4. Beardsley Images and the “Europe of Reviews”

©2024 Evanghelia Stead, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0413.04

Aubrey Beardsley aroused exceptional critical interest, resulting in an extraordinary number of entries, interviews, and articles in newspapers and periodicals. In 1989, Nicholas Salerno collected and commented on more than 1,500 bibliographical references in Reconsidering Aubrey Beardsley.1 A good part of these were articles written in Beardsley’s lifetime.2 Despite some inaccuracies, Salerno’s list proves that Beardsley enjoyed outstanding critical fortune, which, by virtue of the space and standing it assured him, became a sturdy foundation of his oeuvre. Beardsley’s ascension was reliant not only on his innovative artwork but also on the broadcasting of ideas and controversies. The artist was acutely aware of the press’s power as mentor and tastemaker, and he was able to partly mould the media’s depiction of him. However, as reviews and articles spread, they invested his images with strong mythical value that was beyond his control, making Beardsley a meteor in the European art constellation of the time. His works have the aura of shooting stars: still irradiating the artistic sky long after they have passed. Twenty-seven obituaries appeared on his death in the British press alone. In an early French article of 1897, Henry-D. Davray echoed the phenomenon beyond Britain, from the buzzing heart of Paris: “If, following the example of Mr. Whistler, he were to publish all his newspaper clippings, it would certainly form a most interesting and instructive collection. For he was proclaimed, discussed and vilified beyond words.”3

Beardsley had early on grasped the importance of the media to advancing an artist’s career. Each press article not only assessed his artistic value but, even when censuring or complaining about him, also served to expand his notoriety. He therefore skilfully steered magazines from behind the scenes, and readily put himself forward through intriguing, distancing, and ironic postures. Magazines embodied the very spirit of media modernity. They were numerous, diverse, and each called for differentiated attention, if maximum effect was to be achieved. In promoting avant-garde work in a transitional era with numerous conservative proclivities, Beardsley had to embrace older paradigms, adapting them to his vision in order to gain widespread notoriety. Such was the first major commission he accepted, the illustration of Thomas Malory’s Le Morte Darthur. Although the book was in theory following the model of hand printing and craftsmanship set by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press, its publisher J. M. Dent had tailored it to photomechanical printing and commercial distribution. Industrialised reproduction in magazines was also representative of the spirit of modernity, and these mass-produced formats allowed Beardsley’s images to be seen by an ever-increasing viewership.

This chapter looks at the presentation of Beardsley in the press, and the images associated with these articles – their original significance, and Beardsley’s and others’ repurposing of them within new contexts. I take into consideration the layout of the articles and images, showing that the display and array can speak a language as expressive as the artwork itself. I am also interested in how Beardsley’s representation differed depending on the country and type of periodical he appeared in. His fortunes emerged between distinct categories of cultural magazines: those meant for the general public, those specific to fine and applied arts, and those shaped as select art and literature reviews. The chapter focuses primarily on the Italian Emporium, which gathered its material from across the European press. But first, it looks at the earliest representations of Beardsley in the English journal The Studio, which set a blueprint for the selection of his work and its positive reception.

It then gauges Beardsley’s reception in Italy against a matrix of images and ideas in a variety of international publications, including the British Sketch, the American Art Student, the French Le Livre et l’Image, the German Kunst und Künstler. As we will see, Italian articles partly shape each other while reflecting ideological, artistic, and aesthetic points of view of national specificity. They also reveal a vast network of journals in Europe. However, comparison and the spreading of images do not explain everything: it is also necessary to look at Beardsley’s own plying of the press and his self-modelling. To illustrate the artist’s input to his own representation, I turn primarily to the British Sketch, in which a hoax by Beardsley himself was naively taken on by Emporium. In the next chapter on the French press, we will see how the artist’s image was also appropriated in ways well beyond Beardsley’s control. Indeed, two complementary forces drive image making in the fin de siècle: clever stage-managing of one’s own iconography, and unstoppable dissemination by the media.

What then of critiques, polemics, and facetious taunts? Are we to take all objections to Beardsley as negative reactions? Are they all outright condemnations and ad hominem attacks? As shown in the previous chapter, Edward Tennyson Reed mimicked and parodied Beardsley in Punch under mock pseudonyms, but his spoofs were also vital in making Beardsley known, calling attention to his work, and broadcasting his style. The American Chap-Book contributed to such assortment by mock-hallowing and nicknaming Beardsley, and repurposing his work in overtly commercial ways.

This chapter also considers periodicals in a network that includes small, medium, and larger publications. My reticular approach stresses circulation and exchanges. It puts individual creations in perspective: not only as unique inventions but in a distribution flow and in conversation with others. Such give-and-take is not only intellectual. It depends on marketing, relies on relations, and carries symbolical and emotional weight. A media-driven era is an age in which publications are not merely stable objects per se, but shared practices and processes through which individual artists and communities engage, barter, and trade.

Framing Beardsley in England

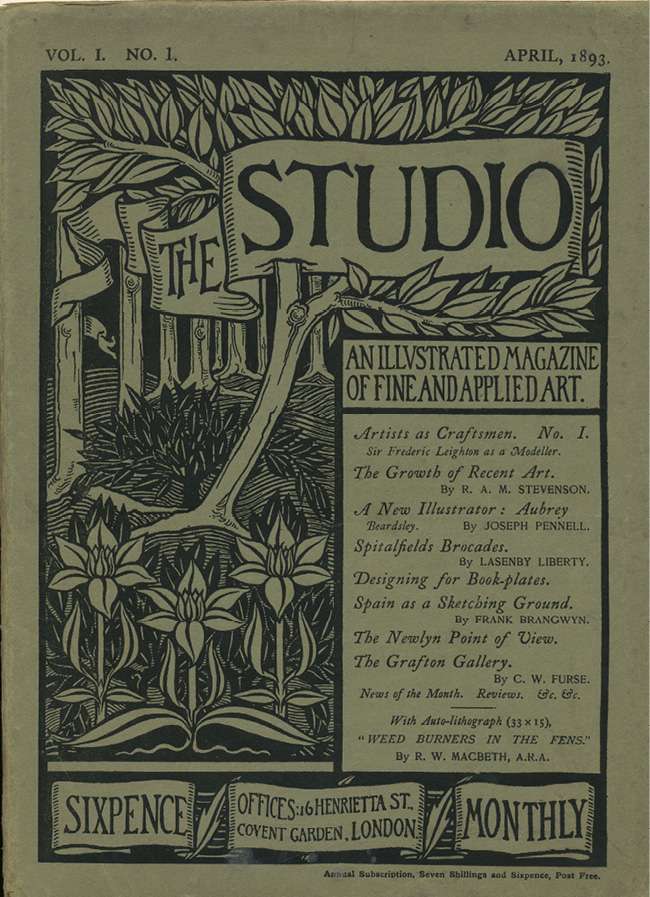

The Studio, an English fine and applied art periodical, which was to become hugely influential and ran until 1964, introduced and established Beardsley: the first article to make him known was the centrepiece of its very first issue in April 1893. That month, the promising but little-known artist, hitherto hardly published, had been commissioned by Dent to illustrate Le Morte Darthur with the first instalment issued in June. The work’s requirements appealed to Joseph Pennell, the American engraver, lithographer, and illustrator. Pennell was an authority on illustration and a promoter of process engraving. By supporting Beardsley through The Studio, he meant to deal a blow to traditional art criticism and hierarchy, which tended to consecrate artists only once they were dead.4 By contrast, his protégé was at the outset of his career and extremely young. Images were a major instrument in such a campaign. Beardsley’s novel iconography was carefully reproduced in this first Studio article, with seven pages of illustrations encompassing the three pages of Pennell’s text. His artwork contrasted with others’ drawings in the same issue, which tended to be realistic and hastily sketched.

