9. Two Tracks

Stories of the Destinies of Two Performative Oratures

©2025 Sadhana Naithani, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0405.09

Introduction

The relationship between orality and writing is an enigmatic one. It is generally assumed that oral narratives, songs, and other creative texts do not have anything to do with writing unless they are ‘collected’ and ‘textualized’ by folklore collectors and scholars. All modern folklore collectors have perpetuated this image ever since the brothers Wilhelm and Jakob Grimm published their collection of German folk tales in 1812. In Grimms’ depiction, oral narratives were like plants that had weathered many storms over the ages and finally, through the work of the Brothers, had come to find a new life in print. This process of transformation was then repeated in many countries and everywhere it unleashed a cultural process with political overtones. In the second half of the nineteenth century, this process of collecting orality and textualizing it became the core of the cultural politics of the British Empire. Textualized orality became the key to understanding, controlling and representing the colonized without reference to the processes of collection and translation themselves. In the process, orality became inextricably connected with tradition, while writing was connected with the modern. This perception still holds. It would not be wrong to say that, in the popular perception, orality belongs to an age gone by or that it is only to be found in some far-flung areas and among peoples not yet touched by modernity. This chapter concerns itself with two oratures that defy these popular perceptions about orality and its relationship with writing and tradition, and allow us to propose that they are part of world literature. Both are contemporary because they are regularly performed, and both have their separate histories of performance. I consider them ‘oratures’ because of their unique relationship to writing and to textuality. In the first case, people believe that its text originated in writing, but the written text got lost. The second case is based on well-known texts that were written down long ago, but its identity comes from the oral performance.

