6. Dissonant Spirituality:

A Hermeneutical Aesthetics of Outlaw Country

©2024 C.M. Howell, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0403.06

While, given the multiplication of uses of the term ‘spiritual’, no general definition can be determined, hermeneutical aesthetics offers a constructive framework to interrogate its meaning. Although this methodological framework emphasises a concrete set of particulars as the basis for its claims, it does so without being reduced to empirical data, allowing immaterial aspects to stand on an equal footing with any of their material (or even quantifiable) counterparts. Art is an event. It gathers a context, a meaningful world. It shifts being. As such, all relevant dimensions for the question at hand are drawn into view, including the psychological (i.e., the so-called ‘subjective’ dimension),1 but also the tangible aspects of the aesthetic phenomena, as well as an underlying ontological dimension. The ‘meaning’ of spirituality happens in the relationships between these dimensions, as they appear all at once, and never alone. The first part of this chapter outlines a theoretical account of aesthetic cognition through some key thinkers of the tradition, and a corresponding account of contemporary spirituality through the work of Charles Taylor. The second part employs this method by tracing the meaning of spiritual in the tradition of American music known as outlaw country. The genre was founded during the 1970s as well-established musicians in country music—Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, Kris Kristofferson to name a few—sought a freedom for the craft from the overly mechanised production of the Nashville sound. The term ‘outlaw’ was affixed to the style by the promoter Hazel Smith, who intended the meaning ‘living on the outside of the written law’.2 It is expressive of a disposition that is a step removed from outright transgression, but equally discontent with standing norms. The founding of outlaw country came at the tail end of the spiritual revolution in the late-1960s, which served as an impetus for the artists’ newly claimed freedom. While allusions and explicit references to God and religion are longstanding features of country music, outlaw country presents these concerns through a hermeneutic of the advancements of spirituality. The meaning of spirituality presented is not quite a rejection of traditional religion, standing just at its boundary. Combined with its popularity—producing country music’s first platinum record—this makes the genre a formative site for the meaning of spirituality in American culture.3

I. Music, Meaning, and Spirituality

It is often noted that ‘spirituality’ is inherently vague.4 The term can indicate a transcendent realm that stands apart from, but is simultaneously tethered to, the material world of sensual perception.5 It can reference a kind of existential orientation that occurs through a process of seeking outside the bounds of traditional religion.6 Even within the solid boundaries of Christian discourse, spirituality can speak to a personal, inner life distinguished from public forms of religious expression.7 Or, it can refer to a form of mystical thought that lives beyond rationally determined limits.8 These meanings are typically overlaid upon a network of innately dialectical categories—such as immanence/transcendence, sacred/secular, inner/outer, active/passive, etc.—which, while invoked to clarify matters, ultimately result in confounding an already complex semantic range. Despite this ambiguity, there is an ever-increasing use of the term spirituality. Indeed, the term’s ambiguity, rather than being perceived as a deficiency, appears to be part of its strength and appeal. Its ambiguity allows the concept to be employed in a variety of ways. The indefinite openness of ‘spirituality’ is the stability of its hermeneutical horizon. This implies that the meaning of spirituality is always involved in a process of interrogation. Its meaning happens in certain moments, as a dialectical reflexivity is negotiated. On the one hand, this claim coincides with uses of spirituality which speak to some ethical or dispositional formation.9 On the other, this openness places the meaning of spirituality beyond the sure footing of scientific inquiry. In fact, it arguably pushes the inquiry into the domain of aesthetics.

The mode of thought that corresponds to the value of the aesthetic sphere is often termed ‘symbolic’, which indicates both a similarity and dissimilarity to rational cognition. Symbolic thought is not, however, irrational. It merely operates by analogy rather than propositional predication. It is akin to contemplation, which has been held at various points in the Western tradition as a higher form of thought than reason. Given the reflexive nature of spirituality, the element of difference in analogy—or, in musical terms, the dissonance within harmony—is a vital feature of its realisation. Dissonance, indeed, will be a controlling metaphor in what follows, even if the term occasions a ‘certain odor of sinfulness’.10 It is meant here in the somewhat traditional sense of a tension within the harmonious relationships of music, resonating with the ambiguity of the meaning of spirituality.11 Unlike its modern usage, such as in Arnold Schoenberg’s atonal ‘emancipation of dissonance’, classical dissonance works in complementing consonance in a certain way.12 Dissonance, more pointedly, ‘names the palpable presence of an enduring difference’.13 Its effect is not chaos or ugliness, but rather ‘extra audible information in the form of “beats” or “roughness”, a richer, grainier, less-polished sound’.14 In fact, by assuming its place alongside consonance, it leads to an ‘enhancement of the audible’, forcing attention to the aesthetic presence of music.15 The disruption of consonance causes the listener to lean in, to focus, to concentrate. It produces an awareness of the tacit activities already in play in the listening experience. Dissonance reveals music.

(a) Post-Metaphysic Aesthetics and Cognition

Hermeneutical aesthetics develop from a tradition that held music in a negative light precisely because it apparently circumvents reason and stirs the emotions. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, for example, stated that although ‘music charms us’ through the tacit tracking of ‘harmonies of numbers and in the counting … of the beats or vibrations of sounding bodies’ it remains, essentially, a confused form of cognition.16 In Immanuel Kant, music is a subordinate form among the arts, evoking a degraded sense of mental pleasure in place of the harmonious mental activity spurred by beauty.17 Even in thinkers who give a much more positive cognitive function to music, such as Arthur Schopenhauer, poetry retains a high place in the arts due to its rational-linguistic structure.18

As ontology (the study of being) began to overtake epistemology (the study of knowledge) in the tradition, the relationship between reason and the arts also shifted.19 Rather than being relegated to a domain beyond reason, aesthetics and hermeneutics became the basis for thought in general. In some sense, the broadening of the influence of music is congruent with the earlier rationalist accounts. The arts penetrate the spirit of humanity, evoking emotions alongside reason. The difference is that for later thinkers this formative effect does not lead to deficient modes of cognition, but to a reconnection to the fullness of reality. Thought is now considered as an occurrence within the dynamic correspondence of a meaningful world. Aesthetic events establish this meaning by gathering various aspects of life-contexts—writer, performer, audience, instruments, speech, sound, other contextual features, etc.—into a single place.20 They create a harmonious whole in their sheer existence.

One of the more distinguishing characteristics of hermeneutical aesthetics is that the creative essence of art is not reduced to artistic expression.21 As Martin Heidegger points out, the ‘work’ of art gives an identity to the artist as much as the artist is the ‘origin of the work’.22 The artwork does not spontaneously appear, of course, but it is removed from the causal connection between human production and the force of its gathering. Art is always out ahead of the artist, often leading their creative insights and technical abilities to new possibilities. Art happens in the work of art as an ontological dimension is realised through the harmonious whole. Events create an intelligible context. To develop this standpoint, a broader meaning of λόγος is retrieved. Heidegger thus sees hermeneutics as a mediating realm between the coming to presence and apprehension of phenomena, the latter of which are particular instances in and through which being is revealed.23 Paul Tillich revives λόγος in his concept of ‘ontological reason’, or ‘the structure of the mind which enables it to grasp and shape reality’.24

Debates do continue, however, about the relationship between language and music, primarily concerning the degree of intelligibility within hermeneutics. What is typically agreed upon is that music exerts a positive influence on aesthetic intelligibility through its symbolic nature. Aesthetic presences (as well as phenomena in general) are not understood as beings with a definite and constant substance which thought penetrates through analysis and grasps through conceptual apprehension. In this post-metaphysical landscape, being (Sein) is relational, that is, all beings (Seiendes) are constituted through a referential network. In inquiring into the intelligibility of music, its symbolic nature is not a deviation from this basic framework. In fact, aesthetic presences are symbolic in that they make the relationality of being more obvious. They are, in a sense, truer to reality by their symbolic nature.25

Hans-Georg Gadamer explains the symbolic nature of aesthetic presences as an ‘intricate interplay of showing and concealing’.26 The essence of a symbol is an active negation. It ontologically participates in the reality toward which it points, revealing a hiddenness within its own presence. In doing so, symbols force a reflection on the relationality of being. A symbol is thereby not a poor ‘substitute for the real existence of something’, but a revealing of the reality of all things.27 For the question of aesthetic cognition, Gadamer explains, ‘there is more to the work of art than a meaning that is experienced only in an indeterminate way’.28 That is, its meaningful contents are not ‘traces of conceptual meaning’.29 Symbols make meaning by their presence, doing so in manifesting a dynamic inner-relation.

