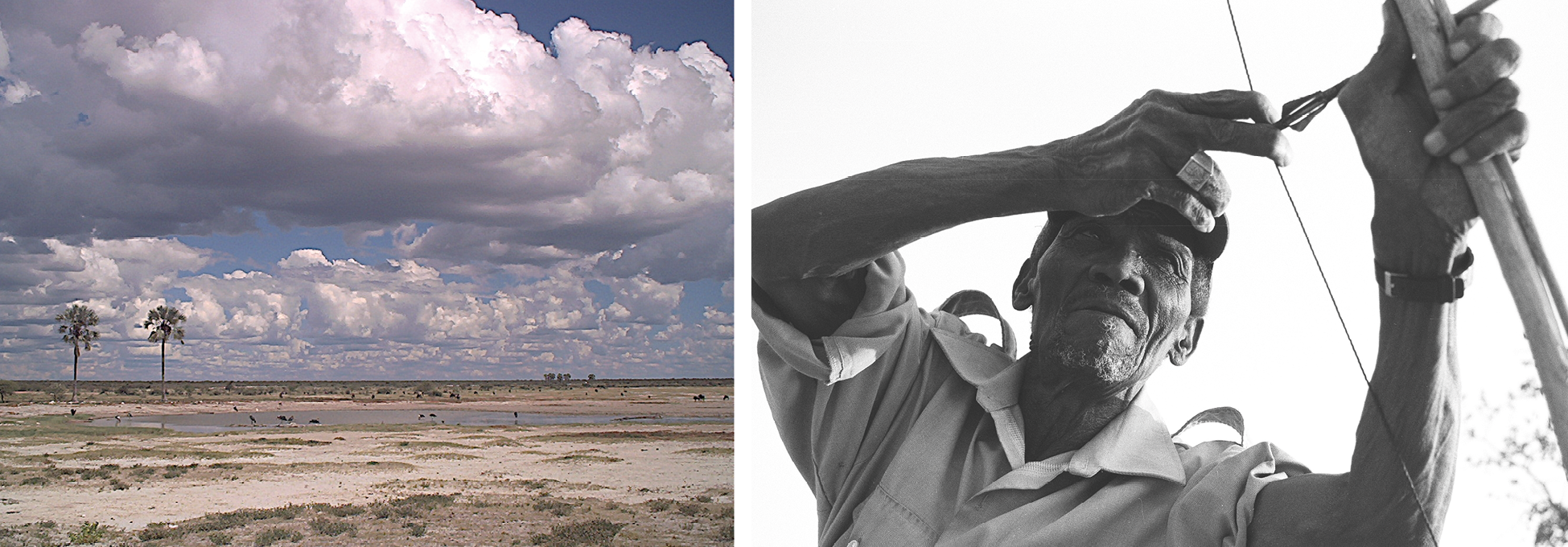

During the time of the cultural mapping research, one specific tree could still be found close to the main road about 17 km from Okaukuejo. We passed it many times on our countless trips visiting different places in the park. It had been given the nickname ǂAro!gara!garases (Figure 15.2).

Fig. 15.2 ǂAro!gara!garases from afar on the left, and at the place on the right. Photos: © Harald Sterly, 2002, Xom |Omis Project, used with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

ǂAro.s is the Khoekhoegowab term for Ziziphus mucronata (buffalo thorn, or in Afrikaans, blinkblaar wag-’n-bietjie—literally “shiny leaf wait-a-bit”—a reference to the notorious capacity of its thorns to snag and halt the unwary passer-by). This species occurs as a large shrub or bushy tree throughout Etosha, usually as a single plant at waterholes. Its strong, flexible wood was used to make bows, and the roots, bark and leaves to treat coughs and chest ailments. Though bitter, the ochre-red, fleshy berries were eaten raw or boiled, which rendered them slightly less bitter. A Haiǁom proverb that features this bitter bounty reveals a wry view of relationships: ‘marriage is not like eating ǂâun (raisin bush, with its sweet berries) but like eating ǂaron!’

The name of this specific individual, ǂAro!gara!garases, contains a swear word, humorously cursing the tree. In the flat terrain, the tree is visible from a great distance. In the past, Haiǁom used to undertake hunting and gathering expeditions in the area, or they walked from the police station at Okaukuejo back to their settlements further west. When they became tired in the heat of the day, they would head towards this tree to rest in its shade. In the flat terrain, however, it was easy to underestimate distances, and so after walking in its direction for what might have seemed like hours, they would observe that it scarcely seemed to be any closer. In frustration, they would then refer to it as ‘ǂAro!gara!garases’—‘that * tree!’. When asked about this specific tree, an elderly lady, Ticki !Noboses, who had been born in Etosha (at Ombika, Bikab) but now living in Outjo (around 150 km away from this tree and around 50 years after experiencing it), would perform as a walker moving towards the tree carrying things in the heat, being exhausted and cursing the tree. It was easy to imagine Haiǁom longing for a short break in the burning sun, becoming angry because the shrub with its shade did not appear to come any closer.

15.3.2 Tsînaib and ǂHomob: Kinship engraved in the landscape

Fig. 15.3 Mark Berry, Kadison ǁKhumub, Willem Dauxab and Hans Haneb in search of the (former) Tsînaib well. Photo: © Harald Sterly, 2002, Xom |Omis Project, used with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

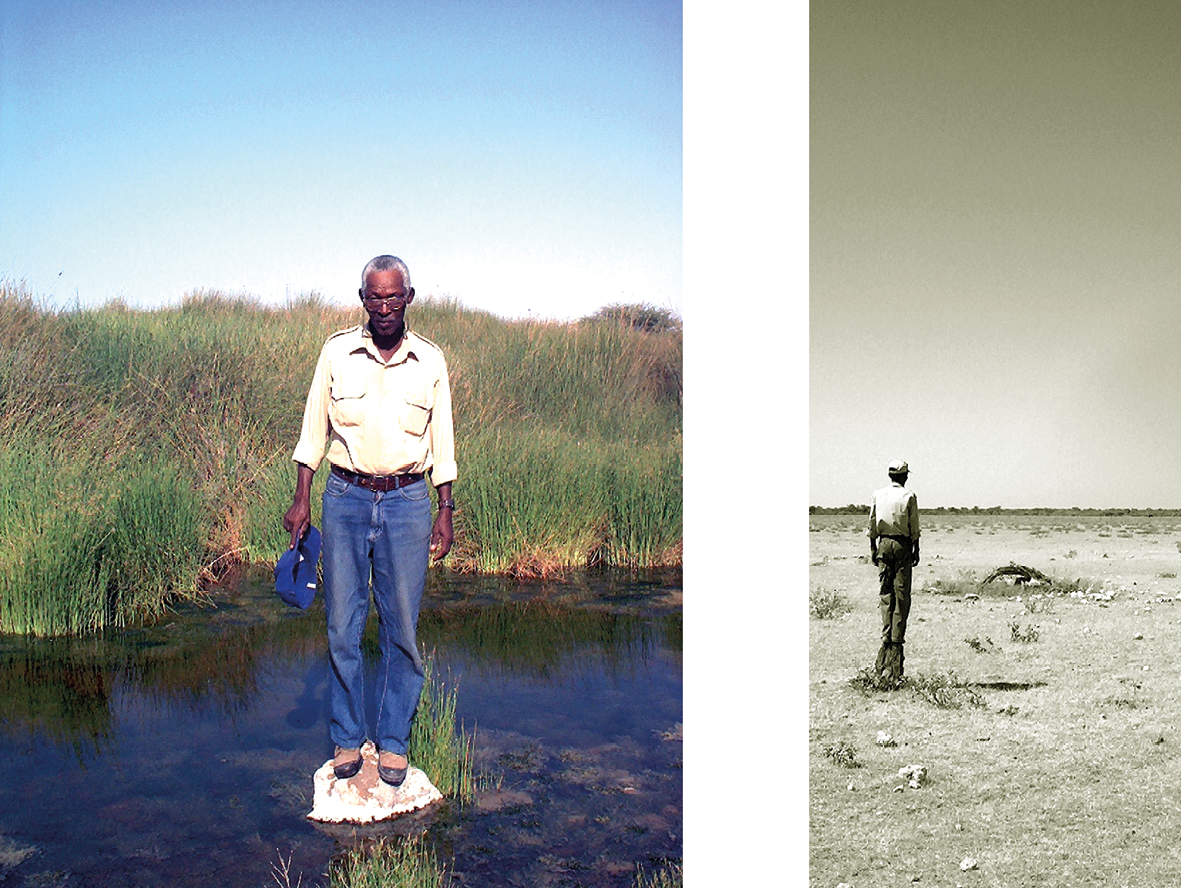

Fig. 15.4 On the left Willem Dauxab stands at !Gunub. Photo: © Harald Sterly, 2002. On the right Axarob ǁOreseb stands at |Nameros. Photo: © James Suzman, 2002. Both photos are part of the Xom |Omis Project, and are used with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

While I did not record a specific (or rather individual) relationality for ǂAro!gara!garases, with the above narrative constituting more of a “shared meaning” or “shared knowledge”, descriptions at other places point towards relationalities between specific families and respective places: testifying to connections of people and places, the belonging of families to land as well as vice versa—the belonging of land to families.

