3. A Dandy’s Portico of Portraits

©2024 Evanghelia Stead, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0413.03

Fame or Bust

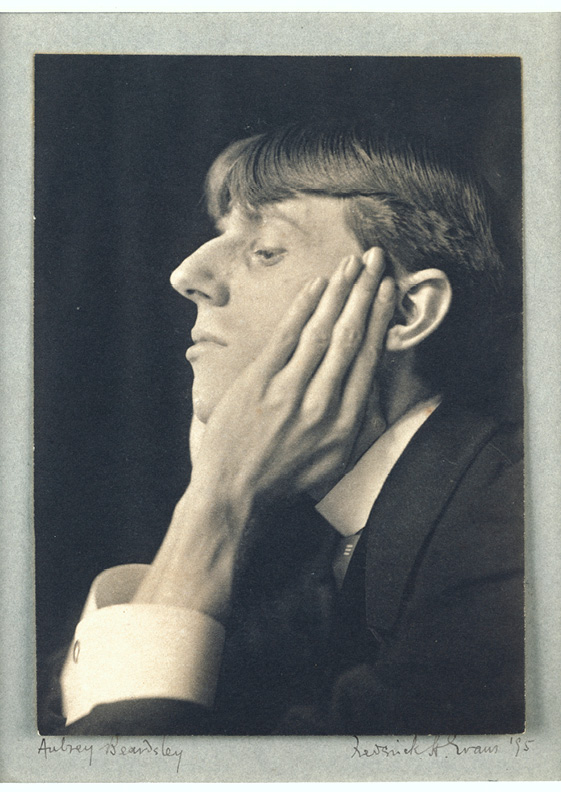

On leaving Westminster Abbey, little Aubrey is said to have quizzed his mother: “Mummy, shall I have a bust or a stained-glass window when I am dead? For I may be a great man some day.” When asked what he would prefer, he added: “A bust, I think, because I am rather good-looking.”1 A singular beauty, to say the least, enhanced by elaborate outfits and a dandified stance; and an early intuition of his own looming end. Beardsley would propel his tongue-in-cheek perception of himself onto the public stage via the emerging mass press, even projecting his own creative habits into his work. By drawing his tall thin candlesticks with tapering candles, he insinuated that he worked only by candlelight with curtains drawn. He repetitively shocked the Victorian ruling classes in interviews, conversations, and declarations, promoting his French posture and love of France. It takes several facets to make a bust and Aubrey had grasped three of them prematurely: scandal, rumour, and genius. To earn himself a statue and become the icon we all know, he owed it to himself to work quickly.

Five months before his twenty-sixth birthday, Aubrey Beardsley died of tuberculosis. In less than six years, he had established an impressive oeuvre, and marked a whole era as “the Beardsley period.” No recollection of the British fin de siècle was ever going to escape his oeuvre or his moniker, let alone his persona. In due course, he swapped the bust for a gallery of his own images. His visage has been remembered through his cabinet portraits, prancing or mischievous alter egos, and press photographs. His portraitists, from Max Beerbohm to Jacques-Émile Blanche, sought to represent the main qualities defined by their model: aplomb, caprice, and nerve. Aplomb translated into his self-confidence in the most demanding situations. Caprice, into his changeable moods and flippant behaviour. And nerve, into his insolent styling of himself.

The Gallery

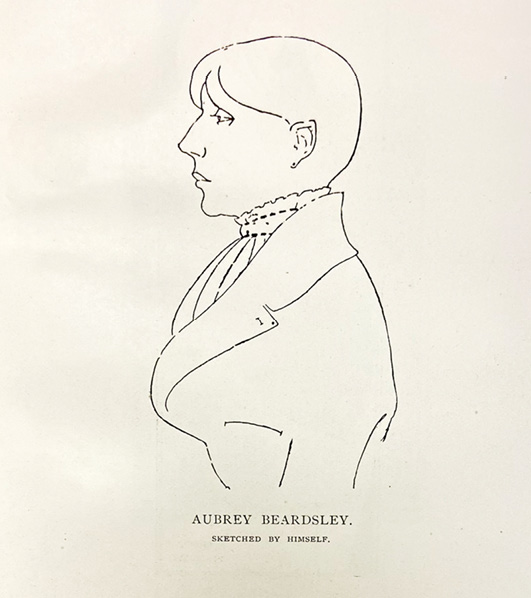

To start with, aplomb. Beardsley’s early ambition to one day be rendered in a bust is hinted in a self-portrait in profile, with contours sharply delineated in outline, on stark white, dating from March 1895 (A Portrait of the Artist, Zatlin 951). The figure’s erect head projects his gaze into the far distance (Fig. 3.1). His outfit, curtailed at waist level, swells exaggeratedly at the torso as if the figure was ready to stand in the sculpture gallery. Voicelessly, the portrait has turned into a museum bust on a pedestal, if not for the lace collar, shirred with a double black ribbon, and the pleated shirtfront (or is it a ruffle?). The garment takes the artist back in time and gives him an androgynous elegance. The style favours the linear harmony of the Old Masters, cherished by Beardsley, a trait that, Walter Crane believed, would give the subject construction and character.2

Beardsley’s portrait might well be styled on Beau Brummell brazenly wearing his Regency suit. In a well-known portrait by Richard Dighton (1805), Brummell with his Titus hairstyle wears a dark double-breasted cutaway tailcoat with a stand-up collar, an elaborately knotted cravat, and watch fobs. In Beardsley’s A Portrait of the Artist, there is no tailcoat, yet a fitted waistcoat; no watch fobs, yet a buttonhole to be adorned and a lapel pin; no Titus hairstyle, yet smooth hair parted at the front; and the high cravat has been tempered by a tiny earring. However, all in all, the wide lapels and the neat white linen are similar. Beardsley has modelled on Brummell a fin-de-siècle replica for posterity: his auspicious outline has made it to the frontispiece of more than one modern biography.3 And yet there lurks a hardly noticeable tension between petrification and action, immutability and mutability, as if the figure were to come to life and transform again.

Fig. 3.1 Aubrey Beardsley, A Portrait of the Artist (Mar 1895), repr. from Posters in Miniature, with the title Aubrey Beardsley. Sketched by Himself. Courtesy MSL coll., Delaware

The same occurs with Jacques-Émile Blanche’s splendid portrait of Beardsley in the National Portrait Gallery (1895), and the impression of movement it conveys. Strikingly stylish, boutonnière with flower, stick in gloved hands, the figure – in a grey suit, which brings out his light eyes, pallid skin, red hair and fine features – is firmly seated. Only the scenery behind him stirs. Yet, the portrait suggests motion and transformation, as when Walter Sickert captured Beardsley in 1894, turning away, hat and stick in hand, at the unveiling of Keats’s bust in Hampstead.4 Beardsley’s portraits seize an inherent versatility. They became progressively more disturbing, mischievous, and provocative in the printed black-and-white portraits and the photographs by Frederick H. Evans, which I discuss below.

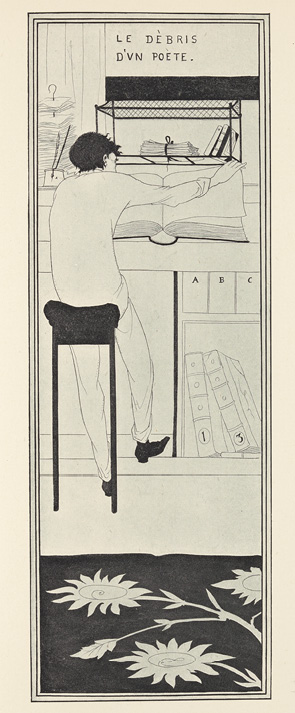

Caprice, then. In his first self-portrait, we face Beardsley’s back (Fig. 3.2). He is perched on a high stool at a desk with a massive open book – working, we assume, on some thankless task (he had to earn a living in an architect’s office, then an insurance broker’s, before he could establish himself as a designer). Written above him is the French inscription “Le Dèbris [sic] d’un poète,” which gives the drawing its title (Zatlin 244), literally, “The remains of a poet.” At first glance, we understand it as a pathetic appeal. It stems, however, from Flaubert’s caustic comment on Léon, Madame Bovary’s first lover, ready to spurn their love affair to better establish himself professionally and socially: “The most mediocre libertine has dreamed of sultanas; every notary carries within him the remains of a poet.”5 Beardsley had read Flaubert’s novel in the original and the quote brings with it the ironic barb Flaubert aimed at Léon. Apparent self-pity conceals a twist. The ostensible defeatism and resignation carry no despair, quite the opposite. It would not take long before such mocking self-commiseration would become bravado, panache, with the growing aura of scandal, of that Victorian din and clamour which Beardsley took advantage of. The distanced character would gradually appear centre stage, and then quickly turn into a cheeky celebrity.