The layout of the article added to the surprise effect, a metaphor for the images’ sudden, indeed abrupt, emergence. The first materialised at the end of a piece by R. A. M. Stevenson on “The Growth of Recent Art” (against Decadence). It was a miniature reproduction of Beardsley’s The Procession of Joan of Arc (Zatlin 241) and would lead to a full replica of this exceptionally long pencil drawing, folded and mounted in The Studio’s second issue. Next to it, a full-page display featured Siegfried, Act II (Zatlin 246), an elaborate drawing that thrilled Edward Burne-Jones who owned it. Pennell’s text only started after these two images, and shared the first page with Frank Brangwyn’s “Letters from Artists to Artists: Sketching Grounds.” It either sat next to Beardsley’s designs or was framed by an impressive layout of Le Morte Darthur covering a double page spread. Drawings in the hairline style such as The Birthday of Madame Cigale (Zatlin 266) took up a page, introducing Beardsley’s Japanese manner. Pennell defended “an artist whose work is quite as remarkable in its execution as in its invention.” He also upheld mechanical engraving, the excellence of Beardsley’s pen line, and decoration as specific drawings per individual pages. To crown it all, quality reproductions turned The Studio itself into a technical benchmark of reproductive excellence.

The Studio article was a double debut, in which the periodical and the artist set foundations by helping each other. Beardsley had designed the Studio’s cover (Fig. 4.1, Zatlin 308b) and partly fashioned its graphic identity, drawing from it lessons for the art and literature reviews he would later direct. In turn, the Studio showcased an artist representative of two fields it clearly defined as its own and in contrast to the hierarchies of the art establishment, that is, the fine and applied arts. Their double passport, however, is based on what could be described as safe aesthetic choices. Promoting, close to Burne-Jones and the Pre-Raphaelites, a Beardsley recently engaged by Dent to illustrate a late medieval text on the model of the Kelmscott Press, but without its requirements of craftsmanship and manual labour, the periodical championed a medieval-inspired style and design that was fashionable rather than forward-looking. Indeed, medievalism was more associated with bourgeois complacency than the daring and provocative images that Beardsley was already developing. The disturbing side of his art nevertheless emerges in the Studio article in the last full-page drawing which includes a French quote, “J’ai baisé ta bouche Iokanaan, J’ai baisé ta bouche” (“I have kissed your mouth, Iokanaan, I have kissed your mouth”) (Zatlin 265). The citation is from Oscar Wilde’s original version of Salomé (in French), which had just been published not in England but in France. It presented Beardsley as a connoisseur of daring French literature. The drawing would earn him another prestigious commission (for the English edition of Salome by John Lane, 1894), whose audacity led to a much more controversial reception. Already in this choice, the first Studio article showed how Beardsley’s artistic identity had broken free from the medieval mould in which his first major commission might have ensnared him.

Fig. 4.1 Aubrey Beardsley, Cover Design of the “Studio”, 1:1 (15 Apr 1893) on light green paper with lettering, 2nd state (by 24 Feb 1893). Courtesy MSL coll., Delaware

One has only to compare this remarkable debut with the exit, Beardsley’s obituary in the Studio’s May 1898 issue.5 The article was two months late,6 and Gleeson White, the Studio’s first editor, signed it with his initials only, as if it were unbecoming to fully claim it as his own. Moreover, its iconography was reduced to six drawings, none of which is disturbing or representative of the great books that the artist had decorated. Even worse, the last three pages yielded to a visual language altogether foreign to Beardsley, i.e., watercolours of Morocco by Walter Tyndale and numerous reproductions of medals. Given the context, such irrelevant iconography is a form of disrespect, if not grossness.

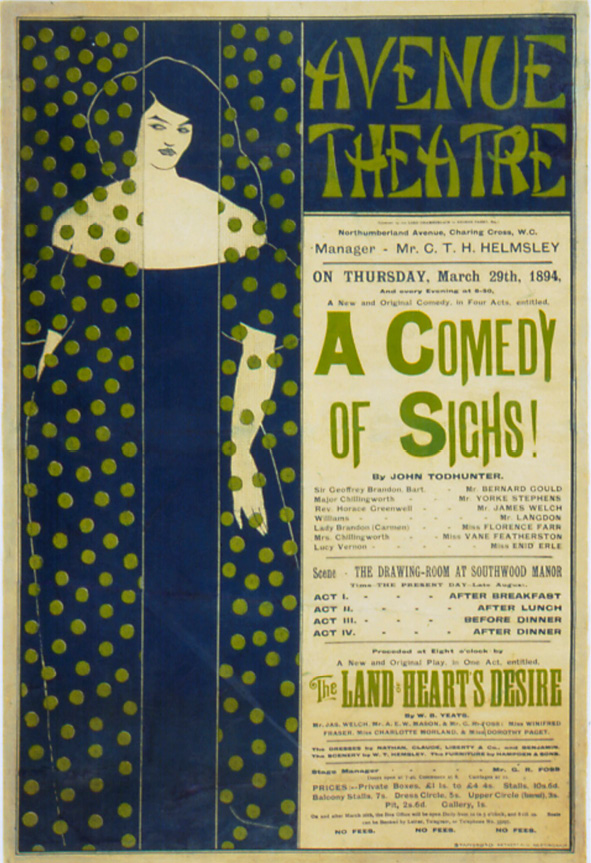

White was in no position to deny Beardsley the label of genius nor ignore his tremendous influence, but his personal reservations and doubts show in nearly every sentence: he referred to Beardsley’s off-putting subject matter; his departure from drawing after life; his lack of schooling; and the fact that his art was offensive and inaccessible to the man in the street. While tracing the history of Beardsley’s oeuvre, White focused on Beardsley’s poster for John Todhunter’s A Comedy of Sighs! and The Land of Heart’s Desire by William Butler Yeats, catalogued as Poster Design for the Avenue Theatre (Zatlin 967), a work that was as revolutionary in its colouring, layout, and format as it was scandalising to passers-by (Fig. 4.2). Its central figure, in Margaret D. Stetz’s words, “was clearly no lady – uncorseted, with loose hair, and with her clothes slipping off her shoulders.”7 White states that it made Beardsley “well known not only in the artistic society of both continents, but in a less[er] degree to the general public also” and recalls its parody after Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s “The Blessed Damozel,” the well-known Pre-Raphaelite poem, to ridicule the poster.8 Rossetti’s poem was modelled on the Beatrice of Dante’s Vita Nova and celebrated a lost love. The parody desecrated it with trivial expressions and insisted on the drawing’s so-called imperfections.9 As far as obituaries go, the choice could hardly be more ambiguous.

