5. Paris Performance

Alive and Dead

©2024 Evanghelia Stead, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0413.05

“Si j’allais à Paris, je guérirais,” so John Gray reminded French readers of his obituary in La Revue blanche, echoing Aubrey Beardsley’s own words: “If I went to Paris, I would recover.”1 Beardsley’s wishful thinking was not to be granted, although his art had repeatedly benefitted from a deeply rooted Francophile inspiration. As for Oscar Wilde, France was for Beardsley the land of free morals and free expression, as opposed to British prudery and conservatism. In his short life, the artist had enjoyed four lengthy stays in Paris. First in May 1892, when he first visited the Louvre, discovered the Salons and a wealth of exhibitions; then in May 1893, with his sister Mabel and the Pennells, to more Salons, the opera, the Latin Quarter, and the thrill of new acquaintances (including the poet Stéphane Mallarmé); then again in February 1896, initially with Leonard Smithers, when he went not only to parties and on other intoxicating adventures, but also to the Salomé premiere performed at the Comédie Parisienne by the Théâtre de l’Œuvre company, and was hard at work illustrating Alexander Pope’s heroic-comic poem, amongst his masterpieces; lastly, from April 1897 to his death on 15 March 1898, he stayed partly in the capital and partly travelled around France. For the first part of this final visit, he experienced a brief improvement in health, was in exhilarating spirits, and met the novelist Rachilde and her Decadent protégés. He stayed in Saint-Germain-en-Laye and Dieppe, then returned to Paris. His last trip in 1897 took him to Menton, on the French Riviera, whence he would not return.

Early on he had shown his first work to Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, the symbolist painter, then President of the Champ de Mars Salon, who was also in the habit of drawing caricatures and grotesques.2 An avid reader of French literature, Beardsley artfully employed French captions, usually with a naughty double entendre, in his drawings. He cultivated a French aesthetic when he decorated his rooms at 114 Cambridge Street, and put French inflections into the titles of his works. At the age of fifteen, he began applying the French article La to French or Frenglish words, paying no attention to the rules of gender. In a series of sketches caricaturing Ebenezer J. Marshall, headmaster of Brighton Grammar School, young Beardsley labelled them La Apple, La Discourse, La Lecture, La Chymist (Zatlin 89–92). At sixteen, he performed with his schoolmates in Thomas J. William’s farce Ici on Parle Français on French travellers’ linguistic exertions in England, and produced more sketches (Zatlin 98–103). Confined to bed by frequent haemorrhages between autumn 1889 and spring 1890, he read numerous French novels and drew a rich gallery of characters from Abbé Prévost’s Manon Lescaut; Alexandre Dumas fils’s La Dame aux camélias, the consumptive courtesan with whom he identified; Alphonse Daudet’s Tartarin de Tarascon, Sappho, and Jack; Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary; Victor Hugo’s L’Homme qui rit; Honoré de Balzac’s Le Curé de Tours, Le Cousin Pons, and Les Contes drolatiques; and even Jean Racine’s Phèdre (Zatlin 146–63, 165–67). He also often portrayed French writers in his own artwork: Alphonse Daudet (Zatlin 159), Émile Zola (Zatlin 288 and 289), Henri Taine (Zatlin 300r and 300v), and Molière (Zatlin 221). His early drawings and Japonesques used French titles and characters as in The Birthday of Madame Cigale (Zatlin 266) and La Femme incomprise (Zatlin 264). He slipped French words into his plates after Wilde’s play (Salome on a Settle, Maîtresse d’Orchestre; The Toilette of Salome, Zatlin, 878, 871 & 877). Already in 1893, he had read it in its original French and his design and drawings for the English translation would establish him as a designer. The first drawing he made for it bears in French the tragedy’s key line, “J’ai baisé ta bouche, Iokanaan, j’ai baisé ta bouche” (“I have kissed your mouth, Iokanaan, I have kissed your mouth”) (Zatlin 265), and startled the English public as it was published in the first article introducing his art.3

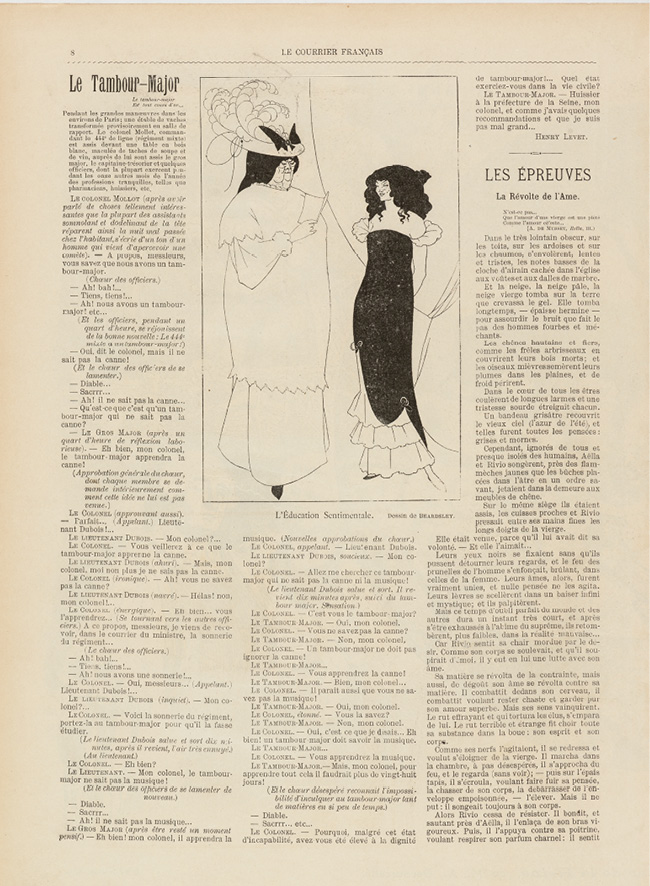

He excelled in hints and innuendos taken from French literature with a twist or a double meaning: if information is lacking on Notre Dame de la Lune (Zatlin 196), Le Dèbris d’un poète (Zatlin 244) relates to Beardsley himself an ironic quip from Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, as shown in Chapter 3. Il était une Bergère (Zatlin 263) plays with Yvette Guilbert’s spicy apex of a French folk song. Les Revenants de Musique (Zatlin 267) pictures a character, possibly Beardsley himself, haunted by the figures of Wagner’s operas. In Les Passades (Zatlin 337), he projects onto two street-walkers the double meaning of the colloquial la passade, both “short-lived love affair” and “partner in such an affair.” L’Éducation Sentimentale (Zatlin 889a) transposes the title of Flaubert’s novel from Frédéric Moreau, Flaubert’s “young man” (after the subtitle), to the lewd education of a young girl (see Fig. 5.4). Beardsley is supposed to have painted a portrait of Alfred Jarry’s Faustroll, the inventor of “’pataphysics,” and Jarry, impressed by The Rape of the Lock plates wrote an inspired piece in his honour, entitled “Du pays des dentelles” (“From the Land of Lace”). An admirer of the French language, Beardsley dreamt of importing French words into English, according to Blanche.4 In a nutshell, he was “the first Englishman who turned whole-heartedly to France,” as Julius Meier-Graefe put it.5

This chapter explores Beardsley’s reception in French periodicals and the press. It is a subject that has already received significant critical attention: following a 1966 article by Jacques Lethève,6 Jane Haville Desmarais has shown how Beardsley deliberately promoted his “French” and “Decadent” persona through press interviews.7 Yet in her attentive comparative study of Beardsley’s critical fortunes in Britain and France, Desmarais focuses on the text of these reviews, hardly mentioning the images. By contrast, I argue that reproductions of Beardsley’s work were in fact a more potent and pliant means of diffusion and influence than any text. Although I give text due consideration, this chapter focuses specifically on the visual aspect of Beardsley’s performance in French periodicals. Using new archival data, it explores the reproduction process he used so effectively, and analyses the impact of his images.

In doing so, it shows not only Beardsley’s eagerness to shock Britain by his French publications, but also his readiness to adapt his work to a foreign magazine’s varied contents and commercial considerations. His reception eludes expected patterns. Larger-circulation magazines wanted him more, and earlier, than avant-garde reviews. His death and the media chorus that mourned him gives final proof that Beardsley had lost control of his own image: although he did not wish to be associated with the potentially mawkish figure of Pierrot, it was the pathetic clown that became his posthumous symbol in the press. These two very different phases of Beardsley’s representation in the French fin-de-siècle press – before his demise when he exercised some control, and after his death when he had none – have a common denominator: the centrality of images in understanding the artist’s media performance and shaping his legend.

Entering the Stage

Beardsley’s French reception through periodicals stands out for three reasons. First, it was rapid. It preceded the Italian Emporium (Sept 1895) by two years, the Berlin Pan and the Russian Mir iskusstva (1899) by five, and the Catalan Joventut (1900) by six. Second, it bears witness to personal relationships, which Beardsley harnessed to graft his personality and artistic persona onto Victorian clichés of French Decadents, French mores, and French literature. When first mentioned in John Grand-Carteret’s Le Livre et l’Image, for instance, the magazine takes pride in implying direct contact: “a 20-year-old young artist, presently in Paris […],” although this is but a brief allusion to his effective presence in the capital.8 Contrariwise, Theodore Wratislaw had styled “the precocious development of [his] brain before the hand has been sufficiently trained” as a result of French influence on his work. His drawings were the only ones to reflect “the modern neurosis, the delight in anything strange and depraved, the curiosity of a decadent style.”9 Yet his reception in France, surprising and free, is at odds with established ideas.

