1. A Hero’s Many Worlds

The Swahili Liyongo Epic and

World Literature

©2025 Clarissa Vierke, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0405.01

Introduction

The most reputed hero of the East African coast is Fumo Liyongo. Stories and songs attributed to this invincible warrior-poet are the most ancient Swahili texts for which we have evidence. But such stories and songs are not merely relics of the past. These oral traditions have been re-adapted over and over again, and have found their way into handwritten manuscripts, school- and children’s books, stage performances, and YouTube videos. My aim in this chapter is to focus on the changing form of the ramified Liyongo tradition and the worlds it has generated. I will use this research to question the narrow notions of text and textual circulation that have hitherto dominated discussions of world literature.1

Oral Literature and the ‘Narrow Church’ of World Literature

More than the sum of all the literatures in the world, the term ‘world literature’—as manifold as its definitions might have been—has consistently been used to evoke literature’s existential gravitas. For Annette Werberger, world literature is a literature that belongs to all humankind, and endures over time because it deals with fundamental human questions of life and addresses all of humanity. Therefore, Werberger goes on to argue, all literature, including oral literature, aspires to be world literature.2 Within the field of world literature, though, with its modernist bias and overwhelming focus on a more narrowly defined notion of written literature in a few Western languages, this has actually become an exceptional position. Since the 1960s, oral literature has increasingly been written out of academic literary studies.3

While the field of world literature seems all-embracing and open—as the term itself implies a purview of the whole world—there has been a growing call for the inclusion of languages from beyond the West and of genres other than the historically recent novel.4 This entails exploring a multitude of dynamic historical and geographic worlds from the perspective of the longue durée, and also reopens discussions of what literature is. As Galin Tihanov underlines:

There is today still an unresolved tension in the way we approach world literature in that our modern understanding of it has become too secular and too determined by attention exclusively to the written form they have assumed. This is wanting on two counts: first, it excludes huge verbal masses of the premodern epochs, and secondly, it impedes efforts to capture the pluralism of world literature beyond a Eurocentric vision.5

Arguing for productively exploring the ‘broad church’ of world literature, i.e. its full thematic and disciplinary breadth, Tihanov urges us to consider various modi existendi of world literature, drawing ‘on the early impulses of engagement with orality […] in collaboration with ethnology, folkloristics and performance studies, in order to situate world literature in a wider cultural-anthropological context and a veritable longue durée’.6 Tihanov refers to Goethe’s broad notion of world literature which goes beyond a categorization into oral and written forms and rather insists on ‘verbal creativity’ in total and ‘as a process rather than artefact that is frozen in time through its commitment to script’.7

African literature, so famously rich in oral traditions—not merely of the past—has so far been explored very little in challenging this ‘narrow church’.8 The scholarly turn to the paradigm of globalization and the focus on transcultural identities have placed great emphasis on contemporary prose writing from the African diaspora. Works by the latest generation of the so-called Afropolitans, like Chimamanda Adichie’s Americanah or Taye Selasi’s Ghana Must Go, which have received global attention, have also partly fed into the discussion of world literature.9 Highlighting Africanness and drawing on Black consciousness rhetoric with a cosmopolitan attitude, both the authors’ biographies and their narratives suggest an emancipation from the essentializing narrative of Africa as disconnected from the rest of the world. Nonetheless, Western literary institutions, Western readership, and the book industry and its preferred genre (the novel)—typically in English, sometimes in French or Portuguese—have remained the point of reference for measuring global reach. The more ‘worldly’ African literature becomes, the more scholars relegate African languages and their variety of literary modi existendi to the background.10

In the 1990s, along similar lines, Karin Barber criticized the postcolonial focus on ‘writing back’, a focus that paradoxically reproduces the colonial fixation on a Western centre as well as relegating African-language literatures to a primordial past. This temporal divide creates a dichotomy between modern literature ‘writing back’ in the former colonial languages, on the one hand, and unchanging ‘traditional literature’, fundamentally oral, on the other hand.11 This postcolonial echo of the great divide between oral and written not only fatally associated writing with literary value, but also prevented a serious exploration of oral literature, which was downplayed as the ‘precursor and background, out of which modern anglophone written literature somehow emerged or grew’.12 Equally fatally, the oral became an unquestioned, but also celebrated sign of ‘African cultural authenticity’ in the novel itself, beyond critical scrutiny and encompassing a wide range of stylistic phenomena, from the use of dialogue to idiomatic speech and proverbs, as well as the recourse to oral tales.

In this chapter, I concentrate on the circulation and, consequently, adaptation across media of the most renowned heroic epic tradition on the Swahili coast, namely the tales and songs of Fumo Liyongo. I find inspiration in perspectives that cut across normative dichotomies of orality and written-ness, popular and highbrow literature. Liz Gunner, for example, has framed the journey of the West African Sunjata epic through Alexander Beecroft’s notion of literary ecologies with a similar double optic of circulation and media adaptation.13 For Beecroft, ecology, unlike the economics-derived metaphors of the field of world literature, offers a paradigm that can encompass more complex interactions between the distinct and various influences (including religion, politics, media, etc.) on the niches in which literatures survive. Since one of Beecroft’s major concerns is to go beyond tight notions of European modernity as the measure of literature, he opts for a practice-oriented definition of literature, which emerges in practices of reception and is closely tied to notions of language and political identity.14 As a result, his approach also invites oral literature and manuscript cultures into the debates of world literature.

Already in the twentieth century, scholarship on epic traditions, which both Liz Gunner and I focus on, played an important role in rehabilitating orality at the core of the Western canon, starting from the fundamentally oral nature of Homer’s epics. These debates questioned the dichotomy of orality and writing and highlight the oral culture of the West. Although they have hardly featured in recent debates about world literature, they did foster great comparative scholarship on the orality of the African epic, particularly in the 1980s (against Ruth Finnegan’s claim that there was no epic in Africa, an assertion based largely on criteria derived from writing cultures).15

So far, the Fumo Liyongo tradition—fragmented as it is across multiple genres, thereby seriously calling textual boundaries into question—has not been taken much into consideration in the debate on the epic in Africa. Its fuzziness and amorphousness—where does the text start? Where does it end?—is one of the reasons why I find it such an interesting case study, since it urges us all the more to critically reconsider the (normative) notions of textual boundaries derived from the printed book.

In seeking to identify recurrent motifs in discussions of world literature, Dieter Lamping speaks of the intertextual ‘dialogues’ that eminent texts create, since their motifs and references recur in other texts, so that world literature can be considered as a continuous network.16 One can take Lamping’s formulation, extending its remit (which largely embraces the novel) in order to shift the emphasis to literary resonances across the lines that usually demarcate genres, media and regions, as this essay does, decentering Europe in the process. One can also use it for a layered and multiple literary history that takes into account not only bouts of forgetting, but also the capacity of a text to live on in various forms.

Such recurrence is also emphasized in the inspiring nineteenth-century Russian school of historical poetics, pioneered by the Russian literary scholar Alexander Veselovsky, recently promoted by Boris Maslov in his inclusive, non-canonical study of ‘world poetry’.17 Historical poetics implies an ethnographic view of the longue durée that also involves a consideration of popular culture or folklore, and a literary history that is not teleological but involves constellations of ‘non-synchronous elements’ yet also allows for the sudden resurfacing of seemingly forgotten images and forms. As I will show, the literary history of Liyongo is not unilinear. Firstly, writing did not simply replace orality. Secondly, the Liyongo story is not one unified text and did not follow one singular path of monodirectional change. For instance, while episodes of his adventures were increasingly streamlined into a multitude of separate narratives, poetic songs found their way into manuscripts in Arabic script, before being largely forgotten. Only much later, in the twenty-first century, did they reappear in new forms as part of staged storytelling and digital renderings. Before turning to his verbal art, in the following, I will briefly introduce the protagonist, Fumo Liyongo.

The Fumo Liyongo Saga

Fumo Liyongo is the classical superhero from the East African coast: he makes the impossible come true and proves himself in many daunting adventures that are the core of a number of oral traditions on the East Africa coast. Having been deprived of the throne of the sultanate of Pate—the most important city-state in northern Kenya until the eighteenth century—by his half-brother Daudi Mringwari, he escapes all attacks ventured against him. For instance, when his half-brother Mringwari hatches a plot to shoot him dead by inviting him to climb a palm tree to collect the best coconuts for a feast, Fumo Liyongo sees through the trap, takes his bow and arrow, and shoots the coconuts down instead of climbing on the tree. In another episode, he escapes a dungeon by using a file his mother had baked into a bread loaf and smuggled into prison.

Like a typical epic hero, Fumo Liyongo is believed to be a historical character. However, the dating of his life has frequently been a point of intense discussion among folklorists and historians. While a few scholars, relying on oral sources and local Swahili and Arabic chronicles, have dated Liyongo’s life to a period before the thirteenth century, several historians situate him in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.18 Given these diverse suggestions, the only safe claim is that the world emerging from the ancient Liyongo narrative is one that predates the eighteenth century. For the historian Randall Pouwels, the Liyongo narrative and songs reflect a fundamental transition of power in the region: power moved from clans in the Tana delta, like Liyongo’s Bauri clan, to new elites on the islands of Pate, and later Lamu. While the former—perfectly embodied by Fumo Liyongo—adhered to cultural practices influenced by Indian Ocean connections but mostly from the African mainland, like beliefs in spirits, cognatic patterns of inheritance, shifting agriculture, and oral poetry traditions, the latter—embodied by Liyongo’s half-brother Mringwari—introduced more ‘literate Shari’a based rules favouring patrilineage’.19 The Liyongo texts echo the beginning of what becomes a wave of ‘Arabization’ reaching the coast from across the Indian Ocean, changing older rituals, legal practices, and literary preferences as Islamic hagiographic poetry in Swahili became more important.

