6. Multimodal Cognitive Anchoring in Antisemitic Memes

©2024 Marcus Scheiber, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0406.06

The ongoing mediatisation and digitalisation of our lives has also resulted in an increasing dissemination of antisemitic concepts. Antisemitic evaluations that have existed for centuries are finding their way into online debates in new semiotic patterns and in innovative communication formats. Memes are one kind of these new communication formats, which prototypically have a text-image structure and can be utilised to realise antisemitic concepts that are anchored in cultural memory. This chapter explores the production and reception processes of these anchored concepts in antisemitic memes by showing the patterns of cognitive processing that allow the integration of verbal and pictorial sign potentials within the meme format via the processes of blending.

1. Introduction

While digital forms of communication, such as the social media or internet fora, offer unlimited possibilities for the distribution of opinions, it is becoming apparent that they can also be used as a breeding ground for antisemitic ideas. Although antisemitic memes do not account for a considerable proportion of popular memes, they can nevertheless be identified in numbers that are sufficiently large to make them relevant with regard to the dissemination of antisemitism. A meme―a popular format of internet content which prototypically combines text and image, usually in a humorous way―has the potential to carry ideas concisely, contributing to their spread and normalisation.

From the point of view of semiotics, an individual meme is configured by the assembly of a format from semiotic resources, which are realised as a functionally organised composition of the participatory sign acts (that is, elements that communicate meaning). This is due to the mutual integration of the pictorial and verbal acts that structure and give rise to the conceptual representation of an antisemitic meme (Scheiber 2019: 150).

Since the interpretation of antisemitic memes is restricted to the conventionalised communicative patterns, these memes can be regarded as sedimentation of discursive practices. The generation of their meaning takes place as a process of cognitive configuration of discursive knowledge, that is, and it is subject to these conventional patterns as well as to the antisemitic projections anchored within society. In such a way, the contextual reference framework evokes a functional matrix. This matrix not only productively restricts the communicative and interactive realisation possibilities (of the semiotic surface) but also receptively limits the cognitive-semantic conceptual possibilities of an antisemitic meme. Within this chapter, these production and reception processes are analysed with the help of blending theory (Fauconnier and Turner 2002) to show the patterns of cognitive anchoring activated by multimodal antisemitic communication processes online.

2. Data

The following discussion of memes and their analysis are based on a corpus that was compiled with the help of the imageboards―databases of online images―“Know Your Meme”, “Quickmeme” and “9Gag” throughout June 2023. Search queries for the terms “antisemitism”, “Jews”, and “Israel” returned structurally corresponding but thematically different memes from these three imageboards. Selections from this corpus serve as comparative examples to illustrate the respective patterns of the analysed memes.

3. Antisemitic stereotypes

Since the reception process of an antisemitic meme relies on web users’ knowledge as well as their communicative expectations related to antisemitic ideas, it is important to explain the antisemitic conceptual structure that the individual memes utilise. Antisemitic beliefs are socially distributed mental constructs that stem from social practice, are based on shared stereotypes and are anchored within a cultural memory. Both antisemitic and non-antisemitic stereotypes can be described as mental representations that are stored in long-term memory and ascribe characteristic features to a specific group. Stereotypes prove to be simplifying, generalising and reductionist schemata that help their users cognitively by making the world both more experienceable and understandable (Quasthoff 1973).

At the same time, stereotypes can also serve as a basis for antisemitism when they conceptualise Jews as alien entities who, by their very nature, represent the absolute evil in the world. This is because antisemitism is not based on a flesh-and-blood hatred of Jews but on a systematic projection or mental representation of Jews that has no real-world counterpart. The stereotype is the product of collective schematic attributions; that is, all perceptions and aspects of knowledge―even those that run counter to an antisemitic interpretation―are selected and structured in such a way that they fit into a closed antisemitic conception of the world. This legitimises or constitutes an outlook in which the individual concepts give rise to a relational conceptual structure of Jewish people. Often, the conceptual structure holds Jews responsible for all crises in the world and believes that they profit from them; it allows many to believe that Jews developed both capitalism and communism and that they instrumentalise antisemitism or are themselves responsible for it (Salzborn 2011). The irrational selectivity of antisemitic interpretations overrides reason as well as logic; it is based on a simple dichotomy of good and evil, within which Jews are conceptualised as the root cause of evil (Schwarz-Friesel and Reinharz 2017, Bolton 2024). Memes reinforce the antisemite’s view of a world that excludes Jews or is seemingly threatened by Jews. Accordingly, analysis of the antisemitic stereotypes found in memes reveals a cognitive narrative about a hostile enemy and an implicit call to fight against it.

4. Patterns of memes

Memes present themselves as a communicative consequence of the diverse semiotic and medial possibilities offered by the technically as well as socio-culturally determined affordances of digital communication. Since the latter enables collaborative practices for participation, memes are realised as formats that function as communicative templates for social interaction. They can be described as patterns of multimodal sign acts that are characterised by

- collective semiosis (meaning is constituted via multiple sign users);

- re-semiotisations (transposing meaning from one context to another) (Iedema 2003: 41);

- a functional matrix of production conditions and reception possibilities;

- a family resemblance of the individual members; and

- discourse-semantic network structures (Scheiber, Troschke and Krasni forthcoming).

Based on this list of semiotic properties, (discourse-)semantic conditions and pragmatic usage, the prototypical manifestation of a meme is as a text-image structure.1 Not every text-image structure within digital communication, however, has the status of a meme: the texts and images in each artefact must follow a recognisable pattern yet exhibit a high degree of variation, and the number of disseminations of individual artefacts must exceed a certain ‘tipping point’ in order that web users perceive a trend (Breitenbach 2015: 36). Thus, memes emerge via collective-semiosis processes; they are collaborative constructions of meaning that come about through the participation of various users who generate a recurring (multimodal) pattern from a singular artefact via its re-semiotisations (reproduction, imitation and variation) (Klug 2023: 206).

