7. ‘Aboutness’ and semantic knowledge: A corpus-driven analysis of Yajnavalkya Smriti on the status and rights of women

Gopa Nayak and Navreet Kaur Rana

© 2024 Gopa Nayak and Navreet Kaur Rana, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0423.07

Abstract

This essay establishes the use of computational methods to study the semantics of a historical corpus compiled from the ancient Indian text of Yajnavalkya Smriti. Although the use of corpora has been extended to the study of computational semantics, in addition to grammar usage and patterns of language, they have mostly been limited to word-sense disambiguation, structural disambiguation or analysing a semantic space in terms of calculating semantic distances and determining relations between words within a corpus. This study adopts the use of computational semantics on ‘aboutness’ and ‘knowledge-free analysis’ within a limited aspect of ‘aboutness’ based on the methodology of Philips (1985).

The text-only corpus of this study comprises 36,000 words of verses of the Yajnavalkya Smriti text translated by Vidyarnava (1918; 2010) from the original Sanskrit to English. In this study, ‘aboutness’ and ‘knowledge-free analysis’ aim to find the semantics of collocations and bring out bias-free information on the inheritance rights and the status of women in ancient India as described in the text. The application of the ubiquitous yet rarely applied concept of ‘aboutness’ is used to derive semantics in an unprecedented manner from an ancient historical text. This research on ‘aboutness’, which has seldom been used in computational semantics (Yablo, 2014), opens up avenues for further research on corpus analysis for extracting semantic knowledge from ancient texts to minimise knowledge bias.

Keywords

Corpus linguistics; Yajnavalkya Smriti; ‘Aboutness’; semantic knowledge.

Introduction: Digital Humanities and corpus linguistics

Corpus linguistics involves the study of digitised text with the help of computational tools and digital methodologies involving concordances and software tools within the broader field of Digital Humanities (DH, hereafter) (Bjork, 2012; Hockey, 2000; Kirschenbaum, 2016; Schreibman, 2012; Svensson, 2016). Corpus linguistics had existed much earlier than the inception of DH, but DH emerged as a superset that accommodated lesser-studied or relatively later-developed disciplines. While corpus linguistics is often considered the basis of quantitative research, DH has the potential to uncover both qualitative and quantitative features of a corpus. Building a corpus and analysing it computationally is fundamentally a DH project. As Hockey (2000) explains, DH involves applications of tools and techniques of computing to research on subjects that are loosely defined as “the humanities”, or in British English “the arts”. Digital Humanities are thus computer-supported humanities (Simanowski, 2016).

A corpus is essentially a collection of natural language consisting of texts, and/or transcriptions of speech or signs, constructed with a specific purpose. A corpus may contain a text in one language, as in a monolingual corpus, or in multiple languages, called multilingual corpora. A diachronic corpus, on the other hand, is a corpus containing texts from different periods and is used to study the progress or change in language.

The corpus under investigation in this study is a text-only corpus which is a classic scripture named Yajnavalkya Smriti, originally written in Sanskrit by the sage Yajnavalkya, now translated into English. It contains a substantial amount of Sanskrit vocabulary. It is a historical corpus and is considered closed as it cannot evolve. It is estimated to have been written around the third to the fifth century CE. The corpus designed for this study has been collected from the scanned scripture available in digitised form at a web portal that supports archived documents. The digital format is an English translation of the 1010 verses, including a commentary along with a detailed glossary. However, the corpus used here for analysis consists of verses only from the edited version of the text translated into English by Rai Bahadur Srisa Chandra Vidyarnava with commentary and notes (1918; 2010).53 Although this corpus is compiled from an ancient text and may therefore be considered a historical corpus, the focus is on the semantic knowledge of the corpus rather than semantic change (McGillivray, Hengchen, Lähteenoja, Palma, & Vatri, 2019). On the other hand, this research draws on the digitised version of the translated text in English. The digital version opened up the use of computational tools in analysing this ancient text (Allan, & Robinson, 2011; deGruyter. Lamoureux, & Camus, 2024; Martin, Norén, Mähler, Marklund, & Martin, 2024).

‘Knowledge-free analysis’ and ‘Aboutness’

This study draws on the concepts of ‘knowledge-free analysis’ and ‘aboutness’ as discussed at length by Martin Phillips in his book titled Aspects of Text Structure: An Investigation of the Lexical Organisation of Text (1985). The book elaborates on knowledge-free analysis of non-linear lexical structures, also called macrostructures, through language patterning using graphs. However, for our study, we restrict ourselves to a limited aspect of ‘aboutness’ in order to find the semantics of certain collocations from our corpus. Phillips states that the reader has a psychological sensation that a book is ‘about’ something and he argues that this ‘aboutness’ is not adequately accounted for in any kind of linguistics analysis (Phillips, 1985, p. vii). In his study, Phillips tried to capture ‘aboutness’ by dropping all non-functional words and thus understand the ‘aboutness’ in the literal meaning of words in the text. These texts included five science books and novels by Virginia Woolf, Graham Greene, and Christopher Evan. The literal meaning of a word is contextual and is always associated with the neighbourhood of the node word. Quoting Phillips, “the crucial point concerning aboutness is that it is a type of meaning arising from the global structuring of text” (Phillips, 1985, p. 30). Following his research hypothesis:

