8. Building a book history database:

A novice voice

Rebekah Ward

© 2024 Rebekah Ward, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0423.08

Abstract

This chapter recounts my lived experience as a novice Digital Humanist. It is deliberately anecdotal, rather than theoretical, in style and form. The chapter tells the story of how I commenced a doctorate in the field of book history, then, with minimal technical training, came to build a large relational database that both enabled and complemented my written dissertation as well as providing value for future users.

My research is centred on Angus & Robertson, the largest 20th-century Australian bookseller and publishing house. I was particularly interested in Angus & Robertson’s use of book reviews as a promotional tool. The company archive contains millions of miscellaneous documents and, even when limited to certain subsets, there were thousands of undigitised pages to interrogate.

In response to that scale, I turned to the Digital Humanities, using the Heurist platform to design a bespoke database schema then populate the requisite fields with metadata from the physical documents, and subsequently enriching the records with secondary research. The resultant Angus & Robertson Book Reviews Database, which has been published online, remains a living database that at the time of writing contains 152,000 records, each with several fields, amounting to over a million data points.

In this chapter, I explain design decisions as well as obstacles that I encountered whilst building the database without prior technical skills. I also share how the database has allowed me to tell previously untold stories about Angus & Robertson, book reviewing, and the 20th-century Australian print industry. The chapter concludes with a discussion of the ongoing potential of this specific database and how platforms like Heurist extend important opportunities to novice Digital Humanists.

Keywords

Database; Angus & Robertson; Heurist; Digital Humanities.

Prologue

I started my book-historical PhD at Western Sydney University (WSU) in 2020, intending to investigate the promotional strategies of Angus & Robertson, the largest 20th-century Australian publishing house.56 I was particularly interested in how the publishers were routinely distributing hundreds of copies of their books to the newspaper and periodical press (review copies) at home and abroad to solicit book reviews. This process was intended to saturate the market with information about the books while bypassing the need for paid advertising.

My research was based on the Angus & Robertson Archive, held by the State Library of New South Wales (SLNSW). That Archive, now containing over a million documents across hundreds of boxes, is one of the largest collections of publishing files in the world. According to its curators, it is “one of the most significant literary collections in Australia” (Edmonds & Peck, 2016), rendering it a cornucopia for scholars. However, the Angus & Robertson Archive also presents several obstacles to research. It is difficult to identify relevant materials because many records currently remain undigitised and the indexes are incomplete. When identification is possible, the scale of materials proves unwieldy. I limited my research to a discrete sub-series of reviewing records, but even that required me to sift through 134 undigitised scrapbooks containing tens of thousands of book reviews, as well as a set of complex business ledgers which tracked Angus & Robertson’s distribution of review copies.57

Despite that scale, I was reluctant to narrow the scope of my project (which was to include all genres of books published in 1895–1949) or only interrogate case studies at the risk of reaching unrepresentative conclusions. Book historian Simon Eliot speaks of the need:

[…] to see the forest, not a host of additional trees […] any number of individual studies would not be sufficient, because you could never be certain that you had assembled a reliable sample (2002, p. 284).

A similar argument is made by literary scholar Franco Moretti, who—with a debt to Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of the literary field (1996)—argues that literature cannot be:

… understood by stitching together separate bits of knowledge about individual cases, because it isn’t a sum of individual cases: it’s a collective system, that should be grasped as such (2005, p. 4).

To “see the forest” and grasp the “collective system”, while also finding a way to manage the sheer volume of records, I knew that I wanted to use Digital Humanities (DH) tools. This choice was partly inspired by exposure to innovative work being done by Western Sydney University’s Digital Humanities Research Group,58 and my prior use of quantitative methodologies as part of my Masters’ thesis (Ward, 2018). In particular, I saw the value in linking the two sub-series of archival materials that I was working with (the scrapbooks of reviews, and the distribution ledgers of review copies). These collections were clearly related but remained distinct from each other in the physical archive, with no way to easily move between them.

My intention to use DH tools was complicated by a significant obstacle: my relative lack of technical skills. This is not an uncommon experience for doctoral candidates commencing projects that involve the Digital Humanities. The current scholarly landscape demands that all researchers have at least some familiarity with DH, even if not defined as such, and also means that people from all disciplines find themselves conducting DH research. History is particularly impacted, with Adam Crymble (2021, p. 1) asserting “no discipline has invested more energy and thought into making its sources and evidence publicly available, or in engaging publics through digital mediums, or transforming their pedagogic practices with the help of technology”, albeit with some residual “divides between the traditional and digital scholar”. As a result, many people working in the DH—directly and indirectly—do not possess technical skills upon commencement of their project. Even the Department of Digital Humanities at King’s College (London) does not impose technical requirements upon students entering the PhD in Digital Humanities (established in 2005 as the first dedicated DH PhD), a program that explicitly aims to produce “digitally adept scholars”. Rather, students in that PhD come with varying levels of computing expertise and are free to conduct “research of any kind that involves critical work with digital tools and methods” (McCarty, 2012, pp. 36–37). Such shifts in the makeup of DH work have been enabled by the increasing availability of low-threshold digital tools as well as the rise of team projects that bring together discipline-specific researchers and computing experts. This, in turn, makes for richer scholarship and novel findings as more people can participate in the field.

Unfortunately, newcomers to DH often struggle to find ways to upskill, even when they are interested in doing so. There are still few dedicated opportunities for those who do not study computing to flexibly learn such skills, although there are increasing moves to incorporate digital skills into undergraduate programs, self-paced online learning options, and some dedicated, short-term DH certificates (see, for example, Spiro, 2012). In Technology and the Historian (2021), Adam Crymble describes the ‘Invisible College’ whereby researchers “pick up technological skills through informal channels […] developed to fill voids left within the traditional structures of universities, which were slow to adapt to the growing demand for new skills”. These informal channels, including social media, workshops and online discussion groups, rely on a self-learning model, often complicated by a lack of institutional funding and technical support.