Fig. 3.2 Aubrey Beardsley, Le Dèbris [sic] d’un Poète (June 1892), Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK, repr. from Uncollected Work, no. 12. Courtesy MSL coll., Delaware

Beardsley certainly struck poses, not necessarily to show off, nor simply to have fun. His self-portraits have nerve. In a game of heads or tails, it could be argued that the Brummell bust (heads) is the obverse of the reversely monstrous portraits (tails): a provocative alternative to dandyism. If dandyism relied on good looks, Beardsley had a gaunt, hardly attractive physique. Yet sophisticated and urbane ugliness, relying on the din of the metropolis, would be an alternative to dandyism, also resonant with nascent psychology and its allusion to Jekyll and Hyde.

Appearance and New Aesthetics

Beardsley was very tall, cut a sharp thin profile, and spoke in a dry, staccato voice. He dressed primly, and moved with a bouncing gait in a nervous, agitated manner. Oscar Wilde described “a face like a silver hatchet, and grass green hair.”6 Most terms referring to his persona and work gravitated around strange, weird, quaint, peculiar, at times freakish. Feverishness was another recurrent descriptor: a liveliness that changed from haste to abruptness as he moved from the most recent work to the next, from one style to the other. He gloated when he shocked, overflowing with capricious mischief. To his near twin, Beerbohm,7 he had given a photograph of himself by Frederick Hollyer, caricatured in watercolour (Self-caricature, Zatlin 939).8 And Beerbohm satirised him nine times, sharpening his angular profile, magnifying his restless-fingered hands, twisting his crossed legs high. He made him drag a doggie on wheels in response to his own skit as an angelic babe with stylish puppy at his heels (see Fig. 2.8c). Beardsley knew he didn’t have long to live. To amaze and grandstand, he started with his close friends before his renown reached the general public. He determined to be a dandy with composure.

From 1892, Beardsley started to see dandyism in a more intellectual light relating to his Francophilia. Bust apart, his dandyism was no longer that of Brummell, but of Charles Baudelaire as Matthew Sturgis recorded. Not that he was turning away from the trappings of dress: at the spring 1893 opening of the Parisian Salon, he sported a grey suit, grey gloves, a golden tie, a stick, and a straw hat; he would have loved “a white overcoat with a pale pink lining” from his first Yellow Book earnings in 1894.9 But, like Baudelaire in his essay on Constantin Guys, “The Painter of Modern Life,”10 he understood dandyism, to use Baudelaire’s words, as “the last glow of heroism in decadent times,”11 when heroes had been overpowered by the growing masses. Modern heroism lay no more in physical strength and moral integrity but in artful difference. The scrupulous distinction of spanking clean attire, the attention to grooming and dress code “were for the perfect dandy but a symbol of the aristocratic superiority of his spirit.” Sartorial feats had become intellectual. Baudelaire would have recognised in Beardsley the desire to enjoy the “pleasure of astonishing and the haughty satisfaction of never being astonished.”12

In order to astonish, Beardsley had drawn lessons from James McNeill Whistler’s public assertions through his famous lawsuit against John Ruskin, control of his work, artistic philosophy, and Wilde’s parade of aphorisms. He revered wit and witticisms, as evidenced by his polysemous captions and multifaceted statements. The illness that plagued him, the bodily appearance that might have been a disservice to him, he made glow and shine in weirdness. Invited to give a speech on the occasion of the Yellow Book’s launch, he began with “I am going to talk about an interesting subject, myself.”13 His gallery of portraits playfully introduced this particular self as a monster.

Margin in Books and Minsters

Several of Beardsley’s self-portraits ironically celebrate a monstrosity apparent from his physical appearance, in feigned attitudes, scripts in drawings, or his own captions. To display one’s self in one’s own work as an anomaly, to stage oneself as a monster, implied both a jeering distancing from one’s identity, and a consented banishment from the rest of humanity, even the artistic community. The dominant culture took normality for granted, and desired its artists to present an idealised version of themselves. Instead, Beardsley constructed and delivered images, which, at their heart, are not only provocative but also humorous. As in the foetal likenesses of fin-de-siècle dandies and Decadents discussed in the previous chapter, the margin this artist claimed was not so much social as artistic. It was determined by the disparity he created between the audience’s desires and what he delivered. In the images discussed here, margin frequently becomes a play on distance and dimensions. Yet, it is also a border, a fringe that calls upon the history of culture and aesthetics. It may be defined in relation to a text, in terms of printed pages, or to a piece of architecture that relates to text in multiple ways. It frequently refers to two monuments of culture, opposed in size but linked in the imaginary: the book and the cathedral.

Margin traditionally welcomes monsters and grotesques, which brim and flourish at the rim of Western books, from the babewyns of medieval manuscripts as Jurgis Baltrušaitis has commented,14 to Albrecht Dürer and his fellow artists’ famous Randzeichnungen.15 These were interlaced motifs and marginal drawings in Emperor Maximilian I’s Book of Hours, interspersed with scrawls, oddities, and grimaces. They had been lithographed by Johann Nepomuk Strixner at the beginning of the nineteenth century and fascinated the Romantics.16 The margin plays spontaneous home to grotesques, André Chastel’s “nameless ornament.”17 It appears in the very first example analysed by Chastel, a passage from Montaigne’s Essays (chap. XVII). Chastel goes on to state in his study: “We are literally at the margins, and margins are always and everywhere the realm of permissiveness.”18

And it is again in the cathedral’s periphery and decoration that the gargoyles and monsters reside, storming that medieval monument often dubbed the “great book of stone.” While the minster is erected as the figurative sum total of the Christian doctrine, the demons and monsters, discarded from the didactic programme, inhabit its borders, protuberances, and pinnacles. The parallel is arresting: a paper margin, filled with demons, tritons, and aberrations for the book; a sculpted margin, full of gargoyles and chimaeras for the cathedral. And the relation between the two is no invention. The striking metaphor of the cathedral as book of stone appeared in the writings of Saint Bernard of Citeaux and still survives in commonplace forms today. In 1884, Ruskin called the Amiens Cathedral “the Amiens Bible,” cementing a direct analogy between architecture and the book. The façade of any cathedral is a “written page” (to be deciphered) and the monsters “words uttered by [the] sculptors” in Joris-Karl Huysmans’s short text “The Monster.”19 By the end of the nineteenth century, the striking image had become a cliché, as Jean de Palacio has shown.20

As we shall see in this chapter, Beardsley claimed to be a part of both the book and the book of stone. The press saluted him as “An Apostle of the Grotesque,”21 indeed the prophet of a new era, illustrating his assertion: “If I am not grotesque, I am nothing.”22 Whilst Beardsley made these statements to shock the media, his actual artistic practices were far more revolutionary than a soundbite. By setting himself up as an anomaly, he attempted to reshape the artistic canon through wit, aloofness, and discrepancy. By deliberately placing himself at the margin of cultural monuments (either book or cathedral), he inverted the relationship between main text and note, whole and part, leading and secondary discourse, magnum opus and fragment. Yet, concurrently, the force of jest at the heart of his work led to both their parody and their imitation by others. Beardsley’s self-portraits inspired other works, which also referenced the period’s key texts such as Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray that poses, among others, the crucial question of representation. These parodies highlight both the subtlety and power of Beardsley’s humour and its manifesto-like potential.

This chapter also looks at portraits taken of Beardsley by the photographer Frederick H. Evans, in which the artist poses as a cathedral gargoyle. Such images reassess the artist’s relationship to the monument and ironically comment on the ancient practice of the “signature,” updated in the nineteenth century. By magnifying the monstrous detail, the photographs achieve a form of climactic expression that heralds modern practices closer to us, for instance using one’s own body in art or as art. The humour of this series of fantasised or ludicrous images of the self, against an explicit background of monstrosity, calls in fine for a revision of cultural hierarchies.

In what follows, both book and minster appear in typical fin-de-siècle form. The book, regularly seen as a major testimonial, is swapped for ephemeral periodicals, although these may be choice art and literature reviews playing with the idea of the book (such as the Yellow Book). Thanks to the formidable expansion of the press, a new media era had risen. New printing technologies had enhanced Beardsley’s linear graphics. The periodical press had made his work known, and he would make a gallery of self-images to match. As for the cathedral, it turns out to be ultimately fragile, conquered by its most anomalous parts.

