18. Music and Spirituality in Communal Song: Methodists and Welsh Sporting Crowds

©2024 Martin V. Clarke, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0403.18

Two vignettes highlight the connections between music and spirituality that this chapter seeks to explore. The first is an account of a Methodist meeting in 1829, recorded in a letter from Benjamin Bangham to Mary Tooth:

The Meeting was very eminently crowned with the Divine presence, we had fellowship with him, and with each other; so that in the concluding part of the Meeting we were constrain’d to sing: -

‘And if our fellowship below,

What height of rapture shall we know,

When round his throne we meet?’1

The second concerns the departure of the Welsh men’s football (soccer) team from the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, recounted on Twitter by journalist Peter Gillibrand:

Welsh fans belting out Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau in front of the Welsh team clapping them is the spirit of Wales.2

Though separated by nearly two hundred years and taking place in markedly different cultural contexts, these brief examples have a common focus on how the communal singing of untrained groups of people expresses their commitment not only to one another but also to something intangible and greater than themselves.

Both Methodists and Welsh sporting crowds have long had reputations for their vigorous and passionate singing. Since its eighteenth-century beginnings, Methodism has sought to employ congregational singing as a tool for theological communication and as a means of encouraging participation and belonging.3 The Welsh crowd’s reputation for singing is one manifestation of a broader ascription of musicality to the people of Wales that became especially prominent from the latter half of the nineteenth century. The powerful singing of massed voices has been a central trope in this association, and the particular link with sport has been firmly made since at least 1905, when the singing of the players and supporters was widely reported in the press after Wales’s victory in rugby union against the touring New Zealand All Blacks.4

For both Methodists and Welsh people, the association with musicality, principally manifested in song, has been a marker of self-identity.5 The opening words of the preface to The Methodist Hymn Book (1933) evocatively capture the centrality of hymn-singing in Methodist spirituality: ‘Methodism was born in song’.6 Two appellations are frequently used with reference to Welsh musicality. The first, describing Wales as the ‘land of song’, can be traced to the triumph of the South Wales Choral Union in a contest at the National Music Meeting held at London’s Crystal Palace in 1872. The equivalent Welsh language phrase ‘Gwlad y Gân’ was used in a newspaper report of the event, from where its use seems to have burgeoned.7 The other widely used description of Wales as a ‘musical nation’ is a partial quotation from Dylan Thomas’s radio play Under Milk Wood, where its use is partly satirical.8 The notion that singing is a central pillar of both Methodist and Welsh identity is to some extent self-perpetuating; the idea is inculcated through communal activity and thus rehearsed and repeated over generations, albeit with changing emphases and within differing contexts.

Popular accounts of both Methodist and Welsh singing frequently attest to a link between musicality and spirituality. The popularity of Welsh folk singer Dafydd Iwan’s song ‘Yma o Hyd’ with the Welsh men’s football team in the FIFA World Cup 2022 is but the latest manifestation of a long-standing trend. Following the team’s qualification for the tournament, BBC journalist Nicola Bryan explored how ‘the song has cemented its place in the nation’s heart’ and its omnipresence during the team’s participation in the tournament was widely reported, alongside the intense singing of the national anthem.9 The Methodist Church of Great Britain itself highlights the historic and continued importance of singing in Methodism, noting on its website in a section on Methodist distinctiveness that ‘Methodists are well known as enthusiastic singers, in choirs and congregations. Singing is still an important means of learning about, sharing and celebrating our faith’.10 Historical accounts of Methodism abound with reports of the spirituality brought about through song. W. M. Patterson’s summary of an event celebrating the centenary of Primitive Methodism, one historic branch of the movement, serves as an example:

A great united choir filled the orchestra stalls; ‘but in point of fact’, remarked a journal in surprise, ‘the entire gathering was one gigantic choir. Not a single one in the multitude but could sing, and did sing. The hymns chosen needed no restraint on the part of the singers, no delicate tone painting; they were the old, full-bodied psalms of praises, resonant and triumphant. So this magnificent gathering threw restraint to the winds, and the deep swell of the great organ led them in such paeans of praise as it refreshed one to hear’.11

This chapter contends that these examples and the musical cultures and practices to which they relate highlight the importance and value of studying the ways in which relationships between music and spirituality have been and are articulated in the communal musical practices of groups that gather not primarily for musical purposes, but for whom musical participation functions as a key element in expressing personal affiliation and in bonding the community. It examines the sources and methods that underpin and enable such study and reflects on theoretical frameworks that can assist in the work of interpreting the significance of such musical practices. It seeks to emphasise the interrelation of words, music, and participatory performance cultures in understanding the high value accorded to music within the communities examined.

I. Lyrics

The textual content of the repertoires that have historically been widely sung in Methodist chapels and on the terraces of Welsh rugby and football stadia provide important insights that help to explain both the popularity of specific songs and, more generally, the practice of communal singing.

