Etosha-Kunene conservation conversations:

An introduction

©2024 S. Sullivan, U. Dieckmann & S. Lendelvo, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0402.00

Abstract

This introductory chapter describes how the Etosha-Kunene Histories research project, for which this edited volume forms a key contribution, addresses the challenge of conserving biodiversity-rich landscapes in Namibia’s north-central and north-west regions, while reconciling historical contexts of social exclusion and marginalisation. This edited volume, originating from an international workshop held in July 2022, explores the intricate interplay between local and global events shaping the “Etosha-Kunene” conservation landscape. The workshop featured diverse participants from Namibian institutions, international universities, and various conservation organisations. Our discussions emphasised the complex histories and contemporary dynamics of conservation policies, highlighting the tension between biodiversity protection and social equity. The volume is organised into five parts: historical policy analysis, post-Independence conservation approaches, ecological management issues, the impact of historical contexts on contemporary landscapes and communities, and lion conservation within Community-Based Natural Resource Management frameworks. This work aims to contribute to sustainable and inclusive conservation practices that honour both the region’s natural and cultural heritage.

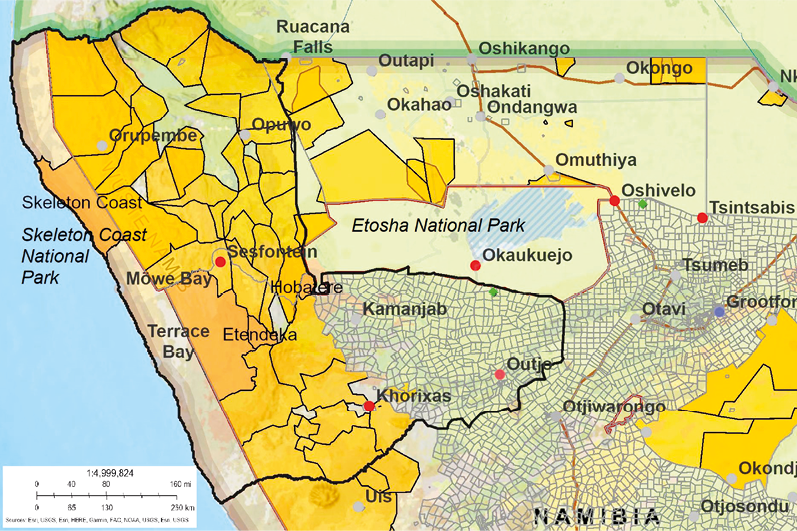

Map of “Etosha-Kunene”. The pale orange areas are conservancies on communal land; the darker orange areas are tourism concessions; the hatched areas show the boundaries of freehold farms held under private tenure; the solid black line is the boundary of Kunene Region. Etosha National Park (ENP) is in the centre, and the pale shaded areas in the west constitute the Skeleton Coast National Park (SCNP). The green markers are the Haiǁom resettlement farms Seringkop and Ondera, to the south and east of ENP respectively. © Ute Dieckmann, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Introduction

How can the conservation of biodiversity-rich landscapes come to terms with the past, given historical contexts of social exclusion and marginalisation? This question anchors the Etosha-Kunene Histories research project,1 for which this edited volume forms a key contribution. The volume brings together presentations shared in an international online workshop held in July 2022 and entitled “Etosha-Kunene Conservation Conversations: Knowing, Protecting and Being-with Nature, from Etosha Pan to the Skeleton Coast”, complemented by additional relevant contributions.2

Our aim with this workshop was to support an in-depth, cross-disciplinary, multi-stakeholder conversation about conservation histories and concerns, focusing on the variously connected “Etosha-Kunene” areas of north-central and north-west Namibia. This regional focus stretches from the resettlement farm of Tsintsabis to the east of Etosha National Park (ENP), westwards to the Skeleton Coast National Park (SCNP) along the Atlantic Ocean, as shown in the above map. These national parks and their neighbouring conservation designations comprise shifting, overlapping and contiguous territories that are also home to diverse Indigenous3 and historically marginalised peoples. In bringing together an array of perspectives on this specific region, we emphasise the complex historical and contemporary weave of ‘local and global events and processes’4 that have worked together to create “Etosha-Kunene” today as a globalised conservation and cultural landscape.5

Participants in our July 2022 workshop came from diverse backgrounds in relation to the Etosha-Kunene regional focus of our project. In Namibia they included the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT), the Lion Rangers Programme, Save the Rhino Trust (SRT), the University of Namibia (UNAM), Ongava Research Centre, Gobabeb Namib Research Institute, Etendeka Mountain Camp and Tsintsabis Trust. We also welcomed colleagues from Oxford Brookes University, the University of the Witwatersrand, the University of Aberdeen, Universität Hamburg, School for Field Studies—Kenya Programme, the University of Göttingen, and the University of Wageningen; as well as Etosha-Kunene Histories project researchers at Bath Spa University, the University of Cologne and UNAM. The present volume represents this diversity. It also follows an established praxis in “Namibian Studies” of bringing together work by authors at different moments of their academic and professional careers.6

As acknowledged by the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for 2015-2030, this is a global moment saturated with simultaneous losses in biological, linguistic and cultural diversities.7 SDG15 concerning Life on Land thus aims to ‘ensure the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems’ (SDG15.1), in part through protecting globally agreed ‘key biodiversity areas (KBAs)’.8 Listed KBAs include Etosha National Park (ENP) and the Hobatere Tourism Concession on ENP’s western boundary. Ecosystem and biodiversity protections, however, can sit uneasily with other SDGs, such as SDG10 aiming for equitable development and reduced inequalities alongside political inclusion, irrespective of differences such as ethnicity, sex, age and gender identity (SDG10.2).

To respond to these potential sources of complexity and friction, we aimed for our workshop to provide a platform for a conversation on conservation policies and practices in “Etosha-Kunene”, taking historical perspectives and diverse natural and cultural histories into account. Weaving the manifold histories, knowledges and practices of diverse actors together with various historical and contemporary conservation policies and practices will, we hope, contribute positively to future conservation aspirations and practices for the region.

The territory we are calling “Etosha-Kunene” stretches from Etosha Pan to the Skeleton Coast, and has been subjected to a long history of nature conservation initiatives. In 1907, “Game Reserve No. 2” was established by the former German colonial state of Deutsch-Südwestafrika (1884–1915) as one of three Game Reserves (Wildschutzgebiete) in which access to so-called “game” animals was restricted—on paper at least, given the enormous land areas involved and the difficulties of policing these areas. Game Reserve No. 2 stretched in varying configurations from the current ENP to the Kunene River in the north-west and the Atlantic Ocean in the west, with diverse peoples living in this area. During the time Namibia was formally governed by South Africa (1920–1990), various boundary changes took place for political and ecological reasons.9 Etosha National Park in the east (declared a National Park in 1967), and SCNP along the Atlantic Ocean in the west (declared a National Park in 1971), were established according to a model of fortress conservation, i.e. protecting nature from people. Commercial hunting and tourism concessions were also created in the space between these two formal conservation territories. Conservation policies and practices in these colonial and apartheid periods are reviewed in detail in Chapters 1 and 2.

After Namibia gained Independence in 1990, the government addressed the legacy of colonial conservation politics through several governance reforms. Being part of remaining communally-managed land, areas west and north of ENP became deeply woven into Community-Based Natural Resources Management (CBNRM) approaches through the establishment of communal area conservancies, community forests and contractual arrangements with tourism concessions and investors.10 In these communal land areas, the emphasis has instead been on protecting nature with people—as reviewed in Chapter 3. Numerous conservancies and community forests west and north of ENP are now present in Etosha-Kunene, where Indigenous and local Namibians are encouraged to become aligned with externally sourced entrepreneurial investments in lodge developments, eco-tourism, trophy hunting, commercial wildlife butchery, and the harvesting of indigenous plants as primary resources for commercial products.

Conservancies are additionally now tapping into and becoming subjects of new conservation arrangements called People’s Parks or People’s Landscapes, as permitted in the draft Wildlife and Protected Areas Management Bill (2017) (see Appendix). In north-west Namibia, these have included a “Kunene People’s Park” proposed in the late 2000s (but not formalised),11 and an “Ombonde People’s Landscape” involving communal area conservancies immediately to the west of ENP.12 The area between ENP and the west is also the focus of a new ‘Skeleton Coast-Etosha Conservation Bridge’, through which the area is being framed explicitly as a ‘conservation hotspot’.13 Implemented by Namibian NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations) WWF Namibia14 and Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC),15 this conservation project has been granted funding of USD 50 million over 50 years through a newly formed Legacy Landscapes Fund led from Germany. Situated in a context of controversial calls to allocate half the earth to conservation,16 as well as so-called “30x30” proposals that 30% of the planet should be protected for conservation by 2030,17 these global initiatives are clearly playing out through intensifying conservation designations in Namibia’s north-west.

