16. History and social complexities for San at Tsintsabis resettlement farm, Namibia

©2024 Stasja Koot & Moses ǁKhumûb, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0402.16

Abstract

The theme of the 1950s eviction of Haiǁom Indigenous people from the protected area that became Etosha National Park is continued in this chapter. After this event, many Haiǁom San became farm workers. Having lost their lands under colonialism and apartheid to nature conservation and large-scale livestock ranching, most remained living in the margins of society at the service of white farmers, conservationists or the South African Defence Force. After Independence in 1990, group resettlement farms became crucial to address historically built-up inequalities by providing marginalised groups with opportunities to start self-sufficient small-scale agriculture. This chapter addresses the history of the Tsintsabis resettlement farm, just over a 100 kms east of Etosha National Park, where at first predominantly Haiǁom (and to a lesser degree !Xun) were “resettled” on their own ancestral land, some as former evictees from the park. The history of Tsintsabis is analysed in relation to two pressing, and related, social complexities at this resettlement farm, namely: 1) ethnic tension and in-migration; and 2) leadership. The chapter argues that the case of Tsintsabis shows the importance of acknowledging historically built-up injustices when addressing current social complexities. The importance of doing long-term ethno-historical research about resettlement is thereby emphasised so as to be able to better understand the contextual processes within which resettlement is embedded.

16.1 Introduction

Resettlement has been an important pillar of the Namibian land reform programme, since prior to Independence in 1990. One important aim of resettlement was to develop marginalised rural populations.1 This emphasis arises because ‘Namibia has one of the most unequal distributions of land […] in the world, and this inequality in access and control over land is […] a major cause of rural poverty, socioeconomic inequalities, and social dissatisfaction’:2 Chapters 1 and 2 provide historical contexts giving rise to this situation.

Resettlement in Namibia, therefore, functions as a crucial development instrument. The main legal document to address land inequalities is the Agricultural (Commercial) Land Reform Act, 6 of 1995 (ACLRA).3 In the National Land Policy (NLP) from 1996, the primary objectives were ‘to provide adequate access to land for landless people’ and ‘to promote, facilitate and coordinate access to, and control over, land […] to support long-term sustainable development for all Namibians’.4 Resettlement was thus crucial to achieve these goals. Specified in the National Resettlement Policy of 2001, Namibia identified the following target groups for resettlement: the San5 population, displaced people, returnees, ex-combatants, ex-farm workers, destitute and landless people, disabled people and those living in overcrowded communal areas.6 The objectives of resettlement are to redress past imbalances in the distribution of land; to make people self-sufficient through agriculture; to integrate resettled populations into the national economy; to create income-generating activities; to reduce livestock and human pressure on communal lands; and to provide resettled peoples an opportunity to reintegrate into society.7

Based on their marginalised status and a history of discrimination and exploitation, the government thus made the San of Namibia one of the main target groups of its resettlement policy (also see Chapter 4).8 However, only a few of them were able to secure access to resettlement land or resources to be able to carry out development activities on this land.9 By 2010, over 55 group resettlement projects had been established by the then Ministry of Lands and Resettlement (MLR), of which at least 23 contained significant numbers of San.10 Most of them were directed to group resettlement farms that contained many deficiencies, including a lack of (proper) infrastructure, low farming capacities of the beneficiaries, and poor suitability of the land. Furthermore, environmental assessments tended to be poorly done, coordinators of the MLR were often not properly qualified, and beneficiaries did not have official certificates for leasing a piece of land, leading to most resettlement projects failing national production objectives.11

Much literature has addressed resettlement policies and practices and related legal frameworks in Namibia (including the analysis in Chapter 4).12 In this chapter we divert from a legal focus and contribute an analysis of the historical development of social complexities at one specific resettlement farm, namely Tsintsabis. Our aim is to better understand why resettlement often continues to show limited and disappointing results more than 30 years after implementation.13 In our analysis, we focus on San inhabitants of the area, namely, Haiǁom and to a lesser degree !Xun, and their relations with other peoples and each other. We focus on two specific social complexities: namely 1) ethnic tension and in-migration; and 2) leadership.

Social complexities ‘will always influence the ways that local people understand, respond to, and are impacted by […] projects, and hence social complexity should be taken into account when the planning, implementation, and outcomes of […] projects are considered’.14 Whilst there is increasing acknowledgement that people are part of much larger networks in which the total environment, including non-human elements, is important for understanding lifeworlds,15 our specific focus here is on human interactions, relations and activities. Since social complexities ‘demonstrate how the planning, implementation, and impacts’ of policies and/or projects can ‘have different effects for different groups of people’,16 this focus allows us to concentrate on issues that concern the Haiǁom and !Xun of Tsintsabis. We analyse how ethnic tension, in-migration, and leadership issues have developed historically at the Tsintsabis resettlement farm and how they have impacted—and continue to impact—Haiǁom and !Xun living there.

In the remainder of this chapter we describe our methodology, following this with a more detailed history of land dispossession among the Haiǁom of northern Namibia. Next, we zoom in on the Tsintsabis resettlement farm, its history and two contemporary social complexities, as mentioned above. These two social complexities—namely ethnic tensions and in-migration, and disputes around leadership—are at the core of this chapter and have been controversial in Tsintsabis since its establishment as a resettlement farm. Lastly, in our conclusion we reflect back on the process of resettlement for Haiǁom more generally and in Tsintsabis specifically, and why/how these social complexities have affected this process. We argue that the case of Tsintsabis shows the importance of acknowledging historically built-up injustices when addressing current social complexities, and we emphasise the importance of doing long-term ethno-historical and ethnographic research to be able to better understand contextual processes of resettlement (also see Chapters 4, 12, 13, 14 and 15). Such knowledge is crucial to inform policy and practice.

16.2 Methodology

Whereas the historical and theoretical components of the chapter are based on academic and grey literature and ethnographic research, the contemporary social complexities in Tsintsabis are largely based on ethnographic research including semi-structured interviews and autoethnography.

First author Koot has lived, worked, and conducted research in Tsintsabis since 1999, with multiple returns to the area. Initially conducting fieldwork there as an MSc anthropology student in 1999, he would later become a development fieldworker between 2002 and 2007, working together with inhabitants—in particular members of the Tsintsabis Trust—in founding Treesleeper Camp.17 This experience included a close collaboration with second author ǁKhumûb and a large variety of people in or connected to Tsintsabis. Since then, he returned for shorter visits to conduct and disseminate research, including for his PhD in 2010.18 Currently he functions as an adviser for the Tsintsabis Trust, including regular contact via email and WhatsApp with some inhabitants. Through these activities and visits, over the years he has engaged in longitudinal research through ‘ethnographic returning’.19 He has also conducted research among other San in Bwabwata National Park and the Nyae Nyae Conservancy, Namibia, and in the Northern Cape, South Africa.

