7. Orature Across Generations Among the Guji-Oromo of Ethiopia

©2025 Tadesse Jaleta Jirata, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0405.07

Introduction

We teach our children through storytelling. Our children play with each other through riddling and singing. That is our culture and way of life; our knowledge and values transmitting from generation to generation.

With these words, fifty-two-year-old Areri Roba reflected on the role of oral literature in connecting generations among the Guji-Oromo society.1 As is clear from the statement, oral literature, understood as a culturally embedded and orally performed form of art that a society owns, is an integral part of social relationships across generations as well as within the same generation.2 In broader terms, oral literature has been a central component of cultures across the whole African continent. Within Ethiopia, it embodies a relatively intact oral flow of information and everyday life experiences.3 The Somali, Sidama, Hadiyya, and Borana peoples use oral literary forms to express their ideas, beliefs, and values, and communicate through their network of social relationships (see also Yenaleam and Desta in Chapter 6 of this volume).4 A study of oral literature among the Nuer and Anuak peoples in the Gambela region of western Ethiopia helps us to understand their cultural practices and social organisation across generations.5 Such wealth of oral traditions within Ethiopia is comparable with how Ruth Finnegan conceptualised oral literature as the heart of cultures and memories, in which local languages are used as vehicles for the transmission of knowledge and values.6 Therefore, oral literature characterises the grand artistic lives of the African peoples and has a significant place in their social and cultural lives.

In all African cultures, the central feature that distinguishes oral literature from its written counterpart, and gives life to its artistic realisation, is performance.7 According to Finnegan, oral literature is reliant on a person who performs it in a specific context.8 Oral literature can only be realised as a literary product through performance. Without its oral realisation by a performer (singer or speaker), an oral literary form does not have a defined existence.9 Performance gives life to different oral literary genres and allows them to be identified as myths, folk tales, folk songs, riddles, or proverbs.10 This idea holds two meanings. Firstly, these literary forms are realised through the oral medium, for they are performed through a spoken language. Secondly, these oral literary forms are distinguished by textual form and performance style. The modality of performance also distinguishes oral literary genres across generations. As Jirata and Simonsen state, what we call children’s oral literature and adults’ oral literature derive their identity from different performance styles and contexts.11

These rich and profound oral literary forms have been constantly overlooked in world literary studies. Although oral literature has been an integral and popular repertoire of literary forms in Africa, it has not received global attention as a literary product and has rarely been considered as “literature proper” in global literary scholarships. It has seldom been taken as a sophisticated artistic product. It has been rather studied as a reflection of “authentic” culture or part of the “traditional” way of life, and on these grounds oral literature has been perceived to be less relevant in the context of modern literary production.12 Oral literature has long been associated with illiterate societies, and is therefore considered a residual leftover of a pre-modern past that lacked literary quality. It has also been understood as a preserve of the elders and is perceived as opposed to the social and cultural dynamism of the contemporary world. As a result, oral literature has been pushed to the margin of world literary scholarship.

In this chapter, I argue against this supposition by showing that oral literature is a dynamic artistic phenomenon adaptable to changing social contexts and circulating not only between different generations but also within the same generation. Oral literature, this chapter shows, passes not only from adults to children but also from children to adults, as well as from children to children. From this perspective, I argue that oral literature has continued to be an integral part of both adults’ and children’s cultures. My argument addresses the following questions: 1) What genres does Guji-Oromo oral literature encompass? 2) How do the different forms of the Guji-Oromo oral literature circulate? 3) Which generational groups are more active in the performance and circulation of oral literature? By answering these questions, I will show that oral literature is a dynamic cultural phenomenon, in which intra-generational and intergenerational artistic performances adapt to changing social and cultural contexts.

Socio-Cultural Background of the Guji-Oromo

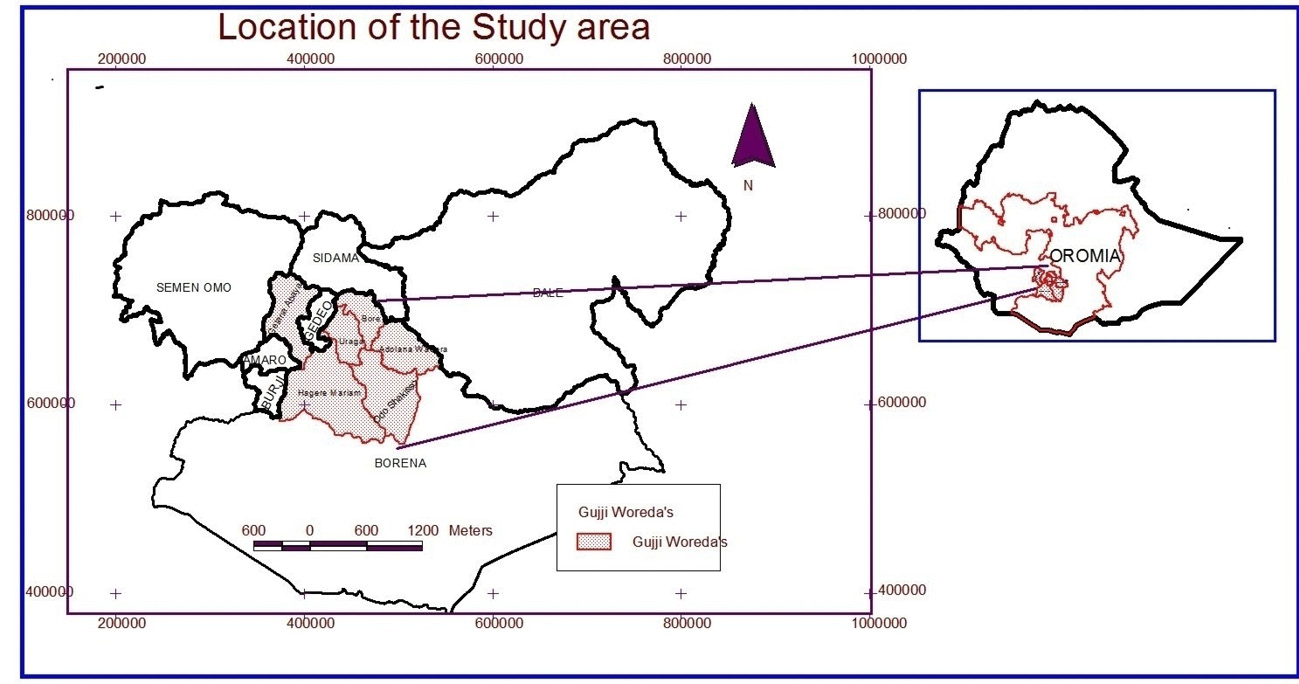

The Guji-Oromo are one of the Oromo ethnic groups living over a large territory in the southern part of Ethiopia. They speak the Oromo language and are known as the cultural cradle of Oromo society because indigenous Oromo institutions such as the Gada system (see below) are still intact among them.13

The Guji predominantly inhabit rural areas, and their population is estimated to be 2 million.14 Guji land is bordered by the Borana-Oromo in the south; Burji, Koyra, and Gamo in the southwest; Arsi-Oromo in the east; and the Gedeo, Sidama, and Wolaita ethnic groups in the north.

