7. Prototyping the Narrative Skeleton:

Story Structure, Types of Narration and Vestigial Elements in the Genesis of James Joyce’s ‘Ithaca’ Episode

©2024 Joris Žiliukas, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0426.07

Where is the ‘skeleton’ in ‘Ithaca’, the penultimate episode of Ulysses? The ‘Organ’, assigned to the episode in the Gilbert schema Joyce devised in 1921, promises structure and stability. This assurance is, however, undermined once the reader discovers a second, earlier schema, which instead designates the episode’s organ as ‘Juices’. In a 1920 letter to Carlo Linati, Joyce included this list of correspondences and describes it as a ‘sunto-chiave-scheletro-schema’ [‘summary-key-skeleton-scheme’] (SL, 270–71).1 Here the Italian word for ‘skeleton’ again seeks to provide stability, but whatever was ‘skeletal’ about the 1920 schema was apparently not stable enough to survive into 1921, and ‘Ithaca’ had its ‘Organ’ reassigned from ‘Juices’ to ‘Skeleton’.

All this to say that it is not always advisable to put blind faith in Joyce’s own explications. The tantalising concreteness of the schemata overshadows the fascinating implication that Joyce changed his mind as he worked. Michael Groden and A. Walton Litz have written about Joyce’s creative practices, both distinguishing between ‘Early’ and ‘Late’ stages of writing, with Groden proposing a third—‘Middle’—stage (Litz 1974; Groden 1977). Each stage is characterised by different approaches to writing, and the late stage overturned the entire novel, along with producing the final episodes. With the expensive purchase of Joyce’s manuscripts by the National Library of Ireland in 2002, a wealth of early drafts has become available, making possible a micro-scale investigation of the genesis of ‘Ithaca’ through manuscript evidence. The manuscript containing the draft of ‘Ithaca’, referred to as the ‘proto-text’ or as the ‘proto-draft’,2 is especially enlightening, as it was composed in the intervening months between the Linati and Gilbert schemata, promising to render visible the growth of the skeleton.

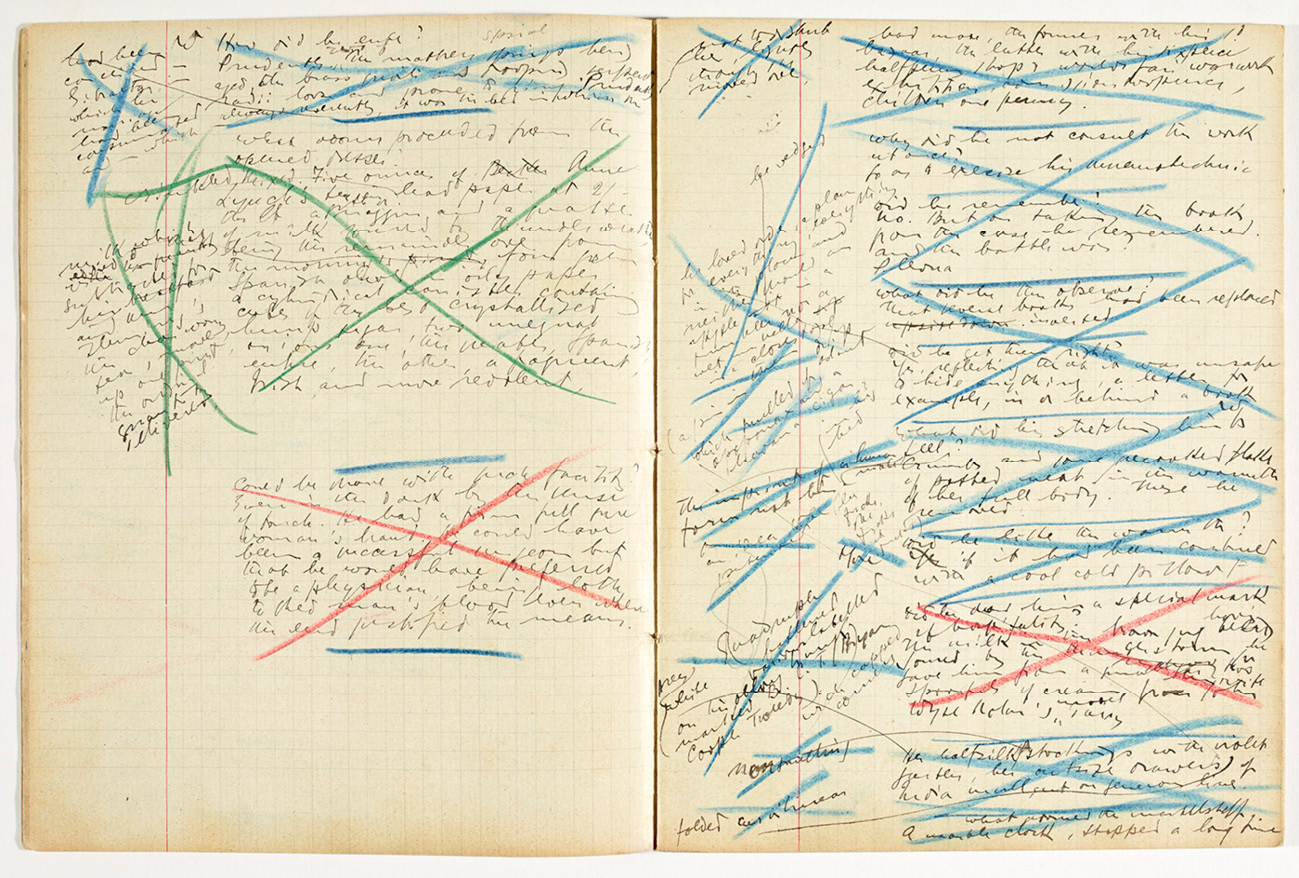

The proto-draft is written out in page-long stretches of questions and answers, the stylistic calling card of ‘Ithaca’, and contains various additions in the margins. The writing is so tight that Joyce used multi-coloured crayons to divide up and cross out separate sections as they were reused in the following drafts. The episode is often described as a ‘catechism’ for its question-and-answer routine, but, in this state, it is more akin to a colourful pile of LEGO bricks. These ‘bricks’ are not yet arranged, nor is the ‘building set’ complete. The draft stage that follows, the Rosenbach fair copy, is roughly twice as long with 66% more questions and answers, and the 1922 text is three times as long (Madtes 1983, 36).

The most salient structural feature Joyce worked out during the movement from the disjunct proto-draft to the tightly woven fair copy is the narrative. All three of its levels—narrative text, narration and story, to use Mieke Bal’s (2017) terminology—are subject to substantial reshaping. The story is brought into existence from nothing, and the time and place are made consistent and clear. This is done by rearranging the textual ‘blocks’, i.e. the question-and-answer pairs. Joyce arranges coherent sections into a plot, whereas disparate blocks congeal into new scenes. The ‘skeleton’—a chronotope, narrator, fabula, beginning and ending which support the text—comes into view.