Tsînaib is a natural well with a permanent settlement situated close to Halali, but has been almost entirely forgotten and is no longer accessible to the public (see Figure 15.3). The Halali tourist camp was opened in 1967 and the waterhole that can be viewed today from the camp is not a natural spring. Indeed, especially in the western parts of the park, many of the accessible waterholes are artificial, or at least are assisted by electric pumps or windmills (see Chapter 10): Etosha’s “wilderness” requires substantial management and maintenance. The well Tsînaib, however, was not an artificial waterhole and needed to be regularly maintained and cleansed of mud. The water quality was said to be relatively poor, but it was nevertheless fit for human consumption. Because the well was not an open fountain, it was not easy for animals to drink there, and Haiǁom rather hunted on nearby plains than at Tsînaib itself.

Tsînaib serves as an entry point to family networks woven into the landscape. Two Haiǁom men who were born at Tsînaib were Willem Dauxab and Axarob ǁOreseb (see Figure 15.4). Axarob was a solitary, shy person who found it difficult to interact with people. He was mostly at home living alone, out in the bush; his dogs were ample company. When the Haiǁom had been expelled from their former settlements, Axarob refused to settle down at the tourist camps or outside the park on a commercial farm. He continued through the 1960s and early 1970s to spend extensive periods “in the bush” in Etosha with his dogs, surviving by hunting, which had by then become “poaching”. Both Willem Dauxab and Axarob ǁOreseb died in 2008.

I follow the spatial-kin thread of Willem Dauxab.20 His father was Fritz Dauxab, originating from the !Harib area (south of Tsînaib, see Figure 15.5 for many of the places named here). Fritz had three different wives in his lifetime, originating from different areas: Aia ǁGamgaebes was born at Tsînaib; her sister |Noagus ǁGamgaebes was born at !Gabi!Goab (the old location at ǂHoehob (Okaukuejo); and Anna ǁKhumus was from ǁNububes. Fritz reportedly had at least nine children. Aia and Fritz had six children born at Tsînaib, ǁNububes and ǂHoehob. Her sister |Noagus and Fritz had one child, Willem, born at Tsînaib, who grew up with his stepfather Petrus !Khariseb, originating from the area of Kevis (Kaikebis, also ǂKharikebis). Anna and Fritz had three children, born at ǁNububes and ǂHoehob. Aia and |Noagus also had two brothers (or cross-cousins),21 with the surname !Noboseb (since their mother was a !Noboses). The brothers, Willem’s uncles, stayed at ǂHomob (see Figure 15.5).22

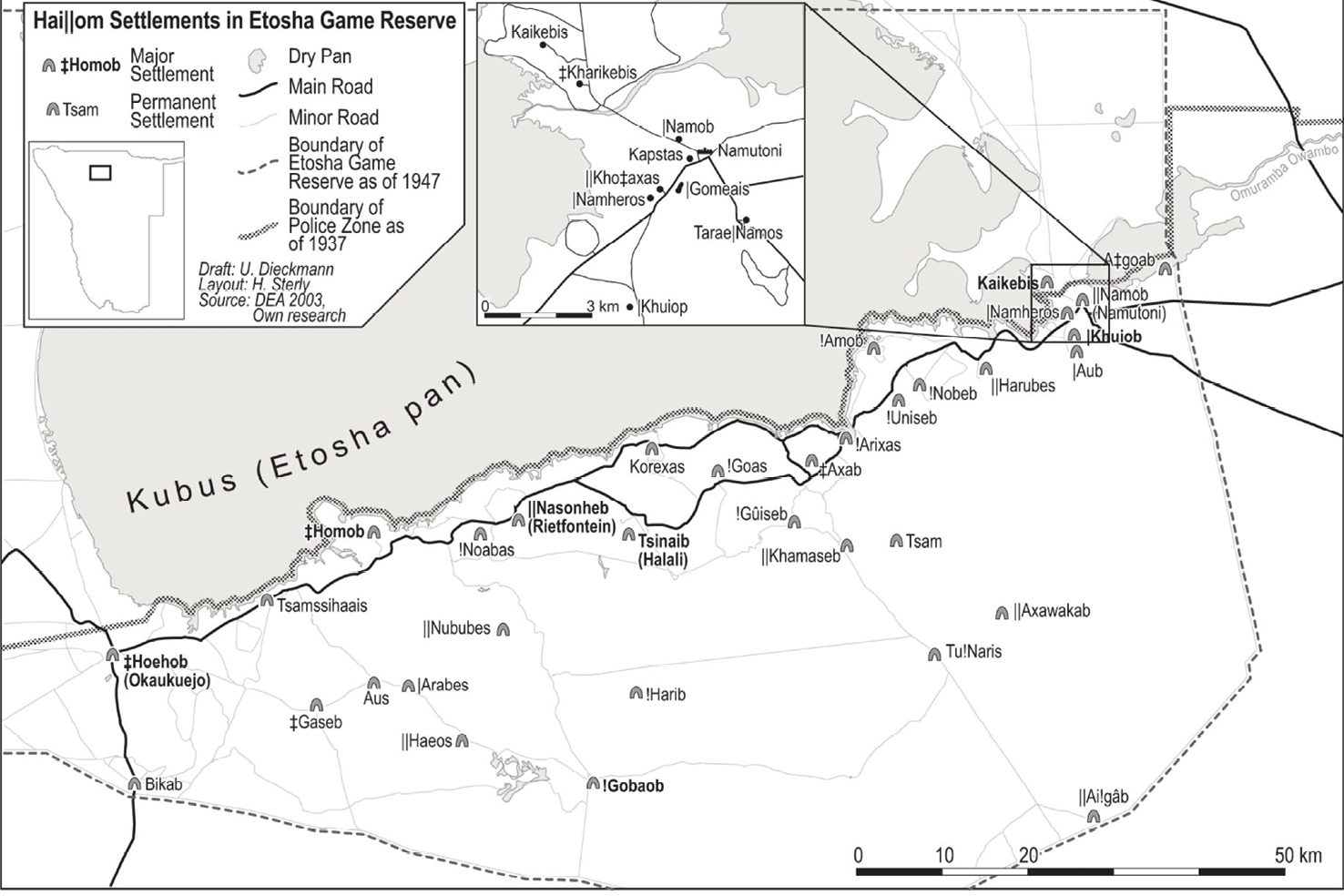

Fig. 15.5 Map of some former settlements of Haiǁom in Etosha. © Xom |Omis Project, used with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Willem was born at Tsînaib where he stayed at times as a child with his mother |Noagus and stepfather Elias. I could not figure out if he stayed there most of the time in the year during his childhood, but certainly he considered it and the surrounding area as ‘our place’. At times, they went to the area of Namutoni (|Namob), where a sister of his stepfather Elias was staying (it is close to Kevis, where his stepfather was from) and stayed there for a couple of months, at times during the rainy season, because there were a lot of ǂhûin trees (Berchemia discolor) in that area (whose fruits could be collected and stored for a couple of months). Later, they moved back to stay at Tsînaib again. Tsînaib was also known for a lot of bushfoods, both corms (e.g. !handi) as well as fruits and berries (e.g. Grewia spp.). Willem said:

[e]very year, we went here and there, visit each other, there, ǂAxab [not in the map] !Nobeb, /Ui!Goarebeb [not on the map, but close to !Nobeb], ǁHarubes, !Goas, |Uniams, ǂUniseb [not on the map], !Gûiseb , those were the places where we visited each other.23

He noted that ǂHomob was also ‘their place’ because the brother of his mother (Jan !Noboseb) and another brother (or cross-cousin) stayed there (he explained that !Noboseb was the mother’s father of the second husband of Ticki, mentioned above at ǂAro!gara!garases). We also established that the father of Willem’s mother, Franz ǁGamgaebeb was the father of Ticki ǁGamgaebes, born at Bikab, although the mother of Ticki was not the same as Willem’s grandmother (Ticki and her husband, the grandson of Jan !Noboseb, stayed in Outjo during the time of the interview).

Willem and his mother and stepfather from Tsînaib used to stay at times at ǂHomob as well because his mother’s brother was staying there. Note, that his father Fritz also stayed at ǂHomob (but in another settlement). Families with the surnames |Haudum and ǂGaesen were also in that area around ǂHomob, Aus and ǂGaseb and ǂHoehob. Apparently, the main settlement was at ǂHomob, but ‘when they liked to, they went to Aus, when they liked to they went to ǂGaseb. That is how they were moving around’, and they also went to ǂHoehob.