ǁKhumûb has lived in Tsintsabis since 1991. He was born at farm Plaaszak around 15 kms west of Tsintsabis and is a native Haiǁom speaker. He moved to Tsintsabis when he was around nine years old. Since 2003 ǁKhumûb has been the camp manager of Treesleeper Camp. In 2009 he went to the !Khwa ttu Centre,20 South Africa, for a year-long work and training experience. Furthermore, he followed advanced training courses about Indigenous peoples’ rights at the University of Namibia and the University of Pretoria, and has collaborated with a variety of institutions with a focus on Indigenous peoples and the San. He also collaborated with the Windhoek-based NGO Legal Assistance Centre (LAC) in research about Indigenous peoples and climate change, focusing on Haiǁom relationships with climate change.21

Because we share a long history in Tsintsabis in different positions that changed over the years, an important method this chapter builds on is autoethnography. This very specific type of ethnography is based on self-observation and reflexivity by researchers in which cultural and personal issues are interconnected and become blurred.22 Through this approach our subjective personal experiences connect and inform the empirics and broader sociocultural analysis of the chapter.23

16.3 History of land dispossession among Haiǁom

Haiǁom speak Khoekhoegowab (also spoken by Nama and Damara/ǂNūkhoen) rather than a San language, but nonetheless are considered the largest ‘subgroup’ of San in Namibia,24 numbering between 11,000 to 15,000.25 During the 19th and early 20th centuries, they lived a semi-nomadic lifestyle based on seasonal mobility in an area ranging from present-day Grootfontein, Tsumeb, Etosha National Park (ENP), Otavi, Otjiwarongo and Outjo and the area formerly named Owamboland,26 where they also overlapped with other groupings of people. Before colonial settlement, they were in contact with a variety of both Bantu-language speakers and other Khoekhoegowab-language speakers such as Damara/ǂNūkhoen. They traded with these groups (especially with Owambo) and shared some cultural similarities (especially with Damara/ǂNūkhoen).27 Whilst this diversified their livelihoods and changed their hunting and gathering patterns, they never fully became cultivators or herders.28

North-central Namibia was affected by the gazetting of Game Reserve No. 2 in 1907, and the later establishment of Etosha National Park in 1967 (for detail regarding these histories see Chapters 1 and 2).29 Around 1910–1915 ‘Bushmen patrols’ in the farming area around the game reserve often resulted in death, and in 1928 San were forbidden to possess bows and arrows there; although not in the game reserve, where they were initially tolerated and used to enchant tourists as an image of ‘wild’ Africa30 (see Chapters 2, 4 and 15). In addition, some Haiǁom were employed as road workers, police assistants, veld fire fighters, waterhole cleaners, and cheap labour more generally.31 From the late 1940s onwards, however, they were ever more restricted, especially regarding their livestock and hunting,32 as detailed in Chapters 2 and 4. Plans in the 1940s for a Haiǁom Reserve were dismissed on the grounds that they were not considered “pure” San, and to provide a labour pool for white settler farmers in the area—ultimately leading to their eviction from ENP in 1954.33 From then on, most of them had to work on commercial farms, while some stayed to work in Etosha. The eviction was a gradual process and to this day there are Haiǁom living and working in the park.34 As a result of this history, many Haiǁom in Tsintsabis continue to feel strong ties to the ENP area (see Chapter 15). As one woman who was born in Namutoni, ENP, explains:

[i]n 1944 we were happy, because we were living on our own. But then we were chased away from Namutoni after a while, in 195635 that was, yes, because the South African government wanted to make it a game park. But Etosha belonged to the Haiǁom. […] Now we had to go and look for a job. […] And in Namutoni we were on the truck when they chased us away. Some of our people had then already died.36

Even after 1954 many Haiǁom were still moving in and out of ENP but, in the end, Haiǁom became a group without land of their own.37

This process additionally and rapidly reduced Haiǁom access to resources, as they were living in these newly claimed farming areas. Incoming livestock ate bushfoods, and the new settlers hunted game and erected fences, strongly affecting the Haiǁom’s hunting and gathering livelihood. Increasingly, others were now telling Haiǁom that they could not remain on “their” land and Haiǁom families started working on these new farms.38 Many felt mistreated there, because payments were only in kind (food, milk or porridge, sometimes including alcohol and/or tobacco). As missionary Reverend C.H. Hahn observed in these times:

[t]he Heikom have perhaps suffered more than any other Bushman tribe. […] Their various family clans or groups have become disintegrated and have been pushed further and further north […] latterly by our own settlement schemes. Their hunting grounds and veld kos [field food] areas have either been completely taken from them or have shrunk to such an extent that in very many cases the wild or semi-wild Heikom today finds it almost impossible to eke out an existence. […] It is surprising that these people do not indulge in more cattle and stock thieving.39

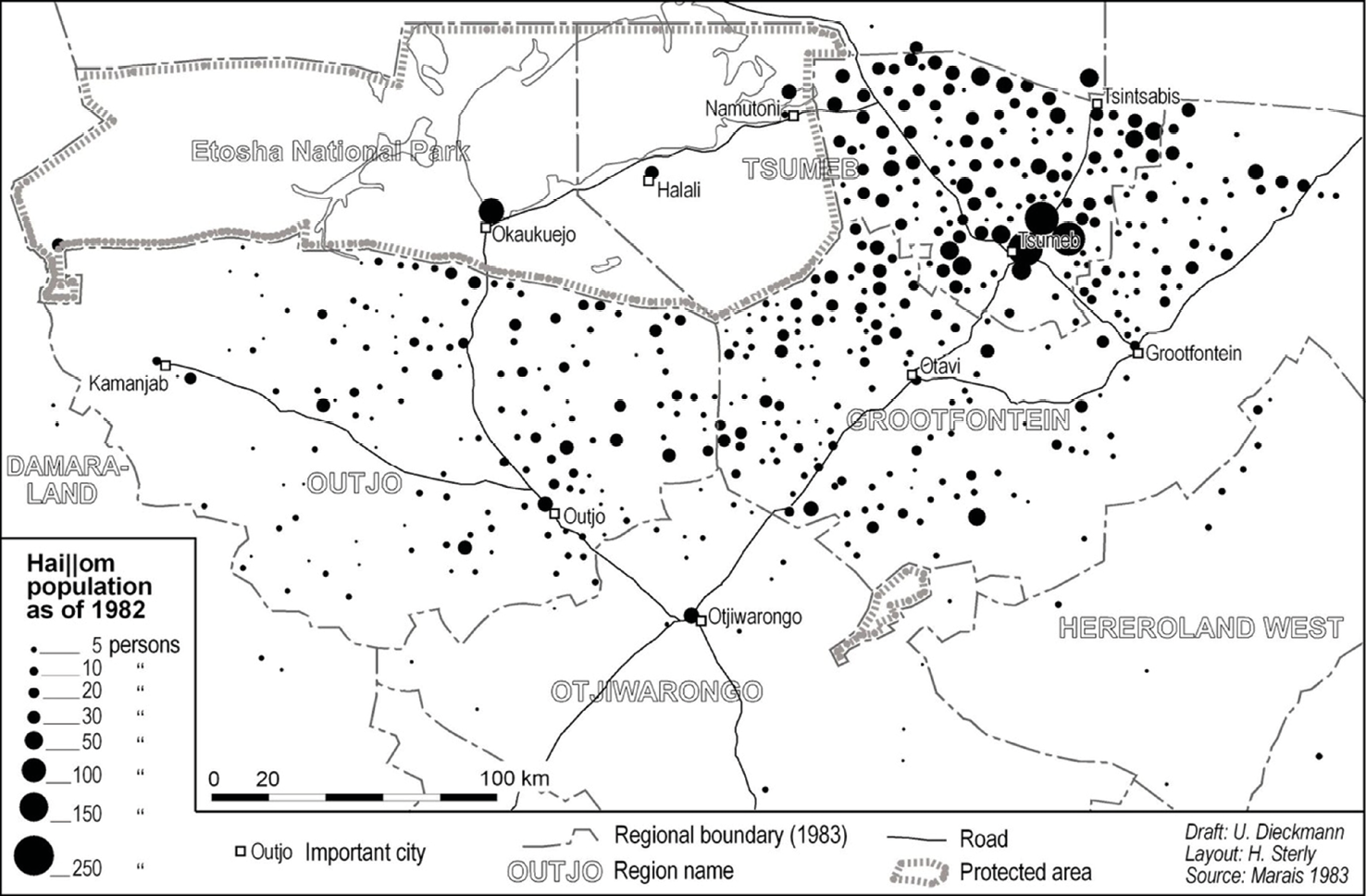

Haiǁom working at these farms also resisted mistreatment.40 At these settler farms under freehold tenure, Haiǁom would do cleaning, herding, milking cows and goats, fencing or transporting materials on ox-carts (Figure 16.1 shows the Haiǁom population in 1982).