Music accomplishes this in both its non-representative form, which is an even more radical feature of its being than with non-objective art, as well as in its re-presentation of relationality. As concerns the specific musical examples of outlaw country discussed below, the appearance of spirituality cannot be elucidated apart from the music itself. This is perhaps most explicit in Nelson’s 1996 instrumental track title ‘Spirit of E9’, from the record Spirit. But even the examples below are events in which spirituality is taking form, becoming realised, rather than examples of an already established sense of the category. These songs add a dimension to the essence of spirituality that cannot be justified on rational terms.

On the one hand, their unique ability to present the self-negating activity of being ‘calls on us to dwell upon [the artwork] and give our assent in an act of recognition’.30 Symbols draw us in, offering the possibility of cognition by demanding the activity of interpretation. On the other hand, Gadamer is clear that the re-cognition here does not indicate a ‘simple transference of mediation of meaning’ which is elsewhere grounded in rational concepts.31 The cognitive aspect of symbols is their freedom from reason. It, in fact, reminds reason of its limits. Symbols make meaning by inviting participation, all but compelling thought to search for a resolution from their inherent tension; concepts, in contrast, are meaningful in their precision and usefulness.32

The relationship of symbols to rational concepts reveals that meaning (and its cognition) stems from a more fundamental dimension of reality than what can be captured by reason. Tillich speaks of this as a ‘Spiritual Presence’ of the ontological structuring of love, which both produces and sustains ultimate meaning within being.33 The meaning music gives to spirituality cannot be understood in this framework as music ‘explaining’ spirituality. Meaning, here, indicates something other than information. It is the gathering required for conceptual analysis.

(b) The Indeterminate Dimensions of a Secularised Spirituality

It is in this vein that Charles Taylor describes spirituality as an experience with ‘fullness’ that evokes a sense of enduring strength through bringing various features of existence into a harmonious order.34 Taylor analyses the historical conditions of such an encounter with fullness in light of modern secularity,35 devising the concept of an ‘immanent frame’ to explicate the conditions of belief unique to contemporary society.36 For Taylor, this ‘immanent frame’ is generally shared by the inhabitants of Western culture, it forms a starting point for all spiritual experiences (akin to the role of experience and tradition mentioned above), and it is nonetheless constituted by a set of features that were historically understood as pitted against transcendence. Among these features is an axiomatic valuing of ‘instrumental reasoning’, or a mode of understanding which sees the meaning of things only in terms of causality or moral formation.37 Taylor argues that this feature is naively presupposed in two broad kinds of reactions to the conditions of modern secularity, which he refers to as the ‘spins’ of ‘open’ and ‘closed’ postures. An ‘open’ posture posits an immediate access to some other realm of existence, invoking a view from nowhere often retrieved from a classical tradition, albeit employed in a new way against the immanent frame. A ‘closed’ posture inhabits the immanent frame fully, particularly its character of providing an ‘order which can be understood in its own terms, without reference to the “supernatural” or “transcendent”’.38 And yet it tenuously retains the language of spirituality (along with related terms), its meaning radically oriented to socio-cultural conditions; in the ‘closed’ posture, there can still be experiences of fullness, but their interpretation and explanation happen without reference to a transcendent realm.

Both the ‘open’ and ‘closed’ postures are ‘spins’ in the sense that they are influential narratives through which ‘one’s thinking is clouded or cramped by a powerful picture which prevents one seeing important aspects of reality’.39 That is, they confuse the justifications for their own position without taking into account the experiences which led to the establishing and/or adopting of such a position. Neither spin is entirely persuasive. As Taylor notes, both require an element of ‘anticipatory confidence’, or a ‘leap of faith’, which catapults meaning into the search for rational justification.40 This ‘anticipatory confidence’ speaks to the kind of aesthetic meaning explicated above. Neither the ‘open’ nor the ‘closed’ spins are typically in full effect, moreover. Most people live in the ‘cross-pressure’ developed between their pulls.41 This is a frame of experience circumscribed by tension, the competing claims of spirituality, and its various dialectical categories: materialism, traditional religion, extra-rational meaning, corporate sense of identity, secularity, etc. To return to Taylor’s notion of spirituality, aesthetic events (including music) participate in the development of new forms of identity that stem from this tension, a process he terms the ‘nova effect’ of modern spirituality.42

Two points should be highlighted before moving to a concrete example of this situation. First, music developed in this context establishes new forms of spirituality. These new forms draw in various ways from the dialectical relationships inherent to the term spirituality, opening a range of new spiritual positions. Astrology and new religious movements (NRMs) are good examples of this sort of spirituality, as well as more recent developments in which hallucinogenic experiences play a formative role. Equally, however, spirituality can embrace more traditional forms of religion, which are themselves reinterpreted through materialism or any of the other dimensions mentioned here. The ‘Nones’ of post-confessional religion are a paradigm case.43 Aesthetic moments do not impart their constitutive force by declaring one or the other ‘spins’ in an unambiguous manner. They allow the tension of spirituality to appear.

II. A Mythological Spirituality in Outlaw Country

Turning to specific forms of aesthetic symbols, the meaning of spirituality is established in particular musical events. Specific songs form the material basis for experiences with fullness as defined by Taylor. Here, attention is given to the articulation of the topic at various points within the single musical tradition of ‘outlaw country’: Willie Nelson (b. 1933), Sturgill Simpson (b. 1978), and Cody Jinks (b. 1980), approaching each through discussion of one exemplary song: ‘Hands on the Wheel’, ‘Turtles All the Way Down’, and ‘Holy Water’ respectively. Key here is musical dissonance, which has a particular impact on the presence of their symbolic meaning.

(a) Symbolic Meaning and the Dissonance of the Third

The symbolic meaning of music reduces the tendency to frame musical hermeneutics in terms of an opposition between language and ‘absolute’ music.44 Poetic modes of language are just as cognitively symbolic as musical forms, giving only the illusion of something more stable. For both, meaning is rooted primarily in the happenings of aesthetic events, and only develops into more stable cultural-traditional forms through hermeneutical reflection. The dissonant moments of music can be the very impetus for the event, directing attention towards the accompanying lyrics. On a general level, we take notice of lyrics, and analyse their meaning, because of their appearance in the song as a whole. They are ‘lyrics’ because they are accompanied by music. At a more detailed level, specific moments within a song heighten its hermeneutical effect. As a deviation from composition norms takes place, as our attention is caught, meaning has already happened. Here, dissonance receives a technical meaning. Even when understood as a ‘single wave’, consonance is not a single note. It rather refers (at least in modern music) to a specific relationship of a triad that is organised by a single tonal centre. In country music, this occurs in the simultaneous presence of the tonic, mediant, and dominant tones, or the I, III, and V notes of a typically major scale. Dissonance is a select deviation from this basis. The tonic remains the tonal centre, but variations occur in either the mediant or dominant tones.