Willem and his mother (ǁGambaebes) only stayed with the mother’s brother (!Noboseb) at ǂHomob but did not move with them to the other places. Only in one year with a lot of rain (and mosquitoes), they also stayed around Aus (see Figure 15.5). Willem also related that there was a place of ǁGamgaebeb close to Otavi (a town east of the park, around 120 km away from ǂHomob), which he mentioned as another ‘place of us’, but he hasn’t been there, ‘it was the place of the old people’ (it seems he was referring to a time when mobility was less restricted before farms and the park were fenced).

In wintertime, the men staying at Tsînaib also went to |Goses (the same area as Tsînaib, but not on Figure 15.5) close to the Etosha pan, to hunt there and make biltong. Willem mentioned those places close to the pan (e.g. |Ani Us, Gaikhoetsaub, ǂKharitsaub, not on Figure 15.5), where the men from Tsînaib went hunting (while staying at |Goses) and other named places (wells, plains, etc., e.g. Bukas, Tsînabǂgas, not on map) where the men from Tsînaib used to hunt during other seasons. The men also went hunting at places in other families’ areas, but had to ask permission from the elders living in these areas. When they felt like gathering specific bushfood, e.g. ûinan (Cyanella sp.), during the right time of the year they went to the ǁNububes area which included Kokobes (not on Figure 15.5), known as a good place to collect ûinan. Presumably they had to ask the elders there as well for permission.

At ǂHomob, Willem could still point out the remnants of former dwellings and knew who had stayed where. His father, Fritz Dauxab, and his wife were ǂHomob residents. Fritz’s brother Lukas also stayed there; he had the reputation of not being a particularly good hunter, but he was always willing to carry the meat from the spot where it was killed back to the settlements. Furthermore, as mentioned, his mother and Willem’s stepfather resided temporarily there, as did his grandmother and her partner. As is suggested by these complex family ties, serial monogamy was common practice in those days. Willem also explained that one of the waterholes situated at ǂHomob was used mainly for hunting, and the other for drinking. The waterholes were about 500 m from the settlements.24

The tree where the adult male hunters used to prepare their meat (!hais) before handing over the rest to the women was still there during the time of our research, although it had been damaged by elephants. There is also another tree close to the waterhole, Willem explained, where before the eviction the Haiǁom used to wait during the tourist season for visitors, who took pictures of them and often rewarded them with sweets and oranges. Evidently, both textual representation of these family-spatial relations and maps with place names are highly inadequate to comprehend the spatial web arising from kinship ties and other experiences.

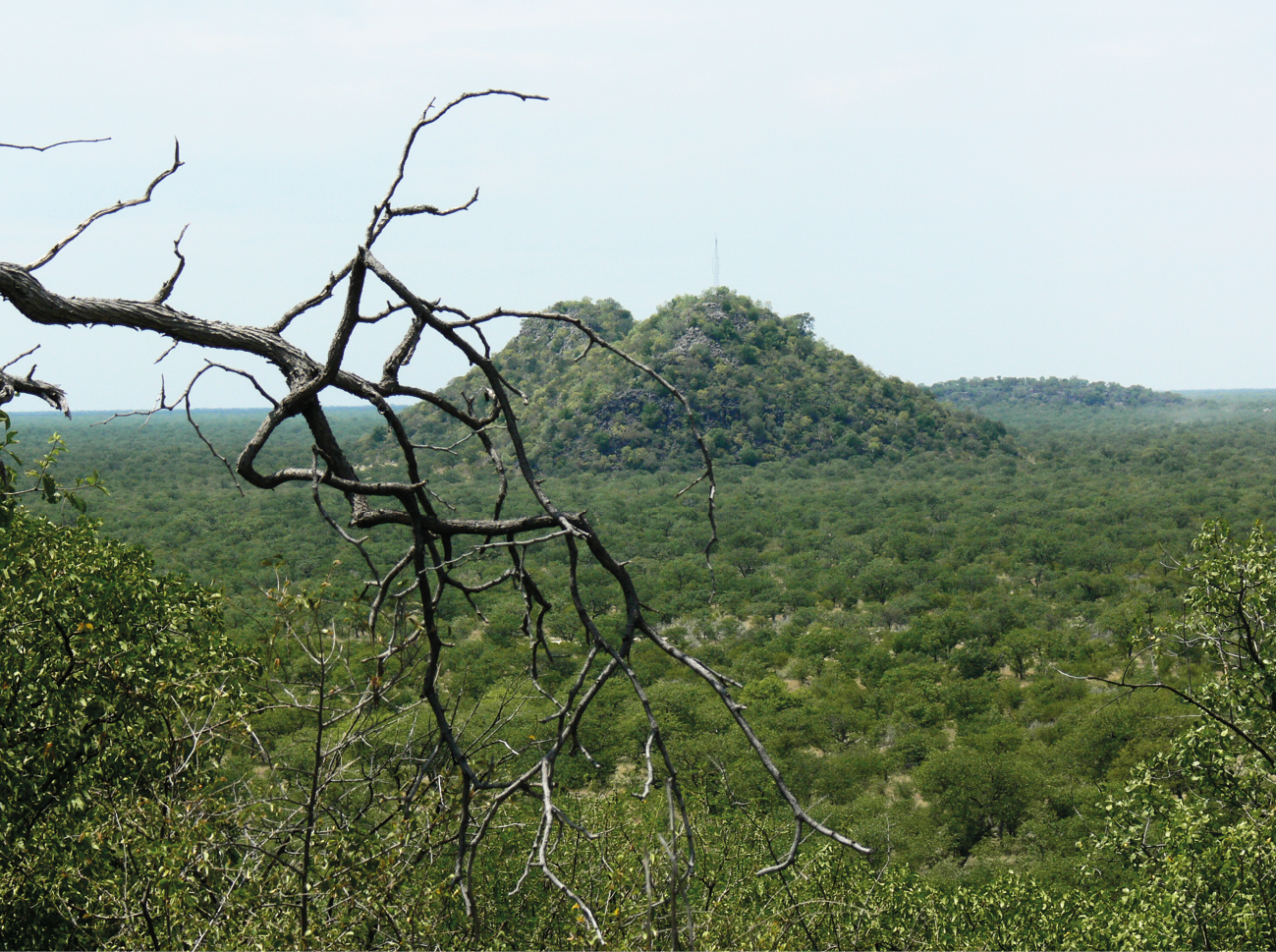

15.3.3 ǁKhumub and |Nuaiseb: Headmen signified in hills

ǁKhumub and |Nuaiseb are a pair of hills visible from a great distance across Etosha’s flat landscape—see Figure 15.6. They are renowned as prime venues for collecting bush food, in particular berries such as sabiron (Grewia villosa, mallow raisin), ǂâun (Grewia cf. flava, velvet raison) and ǂhûin (Berchemia discolor, bird plum), and corms like !hanni (Cyperus fulgens). The names of the hills refer to two men: |Nuaiseb was the surname of a headman whose extensive territory included these two hills. It was traditionally the responsibility of headmen to oversee the use of “natural resources”, including game and bush food, in the areas under their supervision, to ensure that they were not unsustainably exploited. |Nuaiseb decided to make one of the hills the responsibility of his nephew, whose surname was ǁKhumub. The hills, therefore, bear the names of their former Haiǁom supervisors.

Fig. 15.6 The hills ǁKhumub and |Nuaiseb viewed from Halali tourist camp. Photo: © Ute Dieckmann, 2003,

CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

On a local level, specific family groups were linked to specific areas (as well as to specific other elements, e.g. animals, natural items such as salt or the poisonous plant used for the hunt). The family groups living in specific areas (also called ‘territories’)25 were headed by family elders, who, as with many other hunter-gatherer groups, had to be respected men, sometimes women (called gaikhoeb or gaikhoes, big/senior man, big/senior woman or gaob/gaos, sometimes also called danakhoeb/danakhoes, literally head-man/head-woman) who could listen to the people, could mediate in the case of conflicts and were the ones overseeing “the sustainable use of resources” (in a western way of thinking). In my words, they were the ones who had the responsibility (the decision-making role) to care towards the people, the land and other elements/beings of the ecology. Maybe one could also call them stewards of the land, a concept, suggested for the Ju|’hoansi, another San group in Namibia.26

These men (or women) could also be replaced if it turned out that they were not fulfilling their duties. Usually, a grandson or nephew was chosen by the gaikhoeb because of his personal qualities, was taught by him and would take over the role later in life. Furthermore, it was a nested system. For example, a certain man might have been considered the headman of a larger area comprising several settlements, each settlement might have had a senior respected person as well. At times, the headman of the bigger area would assign a certain place/area to another man, e.g. his nephew, as in this case |Nuaiseb to ǁKhumub. At times, the Haiǁom core team members had to discuss who was the headman of a specific area, sometimes they also disagreed. Furthermore, the headmen list, which Friederich27 compiled, shows differences to our list of headmen at specific waterholes. This is a further indication that headmanship was a flexible institution, the important criteria being age and respect and that the elder “belonged” to the place, i.e. that he/she related to the land and was part of the family group connected to that specific patch of land.