[…] knowledge-free analysis of the terms in a text […] will reveal evidence of systematic and large-scale patterning which can be interpreted as contributing to the semantic structure of text and hence as constituting a major device through which the notion of content arises (Phillips, 1985, p. 26).

‘Aboutness’ as a concept was expanded by Yablo (2014) as “the relation that meaningful items bear to whatever it is that they are on or of or that they address or concern” (Yablo, 2014, p. 1). Bruza, Song and Wong (2000) sought to define ‘aboutness’ in terms of a model of Information Retrieval (IR), arguing for a linguistic analysis of a text in line with Hutchins (1977) and explaining aboutness under a semantic network. Although the concept of ‘aboutness’ was studied by Yablo (2014) and Bruza, Song and Wong (2000), it was Phillips’ model of aboutness in terms of deciphering the meaning of the text that has been widely adopted in corpus-based research on the Fukushima War (Kalashnikova, 2023), the COVID-19 lockdown (Herat, 2022) and social tagging (Kehoe & Gee, 2011) among others. A “knowledge-free analysis of text […] contributing to the semantic structure of text” (Phillips, 198, p. 26) is also the premise on which the methodology of this study is based.

Since the concept of ‘aboutness’ is used in this study to derive meaning, the concepts of semantic prosody and semantic preference deserve attention. The relationship between semantic prosody and computational methods was revealed by Louw (1993) and subsequently, in a later study, semantic prosody was defined as “a form of meaning which is established through the proximity of a consistent series of collocates” (Louw, 2000, p. 57). Hunston (2002, p. 142) explains that “semantic prosody can be observed only by looking at a large number of instances of a word or phrase because it relies on the typical use of a word or phrase”. Sinclair is of the opinion that semantic prosody refers to the usage of a word that “gives an impression of an attitudinal or pragmatic meaning” (Sinclair, 1999). Kalashnikova (2023) along the lines of Sinclair (1998) and Stubbs (2009), confirms that semantic prosody reveals conscious views or intended actions. Thus, semantic prosody could describe the pragmatic or semantic sense that arises when a keyword and its specific collocates are in the vicinity of each other. For instance: “bad weather” and “bad company” derive a negative connotation whenever they occur together. The word “bad” itself has a negative sense to it, but when it is used in the phrase “Not bad at all”, it indicates positivity. Such is the impact of the company words keep! Most of the time, semantic preference and semantic prosody have been used to describe the same phenomenon, but at other times the two are considered different but closely related. Therefore, the need for precise definitions of the two terms arises. Partington (2004) has described the difference between the two in his claim that semantic preference and semantic prosody have different operating scopes. While ‘semantic preference’ relates the node item to another item from a particular semantic set, ‘semantic prosody’ can affect wider stretches of text. ‘Semantic preference’ can be viewed as a feature of collocates, while ‘semantic prosody’ is a feature of the node word. Partington (2004, p. 151) also adds that these two terms interact. While semantic prosody “dictates the general environment which constrains the preferential choices of the node item”, semantic preference “contributes powerfully to building semantic prosody”.

The relevance of semantic preference and semantic prosody to this discussion is that we have limited our computational study to obtaining collocates only, and no other concepts, because we want to derive the most pristine semantic sense out of the text in order to justify a ‘knowledge-free analysis’. Applying other concepts like semantic prosody and semantic preferences would have given us information about the possible usage of a particular word or characteristic features of collocates, both of which are not the intent behind this computational exercise. Also, collocates, in this case, are the first level of analysis and by applying semantic preference and semantic prosody we run the risk of introducing a bias or reducing the degree of ‘knowledge-free’ analysis.

The following section includes the source of corpus, the process of making the corpus, and the methodology to comprehend and draw conclusions on the status and rights of women from the text.