The inclusion of variations on the mediant tones is an important point, for two reasons. First, Schoenberg rejects such a claim. For him, dissonance is only produced by dropping the dominant tone a full step (forming a diminished chord, e.g. C-E-F) or raising it either a full step or three half steps (forming an augmented chord, e.g. C-E-A or C-E-A#). He designates the dominant with this special power because it shares the highest degree of ‘overtones’ with the tonic.45 As such, it competes with the tonic, being ‘able to threaten the hegemony of the fundamental and claim its governing role’.46 As James Tenney shows, however, there is a historical component to dissonance, which means that its perceived tension is relative to the dominant structures of the time. Schoenberg was himself aware of this idea, at one point declaring his ‘hope that in a few decades audiences will recognize the tonality of this music today called atonal’.47 At various points in history, dissonance included either the presence of multiple tones (regardless of their harmonious relationship), or a tonic accompanied by one or more tonal intervals, ranging from the third to the seventh. The inclusion of the third as a dissonant tone originates in the eleventh century as the gaining popularity of triads began to challenge the largely accepted ‘truth’ of Pythagorean scales.48 Effectively, the third was dissonant because it was innovative. As with Schoenberg’s atonal aspirations, however, it was eventually subsumed under consonance by the end of the fourteenth century, where dissonance was relegated to notes beyond thirds, fourths, fifths, and sixths.49

This leads to the second importance of the inclusion of variations on the mediant tones. Country music lives by thirds. The ‘country sound’ is largely constituted by the mixing of major and minor thirds (and their sixth counterparts) in an idiosyncratic manner. The outcome, however, is that the third is largely unsure of its presence. The (broadly) dissonant elements in this music chiefly arise from playing with the mediant tones either by dropping them a half-step to the minor, or raising them a half-step to form a suspended chord. The overall effect of this musical dissonance is a heightened awareness of the aesthetic event at hand. The selected presence of deviation gathers interest. As it directs attention in terms of perception (i.e., the event of listening) it heightens the resolution of the synthetic phenomena of lyrics and music. On the one hand, this draws a higher quality of attention to the meaning of the lyrical content. On the other, it augments the linguistic meaning through its dissonant tones. Even in an attempt to secure this meaning in the closed realm of rational concepts, the derivative process by which those concepts are produced is infected with this musical inflection. Music’s influence here goes beyond a tacit value of the concept, to a constituent feature of its fundamental sense. Dissonance becomes part of the cognitive judgement, leading along the norms of reason, and transforming them in its wake. The key feature remains: the dynamics of dissonance and consonance in music encourages listening. It heightens awareness, and, through its presence, helps to form a context in which meaning is found.

(b) Willie Nelson, ‘Hands on the Wheel’

Willie Nelson’s breakthrough album Red Headed Stranger (1974) established the structural features of how the genre approaches questions of spirituality. In fact, he is the ‘most significant musical and spiritual legacy of the outlaw movement’.50 The first generation of writers and artists became ‘absolutely disciples’ of Nelson, as Kristofferson recounts—a description which echoes throughout the tradition.51 As one recent retrospective review puts it, the tracks of Red Headed Stranger ‘carry Biblical levels of anguish on their slender shoulders’.52 This sentiment reverberates a 1978 review that suggested the album should be filed ‘next to the King James or Revised Standard Version’,53 going on to recite the testimony of meeting people ‘who have driven hundreds of miles to touch the hem of [Nelson’s] garment. Literally’.54 Dissonance is established in Nelson’s wake along three dimensions: the lyrical content and poetic form; the musicological aspect; and the contours of production.55 These features are re-presented, in differing ways, in two albums over thirty years later: Sturgill Simpson’s Metamodern Sounds of Country Music (2014) and Cody Jinks’ Lifers (2018). These records bring this discussion into a more contemporary context. More importantly, the opening tracks of both these later albums signal two opposite experiences of the possibilities within the spiritual landscape. One embraces its ambiguity, the other reluctantly acknowledges it through anxiety. The most unique augmentation to the basic framework laid by Nelson in these newer articulations is an emphasis on a sort of sacramental symbolism, indicating an interesting shift in this limited corner of the social imaginary within the last decade.

Willie Nelson’s role in establishing the genre of outlaw country is replicated in the interrogation of spirituality incumbent to this musical tradition.56 His 1974 breakthrough album Red Headed Stranger is often pointed to as the beginning of outlaw country—being the first album where the artist had full creative control—and the song ‘Hands on the Wheel’ acts as a sort of historical precedence for the analysis at hand.57 The lyrics themselves are written from a first-hand perspective of a spiritual seeker, and dissonance is present along the three dimensions listed above.

Beginning with the lyrical dissonance, Nelson enters an overtly traditional progression with a Nietzschean line, bringing the coming spiritual tension to a palpable presence. Along with a type of world ‘unhinged from the sun’, the taxonomy of ‘believers’, ‘deceivers’, and ‘inbetweeners’ maps onto Taylor notion of the spins of spiritual positions in modern secularity. As does the disorientated experience of the shift, which leaves the imagined spiritual seeker with ‘no place to go’. A realisation of the conditions of belief articulated by Taylor underlies this disorientation. Nelson himself recounts that, although he always had a ‘powerful spiritual urge’, he would not define it as ‘religious’.58 What seemed to appear initially as an exciting venture into new horizons of transcendence, however, has turned out to be ‘the same old song’ of a morality grounded by the ‘same damn tune’ of some supernatural deity.

At a time, when the world, seems to be spinning

Hopelessly out of control

There’s believers, and deceivers, and old inbetweeners

Who seem to have no place to go

It’s the same old song

It’s right and it’s wrong

And livin’ is just something I do

With no place to hide

I looked to your eyes

And I found myself in you

I looked to the stars

Tried all of the bars

And I’ve nearly gone up in smoke

Now my hands on the wheel

Of something that’s real

And I feel like I’m going home

Beneath the shade, of an oak, down by the river

Sat an old man and a boy

Setting sail, and spinning tails, and fishing for whales

With a lady that they both enjoy

It’s the same damn tune

It’s the man in the moon

And it’s the way I feel about you

With no place to hide?

I looked to your eyes

And I found myself in you.59

In a key chorus, Nelson establishes a set of common facets to the appearance of spirituality in outlaw country while he simultaneously discovers a grounding orientation for the existential dissonance of a secular age. Beginning with these facets, ‘looked to the stars’ (astrology), ‘tried all of the bars’ (alcohol), ‘nearly gone up in smoke’ (drugs) become spiritual tropes in this tradition. They confirm Taylor’s insight that spirituality is an experience with fullness, here articulated by a reinterpretation of natural phenomena and an extra-rational experience of self-consciousness. Even though each of these facets is primarily defined by their material characteristics, their importance is in what lies beyond this definition.

It is also important that none of these facets ultimately bring consonance to Nelson’s spiritual dissonance. The harmony he seeks only comes about through love. ‘With no place to hide’, the disoriented seeker finds ‘something real’ by looking into the eyes of the beloved. Love replaces religion, ‘the man in the moon’, in a glimpse of the influence of the immanent frame. The stability of the meaning found in such a gaze is the basis for the second verse, where it overflows into a child. What ultimately resolves the spiritual dissonance, then, is a proper relationship—an experiential harmony which sets things into order.