Humour in Periodicals’ Borders

Fig. 3.3 Aubrey Beardsley, Portrait of Himself (late summer–autumn 1894), repr. The Yellow Book, 3 (Oct 1894): 51. Courtesy Y90s

Portrait of Himself (Fig. 3.3, Zatlin 906), the first of Beardsley’s cheeky self-portraits in periodicals on gaining fame, was published in 1894 in the third volume of the Yellow Book when Beardsley himself was its art editor.23 It already shows a man who scrutinises his ego ironically. There is a dry detachment in the capitalisation of the caption “Himself,” a virtually honorific title, which speaks of the conflict between the artist and his persona. As if to enhance its own oddity, the drawing bears in French the inscription “Par les dieux jumeaux tous les monstres ne sont pas en Afrique” (“By the twin gods not all monsters are in Africa”), the opening sentence of Cyrano de Bergerac’s comedy Le Pédant joué (1654). An 1895 interview with Beardsley would also picture him in his black-and-orange studio with “an exquisitely bound exemplaire” of this very comedy,24 known for its creative language, numerous sexual allusions, impracticable communication, bizarre scenes, and monologues with no connection to the plot.

The uncurved lettering calls to mind chiselled antique stone slabs or commemorative pillars, bringing Beardsley into kinship with a far-off Antiquity peopled by monsters and prodigies. The twin gods may refer to Castor and Pollux, the Dioscuri, literally “sons of Zeus,” a couple accumulating ambiguities. The twin nature of the half-brothers is based on irregular birth: Castor and Pollux spawn from one of Leda’s eggs, inseminated on the same night by Zeus metamorphosed into a swan and by husband Tyndareus. Although sharing the same egg, the twins are distinct, Pollux being considered Zeus’s son, and Castor Tyndareus’s. Divided between divinity and humanity, they oscillate, even after the death of one of them, between immortality and the underworld. As for Africa, it refers (like Libya, often used as a synonym) to that margin of the ancient world that was seen to harbour “abnormality,” which many a weird and wonderful ancient travelogue had offered to “civilised” eyes.

Inversely, by way of antiphrasis, Portrait of Himself presents the artist, already a hot new topic in the London press, as a modern-day monster at the heart of the metropolis, in a sumptuous and ornate setting, far from exotic lands. The oversized décor contrasts with his microscopic figure. Dressed in a nightgown, he peeks beneath an enormous frilly nightcap with ruched brim and the quilt of a giant bed, a catafalque or throne, whose canopy is adorned with formal bouquets and suggests the oriental skirts of an overbearing female. Despite the affectation of the capitalised “Himself,” the artist is losing substance within the invasive folds of fabrics and drapes which seem to undermine his virility. The bold perspective grants him a choice place in the giantess’s lap (the bulging canopy). Miniaturisation is equally disturbing: the plump forms of a she-faun, both arms severed, under a dishevelled grinning head, adorn the aptly placed bedpost. An equivocal ornament, she acts as a symbol of the artist’s ambiguous sexuality, and her amputation signals removal or loss of some part of his body. By playing on the margins of the civilised world (“Africa”) and the distance from Antiquity, humour brings back to the hub of civilisation an artist not only mockingly monstrous but also minuscule.

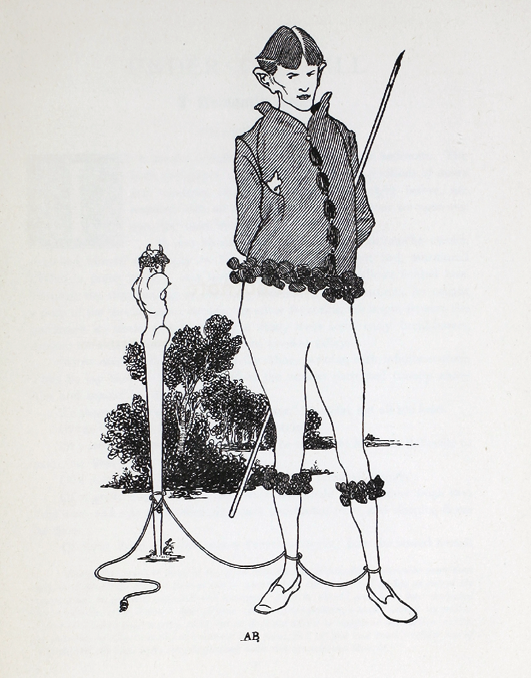

Barely two years later, Beardsley re-styles his own self in a new portrait and titles it A Footnote (Fig. 3.4). After John Lane had dismissed him as art editor of the Yellow Book, he again signs his likeness, this time in the Savoy (Zatlin 1004r).25 The artist has now matured. Grown to a spectacular size and equipped with a gigantic quill, he figures centre stage. Although moved to the open, he sports the same refined dress as in Portrait of Himself, in clinging breeches and a fancy open-necked shirt fringed with flowers. Yet his monstrousness and flippancy are brazenly on display. The she-faun has tailed him, converted into a horned and armless herm fetish, a deity of boundaries, with protruding, rounded hips, his muscular back turned to us. The artist himself is a faun: his ears are exaggeratedly sharp and pointed, his gaze slides under a middle parting over an impish triangular face. Devoted to the small, maimed Pan, he is tied by a rope to his pillar, a replacement for the bedpost. His tether gives him little leeway or room for manoeuvre, and he offers his custodian a slanting, pouting glance. We may have expected the herm god’s blatant sexuality to state itself to the fore, but the statuette shies away. Playfully, the monstrosity – and the artist’s persona – recalls its ties to the margin, obvious in the title’s pun on “footnote.” Indeed, the Savoy drawing is a gloss, a note, a below-the-text comment on a previous achievement, the earlier Portrait of Himself.

Fig. 3.4 Aubrey Beardsley, A Footnote (by last week of Mar 1896), repr. The Savoy, 2 (Apr 1896): 185. Courtesy Y90s

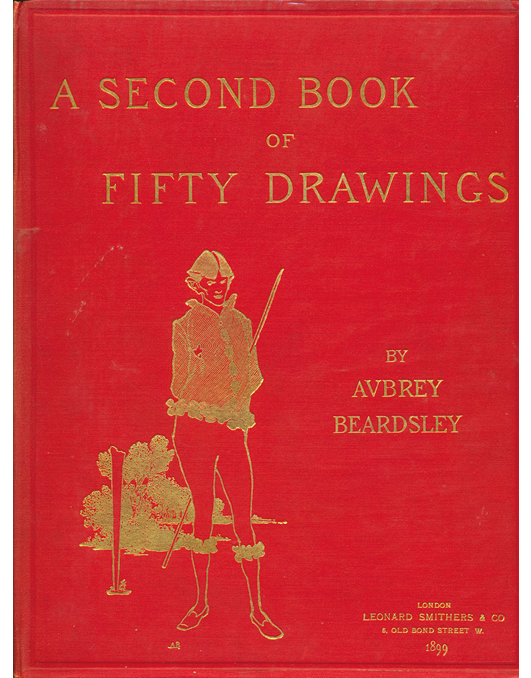

Both self-portraits possess a status of oblique manifesto, each to its own fin-de-siècle periodical. They provokingly set the artist within the periodical he edits, as a challenging part of his aesthetic and artistic choices, claiming monstrosity as an asset, and at the same time fuelling press excitement. Yet the Savoy drawing is also a literal interpretation of the title’s two components, foot and note, a “footnote” materialised in the rope chaining the artist to Pan’s pillar by the ankles. A footnote figures by definition at the bottom edge of a text, just as the cord secures the artist’s foot. By reducing the figurative expression to its literal sense, humour is now based on the margin itself. Together they have brought the monstrous artist to the forefront with a bump. It is worth noting, that such humour went largely unnoticed. The image, considered shocking, was censored as early as 1899, the god’s torso erased, and the rope removed. Gilt stamped, what remained of it featured on the red cover of A Second Book of Fifty Drawings, published 1899 by Smithers, who was not a man shy of taking risks. Now Beardsley seemed to pose with an inexplicable unadorned stake on the left (Fig. 3.5).