Fig. 16.1 Map of the Haiǁom population in and around Etosha in 1982: Tsintsabis is in the top right corner. Source:

© Dieckmann (2007: 205), reproduced with permission, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Later, many farms initiated tourism just outside the gates of ENP, often with little involvement by Haiǁom.41 Since Independence, the number of people employed on farms decreased by 36%, mainly as a result of new labour and social security regulations, the uncertainty that land reform posed to land owners, a minimum-wage, and changing farm practices (e.g. the increase in safaris and guest farms). This situation resulted in the fast growth of resettlement camps and urban townships, with more people seeking casual labour. This development hit (ex-)farm workers such as the Haiǁom hardest, because they lacked access to communal areas and most had no residence outside their workplace. Consequently, they moved to settlements (e.g. Oshivelo), where they lived from informal labour, prostitution, welfare and begging.42 Some also moved to newly established resettlement farms in the area, including Tsintsabis.

Ironically, when the government purchased farms in traditional Haiǁom territory after Independence, these were mostly allocated to others, i.e. non-Haiǁom with better connections and education.43 Regardless of national policy priorities in post-Independence resettlement, the new government initially purchased 22 farms in areas where many landless San dwelled, but only one (Skoonheid) was set aside for their resettlement. At first, no farms were made available to landless Haiǁom apart from the then-MLRR (Ministry of Lands, Resettlement and Rehabilitation)44 taking over the administration of Tsintsabis.45 Despite the government making promises to acquire farms to the east of Etosha for Haiǁom as resettlement farms, this did not materialise for a long time, to the frustration of many. Furthermore, in some areas such as Mangetti West (50 kilometres north-west of Tsintsabis), there is on-going pressure on land: Haiǁom living there are concerned they will be displaced again because they lack serious political influence. From 2007 onwards, however, more farms were acquired for Haiǁom under the San Development Programme (SDP),46 including nine farms (seven used for resettlement and two for tourism purposes) in an area south and east of Etosha. This process cannot be seen apart from the government’s wish to resettle Haiǁom still living in the park to areas outside of it, in connection with a collective action lawsuit by a group of Haiǁom seeking to reclaim parts of ENP:47 as detailed in Chapter 4.

Ten years ago, Dieckmann and Dirkx48 identified only a few positive signs for San at group resettlement farms, and four big challenges. First, a relatively dense population, overstocking of livestock, and issues regarding common property resource management. Second, resettled San have not received individual title deeds.49 Third, despite initiatives to make beneficiaries self-sufficient there is still a high level of dependency. Fourth, the MLR engaged with a large number of NGOs (for instance Namibia Nature Foundation (NNF), Komeho Namibia and the Desert Research Foundation Namibia (DRFN), co-financed with large international donors) with the aim to improve the sustainable use of farm resources and strengthen resettlement beneficiaries’ livelihoods: this large number of stakeholders, however, led to problems of coordination.50 Thus far, San beneficiaries on these group resettlement farms are far from self-sufficient. At the root of the latter concerns are also illiteracy, a low level of education and technical expertise, and difficulties in terms of capacities to further strengthen leadership among the San.51

16.4 Tsintsabis histories

Tsintsabis is situated almost 120 km east of Etosha, and 60 km north of Tsumeb. Already in 1903 the place was mentioned by German colonist Paul Rohrbach, as a waterhole without permanent human habitation, although he mentions San people living in the area.52 Later, Tsintsabis turned into a commercial farm, and became a regional police station shortly after 1915 when more farmers started settling in the area. When South Africa acquired a League of Nations mandate to run the then South West Africa in 1919, another 15 policemen arrived in Tsintsabis. As several respondents explained about these days, the policemen built the first houses and employed some Haiǁom in this process. Haiǁom also worked as cooks, translators, cleaners or camel herders. Steadily the South African police placed more restrictions on the San.53 As one inhabitant later explained, ‘if the police would see us hunting you could be taken into jail’.54 In 1936 the station commander at Tsintsabis rural police station reported that ‘[f]armers find the Bushmen the cheapest kind to engage as it is a known fact that most of these Bushmen are only working for their food and tobacco, and now and then they get a blanket or a shovel’.55 In and around Tsintsabis, many San thus became farm workers. Furthermore, the South African police in Tsintsabis also needed San trackers to prevent San attacks on contract workers from the North who passed through the area. As explained in a telegram by the Native Affairs Tsumeb on 24 September 1934, such attacks made them ‘consider Tsintsabis police be temporarily increased by five to six Bushman trackers’.56 In the years that followed, supervision of the South African police became stricter, including serious physical and psychological abuses.57

From about 1982 until 1990 the Namibian war for Independence was strongly felt in Tsintsabis: the police station was turned into an army base for the South African Defence Force (SADF) for which many Haiǁom became trackers. These days were increasingly characterised by fear and insecurity: the main access road into Tsintsabis from Tsumeb was called the ‘Road of Death’,58 and the SADF ruled strictly but also provided work and food, similarly to the farmers’ paternalistic relations with the San.59 However, the war also created more insecurity. One interviewee stated:

[t]he South Africans did not beat the children, but they beat the men and women. Always when they were coming, sometimes the people they were running away, because they were afraid. We did not fight back to them because the people were afraid and the white men had the guns. Also sometimes we were running away and sleeping in the bush because the people were telling us the SWAPO’s [South West African People's Organization] are coming.60

So, on the one hand the South Africans seemed to treat San better because they were dependent on them for their tracking skills and labour. On the other hand, punishment was continuing as before. A 39-year old man explained that ‘they forced some people to join them. I was also forced. If I did not go I had to go five years in prison’.61 Under this paternalistic system, however, San generally were mostly regarded and treated as inferior: their traditional egalitarian approach and social systems were strongly disrupted.62

Haiǁom have thus historically had, and continue to have,

long-standing contacts with other groups and have adopted many cultural elements from their neighbours. As a consequence they have also suffered academic and political neglect, owing to their allegedly “mixed” or “impoverished” culture.63

This situation has led to diversity in the social practices of Haiǁom as:

part of a process in which a certain mode of social relatedness has developed and is cultivated in many different fields of everyday social practise as “Bushmen” interact with neighbouring groups in a changing natural and historical environment.64

Their history of inferiority in relation to others has undoubtedly affected Haiǁom relations with other groups and leadership structures, also after Independence.

In 1993, Tsintsabis was transferred into a group resettlement farm of 3,000 ha.65 This means that in Tsintsabis many Haiǁom and some !Xun were, strictly speaking, not “resettled” but continued to stay where they already lived under a different administration, and had to find new post-SADF livelihoods. In 1993, the government counted 841 people living at the farm, a number that increased to more than 1,500 in 2010 because ‘the influx of people has not been controlled’.66 In 2012 this number had grown to between 3,000 and 4,000,67 mostly due to in-migration. There were two main groups of in-migrants: the first group is predominantly of Haiǁom farm workers who came to live with their relatives in Tsintsabis after losing jobs at surrounding commercial farms sold under the national land reform programme. Second, the relatively new tar road that runs through Tsintsabis attracted people, especially non-San, who could easily settle due to the uncontrolled situation of land allocation (see below). Today, some households live in government-supported brick houses while others live in huts or shanties. Tsintsabis also accommodates the Tsintsabis Combined School (up to Grade 10), a medical clinic, a craft centre, a community tourism camp, and a police station.

