10. Literary masterpiece as a literary bank: A digital representation of intertextual references in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land

Aditya Ghosh and Ujjwal Jana

© 2024 Aditya Ghosh and Ujjwal Jana, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0423.10

Abstract

This chapter attempts to model a digital representation of all the intertextual references alluded to in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. It encompasses the references Eliot incorporated into this masterpiece, from Classical and Biblical texts to his contemporary literary texts, followed by an inventory of post-Waste Land texts which borrowed from the text in question. This work produced by Eliot throws any reader or scholar into a labyrinth of intertextuality and literary allusions, the sheer magnitude of which can potentially confuse as the range of the references reaches far and wide. There is a scholarly dispute about the changing paradigm of critical research works under the veneer of digital technology, as many are apprehensive about losing epistemological and ontological aspects of critical research work in the field of humanities under the sustained pressure of employing a digital medium.72 But, having the benefit of an archival digital repository and its capability to quickly access multiple texts from various resources corroborates the view that technology can facilitate the creation and dissemination of knowledge in the field of humanities. The main objective of this research is to create a repository where all the intertextual references of Eliot’s poem The Waste Land could be stored. This chapter will employ three different steps to demonstrate different sources of references and allusions that were used in the production of The Waste Land.

Keywords

Digital representation; Digital Humanities; digital technology; intertextuality; T.S. Eliot.

Introduction

Discussion and research on and about Digital Humanities (DH) have rapidly increased in intensity in Indian academia in the last eight to ten years. Research in literary fields has primarily been analytical and qualitative. On the other hand, digital methods and computational works primarily focus on data-driven quantitative research. Although the marriage between these two fields seems unlikely on a surface level, there is a recent trend in which scholarly activities flourish at the intersection of digital technologies and the disciplines of humanities (Buzzetti, 2019; Edmond, 2020; Jockers & Underwood, 2016; Pokrivcak, 2021; Schwandt, 2021). Using new applications and techniques, Digital Humanities makes new kinds of teaching and research possible, while at the same time studying and critiquing how these impact cultural heritage and digital culture (Wilkens, 2012; McPherson, 2012; Fiormonte, 2012; Hankins, 2023). In its attempt to bridge the gap between traditional knowledge-based domains and modern skill-based fields, DH aims to “use information technology to illuminate the human record and [bring] an understanding of the human record to bear on the development and use of information technology” (Scheibman et al., 2004, p. xiii). Therefore, Digital Humanities situates itself at the centre of many divergent areas and operates as “a nexus of fields within which scholars use computing technologies to investigate the kinds of questions that are traditional to the humanities, or, […] ask traditional kinds of humanities-oriented questions about computing technologies” (Fitzpatrick, 2012, p. 12).

The drive towards digital technologies has changed human perspectives rapidly in the 21st century. Cultural and intellectual consciousness has gone through a massive transformation. India has quickly participated in this transformation and devoted much intellectual and economic capital to this digital drive through Digital India, Bharat Net, UPI, Broadband Highways, Aadhar, DigiLocker, and Digitize India Platform. The postmillennial generation is swiftly moving away from the pen-paper-print medium to the digital mode, and this trend is influencing the traditional knowledge-based fields that have predominantly depended on physical books, pen and paper. Humanities departments are going through a crisis at this critical juncture, as students of this generation are more tech-savvy than ‘bookworm’. Humanities teachers and researchers are embracing digital modes in their pedagogical styles, as well as digitisation in study materials and research endeavours. Significant emphasis has been placed upon the adoption of digital technologies in humanities studies in the past decade.

As Dash states, there has been the rise of an:

[…] interactive interface for the new generation of scholars to enable them to extend their studies and research of humanities under a digital platform and gives them the power to apply traditional skills of the humanities (e.g., critical thinking) to understand digital culture while learning how digital technology can enable them to explore the key questions in the humanities (Dash, 2023, p. 38).

Digital Humanities have presented us with an alternate mode of study and research within the traditional domain of knowledge production. It has created an opportunity to explore the traditional knowledge system in a fresh manner, keeping it relevant to the current generation as it involves, “collaborative, transdisciplinary, and technologically engaged analysis, research, development, teaching, resource generation and making them available for the new generation of users” (Dash, 2023, p. 38).