Charles Wesley’s name and lyrical output loom large in any discussion of Methodist hymnody. He has been the most represented author in every authorised hymnal in British Methodist history, although the actual number of his hymns included has declined steadily and significantly since the late-eighteenth century.12 A selection of Wesley’s hymns nonetheless retains considerable popularity within British Methodism, but compared even to the total of seventy-nine of his texts in the denomination’s current authorised hymnal, Singing the Faith (2011), this is only a small subset. Some of these have also long been widely used ecumenically, such as ‘Love Divine, All Loves Excelling’, ‘Hark! The Herald Angels Sing’ and ‘O Thou Who Camest from Above’. Others, such as ‘And Can It Be that I Should Gain’, while found in some hymnals beyond Methodism, carry a stronger denominational association. These hymns, and several others by Wesley that remain popular, share textual traits, but also strong associations with specific tunes, which are key to their endurance and appeal, as considered below.

Thematically, this small subset of Wesley’s hymns is diverse: the examples cited above respectively cover the nature of God’s love, the incarnation, the Holy Spirit, and the salvific work of Jesus Christ. There are, however, common textual features among many of them, relating variously to theological emphasis, poetic structure, and phraseology. Wesley’s characteristic emphasis on personal salvation is typically to the fore, through which his evangelical Arminianism tends to be cogently expressed. In some cases, this is primarily addressed by stressing the universal offer of God’s grace through the birth, life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. This interpretation of the incarnation is, unsurprisingly, found in ‘Hark! The Herald Angels Sing’, in lines such as ‘God and sinners reconciled’ and ‘born to raise the sons of earth, / born to give them second birth’, and through the characteristic use of ‘all’ (‘Joyful, all ye nations rise’; ‘Light and life to all he brings’).13 Elsewhere, the emphasis is more directly personal, such as in ‘And can it be that I should gain…’, where the first-person singular is consistently used. The relationship between the individual and the whole of humankind is expressly articulated in the third stanza: ‘emptied himself of all but love, / and bled for Adam’s helpless race. ’Tis mercy all, immense and free; / for, O my God, it found out me!’14

In terms of poetic structure, many of Wesley’s hymns that have attained the greatest popularity employ lengthy metrical patterns, often with six- or eight-line stanzas, such as 8787D (‘Love Divine, All Loves Excelling’) and 888888 (‘And Can It Be’). While Wesley also makes extensive use of more concise metres such as common metre and long metre, it is notable that some of his most enduring texts in these metres have, at least in Methodism, typically been associated with tunes that extend them through the repetition of one or more lines, such as ‘O for a Thousand Tongues to Sing’ (common metre) and ‘Jesus—the Name High over All’ (common metre). As a long metre text, ‘O Thou, Who Camest from Above’ stands as something of an exception in both regards, as neither of the tunes associated with it within and beyond Methodism extend the basic metrical pattern. Wesley used these longer forms to considerable effect, often building to a powerful climax in the final couplet of each stanza. ‘And Can It Be’ is a fine example of this, enhanced by its ABABCC rhyme scheme; the penultimate line of each of the first four stanzas opens with a bold acclamation: ‘Amazing Love!’; ‘’Tis mercy all!’ (twice), and ‘my chains fell off’.15 ‘Hark! The Herald Angels Sing’ reuses the opening couplet as a refrain at the end of each stanza, while the final line of each of the three stanzas in the commonly accepted version of ‘Love Divine, All Loves Excelling’ directs the singer inexorably towards a spiritual climax: ‘enter every trembling heart’; ‘glory in thy perfect love’; and, finally, ‘lost in wonder, love, and praise!’16

These features highlight Wesley’s poetical skill, while the latter also shows his rhetorical command. Memorable words, phrases and couplets abound in these popular texts, such as the startlingly polysyllabic ‘inextinguishable’ amidst a stanza otherwise composed entirely of one- and two-syllable words in ‘O Thou Who Camest from Above’.17 Such poetical and theological features have long attracted the attention of hymnologists, theologians, and devotional writers within and beyond Methodism. J. R. Watson’s The English Hymn: A Critical and Historical Study contains a chapter on ‘John and Charles Wesley’ but also devotes a separate chapter to ‘Charles Wesley and His Art’.18 In the latter, Watson draws attention to Wesley’s biblical knowledge and interpretative skill, his wider field of reference, and his poetical facility and creativity, writing of his verse: ‘Its principal feature is the richness of reference, and the fullness of doctrine which is compacted into the stanzas, and that is made possible not only by the use of other writers, but also by the way in which their words and phrases are so skilfully used, either entire or in altered form’.19

A recent collection of essays entitled Amazing Love! How Can It Be: Studies on Hymns by Charles Wesley examines twelve of his texts.20 Though written by North American scholars, where the reception patterns of Wesley’s hymns have been somewhat different from Britain, seven of those covered are among the small group of Wesley’s texts that remain in widespread use in the United Kingdom. While the volume does include a separate chapter on music and an appendix containing a selection of tunes from eighteenth-century Methodist sources, the studies of the texts themselves confine their remarks to literary, theological, and doctrinal matters. Such textual study is illuminating; nonetheless, separating the literary from the musical limits the potential for insights into the spiritual significance of hymnody and into the popular acclaim of a subset of Charles Wesley’s vast corpus of hymns, as will be explored further below.