Fig. 3.5 Cover of A Book of Fifty Drawings by Aubrey Beardsley (London: Smithers, 1897) with A Footnote altered. Courtesy MSL coll., Delaware

Mock and Genuine Impersonations

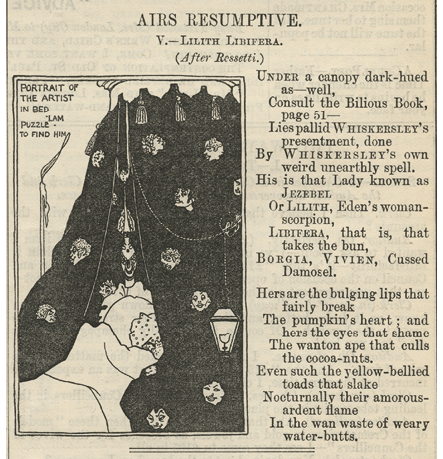

Fin-de-siècle art was often steeped in pile-on parody, and Beardsley’s Yellow Book self-portrait inspired further takes on the artist’s contrived monstrosity. An unsigned spoof of Portrait of Himself by Edward Tennyson Reed (Fig. 3.6) was published in Punch, the humorous weekly, in the month following the Yellow Book issue. Adopting playful pseudonyms, such as Mortarthurio Whiskersly or Whiskersley, Danby Weirdsley, or “Yellow Book” Impressionist, Reed regularly reworked Beardsley’s drawings between 1893 and 1895, offering inflated distortions which often out-parodied parody to form a body of work parallel to Beardsley’s own and rich in alternative significance. He aped Beardsley’s style but also promoted it, contributing to its spread and ascendancy. In this drawing, the ornamental posies on the drapes have turned into scowling faces that besiege a frightened figure cowering under the sheets. Beardsley’s own grimacing creatures now ogle the artist in bed. His wickedness attacks its creator and his monstrous identity is both dependent on his graphics and ruled by them.

Fig. 3.6 [Edward Tennyson Reed], unsigned pastiche of Beardsley’s Portrait of Himself, repr. Punch, or, the London Charivari, 107 (3 Nov 1894): 205 (detail). University of Minnesota Libraries

Yet, despite the clever drawing, what accompanies the image reads flat, as if the humour permeating the original were its secret impervious force, tolerating distortion only at the cost of demoted meaning. The inscription “Portrait of the Artist in Bed-lam, puzzle – to find him” propounds an easy joke: Bed-lam refers first to the bed, then to Bethlem Royal Hospital, nicknamed Bedlam, the famous psychiatric asylum. Moreover, an unsigned sonnet supplements the image, Owen Seaman’s “Lilith Libifera,” which, under pretence of a pastiche of “Lilith,” one of Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s most beautiful sonnets,26 parodies Rossetti’s “Sibylla Palmifera” closely associated with “Lilith.”27 Both works were composed in parallel to the homonymous Lady Lilith (1866–68) and Sibylla Palmifera (1866–70), two oil paintings on canvas with nearly identical dimensions, indeed considered a diptych by Rossetti himself, who renamed them “Body’s Beauty” and “Soul’s Beauty.” In Punch, they no longer point at beauty, but ironically at monstrosity, both of body (as in Portrait of Himself) and soul (as in the bed drapes’ distorted imaginings). Pointedly, Rossetti’s “Sibylla Palmifera” glorified beauty in a broad allegory.28 The beard (of Beard-sley) being replaced by whiskers in the pastiche, “Lilith Libifera,” ascribed to Whiskersley’s parodied portrait, now crowns her a monster in the place of Beauty. As in the reworked drawing, in the poem next to the skit, she is surrounded by abnormal spawn, exclusively female.29 The female figures targeted are not, however, Beardsley’s but Rossetti’s, whose several paintings and poems are easily recognisable. “Cussed Damosel” parodies “The Blessed Damozel,” “Borgia” refers to the watercolours Borgia and Lucrezia Borgia Administering the Poison-Draught, and Vivien is a favourite figure of the Pre-Raphaelites (including Frederick Sandys, Edward Burne-Jones, and Henry R. Rheam). Seaman’s heavy parody has, moreover, little in common with Beardsley’s witty humour. In its vehemence, pompous style, and triviality, it aligns satirised images and a lewd toxic bestiary. It reads as a war machine. Originally marginal and idiosyncratic, oddity has become outrage.

Beardsley’s drawing fared much better in the hands of Hans-Henning von Voigt, known as Alastair, a man of letters, polyglot translator, set and costume designer, dancer, actor and circus performer, who himself loved theatrical attitudes and posturing.30 His version helps to highlight the image’s rich semantic potential when combined with an equally rich text. In a drawing from the 1920s (Fig. 3.7), in which Portrait of Himself is unmistakably the source of inspiration, a figure lies again in bed with plume-decorated drapes and elaborately carved bedposts. Is this yet another monster?

Fig. 3.7 Alastair, The Picture of Dorian Gray or Dorian Gray in Catherine de Medici’s Mourning Bed (early 1920s), Victor and Gretha Arwas coll., London, UK. Courtesy and © Gretha Arwas

The title, given by Victor Arwas as The Picture of Dorian Gray31 and also known as Dorian Gray in Catherine de Medici’s Mourning Bed, endorses the guess, yet designates not the creator but the creation, conceived here again in between text and image. Alastair knew Beardsley’s and Wilde’s work well. He provided drawings for three editions of Wilde’s writings, namely The Sphinx Decorated by Alastair (John Lane, 1920),32 Salomé republished in the original French (Les Éditions G. Crès et Cie, 1922), and The Birthday of the Infanta in French translation (The Black Sun Press, Éditions Narcisse, 1928). He went on to translate Wilde’s novel into German in 1948,33 and he certainly picked the title in full awareness. However, Dorian Gray’s picture is not only a portrait, as claims Le Portrait de Dorian Gray, its French title in translation, but also a work of art, a representation infused with its self-governing life. Alastair’s drawing is no mere illustration either, but an opus in its own right. Its author, a multi-talented draughtsman-cum-polyglot-translator combines a complex fin-de-siècle novel34 and the monstrous overtones of Portrait of Himself that he repurposes in a composition halfway between beauty and monstrosity. The bedstead’s she-faun has been replaced by an hourglass in which time drifts unescapably – a key motif in this image since the portrait earns Dorian eternal youth, bringing time and age to an abrupt stop. Once on canvas, Dorian, the epitome of beauty and grace at the beginning of the novel, takes on every alteration of age, and Wilde presents his picture as “the hideous thing,” “this monstrous soul-life,” “the living death of his own soul.”35 As in Seaman’s pastiche, humour has here utterly vanished, along with eccentric life in the margins. The character (or his representation) features centrally as a half-body figure. Still, in strong contrast to Seaman’s polemic, Alastair crowns a beautiful monster hallowed by a fin-de-siècle oxymoron, a subtle summary of the novel, and an icon on his deathbed.36

Fin-de-siècle Minster Signatures

Such a complex relationship between the monster and the artist is intensified when we move from paper to stone. The cathedral or abbey allows for a new enquiry on the relation of artist and monument, part and whole, fraction and entity in the fin-de-siècle imaginary, as evidenced in texts by Félicien Champsaur and Jules Vallès, with Victor Hugo’s Notre-Dame de Paris novel as background. “Signature” by Champsaur, a sonnet first published in his novel Dinah Samuel (1882) and collected among the poems of his Parisiennes (1887), offers an ideal portrait of the artist facing his own work. Culminating his art at the end of a fulfilled life, the anonymous “artist,” representing his stone-mason’s credo and privilege, carves his own image in granite, destined for the “pinnacle balcony” whence he will contemplate his creation to the end of time, as shows the following prosaic English translation of a French sonnet:

The artist, also a man of virtue,

once he had completed his lofty cathedral,

and made the central rose window sparkle,

and sawed the marble as fine as a chaff,

once he had erected the pointed turret,

and turned the staircase into a narrow spiral,

when all was filled with sepulchral majesty,

and every choir wall was clad in gold,

took his cold chisel, and ere the last knell,

in a block of granite, he hewed himself,

that he might be seated on the pinnacle balcony,

and, as he neared his last hour,

he placed the statue so that he would behold,

his masterpiece of stone for all eternity. 37

L’artiste, en même temps un homme de vertu,

lorsqu’il eut achevé sa haute cathédrale,

qu’il eut fait resplendir la rosace centrale,

qu’il eut scié le marbre aussi fin qu’un fétu,

lorsqu’il eut fait surgir le clocheton pointu,

et tourner l’escalier en étroite spirale,

lorsque tout fut empli de grandeur sépulcrale,

que chaque mur du chœur fut en or revêtu,

prit son ciseau froid, puis, avant le glas suprême,

dans un bloc de granit, il se tailla lui-même,

pour qu’au balcon du faîte on le pût accouder,

et, comme il approchait de son heure dernière,

il plaça la statue, afin de regarder,

pendant l’éternité, son chef-d’œuvre de pierre.