In the east of Etosha-Kunene, characterised by the commercial farming area under freehold land tenure, Indigenous Khoekhoegowab-speaking Haiǁom (frequently named “Bushmen”) were provided with a number of resettlement farms.18 Here, the establishment of conservancies and community forests is currently not an option for Indigenous communities. Instead, resettlement within an agricultural development dictum is taking place, affirming boundaries between nature and people/livestock, and between the ENP and the farming sector (see Chapters 2, 4 and 16).

In sum, Etosha-Kunene bears witness to manifold, changing, continuing and parallel nature conservation policies and practices over the last 120 years—as distilled in the Appendix on conservation legislation and policies. Conservation designations through the area have shifted radically and continue to be fluid and dynamic. Conservation policy and legislation has also changed in order to support these various designations, as have the key actors and organisations operating in the business of conservation. Amidst this complexity, our position is that recognising the diversity of histories, cultures, and natures in this internationally valued region will support conservation laws and practices that connect natural and cultural heritages in Namibia (and beyond). Part I of this volume thereby engages with the ‘weight of history’19 shaping new conservation proposals and their outcomes.

How this book is organised

This book is organised into five parts. The first provides an historical backdrop for the book’s detailed case studies, focusing on environmental and conservation policy and legislation, and their implications. The second provides a series of case studies investigating post-Independence approaches to conservation, with the third focusing on Etosha-Kunene ecologies and related management issues. Part IV explores how historical circumstances have shaped contemporary conservation and cultural landscapes, and the final part addresses the specific complexities of conserving predators—in this case lions (Panthera leo)—in combination with Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM). We close with a concluding chapter that weaves together the threads of these contributions to consider present challenges in realising conservation in north-west Namibia. The remainder of this introduction summarises these parts and chapters to clarify the matters of concern explored throughout this volume. We also include short abstracts at the start of each chapter so that they can “stand alone”.

Part I, entitled Conservation Histories in Etosha-Kunene, engages in depth with histories of environmental and conservation policy and legislation, as these have played out in Etosha-Kunene. It is built around three extended chapters by the book’s editors,20 intended to set the historical scene for the detailed case material comprising the book’s remaining chapters.

In Chapter 1, on ‘Etosha-Kunene, from “pre-colonial” to German colonial times’ (Sullivan, Dieckmann, Lendelvo), we outline pre-colonial21 and German colonial structuring of the area, leading in the early 1900s to the institution of formal “game laws” and “game reserves” as key elements of colonial spatial organisation and administration. We provide an overview of the complex factors shaping histories and dynamics prior to formal annexation of the territory by Germany in 1884. We summarise key Indigenous-colonial alliances entered into in the 1800s, and their breakdown as the rinderpest epidemic of 1897 decimated indigenous livestock herds and precipitated enhanced colonial control via veterinary measures and a north-west expansion of military personnel. A critical and collaborative Indigenous uprising in the north-west in 1897–1898—known variously as the Swartbooi or Grootberg Uprising—was met by significant military force, disrupting local settlement and use of the area stretching from Outjo towards the Kunene River.22 It resulted in the large-scale deportation of inhabitants of the area who were brought to Windhoek for mobilisation as forced labour for the consolidating colony. An intended effect was to clear land poised for appropriation by German and Boer settler farmers.

In the wake of the later genocidal colonial war of 1904–1908 that seized land and livestock from African populations, in 1907 the German colonial administration proclaimed an area of north-western Namibia as one of three Game Reserves in German South-West Africa. This area, stretching from Etosha Pan in the east, north-west to the Kunene River bordering Angola, and west to the Atlantic Coast, was not an “untamed wilderness”. Instead, it was inhabited by an array of Indigenous peoples speaking different languages: Khoekhoegowab-speaking Damara/ǂNūkhoen, Haiǁom, Nama and ǁUbun; otjiHerero-speaking ovaTjimba, ovaHimba and ovaHerero; and oshiWambo-speakers (AaNdonga, Aakwaluudhi and Aakwambi) especially north of Etosha Pan. The pre-colonial and early colonial situation was highly dynamic, in terms of mobility, shifting affiliations and alliances, as well as the effects of early colonisation, trade, exploration and missionary activities. The proclamation of Game Reserve No. 2 can be seen as the beginning of a long and varied history of formal colonial nature conservation in Etosha-Kunene, whose shifting objectives, policies and practices had tremendous influence on its human and beyond-human inhabitants.

We follow this early history with an overview of conservation policy and legislation and its impacts, from the territory’s post World War 1 administration from Pretoria, to the formalisation of an Independent Namibia in 1990. In Chapter 2 on ‘Spatial severance and nature conservation: Apartheid histories in Etosha-Kunene’ (Dieckmann, Sullivan, Lendelvo), we trace the history of nature conservation in Etosha-Kunene during the times of South African government. In the initial phase, nature conservation—or rather, “game preservation”—was not high on the agenda of the South African administration, which focused instead on white settlement of the territory, implementing a settlement programme with extensive support for (poor) white South Africans to settle in “South West Africa”. This settlement programme implied a continuous re-organisation of space. The border between the protected “Police Zone” where settlement could take place in the southern and central parts of the territory, and the north of the country where Indigenous people remained, became drawn on to maps of the country and known as the “Red Line”.23 Native Reserves of the German administration were retained and new Native Reserves were established all over the country, in part to provide a labour pool for the colony. The focus of the administration changed after World War 2. White settlement of the territory had almost reached its limits and the potential of tourism and the role of nature conservation for the economy was given more attention. Nature conservation became institutionalised and “scientised”,24 the concept of fortress conservation becoming the dominant paradigm. Its implementation led to the removal of local inhabitants from their former land, among them Haiǁom who had long been living in the south-eastern part of Game Reserve No. 2 (also see Chapters 4, 15 and 16). Shifting boundaries of Game Reserve No. 2—reflecting diverse colonial interests (e.g. settlement, “native” policy, nature conservation)—characterised the 1950s to the 1970s. Part of Game Reserve No. 2 became Etosha Game Park in 1958 and finally ENP in 1967, which, at its current size, was eventually completely fenced in 1973. The arid area along the coast was proclaimed as SCNP in 1971. The previously dominant focus on game preservation was broadened, and, with the Nature Conservation Ordinance of 1967, the more holistic concept of nature conservation was institutionalised and legislated.

During the 1960s, however, appointment of the Commission of Enquiry into South-West Africa Affairs (known as the “Odendaal Commission” after its Chairman “Fox” Odendaal) changed the direction to some extent. The Odendaal Plan, comprising the Commission’s recommendations, was mostly concerned with the implementation (and justification) of redistributing land under an apartheid (“separate development”) system, and put little consideration into the intra-dependence of (socio-)ecological systems.25 Its recommendations entailed “perfecting” spatial-functional organisation with neat boundaries between “Homelands” for the various local inhabitants, the (white) settlement area and game/nature. Land, flora and fauna, and humans of various backgrounds, were treated as separable categories to be sorted and arranged according to colonial needs and visions. The new arrangement imagined ENP as a fenced island within the wider colonial system. This dismembering had unforeseen effects, e.g. increase in animal diseases, the collapse of the ungulate population in ENP, and concerns regarding the sustenance of wildlife in Kaokoveld (northern Kunene Region). The removal of humans from their former lands and beyond-human companions, which had started decades before the Odendaal Plan was implemented, combined with new concentrations of people as the Homeland areas became established. Some outcomes included complex situations of dependency on the administration, social and economic impoverishment, as well as new opportunities in some cases. This complexity was the legacy bequeathed to the new Namibian government at Independence in 1990.

In Chapter 3, on ‘CBNRM and landscape approaches to conservation in Kunene Region, post-Independence’ (Lendelvo, Sullivan, Dieckmann), we review how national post-Independence policy supporting CBNRM has played out in Etosha-Kunene.26 We also highlight a new impetus towards a “landscape approach” for conservation in communal areas, supported by emerging national policy—the Wildlife and Protected Areas Management Bill—which includes the possibility of establishing “contractual parks” (see Appendix), currently more often “People’s Parks” or “People’s Landscapes”. We review this emerging landscape conservation approach, drawing on interviews by Lendelvo with stakeholders and local people living and working in communities adjacent to ENP.

