1. Grotesque Vignettes and the “All Margin” Book

©2024 Evanghelia Stead, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0413.01

Barely twenty in late 1892, Aubrey Beardsley was hard at work on his first major assignment. He was to fully illustrate Thomas Malory’s medieval narrative Le Morte Darthur and his undertaking pivoted on the Pre-Raphaelite style he would master, transform, and transgress. However, the artist quickly found the task both arduous and tedious and, in order to cheer him up, his publisher, Joseph Malaby Dent, further commissioned him to decorate three tiny volumes of puns and witticisms: the debonair, often humorous, gibes known as bon mots since the seventeenth century. The set of sketches Beardsley produced for this commission might seem marginal, but in this chapter I show how they became a seminal graphic laboratory for the emerging artist. These little grotesques – a multifarious combination of figures with blended body parts, hybrid animals, mythical creatures, foetuses, peacock feathers, one-eyed spiders, and endless other curious amalgamations and disturbing juxtapositions – almost form an artwork in their own right. They were small and sat on the edge of insignificant jokes. Yet, the visual and graphic marginality of such a peripheral creation gave Beardsley the opportunity to use the vignettes as a kind of breeding tank for forms that would occasionally feed into his “great” works.

The vignettes point to a significant turn in his work and prove to be a genuine crucible of graphic impulse as different styles are tried out, parodied, and revamped. This chapter will explore how Beardsley morphed and repurposed motifs launched by his contemporaries, such as the Pre-Raphaelites, Odilon Redon, and James McNeill Whistler, granting them new life in grotesque form. He inaugurated his “entirely new method of drawing,” at times “founded on Japanese art but quite original in the main,” and at other times “fantastic impressions treated in the finest possible outline with patches of ‘black blot.’”1 The vignettes boldly engage in linear drawings enhanced by black-and-white contrasts. They play, alter, and convert. They are at once unnerving, erotic, and humorous. They prove to be that unique touchstone of “the smallest space and the fewest means” with which Beardsley achieved “the most.”2

Beardsley usurped the earlier grotesque tradition to transmute it into something that felt shockingly contemporary. He twisted calligraphy and creatively explored scrawls. He morphed natural motifs into artistic riddles. He treated bodies like books and ornamented them with grotesque vignettes. He invented an ironic and wry way of illustrating, connecting his vignettes to literal meanings, nonsensical jokes, and verbal twists, skilfully manipulating words and expressions. Expanding into new print territories, his vignettes spread in the illustrated press. He even created a book genre his publisher would further capitalise on, parallel to the bibelot booklets cherished at the time. Compared to the medieval and Renaissance grotesques, which famously were peripheral ornaments in the margins of devotional missals and breviaries, his Bon-Mots vignettes introduced a style of book that was all margin. This chapter will show how, in an aesthetic reversal of order and hierarchy, the margin came to be crucial, predominant, and fundamental.

Birth and Critical Background of an Unexplored Set

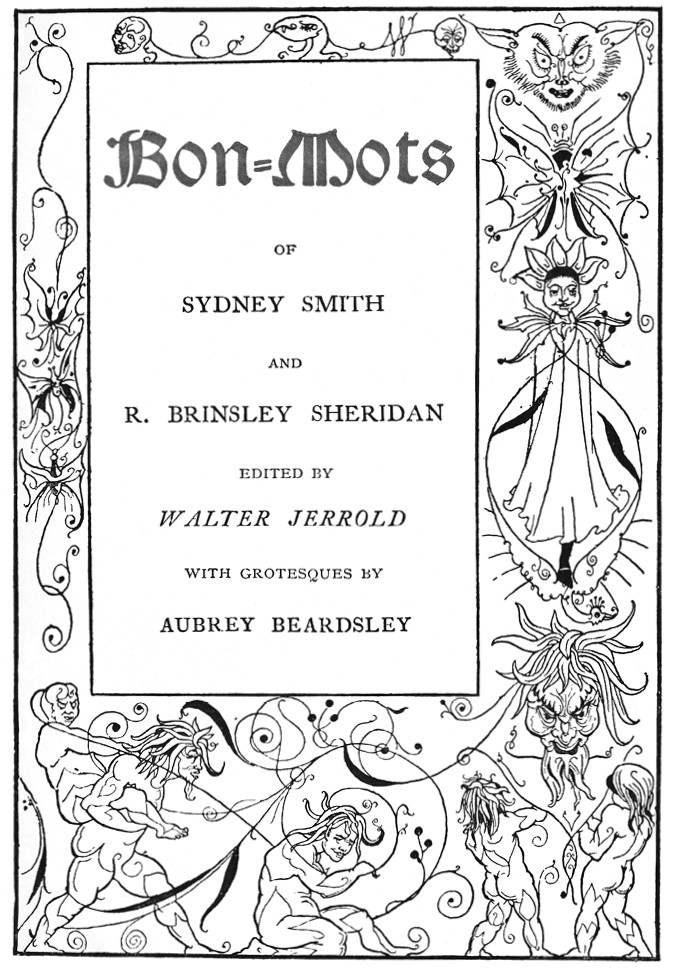

The volumes that Beardsley illustrated, entitled Bon-Mots, were edited by Walter Jerrold within a year in 1893–94. Each of them featured the work of two authors. In volume one, Sydney Smith (1771–1845), founding editor of the Edinburgh Review, Anglican clergyman and liberal reformer, successful London preacher and lecturer, and author of a rhyming recipe for salad dressing, joined Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751–1816), Irish satirist, politician, famed playwright, poet, profligate social climber, and womaniser. In volume two, Charles Lamb (1775–1834), the melancholic wit, essayist, and poet best known for his Essays of Elia, met with Douglas William Jerrold (1803–57), a master of epigram and retorts, professional journalist, Punch contributor, yet now forgotten dramatist. Samuel Foote (1720–77), comic playwright, actor, and theatre manager known as “the English Aristophanes,” who had turned even the loss of his leg into a source for comedy, opened volume three. He teamed up with Theodore Edward Hook (1788–1841), composer and man of letters, best known for the Berners Street hoax, which he recalled in detail in their joint booklet. All texts, often of just a few lines, belong by nature to the periphery of these authors’ works: they are spirited rejoinders from conversational sport or utterances of marksmanship that hit the bull’s eye. Their droll anecdotes and amusing chitchat belong to the outer rim of belles-lettres, offered in these volumes for easy consumption to be readily repeated ad nauseam.

In autumn 1892, Beardsley wrote to his former headmaster at Brighton Grammar School, Ebenezer J. Marshall, who had founded Past & Present, the first school magazine ever published in England. Marshall had supported young Beardsley’s artistic ambitions and published the artist’s earliest drawings in Past & Present (Zatlin 135–44). Beardsley was anxious to impress Marshall in his letter, boasting of his feats with publishers, newly secured independence from salaried work, and the praise he had recently earned in Paris. He described the vignettes in a few brisk words and characteristic hurried style:

Just now I am finishing a set of sixty grotesques for three volumes of Bon-Mots soon to appear. They are very tiny little things, some not more than an inch high, and the pen strokes to be counted on the fingers. I have been ten days over them, and have just got a cheque for £15 for my work – my first art earnings.3

The fledgling artist needed to take every opportunity to earn some money and build his reputation. He was proud to advertise his first profits, but stresses the triviality of these “very tiny little things.” These lines immediately follow a description of the sumptuous grandeur of Le Morte Darthur commission. The latter description, however, is longer only by three-and-a-half lines. Even though Beardsley regards his vignettes as throwaway sketches, tossed off in ten days for a paycheck, the distinction between important and unimportant remains precariously balanced. Could the pre-eminence of Le Morte Darthur be questioned by the grotesques – if so, how and why?

The Bon-Mots vignettes were indeed of Lilliputian size. The original drawings, some of which are minute (among the known originals, one of the smallest measures 3.8 x 5.4 cm and the largest 18.3 x 11.7 cm),4 were often greatly reduced to fit into earmarked nooks and crannies in the printed versions. Ordinary copies of the booklets did not exceed 13.5 x 8.13 cm, and the large-paper edition, limited to one hundred copies, measured 16.4 x 9.9 cm. Whether ordinary or deluxe, the pages themselves, a standard 192 per volume, display a uniform printed surface never exceeding 9.85 x 5.3 cm. Reproduction further harmed their many subtleties. When printed, the vignettes seldom took up an entire page. Diminutive details became hard to decipher. Beardsley’s work had greatly benefitted from line-block printing, i.e., reproduction of lines and dots against white background with no intermediate tones. The line-block process was cost-effective, fast and reliable in terms of printing text and image together, but had two shortcomings: it sometimes thickened fine lines and downgraded in places the compact blacks of Beardsley’s designs. Several of the Bon-Mots grotesques fell victim to such processes. Layouts were not part of the artist’s remit either. Although opinions vary,5 Beardsley probably never saw proofs, Jerrold having assumed the task of checking them himself.

Initially the grotesques went relatively unadvertised in the Bon-Mots. First editions touted the title Bon-Mots in gilt capitals on their cream covers followed by the paired authors’ names (Fig. 1.1a). The prominence and credit belonged to the text not the images. “Grotesques by Aubrey Beardsley” featured in small reddish type, next to a similarly coloured ornament of a fool with bauble and under a gilt peacock feather. Beardsley’s renown having further expanded posthumously, it was only in 1904 that reissued volumes gave the lead to the artist: “with Grotesques by Aubrey Beardsley” girdled a cherub with two lilies (Child Holding a Stalk of Lilies, Zatlin 749, see Fig. 1.15a–b). Centrally placed on the cover, it ousted the authors whose names now took refuge on the narrow spines (Fig. 1.1b). The grotesque graphic core had become the book’s most prominent feature.

|

|

Fig. 1.1 a–b Successive Bon-Mots covers. 1.1a Bon-Mots of Samuel Foote and Theodore Hook, original edition with gilt title, peacock feather and fool with bauble. Courtesy of MSL coll., Delaware; 1.1b Later edition of the same promoting “Grotesques by Aubrey Beardsley.” Author’s collection

The lack of recognition of the vignettes in Beardsley’s lifetime was partly a result of issues around the printing and reproduction of such small images, which hindered appreciation of their detailed features. In 1896, when Leonard Smithers considered including one in Fifty Drawings, Beardsley alerted him to the difficulty of reproducing its tenuous lines: “It will I am afraid make a very bad block as the line is so thin and broken.”6 Another note to Smithers further discouraged him from publishing the vignette: “As to the Bon-Mot, it is such a trifle.”7 In the end, the vignette (subject unknown) did not find its way into the volume.