In my case, I came to the PhD with few technological skills beyond familiarity with basic computing functions and more detailed experience with the Microsoft suite. I had no experience with programming, coding, digital textual analysis, GIS mapping or data mining. My undergraduate degree, also completed at Western Sydney University, had not included DH content or tools, nor had I completed any formal DH training as part of my Master of Research program. Even once enrolled in the PhD, there were few internal opportunities to rectify this gap. Western Sydney University does not run structured DH training for postgraduates outside of the coursework for the Master of Digital Humanities degree. The university does offer digital support for researchers via Intersect, including online training in programming (R and Python), surveys (Qualtrics and REDCap) and data analysis and visualisation (namely using Excel). I completed a few of these courses but found they were often geared to scientific disciplines and were mostly intended for intermediate users. Further, many of these workshops were based around skills training rather than broader methodological training which, as Mahony and Pierazzo (2012) reflect, is a more transient approach. I, therefore, struggled to see how I would be able to usefully adapt the skills presented in these workshops to my project. Other than trying to arrange and fund my involvement in external workshops, I had limited opportunities to learn advanced technical skills, particularly within the time and space afforded by a three-year full-time PhD in Australia. In the early stages of my doctorate, then, one of the overriding questions was how I could effectively and efficiently utilise DH tools in my project whilst also working towards a timely completion.

Project design

There were several possible solutions to this technological dilemma, each of which would determine the project direction. The solution that I chose to adopt was Heurist (HeuristNetwork.org), an open-source, not-for-profit data management application. While there are alternatives, most notably Omeka, Heurist was the most appropriate choice for my project for several reasons. The platform was designed specifically for Humanities researchers so it can handle long, plain-text fields and interlinked heterogenous data. The platform is also mutable and offers in-built searching, filtering, analysis and visualisation capacities. Furthermore—perhaps most significantly in my case—Heurist is low-threshold: the creation and maintenance of a database does not require any prior expertise in coding, nor does it take an onerous amount of time to produce. There was no charge for creating and hosting the database, the Heurist team is always responsive to requests for bug fixing, and the flexible budgeting structure meant that the costs for additional services (creating the associated website, including building new capacities specifically for my project) were viable within my limited candidature funds. Finally, the platform was already being used by other research teams at Western Sydney University, allowing me to draw on their expertise and experience with the platform.

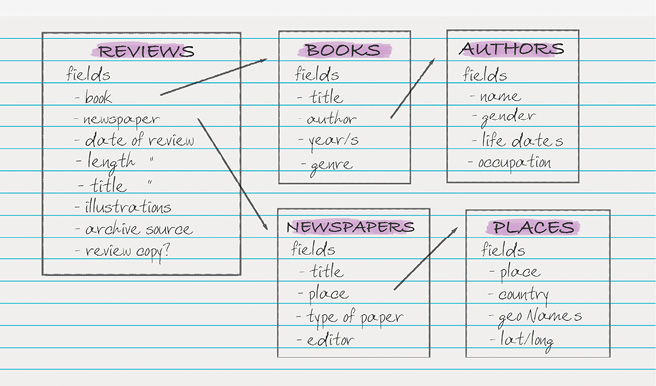

The suitability of Heurist to my work was soon evident. Within just a few hours I was able to create the core structure with some consultation from my doctoral supervisor, Professor Simon Burrows, whose own book history database is now hosted by the same platform.59 Heurist offers a range of templates so it is possible to use preconfigured record types, vocabularies and fields (then tailor them as necessary) but it is equally possible to create entirely new versions for specific projects. The original sketch of a schema—drawn up in March 2020—is illustrated in Figure 8.1. At that time, I envisaged the database would contain five record types (highlighted in purple), each containing multiple fields, with relatively straightforward connections between them as indicated by the directional arrows. Many fields were plain text (such as author occupation, editor name and book title), but some were temporal (such as the date of review and book publication) or geospatial (latitude/longitude). Others called on standardised Heurist vocabularies (such as yes/no for the presence of illustrations, and male/female/other for gender) or bespoke terms lists created for this project (such as types of newspapers and length of reviews).

Fig. 8.1 Initial database schema (as of March 2020).

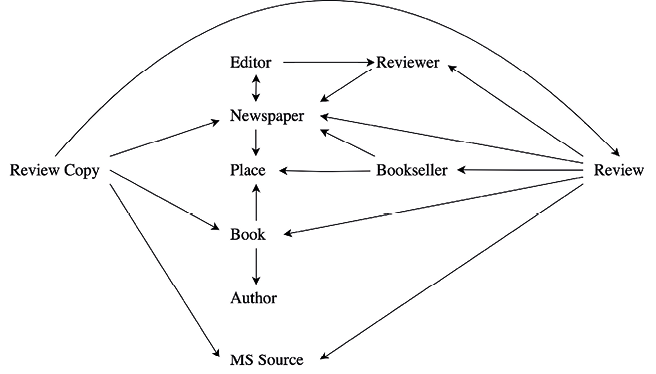

This schema has, unsurprisingly, undergone several changes since March 2020. Such changes are inevitable over the lifecycle of a DH project, since it is impossible to know at the outset precisely where a project will end up. This is especially true when dealing with primary sources, where greater engagement with the materials continually alters research plans, even more so when the associated database is being designed by a novice. Rather than having to wait until the end of data collection to start the construction of the database, though, Heurist allows for incremental creation. In my case, the database structure expanded significantly over time and now contains ten record types with more connections between the various nodes. The current version of the database schema is illustrated in Figure 8.2. I was also able to change the fields contained within record types, edit terms lists and create new relationships between records, all without coding changes or impacting existing data.