On the other hand, Joyce also develops strategies which work to ‘undo’ whatever progress this narrative makes. Terence Killeen notes that, despite the narrative’s ‘impressive mastery of facts’, most of what is narrated ‘is oddly disappointing’ (2022, 278). What Killeen and others find disappointing is brought about by ‘disnarration’ and ‘the unnarrated’, that is, hypotheses, implausible tales and omissions (Prince 1988). These techniques counteract, remain silent on, and digress from the fabula, unmaking ‘Ithaca’ as it is being made. While traces of these are present in the proto-draft, their fleshed-out versions in the fair copy afford unique insight into how such strategies were utilised to ‘take apart’ the narrative skeleton.

Rather than a comparison of two drafts, like the confrontation of ‘Juices’ against ‘Skeleton’ as the organs of ‘Ithaca’, this essay aims to describe the creative process the comparison reveals, in the vein of genetic criticism. Dirk Van Hulle argues that this revelation emerges from ‘the tension between the concrete objects of manuscripts that have been left behind and the abstract retrospection to reverse-engineer the process that produced them’ (2022, 138). By reading the proto-draft and the fair copy as traces of the operations that produced the final version of ‘Ithaca’, it is possible to interrogate Joyce’s work in a way which dissolves (or at least remedies) the ambiguities created by ‘skeletal’ interpretations of the novel, such as the schemata provide. Instead of accepting ‘Skeleton’ as the ‘Organ’ that ‘Ithaca’ represents, we can ask how it got there, and how (and when) it is meaningful for reading the episode.

Genetic criticism allows for more than simply re-tracing what is found in the published text—it also casts light on the significance of what is left behind. As a writer, Joyce tended to add disproportionately more than he would take away (Madtes 1983, 35), and therefore textual units that remain confined to the proto-draft appear especially significant. Some paragraphs are recycled in such a way as to become almost unrecognisable or are left behind only to be re-added at a later stage. Here I lean heavily on what Van Hulle calls ‘vestigial’ writings. A writer’s unused notes, while ‘purposeless from a teleological point of view’, are still ‘crucial […] in the study of creative writing processes’ (2022, 170). These elements do not appear in the final version, and thus have no ‘end’ (teleological) goal, but they still contribute to the final ‘shape’ of ‘Ithaca’. Returning to the skeleton metaphor, these vestigial ‘bones’ highlight how the episode’s structure works precisely by virtue of not fitting the final design.

Though this essay mainly focuses on the proto-draft and the fair copy, it occasionally references later drafting stages, particularly the first typescript and its extracts. With reference to narratology and looking through a genetic lens, it is shown how the development of narrative contributes to the effect, that is, the poetics, of the episode, and how, in its yet-undeveloped form, the proto-draft was used to work out important aspects of narrative for the final version.

The Structure of the Story: Assembling the

Narrative Skeleton

Studying the composition of ‘Ithaca’ means studying the composition of Ulysses as a whole. It was the last episode to be written but appears as the second-to-last in the novel. In several letters dating to the end of 1920 and the beginning of 1921, Joyce mentions the final part of Ulysses as being ‘sketched’ (LIII, 31) or ‘in part written’ (LII, 459). None of these sketches are known to be extant, but the letters testify that Joyce’s conception of the final episodes changed drastically during the process of writing. ‘Ithaca’, one of the episodes he refers to as ‘very short’ (LIII, 31) and written in a ‘quite plain’ style (LI, 143), turned out to be disproportionately long and, as A. Walton Litz notes, the novel’s ‘climax’ of ‘stylistic development’ (1974, 386).

Joyce did not work on ‘Ithaca’ in isolation from other episodes. Michael Groden notes that in ‘the last stage’, that is, while writing ‘Circe’ through ‘Penelope’, Joyce ‘returned to the early- and middle-stage episodes and revised them considerably, almost always by adding’ (1977, 166). In a letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver, dated 7 August 1921, Joyce writes of fleshing out ‘Ithaca’ and beginning ‘Penelope’. This marks a break from work on the episode, which began in February. It also marks the transition into the following drafting stage, as Joyce notes in the letter that ‘Ithaca’ now needs to be ‘completed, revised and rearranged’. From that point Joyce often accompanies mentions of ‘Ithaca’ with plans to ‘put […] into shape’ (LIII, 48) and ‘put in order’ (LIII, 49). In his letters, Joyce punctuates the switch between ‘writing’ and ‘putting in order’ or ‘rearranging’, suggesting the proto-draft and fair copy belong to different stages of composition with different goals.

It is important to note that there is no way to show, nor is it likely, that the proto-draft is a direct genetic antecedent to the fair copy draft. Luca Crispi notes that the ‘relatively stable manner’ of the text in the fair copy means that Joyce likely ‘revised and expanded’ some sections ‘on one or more missing intermediary manuscripts’ (2015, 205). While this sounds alarming—how is it possible to analyse missing material?—in reality, the discovery of additional manuscripts would only increase the resolution of the analysis. For now, we must carry on with what is available, being careful to not make too many assumptions.

The versos of the folios in the proto-draft notebook were initially left blank for later insertions (JJDA ‘Draft Analysis Ithaca’). The writing is marked up with three colours of crayon: blue is used to demarcate the divisions between paragraphs, which Joyce later crossed out in blue, red and green colours to note their being incorporated into the following draft (Van Hulle 2021, 170). The writing continues until the second-to-last recto. Most pages have ample insertions on the verso, but for the last two. This suggests that the manuscript was a stop along the way to a more developed draft. Joyce uses it to flesh out ideas and copy in material, but moves on before ‘finishing it’—the writing stops arbitrarily.

Fig. 7.1 Folio 7v and 8 of NLI 13 (James Joyce, Partial draft: ‘Ithaca’, National Library of Ireland, MS 36,639/13, https://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000357810/, reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland). Note the consistently widening margin with additions on page 8. Further additions, one of them marked with siglum ‘W’, made on 7v.3

The previous description of the proto-draft as a pile of LEGO bricks turns out to be a powerful metaphor that renders visible the text in motion. The ‘bricks’ in question are paragraphs, their boundaries coinciding with the question-and-answer pairs inherent to a catechetical form. Daniel Ferrer and Jean-Michel Rabaté analyse paragraphs ‘in Expansion’, noting their ‘relative stability’ (2004, 142) in Joyce’s Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. The paragraph break is of special interest to Ferrer and Rabaté since it lies between ‘linguistic’ and ‘iconic’ divisions (2004, 135), that is, between the grammatically necessary border of a sentence and the arbitrary end of a page. Paragraph breaks bear properties of both fixity and arbitrariness:

They are deliberate and somehow gratuitous because, as we have noted, they are prescribed by no clear rule. Above all, they are not a separation from the exterior but an inner separation. We are therefore dealing with a border, but an attenuated border, less irrevocable than the others. (Ferrer and Rabaté, 2004, 135)

Yet here the border is not ‘attenuated’, nor ‘less irrevocable’—in the proto-draft, Joyce forcefully demarcates the paragraphs with crayon (see Figure 7.1). This separation allows us to consider each question-and-answer paragraph as a textual ‘unit’ or ‘block’ that is moved around in the process of rearrangement. But, as we will see, even these forceful graphical divisions are not as final as they seem—as Ferrer and Rabaté note, ‘[the paragraphs] show themselves to be open to fissures, scissions, and doubling’ (2004, 142).