Design of the corpus

Yajnavalkya Smriti along with the Manu Smriti are widely acknowledged as the texts that describe the codes of conduct, moral duties and statecraft in the Indian subcontinent in ancient times (Bhat, 2006; Bhattacharji, 1991; Tomy, 2019; Tharakan & Tharakan, 1975). While Manu Smriti has been widely read and researched, Yajnavalkya Smriti remains less so. Yajnavalkya Smriti is less popular as a reference in the legal history of India compared to Manu Smriti, a comprehensive document on the fundamental religious and philosophical conventions observed by the people of India. Manu Smriti, or the ‘Code of Manu’, which has made a lasting impact in India, has been studied even in modern India for the ordinances and decrees it contains relating to the law. It lists the obligations of the kings and rules of their administration of justice based on Dharma. Yajnavalkya Smriti is next to the Manu Smriti in authority and recognition. The codes mentioned in Yajnavalkya Smriti are largely based on Manu Smriti but are more liberal on certain matters than Manu Smriti, particularly on women’s right to property, inheritance and criminal penalty (Thukar, & Thakur, 1930). Justice M. Rama Jois (2004) in his book, Legal and Constitutional History of India, argues that Yajnavalkya Smriti deals exhaustively with subjects like the creation of valid documents, the law of mortgages, hypothecation, partnership and joint ventures and emphasises that Yajnavalkya Smriti is scientific and more methodical than Manu Smriti.

Robert Lingat, a French-born academic and legal scholar whose area of practice was classical Hindu Law, in his book The Classical Law of India (translated by J. Duncan M Derrett) (Lingat, 1973), also states that the text in Yajnavalkya Smriti is closer to legal philosophy and transitions away from being Dharma speculations found in earlier Dharma-related texts such as the Vedas, Upanishads and Puranas and focusses more on the practices and not on the moral or religious aspects of these practices. Not only as the less studied scripture, but as a liberal document Yajnavalkya Smriti remains worth exploring to understand the historical rights and privileges of women mentioned in this ancient text, especially when this document is referred to even in 21st-century India for reference in the legal field (Darshini, 2001; Deodhar, 2010; Tharakan & Tharakan, 1975).

While the rationale for using the text of Yajnavalkya Smriti lies in the relevance of the text to the interpretation of the legal system in India even today, the justification for using the translation (1918) can be explained only because this remains the only translation of the ancient text available in English. The digitised version of the translation (2010) available on the University of Toronto website also adds to the reliability and validity of the text. This translated text has been the source of reference for recent publications in different fields of study by scholars (Acevedo, 2013; Ambedkar, 2020; Kiss, 2019; Nongbri, 2018).

The entire text of this ancient scripture consists of three chapters, namely Achara Adhyaya (meaning ‘proper conduct’ and consisting of 368 verses), Vyavahara Adhyaya (meaning ‘legal procedures’ and consisting of 307 verses) and Prayashchitta Adhyaya (meaning ‘penance’ and consisting of 335 verses). There are 1010 verses in all the three chapters. The available text is comprehensive and comprises the verses, detailed commentary on these verses called The Mitakshara, and an exhaustive glossary authored by Balambhatta. For this study, the verses without commentary or glossary were chosen. We chose only the verses as part of our corpus because the commentary and glossary, if included in the corpus, would have affected the statistical analysis and in turn would have influenced the semantic findings. To keep the semantic discoveries unbiased, the text had to be scrutinised with a neutral perspective. Thus, although the entire text was 1894 pages, it was reduced to 127 pages, which is approximately 6.7% of the original text in this study.

Methodology

The methodology adopted for this study focuses on the notion of the context and ‘aboutness’ and will be implemented to examine the corpus of Yajnavalkya Smriti to be discussed in the following section. The methodology applied here is independent of any natural language understanding or knowledge representation system and thus supports knowledge-free analysis. The text can be interpreted as per the readers’ understanding but interpretations vary and can be prejudiced.

The study aims to bring forward an analysis based solely on the findings from the Antconc (3.5.8) concordancer tool instead of intuition or experience. Paul Doyle (2005), in a conference proceeding, interpreted the term ‘knowledge-free analysis’ adopted by Phillips (1985) as an analysis that did not depend on semantic notions originating with the introspection of the researcher. Rather it dealt empirically with the “syntagmatic patterning of the textual substance” itself (Phillips, 1985, p. 26). Assuming that the meaning of a content word, which he has referred to as a node, can be established by the company it keeps, Phillips analysed the collocations of the node word inside a span of four words on either side, dropped all non-function words and attempted to group all such nodes on the basis of these collocations, and displays this distributional network by a statistical technique known as cluster analysis.54

Extrapolating from this method and attempting to derive wider notions about the situation of women in ancient India as per the text, the heuristics that are applied in this study examine the collocation of the words through the target words, “women”, “man”, “wife” and “husband”, with the help of a corpus analyser tool, AntConc (version 3.5.8). To continue with the knowledge-free analysis, it is necessary to find out the collocates of the target words. The neighbourhood of the target words will help to extract a semantic sense out of collocates.