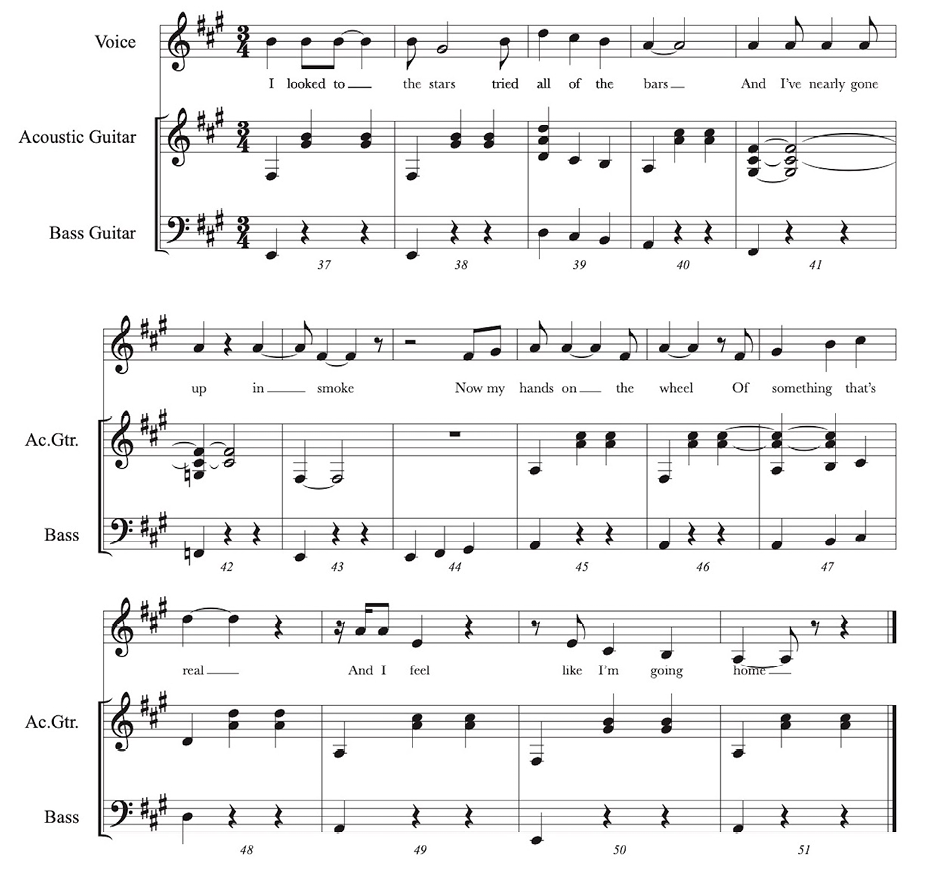

Fig. 6.1 Transcription by author (2024), CC BY-NC 4.0

Musically, the dissonance occurs most powerfully in bars 41–43 of the B-section, where the guitar and bass walk down from the VI to the V. Almost without exception, when a VI chord appears in this genre it is in the form of either a seventh chord (with the voicing here of F#-E-A#-C#) or a minor chord. The important difference is the third of either chord. If the song opts for the seventh chord, then the major third is present; otherwise, it is harmonically present by the minor third. In ‘Hands on the Wheel’, Nelson plays a disquieting fifth chord (F#-C#-F#) as the tempo begins to slow. His vocals remain on an A, filling in the missing third with a minor. A harmonica enters in bar 38, adding a surprising degree of dynamics to the overall quiet composition. It initially harmonises the vocals by adding the relative fourth (E/A-E/D#-F#/D-E/C#-D/B-C#/A), but slightly wavers (following a portamento) between an A# and A in bar 40. Following from the predictable composition thus far, the lack of a third in the guitar voicing seems suspended mid-step. Rather than resolving this tension in the next measure, he compounds it by introducing the major seventh note (F) in the bass of the voicing, yet keeping the A in the vocals, producing the almost atonal chord of F-A-C#-F#. The tempo slows further, before resolving into a major V chord awaiting the bass to walk back up to the I via the third (E-F#-G#). This moment of dissonance happens as the key lines of ‘livin’ is just something I do’ and ‘almost went up in smoke’ are sung. Its effect is to gather attention, but does so without an immediate resolution. In the beats that pass between the walk down (F#-F-E) and the bass initiating the resolving consonance of a major triad, the meaninglessness of spirituality is re-presented, forming the basis for its symbolic articulation. As the context is gathered in this moment, the stage is set for the significance of love. The line which follows—‘now my hands on the wheel…’—is most directly augmented by the musical dissonance.

These features take place, moreover, within a kind of production which was outright startling for the time. Perhaps the best description of the record is thin, almost silent.60 When Nelson presented it to the record label, ‘the instrumentation was so sparse and Willie’s guitar playing so splintered that [the label’s] officials assumed it was unfinished’.61 Paul Nelson of Rolling Stone wrote that the meaning of the album was akin to a Hemingway novel, ‘accessible only between the lines’, in that space between material content.62 Yet, as it was reluctantly released and surprisingly shot up the charts, it became apparent that the record was a shift in the entire country scene. As one reviewer wrote about the record, ‘As likely as not, you won’t like it the first time through, but stick with it. It’ll stick with you for a long time. Masterpieces are like that’.63 Its greatness is a judgment that requires a period of attunement.

(c) Sturgill Simpson, ‘Turtles All the Way Down’

I’ve seen Jesus play with flames

In a lake of fire that I was standing in

Met the devil in Seattle

And spent nine months inside the lions’ den

Met Buddha yet another time

And he showed me a glowing light within

But I swear that god is there

Every time I glare into the eyes of my best friend

…

There’s a gateway in our minds

That leads somewhere out there, far beyond this plane

Where reptile aliens made of light

Cut you open and pull out all your pain

Tell me how you make illegal

Something that we all make in our brain

Some say you might go crazy

But then again, it might make you go sane

Every time I take a look

Inside that old and fabled book

I’m blinded and reminded of

The pain caused by some old man in the sky

Marijuana, LSD

Psilocybin, and DMT

They all changed the way I see

But love’s the only thing that ever saved my life

So don’t waste your mind on nursery rhymes

Or fairy tales of blood and wine

It’s turtles all the way down the line

So to each their own ’til we go home

To other realms our souls must roam

To and through the myth that we all call space and time.64

The basic structure Nelson established reappears in Sturgill Simpson’s masterfully composed ‘Turtles All the Way Down’.65 Here, though, the conditions of the immanent frame are even more apparent in the search for meaning. Not only was Jason Seiler commissioned for the album artwork—notable for his portrait of Pope Francis that adorned the cover of Time magazine in 2012—but appreciation is given to Carl Sagan and Stephen Hawking in the liner notes. The album is a synthetic product of Simpson’s ‘nighttime reading about theology, cosmology, and breakthroughs in modern physics’ alongside personal experience.66 The meaning of traditional forms of religion still lingers, but only in the midst of a radical reinterpretation. The first sung words of the song make this clear.

Simpson documents a spiritual search for meaning that winds through Christianity, Buddhism, and other vaguely defined conceptions of God, before ultimately finding meaning in everyday relationships. He later describes this meaning as love, ‘the only thing that ever saved my life’. This is, significantly, a love which stands in contrast to the ‘pain caused by some old man in the sky’, of whom he’s reminded when he searches in the pages of the Bible. Moving to the chorus of the song, what has ‘changed the way’ Simpson sees the spiritual landscape is his experiences with psychedelic drugs: ‘Marijuana, LSD, Psilocybin, and’, most importantly, ‘DMT’.