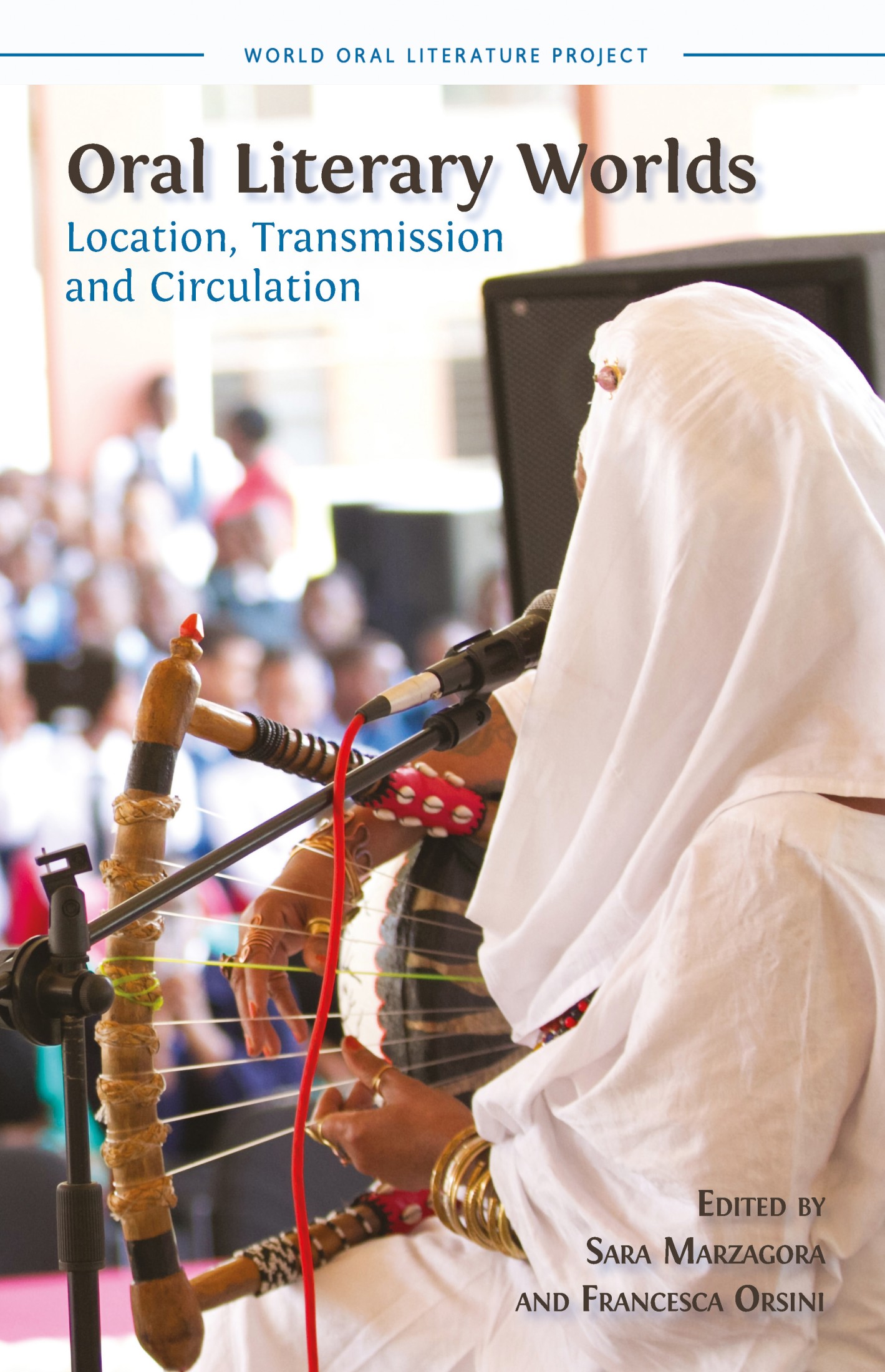

The first orature—Pandun ke Kade (Stories of Pandavs), performed by Muslim Jogis of Mewat—is based on research I carried out in 2009–2010 and on continued contact and communication with the performers. The primary research was undertaken in collaboration with film maker Sudheer Gupta and is encapsulated in a documentary film titled Three Generations of Jogi Umer Farukh, which should be seen as an audio-visual reference to this chapter.1 There are many videos of the performers available on the internet; I recommend watching the TedX presentation by Omer Mewati (Umer Farukh) and a performance titled ‘Bhapang Jugalbandi’.2 My research for the second orature, dastangoi (storytelling), started in January 2019 and is ongoing. The information here is mainly based on conversations with performers Mahmood Farooqui and Poonam Girdhani in New Delhi. Both performers have several videos on YouTube and on social media. These should also be watched for an independent appraisal of my analysis.3

Oratures, Performance, and Folklore

Methodologically, I study oratures and their changing history of performance. The study of performance is an established field in several disciplines, but I derive my perspective and method from the field of folkloristics. While the study of folklore was always aware of ‘performance’—because there was no other way of collecting folklore except through performance—analysis remained centred on the texts. For nineteenth-century folklorists, performance was something they viewed, but they were unable to bring it to their readers. Edwin Smith and Andrew Dale were two British collectors of folklore in Northern Rhodesia in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who were sensitive to the loss of performance details in the printed versions:

In order to hear these folk-tales effectively, one must hear them in their native setting. […] Overhead is an inky-black sky dotted with brilliant stars, a slight breeze is moving the tops of the tress, and all is silent save the regular gurgling noise of the calabash pipes, as the men sit or lie around the numerous camp fires within the stockade. Then the narrator will refill his pipe, and start his story: ‘Mwe wame! (Mates!)’, and at once they are all attention. After each sentence he pauses automatically for the last few words to be repeated or filled in by the audience, and as the story mounts to its climax, so does the excitement of the speaker rise with gesture and pitch of voice […]. To reproduce such stories with any measure of success, a gramophone record together with a cinematograph picture would be necessary. The story suffers from being put into cold print, and still more does it suffer in being translated into the tongue of a people so different in thought and life.4

Today, we have left the gramophone and cinematograph behind, and the audio-visual documentation of performance has become easy and necessary. The history of technology has deeply influenced the study of performance, but folklorists recognize that performance includes more than just the performers. It is a 360-degree study of the performance, the performers and the audience, and the performed text is yet another dimension that defines the performers and the audience. Since the 1970s, the study of folklore performances has grown tremendously. As Richard Bauman puts it,

The foundations of performance-oriented perspectives in folklore lie in the observations primarily of folktale scholars who departed from the library- and archive-based philological investigations that dominated folk narrative research to venture into the field to document folktales as recounted in the communities in which they were still current.5

Several approaches have emerged since the beginning of the nineteenth century. From the romantic notions of people as ‘natural performers’ to seeing the performance as ‘deep play’ in anthropology, to current studies of performance of erstwhile oratures as located in contemporary reality, the study of performance has matured in many ways.6

I understand oratures as oral texts with well-defined and stable poetic structures and an equally well-established and well-defined genre of performance. This implies that, while being oral, they have maintained structural and narrative continuity. On the one hand, the concept of orature brings them closer to literary texts, but on the other hand their fluidity and adaptability to different contexts and audiences are also recognized. Additionally, such texts have always travelled and changed their appearance according to their location. In several cases they made their transition to written texts long ago. All these features make oratures part of world literature.

I therefore propose a study of oratures that is multi-medial and inter-disciplinary. It needs to be multi-medial because oratures are no longer only oral, performed in face-to-face settings. They are increasingly disseminated through technology, and even face-to-face performances are recorded on camera and then circulated via the internet as edited or unedited shows. This shift does not merely change the mode of communication, but creates new networks of communications between performers, performance, performance-texts, performance-contexts and the audience. These new networks of communication require to be studied separately. As a correlate, world literature cannot only concern itself with the historical folklore or written oratures and their circulation in print, but needs to include the other networks and technologies within its broader imagination of texts and circulation.