15.3.4 !Gobaub: Shamans/healers, social organisation, snakes and history

!Gobaub is a waterhole close to the southern border of the park, which many Haiǁom remember very well. It is nowadays part of a tourism concession granted to the Haiǁom residing on the resettlement farms (for contextualisation, see Chapter 4). The information and quotes below are taken from the transcription/translation of my recordings (in Afrikaans) during a trip to !Gobaub and surrounding places, which I undertook with Kadisen ǁKhumub, Willem Dauxab, Jacob Uibeb, Hans Haneb and Axarob ǁOreseb. Since Kadisen’s connections to the place were the closest, he talked most of the time. Others gave brief comments or additions.

A couple of hundred metres from the waterhole is the grave of Petrus Oahetama Suxub, who was buried there in 1948. He was the father’s father of Kadisen ǁKhumub, and the headman in the area during Kadisen’s childhood. Kadisen also explained the origins of the (open) waterhole:

[t]hey [Haiǁom] say: !Gobaub, it was that man [Petrus Oahetama Suxub] who made it right. In the beginning, it was not a big water, it was only ǁgarus [pothole in stone]. But Suxub was a !gaiob [healer/shaman], he made the place big. […] This ǁgarus was first discovered by the dogs of !Gauaseb [surname]. When the dogs came back to !Gauaseb with wet paws, !Gauaseb called Suxub. Suxub, as a !gaiob, could also see the future, and had those spirits. Thus, he cut incisions into his feet in the evening, and put them into the water [?]. He just did it like that and went away, and then the thing burst. The water ran everywhere, it ran from here up to the veld, it was strong like that. […] It was beautiful [...]28

Kadisen mentioned that his grandfather Suxub was a !gaiob.29 A short explanation seems necessary: !gaiogu (shamans/healers) could communicate and negotiate with ǁgamagu30 (spirit beings), mainly during trance/healing dances,31 and through their connection to ǁgamagu, they had a wide array of skills and tasks: they could, for instance, heal diseases, they treated bad luck in hunting, they helped women when giving birth, and they brought rain.32 In the example above, the !gaiob could open water. 33

!Gobaub had become a permanent large and open waterhole, thanks to the potency of Suxub and henceforth many families could stay there permanently or seasonally. Kadisen could enumerate many surnames: Suxun34 and Hanen and ǁKhumun and ‘Aib and ǁGamxabeb, Sorosoab and |Hanixab came also here to make a turn’ (all surnames and he continued with further surnames). Surnames played and still play an important role in the social organisation of Haiǁom.35 In former times, the surname was passed on by cross-descent, from father to daughter and mother to son (this has changed with identification documents and official marriages, which confuses the system, because it was—at least in the past—not implemented consistently, and only gradually). Not surprisingly considering the naming system of Haiǁom, the same surnames were mentioned at various places. Surnames form a relevant and organising part of this socio-ecological knowledge, but on their own do not provide sufficient information, as shown above with Tsînaib and ǂHomob.

Suxub was reportedly the headman/steward of the place but !Gauaseb supported him/helped him, and acted as leader/steward as well. Suxub and his close male relatives were hunting at one side/in one direction of the waterhole while !Gauaseb and ‘his group’ was hunting on the other side. The hunters used to make !goadi [pit blinds] where they were sitting during the night. And when the animals were coming, they hunted them.

Since !Gobaub was an open fountain and thus different to Tsînaib, people did not take their drinking water directly from the fountain because the animals also used to come there. They dug water conduits to move the water some distance from the fountain. !Gauaseb and his group had made a different place for drinking water to that of Suxub and his family. !Gobaub had sufficient water to enable different family groups to stay in different settlements not too close to the fountain.

In the late 1940s, and early 1950s, it was also easy for Haiǁom to go over to the farms Grensplaas and Tsabis (bordering Etosha in the south, and cut off from Etosha in 1947), Tsabis being one of the envisaged resettlement farms (see Chapter 4). Kadisen remembered:

[t]hey went there to work a bit, getting money, buying goats, then they came here again, they lived here, they moved with the goats. Here were not as many elephants [as today], they came from that side. They chased them away. Lions were neither a lot around here, they were more along the pan. They were scarce here. Just the leopards, those were the most here, they caught the goats. The people were also a bit afraid [...]36

When Kadisen and the other team members were showing me !Gobaub, Kadisen intended to visit ǁGauses (another place) as well (unfortunately we did not make it), where in former times, a specific snake had stayed: ‘[t]hat ǁGan!Gub [big snake?], that was the snake [smiling]. They were very afraid of that snake. They said that snake kills the people’. Snakes were mentioned in various contexts and at various places. It was reported that every big water had a water snake, and when the snake died or was killed (as in the case of the waterhole Bikab) the water would dry up. Furthermore, some stories related ‘mythical’ snakes—‘mythical’ because I could not imagine them: there were reports about huge snakes, almost the width of a road. The existence of “Great Snakes” is reported for other Khoe and San peoples, as well as the occurrence of “water snakes”.37 Furthermore, according to some of our team members, snake spirits were among the different ǁgamagu, the spirit beings which populate the world of the Haiǁom and which/who can transfer their potency or spirit to healers/shamans.

Being at !Gobaub, Kadisen and the others also explained which bushfood could be found here. First, they talked about corms: ‘[t]he bushfood here are uintjies [corms/onions?], everything, it is full around here’. Then they mentioned specific drupes, ǂhûin [Berchemia discolor, bird plum]: ‘[t]hey are scarce, they are not a lot around here, but there are some’, which when ripe were collected in large quantities because they could be stored for many months. A variety of Grewia species were also abundant: ‘Sabiron (Grewia villosa), ǂâun (Grewia cf. flava), everything is around here’. Pointing to different directions, Kadisen explained:

ǁnun [Walleria nutans] is also around that side, ûinan [not identified, Cyperaceae, Iridaceae or Tecophilaeceae] is here. That side is ǁnun, ǂhabab [probably Fockea angustifolia], ǂgubub [Cucurbitaceae], […] The people here did not suffer from hunger, they had always a lot of food.

He then continued to discuss the animals and hunting:

!Gobaub was a very important place, all the people, the animals moved here […] Eland were here […] up to ǁHaios [another place with a well]. That is the area of Eland. Suxub and people, they were the Eland people and my grandfather |Nu Aiseb [mother’s father, staying around ǁNububes and ǁNasoneb (Rietfontein)], they are Zebra and Kudu people, they stayed more that side. But my grandfather Suxub is here, he is from the Gemsbok and Eland, they did not think a lot about Zebra, they thought of Eland. Eland are fat, if they have caught an Eland, the whole family is full. They shared with each other when someone had shot an Eland, the whole !Gobaub could eat from it. It must be divided and they have to eat it. […] Not every man needed to shoot his Eland by himself, ehe, no. One is enough for the whole family here, they saved like that. They liked to save, they did not want that the trees are broken, the trees which have food must not be broken, and the hunt as well. You don’t hunt every day just the same side, that the animals become wild […] The people stayed under the side of the wind [?] so that the animals don’t get the smell of the people. They stayed like that with the animals. They did not build their houses everywhere to stay there. Always a bit away from the waterhole as well.

Kadisen went on and explained that Haiǁom would only shoot for the pot, using this as an entry point for some other moral-cultural considerations:

[t]hat is how the Haiǁom are. […] We did not waste, we shot for the pot to cook. When someone killed two animals, they called him and said to him: What is this? Do you just want to kill or do you eat it? You have to stop that! You must not pass the border of another man [...] ǁHaios is again another border [area looked after by another headman], he cannot shoot there, they will punish him a bit. So was life. They were content with the food they could get, they did not quarrel. When the stomach is right, the children had eaten, it is enough, they are content. That is why the Haiǁom are poor today, they are not men who steal or just grab, ehe, no, he is proud, he has to struggle himself to get food, Haiǁom are like that. Until today, we are poor but we are ashamed to grab [gryp].

That is the tradition, you cannot grab, when you are grabbing, the people are looking down on you, they are thinking badly of you. […] Haiǁom are like that. He just wants to be nice, he must be with his children and his wife, they have to eat together and they have to give something to the old people. Haiǁom were like that, they were friendly, they did not have fights/quarrelings […] When the man [a newcomer, stranger] arrives he has to be given so that he can eat, selling was not there. But when you are taking the wife of another man, you will be punished, you have to pay, you have to give some goats for that. Those were the laws, the man who is taking a wife, he gets her forever [vat hom fas] here, […] you take one woman, it is finished, until you die, you just took that one. Not like us today, I have two children of that woman, I have three children of that woman [others laughing], that thing, it does not work with the Haiǁom [in former times], ehe, no, you will be laughed at, you just have to take one woman, that woman is your woman, your children are your children. And you have to try to raise your children, and another man, when he gets big, he takes another woman and raises his children. I can talk badly now, but this year, this year, he takes a woman, he goes to the house of the father of his woman, he lay just down there and eat, and he gets a child. You have raised that daughter and you have to raise the children of her again. Ehe, those things were not happening with the Haiǁom, you have to raise your own children. Yes, that was !Gobaub, and ǁNubes, Rietfontein, Halali, everywhere, Namutoni, all [the other men with us or Haiǁom in general] understand what I say, that was the tradition of the Haiǁom. They have hunted for the stomach, they did not sell it, yeah. [Hans talking Haiǁom]. This time [the interview was taken beginning of September 2001, the start of the rainy season], they started to hunt. They did not hunt meagre things. It had to be fat. When animals were meagre, they have eaten bushfood. They were a bit clever as well, they kept something for the year, the bushfood, they collected it, they kept it. Kudu meat as well. The meat of the winter, June, July, it would last until September, October, the biltong [dried meat]. Old people, they just stamped/crushed it, then they eat it.