When first published in Dinah Samuel, Champsaur associates this sonnet with “Erwin von Steinbach’s likely effigy” at the foot of the octagonal tower of Strasbourg Cathedral’s spire.38 He thus draws on the history of the cathedral (Erwin von Steinbach had presented its plans to Conrad, Bishop of Lichtenberg, as Champsaur recalls) and a monument on which such “signatures” are notable and multiple.39

Champsaur’s idea is part of a distinctly mythical, historical, and cultural context at the end of the nineteenth century. During Eugène Viollet-le-Duc’s monumental restoration of Notre-Dame in Paris, a statue destroyed in 1792 had been newly erected at the foot of the spire among the apostles. A well-known “signature,” it was the portrayal of Viollet-le-Duc himself by French sculptor and goldsmith Victor Geoffroy-Dechaume.40 While the other apostles contemplate the city, Viollet, in the guise of Thomas, is turned towards the spire, the only one to consider the cathedral itself, and particularly the spire, his magnum opus, using his hand as a shade. Now Thomas the Apostle may well be the patron saint of architects,41 with whom Viollet wished no doubt to identify, but was also the disbelieving and sceptical disciple. Intended to highlight the character’s awe in front of the edifice, does the gesture signal only admiration? Could it indicate disbelief, or simply a wish to see more clearly? In Thomas’s story, Doubt had penetrated the Revelation. Likewise, Jules Michelet ironically commented on the earthing wire of the lightning rod fastened to Strasbourg Cathedral’s spire: it roots down in the tomb of the Steinbach family!42 Artistic signatures already beset the cathedral with warped intentions in the nineteenth century.

Champsaur’s sonnet itself, based on antithesis and oxymoron, is included in his section “La Petite Légende des siècles,” (“The Little Legend of the Ages,” my emphasis) by reference to Victor Hugo’s foremost collection La Légende des siècles (1859–83), keen to depict humanity’s history across time. Champsaur suggests that neither Hugo’s famous Notre-Dame de Paris novel, nor his extensive poems, may be henceforth achieved except in a sonnet (etymologically “little song”), decidedly in miniature. Compared to La Légende des siècles, Champsaur’s “Signature” stands indeed for the counterpart of Hugo’s “The Seven Wonders of the World,” wherein the monuments speak. Already in Hugo’s work, this section leads to a poem entitled “The Epic of the Worm,” announcing the end of all civilisation.

On his side, Jules Vallès had already given the theme unexpected treatment back in 1866, having seen one of the best-known artists of the time as a funambulist and acrobat rehearsing on the cathedral itself. On leaving Gustave Doré’s studio, his imagination was not stirred by the artist’s “powerful fecundity” (Doré had by then already illustrated the epic, comic, and tragic masterpieces that had made him famous) but his athletic performance: “He engaged in an arm-wrestling contest [un bras de fer] up there on the Notre-Dame towers.”43 While placing the artist at the spot assigned by Champsaur, Vallès turns him into a showman whose irreverent juggling act is performed under the Creator’s nose: “Gustave Doré, for his part, had let go of his feet, gripped by the hands, and slowly rising to himself, had tightened his body like a sword, and perhaps even cut a caper [battu un entrechat] under God’s eye and shaken the dust from his shoes onto the believers’ heads.”44

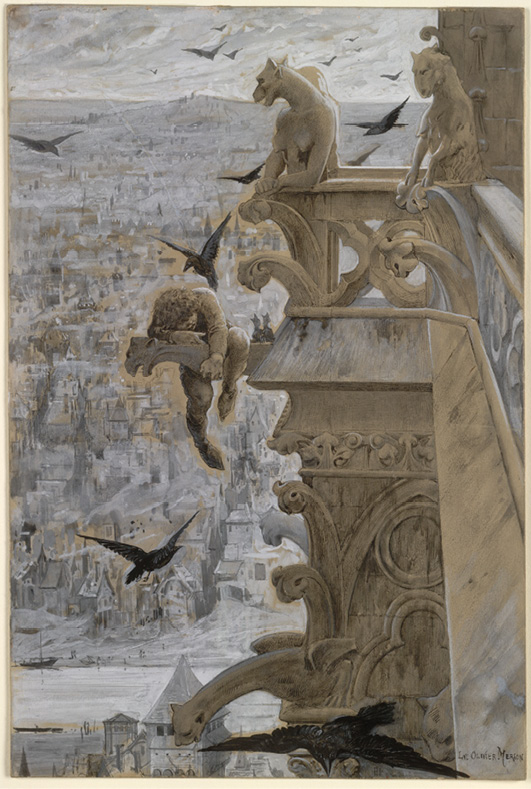

Fig. 3.8 Luc-Olivier Merson, Notre-Dame de Paris (ca. 1881), The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Oh., USA. The CMA Open Access Initiative, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/2008.359

Now, such an account can only recall a monstrous character in the literal sense, one who, crouching among the misshapen statues, is the soul, demon, and spirit of the Notre-Dame Cathedral he haunts. Doré, seen by Vallès, is akin to Quasimodo as interpreted by a host of painters and artists at the time, including Luc-Olivier Merson (Fig. 3.8), the great illustrator of Hugo’s novel.45 Merson was inspired by “a strange dwarf atop one of the towers who climbed, snaked, crawled, on all fours, stepped down over the abyss, jumped from ledge to ledge, and went to burrow into the belly of some carved gorgon,” “a sort of living chimaera,” “a ghastly shape wandering on the frail, lacy balustrade that crowns the towers and borders the apse.”46 Similar to the artist-juggler (Doré by Vallès), this monstrous Quasimodo and his kind could appropriate the place devoted by Champsaur to the anonymous and pious sculptor. Indeed, the fin-de-siècle cathedral, a massive work of art, stands for a “hybrid monster and den of monsters” in Decadent imagination.47 For philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch, it sums up “the allegiance both to the colossus and the trinket.”48 The antithesis that governs it breaks it up into a mass of grotesques that forever perpetuate its fragmented image. All-powerful, the margin takes the monument by storm. Indeed, the best-known visions of Notre-Dame in fin-de-siècle iconography neglect its general view in favour of monstrous details, gargoyles or demons. In his richly illustrated novel Lulu (1901), Champsaur transforms them into the cursed deities of end-of-the-century Paris: the second book of the novel opens with the chapter “Les Gargouilles” (“The Gargoyles”) and closes with “Chœur de gargouilles” (“Gargoyles’ Choir”). The monsters’ dialogue and in-text images frame the text.49

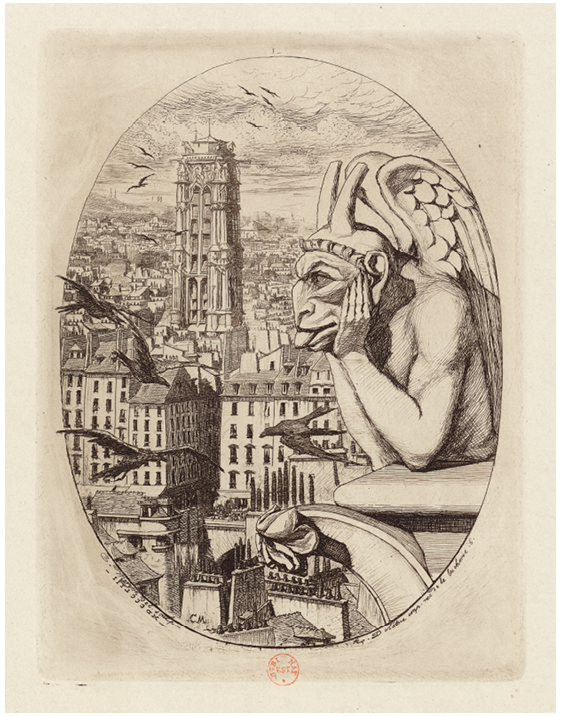

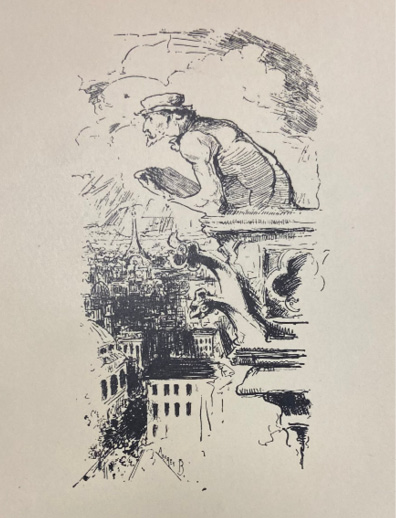

The etching known as Le Stryge, one of Charles Meryon’s Eaux-fortes sur Paris (1853), was instrumental in establishing such imagery (Fig. 3.9). It was reproduced in the most popular illustrated editions of Hugo’s novel and was frequently pirated by woodcuts and vignettes in, for instance, the two volumes of the “new illustrated edition” of Notre-Dame de Paris published by Eugène Hugues in 1876–77. In this, Le Stryge and La Galerie Notre-Dame, engraved by Méaulle after Meryon, form an appropriate setting for Quasimodo to appear.50 Yet Beardsley is not far off either.