The initial plan for Tsintsabis was that “resettled” Haiǁom and !Xun would use the land collectively. Later the government provided individual 10 ha plots to beneficiaries, with the intention for them to become self-sufficient small-scale farmers. Until today, however, the provision of food through agriculture is very limited. Some of the plots in Tsintsabis are too sandy for subsistence agriculture, and they ‘are not fenced off and do not provide any infrastructure for sustainable gardening or animal husbandry projects’.68 Most people depend to a large extent on food aid, provided by the MLRR since 1993 and changed in 1998 to only emergency drought food relief. These food distributions were later complemented by the San Feeding Programme of the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), provided by the then Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Rural Development (MAWRD). Food aid was combined with other livelihood sources including monthly pensions, farm work at commercial farms, some (illegal) hunting (and meat selling), gathering, tourism, livestock herding (cattle and goats especially), traditional healing, and small businesses such as shebeens (where groceries, alcohol and soft drinks are sold). The government’s focus on agriculture was criticised by the informal Haiǁom leader Willem |Aib when he visited Tsintsabis in 1999. He explained that Haiǁom were

traditionally unknown to gardening. All they ever had to do with farming was looking after the cattle and the goats. […] And now the government expects them to go farming but they never did it.69

In addition to limited acquaintance with agriculture,70 water provision, tools and equipment to work the land are difficult to acquire. Furthermore, most people only grow maize or mahangu (pearl millet), which lacks the variety needed for a healthy diet. The agricultural carrying capacity of Tsintsabis appears to have passed its potential long ago, whilst government assistance in agriculture was insufficient and community members lacked business skills.71 Additionally, young people are often bored and experience a lack of opportunities. Harring and Odendaal72 of the LAC in Windhoek concluded already in 2006 that ‘Tsintsabis represents a failed model of rural settlement that is all too common in Namibia’.

16.5 Contemporary social complexities

Against this historical background of Haiǁom land dispossession and the development of Tsintsabis into a resettlement farm, we now look deeper into, and try to better understand, two important contemporary social complexities. In Tsintsabis the two social complexities that stand out are ethnic tensions as a result of in-migration, and issues regarding leadership. We turn to ethnic tensions first.

16.5.1 Ethnic tension and in-migration

The above-mentioned shortcomings of the resettlement programme including the lack of land tenure security73 combined with an enormous influx of people in Tsintsabis, have led to a dire situation for the beneficiaries. Today, there continues to be dissatisfaction among the Haiǁom and !Xun of Tsintsabis about many things, one of the main ones being the social complexities related to in-migration of other ethnic groups (i.e. non-San) and resulting exclusion and discrimination of San residents. Since Independence there has been much in-migration, which often instigates fear of suppression, land loss and exclusion (e.g. from jobs) among the San.74 This is a broader phenomenon in more areas in Namibia where San (and others) live,75 but pressure in Tsintsabis seems relatively high due to the continuous influx of people since Independence onto a limited amount of land. As a result of in-migration, ethnic tensions have intensified.

Notable in this regard is the drastic rise in the number of shebeens (where the sale of alcoholic beverages is a core business), most of them owned by non-San.76 Shebeens have been in Tsinstabis since the start of the resettlement programme, but with the increasing number of non-San in-migrants their number has skyrocketed. Shebeens have led to some San doing small jobs in service of the shebeen owners (e.g. fetching water) in return for alcohol, resembling pre-colonial patron-client relations between San and Bantu peoples.77 As one interviewee stated in 2016:

[o]nce the other tribes moved in, they came here and then they put up their shebeens, lot of shebeens drinking places. Now these eh lot of San people Haiǁom people which are already poor have now been addicted to drinking. So those who are now drinking alcohol early in the morning, stand up, go to the drinking place and then now they are fetching water for those people every day.78

Moreover, the alcohol abuse associated with shebeens increases physical and domestic violence and even deaths, while children also start to drink.79 Due to the informal character of shebeens, and their tendency to appear and disappear again, it is impossible to give an exact number. Important in this regard, however, is that there have been protests against them in 2014 after two Haiǁom brothers were stabbed to death, while the MLR administrator’s personal shebeen is still open in 2023—despite an earlier public request in 2010 by the deputy prime minister to close down all shebeens for the problems they cause.80

Additionally, just as among other San groups in Namibia, in-migration has led to exclusion and discrimination.81 In particular, government jobs in Tsintsabis were mostly given to non-San, due to job requirements and the San not being able to fulfil these requirements based on their backlog in formal education. But it also goes beyond formalities. Over the years, many San have complained about ethnic favouritism and San discrimination when jobs were available, for instance at the police force. As the only Haiǁom policeman explained in 1999:

[w]e have only one Haiǁom [police officer] in Tsintsabis […] I don’t say I don’t want these people [non-Haiǁom], but if they don’t know the language and the area […] if they go to the people, the people are maybe afraid of them, they cannot talk of anything. […] They don’t take us because we don’t have the education and the school. That is why they think they mean nothing, they know nothing, but they have got the skills. You can educate people, but it does not mean that they know.82

In 2023 there is still only one Haiǁom police officer (a different one now), despite the police force’s growth over the years.

Such exclusion from the limited pool of jobs was also felt in 2009 during road construction work on the D3600, when many external labourers stayed in Tsintsabis.83 Despite most of them being Namibian (around 90% of 350 workers), only a few came from the surrounding areas. This again instigated fear among Haiǁom that Tsintsabis would be further taken over by others. Because the farm is already too small to provide all households with a reasonable plot, in-migration further increases land pressure. Moreover, people complained that some of the road workers seduce young girls (as young as 13 or 14) with alcohol and treat them as prostitutes.84 Haiǁom complained about racism and paternalism by road construction managers, and there have been accusations that the few employed Haiǁom were paid below the minimum wage. To speak out, however, would mean they risk losing their jobs.85

An important general conception among San in Namibia is that San groups are looked down upon and treated as inferior,86 as explained by a young woman when talking about her childhood experiences in school:

[w]e are not the higher classes because the other people are working in the special place, like that, maybe in the big city. They think that’s why they are better […] When they saw us, and our jewels, then they were making the jokes of us. And also because we have the small feet, and we have the small fingers. That is still happening, also after independence […] with all Bushmens, also !Xung, and also Haiǁom. But me I always say that I’m proud to be Haiǁom!87

A feeling of powerlessness, distrust and inferiority in relation to in-migrants continues until today.88 However, there are also some sentiments about reverse discrimination, albeit much less. One shop owner explained:

[n]ewcomers who are of any other tribe than Bushmen do not have any power in this place. They have to listen to the Bushmen. Here in Tsintsabis it often happens that I am insulted. People then say, “It’s not your place, it’s ours” or “We are poor and you take all our money”.89

Hüncke90 writes that the biggest fear of San in Tsintsabis was ‘losing access to land to economically strong outsiders’. As a young Haiǁom woman stated:

[r]ich people from outside will take over our places. The newcomers will go to the headman and ask for a plot without informing those to whom the plot used to belong. [...] there will be quarrels between the first people, the Haiǁom, and the new people, for example Kavango, Herero.91

Over the years Haiǁom and !Xun have also complained about in-migrants erecting fences to demarcate their plots, restraining them from collecting firewood or gathering veldkos (field foods) on these lands. As a result, they fear their children will not be able to continue living there.92 An elderly woman explained:

[t]oday all the lands from there has been sold. To the police officers, to the nurses, people who work in the government, officials, they are the ones who bought the lands from there.93

Despite several visits from government officials over the years promising to improve the situation for the Haiǁom and !Xun in Tsintsabis, most of them have now lost faith in the government.94 Similarly, many have lost faith in their official and unofficial leaders. This is the dimension of social complexity we turn to next.