Despite making up half the length of the fair copy, the proto-draft covers much of the same material. That is, if we rearrange the textual blocks—the question-and-answer pairs—to match the ordering of the fair copy, the resulting distribution is surprisingly even from start to end. The fair copy has many additional blocks, but these are inserted consistently in between the proto-draft ones. The average ‘gap’, that is, the number of blocks inserted between subsequent ones, is around two, with the most common value being one, and extremes of ten and twelve. Regarding structural matters, Joyce had almost everything he needed before moving onto the next drafting stage. Whichever way he proceeded—either rearranging blocks and then writing insertions or writing them as he was rearranging—the basic structure of the episode results directly from proto-draft material.

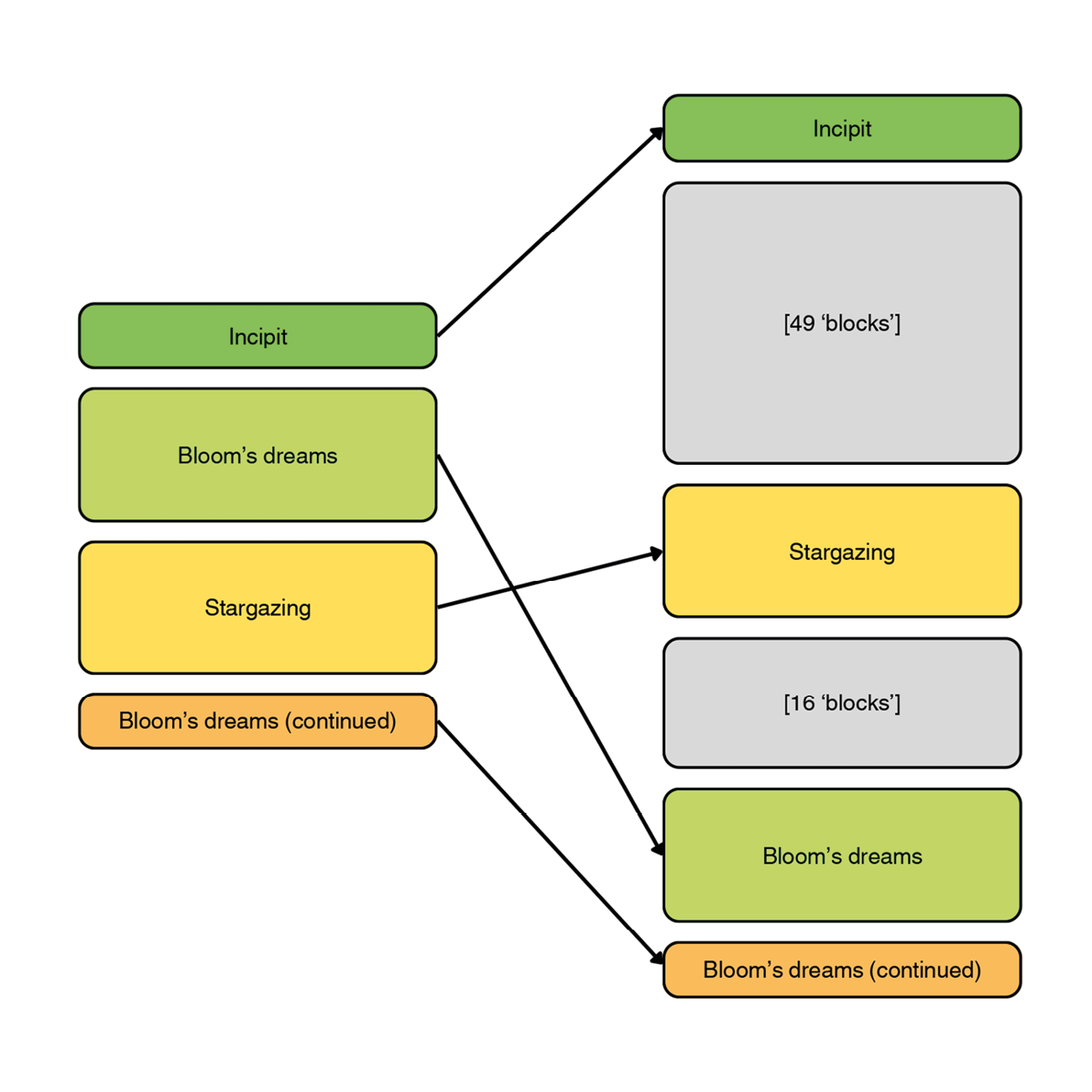

This material is highly unordered, however, as can be seen in the illustration below.4 The column on the left represents four sections that begin the proto-draft. On the right are the same blocks, but in the way they are ordered in the fair copy:

Fig. 7.2 Schematic illustration of text rearrangement and expansion from the proto-draft to the fair copy. Blocks on the left represent the content and ordering of the opening folios of the proto-draft, on the right these are rearranged, or interspersed with additional content.

The first four thematic sections of the proto-draft (the blocks on the left in Fig. 7.2) are rearranged in the fair copy (the blocks on the right) and spaced out by material taken from later in the proto-draft, or newly inserted. Thus, for instance, ‘Bloom’s dreams’ jump over ‘Stargazing’ to form a coherent segment.

Despite some sections, such as Bloom’s dreams of a country house or the stargazing, being maintained intact, the rest is rearranged according to non-obvious principles. Two scholars who have commented on the proto-draft’s structure, Luca Crispi and Philip Keel Geheber, also call it ‘non-sequential’ (Crispi 2015, 182) and ‘disordered’ (Geheber 2017, 70). This also applies to the episode’s narrative. The key events of the fabula are present—Bloom and Stephen arriving at 7 Eccles Street, drinking cocoa, urinating in the garden, Stephen leaving, Bloom re-entering the house and going to bed—but they are not presented in that order. Though the incipit of arriving home is in place, Stephen leaves around a quarter of the way through, reappearing in later questions, and Bloom goes to bed after a third of the chapter. In order to see how the narrative was constructed, it is necessary to investigate how the textual units were rearranged.