Such freedom shows in the type of magazine to first host his work on French soil for quite some time. Jules Roques’s Le Courrier français, an illustrated Saturday weekly, founded in 1884 in Montmartre as an advertiser for Géraudel’s cough and cold tablets, covered literature, fine art, theatre, and additionally but sparsely, also medicine and finance. It promoted spirited and risqué drawings and a range of authors from Paul Verlaine to Jean Lorrain. It opened with a “rhyming gazette,” gossip in verse by Raoul Ponchon, a bohemian painter who loved songs, cabarets, and the bottle. Copies sold for 50 centimes with subscriptions at 12 francs 50 for six months and 25 francs for a year. The magazine served as a springboard for several new talents in illustration, as Roques constantly sought to renew its visual content by means of eye-catching effects, just as he used advertisement, literature, and politics.10

Le Courrier earned a reputation for being wicked: the writer Marcel Schwob’s liberal family advised him against writing for Le Messager français, with his father describing it in an 11 March 1891 letter as “a competitor in pornography of Le Courrier français.” He continued: “You are light-heartedly compromising your agrégation candidature, if you have not even dealt it a mortal blow. This is very, very unfortunate, and it almost seems as if you did it on purpose…”11 Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was in Roques’s journal that the first Beardsleys appeared in France in all their shocking variety. A book-enthusiasts’ journal like Le Livre et l’Image, which had preceded Roques’s by a year, had simply restrained itself to the medieval compositions of Le Morte Darthur.

There are two Beardsley seasons in Le Courrier français. The first, between November 1894 and April 1895, when Roques was the driving force, followed Roques’s prolonged London stays between 1893 and 1894 to escape legal proceedings, after which he hosted a series on British graphic artists. Beardsley would be by far the most active and productive of these, though the extent of his involvement is ambiguous: for Jacques-Émile Blanche, who knew him closely, the artist either “collaborated” or “collaborated a little” with Le Courrier français.12 The second period ran from February to July 1896, after a meeting in 1896 between Beardsley and two young men who would do much for him in French journals: the translator and critic Henry-D. Davray and the author and critic Gabriel de Lautrec, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s cousin.

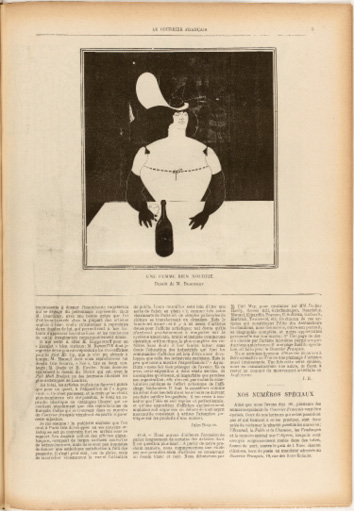

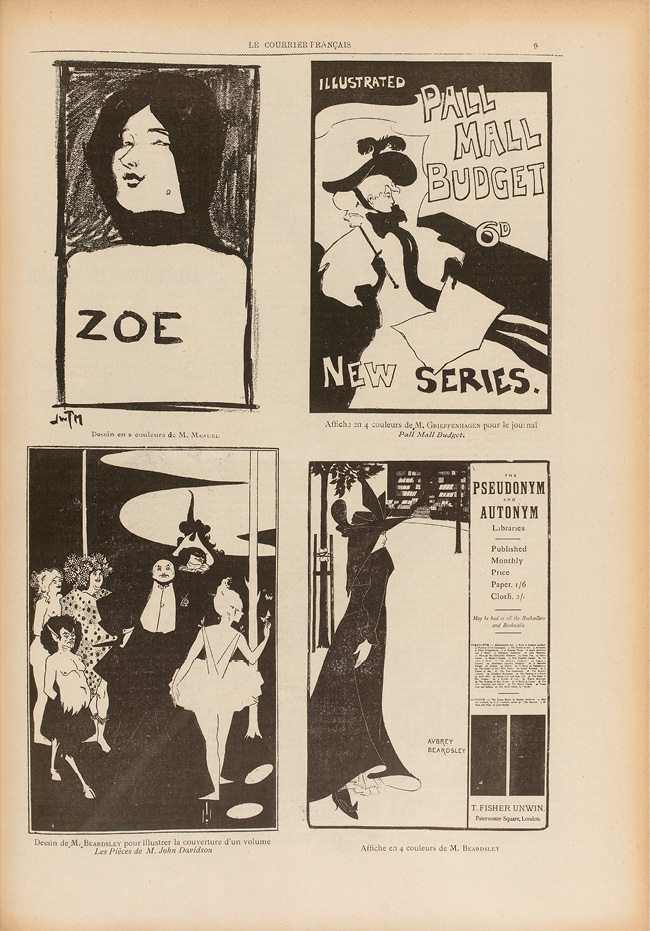

Beardsley was first mentioned in Le Courrier français on 11 November 1894 in an article on a poster exhibition. Roques made reference to Beardsley’s “uncommon weird imagination,” and included three drawings that had made headlines in London.13 Although evidence is lacking, it is safe to surmise that Roques’s weekly developed into a scandal platform, ably used to respond to the barbed judgements of the British press that Beardsley went about liberally provoking. In order to accomplish this, a main weapon was the choice of images, as shown in the initial three drawings that appeared in the French periodical. The first, Une femme bien nourrie (Fig. 5.1), also known as The Fat Woman and titled A Study in Major Lines in the catalogue raisonné (Zatlin 932), had shocked Lane with its sexual explicitness (a prostitute waiting for customers at the Café Royal) and the allusion to Degas’s The Absinthe Drinker then exhibited in London.14 Lane had refused publication in the Yellow Book and the drawing had appeared in To-Day magazine on 12 May 1894. The second (Fig. 5.2), the frontispiece to John Davidson’s Plays (Zatlin 331) drew on recent theatre events, a genre sponsored by Le Courrier français, to create an ambiguous universe by mixing real people, magnified by their momentous fame, with mythological characters.15 The Daily Chronicle had called it an “error of taste” because it displayed the easily recognisable portraits of Wilde and theatre manager Sir Augustus Harris. Beardsley had brazenly retorted that one of the gentlemen pictured was handsome enough to stand the test of portraiture (Wilde), the other owed him half a crown.16 As for the third drawing (Fig. 5.2) – a poster for T. Fisher Unwin’s “The Pseudonym and Autonym Libraries” (Zatlin 969) – it was, with its angular lines, Japanese perspective, and deliberately warped female figure, a comeback to the controversy caused by the poster for John Todhunter’s play A Comedy of Sighs! pasted all over London. It had caused a stir, which would be relayed as far as Italy.17

Fig. 5.1 Aubrey Beardsley, Une femme bien nourrie [The Fat Woman], catalogued as A Study in Major Lines (by Mar 1894), Tate collection, London, repr. Le Courrier français, 45 (11 Nov 1894): 5. BnF, Paris

Fig. 5.2 Le Courrier français, 45 (11 Nov 1894): 9, reproducing bottom left Aubrey Beardsley, Les Pièces de M. John Davidson [Frontispiece to John Davidson’s Plays (late Nov 1893)], and bottom right Affiche en 4 couleurs de M. Beardsley [Poster for T. Fisher Unwin’s The Pseudonym and Autonym Libraries (early 1894)]. BnF, Paris

The next month, Beardsley was formally introduced by Le Courrier français as part of a series of articles on emerging British poster artists, painters and press illustrators. A dozen of them were reviewed, but most artists had a more realistic and literal style: Phil May, Dudley Hardy, Leonard Raven-Hill, Maurice Greiffenhagen, J. Wright T. Manuel, Oscar (?) Eckhardt, Fred Pegram, Edmund Sullivan, Alfred Chantrey Corboult, Archibald Standish Hartrick and Frederick Henry Townsend, the art editor of Punch.18 In his general introduction to the series, Roques, conscious of the fact that previous lawsuits had granted his paper more than a whiff of scandal, took a stand on a recent London affair: the closing of the promenade and the ban on selling spirits at the Empire Theatre (similar to the Élysée-Montmartre, the venue he himself ran undercover and where the annual ball of Le Courrier français was held). He was looking for a promising new market in the English capital. He introduced English artists that he had personally met as the equals of “the most artistic of course, something like the equivalent of Messrs. Forain, Willette, Chéret, Legrand, Lunel, Anquetin, Grasset, L. O. Merson, Pille, Hermann Paul, Renouard, Raffaëlli, etc.”19

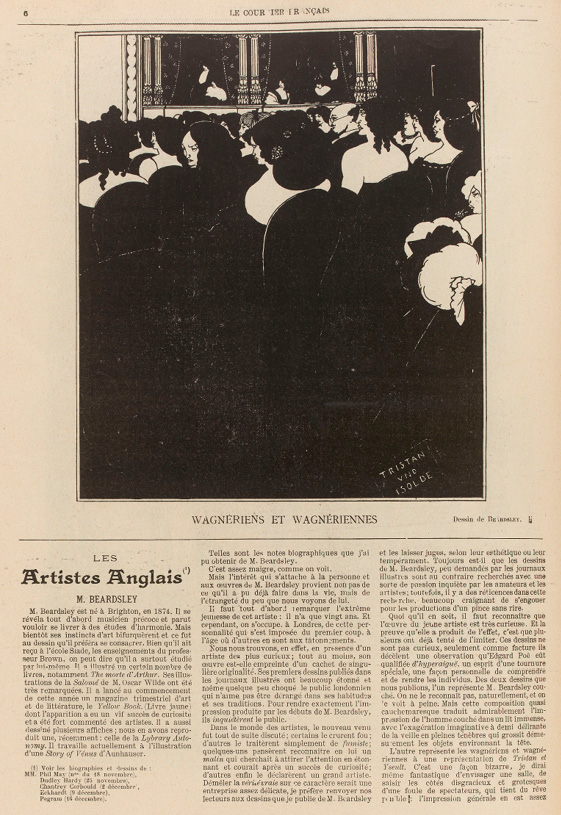

By featuring Beardsley’s interview in the 1894 Christmas issue (the series had started on 18 November with Dudley Hardy), Roques granted him a special place in the series (Fig. 5.3). The interview reflects Roques’s astonishment at the young age of this much-publicised artist; the curiosity and discomfort triggered by his drawings; admiration for his unique style; Beardsley’s acute feeling for distortion and the grotesque; and his ability to split a character into its real figure and its ghostly double. Some of these insights echo comments from the English press as steered by the artist himself. Others are more specifically French, such as references to Edgar Allan Poe, already used by Joris-Karl Huysmans in his art criticism to comment on Odilon Redon’s dark lithographs. Roques obviously borrowed from avant-garde journalism to comment on the British artist. His account, as delicate as it is fantastic, reveals fascination for Beardsley’s personality and the prospect for Roques to choose drawings to reproduce at will. Beardsley’s refusal to be paid for the interview (which must have delighted Roques) showed that he was ready to adapt in order to have his work published and diffused in France.

