3. Netflix and the shaping of global politics

Diane Colman

© 2024 Diane Colman, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0423.03

Abstract

This chapter begins by outlining the meaning and importance of soft power in global politics and briefly detailing the consideration of popular culture in the International Relations (IR) discipline. It then provides a detailed description of the research design of the database project, taking account of positivist conventions in qualitative studies by utilising the hybrid methodologies in the Digital Humanities interdisciplinary approach. International Relations as a discipline understands power on a global scale. Such understanding includes the concept of ‘soft power’ and the role of popular culture in projecting and universalising hegemonic state values. In the globalised world of today, the power of individuals often transcends state boundaries. This case study is about Netflix, which, as a global actor, is the leading entertainment streaming service. Netflix has considerable capacity to influence its audiences’ ideas about the world, projecting immense soft power worldwide. Examining the ideological basis of this power is important in understanding world politics. The creation of a comprehensive database that categorises all Netflix Original films according to a carefully selected set of ontologies provides the epistemological tools necessary to suit the needs of IR studies.

Keywords

Netflix; international relations; database; soft power.

Introduction

International Relations (IR) is a discipline that understands power on a global scale. Such understanding includes the concept of ‘soft power’ and the role of popular culture in projecting and universalising hegemonic state values. While a growing number of IR scholars are now using an ideational conceptualisation that draws on discursive theories from other disciplines, much of mainstream IR underestimates the power of popular culture to represent, reflect and constitute world politics. The reason for this is largely epistemological: as a social science, IR privileges positivist approaches and specifies the importance of data collection; the macro; the structural. Such approaches usually focus on the power of states as unitary actors.

But in the globalised world of today, the power of individuals often transcends state boundaries. As a global actor, the world’s leading entertainment streaming service, Netflix, has considerable capacity to influence its audiences’ ideas about the world, projecting immense soft power worldwide. Examining the ideological basis of this power is important in understanding world politics. The creation of a comprehensive database that categorises all Netflix Original films according to a carefully selected set of ontologies should provide the epistemological tools necessary to meet the tendency of IR to privilege positivist methodologies. This may well create legitimacy within the discipline and enable us to acknowledge and reassess the insights that the lens of popular culture brings to the study of IR, hopefully leading to a more complexly articulated and relevant theoretical basis for the understanding of what constitutes world politics. This chapter will begin by outlining the meaning and importance of soft power in global politics and briefly detailing the consideration of popular culture in the IR discipline. It will then provide a detailed description of the research design of the database project, taking account of positivist conventions in qualitative studies by utilising the hybrid methodologies in the Digital Humanities interdisciplinary approach.

Soft power

The term ‘soft power’ was coined by political scientist Joseph Nye in his 1990 book, Bound to Lead. Since then, he has developed the term further whilst maintaining a central ideational definition. According to Nye, soft power is “the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments” (2004, p. x), “the ability to affect others and obtain preferred outcomes by attraction and persuasion” (2017, p. 2). Soft power, which Nye also calls “co-optive” or indirect power, rests on the attraction a set of ideas possesses, or on the capacity to set political agendas that shape the preferences of others (1990, pp. 31–35). Soft power is, therefore, related to intangible resources like culture, ideologies and institutions (Zahran & Ramos, 2010, p. 13). In fact, Nye’s general conception of “power refers to more ephemeral human relationships that change shape under different circumstances” (2011, p. 3). This enlarges ideas about what exactly constitutes political power. Rather than power being understood in material terms, political power “becomes in part a competition for attractiveness, legitimacy, and credibility” (2004, p. 31). The ability to develop widespread understanding and acceptance of a country’s values, motivations and interests becomes an important source of attraction and forms its soft power.

While he extended the idea to other states, most notably the USSR and China, in producing his extended scholarship on soft power, Nye specifically sought to explain how American global leadership was not in decline despite the challenge of other rising powers. The global reach of US influence could not be explained through military and economic power alone. He considered that many countries were attracted to, and approved of, US global leadership, providing less resistance to its pursuit of its goals as US power was understood as legitimate by other states. Nye specifically sought to influence foreign policymaking to ensure that America’s global hegemonic position continued. Nye’s idea of soft power is, therefore, an extension of Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, which involves a combination of coercion and consent, as “domination” and as “intellectual and moral guidance” (1971, p. 215). Hegemony, as soft power, works through consent on a set of general principles that secures the supremacy of a group and, at the same time, provides some degree of satisfaction to the other remaining groups. Extending this Gramscian notion to international relations, the cultural, economic, and social values of the hegemon are positioned as the civilisational values of the globalised society (Cox, 1983, p. 51).