Fig. 4.2 Aubrey Beardsley, Poster Design for the Avenue Theatre, theatre poster for A Comedy of Sighs! by John Todhunter and The Land of Heart’s Desire by William Butler Yeats (Jan–Feb 1894), colour lithograph. Courtesy MSL coll., Delaware

Despite such a belittling farewell, the fact remains that the first Studio article established Beardsley in Europe with lasting effect: all articles presenting him for the first time referred to the Studio, from the Catalan Joventut10 and the Russian Mir iskusstva,11 to the German Pan12 and, as shown in the next section, the Italian Emporium. In France, John Grand-Carteret’s Le Livre et l’Image, a monthly journal focusing on bibliophilia and art which regularly presented new books and periodicals of note, echoed the Studio from August 1893. On three occasions, an anonymous contributor signing as “Un Book-Trotter” took over the first (disturbing) version of the Studio cover, finally used as prospectus (Zatlin 308a).13 He further commented on Beardsley’s style and reproduced Merlin Taketh the Child Arthur into His Keeping, a double-page drawing from Le Morte Darthur (Zatlin 344) previously featured in the English magazine, as a one-page design.14 Like a seismograph, however, the French magazine lastly reflected the fluctuating fortunes of the artist: the third of these mentions welcomed the biting remarks of E[rnest] Knaufft, a former industrial art professor at Purdue University, art critic, art educator, and director of the Chautauqua Society for Fine Arts, on the “forty-three upturned noses” of The Procession of Joan of Arc, again from the Studio, judged too Pre-Raphaelite by the American commentator in his own New York magazine The Art Student.15 Le Livre et l’Image retransmitted this humorous opinion, although in March 1894, barely a year after the Studio, Grand-Carteret similarly opened his study on the illustrated book in three countries with Beardsley’s decorative header for the title page of Le Morte Darthur catalogued as Battling Knights (Zatlin 511), and Beardsley himself only mentioned in passing.16 It is in this context, highly laudatory, but also at times reserved or circumspect, that one may situate and gauge how he appeared in Emporium.

Emporium and the “Europe of Reviews”

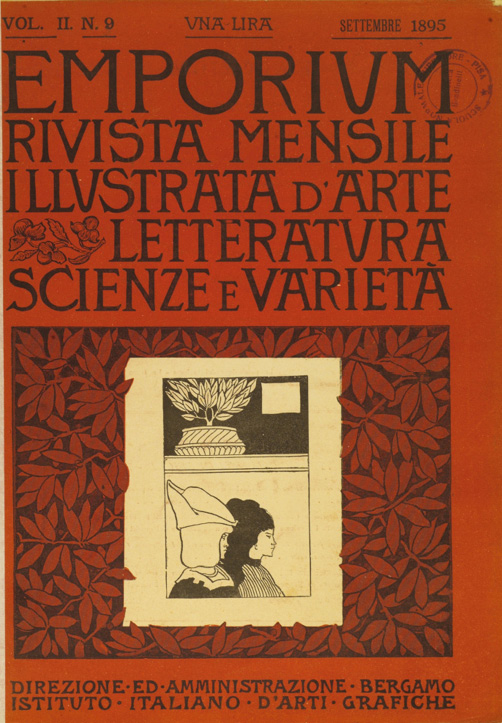

Beardsley’s presence in Emporium, a long-running Italian art magazine aimed at an educated readership (1895–1964), offers a unique opportunity to consider the construction of the artist’s European fame. The editors, Paolo Gaffuri and Arcangelo Ghisleri, borrowed from English and American magazines and aimed at bringing the newest art, science, literature, and music to their readers. They sourced material for their magazine from across the European press via subscriptions, evidenced in preserved resources from the Istituto Italiano d’Arti Grafiche now at the Biblioteca Civica Angelo Mai in Bergamo.17 Emporium’s three articles on Beardsley thus allow us to see the artist’s image in the comparative context of a “Europe of reviews,” as in two co-edited collections on European periodicals.18

Emporium’s three articles date from September 1895, May 1898, and May 1904. The first, signed with the initials G. B., whose identity I have been unable to trace, is the very first on Beardsley in Italy. The second, unsigned, refers to the first, and must have originated from the same pen: it is an obituary, published two months after the artist’s death on 15 March 1898. The last posthumous article, by Vittorio Pica, a leading figure in Emporium and advocate of numerous foreign avant-garde artists in Italy,19 reflects on Beardsley as well as on James Ensor and Edvard Munch, and was later included in Pica’s well-known series Attraverso gli albi e le cartelle.20

Fig. 4.3 Emporium, 2:9 (Sept 1895), cover of the issue with the first article on Beardsley showing a decorative vignette from Le Morte Darthur in foliage tributary of the Studio cover (see Fig. 4.1). Courtesy DocStAr, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, Pisa. The vignette is Man and Woman Facing Right (Zatlin 528), from Bk. IX, chapter xvi

The first Emporium article owed much to the Studio.21 It offered a similar layout, recycled several of the same images, and its cover – a vignette from Le Morte Darthur set within foliage – was strongly reminiscent of the Studio’s cover (Fig. 4.3, to compare with Fig. 4.1). The article opened impressively with a full-page reproduction of The Lady of the Lake Telleth Arthur of the Sword Excalibur (Zatlin 366),22 and, like The Studio, reproduced Beardsley’s Les Revenants de Musique, The Procession of Joan of Arc, the double-page drawing on Merlin from Le Morte Darthur reduced to a one-page layout as in Le Livre et l’Image, the Siegfried plate, J’ai baisé ta bouche Iokanaan, the two renowned frontispieces for Malory’s narrative (which in the meantime had been completed in print), and a number of vignettes. It also reflected an evolution in the artist’s style thanks to several drawings from the Yellow Book, launched in April 1894, from which Beardsley had been dismissed a year later, in particular the controversial covers of volumes one and three, and the red-light drawing L’Éducation Sentimentale, in which an old bawd sweet-talks a young apprentice.