The Liyongo tradition is not one fixed and definable text but refers to a variety of texts. There are oral Liyongo tumbuizo songs, which are the oldest Swahili poems of which we have evidence, predating the eighteenth century. Rather than conveying a plot-driven narrative, this dance poetry is polyphonic and seems to be only loosely connected to the overall Liyongo narrative. The songs were most probably interspersed between prose adventure episodes like the ones just mentioned, and probably formed part of dance rituals and poetic competitions on the northern Swahili coast. While the songs survived merely in writing from the nineteenth century onwards, since Islamic poetry partly obliterated older song traditions, the narrative episodes have been preserved orally: Lamu elders still narrate Liyongo stories. These were streamlined into more coherent, written narrative poems or prose tales as early as the twentieth century; more recently, they have found a new life of secondary orality on the internet. In the following, we will navigate the shifting dynamics of the Liyongo epic and its making of changing worlds.

World-making in Fumo Liyongo’s Ancient Tumbuizo

Pijiyani p’embe, vigomamle na t’owazi

T’eze na Mbwasho na K’undazi

Pija muwiwa k’umbuke mwana wa shangazi

Yu wapi simba ezi li kana mtembezi

Fumo wa Shanga, sikiya, shamba, mitaa pwani

Fumo wa Shanga, chambiya Watwa fungiyani?

Fumo achamba mfungeni

Kikaze miyo nguo nawapa za kitwani

Strike for me the horns, the long drums, and the cymbals,

so that I may dance with Mbwasho and K’undazi.

Strike, you who owe a debt (of Kikowa), so that I may remember (my) cousin.

Where is the mighty lion? He is like an inveterate wanderer!

Fumo of Shanga, reckon well, (roams) the land and the coastal areas.

Fumo of Shanga asked the Watwa people: ‘Why are you putting me in fetters?’

Fumo (Mringwari) ordered: ‘Tie him up!’20

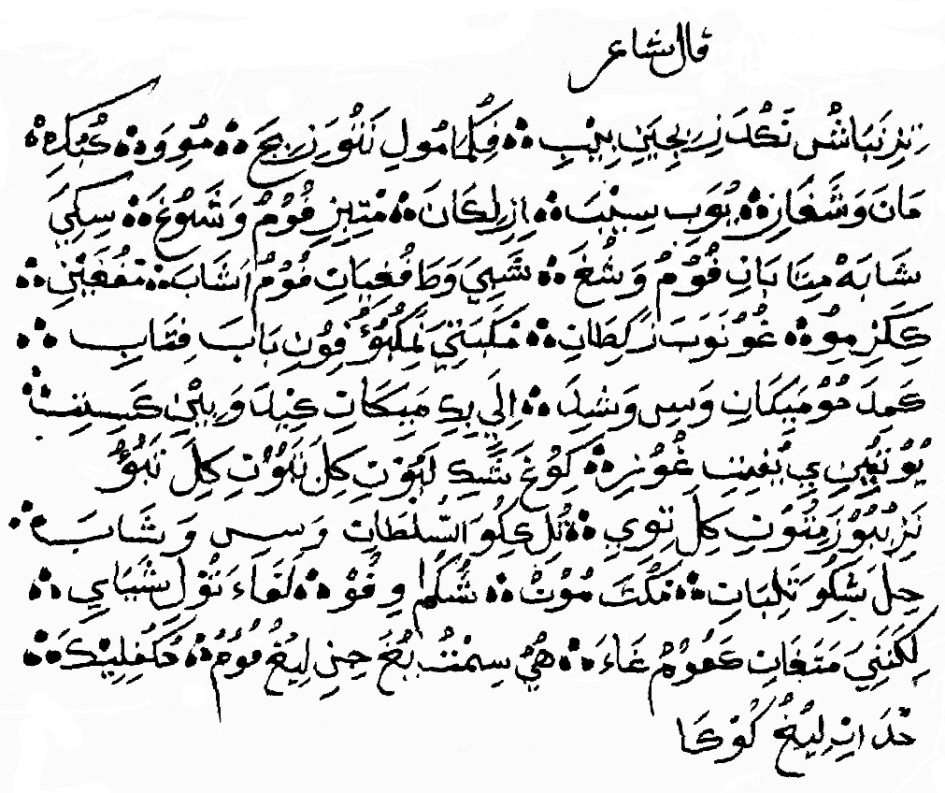

These are the first lines of the Utumbuizo wa Kikowa (‘The Utumbuizo of the Kikowa Meal’). The kikowa feast refers to the cultural practice of an opulent banquet whose guests take turns providing the food. In this instance, Liyongo shoots coconuts down from a palm tree to avoid his murder.21 Rather than reporting the incident, the poem or song (both terms can be used interchangeably to refer to utumbuizo) stages several exclamatory voices, relying on bipartite or tripartite verses. These voices include a dancing narrator (possibly Liyongo?); Liyongo’s rival, Mringwari; and a third-person account of Liyongo by the Fumo of Shanga, who roams the land and accuses the Watwa, a subgroup of the Oromo, of imprisoning him on Mringwari’s behalf. An impression of opacity and ‘strangeness’ is created, as often found in other in oral traditions, which literary history, puzzled by the phenomenon, has tended to downplay or neglect, as Chamberlin notes.22 The Utumbuizo wa Kikowa, like the other Liyongo poems of this period, is hardly remembered in the Lamu archipelago of northern Kenya where the poems once flourished. This oblivion is not a recent phenomenon, however. Already by the end of the nineteenth century, they seem to have become less frequent, since important local scholars, like the erudite Rashid bin Abdallah, who scribed the poem below (see Figure 1.1), felt the need to preserve them. As a result, the oral songs have survived only in written form in Arabic script manuscripts.

The specific genre with which the Fumo Liyongo poems are associated, the utumbuizo, is not in use anymore either. Our idea of its rhythm and how it was performed is vague, which is a pity, since in contrast to later written poetic genres the utumbuizo was primarily an oral poem, meant to be performed. Unlike the later genre of the utenzi, whose audible elements, like rhythm, metre, and rhyme, were written down in carefully arranged script, the representation of utumbuizo verse is mostly erratic. In ‘The Utumbuizo of the Kikowa Meal’, for instance, the poetic lines do not correspond to manuscript lines (Fig. 1.1)—the first manuscript line ends with kumbuka ‘remember’ in the middle of the verse—and the caesuras (the three inverted hearts) are but a random decoration, inserted even in the middle of metrical units, rather than a rhythmic guideline. Tumbuizo depended largely on embodied practices of performance and memorized knowledge and was not committed to paper: its metre was not founded on a strict syllable count (represented by letters in the utenzi), but on the performer’s breath. The polyphonic nature of its lines has made scholars wonder how to arrange them on the page.

Fig. 1.1 The Utumbuizo wa Kikowa in the handwriting of Rashid bin Abdallah (MS 47754, Taylor Collection, SOAS). The first verses of the poem are reprinted above.

We know little about the performance, either. In some sources, tumbuizo are associated with a dance genre, the gungu, which used to be widespread all along the coast, from what is now northern Kenya to northern Mozambique. The tumbuizo might have existed in a different form in each city-state, and it seems to have fallen out of fashion towards the end of the nineteenth century. While in Mombasa it was associated with the New Year’s celebration according to the Persian calendar,23 Steere observed a gungu of a different form in Zanzibar in the mid-nineteenth century: ‘It is the custom to meet at about ten or eleven at night and dance until day-break. The men and slave women dance, the ladies sit a little retired and look on. […] The first figure is danced by a single couple, the second by two couples’.24 The French missionary Charles Sacleux describes the tumbuizo as serene and festive, performed ‘on solemn occasions’ such as weddings, to which some of the songs attributed to Liyongo also make reference.25 Poems themselves also often evoke a context of dance and music. The Utumbuizo wa Kikowa, for example, does not begin with the formulaic imperative to bring writing utensils, so conventionally evoked in later tenzi, but to beat cymbals (t’owazi) and drums (vigomamle) to set the rhythm for the dance.

The language quoted in Figure 1.1 is boastful and provocative. Liyongo is referred to as a mighty lion, reminiscent of African praise poetry traditions. In the Swahili context, this kind of language is typically found in verbal duels, kujibizana, which have lived on in many forms—from socialist ngonjera poetry to contemporary hip-hop battles—and are also connected to the gungu tradition of the northern parts of the coast. According to one fragmentary historical source, one of the few Swahili descriptions mentioning poetic practice prior to the twentieth century, the gungu (perhaps derived from Persian gong), referred to a night-long ritualized poetic competition, possibly also involving dance. At the beginning, the shaha, the master poet, ‘ties up an animal’. In other words, he composes an enigmatic poem, which the poets must ‘untie’ in order to solve the riddle. The one who ‘unties it’ is the winner, and is formally recognized as shaha, a highly prestigious social title.26 It seems likely that Liyongo tumbuizo also formed part of such gungu performances, since they not only make reference to gungu but also share its highly metaphorical language—calling on the poetic rivals to decode its meaning—as well as an often-boastful tone of self-praise.

These observations already question both the boundaries of the literary text—since it formed part of a larger ritualized performance with musical accompaniment—as well as the notion of writing. Even writing as such did not turn the Liyongo poems, which still depended on oral performance, into written literature. As I explore in the following sections, the worlds emerging from the Liyongo songs are also not easily classifiable, either.