The study of oratures must be interdisciplinary, as its texts require linguistic and philological approaches, while the performance is conditioned by social and historical factors. We will see in the following how the integrity of performers and performance-text is rendered tenuous by historical conditions, and change cannot be merely explained away as dilution or corruption of a traditional paradigm.

Pandun ke Kade and the Muslim Jogis of Mewat

The first orature under discussion here is the heritage of a Muslim community of performers called Muslim Jogis, who belong to the Mewat region of the state of Rajasthan in India. By several accounts, the community has a history that spans five to six centuries.7 Interestingly, the oratures they perform are rooted in the epics and religious lores of the Hindus. Pandun ke Kade is a shorter version of one of the two major Indian epics, the Mahabharata. While it is not possible to give a definite answer as to how Hindu texts came to be performed by Muslim performers, it can perhaps be explained as a liminal tradition between Islam and Hinduism in India.8 The conversion to Islam in medieval Rajasthan produced such alignments at various levels. In the case of performers, one may surmise that they adopted a new religion but continued their professional practice. The Muslim Jogis of Mewat perform two kinds of texts: narrative songs about the relations between Hindu god Shiva and his spouse Parvati, and an epic. The epic they perform is called Pandun ke Kade and it is known to have been composed by a local Muslim poet of the sixteenth century called Saidullah. This composition was a written text, which became popular through the oral narrations by the Jogis. In other words, the written text was entrusted to memory, and slowly its written documentation disappeared. The text itself did not disappear, though, as it continued to be performed. In fact, an entire tradition grew around it, raising the questions: at which time of the year it will be performed, who will sponsor the narration, who will hear it, and, of course, who will perform it?

The Jogis gained a monopoly over the right to perform Pandun ke Kade. We do not know whether their right was ever contested, whether the poet wrote just for them, or whether they emerged as a group once they received this text. Whatever the process, the sixteenth-century poet passed away but his text continues to exist. And not only the text, but reference to the written document, the orature, is also continuously made orally, although it is not to be found anywhere. It is a classic case of orality making the written redundant, instead of the other way around. The community of Jogis gained a professional identity through the text and its performance: they became known as the group of people who play a one-stringed instrument called bhapang and perform in villages and temples in the region. They continued to pass the text on to the next generation through memory.

The Jogis’ social identity was that of performers who earned their livelihood through performance. For that, they were dependent on the village folk, farmers, and landlords. The landlords were seen as sponsors, patrons, and mentors, because they could organize performance on a village scale. This is a hierarchical relationship, and the performers were placed near bottom of the social scale. Educated, modern and urban scholars have christened such performers ‘folk performers’. However, they remained largely out of the purview of modern patrons and audiences until the second half of the twentieth century, when changes in the pattern of rural social structure influenced the lives of these performers in ways that have yet to be documented. At the time when modern scholars and institutions started characterizing these performers as folk performers, popular cinema became all-pervasive. While there is no causal connection between social change, scholarship, and mass entertainment provided by cinema, yet they are contemporaneous and influence each other.

In independent, postcolonial India of the 1960s, community life as well as the performance of Muslim Jogis had to contend with new challenges. Although located in the specific context of postcolonial India, these processes can be seen in other societies as well, particularly in postcolonial societies where independence from colonial rule was followed by the creation of a civil society and where performance traditions belonged to pre-colonial social structures that had been damaged, destroyed, erased and re-evaluated in colonial times. These postcolonial societies had to contend with tradition, and critique of tradition, to be able to evolve into independent nations. For example, the critique of the caste system in India led to the formulation of a constitution that negated the caste system as a defining element of social structures. Folk performers and their patrons related to each other within the caste system; its negation opened up new possibilities, but also took away its former security. This complex process can be illustrated by the history of a family of Muslim Jogis, told here in the form of a parable.

Jogi Zahoor Khan had bhapang in his blood. He played it even when he was sent to school. He went to school, but did not go very far in his studies. As a young man, he started to play his bhapang and sell cigarettes and bidis outside the cinema hall of his small town to supplement the meagre and dwindling income he received from traditional performance in the village. Hindi cinema, on the other hand, was drawing huge crowds, and any business outside the cinema hall would thrive. One day a film premiered there and the film crew came all the way from Bombay. Outside the cinema hall they heard the bhapang of Jogi Zahoor Khan and saw this cigarette seller playing a musical instrument. The music caught their attention and they asked the performer to come along with them to the tinsel town of the film industry—Bombay, now Mumbai. And off he went, on a course that would break all hitherto existing boundaries of fame.9

No matter how far the fame of a folk performer spreads, it still remains local, while fame earned through the film industry knows no boundaries. No wonder, then, that the hit songs in which Jogi Zahoor Khan’s bhapang was heard across the nation also came back to his village. Until now, people of his generation and those younger than him remember the elation they felt as he reached unprecedented heights. This elation had a logical extension—the realization of the possibility that their art could find new vistas.