Communal land immediately to the west of ENP—comprised of the Kaokoland and Damaraland Communal Land Areas (Communal Land Reform Act, 5 of 2002)—is currently divided into a series of communal area conservancies, inhabited by pastoralist populations relying additionally on varying combinations of horticulture, gathering and hunting, and waged employment (see Chapters 5, 6, 7, 13, 14). The legal community conservation approach in Kunene Region is primarily based on agreed-upon boundaries for land designated as conservancies and community forests with local members. A new donor-funded impetus towards creating larger connected conservation areas that broaden access and benefits from natural resources is now noticeable. For example, and as noted above, there have been proposals in the past to establish a Kunene People’s Park that would connect the Hobatere, Etendeka and Palmwag Tourism Concessions,27 although these were never formalised. Proposals for a People’s Park were reignited in 2018 with international support from conservation donors and the British royal family.28 Present proposals for an Ombonde People’s Landscape and other landscape level initiatives are being implemented by the MEFT with the support of the Environment Investment Fund (EIF), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the German Society for International Cooperation (GIZ) and other agencies. Chapter 3

reviews the emerging landscape conservation approach, focusing on the Ombonde People’s Landscape, comprised of the southern parts of Omatendeka and Ehi-Rovipuka conservancies which sit in the Damaraland Communal Land Area. Drawing on interviews with stakeholders and local people in these two conservancies, the chapter explores “human-wildlife conflict”, climate change and integrated management of natural resources in conservancy land areas zoned for different types of use.

In Part II on the ‘Social lives of conservation in Etosha-Kunene, post-Independence’, we follow our historical overviews in Part I with a series of detailed case studies of how approaches to conservation have played out in Etosha-Kunene after 1990. The chapters here focus on the shifting land designations, boundaries and memberships constituting conservancy governance and resettlement farms for those displaced in part through the establishment of areas protected for nature conservation. In doing so, they tease out the complexities at play as communal-area and displaced residents have adjusted to, and engaged with, new post-Independence resource management circumstances. Critical here is how an array of state and non-state actors and organisations—including NGOs, donors, private sector investors, the MEFT and other government ministries—intersect with and determine possibilities and constraints for local circumstances.

In Chapter 4 on ‘Haiǁom resettlement, legal action and political representation’, Ute Dieckmann explores the destiny of Haiǁom after they were evicted from Etosha in the 1950s.29 Differently to communities further west, Haiǁom were not provided a “Homeland” through implementation of the 1964 recommendations of the Odendaal Commission, but instead were left without any land. They became landless farm labourers and often, after Independence, township dwellers, with very little means of subsistence (also see Chapters 15 and 16). A few found employment within ENP, which entailed a more secure life and, for the men at least, continuous, although severely changed, access to their former land. Since they did not live in designated communal areas, Haiǁom had no opportunity to establish conservancies after Independence. Recognising the fate of the Haiǁom in around 2007 at the time of the centenary celebrations of ENP, the government commenced some efforts to compensate them by purchasing several farms for their resettlement in the vicinity of the park. Since 2008, at least eight farms, seven of them bordering ENP in the south, were bought for the resettlement of Haiǁom. Initially (around 2007), one of the primary target groups for resettlement was the Haiǁom community still residing within ENP, of whom only a minority were employed. However, most of the Haiǁom residents in ENP resisted their relocation at the start, fearing they would lose all access to the park, i.e. their ancestral land, once they had agreed to be resettled on the farms.

In 2015, with years of preparation and initiated by Haiǁom still living in Etosha, a large group of Haiǁom from various areas, dissatisfied with the resettlement approach by the government, launched a legal claim to parts of their ancestral land (mainly ENP).30 Chapter 4 outlines these developments, paying attention to the rather ambivalent role played by the Haiǁom Traditional Authority (TA). The chapter draws on long-term field research with Haiǁom as well as employment by an NGO in Windhoek, supporting San and other marginalised communities. It also looks at recent developments and argues for the inclusion of Haiǁom cultural heritage in the future planning and implementation of nature conservation and tourism activities in the Etosha area.

In Chapter 5 on ‘Environmentalities of Namibian conservancies: How communal area residents govern conservation in return’, Ruben Schneider examines how residents in communal areas in north-west Namibia experience, understand, and respond to their conservancies. Schneider offers a theoretically nuanced analysis drawing on philosopher Michel Foucault’s concept of governmentality—i.e. practices of government or the ‘conduct of conduct’,31 working specifically with its ‘environmentality’ variant, i.e. the art of government in relation to environmental dimensions.32 Schneider thereby frames conservancies as localised global environmental governance institutions, which aim to modify local people’s behaviours in conservation- and market-friendly ways.33 Based on year-long ethnographic fieldwork across four conservancies in Kunene Region, the chapter reveals how local communities culturally demystify, socially re-construct, and ultimately govern a global, neoliberal(ising) institutional experiment in return. It highlights divergent ways in which local people experience the pivots of the conservancy system characterised by benefits and a sense of ownership over natural resources. Confirming stark experiential discrepancies and distributional injustices, the chapter positions itself against a simplistic affirmation of the conservation dictum that ‘those who benefit also care’.

In contrast, the chapter argues that experiences of neoliberal incentives like ownership and benefits are a limited predictor of local conservation practices. The extent to which local people cooperate or resist conservation does not only depend on the global modes of governance that conservancies aim to localise, but are critically shaped by the local structures, desires, and agencies through which they operate on the ground. In the context of Namibian conservancies, this ‘friction’34 between global and local ways of seeing and being in the world produces novel, hybrid environmentalities characterised in part by what political scientist Jean-François Bayart calls ‘the politics of the belly’.35 Examining the nature and effects of this hybrid environmentality, the chapter explores how communal-area residents seek to opportunistically work the conservancy system to their maximum advantage. This situation highlights an accountability gap within conservancies which not only entrenches local inequalities but effectively transfers frictions between global and local environmentalities to the community level where they have the potential to develop into protracted intra-community conflicts. Importantly, though, any resources “captured” by communal area residents and negotiated within the membership of conservancies, can be understood as “leftovers” from dominant processes of resource appropriation and capital accumulation by more powerful state, NGO and private sector networks and investors. To conclude, the chapter argues that conservancies might no longer displace, but instead promote alternative environmentalities that may reflect Indigenous beliefs, intrinsic values, and non-dualistic ontologies (as considered in Chapters 12, 13, 14 and 15).36 To the extent that neoliberal logics remain, the chapter calls for additional oversight, support, mediation and, if necessary, re-regulation of conservancies. As forewarned by both Foucault37 and Elinor Ostrom,38 if inequality is to be opposed, neoliberal environmentality has to be kept in check, irrespective of whether it works through global or local networks.

In ‘The politics of authority, belonging and mobility in disputing land in southern Kaoko’ (Chapter 6), Namibian researcher Elsemi Olwage continues the theme of how conservancies in Namibia’s north-western communal rangelands have been entangled with contestations over land and territory, since their onset and mapping from the late 1990s.39 The focus of this chapter concerns the interwoven politics of authority, belonging and mobility in shaping “customary” land-rights in southern Kaoko. Olwage argues that ancestral land-rights need to be understood as a social and political rather than a historical fact, and one which is relationally established and re-established in practice, over time, and at different scales. The chapter draws on research conducted from 2014 to 2016 comprising a situational analysis of a land and grazing dispute in southern Kaoko, in and around Ozondundu Conservancy, north-east of Sesfontein. It shows how persons and groups were navigating overlapping institutions of land governance during an extended drought period, in a context shaped by regional pastoral migrations and mobility. Olwage unpacks the politics of authority and belonging in integrating newcomers and migrating households within places, and illustrates the range of social, spatial, legal, political, normative, and discursive practices that different groups and persons drew on to legitimise, de-legitimise or contest such integration. She shows how conservancies and state courts have become key technologies mobilised to re-establish the interwoven authority and land-rights of particular groups. This development is connected with a post-Independence shift towards more centralised state-driven land governance, deeply rooted political fragmentation within most places, and land-grabbing by some migrating pastoralists. The chapter concludes by arguing for the importance of engaging socially legitimate occupation and use rights, and decentralised practices of land governance, towards co-producing ‘communal’ tenure and land-rights between the state and localities. This emphasis is critical for evidence-based decision-making and jurisprudence in a legally pluralistic context.