Fig. 5.3 Beginning of Jules Roques’s article, “Les artistes anglais: M. Beardsley,” Le Courrier français, 51 (23 Dec 1894): 6, reproducing the drawing The Wagnerites (May 1893–June 1894), V&A, London, repr. The Yellow Book, 3 (Oct 1894): 55. BnF, Paris

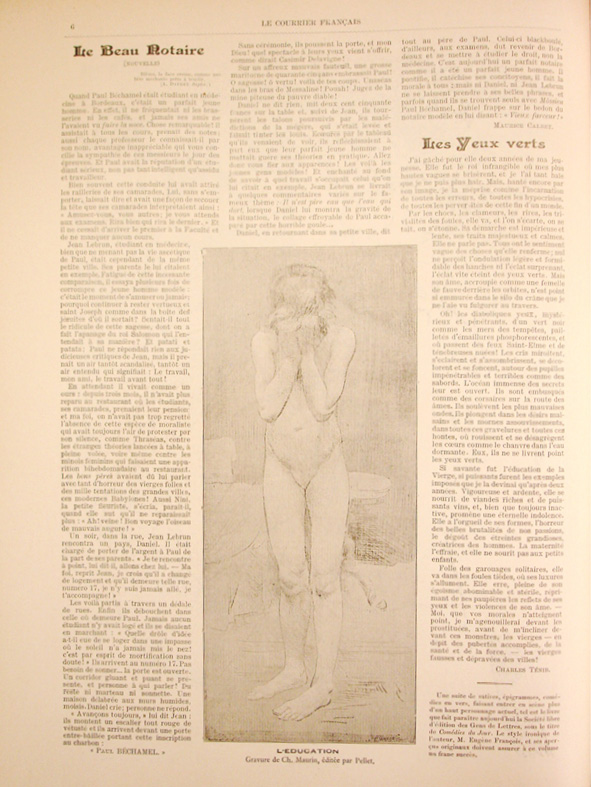

Fig. 5.4 Aubrey Beardsley, L’Éducation Sentimentale (ca. Feb–Mar 1894), The Yellow Book, 1 (16 April 1894): 55, repr. Le Courrier français, 6 (10 Feb 1895): 8. BnF, Paris

The British series in Le Courrier français came to an end, yet Beardsley’s drawings continued appearing. They ardently prolonged the provocation of the British establishment on an ethical and aesthetic level: L’Éducation Sentimentale, a drawing published in the first volume of the Yellow Book in April 1894 that re-appropriates the title of Flaubert’s novel to name a brothel scene (Zatlin 889a), had incited the Westminster Gazette to demand “a short Act of Parliament to make this kind of thing illegal.”20 Le Courrier français reprinted it on 10 February 1895 (Fig. 5.4).

A fortnight later, Roques’s magazine credited Beardsley with a portrait of Andrea Mantegna in the manner of the Flemish Primitives, which contrasted both with the designer’s graphic style and the periodical’s usual iconography.21 It corresponded to another polemic: Beardsley had published it in the third volume of the Yellow Book (Oct 1894), signing it with the pseudonym Philip Broughton (Zatlin 905). The English press had admired it, contrasting it with works by Aubrey Beardsley, an illustrator “who could not draw.” It was a good opportunity for the artist to reveal the hoax in England – a pleasure extended in France by attributing it to himself outright.

During this first phase, twenty Beardsley drawings, either in his new black-and-white manner or from Le Morte Darthur, ran through the pages of Le Courrier français over a six-month period, sometimes on a weekly basis. One of them, captioned Wagnériens et wagnériennes in the periodical (catalogued as The Wagnerites, see Fig. 5.3, Zatlin 908), was part of the Courrier français drawings sale on 18 February 1895 under the title “À une représentation de Tristan et Izeult.” It fetched the price of 150 francs, amongst the highest. In terms of drawings selected for the journal, much depended on Roques’s personal interests and taste. He approved of trestle theatre (two drawings from The Comedy-Ballet of Marionettes, as Performed by the Troupe of the Théâtre-Impossible) and privileged French subjects (two drawings of actress Réjane), but also piquant scenes such as Beardsley’s frontispiece for John Davidson’s novel Earl Lavender (Zatlin 944), a text inspired by Darwinian theories, which extols the virtues of flogging the weary souls of the time.

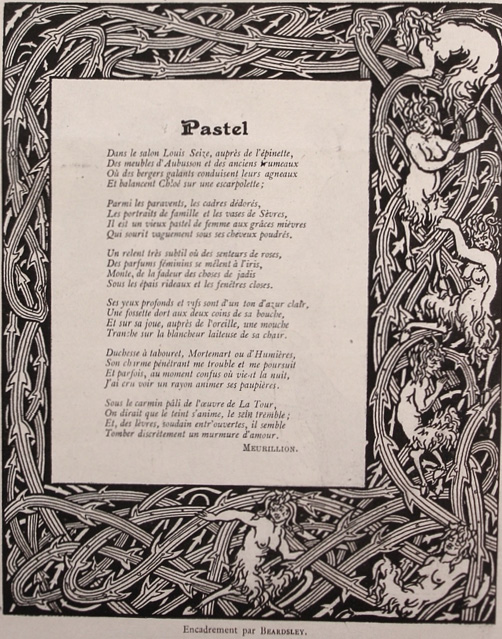

Fig. 5.5 Aubrey Beardsley, framing with she-fauns from Le Morte Darthur reused for Meurillion’s poem “Pastel,” Le Courrier français, 12 (24 Mar 1895): 8 (detail). BnF, Paris. The frame is Satyrs in Briars (autumn 1892), from Bk. II, chapter i

(Zatlin 371)

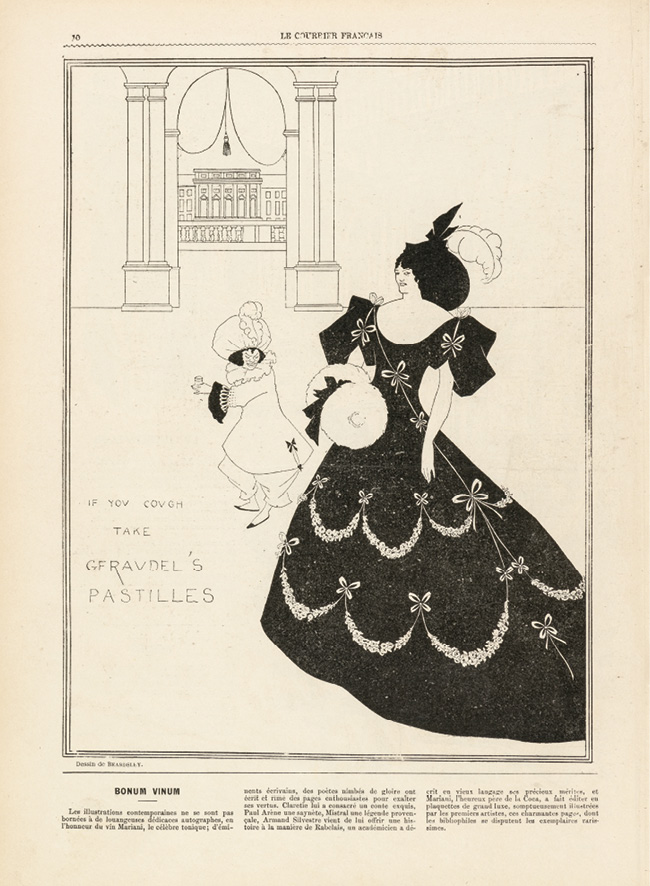

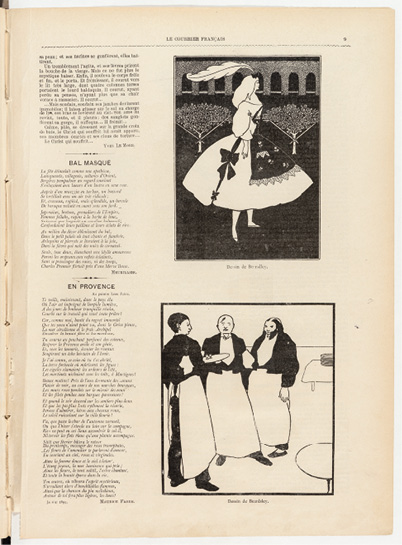

Roques exploited the drawings as he pleased, subjecting them to heavy-handed alterations and appropriating them into new contexts. A frame with female fauns in the 24 March 1895 issue, taken from Le Morte Darthur (Satyrs in Briars, Zatlin 371), hosts a Louis XVI “Pastel” signed Meurillion, an innocuous and obscure rhymer (Fig. 5.5). Another, on 14 April 1895, with a highly stylised cluster of grapes (Hop Flowers on Vines, Zatlin 666), houses a “Ballade du vieux buveur solitaire” by Émile Lutz. Lastly, on 17 February 1895, the first of the three Comedy-Ballet of Marionettes, as Performed by the Troupe of the Théâtre-Impossible, Posed in Three Drawings, changed into a poster (Zatlin 895), advertises the popular Géraudel cough tablets, the very raison d’être of Roques’s paper. Beardsley – who was more than willing for his work to be appropriated – had wonderfully adapted it to Roques’s commercialism. In the first Yellow Book version (Fig. 5.6), the dwarf holds a mask in his hand. In Le Courrier français, the mask becomes a round box of lozenges, while an added inscription states in Frenglish: “If You Cough Take Géraudel’s Pastilles” (Fig. 5.7).