What was happening in Zahoor’s life was more than his personal success: two historical periods, two technologies and two art forms had collided with each other. Zahoor standing outside a cinema hall and playing the bhapang is an image that may show his powerlessness and cinema’s power, but that is only the view on the surface. Zahoor and his art were actually exceeding the limitations of tradition, and the events that followed demonstrate the implications of this exit for the orature of the Jogis.

Popular cinema had used his musical instrument and his ability as a player, but not the songs and stories that the bhapang accompanied. The musical instrument was disconnected from the stories and the songs, and from the community of brothers and cousins who narrated or sang them. The oral epic was left behind in the village, too. It is as if the modern disjunction between tradition and the self was executed through the life of Zahoor Khan. The text did not travel to the film industry, not because there was no place for it there, but because that place was occupied by the classical version of the epic. The twists and turns in Zahoor’s life are moments in India’s cultural history that otherwise remain invisible to the naked eye.

Around the same time, a few years later, an urban, educated folklore enthusiast emerged as a new local patron for folk performers in Rajasthan, Komal Kothari. Along with his friend and writer Vijaydan Detha, Kothari founded Rupayan Sansthan in Borunda village to document Rajasthani folklore.10 Zahoor Khan and his growing son, Umer Farukh, were some of the folk performers he patronized. On the one hand, then, the performers were experiencing a disjunction from tradition. On the other hand, almost simultaneously a folklorist came and evaluated the wholesomeness of the tradition and wanted to present it to the world as ‘traditional folklore’. As if acknowledging the irony, young Umer sang a song in a private gathering at Kothari’s house about the influence of fashion on young Jogis and their desire to abandon their traditional profession and become urbane and educated.11

Despite the opportunities in the film industry, or the possibility of becoming a symbol of traditional culture through identification by a folklorist, the disjunction between the community and individual, between patrons and performers, between texts and sounds, and between music and musical instrument could not be contained. This was not intended: the disjunction had been caused by a combination of circumstance and chance within the larger frame of history. The performance at Kothari’s home shows the transformation that was taking place within the community wherein youngsters were, in any case, feeling attracted to other, more urban lifestyles and professions.

The song that Zahoor’s young son Umer Farukh was singing about ‘fashion’ in society was his own composition. The song itself is a record of social change, including the change in the self-perception of Jogis—that Jogis youngsters want to become ‘gentlemen’ and not performers. Indeed, awareness about school was spreading, and education was seen as a way to move out of caste-based professions and raise one’s social and economic status. Umer himself was going to school. His father and uncles were mainly performers of the epic and songs, and he was exposed to them too, but he was also realizing the need to create texts that would work with wider audiences. Living between two worlds, Umer graduated from college and joined a clerical position (naukri) in the government. But he left his naukri soon to continue his life as a performer. Like his father, Umer also started playing on public radio, where there was a policy decision to create space for folk music. In this he was exemplary, as many of his community were lured by the promise of a small but stable income, certainly more than that which came from performance.

Another new phenomenon emerged for Umer’s generation: around the 1970s, the world of festivals—national festivals, folk festivals, regional arts and crafts festivals, etc.—started. These were new venues for performance, drawing new kinds of audience. In these new venues, a fissure between text and performance inevitably developed, for the text was limited by language while the performance and music were not. As a result, the performance of the text remained more important in the local and traditional venues, but in new venues the universal language of the performer’s style and music became the centre of attention.

New venues demanded ‘traditional yet modern’ performances, for which Umer Farukh had the talent. He combined the old with his own new creations: he knew the epic, the songs, but could also create new songs, fusing them with the contemporary discourse of a democratic society.12 He was a success, perhaps bigger than his father as he was not dependent on another industry. Festivals became more international, and Umer, his uncles and cousins started roaming the world. He remained active in this circuit and carved out a small-town life for his family. His son Yusuf went to school, and after completion was trained in computers and wanted to change his profession, while also documenting his granduncles on a video camera that my film maker husband presented to him. Destiny had other plans, and Umer Farukh suddenly passed away in 2017 during a performance.

This brought his son Yusuf back to performance, as a stable income was already carved out by his father and he was familiar with all the circuits of this profession. For the last three years or so, Yusuf has taken on the role of his father as the lead singer of the group made up of his uncles and grand uncles. He not only looks increasingly like his father and sings his compositions, but also uses all the stage tricks, jokes, and commentaries that his father used. Decades of stage performance and the experiences of two generations before him have certainly increased the group’s self-awareness as performers and as members of civil society. Yusuf’s original additions are two: his engagement with the technology of his time—the new media—and establishing newer forms of community building. He is very active on Facebook, where he not only posts pictures of his every performance and of every newspaper article mentioning him, but also keeps in touch with each and every ‘patron’ that has appreciated his father, for example the officials of the public and private cultural institutions that have ever supported them, or people like Sudheer and me who became friends while researching the Jogis.