Chapter 7 by Diego Menestrey Schwieger, Michael Bollig, Elsemi Olwage and Michael Schnegg shifts from land and boundaries to consider the management of water in Etosha-Kunene. ‘The emergence of a hybrid hydro-scape in northern Kunene’ starts from the position that political ecology approaches, and recent theories on institutional dynamics, often neglect the materiality of infrastructures linked to resource management and its social-ecological implications. Specific technologies in a particular landscape have deep histories and “contain” sediments of past local-state engagements and place-based practices. This has been the case in north-western Namibia, where a unique ‘hydro-scape’ has emerged. Before the 1950s, the area was characterised by a scarcity of permanent water places and sources. Between the 1950s and the 1980s, the then-ruling South African administration drilled hundreds of boreholes in the region as part of its apartheid “homeland” policy and “modernisation” impetus.40 Initially, local leaders and traditional authorities rejected the idea of water development through borehole drilling; many felt that once such a complex and expensive infrastructure was operational, the state was there to stay as the guarantor of the basic hydro-infrastructure for vast herds of livestock. The state’s representatives were blamed vociferously for the colonial state’s cunning way of luring people into such entrapping dependencies. Despite this situation, the state financed a burgeoning drilling programme. These water infrastructures—boreholes with different pumping technologies, such as wind and diesel pumps—were the medium for the state to root its power and presence in the region.

Since 1990, the independent Namibian state continued the borehole-drilling programme, especially as part of its drought-management approach. From the 1990s onwards, responsibility for maintaining the above-ground infrastructure of boreholes was transferred to local pastoral communities. The idea was that self-reliant communities would manage these boreholes sustainably and that the state would only become involved once major underground repairs were necessary. This “handover” process had to follow state-prescribed institutional designs to construct local institutional structures through which the boreholes could be collectively and sustainably managed. Hence, after establishing an entirely new hydro-infrastructure, the state expanded its reach by implementing the social infrastructure of this hydro-scape along with global blueprints for the sustainable management of communal goods. In the end, however, the material infrastructure opened the door for national and global governance regimes which increasingly permeated communities as the state began to “withdraw” through community-based management policies. These blueprints are not implemented verbatim by local agents, however. The result is a dynamic bricolage of institutions shaped by different practices, power relations, norms, and values. Nowadays, local communities reliably maintain water supply, but not always on an equitable basis for all users.

In the final chapter of Part II, Likeleli Zuvee Katjirua, Michael Shipepe David and Jeff Muntifering turn to research with young people in north-west Namibia to ascertain their perceptions and understandings of “wildlife”. Chapter 8 on ‘Eliciting empathy and connectedness toward different species in north-west Namibia’ seeks to better understand how young members of communal-area conservancies in north-west Namibia know and perceive the value of selected indigenous fauna in these areas, alongside domestic livestock. It is set within a context in which tourism in Namibia is understood to greatly contribute to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), with Namibia home to animals whose value is linked with their contemporary scarcity. Such species include black rhino (Diceros bicornis bicornis)—monitored and celebrated through organisations and campaigns such as Save the Rhino Trust and the Rhino Pride Campaign—as well as lion (Panthera leo) (considered in more depth in Part V), and oryx (Oryx gazella), all of which draw tourists to Namibia. Whilst these wild animals need to be protected at a global level, nationally they are also “Namibia’s pride”, notably being pictured on Namibian bank notes.

Geographically these animals are located in areas lived in by communities and managed as communal area conservancies. As outlined in Chapters 3 and 5, conservancies are intended to protect these animals whilst also catering and caring for the communities around them. One of the most important factors in protecting and preserving animals in conservancies is the participation of community members, for which awareness and knowledge about the importance of different animal species and their rarity needs to be shared and exchanged. In the survey ‘Connectedness with Nature Experience’ reported on in this chapter, the aim was to understand the experience young community members have with wild animals (indigenous fauna), in comparison to domestic animals. The animals used in the survey were rhinos, lions, oryx and goats (Capra hircus). The survey was intended to illustrate and illuminate how young community members understand the importance of these animals, and how they can benefit from them by assisting in their protection.

In Part III we engage more closely with Etosha-Kunene Ecologies to consider complex ecological factors and dynamics for conservation praxis and management. The focus here is also extended in Part V through three chapters focusing on lion ecology, monitoring and CBNRM in Namibia’s north-west.

We open Part III with a focus on vegetation and herbivory. Chapter 9, by Kahingirisina Maoveka, Dennis Liebenberg and Sian Sullivan, is entitled ‘Giraffes and their impact on key tree species in the Etendeka Tourism Concession, north-west Namibia’. It reports on a study that researched the impacts of browsing giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis angolensis) on the important pollinator trees Maerua schinzii (ringwood tree) and Boscia albitrunca (shepherd’s tree) within the Etendeka Concession area. Historically, giraffe populations have been amplified here through translocations designed to enhance tourism. The concession is located in mopane (Colophospermum mopane) savanna, semi desert and savanna transition vegetation zones. Due to browsing by giraffe, M. schinzii and B. albitrunca trees develop a distinctive shape with only a small, round canopy of leaves above a very high browse line. Giraffe are selective browsers, and the tallest land animal. Direct observation of giraffes feeding in the field indicates that they browse on leaves and twigs at different heights, depending on how high they can reach, with males browsing on tall trees and females seeming to prefer to bend their necks down to browse on lower trees and shrubs. The study also explored five different techniques to protect M. schinzii and B. albitrunca from further browse damage by giraffes.

Chapter 10 by ǂKîbagu Heinrich Kenneth |Uiseb, entitled ‘Are mountain and plains zebra hybridising in north-west Namibia?’, focuses on interactions between two animal species critical to the ecosystems of Etosha-Kunene. Against a background of biodiversity loss due to anthropogenic changes to the environment, with human impacts observed from the modification of ecosystems to the extinction of species and the loss of genetic diversity, this chapter considers how human alteration of the physical landscape can affect gene flow by influencing the degree of contact between groups of individuals of a species. Large herbivore species are increasingly restricted to fenced protected areas, a situation that limits their opportunities for dispersal and access to natural water sources. This restricted movement may lead to genetic consequences including the disruption of gene flow, inflation of “inbreeding”, and the loss of rare alleles supporting local adaptation and genetic fitness. Many protected areas located in Africa make use of artificial water points to provide water for wildlife in the dry season, which may alter wildlife distribution as some herbivores no longer need to migrate and become localised. This localisation can cause rapid population increase of water-dependent species such as zebra, increasing competition with more vulnerable low-density species and altering interspecies interactions.

Namibia’s large protected area of ENP is home to two zebra species: mountain zebra (Equus zebra) (specifically the subspecies E. z. hartmannae) and plains zebra (E. quagga) (specifically the subspecies E. q. burchellii). Mountain zebra are restricted to dolomite ridges in the far western section of the park while plains zebra occur throughout the park. Fenced in 1973, artificial water points were also established from the 1950s to improve the wildlife-viewing experience for tourists. There are now over 100 perennial watering points in the Park, including artesian springs, contact seeps and 55 boreholes. Park boundary fences erected in the 1970s and extending to over 850 km also block wildlife dispersal beyond the park boundaries. Historically, the overlap in range of the two zebra species was limited, as plains zebra confined their movements to the southern and eastern edges of the Etosha Pan during the dry season, and to the open plains west of the Pan during the rainy season. Mountain zebra in the park are restricted to the rocky and mountainous western section of the park, and the west of the park into the escarpment, with plains zebra occurring at a higher density throughout the park compared to mountain zebra. Artificial provision of perennial water sources throughout the park has led to plains zebra expanding their range to overlap extensively with the mountain zebra range in the west. The extended overlap in range of these two previously geographically separated species in Etosha creates a potential conservation problem in the form of hybridisation between the two species. This chapter reviews what is known about the hybridisation of these two species, and considers implications for conservation and for future research.

