1. Introductory

©2025 Ruth Finnegan, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0428.01

What is man’s body? It is a spark from the fire

It meets water and it is put out.

What is man’s body? It is a bit of straw

It meets fire and it is burnt.

What is man’s body? It is a bubble of water

Broken by the wind.

(Gond song from Central India, recorded in the 1930s when the Gond could be described as ‘one of the poorest peoples on earth’. Elwin and Hivale, 1944, p. 255)

Many days of sorrow, many nights of woe,

Many days of sorrow, many nights of woe,

And a ball and chain, everywhere I go.

Chains on my feet, padlocks on my hands,

Chains on my feet and padlocks on my hands,

It’s all on account of stealing a woman’s man.

It was early this mornin’ that I had my trial,

It was early this mornin’ that I had my trial,

Ninety days on the county road, and the judge didn’t even smile.

(‘Chain gang blues’ poem, published in Hollo, 1964, p. 11)

A wonderful occupation

Making songs!

But all too often they

Are failures...

(From Piuvkaq’s poem ‘The joy of a singer’, translated from the Inuits in Rasmussen, 1931, p. 511)

These poems, and those from similar backgrounds, are not usually studied in courses on ‘literature’ or included in discussion of the sociology of literature and art. If mentioned at all, they are likely to be placed in some special category—like ‘oral tradition’, or ‘folklore’ or perhaps ‘popular culture’. This firmly separates it from mainstream literature as something with its own rationale but which, while no doubt splendid in its own terms, need not be taken into account when discussing literature proper. Equally, such poems are rarely considered significant for the sociology of literature, since such oral literary forms are presumed to be natural, communal and unconsidered, and relatively free from the constraints of social differentiation, of prescribed roles or socially recognised conventions—things the sociologist looks for. As a result, oral poetry has often been ignored both in literary study and (still more, perhaps) in the sociology of literature, and, generally speaking, assumed to be of merely marginal interest. It is a common assumption that it is best relegated to ‘folklore’ studies, or specialised ethnographies, or left to those concerned to propagate ‘popular’ or ‘underground’ culture.

And yet there is a great amount of oral poetry already recorded and still being performed, in addition to the instances documented from the past, and interest in these forms seems to be increasing. It is difficult to argue that they should be ignored as aberrant or unusual in human society, or in principle outside the normal field of established scholarly research. In practice there is everything to be gained by bringing the study of oral poetry into the mainstream of work on literature and sociology.

It is a basic contention of this book that the nature of oral poetry is such that its study falls squarely within the field of literature; it can throw light on literature ‘proper’ (understood as written literature) and is also part of literature as it is most generally understood. What is more, there is no clear-cut line between ‘oral’ and ‘written’ literature, and when one tries to differentiate between them—as has often been attempted—it becomes clear that there are constant overlaps. Contrary to earlier assumptions which classed forms like those quoted as items of ‘oral tradition’, ‘folklore’ or ‘traditional formulae’, there proves to be no definitive and unitary body of poetry which, being oral, can be clearly differentiated from written and, as it were, ‘normal’ poetry.

One consequence of the questioning of this assumed special and different category of oral literature is that the assumptions about oral literature which made it seem inappropriate for sociological enquiry fall to the ground. There is no reason for assuming that all oral poetry is necessarily artless, ‘close to nature’, shared by the whole ‘tribe’ or ‘community’ equally, and so on. In practice, and contrary to the concept of oral literature given by many romantic writers of the traditional folklore school, the normal questions in the sociology of literature can equally, and most pertinently, be asked of oral poetry. Indeed it should surely become a major task of sociological analysis to include the scrutiny of oral and literary forms within society—whether in a non-literate, or a literate and ‘modern’ context—and thus to help redress the impression so often gained from sociological writing of intellectual and artistic barrenness in the cultures described. People are moved not only by economic or political factors and groupings, but also by artistic ones. Whether sociology is concerned with ‘meaning’ (as is often claimed) or with ‘play’ (as Huizinga would have had it) or with the social functions of institutions, some analysis of oral literary forms within society is an important aspect of the sociologist’s task.

Fig. 1.1. The multi-generic Greek Muses: mosaic with symbols of each Muse, and Mnemosyne (Memory), first century B.C. Archaeological Museum of Elis, Greece. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:

Nine_muses_and_mnemosyne_symbols_disc_from_elis_greece.jpg

In this area as in others, a comparative perspective can be illuminating. Within literature one can learn much, for instance, by considering Homer in the light of findings about recent Yugoslav oral epic poetry or about Inuit or Gilbertese poets or modern blues singers. Similarly, some aspects of poetry may prove not to be peculiar to, say, Homer or Piuvkaq or ‘Left Wing Gordon’, or even (as suggested in some linguistic work) to ‘Indo European culture’, but to be practised and performed in many areas of the world. A comparative perspective can lead to awareness of the complexity and diversity of forms throughout human culture and history, and cast doubt on some crude dichotomies used by social scientists in the past—that between ‘civilised’ as against ‘primitive’ and ‘simple’ society, for instance; or Gesellschaft opposed to Gemeinschaft; or ‘modern’ as against ‘traditional’ culture. This emphasis on the relevance of comparative material and on the complexity and absence of rigid uniformity in oral poetry is one recurrent theme of this book.

1.1 The importance of oral poetry

Oral poetry is not an odd or aberrant phenomenon in human culture, nor a fossilised survival from the far past, destined to wither away with increasing modernisation. In fact, it is of common occurrence in human society, literate as well as non-literate. It is found all over the world, past and present, from the meditative personal poetry of recent Inuit or Maori poets, to mediaeval European and Chinese ballads, or the orally composed epics of pre-classical Greek in the first millennium B.C. One can compare the twentieth-century love lyrics of the Gond poet

As in a pot the milk turns sour,

As silver is debased,

So the love I won so hardly

Has been shattered since you have betrayed me

(Hivale and Elwin, 1935, p. 128)

or

Jump over the wall and come to me,

And I will give you every happiness.

I will give you fruit from my garden,

And to drink, water of Ganges.

Jump over the wall and come to me,

I will give you a bed of silk,

And to cover you a fair, fine-woven cloth,

Only jump over the wall and all delight shall be yours.

(Hivale and Elwin, 1935, p. 118)

to those of the mediaeval troubadours, the stanza, for instance, from Jaufre Rudel’s love-lyric in the twelfth century

Love from a far-off land,

For you all my being aches;

I can find no remedy for it

If I do not hear your call

With the lure of soft love

In an orchard or behind curtains

With my longed-for beloved

(Dronke, 1968, p. 119)

Again, one can draw parallels between the epic poetry of Homer or mediaeval romances, and that of recent oral poets in Yugoslavia or Cyprus or the Soviet Union. One can contrast the condensed imagery of a recent Somali ‘miniature’ lyric like

A flash of lightning does not satisfy thirst,

What then is it to me if you just pass by?

(Andrzejewski and Lewis, 1904, p. 146)

to the lengthy and high-flown praise-poem about the famous nineteenth-century Zulu warrior Shaka, a panegyric extending to some hundreds of lines

Dlungwana son of Ndabal

Ferocious one of the Mbelebele brigade,

Who raged among the large kraals,

So that until dawn the huts were being turned upside-down…

(Cope, 1968, p. 88)

Oral poetry is not just something of far away and long ago. In a sense it is all around us still. Certainly in most definitions of oral poetry, one should also include the kinds of ballads and ‘folksongs’ (both those dubbed ‘modern’ and ‘traditional’) sung widely in America or the British Isles, Black American verse, the popular songs transmitted by radio and television, the chanted and emotional verse of some preachers in the American South, or even the kind of children’s verse made familiar in the Opies’ collection. The British school-child’s jeer

That’s the way to the zoo,

That’s the way to the zoo,

The monkey house is nearly full

But there’s room enough for you

(Opie, 1967, p. 176)

is parallel in some respects to the children’s song of abuse recently recorded in West Africa

The one who does not love me

He will become a frog

And he will jump jump jump away

He will become a monkey with one leg

And he will hop hop hop away.

(Beier and Gbadamosi, n.d.) (Yoruba)

Even well-known carols and hymns—’Once in royal David’s city’, ‘Away in a manger’, ‘There is a green hill far away’—can be regarded as oral poetry in contemporary circulation: for though they also appear in written form, they surely achieve their main impact and active circulation through ever-renewed oral means.