The Shifting Worlds of Fumo Liyongo Texts

The cultural memory of Liyongo, like that of other epics, is tied to a specific geography. The world of the ancient Fumo Liyongo tumbuizo is that of the northern Swahili coast: the Tana and Ozi deltas just opposite the Lamu archipelago with the ancient Swahili city-state of Pate. The pre-eighteenth-century northern East African coast has a double orientation, towards both the sea and the mainland, which is also reflected in the tumbuizo. Involved in Indian Ocean trade through commercial hubs like Kilwa and Pate since the first millennium CE, the Swahili islands also depended economically on Swahili clans living closely together with neighbouring ethnic groups on the mainland. These Swahili clans engaged in shifting cultivation as well as exchange with hunters and, above all, Cushitic pastoralists, who complemented the maritime economy of fishing and long-distance trade in goods. According to the pioneering scholar of Swahili folklore Alice Werner, local traditions regularly described Fumo Liyongo as being of Persian descent, from a lineage belonging to the early Swahili culture of far-reaching Indian Ocean trade originating mostly in Shiraz (Persia). At the same time, his story and songs also characterize Fumo Liyongo as being uniquely part of the ethnic and cultural contact zone of the African coast.27

The Tana delta is an area of ‘overlapping cultures’, as Alice Werner describes it. She travelled to the area at the beginning of the twentieth century and was taken to Liyongo’s grave in Kipini in 1913.28 Liyongo, she was told, came from the town of Shaka (sometimes also spelled ‘Shagga’ or ‘Shanga’), probably etymologically related to Shungwaya, another name for the region and the mythical homeland of the Swahili, as well as other culturally and linguistically related Bantu-speaking ethnic groups, like the Pokomo. The Pokomo intermarried with and adopted cultural practices such as hunting from their Cushitic-speaking neighbours, for example the Dahalo, as well as Oromo-speaking groups, like the Watwa (mentioned above in the Utumbuizo wa Kikowa).29 Not only are there Pokomo and Dahalo oral traditions about Liyongo (see below)—in which Liyongo is portrayed as a slave-raiding tyrant ruling over the region of the Tana delta—but we also find recurrent references to other ethnic groups in the Swahili tumbuizo. In the Gungu la Mnara Mp’ambe (Gungu of the Dignified Lady), the Oromo, who in the seventeenth century came from what is now Ethiopia, are portrayed as invading warriors: ‘The Galla came with weapons, with weapons determined to start a fight’ (Kuyiye mgala na mata/na mata uyiye kutaka kuteta).30 In the Utumbuizo wa Kumwongoa Mtoto (Lullaby), Liyongo is depicted as ‘dancing with the Watwa’ (akateza Liyongo na Watwa).31

The world emerging from many of these poems is that of the cultural and natural environment of the northeast African coast, commonly referred to as the nyika ‘bush’ or ‘wilderness’, constructed over time as being inhabited by evil spirits and in opposition to the distinctive Swahili urban culture portrayed in later poetry. The powerful Fumo Liyongo is usually not described as an urban dweller residing in the typical Swahili stone house.32 Liyongo is instead portrayed as a warrior, ‘an inveterate wanderer’ in the bush, as the Utumbuizo wa Kikowa calls him. This characterization is impossible to imagine from a later vantage point that associates Swahili culture almost exclusively with an urban environment of cultural refinement, in opposition to the ushenzi ‘primitivism’ of the nyika.

In the Utumbuizo wa Kumwawia Liyongo (The Shining of the Moon on Liyongo), Liyongo is ‘the mighty leopard’, or a hunter praising his bow and arrow in the Utumbuizo wa Uta (Bow Song): ‘Let me praise my bow, made from the supple twig of the ebony tree’.33 The bow is ‘his father and mother who parented him’ in the Utumbuizo wa Ukumbusho (Remembering Past Deeds).34 Liyongo hunts an ‘elephant, whose ear is like an uteyo basket’, and ‘a deer and swift antelopes’.35 In the Utumbuizo wa Kumwongoa Mtoto (Lullaby), he is depicted evading every attack, riding ‘on a leopard’, eating wild nuts and fruits in the bush as well as drinking palm wine.36 This was a common Pokomo practice, considered haram by later Islamic scholars, whose voices becomes more dominant in the whole area from the eighteenth century onwards.

While the Liyongo tumbuizo are much more oriented towards the African interior than all later Swahili poetry, they do not merely conjure up a world of overlapping cultural influences in the East African mainland. References to the wider Indian Ocean and its far-reaching networks already figure in some of the Liyongo tumbuizo. In the following poem, Utumbuizo wa Liyongo Harusini (The Poem of Liyongo at a Wedding)—according to Jan Knappert, ‘the oldest known dance song in Swahili and perhaps any Bantu language’—the guests at Liyongo’s sister’s wedding are asked to adorn themselves with fine attire and scents.37

Mujipake na twibu hiyari ♦ yalotuwa kwa zema ziungo

Choshi ni maambari na udi ♦ fukizani nguo ziso ongo

Fukizani nguo za hariri ♦ na zisutu zisizo zitango

Pachori na zafarani ♦ na zabadi twahara ya fungo

Na zito za karafuu ♦ tuliyani musitiwe t›ungo

Na itiri na kafuri haya ♦ ndiyo mwiso wa changu kiungo

Put on choice scents made of the best ingredients;

treat your spotless clothes with incense of ambergris and aloewood;

treat your silken garments and finely made zisutu clothes

with patchouli and saffron and pure civet musk,

and grind them (all together) with clove buds, lest people criticize you;

and (finally) add perfume and fine camphor to complete the ingredients.

In this poem, Indian Ocean connections are evoked through precious goods from afar: fruits, scents, and clothes (set in bold). The guests are asked to put on elegant clothes, silken garments, and zisutu (cotton fabric with a red- and blue-checked pattern imported from India). Fragrances were not only important in rituals, but, like clothes, a sign of patrician status. Exquisite perfumes of patchouli, saffron, and expensive civet musk, as well as cloves, were widely traded substances in the Indian Ocean world. While civet musk became an important export good from the Swahili Coast,38 cloves (like cinnamon, nutmeg, and pepper), originally imported from Asia, became much sought-after spices in the Indian Ocean economy. As a result, these spices were also increasingly grown on huge (slave) labour-intensive plantations on Zanzibar and Pemba from the eighteenth century onwards. The scents, textiles, and spices traded were part of what the historian Thomas Vernet characterizes as the ‘premodern phase’ of the Swahili Indian Ocean trade.39 As he shows, relying mostly on Portuguese, French, and British sources from the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, Swahili captains and sailors from Pate island travelled to Madagascar and the Comoros. They not only received goods like cottons and silks, glass, spices, porcelain, and bronze ware from Arab and Indian traders, but also sent their own boats, full of ivory, tortoiseshell, and dried fish, to southern Arabia and western India.

The Liyongo songs animate this early, widely connected world of the Swahili coast, facing both the land and the sea. This would disappear completely from the newly created Islamic poetry of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, authored by scholars adhering to Sufi orders with a new religious zeal, who mostly composed their poetry about the prophets, the hadith, and legendary battles of Islamic history. Rather than East African contexts of hunts or weddings, it was the Arabian Peninsula in the time of the Prophet that provided the setting for the newly created, written tenzi, which supplanted the older, oral tumbuizo. These shifting worlds of poetry reflect what the historian Randall Pouwels describes as a wave of Arabization, which changed a number of cultural as well as literary practices. For Pouwels, the conflict characterizing the Liyongo story echoes a fundamental transition in the region: that of power moving from the Swahili clans in the Tana delta—like Liyongo’s Bauri clan, living in close interaction with their hunting and farming neighbours—to new, proudly Islamic clans of the islands of Pate, and later Lamu, who played active roles in the Sufi brotherhoods.40

Thus, the tumbuizo portray, in a unique form, an early world at the crossroads of multiple cultural affiliations across the ocean, as well as with the mainland. The rhythmically driven tumbuizo, not bound to a linear plot, are different from later poetry, but all follow Liyongo narratives. While most of the tumbuizo do not make direct reference to the Liyongo narratives, they rather create poetic miniatures of dances and hunting scenes in which fruits, trees, and objects play a more crucial role than the acting characters. They work as a succinct poetic commentary that make East African scenes and voices emerge in a poetic and sensorially palpable way.

Overlapping Dynamics: Colonial Collections and Manuscripts in Arabic Script

The oral genre of the utumbuizo, in particular its metrics and sung recitation, largely fell out of use in the nineteenth century, as did much of the ritual of verbal duelling between master poets associated with the gungu.41 Two primary dynamics bore an influence on Swahili literary production, and on the Liyongo story in particular, in the nineteenth century.

First, German and British colonial administration and education, in conjunction with foreign missionary engagement, prompted an emphasis on writing and reading and the fostering of new genres, like the essay, the travelogue, the short story, and the novel.42 New Swahili literary texts were produced, such as translations from the world literary canon, like Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell, which appeared in the Swahili newspaper Kiongozi, published from the 1890s onward. The introduction of modern Western literature, closely linked with print technology, was just one side of the coin, however. As Schüttpelz notes with respect to the gradual dominance of the narrow Western notion of modern literature in Europe from the eighteenth century onward, the categorical separation of oral and written literature, which denied oral literature any literary value, also yielded a counter effect, namely a heightened interest in documenting popular as well as oral literature.43 In a similar way, German and British missionaries, scholars, and layman philologists arrived in East Africa with new narratives and genres, on the one hand, but they also valued and began documenting Swahili oral literature, on the other.44 In an effort to preserve the Swahili literary tradition and to introduce it to both a European academic audience as well as a broader public, a whole series of books and articles on Swahili oral literature as well as the manuscript culture of its poetry was created in the shadow of imperialism between roughly 1850 and 1950. After independence, this production also fed into the East African nation-states’ creation of ‘culturally authentic’ national literature.

