8. An Inquiry into Musical Trance

©2024 Dilara Turan, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0403.08

Well, there’s one thing to try

Everybody knows

Music gets you high

Everybody grows

And so it goes…1

That music accompanies spiritual experiences is a cross-cultural phenomenon. Manifesting itself through a wide variety of cultural practices, it is the focal point of numerous religious, philosophical, and aesthetic doctrines. The present study attempts to uncover empirically the ways in which this prevailing connection between music and spiritual experiences might and can be demonstrated. This endeavour is challenging due to our current research paradigm, which gives rise to several complicating factors. First, there are diverse ways in which spiritual experiences are conceptualised, leading to further questions about how to establish ecologically valid empirical observations on the subject. As William James observes, mystical experiences are often considered ineffable and transient phenomena.2 How, then, can we account for an experience that is temporary and already beyond language? It is essential, therefore, to clarify the underlying concepts before exploring the connection between music and spiritual experiences further. In the first part of this paper, I establish a framework for the investigation by adopting specific ontological positions on spirituality and empiricism. In the second part, I provide a cross-cultural inquiry, examining documented examples of music accompanying spiritual experiences. Drawing on traditional trance rituals as a case of altered states of consciousness, I present a multi-layered understanding of the intricate relationship between music and spiritual experiences, accounting for cognitive, psychological, and socio-cultural contextual factors. By so doing, I suggest guidelines for identifying patterns in this relationship, providing a pool of examples and potential hypotheses on the question for future research.

I. Paradigms for the Study of Music

and Spirituality

At least since the late seventeenth century, in the wake of John Locke’s grand layout of material and mental substance and how they interact, empiricism has been a driving force behind the outstanding accomplishments of civilisation. As Werner Heisenberg documents in his survey, Locke, countering the claims of René Descartes, asserted that all knowledge ultimately originates from experience, which can be either sensation or the perception of our mental activities.3 George Berkeley further developed this idea by arguing that if all knowledge stems from perception, the concept of real existence becomes meaningless, as it makes no difference to the presence or absence of things whether or not they are perceived. Thus, Berkeley equated being perceived with existence, i.e., subjective perceptions as reality. David Hume took this line of reasoning to an extreme form of scepticism and eventually rejected induction and causation. Hume’s powerful critique was nonetheless accommodated as an exegesis within empiricist thought, a warning about the reductive use of the term ‘existence’; the initial divisions of material–mental and subject–object remained a part, then, of empirical thought.

While Immanuel Kant played a significant role in reconciling the concept of existence, the early twentieth century was marked by the anti-metaphysical movement of logical positivism, initially led by Bertrand Russell and other figures of the Vienna Circle. For Hilary Lawson, this movement aimed ‘to replace Victorian metaphysical philosophy with science and logic’, setting an anti-metaphysical trend that also shaped the scientific method.4 Prioritising the role of evidence and experience over abstract theories and dogma helped establish a more rigorous and rational approach to understanding the world around us, leading to significant advances in science, medicine, and the development of modern social and political systems. However, it also established an object-based ontology of a material reality which can only account for measurable and rational phenomena, leaving out a whole region of human experience. Only later in the twentieth century did empiricism become the central subject of debate among scientists and philosophers, as a shortcoming of logical positivism. In his later work, Ludwig Wittgenstein criticised the positivist idea that all meaningful statements must be empirically verifiable, arguing that this principle is a non-empirical statement that cannot be verified by empirical means. Likewise, Thomas Kuhn focused on the process of scientific revolutions and observed that the nature of the scientific process involves large leaps from one value system to another. Rather than a continuous process of uncovering reality that is objectively out there, Kuhn realised the socially constructed or warranted nature of scientific knowledge. This provided a much better lens to approach empirical demonstration with the tools at hand, opening up a new space for the recognition of formerly neglected areas of human experiences. As reported in Horgan’s documentation,

Kuhn argued that our paradigms keep changing as our culture changes. Different groups, and the same group at different times can have different experiences and therefore in some sense live in different worlds. Obviously, all humans share some responses to experience, simply because of their shared biological heritage, but whatever is universal in human experience, whatever transcends culture and history, is also ‘ineffable’, beyond the reach of language.5

One of the profound attempts to establish a fully developed new metaphysics came from outside academic circles through American writer and philosopher Robert M. Pirsig’s study, known as Metaphysics of Quality (MoQ). In his first book, Pirsig introduces his central term Quality as the undefined source of subjects and objects and suggests that everything that exists can be considered as value.6

Pirsig’s approach diverges from the traditional way of understanding the world, where reality is typically based on either object (materialism) or mental substance (idealism). Instead, Pirsig sees values as the fundamental building blocks of reality itself and breaks reality into two categories: Dynamic Quality and static quality.7 Dynamic Quality is a term that describes the ever-changing and immediate experience of reality, while static quality refers to any concept that is derived from this experience. The word ‘Dynamic’ highlights the fact that this experience is not fixed or static and cannot be fully defined; it is prior to conceptualisations. Therefore, an accurate understanding of Dynamic Quality can only be gained through direct experience:

At the moment of pure Quality perception, or not even perception, at the moment of pure Quality, there is no subject and there is no object. There is only a sense of Quality that produces a later awareness of subjects and objects. At the moment of pure Quality, subject and object are identical. This is the tat tvam asi truth of the Upanishads.8

While recognising the undefined, immediate, and pre-intellectual Dynamic Quality, MoQ also accounts for static quality patterns, which Pirsig conceptualised in four layers in an evolutionary hierarchy: inorganic value patterns, biological value patterns, social value patterns, and intellectual value patterns. He argued that the static patterns cover the traditional Western duality of subjects and objects, with inorganic and biological values corresponding to what have traditionally been considered objective, and social and intellectual values to subjective. Contrary to Dynamic Quality, which is undefinable, the static quality layers are rational and understandable. MoQ alters the metaphysical ground by containing the subject–object division within static layers without conflicting with the existing positivist observations; it also enables, however, an account of formerly neglected experiences of reality.

The Metaphysics of Quality subscribes to what is called empiricism. It claims that all legitimate human knowledge arises from the senses or by thinking [based on] what the senses provide. Most empiricists deny the validity of any knowledge gained through imagination, authority, tradition, or purely theoretical reasoning. They regard fields such as art, morality, religion, and metaphysics as unverifiable. The Metaphysics of Quality varies from this by saying that the values of art and morality and even religious mysticism are verifiable and that in the past have been excluded for metaphysical reasons, not empirical reasons. They have been excluded because of the metaphysical assumption that all the universe is composed of subjects and objects and anything that can’t be classified as a subject or an object isn’t real. There is no empirical evidence for this assumption at all.9

MoQ not only encompasses spiritual experience but also places it at its centre. Pirsig further elaborates on the interchangeability of his central term Quality with value and spirituality. Recognising both the Dynamic, ineffable experience and the static (patterned) experiences of spirituality, he provides a comprehensive account of spiritual experiences in MoQ:

Quality and spirituality are synonymous, so that a metaphysics of quality is in fact a metaphysics of spirituality. There is Dynamic spirituality, which is undefinable; and static spirituality, which consists of intellectual spirituality (theology), social spirituality (church), and biological spirituality (ritual).10

An empirical demonstration of spiritual reality would have no place in object-based metaphysics, as such a demonstration cannot extend its investigation beyond the realm of subjective experiences and, therefore, cannot be a subject of scientific research However, through the lenses of MoQ, we can reconcile reality and Quality, or spirit. The question at hand, in turn, can be rephrased: how can we explore the connection between the Dynamic spirituality and static spirituality that involves musicking?

II. An Inquiry into Musical Trance

MoQ allows us to observe music’s involvement in each static pattern and their relation to each other. This study adopts a modular and systematic approach, utilising a multidisciplinary perspective to observe musical trance phenomena from three different angles. The first sub-section focuses on cognitive and psychological theories of spiritual experiences and examines music’s role in the patterns of biological spirituality. Borrowing the term altered states of consciousness (ASC) from cognition and psychology literature, this section seeks to understand the brain mechanisms and cognitive functions during spiritual experiences. Considering musical trance as a sub-category of altered states of consciousness, it delves into cognitive theories of musical trance, exploring auditory processing mechanisms and emotional arousal. The second sub-section observes intellectual and social patterns in cross-cultural examples of musical trance. By presenting a collection of examples from various parts of the world, it delves into the belief systems and social contexts of rituals and how they shape the overall spiritual experience. The third sub-section takes a music analytical approach, providing a detailed examination of the musical activity and its psychoacoustic and perceptual capacities. Utilising perceptual music analysis of recordings, I will discuss prominent sonic events and common means of musical signification in spiritual experiences. By examining musical trance as a case of music and spirituality, where music accompanies non-ordinary experiences, the study embraces a framework that accommodates both the ineffable and observable, allowing for a deeper understanding of the intricate relationship between music and spiritual experiences.

(a) Music and Altered States of Consciousness

ASC refer to significant deviations in subjective experience from the normal functioning of waking consciousness, induced by physiological, pharmacological, or psychological factors.11 These alterations are linked to changes in the default mode network (DMN), a large-scale brain network responsible for higher-level cognitive processes like self-referencing, social cognition, and theory of mind. The DMN’s regular functions, involving the preservation of our sense of self and autobiographical memory, remain largely unchanged during waking states due to its high metabolic rate and energy consumption.12 During ASC, the coupling between the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and the prefrontal cortex (PFC) can decouple, as it was observed in a psilocybin research study.13 PCC deactivates, leading to decreased meta-cognitive functions such as self-referencing and mind wandering, while PFC activity enhances, resulting in increased integration of input data and attention level in goal-oriented tasks. The study also suggests that during ASC, various brain oscillatory rhythms, such as alpha, theta, and gamma, can promote the structured activity of the DMN and influence the sense of self. They observed that during psilocybin-induced ASC, alpha activity in PCC decreased, and theta activity increased, correlating with a weakened sense of self and an experience of the supernatural. Another observation during ASC is the decoupling of the DMN and the medial temporal lobe (MTL), which includes hippocampal structures responsible for declarative memory. This decoupling reduces the synchronisation and organisation of DMN activity, impacting the integrated sense of self and clock time perception.14