Yusuf’s performances now include members of other performing communities. This cutting across community lines is a new phenomenon that has emerged, once again, due to several factors. On the one hand, performers do not really have large communities any more as most of the community members have moved on to other professions, and quite often the performers function as several families combined. On the other hand, festivals often create spaces that never existed in reality, bringing performers of different genres on the same stage in one evening. Urban audiences also expect ‘variety’ in cultural events. In the process, the performers have realized that they can themselves create new styles by coming together, and gain more traction and bargaining power with the sponsors as a result. One may either lament such changes as the loss of wholesome tradition, or one may come to the realization that folk performers have always responded creatively to the challenges of their times, because their art form is also the source of their livelihood. The coming together of performers of different communities also breaks down barriers of caste, religion, and gender, and as such is certainly a feature of civil society.

In orature of this kind, learning is mimetic, and it is over time that a performer makes his individual mark. Yusuf’s grandfather made a mark by rising up to the occasion that sheer chance presented him with. His father made his mark by his ability to perform in traditional as well as non-traditional circuits of national and international festivals, which required more than just artistic ability: it required developing successful public relations among the educated, governmental, and international sponsors for which the tradition had not exactly prepared him. Yusuf is presently functioning within the networks established by his father, but will have to establish an independent relationship with the times in which he is living.

Dastan and Dastangoi: A Revival

The second orature that I want to discuss is called dastangoi, literally ‘storytelling’. Rooted in various traditions of narrating stories in Iran and connected with forms of storytelling in Afghanistan, dastangoi is an Indian tradition of narrating stories that emerged in Mughal India and found its expression in the Persian-Urdu-Hindi languages. It is essentially a multi-lingual tradition whose exact contours are determined by the geographical location and defined by its style. Dastangoi flourished in both the courts and the streets of Mughal India.13 A single individual, sometimes accompanied by one more, would narrate stories to small groups of listeners. They might also do so by invitation for a family. Both men and women have been known as narrators or dastango (dāstān-go), as they are called. We need only think of Sheherazade of the Arabian Nights, who is also a storyteller.

Unique to this style of storytelling is that the human voice is the only medium of communication. The dastango was not accompanied by any musical instrument. As a result, it is the play of language and modulation of voice that communicated the stories. And what did the dastangos narrate? They depended on repertoires of Persian origin, most famously the Dāstān-e Amīr Ḥamzah, which is a quasi-epic containing hundreds of stories revolving around Amir Hamza, believed to have been the uncle of the Prophet Muhammad. This style of stories is rooted in oral traditions of wondrous tales akin to the style of the Arabian Nights, with fantastic stories full of marvel, partly history, partly imagination. Several dastan texts became available in print in the nineteenth century, like the monumental, multi-volume Dāstān-e Amīr Ḥamzah (1881–1906) published by the famous Naval Kishore of Lucknow. The vibrant tradition of dastangoi, however, came to an end in the early twentieth century, and after 1928 no one is known to have participated in the tradition.14

After a complete break of many decades, the late-twentieth-century Indian scholar Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, inspired by the work of his American colleague Frances Pritchett, started researching the Urdu Dastan-e Amir Hamza and the tradition of dastangoi. His work inspired his nephew Mahmood Farooqui to think further. Mahmud Farooqui is a postcolonial Indian with school- and university-level qualifications, and in the 1990s he was pursuing higher studies in history at Oxford and Cambridge. As he himself told me, his knowledge of the Urdu language was minimal at that time. He had had some interest in theatre, but not at a professional level. Yet, inspired by the stories about the storytelling tradition of dastangoi, back in India he decided to experiment with it. Frances Pritchett had scanned the available sources and written in some detail about the dastangoi tradition in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries.15 The practice was liveliest in four cities: Delhi, Lucknow, Akbarabad (Agra), and Rampur. Each city claimed to have a unique style, but Lucknow’s was perhaps the most vibrant. Yet, the available details related to a dastango are those of Mir Baqir Ali of Delhi. Born in 1850, he lived until 1928 and is the last known dastango. Dastangos were famous for narrating one story over days, weeks, or even years. At Mir Baqir Ali’s house, people gathered every Saturday evening, and the narration went on until late in the night. Pritchett summarises from the available accounts that:

a few basic devices of oral dastan recitation can be pieced together: mimicry and gestures, to imitate each dastan character; insertion of verses into the narrative; recitation of catalogues, to enumerate and evoke all items of a certain class as exhaustively as possible; maximum prolongation of the dastan as an ideal goal. Moreover, the association of dastan-narration with opium is mentioned in so many contemporary accounts that it should not be overlooked. If both dastan-go and audience were slightly under the influence of opium, they might well enjoy the long catalogues and other stylized descriptive devices, which slowed down the narrative so that it could expand into the realms of personal fantasy.16

This gives us a glimpse of the art of dastangoi, but the information is at best ‘fragmentary’.