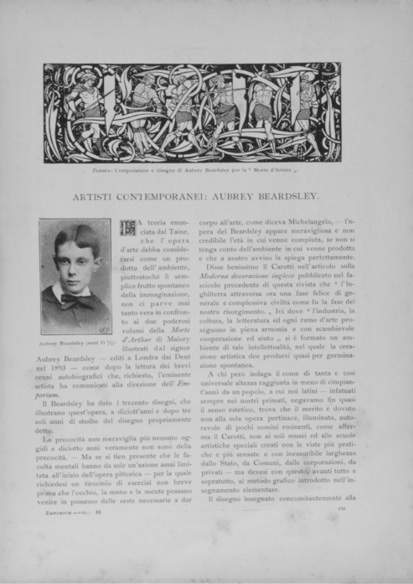

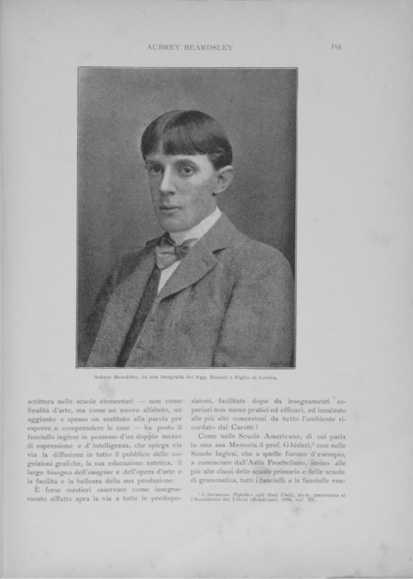

Pennell, quoted and translated, provides in conclusion the main argument legitimising the Italian article itself: the risk taken in presenting a young artist. It is then fitting that the artist be shown in his prime: on the first and third page, two photographic portraits of Beardsley as a child (Fig. 4.4), with the caption “11½ years” (“anni 11½”), and of Beardsley as a young man (Fig. 4.5), are much more than a biographical illustration: they are proof of his precociousness. The article prosaically justifies it by discussing the English educational system that introduces graphic drawing as early as primary school alongside learning the alphabet and practising handwriting. There is no shortage of praise for Beardsley’s work (rare inventive power, perfection of execution, intellectualism of subject, intensity of expression typical of true works of art), and no shortage of criticism either: this “product of a great centre of refined civility” (an expression that reflects the Anglomania well engrained in Italy since the eighteenth century)23 is the author of the “too independent” plates for Wilde’s scandalous Salome. With his figures “out of the orbit with the work,” he breaks free from illustration, which in the end captivates G. B.24 His enthusiastic paragraph on J’ai baisé ta bouche Iokanaan transposes the work of art into a purple patch, i.e., a piece of ornate writing. Two months later, the November 1895 issue of Emporium echoes a similar fascination: the cover hosts one of the most disturbing Salome drawings, The Dancer’s Reward (Zatlin 873), in which the lustful protagonist avidly takes possession of the prophet’s head, while an opinion piece by “Neera” (Anna Zuccari) defends the primacy of idea over form in the work of art with the Emporium editors’ blessing.25 Uncommented iconography includes Beardsley’s Salome drawing on the Emporium cover.

Fig. 4.4 Beginning of G. B.’s article on Beardsley, Emporium, 2:9 (Sept 1895): 192. Photograph of Beardsley at eleven and a half and decorative header for Le Morte Darthur. Courtesy DocStAr, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, Pisa

Fig. 4.5 A further page from G. B.’s article on Beardsley, Emporium, 2:9 (Sept 1895): 195. Photograph of the artist as a young man. Courtesy DocStAr, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, Pisa

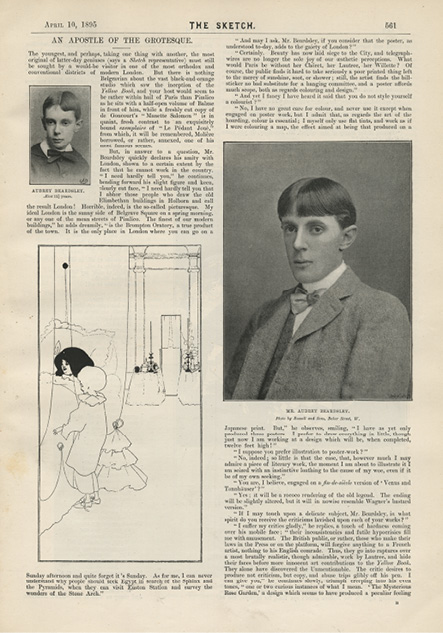

G. B.’s article shows that contact had been made with the artist himself (then working for Leonard Smithers after Lane had dismissed him from the Yellow Book): Beardsley had supplied the photographs as well as a brief biography, faithfully translated into Italian. Both photographs had appeared in London’s Sketch, a general-public periodical that had published an interview with Beardsley at home under the title “An Apostle of the Grotesque.” An infant Pierrot, drawn standing next to a bedridden woman, possibly his mother, accompanied the photos (Fig. 4.6). The latter, Child at its Mother’s Bed (Zatlin 262), has autobiographical overtones.26 It is also the oldest picture of Beardsley as Pierrot, ably stage-managing his Sketch interview as a one-man show. The entire page layout (with both photographs and drawing of Child at its Mother’s Bed) reflected the article’s opening sentence: “The youngest, and perhaps, taking one thing with another, the most original of latter-day geniuses…” The visuals show Beardsley, the ingenious child. Moreover, the set up is a response and delightful nod to Max Beerbohm’s interview published four months earlier in this very same Sketch signalling his peer’s precociousness and genius. Beerbohm, we remember, had illustrated his Sketch interview with his photograph as a ten-year-old child in a sailor’s collar, the text emphasising the extreme youth he shared with Beardsley (see Fig. 2.9). Beardsley and Beerbohm, very close friends, cultivated artistic attitudes as they caricatured each other in mirror portraits with dogs. As artists they styled themselves as enfants terribles, bad yet gifted boys of the Nineties.

Fig. 4.6 “An Apostle of the Grotesque,” Aubrey Beardsley’s interview with Child at its Mother’s Bed and the two photographs republished in Emporium (see Fig. 4.4 and 4.5). The Sketch, 9 (10 Apr 1895): 561. University of Minnesota Libraries

With the artist’s personal participation, Emporium’s article built on this stance, hardly aware that Beardsley was ably manipulating his image from a distance. Little known in Italy, Smithers’s reputation as seller of erotica and books under the table, is not mentioned. The tone, however, becomes patronising when G. B. advises Beardsley not to pursue the path of childishness (“puerilità”). Had he grasped the irony of such a word, uttered out of the blue, when his article was illustrated by Beardsley’s photograph as an eleven-and-a-half-year-old? Perhaps not… Besides, the objection “puerilità” is not originally G. B.’s, but Ernest Knaufft’s, the censor of The Procession of Joan of Arc in the American Art Student, relayed by Grand-Carteret’s French Le Livre et l’Image.