Such remarks from Beardsley may well have taken a toll on these drawings’ legacy: these “trifles” have been largely overlooked in scholarship. Even today, Beardsley is known as the art editor of the Yellow Book and the Savoy, and as the illustrator of Le Morte Darthur, Salome, and The Rape of the Lock. The foundational spirit of his early grotesques has remained in the shadows of his work. Brian Reade was a first exception in his 1967 Beardsley, which included a striking selection of eighty-seven untitled grotesques in sizeable reproductions and arresting contrast on the stark white pages of his

catalogue.8 Twenty years later, Ian Fletcher would comment on a few of them, followed in 1995 by Chris Snodgrass who focussed attention on some of Beardsley’s recurring motifs: puppets, foetuses, Pierrot, Harlequin, and Clown, and grotesque dandies.9 My own work and 1993 full catalogue (published in 2002) have remained unknown to Anglophone specialists and French connoisseurs alike.10 The three volumes of Bon-Mots stayed “virtually undiscussed,” as Linda Gertner Zatlin has put it.11

From one publication to the next, the total number of the vignettes varied, as in the figures given by Aymer Vallance and Albert Eugene Gallatin. Vallance presented them as “208 grotesques and other ornaments in the three volumes,” totalling with the title page and cover decorations 211 designs.12 Gallatin’s catalogue, limited to a small global description, provided neither titles nor an account.13 It counted 127 originals and two unused extras.14 In turn, The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, although referring to Gallatin, reckoned there are 130 drawings, described as “mostly small grotesques and vignettes.”15 The year 1998 marked the centenary of Beardsley’s death, and the Victoria & Albert Museum celebrated it with an exhibition curated by Stephen Calloway, which toured in Japan. Princeton University Library commemorated the centenary more discreetly with its fine collection of Beardsleyana. At least thirteen publications were brought out, but several failed to offer new insights; this led Snodgrass to eagerly speculate if this was “Tethering or Untethering a Victorian Icon?”16 The grotesques were again outweighed by major drawings.

It wasn’t until Zatlin’s catalogue raisonné that we had a full reproduction of the grotesques, together with records, locations, measurements of the originals, uses, reuses, and commentary. Zatlin also provided names for each vignette, which I use in this book. Zatlin’s project was first announced in 1997, and finally published in 2016.17 This major accomplishment at last granted the grotesques the space and attention they deserved as individual creations. Using Zatlin as my base, this chapter offers a critical appraisal of these neglected drawings, exploring their significance in terms of the development of Beardsley’s style and their impact on the artistic zeitgeist. Although trivial and marginal, I argue that such a body of work offers a rich insight into the artist’s budding styles. They form a test bed for experimentations, freeing Beardsley from imposing motifs of the time, allowing him to modernise older grotesques, and representing new ideas on illustration, the use of the body in artworks, and the idea of the book itself.

Winning Freedom

Beardsley’s minutiae were conceived on the side-lines of the two books that would establish him as one of the most talented and daring artists of the moment: Malory’s Le Morte Darthur (1893–94), published by Dent; and the English translation of Oscar Wilde’s Salome (1894), published by Lane. Both these publishers placed restrictions on Beardsley’s creativity. Dent wanted Le Morte Darthur to rival Kelmscott Press’s popular medievalism. The book was meant to be an exercise in imitation, offering readers photomechanical reproductions instead of costly originals under a sumptuous cover. Beardsley had wanted to translate Salomé into English from Wilde’s original French that he had read and loved. His first plate on the play, published in The Studio, has a French quote from Wilde’s initial published script (Zatlin 265). Instead, Alfred Douglas was entrusted with the word translation, and, furthermore, Lane chose to censor Beardsley’s skilful yet shocking plates, which the artist intended as a daring visual translation.18 Such restrictions and rebukes, also noticeable in Lucian’s True History, issued by Lawrence and Bullen in 1894,19 quickly wearied Beardsley.

The Bon-Mots grotesques formed in counterpart an untethered space of artistic freedom. Sketched in quick strokes but requiring several working sessions in 1892 and 1893, they would open the door to artistic experimentation and fuel Beardsley’s graphic variety. The text featured in Bon-Mots lacked plot, discernible arrangement, introduction, or conclusion, and fostered the possibility for inventive and prospective design, amalgamation, and innovation. In this way, the vignettes were exonerated from the constraint of a text to respect, since the textual content was itself random, unhindered, and liberally delivered. They rarely related to the quips they peppered. Far from being literal illustrations, they were consonant reinterpretations of clever (or less clever) lines through visual means.

As little conundrums squared on tiny spaces, the Bon-Mots drawings engage interpretation and meaning as much as they short-circuit them and leave them suspended. As Fletcher suggests, they are apart from Beardsley’s more famous work because they are inexplicable: “many operate as emblems requiring and at the same time defying interpretation in a way found elsewhere in the work, but never perhaps at such an extreme and so consistently.”20 They unquestionably form the largest and most diverse set of fin-de-siècle vignettes, and authenticate key statements by the artist. The press had christened Beardsley “An Apostle of the Grotesque,”21 but he parodied the apostolic ideal. Instead of urging viewers to perfection, sanctity, spiritual energy, and a holy life, he took great pleasure in confusing them with provocative drawings and mischievous titles. As the enfant terrible of the British fin de siècle, he inverted Saint Paul’s proclamation “If I have the gift of prophecy and can fathom all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have a faith that can move mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing” (1 Cor. 13, 2). While Saint Paul was nothing without love, Beardsley claimed, “If I am not grotesque, I am nothing.”22

In this avowedly grotesque and early nucleus, free of textual imperatives, young Beardsley tested, formed, and enlarged a new artistic idiom, taking up a mock-apostolic mission. As I explore in the following section, he broke free from the Pre-Raphaelite influence, and toyed with Aesthetic symbols. He challenged their strongly artistic stasis. He borrowed from Japanese prints and appropriated doodles from past centuries. He adopted customary, misshapen forms (satyrs and aegipans), and implemented realistic drawings, quickly turning to his black-on-white compositions. His grotesque language bounced from fauns and imps to spidery fancies and arabesques to blur forms, combine, mix, and blend them: organs, genitals, breasts, ink stains, scrawls, bristles and hair, forked tongues, squiggly appendages, wings. The difficulty of giving his creations an accurate title is genuine, yet the renewal of grotesque certain: disturbingly physical, subversively erotic and ambiguous, they usher in fin-de-siècle symbols and manifestos such as the foetus vignettes analysed in Chapter 2. They form an altogether vital contribution to the renewal of the grotesque at the end of the nineteenth century, springing from the mobility and variety of patterns without head or tail.

Hijacked Innovation

Beardsley’s vignettes in the Bon-Mots have a distinctive, incisive, impertinent spirit that hijacks existing motifs through pastiche and parody. Beardsley was proud, for example, of the impact of Japanese art on his graphics. He had just shown specimens of his new drawings to Puvis de Chavannes, then President of the Salon des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and reported to Marshall that Puvis liked them. Past & Present, his former school’s magazine, had been prompt to broadcast Puvis’s remark: “A young British artist who does amazing work.”23 The comment referred to Beardsley’s spatial illusion, characteristic of Japanese artworks, and the spidery lines that gave his compositions new verve. Likewise Beardsley challenged the creations of his innovative contemporaries. He appropriated Pre-Raphaelite motifs, the work of Walter Crane and his illustrated books, Whistler’s hallmark butterfly (a symbol, seal and a signature all in one), typical images of the Aesthetic movement (the sunflower, the lily, the peacock feather), and even Redon’s lithographs, as the following examples show.

Beardsley ably moved from traditional mythical themes to medieval depictions, leitmotifs of the Aesthetic movement, and fin-de-siècle patterns, all of which he altered in his signature style. A synthetic view of satyrs (Fig. 1.2a–g) shows how he used mythological motifs close to nature. He had peppered Le Morte Darthur vignettes and its dropped initials with cavorting fauns, evil terminal gods and voluptuous she-fauns smiling ambiguously. In the first volume of Bon-Mots, fauns and satyrs reappear as an especially predictable motif. A pouting and frowning Pan, holding a syrinx in his hairy paw, leans against a tree in Pan Asleep, named after Frederick H. Evans (Fig. 1.2a, Zatlin 710). Another, seen from the rear, rests against a tree stump, again with panpipes, in Pan down by the River (Fig. 1.2b, Zatlin 715, indeed “a sentimentalised version of the satyr in Le Morte Darthur”).24 A herm figure grins at us with a small faun perched on his shoulder, his belly covered by flowing fleece in Terminal God Listening to a Satyr (Fig. 1.2c, Zatlin 719). An evidently female version leaps around raising a trumpet in Dancing Satyr, a title that leaves gender unspecified (Fig. 1.2d, Zatlin 735). Another – bald, weary, and club-footed – closes the enigmatic parade of a skeleton in fancy dress and a sick man in an armchair, all perched on a peacock’s feather in Two Grotesques Approaching a Man with Gout (Fig. 1.2e, Zatlin 736). An emaciated specimen, his pelvis covered in long hair, looks pensively at us atop a cliff in Aged Satyr Seated on a Cliff (Fig. 1.2f, Zatlin 757). And a stylish aegipan with a shepherd’s staff collects rain or spring water in a vessel in Faun with a Shepherd’s Crook and a Bowl (Fig. 1.2g, Zatlin 784).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1.2a–g Aubrey Beardsley, Bon-Mots grotesques based on satyrs. 1.2a Pan Asleep, BM-SS:51; 1.2b Pan down by the River, BM-SS:67, BM-LJ:141 (R<); 1.2c Terminal God Listening to a Satyr, BM-SS:79; 1.2d Dancing Satyr, BM-SS:117 (half-title vignette for “Sheridan”); 1.2e Two Grotesques Approaching a Man with Gout, BM-SS:119 (head vignette for “Bon-Mots of Sheridan”), BM-LJ:182 (head vignette); 1.2f Aged Satyr Seated on a Cliff, BM-SS:172, BM-LJ:99 (full page, R>); 1.2g Faun with a Shepherd’s Crook and a Bowl, BM-LJ:108, BM-FH:62. PE coll.