Pritchett then felt that ‘dastan-narration as an oral art is essentially beyond our reach. We are several generations removed from the last expert practitioner, and the secrets of his art died with him. No folklorist ever made a transcript—much less, of course, a tape recording—of an oral dastan performance’.17 In the late twentieth century, one was dependent on fragments of information about the art of dastangos and on the published repertoire of dastangoi tradition. Still, Mahmood decided to give it a go, and in 2005 he began to narrate dastans. Before that, however, several decisions had to be made.

The study of this process is a study of what it means to revive a tradition. Mahmood could not have revived the intimate, small group setting of the dastangoi tradition. Therefore, he could not have revived the place of the narrator sitting at the same level among the listeners, nor can today’s sessions last interminably. With his interest in theatre, he immediately imagined it as a stage performance. What he took from the dastangoi tradition were the costume of the narrator, the text, and the human voice as the only medium of communication. He started narrating selections from the Amir Hamza repertoire as dastangos used to do.

Right from the beginning it worked with the audience as authentic dastangoi—people were willing to listen to a story being told by a person sitting on stage and believe that they were experiencing the historical form of dastangoi. There was perhaps some cultural memory that helped the performer and the audience in subconscious ways. Media reports were favourable enough, and Mahmood could continue his experiment. He started realizing that while the form of storytelling is attractive to contemporary audiences, traditional texts have their limitations: they cannot be appreciated by everyone because of their linguistic style and because of the content of their stories, which sometimes clashes with contemporary sensibilities. So, he decided to compose his own stories, and thus emerged stories located in the Indian context: stories about the partition of India, about Buddha, about characters from the epic Mahabharata. Then came stories from international literature, like Alice in Wonderland or The Little Prince. More people joined him and the style started evolving. Then a woman called Poonam Girdhani, also a trained theatre actor, approached him and said ‘will this remain just a male tradition?’. Mahmood included her in the group, and today she is another senior member. In fact, today there are even younger women in the group.

Easy as it sounds, many complexities are involved in this revival: of language, religion, region and politics. Traversing them requires considerable engineering. I have watched Mahmood Farooqui’s narration of the story of Karna from the Hindu epic Mahabharat.18 Karna, the illegitimate son of the heroes’ mother Kunti, was wronged by the laws of Hindu society right from his birth. He was abandoned by his mother; he was born upper caste but grew up in a lower caste family; he disguised himself as a Brahmin because he wanted to learn archery from the master who only taught Brahmin caste boys and was discovered and cursed; finally, a very generous and righteous Karna joined the villains. Mahmood Farooqui narrates the travails of this character from the perspective of a secular and post-modern artist. He is certainly not limited within the bounds of traditional dastangoi. Stylistically, Mahmood takes from other narrative traditions rooted in styles practiced by Hindu narrators, and he mixes languages; Sanskrit, Hindi and Urdu. At times, he begins his performance by saluting the Hindu and the Muslim divinities. In a way, this is not a completely unknown style, since all classical musicians, including Muslim musicians and singers, start their performance by praying to Hindu gods and goddesses. What we see in Mahmood Farooqui’s performance is a continuity of cultural nuances, but also a postcolonial form of dastangoi infused by ideas of Indo-Islamic syncretic traditions and post-independence constitutional secular discourse.

Tradition, Orature and World Literature

This brief description of two traditional oratures and their contemporary existence allows us to reflect upon three categories and their relationship to each other: tradition, orature and world literature. The two performative traditions were originally the product of the contact between Persian-Islamic and Indian-Hindu traditions of texts and performance. The Muslim Jogis of Rajasthan are located along the route through which the Sultans, Sufis, and traders brought Islam to India. They and their traditional patrons—the farmers and landlords—converted to Islam over the past millennium but continued to hold on to the stories of their Hindu epics, gods and goddesses. Although it has not been ascertained by any research, it is well worth asking the question whether Jogis were already professional narrators who earned their living by telling stories of the epics and of God Shiva, and conversion just made them Muslim Jogis. While they are practicing Muslims, other Jogis in the same region are Hindu, and each has its own specific, generally religious, repertoire. Their professional and religious identities could peacefully co-exist until the end of the twentieth century, but became problematic with the rise of religious fundamentalisms as both Hindus and Muslims started objecting to this happy combination. Their performative tradition continues, but the need to reinvent is also acute. While the musical instrument, music, and style of performance communicate with contemporary audiences, the audiences are not educated in the textual tradition. Performance venues have also changed in spite of themselves. These venues have emerged in the context of international discourses on heritage and its preservation by governmental and non-governmental organisations, both nationally and internationally. In the case of dastangoi, a conscious revival effort has been made. Here too, it was more feasible to revive the performance style than the traditional texts, and the textual repertoire had to be reinvented.

The geographies of performance have changed for both oratures, as their current venues of performance are not traditional—totally non-traditional in the case of dastangoi, and increasingly non-traditional in the case of the Muslim Jogis. Despite the differences in the context and identity of their performers, the two oratures are clearly proceeding on two tracks that share many similarities in the abstract.