In an interview with National Public Radio (NPR) on the inspiration behind both this song and the entire album, Simpson explains that he was extremely inspired by Rick Strassman’s DMT: The Spirit Molecule.67 In this work, Strassman documents a government-funded research project in which he injected several dozen participants with DMT, and subsequently tracked their experiences with specific attention toward notions of spirituality. Strassman argues that there is a correlation between the levels of DMT present in people’s minds and their accounts of religious experiences. The background behind this song uncovers a remarkable insight. As is characteristic of Taylor’s taxonomy of spiritual positions, Simpson is finding meaning of a transcendent quality within the immanent structure of clinical psychology. This is precisely what Taylor refers to as a form of ‘motivational materialism’.68 Returning to Simpson’s lyrics, acting as a ‘gateway in our minds’, the DMT-induced altered consciousness is what reveals that ‘love’s the only thing that ever saved my life’. Love, as experienced in everyday life, an experience with an ‘other’, is a powerful source of meaning within the immanent frame. For Simpson, love has been unhinged from the traditional religious use in Western culture. In a Tillichean sense, it is simply a foundational feature of the world available through a plurality of cultural articulations, an immanent realm that is merely the ‘myth we call space and time’. Upon discovering this insight, we can all ‘go sane’, and proclaim love as the salvation of the world. The great hope of the world is found in this understanding of love: ‘to each their own ’til we go home/To other realms our souls must roam’. Yet, unlike in Nelson, this meaning does not eradicate the need for drugs. Love saves, but drugs shift perspective.

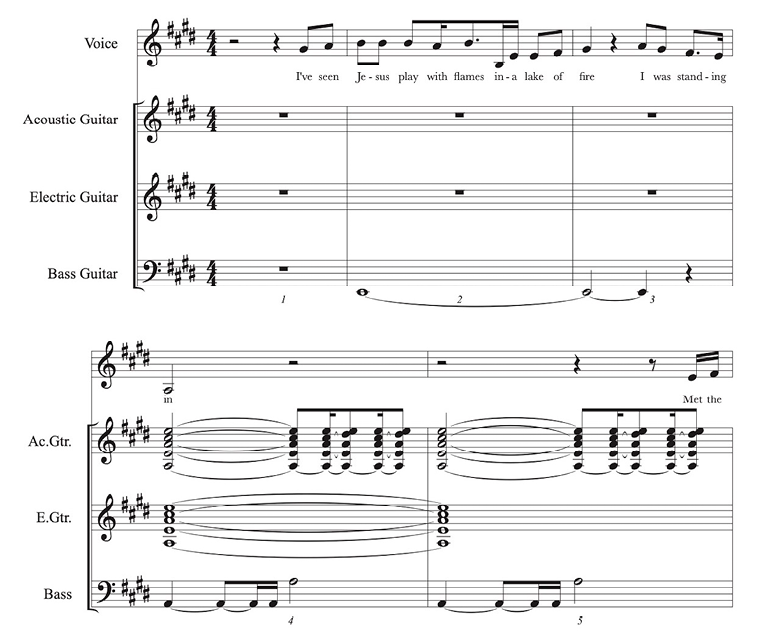

Dissonance in both the composition and production of ‘Turtles’ takes on a form of suspension and augmentation, which are relatively rare in country music. The tonic and semidominant chords (here, the I and IV in E) involve suspending the third up a half-step (A over the E; D over an A). This suspension is compounded on the IV chord as the fifth is also raised to the major sixth (over A, E is raised to F#). These voicings happen as the bass moves between the octaves, which is also a strange choice in the genre. The bass line compounds the suspension in the chords, intensifying the euphoric atmosphere of the track.

Fig. 6.2 Transcription by author (2024), CC BY-NC 4.0

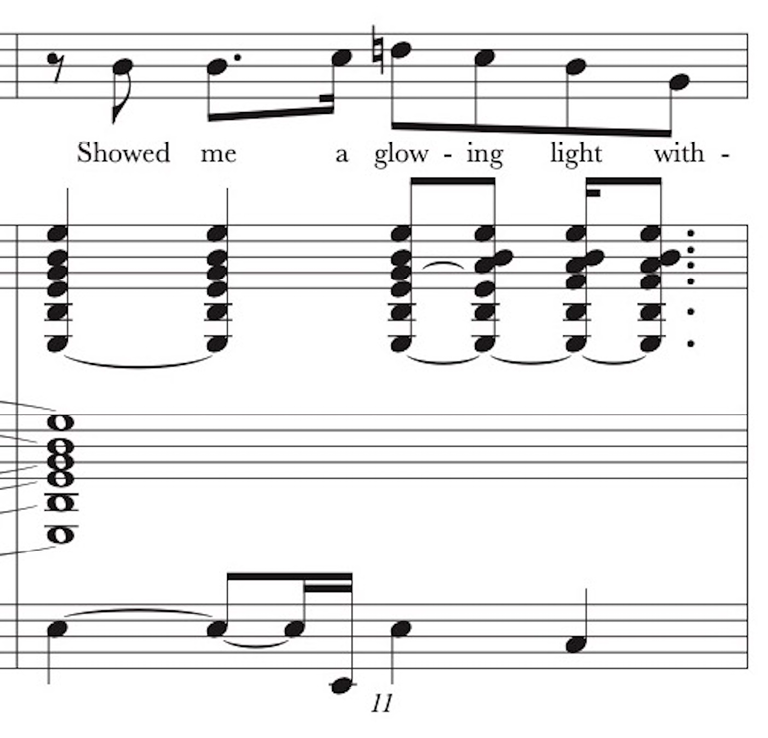

The general use of suspended dissonance reaches a new level in Bar 11. The guitar continues the movement between a suspended E, while the bass sustains its octave line. The vocal melody rises to a D natural, adding a seventh to the major triad. The vocals began a descending scale as the guitar suspends the third. The scale starts on a C#, adding a sixth to the already suspended E. The intensified moment of dissonance attracts the ear, in a sense preparing the reception of its lyrical content, here speaking of the meaning of spirituality as an inner spark of divinity. When all these features are combined, a Stimmung (see Chapter 10 in this volume for further discussion of this term) comes to definition which replicates the psychedelic experience being described. The heavy use of reverb in the production adds to this, further driving home the potency of a chemically-induced spiritual experience.

(d) Cody Jinks, ‘Holy Water’

I walk around on pins and needles

Around people I can’t even name

I keep on passing church steeples

Praying that my God is still the same

I been wandering like a fool too blind to see

Maybe it ain’t the bottle that I need

I need a shot of holy water

I need it to chase down my demons

And burn ’em just a little bit hotter

I’ve been having drinks with the devil in this neon town

I need a shot of holy water to wash it down

Lost in a land of smoke and mirrors

I do my best to just stay clear of my yesterdays

I’ve been running so long, now I’m running from myself

Tired of running away

I’m still tryin’ to get through to the man I wanna be

Maybe I’m not so gone that I can’t see.69

While Simpson exchanges traditional religion in the American landscape for new avenues of spirituality, wholly grounded in a secularised sense of immanence, Cody Jinks ponders if he can still maintain the type of Christianity he knew as a child. Jinks reinterprets Nelson’s emphasis on drugs and alcohol to a similar degree that Nelson and Simpson reinterpret Christianity. He also, interestingly, emphasises a sacramental nature of his spiritual experience. While Simpson warns ‘don’t waste your mind … on fairy tales of blood and wine’, Jinks sees a sacramental encounter—‘a shot of holy water’—as the resolution to the dissonant cross-pressures of the immanent frame.