On one hand, memes are simple. The mutual integration of the sign modalities involved goes hand in hand with a reduction of information complexity, that is, the process relies on structural and content-related simplicity (Breitenbach 2015: 37). On the other hand, memes are sophisticated insofar as the integration of verbal and pictorial sign modalities generates an emergent meaning. In order for the intended significance to be derived despite these semiotic challenges, memes make use of interpretation patterns for the reception process on the semiotic surface. These have both a regulatory effect with regard to pragmatic (cognitive) usability and a selective effect with regard to the use of semiotic resources for the respective arrangements: memes establish common spheres of cultural knowledge, so that they can be decoded by web users who are familiar with the communication format (Breitenbach 2015: 45).2 In other words, the production of a meme is structured by a functional matrix that provides a framework for the semantic organisation as well as the pragmatic usability of the text-image structures, but the cognitive processing of this matrix or framework also limits the meme. For, both the production and the reception of a meme are dependent on web users’ knowledge of the world but also of the relations to other text-image structures of the same pattern. Hence, the constitution of meaning in a meme takes place through the family resemblance of the individual artefacts to each other. Consider the following examples:

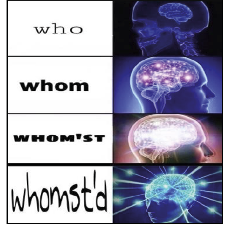

Figure 6.1: One example of the “Galaxie Brain” meme, Know Your Meme, reproduced under fair dealing, https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1217719-whomst.

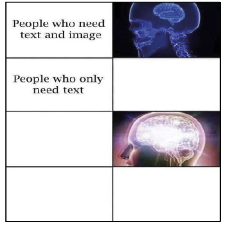

Figure 6.2: A second example of the “Galaxie Brain” meme, Know Your Meme, reproduced under fair dealing, https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/1755097-galaxy-brain

The vertical arrangement of the pictorial and verbal elements in both Figure 6.1 and Figure 6.2 encourages a consecutive interpretation of the contents, which themselves depict an experiential intensification. This intensification is realised in the correlation of the (fictitious) syntactic expansion of the verbal expression “who” with the pictorial representations of increasingly illuminated brains. Figure 6.2 evokes this interpretation through corresponding (visual) ellipses. The linking patterns used between the verbal and pictorial sign acts in Figure 6.2 refer to the knowledge and communicative expectations of a web user with regards to the prototypical realisation possibilities of the meme in Figure 6.1. Accordingly, Figure 6.2 can also be interpreted as an intensification of Figure 6.1, although verbal and pictorial ellipses have been introduced. This example demonstrates that recurring composition or linking patterns both force and limit specific semiotic practices as well as communicative structures within memes.

The realisation of a meme is to be understood as an expression of discursive practices insofar as the compositional organisation of the semiotic elements in a text-image structure provide information about the discursive practice in which they occur: “At all points, design realizes and projects social organisation and is affected by social and technological change” (Kress 2010: 139). The placement of the individual sign modalities actualises communicative structures, constitutes social relations through composition patterns and realises communicative functionalities by means of the connection or separation of communicative elements (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006: 177). As web users employ a wide variety of memes to convey the most diverse contents, memes present themselves as a discursive practice of knowledge generation:

First, memes may best be understood as pieces of cultural information that pass along from person to person, but gradually scale into a shared social phenomenon. Although they spread on a micro basis, their impact is on the macro level: memes shape the mindsets, forms of behaviour, and actions of social groups (Shifman 2014: 18).

Each meme can be characterised as the sedimentation of a discursive production process, which at the moment of its execution uses discursively conventionalised templates to satisfy the communicative needs of digital communication (Beißwenger 2007: 202). Hence, the constitution of meaning takes place as a process of double emergence: on the one hand, the text-image structure must be decoded as such and, on the other hand, the resulting patterns of interpretation must be placed in relation to the framework structure of the communication format. The individual meme is actualised as a punctual event, which―as a text-image structure with a communicative function―carries meaning in itself, but it also reveals a discourse-semantic network structure in the process of reception or identification as a communication format. The condition of its constitution is therefore based on the relation of a meme to other memes of the same pattern.3

5. From conceptual metaphors to blending

According to conceptual metaphor theory, metaphorical mappings can be defined at the physical level as neural networks that link sensorimotor information to more abstract concepts (Tendahl 2015: 28). A useful way to think about this is that “[m]etaphors provide sets of mappings between a more concrete or physical source domain and a more abstract target domain. For example, since we all feel hot as a result of physical exertion or excitement, metaphors that are rooted in the concept of Intensity is heat seem entirely natural to us” (El Rafaie 2015: 14).4

Therefore, an entity―however abstract―is made cognitively available through conceptual metaphors by relating it to a sensory realm of experience. In this way, metaphors serve as elementary structures of order by means of simplification. The anchoring of abstract conceptual domains in experience enables a cognitive orientation in the world because the metaphorical concepts are able to partially structure an experience in terms of another experience (Rolf 2005: 235).

Within such an understanding, the semiotic formations of these structures function merely as a reflex of the underlying conceptual representation (Stöckl 2004: 202). However, since sign resources are to be understood not only as a medium for conveying reality but also as a means of constituting it, cognitive structures cannot be granted primacy over their semiotic manifestations (Spitzmüller and Warnke 2011: 46). Sensory impressions do not present themselves in consciousness as they are but as they appear conditionally; that is, they are shaped by the fact that referential access to them can only take place via actualised sign resources in their communicative contexts of use. However, since every sign belongs to a cognitive category as a sign of a certain type, these sensory impressions are categorically grasped in the act of their referential access. These categories of conceptualization, in turn, determine which aspects of an entity one is interested in and which not, so that conceptual structures and their semiotic manifestations are mutually dependent (Köller 2004: 330): cognitive structures are materialised by means of various sign resources and, at the same time, semiotic units model cognitive structures. An absolute epistemological claim of metaphorical mapping must therefore be contradicted in favour of an epistemic relation between abstract cognitive operations and semiotic acts corresponding to these operations, so as not to fall prey to logical cognitivism.