It is easy to overlook such oral poetry. This is a special temptation to the scholar and those committed to ‘high culture’ whose preconceptions all tend to direct attention towards written literature as the characteristic location of poetry. Oral forms are often just not noticed—particularly those which are near-by or contemporary. A much-quoted instance of this is the experience of Cecil Sharp, the famous collector of English ‘folk songs’, at the beginning of this century. He wrote:

One of the most amazing and puzzling things about the English folk song is the way in which it has hitherto escaped the notice of the educated people resident in the country districts. When I have had the good fortune to collect some especially fine songs in a village, I have often called upon the Vicar to tell him of my success. My story has usually been received, at first, with polite incredulity, and, afterwards, when I have displayed the contents of my notebook, with amazement. Naturally, the Vicar finds it difficult to realize that the old men and women of his parish, whom he has known and seen day by day for many a long year, but whom he has never suspected of any musical leanings, should all the while have possessed, secretly treasured in their old heads, songs of such remarkable interest and loveliness.

(Sharp, 1972 (first published 1907), p. 131)

This experience has often been repeated by collectors trying to discover and record local oral poetry, and in some countries—England is one example—the study of local contemporary oral forms is still largely unrecognised and neglected by formal university scholarship.

Oral literature produced in the past on the other hand, has seemed more acceptable as a subject for scholarly study, provided the items have come down to us through the written tradition. So the analysis of the ultimately oral quality of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey or of the Epic of Gilgamesh have entered into accepted academic scholarship in a way that more recent oral art has not. Exotic examples too—the poetry produced by largely non literate peoples in Africa or Oceania—has attracted attention as, at the least, interesting examples of primitive literary forms, a suitable topic for anthropologists and ethnographers (even if not for literary scholars). Once collected and transmitted in written translations to a reading public, Zulu praise-poems or Maori lyrics seem obvious examples of oral poetry, just the type of thing to fit one popular picture of the ‘primitive unlettered singer’—even though to the local administrator or teacher they may have appeared of little interest, at best the artless and uninformed repetitions of tribal culture or the crude accompaniment to tribal dancing. Similarly the stress in ‘folklore’ collecting has, until recently, been on the ‘old’ and ‘traditional’, survivals from the rural past rather than contemporaneous and urban forms, and on the products of marginal and immigrant groups, surviving despite modern life rather than as part of it.

Much of the interest in oral forms has thus in the past been directed to what was far off in space or time, or had achieved scholarly recognition in authoritative collections of ‘traditional’ forms—the canonical nineteenth century collections of ballads by Child, for instance, rather than recently sung versions or hillbilly songs etc. So the importance of local and contemporary forms has been continuously underplayed. It must therefore be stressed at the outset that there is much more ‘oral poetry’ than is often recognised, at least if one takes a reasonably wide definition of the term. And it is not just a survival of past ages and stages; it is a normal part of our modern life as well as that of more distant peoples.1

For all the relative neglect of modern forms, oral poetry has interested many scholars throughout the world, amateur and professional. This interest has taken various forms. Under the name of’ folklore’, a flourishing movement for two centuries or so has collected and studied popular and ‘folk’ traditions, including poetry and song. Though it was initially directed to rural and supposedly ‘traditional’ forms in Europe and America, these being analysed largely in terms of an evolutionary and romantic model, some folklorists are now turning more to urban and ‘Third World’ forms in their studies. One recent study has treated the contemporary sermons chanted by preachers in the American South (Rosenberg, 1970) and a symposium of the American Folklore Society was specifically directed towards work in the urban context (Paredes and Stekert, 1971). In addition, collections of industrial songs (e.g. Lloyd, 1952; Korson, 1943), and so-called ‘protest verse’ (e.g. Greenway, 1953; Denisoff, 1966) are being recognised as part of folklore study: they are instances of oral poetry, to use the terminology preferred in this book. Classical and mediaeval scholars also discuss ‘oral poetry’, in work largely stimulated by the comparative research of Milman Parry and Albert Lord on the Homeric epics and more recent Yugoslav heroic poetry, so influentially expounded in Lord’s The Singer of Tales (first published 1960). This has led to discussion of the likely ‘oral composition’ of such poems as the Iliad and Odyssey, the Biblical psalms, the Chanson de Roland and Beowulf. By now too anthropologists and linguists (particularly those trained in America) often include the study of local oral literature as part of their subject, and this is recorded in a large number of publications. Writers such as Marshall McLuhan have drawn the attention of social scientists and others to the ‘oral’ nature of earlier cultures and of recent developments in communication patterns in our industrial world. The current interest in oral literature is augmented by the common connection between a ‘left wing’ or ‘progressive’ stance and a concern with ‘popular culture’ or ‘protest songs’ and (in some cases) the productions of modern radio and television. When one remembers, too, the many generations of collectors and annotators in country after country—linguists, missionaries, administrators, extra-mural teachers—it becomes clear that there is a great deal of interest in and information on the subject. It may not be systematised as a formal academic discipline, but there is no shortage of basic material.

Many emotions are also involved. For some, like the traditional folklorists and earlier anthropologists, the topic is closely connected with ‘tradition’, with nationalist movements or with the faith in progress which expresses itself in the theory of social evolution. For others it forms part of a left-wing faith and a belief in ‘popular’ culture, along with a revolt against ‘bourgeois art forms’ or ‘the establishment’. In others it goes with a romantic ideal of the noble savage and of the pure natural impulses which, it is felt, we have lost in the urban mechanical way of life today. Many of the positions taken up implicitly link with scholarly controversies about the development of society, the nature of art and communication, or various models of man. Oral poetry and its study is a complex and emotive study, involving many often disputed assumptions. The history of some of the approaches to the subject and the preconceptions behind them are worth looking at because they show what is being implied in statements and claims about the subject. This is set out a little later, in chapter 2. The present chapter considers some more general points about the nature of ‘oral poetry’ and the problems of studying it.

1.2 Some forms of oral poetry

The term ‘oral poetry’ sounds fairly simple and clear-cut. This is also the impression one gets from some statements about it. ‘Oral poetry’ is described in one authoritative encyclopaedia article as ‘poetry composed in oral performance by people who cannot read or write. It is synonymous with traditional and folk poetry’ (Lord, 1965, p. 591). Magoun tells us confidently that ‘oral poetry... is composed entirely of formulas, large and small, while lettered poetry is never formulaic’ (Magoun in Nicholson, 1971, p. 190).

If one concentrates on the ‘oral’ element in oral poetry, many confident assertions give the impression that ‘oral’ is a straightforward and easily identified characteristic of certain literature. ‘Oral literature’ is often equated with ‘oral tradition’, for instance, the ‘traditional’ element apparently being what makes it ‘oral’; this identification is implied in Lord’s comment just quoted and has been explicit in the work of most folklorists in the past. General and unequivocal statements are also made about the style of ‘oral poetry’. It is, for instance, ‘totally formulaic’ (Magoun, loc. cit.; cf. Lord, 1968a, p. 47), characterised by a special ‘oral technique’ and ‘oral method’ (Buchan, 1972, pp. 55, 58) and ‘of necessity paratactic’ (Lord, 1965, p. 592). It is often suggested that oral literature, not being written, is self-evidently the possession of non-literate peoples living in isolation from the centres of urban civilisation, or differentiated in some radical way from modern civilised society. Notopoulos claims among the ‘facts of life about oral poetry’ that ‘the society which gives birth to oral poetry is characterized by traditional fixed ways in all aspects of its life’ (Notopoulos, 1964, pp. 50, 51). The main conclusion appears to be that oral poetry is something clear and distinctive, with known characteristics and setting, and that to isolate it for study is in principle a simple matter.

The truth, however, is more complicated. When one looks in any detail at the manifold instances which have variously been termed oral poetry, it quickly becomes clear that the whole concept of ‘oral poetry’ is in fact a complex and variegated one. One can get round this, partially at least, by adopting a restrictive definition of ‘oral poetry’—which cuts out much that most people would include under the term and that is of greatest interest to students of the subject. If one takes a fairly wide approach, it has to be admitted that the term ‘oral poetry’ is both a complex and a relative one. It is true that if one is determined to set up a single uniform model of oral poetry, it is possible to discover certain regularities (especially when one does not have a very close acquaintance with a wide range of detail). Thus it might be possible to find something in common between, on the one hand, a short and pregnant Somali balwo lyric

Like a sailing ship pulled by a storm,

I set my compass towards a place empty of people2

or a witty Malay pantun—like the one describing an opium den

As red as a starling’s his peepers,

And he hails from the isle of Ceylon.