This then leads to consideration of how such widespread consent to these hegemonic values is produced, secured, and reproduced over time. While Gramsci and Nye both focus on state power, they also both recognise that the soft, consensual part of this power comes from civil society rather than governments as “propaganda is not credible and thus does not attract” (Nye, 2017, p. 3). For Gramsci, the ruling class ruled most effectively when its control over society was least visible. This meant that his notion of the state included the underpinnings of the political structure in civil society. Gramsci thought of these in concrete historical terms: the church, the educational system, the press; all the institutions that helped to create in people certain modes of behaviour and expectations consistent with the hegemonic social order (Cox, 1983, p. 51). According to Nye, the generation of soft power is also affected by a host of non-state actors within and outside a country. Those actors affect both the general public and governing elites in other countries and create an enabling environment for government policies (2011, p. 69). Both concepts make reference to a set of general principles, ideas, values and institutions shared by, consented to, or regarded as legitimate by different groups, but that at the same time are resources of power, influence and control.

Nye highlights three sources of soft power:

[…] culture (in places where it is attractive to others), political values (when the state lives up to them at home and abroad) and foreign policies (when they are seen as legitimate and having moral authority) (2004, p. 11).

Similarly, Gramsci considers the sphere of ideas and culture to be essential, manifesting a capacity to obtain consensus and create a social basis for it (Zahran & Ramos, 2010, p. 21). And so, it is to this third, cultural site of power that we will now turn.

Popular culture and world politics

As indicated previously, the academic discipline of IR is particularly concerned with power in the global context. While this has traditionally focused on military and economic power, there is recognition that culture can also be considered as a resource of power, influence and control.

Taking culture seriously as a carrier of political values and norms is supremely important to global politics and has been seen as such since the ‘cultural turn’ in IR in the late 1980s. This coincided with an intellectual movement across the humanities and social sciences that challenged the orthodoxy of claims to objective, universal knowledge. Leading IR constructivists such as Nicholas Onuf (1989) and Alexander Wendt (1992) created a social theory of relations between states, that we live in a world of our own making and the world that we construct is one of varied identities and interests formed through social interaction and institutions. For Christian Reus-Smith (1989), cultural norms, principles and rules provide deep constitutive value to the development of institutional practices in the international system.

Exactly what is meant by culture is a contested term throughout the academy with many contradictions and complexities. Because of these incompatibilities, theorists who think about what culture is have tried to come up with less static and more open definitions of culture, which focus on how culture is related to meaning rather than trying to pin culture to a particular place at a particular time, or to particular objects. According to Stuart Hall, “culture ... is not so much a set of things—novels, paintings or TV programs and comics—as a process, a set of practices” (1997, p. 2). For Hall, “culture is concerned with the production and the exchange of meanings between members of a society or group” (1997, p. 2). Or as John Hartley defines it, culture is “(t)he social production and reproduction of sense, meaning and consciousness” (1994, p. 68). Culture has to do with how we make sense of the world and how we produce, reproduce and circulate sense. We circulate sense about the world in many ways, and one of the ways we do this is through stories. This is why another cultural theorist, Clifford Geertz, described culture as “an ensemble of stories we tell about ourselves” (1975, p. 448). The interrelated representations produced by these stories interact to constitute a frame of meaning which, through repetition, is transformed from being a culturally produced understanding into what is identified as ‘common sense’ as represented in the Gramscian tradition.

Formal cultural exchange has been an important aspect of statecraft for millennia, and the influence of high culture is well considered within both the academy and diplomatic circles. Most observers would agree that high culture produces significant soft power for a state. Yet there is often a clear distinction between high culture and popular culture.

Many intellectuals and critics disdain popular culture because of its crude commercialism. They regard it as providing mass entertainment rather than information and thus having little political effect (Nye, 2004, pp. 44–46).

Far from being insignificant, however, Roland Barthes established that the banal, or “what goes without saying” (2009, p. xix) is eminently worthy of closer attention and analytical scrutiny. “It is that content, whether reflected favourably or unfavourably, that brings people to the box office. That content is more powerful than politics or economics. It drives politics and economics” (Wattenberg, quoted in Nye, 2004, p. 47). As Jutta Weldes and Christina Rowley say:

Consumption is inextricably linked to the production and re-production of meanings—the maintenance of some, the transformation of others (whether through subversion, overt challenge or gradual change) (2015, p. 1).

For J. Furman Daniel and Paul Musgrave:

[p]opular culture is more than a diversion from the serious stuff of international relations. It plays a greater role in shaping the world than mainstream international relations have recognised (2017, p. 513).