Chapter 11 by Michael Wenborn, Roger Collinson, Siegfried Muzuma, Dave Kangombe, Vincent Nijman and Magdalena Svensson focuses on a key species for conservation in Etosha-Kunene, namely elephant (Loxodonta africana). Entitled ‘Communities and elephants in the northern highlands, Kunene Region, Namibia’, the chapter considers a unique population of this species dwelling specifically in the northern highlands between ENP and SCNP. These highlands are a remote, arid, mountainous landscape where elephants co-exist with rural communities. There is minimal published research on this population of elephants. As part of the authors’ extended scoping for a research project on this population of elephants, they consulted with game guards from 10 conservancies in 2021 and 2022 on their knowledge of elephant populations: also carrying out analysis of Event Book data on human-elephant conflict (HEC) incidents reported in Orupupa and Ehi-Rovipuka conservancies.

The community conservancy model has had much success in shaping local attitudes in Kunene Region and increasing the perceived value of wildlife (see Chapters 3 and 8).

The findings from the consultation indicate, however, that these successes are being eroded by the increasing competition between local people and wildlife over resources, particularly in the context of drought years in north-west Namibia between 2013 and 2020 (also see Chapters 5 and 6). There was a particularly high loss of livestock during the droughts of 2018–2019, after which many local people in the highlands set up vegetable gardens as an alternative livelihood. The authors’ consultations with game guards and analysis of Event Books have shown that this has increased incidents of HEC and brought some incidents nearer to villages, which is negatively impacting local attitudes to elephants. Many game guards employed by conservancies have worked here for 10 to 20 years and have detailed local ecological knowledge. We conclude that there is a strong case for expanding the roles of game guards to strengthen the protection of the elephants in the northern highlands. Part of this effort would include training them as elephant rangers to guide tourists in the area, an assumption being that this would increase revenue to community conservancies and help enhance local perceptions of the value of wildlife.

In Part IV we return to historical circumstances, taking a deeper dive into the histories shaping present issues, opportunities and concerns for specific conservation areas across Etosha-Kunene. In ‘Historicising conservation and community territories in Etosha-Kunene’, we work from west to east across the area, engaging with varied cultural histories linked with these areas: the northern Namib that from 1971 has been designated as the SCNP (Chapter 12); the creation of the Palmwag Tourism Concession and implications for diverse local inhabitants (Chapter 13); what it means to live next to Etosha National Park (Chapter 14); experiences and consequences of eviction from ENP for Haiǁom (Chapter 15); and the specific histories of Haiǁom in connection with the resettlement farm of Tsintsabis to the east of ENP (Chapter 16).

In Chapter 12 on ‘Cultural heritage and histories of the Northern Namib / Skeleton Coast National Park’, by Sian Sullivan and Welhemina Suro Ganuses, we outline Indigenous cultural heritage and histories associated with the Northern Namib Desert. This chapter draws on two principal sources of information: 1) historical documents stretching back to the late 1800s; and 2) oral history research with elderly people who have direct and familial memories of using and living in areas now within the Park boundary. The research shared herein affirms that localities and resources now included in the Park were used by local people in historical times, their access linked with the availability of valued foods, especially !nara melons (Acanthosicyos horridus) and marine foods such as mussels.41 Memories about these localities, resources and heritage concerns, including graves of family members, remain lively for some individuals and their families today. These concerns retain cultural resonance in the contemporary moment, despite significant access constraints over the last several decades. Suggestions are made for foregrounding an understanding of the Northern Namib as a remembered cultural landscape, as well as an area of high conservation value; and for protecting and perhaps restoring some access to sites that may be considered of significant cultural heritage value. Such sites include graves of known ancestors and named and remembered former dwelling places. The material shared here may contribute to a diversified recognition of values for the SCNP with relevance for the new Management Plan42 that will shape ecological and heritage conservation practice and visitor experiences over the next 10 years.

Chapter 13 by Sian Sullivan, entitled ‘Historicising the Palmwag Tourism Concession, north-west Namibia’, moves slightly eastwards from the area considered in Chapter 12.

The chapter focuses on a tourism concession area comprising more than 550,000 hectares of the Damaraland Communal Land Area (as delineated in the Communal Land Reform Act, 2002) in Kunene Region. To the west of this concession lies the SCNP. Otherwise, the concession is situated within a mosaic of differently designated communal lands to which diverse qualifying Namibians have access, habitation and use rights: namely, Sesfontein, Anabeb and Torra communal area conservancies on the concession’s north, north-east and southern boundaries, with Etendeka Tourism Concession to the east (see Chapter 9). Established under the pre-Independence Damaraland Regional Authority led by Justus ǁGaroëb, Palmwag Concession lies fully north of the veterinary cordon fence (VCF), or ‘Red Line’, that marches east to west across Namibia. In the 1950s, however, the Red Line was positioned further north with part of the current concession comprised of a commercial farming area for white settler farmers, the expansion of which was associated with evictions of local and Indigenous peoples. The iterative clearance of people from this area also helped make possible the 1962 western expansion of Etosha Game Park (see Chapter 2), and then the establishment of a large trophy-hunting concession between the Hoanib and Ugab rivers in the 1970s.

The Palmwag Concession today is particularly celebrated for sustaining the largest population of black rhino (D. b. bicornis) outside a protected area, an artefact of a colonial history in which imported firearms aided the removal of these animals throughout southern and central Namibia.43 Tourism establishments now hosted by the concession are amongst those supplying income to the various communal area conservancies on the concession’s boundaries. The area also continues to be considered critical as part of a connected conservation landscape and wildlife ‘corridor’ extending west from the iconic conservation territory of ENP towards the Skeleton Coast. Drawing on archival research, interviews with key actors linked with the concession’s history, and heritage mapping with local elders through much of the concession’s terrain, this chapter places the concession more fully within the historical circumstances and effects of its making. In doing so, competing and overlapping colonial, Indigenous and conservation visions of the landscape are explored for their roles in empowering specific types of access and exclusion. Envisioned, commodified and marketed today as a wilderness and ‘Arid Eden’, the chapter opens up ways that local and historical constructions of the landscape intersect with, and sometimes contest and remake, this vision.

Chapter 14 by Arthur Hoole and Sian Sullivan on ‘Living next to Etosha National Park: The case of Ehi-Rovipuka’, considers in depth the implications of being park-adjacent for ovaHerero pastoralists now living in Ehi-Rovipuka Conservancy. Drawing on Hoole’s PhD research in the mid- to late-2000s, the chapter focuses on three dimensions. First, some aspects of the complex and remembered histories of association with the western part of what is now ENP are traced, via a ‘memory mapping’ methodology with ovaHerero elders.44 Second, experiences of living next to the park boundary are recounted and analysed, drawing on a structured survey with 40 respondents. Finally, extensive local knowledge of wildlife presence in and mobilities through the wider region is documented, and its relevance considered for conservation activities today. Although the research reported here was carried out some years ago, circumstances in Ehi-Rovipuka have changed rather little. Whilst the park boundary now prevents mobilities into western Etosha, peoples’ histories of utilising, moving through, being born and desiring to be buried in the western reaches of the park remain.

In Chapter 15, ‘“Walking through places”: Exploring the former lifeworld of Haiǁom in Etosha’, Ute Dieckmann engages with differing conceptions of the land that has become the protected area of ENP. Etosha National Park is Namibia’s ‘flagship park’ and premier tourist attraction. By tourists, Etosha might be perceived either as an untamed wilderness or a large zoo; for scientists, it might represent an excellent research opportunity to test zoological hypotheses; and for farmers on the border farms, it might be a source of nuisance, its wildlife causing continuous trouble and at times economic loss. For Haiǁom, Etosha represents part of their former lifeworld; an ecology of which they were an integral part. Their ancestors lived across the region alongside other Khoekhoegowab- and San-speaking peoples before the major immigrations of Bantu speakers to this area during the last 500 years of the second millennium.45 White settlers increasingly occupied the surrounding area with the result that nearly all the land (south of the Red Line) formerly inhabited by Haiǁom and others was occupied by settlers in the 1930s. The game reserve became the last refuge where Haiǁom were able to practise a largely hunting and gathering lifestyle. Until the 1940s, Haiǁom were regarded as ‘part and parcel’ of the game reserve. All in all, between a few hundred and one thousand Haiǁom lived in the park until the early 1950s when they were evicted (for historical contextualisation see Chapters 2, 4 and 16). In the first half of the 20th century, they were mainly living from hunting and gathering, with some families keeping a few head of goats or cattle, combined with occasional seasonal work and temporary employment.