Keeping this transformation in mind, this chapter aims to contribute to the alternative ways of studying canonical literature by adopting Digital Humanities methodology, keeping T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land at the centre of the chapter. Literature with the epic proportions of Eliot’s The Waste Land, Milton’s Paradise Lost, Joyce’s Ulysses, Hindu epics Ramayana and Mahabharata, Greek epics Aeneid and Metamorphosis, or Dante’s Inferno is difficult for students and teachers to lucidly elaborate in the classroom. It becomes all the more challenging for contemporary students who are estranged from studying physical materials and who are more oriented towards using technological devices.

This chapter presents a digital model, which acts as a repository of all the allusions and intertextual references in Eliot’s The Waste Land. This approach offers access to information about all of the poem’s references in one place. The chapter is a part of a bigger hypertext project, similar to the Victorian Web, which develops a digital platform that presents the allusions and referenced texts in one place, with access to these referenced texts that are either quoted in The Waste Land or other post-Waste Land texts that were inspired by Eliot’s work. This chapter only presents a visual representation of the repository through graphs and diagrams of the project, to generate interest among students and to inspire further research in the Digital Humanities. The authors are part of the larger project currently building a database for the visual representation of Eliot’s The Waste Land. This chapter introduces and models the database that is enabled by the collection of the data after a detailed study of the intertextual references. Diagrams and graphs have been prepared for this chapter with the help of digital technology. As the building of The Waste Land database will be through the affordances of digital technology, this chapter is likewise undoubtedly the product of Digital Humanities research.

Computational methods in the Digital Humanities have the potential to trace patterns in literary works which can inform qualitative analysis. The structuralist paradigm has demonstrated how elements in different cultural activities, for example, literature and movies, can be organised within a semiotic system. For example, most of the detective stories, irrespective of their sources, for centuries have followed a common structure.73 Similarly, all superhero movies follow a pattern or a structured narrative. A close analysis of Victorian novels reveals that they follow an underlying pattern or structure which remains the same while individual stories differ, along with characters and plotlines (Hingston, 2019; Garrett, 1977; Valint, 2021). Russian structuralist critic Vladimir Propp made an extensive study of hundreds of Russian folktales and discovered a pattern of underlying structures for these stories (Propp, 1968). Although they were different on an individual level and consisted of different characters and settings, all of them had seven character types—hero, villain, donor, provider, princess, fake hero and dispatcher—and all these stories served similar purposes.

What is important here is that, although the primary research work in literary fields involves qualitative analysis, most scholars ignore the quantitative nature of their work. These examples suggest that research work in literary fields also is “implicitly quantitative, pattern-based, and dependent on reductive models of the texts they treat” (Wilkens, 2015, p. 11). Computational methods in Digital Humanities help in “identifying and assessing literary patterns at scales from the individual text to whole fields and systems of cultural production” (Wilkens, 2015, p. 11). Digital Humanities has bridged the gap between these two fields and offers new approaches to carrying out innovative ground-breaking research. Digital Humanities, therefore, is “an interdisciplinary area of research, practice and pedagogy that looks at the interaction of digital tools, methods and spaces with core concerns of humanistic enquiry” (Sneha, 2016, p. 10). Maintaining a holistic approach and keeping the theoretical concerns and the possibilities of further emergence in mind, Digital Humanities Quarterly considers that:

Digital humanities is a diverse and still emerging field that encompasses the practice of humanities research in and through information technology, and the exploration of how the humanities may evolve through their engagement with technology, media, and computational methods (Sneha, 2016, p. 10).