Lyrical structures and themes are similarly important considerations when examining the songs of the Welsh sporting crowd, while language is an additional factor. Their repertoire includes a mixture of religious hymns and secular songs, ranging from patriotic songs such as the national anthem, ‘Hen wlad fy nhadau,’ and ‘Men of Harlech’ to hit songs by popular Welsh musicians, such as Tom Jones’s ‘Delilah’ and Max Boyce’s ‘Hymns and Arias’, as well as the more recently popularised ‘Yma o Hyd’.21 The two most widely sung hymns are ‘Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah’, a translation of a Welsh-language hymn by the great Welsh Methodist hymn-writer William Williams, Pantycelyn, set to the tune CWM RHONDDA by John Hughes (1873–1932) and ‘Calon Lân’, by Daniel James, set to an eponymous tune by a different John Hughes (1872–1914).

The bilingual nature of the crowd’s repertoire is significant. Though such songs and many others besides are sung by the crowds at rugby union and football matches at club level throughout Wales, home international fixtures in both sports are customarily played at stadia in the capital city, Cardiff, in south-east Wales, a region in which the Welsh language is less widely spoken than in parts of north and west Wales. Though the crowd sing in both Welsh and English, many will not be conversant in Welsh and will not otherwise use the language regularly or routinely. The importance of being able to participate in Welsh-language songs, however, and most notably in the national anthem, is palpable in the intensity with which they are sung and attested to by supporters and journalists alike on social media and in many newspaper articles that comment on the phenomenon.22

The lyrics of the hymns sung by the crowd are, naturally, overtly religious, yet Wales, in keeping with the rest of the United Kingdom, has experienced significant declines in religious belief and participation in recent decades. That the hymns continue to be sung owes much to the prominence of Wales’s Protestant non-conformist heritage in the popular imagination. Chapels remain visibly prominent in many Welsh villages and towns, even if no longer used for their original purposes, and the cultural memory of the hymn-singing tradition they encouraged and supported persists and has been actively revitalised by the Welsh media and other organisations in the twenty-first century.23 Both the hymns mentioned exhibit some linguistic and structural similarities to the hymns of Charles Wesley discussed above. ‘Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah’, of which only the first stanza is commonly sung by the crowd, employs a metrical structure that, like Wesley’s six- and eight-line patterns, draws attention to an emphatic declaration in the final couplet: ‘Bread of heaven, bread of heaven, / feed me now and evermore’ (alternatively ‘’til I want no more’). Such is the power of that couplet that the hymn is widely known as ‘Bread of Heaven’, and those lines are heard more frequently than the whole stanza. The text’s yearning for spiritual food may be readily translated to the secular sporting context as supporters seek the nourishment of their team’s victory, but it is also indicative of a spiritualised national identity. ‘Calon Lân’, by contrast, is essentially a prayer for spiritual purity (the title translates as ‘a pure heart’). It is not until the third stanza that the directing of this prayer to God is made explicit, which may partly contribute to its secular appeal. Beyond this, though, the looser sense of it conveying something ‘of the heart’ is easily reconciled with national sporting pride. Pride in Wales’s musical heritage, in which religious song is a significant strand, and fervent support of the national team combine to considerable effect on such occasions, when national pride is naturally foremost in supporters’ minds.

Regarding Wales’s musical heritage as the primary factor rather than religion also helps makes sense of the easy interchange between sacred and secular texts. Indeed, this is a feature to which Welsh singer-songwriter Max Boyce draws attention in ‘Hymns and Arias’, a song that celebrates the tradition of the singing crowd: ‘We sang “Cwm Rhondda” and “Delilah”, / damn, they sounded both the same’.24 Like ‘Calon Lân’, ‘Hymns and Arias’ and ‘Delilah’ employ a verse and refrain structure, with the repeated words of the refrains assisting their familiarity. Like the Methodist hymns noted earlier, all the popular songs of the Welsh crowd rely on fixed combinations of words and music, as will be explored in the following section.

II. Music

As noted above, many of Charles Wesley’s texts that remain in widespread use have strong associations with particular tunes. For some, these musical associations are particular to British Methodism, for others they are shared ecumenically and internationally, though there are also some distinct differences, for example, between Methodism and other denominations in Britain, and between British Methodism and Methodism in the United States. Almost all are musical associations that became established after Charles Wesley’s death, and in some cases more than a century later.

Many of these tunes share musical features that have led them to be regarded as characteristically Methodist. They flourished in the early nineteenth century, were often composed by church musicians, and sometimes betray a lack of technical training on the composer’s part, particularly in their harmonic language. Prototypes had emerged in the late eighteenth century, the best known of which is HELMSLEY, composed by Martin Madan, set to Charles Wesley’s ‘Lo! He Comes with Clouds Descending’, which, alongside ‘Christ the Lord is Risen Today’ set to EASTER HYMN are the only Wesley texts still widely sung to tunes likely to have been known to the author himself. Nicholas Temperley labels this type of tune as ‘Old Methodist’; his technical description is worth citing at length:

The typical tune that emerged was melodious, even pretty, and in the major mode. It often had a second, equally tuneful subordinate part, moving mostly in parallel 3rds or 6ths, either of similar compass or in a treble-tenor relationship; the bass was inclined to be static. In other words, the texture was that of the ‘galant’ or early classic style, and for the most part the compositional rules of that style were well observed; but it long outlived the departure of galanterie in secular music. The melody was often ornate, with two or three notes to many of the syllables, and could easily take ornaments such as the turn, appoggiatura or trill. Uneven syllable lengths were normal, whether in triple time or by unequal division of common-time bars. Dynamic contrasts between phrases were sometimes a feature, probably implying sections for women alone …. Usually there would be repetition of some lines of the text, delaying or reconfirming a cadence or half-cadence. Sometimes fuging entries crept in, despite Wesley. But the most typical feature of all was the final cadence, of a very definite, foursquare kind, consisting of three chords: tonic 6-4, dominant 7th, tonic.25