Fig. 7.1 Study area. Author’s map.

The Guji land consists of semi-highland and lowland areas with an altitude of 1500–2000 meters above sea level and less than 1500 meters above sea level respectively. The people who live in both areas subsist on mixed farming. They herd cattle and cultivate food crops such as teff, maize, and beans. Besides, they follow traditional methods of bee farming, through which they make money for their home expenditures.15 The Guji-Oromo predominantly lead traditional ways of life in which oral communication plays a central role. Unlike neighbouring ethnic groups that are more internally uniform, the Guji contain three culturally similar clans: the Huraga, Mati, and Hokku. According to my informants, Huraga is the largest and most senior clan; Mati is the second largest and more junior; whereas Hokku is the smallest and most junior clan.16

The Oromo Gadaa system is the social structure that regulates and administers Guji society. It divides society into thirteen age groups or generational grades that succeed each other every eight years, prescribing progressive roles and social responsibilities.17 These grades are known as Daballe (0–8 years), Qarree Xixiqa (9–12 years), Qarree Gurgudda (13–16 years), Kuusa (17–24 years), Raaba (25–32 years), Doorii (33–40 years), Gadaa (41–48 years), Batu (49–56 years), Yuba (57–64 years), Yuba Gudda (65–72 years), Jaarsaa (73–80 years), and Jarsa Qulullu (above 80 years). The Gadaa system organizes the social roles of the Guji-Oromo around these generational grades and assigns specific obligations as well as rights to members of each group.18 The clans are mutually independent and have delegates in the Gadaa Council. However, the leader of the Gadaa grade (Abba Gadaa) is always from the Huraga clan.

The Gadaa system governs and shapes everyday life, cultural practices, and the value system of individuals, families, and clans. It regulates relationships between individuals, including prescribing the norms of parent-child relationships, adult-child relationships, and wife-husband relationships. It codifies the place of an individual in society and regulates the systems of political decision-making, power relations and power transfer, as well as the relations of the Guji with their neighbouring ethnic groups, with nature, and with supernatural powers.19

The Gadaa system structures beliefs, value systems, individual behaviours, responsibilities, social places, and cultural roles across every stage of a person’s life. Accordingly, parents have the obligation to socialise their children, raise them in line with Guji norms and values, and teach them what is expected from them as children. Oral advice and reprimands are the major means of socialisation. Children are expected to be obedient, hardworking, and loyal. Children have a rich culture of play in which parents also participate.20 Such participation on the part of the parents has two purposes. The first is providing evening entertainment in one’s home before bedtime. The second is the socialisation of children. Not only members of a family, but also neighbouring (olla) families come together at someone’s home or in a village compound to entertain each other. Oral literature plays a central role in these intra-generational and intergenerational relationships and social interactions.

Methodology

I carried out fieldwork among the Guji-Oromo in two phases, from July to December 2016 and from May to August 2017. To select appropriate locations for my fieldwork I made preliminary visits to rural districts where the Guji-Oromo reside in big villages. I then identified four rural villages where I would focus my fieldwork, namely Sorroo, Dhokcha, Bunata, and Samaro. These villages are far from each other, and were chosen as representatives of the Guji-Oromo rural ways of life. The fieldwork involved ethnographic methods of data collection, including participant observation, ethnographic interviews (an informal interview that takes place in a natural setting as a part of participant observation), and in-depth interviews. I observed and recorded activities in the villages and homes of the Guji-Oromo, and oral performances in the collective customary practices known in Oromo as jilaa. Of these customary practices, the most relevant for this research were the Balli Kenna, a ritual through which power is transferred from the outgoing Gadaa generation to the incoming one at a sacred place called Me’ee Bokko; and the Lagubasa, an initiation ritual marking the younger generation’s transition from childhood to adulthood at another sacred place called Gadab Dibbedhogo. Both are big traditional ceremonies involving three generational grades, the Raaba, Dori, and Gadaa. The Lagubaasaa is a rite of passage in which people in the Kuusa generational grade pass to the Raaba generational grade and gain the right to join the Dori and the Gadaa generations during ceremonial practices. These cultural events were marked and embellished by a vigorous and overwhelming performance of oral literary forms.

I also carried out participant observations among teams of people while they performed agricultural work and during social and cultural events in the neighbourhood, such as marriage ceremonies, extended family parties, and parties after cooperative work. I conducted unstructured interviews with adults at their homes and workplaces and children (in the age range between seven and fourteen) in the cattle-herding fields and in their school compounds.

My methods of data collection involved close interaction with Guji-Oromo adults and children in the places they normally frequent—their homes and neighbourhood, schools, workplaces, and cattle herding fields. I collected different oral literary texts, paying attention to the interplay between text, performers, and the social and cultural context of the performance. I later translated the oral texts from the Oromo language into English through a contextual translation method, and will present them in English throughout this chapter.

Oral Literary Traditions of the Guji-Oromo

The rich oral traditions of the Guji-Oromo convey and shape their ways of life and their knowledge system. Their individual and collective wisdom and verbal creativity are manifested through oral performances. Therefore, oral literature is an integral part of adults’ and children’s culture. The several cultural and social events that bring the Guji-Oromo together are always embellished by the performance of oral literary forms.21 Based on the performance style, Guji-Oromo literary forms are often categorized as: oduuduri (myths and legends), duriduri (folk tales), weedduu (folk songs), hibboo (riddles), mammaaksa (proverbs) and jechama (sayings). Similarly, based on the contexts and purposes of performance, these forms are categorized as adults’ oral literature, oral literature shared by both adults and children, or children’s oral literature. In this sense, oral genres are already classified based on the different configurations of performer and audience. Defining these genres also includes the modality of transmission and circulation: who performs the oral text to whom and in which context. A genre is not only defined by its textual characteristics, such as meter or rhyme, but also by the social status of the performer and by the social context of the performance. For example, performances of oral songs by adults are characterized by audacity, vividness, tonality, the symbolic presentation of messages, conventionality, and a focus on artistic quality. Those by children involve creativity, captivating actions, playfulness, and interpersonal competitions. In both cases, literariness is created through a performance that encompasses verbal and non-verbal styles, including mimicry, artistic gestures, voices, and tones. The literariness of oral literature, then, lies in the text and performance which shows that it is both orature and literature. This rich oral literary tradition has contributed to the development of Oromo written literatures (see Ayele K. Roba in Chapter 3 of this volume). It is also a dominant literary form through which Oromo literary traditions can be represented in world literature. This implies that Africa can be part of world literature through its oral literary traditions.