The Emporium article closely follows Le Livre et l’Image. It opens with Battling Knights, the very header from Le Morte Darthur reproduced in Le Livre et l’Image two years earlier (see Fig. 4.4), and offers the same Morte Darthur plate of Merlin. However, Le Livre et l’Image had also included the following comment by Knaufft, translated into French, with emphasis on no other term but childishness: “Aubrey Beardsley’s work is puerile in its intellectual side. On seeing the May Studio [i.e., the full-size replica of The Procession of Joan of Arc], our humble opinion is that the young illustrator’s technique can at times be ‘puerilissimo’…”27 Inadvertently, the Emporium contributor had passed on the word at his own expense. And yet, he was fully aware of the hoaxes and pranks played by Beardsley on his English critics. Indeed, G. B. recalled the controversy surrounding a portrait of Andrea Mantegna in Mantegna-like style, published in volume three of the Yellow Book, which Beardsley had signed as “Philip Broughton” (Zatlin 905).28 Several critics had praised Broughton’s qualities by contrasting them with the horrors published in the magazine by… Aubrey Beardsley! The hoax had worked, and G. B. knew exactly why, having read in the Sketch how Beardsley let the cat out of the bag. Now, in Emporium, the prank on precociousness was at the expense of G. B. himself, bluffed by Beardsley and his photographs.

Trick aside, the first Emporium article on Beardsley illustrates how the network of magazines forms and operates: it is as much iconographic as it is textual; it borrows opinions, texts, images, and arguments from art periodicals (the Studio), fin-de-siècle quarterlies (the Yellow Book), general-public magazines (the Sketch), and books (Le Morte Darthur, Salome); it backs the artist’s reputation for precociousness (sustained by childhood photographs) thanks to the Sketch, through the American Art Student, relayed by the French Le Livre et l’Image. The mix proved all-powerful from Britain to Italy, via the United States and France, and through it Beardsley became internationally renowned.

Fig. 4.7 Aubrey Beardsley, How Morgan le Fay Gave a Shield to Sir Tristram (by 3 Oct 1893), full-page plate from Le Morte Darthur, Bk. IX, chapter xl (Zatlin 539), repr. Emporium, 7:41 (May 1898): 322, issue frontispiece just after the advertisement pages. Courtesy DocStAr, Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, Pisa

Compared to the Studio’s unsympathetic obituary, Emporium’s (anonymous) version29 stands out for its sobriety, its large frontispiece paying tribute to Beardsley (How Morgan le Fay Gave a Shield to Sir Tristram, a full-page plate from Le Morte Darthur, Fig. 4.7, Zatlin 539), but also its brevity (three and a half pages) and moderate iconography: none of the great final drawings are included, although reference is made to the refined plates of the Savoy and The Rape of the Lock (published by Smithers in 1896). The reproductions, mostly secondary – with the exception of The Peacock Skirt from Salome (Zatlin 866), and The Wagnerites (Zatlin 908), of great decorative force, hampered however by their quarter-page reproduction – adhered to the Yellow Book’s black-and-white idiom. Was this choice a result of caution? Restraint? A dearth of images? The article opens and closes with Beardsley’s deathbed conversion to Catholicism, a reiteration that could not fail to move Catholic readers in the Italy of Umberto I, son of Vittorio Emmanuele, “padre della patria.” The obituary also recalls the first article in Emporium, albeit indirectly. The artist’s precociousness is no longer justified by the English education system. However, opening the issue, an article by Helen Zimmern, a German-British writer and translator, “Il sistema Prang nell’insegnamento dell’arte,” insists on the educational progress in American kindergartens,30 a discreet reminder of the article three years earlier, which had allowed the prodigy Beardsley to blossom at the age of eleven and a half. In its tribute to an exceptional artist, Emporium failed, however, to explain why his art was so important and influential.

Pica’s Aesthetic Choices

Vittorio Pica, though, had already been working on Beardsley in the Italian periodical. As early as February 1897, in an Emporium article on modern posters, Pica had pointed out Beardsley’s originality: the warping of the human figure in his work, Pica argued, is neither gratuitous nor caricatural, but grants psychological complexity and a greater elegance to his figures. Thus, the woman on Beardsley’s poster for Todhunter’s A Comedy of Sighs! (see Fig. 4.2) is remarkable for something both “leonardesque” (i.e., reminiscent of Leonardo da Vinci) and “Japanese-like.” Anticipating the Studio’s disparaging obituary, which would strongly criticise that very poster, Pica’s argument adopted an entirely different set of values.31 Francesca Tancini has shown that the iconography and layout of Pica’s article were partly borrowed from New York’s Scribner’s Magazine,32 but the critical viewpoint and appreciation were entirely new. In a similar vein, in November 1902, Pica illustrated an article on Émile Zola with Beardsley’s Japanese drawing of the writer (Zatlin 289) and his stylised “mask” by Félix Vallotton in La Revue blanche.33 Pica’s selection of visual material subtly connected Vallotton and Beardsley by way of their black-and-white graphics, showing how they mutually influenced each other.34 They both used flat surfaces and strong outlines, stylised compositions, encouraged abstraction, and adapted their art to new printing technologies.

In May 1904, Pica’s article, entitled “Tre artisti d’eccezione,” was a celebration of Beardsley’s, Ensor’s and Munch’s talents combined.35 It began with a reference to what Pica calls in italics “the Saturday plague” (“il supplizio del sabato,” emphasised): the two-penny illustrated weeklies that were seen to pollute the viewers’ eyes and distort their taste. To alleviate the torment of the magazines’ “brazen polychromatic coarseness” (“la sfrontata loro grossolanità policroma”), Pica turns to cerebral artists, whose refined and suggestive designs soothe the pain inflicted by the rampant expansion of the press. Recalling the Studio’s first article, Pica presents Beardsley as the first figure in a remarkable family, the article’s trio, with supplementary reference to Charles Baudelaire, Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly and Paul Verlaine as avant-garde writers and artist Félicien Rops. Pica emphasises Beardsley’s inventiveness, his exceptional craftsmanship, his indisputable originality, and the role of the unconscious manifest in his work. He points out that the concern for style is predominant. Satire in Beardsley? Yes, undoubtedly, but animated by “a pitiless moralist’s mind” (“una mente di moralista spietato”), that of the Goya of the Caprichos. Pica had read Arthur Symons’s monograph on Beardsley, originally published in the Fortnightly Review, either in the magazine or in book form,36 and recommended it to his readers, endorsing one of the most vivid tributes to the artist at the time. Finally, Pica responded to all those who objected to the abnormal, the artificial, the convoluted, with a strong argument, already made by Franz Blei in the first German article entirely devoted to the designer:37 Beardsley cannot appeal to everybody. A year later, the Mercure de France would publish Pica’s prose in full French translation without the images.38

However, Beardsley’s images were relatively downplayed. Driven by a desire to make the other two artists better known,39 Pica granted him only four figures against seven for Ensor, and nine for Munch. But the selection of images is well laid out and not prudish:40 it opens with the first of the three drawings titled The Comedy-Ballet of Marionettes, as Performed by the Troupe of the Théâtre-Impossible (published in the Yellow Book and relayed by Le Courrier français as shown in the next chapter), continues full-page with The Battle of the Beaux and the Belles, one of the most accomplished plates from The Rape of the Lock (Zatlin 984), includes the powerful Messalina Returning Home after Juvenal’s sixth satire (Zatlin 948), and closes with The Death of Pierrot, an emblematic drawing, as the next chapter shows (Zatlin 1015). The latter two are laid out centrally and facing each other on opposite pages. Beardsley’s fine portrait by Jacques-Émile Blanche, already reproduced by Symons, accompanies the plates, reminding the reader that the talented artist was also an elegantly dressed dandy. An aesthetic tribute, illuminated with insight, the article is a curtain falling on a short play’s din.