Fig. 5.6 Aubrey Beardsley, The Comedy-Ballet of Marionettes, as Performed by the Troupe of the Théâtre-Impossible, Posed in Three Drawings, I (by 27 June 1894), repr. The Yellow Book, 2 (July 1894): 87. Courtesy Y90s

Fig. 5.7 Aubrey Beardsley, The Comedy-Ballet of Marionettes I, transformed into a billboard with the inscription “If you cough | take | Géraudel’s | pastilles,” Le Courrier français, 7 (17 Feb 1895): 10. BnF, Paris

Take offense? Why? The reproducibility and plasticity of Beardsley’s works, their adaptability, were part and parcel of an expansion strategy, deliberately deployed in France. This country Beardsley loved to visit because, as John Gray’s moving recollection put it after his demise, there one could see “si nettement.”22 It little mattered that Roques’s gazette often reproduced the drawings in quarter-page format, mingling them with a motley content, and with inking flaws that reproductions show. What mattered was that he published them. A strong aesthetic and ideological standpoint underpins this constraint-free use of images: to address the greatest number possible and educate the eye of the man in the street, as Beardsley’s manifesto on the modern poster claimed.23 Such reuse takes advantage of the forms’ malleability in a press itself pliable and highly plastic. A case in point is the regular Beardsley spoofs in Punch. By parodying the artist, they propagated the “Beardsley style” and amplified it.24 For an artistic personality such as Beardsley’s, which changed styles with a speed rarely seen, and quickly turned every lit straw into a bonfire, such open-mindedness, if not open incitement, was crucial.

Adaptable, critical, and probably involving the draughtsman himself, the Courrier français reproduction of Beardsley’s work was exceptional, and in terms of its flexibility and scope, outshone Beardsley’s controlled presence in the British press. Roques’s presentation of Beardsley was not devoid of blunders. He misconstrued an allusion by Beardsley to the novel he planned to write based on Wagner’s Tannhäuser, and read Walter Sickert’s signature on the artist’s portrait as “sickest” (“très malade”), attributing the piece to Beardsley himself.25 Later on, Franz Blei and Carl Sternheim’s Hyperion would repeat the slip-up and publish this portrait as a work by Beardsley, made in Paris for Le Courrier français, which proves the pull of the Montmartre weekly to Viennese and German aesthetic circles.26 The Russian Mir iskusstva reproduced the gaffe yet again.27

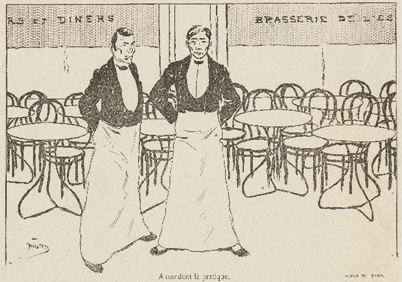

Fig. 5.8 Charles Huard, En attendant la pratique (Waiting for the client), repr.

Le Courrier français, 10 (8 Mar 1896): 2 (detail). BnF, Paris

Fig. 5.9 Aubrey Beardsley, Garçons de Café (by June 1894), repr. The Yellow Book, 2 (July 1894): 93, catalogued as Les Garçons du Café Royal, repr. Le Courrier français, 6 (10 Feb 1895): 9. Above, reproduction of Beardsley, The Slippers of Cinderella (by 27 June 1894), MSL coll., Delaware, repr. The Yellow Book 2 (July 1894): 95 (Zatlin 899). BnF, Paris

Fig. 5.10 Charles Maurin, Untitled plate from the series L’Éducation sentimentale (Gustave Pellet, 1896) repr. as L’Éducation, Le Courrier français, 23 (7 June 1896): 6. BnF, Paris

Still, Le Courrier français acted as a French podium and a mirror. Thanks to it, Beardsley influenced a number of French artists: Charles Huard’s drawing En attendant la pratique (Fig. 5.8) was surely inspired by Beardsley’s Les Garçons du Café Royal (Zatlin 898), published in the second volume of the Yellow Book as Garçons de Café (Fig. 5.9). L’Éducation sentimentale by Charles Maurin, a set of coloured etchings and dry-points issued by Gustave Pellet in 1896 with plates detailed in Le Courrier français, may have borrowed the idea of the title and the feminisation of the subject from Beardsley. In Beardsley’s drawing, an old madam is educating a lewd young girl (see Fig. 5.4). In Maurin’s, a young woman grooms a little girl, in delicate nudity, foregrounded in “a very remarkable sensual atmosphere.”28 In two of these engravings, the mother figure has disappeared. The print in which the naked child stands, her face hidden in her hands in an attitude of deep sorrow (Fig. 5.10a–b), has a rather blatant meaning in a journal in which painters like Adolphe Willette and Jean-Louis Forain overtly criticised the abuse of girls.29 Yet Beardsley himself may have been inspired by continental artists, and Jacques Lethève has related his Wagnerites and Garçons du Café Royal to wood engravings by Félix Vallotton.30

Periodical Networking: Le Courrier français and the Savoy

Transfers, circulation of images, and extensive use of media formed the basis of the artist’s strategy for self-promotion. As we saw in the previous chapter, reproductions of Beardsley’s work challenge the supposedly watertight partition between large-circulation periodicals and art and literature reviews. The artificial divide is likely based more on the presumptions and constructs of literary history than on reality. This is certainly the case in France. From February 1896, Roques’s weekly became the outlet for the Savoy, the aesthete art and literature journal, newly founded in London with Beardsley as art editor and Arthur Symons as literary editor. Once the Savoy had been introduced,31 Le Courrier français regularly announced its contents and reproduced drawings, including those by Beardsley. A prose poem by Lautrec bears the inscription “Pour mon ami Aubrey Beardsley” as a tribute.32 Shipments to Lautrec from Leonard Smithers, Beardsley’s and the Savoy’s new publisher, were regular.33

One might be tempted to think that the bold drawings and spicy literature favoured by Roques reflected a bond with Smithers, notorious for his collection of erotica and books traded under the counter, disparaged by a conservative Britain, and known for having once displayed in his window the provocative notice “Smut is cheap today.” Yet the artist’s choice of both Roques and Smithers guaranteed above all freedom of expression. Rejected by John Lane, the rising and cautious Yellow Book publisher, Beardsley had readily been sponsored by Smithers. James G. Nelson’s fine study has shown the central role Smithers played in promoting the avant-garde in prudish Britain.34 Similarly, despite his opportunism, Roques was a patron of the avant-garde and a virtuoso of cultural networks.

As it happened, there was nothing particularly objectionable or controversial about Beardsley’s drawings in Le Courrier français during his second phase of involvement. They were representative of his most beautiful and fine graphic style, the plates for Pope’s heroic-comic masterpiece The Rape of the Lock. In May 1896, Lautrec gave the first French description of this book he had just received,35 and which he may have lent to Jarry. “Du pays des dentelles,” Jarry’s splendid text inspired by Beardsley’s plates after Pope, was published two years later in the Mercure de France. A central drawing in this series, Le Rapt de la boucle, an accurate translation of The Rape of the Lock (Zatlin 982), featured in Le Courrier français (Fig. 5.11), as did several other pieces: the cover of the first issue of the Savoy; Beardsley’s mischievous self-portrait A Footnote (see Fig. 3.4); the drawing L’Ascension de Sainte Rose de Lima (The Ascension of Saint Rose of Lima, Zatlin 1005), taken from the first version of Beardsley’s unfinished novel Under the Hill, published in instalments in the English magazine; and the plate The Coiffing (Zatlin 1009) accompanying Beardsley’s poem “The Ballad of a Barber.”36

Fig. 5.11 Aubrey Beardsley, Le Rapt de la boucle [The Rape of the Lock (by late Feb 1896), priv. coll., New York (Zatlin 982)], repr. Le Courrier français, 22 (31 May 1896): 6. BnF, Paris

It was therefore not avant-garde art and literature reviews that welcomed Beardsley in France, as one might have expected, but a weekly of broad circulation and dubious reputation, promoting graphic innovation. If Beardsley’s own periodicals, the Yellow Book and the Savoy, welcomed and publicised modern art and literature, as did their French peers, the correspondence one might have expected between them is not confirmed. Media promotion was the keyword, and both Roques and Beardsley benefited from it in turn. Additionally, Le Courrier français also enabled Beardsley to feature alongside those who practised an art as demanding, innovative and disruptive as his own in France: Adolphe Willette, Jean-Louis Forain, Félix Vallotton, Jules Chéret, Armand Rassenfosse, Louis Legrand, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec for a time, as well as the American Will Bradley.