Secondly, as mentioned previously, the period between the eighteenth century and 1950 is also when Swahili manuscript culture flourished: a whole new kind of Swahili written poetry emerged, composed and copied in Arabic script. As in many other contexts of vernacularisation worldwide, this poetry was authored by a small elite of highly learned, mobile (Hadhrami) scholars, versed in both Arabic and Swahili and mostly affiliated with the Sufi ʿAlawiyya brotherhood, who were part of the far-reaching Muslim networks across the Indian Ocean.45 Though they had settled in East Africa earlier on, from the eighteenth century onward they promoted education and learning in Arabic (resulting in what I earlier called ‘a wave of Arabisation’), but increasingly also in Swahili. They began systematically translating Arabic Sufi poetry into Swahili, including the Umm al-Qurā, a thirteenth-century Arabic ode to the Prophet, called the Hamziyya in Swahili; the Miraji, a poem about the Prophet’s ascension to the seven heavens; and the Utenzi wa Uhud, depicting a legendary battle that took place during the Prophet’s lifetime.46 For these scholars, Swahili poetry in metrical forms, newly adapted from long, southern Arabian forms, served to address the broader, non-Arabic-speaking parts of the population, and acted as a counterreaction to Christian missionary activities.

These two nineteenth-century dynamics—Western incursions and the Hadhrami promotion of vernacular Swahili written literature—were unequal, as writing did not mean the same thing in both contexts. The former represented a collection of verbal traditions in the context of a print culture inclined towards private reading by a Western audience. The latter infused a pre-existing manuscript culture almost exclusively reserved for religious texts in Arabic with new practices of writing and oral recitation in poetic Swahili. Yet the two dynamics did not contradict each other, but rather added to each other in various ways. The manuscripts of Swahili poetry also fascinated European philologists, who began to collect, edit, and publish them.47

Print did not replace manuscript writing, either, but rather fostered it. Swahili intellectuals furnished Europeans with manuscripts and explanations, but also began to research their own culture and literature more systematically, committing vanishing traditions, like the Liyongo tumbuizo, to writing or adapting them to written poetic genres. Most of the Liyongo tumbuizo have survived chiefly in manuscripts written in the nineteenth century—a time when the first printed versions of the Liyongo poetry and narratives, previously transmitted in a strictly oral fashion, also came into being.48 The tumbuizo were primarily written down by two scribes, Mwalimu Sikujua and the aforementioned Rashid Abdallah, by commission of and in cooperation with William Taylor, the Anglican Bishop of Mombasa. Later, Muhamadi Kijuma (1855–1945), who copied most of the Swahili manuscripts currently kept in London and Hamburg, played an important role in furnishing scholars with poems and explanations—including the German Africanist Ernst Dammann; the philologist Alice Werner; and the editor William Hichens, who planned a whole exquisite anthology of Liyongo poetry.49 Muhamadi Kijuma is also credited with adapting the Liyongo tradition to the dominant poetic narrative form of the time, the utenzi.50 Thus, both Western and East African scholars documented the oral narratives of Fumo Liyongo. The newly produced manuscripts laid the foundations for Swahili manuscript archives not only in East Africa, but also in Europe.51 More importantly, they consecrated Swahili as a literary idiom, with an Islamic written literary tradition comparable to Turkish or Persian.

In the middle of the nineteenth century, Edward Steere, Anglican Bishop of Zanzibar, published a volume of Swahili oral tales, many of which, like Swahili versions of the One Thousand and One Nights, had travelled across the Indian Ocean.52 Even Liyongo had reached Zanzibar: Steere documented a narrative account of the story, as told by Sheikh Mohammed bin Ali, with a few abridged lines of the tumbuizo interspersed in the narrative. Steere recognized the formal importance of those lines and considered them the formulaic core and ‘skeleton’ of the story.53

According to Steere, the narrative was a prose abridgement of an earlier narrative poem, probably similar to the Utenzi wa Liyongo, which Muhamadi Kijuma would later write down for Alice Werner in 1913, but which was only published much later, after independence in East Africa.54 Born as a hagiographic genre that gained prominence in the context of the Sufi movement described above, the utenzi was soon used as a template to document not only contemporary history—first the German colonial raids, and later World War II—but also local oral traditions like the Fumo Liyongo epic.

Unlike the polyphonic cycle of the tumbuizo, a coherent narrative plot characterizes the utenzi. Similar to the prose account documented by Steele, the 232 stanzas of the Utenzi wa Liyongo create sequences of cause and consequence between episodes, from the kikowa meal to the escape from the dungeon, to Liyongo’s ultimate death, which does not figure in the tumbuizo. In both the Utenzi wa Liyongo and Steere’s prose account, Liyongo, a huge giant, is invulnerable. Only a copper needle thrust into his navel can kill him, as his son, who is the one who commits the murder, finds out. Mortally wounded, Liyongo forces himself down a well, where he dies standing upright, weapons in hand, so that people are at first afraid to approach him.

Elements such as the kikowa meal, the imprisonment, and particularly the later details of the plan to kill Liyongo feature not only in the Swahili prose account and its offshoots (including the digital adaptations, on which more below), but also form part of the Bantu Pokomo and Cushitic Dahalo oral narrative traditions of the Tana delta, attesting to their overlapping narrative cultures.55 Unlike later Swahili narrative adaptations, both Steere’s prose account and Kijuma’s Utenzi wa Liyongo portray Liyongo as interacting with neighboring Bantu and Cushitic groups, including through forms of mutual support, but also through oppression and violence.56 These aspects completely disappear in later versions, but bear a resemblance to, or are present in the Pokomo and Dahalo renditions. Contrary to the heroic depictions of Liyongo in the Swahili tumbuizo (and dominant in later written and digital adaptations), Liyongo is a tyrant not only in the Pokomo and Dahalo versions, but also in the Swahili prose account recorded by Steere, according to which he ‘oppressed the people exceedingly’ (akaauthi mno watu).57 In the Pokomo tradition documented by Gustav Fischer in 1880, for instance, Liyongo is much feared, since he enslaves many—symbolically re-narrating a long history of oppression by Swahili rulers. All later narratives instead characterize these clashes as an internal Swahili conflict over the right to rule, while the Utenzi wa Liyongo and the prose account recorded by Steere contain both aspects.58

In the Utenzi wa Liyongo, it is fitina ‘intrigues’ that annoy the sultan of Pate and supply the cause for conflict, hinting at a (later?) Swahili narrative re-layering of the story. References to (ambivalent) relations with the mainland still figure in both the prose account and the Utenzi wa Liyongo, however, where even the Oromo ‘masters of the bush’ fear Liyongo’s strength, and tactically marry one of their women to him.59 Therefore, in the Swahili versions as well as in the Pokomo tradition documented by Fischer, the decision is made to kill him during the kikowa feast, after which the copper needle ultimately does the job.60 Markedly different from the opaque Utumbuizo wa Kikowa, the Utenzi wa Liyongo, whose style is prescribed to be wazi ‘clear’, carefully explains the strategy to kill Liyongo.61

|

Likisa shauri lao Wakenenda kwa kikao Mkoma waupatao Hupanda mtu mmoya |

This was their plan— To go to the feast On reaching a doum palm, [They would ask] one person to climb it. |

|

Na wao maana yao Siku Liyongo apandao Wamfume wute hao Zembe kwa wao umoya |

And they meant that When Liyongo climbed it, They would shoot him, All together, with their arrows. |

The different sequence of the episodes in the prose account and Kijuma’s utenzi reflects the variability of the oral tradition; but it also reflects an effort at streamlining the narrative, linking episodes that were once only loosely aligned and weeding out the incoherent and incomprehensible parts of the oral tradition.62 Unlike the Liyongo tumbuizo—even the written versions of which depend so heavily on the audience’s background knowledge, drawing on a shared world by means of frequent allusions—both the prose account and the written utenzi are self-contained texts. They do not depend on a knowledgeable audience and are not necessarily part of a performance or recitation in which a reciter may mimic certain actions, perform with props, or change his voice based on which character is speaking, and who can also explain allusions or refences.

Moreover, in Steere’s prose account only a few lines of the Liyongo songs are added—exactly the opposite of the tumbuizo manuscripts, where only the songs are recorded, since the episodes were certainly well known and only poetry was deemed important enough to be written down. The Liyongo prose account is cast as a third-person narrative, echoing Western readerly expectations and inclination towards prose.63 The prose account is far removed from the oral rendition and is no longer even meant for recitation. Bound/confined in/to a book, it travels beyond East Africa; not unlike many other documented oral traditions, it would become part of a print library of the world’s folklore.64

Fumo Liyongo in Nationalist and Pan-Africanist Worlds

The Utenzi wa Liyongo increasingly took on a printed form in the twentieth century. In independent East Africa, Kijuma’s poem was first printed, in 1964, in the journal of the East African Swahili Committee, a former colonial body created to standardize the Swahili language and continued by the newly independent socialist national state of Tanzania, eager to craft its own national literary canon.65 Fumo Liyongo became a national hero, a role model fighting for the ‘rights of [people] when they are oppressed’ (akiwatetea haki zao muda wanapodhulumiwa), as the blurb of the 1973 re-edition styled him in the Marxist rhetoric of liberation—doing away with all ambivalent and diverse perspectives.66 While Mringwari, Liyongo’s rival, became the prototypical villain, residing in the palace, Liyongo turned into a revolutionary siding with the downtrodden and fighting for freedom. Liyongo’s world became a national and socialist one.