Blending theory arises because of this criticism, since it is mindful of the fact that metaphorical mapping is always bound to the prototypically expected contextualisation and reveals itself as a reciprocal process. Blending theory takes the form of a network model that replaces the two-domain model of conceptual metaphor theory with a fourfold concept consisting of two inputs: one, a generic space that controls relations and units common to the inputs as a kind of template, and two, the result of this process―the blend (Schröder 2012: 83). “In blending, structure from two input mental spaces is projected to a new space, the blend. Generic spaces and blended spaces are related: blends contain generic structure captured in the generic space but also contain more specific structure, and they contain structure that is impossible for the inputs” (Fauconnier and Turner 2002: 47).

Hence, the process of blending takes place through the partial projection of certain elements in the blend that are assigned to the input spaces based on cultural knowledge or frames. Within the blend, these elements are integrated into each other, and the structure that emerges cannot be found in the individual input spaces but exclusively as the result of the blend (Fauconnier and Turner 2002: 48).5 An example of a metaphorical utterance such as “The surgeon is a butcher” is illustrative. Conceptual metaphor theory is not able to explain the negative connotation carried by this metaphor because it cannot make its emergent structure comprehensible. The negative evaluation of a “surgeon” when likened to a “butcher” results, by means of a functional linkage of the two, from the discrepancy of their predications as emergence, not from the unidirectional transfer of certain qualities of the expression “butcher” to the expression “surgeon”. Consequently, the metaphor can only be experienced in the juxtaposition of the two professions against the background of a cultural knowledge frame. The contrast between them is realised by referring the blend back to the two input spaces and the generic space (Evans and Green 2006: 410). Accordingly, metaphorical structures must be understood as semiotically bound constructions that generate a specific extension of meaning of the sign modalities used in the overall communicative process. They generate a horizon of meaning situationally, not simply a selective projection of a specific conceptual excerpt.

6. Utilising antisemitic memes for blending

“If text and images were more or less the same, then combining them also would not lead to anything substantially new. […] If text and images were completely different, totally incommensurate, then combining them would not produce anything sensible either” (Bateman 2014: 7). The negation of these two extreme positions, that is, the fact that a combination of verbal and pictorial signs exists, legitimates the analysis of memes by means of the blending theory. For, multimodal units―which include antisemitic memes―by their very nature consist of a cognitive integration in terms of the blending of different sign modalities. In “The surgeon is a butcher”, for example, the concepts to be integrated from Input Space I (“surgeon”) and Input Space II (“butcher”) are both of a single sign modality (verbal text). However, in an antisemitic meme, different sign modalities are used and must be integrated into one another. The difference between the sign systems now has a functional effect on the transfer process. An image cannot transfer the same values as the verbal text and vice versa, because both have prototypically different functions: while images visualise or intensify the content of the message, verbal signs can express illocutions and realise negations (Meier 2014: 125). Without a divergence in the prototypical predication structure of the two sign modalities in their cognitive anchoring, their combination could not take place.

At the same time, the relation between the relevant properties of the elements involved in the blending process are not inherent but originate in experience-based knowledge. This knowledge is drawn from a certain perspective of reality, and the blending is, therefore, subject to a context-bound expectability (Skirl 2008: 25). The reason for this is that the conceptualisation of a semiotic unit is realised via situational, textual and epistemic contexts and is subject to knowledge that has been negotiated in a social practice and that has emerged in a domain-specific manner (Wrede 2013: 183). Hence, the sign acts used in an antisemitic meme do not themselves determine the property dimensions that are correlated in the blend. They are, rather, based on knowledge of the conventionalised meanings of those concrete sign acts against the background of their contextual use (Bateman 2014: 176). In other words, the selected property dimensions in the process of blending are not only registered but, above all, interpreted against the background of existing knowledge and modified with regard to current communicative needs as well as antisemitic projections.

Certain aspects or property dimensions of a concrete (multimodal) communicative element are projected onto another element because these have prototypically communicative relevance in the given context. Their selection is not a determined or mechanical process that takes place continuously in the same way that the sign resources are correlated with each other in a relational structure. Rather, the process is a highly dynamic and flexible one: two people can receptively decode different meanings from one and the same multimodal unit due to their different experiences and knowledge (Evans and Green 2006: 409). This observation is especially relevant when considering antisemitic memes, since these usually contain components that a web user is not able to understand without contextual knowledge of the world. Analysis of antisemitic memes regarded as metaphorical structures, therefore, is an analysis of semiotically bound knowledge representation on a cognitive level in which the semiotic structures are an expression of the cognitive-processing mechanisms and these mechanisms are based on culturally anchored antisemitic projections.

7. Analysis: cognitive anchoring of antisemitic memes

Based on the previous explanations, the following list of questions forms the focus of the analysis to outline the production conditions and reception processes of antisemitic memes:

- Which textual elements and visual figures are used to convey which information?

- How does the web user navigate cognitively in the text and image space of the meme’s communication format?

- What knowledge does the user need to have to understand the semiotic arrangement with respect to the antisemitic interpretation?

- How is the blend created?

- Which aspects of meaning are (selectively) projected or integrated into each other?

- What emergent antisemitic meaning results from this?

Consider the following examples:

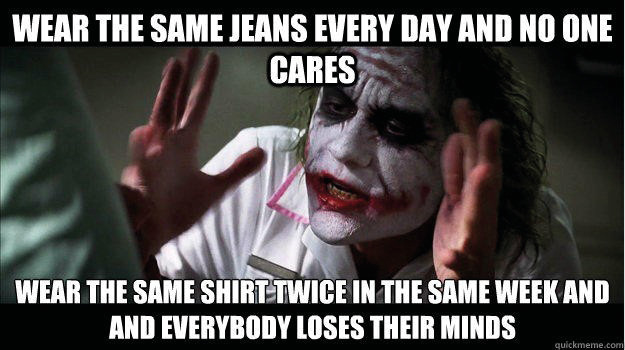

Figure 6.3: One example of the “Everyone loses their minds over clothes” meme, Know Your Meme, https://knowyourmeme.com/photos/544777-everyone-loses-their-minds

Figure 6.4: An antisemitic example of the “Everyone loses their minds over Russia” meme, Quick Meme, http://www.quickmeme.com/p/3vtyqp

The microstructure of the antisemitic meme in Figure 6.4 already places demands of the most complex kind on the users. They must first identify the semiotic components of the text-image structure before they can integrate these and decode the emergent antisemitic meaning.