Adults’ Oral Literary Forms

This category includes the oral literary forms that are produced and performed by adults (a person becomes an adult at twenty-five years of age among the Guji people) for other adults. Its major literary forms are known in Oromo as gerarsa, qexala, gelelle, and faaruu loonii. Adults perform these oral literary forms either individually or addressing an audience, in different social and cultural contexts such as Middaa (social events to celebrate patriotism), Jila (ceremonial events), Agooda (cooperative work), and Eebbisa Loonii (rituals for honouring cattle). Only adults, both men are women, are legitimate participants in these events.

Events of this kind are not only common among Oromo-speaking people, but also among other Ethiopian groups such as the Amhara, Sidama, Gedeo, and Walayita peoples in different languages forms and under different names. For example, social events to celebrate patriotism are called Middaa among the Guji people, qondala among the other Oromo groups, and Anbessa Geday among Amharic speaking groups. Among the Guji and other ethnic groups, bravery is celebrated through the performance of these songs, and such cultural practices are perceived as honouring the heroism of an adult who managed to kill an elephant, a lion, or a buffalo. A person who killed one of these wild animals is considered a hero, acquires a high reputation in the eyes of all other men and women and is called Abba Middaa (meaning “a patriot”). Celebrations of such cultural practice are embellished through the performance of oral genres among all these different Ethiopian groups. Now, let us see these literary forms one by one.

The Gerarsa or Patriotic Song

The Guji-Oromo attach a deep value to bravery and reinforce it through singing the gerarsa, which is a popular praise genre. The genre is also to be found among the Amhara, Sidama, and Gedeo peoples in Ethiopia, albeit under different names. Among Amharic speakers, for example, the genre is called qarerto, though it shares many characteristics with the Oromo gerarsa, from performance context to style of delivery. Adult men sing the song in different social and cultural contexts, generally related to the accomplishment of an extraordinary achievement, such as killing a dangerous wild animal in a hunting expedition, killing an enemy during a war, producing large hectares of crops with a large herd of cattle, or enduring and surviving a difficult situation. Such accomplishments are seen as the outcome of bravery in Ethiopia, and the geerarsa promotes precisely the values of bravery, heroism, and physical prowess.

Men who accomplish such extraordinary achievements sing the song in the first person to tell the stories of their achievements and proclaim their heroism, generally as self-praise in front of others during social and cultural events. A geerarsa can also be sung about someone else, and in this case the performer honours a man in the audience. The gerarsa reflects the different level of honour attributed to individuals who accomplished heroic deeds. The level of honour varies with the achievement. For example, killing an elephant is considered more honourable than killing a lion. The elephant killer is called mataa midda (head of heroes) and is the first in the performance order. The patriots sing their own songs in turn, and the performance is embellished by ululations from the participants. The patriots sing the melody loudly while the participants (both men and women) appreciate and glorify them. The killer of an elephant takes the front stage and begins the performance by saying:

Someone who killed a buffalo is cattle, for he eats grass

Someone who killed a lion is a dog, for he eats flesh

Someone who killed an elephant is a patriot, and can sing loudly.

These are verses that someone who killed an elephant always uses to open their gerarsa. Speaking these lines, the head of heroes (the killer of an elephant) asserts his superiority and calls for public attention. Men who only killed a lion or buffalo are bound to honour such men and strive to achieve the same. Similarly, men who participated in war against enemies sing about the deeds they accomplished during the military confrontation. In such a context, a hero performs the song to praise a brave man and reject a coward, and gerarsa is performed by one person at a time in the presence of an audience. While a person is performing, the audience listens and responds by shouting the word ‘fight’ (lolee) five times at given intervals. The following transcript of gerarsa can be observed as an example.

Attendants: Fight (5x)

Singer: When a stone at Gerceloo1 rings (3x)

A fool thinks it is a bell

A brave has said Gerarsa

And revealed what is in his heart

He praised the brave and dismissed the coward

Attendants: Fight (5x)

Singer: When a man goes to war

His mother gets sad

When he comes back from war

She is delighted.

Attendants: Fight (5x)

Singer: Death is inevitable

One shouldn’t be afraid of it

One should fight and die

Attendants: Fight (5x)

Singer: A coward fears a shadow in the day

A brave man shows a lion’s eyelashes to his people

The word ‘fight’ comes at each break of the song and expresses the existence of a social consensus around the values of intrepidness, audacity, and military prowess. The last line in the first section of the song (‘He praised the brave and dismissed the coward’) and the last two lines at the end of the song (‘A coward man fears a shadow in the day/A brave man shows a lion’s eyelashes to his people’) reveal the important function of gerarsa in promoting this conception of heroic masculinity. The brave man is praised and celebrated, while the cowardly man is ridiculed and defamed. The recurrent themes of bravery, fighting, and war allude to the tradition of warfare in the Guji-Oromo and showcase the role of oral literature in reinforcing such values. ‘Brave’ designates a warrior, ‘fight’ indicates the actions of attacking, killing, and defeating the enemy, while the third word ‘war’ represents the whole situation that involves the brave warrior and his actions. The frequent appearance of these words, therefore, situates the song within the broader theme of heroism. Gerarsa is good at arousing emotion, reflecting feeling, and communicating messages elegantly. That is why adults perform the gerarsa as an artistic expression, to reinforce and sustain bravery and patriotism. They use the song to push people towards better social and cultural achievements, and to discourage social and cultural weaknesses. Children grow up watching and listening to adults perform the song, but they are not eligible to sing it until they become adults. Through this song, adults perpetuate these values to the succeeding generation. As a text, gerarsa embodies symbolic and imaginative expressions conveying ‘thick’ messages about Guji cultural and gender values. As performance, it involves diverse tones and attractive melodies that shape its identity and engage the audience. This shows that, similar to the other genres of Guji oral literature, gerarsa is characterized by aesthetic complexity.

The Qexala or Ceremonial Song

The qexala or ceremonial song is another genre performed and cherished by Guji-Oromo adults. This form of oral literature is also popular among the Sidama and Gedeo peoples of Ethiopia. It is performed more frequently than the gerarsa. The cultural context in which qexala is performed is known as jila or ceremony, which is a popular event in which only adults participate. Although several minor jilas are available at different social occasions, there are four major jila in one Gadaa period of eight years. These are the jila of Baallii kenna or power transfer; the jila of Laguubaasa, in which members of the Kuusa grade pass from childhood status to adulthood; the jila of Maqiibaasii or naming children; and the jila of jaarra utalli or blessing. The central element of these ritual ceremonies is the performance of the qexala. Participants in the ceremonies sing the qexala in different styles, and no ritual and ceremonial practice of Guji people can be complete without such a performance.