Fig. 8.2 Revised database schema (as of April 2023).

All changes to the database structure were designed in response to the complexity of the physical records. For example, as I processed more reviews it became apparent that Angus & Robertson were frequently sending review copies to the press via booksellers. Many reviews named specific local retailers as the source of their copy or encouraged people to buy the book from a designated local store. I first added a plain text field for booksellers within the review record type. However, it soon became apparent that booksellers were not minor characters in this story: they were significant agents in Angus & Robertson’s promotional strategy. Consequently, I created a separate bookseller record type and then linked those records to the reviews as needed.

Having created the requisite structures, I started to manually populate the database using information drawn from the Angus & Robertson Archive. Some data were directly added via the Heurist interface. Other cleaned, delimited data were uploaded as CSV files. This process required high-level decision-making at every stage. Names, dates, newspaper mastheads and book titles had to be carefully standardised across the database to avoid misattribution or distortion. This was not just a case of accurately typing the information that appeared on the physical documents, though it was also vital to minimise this type of human error. In most cases, dates and mastheads had been handwritten onto the clippings by staff at Angus & Robertson or the various newspaper offices, resulting in significant inconsistencies and some errors over time. To take a straightforward example, in regional New South Wales, competing Bathurst newspapers were recorded in archival materials as the Bathurst National Advocate and Western Times and, elsewhere, as the Advocate and Bathurst Times. Sometimes, such differences reflected actual name changes in the mastheads but often it was just a case of varying usage. Ensuring that such duplicate records were merged in the database was important to avoid skewed statistics. Yet, this proved difficult to achieve completely when dealing with more than 58,000 reviews of 1,950 books in 2,660 unique newspapers or periodicals, so it became an ongoing process in my project.

Another issue that I faced during the input stage was related to the temporal data. Some reviews had incomplete or illegible dates, or no dates at all. Approximate dates could be assigned based on known information, including by examining the dates of reviews located on the same page of the physical archive, as the scrapbooks had been prepared in rough chronological order. To acknowledge this in the database, I created separate fields for confirmed and fuzzy dates within the reviews record type, as well as an overarching decades field. At this stage, though, my novice status interrupted the development of the project. I failed to correctly standardise the format of the dates as YYYY-MM-DD before uploading the data, instead using DD-MM-YYYY. This resulted in significant errors. Thankfully, the aforementioned mutability allowed by Heurist meant I could redo this stage relatively quickly without impacting other data. Working through this case did serve to remind me that, wherever possible, it is best to troubleshoot such issues before uploading the data.

Once the initial input stage was complete, I was able to enrich the database records in a variety of ways. Firstly, inferences were drawn from the physical records. For example, I added a field for the length of the review. Given time constraints, it was not possible to precisely count the words or even lines for the 58,000 reviews in the database. In lieu of that fine-grained data, I classified all reviews into one of five length categories (capsule, short, medium, long, feature). Clear boundaries for each category were established at the outset of the project, ensuring the labels could be applied consistently.

Secondly, the two sets of records (distribution ledgers about review copies, and scrapbooks of reviews) were linked. It was clear from the correspondence and other business files that Angus & Robertson used these two collections alongside each other to shape and refine their promotional strategy. The publishers spoke of having to “hunt up” newspaper editors who had received a review copy but failed to return a review.60 The publishers were also prepared to strike papers from their distribution ledgers if this inattention continued over time, explaining to one editor, “we did not receive any copy of the papers containing these reviews, and therefore did not send any further books”.61 Despite this interrelationship between the ledgers and scrapbooks, it is difficult to see or analyse correlations between the collections when just using the paper-based archive. The collections could, however, be directly linked in the Angus & Robertson Book Reviews Database via Heurist’s record pointer function. This was a complex and time-consuming process, involving hours of manual labour, mostly relying on various search filters, but the outcome is one of the most valuable parts of the project. It makes it possible to see if an individual review copy of a specific book sent to a specific newspaper led to a review and, if it did, to immediately navigate to that review. Linking the two collections in this way also allows for quantitative analysis of return rates. That is, how many copies Angus & Robertson distributed to the press compared to how many reviews they received back. I found the publishers had an overall return rate of 24% (indicating the effectiveness of their mass-review strategy), though this was highly variable based on book genre, author reputation and newspaper/periodical.62

Thirdly, I added information from other archival sources to enrich the individual stories. In a letter to Angus & Robertson, author Katharine Susannah Prichard asked, about her novel, The Wild Oats of Han (1928), why “booksellers in Perth do not seem to know Han”.63 Publisher George Robertson responded they had distributed 145 review copies, “liberally notified” the Trade, and collected 150 reviews.64 Similarly, the publishers were able to inform author Doreen Puckridge that they had distributed 124 copies of her children’s book, King’s Castle (1931), to the press, accounting for 10% of the total print run.65 This book does not appear in the surviving distribution ledgers, so this letter is an important referent. Many letters in the Archive help explain the cessation of review copies to specific places, the types of support that Angus & Robertson received from booksellers and the press, and the publishers’ rationale for various business decisions. For example, one page of the scrapbooks carries a quick handwritten annotation that Angus & Robertson were no longer distributing review copies to the Murray Pioneer, a weekly newspaper based in Renmark in South Australia, due to “some unpleasantness” between Robertson and the paper’s editor, Henry Samuel Taylor.66

Finally, supplementary information was sourced from online catalogues and bibliographic databases such as AustLit, the Australian Dictionary of Biography, Trove, GeoNames, Papers Past and World Cat, as well as from various secondary sources.67 Long-form, discursive details were recorded, while other information was categorised or standardised across the database. Types of information recorded at this stage included biographic details for authors and reviewers (gender, life dates, occupations and, where known, identities of pseudonymous reviewers), bibliographic information about books (namely genre, edition printing date/s and place of publication), and latitude/longitude of geographic locations. Details about newspapers and periodicals (such as run dates, periodicity, affiliations, circulation figures, place of publication, known editors and proprietors, title changes and amalgamations) and descriptions of bookstores were also recorded. Heurist’s capacity for incremental structure creation and simple procedures for inputting data means additional information can continue to be added in the future.