Fig. 3.9 Charles Meryon, Le Stryge, engraving, 5th state, in portfolio Eaux-fortes sur Paris, 1853, pl. 6, numbered 1. © BnF, Estampes, Paris

In the Margin of the Book of Stone

Beardsley himself tracked such posturing thanks to photography, that deceptively realistic art. Two of his photographic portraits spiritedly mould themselves on such icons. The first (Fig. 3.10) is openly modelled on Meryon’s Le Stryge, the second (Fig. 3.11a) was named The Gargoyle.

Fig. 3.10 Frederick H. Evans, framed photograph of Aubrey Beardsley as Le Stryge (1894), platinum print, signed, titled and dated by Evans. © GrandPalais-RMN (Musée d’Orsay) / Christian Jean

As early as summer 1894, Beardsley had dressed impeccably for the expert lens of his friend Frederick Henry Evans. Famous for his platinum prints of English and French cathedrals, Evans used a unique chromatic and luminous gradation. As anecdote has it, he teased Beardsley for looking like a gargoyle and challenged him to pose as the demon famously depicted by Meryon: “He [Beardsley] said he was sure he could and immediately put his hands up to his face. I only had to draw back his cuffs so as not to hide any of his marvelous hands and wrists, and then draw his chin a bit forward for its shadow and contour to be obvious and voila, there you are! The often-pirated success!”51

It is worth stressing that Evans usually spent a long time (up to two weeks) capturing the soul of a monument. He practised an “untouched realism” that refused smoothing adjustments. He often photographed partial views and details of these monuments and his vast oeuvre was regularly exhibited from 1890.52 Beardsley as Le Stryge and The Gargoyle photograph (Fig. 3.11a) were both meant to be seen as cathedral fragments, chimaeras used to advertise the artist’s eccentricity. Particularly pleased with the result, Beardsley wanted them “on cabinet boards.”53 He also meant to exhibit them: the one after Le Stryge was shown at the Salon Exhibition in October 1894 and was subsequently used as a frontispiece to The Later Work of Aubrey Beardsley (1901). The other appeared in the periodical press with the caption The Gargoyle as the conclusive photograph of an article with three pieces of Beardsley’s work (Fig. 3.11b). It served as a signature piece to the whole.54

|

|

|

|

Fig. 3.11a–d Frederick H. Evans, photograph of Aubrey Beardsley as The Gargoyle in comparison. 3.11a Beardsley photograph (1894), platinum print, © GrandPalais–RMN (Musée d’Orsay) / Christian Jean; 3.11b The photograph captioned The Gargoyle, repr. The Book Buyer, n.s. 12:1 (Feb 1895): 29. University of Minnesota Libraries; 3.11c Grotesque Head, in Jean-Martin Charcot and Paul Richer, Les difformes et les malades dans l’art (1889), 9 (detail). BnF, Gallica; 3.11d Meryon’s Le Stryge, repr. in Charcot and Richer, 7 (detail). BnF, Gallica

The Gargoyle photograph brings out in profile Beardsley’s beak-like nose, chin with lump, tapering ear, upturned gaze. Drooped, the sweeping fringe drapes the forehead. The gargoyle looks up, ready to spew out the waters of heaven. The chin’s round lump further underlines unevenness. In 1889, the doctors Jean-Martin Charcot and Paul Richer had published an illustrated treatise entitled Les difformes et les malades dans l’art (The Deformed and Sick in Art). In this, the terracotta head no. 769 from the Myrina excavations which had entered the Louvre collections (Fig. 3.11c), reproduced in the opening pages, shows a close resemblance to Beardsley’s profile but for the hermetically shut mouth and the refined features. The artist’s peculiar physique and his illness were styled as artworks modelled on past examples. In the same volume, the terracotta head was duly preceded by a reproduction of the Notre-Dame stryge (Fig. 3.11d).55 A matching subtlety is to be read in Evans’s strygian portrait of Beardsley (see Fig. 3.10). Meryon’s stone monster, sticking out its tongue at the city (see Fig. 3.9), is swapped for a face resting between drawn-out, beautiful, manicured hands, wearing a haughty air, distant gaze, and perhaps condescending pout.

Both photographs operate yet another aesthetic reversal. Panoramic and topographic views of cathedrals were frequent in the nineteenth century. Beardsley’s portraits invert the paradigm. They offer a detailed, individualised and monstrous view of the artist instead. By superseding the gothic sanctuary, they erect a new definition of the self as an unruly detail that obliterates the whole. Detached from the cathedral’s medieval cultural background, the artist is a monster in his very flesh, a good twenty years before body art emerged as such. Upon visiting Westminster Abbey with his mother, the stained-glass window had been an option for little Aubrey, we remember, but he had preferred the bust. His pictorial effigies now force themselves onto the disintegrated building. Modernity cast the artist himself into a new plastic paradigm. Effigies in paper and platinum prints had replaced stone. Evans’s two shots frame the introduction to The Early Work of Aubrey Beardsley (1899, posthumous), propelling the artist himself as the anomalous preamble to his work. John Lane, Beardsley’s crafty publisher, knew what he was doing.

Beardsley’s enduring interest in such marginal and atypical art had already devised yet another ironic aesthetic credo. A drawing published in the Pall Mall Budget on 4 January 1894 pictured the American illustrator and art critic Joseph Pennell, the first to promote him in the April 1893 Studio, with the title Mr Pennell as “The Devil of Notre Dame.” (Fig. 3.12a).

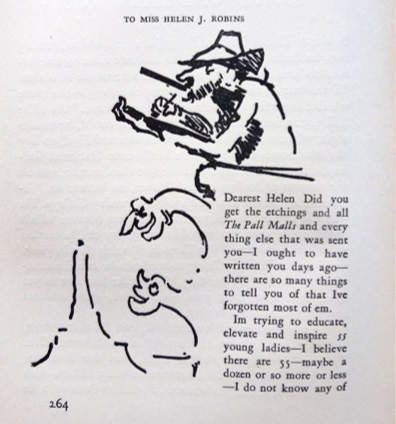

Fig. 3.12a–b Aubrey Beardsley sketching Joseph Pennell as Meryon’s Stryge. 3.12a Beardsley, Mr Pennell as “The Devil of Notre Dame,” The Pall Mall Budget (4 Jan 1894): 8, repr. from Early Work, pl. 155. Courtesy MSL coll., Delaware; 3.12b Pennell, humorous sketch of himself after Beardsley, repr. in Elizabeth Robins Pennell, The Life and Letters of Joseph Pennell (1929), I, 264. Author’s photograph