The establishing of a narrative sequence is the most significant structural change the proto-draft undergoes before it takes its shape in the fair copy manuscript. In fact, the linear structure the episode acquires is so rigid that Joyce wrote the fair copy in five parts, alternating between two notebooks, and had it typed piecemeal without fear of needing to backtrack to rearrange the narrative sequence. Even though the fabula is the main thing established, this happens alongside narration and narrative text—here narratological analysis helps us distinguish what exactly was being moved, and what happened to tag along, so to speak. Two examples will demonstrate how this stability was achieved: large, preconceived sections were moved into a fixed order and at the same time expanded, while disparate textual units pertaining to the same topic or narrative strand were brought together to constitute new sections.

The first section, describing Bloom’s and Stephen’s journey home, confined to folio 2r (Proto), remains essentially fixed, providing both the first events of the fabula and the incipit of the narration. As we turn the page, the narrative thread is severed—3r and 2v are a digression into a description of Bloom’s dream countryside home. Folio 4r contains another question belonging to Bloom’s dream section, prompting several later additions on 3v that are marked for insertion right after it. The most substantial section on fol. 4r, however, is the one that marks Stephen’s departure and prompts Bloom’s solitary cogitations on loneliness and space. Most notable is that in the proto-draft, Bloom sees ‘the heaventree’ and ‘the lamp by her [Molly’s] bedroom window’ (Proto, fol. 4r) alone, unlike in the fair copy (RB, 15)—Joyce had not yet worked out (or made explicit) Stephen’s presence in these blocks. These three sections end up far apart in the fair copy ordering: the incipit remaining fixed, Bloom’s dreams are placed later in the draft and joined together, whereas the paragraphs on astrology now take place between Stephen and Bloom drinking cocoa and Bloom returning inside, alone (see Figure 7.2). The already formed sections provide the backbone for the reordering of the rest—later on in the proto-draft, when Joyce decides that Stephen and Bloom urinate together (Proto, fol. 11r), he reprises the motif of the light in Molly’s window (Proto, 10v) and inserts it in the middle of the stable astrology section in the fair copy (RB, 15).

Stephen’s presence in the proto-draft is instead built up gradually and disparately and only made continuous in the fair copy draft. First Joyce compares Bloom and Stephen’s ages on fol. 7r (Proto), then a page later Bloom is made to forego his special cup as a sign of hospitality to Stephen. On fol. 10r Bloom imagines Stephen is quietly composing a poem in his head, but only on fol. 11r is the later context of drinking cocoa established. The question and answer about their sitting positions, one of the earliest in the fair copy, is the last in the proto-draft. In this case, Stephen acts as the backbone—his presence, strewn all about the proto-draft, is made to coagulate into a new section. Instead of combining blocks pertaining to the same event, Joyce collects all the blocks involving Stephen as an actor.

At this point we should ask how this rearrangement was motivated, as it makes sense that Joyce had some conception of what the episode should be. Litz provides a rationale for the episode’s structure:

Clearly, he [Joyce] conceived of ‘Ithaca’ as a series of scenes or tableaux, not unlike the narrative divisions in ‘Circe’, and on the early typescripts he blocked out these scenes under the titles ‘street’, ‘kitchen’, ‘garden’, ‘parlour’, ‘bedroom’. We may consider the ‘narrative’ development of ‘Ithaca’ under these headings, since each scene builds to a revealing climax which forwards our understanding of both Bloom and Stephen. (1974, 398)

The ‘typescripts’ Litz is referring to are an extract of the episode prepared specially for Valery Larbaud. Joyce refers to them in a letter dated 30 October 1921: ‘My typist has sent you extracts (of course uncorrected) from the beginning and middle of Ithaca. In a few days she will send you extracts from the end’ (LIII, 51). This typescript, containing one question and answer per page, was prepared partly from what was already typed, partly directly from the fair copy manuscript (JJA v. 16, x–xi). The ‘titles’ which Litz is referring to are written in pencil, in Joyce’s hand according to Peter Spielberg (1962, 70–71), on pages where a change of scene occurs (TSE, 215; 216; 238; 248; 269). Curiously, the last title, ‘bedroom’, is only found on the carbon copy of the typescript. Since we know the episode already had its final narrative shape in the form of the fair copy manuscript, it is difficult to tell whether these ‘tableaux’ were a guiding principle Joyce followed as he composed, or whether he gravitated towards such an arrangement only as he was working out the structure of the episode. Van Hulle documents a similar phenomenon in the case of the chronotope in Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of The Day, calling it a ‘chicken-or-egg’ question (2022, 151). Since Joyce wrote the designations only after finishing the episode, it is unclear which conditioned which.

With the benefit of having access to the proto-draft, it is possible to draw stronger, but less specific principles for rearrangement. Instead of trying to apply an idealised, evenly divided schema in retrospect, we can try to reason about what kind of reordering the text necessitates. For example, Stephen’s explicit or implied presence in certain units means that they must be moved before his departure. Sure enough, in the fair copy, we only find two references to Stephen post-departure, both in Bloom’s retelling of his day to Molly. Likewise, the existence of sections which remain stable points to Joyce having preconceived ideas about structure, but some developments happen only as he was writing them out, such as the idea of Bloom and Stephen urinating in the garden while gazing at the stars. The combination of shared agents or topics brought certain blocks together, but a picture which could then be subdivided into ‘tableaux’ possibly only arose when Joyce was already finished with the reordering.