15.3.5 ǂKhari Kevis, ǁKhauǂgoab and Aaǂgoab: Tracing a former “chief”

and hunting

ǂKhari Kevis (Klein Okevi), ǁKhauǂgoab and Aaǂgoab (Twee Palms) were part of the area in Etosha that Hans Haneb knew the best. ǂKhari Kevis (Klein Okevi) was a settlement close to |Namob (Namutoni). The mother of Hans Haneb, ǂNangus Anaki Hanes, originated from the Kevis area and was a member of the Tsam family. She died around 1958 at the farm Onguma. Hans’s elder sister |Îninibes Sophia Saries was born about 1926 in the Kevis area. Hans was the second child, born at |Namob (Namutoni) around 1929. His father was based there at the time. His younger sister Elisa |Guri!naes Saries was born in the bush while her mother was looking for bushfood in the Kevis area around 1931. His youngest sister ǁOtwakhoes Olga Saries was also born in the Kevis area two years later as was his youngest brother, ǂOa!kum Adi Haneb, in 1935. He was killed by SWAPO in 1976 whilst working for the South African Defence Force (SADF) tracking “infiltrators” from the north to Okahandja.38

The grave of Fritz !Naob who died in 1945 is situated at ǂKhari Kevis,39 and his family story is worth explaining. In archival documents of the 1930s, a man with the name Fritz Aribib, son of “Captain Aribib” was often mentioned as one of the Haiǁom “leaders”. As mentioned in Chapter 1,

the German colonial government concluded a treaty with Captain Aribib at the end of the 19th century. From “a Haiǁom perspective”, however, it seems that Aribib could not have signed such a contract because it contravened the Haiǁom social system, according to which respected elderly men or women had only responsibility in the small areas and the family groups they were closely connected to: a hierarchical leadership structure beyond this level was non-existent.

In the beginning, the Haiǁom core team members, being asked about Fritz Aribib or his father Captain Aribib, first said they never heard of them. Later, after some internal discussions, they came up with the answer that Captain Aribib must have been the man Fritz ǂArixab and that his son must have been Fritz !Naob (surname from his mother), who worked for the police at Tsumeb (a town east of Etosha) and also learned reading and writing. At the end of his life, he stayed at ǂKhari Kevis and died there. He had been a respected person and possessed some livestock. He had a mediator position also in negotiations regarding the eviction but was not regarded as the headman of the area, since he originated from an area further south, around the town Otavi. When Hans, Willem and Kadisen talked about him, they also explained part of the who-is-who in his family relations, his wife, mother-in-law, daughter, etc. They also explained that Captain Aribib was family with ǁKhumus.40 The old surname Aribib (or |Aribib) was changed or hidden since the time of the German-Herero war, reportedly, because Captain Aribib was seen as an ally of the Germans.

When Hans Haneb was a child, he often visited his kin at ǁKhauǂgoab and Aaǂgoab (Twee Palms) (see Figure 15.7). When visiting we found many remains left by former inhabitants, including a piece of an oven, pieces of broken glass, metal remains and a meat stamping stone. Hans explained that the two waterholes were brothers. Aaǂgoab was the waterhole to drink from (aa means ‘to drink’) as its water was superior to that of ǁKhauǂgoab. ǁKhauǂgoab was the waterhole to hunt at (ǁkhau means ‘to shoot with an arrow’, ǂgoab means ‘mud’). The water was too salty for human consumption. Haiǁom hunters used to wait in !goasa (hunting shelters at waterholes or animal paths) for the animals to come and drink. The settlement was situated between the two waterholes. The Haiǁom from this settlement also went to |Namob (Namutoni) to visit people there and to collect berries, mainly ǂhûin (Berchemia discolor, bird plum), in that area. During these visits, Hans was taught by the older, experienced hunters how to hunt at ǁKhauǂgoab.

Fig. 15.7 ǁKhauǂgoab (Twee Palms) on left. Photo: © Harald Sterly, 2002. On right, Hans Haneb demonstrating how to use bow and arrow. Photo: © James Suzman, 2002. Both photos are part of the Xom |Omis Project, and are used with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Hans could recall many hunting experiences that took place at ǁKhauǂgoab. Once, he wanted to shoot a kudu, but he became so tired that he fell asleep while he was waiting for one. When he awoke, he was looking straight into the eyes of a kudu, and at first, was too surprised to react and shoot. Once he had recovered, he shot the kudu with a poisoned arrow, and it ran away. The following morning, he and some others tracked it and found it where it had died. They cut up the carcass and brought the meat back to the settlement. On another occasion, he went to ǁKhauǂgoab to wait for prey in a !goas. The next morning, a wildebeest approached from the side. In order to give the headman of the area the opportunity to shoot it, Hans held back, but the animal got the wind of the old man and started to run away. At that point, Hans put practical considerations ahead of courtesy and shot it dead.

15.4 Places as knots, Etosha as meshwork

Following the threads evolving around specific places, I attempted to (re-)vitalise the former lifeworld of Haiǁom in Etosha.

More than any other place, ǂAro!gara!garases signifies the idea of ‘walking through places’, vividly illustrating what living in Etosha entailed. It was a place to rest while moving, not a place to stay at for too long.

Through Tsînaib and Willem, we traced the vast kinship-spatial knowledge of Haiǁom woven into the landscape; kinship networks are engrained in the landscape or—put differently—spatial knowledge is “relational” knowledge.41 People and land/places were connected and personal identities belonged to the land. Kinship ties implied spatial connections and guided movements. They did establish common ground. Areas from which parents originated were regarded as ‘our’ place, which included that one could go and stay there for some time. In Willem’s example, it could also be a stepfather. Willem’s example also clarified that one could stay at the places of one’s parent’s cross siblings. In areas where close kinship of this kind could not be established as easily, one would need to show respect to the fact that one had entered the ground of someone else (e.g. in terms of asking permission to give some of the killed game to the elders there).

The pair of hills ǁKhumub and |Nuaiseb led us to specific headmen responsible for the area, their roles for the family group and bushfood to be found.

!Gobaub points to the close connection of people, land and mobility. Although Kadisen was born at a settlement close to another water hole in Etosha (where his mother’s father was staying with his family), this place was one he used to visit and where he temporarily stayed during his childhood, as his father’s father was living at !Gobaub with extended family. The remarks on surnames of people also inhabiting the area point to the relations of family groups to areas. Socio-spatial arrangements concerning settlement locations and hunting areas were described; the connections of areas, people and animals (e.g. the “Eland people”) revealed; and hunting and sharing practices, bushfood occurrence, hunting and consumption morals, were remarked upon. The origin of the waterhole and the involvement of a shaman/healer (!gaiob) was explained and the history of the area was embedded in the account (the farms at the border and the temporal farm work). Kadisen also alluded to a special snake.

The other places, ǂKhari Kevis (Klein Okevi), ǁKhauǂgoab and Aaǂgoab (Twee Palms) also point to the close connection of people and places. This was the home area of Hans Haneb, who remembered his childhood and learning hunting at these places. The place also leads to the early colonial past with the grave of Fritz !Naob. The remains we found there give evidence of past human dwelling in the area.