Outputs

The Heurist team—namely designer Dr Ian Johnson and the Community Technical Advisors, Dr Michael Falk and Dr Maël Le Noc—aided in the construction of a public interface for the Angus & Robertson Book Reviews Database, with embedded explore, rank, search and mapping capabilities to improve functionality for current and future users. In the spirit of open DH, that interface has been published under a Creative Commons Attribution International 4.0 license, which enables the use, redistribution and expansion of materials as long as the original source is appropriately credited, and all changes are acknowledged.

In the future, the functionality and usefulness of the database could further be enhanced by adding digitised copies of the reviews and subsequent application of Optical Character Recognition (OCR). This would allow researchers to study the corpus more closely, including for evidence of repetition between the reviews. The data might also be combined with or connected to existing projects to meet principles of findability, accessibility and interoperability (Hagstrom, 2014). Potential partners include ‘Linked Archives’, which seeks to bring together related but disparate collections including the Angus & Robertson Archive (see Bones, 2019), and AustLit, a digital database that aims to be “the definitive information resource and research environment for [national] literary, print, and narrative cultures” but does not yet contain much information about reviewing. Even without such additions, though, the Angus & Robertson Book Reviews Database is already an original, useful DH output in its own right.

Publishing the digital outputs of research in this way is an important aspect of the digital revolution and is an ethical imperative for publicly funded projects (Bode, 2019). It also ensures transparency, allows others to check, corroborate or challenge conclusions presented in written outputs, and enables future researchers to ask and answer innumerable questions related to their own work. Publishing digital projects, especially with a Digital Object Identifier, enables them to be (potentially) counted towards an individual’s research output. As Kerry Kilner noted in her discussion of AustLit in 2009:

Are we nearing a time when a research outcome comprised of a web-based artefact which takes a highly detailed but visual approach to the analysis of an author’s oeuvre might be formally recognised as a top-level publication? Could a piece of scholarship comprising an exegesis with an interoperable dataset be understood as of high a value as a 5000-word essay… or even a single-authored monograph? It is very likely that these types of scholarship already being developed across many humanities disciplines will begin to be regarded as at least as valuable as traditional forms (2009, pp. 300–301).

In the 15 years since Kilner posed such questions, there have been some shifts towards such recognition, though there is still a long way to go in this area.

One important issue when considering the long-term value of such outputs is the risk of impermanence. Claire Brennan (2018, p. 5) points out that digital objects are “inherently less stable than the physical objects they at times completely replace” as technology is always superseded, leaving objects unreadable and hardware unusable. Unlike many other database applications, Heurist has been conceived for the sustainability of the data. Firstly, it is built on MySQL (the most widely used open-source server DBMS) and, secondly, there is internal documentation of structures. Thirdly, the associated website is integrated as data within the database itself and, lastly, there is the option to download a self-documenting archive. That archive contains an SQL dump of the entire database, a comprehensive XML rendering of the database content, file structures containing uploaded files, icons and custom formats, and documentation of the structure of these resources to allow them to be interpreted into the future. These archive files can also be automatically uploaded to a memory institution repository, depending on configuration.

A more immediate contribution to database sustainability is the ongoing software development and centralised maintenance of the platform by the Heurist project team. The team, led by Heurist creator Ian Johnson, monitors and updates public servers supporting hundreds of projects, independent of individual project funding. Legacy projects beyond their funding life are thus supported by contributions from projects with current funding, applying a “Robin Hood” strategy (Ian Johnson, personal communication).

It is also important to acknowledge other limitations of DH projects. Digital outputs are often seen as more objective than physical equivalents and are idealised as more democratic. Katherine Bode (2008) describes how DH can help “denaturalise” the canon and avoid “hierarchical, qualitative judgements and selections,” while David Berry (2011, p. 8) writes about the possibility of DH projects bypassing “traditional gatekeepers of knowledge”. Paul Fyfe (2016, p. 548) notes such sources “seem to erase any intermediary state between source object and digital surrogate in the cloud”. Helen Bones (2019) suggests “the incomplete nature of the material being searched is less obvious in digital form”.

Yet, just like physical archives, digital projects involve acts of human mediation and often reinforce, rather than challenge, canonicity and so continue to exclude alternate voices (Earhart, 2012; Wilkens, 2012). Scholars should therefore communicate, and actively reflect on, the human decisions involved in the construction processes. Jason Ensor (2009b, p. 244) talks about offering the “necessary apologetics and methodological uncertainties that contextualise analytical labour” while Paul Fyfe (2016, p. 550) endorses releasing “para data” including “procedural contexts, workflows, and intellectual capital generated by groups through a project’s life cycle”. In surveying global digitised newspaper collections, Tessa Hauswedell et al., (2020, p. 142) recommend the creation of explanatory texts to accompany digital archives. More broadly, a Checklist for Digital Outputs Assessment (2021), produced by Arianna Ciula for King’s College, describes the need to provide “a description and essential information on the digital output’s scope, limitations, date of public release and intended audiences” as well as “the content of the output and the decisions made in all key steps of its curation”.