Important elements that distinguish qexala from gerarsa are the performance style, content, and function of the two genres. In the performance of gerarsa, the expression lolee, lolee (fight, fight) is frequently recited by the audience at certain points of the song. The qexala also has a call and response structure, but the response is a different expression, hoo, hoo which is a deep and sober melody to signify humility and respect for the supernatural power. The song is performed by a chorus of senior, high-ranking men. The singers stand in a group facing the same direction and walk slowly while performing the song. One singer leads by reciting lines of the song, and the other participants then respond all together with their own line. The performance is characterised by the participants’ gentle forward and backward movements, deep and homogenous melody, uniformity in clothing and gesture, as well as closeness and equality in group positions.

Fig. 7.2 Guji adults stand in a row singing a qexala song in a chorus. Author’s photograph.

The qexala is performed by adults in the Raba, Dori, Gada, Batu, and Yuba generations as a means of reinforcing the values of solidarity and peaceful relationships between people; between people and the natural environment; and between the people and supernatural powers. At the beginning and end of a social or cultural event, adults in the generational grades come together and perform the song as a sign of opening and conclusion and to thank the supernatural power. Members take turns in leading the performance, since they all are considered well-versed in the performance of the song. The following is an example of a qexala song often performed during cultural ceremonies of the Guji-Oromo:

|

Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: |

Our custom, hoo Our custom, our unity Our unity Our custom, our unity Our symbol Our custom, our unity My people, say ‘we are happy’ Our custom, our unity Our symbol Our custom, our unity Our custom is a symbol of our land. Hoo Hoo, haa, hoo (2x) Hoo Hoo, haa, hoo (2x) Hoo Hoo, haa, hoo (2x) Our culture looks great Hoo Hoo haa hoo (2x) It is in a great place Hoo Hoo haa hoo (2x) Let us celebrate it Hoo |

The leader recites the lines while walking in front of the group, and they walk behind the leader and recite in unison ‘hoo’ and ‘our custom our unity’. The performance is a demonstration of unity and cohesiveness between the leader and the group, as well as unity and cohesiveness within the group. It symbolises the value of solidarity and social harmony. The lyrics use phrases like ‘our custom’ and words expressing solidarity, unanimity, and peacefulness as key values of the Guji-Oromo society. ‘Hoo’ is recited in deep melody and signifies the honour and respect for supernatural powers.

The Gelelle or Work Song

The gelelle or work song of the Guji-Oromo is performed in the context of group work, known in Oromo as agooda. Working in a group is an important form of social networking and cooperation among the Guji-Oromo through which men create friendships and take turns at farming work. A group can consist of two to five men who perceive each other to be close friends. Members of a work group co-operate to enhance productivity and create a space for social interaction during planting, weeding, and harvesting. Men sing the gelelle when working in a group to motivate themselves to work harder. People believe that the gelelle is like an engine which fuels men to work quicker and longer. By using the song to praise each other, admire their surroundings and environment, and spur each other on, people revive their energies and build up endurance. The following is a gelelle song I collected on fieldwork. It is performed by an adult known as wellisa, meaning a clever lead singer. After each verse, the others shout ‘Hee’ to signify the agreement of the chorus with the lead singer. Like the ‘Hoo’ chorus cry in the Qexala, the ‘Hee’ cry in the Gelelle shows the chorus re-affirming the central and superior role of the higher powers in the social hierarchy.

|

Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: Chorus: Lead singer: |

You boys, how are you my brave ones? Hee Let me talk about you Hee How are you, brave men? Hee You would know your fame Hee I shall talk about you Hee Brave of braves, owners of coffee Hee Ho, my men Hee Men of great motivation Hee How are you, my men? Hee Men, defeated only by soil Hee How are you, my men? Hee Don’t get tired, work hard |

The song exemplifies the tradition of praising and energising one other through the performance of oral literature. Singing the gelelle encourages those engaged in agricultural work to build the endurance they need to survive through hardships. Here, oral literature serves as a tool to reinforce the values of physical resilience, labour, and productivity. It unleashes and sustains the moral stamina to work hard, reinforcing the importance of agricultural productivity for the people’s livelihood.

Weedduu Loonii or Cattle Songs

Cattle have a special place in both the culture and livelihood of the Guji-Oromo.22 They are respected and celebrated as valuable economic, social, and cultural assets. A household possessing many cows, bulls, and calves is identified in Oromo as warra jiidha (a wealthy household). Culturally, cattle are symbols of fertility and abundance and are part and parcel of many Guji cultural and spiritual practices. All ceremonies involve the ritual sacrifice of a bull (qorma qala), whose spilled blood symbolizes the cleansing of human sins. The ritual slaughter of a bull is therefore a symbolic way to communicate with supernatural powers. There are ceremonial occasions in which people sing songs to honour their cattle and express their love and respect for them. These celebrations involve drinking honey-beer and feasting with relatives and neighbours. The song, together with the honey-beer, raises the spirits of the participants and gives colour to the celebration. The cattle song is performed by any man and woman, usually during spring season as this is a time when the grass begins to grow and cattle become happy. Men and women sing the cattle song when they milk the cows, release cattle from shelter to the grazing field, lead cattle to the water pond, and lead cattle from the grazing field to shelter. When they lead cattle from shelter to the grazing field and from the grazing field to shelter, they sing songs such as the following.

Lizards on mountains

Cows of hundred calves

Abundant in the field are my cattle

They save me from trouble

Those who love cattle are cheerful

They are rich and plentiful

Where cattle are abundant

One’s milking pot is always wet

It is good to sing for cattle

For it makes me humble

The song shows that the relationship between people and their cattle is based on a reciprocal exchange, with the people caring for cattle and the cattle providing the people with economic and cultural benefits. This oral genre celebrates the role of cattle in society, reinstates the importance of cattle husbandry, and transmits this value to their children.

In the performance of the genres of oral literature presented above, the performer manages the time, place, style, and purpose of the performance, which also differentiate one genre from the other. For example, the gerarsa is performed at events celebrating bravery that take place within homes or home compounds. The qexala is performed during the Gadaa ceremonies that take place at ceremonial places or ardaa jila, whereas the Gelelle is sung while working. Performances vary in tones, melodies, gestures, and messages across the genres. These features indicate the diversity and complexity in places, times, and styles of performance across the oral genres. The oral songs presented above are characterized by tonal variation, improvisation, whimsical facial expression, vivid body movements and gestures, repetition, and dramatic body movements. The literariness of the oral songs emanates from these qualities, which in turn contributes to the diversity and wide range of written literature, and clarifies the strong link between oral and written literature.

Oral Genres that Adults Perform with Children

Among the Guji people, childhood covers the Dabballe and Qarre generational grades, which span from birth to the age of sixteen. Among children, oduuduri (myths and legends) and duriduri (folk tales) are the two popular genres that involve the process of telling and listening.23 The Guji people consider these oral genres a central component of their culture and a vehicle of the transmission of survival skills, customary practices, norms, and values from the past generation (the ancestors) to the future generation (children) via the present generation (grandparents and parents). Grandparents and parents, who are seen as the active generations mediating between the past and the future, play key roles in the transmission of oral literary forms.