The realization users reach via the process of object recognition is that the memes in Figures 6.3 and 6.4 are constituted of several sign acts. This corresponds to their expectations regarding the communication format and the way it makes recourse to existing knowledge about the prototypical realisation possibilities of the same: memes are prototypically multimodal. In the selective sensory reception of information, focus is given first to the individual pictorial signs because these claim a higher relevance in the cognitive processing of a text-image relationship; only in a second step does the user turn to the verbal sign acts (Geise and Müller 2015: 97).6 Yet, the verbal parts of the memes above generate a frame, within which their contents are arranged in a communicative logic of action and a linear-time axis, that is, they are localised in a situational reality. Accordingly, assumptions regarding material and other qualitative properties, such as the spatial-temporal location of the respective reference objects, must be already established so that it is possible to conceptualise them.7 The semiotic formations in question must necessarily exist as perceptible entities and in a way that allows predications to be attributed or denied to them on a representative level.

Figures 6.3 and 6.4 use the same pictorial elements. These intensify the messages displayed in the textual elements by emphasising the difference between them via conventionally established visual patterns. The open mouth as well as the forward posture of the person depicted signal danger and aggression. In this way, the pictorial elements express a lack of understanding that is to be interpreted as a reaction to the verbal elements: the (seemingly) identical course of action of the Israeli expansionist policy is given a different representation than the Russian one, although both of them deserve the same evaluation. While Israel’s actions do not cause a disturbance (“Israel occupies Palestine for 47 years and no one bats an eye”), the Russian actions cause an outrage (“Russia does it for a week and everybody loses their minds”, Figure 6.4). The fact that the two states and their respective military actions are placed in relation to each other at all, or that this relation is not questioned, presupposes the possibility of comparability; this is a fundamental element of the antisemitic construction of meaning within the meme. “Russia does it for a week” refers to Russia’s violation of international law by deliberately and unjustifiably attacked a sovereign state, while the duration “47 years” is a reference to the Six-Day War and Israel’s territorial gains afterwards―knowledge that users must possess and must have implicitly activated in order to decode the meaning of the meme: although they are legally, historically and morally different circumstances, Russia’s actions in violation of international law are equated with Israel’s historical developments. The meme thus activates and articulates a reductionist scheme or antisemitic concept within which only negative characteristics are attributed to Israel. It does so by both equating Israel’s history with Russia’s (morally objectionable) actions and by distortedly simplifying these historical circumstances to 47 years of occupation.

The meme’s antisemitic meaning is realized, therefore, through the expressed indignation of the (supposed) contradiction that Israel is assessed differently to Russia despite its actions being just as reprehensible. If the person depicted is now recognised as the figure of the Joker, the pictorial part of the meme allows this contradiction to be directly experienced in its disproportionality and, consequently, amplifies the antisemitic meaning.8 This figure, profiled as an antitype, has the property of expressing (seemingly) uncomfortable truths in the form of a contradiction. By drawing attention to such contradictions, the Joker―in the ironic doubling of the function of a ‘joker’ and, in the referenced film scene, the only one who can proclaim the truth because he does not have to fear any negative consequences―legitimises the comparison and makes it a fact: the antisemitic meaning of the meme constitutes a negative conceptual structure of Israel.

Figure 6.4 also realises the multi-phrase compound “and no one bats an eye / and everyone loses their minds”, which is a necessary condition for the meme: every text-image structure that uses precisely this image must include this text for the meme to be recognised and interpreted as such, with its specific meaning potential and affordances. Web users who are familiar with the communication format base their interpretation on the expectation that these multi-phrase compounds will be present as soon as the image of the Joker is used.9 The semantic restrictions of the communication format thus give rise to a patterned communicative structure that must correspond to user expectations if the intended (antisemitic) reception is to be guaranteed. The structure provides a framework that forces a certain reading of the meme in that the semantic relations of the verbal elements generate a global scope on the text-image structure. The consequence of such semantics determined by the structure is formulated as a lack of alternatives in the concrete meme, and the creative and cognitive limitations associated with it. Reception of the internal communicative organisation of the meme takes place when the pictorial signs are used to fill the gaps opened by the verbal sign acts. This takes the form of an antonymic juxtaposition that, then, is also manifested in the spatial arrangement of the verbal elements. The arrangement can be characterised as prototypical for the meme of this class and reveals a further semantic dimension: the spatial arrangement of verbal and pictorial signs follows the interpretative pattern in which elements positioned at the top are interpreted as positive (ideal) and units positioned at the bottom as negative (real) (Kress and van Leeuwen 2006: 186), and it correlates with the verbally executed contradiction. Placement of the statement “Russia does it for a week and everybody loses their minds” in the lower part of the meme portrays the Russian actions negatively and prompts criticism or questioning of Israeli actions. Indeed, the meme’s ironically constructed and contradictory nature suggests that Israel’s action is even worse than Russia’s, thereby contributing to its antisemitic meaning.

This top-bottom reading of ideal and real categories should not be applied to all text-image structures, since, on the one hand, such a dichotomy is empirically untenable and, on the other, what assigns a corresponding value to the contribution element is not spatial organisation but the user (Bucher 2011: 133). Although this criticism is justified in principle, Kress and van Leeuwen’s dichotomy is valid with regard to this meme. In its prototypical manifestation, the meme exhibits precisely those semiotic restrictions of placement and an accompanyingly limited framework of processing. Hence, the respective zones do not actually have any meaning per se, but users ascribe certain functions to them in a pattern-like manner due to their knowledge of the supra-individual interpretation patterns or the cognitive-realisation possibilities of the respective memes.