Simpson’s experience of liberation in the secularised spiritual landscape is countered by Jinks’ anxiety. The immanent ‘other’ here is seen more as a judging onlooker, than the source of salvation. In terms of Taylor’s secularisation narrative, Jinks’s more traditional understandings of spirituality place him in a precarious position within the fragmentation of a novel spiritual context. Jinks understands there are significant and compelling challenges to those old church steeples, stemming from unfamiliar social sources. Yet, rather than turning to some structure of immanence, such as Simpson’s ‘motivational materialism’, Jinks doubles-down on his traditional beliefs, and ‘prays’ to the God who has been proclaimed as ‘unchanging’ throughout the centuries.

Furthermore, the closed posture of Jinks towards newer forms of spirituality is not necessarily based completely on some dogmatic allegiance. There are also powerful critiques against the positions that openly welcome the spiritual substitutions of the cultural topography. One such critique is the seeming inability of immanent structures to provide the ‘fullness of human life’ sought by so many individuals. Jinks describes this quest for fullness as the attempt ‘to get through to the man I wanna be’. He reasons that this goal cannot be found in the ‘land of smoke and mirrors’ that is the source of his spiritual anxiety. Even though he recognises the influence of a secular world on his own beliefs, he also acknowledges that he’s ‘not so gone that [he] can’t see’ that the source of meaning in life still emanates from more traditional forms of religion.

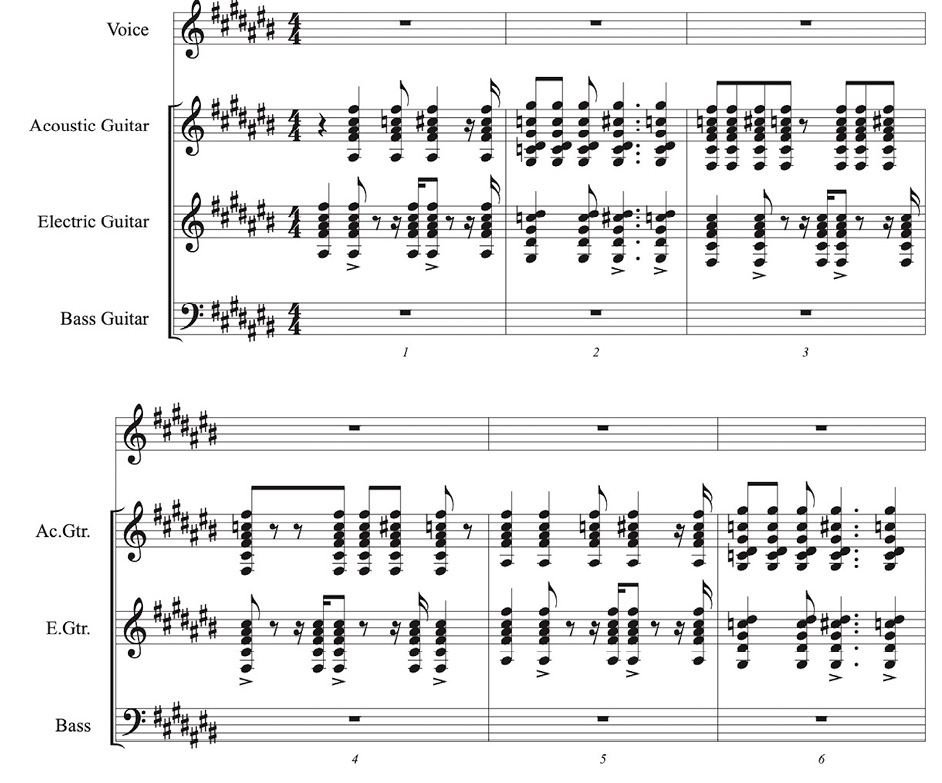

Fig. 6.3 Transcription by author (2024), CC BY-NC 4.0

While Simpson employs psychedelics to guide him through the ever-shifting spiritual landscape, Jinks proclaims that what he needs is ‘a shot of holy water’. Drinking ‘with the devil in this neon town’ has only led to meaninglessness, away from which Jinks is ‘tired of running’. The source of meaning—for this ‘closed’ spin—cannot be found within the immanent frame, but only in a rupture of it. A sacramental aesthetic is its augmentation. It is notable that the material form of this transcendental encounter is in a shot of alcohol. Whisky has replaced wine. Further, Jinks’ spirituality is also more individualistic than Nelson or Simpson. He seeks a sort of self-transcendence of maturation. A process which cannot be participated in without a sacramental encounter. Yet, this comes at a cost. The communal dimension of love is ironically absent in Jinks’ return to God, perhaps indicating that the materialism of the immanent frame is still in control.

In terms of production and overall composition, Jinks’ conversion to country music from metal betrays itself. The deviation from the tradition happens from the outset of the song, introducing the spiritual dissonance of its lyrical content rather than augmenting it as with the other two examples. A distorted guitar plays variations on power chords (i.e., absent of a third; here, A#-F-A#), following the somewhat unusual progression of VI-V-IV (A#-G#-F#). An acoustic guitar imitates the progression, but plays the thirds while oscillating between the two notes of C# and C in a sort of syncopated rhythm. So, on the VI chord the acoustic goes back and forth between a A# minor and a A# suspended chord (A#-C#/C-F#); on the IV between a F# major and an augmented major seventh (F#-A-C#/C-C#). The two guitars play in unison on the suspension of the V (bar 2), forming another interesting similarity with Simpson. The production overall is more in the front of the mix, which exerts an anxious mood given the distorted guitars and rock progression.

Conclusion: A Theological Postscript

A spiritual seeker navigating through the novel conditions of belief, an outright embrace of the immanent frame, and an anxious desire to return to traditional religion all appear as meanings of spirituality in outlaw country. Yet, at their core, they are united in a foundation of dissonance. As such, it is perhaps pertinent to note that, in its broad use, spirituality cannot be directly identified with a theological discourse of a traditional religion such as Christianity. There is no clear pathway from the experience of fullness with these songs to a particular deity. Its ambiguity prevents this. What the hermeneutical dissonance of spirituality does imply, however, is that its ambiguity reveals the fullness of life. In analogous correspondence to symbolic reasoning, spirituality shows the limits of its dialectical counterparts—materiality, traditional religion, fixed forms of dispositional formation, determinative reason—by standing at their boundaries. In doing so, spirituality gives rhythmic value to these more stable aspects. This rhythm does not negate these more determinative dimensions. Instead, it complements them in a certain way. It reveals that life spills over the limits of determination, into a realm that is most appropriately described as aesthetic. This spilling over is dynamic. It is perpetually happening. And, it is precisely this dynamic happening which becomes present in music.

1 Although there is an obvious affinity with an aesthetics of ‘event’ and Lawrence Kramer’s work on meaning in music, the decisive distinction is his focus on a subjectivity. Lawrence Kramer, Musical Meaning: Towards a Critical History (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002), pp. 3f., 146–72.

2 Michael Streissguth, Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville (New York: itbooks, 2013), p. 153.

3 The steady stream of literature on pop music appears to indicate that the once controversial and neglected musical field has been accepted in the discourse of theology and the arts at least in terms of its cultural impact. For such examples, see Robin Sylvan, Traces of the Spirit: The Religious Dimensions of Popular Music (New York: New York University Press, 2002), pp. 2–13; Michael Bull, Sound Moves: Ipod Culture and Urban Experience (New York: Routledge, 2007); Eric Clark, Nicola Dibben, and Stephanie Pitts, Music and Mind in Everyday Life (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); Tia DeNora, Music Asylums: Wellbeing through Music in Everyday Life (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2015), p. 170ff; David Brown and Gavin Hopps, The Extravagance of Music (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018).