Research work in the Digital Humanities has largely focused on literary texts. English departments, specifically, have been important to Digital Humanities research. Some of the ground-breaking research projects on Digital Humanities have given birth to The Victorian Web, the Shakespeare Electronic Archive, The Whitman Archive and many more. The Victorian Web is a repository of various Victorian digital objects. It is “a hypertext project derived from hypermedia environment, Intermedia and Storyspace” (Victorian Web, 2024). Although the repository had around 1500 documents including Victorian texts when it was created, it boasts of having nearly 128,500 items currently. Shakespeare Electronic Archive and The Whitman Archive are archival works generated by Digital Humanities projects. Shakespeare Electronic Archive was created to keep all “electronic texts of Shakespeare’s plays closely linked to digital copies of primary materials” (Shakespeare Electronic Archive). This archival work includes images from the First Folio, collection of arts and illustrations from Hamlet and many digitised items from film on Hamlet. The Whitman Archive has documented and stored Whitman’s life and works, including his letters and essays.

Apart from the hypertext model adopted by the Victorian Web and many archival repositories, Digital Humanities research has significantly focused on text modelling and encoding for critical analysis and to evaluate patterns and forms of literary works (Argamon & Olsen, 2009; Jannidis & Flanders, 2012; Kralemann & Lattmaan, 2013; McCarty, 2004; Marrus & Ciula, 2014; Sharma & Sharma, 2021). This indicates that literary works and literary figures are often the subject of significant Digital Humanities research projects. Matthew Kirschenbaum (2016) argues that “after numerical input, text is the most traceable type of data for computers to manipulate”, and “there is the long association between computers and composition” (pp. 8–9). Computational methods, digital data and digital databases:

[…] have become indisputable resources for literary study, not just for archival research but also literary interpretation, and the amount of data available in text form—think Google Books, Project Gutenberg, and UPenn’s Online Books Page—continues to grow at an astonishing rate (Pressman & Swanstorm, 2013).

Like many literary stalwarts, T.S. Eliot has also been the subject of many Digital Humanities research works. Arbuckle (2014) discusses the preparation of The Waste Land for iPad. She points out that although it is widely successful, it is not free of issues. He further discusses the importance of robust collaboration and reconciliation between scholarly practices and computational designs in the creation of cultural content through digital means.

Kim et al., (2020) make an extensive study of many modern writers, with a particular focus on Eliot. With the use of computational methods, they try to discover some patterns of vocabulary density and the occurrence of nouns and adjectives in The Waste Land. Juan Antonio Suarez (2001) emphasises Eliot’s dependency on technological devices through his special connection to the gramophone. Although Eliot never flaunted his affection for technological gadgets, their impact on modern society is well documented in his literary production. Suarez argues that: “Eliot’s writing, like Warhol’s multimedia projects, was uneasily entangled in gadgets, circuits, media networks, and technologies of textual production and reproduction” (2001, p. 747). An extensive review of these research articles reveals that, although Digital Humanities research has focused on many aspects of Eliot’s The Waste Land, little research work has been carried out to explore the work’s extended references, which range from classical literature to Eliot’s contemporaries.

The objective of this chapter is to fill that gap. It aims to model a digital representation of all the intertextual references in T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. It encompasses Eliot’s interests that he incorporated into this masterpiece as well as other literary works. It also includes books that were published later and borrowed from The Waste Land. The sheer magnitude of Eliot’s poem can potentially confuse both lay readers and scholars, as the range of the references reaches from Classical literature, to Biblical allusions, to the contemporaries of Eliot’s time. This research creates a repository that provides the intertextual references in one place, thereby making it a kind of literary bank.

I.

The Waste Land is Eliot’s masterpiece in the history of literature. In this work, Eliot discusses the morally corrupt, degenerate condition of modern society. He provides hundreds of literary allusions for his representation of a horrific social situation. Despite making giant economic strides and technological advancements, Eliot views his society as one whose heart and soul have become hollow. In Eliot’s outlook, society is morally corrupt; there is political instability, and social values have given way to jealousy envy, revenge, greed and betrayal. People are alienated, fragmented, mentally deranged, joyless and sexually aberrant so that lechery and debauchery thrive (Bellour, 2016; Hoover, 1978; Karim, 2019; Maheswari, 2016; Qasim, 2022).