Even though the selection and structural composition of the sign resources used in this meme are limited, the conceptual representation of this text-image structure is an extremely complex process since the verbal parts of it already represent an independent blend.10 Two blends are constructed via the necessary phrases “and no one bats an eye” and “and everyone loses their minds”. In the cognitive processing of this meme, a correlation is then established between the blends and the metaphorical utterances, insofar as both the verbal utterances positioned above and those mounted below reveal themselves as single-scope networks.11

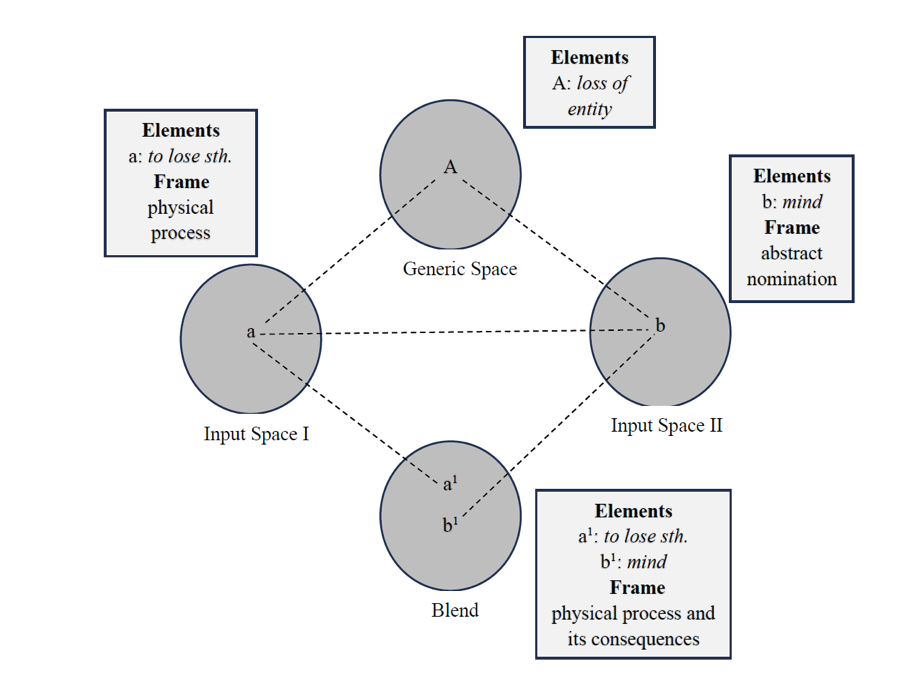

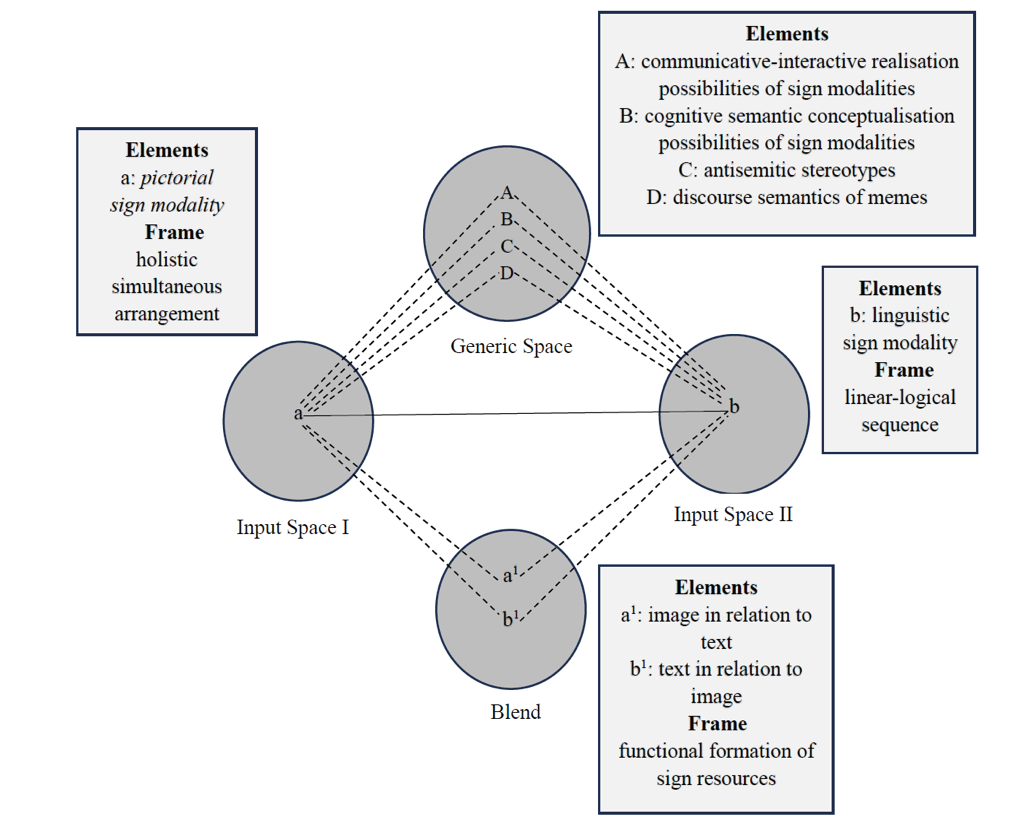

However, conceptualisation of the metaphorical utterances “no one bats an eye” and “everyone loses their minds” is determined in each case with the help of a different semantic dimension. While “everyone loses their minds” represents a relational link between a physical experience and an abstract entity, the conceptual projection in the utterance “no one bats an eye” only takes place within the conceptualisation of a physical process (Input Space I) against the background of the cultural interpretive framework (Generic Space) around the concept “eye” (Input Space II). The phrase “to bat” is, first, to be understood as a physical process within which the physical entity eye correlates with the function of making emotions visible or which has the function of generating emotional affects―be it through open or closed eyes or in the form of another bodily expressive movement. Consequently, the emergent structure of the phrase “no one bats an eye” results from the linking of its physical dimension of meaning, realised in the phrase “no one bats”, and the conceptual frame around the expression “eye”. Taken together, these structure the blend. Since Israel’s actions do not evoke any physical reaction, the metaphorical statement “Israel occupies Palestine for 47 years and no one bats an eye” by itself, likewise, does not produce a strong emotional reaction. In contrast, the statement “everybody loses their minds” partially projects the physical experience of losing something onto the abstract entity “mind”. See, in Figure 6.5, that Input Space I contains the structures around the syntagma “losing something” (a), while Input Space II has the abstract nomination “mind” (b). The Generic Space then provides the conceptual framework for the functional integration of these two concepts. For, this is realised, on the one hand, by the knowledge that people can lose objects and that, furthermore, the loss of an object makes it impossible to carry out activities for which that object is intended (A). On the other hand, it contains the knowledge that the expression “mind” has a physical component (B), insofar as the mind is mostly located in the brain. Hence, the blend results from the functional linkage of the abstract nomination “mind” (b), which is identified as a physical entity (b1), with the physical process of loss (a1). By this mechanism, the absence of mind is interpreted as a dysfunction of mind. The blend is structured by the concept of loss, in that the construction uses the knowledge of the users to correlate the concepts involved in an integral conceptual structure:

Figure 6.5: Conceptual Blend “Everyone loses their minds” 12

At the same time, the loss of mind appears as an extreme reaction to Russia’s actions in Ukraine insofar as the identical actions of Israel occupying Palestine do not evoke any emotional affects (which it should if they are equated―at least this is the antisemitic claim of the meme). The meme’s pictorial part can amplify this contradiction by materialising the disproportion that arises in the antonymic juxtaposition of the verbal utterances. Therefore, the functional complementarity of pictorial and verbal sign modalities gives rise to a cognitive-semantic interplay, by means of which the meme is always conceptualised in this way at a semiotic level and functions as a communicative template to carry the antisemitic meaning. In the two-dimensional compositionality of the meme, the temporal-sequential arrangement of verbal sign modalities in each exemplar of the same pattern is modified in favour of a spatial-visual organisation; however, the antisemitic meaning is evoked dynamically and discourse-sensitively insofar as the most diverse antisemitic concepts can be utilised for the same meme within the framework of its cognitive-semantic and discursive-medial realisation possibilities. Figure 6.6 illustrates this template character, which applies to all antisemitic memes:

Figure 6.6: General Conceptual Blend of antisemitic memes

The fact that the antisemitic conceptual structure in memes is metaphorically structured or can be grasped with the blending theory is also evident in the next example. The meme in Figure 6.7 comprises a semiotically complex arrangement of four different memes and, in this way, further demonstrates what discursive knowledge is needed to decode and process antisemitic memes.