On their beds round a lamp lounge the sleepers

And pipes are the flutes that they play on

(Wilkinson and Winstedt, 1957, p. 10)

—and, on the other hand, a long and effusive Zulu panegyric ode memorised by its reciter and running to several hundred lines, or the famous epics of Homer, or the great Central Asian epic of Manas, in one version 250,000 lines long. But whatever can be found in common, the differences of style, symbolism, performance and social background are surely as striking as any real similarities. Too ready generalisation either risks setting up mere speculation in the place of evidence or is reducible to tautologies.

A basic argument running through this book is that many of the generalisations made about oral poetry are over-simplified, and thus misleading. Oral poetry can take many different forms, and occurs in many cultural situations; it does not manifest itself only in the one unitary model envisaged by some scholars.

This can be briefly illustrated by a quick initial look at a few of the various types of oral poetry known to occur throughout the world. This brings home something of the diversity of forms in which human beings have expressed their poetic imagination. At the same time it reminds us of the many parallels and overlaps with written literature. An initial survey of this kind necessarily begs the question of how ‘oral poetry’ should be defined and delineated—a question that must be faced later. But a preliminary survey of the field will give a general idea, in ostensive terms, of the kind of instances to be considered, and will at the same time illustrate my claim that what is commonly regarded as ‘oral poetry’ is by no means a clearly differentiated and unitary category.

In the brief discussion below, I have mainly adopted the terms long used in Western literary study to describe different genres. These terms form a convenient means of grouping together certain broad similarities. They can only take one so far, however; it cannot be assumed that they would be the most appropriate ones for detailed analysis of a given oral literature, or that their use in a preliminary account implies any attempt to set up a definitive typology of genres.

The first form that springs to mind—some would say the most developed form of oral poetry—is epic. In the general sense of a long narrative poem with an emphasis on the heroic, this genre has a wide distribution in time and space. The range runs from historic cases in the ancient world like the Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, the Greek Homeric poems of the Iliad and Odyssey, the Indian Mahabharata, or the mediaeval European epics like the Song of Roland, to more recent cases like the Finnish Kalevala or the long and impressive epics recorded in Russia and the Soviet Union in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the ‘Gesar’ epic so widely found throughout Tibet, Mongolia and China, the Yugoslav heroic poems recorded in the 1930s or the story about Anggun Nan Tungga recently recorded in West Sumatra, whose recitation takes up seven or more complete nights (Phillips, 1975).

Fig. 1.2. Modern depiction of Vyasa narrating the Mahābhārata to Ganesha at the Murudeshwara temple, Karnataka. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Karwar_Pictures_-_Yogesa_19.JPG

The term ‘epic’ is a relative one. ‘Pure’ epics like the Iliad or Odyssey are totally in verse, but it is also common for there to be some prose; this sometimes comes in the narrative portions, with soliloquies, conversations or purple passages in verse. In Kazakh epic, for instance, much of the basic narrative was often in prose, delivered in a kind of recitative, while the speeches of the main characters were in verse (Winner, 1958, p. 68). In the so-called ‘epic tales’ in the mediaeval Turkish Book of Dede Korkut (Sümer et al., 1972, pp. xxff) the verse is only about 35 per cent of the wordage, but plays a crucial part in the emotional and poetic impact of the whole. When the amount of prose is relatively slight, it seems fair not to exclude such poems totally from the general category of epic, but this is obviously a matter of degree. Extreme cases like the early Irish Tain Bo Cuailgne, the Congolese Mwindo and Lianja ‘epics’ or possibly the West African Sunjata narrative,3 with their apparently minimal use of verse, may not perhaps be regarded as satisfying the ‘verse’ criterion of true epic.

This list of examples gives only a few of the known cases. Epic has a very wide distribution over the world and throughout a period of several millennia. But it does not occur everywhere. Its absence in some cultures disappoints the expectation that ‘epic’ is a universal poetic stage in the development of society. In the usual sense of the term it seems to be uncommon in Africa and in general not to occur in Native America or, to any great extent, in Oceania and Australasia. All in all, epic poetry seems to be a feature of the Old World, where it is, or has been, held in high regard and composed or performed by specific individuals of recognised poetic expertise.

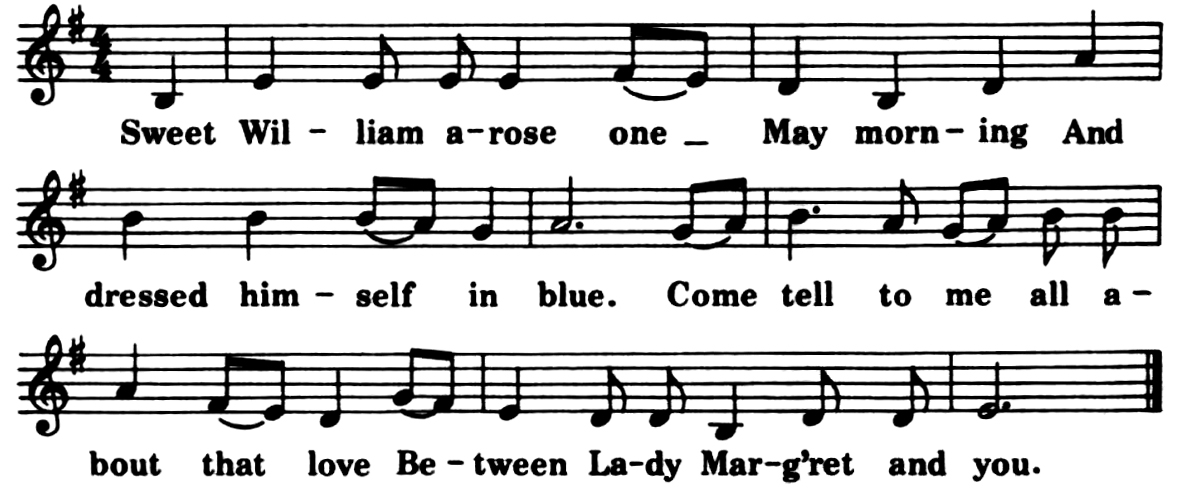

The ballad is another well-known form. It has been variously defined, but is generally agreed to be a sung narrative poem, shorter than the epic and with a concentration on a single episode rather than a series of heroic acts. In this sense, it is exemplified most clearly in English and Scottish ballads like Lord Randal, Barbara Allen or The Bonny Earl of Murray.

The incidence of the ballad is usually held to extend from mediaeval times (when the form arguably first appears) to the present, and to cover not just the European forms but the ballads apparently taken to the New World by immigrants over the last three centuries or so: the ballad Fair Margaret and Sweet William, for instance, is known both in Britain (it is No. 74 in Child’s classic collection) and, as in the version printed here, in the Southern Appalachian Mountains in the American South where it was one of the many ballads recorded by Cecil Sharp in his famous collecting expedition of 1916–18.

Fair Margaret and Sweet William

|

O I know nothing of Lady Marg’ret’s love And she knows nothing of me, But in the morning at half-past eight Lady Marg’ret my bride shall see. Lady Marg’ret was sitting in her bower room A-combing back her hair; When who should she spy but Sweet William and his bride As to church they did draw nigh. Then down she threw her ivory comb, In silk bound up her hair; And out of the room this fair lady ran. She was never any more seen there. The day passed away and the night coming on And the most of the men asleep, Sweet William espied Lady Marg’ret’s ghost A-standing at his bed-feet. The night passed away and the day coming on And the most of the men awake, Sweet William said: I am troubled in my head By the dream I dreamed last night. He rode up to Lady Marg’ret’s door And jingled at the ring; And none so ready as her seventh born brother To arise and let him in. |

O is she in her kitchen room, Or is she in her hall, Or is she in her bower room Among her merry maids all? She’s neither in her kitchen room, Nor neither in her hall, But she is in her cold, cold coffin With her pale face towards the wall. Pull down, pull down those winding-sheets A-made of satin so fine. Ten thousand times you have kissed my lips, And now, love, I’ll kiss thine. Three times he kissed her snowy white breast, Three times he kissed her chin; And when he kissed her cold clay lips His heart it broke within. Lady Marg’ret was buried in the old churchyard, Sweet William was buried close by; And out of her there sprung a red rose And out of him a briar. They grew so tall and they grew so high, They scarce could grow any higher; And there they tied a true lover’s knot, The red rose and the briar. |

(From Sharp, 1932, I, p. 132, as reproduced in Sharp and Karpeles, 1968, p. 38)

There is clearly a cultural unity involved here, between English, Scottish and American ballads; for though not all ballads are of the same kind, certain common plots, phrases, formulae, and repeated choruses recur. The interaction of orally performed with written and printed forms is also a well-known characteristic of these poems, due to the long-established custom of publishing them in printed broadsheet form as well as transmitting them orally.