The significance of the concept of collocation has long been recognised in theoretical linguistics. It was first brought to light by Firth in 1957 (Bartsch, & Evert, 2014). The study of collocation has evolved in the form of semantic approach, lexical approach (Halliday, 1966; Sinclair, 1966), and the integrated approach (Mitchell, 1971). The study of collocation forms an integral part of corpus-driven approaches and has been widely adopted (Farghal & Obeidat, 1995; Ahrens & Jiang, 2020). In this study, a corpus-based approach is adopted to uncover the status and rights of women in ancient India through a semantic analysis. To derive an absolute semantic sense, word clusters of the normalised collocates are considered. The subsequent section discusses the relevant collocates and their clusters. Once the collocations are determined, and non-functional collocates are dropped, the remaining collocates will be analysed semantically. For clarity, the relevant verses are also quoted alongside the collocates.

In relation to the FAIR principles, i.e., Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (Wilkinson, Dumontier, Aalbersberg, Appleton, Axton, Baak, & Mons, 2016) as they apply to the development of software, the focus of this research was on the use of software rather than its development. However, this research created a corpus with a clear research intent (Barker, Chue Hong, Katz, Lamprecht, Martinez-Ortiz, Psomopoulos, & Honeyman, 2022). The AntConc software used in this research is a freeware corpus analysis toolkit for concordancing and text analysis developed by Laurence Anthony, a professor at Waseda University in Japan. Anthony (2009) explains that this is a standalone, multiplatform software tool developed by him in collaboration with linguists to extract data from digital texts. This is the first step in interpreting the text. The unique feature of this toolkit is that it works effectively with files made in Microsoft Word and accepts character sets and token definitions making it easier to use, especially for analysing a historical text. Anthony (2013) reiterates the effectiveness of AntConc as a tool for corpus linguists to analyse texts, and demonstrates its popularity. Bjork (2012) claims that the use of AntConc for extracting data from a corpus is effective. Thus, the AntConc software follows the FAIR principles since it is accessible as free software and has been used by researchers other than the team that developed it.

The CARE principles, including Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics (Carroll, Herczog, Hudson, Russell, & Stall, 2021) were also taken into consideration in this research on an ancient text. While collective benefit was embedded in this research, which aims to uncover knowledge-free semantics of an ancient text, the ‘authority to control’ feature does not apply. Responsibility and ethics were guiding principles. Personal biases that could influence the outcome of the research were controlled by using this software.

Keyword selection criteria

Drawing inference from the research on keyword analysis (Baker, 2009; Kehoe & Gee, 2011; Scott, 1997), this study conducted the keyword selection and included eight relevant keywords: “woman” / “women”, “husband” / “husbands”, “wife” / “wives”, “man” / “men” (the name of a woman or man as common nouns are not present in the text owing to its nature as a treatise on law). The concordance and collocates are analysed in their respective clusters.

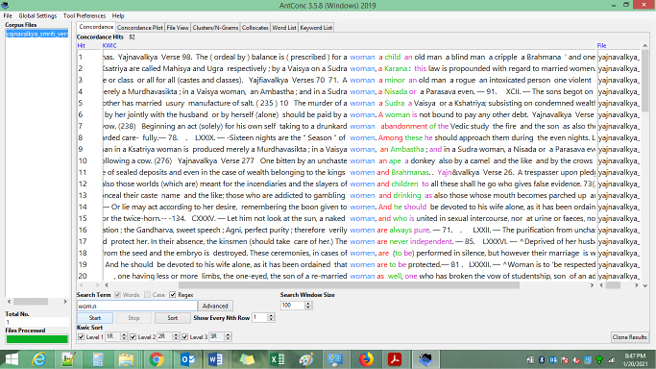

The total collocations of the regular expression55 ‘wom.n’ (this regular expression will search for both woman and women) are 82 in number (refer to Figure 7.1). After normalisation, dropping non-functional words, and considering only relevant collocates, we came across the following:

- Collocates of woman/women: stridhana, property, debt, paid by, childless women, never independent, menstruating.

- Collocates of man/men: intercourse, fined.

- Collocates of husband: respected by, devoted, wife alone.

- Collocates of husbands: No relevant collocates of ‘husbands’ were found in the context of a wife. The collocates spoke about the general conduct of all wives towards their husbands. However, this was not the case with the keyword “wives”.

- Collocates of wives: eldest, others.

- Collocates of wife: loving, same class, unchaste, deprived, devoted to wife alone.

Fig. 7.1 Concordance of regular expression ‘wom.n’.

Analysis of findings

This section describes each collocate along with the cluster.

Collocates of woman/women

Stridhana is one collocate of the regular expression ‘wom.n’ referring to the ownership rights of women for any tangible property. Stridhana is a compound word formed of two words: stree, meaning woman, and dhana, meaning money/wealth. In this case, money equates to the tangible property or assets that a woman owns. In the corpus, stridhana is suitably defined along with the ownership rights in the verse 143 of the second chapter, the Vyavhara Adhyaya. The English translation of the verse defines stridhana as whatever is presented to the woman by her parents or siblings during her wedding. In the subsequent verses (verse 144(2) of Vyavhara Adhyaya), it is said that if the women passes away without issue, her kinsmen can take the property (the stridhana is demonstrated by “it” and the woman as “she”). Verse 145 of Vyavhara Adhyaya further goes on to explain the inheritance rules if a woman is childless (childless being one of the collocates of woman). The relevant cluster for the collocate is “The property of a childless woman”. The verse explains that if the woman is childless, the property goes to her husband. This is also indicative of the ownership rights of the women.