Drawing on a cultural mapping project in which Dieckmann was involved, combined with oral history and archival research, this chapter explores the lifeworld of Haiǁom in Etosha and their relations to the land, to other humans and to beyond-human inhabitants, prior to eviction. Tim Ingold’s ‘meshwork’46 is drawn on as a suitable concept for capturing Haiǁom’s being-in-Etosha as being-in-relations. The picture emerging from the research is that of a dense web of land, kinship, human, animals, plants and spirit beings, an integrated ecology and an almost forgotten past which should, in line with this publication’s aim, be acknowledged by and integrated into future nature conservation policies and practices.

Chapter 16, entitled ‘History and social complexities for San at Tsintsabis resettlement farm, Namibia’, by Stasja Koot and Moses ǁKhumûb, continues with the theme of the eviction of Haiǁom from ENP in 1954. After this event, many Haiǁom San became farm workers. Having lost their lands under colonialism and apartheid to nature conservation and large-scale agriculture, most remained living in the margins of society at the service of white farmers, conservationists or the South African Defence Force (SADF). After Independence in 1990, group resettlement farms became crucial to address historically built-up inequalities by providing marginalised groups with opportunities to start self-sufficient small-scale agriculture (see Chapter 4). This chapter critically addresses the history of the Tsintsabis resettlement farm, just over a hundred kilometres east of ENP, where at first predominantly Haiǁom (and to a lesser degree !Xun) were “resettled” on their own ancestral land, some as former evictees from ENP. The authors analyse the history of Tsintsabis in relation to two pressing, and related, social complexities at this resettlement farm, namely: 1) ethnic tension and in-migration; and 2) leadership. The chapter argues that the case of Tsintsabis shows the importance of acknowledging historically built-up injustices when addressing current social complexities. As with Chapters 4, 6, 12, 13 and 15, the chapter emphasises the importance of doing long-term “ethno-historical” research about resettlement so as to be able to better understand the contextual processes within which it is embedded.

In Part V, on ‘People, lions and CBNRM’, we return to the contemporary complexities of CBNRM highlighted in Parts II and III to consider specifically the frictions that may arise as increasing predator populations—considered a conservation success—may impinge on human settlement and livelihoods. In this section we share three chapters by authors working with and for Namibia’s Lion Rangers Programme,47 demonstrating how responses ‘on the ground’ are being developed and enacted to deal with this conservation complexity.

In Chapter 17 on ‘Integrating remote sensing data with CBNRM for desert-adapted lion conservation’, John Heydinger explains how Global Positioning System (GPS) data on lion movements can contribute to community-oriented conservation. Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) takes place at the intersection of protecting and being-with nature (as also outlined in Chapters 3, 5 and 6). CBNRM of the desert-adapted lions presents an array of cultural and scientific challenges to local communities living alongside lions, often colliding with CBNRM principles. Among the most significant challenges to lion conservationists is rigorously monitoring lion movements in unfenced landscapes. Within the semi-arid and arid environments of north-west Namibia, monitoring challenges are compounded by low levels of information relevant to lion habitat-use and movement ecology in dryland areas. Technological advances in remote sensing, however, are creating new ways for researchers and wildlife managers to monitor wildlife and other natural resources. Drawing on remote sensing data collected via satellite-GPS collars affixed to lions, and via trail cameras placed in designated core wildlife areas within communal conservancies and government concessions, Heydinger discusses how remote sensing methods of carnivore monitoring are contributing to lion conservation on communal lands in Kunene.48 He emphasises how these data are being incorporated into the Lion Rangers Programme, a CBNRM initiative in which trained community conservationists take responsibility for monitoring lions and managing human-lion conflict on communal lands. The goal is to integrate technologically sophisticated movement data with CBNRM principles and historically informed perspectives (including in Heydinger’s other research49), so as to catalyse community-centred management of lions on communal lands, and contribute to sustainable livelihoods and in situ lion conservation.

Chapter 18 by Matilde Brassine concerns the ‘Lion Rangers’ use of SMART for lion conservation in Kunene’. SMART is a Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool used to enable rapid collection and transfer of patrol data in order to assess Ranger activities in the field and monitor wildlife movements on an ongoing basis. In north-west Namibia, a small population of desert-adapted lions continues to survive alongside livestock farmers and communities living in conservancies, often resulting in human-lion conflict (HLC) in a context where livelihoods are already strained due to prolonged drought in the region, as well as the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.50 Recognising the urgent need to mitigate this conflict, in 2017 the MEFT drew up a strategy on a way forward in the form of the Human Lion Conflict Management Plan for North West Namibia (NW Lion Plan). The formation of the Lion Rangers Programme is part of this strategy. Lion Rangers are Community Game Guards selected by their communities and employed by their conservancies to monitor desert-adapted lions, and to prevent and respond to HLC incidents. They work closely with their communities to provide education and awareness about lions and lion movement. The SMART system was first implemented into the programme in September 2021. This chapter discusses how the SMART system supports decision-making regarding lion conservation and management at a community-level.

Uakendisa Muzuma in Chapter 19 closes this trio of chapters on community approaches to lion conservation in his discussion of ‘Relationships between humans and lions in wildlife corridors through CBNRM in north-west Namibia’. Protected areas (PAs) are considered essential for conserving large carnivores. Large carnivores also exist outside PAs, however, and have shared landscapes with humans for millennia. Namibia’s CBNRM programme has achieved some successes via tourism, the provision of meat for consumption, and hunting, its aim being to encourage the coexistence of wildlife and rural communities on communal land. Because the programme is built upon human-wildlife coexistence, however, human-lion conflict (HLC) is also present. This has been a pressing challenge, particularly regarding people’s coexistence with dangerous animals such as lions (as documented for elephants in Chapter 11). Although the CBNRM programme has achieved initial success, less emphasis has been placed on understanding how humans, livestock and wildlife use shared landscapes. From a wildlife conservation perspective, one current cause for concern is the lack of monitoring of human settlement and livestock movements into areas zoned for wildlife in communal area conservancies (also see Chapters 3 and 6). This chapter discusses current research on remote sensing of lion and goat movement using satellite-GPS collars, focusing on understanding goat movement ecology within wildlife areas as designated by conservancies and their leaders. Information collected on goat movements within wildlife areas will be used to better manage the shared landscape in the perceived ‘corridor’ between ENP and SCNP. The research shared here thus focuses on the ‘lion-goat space’ to contribute to evidence-based goat spatial habitat use in communal area conservancies, so as to ensure appropriate deployments of HLC mitigation measures.

Our concluding chapter on ‘Realising conservation in Etosha-Kunene’, by Ute Dieckmann, Selma Lendelvo and Sian Sullivan draws attention to some of the main threads forming the fabric of this volume. Etosha-Kunene is a region with both a shared history, which manifested itself in the proclamation of Game Reserve No. 2, and specific local cultural-ecological histories and dynamics. The regional research conveyed in this volume reveals changes through time in both nature conservation politics and practices in Namibia generally, and in Etosha-Kunene in particular. While at the turn of the 19th century, “game preservation” became necessary due to the reckless exploitation of wildlife by especially (but not only) European men interested in their own economic profit and prestige (Chapter 1), the conservation focus broadened during the course of the 20th century to include flora and fauna in conservation initiatives (Chapter 2). At the same time, human inhabitants became increasingly seen as detrimental to conservation efforts culminating in the “fortress conservation” model being employed in Etosha-Kunene with disastrous effects for former human inhabitants. This volume documents some of these historical processes and their effects (Chapters 1, 2, 4, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16).

With Independence, the politics of nature conservation moved away from the fortress conservation model to include local inhabitants in conservation management (Chapters 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 17, 18, 19). This process was not without pitfalls, however, with human-wildlife conflict being one of the challenges (Chapters 11, 17, 18, 19), institutional arrangements another (Chapters 5, 6, 7).

This volume also reveals stories of belongings, alongside negotiations about belongings, inclusions and exclusions. Be it zebras (Chapter 10), elephants (Chapter 11), lions (Chapters 17, 18, 19), livestock (Chapters 2, 8), Khoekhoegowab-speaking communities (Chapters 4, 12, 13, 15, 16), otjiHerero-speaking communities (Chapters 6, 14), hunters (Chapters 12, 13, 14 and 15), or incoming settlers (Chapters 6, 16), our volume reveals a constant querying of who belongs where and when, and who has the power to decide (Chapters 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16).