Such ballads can thus be regarded as belonging to a common cultural matrix in time and space, albeit a fluid and developing one. It is this category of oral poems—an extensively recorded and studied one—that usually forms the primary reference when ‘the ballad’ is spoken of. But there are other forms sometimes called ‘ballad’ which do not belong to the same cultural complex. Further work is needed to determine the exact incidence and the possible usage of the term ‘ballad’; but in a broad definition (in the sense of a relatively short and non-heroic narrative song) the term could be applied also to such cases as Yugoslav ‘women’s’ poems (Chadwick, 1940, III, p. 690), Indian forms like the Gond ‘The goodwife had twelve ploughmen’, a ballad sung while weeding (Elwin and Hivale, 1944, pp. 269–75) or the mediaeval Chinese’ ballads described by Doleželová-Velingerová and Crump (1971). Though much depends on further research and on the terminology used, it seems again as if the most frequent occurrence of this genre is in the Old World rather than America, Oceania or Africa.

By contrast, panegyric odes are extremely common in both Africa and Oceania. In these the theme is praise of rulers and other notables, with consequent emphasis on apostrophaic ode and impressionistic evocation of the hero’s exploits rather than a chronological account of successive episodes. Perhaps one can see this form in these areas as balancing the interest in narrative verse in the Old World (though panegyric is not unknown there). Though an element of praise for patron or listener forms part of many different kinds of verse, its development as a specialist and highly valued genre is particularly marked in Africa and the Pacific. One could mention the Hawaiian eulogies of kings and princes, or the long Southern African praise poems, exemplified by these lines from the 300-line praise of Joel, a Sotho chief’s son:

Lightning of the village of Mohato, you who take all and leave nothing,

If you’re not the moon, you’re a star;

If you’re not the sun, you’re a comet.

The child of the chief is like an elephant in spring,

He’s like a stag that bends low as it runs,

When the cannons set the flames ablaze,

And the fires take slowly, catch light, and blaze ...

(Damane and Sanders, 1974, p. 190)

Similar is the Yoruba oriki praise of the famous local king, the Timi of Ede, which opens

Huge fellow whose body fills an anthill

You are heavily pregnant with war.

All your body except your teeth is black.

No one can prevent the monkey

From sitting on the branch of a tree.

No one can dispute the throne with you.

No one can try to fight you ...

(Beier, 1970, p. 40)

Lyric poetry, in the general sense of a (relatively) short non-narrative poem that is sung, is of extremely wide occurrence; it can probably be regarded as universal in human culture.

Though certain oral poems like epics and some panegyrics are chanted or declaimed only, sung delivery is the most common characteristic of oral poetry. Throughout this book (as in many discussions of oral literature) the term ‘song’ is often used interchangeably with ‘poem’ in the sense of a lyric, and the quickest way to suggest the scope of ‘oral poetry’ is to say that it largely coincides with that of the popular term ‘folk song’. Lyric is thus an extremely important and wide category of oral poetry.

Poems with many diverse functions occur in this sung form; love lyrics, psalms and hymns, songs to accompany dancing and drinking, political and topical verse, war songs, initiation songs, ‘spirituals’, laments, work songs, lullabies, and many others. A very few examples will suggest the wide range of ‘lyrics’ in oral poetry. They extend, for example, from mediaeval lyrics like the thirteenth-century attack on the Church’s worldliness by Philip the Chancellor of Notre Dame

Dic, Christi veritas,Dic, cara raritas,Dic, rara caritasUbi nunc habitas? |

Tell me, you truth of Christ,Tell me, dear rareness,Tell me, rare dearness,Where are you now? |

(quoted in Dronke, 1968, p. 56)

or the nineteenth-century Maori song of mourning by Te Heuheu Herea for his wife

Mourning Song for Rangiaho

Many women call on me to sleep with them

But I‘ll have none so worthless and so wanton

There is not one like Rangiaho, so soft to feel

Like a small, black eel.

I would hold her again -

Even the wood in which she lies;

But like the slender flax stem

She slides from the first to the second heaven

The mother of my children

Gone

Blown by the wind

Like the spume of a wave

Into the eye of the void.

(Mitcalfe, 1961, p. 20)

to a recent Gond dance song from Central India

She goes with her pot for water

But who can tell the sorrow of her heart?

(Elwin and Hivale, 1944, p. 259)

or, from Africa, a Shona drinking song

Keep it dark!

Don’t tell your wife,

For your wife is a log

That is smouldering surely!

Keep it dark!

(Tracey, 1933, no. 9)

or the hard-hitting African National Congress song in pre-independence Zambia

When talking about democracy

We must teach these Europeans

Because they do not know.

See here in Africa they bring their clothes

But leave democracy in Europe.

[Refrain] Go back, go back and

Bring true democracy.

We are no longer asleep

We are up and about democracy

We have known for a long time.

We are the majority and we demand

A majority in the Legislative Council...

(Rhodes, 1962, p. 20)

In the English language alone, the range of ‘lyric’ is immense in style, function and setting. It covers the songs in Shakespearian drama and other Elizabethan lyrics—surely an ‘oral’ form in most senses of the word—and also Black American spirituals, popular hymns and carols, favourite ‘folk’ and ‘traditional’ songs like The foggy dew or Loch Lomond, the ‘rebel’ as well as the ‘Orange’ songs of Ireland (compare, for instance, The wearing of the green with The sash me father wore), football supporters’ songs, sung nursery rhymes, the compositions of Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan and the Beatles, and even the lyrics—however ephemeral—propagated through radio, television and discs as the ‘Top Twenty’. The lyrics may not be approved by particular sections of musical and literary taste, but that they are all lyrics of a kind and at least arguably ‘oral’ is undeniable. Their very variety and their different appeal to different types of audiences bring home the huge range in style and content as well as in time and space of the short lyric form of oral verse.

No clear-cut classification of these various forms can readily be drawn up, nor can a simple account of their detailed distribution be given.4 But it can be said, first, that lyric forms occur constantly in descriptions of oral literatures all over the world (in this differing from epic and ballad forms); and second, that cultural groups vary in how far they make explicit distinctions between various categories of verse and how far they recognise some or all of these categories as specific genres.

Even a quick account like this shows the difficulty of arriving at simple generalisations applicable to all oral verse, or of trying to establish definitive genres on a comparative basis. Useful enough as a starting point, reliance on such genres may not be helpful in the more detailed study of local practice and terminology. Here one might have to take account of many things, some discussed in detail in later chapters: style and structure; treatment; occasion and function. One also has to accept that the whole idea of a ‘genre is relative, ambiguous, and dependent on culturally accepted canons of differentiation rather than universal criteria. Even the elementary account given so far—which would probably be fairly widely accepted as a preliminary categorisation—has drawn on a rather confused and inconsistent set of criteria—length, treatment, purpose, mode of delivery).

And many important forms have been left out in this quick survey: lengthy religious verse, like the elaborate mythological chants of traditional Polynesian religion (the Maori Six periods of creation, for instance, or Hawaiian Kumulipo) or chanted poetic sermons; dialogue verse, which can sometimes be assimilated to verse drama—ranging from Mongol ‘conversation’ songs (a dramatic verse form suitable for performance in traditional Mongol tents) to the fully developed form in modern Somali plays like the recently published Shabeelnaagood. Leopard among the women (Mumin, 1974); short verse forms—prayers, curses, street-cries and counting-out rhymes that are not sung; or the special oral poetry of African drums and horns.

Possibly enough has been said to make questionable some of the confident generalisations made about the whole category of oral poetry. Can we really continue to accept that ‘oral poetry’ is basically of one kind, or that it is practicable—as Milman Parry once hoped (Parry and Lord, 1954, p. 4)—to attempt to draw up ‘a series of generalities applicable to all oral poetries'?

It might seem unfair that I have taken such a wide sweep in my delineation of ‘oral poetry’. It might be argued that a more precise and limited definition of the term would make it possible to generalise about ‘oral poetry’. On this argument, my conclusions about the heterogeneous nature of oral poetry are the inbuilt result of my taking a loose (even sloppy) definition of the key term.