Figure 6.7: An antisemitic meme “Always has been Jews”, 9 Gag, https://comment-cdn.9gag.com/image?ref=9gag.com#https://img-comment-fun.9cache.com/media/aerRRp/adRKBKAE_700w_0.jpg

As we have seen in previous examples, the pictorial patterns here are highly conventionalised. The semiotic restrictions of the format give rise to a communicative structure that corresponds to web users’ expectations and ensures the intended antisemitic reception of the meme. For, recognition of the pictorial components is sufficient to activate the prototypical mental representation of the meme in memory, that is, the visual organisation refers to already-existing and familiar structures of the same pattern and is then contextualised by the verbal component.

In the upper part of Figure 6.7, the pictorial sign actions of the illustrated figures, which refer to the “Boys vs. Girls” meme, are accompanied by text that expresses agreement within the in-group comprised of the person of colour and the white person. In the lower part of the meme, this agreement is amplified in the visual form of an arm-wrestle handshake, generating an intrapictorial coherence. The relationship between the pictures functions as a pars pro toto for overcoming racism in that the handshake both refers to the “Epic Handshake” meme and activates the socially traditional interpretation of this gesture as a realisation of approval.

The person of colour and the white person are in agreement about their evaluation of a figure who is shown in the lower part of the meme behind the handshake. This is the Happy Merchant, from the eponymous meme, that relies on antisemitically charged conceptual elements. The figure’s appearance―including curved nose, bulging lips, and crooked posture recalls physical attributes associated with Jews in antisemitic readings. Likewise, his identification as a “merchant” aligns with the antisemitic stereotype that Jews enjoy harming non-Jewish people through financial and other activities (Scheiber, Troschke and Krasni forthcoming). In bringing together these pictorial sign actions and activating this knowledge, the meme calls upon the blend available in an antisemitic reality: in the face of the Jewish threat―personified in the Happy Merchant―white people and people of colour overcome their differences to oppose this threat. This agreement worries the Happy Merchant to the extent that beads of sweat run down his face. These are not part of the prototypical portrayal of the meme-figure, and their addition here implies a demand for action from the user. The suggestion is that cooperation between a white person and a person of colour produces a negative effect on the Happy Merchant and, as their stereotypical representative, all Jews.

On the verbal level, the meme realises the pair sequence of a question “So, it was the Jews?” followed by an answer “Always has been”. This refers to another meme, the “Always has been” meme, but gives it a specific antisemitic dimension by generating a coherent interrelation between the individual pictorial and verbal components of the sequential text-image structure. The “Always has been” meme expresses a moment of realisation in which a controversial issue is recognised as an absolute truth. By recontextualising the verbal part of the “Always has been” meme (transposing its semantic structure to this context), the meme in Figure 6.7 essentialises Jews and identifies them as (despicable) Happy Merchants. This characterisation is presented as an absolute and inescapable truth, provided that the phrase is recognised as a meme in its own right.13

Each component within Figure 6.7 that is borrowed from another meme represents an input space that reveals itself as a separate blend, so that the cognitive processing of the meme can be described as a multiple blend (Evans and Green 2006: 431). The blend of meaning from the input spaces gives rise to a complex consecutive text-image structure, and realisation of the pair sequence does not take place exclusively through the verbal sign actions but is also expressed in the relationship of the individual pictorial sign actions to each other against the background of an antisemitic contextualisation. At the same time, it should be emphasized, once again, that what is interacting is not the semiotic elements of the antisemitic meme but, rather, the users who read these elements with a particular knowledge of the world and who have certain media competencies in relation to the communication format of the meme. Which antisemitic concept is attributed to a meme depends on the normativity of discursive practices. Hence, once a blend and its cognitive mechanisms have been activated, the users perform semantic construction work in the course of meaning constitution by independently filling the antisemitic conceptual structure with textual, world or situational knowledge within an antisemitic belief system and decoding the antisemitic meaning in this way.