We can observe two main approaches to the question of the functions of music in altered consciousness states: particularist and mechanistic. The particularist approach of ethnomusicology highlights emotional arousal as the link between music and trance. Ethnographers often report from the field that the emergence of ASC in ritual settings primarily depends on communally shared cosmology. Individual participants of the ceremony share the same predictable expectations, intentions, and behaviours, which create a social/communal space. This predictability and intentionality enable the trancers, especially those in charge of leading the ritual and music, to interact with the music in response to their emotional states for the emergence of trance possession. In other words, trancers often know how to alter their consciousness via interactions within that extremely static ritual setting. Concerning the importance attributed to pre-set cognitive familiarity, music functions as a catalyst for trance experiences and not as a direct element of induction. Thus, ethnographers do not propose a causal relation between the trance state and the specific properties of music specifically. Instead, music, combined with all the other psychological factors of a ritual setting, creates strong emotions, which cause chemical alterations in serotonin, dopamine, and oxytocin levels in brain structure. Thus, this theory suggests that the whole process might give way to alterations in consciousness and the frequently mentioned effects, such as loss of sense of self and other changes in attention, alertness, or time perception.15

The emotional arousal theory of trance explains many common features of trance rituals, such as communal settings, shared cosmology, or religious context, and the importance of cultural and social familiarity between the trancers and strictly followed ritual conventions. It also elucidates why some ritual settings promote the emergence of ASC experiences for some people, while the same music and setting might be meaningless, boring, or disturbing for others. Gilbert Rouget and Judith Becker highlight the great diversity and specification in the musics and ritual settings of various cultures concerning the particularistic point of view. Due to such effective involvement of cultural variables, they also stress the problems of making direct causal relations between musical qualities and trance induction. Both Rouget and Becker attribute a psychological function to music, which enables the person to break his or her self-perception and identify with the spiritual experience. In this way, music has a culturally shaped mediator function as a catalyser to overall experience rather than a sonic inducer with formal musical characteristics. While avoiding music-specific induction theories of trance applicable to different cultures, they also agree that cross-cultural examples depict a distinction between high and low arousal-emotional states. High arousal emotional states are expressed by extremely active body movements and caused by over-sensory stimulation in communal religious/ritual settings. Ecstasy, on the other hand, is characterised by top-down processes like meditation or contemplation, with low-arousal emotional states that result in immobility, silence, solitude, sensory deprivation, and relaxation.16

However, a more mechanistic point of view was introduced in the 1960s. Rodney Needham pointed out the predominant use of percussion instruments and rhythmic devices in ritual settings across different cultures, suggesting that drumming specifically affects the brain and body, inducing altered states.17 Similarly, Neher conducted experiments on the relationship between brainwaves, particularly theta and alpha ranges, and sound waves similar to drumming sounds of traditional rituals in terms of drumming frequencies.18 He proposed that loud sound waves at very low frequencies travel bottom-up the afferent auditory pathways and entrain with the brainwaves. By imitating the electroencephalogram (EEG) correspondence of theta and alpha patterns, which are 3–8 Hz drumming beats per second (theta) and 8–13 Hz (alpha), he observed observable brainwave responses to drumming via scalp electrodes. In a relatively recent study, Melinda Maxfield also observed that drumming has specific neurophysiological effects on listeners, including a loss of the time continuum, alterations in body temperature, emotional arousal, extraordinary imagination, and possible entry into ASC.19 Later, Jörg Fachner suggested that music is capable of shaping our subjective time perception concerning the amount of sensory information per minute.20 Currently, the mechanistic view is often referred as brainwave entrainment (BWE) which suggests that a rhythmic sonic stimulus can synchronise with and influence brainwaves. BWE involves using pulsing patterns in stimuli to elicit a frequency-following response in brainwaves, aiming to match the frequency of the stimulus. Entrainment can be achieved through auditory, photic, or combined stimuli.21 The mechanistic view of music and trance is often criticised for its reductive approach to the involvement of cultural and psychological factors while assigning a strong emphasis to the sonic qualities. In fact, the early studies on drumming effect later raised the famous critique of experienced ethnomusicologist Rouget, who suggested that if it is true, then ‘half of Africa would be in a trance from the beginning of the year to the end’.22

Returning to the inquiry into whether sound can induce or facilitate ASC, the auditory entrainment theory offers a basis for hypothesising a musically induced form of altered states. While laboratory studies explore sound as a potential cue in entraining brainwaves during ASC, the particularist perspective tends to reject the idea of inherent sound effects. Nonetheless, both viewpoints cannot be entirely disregarded, as establishing a causal relationship at the initial point remains challenging. It is worth noting that the association of music with religious and ritual contexts is a pervasive feature in the context of musical performances23, suggesting that auditory entrainment as a phenomenon may be attributed to cultural memories of musical trance acquired over centuries, rather than being an innate aspect. Nevertheless, this does not necessarily discount the possibility of a biological experience of sound and its impact on the body at more fundamental levels, such as bodily responses to low-frequency loud sounds or repetitive exposure. The particularist approach emphasises the cultural and social context of music in trance rituals, while the mechanistic perspective explores the direct effects of sound on the brain and body. However, I argue that these two perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Rather, music simultaneously engages in both layers, with the particularist view highlighting its involvement in social and intellectual static patterns, and the mechanistic view explaining its role in biological static patterns.

(b) A Cross-Cultural Overview

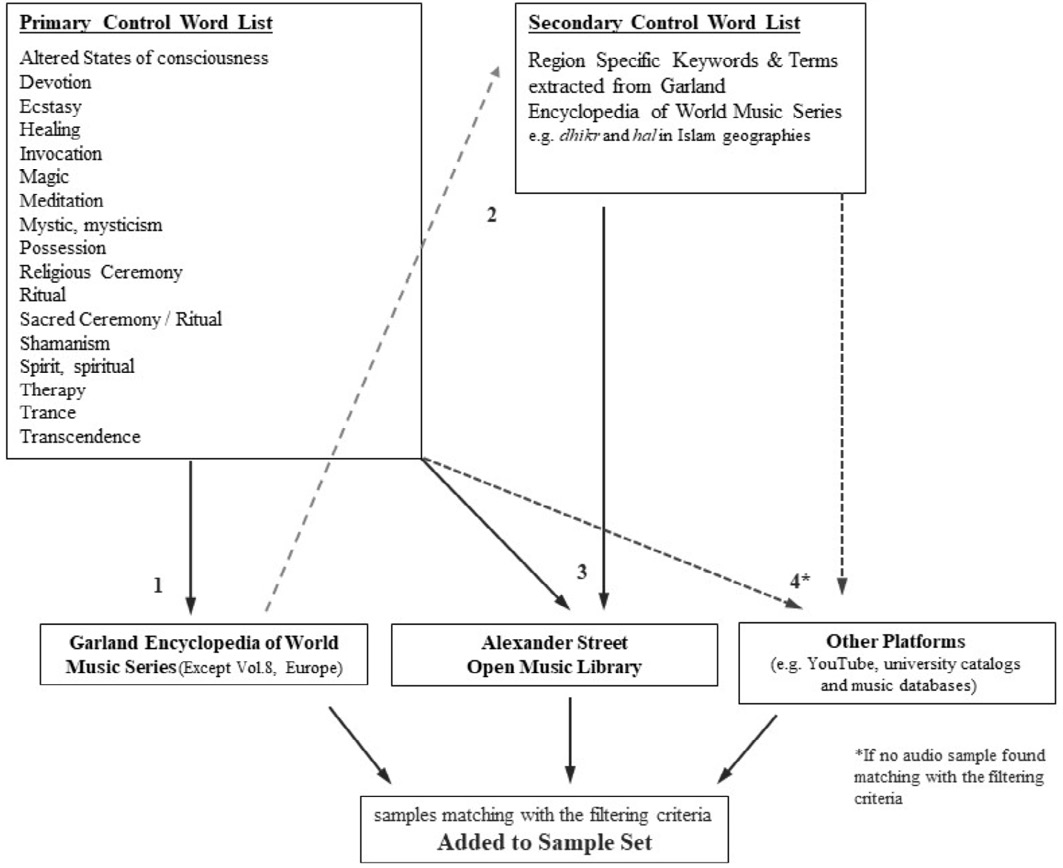

Building on the concepts discussed above, the following sections explore trance examples traditionally associated with altered states of consciousness. The objective is to observe the co-occurrence of various sounds and trance behaviours in light of the theories of musical trance presented above. To collect relevant examples, a two-step process, along with an additional strategy, is employed (see Figure 8.1). In the first step, controlled words that could potentially lead to the identification of musics and musical traditions associated with ASC are scanned in the indexes of the Garland Encyclopedia of World Music volumes, except for Volume 8: Europe.24 Subsequently, the same list of controlled words is used to search the Alexander Street Press Online Music Library, with each region’s name, and the results are filtered based on the information provided in the liner notes before including them in the sample set. Given that trance rituals are frequently encountered without explicit tags from the initial list of control words, but instead are described using original culture-specific terminology, such as ‘dhikr’ (a devotional practice aiming to induce a type of ASC called ‘hal’), the process led to the development of region-specific secondary lists of control words.

Fig. 8.1 Sampling methodology. Created by author (2017), CC BY-NC 4.0

In order to examine comprehensively the involvement of socio-cultural contexts, I conducted an analysis of various factors that shape the surface setting and ritual behaviours, including the belief systems providing the theological background for these customs and the modes of interactions through which individuals engage with these cultural ties. To observe these aspects systematically, a set of questions was formulated for each sample and available information was organised into clusters using open coding. These questions were as follows:

- What belief system, religion, and theology form the conceptual foundation of the experience?

- What type of ceremony is it, and what are the defining characteristics of the cultural context of the ritual at the level of action and surface setting? How is the ceremony named?

- How is the experience conceptualised, and what are the motivations and intentions behind the ritualistic practices leading to an ASC?

- Is the experience predominantly a collectively shared group experience or more individual in nature?

- Based on the general categorisation of musical trance types according to emotional states (high arousal/active and low arousal/still), which type of musical trance best describes the given example?