Baffling Associations

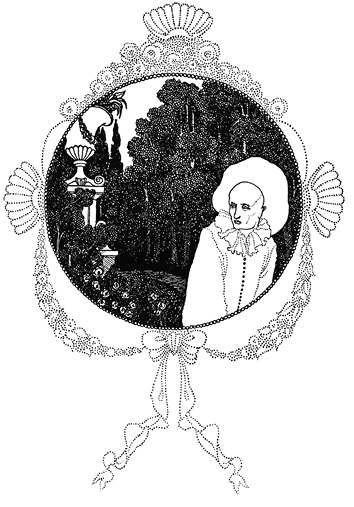

From a present-day standpoint, it might be assumed that French avant-garde journals would have followed Le Courrier français and discussed Beardsley’s art much earlier. Yet, only in April 1897 did L’Ermitage grant him an article in his lifetime, three years after Le Courrier français, thanks to Henry-D. Davray.37 A key translator of English texts, Davray wrote influentially in the Mercure de France on British literature, and spent time with Beardsley, whom he trained in oral French. An exclusive publication, L’Ermitage was in that phase open to Anglophone input (maybe encouraged by Stuart Merrill and Francis Vielé-Griffin, two Franco-American authors on its editorial team) and to images (under the artistic leadership of Jacques Des Gachons). In his Ermitage article on Beardsley, Davray himself aspired to comprehensive criticism, far from the hubbub, judging and defending a work of art because it is admirable though it may not please all. His efforts at completeness drew on a recent publication, Beardsley’s album A Book of Fifty Drawings (issued by Smithers), which made gauging the artist’s diverse styles possible. Davray’s article included a single illustration, highlighted as a full-page plate, the openwork medallion concluding Ernest Dowson’s The Pierrot of the Minute (Fig. 5.12, Zatlin 1043), on which Davray also commented in the Mercure de France.38 Further exchanges with Davray show Beardsley’s strong desire to participate in the illustrated edition of L’Ermitage in 1898.39 His death prevented him from so doing.

Fig. 5.12 Aubrey Beardsley, Cul-de-lampe (12–16 Nov 1896), Lessing J. Rosenwald coll., Library of Congress, Washington, DC, repr. as final plate in Pierrot of the Minute, 44. PE coll.

In the meantime, the artist had contributed to the Salon des Cent organised by yet another avant-garde review, La Plume, and several of his posters had appeared in a Plume special issue on this new art form that had launched a craze.40 As shows a 13 August 1893 autograph receipt signed by Edward Bella,41 he had made a colour cover for La Plume, which was never published.42 Several French books in a variety of genres had mentioned him. Gabriel Mourey, the correspondent and manager-to-be of the Studio in France (from 1899), introduced him in Passé le détroit, his promenade on new art discoveries beyond the Channel.43 Jean Lorrain mentioned him in his Parisian chronicles: commenting on the Parisian staging of Wilde’s Salomé, he acclaims no other décor and costume designer than Beardsley, Wilde’s “designated illustrator.”44 Following a Lautrec quote, Lorrain stressed the artist’s “frail and tormented grace, the light and sometimes caricatural sensuality.”45 Octave Uzanne, who had met Beardsley three years earlier in London, commended him in Les Évolutions du bouquin, reproduced three drawings (praising the controversial Comedy of Sighs! poster, see Fig. 4.2), and announced a promising future.46 Keen on new book genres and book design, he further introduced Beardsley in L’Art dans la décoration extérieure des livres with five covers and book bindings reproduced either in-text or as inserted plates.47

Unlike the Italian articles discussed in the previous chapter, which often included all sorts of biographical information at the expense of Beardsley’s art – with ruminations on the British education system –, none of these numerous mentions in the French press offered witty or troubling comments on the artist’s life. Except for a few sparse allusions to his youth, comments focused on his art accomplishments. Art criticism prevailed in France, unlike in Italy, where personal data was mixed with limited comments on the art and rumour harvested from other magazines (although French newspapers were not above reporting scandalous anecdotes). It was only on Beardsley’s death that French obituaries and posthumous celebrations led to a motley concert of biographical articles.

Tribute and Din

Obituaries are a tricky business. Two obituaries, closely following on Beardsley’s demise that I discovered in the press and ascribed to their authors, were by men of taste who knew the artist well. The artist Jacques-Émile Blanche (only signing by his initials), who had painted a splendid 1895 portrait of Beardsley, penned the first in the supplement of La Gazette des beaux-arts.48 Octave Uzanne, under the pseudonym Isis, contributed the second on the front page of Le Figaro, a widely distributed daily.49 Curiously, their thoughtful tributes were offset by a racist anecdote on the front page of the Journal des débats a fortnight later: a poster by Beardsley is bought at a low price by an American, who then offers it to another as a specimen of modern art. Although this man takes the poster, he despises it, and uses it to wrap his dirty linen to take to the laundrette. The Chinese laundryman discovers the poster, marvels at it, hangs it up and has it admired. From one buyer to the next, its price rises to 500 dollars (2,500 francs). It ends up in the home of a wealthy Chinese gentleman in San Francisco, above an altar where a lamp burns night and day. “New prospects open up for misunderstood artists,” concludes dryly the (unsigned) article.50 Less than a month after the artist’s demise, such a yarn sounds so inappropriate that neither prudery nor narrow-mindedness exonerates it. The conventional French press had a field day over it, propagating it from one paper to the next.51 The din went on, mocking the work in the absence of the self-jeering artist.

The anecdote had reached the French press from the British dailies and must be apocryphal. First published in the Westminster Gazette in August 1894, amid the Beardsley boom, it was repeated there on 17 March 1898, and relayed by the Daily Mail two days after the artist’s death.52 Its coarseness speaks volumes of the principles guiding press journalism at the time. Beardsley’s oeuvre may have taken advantage of the uproar of outrage. Outrage turned against him at his departure. It took a year for the Journal des débats, and the publication of a new book of his drawings, to concede a fairer article to Beardsley, likened to Pierrot, “gay, mocking, suffering, doomed to die young.”53 The image springs from the work itself by way of the avant-garde journals. And it looks at an impressive future ahead albeit its meaning.

Pierrot Beside Himself: Exit Scenarios

The Mercure de France and La Revue blanche commemorated Beardsley in unison. The Mercure had announced Beardsley’s passing already in April in a dense unsigned paragraph recalling the most important phases of his style.54 The May 1898 Mercure issue turned to a plural tribute: Davray translated Wilde’s “Ballad of Reading Gaol,” by then in its sixth printing, whose poignant stanzas struck a melancholic chord, while Jarry published “Du pays des dentelles” celebrating Beardsley’s last ajouré style after The Rape of the Lock, under the aegis of his Faustroll texts.55 Davray’s article on Beardsley was the issue’s major accolade, drafting the artist’s intellectual portrait.56 It was not illustrated but turned out to be almost as good as any illustration at proffering a poignant image of the artist’s passing. Davray opened it and closed it in English and in italics, using at the opening Beardsley’s full-length caption to The Death of Pierrot from the October 1896 Savoy (Zatlin 1015), and a few fragments of the same in his final words:

As the dawn broke, Pierrot fell into his last sleep. Then upon tiptoe, silently up the stair, noiselessly into the room, came the comedians Arlecchino, Pantaleone, il Dottore, and Colombina, who with much love carried away upon their shoulders, the white frocked clown of Bergamo; whither, we know not.57

Both the caption and the absent plate staged the artist’s exit, forlorn in his ultimate bunk, miles away from the cheek and vivacity of his mischievous portraits. Misfortune would have it that such a melodramatic curtain was at complete odds with the artist’s own intentions, even though he had multiplied his Pierrot self-portraits from the very beginning. An early identification of the artist as the white-faced pining clown, in which Decadence saw the image of the poet, featured in an August 1893 letter to Robert Ross. Beardsley asked him for a prologue in verse for a projected book, Masques, which never materialised. It would have been spoken by Pierrot, i.e., himself.58 A serious health crisis in 1896 surely encouraged the affinity. Yet Beardsley had clear reservations about associating himself with the potentially facile and overly maudlin image of Pierrot. He had deferred publishing The Death of Pierrot in the Savoy, unwilling for it to feature as an epitaph.59 He would have been “seriously distressed” to see it published on its own, without any other accompanying drawings. It would have looked, he admitted to Smithers, like a confession of helplessness and illness.60

The zeitgeist, however, worked against him: Pierrot’s enigmatic sadness and loneliness had grown hugely popular both in England and in France.61 In 1896, Lane published a series of four novels, “Pierrot’s Library,” with all volumes in identical front, back, and spine designs (but different colour by volume), title pages, front and back endpapers conceived by Beardsley (Zatlin 958–62). In 1897, Beardsley also designed the binding, ornaments, and plates for Ernest Dowson’s melancholy fantasy, The Pierrot of the Minute issued by Smithers (Zatlin, 1040–43). The Cul-de-lampe for this shows a sad, aged Pierrot leaving a lush garden, the oval-shaped medallion set in an elaborate ajouré frame of garlands and roses with a mirror effect (see Fig. 5.12, Zatlin 1043). The Cul-de-lampe was no tailpiece but an ostentatious final image, a decorative oculus through which Pierrot looked back at the entire text itself.62 Davray had publicised it in France as an openwork ornament set within his Ermitage article on Beardsley, the only text on the English artist to appear in a French avant-garde journal in his lifetime. A nearly blank page introduced it, bearing only its new title in French, Le Pierrot d’aujourd’hui (The Pierrot of Today).63 White became Pierrot and blank announced his impending silence. Such an arrangement set the tone for Beardsley’s farewell chorus. Davray’s article in the Mercure de France did the rest.