Not all such tunes had their origins in Methodism but were often borrowed from other collections of hymn tunes. SAGINA for ‘And Can It Be’ is arguably the archetype, but several of the hymns mentioned earlier are associated with tunes of this type. Within British Methodism, ‘O for a Thousand Tongues to Sing’ is widely sung to two such tunes: Thomas Phillips’s LYDIA (first published 1844), and Thomas Jarman’s LYNGHAM (first published c. 1803). Both conform to most of the properties identified by Temperley; LYDIA is more heavily focused on a single melody line and repeats only the final line of the text, whereas LYNGHAM employs extensive textual repetition and clear separation of high and low voices in its elaborate setting of the final line of each stanza.

The musical qualities of these tunes need to be recognised as playing an important part in the overall spiritual impact of the hymns with which they were associated and, by extension, in the spiritual value Methodists placed on hymns and hymn-singing as a whole. Measured by conventional musical standards for evaluating common-practice era composition, they may easily seem unremarkable or unsophisticated, yet their efficacy lies in their immediacy and accessibility. These are tunes designed to be picked up quickly by untrained singers, and to create both an instant and lasting impression on them. Despite the tendency towards extension and repetition, they are fundamentally and necessarily concise. As a result, they deliver their musical climax swiftly and obviously.

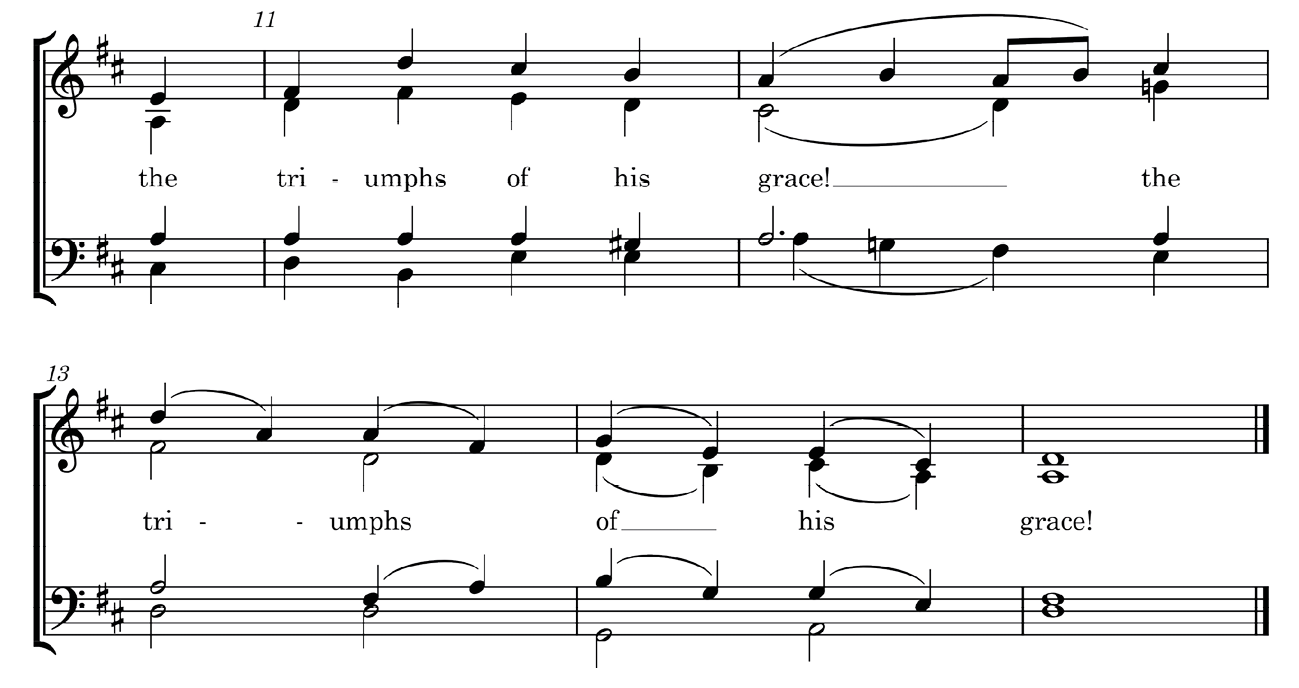

In LYDIA, the repetition of the final line of each stanza adds emphasis, underscored musically by the contrary motion of the ascending melody line and descending bass line to reach the tonic on the first strong beat of the final line, as shown in Figure 18.1.