The whole problem of the definition of ‘oral’ must indeed now be considered. The problem itself, in my view, tends to support my emphasis on diversity. This forms the topic of the section immediately following. On arguments such as I present here (and in the book generally) you, the reader must in the end determine whether you prefer my relatively wide of the term ‘oral poetry’, or the narrower definitions proposed by other theorists. In the meantime it must be pointed out that all the forms mentioned in the brief account above have indeed been claimed at one time or another to be either ‘oral’, or correctly characterised by one of those other terms which people often lump together with ‘oral’ properties: ‘folk’, ‘traditional’, ‘tribal’ or (in the currently fashionable sense of ‘pop’ and ‘popular culture’) ‘popular’: most of these being precisely the terms used when a single category of oral-folk-traditional poetry is being assumed. Even if the forms were removed which some might feel uneasy about dubbing ‘oral’—modern pop songs, for instance, hymns, or lyrics which happen to be in Latin—the overall picture of diversity remains, together with a growing doubt whether the gulf between ‘oral’ and ‘written’ literature is as deep as sometimes assumed.

1.3 What is ‘oral’ in oral poetry?

Contrary to what is sometimes supposed the meaning of the term ‘oral’ is far from self-evident; it is a relative and often ambiguous term. Some discussion of the term is necessary at this stage, both to elucidate some of the problems, and to indicate the usage to be followed in this book.

In one sense ‘oral poetry’ is roughly delimited and differentiated from written poetry, and in a rough and ready way the term ‘oral’ is then clear enough. ‘Oral’ poetry essentially circulates by oral rather than written means; in contrast to written poetry, its distribution, composition and/or performance are by word of mouth and not through reliance on the written or printed word. In this sense it is a form of ‘oral literature’—the wider term which also includes oral prose. This wider term has sometimes been disputed on the ground that it is self-contradictory if the original etymology of ’literature’ (connected with literae, letters) is borne in mind. But the term is now so widely accepted and the instances clearly covered by the term so numerous, that it is an excess of pedantry to worry about the etymology of the word ‘literature’, any more that we worry about extending the term ‘politics’ from its original meaning of the affairs of the classical Greek polis to the business of the modern state. Over-concern with etymologies can only blind us to observation of the facts as they are. ‘Oral literature’ and ‘unwritten literature’ are terms useful and meaningful in describing some thing real, and have come to stay.

‘Oral poetry’—which does not raise the same etymological problems—is a particular type of oral literature, and so has a relatively clear initial scope. Most people with an interest in the subject will recognise it as covering instances such as the orally composed and performed Yugoslav epic poems being sung in the 1930s, the English and Scottish ballads that emigrants to America took with them and sang in their new homes, the lyrics composed by unlettered poets in Hawaii or New Zealand or the Gilbert Islands, modern schoolchildren’s verse or Australian Aboriginal song-cycles. In a general way, ‘oral poetry’, with its implied contrast with written literature, is a meaningful and useful term.

It is when one tries to analyse it and delimit it that difficulties arise. What are we to say, for instance, about some of the schoolchildren’s verse that has now been written down and published? Does the fact of its having been recorded in writing make it no longer oral? Or, if this seems far-fetched, what about the situation where a child hears a parent read out one of the printed verses (or even reads it himself) and then goes back to repeat it and propagate it in his school playground? And what then about popular hymns, whether English, Zulu or Kikuyu, which may begin their lives as written forms and appear in collected hymnodies, but nevertheless circulate largely by oral means through the performances of congregations made thoroughly familiar with them? Or forms like jazz poetry, or much mediaeval verse, written expressly for oral performance and delivery? Or a poem originally composed in oral performance, but later written down, learnt by others and used in later oral recitations? Cases like these are not marginal and aberrant; they are constantly cropping up and raise definitional problems which any student of oral poetry must recognise.

When one looks at cases of this kind, it seems that there are three main ways in which a poem may or may not be called oral and that these three do not necessarily coincide. It is important to separate them out, for analytic purposes, and to be clear which aspect is being stressed in any one account. It will emerge that different scholars have concentrated on different elements among these three, and that the resultant conclusions and apparent contradictions can sometimes be resolved by our greater clarity about which element is being emphasised.

The three ways in which a poem can most readily be called oral are in terms of (1) its composition, (2) its mode of transmission, and (3)—related to (2)—its performance. Some oral poetry is oral in all these respects, some in only one or two. It is important to be clear how oral poetry can vary in these ways, as well as about the problems involved in assessing each of these aspects of ‘oralness’. It emerges that the ‘oral’ nature of oral poetry is not easy to pin down precisely.

Take, first, the aspect of composition. (This is considered in greater detail in chapter 3, where some controversies in this field are discussed.) Basically, if one relies on this criterion, a poem is ‘oral’ if it is composed orally, without reliance on writing. Just what ‘composed orally’ implies is rather complex. One form of ‘oral composition’ is described by Parry and Lord in their analysis of the art of Yugoslav minstrels in the 1930s. Here the poet in a sense composes his heroic epics at the actual moment of performance, relying on a known fund of conventional’ oral formulae’ which he has built up from his own practice as well as from hearing other poets. Even if some of the sources for the basic plots and language include written material, this kind of oral composition-in-performance is the basic criterion, in the eyes of Lord and his followers, for considering the resultant poem ‘oral’. This criterion has been accepted by many scholars, including those who find in classical poems like the Homeric epics, Beowulf and the Song of Roland the formulaic style which can be taken as a mark of this kind of ‘oral composition’, and hence as an indication that these poems were, in some sense, originally ‘oral’, even if also later written down and circulating over many centuries in written form.

Fig. 1.3. Monument of Ostap Veresai, Sokyryntsi, Ukraine. Photo by Vladislav 501 (2011). Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:%D0%9F%D0%B0%D0%BC

%E2%80%99%D1%8F%D1%82%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA_%D0%B1%D0

%B0%D0%BD%D0%B4%D1%83%D1%80%D0%B8%D1%81%D1%82%D1

%83_%D0%92%D0%B5%D1%80%D0%B5%D1%81%D0%B0%D1%8E.jpg

This kind of composition-in-performance is not the only kind of oral composition. The process of composition can also be prior to, and largely separate from, the act of performance. This is the case, for instance, with many Inuit, Somali or Gilbertese lyrics, where the poet labours for hours or even days over the composition of the poem, which is only later presented in a public performance by the poet or others (see chapter 3, section 4). In this case the poet may have others helping him from time to time during the long period of composition, and may adapt the poem in minor ways during later performance. But it is clear that the actual process of composition is analytically separable from later performance and is, in these cases, too, ‘oral’. So, if composition is to be the criterion, the poems thus composed must also be ‘oral’.

Sometimes the process is more complicated, and involves oral composition both before and during performance, with subsequent modifications to later performances in the light of audience-reaction to specific portions—as with Dorrance Weir’s versions of ‘Take that night train to Selma’ (Glassie et al., 1970). In this case, or in Joe Scott’s ‘Plain golden band’, the resultant song may also be written down and begin to circulate in print and writing as well as orally. Similarly with many of the broadside and ‘street’ ballads hawked around by pedlars and minstrels in eighteenth-century England: some of these originated in orally-composed country songs and then started to circulate in print as well.

The exact delimitation of ‘oral composition’ thus turns out to be not very easy to fix, and often to involve overlap or interaction with written forms. Indeed it is sometimes hard to draw any very clear line of principle between the kind of mental composition sometimes engaged in by a literate poet, only later committing his words to writing, and that of the Inuit or the mediaeval Irish poet. Take the following description, for instance, of composition in the mediaeval Irish bardic schools. The pupils were required to work at their poems

‘each by himself on his own Bed, the whole next Day in the Dark, till at a certain Hour in the Night, Lights being brought in, they committed to writing’

(Clanricarde, 1722, quoted in Williams, 1971, p. 36)

Composition in this form is reminiscent of processes found in what would normally be called ‘written composition’.

‘Oral composition’ can therefore be a useful term that roughly conveys a general emphasis on composition without reliance on writing, but cannot provide any absolute criterion for definitively differentiating oral poetry as a single category clearly separable from written poetry.

Much the same applies to the criterion of transmission. At first sight, the characteristic of being transmitted by oral means seems a straightforward yardstick for differentiating oral from written literature. This criterion, which is usually the central one stressed by folklorists, is sometimes merely taken to imply that a given piece circulates or is actualised by oral means. This is clear and relevant enough, though if pressed it often turns out to be a relative rather than absolute property of’ oral literature’, for one needs to enquire about the degree to which something circulates by oral rather than written means. In this sense ‘oral transmission’ often overlaps or even coincides with ‘oral performance’.