16.5.2 Leadership

As explained above, throughout history, San groups have often been positioned in society as inferior to others. In relation to other ethnic groups before colonialism, they engaged in relationships with pastoralists as servants or slaves in patron-client relationships.95 Later, this inferior position continued under colonialism and apartheid, when working as labourers on freehold farms or in other positions (e.g. working for the SADF). Many Haiǁom and !Xun in Tsintsabis (as well as other San groups) express themselves today as if they still feel inferior in their relations with others (i.e. other ethnic groups, white farmers, expatriates or government officials).96 Nonetheless, some San groups have been allowed to establish government-recognised Traditional Authorities (TAs) after Independence (see Chapter 4, Section 4.4). Each TA consists of a “Chief” and a traditional council serviced by traditional district “headmen” and “headwomen”.97 Traditionally, however, San groups favoured leadership structures that were relatively egalitarian, focused on consensus, and that pushed against a strong hierarchy.98 The new TA system requires a more formal and hierarchical institutionalisation of their leadership that does not take into account their traditional social structure.99

Among Haiǁom the establishment of a TA that represents all Haiǁom has led to much tension: they appointed a Chief in 1996 (Willem |Aib) who was not recognised by the government,100 but in 2004 the government designated a Haiǁom TA under the Traditional Authorities Act.101 David ǁKhamuxab, a staunch SWAPO supporter making no claims to ENP, became the Chief, but it remains unclear how this appointment was organised and how much it was supported by the larger group of Haiǁom (see Chapter 4):

[i]n 2004, the government of Namibia appointed a Haiǁom TA, David ǁKhamuxab. There were differences of opinion among the Haiǁom about how Mr. ǁKhamuxab was selected. Some people said that the government of Namibia appointed the TA without reference to local opinions. A number of Haiǁom raised questions about the electoral process that led to the appointment of the TA. […] There were Haiǁom in some areas of Namibia who said that they had held elections but that none of the individuals who they voted for was considered by the government for the Haiǁom TA.102

Support among the broader Haiǁom community appears to have been limited, including in Tsintsabis, where ǁKhamuxab’s appointment was received with suspicion and where people had not joined any voting process.103 Today, Haiǁom in Tsintsabis expect from leaders under the new TA system that they would prevent in-migration (as described in Section 16.5.1) or instigate and support development processes for the group at large. Most have no confidence in Chief ǁKhamuxab or his headman in Tsintsabis, and they prefer a Chief in their own area and not from Outjo (almost 300 km away) where ǁKhamuxab is based.104 Since 2004, there have been two headmen (regional councillors) appointed by and serving/representing ǁKhamuxab in Tsintsabis.

For a long time now, there have been tensions between the first headman representing Chief ǁKhamuxab in Tsintsabis and the “development committee” appointed by the MLRR already in the early 1990s when Tsintsabis became a resettlement farm. This committee initially consisted of 20 to 25 (mostly older) Haiǁom and !Xun inhabitants.105 It is supposed to oversee

the implementation of the [resettlement] programme and sub committees are supposed to work in the different income generating projects. Some of these sub committees are still operating while others no longer exist as their project members have moved out of the village for paid jobs in Tsumeb or nearby farms.106

During the road construction work in 2009 (see Section 16.5.1), suspicion towards ǁKhamuxab's first headman—who was also employed by the Road Construction Company (RCC) as a mediator to divide jobs—also increased, with people organising a demonstration against his alleged nepotism: apparently his family members received the better and permanent jobs (seven out of 15 permanent jobs) and people felt there was no fair distribution of jobs overall.107 He was blamed for not supporting but exploiting his own people, for instance by not assisting them to get the right working equipment or holding back part of their salaries. In the end, the new road hardly increased the number of jobs for Haiǁom and !Xun in Tsintsabis, but ‘the traffic on the road, mainly large trucks, has brought drug trade, prostitution and other criminal activity to Tsintsabis, something which mainly affects the youth and creates a feeling of insecurity’.108 Furthermore, he also faced criticism for assumed support in allocating land to outsiders. Due to these reasons, most San in Tsintsabis lost faith in this first headman.109

Due to all the pressure, the first headman stepped down in 2012 and another one replaced him to become the second headman of Chief ǁKhamuxab in Tsintsabis. Despite this change, many still regard the first headman as an informally important person and both he and the second headman continue to be accused in 2023 of giving away land to receive personal benefits, including from government officials. If these accusations are correct, local authorities representing Haiǁom evidently play an important role in ongoing processes of land dispossession. Without specifying any persons in particular, the government warned inhabitants of Tsintsabis in September 2023 in a public notice that:

certain persons, including some members of the Tsintsabis community, are involved in illegal land dealings on the said farms [Chudib-Nuut, Urwald and Tsintsabis]. As a result, a number of individuals have grabbed or have been allocated land illegally on these farms.110

A new tactic is applied by some officials and powerful outsiders who gained land illegally for themselves with the support of the first headman representing ǁKhamuxab, as observed by co-author ǁKhumûb over the years: in the area from Grootfontein to Mangetti West to Oshivelo (which is at the heart of “traditional” Haiǁom land), they meet with Haiǁom who are then being told to disclose themselves as non-Haiǁom in return for small benefits (e.g. cash or food). The first headman, still functioning as an important informal leader in Tsintsabis these days, is currently trying to set up a TA body separate from the Haiǁom TA to be able to allocate land in these areas or to legitimate previous illegal allocations to officials and powerful outsiders. For this potential new non-Haiǁom TA these allocations will be easier if people indeed identify as non-Haiǁom, because that would mean they do not fall under the Haiǁom TA.

At a national level, the current tendency in the government is to regard Haiǁom not as San, as was also done in the past under the South African administration (see Chapters 2 and 4). New plans by different groups of Haiǁom aim to appoint different TAs for various geographical areas that would then split up the group that is currently regarded as “the” Haiǁom. This would support initiatives as described above, in which Haiǁom are pressured not to disclose themselves as Haiǁom. In response, Haiǁom (including some headmen/headwomen and informal leaders) from Ondera, Grootfontein, Oshivelo and other places that carry strong historical value for them discussed the challenges and how their rights are violated. As ǁKhumûb has observed, they are in the process of formulating a plan based on these challenges to inform civil society organisations and law firms and explain the violations of their human rights. The LAC and the Namibian San Council (NSC) are supportive, but currently lack the means to enact this plan. Together these leaders wrote a letter to the President in 2020, but never received a response.