Verse 143.

What was given (to a woman) by the father the mother the husband

or a brother or was received by her at the nuptial fire as also

that which was presented to her on her husband’s marriage to another wife

or any other is denominated (stridhana) a woman’s property.”

Verse 144.

If she pass away without issue her kinsmen should take it.

Verse 145.

The property of a childless woman married according to any of the

four forms such as the Brahma and the others goes to her husband; it

will go to her daughters if she leave progeny; and in other forms of

marriage it goes to her parents.

The next collocate of woman is “debt”, which has been used multiple times and brings to light the fact that a woman could borrow money, and under what circumstances she is liable to pay it back. The cluster, “A debt agreed to by her” of verse 49 of Vyavahara Adhyaya is sufficient to demonstrate that a woman could borrow money as men could, although it is not very clear from this cluster whether women could borrow money for their own needs or only to meet the requirements of their family. Other clusters extracted from the same verse throw more light on this fact: the cluster “which was contracted by her jointly with the husband” and “or by herself (alone)”. The cluster “which (debt) was contracted by her jointly with the husband” clearly states that the husband and wife could take a debt together. It also indicates that “woman” and “man” can jointly take up financial responsibility. The other cluster “or by herself (alone)” implies the independence and equality women enjoyed in the ancient era, as they could take independent decisions regarding financial responsibilities. The cluster “paid by a woman” also establishes this fact.

Although the collocates above point towards the financial liberty and responsibility women enjoyed, there is corpus evidence that proves that women were considered to be dependent and impure during menstruation. Verse 85 of Achara Adhyaya indicates that women are always dependent on their kinsmen––father, husband and sons. The cluster collocate is “never independent”. Similarly, a menstruating woman is considered impure according to verse 168, Achara Adhyaya, which suggests avoiding food touched by menstruating women.

Verse 49.

A debt agreed to by her or which was contracted by

her jointly with the husband or by herself (alone) should be

paid by a woman. A woman is not bound to pay any

other debt.

Verse 85

When a maiden, her father; when

married, her husband; and when old, her sons, should

protect her. In their absence, the kinsmen (should take

care of her.) The women are never independent. —

Verse 168.

What has been touched by a menstruating woman, or what has been publicly offered, food

given by one who is not the owner, or what has been

smelt by a cow, or the leavings of birds, or what has

been wilfully touched with feet (these foods) let him

avoid.

Collocates of man/men

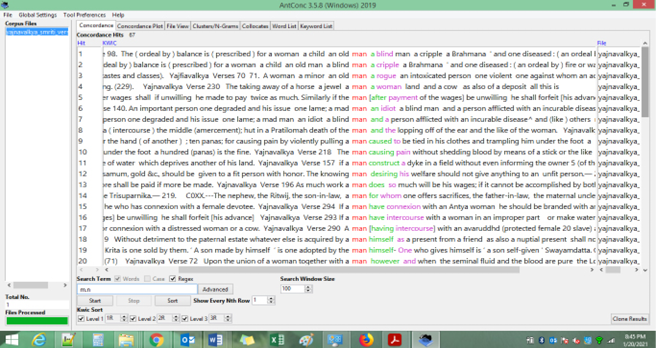

There are 67 concordances of man and men (Refer to Figure 7.2) searched using the regular expression ‘<space>m.n<space>’, but with relevance to women or with respect to men’s duties towards women, the collocate “intercourse” is relevant. It speaks about “unnatural” intercourse as a punishable offence and deems that the man practising it should be appropriately fined.

“Intercourse”, “improper part” and “fined” come under the same cluster. The original verse recommended a fine of 24 panas to be imposed on a man who had intercourse with a woman in an “improper” way (verse 293).

Verse 293.

If a man have intercourse with a woman in an improper part

or make water or void excretion he shall be fined twenty-four panas

so also he who has connexion with a female devotee.

Fig. 7.2 Concordance of regular expression ‘m.n’.

Collocates of wife

“Wife loving” is a collocate that draws our attention towards the conduct of a husband towards his wife. The cluster worth considering is “He should be wife loving” or “It is […] expected of a husband to be wife loving” (Achara Adhyaya, verse 121).

“Same class” is a collocate of wife and the entire cluster is “wife of same class”. This is evidence enough that marriages across castes (the term class is used for the four varnas, Brahmin, Khatriyas, Vaishyas and Shudras, in the text) was a norm at that time (Achara Adhyaya, verse 62).