Popular culture can unite, either in a narrow way around a specific text, activity, location or person, or in a more general way, through a network of thoughts, feelings, and/or behaviours that interrelate to constitute it (Reinherd, 2019, p. 1). Wide-ranging or narrowly focused, popular culture is the commonality that weaves us together to help us find and make meaning, discover ourselves and each other, build community and solidarity, and make sense of the world and our place in it (2019, p. 2).

For soft power to be effective as a hegemonic tool, it must appeal to as large an audience as possible (Bruner, 2019, p. 12). It becomes obvious, then, that the most prevalent site for interacting with, and being heavily influenced by, cultural practices that produce, organise and circulate meaning through stories told about the world is what is most popular. Popular culture is for the public; it is for the masses. For everyday working people “who perhaps could not afford the ‘finer’ things of a society or culture but still find meaning and solidarity through so-called ‘low culture’” (Reinherd, 2019, p. 1). There has been a growing awareness that popular culture can substantially affect and influence international relations by propagating and shaping world political ideas via mass media (Daniel & Musgrave, 2017, p. 512). Popular culture, according to Kyle Grayson, Matt Davies and Simon Philpott:

… has been identified as a critical site where power, ideology and identity are constituted, produced and/or materialized. There is a range of signifying and lived practices such as poetry, film, sculpture, music, television, leisure activities and fashion that constitute popular culture (2009, pp. 155–156).

But, when it comes to the power and influence of pop cultural forms, it is the ‘movie’ that reigns supreme. As Daniel and Musgrave say, “IR scholars should realize that more people have learned how the world works from Steven Spielberg than from Stephen Walt” (2017, p. 345).37 Much of American soft power has been produced by Hollywood over almost a century of production. Nye quotes a former French foreign minister who observed that Americans are powerful because they can “inspire the dreams and desires of others, thanks to the mastery of global images through film and television” (Nye, 2004, p. 8). The promotion and export of the images, stories, sounds, and sights of popular movies help to create a common sense of world politics. Examination of these works shows how popular culture constructs national interests, creates ideas of belonging that delineate ‘us’ from ‘them’, and makes sense of world events. As award-winning filmmaker Ken Loach said at the 2019 BAFTAs:

… [f]ilms can do many things, they can entertain, terrify, they can make us laugh and tell us something about the real world we live in (Demianyk, 2017).

According to Nye, the line between information and entertainment has never been as sharp as some academics imagine (2004, p. 47), and it is becoming increasingly blurred in the rapidly expanding global media landscape. The formation of entirely new types of media actors has empowered a broad range of civil society voices to the mediation of the world politics of today. Hegemony is in continuous need of “active agents, in this case, the producers of popular culture” (Dittmer, 2010, p. 62). One of the most powerful new non-traditional media producers is the hugely successful streaming platform, Netflix.

As we became more and more isolated from the world during the COVID-19 pandemic, many of us retreated into the worlds created in movies and television shows, streamed into our homes, on demand, 24 hours a day. While watching alone in our bedrooms is an individual experience, with so many of us watching the same movies, we are really engaging in a shared experience, a global experience. As the leading streaming platform, Netflix is a truly global media outlet. Its capacity to influence its audiences’ ideas about the world through its streaming of popular cultural artifacts is clear. And so, it is important that the discipline of IR looks more closely at this powerful site of what it terms soft power.

Netflix

Stories move us.

They make us feel more emotion,

see new perspectives,

and bring us closer to each other. (Netflix, 2023)

This is (at the time of writing) the pop-up on the Netflix ‘about’ page. It is easy to see the concept of culture as meaning-making here, as well as the consciously considered place Netflix reveals itself to hold. Founded in the USA in 1997 by Reed Hastings and Marc Randolph as a DVD mail rental service, Netflix launched the world’s first DVD rental and sales website the following year, followed by its subscription service the year after, providing members with unlimited rentals for a flat monthly fee. In 2007, the Netflix streaming service was introduced, with membership surpassing 10 million by 2009. Netflix then began its push into international markets, expanding to Canada in 2010, Latin America and the Caribbean in 2011, the UK, Ireland and the Nordic countries in 2012 and many European countries in 2014. Membership extended to Australia, New Zealand, Japan, Italy, Spain and Cuba in 2015. It then simultaneously launched in an additional 130 countries in 2016. Netflix is now an undisputedly global media outlet with over 200 million subscribers in more than 190 countries around the world (Netflix, 2023). As a global actor, and the leading entertainment streaming service, Netflix clearly has considerable capacity to influence its audiences’ ideas about the world, projecting immense soft power worldwide.