Fig. 18.1 Thomas Phillips, LYDIA, bars 104–15. Transcription by author (2023), CC BY-NC 4.0

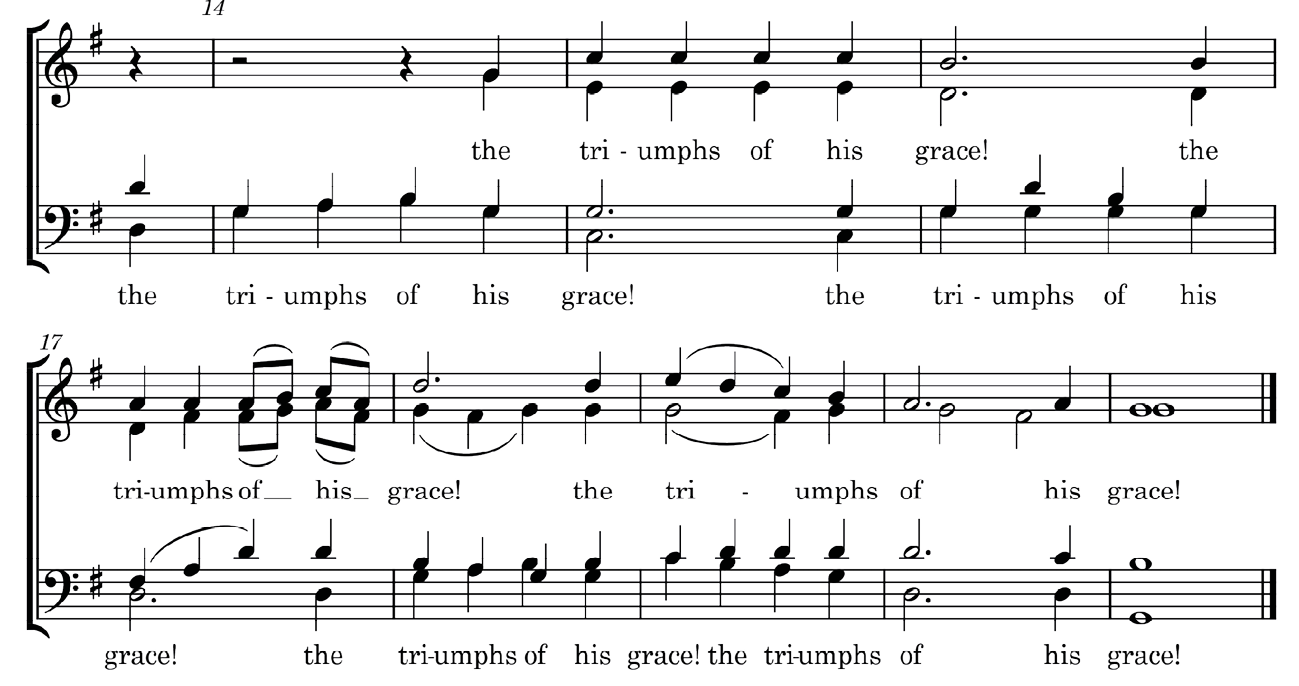

In LYNGHAM, Jarman uses a combination of melody, text setting, and texture to bring the tune to a rousing conclusion in his extended setting of the final line, shown in Figure 18.2. With each textual repetition, the melody moves one step higher until it reaches its highest pitch on the first strong beat of the final repetition, at which point the four voice parts revert to homophony after a fuging section. The final repetition of ‘triumphs’ is extended over a full four beats, adding a last flourish.

Fig. 18.2 Thomas Jarman, LYNGHAM, bars 134–21. Transcription by author (2023), CC BY-NC 4.0

These tunes were designed to be sung vigorously. They highlight the evangelistic impulse of Wesley’s text and accentuate the balance his words strive to achieve between personal piety and social holiness. They achieve their impact most readily when sung in large gatherings in which every individual participates in the singing.

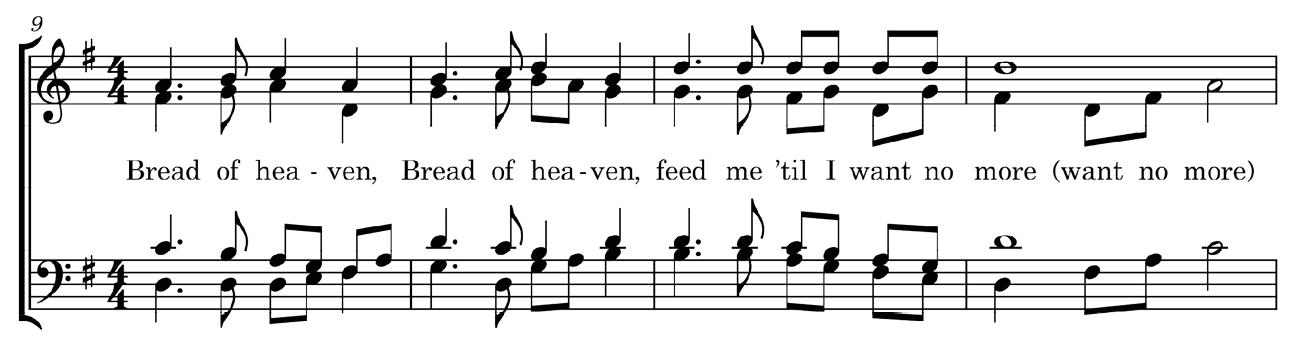

Similar musical characteristics and contexts can also be found in the repertoire of Welsh sporting crowds. The widespread use of ‘Bread of Heaven’ as an alternative title for ‘Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah’ (set to the tune CWM RHONDDA) attests to the importance of the musical properties of that hymn tune in ensuring its popularity. The rising melodic sequence as ‘Bread of heaven’, followed by the declamatory ‘Feed me ’til I want no more’ and its surging echo are musically memorable and, like the examples of LYDIA and LYNGHAM, build to an obvious climax.