The grotesque substance of these inveterate hosts of pastures, woods, and grottoes is heightened by the artist’s graphic skills: abundant hair, wiry and flimsy lines, thin parallel or wavy strokes, dotted streaks, a towering unbalanced composition or the nascent stylisation of black shapes against white backgrounds offer different versions of a well-worn motif. Yet, although Beardsley varied and reworked the faun images in the Bon-Mots, he seems to have grown tired of them. Only three from volume one (Zatlin 715, 736, 757), all rather elaborate, are reused in volume two, yet only once, as if their grotesque essence and significance had already been exhausted. The very last, invented for volume two, is again reused only once in the third volume. Their limited usage suggests their restrained appeal on Beardsley’s imagination.

Beardsley gleaned more long-lasting material from the Middle Ages, so cherished by the Pre-Raphaelites. There are numerous recurring figures in the Bon-Mots wrapped in loose cloaks, with faces hidden beneath a hood or cowl of medieval inspiration, which share a close resemblance to Edward Burne-Jones’s androgynous pages or William Morris’s similarly mysterious figures (Fig. 1.3a–g). With flesh bursting their tight-fitting garments, Beardsley’s creations reveal strained joints and limbs terminating in thin, unpredictable arabesques. A typical example is One-armed Man with a Sword (Fig. 1.3a, Zatlin 693), which adorned the first volume’s half-title, perhaps a playful allusion to the contents’ slender or imaginary structure. Seated Figure Tending a Steaming Cauldron (Fig. 1.3b, Zatlin 754) may also be a wry comment on the volume’s contents. Others, like the skeletal hairy monkey following a veiled man in Grotesque Reaching for a Cloaked Figure (Fig. 1.3c, Zatlin 738), may carry an armful of flowers as in Pierrot Carrying Sunflowers (Fig. 1.3d, Zatlin 707), or hold at arm’s length a head dripping with blood as in Cloaked Man Holding a Bleeding Head (Fig. 1.3e, Zatlin 712). When they turn around, they disclose grimacing faces, covered in wrinkles. They combine with more modern figures, clowns and Pierrots, or become themselves jesters in small acts performed in silence, as in Two Figures Conversing (Zatlin 753) and Jester with a Head on a String and a Disembodied Hand Holding a Cupid (Fig. 1.3f, Zatlin 744), which have components in common.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1.3a–f Aubrey Beardsley, Medieval grotesques in the Bon-Mots. 1.3a One-armed Man with a Sword, BM-SS:1 (half-title vignette), BM-FH:38; 1.3b Seated Figure Tending a Steaming Cauldron, BM-SS:165, BM-FH:89 (full page, R>); 1.3c Grotesque Reaching for a Cloaked Figure, BM-SS:123; 1.3d Pierrot Carrying Sunflowers, BM-SS:44, BM-FH:174 (R<); 1.3e Cloaked Man Holding a Bleeding Head, BM-SS:58, BM-LJ:147 (full page, R>); 1.3f Jester with a Head on a String and a Disembodied Hand Holding a Cupid, BM-SS:139, BM-LJ:72 (R<). PE coll.

Pierrot and Jester (Fig. 1.4, Zatlin 711), which is reproduced three times in the Bon-Mots in two different sizes, enacts a scene of inexhaustible signification as Chris Snodgrass has noted. There are unlimited conceivable interactions between the clown on the left, the exotic bird he is presenting, the puppet head protruding from the larger clown-puppet on the right, and this very clown-puppet to the point that “the limits of the drawing’s joke have become almost impossible to define.” As Snodgrass suggests, uncertainty as to whether the grotesques are alive, puppets, or even life’s puppets dominates. The joke rebounds to suggest to the viewer “the meeting of multiple mirror images, pet to pet, pet to puppet, puppet to puppet.” We find ourselves at a loss: “Or is the joke that they [pets and puppets] recognize this truth, but they are nevertheless compelled to play out the game? Or that even though they recognize it, we do not, and thus do not understand that we are puppets looking at puppets looking at puppets? And on and on. The boundary line between fake and real, artificial and natural, frivolous and serious, are so confused that there is no way to stop the meaning from sliding almost endlessly.”25 Beardsley’s love of theatre and music permeates these scenes that smack of drama, comedy, and farce. He himself performed at a very young age in drawing-room theatricals with his future actress sister Mabel. Here he hijacks and twists Pre-Raphaelite motifs by setting them in small arrangements and implausible combinations.

Fig. 1.4 Aubrey Beardsley, Pierrot and Jester, BM-SS:55, BM-LJ:132 (R<), BM-LJ:177. PE coll.

The peacock feather, with its combination of barbs, filaments, and ocellus, is another recurring image lifted from the Aesthetic store and twisted (Fig. 1.5a–c). Its power lies in its contradictions: it is from the natural world, and yet it is also a symbol of sophisticated fashion. By 1878, it had made its way into the most elaborate interiors, such as Whistler’s Peacock Room at 49 Prince’s Gate in London, decorated for collector Frederick Leyland, which Beardsley had visited. In the Bon-Mots, the peacock feather hovers over grotesque scenes: during the painful extraction of a tooth, treated in Japanese fashion (A Tooth Extraction, Zatlin 697), it floats, underlined by a double arabesque, in the background of the scene like a bird or an insect (Fig. 1.5a). As the headpiece for “Bon-Mots of Sydney Smith” in volume one, the absurd episode projects surreal meaning onto the section contents.

When a stylish lady smilingly walks towards the viewer in Woman in Evening Dress and a Fur-collared Jacket (Zatlin 739), a triple peacock feather underlines the deceptive perspective (Fig. 1.5b): the black dado strip adorning the wall pierces her bodice to form a high belt, yet also a slightly shifted dado fragment penetrating her coat. Both arrangements suggest that the peacock feather rules instability and the deflection of forms and plans, as if the ocellus’s iridescence irradiated the composition to undermine use of space and meaning and trick perception.

|

|

|

Fig. 1.5a–c Aubrey Beardsley, Bon-Mots grotesques involving a peacock feather. 1.5a A Tooth Extraction, BM-SS:17 (head vignette for “Bon-Mots of Sydney Smith”), BM-LJ:120 (R<); 1.5b Woman in Evening Dress and a Fur-collared Jacket, BM-SS:126, BM-LJ:1 (half-title vignette, R<), BM-LJ:87 (full page, R>); 1.5c Cat Chasing a Bird and Large Mice, BM-SS:7 (head vignette for “Introduction”), BM-LJ:84 (R<). PE coll.

In, for example, the vignette Cat Chasing a Bird and Large Mice (Zatlin 694), the cat is hunting the mice around a peacock feather (Fig. 1.5c). The feather’s stem vertically counterbalances the arabesque traced horizontally by the hunt, but also threatens to throw it off balance. Flying over the bristling cat, the bird deflects the graphic paradigm of the feather and encourages dispersal: the bird’s body carries an eye motif that mirrors the feather while its tail imitates the feather’s barbs. Its flight distracts the cat. It might chase the bird and forget about the mice. The mice may well go out to play, jests Beardsley – and one does, breaking free from the arabesque chase and darting towards a new curve, which ends in three small dots.

In Molière Holding Three Puppet Heads (Zatlin 716), the peacock feather turns into a triple stem mastered by Molière’s disembodied and enlarged hand (Fig. 1.6a). On the stems, three figures act out the comedy of a husband being cuckolded. Refined, the stems are speckled with ink dots in Three Grotesque Heads (Fig. 1.6b, Zatlin 723), a vignette reworking the same scene. In the first version, the characters are clearly recognisable: the cuckold wears horns, and his wife smiles at her lover, perhaps a painter, judging by his artist’s cap. In the second, the characters are more sexually and socially ambiguous. They certainly owe something to Jean-Jacques Grandville’s Fleurs animées (1846), Crane’s Flora’s Feast: A Masque of Flowers (1889), or even Redon’s La fleur du marécage, une tête humaine et triste (from the portfolio Hommage à Goya, 1885), but it is hard to say which figure is feminine and which masculine, and whether they belong to the real world or to the imagination of the grumpy old fool, out of whose horned skull they spring.

The vignette Two Grotesque Heads and a Winged Female Torso on Vines (Zatlin 724), which follows in Smith and Sheridan’s Bon-Mots, is yet another version of the same, by now abstract and fantastical (Fig. 1.6c): the basic pattern is identical, the cast similar, but the scene, resolutely fantastic and eroticised, features surreal beings.26

|

|

|

Fig. 1.6a–c Aubrey Beardsley, Three versions of the comedy of the cuckold husband. 1.6a Molière Holding Three Puppet Heads, BM-SS:70, BM-FH:119; 1.6b Three Grotesque Heads, BM-SS:92, BM-LJ:17 (R<), BM-FH:28 (R<); 1.6c Two Grotesque Heads and a Winged Female Torso on Vines, BM-SS:93, BM-LJ:180 (R>). PE coll.