Neither Schüttpelz nor Werberger, when reflecting on when oral literature was taken out of formal definitions of ‘literature’ and survived merely as a subcategory (oral literature or folklore), consider the period of European imperial expansion or the rise of the modern notion of literature from the eighteenth century onward a decisive point in time; instead they cite the 1960s, when notions of the ‘world’ and ‘literature’ drastically shrank in the West.67 In the early twentieth century, more literary genres and media, including oral ones, were part of people’s lived experience, allowing for a broader perspective on verbal arts in the world. According to Schüttpelz and Werberger, this increased awareness found echo in many more studies of oral literatures, as well as their scholarly discussion.

In independent East Africa, too, the nation’s search for a modern literature institutionalized by universities and schools reduced the scope of literature’s modi existendi, while various forms of verbal art continued to flourish just outside the institutions’ doors. In the modern context—first of the colonial state and later of the nation—school, print, and prose became an inseparable triad. School education relied predominantly on written/printed literature, reinforcing the dominance of the novel and modern poetry, and conceptually separated this literature from oral traditions of communal dance, poetic exchange, and recited poetry, as well as the rhetorical education of the Qurʾanic schools and chama cha ngoma (dance societies). Literature became an academic subject in its own right, separate from historiography, religion, or philosophy, which were (and continue to be) largely the domain of recited discourse embedded in communal practices unrecognized by state institutions. In Dar es Salaam, the Swahili term fasihi ‘literature’ was coined—on the analogy of ‘English literature’—at the university in the 1960s, in the context of independence and the search for a new literature that would lend its imagination to the modern state’s discourse of progress. The creation of the notion of modern Swahili literature, with reference to Marxist notions of realism such as kioo cha jamii (mirror of society), entailed the emergence of another category, namely fasihi simulizi or fasihi ya asili, oral literature or traditional literature. A line was drawn between the two, and oral literature (fasihi simulizi) began to exist merely as a subcategory. The nation’s fundamental modern myth of a new beginning ascribed large parts of the oral tradition to the nation’s past on the basis of a unilineal account of literary history.

As part of the construction of a Swahili national literary canon in both Kenya and Tanzania, the Utenzi wa Liyongo was reprinted in the 1970s, and East African scholars like Joseph Mbele, Ibrahim Noor Shariff, and Mugyabuso Mulokozi increasingly researched various Liyongo narrative traditions in the 1980s and 1990s—also in response to the broader interest in orality, now a subject in its own right.68 Again, the academic focus was on the utenzi and narrative traditions, rather than the older poetic songs of the tumbuizo. On the creative side, adaptations of the Liyongo story as a children’s book appeared, and the story was staged time and again in school classrooms.69 The latter phenomenon hints at the fact that oral recitation did not disappear, but morphed into new forms. The consecration of the Liyongo story in the sacred halls of national literature is not the endpoint of its literary history: oral literature is robust, not in the sense that it remains unaltered, but in the sense that, due to its remarkable adaptability, it does not simply die out.70 The Liyongo story has proven chameleonic, and its persistence is grounded in its disrespect for any boundary-drawing: ‘The popular is opportunistic, hybrid or syncretic in its unashamed, “unlearned” borrowings from the past and present, as it shows its lack of reverence or respect for any demarcation between oral and written, tradition and modernity, or Africa and the West’.71

Nowadays, Fumo Liyongo is far more present on stage and in YouTube videos than in written print adaptations. The Liyongo story has been staged in the context of literary and cultural festivals, which increasingly intersect with the digital realm of the internet. For instance, in the context of the Somali Heritage Week at the Awjama Omar Cultural Research and Reading Centre in Nairobi in 2017, the Liyongo tale was sung in English and Swahili in a newly created, hybridized oral style of storytelling, with a male and a female narrator singing and drumming, a recording of which circulated more widely on YouTube.72 The ‘African’ bilingual performance, involving drumming (previously not part of the Liyongo narratives), targeted both an urban Nairobi audience as well as a global public with a preference for storytelling, also reinvigorating the link between ‘Africanness’ and orality. In these new forms, digital and performative iterations of African oral traditions have been achieving a global reach, partly even overshadowing the novel. Storytelling has become an auratic term, and not only for ‘Afropolitan’ audiences. It reemphasizes performance and orality, which blend into digital representation. The same is true of the global and East African phenomenon of spoken word events, which have gained much prominence in imagining African worlds in the past two decades.

The digital medium adds to the changing ecology of the Liyongo story, which has become part of an all-African literary heritage, particularly for an African diaspora increasingly in search of its African roots. The animated YouTube film ‘Prince Liongo: Tragedy of an Illegitimate Son’ in the Home Team History series—which aims to teach African history to the African diaspora with the slogan ‘Know thyself, remember your ancestors’—renders the Liyongo narrative part of an African archive, countering its absence from Western-dominated historiography. Here, Liyongo figures in a series meant to create a grand narrative of African history, from the Mali Empire and the Fulfulde jihad in West Africa to Shaka the Zulu in South Africa. The video starts with an ‘African’ soundtrack of warrior dances before the storyteller, speaking in sonorous American English, narrates the animated sequence, complete with sound effects. Though the story lacks the kikowa episode and Liyongo’s imprisonment, the major conflict of the Swahili narrative—that of Liyongo and his half-brother Mringwari, with Liyongo ultimately murdered with a copper needle—is largely preserved.73

Fig. 1.2 The dead Fumo Liyongo leaning against the well, so that the women are afraid to fetch water. Video still from ‘Prince Liongo: Tragedy of an Illegitimate Son’.

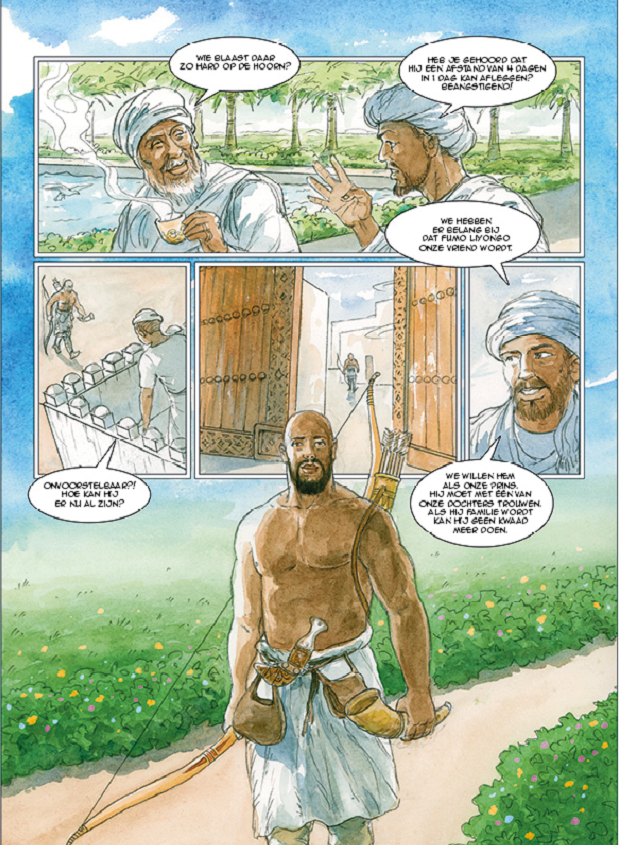

In an even more complex interplay of writtenness, staged orality, and newly created visuals, the Dutch project ‘Ubuntopia’ produced a Dutch-language children’s graphic novel (also available in English) under the title Fumo Liyongo en de Dans van de Drums, written by Leontine van Hooft and richly illustrated by the Rwandan illustrator Jean-Clauda Ngumire; this was also presented in the form of live storytelling sessions and recorded for YouTube.74 ‘Written for children with a connection to Africa’ (geschreven voor kinderen met een connectie met Africa), the graphic novel aims at ‘preserving very old [oral] legends and tales to prevent African wisdoms from disappearing’ (om échte oude [orale] legends en verhalen te conserveren, om te voorkomen dat de Afrikaanse wijsheden).

Fig. 1.3 Liyongo arriving at the palace in Pate after walking a distance that would normally take four days in only one day. Page from Leontine van Hooft and Jean-Claude Ngumire, Fumo Liyongo en de Dans van de Drums verdwijnen.75

Ubuntopia invents an entire ‘African’ world: the frame narrative of the comic portrays the Liyongo story—as well as the South African adaptation Queen Numbi and the White Lions, which is also part of the book—as an orally transmitted tale, narrated by the griot Balla to Aimée, a young girl of colour. The mystical Balla, summoned by the ‘Sages of the World’ to retell the stories, is the keeper of the African heritage. While the Liyongo story is explicitly situated in East Africa, the frame narrative creates a syncretic world, with dialogues using Swahili greetings as well as ‘funga alafia’ (a welcome phrase loosely attributed to West Africa that has circulated widely in world music), Ghanaian Anansi stories, and Balla playing the Mande kora, a figure borrowed from West African griot iconographies. The graphic novel translates the Liyongo narrative, largely in line with the prose account, into a sequence of panels, through which the author Leontine van Hooft guides her audience, also by showing these visuals in the live storytelling sessions. ‘African’ orality, evoked both in the narrative and through its mediatized performances, blends Belgian comic traditions and middle-class Dutch practices of voorlezen (reading out loud)—in the video, Leontine van Hooft is sitting in an armchair, telling the story—in speaking of and to the transcultural audience.