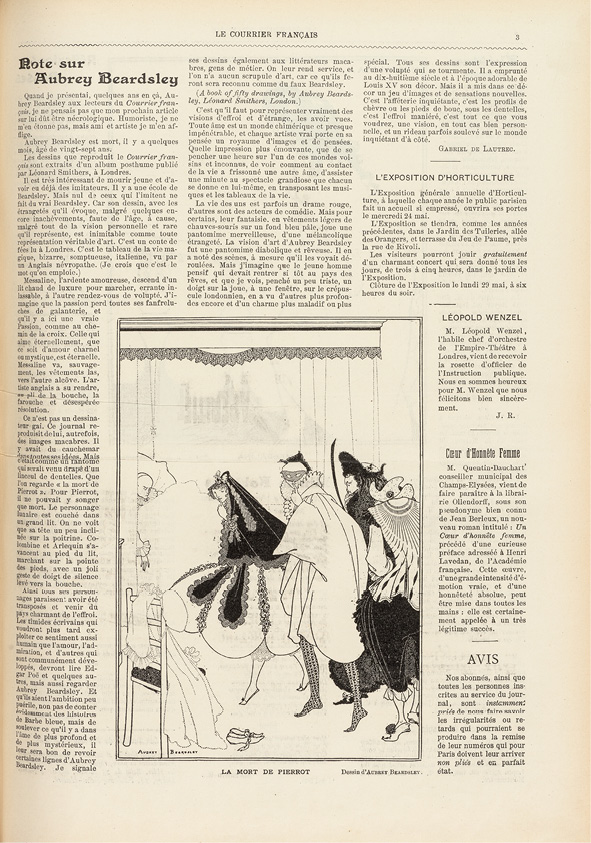

With the help of the French press, The Death of Pierrot ended up becoming an inadvertent self-portrait and one of Beardsley’s most iconic images. The drawing depicts several commedia dell’arte characters tiptoeing towards Pierrot on his deathbed, a finger against their lips (Fig. 5.13, Zatlin 1015). Pathos is at its highest but, nevertheless, impertinence is still present. The scrawny figure of Pierrot, lost under a swelling bedspread and an oversized bed, is the ultimate version of Portrait of Himself (see Fig. 3.3) minus the mischief. Fletcher notes “a bulging forehead that suggests the fetus image […] with a bandage for headdress round the sharp contoured features of the dead face.”64 Half of the figures beckon at an audience: the unseen spectators, and ourselves, the viewers. Death has become a performance enacted on a stage-like podium. The imaginative dimension of the drawing makes art even out of ultimate demise.

Fig. 5.13 Aubrey Beardsley, La Mort de Pierrot [The Death of Pierrot (by first week of July 1896), repr. The Savoy, 6 (Oct 1896): 33], here illustrating Gabriel de Lautrec’s belated article, “Note sur Aubrey Beardsley,” repr. Le Courrier français, 21 (21 May 1899): 3. BnF, Paris

Critics adored the stage-like quality of the piece, and claimed it as an ideal dénouement. Exploited to accompany many posthumous articles, it turned into a pathetic – and influential – symbol of the artist’s early passing. Le Courrier français published it in 1899 with a Lautrec article (see Fig. 5.13), a tribute quite belatedly paid to the man who had much contributed to Roques’s fortunes.65 So did Emporium in 1904 under Vittorio Pica’s seal.66 As for Kunst und Künstler, in 1903 it replicated the Dowson ajouré Pierrot as a final image, this time a real tailpiece concluding Emil Hannover’s article.67 In their wake, Julius Meier-Graefe’s study on Beardsley became an explicit farewell. It adopted as motto Beardsley’s translation of Catullus’s Latin farewell68 and concluded with two Pierrot pictures, the Dowson Cul-de-Lampe and The Death of Pierrot, the latter, again detailed and dramatised in words.69 The drama had been played out. Text and pictures grieved.

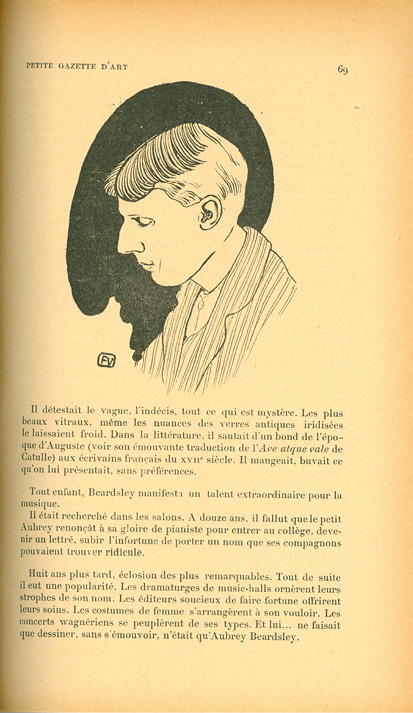

A similar mood prevailed in La Revue blanche. In a touching article, written and published in French on 1 May 1898, probably supervised by Félix Fénéon,70 John Gray, a close friend of Beardsley’s, called Pierrot “a sad biography” (“une triste biographie”). Additionally, Gray’s opening sentence, “An artist has just died,” echoed “M. Gustave Moreau has just died.” Moreau had passed away on 19 April, following Beardsley. The first chronicle and its initial line, a tribute to the French artist, heralded the last, a homage to the British, under the common heading “Petite gazette d’art.” Thadée Natanson, who had signed most of its entries, must have been no stranger to such an arrangement.71 La Revue blanche thus expressed its dedication to two artists of stature, Gray’s contribution being yet another shilling paid into the coffers of Franco-British friendship. Ironically, Moreau had shunned the public and eschewed clamour, quite the contrary to Beardsley.

Both the Mercure and La Revue blanche tempered, however, the pathos of that adieu. The Mercure article closes with a grotesque tailpiece by Joseph Sattler, who pictured a fancy grimacing Beardsley with faun’s ears, ironically haloed with a crown adorned by a single laurel leaf (Fig. 5.14). In La Revue blanche, Beardsley’s portrait by Vallotton, a black-and-white “mask,” stands out against a black patch, a dripping ink blot that redrafts his profile in caricature (Fig. 5.15): the melancholic tribute is tempered by the grotesque in response to the artist who had stated that, if he was not grotesque, he was nothing.

Fig. 5.14 Joseph Sattler, Grotesque of Aubrey Beardsley, tailpiece of Henry-D. Davray’s article, “Aubrey Beardsley,” repr. Mercure de France, 26:101 (May 1898): 491. Author’s photograph

Fig. 5.15 Félix Vallotton, Aubrey Beardsley’s mask, with John Gray’s article in “Petite gazette d’art,” repr. La Revue blanche, 16 (May 1898): 69. Author’s photograph

It is therefore halfway between the white Pierrot and the grotesque vignettes that Beardsley’s portrait as “dandy of the grotesque”72 finally took shape in French and European periodicals. The white frock is but an evanescent bust. Yet a bust all the same. Witness Matthew Sturgis’s Beardsley biography, which chooses no other image and no other heading to conclude. His last chapter is “The Death of Pierrot,” and it uses the homonymous plate as chapter frontispiece.73 Yet, Pierrot’s loose white blouse and wide white pantaloons are perhaps nothing more than an ultimate mask enclosing nothing, a blank surface on which commiseration and pathos may glide and thrive. It brought the wide circulation of images of the “puerile” Beardsley to a stop, in obvious contradiction to an icon status long shaped by an aura of scandal and clever wit.

French Aftermath and Follow-Up

Two tributes in larger circulation periodicals addressed the general public at the time of Beardsley’s death: Gabriel Mourey gave an overall approving evaluation of Beardsley’s art, admiring his precociousness, in La Revue encyclopédique;74 and Tristan Klingsor added a more descriptive piece in the Revue illustrée.75 It was not until July 1899 that Davray wrote an “epitaph” in La Plume, echoing several English authors, and listing the print runs of the albums and the retail prices of several illustrated books.76

All the same, these articles signal a missed rendezvous. More often than not, the same facts and features about Beardsley passed from one author to the next, embellished with a few descriptions after reproduced drawings. The avant-garde reviews remained soberly illustrated. In these publications it was the work’s originality and its boldness that moulded the words. The larger-circulation magazines had significant financial means, which the avant-garde journals could not compete with, so it was up to publications like the Revue illustrée, to provide reproductions of fine drawings requested from London. In this way, Beardsley’s images reached a wider public through popular, general-interest magazines, guided by his legendary reputation. As Desmarais shows in her comparison of Beardsley’s reception in England and France, the French often stressed deformation, grotesqueness and perversity in their treatment of Beardsley.77 A Robert de Montesquiou article, based on A Book of Fifty Drawings and A Second Book of Fifty Drawings is titled “Le Pervers,”78 even though Montesquiou had no access to Beardsley’s erotic work.