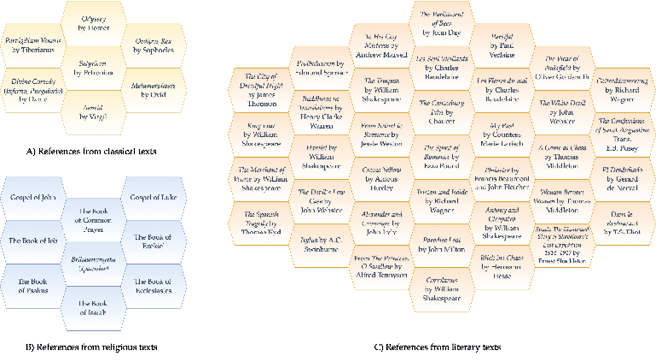

To portray the sordid account of this degenerate society, Eliot sources intertextual references from Classical texts, Biblical texts and many literary texts as follows:

Fig. 10.1 The allusions from Classical texts, Biblical texts and literary texts in The Waste Land.

In the beginning of the poem, references to Classical texts like Virgil’s Aeneid, Ovid’s Metamorphosis, and Dante’s Inferno are used extensively (Bhardwaj & Kumar, 2023; Donker, 1974; Rapa, 2010). With these allusions we revisit, for example, Satan, Hell, the Cumaean Sibyl, and the rape of Philomela in Metamorphosis. Eliot makes it clear that modern cities are like Hell, in which people suffer, are punished, and are mentally tormented. There is sexual exploitation, perversion and debauchery everywhere. There are references to Sophocles and Seneca’s texts, because Eliot suggests that, like the city of Thebes in Oedipus Rex, the modern city of London also is going through a pandemic (Saxby, 2020). People are restless as they are fragmented morally and psychologically and lust for each other’s downfall. There is anarchy everywhere. There is sterility and society is decaying.

Though the poem deals with themes of decay and degeneration, the turn towards a solution to arrest this decline is underpinned by many Biblical references (Alahdal, 2017; Kumar, 2018; Mahmud, 2020). Eliot is also searching for a resolution for the rebirth of society. His search for this holy grail draws on intertextual references to the search for the Holy Grail of Christ. “The Burial of the Dead” in The Waste Land provides a reference to the Anglican Book of Common Prayer which suggests that death is necessary for rebirth and revival. Throughout Eliot’s poem, there are abundant references to The Book of Common Prayer, The Book of Job, the Gospel of John, the Gospel of Luke, The Book of Ezekiel and The Book of Ecclesiastes (Ananda, 2023; Lauren, 2003).

In the beginning of the poem, the reference to “broken images” (L. 22–23) provides an allusion to Ezekiel’s narration of God’s judgement of people worshipping idols. The reference compares the idolisation of money by modern society and God’s judgement accordingly, which leaves them without souls and with many psychological traumas. In the Bible, Hebrews are seen lamenting for the lost city of Jerusalem after they are exiled to Babylon. Eliot uses this reference to the loss of a glorified past in his lamentation for a hopeless, degenerate society that is hollow, corrupt and volatile. Apart from these references to Classical and Biblical texts, there are various connections to many other literary texts, including those by Shakespeare, Chaucer, Spenser, Marvell, Webster, Middleton, Huxley, Baudelaire, Milton and Wagner.

II.

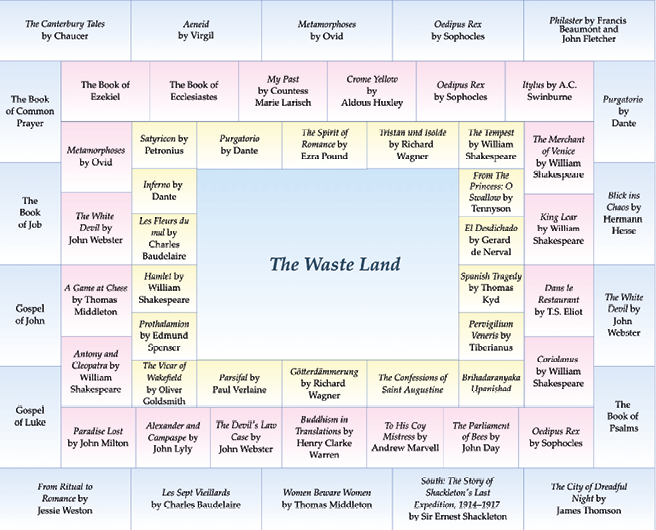

Fig. 10.2 A visual representation of allusions in The Waste Land: i) rectangular boxes (yellow), which are closest to the title of the poem, contain texts from which lines have been directly borrowed; ii) rectangular boxes (pink) consist of texts from which phrases and names have been borrowed; iii) the outermost rectangles (blue) contain other thematic references to various texts.