Oral transmission is, however, often taken to imply the oral handing on of some piece over fairly long periods of time in a relatively unchanged form. Thus the Indian sacred book the Rgveda is said to have been orally transmitted over centuries or millennia, and it is this characteristic, besides its presumed oral composition, that leads scholars to classify it as ‘oral literature’. Again many of the English and Scottish ballads that ’travelled’ to America with successive waves of immigrants may have been originally composed and published in broadsheet (or printed) form; but because they were apparently preserved over the generations in certain rural areas of America through oral transmission, it has often seemed appropriate to classify them as ‘oral’ or (to use the more popular and roughly equivalent term among folklorists) as ‘folk’ poetry. Similarly the criterion of ‘oral transmission’ has been used as an implicit yardstick by anthropologists and others in deciding whether a given story or poem is worth documenting. A text apparently transmitted through a recently published book or modern school-teaching is assumed not to be properly ‘oral’ because it has not come to the area through long ‘oral transmission’. This can be so even when the piece is in some sense originally ‘orally’ composed or circulating through oral performance in the locality being studied. In the same way the ‘oral’ nature of certain written texts—Beowulf, for instance—is some times claimed to be indicated or partially indicated not so much because of oral composition or performance as because of its supposed long previous transmission by ‘oral tradition’, depending ‘for its material on oral rather than written sources’ (Wright, 1957, p. 21).

The application of this criterion is therefore perforce often merely speculative. Frequently there is little or no hard information about the earlier oral history of a given piece of literature. The evidence is even harder to pin down than might be expected because of the frequent probability of oral/written interaction and the fact that informants’ claims to be transmitting texts based on long word-for-word tradition have often turned out to be undependable. The criterion is thus not an easy one to use with confidence.

Its application is made all the more tricky by the romantic and evolutionist overtones of the concept of ‘oral transmission’: the idea of long tradition through ‘folklore’ and ‘folk memory’ from the dim primaeval mists of the infancy of the human race. These assumptions are now widely rejected by modern scholars but still tend to linger on as part of the mystique surrounding oral literature, affecting its practitioners as well as its analysts. This makes many claims about the long ‘oral transmission’ of some literary piece prima facie suspect or at any rate only to be accepted with caution.

So this aspect too of the ‘oralness’ of oral poetry turns out to be relative rather than absolute (‘oral transmission’ can, after all, be over a long or a short period), as well as being extremely elusive and difficult to pinpoint in practice.

The third possible criterion is actualisation in performance. Compared to the criterion of transmission, this is far less speculative and much more susceptible to discussion in terms of actual evidence. After all, it is some times possible actually to observe an oral performance taking place, and there is not the same reason as with claimed ‘oral transmission’ to distrust reported descriptions of such performances. In most cases, therefore, this is a relatively straightforward criterion.5

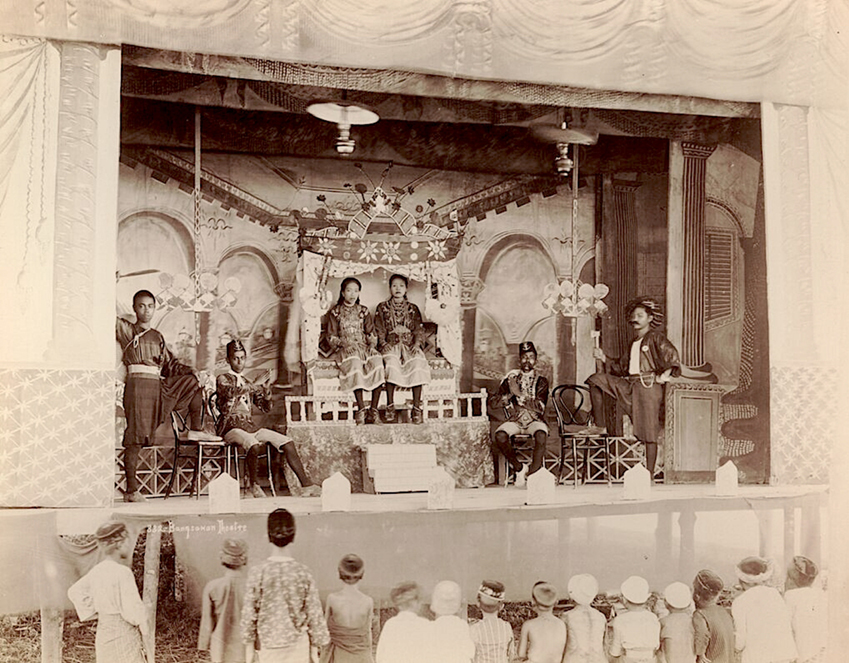

Even with oral performances, there can be problems. What is one to say, for instance, of the not unknown situation when one poet composes a piece for another to deliver—for instance the differentiation (at times anyway) between the mediaeval trobador (‘composer’) and joglar (‘performer’) in Europe, or the Irish filid (‘poets’) compared to the ‘bards’? When both categories—composers and performers—proceed orally, there is no problem. But what about the case when the composition is written, and only the delivery or performance oral? Each native operatic troupe in Malaya, for instance, ‘has its own versifier to write words to well-known tunes just as it has its own clown to invent new jokes for each performance’ (Wilkinson, 1924, p. 40). Written narratives apparently sometimes formed the basis of orally-performed mediaeval Chinese ballads (Doleželová-Velingerová and Crump, 1971, pp. 2, 8), and this pattern was common in classical Greece, where ‘the regular method of publication was by public recitation’ (Hadas, 1954, p. 50) as well as in the Middle Ages in Europe where, since ‘oral delivery of popular literature was the rule rather than the exception’, the works of popular writers were ‘intended for oral delivery’ and composed in a form suitable for performance (Crosby, 1936, pp. 110, 100). There are instances even within highly literate cultures, where plays or poems for live performances or broadcasting are written with the specific intention that they are to be performed. If oral performance is the central criterion, such cases must be classified as oral literature. One has to admit that in cases like these (which are not uncommon) there may be contradiction between the two criteria, composition and performance.

Fig. 1.4. Bangsawan, a Malay opera in Penang, Straits Settlements, circa 1895. Wikimedia, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Bangsawan#/media/File:KITLV_-_106227_-_Lambert_%26_Co.%2C_G.R._-_Singapore_-_Bangsawan%2C_Malay_opera_Penang_-_circa_1895.tif

There is also the problem, if we press the matter of performance, of deciding just what is the oral piece: surely the actual performance, and not the text from which it was delivered, which is all we usually have a full record of? And it becomes even more difficult when we include not just items specifically written for oral delivery, but any literary items which are in fact performed or performable. To include these may seem to make the coverage excessively wide, yet to exclude them means we may find ourselves making assumptions about the author’s intentions for a piece which it may be impossible to justify.

In addition, what is to count as ‘performance’? Some cases are clear enough, but there are marginal ones. The Swahili autobiography of Tippu Tip, for instance, is characterised by Wilfred Whiteley as belonging ‘partly to oral and partly to written prose ‘his audience seems not to have been a circle of kinsfolk or friends but rather a scribe’ (Whiteley, 1964a, p. 107). This situation is not necessarily uncommon, even for poetic pieces, and much has been written about the possibility of the Homeric and other epics being ‘orally dictated texts’ in this sense. Again, a performance need not involve an audience—witness the extreme but definite cases of oral literature being actualised by performers on their own, as, for example, by herdsmen among the Nilotes of the Sudan. But could one then call reading aloud a ‘performance’, or even the related process of hearing the sound of a poem in one’s head while reading it? Clearly, even with the relatively straightforward criterion of performance there are likely to be marginal cases and problems about application.

Where all three criteria of oral composition, oral transmission and oral performance unambiguously apply, there is no problem. A Maori poem known to have been composed and performed by an old man and transmitted by him to his children and grandchildren without any knowledge of writing, can be called ‘oral’ without any qualification. But in practice most cases are not like that. Very often the criteria conflict, and these cases are common enough not to count as the odd or untypical exception. In such circumstances no one criterion or set of criteria is self-evidently ‘right’, for the characteristic of ‘oralness’ has turned out to be relative and complex. A number of possible characteristics are involved, and need not necessarily coincide. They certainly do not, jointly or severally, produce a precise and unambiguous category of ‘oral poetry’ clearly distinct from written forms.