The beginning of the twentieth century extended this trend: Beardsley’s work was troubling and potentially embarrassing, yet interest in it was still growing. His legend still held but was also receding in knowledgeable publications. Arthur Symons’s book, one of the most thorough studies of Beardsley’s art at the time, republished in 1905, was translated into French in 1906.79 In February 1907, the Shirleys gallery, at 9 Boulevard des Malesherbes, organised a major exhibition of original drawings. Attendance was so large that it was extended by a week. On this occasion, an unexpurgated version of the Salome drawings was published in book form, as was the French translation of Beardsley’s incomplete novel, Under the Hill. Robert de Montesquiou reviewed the exhibition on the front page of Le Figaro, describing Beardsley’s line as “traced on a mirror with the edge of a diamond.”80 Jacques-Émile Blanche lengthily recorded his memories in the journal Antée and as a preface to the Paris and Bruges editions of Under the Hill.81

In 1907, the theatre manager Gabriel Astruc organised a grand production of Richard Strauss’s Salome in its German version, with Strauss himself on the podium and Natalia Trouhanova and Aïda Bini alternating in the dance of the seven veils.82 The press was again aflame with articles on Wilde and Beardsley. Despite this popularity, proper academic evaluation of the artist was slow to emerge. Armand Dayot’s assessment in La Peinture anglaise in 1908 stands out from the crowd by concluding with the Lysistrata erotic drawings as the artist’s masterpiece of synthesis.83 This is more than unusual. However, still in the 1930s, a nostalgic view again emerged in an article by Edmond Jaloux for the newspaper Le Temps, on the occasion of another demise, that of Ellen Beardsley, the artist’s mother, who had passed away in poverty.84

The French record is thus in keeping with what Roques had predicted in December 1894: “He will be excessively disparaged by some, frankly admired by others; he will be indifferent to no one.”85 This is apposite. The artist’s choice of Le Courrier français was a lucky one when compared to other avant-garde reviews, which were moved by his death, but visually coy. Subscribers to L’Ermitage were estimated at 400 at best. Le Courrier français, for its part, may have run to 25,000 to 30,000 copies at its heyday between 1891 and 1896. Its fame, its distribution in the provinces and abroad, its longevity, its large number of illustrations, and the part it played in artistic life make it the “most important and most representative” paper of the nineteenth century’s last decade.86 All in all, the comparison shows, despite Beardsley’s praise, a certain reserve and distance of the avant-garde journals regarding his radical graphic design, only imperfectly rendered by words. The divergence points to an antagonism between what appeals to the eye and what compels the intellect. Such is the paradox of Beardsley’s ultimately intellectual art: to have imposed itself only through its own graphic form and the myths he himself fostered.

1 John Gray, “Petite gazette d’art: Aubrey Beardsley,” La Revue blanche, 14 (May 1898): 68.

2 On this less known aspect of Puvis de Chavannes’s work, see Les Caricatures de Puvis de Chavannes, préface de Marcelle Adam (Paris: C. Delagrave, 1906).

3 Joseph Pennell, “A New Illustrator: Aubrey Beardsley,” The Studio, 1:1 (15 Apr 1893): 14–19, reproduced 19 (full page). On Pennell’s article, see Chapter 4.

4 Jacques-Émile Blanche, “Aubrey Beardsley,” Antée: Revue mensuelle de littérature, 3:11 (1 Apr 1907): 1106; Blanche, Propos de peintre. De David à Degas, 1e série (Paris: Émile-Paul Frères, 1919), 113.

5 Julius Meier-Graefe, “Aubrey Beardsley and his Circle,” in Modern Art: Being a Contribution to a New System of Aesthetics, trans. by Florence Simmonds and George W. Chrystal, 2 vols. (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons; London: William Heinemann, 1908), II, 253.

6 Jacques Lethève, “Aubrey Beardsley et la France,” Gazette des beaux-arts, 68:1175 (Dec 1966): 343–50.

7 Jane Haville Desmarais, The Beardsley Industry: The Critical Reception in England and France, 1893–1914 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998), 34–35, 46–48, 56–57.

8 Un Book-Trotter, “L’Image: Titres réduits des nouveaux périodiques anglais,” Le Livre et l’Image, 2:6 (Aug 1893): 57: “un jeune artiste de 20 ans, actuellement à Paris […].”

9 Pastel [Theodore Wratislaw], “Some Drawings by Aubrey Beardsley,” The Artist and Journal of Home Culture, 14 (1 Sept 1893): 259.

10 See Laurent Bihl, “Jules Roques (1850–1909) et Le Courrier français,” Histoires littéraires, 12:45 (Jan–Feb–Mar 2011): 43–68; and Bihl, “Le Courrier français,” Ridiculosa, special issue “Les revues satiriques françaises” (18 Nov 2011): 146–49.

11 Marcel Schwob, Correspondance inédite précédée de quelques textes inédits, ed. by John Alden Green (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1985), 72.

12 Blanche, Propos de peintre, 113: “collabora.” The first version, in the Bruges review Antée, 3:11 (1 Apr 1907): 1106, reads “with which he collaborated a little and in which he met with success right away” (“auquel il collabora un peu et où il réussit du premier coup”).

13 Jules Roques, “Une exposition d’affiches artistiques à l’‘Aquarium’,” Le Courrier français, 45 (11 Nov 1894): 2–5.

14 See Linda Gertner Zatlin, Aubrey Beardsley: A Catalogue Raisonné, 2 vols. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2016), II, 142 and 144.

15 Ibid., 9.

16 See Aubrey Beardsley, Under the Hill, and Other Essays in Prose and Verse (London and New York: John Lane, 1904), 70.

18 Le Courrier français presents them in the following order: Phil May on 18 Nov 1894, Dudley Hardy on 25 Nov, Chantrey Corbould on 2 Dec, Eckhardt on 9 Dec, Fred Pegram on 16 Dec, Beardsley on 23 Dec, J. W. T. Manuel on 30 Dec, Leonard Raven-Hill on 6 Jan 1895 (this issue also contains an invitation to exhibit, addressed by the Chelsea Arts Club artists to their French colleagues), A. S. Hartrick on 13 Jan, F. H. Townsend on 20 Jan, Edmond Sullivan on 27 Jan, Maurice Greiffenhagen on 3 Feb.

19 Roques, “Courrier de Londres,” Le Courrier français, 44 (4 Nov 1894): 4a, “les plus artistes bien entendu, quelque chose comme l’équivalent de MM. Forain, Willette, Chéret, Legrand, Lunel, Anquetin, Grasset, L. O. Merson, Pille, Hermann Paul, Renouard, Raffaëlli etc.”

20 See preface by John Lane, in Beardsley, Under the Hill, vi; and Zatlin, Catalogue Raisonné, II, 79.

21 Le Courrier français, 8 (24 Feb 1895): 3 (reproduction).

22 Gray, “Aubrey Beardsley,” 68.

23 Beardsley, “The Art of the Hoarding,” The New Review, 11 (July 1894): 53–55, collected in A. E. Gallatin, Aubrey Beardsley: Catalogue of Drawings and Bibliography (New York: The Grolier Club, 1945), 110–11, and in Decadent Writings of Aubrey Beardsley, ed. by Sasha Dovzhyk and Simon Wilson, MHRA Critical Texts 10, Jewelled Tortoise 78 (Cambridge: Modern Humanities Research Association, 2022), 188–89.

25 Roques, “Les artistes anglais: M. Beardsley,” 8. Sickert’s portrait of Beardsley, a sketch, is signed above right. The caption however reads: “Aubrey Beardsley, by himself” (“Aubrey Beardsley, par lui-même”).

26 See Selbstbildnis von Aubrey Beardsley aus dem Jahre 1894, Hyperion: Eine Zweimontasschrift, 2 (1908), last plate but one with the indication: “in Paris gezeichnet für den ‘Courier français’ [sic].”

O. Mek Koll’, “Obri Berdslei,” Mir iskusstva, 3:7–8 (1900): 84 (in Russian, without mentioning Le Courrier français).

28 Charles Maurin, un symboliste du réel, textes de Maurice Fréchuret, ed. by Gilles Grandjean (Lyon: Fage éditions; Le Puy-en-Velay: Musée Crozatier, 2006), 79: “une atmosphère sensuelle très remarquable.” The print has sometimes be arbitrarily named La Pudeur (Bashfulness).

29 A lovely print of the original etching and drypoint with different coloured inks on pale green coloured paper may be seen here: https://www.navigart.fr/MAMC-saint-etienne-collections/artwork/charles-maurin-petite-fille-debout-nue-le-visage-cache-dans-les-mains-240000000005197

30 Lethève, “Aubrey Beardsley et la France,” 347, fig. 5.

31 Gabriel de Lautrec, “Une nouvelle revue,” Le Courrier français, 5 (2 Feb 1896): 8–9.

32 Lautrec, “Pour un Démon,” Le Courrier français, 7 (14 Feb 1897): 6.

33 The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, ed. by Henry Maas, J. L. Duncan, and W. G. Good (London: Cassell, 1970), 231, letter dated 22 Dec 1896 to Smithers: “You generally send him [G. de Lautrec] (on account of the Courrier Français) a copy of my books.”

34 See James G. Nelson, Publisher to the Decadents: Leonard Smithers in the Careers of Beardsley, Wilde, Dowson (University Park, Penn.: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000).

35 Lautrec, “Envois de Londres,” Le Courrier français, 22 (31 May 1896): 5–6.

36 Le Courrier français, 5 (2 Feb 1896): 9 (cover of the Savoy, no. 1); 20 (10 May 1896): 9 (A Footnote); 22 (31 May 1896): 5 (The Ascension of Saint Rose of Lima) and 6 (The Rape of the Lock); 27 (5 July 1896): 11 (The Ballad of a Barber, taken from the July issue of the Savoy, reproduced without the poem).

37 Henry-D. Davray, “L’Art d’Aubrey Beardsley,” L’Ermitage, 14 (Apr 1897): 253–61.

38 Davray, “Lettres anglaises,” Mercure de France, 22:90 (June 1897): 582.

39 The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, 419 (letter dated 7 Jan 1898): “Certainly I shall be only too pleased to let you have something for the new Ermitage.”

40 “Les affiches étrangères,” La Plume, 155 (1 Oct 1895): 410 (Affiche anglaise pour la galerie Goupil, à Londres), 424 (Affiche pour la Librairie Children’s book [sic]); “L’Affiche anglaise,” ibid., 428 (Affiche “Autonym” pour une librairie); “Supplément,” 457 (affiche pour A Comedy of Sighs!), 459 (Affiche anglaise). Several of these will find their way into Uzanne’s Les Évolutions du bouquin.

41 Edward Bella owned with his brother the paper firm “J. & E. Bella.” He was a poster enthusiast, organiser of poster exhibitions, and the London correspondent for La Plume’s Salon des Cent. Further on Bella, see Philipp Leu, “Les revues littéraires et artistiques, 1890–1900. Questions de patrimonialisation et de numérisation,” 2 vols. (PhD diss., Université Paris-Saclay, 2016), I, 103, n. 257, https://theses.hal.science/tel-03606156, and Zatlin, Catalogue Raisonné, II, 185, 191 and 194.