While media has always played an important role in shaping how we have viewed and approached global politics, the new digital media landscape of today has changed how new media platforms have depicted and mediated politics. Prior to the emergence of streaming platforms, global media corporations developed around and catered to either the state or business and advertisers. While the platforms developed by traditional broadcasters funnel users into larger media ecosystems (such as Fox and NBCUniversal), and others tie in with additional services or products (Disney, Amazon, Apple TV) and generate revenue from advertising, Netflix’s financial success depends solely on the company’s ability to attract and retain subscribers.38 To ensure its existing users do not unsubscribe and join the competition, Netflix has devised, developed and refined the Netflix recommender system (NRS), which is a core feature of its business model and brand (Pajkovic, 2022, p. 216). This NRS is a sophisticated algorithm that Netflix utilises to recommend content to users and personalise nearly every aspect of a customer’s experience on the platform. It is also imperative to its formulation of strategies to buy, develop, and distribute content to targeted audiences. In broad terms, the NRS is powered almost entirely by machine learning, using a combination of content-based filtering and collaborative filtering algorithms to recommend content. Content-based filtering relies solely on a user’s past data, which are gathered according to their interactions with the platform (e.g., viewing history, watch time, scrolling behaviour, etc.). To produce recommendations and personalise a user’s experience, these data are combined with other large and intricate data sets that contain information derived from the 15,000 film and television titles offered by Netflix worldwide, including items such as their genre, category, actors, director and release year (Wasko & Meehan, 2019, p. 10). All of this is vital to the success of Netflix, as its content is neither produced for the state nor for advertisers; it is sold directly to audiences, which means that the value is actually in the content itself (Khalil & Zayani, 2020, p. 8).

As competition for content increased with new players in the streaming sector coming on board, Netflix commenced its own original programming with the production of the television series House of Cards, Orange is the New Black and Arrested Development in 2013. Its first original feature film, Beasts of No Nation, was released in 2015. In 2019 Netflix’s original film Roma won three Academy Awards. In 2020 Netflix Original Films as a collective were the most nominated studio at the Academy Awards. As Netflix positions itself as a creator of high-quality original content, with this as its competitive edge in an increasingly competitive streaming market, it has established new production hubs in London, Madrid, New York and Toronto and recently announced it will open a global post-production hub in Mumbai. According to Kasey Moore’s (2022) analysis, by its 25th anniversary on 29 August 2022, half of the Netflix library consisted of Netflix Originals. These ‘Originals’ consist of in-house Netflix productions and programming produced by other studios with exclusive screening rights licensed by Netflix. As Netflix Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos explains in an interview with Neil Landau:

We use the word “original” to indicate the territory, where it originates. ‘Netflix originals’ is used in the US, because you can’t see them anywhere else. For us, the word “exclusive” doesn’t ring true to people. And “created by” doesn’t either (Landau, 2016).

The customer is key here, and ensuring greater engagement with content is an essential element of the Netflix customer retention strategy. Data derived from the NRS is a crucial aspect of the acquisition process when determining which products to licence, but, more importantly, it also plays a significant role in the production decision-making process. Sarandos explained the process to Tim Wu at the Sundance Film Festival:

“In practice, it’s probably a seventy-thirty mix.” But which is the seventy and which is the thirty? “Seventy is the data, and thirty is judgment,” he told me later. Then he paused, and said, “But the thirty needs to be on top, if that makes sense.” (Wu, 2015).

Wu voices his concern at the capacity for the Netflix data-driven model to disrupt the traditional media establishment:

Instead of feeding a collective identity with broadly appealing content, the streamers imagine a culture united by shared tastes rather than arbitrary time slots. Pursuing a strategy that runs counter to many of Hollywood’s most deep-seated hierarchies and norms, Netflix seeks nothing less than to reprogram Americans themselves (Wu, 2013).

This seems overly dramatic—it is difficult to argue convincingly that Netflix has overhauled how power within the entertainment industry is organised—but it is very clear that it has managed to position itself alongside other powerful players through its clever use of data-driven strategies (Jenner, 2018, p. 4). Blake Hallinan and Ted Striphas refer to this as:

[…] “algorithmic culture”: the use of computational processes to sort, classify, and hierarchize people, places, objects, and ideas, and also the habits of thought, conduct, and expression that arise in relationship to those processes (Striphas, 2012).39

It is also in line with Shoshana Zuboff’s ‘surveillance capitalism’ thesis, whereby human experience, in this case viewing popular culture, is translated into “behavioural data” and “fed into advanced manufacturing processes known as ‘machine intelligence’, and fabricated into prediction products that anticipate what you will do now, soon, and later” (2019, p. 372). Technologically targeted advertising “can easily have an impact on one’s decision-making process in the activities they choose and in political decisions (Zuboff, 2019, p. 373); surely technologically driven cultural content can be equally influential.