In the catalogue raisonné this drawing has been retitled A New Year’s Dream, after Studying Mr Pennell’s “Devils of Notre Dame” and dated May 1893 (Zatlin 312). In the Pall Mall Budget, the Beardsley reproduction closely followed publication of Pennell’s own gargoyles of Notre-Dame issued in two instalments in this very magazine’s Christmas issue where they profusely illustrated a text by Robert A. M. Stevenson.56 Beardsley’s drawing originates from the artist’s second stay in Paris with the Pennells, and Joseph preparing a series of etchings on the cathedral demons.57 Beardsley (as Evans himself) had climbed the towers more than once to meet Pennell who had spent part of the summer and autumn 1893 in the so-called Notre-Dame gallery, often receiving his friends there as guests. In a 24 December 1893 letter to his sister-in-law Helen J. Robins, Pennell had even jokingly depicted himself as Meryon’s Stryge after Beardsley’s drawing (Fig. 3.12b). He reproduced Beardsley’s artwork opposite his own etched interpretation of Le Stryge in his memoirs and even declared: “Beardsley, who was with me in Paris in 1893, climbed up too [in the Notre-Dame tower], and made me into a chimera.”58 In his good-humoured version, Pennell depicts himself nonchalantly smoking a giant cigar and sketching the city from the cathedral’s very tower.59 As his wife put it in his biography, published with numerous letters and sketches, “Viollet-le-Duc oppressed him” and “His happiest hours were on the roof among the devils and monsters.”60 However, Beardsley represented his patron bending over the city as a gargoyle and artist in one: his clawed paw gripped a portable sketch board, and his gaze eagerly scanned the city for a view worthy of depiction. Beardsley’s drawing is no humorous caricature. He provides Pennell with petrified fingers and a frozen body, which may ironically exhibit his conventional realistic aesthetic and attachment to life drawing. Only his face, painter’s bonnet, and flopping necktie belong to the modern world. And yet, instead of the medieval city that Luc-Oliver Merson reconstructs (see Fig. 3.8) or the Middle Ages recalled by Meryon’s inclusion of the St. Jacques tower in his Stryge (see Fig. 3.9), Beardsley pictures the nascent Eiffel Tower in the background, a detail that Pennell’s jesting sketch takes on. The modern city of sky-high memorials (and photographic portraits) breathes beneath this conservative depiction of Pennell. Modernity invites again the artist to formulate new aesthetic rules. Beardsley grants an animated life to the stone ornaments below Pennell: one of them opens up like a flower, the other has acquired an eye avidly looking at the city. Pennell again follows light-heartedly, his own ornament jokingly conversing with one of its fellows. By contrast to Pennell’s self-parody, Beardsley’s mordant humour pictures Pennell as half-fossilised, a rigidified remnant of the past.

Body Art

Evans’s photographic portraits are much more than portraits. Champsaur imagined the artist as a meticulous sculptor and the supreme master of the vast monument he had created. Vallès saw Doré, his 1866 contemporary, as an athlete and clown, defying God himself on Notre-Dame. Some thirty years later, for Evans and Beardsley the artist identifies not with the main body of the cathedral, but with a monstrous detail of the disintegrating whole. Both of Evans’s platinum prints relate also to Beardsley’s deviant self-portraits, Portrait of Himself and A Footnote. These images offer striking proof of Beardsley’s deliberate monstrosity, displaying his physical appearance as deformed, without artifice or artistry, as a substitute for the long-desired bust. Evans’s photographs ultimately record Beardsley’s very form as an early manifestation of body art. The systematic use of the body in artistic performances dates from the 1960s–70s. Among its forerunners, it is customary to mention the pioneering works of Frank Wedekind, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, and Oskar Kokoschka (1909), Egon Schiele (1910), David Burliuk and Vladimir Mayakovsky (1914), or Marcel Duchamp (Tonsure, 1920, and Belle Haleine, eau de voilette, 1921), all of which post-date Beardsley by at least fifteen years.61

Nonetheless, art had already broken out of the picture frame and infused life itself at the end of the nineteenth century. Only three years before Evans took his photographs of Beardsley, the satirical writer Alphonse Allais was describing similarly conceptual forms of art. In his short story “Le Bon Peintre” (“The Good Painter”), Allais describes an artist putting postage stamps on an envelope, “taking great care that the tones were well arranged – so that it wouldn’t look too gaudy.” He even pastes a last superfluous stamp at the very bottom “to have a touch of blue.”62 Not only does he treat postage stamps like palette colours to paint with, but also the food he consumes: “For nothing in the world […] would [the same painter] drink red wine while eating fried eggs, because it would have made him an ugly tone in the stomach.”63 Like Beardsley, Allais’s painter treats his own body as a work of art in a way that is likely intended as an amusing dig at the art world.

Beardsley’s humour opened the way to innovation. It was a form that allowed for the critical freedom of the imagination. In these far-reaching fin-de-siècle experiments, creation turned to life itself with the artist in person as support and expression. Beardsley’s grotesque self-portraits wittily exploited all the possibilities opened up by humour and margin. Between dominant culture and protest, humour drives a rift. It speaks a language that assails hierarchy and order. The margin, packed with rejected elements surging at the periphery, de-centred as eccentric, ends by invading text, whether script or stone incision, to invert their relationship. By exploring such breaches as so many salutary cracks in the hermetic house of norms, humour and margin save culture from the presumption, smugness, and pride it is bound to bear within it. Robert Ross had acutely discerned the inversion when he wrote on Beardsley: “True grotesque is not the art either of primitives or decadents, but that of skilled and accomplished workmen who have reached the zenith of a peculiar convention.”64

1 Brigid Brophy, Beardsley and his World (London: Thames and Hudson, 1976), 5.

2 Regarding outline, Crane abundantly praised Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, attributed to Francesco Colonna and printed by Aldus Manutius in Venice (1499), as with designs “in outline, and want[ing] nothing else.” He also stressed the charm, simplicity, and “broad effect” of outline in modern publications. See Walter Crane, Of the Decorative Illustration of Books Old and New (London: George Bell and Sons, 1896), 62–71 and 223.

3 This drawing serves as frontispiece in Brigid Brophy, Beardsley and his World. It also faces the “Introduction” in Matthew Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley: A Biography (London: Harper Collins Publishers, 1998).

4 Walter Sickert, “Portrait of Aubrey Beardsley,” The Yellow Book, 2 (July 1894): 223, in The Yellow Book Digital Edition, ed. by Dennis Denisoff and Lorraine Janzen Kooistra, 2011–14. Yellow Nineties 2.0, Ryerson University Centre for Digital Humanities, 2020, https://1890s.ca/YB2-sickert-aubrey-beardsley/; Brophy, Beardsley and his World, 57.

5 Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary: mœurs de province, édition définitive suivie des requisitoire, plaidoirie et jugement intenté à l’auteur (Paris: G. Charpentier, 1877), 321: “Le plus médiocre libertin a rêvé des sultanes; chaque notaire porte en soi les débris d’un poète.” (2nd Part, Chapter VI).

6 Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley, 160.

7 Beardsley and Beerbohm were both born in August 1872, Beardsley being the elder by three days.

8 Brophy, Beardsley and his World, 49.

9 Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley, 136–37, 202.

10 Charles Baudelaire, “Le peintre de la vie moderne,” Le Figaro (26 and 29 Nov, 3 Dec 1863); collected in L’Art romantique (1868); Œuvres complètes, ed. by Claude Pichois, 2 vols. (Paris: Gallimard, 1976), II, 683–724.

11 Baudelaire, “Le peintre de la vie moderne,” 711: “Le dandysme est le dernier éclat de l’héroïsme dans les décadences.”

12 Ibid., 710: “Ces choses ne sont pour le parfait dandy qu’un symbole de la supériorité aristocratique de son esprit.” “C’est le plaisir d’étonner et la satisfaction orgueilleuse de ne jamais être étonné.” On Beardsley and Baudelaire, see also Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley, 96–97.

13 Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley, 192.

14 Jurgis Baltrušaitis, “Le réveil du fantastique dans le décor du livre,” in Baltrušaitis, Réveils et Prodiges: le gothique fantastique (Paris: A. Colin, 1960), 195–234.

15 See Hans Christoph von Tavel, Die Randzeichnungen Albrecht Dürers zum Gebetbuch Kaiser Maximilians (Munich: Prestel Verlag, 1966).

16 See Richard Benz, Goethe und die romantische Kunst (Munich: R. Piper & Co., 1940), 146–55; Arthur Rümann, Das illustrierte Buch des XIX. Jahrhunderts in England, Frankreich und Deutschland, 1790–1860 (Leipzig: Im Insel-Verlag, 1930), 294. And more recently, Cordula Grewe, The Arabesque from Kant to Comics (New York: Routledge, 2021).

17 André Chastel, La Grottesque. Essai sur l’“ornement sans nom” (Paris: Le Promeneur, 1988), 9. See also Philippe Morel, Les Grotesques: Les Figures de l’imaginaire dans la peinture italienne de la fin de la Renaissance (Paris: Flammarion, 2001).

18 Chastel, La Grottesque, 42: “Nous sommes au sens propre dans le marginal, et le marginal est toujours et partout le domaine de la permissivité.”

19 Joris-Karl Huysmans, “Le Monstre,” in Huysmans, Certains (Paris: Tresse et Stock, 1889), 142.

20 See Jean de Palacio, “La cathédrale hystérique: monstre hybride et repaire de monstres,” in La Cathédrale, ed. by Joëlle Prungnaud (Lille: UL3, Travaux et Recherches, 2001), 142–43.

21 “An Apostle of the Grotesque,” The Sketch, 9:115 (10 Apr 1895): 561–62.