“Unchaste wife” as a collocate refers to the conduct of a wife. The translated verse (Achara Adhayaya, verse 70) states that an unchaste wife should be deprived of all authority and should be unadorned. “Deprived of authority” is a collocate of wife. The way that the ancient text has described the duties of both men and women is also evidence of their equal status in ancient India.

Similarly, the collocates of wives, “eldest” and “others”, clearly indicate polygamy. The cluster is “religious duties are to be performed by the eldest and not by the others”.

Verse 121.

He should be wife-loving, pure, maintaining the dependent, and be engaged in the Sraddha, and

the ceremonies, and with the Mantra “Namah” he should

perform the five sacrifices.

Verse 62.

In marrying a girl of the same class the

hand should be taken, the Ksatriya girl should take

hold of an arrow, the Vaisya should hold a goad, in the

marriage with one of higher class.

Verse 70.

The unchaste wife should he deprived of

authority, should he unadorned, allowed food barely

sufficient to sustain her body, rebuked, and let sleep on

low bed, and thus allowed to dwell.

Verse 88.

When there exists a wife of the

same class (savarna), religious works are not to be performed by a wife of another class. When there are

wives of the same class, then religious duties are to be

performed by the eldest and not by the others.

Collocates of husband

Another cluster which included “husband” as a keyword in the context of “woman” is “to be respected by her husband” (Achara Adhyaya, verse 82). “Respected by” and “her husband” form the collocates of husband and are self-explanatory. Similarly, “devoted to” and “wife alone” form the cluster of the same sentence and are collocates of “husband”, and they are indicative of the fact that a husband is also expected to be devoted to his wife (Achara Adhyaya, verse 81).

Verse 81.

Or lie may act according to her desire,

remembering the boon given to women. And he should

be devoted to his wife alone, as it has been ordained

that women are to be protected.

Verse 82.

Woman is to be respected by her husband, brother, father, kindred, (Jnati), mother-in-law, father-in-law, husband’s younger brother, and the bandhus, with ornaments, clothes and food.

Discussion

Two important concepts have been discussed in this chapter. The first is ‘knowledge-free analysis’ and the notion of ‘aboutness’, and the second is the revelations about the status and rights of women as described in the Yajnavalkya Smriti. The study was based on the rationale that ‘aboutness’ can be adopted as a methodology to extract semantic knowledge from a given text. This is based on established research and thus can inferentially be applied to discover an unbiased, neutral viewpoint about any given text. While it is inevitable that there will not be a final interpretation of any text, approaching the same text with the concept of ‘aboutness’ has the potential to discover unknown or lesser-known meanings of texts. The less well-known the text is, the lower is the degree of ‘aboutness’, thus reducing the chances of any bias that can creep in when deriving semantic sense from the text.

The semantic knowledge derived from this study through the knowledge-free analysis of the corpus, developed from the translated text in English of the original Sanskrit, revealed details concerning the rights and status of women in ancient India. Although women appeared to be dependent on their kinsmen, such as fathers and husbands, they had ownership rights or stridhana. These rights were gained through the gifts a woman received from her parents and siblings, yet these rights were passed on to her husband if she died without a daughter. Otherwise, the property of a mother is passed on to the daughter. These ownership rights of women, prevalent in ancient India, were not granted to women until recently in 21st-century India. The daughter’s equal right to inherit their parent’s property was passed only as recently as 2005.

Women, according to this text, could not only pass on these ownership rights but they enjoyed financial liberty and were expected to carry the burden of economic liability and could borrow money. In addition, a detailed description of the duties and responsibilities of both men and women in social institutions such as family and marriage are provided in the text. These descriptions reflect the status accorded to women in ancient India.

In the context of marriage, love and loyalty formed the bond between men and women. Unlike the practices prevalent in modern India, where caste remains an important criterion for arranged marriages, the text shows that ancient Indians married across castes. Explicit instruction on the practice of conjugal relationships and punishment for men indulging in “improper” sexual intercourse reflect the respect accorded to women. Women also partook of religious activities and sacrifices alongside their husbands and were given respect.

There is some evidence to suggest that feminine reproductive processes such as menstruation were not viewed without prejudice, and there are instances when they were considered impure.

Conclusions

The conflicting discoveries from this analysis suggest that assessing a text computationally nullifies the probability of introspection, thus making this a knowledge-free analysis. The conflict reflected in the computational analysis adopted in this study could have been compromised by human intervention or bias. However, computational analysis with a knowledge-free approach has led to an objective exposition of the text.