This shows that it is important to consider “how algorithms shape our world” (Slavin, 2011), seeing how data-driven production processes might be forms of cultural decision-making (Hallinan & Striphas, 2016, p. 119). This opens up new considerations in the popular culture–world politics continuum in IR. If Netflix is to be seen as an agent of soft power, its establishment as a global media network means it is not just producing stories Americans tell about themselves; it is also representing, reflecting and producing stories about Americans to a wide international audience as well as influencing Americans’ perceptions of ‘the other’ with its internationally diverse programming from countries around the world. I turn to the design of such a research program in the next section.

Research design

As a purveyor of popular culture on a global scale, and particularly through its recommender system, Netflix mediates representations of the world. Such a source of influence on the ideas of a mass audience is central to international relations. We must, therefore, consider Netflix an agent of power and treat such a global source of influence seriously. If we can determine the ideological basis of the worldview represented through the popular culture resources mediated by Netflix, we can identify a vital piece of the story that Netflix is telling its audiences. The usual methodological approach of the cultural branch of IR would be to provide a close reading of Netflix films and tv shows, using the techniques of the literature, film and media studies fields, to produce a study that purports to demonstrate the politics of Netflix. Such studies would be used heavily in the teaching of international relations, providing rich subjects of meaningful insight into contemporary understandings of global politics. Unfortunately, though, such studies are not widely viewed as making a legitimate contribution to knowledge by IR practitioners based on their research design, even though they rely on evidence to generate knowledge claims. This is because IR defines ‘legitimate scholarship’ as ‘proper social science’, so that research imperatives related to the replicability and objectivity of these studies is called into question. “‘Proper’ IR knowledge is said to be generated through the objective examination of data” (Shepherd, 2019, p. 34) rather than the culturally subjective close-reading methodologies employed since the ‘cultural turn’. As Steve Smith points out, this is because

[…] ontologically, the (IR) literature tends to operate in the space defined by rationalism: epistemologically, it is empiricist and, methodologically, it is positivist. Together these define ‘proper’ social science and thereby serve as the gatekeepers for what counts as legitimate scholarship (2000, p. 383).

This means that “(S)cientific is a synonym for quality in IR” (King, Keohane, & Verba, 1994, p. 7).

So, despite the decades-long aesthetic turn in IR, it still privileges positivist approaches that specify the importance of data collection, the macro, the structural. For a study of the ideological basis of Netflix’s soft power to be taken seriously, it needs to examine the world politics inherent in a large representational sample of Netflix content scientifically. Netflix Original content would be the most demonstrably representational object of the Netflix ideological base, particularly as such content is growing rapidly to constitute more than 50% of overall content. However, as a lone researcher, viewing a large number of episodes from Netflix Original series was completely outside the capacity of this study. I therefore, decided to concentrate on Netflix Original Films as the subject of research. The scholarship on popular culture and world politics usually cherry-picks overtly political films, films with a clear political message, specific genres, such as apocalyptic, dystopian films, or analyses specific films or sets of films in terms of significant world events to determine the zeitgeist. Yet, these films make up a small proportion of all the films produced and consumed by the mass public, a very small proportion of Netflix. To take seriously the causation of popular culture and how it influences the mass public to see the world in a certain way, we need to study the construction, production and reproduction of ideology on a macro scale. This is where the Digital Humanities comes in.

The creation of a comprehensive database that categorises all Netflix Original Films according to a carefully selected set of ontologies should provide the epistemological tools necessary to meet these quantitative requirements, bringing legitimacy to the study of popular culture and world politics in the IR discipline. The first step in the project consisted of identifying several proxies, including language, genre, etc., that point to a certain way of viewing the world. Data about writer, director, producer and stars is collected for all films. Ratings and maturity rating categories are included along with Netflix micro-genre descriptive categories (steamy, dark, suspenseful etc.). Reception is an important part of meaning-making, so various measures of this (Google rating, IMDb rating, etc.) are included. All of this data is collected from Netflix and various online sources before watching the film. While watching the film, data is then entered in relation to narrative elements of the film, including the protagonist, antagonist, hero, villain, setting and period. All of this data collection is reasonably straightforward and requires little understanding of world politics to provide a comprehensive data set of all Netflix Original Films. The more difficult aspect of the research was: how to determine the world politics inherent in this set of films?