This question of belonging is connected with the histories of shifting boundary-making and fencing. Boundaries of game reserves were defined on paper and on maps, and the boundaries of Etosha National Park were erected as fences in the landscape (Chapter 2). Boundaries were used to restrict mobility, to separate people from wildlife, and to disentangle constructed categories of people from each other, as well as to disconnect livestock north of the Red Line from livestock south of the Red Line. They were also used to claim land as private property, with recently instituted legal systems used to keep others out. Boundaries restricted access and dismembered socio-ecological systems.

We started our introduction with the question: how can the conservation of biodiversity-rich landscapes come to terms with the past, given historical contexts of social exclusion and marginalisation? We hope this volume will contribute to finding answers, by highlighting the complexities that need to be taken into account, and by describing practices already being enacted.

Our overall aim for this volume is thus to assist with generating ideas for the future design of conservation initiatives that more fully consider and integrate historical and cultural knowledge and diversity. We hope that the original detail shared in this volume, as well as the original combination of contributions in the book, is relevant for those involved with conservation and development work in Namibia, especially its north-west, whether they are conservation practitioners, academics in disciplines ranging from history to environmental science, policy-makers, or people living in the area. Many contributors to the book are directly involved in this world: we hope that they and their colleagues find the book of value in terms of bringing together material and reflections on the complex issues shaping “Etosha-Kunene”. Beyond Namibia, we also hope this book appeals to individuals and organisations involved with conservation more widely. Our volume provides a detailed and unusual combination of analyses regarding different dimensions of conservation circumstances: from historical contexts, to analysis of legal cases, to remote sensing. We hope this combination of analyses is relevant to conservation scholarship, policy and practice, particularly given that north-west Namibia is a focus for iterated conservation effort and concern, for the reasons laid out in this book.

Bibliography

Bayart, J-F. 2009. The State in Africa: The Politics of the Belly. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity.

Berry, H.H. 1997. Historical review of the Etosha region and its subsequent administration as a National Park. Madoqua 20(1): 3–10, https://hdl.handle.net/10520/AJA10115498_453

Bollig, M. 2020. Shaping the African Savannah: From Capitalist Frontier to Arid Eden in Namibia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108764025

Botha, C. 2005. People and the environment in colonial Namibia. South African Historical Journal 52: 170–90, https://doi.org/10.1080/02582470509464869

de la Bat, B. 1982. Etosha. 75 Years. S.W.A. Annual: 11–26.

Denker, H. 2022. An Assessment of the Tourism Potential in the Eastern Ombonde-Hoanib People’s Landscape to Guide Tourism Route Development. Windhoek: GIZ, https://www.irdnc.org.na/pdf/Report-Ombonde-Hoanib-Assessment-of-Tourism-Potential.pdf

Dieckmann, U. 2003. The impact of nature conservation on the San: A case study of Etosha National Park. In Hohmann, T. (ed.) San and the State: Contesting Land, Development, Identity and Representation. Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, 37–86.

Dieckmann, U. 2007. Haiǁom in the Etosha Region: A History of Colonial Settlement, Ethnicity and Nature Conservation. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Dieckmann, U. 2011. The Haiǁom and Etosha: A case study of resettlement in Namibia. In Helliker, K. & Murisa, T. (eds.) Land Struggles and Civil Society in Southern Africa. New Jersey: Africa World Press, 155–89.

Dieckmann, U. 2020. From colonial land dispossession to the Etosha and Mangetti West Land Claim—Haiǁom struggles in independent Namibia. In Odendaal, W. and Werner, W. (eds.) Neither Here Nor There: Indigeneity, Marginalisation and Land Rights in Post-independence Namibia. Windhoek: Legal Assistance Centre, 95–120, https://www.lac.org.na/projects/lead/Pdf/neither-5.pdf

Dieckmann, U. 2021a. Haiǁom in Etosha: ‘Cultural maps’ and being-in-relations. In Dieckmann, U. (ed.) Mapping the Unmappable? Cartographic Explorations with Indigenous Peoples in Africa. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag, 93–137, https://www.transcript-open.de/doi/10.14361/9783839452417-005

Dieckmann, U. 2021b. On ‘climate’ and the risk of onto-epistemological ‘chainsaw massacres’: A study on climate change and Indigenous people in Namibia revisited. In Böhm, S. and Sullivan, S. (eds.) Negotiating Climate Change in Crisis. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 189–205, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0265.14

Eisen, J. and Mudodosi, B. 2021. 30x30 – A brave new dawn or a failure to protect people and nature? Green Economy Coalition 1 November, https://www.greeneconomycoalition.org/news-and-resources/30x30-a-brave-new-dawn-or-a-failure-to-protect-people-and-nature

Fletcher, R. 2010. Neoliberal environmentality: Towards a poststructuralist political ecology of the conservation debate. Conservation and Society 8(3): 171–81, https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.73806

Fletcher, R. 2017. Environmentality unbound: Multiple governmentalities in environmental politics. Geoforum 85: 311–15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.06.009

Foucault, M. 1991. Governmentality. In Burchell, G., Gordon, C. and Miller, P. (eds.) The Foucault Effect: Studies in Governmentality. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 87–104.

Foucault, M. 2008. The Birth of Biopolitics, M. Senellart, M., Ewald, F. and Fontana, A. (eds.) London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230594180

Hauptfleisch, M., Blaum, N., Liehr, S., Hering, R., Kraus, R., Tausendfruend, M., Cimenti, A., Lüdtke, D., Rauchecker, M. and Uiseb, K. 2024. Trends and barriers to wildlife-based options for sustainable management of savanna resources: The Namibian case. In von Maltitz, G.P., Midgley, G.F., Veitch, J., Brümmer, C., Rötter, R.P., Viehberg, F.A. and Veste, M. (eds.) Sustainability of Southern African Ecosystems Under Global Change. Berlin: Springer Nature, 499–525, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10948-5_18

Heydinger J. 2021. A more-than-human history of Apartheid technocratic planning in Etosha-Kaokoveld, Namibia, c.1960-1970s. South African Historical Journal 73: 64–94, https://doi.org/10.1080/02582473.2021.1909120

Heydinger, J. 2023. Community conservation and remote sensing of the desert-adapted lions in northwest Namibia. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 11: 1187711, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.1187711

Hoole, A. and Berkes, F. 2010. Breaking down fences: Recoupling social-ecological systems for biodiversity conservation in Namibia. Geoforum 41(2): 304–17, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2009.10.009

Ingold, T. 2011[2000]. The Perception of the Environment. Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003196662

Joubert, E. 1974. The development of wildlife utilization in South West Africa. Journal of the Southern African Wildlife Management Association 4(1): 35–42, https://journals.co.za/doi/pdf/10.10520/AJA03794369_3314

Kalvelage, L., Revilla Diaz, J. and Bollig, M. 2023. Valuing nature in global production networks: Hunting tourism and the weight of history in Zambezi, Namibia. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2023.2200468

Kimaro, M.E., Lendelvo, S. and Nakanyala, J. 2015. Determinants of tourists’ satisfaction in Etosha National Park, Namibia. Journal for Studies in Humanities & Social Sciences 1(2): 116–31, https://journals.unam.edu.na/index.php/JSHSS/article/view/1008

Koot, S. and Hitchcock, R.K. 2019. In the way: Perpetuating land dispossession of the Indigenous Haiǁom and the collective action lawsuit for Etosha National Park and Mangetti West, Namibia. Nomadic Peoples 33: 55–77, https://doi.org/10.3197/np.2019.230104

KREA 2008. Kunene Regional Ecological Assessment Prepared for the Kunene People’s Park Technical Committee. Round River Conservation Studies.

Lendelvo, S., Mechtilde, P. and Sullivan, S. 2020. A perfect storm? COVID-19 and community-based conservation in Namibia. Namibian Journal of Environment 4(B): 1–15, https://nje.org.na/index.php/nje/issue/view/4

Lendelvo, S. and Nakanyala, J. 2012. Socio-economic and Livelihood Strategies of the Ehirovipuka Conservancy, Namibia. Windhoek: MRC/UNAM Technical Report.

Lenggenhager, L., Akawa, M., Miescher, G., Nghitevelekwa, R., and Sinthumule, N.I. (eds.) 2023. The Lower !Garib – Orange River: Pasts and Presents of a Southern African Border Region. Bielefeld: Transcript, https://www.transcript-publishing.com/978-3-8376-6639-7/the-lower-garib-orange-river/

LLF, WWF, IRDNC 2024. Legacy Landscapes Fund confirms long-term funding of USD 1 million per year to Namibia’s North-west: The Skeleton Coast-Etosha conservation bridge. Press Release, https://wwfafrica.awsassets.panda.org/downloads/240117-skeleton-coast-etosha-conservation-bridge-ll---press-release---llf-final.pdf

Luke, T.W. 1999. Environmentality as green governmentality. In Darier, E. (ed.) Discourses of the Environment. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers, 121–51.