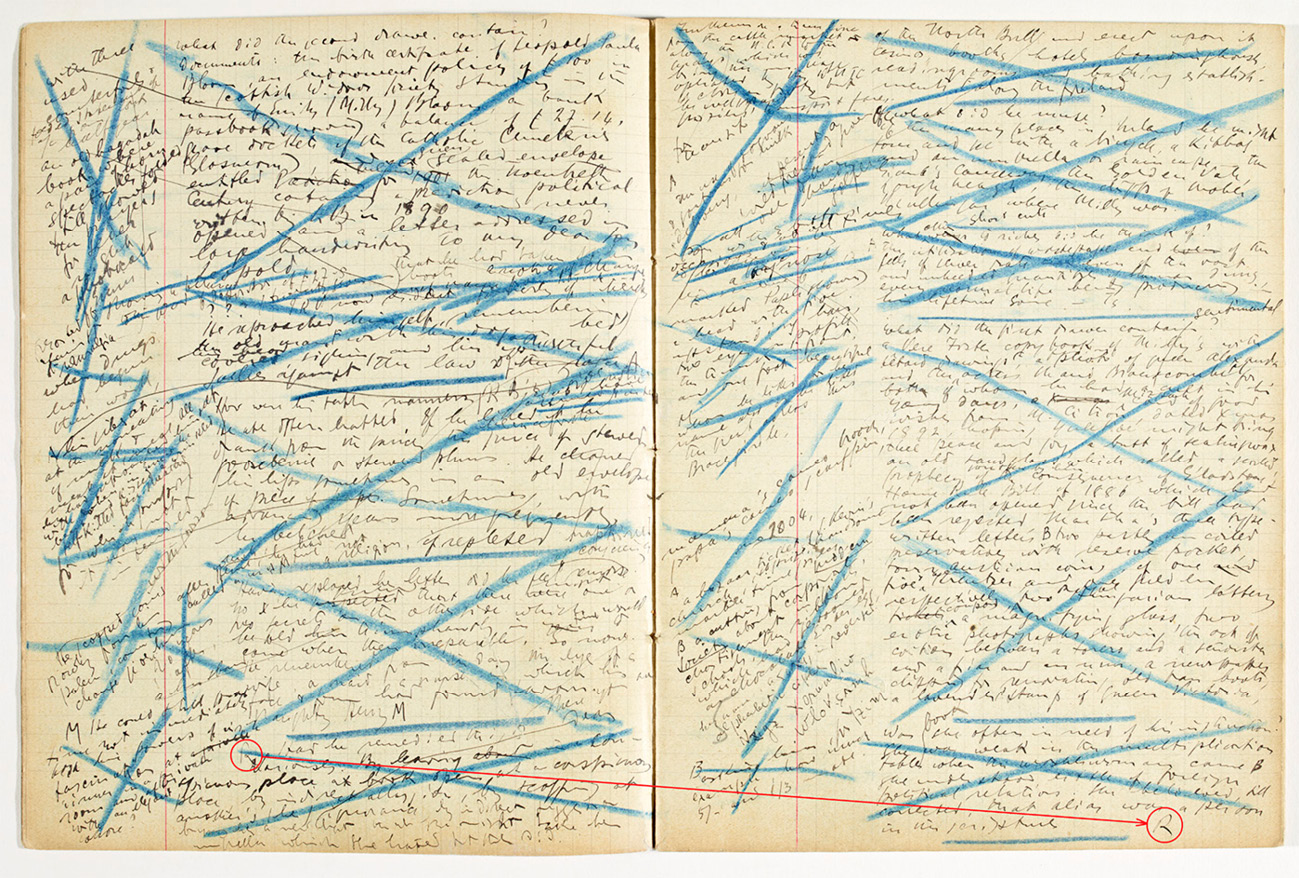

On a final note, it is interesting that some small and well-defined sections need no rearrangement—they are already explicitly ordered in the proto-draft. When returning to make additions in the margin or on the verso, Joyce often marks them with sigla to signal the precise place of insertion. Mostly this is confined to clauses within textual units, but sometimes Joyce marks entire question-and-answer pairs to be included before or after others. The insertion of ‘Could he foresee himself?’ on fol. 3v (Proto), marked to be inserted after the ‘Bloomville’ question, maintains its ordering in the fair copy (RB, 17). Likewise, Joyce inserts the final paragraph on fol. 4v right after the final one on fol. 5r (Proto), and the ordering is the same in the fair copy (see Figure 7.3). Another example is Joyce adding the ‘How did he enter?’ question on fol. 7v (Proto), but marking it for insertion on fol. 8r between ‘Did he set them right?’, referring to resetting inverted books, and ‘What did his stretching limbs feel?’ The sequence is now solidified—Bloom resets the books, enters the bed and then stretches. We can distinguish more than just sections which are either preconceived or unordered, since there are also new inventions which Joyce felt he needed to mark right there on the page.

Fig. 7.3 Addition on 4v in NLI 13 (James Joyce, Partial draft: ‘Ithaca’, National Library of Ireland, MS 36,639/13, https://catalogue.nli.ie/Record/vtls000357810/, reproduced courtesy of the National Library of Ireland), marked to be inserted after final block on fol. 5r. Red marking (my own) highlights the siglum ‘R’ used to mark place of insertion.

This suggests that the proto-draft, though ‘rudimentary’ (Crispi 2015, 205), is perhaps not so ‘non-sequential’ as Crispi describes it. He notes several instances of sections maintaining coherence (2015, 182; 205) and comments on how ‘unusual’ they are. The evidence of Joyce working out certain ordering explicitly on the proto-draft manuscript refines the picture. Copying in old material and writing new, Joyce was working in the context of both chance and structure. While the entire draft appears chaotic, it is no surprise that some blocks naturally inspired others and therefore they maintain their ordering during the movement to the subsequent drafting stage. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that the proto-draft was composed non-sequentially, or without a clear structure in mind, since the process of writing, inevitably, conditioned a sort of structure on the physical document.

Establishing narrative structure in ‘Ithaca’ can be seen as a process whose principles developed alongside the actual writing of the text. As Joyce gathered material in the proto-draft, it began to take shape right there on the page, with some sections clearly predestined to be self-standing, and others slowly elaborated over the course of writing. The view that Joyce had the episode laid out from the start, proposed by Litz, conflicts with the unstructured nature of the proto-draft and Joyce’s post-hoc scribblings on the typescript. On the other hand, the draft is not as ‘non-sequential’ as it first appears to Crispi and Geheber, as here and there it does show some strong structuring that persisted into the next drafting stage, sometimes even enforced graphically during a round of additions to mark that the material is already being structured in a non-arbitrary way. Joyce imbues the material with a narrative stability that makes the fair copy text cohere, but this proves to be only a starting point for a different kind of narrative development.

Disnarration and the Unnarrated: Taking the

Skeleton Apart

Constructing a coherent fabula and chronotope was clearly a priority for Joyce, but not the only one. As noted by Richard E. Madtes, around a third of ‘Ithaca’ was written in additions to the typescripts and proofs (1983, 36). As the episode expanded, its fabula remained the same, but the narrative effect changed significantly. Most of the work that resulted in ‘Ithaca’ being named the ‘ugly duckling’ of the book took place at this later stage—the first reference to the epithet appears in a letter to Weaver dated 25 November 1921 (JJC), just as Joyce was revising the episode’s typescript. Though the effect achieved by this expansion develops mostly in the typescripts and proofs, it is possible to trace the genesis of the narrative strategies at play to the proto-draft and fair copy.

‘Ithaca’, in the end, takes the route of anti-narrative. Take, for example, Karen Lawrence’s analysis: ‘Just as we are hoping for the resolution of the plot, then, the narrative opens up to include almost everything imaginable’ (2014, 192). Narrative is undone by its own mirror image, the hypothetical, which Gerald Prince christens the ‘disnarrated’ and defines as ‘events that do not happen, but, nonetheless, are referred to (in a negative or hypothetical mode) by the narrative text’ (1988, 2). Having arranged the ‘real’ fabula, the chain of cause and effect which drives the narrative to its end, Joyce was free to open many branching narratives situated in the hypothetical and the negative.