This study shows that computational methods, when applied to semantic outcomes, produce unbiased results. This contradicts the common view that computational methods should only be employed in certain research areas, which excludes semantics because of their complexity (Jenset & McGillivray, 2017). However, the results of this research reaffirm McGillivray’s (2020) view that the combination of computational modelling of semantic analysis with linguistic intuition can drive a methodological shift in research on historical texts. This can open new avenues for interdisciplinary research in corpus linguistics. This study could act as a trigger for research on other ancient texts that are digitalised, leading them to be analysed in a new light using the lens of corpus linguistics. It is past time to study ancient texts to find a new perspective or to reaffirm the established one with knowledge-free analysis. The corpus compiled for this research can pave the way for new research examining it from many different angles including social, economic and political critiques involving caste-based systems, laws, penance, conjugal laws and inheritance to name a few.

The findings of this research do not in any way attempt to make other approaches to the critical analysis of ancient literature redundant. On the other hand, it provides an effective alternative to critically analyse texts, particularly those that are large in volume. Moreover, this research shows that the focus of the research when computational coding is used can make the analysis objective and less time-consuming. As ancient literature becomes digitised, linguistic research can exploit computational tools to unearth evidence effectively, with benefits in terms of the time spent and the volume of material covered.

Works Cited

Acevedo, D.D. (2013). Developments in Hindu law from the colonial to the present. Religion Compass 7(7), 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/rec3.12052

Ahrens, K., & Jiang, M. (2020). Source domain verification using corpus-based tools. Metaphor and Symbol 35(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926488.2020.1712783

Allan, K., & Robinson, J.A. (Eds). (2011). Current Methods in Historical Semantics (Vol. 73). Walter de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110252903

Ambedkar, B.R. (2020). Beef, Brahmins, and Broken Men: An Annotated Critical Selection from the Untouchables. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/ambe19584-008

Anthony, L. (2009). Issues in the design and development of software tools for corpus studies: The case for collaboration. In P. Baker (Ed.). Contemporary Corpus Linguistics. (pp. 87–104). Continuum Press.

Anthony, L. (2012). AntConc (Version 3.3.5) [Computer Software]. Waseda University. http://www.antlab.sci.waseda.ac.jp/

Anthony, L. (2013). A critical look at software tools in corpus linguistics. Linguistic Research 30(2), 141–161.

Barker, M., Chue Hong, N.P., Katz, D.S., Lamprecht, A.L., Martinez-Ortiz, C., Psomopoulos, F., and Honeyman, T. (2022). Introducing the FAIR principles for research software. Scientific Data 9(1), 622. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01710-x

Bartsch, S., & Evert, S. (2014). Towards a Firthian notion of collocation. Vernetzungsstrategien Zugriffsstrukturen und automatisch ermittelte Angaben in Internetwörterbüchern 2(1), 48–61.

Bhat, P.I. (2006). Protection against unjust enrichment and undeserved misery as the essence property right jurisprudence in “Mitakshara”. Journal of the Indian Law Institute 48(2), 155–174.

Bhattacharji, S. (1991). Economic rights of ancient Indian Women. Economic and Political Weekly 26(9/10), 507–512.

Bjork, O. (2012). Digital Humanities and the first-year writing course. In B.D. Hirsch (Ed.). Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles and Politics. Open Book Publishers.

Bruza, P.D., Song, D.W., & Wong, K.F. (2000). Aboutness from a common-sense perspective. Journal of the American Society for Information Science 51(12), 1090–1105.

Carroll, S.R., Herczog, E., Hudson, M., Russell, K., & Stall, S. (2021). Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR principles for Indigenous data futures. Scientific Data 8(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-021-00892-0

Darshini, P. (2001). Women and patrilineal inheritance during the Gupta Period. In Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. (Vol. 62, pp. 7–77). Indian History Congress.

Deodhar, L. (2010). Concept of the right of Stridhana in the Smirtis. Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute 70, 349–357.

Doyle, P. (2005). Replication and corpus linguistics: lexical networks in texts. http:/www. corpus. bham. ac. uk/PCLC/COL-ING_2005_paper. Pdf

Farghal, M., & Obiedat, H. (1995). Collocations: A neglected variable in EFL. Review of Applied Linguistics 33(4), 315. https://doi.org/10.1515/iral.1995.33.4.315

Firth, J.R. (1957). Modes of meaning. Papers in Linguistics 1934–51, 190–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2007.00164.x

Halliday, M.A. (1966). Some notes on ‘deep’ grammar. Journal of Linguistics 2(1), 57–67. https://www.doi.org/10.1017/S0022226700001328

Herat, M. (2022). Nothing short of devastation: Disabled writers’ responses to the COVID-19 lockdown during the first year of the pandemic. Medical Research Archives 10(6). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v10i6.2797

Jenset, G.B., & McGillivray, B. (2017). Quantitative Historical Linguistics: A Corpus Framework (Vol. 26). Oxford University Press.

Jois, R. (2004). Legal and Constitutional History of India: Ancient, Judicial and Constitutional System. Universal Law Publishing.