In response to such suggestions, each tool offered within the interface of the Angus & Robertson Book Reviews Database (such as the map, rank and search functions) is accompanied by clear instructions for use. This is particularly important given the ‘novice DH-er’ theme of my project. Furthermore, the interface includes an “Overview” and detailed “User Guide” to outline record types, define key terms and describe curation processes including decisions around inclusion, exclusion, and data cleaning. For example, the User Guide explains that the term “printing date/s” is used throughout the project because the Angus & Robertson reviewing records typically cite the date of distribution instead of the date of publication and do not differentiate clearly between impressions and editions. The database is also impacted by mediation processes previously imposed on the physical archive. From the 1890s onwards, Angus & Robertson staff removed “worthless and uninteresting letters” from their correspondence files (Tucker & Anemaat, 1990, p. 12). Other documents have been lost to time. Further alterations to the collection were made by State Library of NSW curators who made decisions about the arrangement of materials and discarded items such as “recent invoice books and computer printouts of stock holdings” because “the information contained therein was trivial or because it was recorded in some other part of the archives” (Brunton, 1980). Critically reflecting on the patchy, mediated nature of the physical collection and database alike contextualises conclusions arising from subsequent research. Communicating that information to other users of the digital outputs ensures that future research based on the database can similarly acknowledge how mediation processes have impacted findings.

Outcomes

When first designing the Angus & Robertson Book Reviews Database, I envisaged a fairly simple digital index of the relevant reviewing records. I was primarily focused on retrievability: creating a DH tool that would help when writing up my thesis by allowing me to find records more quickly. If I wanted to write about reviewing practices in Ballarat, for example, I could quickly produce a list of review copies, reviews, newspapers and reviewers associated with that location (there are 1,324 records about Ballarat). Alternatively, if I was interested in a specific book—say May Gibbs’ Wattle Babies (1918) or P. S. Cleary’s The One Big Union (1919)—I could retrieve all review copies and reviews in a single search (a total of 762 records for Wattle Babies and 683 for Cleary’s book). In these cases, the records are spread across multiple volumes in the physical archive, with no clear way of identifying them all without spending hours leafing through every page and, even then, no simple technique for linking them together in a meaningful way. The database resolves that issue.

Another form of retrievability was identifying statistically significant or otherwise interesting case studies worthy of closer, more qualitative research. Using the database in this way made it possible to look beyond canonical texts and contextualise all cases within broader histories to understand their relative exceptionality or conventionality. As Jason Ensor (2009, p. 200) notes in his study of Angus & Robertson, data thus acts as “starting points for greater discussion, not end points”. For example, the Angus & Robertson Book Reviews Database made it possible to determine that the most-promoted titles in the collection were C. J. Dennis’ Doreen (1,079 copies across multiple editions) and the Common-Sense Hints on Plain Cookery (919 copies). The most reviewed titles were My Life and Work by Henry Ford (359 reviews) and, in literature, The Songs of a Sentimental Bloke by Dennis (331 reviews). Banjo Paterson’s debut novel, An Outback Marriage, fell into third position in both lists (849 copies and 294 reviews).

I could also determine that the Sydney Morning Herald, Brisbane Telegraph, Hobart Mercury and Adelaide Advertiser—all large dailies in Australian capital cities—were returning the most reviews to Angus & Robertson (with an average of 830 reviews per paper). Outside of the capital cities, regional dailies like the Newcastle Sun and Bendigo Advertiser were also returning significant numbers of reviews, and even some small country papers had impressive coverage. Having identified these cases, I could then quickly navigate to the relevant reviews to undertake more discursive analysis. In doing so, the iconic Sydney Bulletin emerged as an interesting case study. It became clear that the number of review copies flowing to that periodical was directly correlated to the tenures of its various editors. Angus & Robertson sent relatively few review copies to the Bulletin when the position of literary editor was filled by A. G. Stephens between 1896–1906, and, later, David McKee Wright from 1916–1926, as they disagreed with some opinions of those critics.68 The publishers sent significantly more copies to the Bulletin when Douglas Stewart, with whom they had a more positive relationship, took up the position of editor in the 1940s.69

While retrievability remains an important function of the Angus & Robertson Book Reviews Database, other uses soon became apparent. In particular, the database makes it possible to resolve gaps in the physical records. Three illustrative cases are discussed here.

Case 1

The Aussie was a Sydney-based journal that, from 1923, had a New Zealand supplement. Some clippings in the Angus & Robertson Archive do not specify which version of the paper they had appeared in. Using the database to identify all Aussie reviews across various scrapbooks in the physical archive revealed distinct tendencies in each version. The Sydney paper ended reviews with bibliographical details (title and author imprint, followed by an endash, then the price) while the reviews in the New Zealand supplement usually ended with the price or a statement that the book under review could be purchased from local retailers. Observing this trend meant it was possible to ascertain the likely place of publication for the unattributed Aussie reviews and add that information to the database.

Case 2

In the 1920s, Angus & Robertson launched their Platypus series (mostly consisting of reprints). The Platypus books were assigned a series number upon publication. Often, Angus & Robertson would only record the number in their reviewing records rather than the title or author. This meant the distribution records were not clearly associated with a specific title, making it difficult to draw any conclusions about the books or link pairs of reviews and review copies together. The Angus & Robertson catalogues that do survive reveal that numbers were assigned by genre rather than chronologically, with numbers 1–5 reserved for children’s literature and the 30s relating to novels, while books numbered from 80 onwards were general non-fiction. I knew from the distribution ledgers that review copies of multiple Platypus books tended to be distributed at one time, so it seemed likely the same books would also be reviewed together. However, the reviews had been split into “paras” for each book and filed across several scrapbooks, so it was necessary to first conduct structured searches in the database. To take just one instance, Platypus books #83 and #84 were sent to the press in June 1924 alongside #34. A preserved catalogue identified #83 and #84 as the twin volumes of Studies of Australian Crime by John Fitzgerald. I then searched the database for reviews of novels that had been published on the same day and in the same papers as the reviews of Fitzgerald’s books. Through this process, it was possible to conclude, with a reasonable degree of certainty, that Piebald, King of Bronchos (a novel by Clarence Hawkes) was the elusive #34. I was then able to update the database accordingly, with due acknowledgement of the residual uncertainties, and, importantly, link the review copies of #34 to the reviews of Piebald.