The hypothetical is not as developed in the proto-draft as it is in the published version, but we can retrace the textual sites where it is expanded in later writing stages. One key event in the fabula is Stephen declining to stay the night at Bloom’s house, which mirrors Bloom declining to have dinner at the Dedalus household twelve years earlier. While Bloom’s refusal is already laid out on fol. 12r (Proto), in the proto-draft Stephen leaves without first having refused to stay. The first trace of what would become the symmetrical response appears on fol. 14r:

Would they meet?

He wondered. He had no son. […]

Joyce continues with Bloom’s circus story—this story immediately follows the expanded version of those three short phrases in the fair copy (RB, 12). Then, Bloom and Stephen discuss possible locations for ‘Italian instruction’, ‘vocal instruction’ and ‘intellectual dialogues’ (RB, 11) that are ‘unlikely to take place’ (Killeen 2021, 271). By introducing Stephen’s denial, Joyce opens up the possibility of him accepting, and thus creates a rift into the disnarrated, which is expanded with plans that will not be realised. As the most important plot event in ‘Ithaca’, Stephen’s declining to stay is fittingly downplayed.

There are also small and significant changes from the indicative to the conditional, which again underline Joyce’s intention to understate and disnarrate. The question which prompts Molly’s list of lovers appears in its simplest form in the proto-draft: ‘He [Bloom] smiled?’ (Proto, fol. 11r). The version which appears in the fair copy, and is brought forward unchanged into the published version, is cast into the hypothetical: ‘If he had smiled why would he have smiled?’ (RB, 27). Even an insubstantial smile, seen by no one, is dedramatised and rendered purely mental, reflecting the episode’s tendency to narrate more of what does not happen, instead of sticking to what does. Simple additions like ‘Duel he wd not’ (Proto, 14) not only add to characterisation, as is one of the functions of disnarration according to Prince (1988, 4), but also work against the fabula by drawing textual and narrative attention away from it. Prince paraphrases Claude Bremond: ‘every narrative function opens an alternative, a set of possible directions’ (1988, 5). Joyce exploits this feature of narrative events to its fullest extent in ‘Ithaca’ by prioritising a non-linear web of hypotheticals instead of cause-and-effect narrative.

Killeen describes the episode as producing ‘the effect […] of beings looking down from the heavens, from an enormous distance, on the affairs of humans, indifferent to the phenomena which they merely observe and report’ (2021, 276). This results from the tension between focalisation—‘the relation between the vision and what is seen, perceived’ (Bal 2017, 133)—and the unnarrated. Prince defines the unnarrated as ‘ellipses […] inferable from a significant lacuna in the chronology’ (1988, 2). A genetic reading, especially of an early manuscript, affords a luxury unavailable to other readings: the ability to distinguish between lacunae to be filled in and the unnarrated. Graphically, there is little difference between a dash which signifies a halt in narration, and a placeholder dash, destined to be filled in in making a fair copy, rendering the wording precise. In the proto-draft, these two overlap, and it is therefore possible to trace the development (or undoing) of the unnarrated.

For instance, returning to Molly’s ‘list of lovers’ on fol. 11r (Proto), we can see that ‘the most famous list in Ulysses’ (Kenner, qtd. in Crispi 2015, 264) is little more than five names and eight dashes:

It amused him that each man fancied himself the first to enter the breach whereas he was the last of a series through Penrose, -- -- -- --, Bloom, Holohan, Bodkin, Mulvey, -- -- -- --

Crispi comments that ‘the list’s trajectory suggests that it was never intended as an accurate enumeration of Molly’s lovers, few as they actually are’ (2015, 265). Furthermore, Crispi asserts that the dashes are ‘merely reminders to fill in the names later on’ (2015, 265). Here the early state of the proto-draft confirms a certain reading by underlining the relative unimportance of the elements to the form, the unnarrated is dissipated.

The effect is different when considering Bloom’s thoughts as he enters the bed. On fol. 7v (Proto) Joyce writes the following:

How did he enter?

Prudently. […] it was the bed in which she –

Then in the margin he adds:

had been conceived […], in which her marriage had been consummated and in which [blank]5

Crispi notes that, at first leaving ‘the point incomplete (or simply unstated)’, Joyce’s later addition again leaves ‘the rest of the line unfinished’ (2015, 264). The unnarrated creeps into the working draft, as if Bloom were subconsciously blocking thoughts about Boylan sleeping with Molly. The line is finished in the fair copy: it becomes ‘the bed of conception and birth, of consummation of marriage and breach of marriage, of sleep, of death’ (RB, 26). Again, the unnarrated becomes narrated, but here it subtly alters the focalisation, shifting it away from Bloom and closer to Killeen’s ‘beings looking down from the heavens’.

Through the expansion or elaboration of the techniques of disnarration and the unnarrated, ‘Ithaca’ loses much of its capacity for signification on a ‘human’ level. Disnarration ceaselessly directs narration away from the fabula, on which it prefers to remain silent, while the unnarrated is systematically removed and thus the tension that arises from focalisation and narration—the excitement and mystery of not being told everything that is seen—is destroyed. The narration of the unnarrated closes off possibility, the opposite of disnarration’s plunge into every possibility. The skeleton, as much as it is an organ where each bone has its right place to give a supporting structure for the rest, is taken apart and rendered useless by these techniques which condition this ‘most detached’ and ‘indifferent’ episode.

Vestigial Structure

Up to this point, the reading of the proto-draft has been teleological. That is to say, the forces structuring and, at the same time, undermining its structure were considered keeping in mind a telos, an ‘end goal’—the structure and effect of the fair copy draft. But this is only one side of the coin, which presupposes publication, or at least the next drafting stage, before it actually happens. In this case it presupposes the very document of the fair copy before its creation—our reading of the proto-draft may be influenced by ‘prescient’ knowledge of the fair copy. In order to read, to repeat Van Hulle’s usage of Ernst Haeckel’s term, dysteleologically (2022, 168), we have to pay attention to the purposes a draft serves for itself, or how its purpose changes up to the point when the next drafting stage takes place.

In any draft, material not carried over into the next drafting stage has dysteleological properties. Van Hulle proposes to label such material ‘vestigial’ (2022, 170). But he also notes that vestigial material ‘had a purpose at some point or at some stage in the evolution of the work’ (2022, 172). Examining the proto-draft, we find material that was reused in different shapes, partially recycled, or entirely scrapped. Some material provides concrete examples of an idea being worked out in multiple forms before becoming stable, or, more intriguingly, of how the ‘telos’ changes between different drafting stages. By examining these ‘vestigial bones’ (Van Hulle 2022, 170) which do not fit the final design, a more ambiguous, differently shaped ‘Ithaca’ will be shown.