8. Conclusion

Memes have become part of our everyday communication. This chapter explored the patterns of cognitive anchoring in antisemitic memes to find out how memes are utilised on a cognitive level to disseminate antisemitic content. It became apparent that the cognitive anchoring of antisemitic concepts in memes can be described through multistage processes of blending. The understanding of an antisemitic meme takes place through several interlocking operations. On one hand, web users recognise and categorise the participating sign actions and their prototypical functions; on the other, their focus oscillates back and forth between the different sign actions, since it is only in their interdependent interaction that the meaning is constituted. Furthermore, users qualify this interaction with regard to the (discourse-)semantic properties of the prototypical reference pattern of the meme. Finally, they contextualise the meme within an antisemitic belief system. A multimodal understanding of an antisemitic meme results, therefore, from the recognition of the functional linking patterns and their respective communicative implications, which generate synergetic action between the prototypical modalities and an antisemitic conceptual structure.

References

Bateman, John A., 2014. Text and Image. A critical introduction to the visual/verbal divide. Abingdon: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2016.1260358

Beißwenger, Michael, 2007. Sprachhandlungskoordination in der Chat-Kommunikation. Berlin: De Gruyter, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110953121

Bolton, Matthew, 2024. “Evil/The Devil”. In: Matthias J., Becker, Hagen, Troschke, Matthew, Bolton and Alexis, Chapelan (eds). A Guide to Identifying Antisemitism Online. London: Palgrave Macmillan

Breitenbach, Patrick, 2015. “Memes. Das Web als kultureller Nährboden”. In: Patrick, Breitenbach, Christian, Stiegler and Thomas, Zorbach (eds). New Media Culture. Mediale Phänomene der Netzkultur. Bielefeld: transcript, 29–49, https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839429075-002

Bucher, Hans-Jürgen, 2011. “Multimodales Verstehen oder Rezeption als Interaktion. Theoretische und empirische Grundlagen einer systematischen Analyse der Multimodalität”. In: Hajo, Diekmannshenke, Michael, Klemm and Hartmut, Stöckl (eds). Bildlinguistik. Theorien. Methoden. Fallbeispiele. Berlin: Erich Schmidt, 123–156, https://doi.org/10.37307/b.978-3-503-12264-6

Drewer, Petra, 2003. Die kognitive Metapher als Werkzeug des Denkens. Zur Rolle der Analogie bei der Gewinnung und Vermittlung wissenschaftlicher Erkenntnisse. Tübingen: Narr, https://doi.org/10.1515/zrs.2009.037

El Refaie, Elisabeth, 2015. “Cross-modal resonances in creative multimodal metaphors. Breaking out of conceptual prisons”. In: María Jesús Pinar, Sanz (ed). Multimodality and Cognitive Linguistics. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 13–26, https://doi.org/10.1075/rcl.11.2.02elr

Evans, Vyvyan and Melanie, Green, 2006. Cognitive Linguistics. An Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

Fauconnier, Giles and Mark, Turner, 2002. The Way We Think. Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities. New York: Basic Books, https://doi.org/10.1086/378014

Geise, Stephanie and Marion G., Müller, 2015. Grundlagen der visuellen Kommunikation. UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, https://doi.org/10.36198/9783838524146

Iedema, Rick, 2003. “Multimodality, resemiotization: extending the analysis of discourse as multi-semiotic practice”. Visual Communication 2 (1), 29–57, https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357203002001751

Jäkel, Olaf, 2003. Wie Metaphern Wissen schaffen. Die kognitive Metapherntheorie und ihre Anwendung in Modell-Analysen der Diskursbereiche Geistestätigkeit, Wirtschaft. Wissenschaft und Religion. Hamburg: Dr. Kovač

Klug, Nina-Maria, 2023. “Verstehen auf den ersten Blick – oder doch nicht? Zur (vermeintlichen) Einfachheit kleiner Texte am Beispiel von Internet-Memes”. In: Angela, Schrott, Johanna, Wolf, Christine, Pflüger (eds). Textkomplexität und Textverstehen. Berlin: De Gruyter, 195–230, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111041551-008

Köller, Wilhelm, 2004. Perspektivität und Sprache. Zur Struktur von Objektivierungsformen in Bildern, im Denken und in der Sprache. Berlin: De Gruyter, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110919547

Kress, Gunther and Theo, van Leeuwen, 2006. Reading Images. The Grammar of Visual Design. Abingdon: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.1075/fol.3.2.15vel

Kress, Gunther, 2010. Multimodality. A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Abingdon: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2011.551502

Meier, Stefan, 2014. (Bild-) Diskurs im Netz. Konzept und Methode für eine semiotische Diskursanalyse im World Wide Web. Köln: Halem

Quasthoff, Uta M., 1973. Soziales Vorurteil und Kommunikation. eine sprachwissenschaftliche Analyse des Stereotyps. Ein interdisziplinärer Versuch im Bereich von Linguistik, Sozialwissenschaft und Psychologie. Athenäum

Rolf, Eckard, 2005. Metapherntheorien. Typologie. Darstellung. Bibliographie. Berlin: De Gruyter, https://doi.org/10.1515/arb-2013-0086

Sachs-Hombach, Klaus, 2003. Das Bild als kommunikatives Medium. Elemente einer allgemeinen Bildwissenschaft. Köln: Herbert von Halem