In the above image, the closest rectangle to the title of The Waste Land contains texts from which Eliot directly quoted lines for his work. The next set of rectangles consists of texts from which Eliot borrowed phrases and names for intertextual references, and the outermost rectangles contain texts that the poem references indirectly, but from which Eliot has borrowed no direct quotations, phrases or names. For example, the epigraph of The Waste Land is taken from Satyricon, written by Petronius, whose translation reads: “For on one occasion I myself saw, with my own eyes, the Cumaean Sibyl hanging in a cage, and when some boys said to her, ‘Sibyl, what do you want?’ she replied, ‘I want to die’” (Rainey, 2005, p. 75). Eliot directly quotes “Frisch weht der wind/ Der Heimat zu,/ Mein Irisch Kind/ Wo weilest du?” [Fresh blows the wind / To the homeland; / My Irish child, / Where are you tarrying?] (L. 34–38) from Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. This text tells the story of Tristan and Isolde and how they fell in love on their journey from Cornwall to Ireland. Eliot uses this allusion at the beginning of the poem to suggest that Death is the ultimate cure for all the decay, corruption, sterility and sexual debauchery that has taken hold of society. Tristan and Isolde begins and ends with death.

Eliot extensively quoted from Shakespeare’s works. “Those are pearls that were his eyes” (L. 48) is a direct quotation borrowed from The Tempest. The farewell words “Good night, ladies, good night, sweet ladies, good night, good night” (L. 171–-172) of the ladies in the bar in the closing lines of A Game of Chess resemble Ophelia’s “farewell to the Queen and other ladies of the castle” (Purwarno, 2003, p. 132) in Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Eliot borrows the phrases “—Hypocrite lecteur,—mon semblable,—mon frère!” [Hypocrite reader!—You!—My twin!—My brother!] from Baudelaire’s poem Les Fleurs du Mal. He also provides an allusion to Spenser’s Prothalamion and directly borrows a quotation: “sweet Thames, run softly, till I end my song” (L. 176). Next, Eliot quotes directly “Et O ces voix d’enfants, chantant dans la coupole” [And O those voices of children singing under the cupola] (L. 202) from Paul Verlaine’s poem Parsifal. Eliot used this line to turn the attention towards a longing for the innocence of childhood and the sanctity of the church. “When lovely woman stoops to folly” (L. 253) is from Oliver Goldsmith’s The Vicar of Wakefield. This refers to a lamentation because of the seduction of money and physical pleasure and its negative moral effect on modern people. It refers to the envy, corruption, debauchery, and sexual perversion of the modern world.

The phrase “burning burning burning burning” (L. 308) is taken from Buddha’s Fire Sermon. It describes the “burning of passion, attachment and suffering” (Sharma, 2020, p. 7). “Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata” (L. 433) is taken from The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad in which God preached to men who have gone astray to return to the life of giving, which is to be kind and offer help, show compassion to others, and to rein in unruly behaviour and aggression. Eliot ends the poem with “Shantih Shantih Shantih” (L. 434) which is also taken from The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. “Shantih” means “peace”, and is necessary for an ordered human existence. People in this wasteland are suffering from mental unrest, they are alienated, they are lost, they are without hope and traumatised. If they want to get back to the glorified peaceful past and have Shantih in life, they have to practice Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

III.