While the world politics, the international relations of House of Cards, Squid Game, Beasts of No Nation, are easily discernible, how can this be objectively assessed in those films that make up the bulk of Netflix Original Films, which are less obviously political films? Leaving them out would mean discounting the considerable scholarship on the way the construction of unconscious ideologies work. The politics of these films are not flagged, they are not identified, the constitution and reconstitution of ideology are represented in such a way that audiences are not conscious that they are being ushered into a way of seeing the world through their interaction with seemingly non-political films. Leaving out those films not clearly identifiable as political would leave out the majority of films watched by the most viewers. If a study of the link between popular culture and world politics is to be taken seriously, it needs to look at the entire data set. So far, the database includes 697 films from 2015 to 2022, categorised according to 136 different genres. The only category indicating political content is Political Comedies, which includes just four films. These are the only films identified by Netflix with the term ‘political’. But how to assess the world politics in films across this disparate set of genres? To determine this, I turned to the major ideological traditions of IR—realism and liberalism.

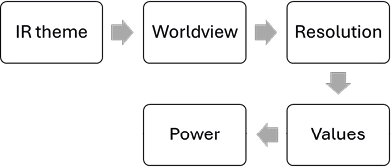

The major concerns of the International Relations discipline have been the causes of war and the conditions for peace. As most films are conflict-driven, the simple dichotomy of the key understandings of the two major competing ideologies provides a useful tool for categorising the worldview in films of any genre. Providing a simple choice between the anarchical, threatening worldview of realism and the rules-based, ordered worldview of liberalism ensures an applicable determination that is suitable for any film. Equally, by providing a simple assessment of how any conflict is resolved, either independently, as in the self-help mantra of realism, or cooperatively, as in the interdependent worldview of liberalism, as well as the compromise position if neither holds true, has a clear applicability to any film. Given the relational aspects of soft power to universalising values, these are considered while watching the film and categorised as well. Lastly, given the role of popular culture in reinforcing or contesting claims to common-sense understandings of power relations, how this is represented in the film is also assessed. This led to the development of a simple five-step ontology for data mining the international relations of all Netflix Original Films as follows:

Fig. 3.1 Five-Step Ontology—International Relations of Netflix Original Films

At present, I have watched and categorised all films from 2015 to 2018, a total of 127 films. Of these, the most prevalent themes were freedom (20) and identity (19); 61 represented the world as anarchic while 66 presented an ordered worldview. Conflict in these films was resolved independently in 64 cases, cooperatively in 60 and via compromise in three cases. Prevailing power relations were reinforced in 66 and contested in 61 films. A more intensive data-mining analysis will provide a deeper picture of how these world politics are represented in various genres, what descriptions are given to the treatments of these various themes, the identity of the main protagonists, villains, heroes etc. After mining the data for noticeable trends and patterns in relationships between proxies, a detailed in-depth qualitative analysis via a deep reading of sets of films will add considerable depth to the investigation of the intertextuality between popular culture and world politics.

As Netflix increasingly internationalises its catalogue, this comprehensive database will provide considerable evidence for analysing and comparing the world politics represented in films across several countries and regions. For example, so far there are 51 films categorised as Indian Movies available for viewing in Australia. These are predominately Hindi-language films with 45 films in Hindi and just two each in Tamil and Marathi, one in Malayalam and one in English. They are mostly dramas (19) and comedies (14) with the remainder made up of an eclectic mix of romances (eight) crime movies (six), a couple of musicals and even an LGBTQ comedy. While I have only watched the six of these released from 2015 to 2018, they overwhelmingly represented an ordered vision of world politics. As an observation, they show very high production values and present India as a modern, economically aspirational country, guided by deeply traditional values—very much the impression presented to any Western visitor of the rich culture of this rising world power. It will be interesting to see if this trend remains constant with the dramatic increase in Indian content over the last few years.

As Netflix produces more and more content, we should begin to find out how data-driven production changes the Netflix worldview over time. This leads us to the subject of soft power—the audience of these films, the Netflix subscriber. As Netflix famously uses the recommender system, the algorithm that tells them what viewers want is an essential element in production decisions. So, this study, over time, extends to the role of the audience, the role of the mass public in the acquisition and production process. We should discover if Netflix’s ‘instrumentarian’ methods are designed to cultivate “radical indifference […] a form of observation without witness” as Zuboff’s (2019, p. 379) thesis suggests, or if the subjects of power also have some agency, the causal concern missing from so much of the popular culture–world politics field. So, this project falls within Nick Srnicek’s (2017, p. 28) concept of ‘platform capitalism’ whereby, over time, it “will distinguish data (information that something happened) from knowledge (information about why something happened)” by examining any changes in the Netflix worldview intertextually with what is happening in the world politics of today. The data-driven epistemology of Digital Humanities meets the disciplinary conventions for objectivity and replicability in the positivist tradition. In this way, the use of hybrid methods in the Digital Humanities should bring some legitimacy to the study of popular culture in the discipline of International Relations.