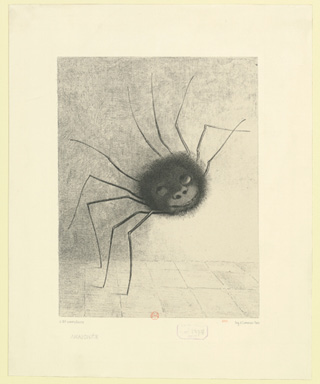

Another image that Beardsley tampers with is taken from Redon’s L’Araignée souriante (“The Smiling Spider”), a well-known image at the time, which featured in Huysmans’s À Rebours in 1884 as “a ghastly spider lodging a human face in the midst of its body” (“une épouvantable araignée logeant au milieu de son corps une face humaine”).27 Beardsley knew the novel well: he had modelled his lodgings at 114 Cambridge Street after the main character, Jean des Esseintes’s interior. Redon’s charcoal drawing of 1881 had in 1887 been lithographed in twenty-five copies (Fig. 1.7) and Beardsley is known to have seen them in Evans’s shop.28 A number of Beardsley’s vignettes draw on this image (Fig. 1.8a–e). The first is Spider and Bug Regarding Each Other (Fig. 1.8a, Zatlin 706), whose spider resurfaces in the larger composition La Femme incomprise (Zatlin 264). The first time it appears in the Bon-Mots, it is printed sideways, in the middle of an anecdote on Smith annoyed by a young man’s familiarity.29 The context grants it an illustrative tinge: the spider could well be Smith ogling the young man. Its half-humorous, half-threatening aspect calls to mind a satire of Redon’s work, portrayed as Pancrace Buret in Les Déliquescences d’Adoré Floupette, a fin-de-siècle spoof by Gabriel Vicaire and Henri Beauclair: “A giant spider which carried, at the end of each of its tentacles, a bunch of eucalyptus flowers and whose body consisted of an enormous, desperately pensive eye, the sight of which alone made you shudder; no doubt, another symbol.”30

Beardsley’s Spider and Bug Regarding Each Other reads at first glance like a simple, naturalistic scene: the spider stares with its single eye at a black insect, which looks up at it in dread. As in Redon, the fantastic image of the spider, as opposed to the rather realistic rendering of the bug, comes from its rotund body with legs and its glaring eye, embedded, as in several Redon lithographs, in a round form. Still, Redon’s spider has two eyes and a predatory mouth. It paces in indefinite space while Beardsley’s lies implanted in text. On closer examination, Beardsley’s minute episode is in no way naturalistic: the spider has six legs, like an insect, whereas it should have eight, like any arachnid worthy of the name (Redon’s has ten). As for the bug, it has… nine (four on one side, five on the other). It is therefore as improbable as the spider: we are presented with a double lusus naturae, two freaks of nature, which, like Floupette’s Déliquescences, is based on the sophisticated parody of artistic, not nature-based motifs.

Fig. 1.7 Odilon Redon, L’Araignée souriante (originally 1881), lithograph (1887).

© BnF, Paris

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1.8a–e Aubrey Beardsley, Bon-Mots grotesques with spiders and webs. 1.8a Spider and Bug Regarding Each Other, BM-SS:41 (repr. on the side), BM-LJ:13 (R<); 1.8b Head Overlaid with Bugs and a Spiderweb, BM-SS:131, BM-LJ:168 (R>); 1.8c Large Peacock Feather, BM-SS:190, BM-FH:145; 1.8d A Spider, BM-SS:177; 1.8e The Sun, BM-SS:113. PE coll.

Both the spider and its web multiply in Beardsley’s Head Overlaid with Bugs and a Spiderweb (Fig. 1.8b, Zatlin 741). Beardsley read French well and would have been familiar with the expression “avoir une araignée au plafond” (literally “to have a spider on the ceiling”), commonly used to refer to someone’s eccentricity or derangement as in “to have bats in the belfry.” There is a connection between spiders and madness in several other languages: spinnen means both “to weave” and figuratively “to ramble” in German, and in English cobweb can signify “subtle fanciful reasoning” as in “to blow away the cobwebs.” In Beardsley’s vignette, the wrinkled grinning human head beset by arachnids and insects reflects madness, melancholy, or arachnophobia, as much as it is a dusty mask on which spiders spin webs. How many spiders, webs, and bugs are out there? It is hard to say: a strand has just been cast from the right to the left, the whole scene may soon be covered in a spider’s netting, unless it itself becomes a part of a bigger web. The image keeps interpretation at bay.

Beardsley also connects the peacock’s feather to the spider’s net. In Large Peacock Feather (Zatlin 765), a plume turns into a ragged web (Fig. 1.8c). There is something alarming in seeing such an Aesthetic symbol fall apart, as if art did not hold together any longer in the face of nature and time. In further metamorphosis, A Spider (Zatlin 758) rather humorously wears a nose clip (Fig. 1.8d). Redon’s smiling, carnivorous beast has become a man’s head with an indolent, almost idiotic, gaze in its bespectacled eyes. Another grotesque mask set in curly filaments (Fig. 1.8e), oddly named The Sun in the catalogue raisonné (Zatlin 732), extends the motif, and the layout of the first volume grants it a function similar to A Spider. Placed centre page, both grotesques interrupt a joke.31 But it may well be that The Sun is merely born from a calligraphic doodle.

Such motifs, borrowed from his creative contemporaries and treated with subversive vivacity and humour, highlight the quick evolution and visual dynamism of Beardsley’s style. Once he uses a motif, it is then refracted and burgeons further. The vignettes initially derive from disrespectful appropriations, but then also stem from each other, pushing their visual potential to new extremes. They are flexible graphic gestures, open to suggestiveness. They hold in store playful wonders for the viewer despite their minute size. A graphic resource from which the artist may draw at any time, they parody or distance themselves from their subjects, including old established favourites of the grotesque tradition.

Unrecognisable Legacies

While seizing and distorting recent trends (Aestheticism, Japonisme, Pre-Raphaelites, Redon, Whistler), Beardsley also borrowed from older traditions. Several depictions refer to the origin of the grotesque, starting with the title-page frame (Zatlin 692), identical in all three Bon-Mots: an arabesque assortment of forms surrounds a spacious square held in reserve for the title lettering (Fig. 1.9). The grotesques lodge in the whorls and coils or emerge from them as in the finest tradition of the “nameless ornament,” inspired by the sixteenth-century findings at Domus Aurea, Nero’s excavated palace in Rome. Taken up and refashioned by numerous artists during the Renaissance, often engraved in sets, they were copied from one workshop to the next.32 Yet Beardsley replaces all the expected shapes with Aesthetic or Japanese components: three Whistlerian butterflies on the left, another on the right above a grotesque with a sunflower hat perched on a peacock, at the very top two tiny masks stemming like Japanese lanterns from a small monster, at the bottom a grimacing satyr with long leaves mimicking hair, and brawny, strapping grotesques in varied attitudes.

Fig. 1.9 Aubrey Beardsley, Title page for BM-SS (1893), identical frame for all three Bon-Mots. PE coll.

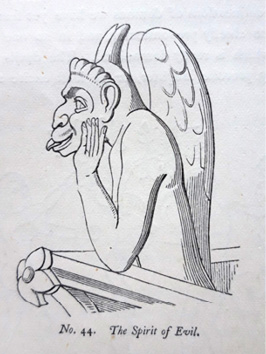

Borrowing from other sources and blending forms are characteristic of this protean art, in which even skilful or scholarly identification is often at a loss. The remodelling of forms, modernity of garb, attribute, and attitudes blur or erase their origins. Take for instance the horned Grotesque on a Camp Stool (Zatlin 801), printed only once (Fig. 1.10a).33 Beardsley uses as his basis a tower demon from Paris’s Notre-Dame, the very one depicted by Charles Meryon and known as Le Stryge in his 1853 portfolio Eaux-fortes sur Paris (see Fig. 3.9). Frequently pirated in woodcuts, its shape had already become a vignette as early as 1865 in A History of Caricature and Grotesque, Thomas Wright’s famous historical compilation, which Beardsley must have known. As opposed to other demons, which may be considered as ridiculous or even humorous, this grotesque embodies for Wright the very Spirit of Evil (Fig. 1.10b): “It is an absolute Mephistopheles, carrying in his features a strange mixture of hateful qualities – malice, pride, envy – in fact, all the deadly sins combined in one diabolical whole.”34

Fig. 1.10a–b Aubrey Beardsley reshaping traditional grotesques. 1.10a Beardsley, Grotesque on a Camp Stool, BM-FH:31. PE coll.; 1.10b F. W. Fairholt, Meryon’s Le Stryge captioned Spirit of Evil, in Wright, A History of Caricature and Grotesque, 74 (detail). Author’s photograph

Beardsley neutralises the demon through indolence. Its stuck-out tongue, single forehead horn, and hand on the cheek draw closely on the sculpted demon (whether the original, Meryon’s etching, its pirated reproductions, or Wright’s vignette), while the profile is finely outlined. As will be discussed further in Chapter 3, Beardsley himself would be photographed in 1894 by Frederick H. Evans in two poses advertised as grotesque, one adopting this very posture (see Fig. 3.10).35 And yet, the full evening dress, the court slippers, the aloofness of the horned grotesque, apathetically perched on its fold-up seat, transform it to the extent that even Zatlin, the great Beardsley scholar, missed its inspiration. She originally saw it as conveying either desire or inaction, and related it to Beardsley’s social criticism of his contemporaries.36 Due amendments were made in her catalogue raisonné thanks to Matthew Sturgis’s input.37

Triple-faced Grotesque (Zatlin 790) transforms into an egg-shaped figure (Fig. 1.11a) another monstrous being of earlier origin, reproduced by Frederick William Fairholt in Wright as a vignette captioned The Music of the Demon (Fig. 1.11b).38 The original is Erhard Schön’s Des Teufels Dudelsack (The Devil’s Bagpipe), a coloured woodcut from ca. 1530–35 and one of the best known caricatures in the history of the Reformation. Wright sees in it a satirical attack on Martin Luther, whose head features as the bagpipes into which the devil blows (Fig. 1.10c), an interpretation carried on in manuals and schoolbooks, yet recently contested.39 Beardsley’s new creation conforms to wry humour similar to Schön’s. He moves the grinning face that Schön had rendered on the devil’s pelvis on top of the creature’s head, with a Humpty Dumptyian scowl and lolled-out tongue. A smiling face appears now on the pelvis. The middle bagpipes have given way to a ludicrous sulking burgher staring ahead from under a tiny top hat. It is doubtful whether Reade’s relating it to “certain types of schizophrenic drawing” and Zatlin’s suggestion of Hokusai and Victorian hypocrisy are helpful.40 Instead, it is more useful to acknowledge the image’s heritage and see that Beardsley’s elusive modernity has taken over an old-style grotesque. He has radically transformed it by replacing the hybrid animal forms with clear-cut shapes, and adopting modern apparel together with languid, tongue-in-cheek postures.

|

|

|

Fig. 1.11a–c Aubrey Beardsley reshaping traditional grotesques. 1.11a Beardsley, Triple-faced Grotesque, BM-LJ:156, BM-FH:22 (R<). PE coll.; 1.11b F. W. Fairholt, Vignette captioned The Music of the Demon, in Wright, A History of Caricature and Grotesque, 252 (detail). Author’s photograph; 1.11c Erhard Schön, Des Teufels Dudelsack (ca. 1530–35), coloured woodcut. Wikipedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:

Teufels_Dudelsack.gif#/media/File:A_monk_as_devil’s_bagpipe_

(Sammlung_Schloss_Friedenstein_Gotha_Inv._Nr._37,2).jpg

In Beardsley’s work, innovation is both a matter of breaking new graphic ground and flouting tradition. He plays on the fine contours of outline, on curlicues, festoons and flourishes, threadlike lines, small dots, squiggles, doodles, feathers, bristles, tassels or strands of hair, which he mixes with the most predictable grotesque motifs: forked hooves, arrow-like tongues, horns, clawed paws, bristly pelts. His complex language also addresses nakedness. It subverts Victorian puritanism by introducing disturbing images of nudity and the human body. Beardsley implants on his grotesques a potpourri of human shapes, but figures rarely appear whole. Revamped organs, bones and limbs slide, shift and reposition. Nipples and breasts grow on cheeks, skulls, and occiputs. Bodies morph, genders mutate, and amputated limbs melt away. The little grotesques look at the viewer with a sneer, stick out their tongues mischievously, pull faces, and smile: they call for attention, invite deciphering, and then evade interpretation.