This category represents oral literary forms that adults perform for children as a means of entertaining, socialising, and educating them. Oring and Tucker call ‘folklore for children’ all the different oral narratives (tales, songs, rhymes, riddles) that adults perform for children as part of generational knowledge transfer.24 According to McMahon, these genres are produced by adults for children in order to develop the children’s knowledge of their social world and to prepare them to become productive societal members in their adult lives.25 Parents use oral narratives to equip their children with folk knowledge and to enable them to understand their social environment through entertainment.26 The purpose of these narratives is therefore two-fold: socialisation and entertainment.27

Among the Guji-Oromo, the duriduri or folk tale is a popular oral literary genre that adults perform for children. Storytelling draws children and adults together. When adults tell folk tales to children, the children sit around them and listen to the tales with courtesy and curiosity. In such a context, children are learners and adults are teachers, and generally the performance has a didactic purpose. Storytelling at home is initiated by the children, as they are often the ones who ask their parents or grandparents to tell them a story. Parents or grandparents activate their memory and remember and reconstruct the oral tradition from their oral repertoire through performance. The children, on the other hand, accept storytelling as a means of entertainment and listen attentively to their parents or grandparents, but also actively intervene to ask for clarifications at the end of the story. In such cultural interactions, adults hold real power and set norms for children.

The following extract is taken from my notes of participant observation at the home of Uddee Netere, a seventy-year-old man and a resident of Bunata Village. At Uddee Netere’s home, I observed children initiating the storytelling session at night time. In the interval between coffee and dinner, Uddee Netere’s ten-year-old grandson, Galchu, asked Uddee to tell him a folk tale. Galchu went to his grandfather and murmured in his ear, ‘tell us the tale that you told us the other day’. The grandfather smiled and nodded his head to show his assent. Then, Galchu and his siblings gathered around their grandfather, who began by saying, ‘Folk tales of the maatti, birds of the hill; it is the hill that cries and the fool that shies’. This is the expression the Guji people use to begin storytelling and call for the attention of listeners. Then Uddee continued:

Once upon a time, a fox and a hawk were living together. One day, they were starving and they killed a rat to eat. However, the hawk decided to snatch the rat for himself and fly away to a big, tall tree. The hawk sat on the big tree with the rat in his mouth. The fox became very angry at the greedy act of his friend. He devised a trick to get back his delicious rat. He killed a small frog, went under the tree on which the hawk was sitting with the rat in his mouth, called to him, ‘Hello Hawk, I have got a more delicious one, look at it’, and showed him the frog from the ground. The greedy hawk was keen on the frog and opened his mouth to speak to the fox. When the hawk opened his mouth, the rat dropped down to the ground and the fox got it back. The hawk lost what he owned when he longed for something more, it was said.

The children responded to the tale with different actions and behaviours. Some of them smiled, others murmured as their grandfather spoke. At the end, the children laughed at the ignorance of the hawk and were surprised by the trickery of the fox against the hawk. The grandfather told them that the tale teaches that if you are too greedy, you will lose everything. In the performances of this tale, both children and adults acted as interlocutors but maintained distinct hierarchical roles. Parents are transmitters of norms and values and children learn these norms and values through their participation in the oral performances. In the context of storytelling, adults respect the interests and requests of their children. Children, in turn, respect adults and pay due attention to their instructions. They do what adults tell them to do and sit where adults tell them to sit. Through such performances, adults acquaint children with Guji ancestral knowledge, which includes harmonious relationships between adults and children as well as customary values, norms, and survival skills. Participation in such oral performances at home involves curiosity, respect, trust, appreciation, and affection. Children are curious to hear oral literary forms from parents, and parents are curious to teach their children through oral literature. Thus, children invest deep attention and value in the oral performance with adults, and adults use this opportunity as an occasion to equip their children with the cultural codes regulating intergenerational relationships.

Children’s Oral Genres

Children’s oral literature refers to the folk knowledge that circulates among two or more children, usually without or with limited involvement of adults.28 It includes the folk tales, riddles, and songs that children produce and reproduce for one another in different social and cultural contexts. In these performances, children are the central agents who initiate, reproduce, and transmit oral literary forms. In other words, in the context of children’s oral literature, children are both tellers and receivers of their folk culture.29

The concept of children’s oral literature emerged at the end of the nineteenth century, in parallel with other significant changes in the way childhood was conceptualised. Children started being seen as social actors with their own culture as well as inhabiting the social world they shared with adults.30 The interest in children’s oral literature emerged within this paradigm, allowing us to see children not only as receivers of oral culture but also as producers and transmitters.31 In the study of children’s oral literature, children are understood as having their own collective traditions. Within their group, children create an interactive fabric of activities out of their immediate social and natural environments with minimal involvement from adults.32 These group traditions importantly foster children’s social and cognitive development. In short, children’s participation in the performance and circulation of oral genres is significant, allowing us to see children themselves as literary creators. Oral literature or orature is not, therefore, the preserve of adults alone. Nor are children always passive receivers of oral narratives imparted by their elders, but can be pivotal agents in the creation and transmission of orature. Among the Guji-Oromo, duriduri (folk tales), hibboo (riddles), and weedduu (folk songs) are the most important forms of children’s oral literature. These oral literary forms are performed in the social contexts pertaining to children and young people: family time at home, herding cattle in the fields, and playtime at school and in the neighbourhood.

Fig. 7.3 Guji children performing storytelling in a cattle herding field.

Author’s photograph.

In these dynamic contexts of work, study, and play, children form peer relationships and perform the different genres of oral literature as part of their culture of play. Children may learn a folk tale from their siblings or parents and then share it in the cattle-herding fields and school compounds. They may also learn a folk tale from children in the fields or school compounds and then share it with their siblings at home. Playtime at home gives children the opportunity to learn a variety of folk tales as it involves siblings who participate as tellers, listeners, and interpreters. Parents can also be involved as audience members, inverting the common hierarchy of storytelling that sees parents as storytellers and children as their audience. For example, I witnessed Roba, a ten-year-old boy, telling the following folk tale to his siblings and parents. He had learned the tale from his peers at school:

Once upon a time, a cat’s child and a rat’s child were friends and used to play with each other. One evening, the mother cat asked her child, ‘My child, where did you stay during the day?’ The child replied, ‘I was playing with rat’s child’. The mother said to her child, ‘Rats are delicious food. Catch her and eat her’. The child replied, ‘Ok, I will do that tomorrow’. The mother rat also asked her child, ‘My child, where did you stay during the day?’ The child replied, ‘I was playing with cat’s child’. The mother rat said to her child, ‘My child, how can you play with your enemy? Cats are our enemies. They eat us. Don’t do that again’. The next day, the cat’s child went to the playground early in the morning and was waiting for the rat’s child. When she came out of her house, the rat’s child saw the cat’s child waiting for her. The cat’s child called her, ‘Come, let us play’. Then, the rat’s child replied, ‘My mother has told me what your mother told you. Now we know each other’. After saying this, the rat’s child went back inside her home, it was said.