Pica amended the standpoint of the first two Emporium articles by G. B., yet his own coup de coeur did not have the polish of a final judgment either. The carefully balanced 1903 text given by the Danish art historian Emil Hannover to Kunst und Künstler, a prestigious art journal focusing on European art and launched in 1902 in Berlin by Bruno Kassirer, easily takes the cake.41 Its iconography pays tribute to three outstanding books, Le Morte Darthur, Salome, and The Rape of the Lock, each of which gets a characteristic full-page image. The frontispiece of Le Morte Darthur (How King Arthur Saw the Questing Beast, Zatlin 424) is replicated at the beginning of the article with great care, and is an especially difficult drawing to reproduce. The article’s eight symmetrically arranged pages form a genuine composition, where images prevail over words, pausing at three key moments in the work: the medieval production, Salome’s black-and-white drawings tending towards abstraction, and the fine needlecraft inspired by Pope’s poem.42 By comparison, even though Pica’s pen has done Beardsley justice with rare acuity, Emporium’s iconographic selection lets its critic down.

Humour and Advertisement

The smell of scandal that accompanied Beardsley – critiques, polemics, and facetious jabs – were all ultimately an asset to his work, and an incentive for members of the public to discover it for themselves. Beardsley himself deliberately provoked these outraged responses, as we have seen in the case of his portraits. The Chap-Book: A Miscellany & Review of Belles Lettres (1894–98), a refined American art and literature journal issued by art publishers Stone and Kimball in Chicago that would reach 16,500 subscribers, provides a good case study. The term chapbook suggests pedlars’ literature and popular prints, but the Chicago review, a house organ and “a semi-monthly advertisement and regular prospectus for Stone and Kimball,” verged on the deluxe.43 Small in size and neatly printed, the periodical contained a range of very free uses of Beardsley’s drawings. Beardsley certainly knew Stone and Kimball – he was frequently quoted or referred to in the periodical, and had been commissioned by the publishers to illustrate a deluxe edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s works (Zatlin 926–29). Yet it is difficult to argue that he was himself involved in his multiple appearances in the Chap-Book. He had managed to manoeuvre and stage-manage his image in Emporium through Sketch, but allusions, skits, and iconography circulated beyond his control across the Atlantic. They were carried by his growing notoriety, granting him further publicity, and had a distinct commercial flavour.

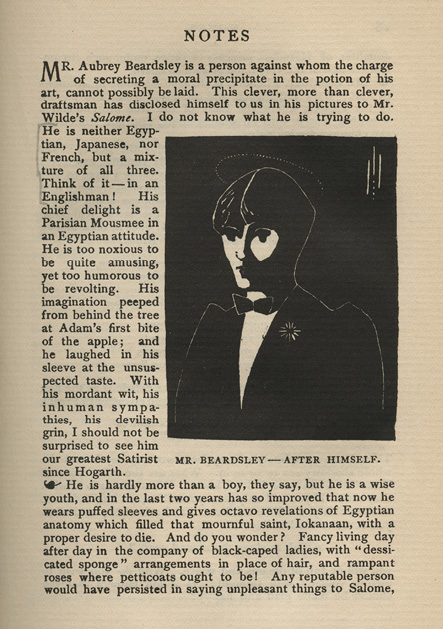

Fig. 4.8 Beardsley’s portrait with a saint’s halo published with “Notes,” The Chap-Book, 1 (15 May 1894): 17. University of Minnesota Libraries

In Chap-Book’s first issue, “Notes” is coupled with Beardsley’s aesthetic and hagiographic portrait crowned with a halo.44 The image showcases the artist’s elegance and black-and-white technique (Fig. 4.8), but it is unclear whether it is apocryphal, a pastiche of Portrait of Himself45 as the caption Mr Beardsley – After Himself signals, or an authentic work (signed top right with his Japanese signature). It is not credited in the table of illustrations, nor attributed to Beardsley in the catalogues of his work. Similarly, on his Salome designs, the second issue of 1 June 1894 includes a clever anonymous limerick, “The Yellow Bookmaker.”46 The title is a pun on the dealer of bets who determines odds, but also refers to the art editor and designer of the Yellow Book. It implied that Beardsley’s major and winning bet was indeed this quarterly: his star had also risen thanks to the periodical press he so cleverly handled. The last verses included full purchasing instructions for those who would like to acquire Salome from Copeland and Day, the Chap-Book publishers also managing its sales for the American market:

P. S. If you’re anxious to see

This most up to date Salomee

Send over the way

Cornhill, in the Hub, dollars three –

And seventy

five

cents.47

These amusing, parodic contributions bow to a key fin-de-siècle rebellious spirit, foundational to the avant-garde reviews that challenged the editorial status quo and disputed attitudes of authority. They arise from a stance that uses parody and paradox as roundabout forms of manifesto.48 Beardsley was no stranger to this. His Sketch interview hallowed him in half-reverential, half-mocking fashion, as “An Apostle of the Grotesque.” It touted paradoxes wilfully cultivated, elaborated on his French culture and, of course, his precocity, with the childhood photographs as supporting evidence. Like the gargoyle shots by Evans (see Fig. 3.10 and Fig. 3.11a), they took part in a strategy to turn the Decadents into fin-de-siècle bad boys (pueri), promising yet already exhausted “elderly youths.”49 The puer produced naturally infantile drawings in a puerilissimo manner.

Singularity and Interchange

Avant-garde literature and art reviews were by nature malleable. They have been termed “small magazines,” which has obfuscated their multifaceted identity and their relations with dominant periodicals and the mainstream press.50 Nuances are necessary. The versatility and openness of the so-called “little reviews,” as well as their undogmatic ideological and aesthetic positions, allowed avant-garde ideas to sift into larger-circulation magazines such as Emporium, designed a priori for a well-to-do bourgeois readership. In turn, Emporium expanded beyond its national and thematic borders by blending general-interest material and fine and applied art, with avant-garde literature and high art reviews.