4 Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, and Edward Yarnold, ‘Preface’, in The Study of Spirituality, ed. by Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, and Edward Yarnold (London: SPCK, 1986), pp. xxi–xxvi (at xxii–xxvi); Meredith B. McGuire, ‘Mapping Contemporary American Spirituality: A Sociological Perspective’, Christian Spirituality Bulletin 5 (1997), 175–82; Peter R. Holmes, ‘Spirituality: Some Disciplinary Perspectives’, in A Sociology of Spirituality, ed. by Kieran Flanagan and Peter C. Jupp (Surrey: Ashgate, 2007), pp. 23–42 (at 24f); Philip Sheldrake, ‘A Spiritual City: Urban Vision and the Christian Tradition’, in Theology in Built Environments: Exploring Religion, Architecture, and Design, ed. by Sigurd Bergmann (London: Routledge, 2009), pp. 151–72 (at 151–52).

5 Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane: The Nature of Religion (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1987), p. 11; Gerardus van der Leeuw, Sacred and Profane Beauty: The Holy in Art (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 231–61; Sylvan, Traces of the Spirit, pp. 39–44.

6 Paul Heelas and Linda Woodhead, The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), p. 1f; Bryan S. Turner, ‘Post-Secular Society: Consumerism and the Democratization of Religion’, in The Post-Secular Question: Religion in Contemporary Society, ed. by Philip S. Gorski, et al. (New York: Social Science Research Council and New York University Press, 2012), pp. 135–58 (at 136); June Boyce-Tillman, Experiencing Music—Restoring the Spiritual: Music and Well-Being (Bern: Peter Lang, 2016), p. 25ff; Peter Jan Margry and Daniel Wojcik, ‘A Saxophone Divine: Experiencing the Transformative Power of Saint John Coltrane’s Jazz Music in San Francisco’s Fillmore District’, in Spiritualizing the City: Agency and Resilience of the Urban and Urbanesque Habitat, ed. by Victoria Hegner and Peter Jan Margry (London: Routledge, 2017), pp. 169–94 (at 169).

7 Philip Sheldrake, Spirituality and Theology: Christian Living and the Doctrine of God (London: Darton, Longman, and Todd, 1998), p. 6; Wade Clark Roof, Spiritual Marketplace (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), p. 137; Sandra M. Schneiders, ‘Approaches to the Study of Christian Spirituality’, in The Blackwell Companion to Christian Spirituality, ed. by Arthur Holder (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005), pp. 15–34 (at 16–17).

8 Barbara Quinn, ‘Leading to the Edge of Mystery: The Gift and the Challenge’, Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality 22 (2022), 3–19 (at 4); Sheldrake, Spirituality and Theology, pp. xi; 14–32.

9 Charles Taylor, A Secular Age (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), pp. 544–46.

10 Igor Stravinsky, Poetics of Music (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1942), p. 34.

11 As with the term ‘spirituality’, the lack of concise definition of ‘dissonance’ is commonly highlighted. James Tenney, A History of ‘Consonance’ and ‘Dissonance’ (New York: Excelsior Music, 1988), p. 32, n. 6.

12 For accounts of spirituality in Schoenberg’s modern sense of dissonance, see Carl Dahlhaus, ‘Schoenberg’s Aesthetic Theology’, in Schoenberg and the New Music, ed. by Carl Dahlhaus (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1999), pp. 81–93; Pamela Cooper-White, Schoenberg and the God-Idea: The Opera ‘Moses and Aron’ (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research, 1985); Alexander L. Ringer, Arnold Schoenberg: The Composer as Jew (Oxford: Clarendon, 1990). For a critical analysis of Schoenberg’s spirituality from the perspective of Trinitarian theology, see Chelle L. Stearns, Handling Dissonance: A Musical Theological Aesthetic of Unity (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2019), p. 13f.

13 Sean Alexander Gurd, Dissonance: Auditory Aesthetics in Ancient Greece (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016), p. 11.

14 Ibid. Cf. Patrick Colm Hogan, Cognitive Science, Literature, and the Arts: A Guide for Humanists (New York: Routledge, 2003), p. 8.

15 Gurd, Dissonance, p. 11.

16 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, ‘Principles of Nature and of Grace, Founded on Reason’, in Monadology and Other Philosophical Writings (London: Oxford University Press, 1925), pp. 405–24 (at 422).

17 Immanuel Kant, Critique of the Power of Judgment (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000), pp. 205–07 (5:328–30).

18 Arthur Schopenhauer, The World as Will and Representation, Volume 1, trans. by E. F. J. Payne (New York: Dover Publications, 1969), pp. 242–67 (§§51–52).

19 Cf. Taylor, A Secular Age, p. 557f.

20 This concept of ‘event’ is distinguished from ‘musicking’ in that it is not so much speaking to the real-life performance of a musical piece (although it certainly includes this), but more to a shift in meaning from the occasion. In other words, not all performances are aesthetic events. Cf. Christopher Small, Musicking: The Meanings of Performance and Listening (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1998), p. 9.

21 Cf. Nicholas Wolterstorff, Art in Action: Towards a Christian Aesthetic (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1980), pp. 50–58.

22 Martin Heidegger, ‘The Origin of the Work of Art’, in Martin Heidegger, Poetry, Language, Thought (New York: Harper & Row, 1971), pp. 15–86 (at 17).

23 Martin Heidegger, Being and Time (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2010), pp. 30–37 (§7).

24 Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology: Volume I: Reason and Revelation, Being and God (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1951), p. 83; cf. Jeremy Begbie, Voicing Creation’s Praise: Towards a Theology of the Arts (London: T & T Clark, 1991), pp. 35–40.

25 Cf. Eberhard Jüngel, ‘»Auch Das Schöne Muß Sterben«—Schönenheit Im Lichte Der Wahrheit. Theologische Bermerkungen Zum Ästhetischen Verhältnis’, in Eberhard Jüngel, Wertlose Wahrheit: zur Identität und Relevanz des Christlichen Glaubens, Theologische Erörterungen 3 (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 2003), pp. 378–96 (at 388): ‘Being-true means: to be present to one’s self and precisely because of this to be lucid. It applies in the highest way to music, insofar as its truth does not lie in the agreement of intellectus and rei, but only in the event of its tones. The musical artwork is to the highest degree an actuality present in itself: it shines most purely in the light of its own being’.

26 Hans-Georg Gadamer, ‘The Relevance of the Beautiful’, in The Relevance of the Beautiful and Other Essays (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 1–56 (at 33); cf. Paul Tillich, Dynamics of Faith (New York: HarperCollins, 1957), pp. 47–50.

27 Gadamer, ‘The Relevance of the Beautiful’, p. 35. Despite the similarities, this point in particular distinguishes Gadamer’s theory of understanding (and those related) from that of aesthetic cognitivism. There, ‘symbolic understanding’ merely refers to the linguistic or pictorial representation of a claim, as (loosely) opposed to the actual claim in ‘factual understanding’. See, Christoph Baumberger, ‘Art and Understanding: In Defence of Aethetic Cognitivism’, in Bilder Sehen. Perspektiven Der Bildwissenschaft, ed. by Mark Greenlee et al. (Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 2013), pp. 41–67 (at 43f.); Catherine Z. Elgin, Considered Judgment (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996), pp. 170–204. A similar distinction can be made to theories which would attribute some non-rational symbolic meaning to music, but a kind of meaning most closely associated with emotions. For an overview of these kinds of theories, see Maeve Louise Heaney, Music as Theology: What Music Says About the Word (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2012), p. 21f.