In this way, children share oral literature at home, in the cattle-herding fields, at school, and in village neighbourhoods. Even though adults tell folk tales to children with didactic purposes, the children comprehend and express them in their own ways when it is their turn to re-tell them. Roba told this story to his siblings and parents vividly, creatively and in a captivating manner. His siblings listened attentively, interrupted him to ask questions, and responded to the story with smiles and sounds of surprise. This shows that, in their performance of folk tales, children take liberties in relating the events, names, moods, and actions of characters, and react freely to what is being told to them. They say what they want to say, act in the way they want to act, behave in the way they want to behave, sometimes laugh loudly, sometimes stand up and shout, sometimes stop the teller and correct him/her, sometimes help him/her when he/she forgets the order of events or fails to remember specific stories. Children’s performance of folk tales differs from that of adults in the styles used by the performer. Storytelling by adults entails complete opening terms like ‘once up a time’, the closing term ‘it was said’, candid mimicry, vivid gestures and intonation, which make the tale imposing and meaningful. By contrast, children often begin telling a story without the opening term ‘once upon a time’ and the closing term ‘it was said’, and the mimicry, gestures and intonation in their performance are more creative and artistic than those of adults. This shows the diversity and complexity in in the local oral literary forms which, in turn, contribute to the richness of world literature.

These days, children also have the opportunity to listen to storytelling and songs from mass media sources such as radio and television. My encounters in a remote rural village testify to this new trend in oral literature circulation. I approached a group of children performing a song in a grazing field and asked what they were singing. The children told me that they were playing wadeb, which is the name of a song popular with Tigrinya-speaking children in the northernmost part of Ethiopia. I asked the children to perform the song again, and they agreed. One of the children performed the song with a loud and smooth melody:

|

Wadeb, wadeb Wadeb Ahadu Wadeb Kilitte Wadeb Seliste Wadeb Arbate Wadeb Amishite Wadeb Shidishite |

Wadeb, wadeb Wadeb, one Wadeb, two Wadeb, three Wadeb, four Wadeb, five Wadeb, six |

I was surprised that the song was in Tigrinya, a language spoken very far away from the land of the Guji. I asked the children what the language of the song was, and they did not know. I also asked how they had learned the song, and they replied that they had learned from each other. I continued to investigate how the children had come across the song and learned that, sometime in the past, a child from the village had gone to a nearby town and watched the song on television. The child came back to his village and shared the song with his friends. The song was later circulated among the children in the village and became part of children’s repertoire of oral literature. This instance shows the role of mass media in the circulation of children’s oral literature, including across languages. In other words, this example demonstrates that children’s oral literature from the northern part of Ethiopia was learned by children in the southern part of the country through television broadcasting. Television allowed Oromo-speaking children to learn the oral traditions of Tigrinya-speaking children. This reality reflects the new ways in which oral literature can cross different cultures and geographies, bypassing adults and language barriers. This trend may bring children from different cultures and geographies together and allow them to transmit their knowledge and values across long distances. Mass media, like schools and workplaces, helps children share their oral traditions and use them as a means of understanding each other’s skills, knowledge, and experiences, and learning about the presence of different cultures and languages in the country.

Conclusion

Among the Guji, mastery of oral genres depends on age and on personal skills. Children become versed in the performance of duriduri, hibbo, and wedduu, and when they grow up, they learn how to perform the gerarsa, qexala, weeddu loonii, and jecha. Within this broad generational distribution of oral genres, individuals partake in oral literature based on their personal talents and inclinations. Some people can perform folk songs better than they do folk tales and riddles, others are better at performing folk tales and riddles than folk songs. Some people may remember many folk tales but not as many folk songs, others may have memorised an extensive repertoire of folk songs but be less versed in folk tales. During performances of these oral literary forms, people who do not have adequate knowledge and performance ability sit or stand by the side, watching the performance and learning from it.

Oral literature, as this chapter has shown, has both an intra-generational and an inter-generational circulation. Different oral genres are shared either among adults only, among children only, or across generations. Contrary to the widespread assumption that oral traditions are the preserve of the elders, this chapter has shown that children are active agents of oral circulation and preservation. They acquire oral literature from adults and then share it with other children, or they learn it from other children and then share it with adults. As a result, oral literature reflects the culture, values, and social practices not only of adults but also of children. It is not a static and fixed repository of cultural authenticity, but a dynamic, modern, and aesthetically complex tool of communication and knowledge sharing. It is memorised, circulated, and performed not only by elders, but also by children. Through these forms of artistic expression, adults teach one another and learn from one another, and children also learn from one another and teach one another. Children have a significant literary influence on the adults around them, encouraging them to memorise certain oral texts, thus connecting adults with children’s culture. The oral literary forms that children and adults perform together serve as mutual socialisation into each other’s culture. Inter-generational exchanges are as rich as intra-generational ones: adults educate children, but also learn from them, and children learn from adults, but also teach them. Studying oral literature helps us capture the dynamic nature of the relationship between adults and children among the Guji, and how it has changed and keeps changing based on broader processes of social and economic transformation.

By producing and reproducing different oral genres, children contribute to the continuity of oral traditions. In fact, the socio-cultural contexts in which adults perform oral literary forms, such as family playtime and neighbourhood social events, are slowly disappearing; some significant forms of oral literature are no longer lived culture for adults as a result but become part of what can be called a ‘culture of memory’. This implies that people connect themselves to their past cultural practices through memory. But if some forms of oral literature may partly or fully disappear from people’s everyday practices and become remembered as a culture of the past, such change is less observable in the culture and everyday lives of children. In the past, there was no distinction between the vibrancy of the oral practices of adults and children, but these days, folk performances are receding among adults and are instead retained by children. For example, folk tales, riddles, and cattle songs continue to be active elements of children’s play culture. This is because children have alternative access to forms of oral literature through school books, mass media (mainly children’s programs on radio and television), and because of an emerging interest in integrating oral literature with learning practices in schools.33 Therefore, if we want to look for orature in Guji society, we need to look at children’s social interactions.