Case 3

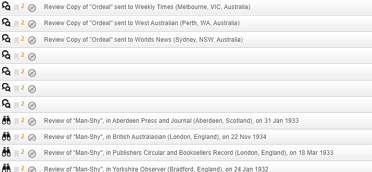

Multiple reviews in the Angus & Robertson Archive were signed “CL” (see Figure 8.3). These reviews appeared in nine different papers across four Australian states from 1934–1948 so were likely from more than one reviewer, but the physical records do not offer any explanation of the identity of the reviewer/s. By comparing these reviews with attributed reviews in the database, particularly looking for correlations in dates and locations, it is possible to resolve some of these cases. The Perth ‘CL’ was probably by C. Lemon, who was actively writing book reviews under his full name for the Western Australian press in the 1930s. Meanwhile, other ‘CL’ reviews were presumably written by Clem Lack, a journalist and historian who produced various types of content, including book reviews, for the Brisbane Telegraph in the early 1940s and then for the Melbourne Age in 1945–1947. It is possible that Lack also wrote some of the other ‘CL’ reviews through his continued connections with various Australian newspapers. Having made these identifications, it was possible link the requisite records in the database.

Through the same process, it can be assumed ‘JKE’ was John Ewers, an author and journalist who also wrote under the pen name ‘Yorick’, and that ‘ARC’ was critic A. R. Chisholm. Dozens of other cases can also be posited with varying degrees of certainty. Melbourne reviewer ‘CT’ might be journalist Clive Turnbull, ‘HRR’ could be Auckland Professor of Economics Harold Rione Rodwell and ‘GM’ might have been George Mackaness, an educationist and Angus & Robertson author in his own right. Such findings would not have been possible using the physical archival records in isolation.

|

Book Title |

Newspaper |

Year |

Identity of Reviewer |

|

Marsden and the Missions |

Daily News (Perth) |

1936 |

C Lemon |

|

Papuan Wonderland |

Daily News (Perth) |

1936 |

C Lemon |

|

Only the Stars are Neutral |

Unlisted |

ca.1942 |

Unconfirmed |

|

The Keys of the Kingdom |

Telegraph (Brisbane) |

1942 |

Clem Lack |

|

The Drums of Morning |

Unlisted |

ca.1943 |

Unconfirmed |

|

Dress Rehearsal |

Telegraph (Brisbane) |

1943 |

Clem Lack |

|

Guadalcanal Diary |

Telegraph (Brisbane) |

1943 |

Clem Lack |

|

I Escaped from Hong Kong |

Telegraph (Brisbane) |

1943 |

Clem Lack |

|

Telegraph (Brisbane) |

1943 |

Clem Lack |

|

|

Such is Life |

Telegraph (Brisbane) |

1944 |

Clem Lack |

|

The Incredible Year |

Telegraph (Brisbane) |

1944 |

Clem Lack |

|

Isles of Despair |

Age (Melbourne) |

1947 |

Clem Lack |

|

Henry Lawson |

Age (Melbourne) |

1947 |

Clem Lack |

|

Flying Doctor Calling |

Age (Melbourne) |

1947 |

Clem Lack |

|

Practical Homes |

Country Life (Sydney) |

1947 |

Unconfirmed |

|

Shannon’s Way |

Advocate (Melbourne) |

1948 |

Unconfirmed, possibly Lack |

|

Gone Tomorrow |

ABC Weekly (Sydney) |

1948 |

Unconfirmed |

|

Bradman |

Advocate (Melbourne) |

ca.1948 |

Unconfirmed, possibly Lack |

|

Stone of Destiny |

Advocate (Melbourne) |

1949 |

Unconfirmed, possibly Lack |

Fig. 8.3 All reviews signed ‘CL’ in the Angus & Robertson Archive (by date).

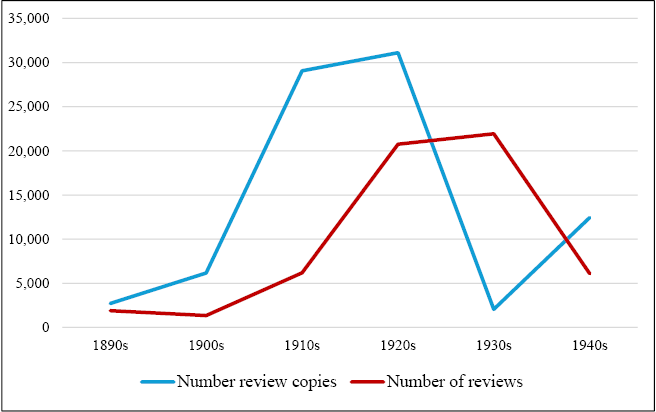

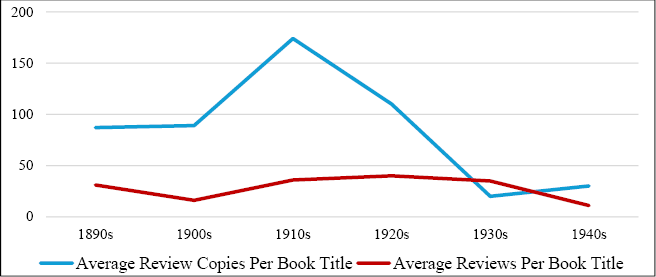

Beyond these functions of retrievability and filling in gaps in the physical materials, the database offers additional uses that are not evident within the physical Angus & Robertson Archive. For example, the addition of a higher-level decade field simplified the process of conducting chronological searches and analyses. This enabled discussion about changes in Angus & Robertson’s publishing output and review strategy over time. I was able to graph the number of review copies and reviews per decade, finding a significant increase from the 1910s and, particularly, during the 1920s (see Figure 8.4). It was also possible to translate these figures to average copies/reviews per book title to take into consideration the growth in the firm’s publishing schedule, finding that the peak of Angus & Robertson’s distribution strategy occurred in the 1910s despite the constraints of the First World War (Figure 8.5).