Fig. 1.4 Leontine von Hooft reading from Fumo Liyongo en de Dans van de Drums during Children’s Book Week in 2020. Video still from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7rdrOmDpXVc&t=8s

Interestingly, what resurfaces in each of these examples is not just orality, but the Liyongo figure and tale, which is not simply replaced by a modern, written canon of literature but rather continues to thrive. This brings us back to the notion of non-teleological poetic history that I referred to at the beginning of this chapter. As Alexander Veselovsky found in his lecture ‘From the Introduction to Historical Poetics’ (1894), ‘old images, echoes of images, suddenly appear when a popular-poetic demand has arisen, in response to an urgent call of the times. In this way popular legends recur; in this way, in literature, we explain the renewal of some plots, whereas others are apparently forgotten’.76 Adapting his psychological view of literary history to the Liyongo tale, we find the discovery of ‘old images’, figures, and plots particularly in African diasporic contexts in Europe and the USA that, implicated as they are in the logic of the market, are in urgent ‘popular-poetic’ need of alternative tales about their own identities. The digital mode creates synergies with this process, since it offers the possibility to circumvent the restrictive regime of publishing houses and written canons and to address wider audiences, and it fosters newly mediatised oralities, proudly marking Africanness.

The reappearance of Liyongo in newly adapted forms of orality, then, speaks to Maslov’s emphatic argument, drawing on Veselovsky, that literary history is characterized more by transmutation than by sheer continuity.77 It is a perspective that also emphasises multiple timelines and the diversity of literary history: there is not one single line of development and progress, contrary to the teleological idea that oral literature gives way to the novel. While Maslov’s perspective allows for ruptures and forms of forgetting, it also underlines the persistence of literary form, which can be re-explored even after years, decades, or centuries of silence or oblivion. On the one hand, there is the psychological and ‘poetic’ impetus underlined by Veselovsky, i.e. a universal human need for images and narratives (‘legends’); and, on the other hand, changing ‘calls of the time’ nourish the need to find new imaginaries or to re-explore older ones.

If, in the contemporary contexts of the African diaspora, the search for identity has resulted in the rediscovery and adaptation of many oral traditions, it is the aesthetic nature of images, figures, and plots, I wish to add, which plays a decisive role in fostering the imagination and allowing reinterpretation. Here I refer to aesthetics in its etymological sense of ‘sensual perception’: because Liyongo is a concrete figure placed so powerfully before our eyes, he has survived in people’s memory and nourished their imagination. As his manifold reinterpretations, from tyrant to freedom fighter, show, the captivating figure of Liyongo cannot be reduced to one meaning, nor can his palpable figure be reduced to a single logical argument or idea. Instead, Liyongo has recurrently emerged as a novel ‘revelation’, as Veselovsky puts it, with the power not only to comment on our current world, but also to imagine new worlds:78 the ‘utopia’ in Ubuntopia refers precisely to this.

Conclusions

My account questions the teleological view of Western literary and written influence as an all-pervasive force that rendered hitherto inert forms of oral literature increasingly obsolete. There was no fundamental, earthquake-like shift brought about by Western modernity, which did away with anything pre-existing. Rather, fundamental shifts happen all the time, as my focus on mediatized orality, i.e. orality adapted to new media, from writing to the digital realm, suggests. Even writing does not simply replace orality, since on the Swahili coast writing has coexisted with orality for a long time, as the cases of the Liyongo tumbuizo and the utenzi also show: both were recited but also written in Arabic script long before they made their way into Roman script and into new renditions. Thus, it is rather the relationship between writing (in different scripts) and orality and their institutions which changes over time. Western endeavours to collect and print Swahili oral traditions for a global library interacted dialectically with the manuscript production of the widely connected Muslim brotherhoods. Both print and manuscript poetry threatened some oral genres (like the tumbuizo) and played a decisive role in preserving them. While the Liyongo tale is still part of local oral traditions in northern Kenya, it has also transcended written and printed representation and found new forms in the digital sphere. This process hints at the fundamental dynamism of literary forms, the fuzziness and amorphousness of texts and genres, and further questions (constructed) dichotomies of orality and literacy. The so-called Liyongo epic is not one, neatly defined text: Liyongo stories and songs have always been shaped by multiple and often interplaying influences from different directions.

Even the worlds of which the Liyongo narrative is part and which it constructs are fuzzy and dynamic. The world of Liyongo does not simply grow bigger or more complex over time, from a locally confined dance tradition to the digital sphere. The Liyongo tumbuizo evoke far-reaching Indian Ocean connections as well as the overlapping, multi-ethnic context of the Tana delta, where Liyongo stories have been shared across linguistic and cultural boundaries. Some aspects of this multi-ethnic space, with its multiple perspectives, partly recur in the utenzi and prose accounts as well as in contemporary versions told by elders on Lamu; but these elements are increasingly lost in later print and digital adaptations, which streamline the various literary modi existendi into a single, coherent, written narrative. The nineteenth-century coexistence of manuscript poetry, printed collections, and dance and narrative traditions in several languages, located and circulating in different worlds, is in fact more (or at least as) diverse in terms of literary form and circulation than the present-day spectrum that ranges from printed texts to comic books, digitized performances, and animated films. All of this reminds us of the complexity of literary configurations, a complexity that is not particular to African contexts but to all verbal art, once we move away from the ‘narrow church’ of defining a literary work by its author and by the printed pages between book covers, or from defining literary history as moving in only one direction, as has too often been done in the context of world literature.

Bibliography

Barber, Karin, ‘African-language Literature and Postcolonial Criticism’, Research in African Literatures, 26.4 (1995), 3–28.

Beecroft, Alexander, An Ecology of World Literature: From Antiquity to the Present Day (New York: Verso, 2015).

Chamberlain, Daniel, ‘Histories of Literature and the Question of Comparative Oral Literary History’ in Or Words to That Effect: Orality and the Writing of Literary History, ed. by Daniel Chamberlain and J. Edward Chamberlin (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2016), pp. 33–46.

Chamberlin, J. Edward, ‘Preliminaries’ in Or Words to That Effect: Orality and the Writing of Literary History, ed. by Daniel Chamberlain and J. Edward Chamberlin (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2016), pp. 3–32.

Chapman, Michael, ‘”Oral” in Literary History: The Case of Southern African Literatures’ in Or Words to That Effect: Orality and the Writing of Literary History, ed. by Daniel Chamberlain and J. Edward Chamberlin (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2016), pp. 149–161.

Chum, Haji, Utenzi wa Vita vya Uhud, ed. by H. E. Lambert (Nairobi: East African Literature Bureau, 1962).

Finnegan, Ruth, Oral Literature in Africa (London: Clarendon, 1970).

‘Fumo Liyongo’, Awjama cultural center (2018), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2anOMFLs4-M&t=231s

Fischer, Gustav, ‘Das Wapokomo-Land und seine Bewohner’, Mitteilungen der Geographischen Gesellschaft in Hamburg, 1878/79 (1880), 1–57.

Geider, Thomas, Die Figur des Oger in der traditionellen Literatur und Lebenswelt der Pokomo in Ost-Kenya (Cologne: Köppe, 1990).

——, ‘Weltliteratur in der Perspektive einer Longue Durée II: Die Ökumene des swahilisprachigen Ostafrika’ in Wider den Kulturenzwang: Migration, Kulturalisierung und Weltliteratur, ed. by Özkan Ezli, Dorothee Kimmich, and Annette Werberger (Bielefeld: transcript, 2009), pp. 361–401.

Gunner, Liz, ‘Ecologies of Orality’ in The Cambridge Companion to World Literature, ed. by Ben Etherington and Jarad Zimbler (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 116–132.

Harries, Lyndon, ‘A Swahili Takhmis from the Swahili Arabic Text’, African Studies, 11.2 (1952), 59–67.

——, Swahili Poetry (Oxford: Clarendon, 1962).

Horton, Mark and John Middleton, The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000).

Kijuma, Muhammad, Utenzi wa Fumo Liyongo, ed. by Abdilatif Abdalla (Dar es Salaam: Chuo cha Uchunguzi wa Lugha ya Kiswahili, Chuo Kikuu cha Dar es Salaam, 1973).

Klein-Arendt, Reinhard, ‘Liongo Fumo: Eine ostafrikanische Sagengestalt aus der Sicht der Swahili und Pokomo’, Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere, 8 (1986), 57–86.

Kliger, Ilya and Boris Maslov, ‘Introducing Historical Poetics: History, Experience, Form’ in Persistent Forms: Explorations in Historical Poetics, ed. by Ilya Kliger and Boris Maslov (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016), pp. 1–36.

Knappert, Jan, ed., Utenzi wa Fumo Liongo – The Epic of King Liongo (Dar es Salaam: East African Swahili Committee, 1964).

——, ‘Liongo’s Wedding in the Gungu Meter’, Annales Aequatoria, 12 (1991), 213–226.

Lamping, Dieter, ‘Was ist Weltliteratur? Ein Begriff und seine Bedeutungen’ in Perspektiven der Interkulturalität: Forschungsfelder eines umstrittenen Begriffs, ed. by Anton Escher and Heike Spickermann (Heidelberg: Winter, 2018), pp. 127–141.

Levine, Caroline, ‘The Great Unwritten: World Literature and the Effacement of Orality’, Modern Language Quarterly, 74.2 (2013), 218–237.

Maslow, Boris, ‘Lyric Universality’ in The Cambridge Companion to World Literature, ed. by Ben Etherington and Jarad Zimbler (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 133–148.