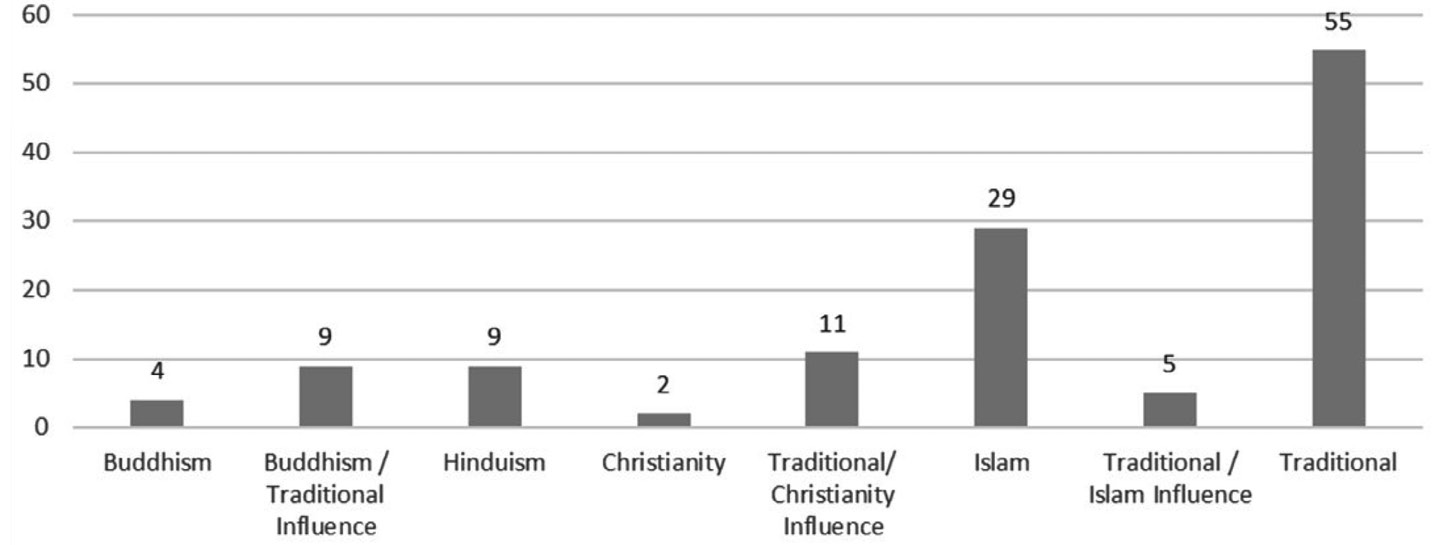

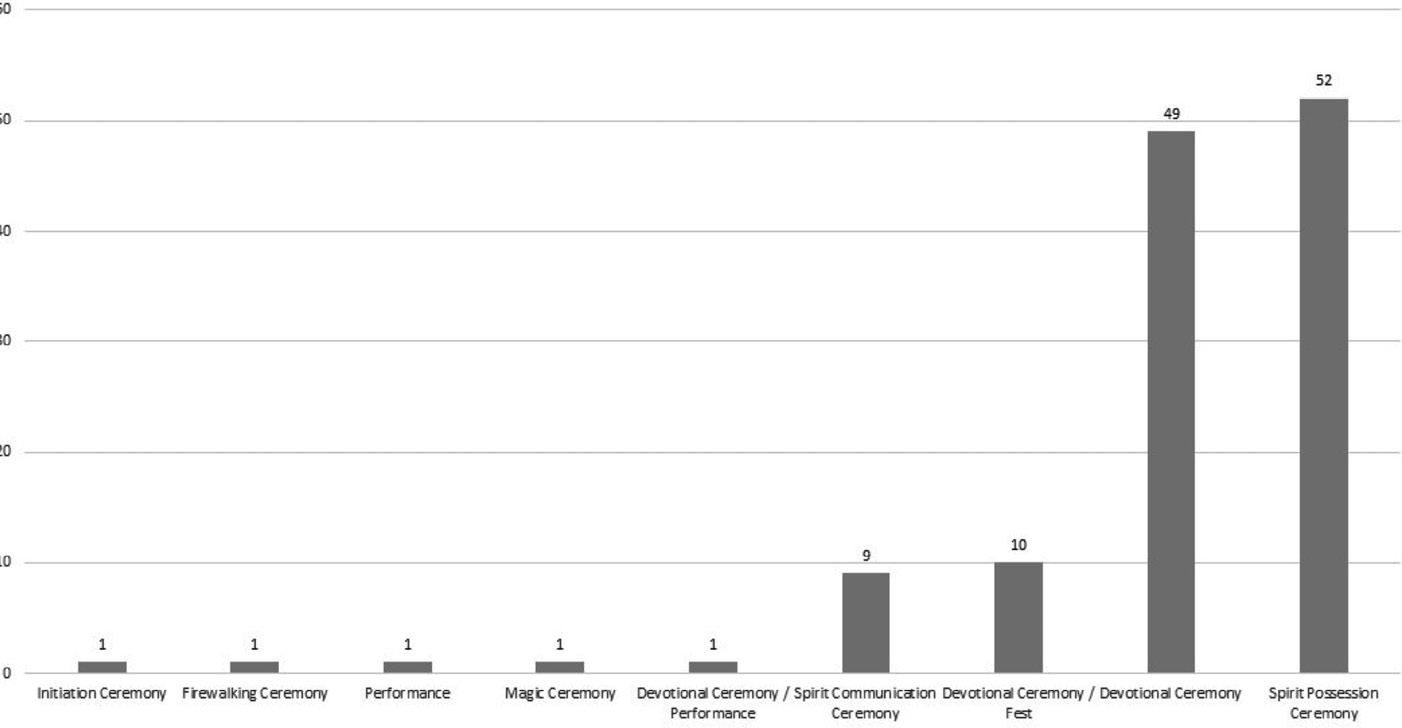

As can be seen from Figure 8.2, for each example, a religion or belief system is indicated as the central underlying theme shaping the ritual context. Among the observed religious practices, it is salient that the traditional belief systems of regional cultures constitute the largest category compared to the Abrahamic religions. Secondly, the two largest categories of ritual context are spirit possession and devotional ceremonies, as shown in Figure 8.3. The culture-specific definitions of these ritual categories suggest a certain level of mental readiness and attentiveness required from the participants.

Fig. 8.2 Number of examples by religion/belief system. Created by author (2017).

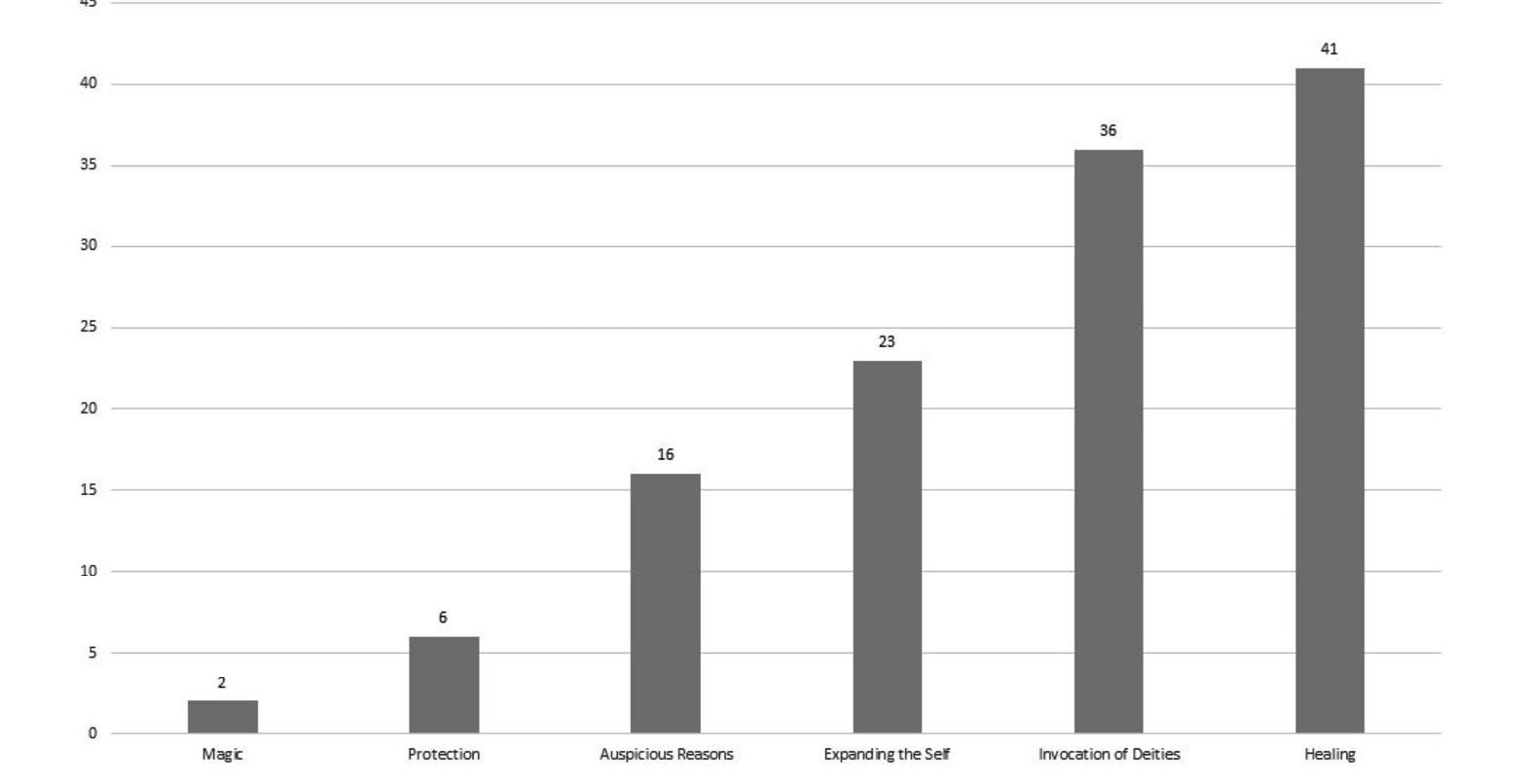

Furthermore, in addition to the theological aspects, the phenomenon of musical trance also exhibits associations with social patterns and ordinary life events. As evident in Figure 8.3 and Figure 8.4, the examples indicate that participants have specific objectives and structured practices in advance while engaging in trance activities. Notably, the largest category of these objectives revolves around physical or psychological healing (see Figure 8.4), followed by invocations of deities to address practical issues like drought, security concerns, or individual matters. This suggests a well-defined cultural aspect of trance practices as a social pattern where participants organise the experience, and anticipate positive outcomes, leading to enriched meanings and emotional states associated with the ritual.

Fig. 8.3 Number of examples by ritual context. Created by author (2017).

Fig. 8.4 Number of examples by ritual function. Created by author (2017).

Another noteworthy aspect is the prevalence of communal social settings in many examples, emphasising the significance of shared ritualistic behaviour and psychological dynamics. As Fig. 8.5 shows, it is more often the case that trance rituals are held in communal settings.

Fig. 8.5 Examples by social setting of ritual. Created by author (2017)..

The existence of such static patterns, including ritualistic behaviour and the underlying theological context, empowers trancers with the knowledge and means to alter their consciousness, as postulated by Becker.