All these places lead to specific persons, and beings-beyond-the-human (e.g. animals or ancestors); they lead to other places and other people, they lead to the past. Ingold states that,

[p]laces, then, are like knots, and the threads from which they are tied are lines of wayfaring. A house, for example, is a place where the lines of its residents are tightly knotted together. But these lines are no more contained within the house than are threads contained within a knot. Rather, they trail beyond it, only to become caught up with other lines in other places, as are threads in other knots. Together they make up what I have called the meshwork.42

Ingold’s “meshwork” is a suitable concept for capturing Haiǁom’s being-in-Etosha as being-in-relations. The meshwork concept is linked to Ingold’s reading of ‘animacy’ as ‘the dynamic, transformative potential of the entire field of relations within which beings of all kinds, more or less person-like or thing-like, continually and reciprocally bring one another into existence’.43 He stresses two points of an ‘animic perception of the world, […] the relational constitution of being; […] and the primacy of movement’.44 The meshwork is the lifeworld constituted of organisms in a relational field, and organisms are trails of movement and growth and not entities set off against the environment. The environment, he envisages, is ‘a domain of entanglement’:

[t]his tangle is the texture of the world. In the animic ontology, beings do not simply occupy the world, they inhabit it, and in so doing—in threading their own paths through the meshwork—they contribute to its ever-evolving weave. Thus we must cease regarding the world as inert substratum, over which living things propel themselves about like counters on a board or actors on a stage, where artefacts and the landscape take the place, respectively, of properties and scenery. By the same token, beings that inhabit the world (or that are truly indigenous in this sense) are not objects that move, undergoing displacement from point to point across the world’s surface. Indeed the inhabited world, as such, has no surface […], whatever surfaces one encounters, whether on the ground, water, vegetation or building, are in the world, not of it […] And woven into their very texture are the lines of growth and movement of its inhabitants. Every such line, in short, is a way through rather than across. And it is as their lines of movement, not as mobile, self-propelled entities, that beings are instantiated in the world. […] The animic world is in perpetual flux, as the beings that participate in it go their various ways.45

In tracing the lines evolving around places a dense web of land, kinship, humans, animals, plants and spirit beings emerges: an integrated ecology, an almost forgotten past. More than only the physical paths in the landscape, I refer to the “intangible” (i.e. “memorial”/mental/psychological/cognitive/spiritual) threads emerging when visiting these places with the former inhabitants. What Nelson stated for the Kokuyun is also true for Haiǁom formerly living in Etosha:

[t]he […] homeland is filled with places […] invested with significance in personal or family history. Drawing back to view the landscape as a whole, we can see it completely interwoven with these meanings. Each living individual is bound into this pattern of land and people that extends throughout the terrain and far back across time.46

The places walked through above show histories and identities woven into places; the land itself ‘is pregnant with the past’.47 The story of origin—the ‘bursting’ of the waterhole !Gobaub—is connected to the very place. The occurrence and seasonality of bushfood and game are connected to places and woven into the land. Colonial history is part of it too as is the gradual change of livelihood options (Haiǁom men went to farms for temporal employment) or the tracing of the former ‘chief’. The graves of deceased Haiǁom are kinship ties across generations engrained in the landscape.

Travelling through places with Haiǁom brought up numerous stories, oral histories and personal memories, e.g. about conflicts with other groups, about specific individuals, both human and beyond-the-human, about kudu or ǁgamagu (spirit-beings). New stories and new memories have been constantly woven into the land. Even the reminiscence of the eviction became integrated into specific places, where the Haiǁom were gradually assembled and eventually ordered by the colonial representatives to leave the park.48

Haiǁom in Etosha entertained a variety of relations with the land, kin, ancestors and other beings. These relations were constitutive of their being, or in Bird-David’s words:

[a]gainst “I think, therefore I am” stand “I relate, therefore I am” and “I know as I relate.” Against materialistic framing of the environment as discrete things stands relationally framing the environment as nested relatednesses. Both ways are real and valid. Each has its limits and its strengths.49

Relationships with space established identities, as did relationships with people and animals. In the former lifeworld of the Haiǁom, there was no strict boundary between the natural and the supernatural, material and spiritual, the real and the mythical, or between animated and unanimated beings. By the same token, their connection to the land is not appositely captured as “ownership” in the sense of exclusive rights over the land. Ownership in this sense was/is not possible in Haiǁom-Etosha-ecology. Experiencing oneself as part of a wider ecology with diverse beings, rather than as controllers of “nature”, prevents ideas of (exclusively human) ownership in the same way as egalitarian values prevent the establishment of formal, hierarchical leadership structures (see Chapter 4).50 Although the boundaries of family-group areas were well known to the Haiǁom, and sometimes also marked with beacons (e.g. rocks put in trees), the existence of these outlined areas is not proof of exclusive ownership or exclusive rights to access. Instead, they were socially permeable.51 It is rather an indication that family groups were tied to specific patches of land and had guardianship of the area. Apart from the living elders, ancestors also took care of the land.

15.5 The meshwork of Etosha, untied and confined

The Etosha area52 was thus a meshwork of which Haiǁom—as human inhabitants—were a vital part. In other words, they were integral threads, as were spirit-beings and ancestors, predators, prey animals, livestock, trees, shrubs and other plants. Haiǁom knew how to sustainably live there, as Kadisen stressed at !Gobaub: ‘[w]e did not waste’.53 Taboo rules of various kinds (e.g. concerning food or behaviour) were in place. Headmen or women were responsible for checking and deciding which bushfood could be collected at which place, and which animals could be hunted in which area. For serious problems and transgression of laws or taboos, !gaiogu (shamans/healers) had to communicate and negotiate with ǁgamagu (spirit beings) who supervised and looked after the area in order to find solutions.

As mentioned in Chapter 2, up to the 1940s, Haiǁom were also perceived by “outsiders”—above all representatives of the colonial administration, but also by white settlers—as “part and parcel” of Etosha. The native commissioner of Ovamboland, Major Hahn, who was responsible for the Game Reserve, reported in 1936:

I beg to remark that wild bushmen have always been allowed to reside in the Game Reserve. They are considered as part and parcel of it. They are allowed to shoot certain species of game only and these may not be shot or trapped near watering places [...]54

Their hunting was generally not seen as a threat to the ecological balance within the area: “to shoot for the pot” (with bow and arrow) was accepted by the colonial officers.

The concept of meshwork also allows for changes, for new weaving, gradual transformations and a more differentiated picture. During the first part of the 20th century, new threads became woven into the meshwork. In addition to hunting and gathering, many families possessed livestock: especially goats, but also a few head of cattle and donkeys. Furthermore, Haiǁom men had several opportunities for seasonal or regular work, either inside or outside Etosha, on farms, in mines or road construction or at the police stations of Okaukuejo and Namutoni.55 As Etosha was not yet fenced, however, Haiǁom men could return to their families and the places they belonged to.

From the late 1940s onwards, the former meshwork underwent serious changes due to the ideals and practices of the colonial administration (see Chapters 2 and 4). These had significant impacts on Haiǁom. In the early 1950s, they were evicted from their living places in Etosha. They became labour “material”, a few at the rest camps and most at the commercial farms owned by white settlers. Immediately after the eviction, though, many Haiǁom were not aware that there was no return for them. Only after a while, they began to realise that things had indeed changed and that moving back and forth was no longer either a legal or a tolerated strategy. For those few Haiǁom who later found employment within Etosha, the maintenance of relations to the land and its beings could be continued, although differently to before. Being employed in Etosha allowed them to stay on the land, yet not anymore at the waterholes but at the police stations/rest camps.56 Maybe one could regard this employment as a new thread being woven into the meshwork.

Etosha was gradually reduced in size and fenced in, first at the southern border, dividing the home area of Haiǁom and hampering their movement. Recalling the time after the eviction in an interview, Kadisen explained:

[t]he fence is now put up. The gate is there now. We came there, they said, no, you are not coming in anymore. Who is on that side, stay on that side. Who is inside, stay inside. We were lucky. We [his family] came in before the fence was put up. That time we were already here. And the people who stayed behind, they came there, the gate was there, it was said, no, you should not come, you will stay outside, you are not coming in anymore.57

Only those looking for employment were allowed to get back in (when workers were needed).

The evicted Haiǁom became involuntarily deprived of their previous relations to their former places and their former beyond-human companions there. The eviction, therefore, is more than just relocation and more than mere land dispossession. It is a social deprivation, as relations to places and beyond-the human beings were interrupted. The fencing of the park had critical consequences both for Haiǁom and for the wildlife populations of the area (see Chapters 2 and 10),58 lions being welcomed to keep some predator-prey balance while Haiǁom were evicted as “game exterminators”.59

The former meshwork became untied and confined, officially in the name of nature conservation but in fact in a specific way of nature commercialisation: game in “protected areas” became a commodity in the production line of “Africa, the untamed wilderness” to be sold to tourists, while former human inhabitants were excluded from this line. A huge amount of (colonial) management and a “scientification” of “nature conservation” became necessary to maintain this “imagined wilderness” (see Chapter 2). The former meshwork of Etosha as the home of human and beyond-the-human inhabitants, of places conveying the very history of the area, had dissolved, and the past became (almost) forgotten.

15.6 Alternative visions for conservation and beyond? Thinking with relations, thinking with Haiǁom

Through places, people and stories, I have conveyed an image of the Etosha area as the former lifeworld of the Haiǁom, which can be comprehended as a meshwork with “place-knots”, with threads of human inhabitants, spirit-beings and ancestors, predators, prey animals, livestock, trees, shrubs and other plants. Not only humans were animated and agents, but also animals, ancestors, and spirit-beings. These elements or beings were mutually dependent. They shared places, they shared food or water, nurtured each other, all of them part of the ecology. I showed that the meshwork concept also opens a new perspective on the eviction of Haiǁom, comprehending it as social deprivation and not solely relocation. Yet, I argue that this conceptualisation should not stop at the borders of today’s Etosha, or when leaving the past lifeworld of Haiǁom. We could take it, as Ingold suggested in general terms more than two decades ago, as a starting point for our60 own engagement with the environment:

I am suggesting that we rewrite the history of human-animal relations, taking this condition of active engagement, of being-in-the world, as our starting point. We might speak of it as a history of human concern with animals, insofar as this notion convey a caring, attentive regard, a “being with”. And I am suggesting that those who are “with” animals in their day-to-day lives, most notably hunters and herdsmen, can offer us some of the best possible indications of how we might proceed.61

Thereby, I would not confine this kind of apprehension to human-animal relations but extend it to other elements/beings within the environment too.