Conclusion

This Digital Humanities project is in the preliminary phase, in which the work is concentrated on data collection. The data is complete for all Netflix Original Films from 2015 to 2018, a total of 130 films. The database is hosted on the Heurist academic data management system and this part of the project will be published on that network soon. It is very clear that, in more ways than one, this project on the global soft power of Netflix is an interesting addition to the field of Digital Humanities. While it is a comprehensive database, it also uses data-mining techniques to examine how data is used in the production of world politics itself. Such a digital method provides the tools to identify and navigate key ontological, epistemological and methodological challenges in determining the causal linkages between popular culture and world politics, showing that engaging with culture is not just a passive pastime, it is actually an act of doing politics on a global scale. Many scholars consider that film production and consumption have a powerful capacity to shape national identity (see Edensor, 2002; Dittmer, 2005; Philpott, 2010) and also have prominent roles in determining attitudes towards the foreign ‘other’, whether that be through the construction of the ‘friendly other’ or the ‘enemy other’.

In a relatively short period of time, Netflix built on existing business models from movie studios to pay TV, exploited the affordances of data-driven narrowcasting, and ultimately altered the way media is consumed (Khalil & Zayani, 2020, p. 8).

Netflix quickly recognised binge-watching as a way to promote itself and its original content, and it released new content on the same day in all its territories, establishing itself as a transnational broadcaster. Netflix is a driving force in changing how popular culture is organised and how viewing is structured for a global audience (Jenner, 2018, p. 4). There is no denying that Netflix is a commanding agent of soft power.

In global politics, the resources that produce soft power arise in large part from the values an organisation or country expresses in its culture; popular culture clearly constitutes an important source of the ideas that people use to judge the world and their place in it. As ideas shape actions, then this comprehensive database project can provide a pathway to show the linkages between popular culture and political actions in international relations. This will join:

Weber, Nexon and Neumann, and others in viewing novels, films, and the like as partly constituting world politics, because the experiences those artifacts induce can produce and reproduce ideas about world politics that even informed people believe (Daniel & Musgrave, 2017, p. 21).

While no claim is being made that films allow a reversal of power relations, they do allow audiences to formulate ideas and conduct speech acts within a discourse of power, potentially subverting power structures if a large enough proportion of the mass public is eventually hailed into a particular understanding of the processes that substantiate power on a global scale. According to Nye, “Those who deny the importance of soft power are like people who do not understand the power of seduction” (2004, p. 8.).

It becomes increasingly clear that developing novel methodologies and theoretical approaches for dealing with the changing dynamics of international power relations is imperative, especially as complex economic interdependence deepens and the power of non-state actors grows. By using hybrid Digital Humanities epistemologies in analysing the political trends in this audience-driven set of popular films, this research project will contribute to a better understanding of how power works through the production and normalisation of meaning and the processes of constructing the stories that are central to the study of power in global politics. By developing a fuller understanding of the constitutive production of hegemonic power on a global scale, this project should contribute to the evidence-based conventions of knowledge production in the International Relations discipline and extend our understanding of how hegemonic power is produced and maintained on a global scale.

Works Cited

Barthes, R. (2009). Mythologies. Vintage Classics.

Bruner, S. (2019). I’m so bored with the canon: Removing the qualifier “popular” from our cultures. The Popular Culture Studies Journal 7(1), 6–16.

Cox, R. (1983). Gramsci, hegemony and International Relations: An essay in method, Millennium 12(2), 162–175. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298830120020701

Furman D.J. & Musgrave, P. (2017). Synthetic experiences: How popular culture matters for images of International Relations. International Studies Quarterly 61, 503–516. https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqx053

Demianyk, G. (2017, February 12). Ken Loach damns government over child refugees after ‘I Daniel Blake’ BAFTA Win. Huffington Post UK. https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/ken-loach-bafta-child-refugees-i-daniel-blake_uk_58a0d95ae4b094a129ec2a20

Dittmer, J. (2005). Captain America’s empire: Reflections on identity, popular culture and geopolitics. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95 (3), 626–643. https://www.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00478.x

Dittmer, J. (2010). Popular Culture, Geopolitics and Identity. Rowman and Littlefield.