(c) Sonic Signification in Musical Trance

The culturally-oriented perspective, however, overlooks the direct influence of organised sounds on the bodily experience of trance. This neglect of the biological experience of sound events and their psychoacoustic impact on consciousness calls for a closer examination of sonic parameters to bridge the gap between cultural and musical explanations. Such analysis addresses the signification of sounds in the auditory experience, following Bob Snyder’s three-part model of auditory processing.25 Given the importance of auditory entrainment theory for understanding the relationship between music and ASC, specific focus is placed on sonic properties related to temporal aspects, such as pulsation, tempo, rhythmic groupings, and the arrangement of musical layers. Timbral and textural features are also considered. The analysis process consists of two main steps. First, a subjective ear-based analysis is conducted, accompanied by a comprehensive review of ethnographic notes to gather basic information, such as instrumentation or duration. Subsequently, the samples undergo sound analysis using the Sound Visualiser, where the Constant-Q Spectrogram is employed to analyse texture, layering, and repetition, while the Tempo and Beat Tracker Onset Detection Function is utilised for tempo and beat detection.

The prevalent sonic qualities observed in musical trance are closely tied to temporality and can be understood as manifestations of statistical regularity, representing various static sound units. In music, regularity is commonly discussed in the context of repetition, which often involves repetitive pitch content like ostinato lines or refrains. However, in the context of musical trance, regularity units manifest in a variety of forms, including but not limited to steady pulsations, repetitive short figures, drone tones, interlocked textures, siren or signal-like motions, drumming spectra, as well as simple melodies or short percussive loops.

Statistical regularity plays a significant role in auditory functions, encompassing tasks like streaming musical layers, maintaining auditory continuity, detecting temporal values, and facilitating musical memory.26 Accordingly, it suggests that sonic events with recurrent patterns are more accessible to auditory processing, and this cognitive ease facilitates embodiment, anticipation, memorisation, and participation during musical trance experiences. By providing ease in auditory processing, the prevalence of regular sonic elements imparts a sense of ‘freedom, luxury, and expansiveness’ as aptly expressed by John Ortiz.27

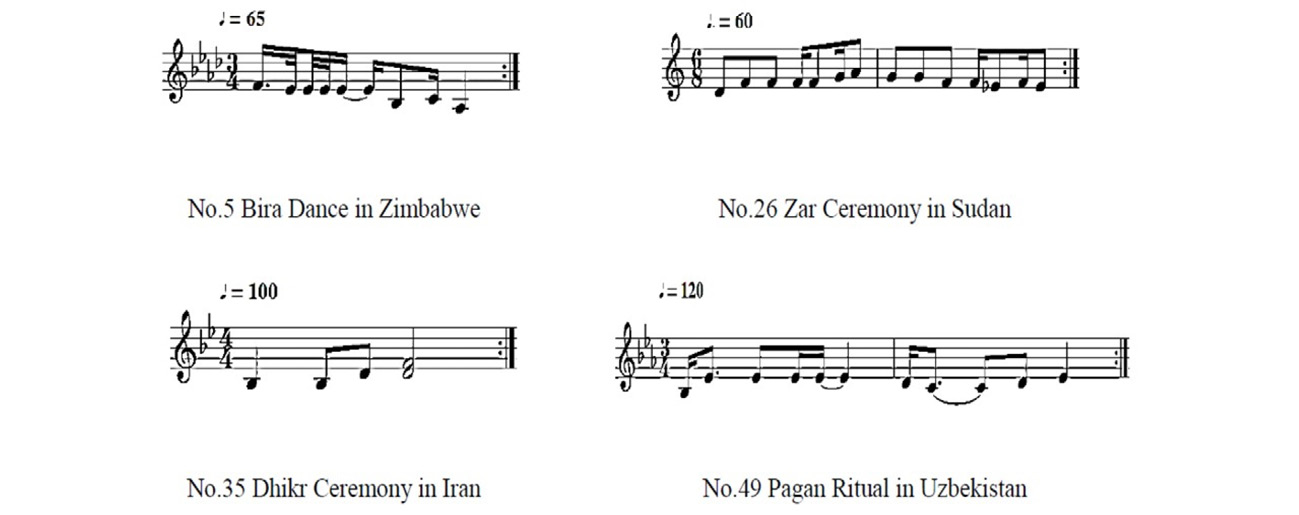

One of the static sound units observed in musical trance is the melody. In the majority of collected examples, a single specific melody is prominently present, with approximately 78.4% of instances being sung. Repeating melodies are often formed as a single motivic figure that is no longer than the period of short-term memory processing, and they are simple by having a small number of pitches moving by smaller intervals, repeated through the flow without a significant change (see Figure 8.6). These melodies incorporate a verbal context that relates to the cultural content of the trance experience, encompassing curing songs, spirit songs, and modes and melodies associated with deities. Because melodies, in general, tend to be listened to and perceived through ‘mental schemas, developed from early childhood in the course of hearing many of the culture’s melodies’ with this joining of the musical and semantic content, melodic units serve as effective sonic signifiers.28

Fig. 8.6 Melody transcriptions of examples No. 5, 26, 35, and 49.29 Created by author (2024), CC BY-NC 4.0.

One other common observation is the employment of drumming effects. 98 out of 125 examples in the sample set employ at least one percussion instrument, and 86 out of those 98 examples utilise an idiophone (30) or a membranophone (26), or both (30). Those percussive instruments are primarily associated with sacred meanings relating to the contextual specification of trance rituals. The association of drumming and healing rituals is especially widespread across large geographies. The most frequently observed drumming instruments are frame drums, sticks, and maracas. Aerophones are the second most employed instruments. In most examples, drumming is utilised constantly as the most active and continuous layer in the overall flow. This parallels previous studies30 on the associations of drumming as a sonic cue for spiritual experiences.

Pulsation (steady drumming) and rhythmic units (patterned drumming) are observed as the two most common units of temporal regularity. While pulsation and rhythmic units are mostly played on percussive instruments, they can also be voiced variedly on other instruments and the human voice, as in the case of Kecak of Bali (example numbers 77–78). Pulsation is the time level often conceptualised as points in musical time that we can easily detect and tap into, which is also considered as a stimulus for auditory entrainment. On the other hand, rhythmic units differ from pulsation having a more figurative character (patterned) in contrast to the steadiness of the pulse. Pulsation mostly uses isochronal and non-accentuated ways, resulting in pure steadiness. They are distinctive in the entire sound because of their higher volume at lower frequencies, especially when played in frame drums, and they rarely go silent during the musical flow. No. 10 and No. 110 are examples of this periodic membranophone pulsation. When the steady pulse is signified in sticks like light idiophone percussions, its sound is distinguishable, resembling a metronome beating, as No. 2, No. 51, or No. 87. Pulsation can also be signified via hand clapping and other body percussions, as in the case of No. 40.

Rhythmic units observed through the sample set significantly differ in temporal structure. Except for drone-based examples, almost all the examples employ at least one layer of a rhythmic unit in a percussive manner, and most have at least two simultaneous layers of patterned rhythms (beside pulsation). The internal structure of rhythmic units in musical trance is mostly short in duration, simple in temporal divisions, and grouped with the pulse level, allowing ease in entrainment. Rhythmic units also function as accompaniment layers filling the texture. Example numbers 5, 13, 24, 29, 58, 63, and 79 explicitly show the accompaniment function of rhythmic units in the drumming layer.

Although the static units in musical trance are often short in length and simple in internal structure, the way they relate to each other, the texture, offers a unique listening experience. In most examples, units are temporally interlocked to each other, creating a synchronised overall beating pattern formed by all the sounding parts of the texture, often called composite rhythm. The composite rhythm can be audible or implied via the functions such as auditory continuity and temporal streaming.31 The synchronisation of units is dense as units are linked in more than one way to each other. The interlocked texture in musical trance offers enough comfort in streaming yet also creates a unique experience of musical time, allowing multiple dimensions simultaneously. Such a perception of musical time is termed as the ‘pure’ ostinato ‘cyclic’ time category in Michael Tenzer’s cross-cultural topology of musical time. Ostinato cyclic time refers to the extremely ‘statis’ type of musical time in which the pulsation ‘structurally’ matches with other units in the higher temporal hierarchies, and ‘the unchanging identity’ of rhythmic and melodic units creates the ‘static aspects’.32

The combination of these tendencies, at extreme degrees, promises a higher potential of musically induced trance states due to their compatibility with the general principles of sound processing and auditory entrainment. Based on this observation, we can hypothesise that the possibility of a sound-induced trance experience increases according to the varying employment of the means of sonic signification listed. Numbers 1, 8, 10, 26, 28, 44, 58, and 110 are examples of such strong combinations of sonic qualities.

Another unit under examination is tempo, which plays a significant role in musical trance. Faster tempo examples, ranging between 80 and 150 beats per minute (bpm), correspond to high arousal bodily active states, and the majority of the examples are in this category. However, there exists a smaller group of examples characterised by extremely slow tempi, ranging from 20 to 50 bpm, indicative of low arousal meditative states. These diverging tempi in extreme ranges, either slow or fast, align with the conventional types of trance and serve as indicators of low- or high-arousal emotional states. While the examples with slow tempi lack pulsation or any indication of periodic beats, making them seemingly incompatible with auditory entrainment theory, they still conform to the essential idea of statistical regularity. With an impression that the music might stop, they contribute to the overall sonic regularity observed. Drones, for instance, are simply the exact perpetual sounding of a single tone. It is also true that the continuum-like melodies have a static character since the frequencies are changing too slowly to form a perceivable patterned order. Conceptually, the vertical temporality percept caused by the fast tempo-pulsation stream is replaced with a single sonic event that is the very slow continuum. The smoothly and slowly changing frequency content is the only motion of shift. Although it favours a comparatively more linear time perception because of its form of a continuum, it also allows for a unique experience of musical verticality by slowing down the time percept as though it will stop.