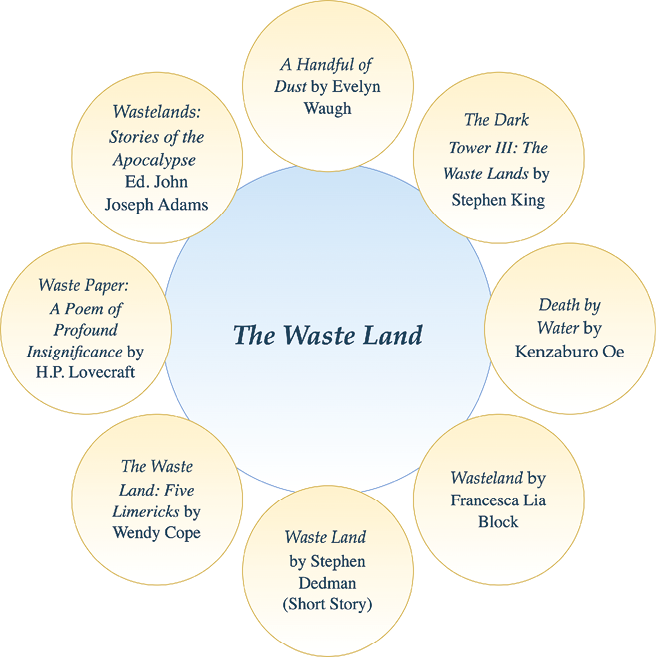

Fig. 10.3 All the texts that have borrowed references from or been inspired by Eliot’s The Waste Land.

The Waste Land not only references past works, but the poem itself has influenced many future texts. The title of Evelyn Waugh’s novel, A Handful of Dust (1934), which satirises human values, morality, mortality and all human endeavours, is borrowed from The Waste Land. Much more recently, Kenzaburo Oe published Death by Water in 2009, a novel set against the backdrop of World War II that narrates a man’s search to uncover the mysteries surrounding the death of his father. The influence upon the title of Stephen Dedman’s short story Waste Lands is obvious, while Dedman’s other short story, The Lady of Situations, is inspired by Madam Sosostris’s tarot reading in Eliot’s poem. Not only is the title of Francesca Lia Block’s novel Wasteland (2003) influenced by Eliot’s work, but the novel quotes extensively from the poem towards the end—as does Stephen King’s novel The Dark Tower III: The Waste Lands (1991), which quotes many lines from the poem in the opening pages as well as borrowing its title.

Not all of the references are reverential. H.P. Lovecraft wrote a parody of the poem, Waste Paper: A Poem of Profound Insignificance. He considered The Waste Land a meaningless poem that accumulated quotations and references from hundreds of books throughout literary history to no purpose; a waste of materials and time that lacks significance.

Conclusion

There exist intellectual and scholarly disputes about the changing paradigm of critical research methods that use digital technology. The advantages of an archival repository and access to multiple texts suggest that the affordances of technology can facilitate the creation and dissemination of knowledge in the field of humanities. Moreover, interpretative, generative and qualitative research enabled by the intersection of humanities and the digital medium has already demonstrated that Digital Humanities can offer access to research sources and materials. DH enables scholars to access and analyse vast corpora of materials from various sources and synthesise with close-reading method of traditional research which brings in new insights and allows for a fresh interpretation. By providing plethora of data and statistical methods, DH helps researchers to analyse and understand the patterns of literary production in any particular age, external factors which shape the literary tradition of any decade or century, literary movements and their influences on author/reader etc. Therefore, DH does not undermine or neglect the nuances of traditional research methods nor does it reject the close-reading of literary texts, instead it enhances further research possibilities with its wider reach to far away materials and providing data-driven statistical methods. In the case of this chapter, bringing the intertextual references of Eliot’s masterpiece The Waste Land into the framework described will prove a lasting resource for scholars and educators alike.

Works Cited

Alahdal, M., Ahmed, Y., & Mane, D.R. (2017). Sterility as a recurring theme in Eliot’s The Waste Land. Indian Scholar 3(4), 78–82.

Arbuckle, A. (2014). Considering The Waste Land for iPad and Weird Fiction as models for the public digital edition. Digital Studies/le Champ Numérique 5(1). https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.50

Argamon, S., & Olsen, M. (2009). Words, patterns, and documents: Experiments in machine learning and text analysis. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 3(1).