Fig. 8.4 Number of review copies and reviews in Angus & Robertson Archive (over time).

Fig. 8.5 Average number of review copies and reviews per book title (over time).

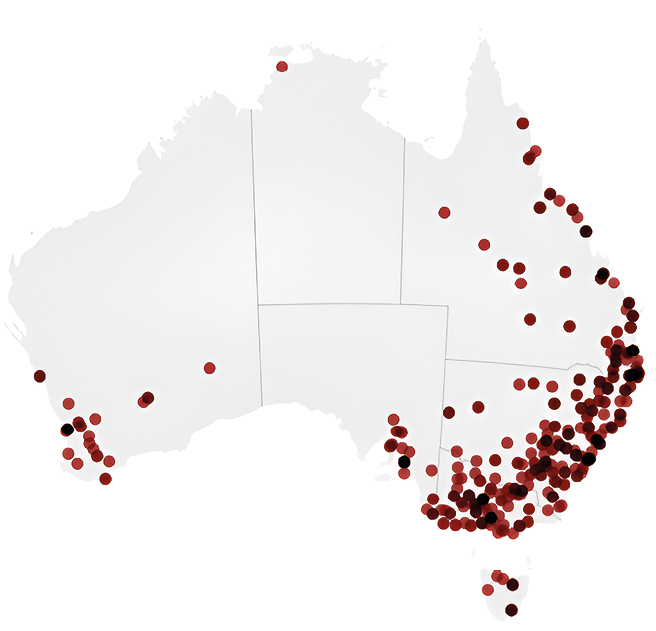

Another example of new information made visible by the database is the extent of Angus & Robertson’s engagement with the booksellers. By creating a record type for the booksellers, I was able to identify 732 retailers involved in Angus & Robertson’s promotional strategy across 1895–1949, including 556 in Australia (see Figure 8.6). I have also been able to enrich some of those records via secondary research, particularly using The Early Australian Booksellers (1980) and The Golden Age of Booksellers (1981). Within my doctorate, this inclusion of booksellers has shaped discussions of the highly networked nature of Angus & Robertson’s promotional strategy. The publishers deliberately involved other bookish actors in their processes, seeking to create a collegial trade and strengthen their own relationships with local retailers around the country. More broadly, in place of any surviving or complete list of domestic booksellers, this aspect of the database reveals the breadth of the Australian book trade in the 20th century.

Fig. 8.6 Map of Australian retailers involved in Angus & Robertson’s promotional strategy.

Beyond the specific case of Angus & Robertson, my database contributes to understanding of the nature and characteristics of reviewing. Tracking bylines revealed that 93.6% of reviews stored in the Angus & Robertson Archive were anonymous, and that even many of the attributed reviews masked reviewer identity with pseudonyms or initialisms (a further 4.3%). Categorising the length of reviews revealed the majority were brief, usually a single paragraph (38.8%) or less than a column in a standard broadsheet (42.1%). These findings—alongside general observations that most reviews tended to be enthusiastic and descriptive—led to the conclusion that the majority of the Angus & Robertson reviews were general notices rather than literary criticism. Multiple types of book reviewing were therefore occurring in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, even though most scholarship focuses to an exclusionary extent on long-form evaluative reviews. The database therefore makes it possible to tell new stories about Angus & Robertson and their reviewing strategies, as well as about book reviewing and the 20th-century print industry.

Coda

Even as a self-proclaimed novice DH-er, I was able to conduct most of this work independently. Any coding bugs that did emerge were resolved via consultation with the Heurist team. For example, at one stage several title masks disappeared from my database for no apparent reason (see Figure 8.7), but Johnson and Le Noc were able to rapidly resolve this in the backend. This points to the advantage of a centrally managed platform with technical staff on call to assist with various projects, rather than a locally installed application where fixes are dependent on the vagaries of technical staff availability and knowledge.

Fig. 8.7 Sample of database entries, showing the disappearance of constructed titles for some records.

My project barely scratches the surface of what is possible using the Angus & Robertson Book Reviews Database. Countless other aspects could be taken up by others in future research projects in small or significant ways, including to address questions that have not been conceived of yet. In this way, the database—like all DH projects—is not just a tool that helped with my own thesis, it is an original and significant research output in its own right: one that even novice users can create and use effectively.

Looking outwards, this discursive account of my own lived experiences in DH demonstrates the transformative potential of low-threshold, user-friendly, readily available digital platforms like Heurist and others. By dismantling technical barriers that may otherwise hinder entry to the field, these platforms allow researchers with diverse disciplinary backgrounds to become novice, then expert, DH-ers. This influx of voices, perspectives and approaches fosters a more inclusive and innovative research environment. Established DH tools therefore afford new opportunities to people without programming backgrounds, and in turn, those people beneficially expand the field of DH.