Because of this relative and often ambiguous nature of ‘oralness’ I need make no apology for not producing a clear and precise definition of ‘oral’ poetry. For the relativity and ambiguity are part of the nature of the facts, and to try to conceal this by a brisk definition would only be misleading. It is only fair, however, to make clear that I take a fairly wide approach to the concept of oral poetry. I consider it unrealistic and unhelpful to confine oneself to more restrictive definitions like that of Lord, who would limit the term to poetry produced by one particular type (only) of oral composition. I have also laid more stress on the aspect of oral performance than do some analysts, considering that if a piece is orally performed—still more if it is mainly known to people through actualisation in performance—it must be regarded as in that sense an ’oral poem’. I have thus included in the discussion references to certain poetry (well-known hymns, for instance) which some students might exclude. I have in addition tried to make clear, when it is relevant, which aspect of ‘oralness’ I am stressing at any given point.

But, when all is said and done, the concept of ‘oralness’ must be relative, and ‘oral poetry’ is constantly overlapping into ‘written poetry’. Therefore anyone interested in studying the facts about oral poetry rather than playing with verbal definitions or theoretical constructs has to recognise that consideration of ‘oral poetry’ cannot start from a precise and definitive delimitation of its subject matter from written literature. To repeat the theme that will recur throughout this book: ‘oral poetry’ is inevitably a relative and complex term rather than an absolute and clearly demarcated category.

The relative and ill-defined nature of oral poetry is hardly surprising when one reflects on the mixture of communication media that has long been a feature of human culture. We are accustomed to taking account of many different media in the world today: verbal and face-to-face communication in small groups, writing, print, radio, television, records or tape, to mention just some; and we have to recognise that poetry or song produced today may involve a mixture of several or all of these. It is easily understandable that it may not be confined to just ‘written’ or just ‘oral’ media but involve a mixture of both. But it is sometimes forgotten that this mixture is not a distinguishing feature of the modern industrial west. People in ‘developing nations’ too make use of the media of print, radio and television, and a number of instances of ‘oral poetry’ published recently from Africa or the Middle East were originally broadcast and listened to on transistor radios through even the remote areas of the country.

It is even more important to remember—since it seems to be more easily forgotten—that it is not just in the last generation or two that writing has gained significance as a medium for communication in the so-called ‘Third World’. A degree of literacy has been a feature of human culture in most parts of the world for millennia.6 This has rarely meant mass literacy (a fact significant for the popular circulation of oral literature) but has meant a measure of influence from the written word and literatures even in cultures often dubbed ‘oral’. Illiterate populations in Malaysia have through the literate few had contact with the written literatures of Hinduism and Islam, and the influence of the high cultures of India and China has long pervaded huge areas of Asia, just as Latin learning and the sacred writings of Christendom have had a long effect in Europe as well as in the areas to which Christian missionaries carried their learning over several centuries. Literature in written form was not accessible to large masses of the population, but to regard the (till recently) largely illiterate peoples of Africa or the Middle East as having no contact with written literature till the twentieth century and existing in some ideal world of purely ‘oral’ and localised culture is seriously misleading.

Since literate and non-literate media have so long co-existed and interacted it is natural to find not only interaction between ‘oral’ and ‘written’ literature but many cases which involve overlap and mixture. Today a large proportion of the world’s population can read and write but the adult illiteracy rate in the world as a whole is still probably around one third. It is not surprising that poetry is propagated sometimes by oral, sometimes by written means, with no great and insurmountable gulf between the two. Similarly in the past, when fewer were literate, we should expect ‘oral poems’ to be influenced by, and interact with, written forms, and indeed sometimes coincide with them.

This point is worth stressing. For though, put this way, it seems obvious, it runs counter to some presuppositions commonly held about oral literature and its incidence. In particular it raises questions about one very commonly held assumption about the incidence and nature of oral literature and oral poetry. This is that its most common context is the kind of ‘primitive’ communal and artless society depicted in the older stereotypes of many sociologists and folklorists. The ‘traditional’ rural and non-literate7 type of culture, it is presupposed, is the’ natural’ setting for oral literature and we should take it as the reference point for ‘real’ oral literature. This fits with various myths about the noble savage or the value of the deep and unconscious springs of our being. This set of ideas has a long history in the western world and naturally it has affected our appreciation of the nature of oral literature and its probable setting. The implicit assumption that oral poetry most commonly and naturally belongs to the kind of ‘primitive’ society envisaged in these stereotypes goes very deep, accompanied by the idea that any other setting for oral poetry must be unusual, or perhaps ‘transitional’ between the two settled states of ‘primitive’ and non-literate on the one hand, and industrial and fully literate on the other. Because these presuppositions go so deep, it is necessary to stress the point already made: that ‘oral poetry’ is not a single and simple thing. It can occur in many different kinds of setting. Oral poetry can occur in a society with partial literacy or even mass literacy, as well as in supposed ‘primitive’ cultures. One only needs to think of the celebrated Yugoslav oral epics, with their constant interaction over generations with printed versions; English and American ballads, which have been sung in very different geographical areas, cultures and periods; modern ‘pop’ songs; or the productions of Canadian lumberers or American ‘folksingers’ like Larry Gorman, Almeda Riddle or Woody Guthrie. The ‘typical’ oral poet is as likely to have some knowledge of writing as to live in the remote and purely ‘oral’ atmosphere envisaged in the stereotype. If one considers actually recorded and studied cases of oral poetry, its authors are really more likely than not to have had some contact with literacy.

The basic point then, is the continuity of ’oral’ and ‘written’ literature. There is no deep gulf between the two: they shade into each other both in the present and over many centuries of historical development, and there are innumerable cases of poetry which has both ‘oral’ and ‘written’ elements. The idea of pure and uncontaminated ‘oral culture’ as the primary reference point for the discussion of oral poetry is a myth.

1.4 The ‘poetry’ in oral poetry

I cannot here enter into deep discussion of the question ‘what is poetry?’ Apart from a couple of relatively minor points (considered below), deciding what is poetry is no more easy or difficult for oral than for written literature. Nor will I discuss what, in universal terms, is to count as ‘good’ poetry—the connotation sometimes attached to the English term ‘poetry’. For the purposes of comparative study, what must be culture-bound judgement will as far as possible be avoided (it is perhaps not possible entirely), and the term ‘poetry’ used in the wide sense to cover all kinds of poetry: ‘bad’ and ‘good’. No protracted or profound treatment, therefore, of the deeper literary or aesthetic issues need be expected here.

Some brief discussion, however, of the particular problems of delimiting poetry in oral literature is essential. These are not basic to the general aesthetic theory of the essence of poetry, but at a straightforward level can provide practical difficulties for the fieldworker and analyst.

The first and most important point is that in written literature poetry is normally typographically defined. There are other factors in play too, but—trivial though this may sound—it has to be accepted that in our culture, the handiest rule of thumb for deciding on whether something is poetry or prose is to look at how it is written out: whether ‘as verse’ or not. On the surface, this rule of thumb makes it easy for even a schoolchild to differentiate quickly between ‘prose’ and ‘poetry’.

Obviously this particular rule will not, by definition, work for unwritten poetry. One is thus forced to look for other, apparently more ‘intrinsic’ characteristics by which something can be delineated as ’poetry’ within oral literature.

The first property that springs to mind is ‘rhythm’ or ‘metre’, and this indeed is often a useful test. But much the same difficulty applies here in oral as in written poetry: the concept and manifestation of ‘rhythm’ is a relative thing, and depends partly on culturally defined perceptions; it cannot be an absolute or universally applicable criterion. Where does one draw the line, for instance, among the various ‘speech modes’, some more ‘poetic’ than others, in which the Mandinka Sunjata ‘epic’ is delivered in West Africa? Or once something is categorised as ‘rhythmic prose’—some curses for instance—must we suspect a contradiction in terms and change the categorisation to ’verse’? In addition, there are some oral literary pieces which a number of observers have regarded as ‘poems’ in which metre or regular rhythm in the normal sense seem to be missing—and yet there seem to be other prosodic and stylistic features which replace them (see chapter 4, section 2). What we must look for is not one absolute criterion but a range of stylistic and formal attributes—features like heightened language, metaphorical expression, musical form or accompaniment, structural repetitiveness (like the recurrence of stanzas, lines or refrains), prosodic features like metre, alliteration, even perhaps parallelism. So the concept of ’poetry’ turns out to be a relative one, depending on a combination of stylistic elements no one of which need necessarily and invariably be present.