Many of those slower tempo examples are performed in a communal setting where the participants mostly chant in a monophonic texture. We can point out two important psychological and perceptual effects of communal chanting as a means of sonic signification in trance experiences. First, it is a very effective way of creating a shared musical atmosphere, providing a single-line sonic experience sung and heard by all. Additionally, because of its semantic content, chanting can also be a cue to the shared theology and social side of ritual activity. The following lines describe the communal chanting experience in Kirtan singing:

The auditory space resonates synchronously with the beat of the heart. The tactile sensibilities are equally in operation as people sit close together singing. Boundaries dissolve as the skin of individuals touches, and their discreate voices merge in unison. The intense emotion and devotion that results creates an altered perception and an indomitable community spirit. In such settings, the embodiedness of each listener ‘carries an anticipation of others’ bodies’.33

Group chanting psychology is often associated with the common themes of religious altered state experiences, such as the unity in the Oneness or the dissolution of the sense of self. With regard to Buddhist music, Williams comments:

Chanting certainly is capable of assisting in the creation of a heightened state of consciousness in the performer. When a person performs Buddhist music as a part of crowd of chanters, the individual self disappears into the Sanga, or community … Group chanting, mostly in unison, causes the self to become absorbed into the community.34

Besides the socio-psychological effect that it provides for ritual setting, it is also true that certain sonic qualities in communal chanting might relate to the issue of musical trance. It is often the case that even though the chanting is primarily signified in monophonic texture with a linear continuum, the spectra of the entire sound are not information-poor perceptually, since the communal singing, especially in unison, creates its own density in a type of heterophonic texture. Often the listening experience of communal chanting is highly tense because of the high-volume level, enriching the spectra. It is also true that frequencies used in monophonic chanting tend to be at lower ranges of spectra, creating a more elaborate experience of overtones and other spectral details of the sonic event. These lower-frequency sounds are also favourable in a musical trance since they are more effective regarding the bodily experience of sound.

Conclusions

Neither the listed sound components nor their statistical dominance in the sample set can prove a causal relationship between sound-specific aspects and trance experiences in terms of inducement. However, the presence of the listed tendencies in musical trance examples indicates a high potential for facilitating trance states. The decreased activity of the PCC in DMN, which is generally associated with the meta-cognitive functioning in higher brain regions and long-term memory, has parallels with the preference for using short and basic sonic materials that are processed easily in the early chains of auditory processing. Pulsation and drone continuums are extremes of this type of directly detected sonic units without referencing the long-term musical memory storages. Additionally, the simple and reoccurring character of melodies in musical trance might reduce the need for a re-entrance process in higher brain regions. In comparison with musics such as Eurogenetic art compositions or popular songs, it can be said that in trance music, there is a tendency to use sonic materials that are processed concerning veridical perception, which is the direct perception of stimuli as it exists in the given moment, unlike the schematic expectations that are the result of long-term memory formed by earlier exposure to music.35 The excessive use of statistical regularity or repetition in trance music and its vertical time perception might be related to the increased activity of the PFC functions in integrating input data and attention during the trance states. It is true that non-progressive music has more potential in directing attention to the very moment of the musical flow rather than the linear movement. The predominant use of short static sonic events over the linearly patterned ones might contribute to a more focused, moment-to-moment musical experience of the composite sound.

Another deviation in the brain regions observed during altered states of consciousness is the decoupling of the MTL with the DMN system, and it is proposed that it might distort the perception of clock time, which also contributes to the sense of self. Similarly, it is observed that most of the sound-specific aspects are related to the temporal qualities in musics. As is indicated, there is a tendency to use non-harmonic sounds caused by the predominant use of percussive sounds rather than harmonic pitch patterns. This directly leads the attentional focus to time-related aspects, such as the pulse, rhythms, tempi, and flow, which can be considerably more effective in altering the time perception. These sound-specific tendencies observed in the sample set are proposed as the psychoacoustic correspondences of the musical trance experiences. The predominance of temporal parameters in the featured tendencies provides a compatible ground between sound and the brain/body mechanisms of ASC phenomenon with music in terms of perceptual qualities. While they are not suggested as the inducers of the trance states, they can be hypothesised as the sonic cues with a high potential to alter the conscious state because of their relation to auditory processing mechanisms. Nevertheless, it is also true that specific socio-cultural codes and specificities of contextual meanings related to the trance rituals are also observed not only in a variety of ritual settings but also in music-specific aspects, such as the verbal and motivic associations of melodies with the intentions behind the ritual, or the use of specific timbres to indicate the specific ritual.

The simultaneity of the psychoacoustic and socio-cultural aspects in association with musical trance suggests a via media between scholars who would stress one side to the exclusion of the other. The present study brings out the core ideas of each perspective and, I hope, makes a distinctive contribution by demonstrating these diverse yet complementary factors in musical trance phenomena. This intermediate standpoint is also reflected in the choice of the term ‘sonic signification’. One might question the precision of the term signification since it is often considered as including meaning and interpretation rather than the direct, quick cognitive responses with psychoacoustic foundations. While such a distinction in the levels of perception is beneficial in understanding the differential factors of any given phenomenon, it is also true that they are not independent of each other in the moment of experience. This problem of separating the biological foundations from the meaning-making processes and limiting the meaning to the socio-cultural verbal contexts is criticised in Paul Thibault’s unified theory of eco-social semiotics. According to Thibault, meaning-making also includes cognitive states, bodily experiences, and all types of percepts (that is, objects of perception), along with social phenomena, such as linguistic models or cultural notions. Therefore, meaning-making is an integrated activity in an eco-social system formed by three factors; the individual mental processing, the material environment, and the linguistic models of the socio-cultural domain in which the individual is situated. Thibault suggests that even though the language base meanings on the cultural level are essential parts of the entire system, ‘they have a secondary and derived status with respect to the activities in which they are made and in which they participate’.36 Nevertheless, the meaning emerges as a composite in the individual experience at the focal point of this eco-social model.

In this chapter, I have discussed the qualities of the music accompanying trance rituals as integrated parts of sonic significations with both psychoacoustic and socio-cultural traces. Both function in the experience and the meaning-making process of sounds played and heard during trance rituals. They are signified by the people (human cognition) who are the focus of this eco-social model. While psychoacoustic tendencies and socio-cultural codes are different in terms of the way that they involve the emergence of the overall signification (the former is bottom-up, the latter is top-down), the sonic signification is an amalgam derived from the interactions of the human mind with both means. In this more holistic context, the present study should be considered as an effort to bring out the observable patterns in this entire signification process concerning many sides. From this standpoint, what makes music such a unique companion to spiritual experiences is its temporality, its capacity to hold a variety of layers within unity and to carry them simultaneously into the very moment of experience.

Discography

|

1 |

D. Bernez [Performer], ‘Na Go De’ [Liner notes and recordings by Scott Kiehl]. On Akom: Art of Possession, Track Number 19 [CD] (Village Pulse VPU-1009, 2000). |

|

2 |

‘An Evening with the Flute Ensemble’ [Liner notes and recordings by Artur Simon]. On Berta—Waza, Bal Naggaro, Abangaran—Die Musik Der Berta Am Blauen Nil—Music of the Berta from the Blue Nile, Track Number 15 [CD], Museum Collection Berlin (WERGO—SM 17082, 2003). |

|

3 |

‘Bartha, the Winner’ [Liner notes and recordings by Artur Simon]. On Berta—Waza, Bal Naggaro, Abangaran—Die Musik Der Berta Am Blauen Nil—Music of the Berta from the Blue Nile, Track Number 14 [CD], Museum Collection Berlin (WERGO —SM 17082, 2003). |

|

4 |

‘The Bata Repertoire for Shango in Sakété: Oba Koso’ [Liner notes and recordings by Carol Hardy, compilation by Marcos Branda-Lacerda]. On The World’s Musical Traditions, Vol. 8: Yoruba Drums from Benin, West Africa, Track Number 7 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings 40440, 1996). |

|

5 |

Matsuhira Yuji [Screen name], ‘Bira Dance at Great Zimbabwe’, YouTube, 20 January 2013 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pbs80p4-nGM |

|

6 |

‘La Cérémonie Du Bobé’ [Produced by Caroline Bourgine]. On Congo: Cérémonie du Bobé, Track Number 2 [CD] (Ocora W 560010, 1991). |

|

7 |

‘Le Bobé S’est Rapproché’ [Produced by Caroline Bourgine]. On Congo: Cérémonie du Bobé, Track Number 3 [CD] (Ocora W 560010, 1991). |

|

8 |

‘Musique de Divination Diye’ [Liner notes and recordings by Simha Arom]. On Anthologie de la musique des Pygmées Aka = Musical anthology of the Aka Pygmies, Disc 2, Track Number 9 [CD] (Ocora C 560171/72, 2002). |

|

9 |

Foundation for Hausa Performing Arts, ‘Dodorido Koroso Dance Drama Segment 2 Bori Adept’, 8 January 2012 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hpjrw_VRW1Y |

|

10 |

‘Music for the Buma Dance’ [Liner notes and recordings by Simha Arom & Patrick Renaud]. On Cameroon: Baka Pygmy Music, Disc 1, Track Number 1, 10 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO, 1977). |

|

11 |

‘Le Jeune Eland (Nang Tzema Tzi)’ [Liner notes by Emmanuelle Olivier]. On Namibia: Songs of the Ju’hoansi Bushmen, Track Number 18 [CD] (Ocora C 560117, 1997). |

|

12 |

‘Oryx (Go’e Tzi)’ (1997) [Liner notes by Emmanuelle Olivier]. On Namibia: Songs of the Ju’hoansi Bushmen, Track Number 19 [CD] (Ocora 560117, 1997). |

|

13 |

Mtendeni Maulid Ensemble, ‘Dahala 3: Marihaba / Hua Maulana / Salat / Jalla Jalaluh / Khamsa Arkan / Man A’ala / Leo Mambo’ [Liner notes by Aïsha Schmitt]. On Zanzibara, Vol. 6—A Sufi Performance from Zanzibar, Track Number 3 [CD] (Buda Musique 860219, 2012). |

|

14 |

‘Hadra Song: “Al hamdou lillahAlgeria”’ [Liner notes and recordings by Pierre Augier]. On Algeria: Sahara - Music of Gourara Disc 1, Track Number 3 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO, 1975). |

|

15 |

‘Jinele: chant de divination’ [Liner notes by Jean L. Jenkins, Ralph Harrisson and Ragnar Johnson]. On Ethiopie: musiques vocales et instrumentales, Disc 2, Track Number 10 [CD] (Ocora C 580055/56, 1994). |

|

16 |

‘Būderbāla / Būḥāla’. On The Music Of Islām—Volume Six: Al-Maghrib, Gnāwa Music, Marrakesh, Morocco, Track Number 4 [CD] (Celestial Harmonies 13146-2, 1997). |

|

17 |

Matsuhira Yuji [Screen name], ‘The Mbira Ceremony’, YouTube, 18 May 2012 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OXBQbn6wZeQ |

|

18 |

‘Molimo Song of Devotion to the Forest’ [Liner notes and recordings by Colin Turnbull and Francis S. Chapman]. On Mbuti Pygmies of the Ituri Rainforest, Track Number 26 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings 40401, 1997). |