Curlicues, Letters, and Bodies

Beardsley himself slyly slipped in among his grotesques several self-portraits, in a mocking, buffoonish, even disconcerting manner, including as a foetus.41 This discreetly assertive but ironic presence, this demanding stance that promptly beats a retreat, is often accompanied by a Japanese mark, Beardsley’s signature, made up of three vertical strokes and a few dots (which become inverted hearts in Salome). Such a moniker accompanies, for example, a slumbering head on the extreme left of Four Heads in Medieval Hats (Zatlin 695), which is Beardsley’s own clandestine portrait (Fig. 1.12); it becomes a decorative motif on the vase in A Tooth Extraction (Zatlin 697, see Fig. 1.5a); or even, close to the foetus itself, it balances the abortive/phallic instrument in Two Figures by Candlelight Holding a Fetus, one of the grotesques most often reproduced (Zatlin 700, see Fig. 2.1).

Fig. 1.12 Aubrey Beardsley, Four Heads in Medieval Hats, BM-SS:13 (cul-de-lampe for “Introduction”), BM-FH:5 (R>). PE coll.

Other forms of Beardsley’s signature sometimes appear on his grotesques, as well as numerous scribbles, doodles, and squiggles lifted from penmanship manuals.42 Skilful engraver and calligrapher Edward Cocker (1631–76) and his intricate compositions in The Pen’s Transcendencie, or Fair Writing Labyrinth (1657) and The Pen’s Triumph (1658) acted as potential models for Beardsley. For Cocker, however, the perfection of writing proves the excellence of being, itself a reflection of the creator’s flawlessness mirrored in the long programmatic titles of his manuals. In the title page of The Pen’s Transcendencie, or Fair Writing Labyrinth, a rhyming quatrain comments unequivocally the title: “Wherein faire Writing to the Life’s exprest, | in sundry Copies, cloth’d with Arts and Vest. | By w[hi]ch, with practice, thou may’st gaine Perfection, | As th’ Hev’n taught Author did, without direction.”43 In The Pen’s Triumph, the short title is expanded as follows: “Being a Copy-Book, Containing variety of Examples of all Hands Practised in this Nation according to the present Mode; Adorned with incomparable Knots and Flourishes Most of the Copies consisting of Two Lines onely, and those containing the whole Alphabet; being all distill’d from the Limbeck of the Authors own Brain, and an Invention as Usefull as Rare. With a discovery of the Secrets and Intricacies of this Art, in such Directions as were never yet published, which will conduct an ingenious Practitioner to an unimagined Height.” All examples for exercising calligraphy are moral maxims or exhortations. “Flourishing” (prospering, thriving) and “making flourishes” go hand in hand, states Cocker, playing on the word’s double intent: “Some sordid Sotts | Cry downe rare Knotts, | Whose envy makes them currish | But Art shall shine, | And Envie pine, | And still my Pen shall flourish.”44

For Beardsley, on the other hand, calligraphy turns into doodles housing unexpected shapes (Fig. 1.13a–f). By knotting itself, the line comes to be a letter. The penmanship grotesque is meshed and breeds new forms in its twisted loops. The letters, when decipherable in the drawing, are also tails, moustaches, hair, breasts, muzzles, wings, and paws. Shapes echo the anecdotes described in the text. The Hairy Grotesque (Fig. 1.13a, Zatlin 752) may playfully reflect amusing accounts of Sheridan’s hopeless hunting, or again comment on wondrous rhetoric dispensed on futile subjects such as Foote’s dissertation on a cabbage stalk.45 Flourishes, instead of a head’s crown, in Man in a Calligraphic Hat with a Long Tongue and Breasts on his Cheek (Fig. 1.13b, Zatlin 727) may spiritedly picture Sydney Smith’s “absence of mind” or comment on the double meaning of “flourish” in a quip by Foote.46 Capped Head Gazing at a Fish (Fig. 1.13c, Zatlin 730) could represent Smith’s comment on platitudes or a topsy-turvy carousal, when turned sideways.47 The wriggly lines of Calligraphic Owl (Fig. 1.13d, Zatlin 756) compete perhaps with skilled rhetoric on endless bills.48 And the Calligraphic Grotesque (Fig. 1.13e, Zatlin 763) could be a mischievous gloss on a trick played by Sheridan.49 Such matches highlight the kinship between writing and drawing, both from a similarly writhing pen.

Likewise, flourishes stray into initials. The Long-necked Grotesque (Fig. 1.13f, Zatlin 742) with its extended neck, womanly chest, round hips, and peacock’s head, may have inspired Max Ernst.50 Hermaphrodite and maimed, it recalls the grotesques with endless necks in Hokusai’s Manga.51 It pulls a thread-like strand with its beak, and ends in two squiggles: one stands for its foot, the other for its hand, but may also be read as the designer’s own initials, AB. Just below, three small black rings form an elusive face under a bulging hairdo. AB himself signs his creature while glancing at the spectator, as if in awe at such boldness.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1.13a–f Aubrey Beardsley, calligraphic grotesques in the Bon-Mots. 1.13a Hairy Grotesque, BM-SS:160, BM-FH:86; 1.13b Man in a Calligraphic Hat with a Long Tongue and Breasts on his Cheek, BM-SS:101, BM-FH:101; 1.13c Capped Head Gazing at a Fish, BM-SS:109, BM-FH:142 (repr. vertically); 1.13d Calligraphic Owl, BM-SS:170; 1.13e Calligraphic Grotesque, BM-SS:186, BM-FH:98; 1.13f Long-necked Grotesque, BM-SS:133. PE coll.

Beardsley’s grotesques and flourishes recede into the background, such is their peculiarity and charm: while offering themselves to be scrutinised and deciphered as amalgams and debris of forms, they are also elusive. To speak of them in terms of a “grammar” (Fletcher)52 or “types” in a socio-critical perspective (“not individualized characters but types,” Zatlin),53 hardly tackles the issue since they do not form a reliable ensemble of meaning.

Often somatic and eroticised, the grotesques also bridge the difference between book and body. In his unfinished novel, Under the Hill, Beardsley’s description of the costumes and trappings of Venus’s guests borrow from his own grotesques. Even more significantly, Paul Chatouilleur De La Pine,54 his fictional painter (previously Jean Baptiste Dorat in bowdlerised published versions), actually adorns the bodies of the party guests themselves with grotesques:

Then De La Pine had painted extraordinary grotesques & vignettes over their bodies, here and there. Upon a cheek, an old man scratching his horned head, upon a forehead, an old woman teased by an impudent amor, upon a shoulder, an amorous singerie, round a breast, a circlet of satyrs, about a wrist, a wreath of babes,55 upon an elbow, a bouquet of spring flowers, across a back, some surprising scenes of adventure, at the corners of a mouth, tiny red spots, & upon a neck, a flight of birds, a caged parrot, a branch of fruit, a butterfly, a spider, a drunken dwarf, or, simply the bearer’s initials. But most wonderful of all were the black silhouettes painted upon the legs, & which showed through a white silk stocking like a sumptuous bruise.56

Aesthetics are reversible as the body turns into a book of tattooed grotesques, while the Bon-Mots use bodies as a fulcrum of monstrous application. The ultimate bid of the to-and-fro movement between body and book is Beardsley’s own body, pictured as monstrous in photographs (see Chapter 3). Such a bold move radically reviews the relation of images to text while opening a new perspective on fin-de-siècle print culture.

Wry Illustration and the Use of Language

Beardsley’s grotesques are generally seen as largely irrelevant to the text they accompany. Commenting on the first volume, The Studio suggested their symbolic rather than illustrative capacity: “as an attempt to symbolise the jokes rather than as pictorial illustrations they will repay study.”57 Despite this, there has been a tendency to neglect the booklets’ content when thinking about Beardsley, and consider his designs independently of the text. Reade, for example, offers an interpretation of The Birth of Fancy (Zatlin 748, named after Evans) by resorting to tentative psycho-erotic analysis of a presumable female despite the grotesque’s androgyny (Fig. 1.14):

A startling allegory perhaps of Romantic Music, whereby the grotesque “notes” are bred in the mind of Woman by the mental energy of Man, which fecundates her aural sense by means of an ear. This is one of the most effective of Beardsley’s foetal drawings, in spite of the calligraphic flourish for the sleeve, which academic draughtsmen might deprecate.58

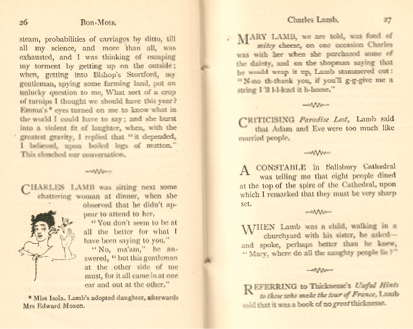

Fig. 1.14a–b Aubrey Beardsley, grotesque vignette The Birth of Fancy. 1.14a The Birth of Fancy, BM-SS:150, BM-LJ:26 (R<); 1.14b The same in context with the Lamb anecdote, BM-LJ:26–27. Courtesy of MSL coll., Delaware

Reade’s suggestion that this is an allegory of music (born perhaps in his mind from a jokey allusion of the related anecdote to “a wine composer and importer of music” in the first Bon-Mots)59 may seem arbitrary, especially since, when replaced in the second Bon-Mots, this grotesque has a clearly illustrative value. In the accompanying story, Charles Lamb replies to his chatty neighbour, who reproaches him for not paying attention to what she says, by noting that his own table neighbour is listening to her, almost despite himself: the words are entering one of Lamb’s ears and leaving through the other.60 Beardsley’s drawing reflects precisely this facetious response with his typical gender twist: Lamb has become sexually indeterminate while the plump grotesques have rounded hips and long black gloves together with masculine bald heads and cloven hoofs. Evans’s title, The Birth of Fancy, similarly occults their tongue-in-cheek relation to the text and vests the composition with an allegory.