28 Gadamer, ‘The Relevance of the Beautiful’, p. 34.

29 Ibid. p. 38.

30 Ibid., p. 36. For a more developed account of music in Gadamer’s aesthetics, see Beate Regina Suchla, ‘Gadamer’, in Music in German Philosophy: An Introduction, ed. by Stefan Lorenz Sorgner, Oliver Furbeth, and Susan H. Gillespie (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2011), pp. 211–32 (at 219–22).

31 Gadamer, ‘The Relevance of the Beautiful’, p. 37.

32 Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, 2nd rev. ed. (London: Sheed & Ward, 1989), pp. 33–35. For a development of a similar point concerning Gadamer’s distinction of ‘understanding’ (verstehen) and ‘knowledge’ (erklärung) and music, see Cynthia Lins Hamlin, ‘An Exchange between Gadamer and Glenn Gould on Hermeneutics and Music’, Theory, Culture & Society 33.3 (2015), 105–07.

33 Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology: Volume III: Life and the Spirit, History and the Kingdom of God (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1963), pp. 160–61.

34 Taylor, A Secular Age, p. 6. In fact, he points to Friedrich Schiller’s fundamental role of ‘play’ as an archetypal example, which Schiller describes as an ‘ästhetische Stimmung des Gemüths’ [aesthetic attunement of the mind/soul]. See Friedrich Schiller, ‘Über Die Ästhetische Erziehung Des Menschen’, in Friedrich Schiller, Briefen. Werke (Stuttgart & Tübingen: Gottaschen Buchhandlung, 1959), p. 90.

35 Taylor, A Secular Age, p. 20.

36 Ibid., p. 542.

37 Ibid., p. 110. Cf. 96–99. Taylor lists materialism, instrumental reasoning (i.e., the methodology of the natural sciences), chronotic (versus chairiotic) time, and a constructed (i.e., not metaphysically grounded) social space as the other features of the immanent order.

38 Ibid., p. 594. Taylor explains that the ‘closed’ spin can seem more natural or obvious within the immanent frame but he demonstrates that it is as influenced by precognitive ‘images’ as the open spin. Among its tendencies is the desire for scientific quantification, grounded in empirical research. This implies, in turn, that the social imaginary has a strong influence on the methodology for investigating into such things as the meaning of spirituality.

39 Ibid., p. 551.

40 Ibid., p. 550.

41 Ibid., p. 555.

42 Ibid., p. 299.

43 Cf. ibid., p. 509f.

44 See, Heaney, Music as Theology, pp. 24–26.

45 Arnold Schoenberg, Theory of Harmony (London: Faber and Faber, 1978), p. 23f.

46 Stearns, Handling Dissonance, p. 23.

47 Arnold Schoenberg, Style and Idea: Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1975), p. 283.

48 Tenney, A History of ‘Consonance’ and ‘Dissonance’, p. 21f.

49 Ibid., p. 39.

50 Streissguth, Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, p. 5.

51 Robert Oermann, Behind the Grand Ole Opry Curtain: Tales of Romance and Tragedy (New York: Center Street, 2008), pp. 296–97.

52 Robert Ham, ‘Classic Album Review: Willie Nelson Turns Outlaw on the Seminal Red Headed Stranger’, Consequence, 17 September 2019, https://consequence.net/2019/09/classic-album-review-willie-nelson-red-headed-stranger/

53 Quoted in Chet Filippo, ‘Willie Nelson: Holy Man of the Honky Tonks. The Saga of the King of Texas, from the Night Life to the Good Life’, Rolling Stone, 13 July 1978, p. 66; Blase S. Scarnati, ‘Religious Doctrine in the Mid-1970s to 1980s Country Music Concept Albums of Willie Nelson’, in Walking the Line: Country Music Lyricists and American Culture, ed. by Thomas Alan Holmes and Roxanne Harde (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2013), pp. 65–76.

54 Filippo, ‘Willie Nelson’.

55 The ‘Nashville sound’ from which outlaw country was breaking free ‘prescribed the length, the meter, and the lyrical content of songs as well as how those songs were recorded in the studio’. Streissguth, Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, p. 2.

56 Nelson records that Levi H. Dowling’s The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ: The Philosophical and Practical Basis of the Religion of the Aquarian Age of the World and the Church Universal (London: L.N. Fowler and Company) held a large influence over his religious thought in general and its interpretation set forth in Stranger specifically. Willie Nelson and Bud Shrake, Willie: An Autobiography (New York: Cooper Square Press, 1988), pp. 114–16.

57 The conceptual album Yesterday’s Wine (1971) is much more explicit with its questions of spirituality, yet, as per the regulation of aesthetic symbols, its reception is neither as immediate nor apparent. See, Scarnati, ‘Religious Doctrine’, p. 67.

58 Nelson and Shrake, Willie, p. 114.

59 Willie Nelson, ‘Hands on the Wheel’, Red Headed Stranger (Columbia Records, 1974).

60 The sonic dimensions as emphasised in analyses of music by the methods of cognitive science could be helpful in articulating this point in a different manner. For example, Annette Wilke, ‘Sonality’, in The Bloomsbury Handbook of the Cultural and Cognitive Aesthetics of Religion, ed. by Anne Koch and Katharina Wilkens (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), pp. 107–16 (p. 107f.). For another example, see, Martin Pfleiderer, ‘Sound Und Rhythmus in Populär Musik. Analysemethoden, Darstellungsmöglichkeiten, Interpretationsansätze’, in Die Bedeutung Populärer Musik in Audiovissuellen Formaten, ed. by Christofer Jost et al. (Germany: Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, 2009), pp. 175–95 (esp. 178–88).

61 Streissguth, Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, p. 180.

62 Paul Nelson, ‘Hemingway, Who Perfected’, Rolling Stone, 28 August 1975); quoted in Streissguth, Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, p. 184.

63 Streissguth, Outlaw: Waylon, Willie, Kris, and the Renegades of Nashville, p. 184.

64 Sturgill Simpson, ‘Turtles All the Way Down’, Metamodern Sounds in Country Music (High Top Mountain and Loose Music, 2014).

65 Even though the title of Sturgill’s album, Metamodern Sounds in Country Music, references Ray Charles’ 1962 breakthrough release, Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, the influence of Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger on Simpson’s Metamodern Sounds is (at least) alluded to in the album’s cover art. See, Figure 6.1.

66 Ann Powers, ‘God, Drugs and Lizard Aliens: Yep, It’s Country Music’, The Record, 17 April 2014, https://www.npr.org/sections/therecord/2014/04/17/304075384/god-drugs-and-lizard-aliens-yep-its-country-music. Simpson elsewhere references Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s concept of the ‘Omega Point’ as an influence. See Chris Richards, ‘Sturgill Simpson: A Country Voice of, and out of, This World’, The Washington Post, 17 March 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/sturgill-simpson-a-country-voice-of-and-out-of-this-world/2014/03/31/46277cce-b8f9-11e3-899e-bb708e3539dd_story.html

67 Powers, ‘God, Drugs and Lizard Aliens’; cf. Rick Strassman, DMT: The Spirit Molecule: A Doctor’s Revolutionary Research into the Biology of New-Death and Mystical Experiences (Rochester, VT: Parker Street Press, 2001).

68 Taylor, A Secular Age, p. 595.

69 Cody Jinks, ‘Holy Water’, Lifers (Rounder Records, 2018).