These two ethnographies allow us to theorize about the form and content of oratures. The forms and contents of oratures may travel long distances, that is, they may have come from places far away from where they are found by the researcher. They may not even have any existence in the so-called place of origin. Their full growth may have been achieved in an unprecedented form in the place where we find them. For example, dastangoi must be seen as an Indian orature, although its texts may be rooted in a foreign landscape. On the other hand, the historical context of people may change and yet their orature may remain connected to a pre-existing tradition, as in the case of the Jogis. The relationship of form and content may change further in connection with historical time, as reflected in the contemporary forms of the two oratures discussed in this chapter. Processes of entextualization and recontextualization are visible throughout. Based on these two examples, one can say that the form and content of oratures are independent of each other. Content, meaning the texts, stories, language, and reception, is rooted in socio-historical context. Form, meaning the style of performance, music, and costume, is timeless and can take on new content. When the form takes on new content, as when dastangos start performing The Little Prince or Alice in Wonderland or when the Jogis start singing new compositions, the orature gains a new child that is genetically connected to its older self but has a life of its own. In both the oratures discussed above, the performers feel the need to change the content of their oratures or to create new texts for the form in which they are trained as part of a tradition, or for the traditional form which they choose to adopt and adapt after a historical break in the tradition. At the core of the oratures and their performance is communication between performers, performance texts, audience, and context.

The relationship between tradition, orature and world literature is reflected in the two performative traditions discussed in this chapter. Although they have different trajectories of existence, yet there are many processes that are comparable. In their traditional forms, they were performing texts that were international in their spread. The Adventures of Amir Hamza performed by the dastangos was a story known across Asia, particularly West and South Asia, and it was also translated in several European languages.19 The epic composed by a Muslim poet for the Jogis in the sixteenth century was a retelling of the epic Mahabharat, also well-known across South, South-east and West Asia, and also translated into many European languages and acclaimed as a classic of world literature. Since these texts were essentially orally transmitted, they crossed several geographic, linguistic, religious, and cultural boundaries over a long time. In their travels they influenced several communities and cultures, and they themselves been influenced and reshaped by the communities and cultures with which they came into contact. They have existed as written and as oral texts; they have been read and they have been performed. Before the differentiation between folklore and literature was articulated in the early nineteenth century and then carried over to other continents in the context of colonialism, these oratures held a place similar to literature in their cultural contexts. The modern differentiation came about mainly based on the medium of communication—oral versus written. This differentiation was not even valid in several cultural contexts. For example, in India, classical arts and learning were also transmitted largely orally, although written and authored texts existed and were written and read. It is well-known that, in the colonial contexts, prioritising writing as symbolic of cultural superiority was advantageous to the colonizers as the colonized countries of Africa, Asia, Latin America, Australia, and Canada were predominantly oral cultures.20 By implication, written literature became superior to oratures, and the latter could be kept out from world literature. By further implication, the list of world literature texts will be dominated by European literature. Postcolonial theory would see this as continuance of colonial paradigms, or what Walter D. Mignolo terms ‘coloniality’.21 It compels us to challenge this division between folklore and literature.

Orality as the medium of communication and the absence of an identifiable individual author are not weaknesses of oratures; they are their strengths that give them the dynamic energy to adapt to changing times, to metamorphose, and to experience revival after long historical breaks. The important thing is whether oratures are in circulation, whether they are still valuable, and whether, if no longer in circulation, they have historical value. The oratures behind these performative traditions continue to circulate across the world in many different forms and at many different levels, and each new technology, be it print or cinema or new media, attracts performers who are drawn to present these oratures according to its aesthetic capabilities.

To sum up, the relationship between tradition, orature and world literature is a dynamic one, as opposed to the common perception of it as static. This relationship keeps changing with reference to local and global history. It demands the expansion of the definition of world literature, from being a canon of unchanging written texts to include creative oral texts that have taken from and given to world cultures. A changed definition and the inclusion of oratures in world literature would also help in the preservation, revival, evaluation and dissemination of long-standing oratures, of which the versified oral epic Pandun ke Kade and the many dastans are examples.

Bibliography

Baumann, Richard, ‘Performance’ in A Companion to Folklore, ed. by Regina F. Bendix and Galit Hasan-Rokem (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, 2012), pp. 94–118.

Bharucha, Rustom, Rajasthan: An Oral History. Conversations with Komal Kothari (New Delhi: Penguin India, 2003).

‘Bhapang Jugalbandi, Strange and Amazing Musical Instrument by Umer Farooq’ (2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U9FywkzWERQ

Briggs, Charles and Sadhana Naithani, ‘The Coloniality of Folkloristics: Towards a Multi-Genealogical Practice of Folkloristics’, Studies in History, 28.2 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1177/025764301348

Dāstān-e Amīr Hāmzah (Lucknow: Naval Kishor Press, 1881–1906).