Bellour, L. (2016). The religious crisis and the spiritual journey in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Arab World English Journal 7(4), 422–438.

Bhardwaj, P., & Kumar, D. (2023). A deep reflection of disorder and decay in The Waste Land. Humanities and Social Sciences 83(1), 115–122.

Birsanu, R. (2010). Intertextuality as translation in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, SUNDEBAR 21, 21–35.

Buzzetti, D. (2019). The origins of humanities computing and the Digital Humanities Turn. Humanist Studies & the Digital Age 6(1). https://doi.org/10.5399/uo/hsda.6.1.3

Chaudhuri, S. (2021). The game’s the thing: Politics and play in Middleton’s A Game at Chess. Études Épistémè. Revue de littérature et de civilisation (XVIe–XVIIIe siècles) 39. https://doi.org/10.4000/episteme.11534

Dash, N.S. (2023). Digital Humanities: Harnessing digital technology for sustenance and growth of the Humanities. In Mandal, Pranab, Kumar, and Ghosh, Sankha (Eds). The Incandescent Classroom: Essays in Honour of Prof. Satyaki Pal. (pp. 38–55). RK Mission Residential College Press.

Donker, M. (1974). The Waste Land and The Aeneid. PMLA 1, 164–173. https://doi.org/10.2307/461679

Edmond, J. (Ed.). (2020). Digital Technology and the Practices of Humanities Research. Open Book Publishers. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0192

Eliot, T.S. (1922). The Waste Land. Binker North.

Fiormonte, D. (2012). Towards a cultural critique of the digital humanities. Historical Social Research 37(3), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.37.2012.3.59-76

Fitzpatrick, K. (2010). Reporting from the Digital Humanities 2010 Conference. In The Chronicle of Higher Education. http://chronicle. com/blogs/profhacker/reporting-from-the-digital-humanities-2010-conference/25473

Garrett, P.K. (1977). Double plots and dialogical form in Victorian fiction. Nineteenth-Century Fiction 32(1), 1–17.

Griffith, J. (2020). Victorian structures: Architecture, society, and narrative. Nineteenth-Century Contexts 44(5), 543–544.

Haas, L. (2003). The revival of myth: Allusions and symbols in The Waste Land. Ephemeris 3(8). https://digitalcommons.denison.edu/ephemeris/vol3/iss1/8

Hankins, G. (2023). Reproducing disciplinary and literary prestige: The index of major literary prizes in the US. International Journal of Digital Humanities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42803-023-00082-x

Hingston, K-A. (2019). Articulating Bodies: The Narrative Form of Disability and Illness in Victorian Fiction. Liverpool University Press. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/52808

Hoover, J.M. (1978). The urban nightmare: Alienation imagery in the poetry of T. S. Eliot and Octavio Paz. Journal of Spanish Studies: Twentieth Century 6, 13–28.

Jannidis, F. & Flanders, J. (Eds). (2012). Knowledge organization and data modelling in the humanities: An ongoing conversation. Workshop at Brown University.

Jockers, M.L. & Underwood, T. (2016). Text‐mining the Humanities. In S. Schreibman, R. Siemens, & J. Unsworth (Eds). New Companion to Digital Humanities. John Wiley & Sons.

Karim, Md., Rezaul. (2019). Spiritual barrenness, war, and alienation: Reading Eliot’s The Waste Land. IJRHAL, 7(6), 393-404.

Khan, A.B., Mansoor, H.S., & Khan, M.Y. (2015). Critical analysis of allusions and symbols in the poem The Waste Land by Thomas Stearns Eliot. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Modern Education 1, 615–619.

Kim, S., et al., (2020). Implications of vocabulary density for poetry: Reading T. S. Eliot’s poetry through computational methods. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqaa009

Kirschenbaum, M. (2016). What is digital humanities and what’s it doing in English departments? In M. Terras, J. Nyhan, & E. Vanhoutte (Eds). Defining Digital Humanities. (pp. 195–203). Routledge.