16.6 Conclusion

Although the social complexities addressed in this chapter are not completely new and can be considered important issues for Namibian San at large, this does not mean they should not be subject to further investigation. It is precisely because of their structural character and their tendency to remain unresolved that they continually need to be addressed. Both in-migration and related ethnic tensions, as well as issues surrounding leadership, are related social complexities that continue to explain why resettlement among the San of Namibia has repeatedly run into problems since Independence. Questions remain concerning why these structural social complexities have not been addressed more seriously in policies and practice, and how to handle this in the future. Exploring historical circumstances and focusing more on ethnographic research is an important step in the analysis of social complexities:111 it assists with clarifying the social dynamics that strongly affect resettlement on the ground. As a crucial pillar in the larger national land reform programme, social complexities such as in-migration, ethnic tensions and leadership are pivotal for understanding why resettlement works or not. We argue that the case of Tsintsabis shows the importance of acknowledging historically built-up injustices when addressing current social complexities; and we emphasise the importance of doing long-term ethno-historical research about resettlement to be able to better understand contextual processes around resettlement. Such knowledge is crucial to inform policy and practice.

Sustained research over the last few decades has shown how Tsintsabis and its surroundings land has kept being grabbed by more powerful groups, and that development through the group resettlement programme has been highly problematic.112 Agricultural support from the government has been limited while the few income-generating activities at the farm (a bakery, a tourism project, construction jobs, etc.) revealed ethnic tensions and discrimination (especially of San) and problems surrounding leadership. Such shortcomings were addressed at the Second National Land Conference in Windhoek in 2018,113 but land-grabbing dynamics remain and are reinforced in recent developments. As we have seen, land in and around Tsintsabis is abducted by more powerful groups. “High officials” hold private meetings to request Haiǁom to deny their ethnic status as Haiǁom, and to make small-scale land grabbing easier. These findings are important for the future of resettlement and warrant further ethnographic investigation. Indeed, generally speaking, resettlement projects in southern Africa have often ‘failed to restore the livelihoods of people affected’.114 This is also applicable in Tsintsabis, where many Haiǁom and !Xun feel ‘deprived of their rights because they cannot own the resettlement land but only the buildings on the land’.115 In fact,

[in] many ways, people explain that they still feel colonised, or like slaves. [This] fits into the long history of many San groups in Namibia and southern Africa of being some of the most marginalised people in the region.116

An important recent development regarding the future of Tsintsabis is that in 2020 it was formally announced that Tsintsabis would become a formal “settlement”,117 with around two-thirds remaining a resettlement farm and a third becoming a settlement falling under the Guinas Constituency. This change means that Tsintsabis will cease to fully be a resettlement farm, and different rules and regulations will apply for a central part where most services and provisions are located. The regional officer of the constituency ‘assured the public that the area is receiving undivided developmental attention’.118 It is doubtful, however, how much development this will truly bring, since the Guinas Constituency is without an office in Tsintsabis: the regional officer also explained that the council’s hands were tied by a government moratorium on the construction of offices.119 An additional potential consequence is that most Haiǁom and !Xun will be excluded from benefiting from new services at the settlement, because they will need to pay for these services and many of them lack the means to do so. At this stage, it is unclear what this development means for in-migration, leadership and people’s rights to land.

Bibliography

Ahmed, I. 1985. Concepts and issues in land reforms. In Ahmed, I. (ed.) Rural Development: Options for Namibia after Independence: Selected papers and proceedings of a workshop organised by the ILO, SWAPO and UNIN, Lusaka, Zambia, 5-15 October 1985. Geneva: International Labour Organisation, 121–22.

Asino, T. 2014. Pensioner shoots men over tombo. New Era 3.3.2014, https://neweralive.na/posts/pensioner-shoots-men-tombo

Barnard, A. 2019. Bushmen: Kalahari Hunter-Gatherers and their Descendants. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Berndalen, J. 2010. The Road to Hell. Insight Namibia 10: 38.

Biesele, M. and Hitchcock, R.K. 2011. The Ju/’hoan San Of Nyae Nyae And Namibian Independence: Development, Democracy, and Indigenous Voices in Southern Africa. New York: Berghahn Books.

Castelijns, E. 2019. Invisible People: Self-perceptions of Indigeneity and Marginalisation From the Haiǁom San of Tsintsabis. Unpublished MSc Thesis, Wageningen University, https://edepot.wur.nl/468298

Dieckmann, U. 2001. ‘The Vast White Place’: A history of the Etosha National Park and the Haiǁom. Nomadic Peoples 5: 125–53, https://www.jstor.org/stable/43124106

Dieckmann, U. 2003. The impact of nature conservation on the San: A case study of Etosha National Park. In Hohmann, T. (ed.) San and the State: Contesting Land, Development, Identity and Representation. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, 37–86.

Dieckmann, U. 2007. Haiǁom in the Etosha Region: A History of Colonial Settlement, Ethnicity and Nature Conservation. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Dieckmann, U. 2011. The Haiǁom and Etosha: A case study of resettlement in Namibia. In Helliker, K. and Murisa, T. (eds.) Land Struggles and Civil Society in Southern Africa. New Jersey: Africa World Press, 155–89.

Dieckmann U. 2014. Kunene, Oshana and Oshikoto Regions. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 173–232.

Dieckmann, U. 2023. Thinking with relations in nature conservation? A case study of the Etosha National Park and Haiǁom. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 29(4): 859–79, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.14008

Dieckmann, U. and Begbie-Clench, B. 2014. Consultation, participation and representation. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 595–616.

Dieckmann, U. and Dirkx, E. 2014. Access to land. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 437–64.

Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) 2014. Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia.

Dieckmann, U. Thiem, M. and Hays, J. 2014. A brief profile of San in Namibia and the San development initiatives. In Dieckmann, U., Thiem, M., Dirkx, E. and Hays, J. (eds.) Scraping the Pot: San in Namibia Two Decades After Independence. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project of the Legal Assistance Centre and Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, 21–36.

Ellis, C.S. and Bochner, A. 2000. Autoethnography, personal narrative, reflexivity: Researcher as subject. In Denzin, N. and Lincoln, Y. (eds.) Handbook of Qualitative Research. London: Sage, 733–68.

Fabinyi, M., Knudsen, M. and Shio, S. 2010. Social complexity, ethnography and coastal resource management in the Philippines. Coastal Management 38(6): 617–32, https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2010.523412

Gargallo, E. 2010. Serving production, welfare or neither? An analysis of the group resettlement projects in the Namibian land reform. Journal of Namibian Studies 7: 29–54, https://namibian-studies.com/index.php/JNS/article/view/37

Gordon, R. 1992. The Bushman Myth: The Making of a Namibian Underclass. Oxford: Westview Press.

Gordon, R.J. 1997. Picturing Bushmen. The Denver African Expedition of 1925. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press and Namibia Scientific Society.

Gordon, R. and Sholto Douglas, S. 2000. The Bushman Myth: The Making of a Namibian Underclass. London: Routledge.

GRN 2000. Traditional Authorities Act. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia.

GRN 2010. Report On the Review of Post-resettlement Support to Group Resettlement Projects/farms 1991–2009. Windhoek: Government of the Republic of Namibia.

GRN 2018. Resolutions of the Second National Land Conference, 1st–5th October 2018. Windhoek: MAWLR.

Harring, S.L. and Odendaal, W. 2002. ‘One Day We Will All Be equal…’: A Socio-legal Perspective On the Namibian Land Reform and Resettlement Process. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre.

Harring, S.L. and Odendaal, W. 2006. Our Land They Took: San Land Rights Under Threat in Namibia. Windhoek: Land Environment and Development Project Legal Assistance Centre.

Harring, S.L. and Odendaal, W. 2007. “No Resettlement Available”: An Assessment of the Expropriation Principle and its Impact on Land Reform in Namibia. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre.