MEFT 2021. Management Plan for Skeleton Coast National Park 2021/2022-2030/2031. Windhoek: Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, https://www.meft.gov.na/national-parks/management-plan-2-skeleton-coast-national-park-/3276/

MET 2009. Tourism Scoping Report: Kunene Peoples Park. Windhoek: Ministry of Environment and Tourism.

Miescher, G. 2012. Namibia’s Red Line: The History of a Veterinary and Settlement Border. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/9781137118318

Miescher, G. and Henrichsen, D. (eds.) 2000. New Notes on Kaoko: The Northern Kunene Region (Namibia) in Texts and Photographs. Basel: Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Miescher, G., Lenggenhager, L and Ramutsindela, M. 2023. The lower !Garib / Orange River: A cross-border microregion. In Lenggenhager, L., Akawa, M., Miescher, G., Nghitevelekwa, R., and Sinthumule, N.I. (eds.) The Lower !Garib – Orange River: Pasts and Presents of a Southern African Border Region. Bielefeld: Transcript, 11–24, https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839466391-001

Moseley, C. (ed.) 2010. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger. Paris: UNESCO, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000187026

Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pellis, A., Duineveld, M. & Wagner, L.B. 2015. Conflicts forever. The path dependencies of tourism conflicts: The Case of Anabeb Conservancy, Namibia. In Johannesson, G.T., Ren, C. and van der Duim, R. (eds.) Tourism Encounters and Controversies. Ontological Politics of Tourism Development. London: Ashgate, 115–38.

Schnegg, M. 2007. Battling borderlands: Causes and consequences of an early German colonial war in Namibia. In Bollig, M., Bubenzer, O., Vogelsang, R. and Wotzka, H-P. (eds.) Aridity, Change and Conflict in Africa. Köln: Heinrich-Barth-Institut, 247–64.

Sullivan, S. 2002. How sustainable is the communalising discourse of ‘new’ conservation? The masking of difference, inequality and aspiration in the fledgling ‘conservancies’ of Namibia. In Chatty, D. & Colchester, M. (eds.) Conservation and Mobile Indigenous People: Displacement, Forced Settlement and Sustainable Development. Oxford: Berghahn Press, 158–87, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781782381853-013

Sullivan, S. 2003. Protest, conflict and litigation: Dissent or libel in resistance to a conservancy in north-west Namibia. In Berglund, E. and Anderson, D. (eds.) Ethnographies of Conservation: Environmentalism and the Distribution of Privilege. Oxford: Berghahn Press, 69–86, https://doi.org/10.1515/9780857456748-008

Sullivan, S. 2006. The elephant in the room? Problematizing ‘new’ (neoliberal) biodiversity conservation. Forum for Development Studies 33(1): 105–35, https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2006.9666337

Sullivan, S. 2017. What’s ontology got to do with it? On nature and knowledge in a political ecology of ‘the green economy’. Journal of Political Ecology 24(1): 217–42, https://doi.org/10.2458/v24i1.20802

Sullivan, S., !Uriǂkhob, S., Kötting, B., Muntifering, J. and Brett, R. 2021. Historicising black rhino in Namibia: Colonial-era hunting, conservation custodianship, and plural values. Future Pasts Working Paper Series 13 https://www.futurepasts.net/fpwp13-sullivan-urikhob-kotting-muntifering-brett-2021

Sullivan, S. and Ganuses, W.S. 2021. Densities of meaning in west Namibian landscapes: Genealogies, ancestral agencies, and healing. In Dieckmann, U. (ed.) Mapping the Unmappable? Cartographic Explorations with Indigenous Peoples in Africa. Bielefeld: Transcript, 139–90, https://www.transcript-open.de/doi/10.14361/9783839452417-006

Sullivan, S. and Ganuses, W.S. 2022. !Nara harvesters of the northern Namib: A cultural history through three photographed encounters. Journal of the Namibian Scientific Society 69: 115–39.

Sullivan, S. Hannis, M., Impey, A., Low, C. and Rohde, R.F. 2016. Future pasts? Sustainabilities in west Namibia – a conceptual framework for research. Future Pasts Working Paper Series 1, https://www.futurepasts.net/fpwp1-sullivan-et-al-2016

Suzman, J. 2004. Etosha dreams: An historical account of the Haiǁom predicament. Journal of Modern African Studies 42: 221–38, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022278X04000102

Táíwò, O. 2023. It never existed. Aeon. 2023, https://aeon.co/essays/the-idea-of-pre-colonial-africa-is-vacuous-and-wrong

Tipping-Woods, D. 2023. Sharing space: Communities lead the way to a new era of landscape-scale conservation. World Wildlife Magazine Summer 2023, https://www.worldwildlife.org/magazine/issues/summer-2023/articles/sharing-space

Tsing, A.L. 2005. Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connection. Princeton: Princeton University Press, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400830596

Wilson, E.O. 2016. Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. New York: Liveright.

WWF 2018. Living Planet Report. Gland, Switzerland: World Wide Fund for Nature, https://www.wwf.org.uk/updates/living-planet-report-2018

2 Full workshop programme online here: https://www.etosha-kunene-histories.net/post/workshop-programme-with-abstracts

3 Different perspectives exist on whether or not the term Indigenous should be capitalised. Here we follow arguments for its capitalisation in order to emphasise that the term ‘articulates and identifies a group of political and historical communities’ with shared experiences of colonialism and displacement: as expressed, for example, by Sapiens—an anthropology magazine of the Wenner-Gren Foundation and the University of Chicago Press (https://www.sapiens.org/language/capitalize-indigenous/). We also respect the choice of some authors to depart from this convention.

4 Miescher et al. (2023: 22)

5 Sullivan et al. (2016: 10)

6 See, for example, Miescher & Henrichsen (2000) and Lenggenhager et al. (2023)

7 Moseley (2010), WWF (2018)

9 de la Bat (1982), Berry (1997)

10 Sullivan (2002), Lendelvo & Nakanyala (2013), Hauptfleisch et al. (2024)

11 KREA (2008), MET (2009)

12 Denker (2022), Tipping-Woods (2023)

13 LLF, WWF, IRDNC (2024)

16 Wilson (2016)

17 For different perspectives on ‘30x30’ see https://www.campaignfornature.org/news/category/30x30 and Eisen & Mudodosi (2021).

18 Dieckmann (2011), Koot & Hitchcock (2019)

19 Kalvelage et al. (2023)

20 These historical chapters draw closely on an iteratively updated chronology online at https://www.etosha-kunene-histories.net/wp1-historicising-etosha-kunene

21 We do not intend to obscure the complexity of African experience, histories and contexts by using this term to denote the period prior to formal German colonial annexation of the territory, although we are aware that its use is controversial (Táíwò 2023).

22 Schnegg (2007)

23 Miescher (2012)

24 Joubert (1974), Botha (2005)

25 Heydinger (2021)

26 Sullivan (2002), Kimaro et al. (2015)

27 KREA (2008), MET (2009)

28 See https://www.irdnc.org.na/women-for-conservation.html; https://www.irdnc.org.na/seen-on-the-banks-of-the-Hoanib-River.html; https://twitter.com/kensingtonroyal/status/1044861632436994048

29 Dieckmann (2003, 2007)

30 Koot & Hitchcock (2019), Dieckmann (2020)

31 Foucault (1991)

32 Luke (1999), Fletcher (2010, 2017)

33 Sullivan (2006)

34 Tsing (2005)

35 Bayart (2009)

36 Sullivan (2017), Dieckmann (2021a, b), Sullivan & Ganuses (2021)

37 Foucault (2008)

38 Ostrom (1990)

39 Also see Sullivan (2003), Pellis et al. (2015)

40 Bollig (2020: 162–70)

41 Sullivan & Ganuses (2022)

42 MEFT (2021)

43 Sullivan et al. (2021)

44 Hoole & Berkes (2010)

45 Suzman (2004: 223)

46 E.g. Ingold (2011[2000])

48 Also Heydinger (2023)

49 For example, Heydinger (2021)

50 Lendelvo et al. (2020)