Fig. 18.3 John Hughes, CWM RHONDDA, bars 9–12. Transcription by author (2023), CC BY-NC 4.0

The eponymous tune to ‘Calon Lân’ reaches its high point at the beginning of the refrain, as the title words are sung, underscoring their verbal significance. Both ‘Hymns and Arias’ and ‘Delilah’, meanwhile, have marked melodic contrasts between their verses and refrains. The verses are confined to a narrow range and use simple, almost speech-like rhythms, while the refrains employ a wider range and more distinctive rhythms, notably using longer notes to emphasise key lyrical features.

The performance of ‘Hen wlad fy nhadau’ at Welsh rugby and football internationals has undergone a significant shift in the twenty-first century that seems to have intensified the experience for those singing it. The anthem’s climax has traditionally been at its mid-point, with the words, ‘Gwlad! Gwald!’ (literally translated ‘country’, but understood as signifying Wales) that begin the refrain. Set to two long notes, first the dominant and then the upper tonic of the scale, it is a moment of textual and musical power that has few if any parallels in other national anthems. More recently, and seemingly following the lead of famous Welsh singers such as Bryn Terfel and Katherine Jenkins who have often been invited to lead the singing of the anthem at international matches, most of the final line of the refrain is customarily sung an octave higher than notated in the original melody. The words at this point, ‘O bydded i’r hen iaith barhau’ concern the ongoing preservation of the old language (‘hen iaith’, i.e., Welsh). The original melody has a descending contour to the final tonic, and while the now-customary modification disrupts the overall melodic balance of the anthem, its impact is undeniably significant, if unsubtle. Video footage of players and supporters confirm the near ubiquity of this modification; their strained facial expressions as they reach for the high notes symbolising their fervour and the intensity of the shared experience.

III. Context

The above analysis of popular Methodist hymns and songs of the Welsh sporting crowd indicates that textual and musical content are important factors in understanding the ways in which such repertoire is understood to enable or express spirituality, or to capture a perceived national spirit. Context, however, is also a vital element; the sharing of such experiences among people with common interests and commitments provides the environment in which the spiritual is perceived. Neither Methodist meetings nor sporting fixtures are primarily musical events or activities. While music has long played an important role in both, it does so in support of another purpose; it is not intended as an end in itself. This has implications for understanding music’s role in articulating or conveying spirituality. While music in these contexts is not necessarily spiritualised in its own right, it is integral to the spiritualisation of the wider event for many participants.

Timothy Dudley-Smith published his reflections on hymn-writing in a volume entitled A Functional Art. Dudley-Smith’s title, observations and arguments partly express this notion of hymns pointing beyond themselves. He defines the basic purpose of a hymn to be the praise of God, but also notes their benefit to the singers.26 Drawing on the work of Erik Routley, Dudley-Smith highlights three ways in which hymns bring benefits to those who sing them: doxological, doctrinal, and communal.27 Regarding the latter, he notes that ‘It is something we do together, and everyone knows that a shared task is one of the key elements of “team building”’.28 Throughout the volume, he makes frequent mention of Charles Wesley, and the human-focused aspects of hymn-singing he describes map clearly onto Methodist practice and repertoire. The singing of the Welsh sporting crowd is also obviously communal. While it is neither doxological nor doctrinal in the strictly religious sense that Dudley-Smith intends, there are nonetheless parallels. The act of singing, if not in praise of the team, serves both to celebrate it and encourage the players, while in different ways lyrics serve to express central tenets of national identity. In the case of ‘Hen wlad fy nhadau’, the lyrics directly refer to the nation, but in other Welsh language songs, such as ‘Calon Lân’, the language itself is the crucial factor, marking a distinctive cultural identity. As a renowned hymn-writer, Dudley-Smith’s primary interest is unsurprisingly in the words of hymns. His description of the benefits to participants as ‘side-effects’ reflects this priority.29 Contextual consideration of the spirituality of communal singing, however, places the emphasis on practice, in which the interaction of words and music is central. Indeed, if the songs of the congregation or the crowd are, in Dudley-Smith’s term, ‘functional’ in that they point beyond themselves in enabling a spiritual experience, then investigating and interpreting practice is vital.

In a specifically religious context, Jeff Astley’s concept of ‘ordinary theology’ offers a means of understanding the ways in which so-called ordinary believers, that is, those without formal theological training, learn and express their theology.30 It is a useful theoretical framework for interpreting the spiritual value congregation members find in hymnody, as it is rooted in religious practice. Among the characteristics of ordinary theology identified by Astley are that it is meaningful, religious, and kneeling, or celebratory.31 The opening vignette in this chapter highlights these in practice in a Methodist context: the sharing of a hymn helps make sense of the spiritual meaning of the meeting described, while the religious nature of the gathering is the spur for such reflection. The hymn also highlights how the belief is expressed in practice: it is manifested in the celebratory act of communal singing. In other ways, however, the singing of hymns departs from aspects of Astley’s framework, most notably his observation that ordinary theology is typically tentative, or cautiously expressed.32 The lyrics allow ideas to be expressed in words other than one’s own, while the act of singing together, particularly in the vigorous manner commonly associated with Methodists and encouraged by such tunes as those discussed above, project a confident spirituality.