Hays, J. 2009. The invasion of Nyae Nyae: A case study in on-going aggression against hunter-gatherers in Namibia. In Forum for Development Cooperation with Indigenous Peoples (ed.) Forum Conference 2009: Violent Conflicts, Ceasefires, and Peace Accords through the Lens of Indigenous Peoples. Tromsø, Norway: Forum for Development Cooperation with Indigenous Peoples, 25–32.

Hitchcock, R. 2012. Refugees, resettlement, and land and resource conflicts: The politics of identity among !Xun and Khwe San in Northeastern Namibia. African Studies Monographs 33 (2): 73–132, https://repository.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2433/159000/1/ASM_33_73.pdf

Hitchcock, R. 2015. Authenticity, identity, and humanity: The Haiǁom San and the state of Namibia. Anthropological Forum 25(3): 262–84, https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2015.1027658

Hitchcock, R.K. and Vinding, D. 2004. Indigenous peoples’ rights in Southern Africa: An introduction. In Hitchcock, R.K. and Vinding, D. (eds.) Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in Southern Africa. Copenhagen: IWGIA, 8–21.

Hüncke, A. 2010. Treesleeper Camp: Impacts on Community Perception and on Image Creation of Bushmen. Unpublished MRes. Thesis, African Studies Centre, Leiden.

Karuuombe, B. 1997. Land reform in Namibia. Land Update 59: 6–7.

Koot, S. 2012. Treesleeper Camp: A case study of a community tourism project in Tsintsabis, Namibia. In Van Beek, W.E.A. and Schmidt, A. (eds.) African Hosts & Their Guests: Cultural Dynamics of Tourism. Woodbridge, Suffolk: James Currey, 153–75.

Koot, S. 2013. Dwelling in Tourism: Power and Myth Amongst Bushmen in Southern Africa. Unpublished, PhD Thesis, African Studies Centre, Leiden, https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/handle/1887/22068

Koot, S. 2016. Perpetuating power through autoethnography: My unawareness of research and memories of paternalism among the indigenous Haiǁom in Namibia. Critical Arts: South-North Cultural and Media Studies 30(6): 840–54, https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2016.1263217

Koot, S. 2023. Articulations of inferiority: From pre-colonial to post-colonial paternalism in tourism and development among the indigenous Bushmen of southern Africa. History and Anthropology 34(2): 303–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2020.1830387

Koot, S. and Büscher, B. 2019. Giving land (back)? The meaning of land in the indigenous politics of the south Kalahari Bushmen land claim, South Africa. Journal of Southern African Studies 45 (2): 357–74, https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2019.1605119

Koot, S, Grant, J., ǁKhumûb, M. et al. 2023. Research codes and contracts do not guarantee equitable research with Indigenous communities. Nature: Ecology and Evolution 7: 1543–46, https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-023-02101-0

Koot, S. and Hitchcock, R.K. 2019. In the way: Perpetuating land dispossession of the Indigenous Haiǁom and the collective action lawsuit for Etosha National Park and Mangetti West, Namibia. Nomadic Peoples 33: 55–77, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26744808

Koot, S. and van Beek, W. 2017. Ju|’hoansi lodging in a Namibian Conservancy: CBNRM, tourism and increasing domination. Conservation and Society 15(2): 136–46, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26393281

LAC 2013. Indigenous Peoples and Climate Change in Africa: Report on Case Studies of Namibia’s Topnaar and Haiǁom Communities. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre.

Melber, H. 2019. Colonialism, land, ethnicity, and class: Namibia after the Second National Land Conference. Africa Spectrum 54: 73–86, https://doi.org/10.1177/0002039719848506

Morton, B. 1994. Servitude, slave trading and slavery in the Kalahari. In Eldredge, E. and Morton, F. (eds.) Slavery in South Africa: Captive Labour on the Dutch Frontier. New York: Routledge, 215–50.

Nawatiseb, E. 2013. Youth oust Tsintsabis headman. New Era 25.11.2013, https://neweralive.na/posts/youths-oust-tsintsabis-headman

Odendaal, W. and Werner, W. (eds.) 2020. ‘Neither Here Nor There’: Indigeneity, Marginalisation and Land Rights in Post-independence Namibia. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre.

O’Reilly, K. 2012. Ethnographic returning, qualitative longitudinal research and the reflexive analysis of social practice. The Sociological Review 60(3): 518–36, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02097.x

Ramutsindela, M. 2004. Parks and People in Postcolonial Societies: Experiences in Southern Africa. New York: Kluwer Academic Publisher.

Rohrbach, P. 1909. Aus Südwest-Afrikas Schweren Tagen: Blätter von Arbeit und Abschied. Berlin: Wilhelm Weicher.

Simasiku, O. 2020. Tsintsabis proclaimed a settlement. New Era 5.8.2020, https://allafrica.com/stories/202008050201.html

Sullivan, S. 1998. People, Plants and Practice in Drylands: Sociopolitical and Ecological Dynamics of Resource Use by Damara Farmers in Arid North-west Namibia, including Annexe of Damara Ethnobotany. Ph.D. Anthropology, University College London, http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1317514/

Sullivan, S. 1999. Folk and formal, local and national: Damara knowledge and community conservation in southern Kunene, Namibia. Cimbebasia 15: 1–28.

Sullivan, S. 2003. Protest, conflict and litigation: Dissent or libel in resistance to a conservancy in north-west Namibia. In Berglund, E. and Anderson, D. (eds.) Ethnographies of Conservation: Environmentalism and the Distribution of Privilege. Oxford: Berghahn Press, 69–86, https://doi.org/10.1515/9780857456748-008

Sullivan, S. 2005. Detail and dogma, data and discourse: Food-gathering by Damara herders and conservation in arid north-west Namibia. In Homewood, K. (ed.) Rural Resources and Local Livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa. Oxford: James Currey and University of Wisconsin Press, 63–99, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-06615-2_4

Sullivan, S. 2017. What’s ontology got to do with it? On nature and knowledge in a political ecology of ‘the green economy’. Journal of Political Ecology 24: 217–42, https://doi.org/10.2458/v24i1.20802

Suzman, J. 2001. An Assessment of the Status of the San in Namibia. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre, http://www.lac.org.na/projects/lead/Pdf/sannami.pdf

Suzman, J. 2004. Etosha dreams: An historical account of the Haiǁom predicament. Journal of Modern African Studies 42: 221–38, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X04000102

Taylor, J.J. 2012. Naming the Land: San Identity and Community Conservation in Namibia’s West Caprivi. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Terblanché, N. 2023. MAWLR warns against illegal land deals. Windhoek Observer, https://www.observer24.com.na/mawlr-warns-against-illegal-land-deals

Van der Wulp, C. and Koot, S. 2019. Immaterial Indigenous modernities in the struggle against illegal fencing in the Nǂa Jaqna Conservancy, Namibia: Genealogical ancestry and ‘San-ness’ in a ‘traditional community’. Journal of Southern African Studies 45(2): 375–92, https://doi.org/10.1080/03057070.2019.1605693

Van Rooyen, P. 1995. Agter ‘n eland aan: Een jaar in Namibië. Kaapstad: Queillerie-Uitgewers.

Widlok, T. 1999. Living on Mangetti: ‘Bushman’ Autonomy and Namibian Independence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

1 Ahmed (1985)

2 Hitchcock (2012: 75)

3 Harring & Odendaal (2007), Dieckmann (2011)

4 Karuuombe (1997: 6)

5 “San” or “Bushmen” both refer to Indigenous hunter-gatherers of southern Africa. The term “Bushmen” is based on colonial racism and has a derogatory and patronising character. The more politically correct term “San”, however, also has derogatory and patronising elements (Gordon & Sholto Douglas 2000). Despite these meanings, both terms also ‘signify important identity markers of belonging to the larger regional group that shares cultural similarities and experiences of marginalization’ (Koot, Grant, ǁKhumûb et al. 2023). When applicable we use their own ethnonyms in this chapter, namely Haiǁom and !Xun.