This located study has helped to make children visible as agents and producers of oral literature. It has drawn attention to the importance of inter-generational as well as intra-generational transmission. Through a located ethnography of Guji-Oromo oral genres, it has highlighted its multiple channels of access and transmission, as well as processes of adaptation showing how oral literature is dynamic, adaptable, and able to evolve across changing social and cultural contexts. Today, several socio-cultural milieus that are the basis for the performance of oral literary forms are undergoing change. For example, children’s spaces of play interaction with adults are decreasing, as the division of labour by age—which sees children work in different spaces from adults—has become common. Following the expansion of schooling in rural areas, children’s time for play and peer interaction in cattle-herding places has also become shorter. Oral traditions among the Guji are set to continue for generations, but we may witness a change in transmission and circulation. Children’s increasing access to school, children’s television and radio programmes, and new media (like Facebook and digital games) may make the circulation of oral literature increasingly the responsibility of children and younger generation. As a result, the top-down, hierarchical transmission patterns from adults towards children may decline in importance, leaving more room in the coming years for intra-generational transmission among children and bottom-up inter-generational transmission from children to adults. Such contexts may ensure the wider circulation of oral literature and give rise to new forms that appeal to children’s mediated lived experiences. As a result, oral literature can be considered as a primary literary culture that contributes to the delocalisation, sophistication, and dynamism of world literature.

Bibliography

Alemu, Abreham, ‘Oral Narratives as Ideological Weapon for Subordinating Women: The Case of Jimma Oromo’, Journal of African Cultural Studies, 19.1 (2007), 55–80, https://doi.org/10.1080/13696810701485934

Argenti, Nicolas, ‘Things that Don’t Come by the Road: Folktales, Fosterage, and Memories of Slavery in the Cameroon Grassfields’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 55.2 (2010), 224–254, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417510000034

Beriso, Tadesse, ‘The Pride of the Guji-Oromo: An Essay on Cultural Contact Self-Esteem’, Journal of Oromo Studies, 11.1–2 (2004), 13–27, https://oromostudies.org/wp-content/uploads/jos/JOS-Volume-11-Number-1_2-2004.pdf

Braukämper, Ulrich, ‘The Correlation of Oral Traditions and Historical Records in Southern Ethiopia: A Case Study of the Hadiya/ Sidamo Past’, Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 11.2 (1973), 29–50, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41988257

Clarunji Chesaina, Oral Literature of the Embu and Mbeere (Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers, 1997).

Debelo, Asebe and Tadesse J. Jirata, ‘“Peace Is Not a Free Gift”: Indigenous Conceptualisations of Peace among the Guji-Oromo in Southern Ethiopia’, Northeast African Studies, 18.1–2 (2018), 201–230, https://doi.org/10.14321/nortafristud.18.1-2.0201

Debsu, Dejen N., ‘Gender and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: An Ethnographic Analysis of Guji-Oromo Women’s Customary Rights’, African Study Monographs, 30.1 (2009), 15–36, https://repository.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2433/71111/1/ASM_30_15.pdf

Eder, Donna, Life Lessons through Story Telling: Children’s Explorations of Ethics (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010).

Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission, ‘Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census: Population Size by Age and Sex’ (Addis Ababa: UNFPA, 2008), https://www.ethiopianreview.com – 2007 Census

Finnegan, Ruth, Oral Tradition and Verbal Arts (London: Routledge, 1992).

——, The Oral and Beyond: Doing Things with Words in Africa (Oxford: James Curry, 2007).

Gemeda, Esthete, ‘African Egalitarian Values and Indigenous Genres: The Functional and Contextual Studies of Oromo Oral Literature in a Contemporary Perspective’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Southern Denmark, 2008).

Jirata, Tadesse, J., ‘Folktales, Reality, and Childhood in Ethiopia: How Children Construct Social Values through Performance of Folktales’, Folklore, 129.3 (2018), 237–253, https://doi.org/10.1080/0015587X.2018.1449457

——, ‘Oral Poetry as Herding Tool: A Study of Cattle Songs as Children’s Art and Cultural Exercise among the Guji-Oromo in Ethiopia’, Journal of African Cultural Studies, 29.3 (2017), 292–310, https://doi.org/10.1080/13696815.2016.1201653

——, ‘Children and Oral Tradition among the Guji-Oromo in Southern Ethiopia’ (unpublished PhD thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2013), https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/269081/638430_FULLTEXT02.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

Jirata, Tadesse J. and Jan Ketil Simonsen, ‘The Roles of Oromo-Speaking Children in Storytelling Tradition in Ethiopia’, Research in African Literatures, 45.2 (2014), 135–149, https://doi.org/10.2979/reseafrilite.45.2.135

Johnson, John W., ‘Orality, Literacy, and Somali Oral Poetry’, Journal of African Cultural Studies’, 18.1 (2006), 119–136.

Kidane, Sahlu, Borana Folktales: A Contextual Study (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2002).

Legesse, Abiyot, Gadaa: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society (New York: Free Press,1973).

McMahon, Felicia R., Not Just Child’s Play: Emerging Tradition and the Lost Boys of Sudan (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007).

Mello, Robin, ‘The Power of Storytelling: How Oral Narrative Influences Children’s Relationships in Classrooms’, International Journal of Education and the Arts, 2.1 (2001), n.p., http://www.ijea.org/v2n1/

Mouritsen, Flemming, ‘Child Culture- Play Culture’ in Childhood and Children’s Culture, ed. by Flemming Mouritsen and Jens Qvortrup (Denmark: Denmark University Press, 2002), pp. 14–42.

Nyota, Shumirai and Jacob Mapara, ‘Shona Traditional Children’s Games and Play, Songs as Indigenous Ways of Knowing’, Journal of Pan African Studies, 2.4 (2008), 189–202, https://www.jpanafrican.org/docs/vol2no4/2.4_Shona_Traditional_Children.pdf

Okpewho, Isidore, African Oral Literature: Backgrounds, Character, and Continuity (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992).

Oring, Elliott, ‘Folk Narratives’ in Folk Groups and Folklore Genres: An Introduction, ed. by Elliott Oring (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1986), pp. 121–145.

Sackey, Edward, ‘Oral Tradition and the African Novel’, Modern African Studies, 37.3 (1991), 389–407.

Schmidt, Nancy J., ‘Collection of African Folklore for Children’, Research in African Literatures, 2 (1971), 150–167.

Sutton-Smith, Brian, ‘Introduction: What is Children’s Folklore?’ in Children’s Folklore: A Source Book, ed. by Brian Sutton-Smith, Jay Mechling, Thomas W. Johnson, and Felicia R. McMahon (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1995), pp. 3–10.

Tasew, Bayleyegn, ‘Metaphors of Peace and Violence in the Folklore: Discourses of South-Western Ethiopia: A Comparative Study’ (unpublished PhD thesis, Vriji University Amsterdam, 2009).

Tucker, Elizabth, Children’s Folklore: A Handbook (New York: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008).

van Damme, Wilfried, ‘African Verbal Arts and the Study of African Visual Aesthetics’, Research in African Literature, 31.4 (2000), 8–20.

Van de Loo, Joseph, Guji-Oromo Culture in Southern Ethiopia (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1991).