Styled on the visual pattern of the Studio, and informed by both the fine art and general press of the time, the first Emporium article was subverted by the artist’s own covert contributions. They model his persona on a more widely shared paradigm, alien to the earnestness and gravitas of the Italian periodical. Similarly, Pica’s doubtless highly extensive art documentation does not fully explain all the iconographic choices of his last article, in particular the last plate, The Death of Pierrot (Zatlin 1015). Its symbolic weight is only fathomable if we consider Beardsley’s obituaries in French art and literature reviews, as shown in the following chapter.

Comparison between periodical genres shows how Beardsley was portrayed and perceived across different journals and countries. A fine and applied art journal for educated readers, such as the Studio, was seminal in launching his career, crucial in disseminating his style and first images, and yet bordering on offensive in its epitaph. As a large-circulation magazine for the general public, the Sketch supported rumour and boosted its print run by publishing unsigned articles such as “An Apostle of the Grotesque,” with Beardsley wittily staging himself as a child prodigy through an early photograph and an artwork. His precocity had nonetheless been sternly criticised in the American Art Student as puerilità – both (artistic) immaturity and juvenile irresponsibility, no doubt. Yet a detail of The Procession of Joan of Arc was taken seriously by Emporium, the anonymous G. B. falling unconsciously into the trap laid by Beardsley’s prank. While Emporium voiced approval but also informed its readers of the Broughton controversy, the French Le Livre et l’Image and the German Kunst und Künstler served as European mediators of the artist’s growing fame over the Continent. Contrariwise, over the Atlantic, the Chap-Book freely played with Beardsley’s images and identities in gratifying satires to the point of counterfeiting him. Such a survey, however, is neither sufficient nor explains everything. Beyond the artist himself, affecting public opinion and iconography in a skilful way, the periodical press proves to be the major force in his myth making. His provocative work is media-supported and media operating. It further produces mock-hagiographic or parodic images styled on Beardsley’s own (as in the Chap-Book here or E. T. Reed’s skit in Punch, analysed in the previous chapter) that perpetuate and enhance his spirited stances.

Any network of periodicals may form and develop thanks to select personalities – journalists, editors, publishers – coming together in a specific place and time. They engage in mutual reading, critique, debate, acknowledgment, and/or acceptance around key images, which may not always correspond to their individual choices but to iconic representations moulded by press circulation. Such personalities foster a myth-creating iconography of talented artists like Beardsley, well aware of the images’ symbolic value and function. Insightful critics such as Pica play a part in fostering Beardsley, as do the editors of L’Ermitage, Franz Blei in Pan, Sergei Diaghilev in Mir iskusstva, or Emil Hannover in Kunst und Künstler. And yet, these interpersonal relations may obscure the exchange value of periodicals per se, whether small, medium, or large, and their media performance. The exchange flow that produced immaterial ideas and linked them to material forms was a force behind Beardsley’s images, his posing, and affectation. A reticular study of periodicals shifts the point of gravity of creations: it considers them not in themselves but rather in terms of exchange – visual, intellectual, symbolic, emotional, or relational. The periodical is not then a finished or stable object, but a practice (of texts, images, forms, shared by a community) and a process, which both privilege transfers and exchange. Beardsley’s impish work took clear advantage of this from the heart of London to a distant Emporium of extensive influence.

1 Nicholas A. Salerno, “An Annotated Secondary Bibliography,” in Reconsidering Aubrey Beardsley, ed. by Robert Langenfeld (Ann Arbor, Mich./London: U.M.I. Research Press, 1989), 267–493.

2 This would have been more apparent if a chronological (instead of an alphabetical) order had been adopted as in Jane Haville Desmarais, The Beardsley Industry: The Critical Reception in England and France, 1893–1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998), 132–48, and Linda Gertner Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley: A Catalogue Raisonné, 2 vols. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2016), II, 481f, particularly for the years 1893–1900.

3 Henry-D. Davray, “L’Art d’Aubrey Beardsley,” L’Ermitage, 14 (Apr 1897): 253–61 (254): “Si suivant l’exemple de M. Whistler, il publiait toutes ses coupures de presse, cela formerait certainement un recueil des plus intéressants et plein d’enseignements. Car il fut proclamé, discuté et vilipendé au-delà de tout dire.”

4 Joseph Pennell, “A New Illustrator: Aubrey Beardsley,” The Studio, 1:1 (Apr 1893): 14–19.

5 G. W. [Gleeson White], “Aubrey Beardsley: In Memoriam,” The Studio, 13 (May 1898): 252–63.

6 The delay was all the more noticeable as the Mercure de France immediately announced Beardsley’s demise in its “Échos,” 26:100 (Apr 1898): 335, before transforming its May 1898 issue into a vibrant tribute to the deceased artist (see Chapter 5).

7 Margaret D. Stetz, Aubrey Beardsley 150 Years Young (New York: The Grolier Club, 2022), 39.

8 G. W. [Gleeson White], “Aubrey Beardsley: In Memoriam,” 259.

9 “Ars Postera,” Punch, 106 (21 Apr 1894): 189.

10 Alexandre de Riquer, “Aubrey Beardsley,” Joventut, 1 (15 Feb 1900): 6–11.

11 A. N. [Al’fred Nurok], “Obri Berdslei,” Mir iskusstva, 1:3–4 (1899): 16–17. Sergei Diaghilev further used two drawings by Beardsley to illustrate an article on the principles of artistic evaluation. See Sergei Diagilev, “Slozhnye voprosy: Osnovy khudozhestvennoi otsenki”, Mir iskusstva, 1:3–4 (1899): 50–61.

12 Franz Blei, “Aubrey Beardsley,” Pan, 5:4 (Nov 1899–Apr 1900): 256–60.

13 Un Book-Trotter, “L’Image: Titres réduits des nouveaux périodiques anglais,” Le Livre et l’Image, 2:6 (Aug 1893): 57, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6118702f/f80.item

14 Un Book-Trotter. “L’Image: Mille moins un petits papiers. Les illustrations d’Aubrey Beardsley,” Le Livre et l’Image, 2:7 (Sept 1893): 120, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6118702f/f149.item

15 Un Book-Trotter, “L’Image: Mille moins un petits papiers. Le ‘Studio’ critiqué,” Le Livre et l’Image, 2:9 (Nov 1893): 249: “quarante-trois nez retroussés.” Ernest Knaufft, himself a draughtsman, teacher, and lecturer, was the editor of the Art Student: An Illustrated Monthly for Home Art Study, or A Monthly for the Home Study of Drawing and Illustrating, published in New York from 1892 and a regular contributor to the Review of Reviews. See Peter Hastings Falk, ed., Who Was Who in American Art, 1564–1975 (Sound View Press, 1999), 1871.