Edensor, T. (2002). National Identity, Popular Culture and Everyday Life, Berg. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003086178

Galloway, A. (2006). Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture. University of Minnesota Press.

Geertz, C. (1973). The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. Basic Books.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks. Lawrence and Wishart.

Grayson, K., Davies, M., & Philpott, S. (2009). Pop goes IR? Researching the popular culture-world politics continuum. Politics 29(3), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9256.2009.01351.x

Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. Sage Publications & Open University.

Hallinan, B., & Striphas, T. (2016). Recommended for you: The Netflix Prize and the production of algorithmic culture. New Media and Society 18(1), 17–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814538646

Hartley, J. (1994). The Politics of Pictures. Psychology Press.

Jenner, M. (2018). Netflix and the Re-invention of Television. Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94316-9

Khalil, J., & Zayani, M. (2020). De-territorialized digital capitalism and the predicament of the nation-state: Netflix in Arabia. Media, Culture and Society, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720932505

King, G., Keohane, R., & Verba, S. (1994). Designing Social Inquiry: Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton University Press.

Landau, N. (2016). TV Outside the Box: Trailblazing in the Digital Television Revolution. Focal Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315694481

Moore, K. (2022). Netflix Original Now Make Up 50% of Overall US Library.What’s On Netflix. whats-on-netflix.com

Netflix. (2023). ‘About’. https://about.netflix.com/en

Nexon, D., & Neuman, I. (Eds). (2006). Harry Potter and International Relations. Rowman and Littlefield.

Nye, J. (1990). Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. Basic Books.

Nye, J. (2004). Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. Public Affairs. https://doi.org/10.2307/1148580

Nye, J. (2011). The Future of Power. Public Affairs.

Nye, J. (2017). Soft power: The origins and political progress of a concept. Palgrave Communications 3, 17008. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2017.8

Onuf, N. (1989). World of Our Making: Rule and Rule in Social Theory and International Relations. University of South Carolina Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203096710

Pajkovic, N. (2022). Algorithms and taste-making: Exposing the Netflix recommender system’s operational logics. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211014464

Philpott, S. (2010). Is anyone watching? War, cinema and bearing witness. Cambridge Review of International Affairs 23(2), 325–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571003735378

Reinherd, C.L. (2019). Introduction: Why popular culture matters. The Popular Culture Studies Journal 7(1), 1–5.

Reus-Smith, C. (1999). The Moral Purpose of the State. Princeton University Press.

Shepherd, L. (2019). Authors and authenticity: Knowledge, representation and research in contemporary world politics. In C. Hamilton and L. Shepherd (Eds). Understanding Popular Culture and World Politics in the Digital Age. Routledge.

Slavin, K. (2011). How algorithms shape our world. TEDGlobal. http://www.ted.com/ talks/kevin_slavin_how_algorithms_shape_our_world.html

Smith, S. (2000). The discipline of International Relations: Still an American social science? British Journal of Politics and International Relations 2(3), 374–402.

Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform Capitalism. Polity Press.

Striphas, T. (2012). What is an algorithm? Culture Digitally. http://culturedigitally. org/2012/02/what-is-an-algorithm/

Wasko, J., & Meehan, E. (Eds). (2019). A Companion to Television. (2e). Wiley-Blackwell.

Weber, C. (2005). International Relations Theory: A Critical Introduction. Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003008644

Weldes, J. (2001). Globalisation is science fiction. Millennium: Journal of International Studies 30. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298010300030201

Weldes, J. (2006). High politics and low data: Globalization discourses and popular culture. In D. Yanow & P. Schwartz-Shea (Eds). Interpretation and Method: Empirical Research Methods and the Interpretive Turn. (pp. 176–186). M.E. Sharpe.

Weldes, J. (Ed.). (2003). To Seek Out New Worlds: Exploring Links between Science Fiction and World Politics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Weldes, J., & Rowley, C. (Eds). (2015). So, how does popular culture relate to global politics? E-International Relations. https://www.e-ir.info/2015/04/29/so-how-does-popular-culture-relate-to-world-politics/

Wendt, A. (1992). Social Theory of International Relations. Cambridge University Press.

Wu, T. (2013). Netflix’s war on mass culture. The New Republic. https://newrepublic.com/article/115687/netflixs-war-mass-culture

Wu, T. (2015, January 27). Netflix’s secret special algorithm is a human. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/business/currency/hollywoods-big-data-big-deal

Zahran, G., & Ramos, L. (2010). From hegemony to soft power: Implications of a conceptual change. In I. Pamar & M. Cox (Eds). Soft Power and US Foreign Policy: Theoretical, Historical and Contemporary Perspectives. Taylor and Francis.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Profile Books.