In contrast, some of the foetal vignettes are wry, whimsical illustrations, as in the penmanship vignettes. They adorn the witty sayings of the children of the anthologised authors, not the authors themselves – the foetuses, as in Sheridan’s case at the very end of volume one. The last two pages offer young Tom Sheridan’s ripostes to his father on marriage and money next to the vignette of Fetus Figure Seated on a Peacock Feather with a Lily between its Feet (Zatlin 766, see Fig. 2.2a). The offspring’s clever replies match the genitor’s, Tom being “emphatically the son of his father.”61 In the vignette, the lily, the very symbol of innocence, ironically faces a foetus, a depiction of Tom as Sheridan’s enfant terrible, his pointy tongue standing for his sharp retorts (Fig. 1.15a). In another anecdote, Jerrold compares a minor poet to “the smallest of small beer over-kept in a tin mug – with the dead flies in it.”62 Set in the middle of the story, the same vignette of the wide-eyed, half-dead, half-alive foetus facing the lily grows into a wry illustration of Jerrold’s comparing the minor poet to “the kitten with eyes just opened to the merits of a saucer of milk.” (Fig. 1.15b). Several portraits of the fin-de-siècle generation, discussed in the next chapter, also refer to the foetus as offensive model. In the three Bon-Mots cases, instead of allegory, Beardsley preferred a witty literality, plumbing the potential of language as shown in his own self-portrait, A Footnote (see Chapter 3).

Fig. 1.15a–b Aubrey Beardsley, Bon-Mots foetal grotesques as wry illustration. 1.15a Fetus Figure Seated on a Peacock Feather with a Lily between its Feet, shown in context, BM-SS:192 (last page); 1.15b the same in context, BM-LJ:171 (R>)

Such divergence in interpretation stresses how hard it is to identify and evaluate the grotesques’ fin-de-siècle importance and meaning as opposed to their Romantic and post-Romantic heritage. The tradition of hallucination, reverie, or nightmare breeding monsters, the “sick dreams” (aegri somnia) or “dream of painting” (picturae somnium) was an explanation ingeniously advanced by Daniele Barbaro in 1567, at the height of what André Chastel named the “quarrel on the grotesques,” to justify the extravagance of such creations.63 Dreams and hallucinations were also favoured throughout the nineteenth century to justify incidences of the incongruous and ugly. Numerous texts, including E. T. A. Hoffmann’s Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier (1814–15), Aloysius Bertrand’s Gaspard de la Nuit (1842), Théophile Gautier’s “Le Club des Hachichins” (1851), the Goncourt brothers’ “Un visionnaire” based on Charles Meryon (1856), and Robert Murray Gilchrist’s “A Pageant of Ghosts,” the conclusive narrative of his Stone Dragon and Other Tragic Romances (1894), called up monsters and grotesques through the tropes of dreams, phantasms, or madness.

Something of this idea lingers in Fletcher’s approach to Beardsley’s vignettes, which he sees “as in a nightmare.”64 Yet the three Bon-Mots break away from such Romantic and post-Romantic tradition thanks to their humorousness and resourceful use of language. They are essentially a series of jokes based on verbal misperception, gibes founded on mix-ups, paronomasia, homophonies, verbal twists, and reductions of metaphors to their literal significance; they manipulate meaning and words. Beardsley’s images embody this farcical spirit. Rather than dismissing the textual quips as insipid (although some of them are indeed dull), we should rather ask whether it is not precisely from linguistic discrepancies (particularly by Lamb), characterised by mystification or nonsense (a particularly British genre familiar to all), that Beardsley draws practices that reinforce and enrich his innate inclination for paradox. His own collection of aphorisms, edited by Lane as “Table Talk,” is a testament to his interest in the practice.65

In such absurdist works, discrepancy occurs at several levels: between the grotesques and the modern or older motifs they rework, but also between text and image, reason and linguistic madness, sense and nonsense: no salt of the earth, but end-of-the-century spicing. To base three booklets only on paradox is a feat, but this is the essence of fin-de-siècle art. As a side trend (para) to a common or established belief (doxa), paradox is the perfect expression of grotesque as in Snodgrass’s refined definition:

The grotesque is a true paradox. It is both a fiction of autonomous artistic vision, operating by laws peculiar to itself, and a reflection of laws and contradictions in the world – paradoxically both “pure” and impure, autonomous and dependent, fictional image and mimetic mirror – in effect, incarnating the same contradictions that are central to art itself.66

It is then hardly surprising that young Beardsley should form his artistic language here, discovering at the borders of his grand illustrated books the heart of discrepancy. Such a limbo provides him with a luxuriant fauna. A few of his grotesques will resurface in large, well-known drawings. Most stem from experiments that promptly provide him with full command of his art, a fine virtuosity in such limited space, with such limited means.

Fin-de-siècle Choice Booklets, Mass Print Culture, and the “All Margin” Book

Marginal as they may be, Beardsley’s vignettes are a unique contribution to fin-de-siècle print culture. They appeared in two types of publications, which targeted different audiences in the 1890s: refined booklets appealing to bibliophiles and collectors of limited editions; and general-interest magazines for a large bourgeois readership. The three Bon-Mots, with their covers decorated by Beardsley, gilt top edges, and a large-paper edition of one hundred copies per volume, were designed as deluxe fin-de-siècle collectables. French publishing had favoured such dainty trifles, as in the cute Elsevier collections of short stories by Catulle Mendès, René Maizeroy, or Charles Aubert. Yet these were designed on an altogether different template, laid on Holland paper, and opened onto a content-related frontispiece engraving, beneath a colourfully illustrated cover.67 They were conceived as unique editions, never to be reprinted. Beardsley’s Bon-Mots strongly differed not only in their production but also in their irreverent content and irrational layout. And, notwithstanding the narrow reader category they targeted, they were frequently reprinted: Smith and Sheridan totalled five reissues by 1904.68

Moreover, they founded a type of book in Great Britain, the fin-de-siècle collection of (more or less memorable) past sayings decked with modern grotesques. Witness Dent’s Bon-Mots of the Eighteenth and Bon-Mots of the Nineteenth Century, again edited by Walter Jerrold, this time “with grotesques by Alice B. Woodward.” Woodward, who at the time exhibited fine watercolours and contributed illustrations to several collections and the illustrated press thanks to Joseph Pennell (Beardsley’s patron and first critic), would later be best known for her striking children’s books with black-and-white illustrations for Blackie and Son and the first illustrated version of Peter Pan’s story, The Peter Pan Picture Book (1907).69 She had adopted Beardsley’s distinctive black-and-white style but, unlike his, her grotesques were primarily illustrative. The astute publisher Dent used the template previously established with Beardsley for his three Bon-Mots to shape the two new booklets she illustrated. They looked identical to Beardsley’s from layout to cover and format while inside Woodward peppered the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century witticisms with her own illustrative grotesques. Cream covers replicating Beardsley’s design proffered “Grotesques by Alice B. Woodward” next to Beardsley’s fool with bauble and under his gilt peacock feather in duplicate colours.70 The typography and printer are identical (Turnbull and Spears in Edinburgh), the format (13.6 x 8.4 cm) and the dimensions of the printed page (9.2 x 5.3 cm) close. Only the number of pages varies (195 for the first volume, 189 for the second) as the publication was probably starting to lack material.

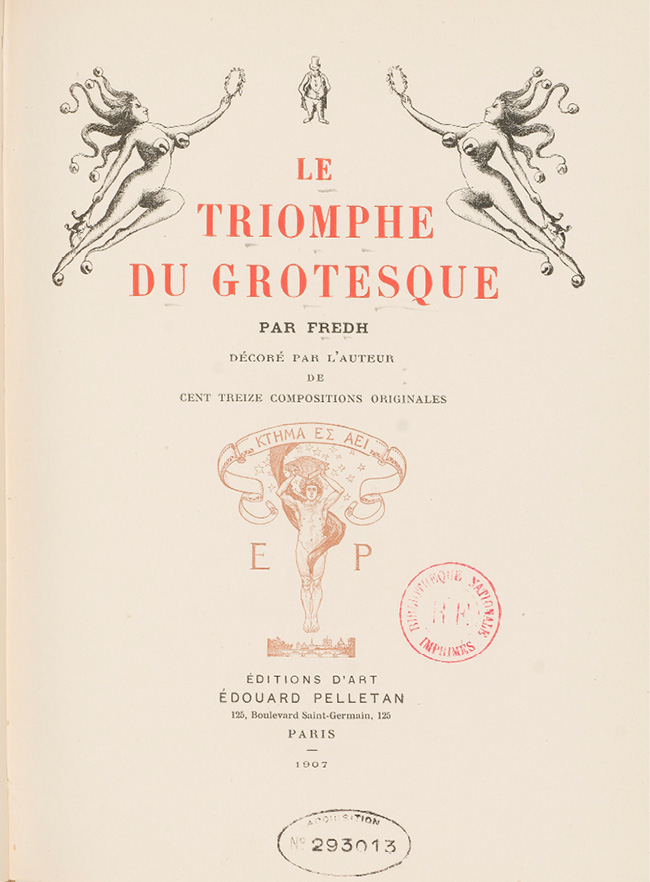

Placing grotesques in a beautifully produced and refined-looking volume shifts their meaning and creates a whole new category of publications. Irregularity and disorder are no longer an indefinable marginal game but they perform at the core. Édouard Pelletan, a publisher deeply committed to the revival of fine book printing along classical lines at the time, professed that “the true magnificence of a book must be understood as the superiority of the written work, the beauty of the illustration, the suitability of the typesetting, the perfection of the printing, the quality of the paper and the limited number of copies.”71 However, he also published grotesques: in 1907 he produced a deluxe edition of Le Triomphe du grotesque by Fredh, decorated with 113 original compositions. The cover and the identical title page are again paradoxical: two naked women, their hair, legs, and breasts ending in folly bells, hold out two laurel wreaths to a pot-bellied middle-class man strolling atop the page (Fig. 1.16). It is odd, to say the least, to see Thucydides’s famous phrase “KTHMA EΣ AEI” (“a treasure forever”),72 shifted from reported facts and history as the eternal asset of mankind to Pelletan’s trademark to crown a fin-de-siècle book on the grotesque.