Mbele, Joseph, ‘The Identity of the Hero in the Liongo Epic’, Research in African Literatures, 17 (1986), 464–472.

Meinhof, Carl, ‘Das Lied des Liongo’, Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen, 15 (1924–25), 241–265.

Miehe, Gudrun, ‘Preserving Classical Swahili Poetic Traditions: A Concise History of Research up to the First Half of the 20th Century’ in Muhamadi Kijuma: Texts From the Dammann Papers and Other Collections, ed. Gudrun Miehe and Clarissa Vierke (Cologne: Köppe, 2010), pp. 18–39.

Miehe, Gudrun and Clarissa Vierke, eds, Muhamadi Kijuma: Texts from the Dammann Papers and Other Collections (Cologne: Köppe, 2010).

Miehe, Gudrun et al., eds, Liyongo Songs: Poems Attributed to Fumo Liyongo (Cologne: Köppe, 2004).

Mulokozi, Mugyabuso, Tenzi Tatu Za Kale (Dar Es Salaam: Taasisi Ya Uchunguzi Wa Kiswahili, 1999).

Pouwels, Randall, ‘Eastern Africa and the Indian Ocean to 1800: Reviewing Relations in Historical Perspective’, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 35.2–3 (2002), 385–425.

‘Prince Liongo: Tragedy of an Illegitimate Son’, Home Team History, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q3ll-IofyEU&t=33s

Sacleux, Charles, Dictionnaire swahili-français (Paris: Institut d’Ethnologie, 1939).

Schüttpelz, Erhard, ‘Weltliteratur in der Perspektive einer Longue Durée I: Die fünf Zeitschichten der Globalisierung’ in Wider den Kulturenzwang: Migration, Kulturalisierung und Weltliteratur, ed. by Özkan Ezli, Dorothee Kimmich, and Annette Werberger (Bielefeld: transcript, 2009), pp. 339–360.

——, ‘World Literature from the Perspective of Longue Durée’ in Figuren des Globalen: Weltbezug und Welterzeugung in Literatur, Kunst und Medien, ed. by Christian Moser and Linda Simonis (Göttingen: V&R unipress, 2014), pp. 141–156.

Shariff, Ibrahim Noor, ‘The Liyongo Conundrum: Re-Examining the Historicity of Swahili’s National Poet-Hero’, Research in African Literatures, 22 (1991), 153–167.

Steere, Edward, Swahili Tales as Told by Natives of Zanzibar (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1870).

Tihanov, Galin, ‘Introduction’ in Vergleichende Weltliteraturen/Comparative World Literatures, ed. by Dieter Lamping and Galin Tihanov (Stuttgart: Metzler, 2019), pp. 283–287.

Tosco, Mauro, A Grammatical Sketch of Dahalo: Including Texts and a Glossary (Hamburg: Buske, 1991).

van Hooft, Leontine, and Jean-Claude Ngumire, Balla and the Forest of Legends: The Chronicles of Ubuntopia, Part 1 (GreenDreamWorks, 2019), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7rdrOmDpXVc&t=8s

Vernet, Thomas, ‘East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean: Swahili Ships, Swahili Mobilities ca. 1500–1800’ in Trade, Circulation, and Flow in the Indian Ocean World, ed. by Michael Pearson (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp. 167–202.

Vierke, Clarissa, ‘Other Worlds: The “Prophet’s Ascension” as World Literature and Its Adaptation in Swahili-speaking East Africa’ in Vergleichende Weltliteraturen/Comparative World Literatures, ed. by Dieter Lamping and Galin Tihanov (Stuttgart: Metzler, 2019), pp. 215–229.

——, ‘Poetic Links across the Ocean: On Poetic “Translation” as Mimetic Practice at the Swahili Coast’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 37.2 (2017), 321–335.

Werberger, Annette, ‘Weltliteratur und Folklore’ in Vergleichende Weltliteraturen/Comparative World Literatures, ed. by Dieter Lamping and Galin Tihanov (Stuttgart: Metzler, 2019), pp. 323–341.

Werner, Alice, ‘A Traditional Poem Attributed to Liongo Fumo’ in Festschrift Meinhof (Hamburg: Friederichsen & Co, 1927), pp. 45–54.

——, ‘Some Notes on East African Folklore’, Folklore, 25.4 (1914), 457–475.

——, ‘The Swahili Saga of Liongo Fumo’, Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, 4 (1926/28), 247–255.

Würtz, Ferdinand, ‘Die Liongo-Sage der Ost-Afrikaner. Kleine Mittheilungen’, Zeitschrift für Afrikanische und Ozeanische Sprachen, 2 (1896), 88–89.

1 This article is partly the outcome of research conducted within the Africa Multiple Cluster of Excellence at the University of Bayreuth, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany ́s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2052/1 – 390713894.

2 Annette Werberger,‘Weltliteratur und Folklore’ in Vergleichende Weltliteraturen/Comparative World Literatures, ed. by Dieter Lamping and Galin Tihanov (Stuttgart: Metzler, 2019), pp. 323–341.

3 See also Daniel Chamberlain, ‘Histories of Literature and the Question of Comparative Oral Literary History’ in Or Words to That Effect: Orality and the Writing of Literary History, ed. by Daniel Chamberlain and J. Edward Chamberlin (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2016), pp. 33–46; Erhard Schüttpelz, ‘World Literature from the Perspective of Longue Durée’ in Figuren des Globalen: Weltbezug und Welterzeugung in Literatur, Kunst und Medien, ed. by Christian Moser and Linda Simonis (Göttingen: V&R Unipress, 2014), pp. 141–156 (p. 150). For Annette Werberger, but also Erhard Schüttpelz, the period between 1860 and 1960 is one of increasing global connections, in which the boundaries between oral and written literature are less categorical. Even if the study of oral texts of that time is not free of biases and misconceptions, both identify moments of comparison and productive exchange between written and oral cultures both in scholarship and writing before the 1960s. After 1960, in the postcolonial era and with an increasing emphasis on monolingual philologies, Werberger and Schüttpelz find oral literature increasingly denied its status as ‘literature’ in both the West and the former colonies.

4 Alexander Beecroft, An Ecology of World Literature: From Antiquity to the Present Day (New York: Verso, 2015); Caroline Levine, ‘The Great Unwritten: World Literature and the Effacement of Orality’, Modern Language Quarterly, 74.2 (2013), 218–237.

5 Galin Tihanov, ‘Introduction’ in Vergleichende Weltliteraturen/Comparative World Literatures, ed. by Dieter Lamping and Galin Tihanov (Stuttgart: Metzler, 2019), pp. 283–287 (p. 285).

6 Tihanov, ‘Introduction’, p. 286.

7 Ibid., p. 285.

8 For criticism, see Sara Marzagora, ‘African-language Literatures and the “Transnational Turn” in Euro-American Humanities’, Journal of African Cultural Studies, 27.1 (2015), 40–55; Clarissa Vierke, ‘Other Worlds: The ‘Prophet’s Ascension’ as World Literature and Its Adaptation in Swahili-speaking East Africa’ in Vergleichende Weltliteraturen/Comparative World Literatures, ed. by Dieter Lamping and Galin Tihanov (Stuttgart: Metzler, 2019), pp. 215–229.

9 Dieter Lamping, ‘Was ist Weltliteratur? Ein Begriff und seine Bedeutungen’ in Perspektiven der Interkulturalität: Forschungsfelder eines umstrittenen Begriffs, ed. by Anton Escher and Heike Spickermann (Heidelberg: Winter, 2018), pp. 127–141 (p. 137).

10 See also Levine, ‘The Great Unwritten’, p. 225.

11 Karin Barber, ‘African-language Literature and Postcolonial Criticism’, Research in African Literatures, 26.4 (1995), 3–28.

12 Barber, ‘African-language Literature’, p. 7.

13 Liz Gunner, ‘Ecologies of Orality’ in The Cambridge Companion to World Literature, ed. by Ben Etherington and Jarad Zimbler (Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 116–132.

14 Beecroft, Ecologies, pp. 16, 17–21.

15 Ruth Finnegan, Oral Literature in Africa (London: Clarendon, 1970); Mugyabuso M. Mulokozi, The African Epic Controversy (Berlin: Fabula, 2002).

16 Dieter Lamping, ‘Weltliteratur?’, p. 135.

17 Boris Maslow, ‘Lyric Universality’ in The Cambridge Companion to World Literature, ed. by Etherington and Zimbler, pp. 133–148 (p. 135).

18 Randall Pouwels, ‘Eastern Africa and the Indian Ocean to 1800: Reviewing Relations in Historical Perspective’, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 35.2–3 (2002), 285–425 (p. 407), DOI:10.2307/3097619; Reinhard Klein-Arendt, ‘Liongo Fumo: Eine ostafrikanische Sagengestalt aus der Sicht der Swahili und Pokomo’, Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere, 8 (1986), 57–86; Ibrahim Noor Shariff, ‘The Liyongo Conundrum: Re-Examining, the Historicity of Swahili’s National Poet-Hero’, Research in African Literatures, 22 (1991), 153–167.

19 Pouwels, ‘Eastern Africa’, p. 407.

20 In Gudrun Miehe et al., eds, Liyongo Songs: Poems Attributed to Fumo Liyongo (Cologne: Köppe, 2004), p. 36.

21 The tradition of the kikowa—or chikowa in Pokomo—was not only a Swahili cultural practice, but widespread throughout the whole Tana region; see Thomas Geider, Die Figur des Oger in der traditionellen Literatur und Lebenswelt der Pokomo in Ost-Kenya (Cologne: Köppe, 1990), p. 145.