|

19 |

‘Molimo Song: Darkness Is Good’ [Liner notes and recordings by Colin Turnbull and Francis S. Chapman]. On Mbuti Pygmies of the Ituri Rainforest, Track Number 25 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings 40401, 1997). |

|

20 |

Gnawalux Brussels [Screen name], ‘Stambali 1—Gnawa Tunisie’, YouTube, 27 August 2008 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wK-UasuUtdo |

|

21 |

‘Tazenkharet’ [Liner notes and recordings by Finola Holiday & Geoffrey Holiday]. On Tuareg Music of the Southern Sahar, Disc 1, Track Number 13 [CD] (Ethnic Folkways Library FE 4470, 1960). |

|

22 |

‘Timgui’ [Liner notes and recordings by Charles Duvelle]. On Bariba—Bénin, Track Number 5 [CD] (Philips Music Group France 538721-2, 1999). |

|

23 |

Mwizenge Tembo [Screen name], ‘Vimbuza Dance Ritual Ceremony’, YouTube, 20 July 2008 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6wpsNQp1ci4 |

|

24 |

‘Alto Bung’o Horn (Kenya)’ [Compiled by Stephen Innocenzi]. On Africa, Music from the Nonesuch Explorer Series, Track Number 1 [CD] (Nonesuch Records 7559-79793-2, 2002). |

|

25 |

Ivo Biegman. [Screen name], ‘Zar ritual in Egypt’, YouTube, 19 May 2011 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YNiUc4W5Kzo&list=RDYNiUc4W5Kzo#t=517 |

|

26 |

‘Zar Omdurman’ [Liner notes and compilation by Peter Verney]. On Rough Guide to Sudan, Track Number 7 [CD]. (World Music Network—RGNET 1152, 2005). |

|

27 |

‘Danse, Bozok Semahi’ [Liner notes by Jean During and Jerome Cler]. On Turquie: Ceremonie du Djem Alevi (Turkey: Djem Alevi Ceremony), Track Number 12 [CD] (Ocora C 560125, 1998). |

|

28 |

kabultransit [Screen name]. ‘Kabul Transit—Zikr’, YouTube, 7 November 2007 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_BvSLgJSBBY |

|

29 |

‘Zikr’ [Liner notes by Jean During]. On Kurdistan: Zikr et chants soufis, Disc 2, Track Number 2 [CD] (Ocora C 560071/72, 1994). |

|

30 |

Iraqi Maqam [Screen name], ‘Dhikr Ceremony in Iraq’, YouTube, 1 January 2009 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yyrK-oAo3DM&list=PL5B186F663D6F3052&index=2 |

|

31 |

Iraqi Maqam [Screen name], ‘Qadiri Dhikr—God is Eternal’, YouTube, 8 December 2008 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lV52djNFcKk&index=1&list=PL5B186F663D6F3052 |

|

32 |

‘Zikr/ Du’a / Tekbir’ [Liner notes and recordings by Bernard Mauguin]. On Islamic Ritual from Kosovo, Track Number 2 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/ UNESCO-UNES08055, 1974). |

|

33 |

‘Islamic Ritual Zikr’ [Liner notes by Christian Poché, recordings by Jochen Wenzel]. On Syria: Islamic Ritual Zikr in Aleppo, Track Number 2 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO-UNES08013, 1975). |

|

34 |

‘Zikr’ [Liner notes by David Stevens]. On Turquie: Musique Soufi, Track Number 1 [CD] (Ocora C559017, 1987). |

|

35 |

‘Zikr-e Allah et percussions’ [Liner notes by Jean During]. On Kurdistan: Zikr et chants soufis, Disc 2, Track Number 1 [CD] (Ocora C 560071/72, 1994). |

|

36 |

H. Shakkûr & Ensemble Al-Kindî [Performer], ‘Meditation’ [Liner notes by Peter Pannke]. On Sufi Soul (Echos Du Paradis), Disc 1, Track Number 2 [CD]. (Network Medien—26.982, 1997). |

|

37 |

Muhammad Al Ashiq [Performer], ‘Qasida: Saluha Limadha’ [Liner notes by Andre Jouve and Christian Poche]. On Archives De La Musique Arabe Vol. 1, Track Number 2 [CD] (Ocora C 558678, 1987). |

|

38 |

Mobarak & Molabakhsh Nuri [Performer], ‘Qalandari Tune’. On Troubadours of Allah: Sufi Music from the Indus Valley, Disc 1, Track Number 2 [CD] (Wergo SM 16172, 1999). |

|

39 |

Yâr Mohammad [Performer], ‘Qalandari Tune (Khorasani)’ [Liner notes by Peter Pannke]. On Sufi Soul (Echos Du Paradis), Disc 2, Track Number 10 [CD] (Network Medien—26.982, 1997). |

|

40 |

‘Tamburah (Voice of the Lyre)’ [Liner notes and recordings by Dieter Christensen]. On Oman: Traditional Arts of the Sultanate of Oman, Track Number 7 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO-UNES08211, 1993). |

|

41 |

O. Y. Traibi [Performer], ‘Zar’ [Liner notes by Christian Poché, recordings by Jochen Wenzel]. On Yemen: Traditional Music of the North, Track Number 3 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO-UNES08004, 1978). |

|

42 |

Ozman Khaled [Screen name], ‘ZAAR Ceremony at Qeshm’, YouTube, 18 April 2016 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gifUSI1RFCQ |

|

43 |

‘Zikr’ [Liner notes and production by Jean During and Ted Levin]. On The Silk Road: A Musical Caravan, Disc 2, Track Number 19 [CD]. (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40438, 2002). |

|

44 |

Aznash Ensemble [Performer]. Konya Mystic Music Festival [Screen name], ‘Aznash Ensemble’, YouTube, 5 August 2013 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TiPqB4GNzT0&list=RDtx6dwa4u8Lg&index=11 |

|

45 |

Swiatoslaw Wojtkowiak [Screen name], ‘Chechen Female Zikr: Opening’, YouTube, 16 December 2010 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tx6dwa4u8Lg |

|

46 |

S. Aqmoldaev [Performer], ‘Kertolghau’ [Liner notes and production by Jean During and Ted Levin]. On The Silk Road: A Musical Caravan, Disc 2, Track Number 16 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40438, 2002). |

|

47 |

T. S. Qalebov and S. Tawarov [Performer], ‘Madh’ [Liner notes and production by Jean During and Ted Levin]. On The Silk Road: A Musical Caravan, Disc 2, Track Number 18 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40438, 2002). |

|

48 |

Supergnak [Screen name], ‘Le tour du monde en musique: Kazakhstan—Le kobyz du chaman’, YouTube, 14 January 2010 [online video recording], https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5M6DA5w6aCc |

|

49 |

‘Shod-i Uforash and Ufor-i Tezash: Dilbaram Shumo’ [Liner notes and recordings by Ted Levin]. On Bukhara: Musical Crossroads of Asia, Track Number 1 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40050, 1991). |

|

50 |

‘Cérémonie De Propitiation De Nag-Zhig’ [Liner notes and recording by Ricardo Canzio]. On Tibet: Traditions Rituelles Des Bonpos, Track Number 2 [CD] (Ocora C 580016, 1993). |

|

51 |

‘Shamanic Bear Session’ [Liner notes and recording by Henry Lecomte]. On Siberia, Vol. 1—Shamanic & Narrative Songs of Siberian Arctic, Track Number 12 [CD] (Buda Musique—925642, 1995). |

|

52 |

O. A. Njavan [Performer], ‘Song, Kkas Drum and Jampa Jingle Belt, Imitation of Kamlanie’ [Liner notes and recording by Henry Lecomte]. On Siberia, Vol. 6: Sakhalin—Vocal & Instrumental Music, Nivkh Ujl’ta, Track Number 8 [CD] (Buda Musique—927212, 1998). |

|

53 |

‘Chant Chamanique’ [Liner notes and recording by Henry Lecomte]. On Siberia, Vol. 5—Shamanic & Daily Songs from the Amur Basin, Track Number 8 [CD] (Buda Musique—926712, 1997). |

|

54 |

‘Chant Chamanique’ [Liner notes and recording by Henry Lecomte]. On Siberia, Vol. 5—Shamanic & Daily Songs from the Amur Basin, Track Number 27 [CD] (Buda Musique—926712, 1997). |

|

55 |

‘Pei-tou Liturgy (Great Bear Liturgy)’ [Produced by John Levy]. On Chinese Buddhist Music, Track Number 6 [CD] (Lyrichord—LLST 7222, 2004). |

|

56 |

‘Dai Hannya Tendoku E’ [Liner notes by Toshiro Kido and Pierre Landy]. On Japan: Shomyo Buddhist Ritual—Dai Hannya Ceremony, Track Number 1, 17:00–31:42 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO-UNES08036, 1975). |

|

57 |

‘Sinawi’ [Liner notes and recording by Kwon Oh Sung]. On Korea: Folkloric Instrumental Traditions, Vol. 1: Sinawi and Sanjo, Track Number 1 [CD] (JVC Ethnic Sound Series #25, JVC VID- 25020, 1988). |

|

58 |

O-Suwa-Daiko [Performer]. ‘Ama-No-Naru Tatsu-O Dai-Kagura’ [Liner notes by Iyori Takei]. On Japan: O-Suwa-Daiko Drums, Track Number 3 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO-UNES08030, 1978). |

|

59 |

‘Rimse’ [Liner notes and recording by Jean-Jacques Nattiez and Kazuyuki Tanimoto]. On Japan: Ainu Songs, Track Number 4 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO-UNES08047, 1980). |

|

60 |

M. K. Seo [Author and Recorder], ‘Tangak’. In the CD of the book Hanyang Kut: Korean Shaman Ritual Music from Seoul (Current Research in Ethnomusicology: Outstanding Dissertations), Track, Number 20, pp. 165, 171, and 194 (New York & London: Routledge, 2002). |

|

61 |

B. Salchak [Performer], ‘Kham [Shaman Ritual]’ [Liner notes and recording by Dina Oiun]. On Voices from the Distant Steppe, Track Number 16 [CD] (Real World Records—CDRW41, 1994). |

|

62 |

K. Yokoyama [Performer], ‘Ko-ku (Vacuity)’ [Liner notes by Akira Tamba]. On Japon, Kinshi Turata—Katsuya Yokoyama, Track Number 2 [CD] (Ocora C 558518 1994). |