I hope that ‘walking through places’—through introducing the former lifeworld of the Haiǁom—transmits the idea/experience62 of “being-with” and in-the-world, thus deviating from anthropocentric cosmologies that assume a being-on-top-of-the-rest. The Australian philosopher Val Plumwood identified two tasks in face of the current ecological crisis: first, to (re)situate the human in ecological terms, and second, to (re)situate non-humans in ethical terms.63 To my point of view, the former lifeworld of the Haiǁom provides hints as to what this could entail. This should not be understood as promoting a return to a hunting-and-gathering way of life but rather as a suggestion to relate differently with our “environment”. It allows for the (re-)animation of “nature” based on mutual respect and relationality. The objectification of nature, originating in the “Enlightenment”64 and a central characteristic of “Modernity”65 is arguably an important cause of current ecological crisis. Technology on its own, deeply embedded in modernity’s premises, will not bring salvation.66 What is needed, is a “relational turn”,67 not only in science but in nature conservation and our approach to life.

We could also take this “relating-to” and “being-with” as a guiding principle for future nature conservation policies and practices. On other continents and in other regions, the ideas/experiences of Indigenous peoples—resulting in particular environmental knowledges—are more actively promoted by Indigenous scholars68 and integrated into discussions on environmental issues and climate change.69 Their ways of being-in-the-world are therefore at times included in conservation planning, environmental management, reparation measures and legislation.70 Yet, in southern Africa, especially in Namibia, Indigenous people—and in particular San communities—are struggling with the establishment of recognised and influential political organisations, as well as discrimination based on disparaging their (former) ways of life. The notion that the San traditional way of life is a “primitive” way of life and that the San need to be “civilised” is prevalent among Namibians generally, including the government.71

Hence, the values and ways-to-relate within Namibian Indigenous communities seem disregarded within Namibian society and politics: their ideas/experiences originating in their former “being-in-the-world” have not entered the arena of conservation discourse. This is not only true in the context of reparation for colonial wrongs of conservation practices and resulting land dispossession (see Chapters 4, 12, 13, 14 and 16) but also concerning future conservation efforts. Some might note that Namibia’s Community-Based Resource Management Programme (CBNRM, see Chapter 3), emphasises local involvement in conservation issues and thereby goes in the proposed direction. Given its grounding in ideas of rural development based on an economic-progress paradigm and concerns about the protection of wildlife (grounded in the conviction that economic benefits serve as incentives to protect wildlife), ‘cultural and historical dimensions of land-use and value [have] remain[ed] relatively weakly entangled with conservation concerns’.72 CBNRM instead appears embedded in a particular ‘worlding’ that is anthropocentric, utilitarian and objectifying with a clear culture-nature dualism.73 As Schnegg and Kiaka note,

CBNRM devalues lifeworlds and worldviews that have been shaped over centuries through specific ways of being. Thus, right from the start, CBNRM fails to recognize that people may have other ways of being-in-the-world than what the modernization paradigm of CBNRM implies.74

Moreover, the programme promotes institutional blueprints to be used for community-driven nature conservation, blueprints which barely take histories and former institutions, social structures and ways of decision-making, into consideration (see Chapter 7).

Several scholars have already connected ontological/phenomenological Indigenous case studies from Namibia with conservation and environmental issues.75 I argue that it is also time for Namibia’s Indigenous being-in-the-world to be integrated more firmly into the discourse on Namibia’s conservation politics and practices. Imagine that Haiǁom experiences of their surroundings (as that of other Indigenous peoples in Namibia), their ideas of their place/position in relation to human and other-than-human beings and their acknowledgement of the importance of mutual relationships between a variety of human and non-human actors could find their ways in the Namibian conservation discourse. It would open the possibility that humans may be re-positioned with regards to ecology.

The need for humans to conserve nature focused on the sustainability of human existence embedded in a ‘utilitarian, exploitative, dominion-over-nature worldview’76 could be replaced with the responsibility of humans to care for the whole ecosystem (including humans). It would mean that humans do not need to be separated from nature to conserve it. A (re-)animation of nature would mean that the maintenance of ethical and mutual relationships with non-human others would become a necessity of living(-with). It would also imply that local knowledge should be integrated into the management of protected areas, including national parks.77 Taking Haiǁom (and other) concepts/experiences seriously in the Namibian context could also result in some of the other beings or even relations becoming legal persons in the Namibian jurisdiction. This is the case in other countries already: for example, the constitution of Ecuador grants inalienable, substantive rights to nature.78 In New Zealand, a river system gained legal personhood based on Māori onto-epistemologies.79 New Zealand also granted legal personhood to national parks. In Australia, following Ngarrindjeri negotiations with the government, the environment became a recognised water user to be prioritised.80

Integrating Haiǁom and other Indigenous onto-epistemologies in the Namibian conservation discourse would open a variety of alternative paths to be further explored. It would be without doubt a significant step to more empowerment and more participation of Indigenous peoples in Namibia, to more environmental justice and decolonisation of development.81 It would also be a step to decolonise conservation and to the reconciliation of conservation efforts with diverse human (and non-human) actors.

Archive sources

NAO 33/1, 14.11.1936: Native Commissioner Ovamboland to the Secretary for SWA.

Bibliography

Basso, K.H. 1996. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Berry, H.H. 1997. Historical review of the Etosha region and its subsequent administration as a National Park. Madoqua 20(1): 3–10, https://hdl.handle.net/10520/AJA10115498_453

Bird-David, N. 1999. ‘Animism’ revisited: Personhood, environment, and relational epistemology. Current Anthropology 40, Suppl.: S67–S79, https://doi.org/10.1086/200061

Black, C.F. 2011. The Land is the Source of the Law: A Dialogic Encounter with Indigenous Jurisprudence. London: Routledge.

Blaser, M. 2009. The threat of the Yrmo: The political ontology of a sustainable hunting program. American Anthropologist 111(1): 10–20, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2009.01073.x

Blaser, M. 2013. Ontological conflicts and the stories of peoples in spite of Europe. Current Anthropology 54(5): 547–68, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/672270

Burman, A. 2017. The political ontology of climate change: Moral meteorology, climate justice, and the coloniality of reality in the Bolivian Andes. Journal of Political Ecology 24: 921–38, https://doi.org/10.2458/v24i1.20974

Cochran, P., Huntington, O.H., Pungowiyi, C., Tom, S., Chapin, F.S., Huntington, H.P. et al. 2013. Indigenous frameworks for observing and responding to climate change in Alaska. Climatic Change 120(3): 557–67, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-013-0735-2

Cruikshank, J. 2012. Are glaciers ‘good to think with’? Recognising Indigenous environmental knowledge 1. Anthropological Forum 22(3): 239–50, https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2012.707972

de la Cadena, M. 2010. Indigenous cosmopolitics in the Andes: Conceptual reflections beyond ‘politics’. Cultural Anthropology 25(2): 334–70, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01061.x

Dépelteau, F. 2015. What is the direction of the ‘Relational Turn’? In Powell, C. and Dépelteau, F. (eds.) Conceptualizing Relational Sociology: Ontological and Theoretical Issues. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 163–85, https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137342652_10

Dieckmann, U. 2003. The impact of nature conservation on the San: A case study of Etosha National Park. In Hohmann, T. (ed.) San and the State: Contesting Land, Development, Identity and Representation. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, 37–86.

Dieckmann, U. 2007. Haiǁom in the Etosha Region: A History of Colonial Settlement, Ethnicity and Nature Conservation. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Dieckmann, U. 2009. Born in Etosha: Homage to the Cultural Heritage of the Haiǁom. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre.

Dieckmann, U. 2012. Born in Etosha: Living and Learning in the Wild. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre.

Dieckmann, U. 2021a. Haiǁom in Etosha: ‘Cultural maps’ and being-in-relations. In Dieckmann, U. (ed.) Mapping the Unmappable? Cartographic Explorations with Indigenous Peoples in Africa. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 93–137, https://www.transcript-open.de/doi/10.14361/9783839452417-005

Dieckmann, U. 2021b. Introduction: Cartographic explorations with indigenous peoples in Africa. In Dieckmann, U. (ed.) Mapping the Unmappable? Cartographic Explorations with Indigenous Peoples in Africa. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 9–46, https://www.transcript-open.de/doi/10.14361/9783839452417-002

Dieckmann, U. 2021c. On ‘climate’ and the risk of onto-epistemological ‘chainsaw massacres’: A study on climate change and Indigenous people in Namibia revisited. In Böhm, S. and Sullivan, S. (eds.) Negotiating Climate Change in Crisis. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 189–205, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0265.14

Dieckmann, U. 2023. Thinking with relations in nature conservation? A case study of the Etosha National Park and Haiǁom. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 29(4): 859–79, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.14008

Dieckmann, U. and Dirkx, E. 2014. Culture, discrimination and development. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 503–22.