Fig. 1.16 Fredh, Le Triomphe du grotesque, décoré par l’auteur de cent treize compositions originales (Paris: Éditions d’Art, Édouard Pelletan, 1907), title page.

© BnF, Gallica, Paris

The grotesque vignette also straddled new print territories. Beardsley was perhaps the first artist to extend this type of drawing into more general, high-circulation periodicals, with four of his vignettes published in St. Paul’s Magazine in March and April 1894. Catalogued as Music (Zatlin 333), Seated Woman Gazing at a Fetus in a Bell Jar (Zatlin 334), The Man that Holds the Watering Pot (Zatlin 335), and Pierrot and a Cat (Zatlin 336), they all read thematically and stylistically close to the Bon-Mots, although larger.73 Masked Pierrot and a Female Figure (Zatlin 933), first published on 28 April 1894 and in five subsequent issues in To-Day, the weekly “magazine-journal” founded and initially edited by Jerome K. Jerome, also relates to the Bon-Mots vignettes, with its Pierrot figure displaying a foetal head.

A series of Beardsley’s followers were quick to publish similar work, still mostly unchartered. Sidney Herbert Sime’s drawings for Eureka, also called The Favorite Magazine, or the Pall Mall Magazine echo Beardsley’s style.74 Between April and December 1899, Sime supplied the latter publication with a fine series of vignettes, accompanying the writing of George Slythe Street, the author of the Wilde satire The Autobiography of a Boy. Street, under the heading “In a London Attic,” published a news column that closed each issue. Another series of grotesques by Henry Mayer75 and Dion Clayton Calthorp76 were published a year later, also in the Pall Mall Magazine. Beardsley’s influence also spread internationally: Claude Fayette Bragdon’s marginal vignettes and full-page designs for the American Chap-Book, a magazine published in Chicago by Stone and Kimball and often referring to Beardsley, sometimes recall the Englishman’s grotesques.77 In Germany, the designs of Marcus Behmer were also inspired by Beardsley, as shown in the next chapter.

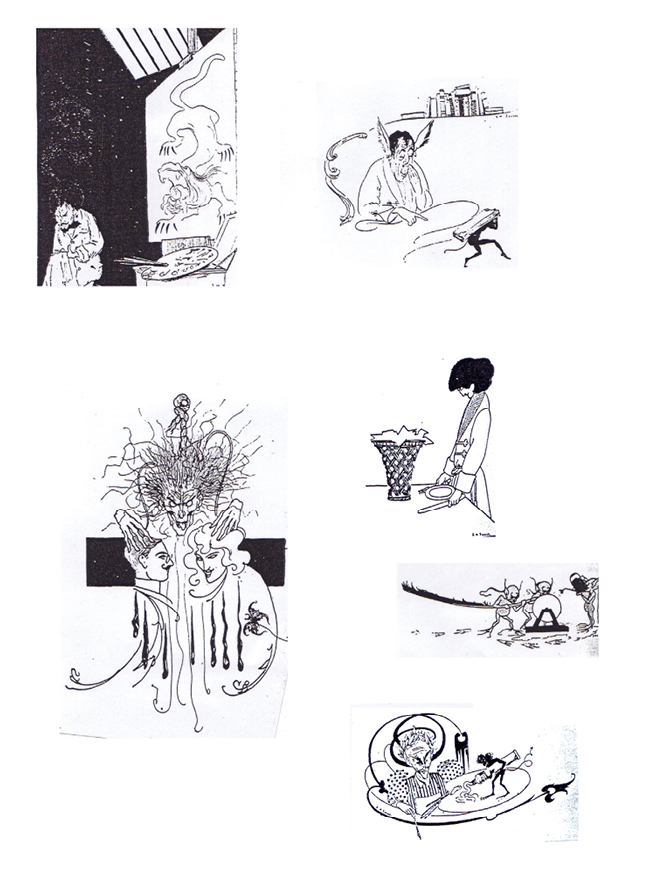

Sime’s case forms an endpoint beyond which it would be difficult to go. His vignettes frequently feature the drama of creation (Fig. 1.17a–f). In one of them, Sime has abandoned his palette in front of an unfinished painting and turns away (Fig. 1.17a); in another, a yawning author with donkey’s ears points to an arabesque-bordered void while an imp runs away with a manuscript (Fig. 1.17b); in another, an author at his table, lacking inspiration, verve, and cash, has nothing to sink his teeth into but his own wastepaper basket, filled with the abortive crop of his pen (Fig. 1.17c); in another, a company of miniature imps sharpens a gigantic quill on a grindstone (Fig. 1.17d); in yet another, a black fiend squeezes paint from a tube onto an oversized palette in front of a tiny laurel-wreathed artist, now enclosed in black whirls that end up in a peacock feather (Fig. 1.17e). As if to confess to Beardsley’s stimulus, a last vignette reworks the comedy of the cuckolded husband (Fig. 1.17f) as in Beardsley’s two puppets manipulated by Molière’s hand and its transformation (Zatlin 716 and 723, see Fig. 1.6a–b). Likewise, in his accompanying column, Street often admitted that he had nothing to say and simply let his pen wander.

Fig. 1.17a–f Sidney Herbert Sime, Grotesque vignettes published in the Pall Mall Magazine. 1.17a Sime Abandons his Palette (July 1899): 430a; 1.17b Yawning Author and Imp (April 1899): 576; 1.17c Author and Wastepaper Basket (July 1899): 430b; 1.17d Miniature Imps Sharpening a Gigantic Quill (June 1899): 288b; 1.17e Black Fiend and Tiny Laurel-wreathed Artist (July 1899): 432b; 1.17f Sime’s version of Beardsley’s Comedy of the Cuckold Husband (May 1899): 140b. Taken from the

Pall Mall Magazine

It is in this contrasting context, at once luxurious and cheap, sophisticated and silly, soliciting and denying meaning, that Beardsley’s vignettes inaugurated a new type of the book. Contrary to the tradition of the medieval or Renaissance grotesque, which acted as peripheral ornamentation in the margins of the main text,78 each Bon-Mots volume is a book that is, in essence, all margin. The medieval or Renaissance grotesque appeared in the borders and at the line ends of a manuscript or a book. Unruly curios at the fringe of pious texts, these earlier grotesques adorned psalters, missals, collections of exempla, and sermons. A striking example is the Book of Hours of Emperor Maximilian I, adorned by Albrecht Dürer and his colleagues. The demons and grotesques await – on the edges and rims – those who stray from the straight and narrow path set by the text, to either prompt the pious reader to return to the holy text, or perhaps to charm and entertain them in their moment of distraction. The Book of Hours richly adorned by Jean Pucelle for Jeanne d’Évreux (1325–28) measures less than 9.5 x 6 cm and is filled with a mixture of horror and grace. Its nearly 900 grotesques threaten to drown the pages and cover the prayers with their juxtaposed profanity, as Jurgis Baltrušaitis has shown.79

Beardsley’s three booklets have a similar sense of excess and contradiction, but unlike this medieval border art, they are a product of media-driven modernity. They featured in industrially-printed booklets and were created using the mechanical line-block reproduction process, spreading even further in mass-produced magazines. They offered contemporary types, fashionable clothing, and of-the-moment motifs. They were marginal by virtue of their futile, anecdotal and disjointed content, and their grotesques nestle in retorts and quips that rarely conquer a full page, resurfacing without system or plan. Such a book genre was well known to fin-de-siècle sensibility, from the large paper copies meant for bibliophiles to the end of the century’s fascination with the blank, unwritten page. It may seem odd to relate them to John Gray’s Silverpoints in 1893, which offered poems in minute italics on expensive laid paper and a distinguished elongated format. Yet, in an adroit comment full of wit, Ada Leverson invited Wilde to prolong Gray’s collection by a book she called “all margin:”

There was more margin; margin in every sense of the word was in demand, and I remember, looking at the poems of John Gray (then considered the incomparable poet of the age), when I saw the tiniest rivulet of text meandering through the very largest meadow of margin, I suggested to Oscar Wilde that he should go a step further than these minor poets; that he should publish a book all margin; full of beautiful unwritten thoughts, and have this blank volume bound in some Nile-green skin powdered with gilt nenuphars and smoothed with hard ivory, decorated with gold by Ricketts (if not Shannon) and printed on Japanese paper; each volume must be a collector’s piece, a numbered one of a limited “first” (and last) edition: “very rare.”

He approved.

“It shall be dedicated to you, and the unwritten text illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley. There must be five hundred signed copies for particular friends, six for the general public, and one for America.”80

Beardsley’s Bon-Mots are a bold realisation of this same idea, not due to the utmost blank of margins invading and cancelling the text, but by the fact that the conjunction of text and drawings is by nature marginal. The three booklets were undoubtedly born of the chance meeting of a publisher’s idea with the verve of a talented young illustrator. A literally off-centre triumph of the eccentric become central, the vignettes transform nonsense into a book, and an illustrated book at that. Grotesque, inane, facetious: paralanguages, where the “all margin” boldly takes permanent shape between deluxe editions, newspapers, magazines, and other ephemera, drawing its graphic sense from incongruous textual meaning.

1 Letter to E. J. Marshall, [autumn 1892], The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, ed. by Henry Maas, J. L. Duncan, and W. G. Good (London: Cassell, 1970), 34; letter to A. W. King, midnight 9 Dec [1892], ibid., 37.