22 On ‘strangeness’ in oral traditions, see J. Edward Chamberlin, ‘Preliminaries’ in Or Words to That Effect: Orality and the Writing of Literary History, ed. by Daniel Chamberlain and J. Edward Chamberlin (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2016), pp. 3–32 (p. 16). On the complicated editorial history of the Liyongo songs, see Miehe et al., ed., Liyongo Songs, pp. 1–15.

23 Charles Sacleux, Dictionnaire swahili-français (Paris: Institut d’Ethnologie, 1939), s.v.

24 Edward Steere, Swahili Tales as Told by Natives of Zanzibar (London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1870), p. xi.

25 Sacleux, Dictionnaire, s.v.

26 The fragment is stored in the collection of William Taylor at SOAS and reproduced in Lyndon Harries, Swahili Poetry (Oxford: Clarendon, 1962), pp. 172–173.

27 Alice Werner, ‘A Traditional Poem Attributed to Liongo Fumo’ in Festschrift Meinhof (Hamburg: Friederichsen & Co., 1927), pp. 45–54 (p. 46); Pouwels, ‘Eastern Africa’, pp. 400–408.

28 Alice Werner, ‘Some Notes on East African Folklore’, Folklore, 25.4 (1914), 457–475 (p. 457).

29 Klein-Arendt, ‘Liongo Fumo’, pp. 57–86; Alice Werner, ‘The Swahili Saga of Liongo Fumo’, Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, 4 (1926/28), 247–255.

30 Miehe et al., Liyongo Songs, pp. 54, 55 (stanza 8). The term ‘Galla’ in reference to Oromo groups is nowadays mostly considered derogatory.

31 Ibid., pp. 44, 45.

32 On the house as symbolic marker of Swahili Islamic cultural distinction, in opposition to the dwellings of commoners and slaves, as well as the unordered wilderness which was associated with the wild spirits threatening to encroach on urban spaces, see Mark Horton and John Middleton, The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), pp. 115ff.

33 Miehe et al., eds, Liyongo Songs, pp. 46, 47.

34 Ibid., pp. 72, 73.

35 Ibid., p. 47.

36 Ibid., pp. 44, 45.

37 Jan Knappert, ‘Liongo’s Wedding in the Gungu Meter’, Annales Aequatoria, 12 (1991), 213–226 (p. 214). The verses below (stanza 10–15) are taken from Miehe et al., eds, Liyongo Songs, p. 40 (emphasis mine).

38 Horton and Middleton, Swahili, p. 13.

39 Thomas Vernet, ‘East African Travelers and Traders in the Indian Ocean: Swahili Ships, Swahili Mobilities ca. 1500–1800’ in Trade, Circulation, and Flow in the Indian Ocean World, ed. by Michael Pearson (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), pp. 167–202. See also Horton and Middleton, Swahili, pp. 13ff.

40 Pouwels, Eastern Africa, p. 407.

41 Verbal duelling outside the gungu did not disappear, however, but continued in a variety of different forms.

42 See Thomas Geider, ‘Weltliteratur in der Perspektive einer Longue Durée II: Die Ökumene des swahilisprachigen Ostafrika’ in Wider den Kulturenzwang: Migration, Kulturalisierung und Weltliteratur, ed. by Özkan Ezli, Dorothee Kimmich, and Annette Werberger (Bielefeld: transcript, 2009), pp. 361–401.

43 Schüttpelz, ‘World Literature’, p. 148; also Erhard Schüttpelz, ‘Weltliteratur in der Perspektive einer Longue Durée I: Die fünf Zeitschichten der Globalisierung’ in Wider den Kulturenzwang, ed. by Özkan Ezli, Dorothee Kimmich, and Annette Werberger (Bielefeld: transcript, 2009), pp. 339–360 (p. 351).

44 Schüttpelz, ‘Weltliteratur’, pp. 375–382. See also Gudrun Miehe, ‘Preserving Classical Swahili Poetic Traditions: A Concise History of Research up to the First Half of the 20th Century’ in Muhamadi Kijuma: Texts From the Dammann Papers and Other Collections, ed. by Gudrun Miehe and Clarissa Vierke (Cologne: Köppe, 2010), pp. 18–39.

45 See Clarissa Vierke, ‘Poetic Links across the Ocean: On Poetic “Translation” as Mimetic Practice at the Swahili Coast’, Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 37.2 (2017), 321–335, https://doi.org/10.1215/1089201x-4132941

46 On the Hamziyya, see Lyndon Harries, ‘A Swahili Takhmis from the Swahili Arabic Text’, African Studies, 11.2 (1952), 59–67, https://doi.org/10.1080/00020185208706867 For an overview of the Miraji, see Vierke, ‘Worlds’, pp. 215–229. On the Utenzi wa Uhud, see Haji Chum, Utenzi wa Vita vya Uhud, ed. by H. E. Lambert (Nairobi: East African Literature Bureau, 1962).

47 For an overview, see Miehe, ‘Preserving’, pp. 18–39.

48 There is one earlier, unique example: the reputed Sufi scholar and poet Sayyid Abdullahi bin Nasiri (c. 1720–1820 CE), renowned for his Al-Inkishafi, the Swahili poetic masterpiece of mystical reflection, wrote—in a five-line takhmisi form derived from southern Arabian verse prosody—the so-called Takhmisi, the earliest written Liyongo poem, also called the Wajiwaji. This is another example of the synergies between Sufi manuscript culture and the adaptation of oral poetry. Steere (Tales, pp. 453ff.) reproduced part of the Takhmisi. Later, Carl Meinhof published a critical text edition based on several manuscript versions; Meinhof, ‘Das Lied des Liongo’, Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen, 15 (1924–25), 241–265.

49 In the 1930s, Hichens started a series called Azanian Classics, in which two poems, the Utenzi wa Mwana Kupona and the Mikidadi na Mayasa, were published. Hichens had planned for more Swahili poetry to be published, but the editions of the Liyongo poems and others were never produced. Manuscripts of these poems can be found in the SOAS Swahili Manuscripts Collections.

50 See Muhamadi Kijuma, ed. by Miehe and Vierke.

51 Swahili philology became a recognized academic discipline first at the Seminar of Oriental Studies in Berlin, then at SOAS in London, and, gradually, also in Dar es Salaam— writing working again as a proof of literary value.

52 Geider, ‘Weltliteratur’.

53 Steere, Tales, p. vii.

54 Like many other poems that Muhamadi Kijuma wrote down, it is not clear if he created the utenzi version himself or relied on a pre-existing utenzi composed by someone else.

55 See Klein-Arendt, ‘Liongo Fumo’, pp. 13ff.; Geider, Oger, p. 144; Mauro Tosco, A Grammatical Sketch of Dahalo Including Texts and a Glossary (Hamburg: Buske, 1991), pp. 117–119.

56 See also Muhammad Kijuma, Utenzi wa Fumo Liyongo, ed. by Abdilatif Abdalla (Dar es Salaam: Chuo cha Uchunguzi wa Lugha ya Kiswahili, Chuo Kikuu cha Dar es Salaam, 1973), p. i.

57 Steere, Tales, pp. 438–439; Geider, Oger, pp. 144ff.

58 Gustav Fischer, ‘Das Wapokomo-Land und seine Bewohner’, Mitteilungen der Geographischen Gesellschaft in Hamburg, 1878–79 (1880), 1–57. See also Ferdinand Würtz, ‘Die Liongo-Sage der Ost-Afrikaner. Kleine Mittheilungen’, Zeitschrift für Afrikanische und Ozeanische Sprachen, 2 (1896), 88–89.

59 Kijuma, Utenzi, p. 4 (stanza 45).

60 Fischer, ‘Wapokomo’, pp. 1–57. See also Würtz, ‘Liongo-Sage’, pp. 88–89. In the Dahalo tradition, documented by Mauro Tosco, ‘Fumo Aliongwe’ is also pricked in the navel by his only child, who was sent by ‘the Swahili people’ who ‘did not love Fumo Aliongwe’ (Tosco, Dahalo, p. 117).

61 Kijuma, Utenzi, p. 5. The two stanzas, 58 and 59, are taken from the same publication. The translation is mine.

62 See Gunner’s (Ecologies, pp. 116–132) comparison of the thoroughly documented oral versions of the Sunjata epic with narrative translations freed of all variations and obscurity, targeting a Western audience interested in the world’s literature.

63 By contrast, Steere (Tales, p. v) defines the learner of Swahili as the target reader.

64 On the interrelationship between notions of world literature and the world’s literatures and their corresponding book series, see Levine, ‘Unwritten’.

65 Utenzi wa Fumo Liongo—The Epic of King Liongo, ed. by Jan Knappert (Dar es Salaam: East African Swahili Committee, 1964).

66 Kijuma, Utenzi.

67 Schüttpelz, ‘World Literature’, p. 150; Werberger, ‘Folklore’, p. 323.

68 See, for instance, Joseph Mbele, ‘The Identity of the Hero in the Liongo Epic’, Research in African Literatures, 17 (1986), 464–472; Mugyabuso Mulokozi, Tenzi Tatu Za Kale (Dar Es Salaam: Taasisi Ya Uchunguzi Wa Kiswahili, 1999); and Ibrahim Noor Shariff, ‘The Liyongo Conundrum: Re-Examining the Historicity of Swahili’s National Poet-Hero’, Research in African Literatures, 22 (1991), 153–167.

69 An example of the children’s book is Bitugi Matundura, Mkasa wa Shujaa Liyongo (Nairobi: Phoenix, 2001).