|

63 |

V. G. Anastasija [Performer], ‘Vocals and Jajar Frame Drum: A Song for the Khololo Celebration’ [Liner notes and recording by Henry Lecomte]. On Siberia, Vol. 4 Kamtchatka: Dance Drums from Siberian Far East, Track Number 15 [CD] (Buda Musique—925982, 1994). |

|

64 |

‘Tus’ [Liner notes and recording by Jean-Jacques Nattiez and Kazuyuki Tanimoto]. On Japan: Ainu Songs, Track Number 10 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO-UNES08047, 1980). |

|

65 |

‘Upopo’ [Liner notes and recording by Jean-Jacques Nattiez and Kazuyuki Tanimoto]. On Japan: Ainu Songs, Track Number 2 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO-UNES08047, 1980). |

|

66 |

‘Smaon’ [Liner notes by John Schaefer and recording by David Parsons]. On The Music of Cambodia (Royal Court Music), Track Number 19 [CD] (Celestial Harmonies 13075-2, 1993). |

|

67 |

‘Beliatn Sentiyu Suite’ (excerpt) [Liner notes and recording by Philip Yampolsky]. On Music of Indonesia, Vol. 17: Kalimantan: Dayak Ritual and Festival Music, Track Number 14 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40444, 1998). |

|

68 |

P. Pargi Mina [Performer] (1984), ‘Devi Ambav ro dhak’ [Recording by David Roche]. On The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Vol. 5: South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent Audio, Track Number 13 [CD] (Garland Publishing, 2000). |

|

69 |

‘Buddhist Ritual Music and Chant in Honor of A-phyi’ (1976). [Recording by Mireille Helffer]. On The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Vol. 5: South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent Audio, Track Number 24 [CD] (Garland Publishing, 2000). |

|

70 |

‘Ritual Chanting (Ngāyung) of Mediums (to Rid the Settlement of Malign Forest Spirits) [Produced by Harold C. Conklin]. On Hanunóo Music from the Philippines, Side 1, Band 11 [LP] (Ethnic Folkways Library FE 4466, 1956). |

|

71 |

‘Châu Văn’ [Liner notes by Trần Văn Khê]. On Viêtnam Musique de Huê: Chants de Huê et Musique de Cour, Track Number 18 [CD] (Inedit—W 260073, 2005). |

|

72 |

‘Dabuih’ [Produced by Margaret J. Kartomi]. On The Music of Islam, Vol. 15: Muslim Music Of Indonesia, Aceh And West Sumatra, Disc 1, Track Number 16 [CD] (Celestial Harmonies 14232, 1998). |

|

73 |

‘Dzikir Samman: Allahu Allah’ [Produced by Philip Yampolsky]. On Music of Indonesia, Vol. 19: Music of Maluku: Halmahera, Buru, Kei, Track Number 17 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40446, 1999). |

|

74 |

‘Gamelan Salunding, Tenganan—Gending Sekar Gadung’ [Liner notes and recording by David Lewiston]. On Bali: Gamelan & Kecak, Track Number 5 [CD] (Elektra Nonesuch—9 79204-2, 1989). |

|

75 |

‘Musique des anciennes cérémonies religieuses avec une guru sibaso: Begu deleng/ Odak-odak/ Pertang-tang sabe/ Peseluken’ [Liner notes by Artur Simon]. On Sumatra: Musiques Des Batak Karo, Toba, Simalungun, Track Number 2 [CD] (Inedit—W 260061, 1995). |

|

76 |

‘Gondang “Pangelek-elek Ni Jujungan Ro”’ [Liner notes by Artur Simon]. On Sumatra: Musiques Des Batak Karo, Toba, Simalungun, Track Number 5 [CD] (Inedit—W 260061, 1995). |

|

77 |

‘Kecak From Blakiuh Near Mengwi’ [Liner notes by Wolfgang Hamm and Rika Reissler]. On Bali: A Suite of Tropical Music and Sound, Track Number 9 [CD] (World Network 35, 1995). |

|

78 |

‘Sekaha Ganda Sari, Bona—Kecak’ [Liner notes and recording by David Lewiston]. On Bali: Gamelan & Kecak, Track Number 8 [CD] (Elektra Nonesuch—9 79204-2, 1989). |

|

79 |

‘Kuda Kepang’. On The Ethnic Sampler 4, Track Number 25 [CD] (APM Music, Sonoton—SAS 107, 1995). |

|

80 |

‘Phléng khlom’ [Liner notes and recording by Jacques Brunet]. On Cambodia: Folk and Ceremonial Music, Track Number 12 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/ UNESCO-UNES08068, 1996). |

|

81 |

‘Pheng Phi Fa’ [Liner notes and recording by Jacques Brunet]. On Laos—Traditional Music Of The South, Track Number 1 [CD] (UNESCO—D 8042, 1992). |

|

82 |

‘Nanduni Pattu—Song to Bhadrakali’ [Liner notes and recordings by Rolf Killius]. On Ritual Music of Kerala, Track Number 5 [CD] (Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology—ARCE00028, 2008). |

|

83 |

‘Burmese “Pwe”’ [Liner notes and recording by the collection of La Meri]. On Exotic Dances, Track Number 4 [LP] (Folkways Records FP 52, 1950). |

|

84 |

‘A Healing Ceremony at Kg’ [Liner notes and compilation by Marina Roseman]. On Dream Songs and Healing Sounds in the Rainforests of Malaysia, Track Number 10 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40417, 1995). |

|

85 |

‘Piphat Mon: Spirit Dance’ [Liner notes by Andrew Shahriari]. On Silk, Spirits and Song—Music from North Thailand, Track Number 12 [CD] (Lyrichord—LYRCD 7451, 2006). |

|

86 |

‘Perdjuritan (Soldiers Dance)’ [Edited by Henry Cowell]. On Music of Indonesia, Track Number 7 [CD] (Folkways Records FE 4537, 1961). |

|

87 |

‘Invocation to the Goddess Yeshiki Mamo (Tantric Puja) Part II’ [Recording by Manfred Junius and P. C. Misra]. On The Lamas of The Nyingmapa Monastery of Dehra Dun—Tibetan Ritual, Track Number 2 [CD]. (UNESCO Collection of Traditional Music of the World Series, Auvidis – D 8034, 1991). |

|

88 |

‘Salai Jin, Pt. 2’ [Produced by Margaret J. Kartomi]. On Music of Indonesia: Maluku & North Maluku, Disc 1, Track Number 5 [CD] (Celestial Harmonies 14232, 2003). |

|

89 |

‘Bandina Devi ninna charana’ [Liner notes and recordings by Luisse Gunnel]. On Inde: Rythmes et Chants du Nord—Karnataka, Rythmes—Comptines, Chants dévotionnels, Track Number 43 [CD] (Buda Musique—1978542, 2001). |

|

90 |

‘Tovil (Drum Dance)’. On Sri Lanka, Nepal & Bhutan: Ritual, Festival, Masked Dance and Drum Traditions, Track Number 1 [CD] (Music of the Earth, 2015). |

|

91 |

‘Kohomba Kankariya (Dance Ritual)’. On Sri Lanka, Nepal & Bhutan: Ritual, Festival, Masked Dance and Drum Traditions, Track Number 2 [CD] (Music of the Earth, 2015). |

|

92 |

‘Baha Festival Dance’ [Liner notes and recordings by Deben Bhattacharya (1973)]. On Music of the Santal Tribe, Track Number 11 [CD] (ARC Music Productions EUCD2510, 2014). |

|

93 |

‘Uunu’ [Liner notes and recording by Hugo Zemp]. On Solomon Islands: Fataleka and Baegu Music from Malaita, Track Number 1 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/UNESCO-UNES08027, 1973). |

|

94 |

‘Kabu Kei Conua Group [Performer], ‘Yavulo, Yavulo, Vuni Maqo E Buto’ [Liner notes by Ad Linkels]. On Viti Levu: The Multicultural Heart of Fiji, Track Number 14 [CD] (Pan 2096, 2000). |

|

95 |

‘Seance Gisalo Song by Aiba with Weeping’ [Liner notes and recording by Steven Feld]. On Bosavi: Rainforest Music from Papua New Guinea, Disc Number 3, Track Number 4 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40487, 2001). |

|

96 |

‘Songs of the Spirits (Newet)—Lo, Torres’ [Liner notes by Alexandre François and Monika Stern]. On Music of Vanuatu: Celebrations and Mysteries, Track Number 39 [CD] (Inedit—W 260147, 2013). |

|

97 |

‘Alujà de Xangô Aira’ (2005). On Brésil: Les Eaux D’Oxala—Afro-Brazilian Ritual: Candomblé, Track Number 8 [CD] (Buda Musique 92576-2, 1973). |

|

98 |

‘Shipibo Song’ [Produced by Alan Jabbour and Mickey Hart]. On The Spirit Cries: Music of the Rain Forests of South America & The Caribbean, Track Number 12 [CD] (Rykodisc—RCD 10250, 1993). |

|

99 |

‘Selk’ham-Tierra del Fuego-Arrow Ordeal Chant’ [Produced by Alan Lazar]. On Anthology of Central and South American Indian Music, Disc 2, Track Number 14 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04542/FE 4542, 1975). |

|

100 |

‘Kumanti’ [Produced by Alan Jabbour and Mickey Hart]. On The Spirit Cries: Music of the Rain Forests of South America & The Caribbean, Track Number 20 [CD] (Rykodisc—RCD 10250, 1993). |

|

101 |

‘Warao Male Hoarotu Shaman’s Curing Song’ [Recorded by Dale A. Olsen]. On The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Vol. 2: South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean Audio CD, Track Number 3 [CD] (Garland Publishing, 1998). |

|

102 |

‘Curing Ritual’ [Produced by Alan Lazar]. On Anthology of Central and South American Indian Music, Disc 1, Track Number 19 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04542/FE 4542, 1975). |

|

103 |

‘Warao Male Wisiratu Shaman’s Curing Song’ [Recorded by Dale A. Olsen]. On The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Vol. 2: South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean Audio CD, Track Number 3 [CD] (Garland Publishing, 1998). |

|

104 |

‘Yanomamö Male Shaman’s Curing Song’ [Recorded by Pitts Collection]. On The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Vol. 2: South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean Audio CD, Track Number 1 [CD] (Garland Publishing, 1998). |

|

105 |

‘Yekuana Male Shaman’s Curing Song’ [Recorded by Walter Coppens]. On The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Vol. 2: South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean Audio CD, Track Number 2 [CD] (Garland Publishing, 1998). |