2 Osbert Burdett, The Beardsley Period: An Essay in Perspective (London: John Lane, 1925), 103.

3 Letter to Marshall, [autumn 1892], The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, 34.

4 The smallest may be Capped Head Gazing at a Fish (Zatlin 730, see Fig. 1.13c), one of the largest is Winged Baby in a Top Hat leading a Dog (Zatlin 797, see Fig. 2.8c).

5 Linda Gertner Zatlin, Beardsley, Japonisme, and the Perversion of the Victorian Ideal (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 58–59, and Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley: A Catalogue Raisonné, 2 vols. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2016), I, 424, does not grant him any authority, either of plan or layout. See contra, Malcolm Easton, Aubrey and the Dying Lady: A Beardsley Riddle (London: Secker and Warburg, 1972), 176, on the Bon-Mots: “The publisher allowed him every liberty. He could decorate the page as he wished.”

6 Letter to Smithers, [ca. 5 Sept 1896], The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, 160.

7 Letter to the same, [ca. 20 Oct 1896], ibid., 186.

8 Brian Reade, Beardsley (London: Studio Vista, 1967); revised ed. (Woodridge: Antique Collectors’ Club, 1987), fig. 165–251 (hereafter abbreviated as Reade).

9 Ian Fletcher, Aubrey Beardsley (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1987), 53–56. Chris Snodgrass, Aubrey Beardsley, Dandy of the Grotesque (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 35, 165–66, 177–78, 181–84, 190, 198–99, 230–32.

10 The vignette catalogue was completed as an appendix to my 1993 PhD on monsters and the fin de siècle with descriptive titles. It was published, thanks to Paul Edwards, in a special issue of the Jarry-dedicated and confidential journal L’Étoile absinthe as “Les grotesques d’Aubrey Beardsley (Bon-Mots),” L’Étoile-absinthe. Les Cahiers iconographiques de la Société des amis d’Alfred Jarry, 95–96 (2002): 5–47, 132 fig., http://alfredjarry.fr/amisjarry/fichiers_ea/etoile_absinthe_095_96reduit.pdf

11 Zatlin, Beardsley, Japonisme, and the Perversion of the Victorian Ideal, 199.

12 “List of Drawings by Aubrey Beardsley, compiled by Aymer Vallance,” in Robert Ross, Aubrey Beardsley, with Sixteen Full-Page Illustrations and a Revised Iconography by Aymer Vallance (London: John Lane, 1909), no. 65.

13 Albert Eugene Gallatin, Aubrey Beardsley: Catalogue of Drawings and Bibliography (New York: The Grolier Club, 1945), 37, nos. 642–771. Despite the high number, this corresponds to a short global entry.

14 Ibid., 37–38, nos. 772–73.

15 The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, 161.

16 Chris Snodgrass, “Beardsley Scholarship at His Centennial: Tethering or Untethering a Victorian Icon?,” English Literature in Transition, 42:4 (1999): 363–99, reviewing thirteen titles. See also Anna Gruetzner Robins, “Demystifyng Aubrey Beardsley,” Art History, 22 (1999): 440–44, discussing the following five: Stephen Calloway, Aubrey Beardsley (London: V & A Publications, 1998); Zatlin, Beardsley, Japonisme, and the Perversion of the Victorian Ideal; Jane Haville Desmarais, The Beardsley Industry. The Critical Reception in England and France, 1893–1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998); Peter Raby, Aubrey Beardsley and the Nineties (London: Collins & Brown, 1998); Matthew Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley: A Biography (London: Harper Collins Publishers, 1998).

17 Zatlin, Catalogue Raisonné, I, 421–83.

18 See further on this, Évanghélia Stead, “Encor Salomé: entrelacs du texte et de l’image de Wilde et Beardsley à Mossa et Merlet,” in Dieu, la chair et les livres. Une approche de la Décadence, ed. by S. Thorel-Cailleteau (Paris: Honoré Champion, 2000), 421–57, fig. 1–12, and “Triptyque de livres sur Salomé,” revised and enlarged version in Évanghélia Stead, La Chair du livre: matérialité, imaginaire et poétique du livre fin-de-siècle, Histoire de l’imprimé (Paris, PUPS, 2012), 157–208, particularly 160–61, 163–64, 166–77.

20 Fletcher, Aubrey Beardsley, 54.

21 “An Apostle of the Grotesque,” The Sketch, 9:115 (10 Apr 1895): 561–62.

22 Arthur H. Lawrence, “Mr. Aubrey Beardsley and His Work,” The Idler, 11 (Mar 1897): 198.

23 Letter to E. J. Marshall, [ca. autumn 1892], The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, 34. Past & Present clipping pasted into a 9 Dec [1892] letter to A. W. King, ibid., 37: “Un jeune artiste anglais qui fait des choses étonnantes.”

24 Zatlin, Catalogue Raisonné, I, 438.

25 Snodgrass, Aubrey Beardsley, Dandy of the Grotesque, 166, author’s emphasis.

26 BM-SS (London: J. M. Dent and Company, 1893), 92–93.

27 Joris-Karl Huysmans, À Rebours (Paris: G. Charpentier et Cie, 1884), 85.

28 Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley: A Biography, 99.

29 BM-SS, 41.

30 Les Déliquescences, poèmes décadents d’Adoré Floupette, avec sa vie par Marius Tapora (Byzance: Chez Lion Vanné [sic for Paris: Léon Vanier], 1885), xl: “Une araignée gigantesque qui portait, à l’extrémité de chacune de ses tentacules, un bouquet de fleurs d’eucalyptus et dont le corps était constitué par un œil énorme, désespérément songeur, dont la vue seule vous faisait frissonner; sans doute, encore un symbole.”

31 The Sun is featured first, BM-SS, 113, among quips by Smith, and A Spider is featured second, 177, among witticisms by Sheridan.

32 See Nicole Dacos, La Découverte de la Domus Aurea et la formation des grotesques à la Renaissance (London: The Warburg Institute; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1969); Cristina Acidini Luchinat, “La grottesca,” in Storia dell’arte italiana, 11, 3, Situazioni, momenti, indagini, 4. Forme e modelli, ed. by Federico Zeri (Turin: Einaudi, 1982), 159–200; André Chastel, La Grottesque. Essai sur l’“ornement sans nom” (Paris: Le Promeneur, 1988); Philippe Morel, Les Grotesques. Les Figures de l’imaginaire dans la peinture italienne de la fin de la Renaissance (Paris: Flammarion, 2001).

33 BM-FH (London: J. M. Dent and Company, 1894), 31.

34 Thomas Wright, A History of Caricature and Grotesque in Literature and Art (London: Chatto & Windus, 1875), 74, fig. 44. First published (London: Virtue Brothers, 1865); trans. into French by Octave Sachot with a note by Amédée Pichot, 2nd ed. (Paris: A. Delahays, 1875).

36 Zatlin, Beardsley, Japonisme, and the Perversion of the Victorian Ideal, 203.

37 Zatlin, Catalogue Raisonné, I, 473.

38 Wright, A History of Caricature and Grotesque in Literature and Art, 252, fig. 145.

39 See Christophe Pallaske, “Luther – kein Teufels Dudelsack | zur Fehlinterpretation einer Karikatur,” Hypotheses: Historisch Denken | Geschichte machen, https://historischdenken.hypotheses.org/5409

40 Reade, 330, n. 229. Zatlin, Beardsley, Japonisme, and the Perversion of the Victorian Ideal, 204, and Zatlin, Catalogue Raisonné, I, 468.

41 See Reade, 325, n. 167; Milly Heyd, Aubrey Beardsley: Symbol, Mask and Self-Irony (New York: Peter Lang, 1986), 55–67; Zatlin, Beardsley, Japonisme, and the Perversion of the Victorian Ideal, 209–16; and my own analysis in the following chapter.

42 As recorded by Reade, 327, n. 189 and n. 191; 328, n. 199; and 329, n. 212.

43 The Pen’s Transcendencie, or Fair Writing Labyrinth (London: Samuel Ayre, 1657), n.p. See https://www.numistral.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k94009620.image

44 This aphorism is printed on the plate with calligraphic figures from The Pen’s Triumph (London: Samuel Ayre, 1658), n.p. See https://books.google.fr/books?id=iyICAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=fr#v=thumbnail&q&f=false

45 BM-SS, 160–62, see https://archive.org/details/bonmotsofsydneys00smit/page/160/mode/2up; BM-FH, 85–87, see https://archive.org/details/bonmotsofsamuelf00foot/page/86/mode/2up.

46 BM-SS, 101, see https://archive.org/details/bonmotsofsydneys00smit/page/100/mode/2up; BM-FH, 101, see https://archive.org/details/bonmotsofsamuelf00foot/page/100/mode/2up.

47 BM-SS, 109, see https://archive.org/details/bonmotsofsydneys00smit/page/108/mode/2up; BM-FH, 142–43, see https://archive.org/details/bonmotsofsamuelf00foot/page/142/mode/2up.

48 BM-SS, 170, see https://archive.org/details/bonmotsofsydneys00smit/page/170/mode/2up.

49 Ibid., 186, see https://archive.org/details/bonmotsofsydneys00smit/page/186/mode/2up.

50 Max Ernst, etching for Tristan Tzara, Où boivent les loups (Paris: Éditions des Cahiers libres, 1932). There were only ten copies made of the etching, on Japanese pearly paper. Repr. in Max Ernst, Écritures, avec cent vingt illustrations extraites de l’œuvre de l’auteur (Paris: Gallimard, 1970), 400. I thank Anne Larue for this suggestion.

51 Zatlin, Beardsley, Japonisme, and the Perversion of the Victorian Ideal, 183 and 187 (fig. 89), 204, and 207 (fig. 102).

52 Fletcher, “A Grammar of Monsters: Beardsley’s Images and Their Sources,” English Literature in Transition, 1880–1920, 30:2 (1987): 141–63.

53 Zatlin, Beardsley, Japonisme, and the Perversion of the Victorian Ideal, 202 ff.

54 Literally “Tickler of the Dick,” using French to both conceal and enhance the erotic meaning.

55 Beardsley had initially written “unborn children.” In the same chapter, the list of masks includes masks “of little embryos & of cats.” See Decadent Writings of Aubrey Beardsley, ed. by Sasha Dovzhyk and Simon Wilson, MHRA Critical Texts 10, Jewelled Tortoise 78 (Cambridge: Modern Humanities Research Association, 2022), 76 and 35.