Dastangoi, ‘Dastan-e-Karn az Mahabharat’, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8S-puxBzIGA

‘De Data Ke Naam Tujhko Allah Rakhe’, Ankhen (dir. Ramanand Sagar), music by Ravi, lyrics by Sahir Ludhianvi (1968), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b9m-TMNbRCs

Geertz, Clifford, ‘Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight’ in The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973), pp. 412–453.

Gulati, G. D., Mewat: Folklore, Memory, History (Delhi: Dev Publishers and Distributors, 2013).

Gupta, Sudheer, Three Generations of Jogi Umer Farukh, film, 54 minutes (New Delhi: Public Sector Broadcasting Trust and Doordarshan, 2010), https://cultureunplugged.com/storyteller/Sudheer_Gupta

Kumar, Mukesh, ‘”The Saints Belong to Everyone”: Liminality, Belief and Practices in Rural North India’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Technology Sidney, 2019), http://hdl.handle.net/10453/134150

Mehta, Varun, Dastangoi, RSTV Documentary (2014), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_GFsOa2a3Q4

Mignolo, Walter D., Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges and Border Thinking (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).

Nair, Malini, ‘The secret ingredient to Bollywood’s funny songs was a unique drum played by a distinctive man’, Scroll.in, 30 August 2023, https://scroll.in/magazine/1045905/what-made-bollywood-songs-funny-a-unique-drum-played-by-a-distinctive-man

Naithani, Sadhana, The Story-Time of the British Empire: Colonial and Postcolonial Folkloristics (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010).

Pritchett, Frances W., The Romance Tradition in Urdu: Adventures from the Dāstān of Amīr Hamzah (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991). For an augmented translation, see: http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00litlinks/hamzah/index.html

Sila-Khan, Dominique, Crossing the Threshold: Understanding Religious Identities in South Asia (London: IB Tauris, 2004).

TedX Shekhavati Omer Mewati, Saving Rajathan’s Legacy, 6 April 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4ObtOH_wPRs

1 Sudheer Gupta, Three Generations of Jogi Umer Farukh, film, 54 minutes (New Delhi: Public Sector Broadcasting Trust and Doordarshan, 2010); the links for this and other documentary films and video recordings are given in the Bibliography.

2 TedX Shekhavati Omer Mewati, Saving Rajathan’s Legacy, April 6, 2011; ‘Bhapang Jugalbandi, Strange and Amazing Musical Instrument by Umer Farooq’ (2015), YouTube.

3 I recommend the 2014 RSTV Documentary Dastangoi by Varun Mehta.

4 Quoted in Sadhana Naithani, The Story-Time of the British Empire: Colonial and Postcolonial Folkloristics (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2010), p. 39.

5 Richard Bauman, ‘Performance’ in A Companion to Folklore, ed. by Regina F. Bendix and Galit Hasan-Rokem (Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, 2012), pp. 94–118 (p. 95).

6 For the point about ‘natural performers’, see Bauman, ibid.; for ‘deep play’, see Clifford Geertz, ‘Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight’, The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973), pp. 412–453.

7 See G. D. Gulati, Mewat: Folklore, Memory, History, Delhi (Dev Publishers and Distributors, 2013).

8 See Dominique Sila-Khan, Crossing the Threshold: Understanding Religious Identities in South Asia (London: IB Tauris, 2004); and Mukesh Kumar, ‘”The Saints Belong to Everyone”: Liminality, Belief and Practices in Rural North India’ (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Technology Sidney, 2019).

9 See Malini Nair, ‘The secret ingredient to Bollywood’s funny songs was a unique drum played by a distinctive man’, Scroll.in, 30 August 2023; the bhapang can be heard in the song ‘De Data Ke Naam Tujhko Allah Rakhe’, Ankhen (dir. Ramanand Sagar), music by Ravi, lyrics by Sahir Ludhianvi (1968).

10 For a profile of Komal Kothari and his work, see Rustom Bharucha, Rajasthan: An Oral History. Conversations with Komal Kothari (New Delhi: Penguin India, 2003).

11 See Gupta, Three Generations, 00:40–01:40.

12 See the song Umer Farookh and his bhapang group perform for a festival in Gupta, Three Generations, 03:00 onwards, where Umer also explains about being a Muslim Jogi and his relationship with the bhapang, and mentions the film song ‘Data de’ for which his father had played.

13 See Frances W. Pritchett, The Romance Tradition in Urdu: Adventures from the Dāstān of Amīr Hamzah (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991) and website.

14 See ibid.

15 Ibid., p. 3.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 For a brief extract, see Dastangoi, ‘Dastan-e-Karn az Mahabharat’.

19 See Pritchett, The Adventures.

20 See Naithani, The Story-Time; Briggs and Naithani, ‘The Coloniality of Folkloristics’.

21 Walter D. Mignolo, Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges and Border Thinking (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000).