Astley’s work is thoroughly contextual and points to the importance of understanding the relationship between practice and meaning. Though he focuses on theology, that is, people’s beliefs, the emphasis on practice means that spirituality is thoroughly intertwined. Belief expressed through or learned via practice has a symbiotic relationship with spirituality. Setting aside the explicitly Christian focus of Astley’s work, the concepts and characteristics he identifies have a wider applicability in relation to questions of belonging and identity. Rugby or football internationals are occasions on which national identity and pride are considerably heightened for supporters. Their commitment to team and nation, given voice through singing, is expressed in ways that stand apart from everyday life. If national identity takes on a spiritual element on such occasions, communal singing of meaningful repertoire serves as both an enabler and expression of that identity.

Another practice-focused framework for interpreting the spiritual significance accorded to communal singing traditions such as those discussed here can be found in Ruth Finnegan’s The Hidden Musicians: Music-Making in an English Town. Chiefly an ethnographic study of musical practices in 1980s Milton Keynes, Finnegan’s study concludes with an analysis of its implications for understanding the meanings people accord to music. She highlights the importance of shared interests in members’ sense of belonging to a musical group:

People commonly did not know much about all their co-members in musical groups—but in the sense that mattered to them they knew enough. Individuals often joined because they knew one or more members already and their joint musical activity then reinforced and amplified that existing contact, if not through practicalities like sharing lifts or delivering messages then at least through supporting the same group and making music together.33

This illustrates Finnegan’s argument that the meaningfulness of such activity, which could be very significant, emerged from engagement in shared practice with others about whom sufficient information was known in terms of this common interest. This has particular resonance with the sporting crowd, who gather solely for this purpose and whose collective voice is a temporary manifestation of what otherwise might be regarded as, in Benedict Anderson’s term, an imagined community.34 Making music together affirms a shared identity that becomes especially meaningful in that context. As Finnegan goes on to note, many of her research participants confirmed that ‘their music-making was one of the habitual routes by which they identified themselves as worthwhile members of society and which they regarded as of somehow deep-seated importance to them as human beings’.35 Observing that musical practices are bound up with other events, activities, and ideas. Finnegan found that, despite this, many participants accorded music a different value from those other activities:

What did seem unmistakable was an unspoken but shared assumption among the participants in local music that there was something sui generis, something unparalleled in quality and in kind about music which was not to be found in other activities of work or of play. This assessment was neither exactly measurable nor precisely definable, but was for all that itself part of the reality, one way in which music had indeed, as experienced by its local participants, its own inimitable meaning.36

As already noted, the musical practices considered in this chapter are intended to express meaning beyond themselves. However, in both cases, singing communally is one of the chief means by which the intense emotions or sense of spirituality associated with the occasion are created and perceived.

Finnegan and Astley both take seriously the lived experiences of those whom they variously term ‘ordinary believers’ and ‘hidden musicians’. This allows them to theorise the ways in which values and meanings are learned and attributed through activities that have too often been overlooked because of their supposed lack of intellectual sophistication or aesthetic quality. Meaning and value emerge through participation and shared identity. Such perspectives, coupled with close engagement with musical and textual sources, offer a means of making sense of the perceived spirituality engendered by shared musical practices in Methodism and in Welsh football and rugby stadia. Textual meaning, structure, language, and imagery play an important role, as do musical settings that balance a simple directness with dramatic memorability. Paired, they thrive in contexts in which perceptions of common belief, meaning, identity, or value are already heightened, often reinforcing among participants and observers a sense of massed communal singing as an enabler and expression of spirituality.

1 Letter from Benjamin Bangham in Coalbrookdale to Mary Tooth at Madeley, 20 August 1829, Manchester, Methodist Archive, Fletcher-Tooth Collection, GB 135 MAM/FL/1/2/3.

2 Peter Gillibrand (@GillibrandPeter), Twitter, 29 November 2022.

3 For a brief summary, see Erika K. R. Stalcup, ‘The Wesleys: John and Charles’, in Hymns and Hymnody: Historical and Theological Introductions, ed. by Mark A. Lamport, Benjamin K. Forrest, and Vernon M. Whaley, 3 vols (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2019), II, 210–25. For a more detailed account of the practice of hymnody throughout the history of British Methodism, see Martin V. Clarke, British Methodist Hymnody: Theology, Heritage, and Experience (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018).

4 See Helen Barlow and Martin V. Clarke, ‘Singing Welshness: Sport, Music and the Crowd’, in A History of Welsh Music, ed. by Trevor Herbert, Martin V. Clarke, and Helen Barlow (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2022), pp. 332–54.

5 Both areas of focus in this chapter are inevitably informed by my personal experiences and identity. I was born into an English-speaking family in South Wales and brought up in the Methodist Church. Although no longer residing in Wales, I remain an active member of the Methodist Church of Great Britain and served as the musical editor for its most recent authorised hymnal.