Yeseraw, Abebe, Tadesse Melesse and Asrat Dagnew Kelkay, ‘Inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in the New Primary and Middle School Curriculum of Ethiopia’, Cogent Education, 10.1 (2023), https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2173884

1 Areri Roba, personal communication.

2 Tadesse J. Jirata, and Jan Ketil Simonsen, ‘The Roles of Oromo-Speaking Children in Storytelling Tradition in Ethiopia’, Research in African Literatures, 45.2 (2014), 135–149.

3 See Abreham Alemu, ‘Oral Narratives as Ideological Weapon for Subordinating Women: The Case of Jimma Oromo’, Journal of African Cultural Studies, 19.1 (2007), 55–80; Nicolas Argenti, ‘Things that Don’t Come by the Road: Folktales, Fosterage, and Memories of Slavery in the Cameroon Grassfields’, Comparative Studies in Society and History, 55.2 (2010), 224–254; Isidore Okpewho, African Oral Literature: Backgrounds, Character, and Continuity (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992).

4 Ulrich Braukämper, ‘The Correlation of Oral Traditions and Historical Records in Southern Ethiopia: A Case Study of the Hadiya/ Sidamo Past’, Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 11.2 (1973), 29–50; John W. Johnson, ‘Orality, Literacy, and Somali Oral Poetry’, Journal of African Cultural Studies’, 18.1 (2006), 119–136; and Sahlu Kidane, Borana Folktales: A Contextual Study (Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2002).

5 See Bayleyegn Tasew, ‘Metaphors of Peace and Violence in the Folklore: Discourses of South-Western Ethiopia: A Comparative Study’ (unpublished PhD thesis, Vriji University Amsterdam, 2009).

6 Ruth Finnegan, The Oral and Beyond: Doing Things with Words in Africa (Oxford: James Curry, 2007).

7 Eshete Gemeda, ‘African Egalitarian Values and Indigenous Genres: The Functional and Contextual Studies of Oromo Oral Literature in a Contemporary Perspective’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Southern Denmark, 2008); Wilfried van Damme, ‘African Verbal Arts and the Study of African Visual Aesthetics’, Research in African Literature, 31.4 (2000), 8–20.

8 Ruth Finnegan, Oral Tradition and Verbal Arts (London: Routledge, 1992).

9 Tadesse J. Jirata, ‘Oral Poetry as Herding Tool: A Study of Cattle Songs as Children’s Art and Cultural Exercise among the Guji-Oromo in Ethiopia’, Journal of African Cultural Studies, 29.3 (2017), 292–310.

10 Clarunji Chesaina, Oral Literature of the Embu and Mbeere (Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers, 1997); Okpewho, African Oral Literature; Edward Sackey, ‘Oral Tradition and the African Novel’, Modern African Studies, 37.3 (1991), 389–407.

11 Jirata and Simonsen, ‘Oromo-Speaking Children’.

12 Okpewho, African Oral Literature; Sackey ‘Oral Tradition’.

13 Dejen N. Debsu, ‘Gender and Culture in Southern Ethiopia: An Ethnographic Analysis of Guji-Oromo Women’s Customary Rights’, African Study Monographs, 30.1 (2009), 15–36; Tadesse J. Jirata, ‘Folktales, Reality, and Childhood in Ethiopia: How Children Construct Social Values through Performance of Folktales’, Folklore, 129.3 (2018), 237–253.

14 Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission, ‘Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census: Population Size by Age and Sex’ (Addis Ababa: UNFPA 2008), pp.1–113.

15 Tadesse Beriso, ‘The Pride of the Guji-Oromo: An Essay on Cultural Contact Self-Esteem’, Journal of Oromo Studies, 11.1–2 (2004), 13–27.

16 Joseph Van de Loo, Guji-Oromo Culture in Southern Ethiopia (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1991).

17 One Gadaa Council administers for eight years and hands over the baallii (authority) to the next Gadaa Council every eight years. See Abiyot Legesse, Gadaa: Three Approaches to the Study of African Society (New York: Free Press,1973); Van de Loo, Guji-Oromo Culture; Tadesse J. Jirata, ‘Children and Oral Tradition among the Guji-Oromo in Southern Ethiopia’ (unpublished PhD thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 2013); Beriso, ‘The Pride of the Guji-Oromo’.

18 Van de Loo, Guji-Oromo Culture; Beriso, ‘The Pride of the Guji-Oromo’.

19 Asebe R. Debelo and Tadesse J. Jirata, ‘“Peace Is Not a Free Gift”: Indigenous Conceptualisations of Peace among the Guji-Oromo in Southern Ethiopia’, Northeast African Studies, 18.1–2 (2018), 201–230.

20 Jirata ‘Children and Oral Tradition’; Jirata, ‘Oral Poetry as Herding Tool’.

21 Jirata, ‘Oral Poetry as Herding Tool’.

22 Jirata, ‘Oral Poetry as Herding Tool’.

23 Jirata ‘Children and Oral Tradition’; Jirata, ‘Oral Poetry as Herding Tool’; Jirata, ‘Folktales, Reality, and Childhood’.

24 Elliott Oring, ‘Folk Narratives’ in Folk Groups and Folklore Genres: An Introduction, ed. by Elliott Oring (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1986), pp. 121–145; Elizabeth Tucker, Children’s Folklore: A Handbook (New York: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008).

25 Felicia R. McMahon, Not Just Child’s Play: Emerging Tradition and the Lost Boys of Sudan (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2007).

26 Nancy J. Schmidt, ‘Collection of African Folklore for Children’, Research in African Literatures, 2.2 (1971), 150–167.

27 Brian Sutton-Smith, ‘Introduction: What is Children’s Folklore?’ in Children’s Folklore: A Source Book, ed. by Brian Sutton-Smith et. al (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1995), pp. 3–10.

28 Tucker, Children’s Folklore.

29 Jirata, ‘Children and Oral Tradition’; Sutton-Smith, ‘What is Children’s Folklore?’; Finnegan, The Oral and Beyond.

30 Tucker, Children’s Folklore.

31 McMahon, Not Just Child’s Play; Flemming Mouritsen, ‘Child Culture- Play Culture’ in Childhood and Children’s Culture, ed. by Flemming Mouritsen and Jens Qvortrup (Denmark: Denmark University Press, 2002), pp. 14–42.

32 Shumirai Nyota, and Jacob Mapara, ‘Shona Traditional Children’s Games and Play, Songs as Indigenous Ways of Knowing’, Journal of Pan African Studies, 2.4 (2008), 189–202; Robin Mello, ‘The Power of Storytelling: How Oral Narrative Influences Children’s Relationships in Classrooms’, International Journal of Education and the Arts, 2.1 (2001); Donna Eder, Life Lessons through Story Telling: Children’s Explorations of Ethics (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010).

33 Abebe Yeseraw, Tadesse Melesse & Asrat Dagnew Kelkay, ‘Inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in the New Primary and Middle School Curriculum of Ethiopia’, Cogent Education, 10.1 (2023), https://www.doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2173884