Joyce wants to write about Bloom shaving but keeps changing his mind on what exactly to write. The topic is brought up a total of three times in the proto-draft, each time receiving different treatment. The first time it is an aside to a thematically separate paragraph, prompted by comparison of women to stars, and from then comparing men and women: ‘man not knowing the pleasure of hair combing, woman not knowing the luxury of a cool shave’ (Proto, fol. 3v). The second appearance seems unprompted and even isolated from other blocks in on the verso of fol. 7r:

Could he shave with such felicity?

Even in the dark by the sense of touch. He had a firm full sure woman’s hand. He could have been a successful surgeon but that he would have preferred to be a physician, being loath to shed men’s blood even when the end justified the means.

Here Bloom’s hand is compared to a woman’s and his hypothetical career as a surgeon is mentioned, but the context of comparing men and women of the previous instance is missing. The third time shaving is brought up appears the most cogent and developed (Proto, fol. 15r)—it is also the clear antecedent of the version found in the fair copy (RB, 5). None of these appear in the context in which the shaving block ends up—alongside Bloom boiling water for the cocoa to have with Stephen. Though some of the material ends up being used, other parts, such as the reference to shaving, fall away like scaffolding, and the block is moved into a context which does not resemble what prompted the question in the first place.

Another example is the reprise of the ‘Throwaway’ narrative. In the proto-draft, a block disconnected from the surrounding ones tells of Bloom rediscovering the winner of the race in Ascot:

What did he discover from this connection?

Opening the paper the at the telegraph by special wire page he found that the Gold Cup race at Ascot had been won by a dark horse Throwaway at 20 to 1. (Proto, fol. 11v)

This story strand runs throughout the novel and is mentioned in nearly every episode, so naturally ‘Ithaca’ references it as well. Strangely enough, if we turn to the fair copy, the block is absent. Instead, the story has now morphed into one of Bloom’s ‘rapid but insecure means to opulence’, i.e. cheating by receiving ‘a private wireless telegraph’ (RB, 19) with the results of the race ahead of time. In this version, the cup is won by ‘an outsider at odds of 50 to 1 3 hr 8 p.m at Ascot (Greenwich time)’ (RB, 19). It is apparent that the ‘Throwaway’ version provided the inspiration for Bloom’s scheme in the fair copy—words like the struck-out ‘telegraph’, or ‘wire’ and ‘dark horse’ are echoed in ‘wireless telegraph’ and ‘an outsider’. Even though the ‘Throwaway’ story itself is not found in the fair copy, it provides the vocabulary and the impetus to generate a different narrative. It is not found in the fair copy but is necessary for its creation.

Except both the unused shaving and Throwaway material do end up being used, just not in the fair copy. In the drafting stage following the fair copy, the typescript, Joyce immediately re-adds both the original ‘Throwaway’ story, the comparison of Bloom’s hand to a woman’s and his potential as a surgeon (TS, u21, 747; TS, u21, 746). Though both blocks end up having an ‘end goal’, their way into the text is not straightforward. Even more, this is a direct result of the fissile nature of paragraphs, as pointed out by Ferrer and Rabaté above. Here we see different teloi fighting for centre stage. Gabler notes that the production of the fair copy that was to be typed up was a rushed process due to tight deadlines and Joyce’s wish to have the episode read in Larbaud’s séance (JJA v. 16, x). As noted in the first section, the fair copy appears to be the result of Joyce’s repeated wish to put ‘Ithaca’ ‘in order’, and here is evidence that this goal was pursued even to the temporary detriment of textual stability. Joyce ended up foregoing some material in order to get the ‘skeleton’ in place, with a clear eye where to put the material back in once the typescript was done. The material is vestigial with regard to establishing structure, but once that goal is achieved, it can enter back into play.

This force disrupts straightforward consideration of the episode as an ‘evolving’ organism. Though it is clear that the proto-draft was reordered with a view to establish narrative coherence, and that Joyce expanded the hypothetical and unnarrated dimensions in order to undermine the significance of the fabula, some other processes do not follow the straight path towards their goal, nor do they always have one. The shaving block eventually ‘found its way’ into the published version, but not without a substantial detour and temporary ‘vestigial’ status. It is precisely the fact that the block was unnecessary that underlines what goal Joyce had in mind while writing the fair copy—a narratively stable text he could later add to.

Conclusion

The genesis of the narrative structure of ‘Ithaca’ involved several different lines of development which interact to support or undermine each other. At the same time as the fabula is set in place, disnarration steers the reader away from it; as soon as we spot a repeating narrative motif, such as the ‘Throwaway’ story, we also find out that it was wholly unnecessary to the ‘skeleton’, only re-added after the structure was established. We can trace the evolution of ‘Ithaca’ and see how it achieves its effects of distance and detachedness via textual accretion, but also recover lacunae which had to be filled in. The incredible heterogeneity of the writing process seems to rear its head as soon as any generalising assumption is made, showing the text-in-progress to be both unstable, not yet settled, as well as rigid, already conceived, even ‘a projection into the future’ (Van Hulle 2022, 171).

The most obvious conclusion to make is that the ‘skeletal’ model of structure does not work to describe ‘Ithaca’. A skeleton is a collection of bones, where each bone fits with others in a predetermined way, whereas the episode is constructed from blocks which can be inserted any way around, and, as seen in the final section, often are. ‘Ithaca’ may have a story, a backbone which drives the narrative forward, but it cracks and groans under the weight of the episode’s style and ever-expanding paragraphs. The schemata restrain the novel’s motility—only by cracking open the bones of the ‘skeleton’ is it possible to get to the episode’s ‘Juices’, as is the designated ‘organ’ in the Linati schema.

Returning again to the schemata investigated at the beginning, a broader question may be asked—what do we need them for? Killeen notes that, due to discrepancies, ‘the [Gilbert] schema’s authority is slightly compromised’ (2021, xv), but he still reproduces it at the end of his introductory A Reader’s Companion to James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses’. The OWC edition of Ulysses instead chooses to reproduce both alongside the 1922 text—a pleasure which readers at the time of publication did not get to enjoy, as the first schema was printed only in 1931. The schemata close the text off; in order to open it back up it is necessary to ask, why do the schemata give different ‘organs’ for the same episode?

That question, inevitably, leads back to the text, itself existing in many iterations. The proto-draft cannot easily be read as a narrative, nor is it meant to be treated as one. Being aware of its reordering undermines its stability, but also opens it up anew, this time to the reader instead of the writer. Perhaps it is the possibility of moving along with the text, rather than leaning on calcified structures like the schemata, that can bring the reader closer to Ulysses.