Enns, E. and Littlechild, D. 2018. We Rise Together. Achieving Pathway to Canada Target 1 Through the Creation of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas in the Spirit and Practice of Reconciliation. Canada: The Indigenous Circle of Experts, https://shawanagaislandipca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ICE-Report.pdf

Friederich, R. 2009. Verjagt…Vergessen…Verweht… Die Haiǁom und das Etoscha Gebiet. Windhoek: Macmillan Education Namibia.

Goldman, M.J., Daly, M. and Lovell, E.J. 2016. Exploring multiple ontologies of drought in agro-pastoral regions of Northern Tanzania: A topological approach. Area 48(1): 27–33, https://www.jstor.org/stable/24812191

Hannis, M. and Sullivan, S. 2018. Relationality, reciprocity and flourishing in an African landscape. In Hartman, L.M. (ed.) That All May Flourish: Comparative Religious Environmental Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press, 279–96, https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190456023.003.0018

Hoff, A. 1997. The water snake of the Khoekhoen and |Xam. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 52(165): 21–37.

Hoole, A. and Berkes, F. 2010. Breaking down fences: Recoupling social-ecological systems for biodiversity conservation in Namibia. Geoforum 41(2): 304–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.10.009

Ingold, T. 2011[2000]. The Perception of the Environment. Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge.

Ingold, T. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. London: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003196679

Low, C. 2007. Khoisan wind: Hunting and healing. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13: S71–S90, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9655.2007.00402.x

Muller, S., Hemming, S. and Rigney, D. 2019. Indigenous sovereignties: Relational ontologies and environmental management. Geographical Research 57(4): 399–410, https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12362

Nelson, R.K. 1983. Make Prayers to the Raven: A Koyukon View of the Northern Forest. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Peters, J., Dieckmann, U. and Vogelsang, R. 2009. Losing the spoor: Haiǁom animal exploitation in the Etosha region. In Grupe, G., McGlynn, G. and Peters, J. (eds.) Tracking Down the Past: Ethnohistory Meets Archaeozoology. Rahden/Westf.: Leidorf, 103–85.

Plumwood, V. 2002. Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason. London: Routledge.

Salmond, A. 2012. Ontological quarrels: Indigeneity, exclusion and citizenship in a relational world. Anthropological Theory 12(2): 115–41, https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499612454119

Salmond, A. 2014. Tears of Rangi. Water, power, and people in New Zealand. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4(3): 285–309, https://doi.org/10.14318/hau4.3.017

Schnegg, M. 2021. What does the situation say? Theorizing multiple understandings of climate change. Ethos 49(2): 194–215, https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12307

Schnegg, M. and Kiaka, R.D. 2018. Subsidized elephants: Community-based resource governance and environmental (in)justice in Namibia. Geoforum 93: 105–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.05.010

Sullivan, S. 1999. Folk and formal, local and national: Damara cultural knowledge and community-based conservation in southern Kunene, Namibia. Cimbebasia 15: 1–28.

Sullivan, S. 2002. How sustainable is the communalising discourse of ‘new’ conservation? The masking of difference, inequality and aspiration in the fledgling ‘conservancies’ of Namibia. In Chatty, D. and Colchester, M. (eds.) Conservation and Mobile Indigenous People: Displacement, Forced Settlement and Sustainable Development. Oxford: Berghahn Press, 158–87, https://doi.org/10.1515/9780857456748-008

Sullivan, S. 2010. ‘Ecosystem service commodities’—a new imperial ecology? Implications for animist immanent ecologies, with Deleuze and Guattari. New Formations: A Journal of Culture/Theory/Politics 69: 111–28, https://siansullivan.files.wordpress.com/2010/02/animist-immanent-ecologies-sullivan-new-formations-2010.pdf

Sullivan, S. 2013. Nature on the Move III: (Re)countenancing an animate nature. New Proposals: Journal of Marxism and Interdisciplinary Enquiry 6(1-2): 50–71, https://ojs.library.ubc.ca/index.php/newproposals/article/view/183771

Sullivan, S. 2017. What’s ontology got to do with it? On nature and knowledge in a political ecology of ‘the green economy’. Journal of Political Ecology 24: 217–42, https://doi.org/10.2458/v24i1.20802

Sullivan, S. 2022. Maps and memory, rights and relationships: Articulations of global modernity and local dwelling in delineating land for a communal-area conservancy in north-west Namibia. Conserveries Mémorielles: Revue Transdisciplinaire 25, https://journals.openedition.org/cm/5013

Sullivan, S. and Ganuses, W.S. 2021. Densities of meaning in west Namibian landscapes: Genealogies, ancestral agencies, and healing. In Dieckmann, U. (ed.) Mapping the Unmappable? Cartographic Explorations with Indigenous Peoples in Africa. Bielefeld: Transcript, 139–90, https://www.transcript-open.de/doi/10.14361/9783839452417-006

Sullivan, S., Hannis, M., Impey, A., Low, C. and Rohde, R. 2016. Future Pasts? Sustainabilities in West Namibia—a Conceptual Framework for Research. Future Pasts Working Paper Series 1 https://www.futurepasts.net/fpwp1-sullivan-et-al-2016

Sullivan, S. and Low, C. 2014. Shades of the rainbow serpent? A KhoeSān animal between myth and landscape in southern Africa—ethnographic contextualisations of rock art representations. The Arts 3(2): 215–44, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/3/2/215

Suzman, J. 2004. Etosha dreams: An historical account of the Haiǁom predicament. Journal of Modern African Studies 42: 221–38, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X04000102

Umeek, R.A.E. 2014. Principles of Tsawalk. An Indigenous Approach to Global Crisis. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, https://doi.org/10.59962/9780774821285

Wagner-Robertz, D. 1977. Der Alte hat mir erzählt: Schamanismus bei den Hainǁom von Südwestafrika. Eine Untersuchung ihrer geistigen Kultur. Swakopmund: Gesellschaft für Wissenschaftiliche Entwicklung und Museum Swakopmund.

Widlok, T. 1999. Living on Mangetti: ‘Bushman’ Autonomy and Namibian Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Widlok, T. 2009. Where settlements and the landscape merge. In Bollig, M. and Bubenzer, O. (eds.) African Landscapes. Interdisciplinary Approaches. New York: Springer, 407–27, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-78682-7_15

Wildcat, D.R. 2013. Introduction: Climate change and indigenous peoples of the USA. Climatic Change 120(3): 509–15, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-013-0849-6

1 I have explored similar issues, but partly with other concepts, terminology and examples, in Dieckmann (2023). See also Dieckmann (2021a).

2 Suzman (2004: 223)

3 With “Being-in”, I follow Ingold’s (2011[2000]) use of the term.

4 This research was funded by the German Research Foundation (project number DI 2595/1-1) and undertaken within the framework of the DFG-AHRC project Etosha-Kunene-Histories (https://www.etosha-kunene-histories.net/); fieldwork was carried out within the framework of the Collaborative Research Centre 386, also funded by the German Research Foundation. The former Ministry of Environment and Tourism in Namibia supported my work with research permits for the Etosha National Park.

5 Basso (1996)

6 Also see Sullivan and Ganuses (2021) for a similar application of Basso’s framing for Damara/ǂNūkhoe place-making in north-west Namibia.

7 Basso (1996: 14)

8 E.g. Ingold (2011[2000])

9 Dieckmann (2007)

10 The donors of the Etosha mapping project (Open Channels and Comic Relief, UK) and mapping company (Strata 360, Canada) had been involved in a similar mapping and documentation project in South Africa, with San who had lived dispersed and dispossessed for centuries and who had become known as ǂKhomani during court case preparations in the 1990s. In the ǂKhomani project, mapping took place in and adjacent to the Kalahari Gemsbok Park, amalgamated with the Gemsbok National Park in Botswana in 2000 to become the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park.

11 Namely: James Suzman, Cambridge University, anthropologist; Harald Sterly, University of Cologne, geographer; Ralf Vogelsang, University of Cologne, archaeologist; Joris Peters, University of Munich, archaeo-zoologist; Barbara Eichhorn, University of Cologne, archaeo-botanist.

12 The legal entity envisaged to drive the project on the long-term was a Community Trust. The preparations for establishment of the trust and the formulation of the trust deed were undertaken in close cooperation with the Legal Assistance Centre (LAC) in Windhoek and with Haiǁom elders who had participated in the research serving as the Board of Trustees. The trust was established in 2009, but never came into full operation as three of the four main drivers of the project, Haiǁom elders Hans Haneb, Kadison ǁKhumub and Jacob ǁOreseb, passed away.

13 Sullivan et al. (2016: 22), Sullivan & Ganuses (2021), Sullivan (2022: 2–5)

14 Peters et al. (2009)

15 For a critical assessment of the maps see Dieckmann (2021a)

16 Dieckmann (2009)

17 Dieckmann (2012)