22 Arthur H. Lawrence, “Mr. Aubrey Beardsley and His Work,” The Idler, 11 (Mar 1897): 198.

23 The Yellow Book, 3 (Oct 1894): 51.

24 “An Apostle of the Grotesque,” 561.

25 The Savoy, 2 (Apr 1896): 185.

26 Dante Gabriel Rossetti, “Lilith (For a Picture),” in Poems (London: F. S. Ellis, 1870), republished as “Body’s Beauty” within the section “The House of Life,” in Ballads and Sonnets (London: Ellis and White, 1881).

27 Later entitled “Soul’s Beauty,” this sonnet precedes “Lilith” in both collections.

28 Rossetti, “Sibylla Palmifera,” v. 1–10.

29 [Owen Seaman], “Lilith Libifera (After Rossetti),” Punch, or The London Charivari, 107 (3 Nov 1894): 205; later collected in The Battle of the Bays (London and New York: John Lane, 1896), 57 (with variants).

30 See Victor Arwas, Alastair: Illustrator of Decadence (London: Thames and Hudson, 1979); Ines Janet Engelmann, ed., Alastair. Kunst als Schicksal (Halle: Stiftung Moritzburg Halle, Kunstmuseum des Landes Sachsen-Anhalt, 2004); Engelmann, ed., Alastair. Kunst als Schicksal (Munich: Bayerische Akademie der Schönen Künste, 2007).

31 Arwas, Alastair: Illustrator of Decadence, 86, no. 71.

32 See https://archive.org/details/TheSphinxDecoratedByAlastaiOscarWilde/mode/2up

33 Oscar Wilde, Das Bildnis des Dorian Gray, Roman aus dem Englischen übertragen von Alastair (Konstanz: Lingua Verlag, 1948). No images.

34 On Wilde’s novel and its complexity, see for instance Catherine Rancy, Fantastique et Décadence en Angleterre, 1890–1914 (Paris: Éditions du CNRS, 1982), 25–47.

35 Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1949), repr. 1981, 245, 247, 245.

36 There is a series of Catherine de Medici’s beds in the Loire Valley castles; the bed she is said to have died on is in the Chateau of Blois.

37 Félicien Champsaur, “Signature,” Parisiennes (Paris: A. Lemerre, 1887), 93.

38 Champsaur, Dinah Samuel, ed. by Jean de Palacio (Paris: Séguier, 1999), 413.

39 The statue of architect Ulrich von Ensingen gazing up at the spire may be seen in the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame in Strasbourg. In the south transept, another architect leaning on the railing, marvelling at the Last Judgement pillar, probably represents Hans Hammer (1486). See Robert Walter, Histoire anecdotique de la cathédrale de Strasbourg (Strasbourg: Erce, 1992).

40 With thanks to Joëlle Prungnaud for this suggestion.

41 Thierry Crépin-Leblond, La Cathédrale Notre-Dame (Paris: Éditions du Patrimoine, 2000), 46–47, with a photograph by Étienne Revault.

42 Qtd. by Roland Recht, La Cathédrale de Strasbourg (Strasbourg: La Nuée bleue, 1993), 17.

43 Jules Vallès, “Les Exercices du corps,” L’Événement (5 Feb 1866): 3c: “— Il a fait le bras de fer là haut sur les tours de Notre-Dame,” his emphasis.

44 Ibid.: “Gustave Doré, lui, avait lâché les pieds, s’était accroché par les mains, et se relevant lentement, il avait tendu son corps comme une épée, et même peut-être, il avait battu un entrechat sous l’œil de Dieu et secoué sur la tête des croyants la poussière de ses souliers.”

45 Merson illustrated the two-volume deluxe edition of Hugo’s novel for the publisher A. Ferroud in 1889–90 following the composition reproduced here. A chapter heading repeats this motif with a modified perspective in Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, illustrations de Luc-Olivier Merson, 2 vols. (Paris: A. Ferroud, 1889–90), I, 227. The work reproduced here was published in Alfred Barbou, Victor Hugo et son temps (1881), a volume frequently republished. It introduces the chapter devoted to Notre-Dame de Paris. I thank Mrs Danielle Molinari, former general curator of the House of Victor Hugo and Hauteville House, for her help tracing this image’s career.

46 Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris [1831] (Paris: Garnier-Flammarion, 1967), Bk. IV, Chapter III, 177, my translation and emphasis: “un nain bizarre qui grimpait, serpentait, rampait, à quatre pattes, descendait en dehors sur l’abîme, sautelait de saillie en saillie, et allait fouiller dans le ventre de quelque gorgone sculptée,” “une sorte de chimère vivante,” “on voyait errer une forme hideuse sur la frêle balustrade découpée en dentelle qui couronne les tours et borde le pourtour de l’abside.”

47 Such is the subtitle of Jean de Palacio’s article, “La Cathédrale hystérique: monstre hybride et repaire de monstres.”

48 Vladimir Jankélévitch, “La Décadence,” Revue de métaphysique et de morale, 4 (1950): 337–69 (345): “à la fois la tendance au colosse et la tendance au bibelot.”

49 Champsaur, Lulu, roman clownesque (Paris: Eugène Fasquelle, 1901), 41–50 and 249–52.

50 Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris : 1482 (Paris: Eugène Hugues, 1876–77), 148–49. See online https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9941148/f168.item and

https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k9941148/f169.item51 Qtd. from ms. Wilde E92LM466 in William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California, Los Angeles, by Linda Gertner Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley: A Catalogue Raisonné, 2 vols. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2016), I, 200.

52 See Beaumont Newhall, Frederick H. Evans: Photographer of the Majesty, Light and Space of the Medieval Cathedrals of England and France (New York: Aperture, 1973); and Anne M. Lyden, The Photographs of Frederick H. Evans, with an Essay by Hope Kingsley (Los Angeles, Calif.: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010).

53 The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, ed. by Henry Maas, J. L. Duncan, and W. G. Good (London: Cassell, 1970), 73: “Dear Evans, I think the photos are splendid; couldn’t be better. I am looking forward to getting my copies. I should like them on cabinet boards if that’s not too much trouble.”

54 See Herbert Small, “Book Illustrators: X. Aubrey Beardsley,” The Book Buyer, n.s., 12:1 (Feb 1895): 26–29.

55 Jean-Martin Charcot and Paul Richer, Les difformes et les malades dans l’art (Paris: Lecrosnier et Babé, 1889), 7 and 9.

56 See “The Devils of Notre-Dame, by Mr Joseph Pennell with a Comment by R. A. M. Stevenson,” The Pall Mall Budget (14 and 21 Dec 1893). Also separately published in 1894 as a deluxe elephant folio folder on Japanese paper, limited edition of seventy copies with only fifty for sale. See The Devils of Notre-Dame, A Series of Eighteen Illustrations by J. Pennell, With Descriptive Text by R. A. M. Stevenson (London: Pall Mall Gazette, 1894).

57 Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley, 135.

58 Joseph Pennell, The Adventures of an Illustrator, mostly in Following his Authors in America & Europe (Boston, Mass., Little, Brown and Company, 1925), 204, reproductions ibid., 218–19.

59 See Elizabeth Robins Pennell, The Life and Letters of Joseph Pennell, 2 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co, 1929), I, 264; and Michael Pantazzi, “Du stryge au gratte-ciel,” Livraisons de l’histoire de l’architecture, 20 (2010): 91–112, fig. 17, https://doi.org/10.4000/lha.261

60 Pennell, The Life and Letters of Joseph Pennell, I, 253.

61 See L’Art au corps: Le Corps exposé de Man Ray à nos jours (Marseille: RMN, 1996); and Lea Vergine, Body Art e storie simili (Milan: Skira, 2000).

62 Alphonse Allais, “Le Bon Peintre,” (Œuvres anthumes) À se tordre, histoires chatnoiresques (Paris: Ollendorff, 1891), 139–41; repr. in Œuvres anthumes, ed. by François Caradec (Paris: Robert Laffont, 1989), 50–51: “verticalement, en prenant grand soin que les tons s’arrangeassent – pour que ça ne gueule pas trop”, “pour faire un rappel de bleu.” (Allais’s emphasis).

63 Ibid., 50: “pour rien au monde il ne buvait de vin rouge en mangeant des œufs sur le plat, parce que ça lui aurait fait un sale ton dans l’estomac.”

64 Robert Ross, Aubrey Beardsley with Sixteen Illustrations and a Revised Iconography by Aymer Vallance (London: John Lane, The Bodley Head; New York: The John Lane Company, 1909), 49.