Kralemann, B. & Lattmann, C. (2013). Models as icons: Modelling models in the semiotic framework of Pierce’s theory of signs. Synthese 190(16), 3397–3420. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s11229-012-0176-x

Kumar, S. (2018). The theme of decay and destruction in Eliot’s The Waste Land. Parisheelan, XIV(2).

Maheswari, C., Baby N. (2016). Modern life as a waste land in Eliot’s The Waste Land. IJELLH, IV(XI).

McCarty, W. (2004). Modelling: A study of words and meanings. In S. Schreibman, R. Siemens, & J. Unsworth (Eds). A Companion to Digital Humanities. Blackwell.

McPherson, T. (2012). Why are the digital humanities so white? Or thinking the histories of race and computation. Debates in the Digital Humanities 1, 139–60.

Mahmud, R. (2020). Spiritual barrenness and physical deformities of the distressed modern people in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Language in India 20(7).

Marras, C. & Ciula, A. (2014). Circling around texts and language: Towards ‘pragmatic modelling’ in Digital Humanities. Digital Humanities—Book of Abstracts, 255–257. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/10/3/000258/000258.html

Patil, U. (2023). A critical study of the myths, classical references and allusions in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. IJFMR 5(6).

Pokrivcak, A. (2021). Digital Humanities and Literary Studies. Trnava 5(7).

Pressman, J., & Swanstrom L. (2013). The literary and/as the Digital Humanities. DHQ: Digital Humanities Quarterly 7(1). https://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/7/1/000154/000154.html

Propp, V. (1968). Morphology of the Folktale. University of Texas Press.

Purwarno, P. (2003). Echoes of Shakespeare in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. JULISA 3(2), 128–137.

Qasim, M. (2022). The land and the waste: Meaninglessness and absurdity in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. SJESR 5(4), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.36902/sjesr-vol5-iss4-2022

Rainey, L. (Ed.). (2005). The Annotated Waste Land with Eliot’s Contemporary Prose. Yale University Press.

Rapa, J. (2010). Out of this stony rubbish: Echoes of Ezekiel in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Master’s Theses. 692. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/theses/692

Saxby, G. (2020). The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot: Is it a dialectic text? Swinburne University of Technology, https://www.doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.28389.63205

Scheibman, S., Siemens R., Unsworth, J. (2004). The Digital Humanities and Humanities Computing: An Introduction. In S. Scheibman, R. Siemens, J. Unsworth (Eds). A Companion to Digital Humanities. Blackwell.

Schwandt, S. (Ed.). (2021). Digital Methods in the Humanities: Challenges, Ideas, Perspectives. Bielefeld University Press. https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/47133

Sneha, P.P. (2016). Mapping Digital Humanities in India. The Centre for Internet & Society. https://cis-india.org/papers/mapping-digital-humanities-in-india

Shakespeare Electronic Archive. https://shea.mit.edu/shakespeare/htdocs/main/index.htm

Shakespeare, W. (2019). Antony and Cleopatra. Maple Press.

Shakespeare, W. (2014). King Lear. Maple Press.

Sharma, K.S., & Sharma, A. (2021). Literature and Cultural Studies Through Data Mining. ICFAI Journal of English Studies 16(4), 119–125.

Sharma, L.R. (2020). Detecting major allusions and their significance in Eliot’s poem The Waste Land. Journal for Research Scholars and Professionals of English Teaching 21(4), 1–9.

Suarez, J. (2001). T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, the gramophone, and the modernist discourse network. New Literary History 32(3), 747–768. https://www.doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2001.0048

Valint, A. (2021). Narrative Bonds: Multiple Narrators in the Victorian Novel. The Ohio State University Press.

Victorian Web. (2024). In Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victorian_Web

Wilkens, M. (2012). Canons, close reading, and the evolution of method. In M. Gold (Ed.). Debates in the Digital Humanities. University of Minnesota Press.

Wilkens, M. (2015). Digital Humanities and its application in the study of literature and culture. Comparative Literature 67(1), 11–20. https://www.doi.org/10.1215/00104124-2861911