A further aspect is the way in which a poem is, as it were, italicised, set apart from everyday life and language. This is so of any piece we would term ‘literature’8—but especially so of a poem. In the written form we set it apart typographically, but also by its setting or the way it is performed or read aloud: whatever its rhythmic properties may be, a poem is likely (even in a literate culture) to be delivered in a manner and mood which sets it apart from everyday speech and prose utterance.

This ‘setting apart’ through performance and context is clearly also applicable to unwritten poetry. Such factors are difficult to pin down exactly, but the ways in which a literary piece may be‘ framed‘ or‘ italicised‘, and so may be more suitably termed a ‘poem‘, may include the context and setting of the performance, the mode of delivery, the audience‘s action, the musical attributes—not for nothing do we speak of a musical ‘setting’—as well as the stylistic features already mentioned (particularly the recurrence of refrains), and in general the atmosphere of ‘play’ rather than ‘reality’, an activity set apart from ‘real life’. Factors like these are inevitably both relative and elusive; partly empirically observable, they also depend on the assessment of observer and actors. But something of this sort—an assessment that a given piece is picked out and ‘framed‘—often enters into the classification of a particular verbal phenomenon as an instance of ‘poetry‘. In accepting these instances as ‘poems‘ we should be aware of the factors likely to lie behind such assessments by ourselves or others.

Finally, there is the local classification of a piece as ‘poetry‘. In one sense this is the most important, but it is by no means simple. For one thing, the relatively neat formal differentiation we make in our culture between poetry and prose is not recognised everywhere. In Malay literature—to mention one instance—the distinction between prose and poetry is blurred. Wilkinson points out that ‘prose’ as well as ‘poetry’ is often chanted or sung, and ‘much Malay prose-literature is in a transition stage; it contains jingling, half-rhyming and even metrical passages; it is written for a singer and not for a reciter or reader‘ (Wilkinson, 1924, p. 44). In some languages there is no single word that exactly covers our ‘poetry‘, even though special terms may differentiate literary genres, some or all of which we may, following our other criteria, term types of ‘poetry‘. In Yoruba, for instance, there are special terms for ‘praise poetry‘, ‘hunters’ poems’, ‘festival poetry’, and so on, but no one word corresponding to‘ poetry‘ in general, and the same is true of Gaelic verse. Furthermore, local classifications do not necessarily coincide with the line we draw between ’prose‘ and ‘verse‘, but emphasise some other factor, like mode of delivery or social function and setting, so that what at first sight may look like the category equivalent to our ‘poetry‘ may turn out to include and exclude unexpected cases. Indeed, even the English case turns out to be more complicated than it first appears. For the normally accepted coverage of ‘poetry‘ tends to exclude certain linguistic forms which, if we take account of the factors mentioned earlier, might have been expected to count. Thus the words of Elizabethan lyrics are normally included in the category of ‘poetry’, but many liturgical forms or the words of more recent lyrics are excluded.

Instances of this sort remind us that while we need to take account of local classifications—and in any analysis of a particular poetic culture this would be an essential preliminary—these, too, may not give a clear-cut and simple guide in any comparative study of poetry, whether oral or written. For this one needs to use general comparative terms like ‘poetry’, ‘literature’ which inevitably misrepresent some local distinctions. This difficulty is not unique to the study of poetry, for it arises in any kind of comparative study, even within a single culture, but it adds to the difficulty of producing any very exact delimitation of ‘poetry’.

It emerges, then, that any differentiation of ‘poetry’ from ‘prose’ or, indeed of ‘poetry’ as a specific literary product or activity, can only be approximate. The distinction between ‘poetry’ and ‘prose’ is relative, and the whole delimitation of what is to count as ‘poetry’ necessarily depends not on one strictly verbal definition but on a series of factors to do with style, form, setting and local classification, not all of which are likely to coincide.

This conclusion about the relativity of ‘poetry’ is not unreasonable in principle. More important, it takes account of the complex realities of the practice of ‘oral poetry’ throughout the world, and helps to explain why there is continuing controversy about, for instance, whether Pueblo (Zuni) narratives are ‘prose’ or ‘poetry’ (Tedlock, 1972), or how far the ‘speech modes’ in the West African ‘epic’ of Sunjata can be interpreted as types of poetry (Innes, 1974). It also recognises the practical difficulties of collectors and analysts of oral literature, and provides a background to frequent comments such as this:

The distinction between prose and verse is a small one... the border line between them is extremely difficult to ascertain and define, while the verse-technique, in so far as verse can be separated from prose, is extremely free and unmechanical. Broadly speaking, it may be said that the difference between prose and verse in Bantu literature is one of spirit rather than of form, and that such formal distinction as there is one of degree of use rather than of quality of formal elements. Prose tends to be less emotionally charged, less moving in content and full-throated in expression than verse; and also—but only in the second place—less formal in structure, less rhythmical in movement, less metrically balanced.

(Lestrade, 1937, p. 306, on Southern Bantu literature)

This complexity and relativity of ‘poetry’ will emerge further in later chapters. For the moment it is worth making two points.

First, it is interesting how far one is forced to take account of social and not just textual criteria in assessing whether something is to count as a ‘poem’ or not—social conventions about appropriate style, form or setting, socially recognised classifications at the local level. This supports another recurrent theme of this book: that poetry is not just something ‘natural’ and ‘universal’ that can be abstracted from its social setting: its very delimitation depends to a large extent on the varying social conventions that surround its performance and recognition. Its manifestation as a social phenomenon makes it a subject for both the literary scholar and the sociologist.

Second, it is worth remembering that this discussion was prompted initially by the problem of delimiting ‘poetry’ in oral literature. But it is worth asking how far some of the points made here might be applicable to the study of written poetry as well. Here too—if one wants to go beyond the ‘typographical’ yardstick, itself a circular one—it is a question of taking account of the same general range of factors relating to style, performance, setting, and local or contemporary classification.

1.5 Performance and text

Discussion of the incidence of genres, and the continuity of oral and written poetry, takes as its reference-point the text of oral poems: the idea that there is something that can be called ‘the poem’, such that one can discuss its oral or other characteristics, or how widely it and similar instances can be found throughout the world. This indeed is how the subject has commonly been approached. But the text is, of course, only one element of the essence of oral literature—a fact which emerged in the previous discussion. Oral poetry does indeed, like written literature, possess a verbal text. But in one respect it is different: a piece of oral literature, to reach its full actualisation, must be performed. The text alone cannot constitute the oral poem.

This performance aspect of oral poetry is sometimes forgotten, even though it lies at the heart of the whole concept of oral literature. It is easy to concentrate on an analysis of the verbal elements—on style and content, imagery, or perhaps transmission. All this has its importance for oral literature, of course. But one also needs to remember the circumstances of the performance of a piece—this is not a secondary or peripheral matter, but integral to the identity of the poem as actually realised. Differently performed, or performed at a different time or to a different audience or by a different singer, it is a different poem.

In this sense, an oral poem is an essentially ephemeral work of art, and has no existence or continuity apart from its performance. The skill and personality of the performer, the nature and reaction of the audience, the context, the purpose—these are essential aspects of the artistry and meaning of an oral poem. Even when there is little or no change of actual wording in a given poem between performances, the context still adds its own weight and meaning to the delivery, so that the whole occasion is unique. And in many cases, as will be seen in later chapters, there is considerable variation between performances, so that the literate model of a fixed correct version—the text of a given poem—does not necessarily apply.

In this respect, oral literature differs from our implicit model of written literature: the mode of communication to a silent reader, through the eye alone, from a definitive written text. Oral literature is more flexible and more dependent on its social context. For this reason, no discussion of oral poetry can afford to concentrate on the text alone, but must take account of the nature of the audience, the context of performance, the personality of the poet-performer, and the details of the performance itself.

It is only recently that much interest has been taken in these aspects, which are harder to record and analyse than the verbal texts. But there is now a growing awareness that any piece of oral poetry must, to be fully understood, be seen in its context; that it is not a separable thing but a ‘communicative event’ (Ben-Amos, 1972, p. 10).

If oral poetry is ‘different’, there is also a basic continuity. Even if the text is not the whole of an oral poem, it is one part—which it shares with written literature. It would be exaggerated to pursue the ‘communication’ approach to oral literature so far that the text, still a fundamental, was ignored. Even without knowledge of the social background or style of performance we can still find meaning in these lines by a Gilbertese poet:

Even in a little thing