16 John Grand-Carteret, “Le livre illustré à l’étranger: Angleterre – Allemagne – Suisse,” Le Livre et l’Image, 3:13 (10 Mar 1894): 129–49 (header reproduced, 129), https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5425700g/f154.item

17 Maria Elisabetta Manca, “Specchio di ‘Emporium:’ le riviste della biblioteca dell’Istituto Italiano d’Arti Grafiche di Bergamo,” in Emporium: Parole e figure tra il 1895 e il 1964, ed. by Giorgio Bacci, Massimo Ferretti, Miriam Filetti Mazza (Pisa: Edizioni della Normale, 2009), 155–70.

18 Such enquiries have been led from 2006 in two collections edited by Évanghélia Stead and Hélène Védrine, L’Europe des revues (1880–1920): Estampes, photographies, illustrations (Paris: PUPS, 2008), repr. 2011, and L’Europe des revues II (1860–1930): Réseaux et circulations des modèles (Paris: PUPS, 2018).

19 See Paola Pallottino, “‘La finezza, il numero, la veracità delle illustrazioni:’ l’opera pioneristica di Vittorio Pica su ‘Emporium’,” in Emporium: Parole e figure tra il 1895 e il 1964, 203–18.

20 See Vittorio Pica, Attraverso gli albi e le cartelle: sensazioni d’arte, seconda serie (Bergamo: Istituto Italiano d’Arti Grafiche, 1907), 89–135.

21 G. B., “Artisti contemporanei: Aubrey Beardsley,” Emporium, 2:9 (Sept 1895): 192–204.

22 See https://emporium.sns.it/galleria/pagine.php?volume=II&pagina=II_009_192.jpg and ff.

23 See Arturo Graf, L’Anglomania e l’influsso inglese in Italia nel secolo XVIII (Turin: E. Loescher, 1911).

24 G. B., “Artisti contemporanei: Aubrey Beardsley,” 202–203: “prodotto da un grande centro di civiltà” (203); “la sua tendenza a esorbitare dal mondo tangibile” (202); “opera d’arte autonoma ed indipendente” (202).

25 Anna Zuccari Radius, “La coltura degli artisti,” Emporium, 2:11 (Nov 1895): 337–43.

26 Zatlin, Catalogue Raisonné, I, 158.

27 Un Book-Trotter, “L’Image: Mille moins un petits papiers,” Le Livre et l’Image, 2:9 (Nov 1893): 249, my emphasis: “L’œuvre d’Aubrey Beardsley est puérile par son côté intellectuel. En voyant le Studio de Mai, notre humble opinion est que la technique du jeune illustrateur peut par moments être ‘puerilissimo’....”

28 The Yellow Book, 3 (Oct 1894): 9.

29 “Artisti contemporanei: Aubrey Beardsley. In memoriam,” Emporium, 7:41 (May 1898): 352–55. See https://emporium.sns.it/galleria/pagine.php?volume=VII&pagina=VII_041_352.jpg and ff.

30 Helen Zimmern, “Il sistema Prang nell’insegnamento dell’arte,” Emporium, 7:41 (May 1898): 323–39.

31 Pica, “Attraverso gli albi e le cartelle,” Emporium, 5:26 (Feb 1897): 99–125, mainly 113–14. Reprinted in Attraverso gli albi e le cartelle (sensazioni d’arte), prima serie (Bergamo: Istituto Italiano d’Arti Grafiche, 1904), 279–324.

32 See Francesca Tancini, “L’ultimo dei pittori preraffaelliti: Walter Crane e ‘Emporium,’” in Emporium: Parole e figure tra il 1895 e il 1964, 389–93, fig. 94 and 95.

33 Pica, “Letterati contemporanei: Émile Zola,” Emporium, 16:95 (Nov 1902): 373–86 (Beardsley’s drawing, 376). See https://emporium.sns.it/galleria/pagine.php?volume=XVI&pagina=XVI_095_376.jpg

34 See Jacques Lethève, “Aubrey Beardsley et la France,” Gazette des beaux-arts, 68:1175 (Dec 1966): 347. Lethève argues that Beardsley was influenced by Vallotton’s wood engravings.

35 Pica, “Tre artisti d’eccezione: Aubrey Beardsley – James Ensor – Edouard Münch [sic],” Emporium, 19:113 (May 1904): 347–68.

36 Arthur Symons, “Aubrey Beardsley,” The Fortnightly Review, n.s., 63:377 (1 May 1898): 752–61; Symons, Aubrey Beardsley (London: At the Sign of the Unicorn, 1898).

37 Franz Blei, “Aubrey Beardsley,” Pan, 5:4 (Apr 1900): 256–60.

38 Pica, “Trois artistes d’exception: Aubrey Beardsley, James Ensor, Édouard Münch [sic],” Mercure de France, 56:196 (15 Aug 1905): 517–30.

39 Two drawings by Ensor had already appeared in Emporium, in Pica’s article “L’esposizione di bianco e nero a Roma,” 16:91 (July 1902): 32–33, but no work by Munch. The only other articles to focus on them appear much later: 1935 for Munch (Antony De Witt, “Pittura norvegese moderna”), 1946 for Ensor, on the occasion of a retrospective.

40 See https://emporium.sns.it/galleria/libro.php?volume=XIX&pagina=XIX_113_347.jpg and ff.

41 Emil Hannover, “Aubrey Beardsley,” Kunst und Künstler, 1:11 (Nov 1903): 418–25.

42 See Heidelberg Historic Literature, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kk1902_1903/0427/image,info,thumbs#col_thumbs

43 See Alma Burner Creek, “Herbert S. Stone and Company,” and “Stone and Kimball,” in American Literary Publishing Houses, 1638–1899, Part 2, ed. by Peter Dzwonkoski and Joel Myerson (Detroit, Mich.: Gale Research Company, 1986), 436–40 and 440–43 (442). See also Giles Bergel, “The Chap-Book (1894–8),” in The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines. II. North America 1894–1960, ed. by Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 154–75.

44 Pierre La Rose, “Notes,” The Chap-Book, 1:1 (15 May 1894): 17–18.

45 The Yellow Book, 3 (Oct 1894): 51. See Fig. 3.3 in this book.

46 Pierre La Rose, “The Yellow Bookmaker,” The Chap-Book, 1:2 (1 June 1894): 41–42.

47 Ibid., 42.

48 On this important point, see Linda Dowling, Language and Decadence in the Victorian Fin de Siècle (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986), 179–81, and Évanghélia Stead, Le Monstre, le singe et le fœtus: Tératogonie et Décadence dans l’Europe fin-de-siècle (Geneva: Droz, 2004), 22–23.

49 See previously, Chapter 2.

50 See Evanghelia Stead, “Introduction,” Journal of European Periodical Studies, special issue “Reconsidering ‘Little’ versus ‘Big’ Periodicals,” 1:2 (2016): 1–17.