42 The Gallatin Beardsley Collection in the Princeton University Library. A Catalogue Compiled by A. E. Gallatin and Alexander D. Wainwright (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Library, 1952), 18.

43 Gabriel Mourey, “Quelques-uns et leurs œuvres: Aubrey Beardsley,” in Mourey, Passé le détroit: La Vie et l’art à Londres (Paris: Paul Ollendorff, 1895), 268–71.

44 Jean Lorrain, “Pall-Mall semaine,” Le Journal (16 Feb 1896): 2: “l’illustrateur désigné pour les œuvres de Wilde.”

45 Ibid.: “la grâce frêle et tourmentée, la sensualité légère et parfois caricaturale.” See also Lorrain, Poussières de Paris (Paris: Fayard frères, 1896), 150. Lorrain would also comment on Beardsley in Poussières de Paris (Paris: Paul Ollendorff, 1902), 100, reproducing “Pall-Mall Semaine,” Le Journal (25 June 1899).

46 Octave Uzanne, Les Évolutions du Bouquin. La Nouvelle Bibliopolis: Voyage d’un novateur au pays des néo-icono-bibliomanes, lithographies en couleurs et marges décoratives par H. P. Dillon (Paris: Henri Floury, 1897), 41, 148, 151, 154, 161, 170, with four reproductions (two of which posters). See https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k8560074/f11.planchecontact

47 Uzanne, L’Art dans la décoration extérieure des livres en France et à l’étranger, les couvertures illustrées, les cartonnages d’éditeurs, la reliure d’art (Paris: Société Française d’Éditions d’Art, L. Henry May, 1898), 105 (cover for the Savoy), 108–109, 113, 147 (spine and front cover for Le Morte Darthur), 151 (binding for A Book of Fifty Drawings); insert plates between 96–97 (faun reading to a young lady), 104–105 (title page for the Savoy), 152–53 (blue printed boards on blue cloth for Pierrot! by H. de Vere Stacpoole). See https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k96299956/f8.planchecontact

48 J.-E. B., “Aubrey Beardsley,” La Chronique des arts et de la curiosité. Supplément à la Gazette des beaux-arts, 13 (26 Mar 1898): 111.

49 Isis [Octave Uzanne], “Paris partout,” Le Figaro, 89 (30 Mar 1898): 1. Attributed thanks to La Cagoule. Octave Uzanne, Visions de notre heure. Choses et gens qui passent, notations d’art, de littérature et de vie pittoresque (Paris: Henri Floury, 1899), 95–97, same text. Most of the chronicles included in this book were published in L’Écho de Paris, yet not the one on Beardsley.

50 “Au jour le jour,” Journal des débats, 100 (11 Apr 1898): 1: “Des horizons nouveaux s’ouvrent pour les artistes incompris.”

51 La Justice (12–13 Apr 1898): 3; Le Radical (16 Apr 1898): 2; Le Bulletin de la presse, 4:3, 54 (21 Apr 1898): 484 (abridged).

52 See Matthew Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley: A Biography (London: Harper Collins Publishers, 1998), 121 (in note).

53 Charles Legras, “Au jour le jour: Aubrey Beardsley,” Journal des débats, 87 (29 Mar 1899): 1: “gai, moqueur, souffrant, destiné à mourir jeune.”

54 “Échos,” Mercure de France, 26:100 (Apr 1898): 335.

55 For an analysis of Jarry’s tropes and the ways he gathers inspiration from Beardsley’s work, see my article “Jarry et Beardsley,” L’Étoile-absinthe. Les Cahiers iconographiques de la Société des amis d’Alfred Jarry, 95–96 (2002): 49–67, http://alfredjarry.fr/amisjarry/fichiers_ea/etoile_absinthe_095_96reduit.pdf

56 Mercure de France, 26:101 (May 1898) includes Oscar Wilde, “Ballade de la geôle de Reading,” 350–70, translated by Davray; Alfred Jarry, “Gestes et opinions du Dr Faustroll, pataphysicien: V. Du pays des dentelles, à Aubrey Beardsley,” 399–400; Davray, “Aubrey Beardsley,” 485–91.

57 The Savoy, 6 (Oct 1896): 32–33; Mercure de France, 26:101 (May 1898): 485.

58 The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, 51.

59 See Zatlin, Catalogue Raisonné, II, 284.

60 The Letters of Aubrey Beardsley, 143 (ca. 11 July 1896 letter to Smithers).

61 See Andrew G. Lehmann, “Pierrot and Fin de Siècle,” in Romantic Mythologies, ed. by Ian Fletcher (London: Routledge/Kegan Paul, 1967), 209–23; Robert F. Storey, Pierrot: A Critical History of a Mask (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978); Jean de Palacio, Pierrot fin de siècle ou Les métamorphoses d’un masque (Paris: Séguier, 1990).

62 See Zatlin, Catalogue Raisonné, II, 334–35.

63 Davray, “L’Art d’Aubrey Beardsley,” 257.

64 Ian Fletcher, Aubrey Beardsley (Boston, Mass.: Twayne Publishers, 1987), 119.

65 Lautrec, “Note sur Aubrey Beardsley,” Le Courrier français, 21 (21 May 1899): 3.

66 Vittorio Pica, “Tre artisti d’eccezione,” Emporium, 19:113 (May 1904): 351, see https://emporium.sns.it/galleria/pagine.php?volume=XIX&pagina=XIX_113_351.jpg

67 Emil Hannover, “Aubrey Beardsley,” Kunst und Künstler, 1:11 (Nov 1903): 425, see https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/kk1902_1903/0434/image,info

68 See Catullus, “Carmen CI,” in Decadent Writings of Aubrey Beardsley, 181.

69 Meier-Graefe, “Aubrey Beardsley and his Circle,” 265–66, text 258–59.

70 In a letter to Gray, dated 17 Apr 1898 and authored on La Revue blanche paper, Fénéon writes to his friend Gray: “The lines you dedicate to his kind memory are exquisite, and you will find them printed as they stand, or nearly so.” See Félix Fénéon – John Gray, Correspondance, ed. by Maurice Imbert (Tusson: Du Lérot, 2010), 76: “Les lignes que vous consacrez à sa gentille mémoire sont exquises, et vous les trouverez imprimées telles quelles, ou à peu près.”

71 “Petite gazette d’art,” La Revue blanche, 16 (May 1898): 65–70 (the Moreau article opens the column, Gray’s article on Beardsley ends it, 68–70).

72 Partial title of Chris Snodgrass’s study, Aubrey Beardsley, Dandy of the Grotesque (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

73 Sturgis, Aubrey Beardsley, 340–51.

74 Mourey, “Aubrey Beardsley,” La Revue encyclopédique, 8:248 (4 June 1898): 520–21.

75 Tristan Klingsor, “Aubrey Beardsley,” Revue illustrée, 13:13 (15 June 1898): n.p. The issue again relates Beardsley to Gustave Moreau under a cover showing Adolphe Willette in a Pierrot costume. Klingsor draws the Moreau/Beardsley parallel by calling Beardsley “some ingenious sorcerer’s apprentice” (“quelque ingénieux apprenti sorcier”). The phrase refers to “Un maître sorcier” (“A Master Sorcerer”), the title of Jean Lorrain’s opening article on Moreau in the same issue.

76 Davray, “Aubrey Vincent Beardsley,” La Plume, 24:246 (15 July 1899): 449–51.

77 Desmarais, The Beardsley Industry, 117–22.

78 Robert de Montesquiou, “Le Pervers,” in Montesquiou, Professionnelles beautés (Paris: Félix Juven, 1905), 85–104.

79 Arthur Symons, Aubrey Beardsley, traduit par Jack Cohen, Édouard et Louis Thomas (Paris: Floury, 1906).

80 Montesquiou, “Aubrey Beardsley,” Le Figaro (21 Feb 1907): 1: “un trait tracé sur une glace par la pointe d’un diamant;” collected under the title “Beardsley en raccourci,” in Assemblée de notables (Paris: Félix Juven, 1908), 19–27.

81 Blanche, “Aubrey Beardsley,” Antée, 3:11 (1 Apr 1907): 1103–22; Blanche’s text would serve as “Preface” to Beardsley’s unfinished novel, “Sous la colline, une histoire romantique, traduit de l’anglais par A.-H. Cornette,” published first in Antée, 2:6 (1 Nov 1906): 539–72, then by Antée’s publisher Arthur Herbert in Bruges with Blanche’s preface, and finally in Paris (Floury, 1908) again with Blanche’s preface. It was later included in Blanche’s Essais et Portraits (Paris: Dorbon Aîné, 1912), 135–49, and Propos de peintre. De David à Degas, 1e série (Paris: Émile-Paul Frères, 1919), 111–31. Curiously the Bruges edition is not mentioned in Andries van den Abeele, “Une maison d’édition brugeoise: Arthur Herbert (1906-1907),” Textyles, 23 (2003): 95–101, https://doi.org/10.4000/textyles.796

82 See Lynn Garafola, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), 277.

83 Armand Dayot, La Peinture anglaise de ses origines à nos jours (Paris: Lucien Laveur, 1908), 339–41.

84 Edmond Jaloux, “L’époque de Beardsley,” Le Temps (26 Feb 1932): 3.

85 Roques, “Les artistes anglais: M. Beardsley,” 7: “Il sera dénigré à outrance par les uns, franchement admiré par d’autres; il ne sera indifférent à personne.”

86 Raymond Bachollet, “Les audaces du Courrier français,” Le Collectionneur français, 218 (Dec 1984): 9.