6 Harring & Odendaal (2007), GRN (2010)

7 Dieckmann (2011)

8 Harring & Odendaal (2002, 2007), Melber (2019)

9 Dieckmann, Thiem, Dirkx, et al. (2014), Melber (2019)

10 GRN (2010), Dieckmann & Dirkx (2014)

11 Gargallo (2010), Dieckmann, Thiem, Dirkx, et al. (2014), Melber (2019)

12 Suzman (2001), Harring & Odendaal (2002, 2006, 2007), Dieckmann (2011), Dieckmann, Thiem & Hays (2014), Odendaal & Werner (2020)

13 Harring & Odendaal (2006, 2007), Dieckmann & Dirkx (2014), Odendaal & Werner (2020)

14 Fabinyi et al. (2010: 619)

15 For example, Sullivan (1999, 2017), Koot & Van Beek (2017), Koot & Büscher (2019), Dieckmann (2023)

16 Fabinyi et al. (2010: 617)

17 Koot (2012)

18 Koot (2013, 2016)

19 O’Reilly (2012)

21 LAC (2013)

22 Ellis & Bochner (2000), Koot (2016)

23 Ellis & Bochner (2000)

24 Gordon & Sholto Douglas (2000)

25 Hitchcock (2015); Dieckmann, Thiem & Hays (2014: 23) estimate between 7,000 and 18,000.

26 Dieckmann (2007)

27 Barnard (2019)

28 Widlok (1999). Barnard (2019) explains that it is unknown if Haiǁom were at a certain point herders like many of their Damara/ǂNūkhoe neighbours; although it should be noted that the latter also relied heavily on hunting and gathering (for example, Sullivan 1998, 1999, 2005 and Chapters 12 and 13).

29 Dieckmann (2001, 2003, 2007), Ramutsindela (2004)

30 Gordon (1997)

31 Gordon (1997), Gordon & Sholto Douglas (2000), Dieckmann (2003, 2007)

32 Suzman (2004), Dieckmann (2007)

33 Gordon & Sholto Douglas (2000), Dieckmann (2003, 2007)

34 Dieckmann (2007), Koot & Hitchcock (2019)

35 This year differs from the starting year of the evictions (1954) as mentioned above, but can of course still be correct because the eviction was a gradual process.

36 Interview, 20.6.1999.

37 Gordon (1997)

38 Dieckmann (2007)

39 Cited in Gordon & Sholto Douglas (2000: 125), drawing on archives of the South West Africa Administration, 1927–1948.

40 Dieckmann (2007)

41 Dieckmann (2003), Suzman (2004)

42 Ibid., Harring & Odendaal (2006)

43 Suzman (2004)

44 The MLRR changed names into the Ministry of Lands and Resettlement (MLR) in 2005 and subsequently into the Ministry of Land Reform (MoLR) in 2015. In 2020, the MoLR was terminated and “land reform” became part of the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform (MAWLR).

45 Suzman (2004)

47 Dieckmann & Dirkx (2014), Koot & Hitchcock (2019)

48 (2014)

49 In addition to title deeds for individually allocated plots, there are often also common tracts of land, where for instance livestock can graze. For such areas, collective title deeds could be developed to prevent such lands from being grabbed and to put less pressure on the carrying capacity of a group resettlement farm.

50 Koot & Hitchcock (2019)

51 Dieckmann & Dirkx (2014)

52 Rohrbach (1909)

53 Gordon (1997)

54 Interview, 11.4.1999.

55 LGR Magistrate Grootfontein 3/1/7, Annual Report, 1936, cited in Gordon (1992)

56 Cited in Gordon & Sholto Douglas (2000: 114)

57 Gordon & Sholto Douglas (2000)

58 van Rooyen (1995: 1)

59 Koot (2023)

60 Interview, 16.4.1999.

61 Interview, 15.4.1999.

62 Widlok (1999), Suzman (2001), Biesele & Hitchcock (2011), Koot (2023)

63 Widlok (1999: 260); see also Dieckmann (2007)

64 Widlok (1999: 261)

65 GRN (2010), LAC (2013)

66 GRN (2010: 30)

67 LAC (2013)

68 Ibid., p. 88

69 Interview, 27.1.1999.

70 Note that nuance is needed here. Some Haiǁom had acquired agricultural knowledge through service to others, as described above. We do not intend to convey an essentialised representation of Haiǁom as knowing about hunting and gathering only.

71 Harring & Odendaal (2002), GRN (2010)

72 (2006: 18)

73 Harring & Odendaal (2007)

74 See also Nawatiseb (2013)

75 See, for instance, Sullivan (2003), Hays (2009), Hitchcock (2012), Taylor (2012), Dieckmann, Thiem, Dirkx, et al. (2014), Van der Wulp & Koot (2019)

76 Hüncke (2010), Castelijns (2019), Koot & Hitchcock (2019)

77 Dieckmann (2007), LAC (2013), Castelijns (2019), Koot (2023)

78 Interview, 2016-2017, cited in Castelijns (2019: 24)

79 Asino (2014), Castelijns (2019)

80 Koot & Hitchcock (2019)

81 Dieckmann, Thiem, Dirkx, et al. (2014)

82 Interview, 18.4.1999.

83 Hüncke (2010)

84 Berndalen (2010)

85 Hüncke (2010)

86 Dieckmann (2007)

87 Interview, 16.4.1999.

88 Castelijns (2019)

89 Interview, 22.11.2009, cited in Hüncke (2010: 26)

90 Ibid., p. 42

91 Interview, 29.9.2009, cited in Hüncke (2010: 43)

92 Hüncke (2010), Castelijns (2019)

93 Interview, 2016-2017, cited in Castelijns (2019: 27)

94 Castelijns (2019)

95 Morton (1994)

96 Koot (2023)

97 GRN (2000), Dieckmann & Begbie-Clench (2014)

98 Suzman (2001), Dieckmann & Begbie-Clench (2014)

99 Widlok (1999), Biesele & Hitchcock (2011), Dieckmann & Begbie-Clench (2014)

100 Dieckmann (2003, 2007)

101 GRN (2000)

102 Hitchcock (2015: 10); see also Dieckmann (2014)

103 Koot & Hitchcock (2019)

104 Ibid.

105 GRN (2010), Hüncke (2010)

106 GRN (2010: 130)

107 Hüncke (2010)

108 Castelijns (2019: 30)

109 LAC (2013)

110 Public notice by the Executive Director Ms. Ndiyakupi Nghituwamata of the MAWLR; also Terblanché (2023)

111 Fabinyi et al. (2010)

112 Widlok (1999), Hüncke (2010), LAC (2013), Dieckmann, Thiem, Dirkx, et al. (2014), Castelijns (2019), Koot & Hitchcock (2019)

113 GRN (2018), Melber (2019)

114 Hitchcock & Vinding (2004: 15)

115 Hüncke (2010: 27)

116 Castelijns (2019: 26)

117 This differs from a municipality: a settlement is a smaller formal governmental body that will be managed by an employed Chief Administrator with a settlement committee. They will be responsible for service deliveries within the proclaimed settlement area.

118 Cited in Simasiku (2020)

119 Ibid.