6 The Methodist Hymn Book (London: Methodist Conference Office, 1933), p. iii.

7 See Trevor Herbert, ‘Popular Nationalism: Griffith Rhys Jones (“Caradog”) and the Welsh Choral Tradition’, in Music and British Culture 1785–1914: Essays in Honour of Cyril Ehrlich, ed. by Christina Bashford and Leanne Langley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), pp. 255–74 (at 268-69).

8 See Helen Barlow, ‘“Praise the Lord! We are a Musical Nation”: The Welsh Working Classes and Religious Singing’, Nineteenth-Century Music Review 17 (2020), 445–72 (at 445–46).

9 Nicola Bryan, ‘World Cup 2022: Wales’ Qualification Revives Yma O Hyd Success’, BBC News, 11 June 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-61757909; Seren Morris, ‘Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau: What do the Welsh national anthem lyrics mean?’, Evening Standard, 28 November 2022, https://www.standard.co.uk/news/uk/hen-wlad-fy-nhadau-welsh-national-anthem-lyrics-meaning-football-world-cup-sport-wales-vs-england-b1043125.html

10 The Methodist Church, ‘Born in Song’, The Methodist Church https://www.methodist.org.uk/about-us/the-methodist-church/what-is-distinctive-about-methodism/born-in-song

11 W. M. Patterson, Northern Primitive Methodism: A Record of the Rise and Progress of the Circuits in the Old Sunderland District (London: E. Dalton, 1909), p. 8.

12 See Clarke, British Methodist Hymnody, pp. 190–95.

13 Hymns & Psalms (Peterborough: Methodist Publishing House, 1983), hymn 106.

14 Ibid., hymn 216.

15 Ibid., hymn 216. For an extended analysis of this text, see Martin V. Clarke, ‘“And Can It Be”: Analysing the Words, Music, and Contexts of an Iconic Methodist Hymn’, Yale Journal of Music & Religion 2 (2016), 25–52 (at 26-29).

16 Hymns & Psalms, hymn 267.

17 Ibid., hymn 745.

18 J. R. Watson, The English Hymn: A Critical and Historical Study (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), pp. 205–29, 230–64.

19 Ibid., p. 255. Similar emphases can be found in S. T. Kimbrough, Jr, The Lyrical Theology of Charles Wesley: A Reader (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2013) and numerous chapters in Kenneth G. C. Newport and Ted A. Campbell, eds, Charles Wesley: Life, Literature and Legacy (Peterborough: Epworth, 2007).

20 Chris Fenner and Brian G. Najapfour, eds, Amazing Love! How Can It Be: Studies on Hymns by Charles Wesley (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2020).

21 The Welsh Rugby Union’s decision to prohibit choirs booked to provide musical entertainment for the crowd from including ‘Delilah’ in their sets early in 2023 attracted considerable media attention and debate. See Andy Martin, ‘Bye, Bye, Bye Delilah: Wales Rugby Choirs Banned from Singing Tom Jones Hit’, Guardian, 1 February 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2023/feb/01/delilah-welsh-rugby-union-choirs-banned-from-singing-tom-jones-hit

22 A plethora of such articles appeared in November 2022 as the Welsh men’s football team competed in the FIFA World Cup finals for the first time since 1958. Examples include Ian Mitchelmore, ‘The Amazing Rendition of the Anthem Wales Fans Have Been Waiting to Sing for 64 Years’, Wales Online, 21 November 2022, https://www.walesonline.co.uk/sport/football/football-news/amazing-rendition-anthem-wales-fans-25571439

23 On the role of BBC Wales, the Football Association of Wales, and the Welsh Rugby Union, see Barlow and Clarke, ‘Singing Welshness’. The inclusion of hymns in the repertoire performed by a new generation of Welsh solo artists and ensembles, such as Katherine Jenkins and Only Men Aloud, are further examples.

24 Max Boyce, Hymns & Arias: The Selected Poems, Songs and Stories (Cardigan: Parthian Books, 2021), p. 3. The song also refers by name to ‘Calon Lân’ and several other Welsh songs. An adaptation of this song sung at the opening ceremony of the Rugby World Cup in Wales referenced the interweaving of religion and sport explicitly. Referring to the Millennium Stadium’s sliding roof, Boyce sang ‘They’ll slide it back when Wales attack / so God can watch us play’. Max Boyce, ‘Rugby World Cup 1999, Max Boyce, Hymns and Arias, Opening Ceremony’, online video recording, YouTube, 26 June 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O-EKY7z_jeE

25 Nicholas Temperley and Martin V. Clarke, ‘‘Methodist Church Music’, in Grove Music Online, rev. Martin V. Clarke (2001), https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.47533

26 Timothy Dudley-Smith, A Functional Art: Reflections of a Hymn Writer (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 1–3.

27 Ibid., p. 3.

28 Ibid., p. 5.

29 Ibid.

30 Jeff Astley, Ordinary Theology: Looking, Listening and Learning in Theology (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002).

31 Astley, Ordinary Theology, pp. 68–76.

32 Ibid., pp. 61–62.

33 Ruth H. Finnegan, The Hidden Musicians: Music-Making in an English Town (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1989; repr. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2007), p. 303.

34 Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (London: Verso, 1983, revised and extended, 1991).

35 Finnegan, Hidden Musicians, p. 306

36 Ibid., p. 332.