|

106 |

‘Healing Song’ [Produced by Alan Jabbour and Mickey Hart]. On The Spirit Cries: Music of the Rain Forests of South America & the Caribbean, Track Number 11 [CD] (Rykodisc—RCD 10250, 1993). |

|

107 |

‘Shango Cult: Annual Ceremony in a Rural Area’ [Liner notes and recordings by George Eaton Simpson]. On Cult Music of Trinidad, Track Number 7 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04478/FE 4478, 1961). |

|

108 |

‘Shamanistic Ritual: The Dance’ [Liner notes and recordings by Peter Kloos]. On The Maroni River Caribs of Surinam, Track Number 11 [CD] (Pan PANKCD4005, 1997). |

|

109 |

‘Winti Medley’ [Liner notes and recordings by Clifford Entes]. On Creole Music of Surinam, Track Number 8, 33:25’ [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04233/FE 4233, 1978). |

|

110 |

‘Abelagudahani’ [Produced by Alan Jabbour and Mickey Hart]. On The Spirit Cries: Music of the Rain Forests of South America & the Caribbean, Track Number 1 [CD] (Rykodisc—RCD 10250, 1993). |

|

111 |

Gropo Laka [Performer], ‘Danca de tambor pulaya / Pulaya Drum Dance’ [Liner notes and production by Sten Sandahl]. On Music from Honduras, Disc 1, Track Number 3 [CD] (Caprice Records CAP 21632, 2000). |

|

112 |

‘Salve’ [Recorded and produced by Isidro Bobadilla and Morton Marks]. On Afro-Dominican Music from San Cristobal, Dominican Republic, Track Number 3 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recording/Folkways Records FW04285/FE 4285, 1983). |

|

113 |

‘Kumina “Bailo”’ [Recorded and produced by Edward P.G. Seaga]. On Folk Music of Jamaica, Track Number 4 [CD] (Folkways Records FW04453/FE 4453, 1956). |

|

114 |

Jo Leh [Recorded and produced by Kenneth M. Bilby]. On Drums of Defiance: Maroon Music from the Earliest Free Black Communities of Jamaica, Track Number 14 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40412, 1992). |

|

115 |

‘Vodoun Dance (Three Vodoun Drums)’ [Liner notes and recordings by Harold Courlander]. On Music of Haiti: Vol. 2, Drums of Haiti, Track Number 1 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04403/FE 4403, 1950). |

|

116 |

‘Petro Dance (Two Drums)’. On Music of Haiti: Vol. 2, Drums of Haiti, Track Number 5 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04403/FE 4403, 1950). |

|

117 |

‘Bear Dance’ [Produced by Gertrude Prokosch Kurath]. On Songs and Dances of the Great Lakes Indians, Disc 1, Track Number 7 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04003/FE 4003, 1956). |

|

118 |

‘Peyote Song: First Song Cycle’ [Produced by Michael Asch]. On Anthology of North American Indian and Eskimo Music, Disc 1, Track Number 13 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04541/FE 4541, 1973). |

|

119 |

‘Peyote Song’ [Produced by John Bierhorst]. On Cry from the Earth: Music of the North American Indians, Disc 1, Track Number 31 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW37777/FA 37777, 1979). |

|

120 |

‘Crown Dance’ [Produced by Charlotte Heth and Terence Winch]. On Creation’s Journey: Native American Music, Track Number 4 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings SFW40410, 1994). |

|

121 |

‘Drum Dance’ [Produced by John Bierhorst]. On Cry from the Earth: Music of the North American Indians, Disc 1, Track Number 12 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW37777/FA 37777, 1979). |

|

122 |

Peter Webster [Performer], ‘Medicine Man Song’ [Liner notes and production by Ida Halpern]. On Nootka Indian Music of the Pacific North West Coast, Disc 1, Track Number 4 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04524/FE 4524, 1974). |

|

123 |

‘Huichol—Peyote Dance’ [Produced by Henrietta Yurchenco]. On Indian Music of Mexico, Track Number 9 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04413/FE 4413, 1952). |

|

124 |

‘Yaqui—Deer Dance’ [Produced by Henrietta Yurchenco]. On Indian Music of Mexico, Track Number 8 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04413/FE 4413, 1952). |

|

125 |

‘Wolf Dance’ [Liner notes and production by Ida Halpern]. On Nootka Indian Music of the Pacific North West Coast, Disc 2, Track Number 2 [CD] (Smithsonian Folkways Recordings/Folkways Records FW04524/FE 4524, 1974). |

1 Graham Nash, ‘And So It Goes’, Wild Tiles (Atlantic Records, 1974).

2 William James, Varieties of Religious Experience A Study in Human Nature (New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1902; repr. London and New York: Routledge, 2002), p. 295.

3 Werner Heisenberg, Physics and Philosophy, The Revolution in Modern Science (New York: Harper, 1958), p. 83.

4 Hilary Lawson, ‘21st Century Metaphysics: Leaving Fantasy Behind’, Institute of Art and Ideas News, 23 January 2023, https://iai.tv/articles/21st-century-metaphysics-leaving-fantasy-behind-auid-2367

5 John Horgan, ‘What Thomas Kuhn Really Thought about Scientific “Truth”’, Scientific American, 23 May 2012, https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/what-thomas-kuhn-really-thought-about-scientific-truth

6 Robert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance: An Inquiry into Values (London: Vintage, 1974).

7 Dynamic Quality serves as the monistic, fundamental, and undefined reference in the Metaphysics of Quality (MOQ). Therefore, it is capitalized to denote its significance in the primary texts. On the other hand, static quality refers to definable patterns within MOQ, holding a secondary status compared to Dynamic Quality, and thus is not capitalized.

8 Ibid., p. 294.

9 Robert M. Pirsig, Lila; An Inquiry into Morals (New York: Bantam Books, 1991), p. 121.

10 Robert M. Pirsig, On Quality: An Inquiry into Excellence: Unpublished and Selected Writings, ed. by Wendy K. Pirsig (New York: HarperCollins, 2022), p. 104.

11 Arnold M. Ludwig, ‘Altered States of Consciousness’, Arch Gen Psychiatry 15.3 (1966), 225–34.

12 Marcus E. Raichle and Abraham Z. Snyder, ‘A Default Mode of Brain Function: A Brief History of an Evolving Idea’, NeuroImage 37 (2007), 1083–90.

13 Carhart-Harris et al., ‘The Entropic Brain: A Theory of Conscious States Informed by Neuroimaging’, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8 (2014), 20.

14 Ibid., p. 20.

15 Judith Becker, Deep Listeners Music, Emotion and Trancing (Bloomington and Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Press, 2004), p. 56.

16 Ibid., pp. 51–54; Gilbert Rouget, Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations between Music and Possession, trans. by B. Biebuyck (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1985), pp. 10–11.

17 Rodney Needham, ‘Percussion and Transition’, Man 2.4 (1967), 606–14.

18 Andrew Neher, ‘Auditory Driving Observed with Scalp Electrodes in Normal Subjects’, Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology 13.3 (1961), 449–51.

19 Melinda C. Maxfield, ‘Effects of Rhythmic Drumming on EEG and Subjective Experience’ (unpublished doctoral dissertation, Institute of Transpersonal Psychology, 1990), https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/effects-rhythmic-drumming-on-eeg-subjective/docview/303885457/se-2

20 Jörg Fachner, ‘Time Is the Key: Music and Altered States of Consciousness’, in Altering Consciousness: A Multidisciplinary Perspective, ed. by Etzel Cardeña and Michael Winkelman, 2 vols (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2011), I, 355–76 (at 367).

21 Tina L. Huang, and Christine Charyton, ‘A Comprehensive Review of the Psychological Effects of Brainwave Entrainment’, Alternative Therapies 14.5 (2008), 38–50.

22 Gilbert Rouget, Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations between Music and Possession, trans. by Brunhilde Biebuyck (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1985), p. 175.

23 Steven Brown and Joseph Jordania, ‘Universals in the World’s Musics’, Psychology of Music 41.2 (2011), 240–41.

24 Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, ed. by Bruno Nettl, Ruth M. Stone, James Porter, and Timothy Rice, 10 vols (New York: Routledge, 1998–2002).

25 Bob Snyder, Music and Memory: An Introduction (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2001), pp. 12–15.

26 Diana Deutsch, ‘Grouping Mechanisms in Music’, in The Psychology of Music, ed. by Diana Deutsch (San Diego, CA: Elsevier, 2013), pp. 183–248.

27 John M. Ortiz, The Tao of Music: Sound Psychology Using Music to Change Your Life (Boston, MA: Weiser Books, 1987), p. 275.

28 W. Jay Dowling and Dane L. Harwood, Music Cognition (Orlando, FL: Academic Press, 1986), p. 152. For further information on the relationship between the melodic structures and the trance specific ritual context, see Dale A. Olsen, ‘Shamanism, Music and Healing in Two Contrasting South American Cultural Areas’, in The Oxford Handbook of Medical Ethnomusicology, ed. by Benjamin D. Koen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), pp. 343–46.

29 Author-transcribed melodies without tuning system specifications. The transcriptions provide reductive representations of the original melodies, excluding spectral and temporal details, with the sole purpose of demonstrating contours. For more detailed renditions, please refer to the recordings cited in the discography at the end of this chapter.

30 Alongside Neher and Needham’s previously cited experimental studies on drumming and altered states of consciousness, also see Peter Michael Hamel, Through Music to the Self, trans. by P. Lemesuer (Shaftesbury: Element Books, 1978), pp. 76–79.

31 Daniel J. Cameron, Jocelyn Bentley, and Jessica A. Grahn, ‘Cross-Cultural Influences on Rhythm Processing: Reproduction, Discrimination, and Beat Tapping’, Frontiers in Psychology 6 (2015), 366.

32 Michael Tenzer, ‘A Cross-Cultural Topology of Musical Time: Afterword to the Present Book and to Analytical Studies in World Music (2006)’, in Analytical and Cross-Cultural Studies in World Music, ed. by Michael Tenzer and John Roeder (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

33 Sukanya Sarbadhikary, ‘Hearing the Transcendental Place: Sound, Spirituality and Sensuality in the Musical Practices of an Indian Devotional Order’, in Music and Transcendence, ed. by Ferdia J. Stone-Davis (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), pp. 23–34 (at 26).

34 Sean Williams, ‘Buddhism and Music’, in Experiencing Music in World Religions, ed. by Guy. L. Beck (Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2006), pp. 169–89 (at 186).

35 Deutsch, The Psychology of Music, p. 213.

36 Paul Thibault, Brain, Mind, and the Signifying Body (New York: Continuum, 2004), p. 3