Works Cited

Angus & Robertson Book Reviews in Bound Volumes. (1894–1970). Collection 3, Series 4, Sub-Series 1. ML MSS 3269 Boxes 478–531. https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/1bGdoprY

Angus & Robertson Ltd Business Records. (1885–1973). Collection 3, Series 1, Sub-Series 1. ML MSS 3269 Boxes 1–25. https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/n5lXBlg9

Angus & Robertson Publishing Files and Associated Papers. (1858–1933). Collection 1, Series 1. ML MSS 314 Volumes 1–90. https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/9gkdb8X9

AustLit: The Australian Literature Resource. (2002). University of Queensland. www.austlit.edu.au

Australian Booksellers Association. (1980). The Early Australian Booksellers. Australian Booksellers Association.

Australian Dictionary Biography (n.d.). Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. https://adb.anu.edu.au/

Barker, A.W. (1982). Dear Robertson: Letters to an Australian Publisher. Angus & Robertson.

Berry, D. (2011). The Computational Turn: Thinking About the Digital Humanities. Culture Machine 12. http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/49813/

Bode, K. (2019). Large, vigorous, and thriving: Early Australian publishing and futures of publishing studies. In M. Weber & A. Mannion (Eds). Book Publishing in Australia: A Living Legacy. (pp. 1–28). Monash University Publishing.

Bode, K. (2008). Beyond the colonial present: Quantitative analysis, ‘resourceful reading’ and Australian Literary Studies. JASAL Special Issue, 184–197. https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/JASAL/article/view/10212

Bones, H. (2019). Linked digital archives and the historical publishing world: An Australian perspective. History Compass 17(3), https://www.doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12522

Bourdieu, P. (1996). The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. Stanford University Press.

Brennan, C. (2018). Digital Humanities, digital methods, digital history, and digital outputs: History writing and the digital revolution. History Compass 16(10). https://www.doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12492

Brunton, P. (1980). The Angus & Robertson Archives. Bibliographical Society of Australia and New Zealand Bulletin 4(3), 191–201. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/ielapa.801027903

Ciula, A. (2021). Checklist for Digital Outputs Assessment. King’s College London. https://zenodo.org/records/3361580

Crymble, A. (2021). Technology and the Historian: Transformations in the Digital Age. University of Illinois Press.

Earhart, A.E. (2012). Can information be unfettered? Race and the New Digital Humanities Canon. In M.K. Gold (Ed.). Debates in the Digital Humanities. (pp. 309–331). University of Minnesota Press.

Edmonds, E., & Peck, A. (2016, October). Literary giants: Revealing the Angus & Robertson Collection. Paper presented at the Australian Society of Archivists National Conference, Parramatta. https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/ literary_giants_-_revealing_the_angus_robertson_collection_presentation.pdf

Eliot, S. (2002). Very necessary but not quite sufficient: A personal view of quantitative analysis in book history. Book History 5, 283–293. https://www.doi.org/10.1353/bh.2002.0006

Ensor, J. (2009a). Still waters run deep: Empirical methods and the migration patterns of regional publishers: Authors and titles within Australian literature. Antipodes 23(2), 197–208. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41957815

Ensor, J. (2009b). Is a picture worth 10,175 Australian novels? In K. Bode & R. Dixon (Eds). Resourceful Reading: The New Empiricism, eResearch, and Australian Literary Culture. (pp. 240–273). Sydney University Press.

Fyfe, P. (2016). An archaeology of Victorian newspapers. Victorian Periodicals Review 49(4), 546–577.

GeoNames. (n.d.). https://www.geonames.org/

Hagstrom, S. (2014). The FAIR data principles. The Future of Research Communications and e-Scholarship. https://force11.org/info/the-fair-data-principles/

Hauswedell, T., Nyhan J., Beals, M.H., Terras, M., & Bell, E. (2020). Of global reach yet of situated contexts: An examination of the implicit and explicit selection criteria that shape digital archives of historical newspapers. Archival Science 20, 139–165. https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s10502-020-09332-1

Kilner, K. (2009). AustLit: Creating a collaborative research space for Australian literary studies. In K. Bode & R. Dixon (Eds). Resourceful Reading: The New Empiricism, eResearch, and Australian Literary Culture. (pp. 299–14). Sydney University Press.

Mahony, S., & Pierazzo, E. (2012). Teaching skills or teaching methodology? In B. Hirsch (Ed.). Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles and Politics. (pp. 215–25). Open Book Publishers. https://www.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0024

McCarty, W. (2012). The PhD in Digital Humanities. In B. Hirsch (Ed.). Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles and Politics. (pp. 33–46). Open Book Publishers. https://www.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0024

Moretti, F. (2005). Graphs, Maps, Trees: Abstract Models for a Literary History. Verso.

Papers Past. (n.d.). Auckland: National Library of New Zealand. https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/

Riddell, E. (Ed.). (1981). The Golden Age of Booksellers: Fifty Years in the Trade. Abbey Press.

Spiro, L. (2012). Opening up digital humanities education. In B. Hirsch (Ed.). Digital Humanities Pedagogy: Practices, Principles and Politics. (pp. 331–363). Open Book Publishers. https://www.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0024

Times Literary Supplement. (n.d.). Historical Archive, 1902–2019. Gale Primary Sources. https://www.gale.com/intl/c/the-times-digital-archive

Trove. (n.d.). National Library of Australia. https://trove.nla.gov.au/

Tucker, S., & Anemaat, L. (1990). Guide to the Angus & Robertson Archives in the Mitchell Library. Library Council of NSW.

Ward, R. (2018). Publishing for Children: Angus & Robertson and the Development of Australian Children’s Publishing, 1897–1933. Master’s thesis, Western Sydney University. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.7/uws:51862

Ward, R. (2023). Angus & Robertson Book Reviews Database. https://heuristref.net/Rebekah_ARBookReviews

Wilkens, M. (2012). Canons, close reading, and the evolution of method. In M.K. Gold (Ed.). Debates in the Digital Humanities (pp. 249–258). University of Minnesota Press.

WorldCat. (n.d.). www.worldcat.org/