Salzborn, Samuel, 2011. “Antisemitismus”. In: Europäische Geschichte Online (EGO), http://www.ieg-ego.eu/salzborns-2011-de

Scheiber, Marcus, 2019. “Perspektivistische Setzungen von Wirklichkeit vermittels Memes. Strategien der Verwendung von Bild-Sprache-Gefügen in der politischen Kommunikation”. In: Lars, Bülow and Michael, Johann (eds). Politische Internet-Memes – Theoretische Herausforderungen und empirische Befunde. Berlin: Frank & Timme, 145–168

Scheiber, Marcus, Hagen, Troschke and Jan, Krasni, forthcoming. “Vom kommunikativen Phänomen zum gesellschaftlichen Problem: Wie Antisemitismus durch Memes viral wird”. In: Susanne, Kabatnik, Lars, Bülow, Marie-Luis, Merten and Robert, Mroczynski (eds). Pragmatik multimodal. Tübingen: Narr

Schröder, Ulrike, 2012. Kommunikationstheoretische Fragestellungen in der kognitiven Metaphernforschung. Eine Betrachtung von ihren Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. Tübingen: Narr

Schwarz-Friesel, Monika and Jehuda, Reinharz, 2017. Inside the antisemitic mind. The language of Jew-Hatred in contemporary Germany. Waltham, MA: Brandeis University Press, https://doi.org/10.26530/oapen_625675

Shifman, Limor, 2013. Memes in Digital Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2016.1130504

Skirl, Helge, 2008. “Zur Schnittstelle von Semantik und Pragmatik. Innovative Metaphern als Fallbeispiel”. In: Inge, Pohl (ed). Semantik und Pragmatik – Schnittstellen. Berlin: Lang, 17–40

Spitzmüller, Jürgen and Ingo, Warnke, 2011. Diskurslinguistik. Eine Einführung in Theorien und Methoden der transtextuellen Sprachanalyse. Berlin: De Gruyter

Tendahl, Markus, 2015. “Relevanztheorie und kognitive Linguistik vereint in einer hybriden Metapherntheorie”. In: Klaus-Michael, Köpcke and Constanze, Spieß (eds). Metonymie und Metapher – Theoretische, methodische und empirische Zugänge. Berlin: De Gruyter, 25–50, https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110369120.25

Wrede, Julia, 2013. Bedingungen, Prozesse und Effekte der Bedeutungskonstruktion. Der sprachliche Ausdruck in der Kotextualisierung. Rhein-Ruhr Press

1 “Prototypicality”, in this article, refers to the prototype theory developed in the cognitive sciences that negates entities’ categorical boundaries in favour of a family resemblance. The prototypicality of the property dimensions results from the combination of frequency and distinctiveness of these in relation to other exemplars (Sachs-Hombach 2003: 296).

2 Every form of communication, including memes, requires the mastery of certain cultural practices (reading, writing, speaking) that productively as well as receptively define a framework for the use of the respective communicative form.

3 There are possibilities for variation, individualisation and hybridisation of individual memes in relation to the basic pattern, since reproduction of an artefact without variation of the same does not necessarily establish meme character: patterns in relation to memes must be determined in the sense of family resemblance.

4 Conceptual metaphors comprise a systematic connection between two conceptual domains, one of which functions as the target domain and the other as the source domain of metaphorical mapping (Jäkel 2003: 23). The metaphorical transfer from the source domain to the target domain takes place non-directionally, so that there is no conceptual loopback from the latter to the former (Drewer 2003: 6), https://doi.org/10.1515/zrs.2009.037

5 From the perspective of blending theory, the source domain and the target domain do not differ: both are equally involved in the meaning making of a metaphorical utterance, since both provide structures to generate the blend.

6 This is also one of the reasons why memes are popular for propagating antisemitic beliefs, as memes are grasped both sensory and cognitively faster than purely verbal units, since they are based on a sensory immediacy (Geise/Müller 2015: 109), https://doi.org/10.36198/9783838524146

7 In the act of referentialisation, a spatial-temporal existence is presupposed, which then takes the form of an implicit predication in Generic Space.

8 The meme “Everyone loses their minds” originates from a scene in the 2008 superhero film The Dark Knight, which shows a villainous character called the Joker, the protagonist’s adversary. In the scene depicted, the Joker utters the following words: “If, tomorrow, I tell the press that, like, a gang banger will get shot, or a truckload of soldiers will be blown up, nobody panics, because it’s all part of the plan. But when I say that one little old mayor will die, well then everyone loses their minds”.

9 Nevertheless, familiarity with the Joker is not necessary to grasp the text-image structure at a basic level; the posture and facial expression of the person depicted already signal danger and aggression, characteristics that correlate with the assessment of reality with regard to an antisemitic perspective on Israeli actions.

10 Although the meme is understood even without knowledge of the person depicted, insofar as the gestures are interpreted as an expression of incomprehension within the framework of socially traditional patterns of interpretation, the pictorial part of this meme also already represents a blend. For within the text-image structure, it is not just any person who takes on the function of a nurse, but the figure of the Joker. The knowledge about the Joker provides input I and the knowledge about the activities of a nurse provides input II. In the context of the film The Dark Knight, from which the image originates, this character is now profiled as a person whose actions reveal themselves to be contrary to the expected activities of a nurse: Instead of helping or caring for other people, he harms them. The conceptual integration of these opposites results in the blend as the culmination of the contradictory nature of the Joker’s character, in that he portrays a nurse.

11 Since a detailed presentation of the various possibilities of cognitive configurations of integral network structures would go beyond the scope of this chapter and only individual types of these are relevant for the analysis, the explanations have to remain brief. For more discussion, see Evans and Green 2006, 400–440.

12 Mental spaces are represented as circles, their conceptualisations as rectangles and the individual elements as letters. The cross-mapping between the elements is visualised as a dashed line.

13 If the phrase is not recognised as a meme in its own right, then this layer of meaning is lost. However, the meme is still interpreted as antisemitic because the phrase implies a causal relationship between Jews and all imaginable (evil) actions.