List of Abbreviations

|

JJC |

James Joyce Correspondence, ed. by William Brockman et al., jamesjoycecorrespondence.org |

|

JJDA |

James Joyce Digital Archive, ed. by Danis Rose and John O’Hanlon, jjda.ie |

|

LI, LII, LIII |

Joyce, James (1957-1966), Letters of James Joyce, ed. by Stuart Gilbert, Richard Ellmann and James Fuller Spoerri, 3 vols. (London and New York: Faber & Faber; Viking). |

|

NLI 13 |

Joyce, James, MS. 36,639/13, Partial Draft: ‘Ithaca’, National Library of Ireland. |

|

Proto |

Joyce, James, MS. 36,639/13, ‘u17.1 (proto-text)’, in: James Joyce Digital Archive, ed. by Danis Rose and John O’ Hanlon, transcription of National Library of Ireland, https://jjda.ie/main/JJDA/U/ulex/s/s11d.htm. |

|

RB |

Joyce, James, ‘Ithaca’ Blue and Green MS., ‘u17.2 (Rosenbach)’, in: James Joyce Digital Archive, ed. by Danis Rose and John O’ Hanlon, transcription of Rosenbach Museum, https://jjda.ie/main/JJDA/U/ulex/s/s12d.htm. |

|

SL |

Joyce, James (1975), Selected Letters of James Joyce, ed. by Richard Ellmann (London: Faber & Faber). |

|

TS |

Joyce, James, MS. V.B.15.c, ‘u17.3 (Gabler-B)’, in: James Joyce Digital Archive, ed. by Danis Rose and John O’ Hanlon, transcription of University at Buffalo Libraries, https://jjda.ie/main/JJDA/U/ulex/s/sd3.htm. |

|

TSE |

Joyce, James (1977), ‘“Ithaca” Typescript Extracts’, in: Ulysses, Vol. XVI: “Ithaca” and “Penelope”: a Facsimile of Manuscripts and Typescripts for Episodes 17 and 18, prefaced and arranged by Michael Groden, James Joyce Archive (New York: Garland Pub.), 215–290. |

These works are cited in parentheses without author or date information for readability.

Works Cited

Bal, Mieke (2017), Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative, trans. by Christine van Boheemen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press).

Crispi, Luca (2015), Joyce’s Creative Process and the Construction of Characters in Ulysses: Becoming the Blooms (Oxford: Oxford University Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198718857.001.0001.

Ellmann, Maud (2008), ‘Ulysses: The Epic of the Human Body’, in: A Companion to James Joyce, ed. by Richard Brown (Malden, MA and Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405177535.

Ferrer, Daniel and Jean Michel-Rabaté (2004), ‘Paragraphs in Expansion’, in: Genetic Criticism: Texts and Avant-textes, ed. by Jed Deppman, Daniel Ferrer and Michael Groden (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press).

Fludernik, Monika (1986), ‘“Ulysses” and Joyce’s Change of Artistic Aims: External and Internal Evidence’, James Joyce Quarterly, 23.2: 173–88.

Gabler, Hans Walter (1984), ‘Afterword’, in: James Joyce, Ulysses: A Critical and Synoptic Edition, vol. 3, ed. by Hans Walter Gabler, Wolfhard Steppe and Claus Melchior (New York and London: Garland Pub.), 1859–1908.

Geheber, Philip Keel (2018), ‘Filling in the Gaps: “Ithaca” and Encyclopedic Generation’, James Joyce Quarterly, 55.1/2: 59–78, https://doi.org/10.1353/jjq.2017.0029.

Groden, Michael [1977] (2014), Ulysses in Progress (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press).

Joyce, James, MS. 36,639/13, Partial Draft: ‘Ithaca’, Dublin: National Library of Ireland.

Joyce, James (1977), ‘“Ithaca” Typescript Extracts’, in: Ulysses, Vol. XVI: “Ithaca” and “Penelope”: a Facsimile of Manuscripts and Typescripts for Episodes 17 and 18, prefaced and arranged by Michael Groden, James Joyce Archive (New York: Garland Pub.), v. 16, 215–90.

Joyce, James, MS. 36,639/13, ‘u17.1 (proto-text)’, in: James Joyce Digital Archive, ed. by Danis Rose and John O’ Hanlon, transcription of National Library of Ireland, https://jjda.ie/main/JJDA/U/ulex/s/s11d.htm.

Joyce, James, ‘Ithaca’ Blue and Green MS., ‘u17.2 (Rosenbach)’, in: James Joyce Digital Archive, ed. by Danis Rose and John O’ Hanlon, transcription of Rosenbach Museum, https://jjda.ie/main/JJDA/U/ulex/s/s12d.htm.

Joyce, James, MS. V.B.15.c, ‘u17.3 (Gabler-B)’, in: James Joyce Digital Archive, ed. by Danis Rose and John O’ Hanlon, transcription of University at Buffalo Libraries, https://jjda.ie/main/JJDA/U/ulex/s/sd3.htm.

Joyce, James (1957–1966), Letters of James Joyce, 3 vols., ed by. Stuart Gilbert, Richard Ellmann and James Fuller Spoerri (London and New York: Faber & Faber; Viking).

Joyce, James (1975), Selected Letters of James Joyce, ed. by Richard Ellmann (London: Faber & Faber).

Joyce, James (2023), Ulysses, ed. by Jeri Jonson, New edn. (Oxford: Oxford University Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/owc/9780192855107.001.0001.

Joyce, James (1993), Ulysses, ed. by Hans Walter Gabler, Wolfhard Steppe and Claus Melchior, afterword by Michael Groden (New York: Vintage Books).

Killeen, Terence (2022), Ulysses Unbound: A Reader’s Companion to James Joyce’s Ulysses, New edn., prefaced by Colm Tóibín (London: Penguin Books).

Lawrence, Karen [1981] (2014), The Odyssey of Style in Ulysses (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press). https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400855773.

Litz, A. Walton (1974), ‘Ithaca’, in: James Joyce’s Ulysses: Critical Essays, ed. by Clive Hart and David Hayman (Berkeley: University of California Press), 385–407.

Litz, A. Walton (1961), The Art of James Joyce: Method and Design in Ulysses and Finnegans Wake (London: Oxford University Press).

Madtes, Richard E. (1983), The “Ithaca” Chapter of Joyce’s Ulysses (Epping: Bowker).

Prince, Gerald (1988), ‘The Disnarrated’, Style, 22.1: 1–8.

Spielberg, Peter (1962), James Joyce’s Manuscripts and Letters at the University of Buffalo: A Catalogue (Buffalo, NY: University of Buffalo).

Van Hulle, Dirk (2022), Genetic Criticism: Tracing Creativity in Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press). https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192846792.001.0001.

1 For abbreviations see the list of Works Cited.

2 Respectively by James Joyce Digital Archive and Crispi, 2015.

3 I wish to thank James Harte (NLI Special Collections) for granting the rights to reproduce these pages (personal correspondence 4 April 2024).

4 I thank Dirk Van Hulle for the suggestion of this visualisation.

5 Here, the preferred reading is Crispi’s instead of JJDA.