Kalashnikova, O. (2023). Exploring the Fukushima Effect: A Corpus-Based Discourse Analysis of the Algorithmic Public Sphere in Post-3/11 Japan (Doctoral dissertation, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU)).

Kehoe, A., & Gee, M. (2011). Social tagging: A new perspective on textual ‘aboutness’. Studies in Variation, Contacts and Change in English 6(5). https://varieng.helsinki.fi/series/volumes/06/kehoe_gee/

Kirschenbaum, M.G. (2016). What is digital humanities and what’s it doing in English departments? In Defining Digital Humanities. (pp. 211–220). Routledge.

Kiss, C. (2019). The Bhasmāṅkura in Śaiva texts. Tantric communities in context 83.

Lamoureux, C., & Camus, E. (2024). Moving Forward in Administrative History: Encoding the Département de La Seine and Paris Yearbooks (1883–1970). Journal of Open Humanities Data 10(1). https://doi.org/10.5334/johd.186

Lingat, R., & Derrett, J.D.M. (1973). The Classical Law of India (Vol. 2). [trans from the French with additions by J. Duncan M. Derrett]. University of California Press.

Louw, W.E. (1993). Irony in the text or insincerity in the writer? The diagnostic potential of semantic prosodies. In Text and Technology. (p. 157). John Benjamins.

Louw, W.E. (2000). Contextual Prosodic Theory: Bringing semantic prosodies to life. In C. Heffer and H. Sauntson (Eds). Words in Context: In Honour of John Sinclair. (pp. 48–94). ELR.

Martin, B.G., Norén, F.M., Mähler, R., Marklund, A., & Martin, O. (2024). The Curated UNESCO Courier 1.0: Annotated Corpora for Digital Research in the Global Humanities. Journal of Open Humanities Data 10. https://doi.org/10.5334/johd.181

McGillivray, B., Hengchen, S., Lähteenoja, V., Palma, M., & Vatri, A. (2019). A computational approach to lexical polysemy in Ancient Greek. Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 34(4), 893–907. https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqz036

McGillivray, B. (2020). Computational methods for semantic analysis of historical texts. In Routledge International Handbook of Research Methods in Digital Humanities. (pp. 261–274). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429777028

Nongbri, I.H. (2018). Women in Brahmanical Literature: Some aspects. XVI 1, 79–97.

Partington, A. (2004). Utterly content in each other’s company: Semantic prosody and semantic preference. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 9(1), 131–156. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.9.1.07par

Phillips, M. (1985). Aspects of Text Structure: An Investigation of the Lexical Organisation of Text. North Holland.

Schreibman, S. (2012). Digital Humanities: Centres and peripheries. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 46–58.

Simanowski, R. (2016). Digital Humanities and Digital Media: Conversations on Politics, Culture, Aesthetics and Literacy. Open Humanities Press. https://www.doi.org/10.26530/OAPEN_612791

Sinclair, J. (1966). Beginning the study of lexis. In C.E. Bazell, J.C. Catford, M.A.K. Halliday, & R.H. Robins (Eds). In Memory of J. R. Firth. (pp. 410–30). Longman.

Sinclair, J. (1999). A way with common words. In H. Hasselgard & S. Oksefjell (Eds). Out of Corpora: Studies in Honour of Stig Johansson. Rodopi B.V. Amsterdam.

Svensson, P. (2016). Humanities computing as digital humanities. In Defining Digital Humanities. (pp. 159–186). Routledge.

Stubbs, M. (2009). Memorial article: John Sinclair (1933–2007): The search for units of meaning: Sinclair on empirical semantics. Applied Linguistics 30(1), 115–137.

Thukar, A., & Thakur, A. (1930). Proof of possession under the Smritis. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 11(4), 301–335.

Tharakan, S.M., & Tharakan, M. (1975). Status of women in India: A historical perspective. Social Scientist, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.2307/3516124

Tomy, A.C. (2019). Property Rights of Women under Hindu Law: From Vedas to Hindu Succession (Amendment) Act 2005. Supremo Amicus 10, 24.

Wilkinson, M.D., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I.J., Appleton, G., Axton, M., Baak, A., ... & Mons, B. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data 3(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.18

Yajnavalkya, V.B., & Vidyarnava, R.B.S.C. (1918). Yajnavalkya Smriti: With the Commentary of Vijnanesvara Called the Mitaksara: and Notes from the Gloss of Balambhatta. AMS Press.

Yājñavalkya, V., & Chandra, S. (2010). Yajnavalkya Smriti: With the commentary of Vijnanesvara, called the Mitaksara and notes from the gloss of Balambhatta. http://www.archive.org/details/yajnavalkyasnnrit.

Yablo, S. (2014). Aboutness (Vol. 3). Princeton University Press.