2. Some approaches to the study of oral poetry

©2025 Ruth Finnegan, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0428.02

The study of oral poetry can be an emotive subject, often shot through with deeply-held assumptions and value-judgements. Some grasp of the repercussions of these assumptions, theories or models is essential. Many assumptions are so much part of the unspoken premises of some writers that one constantly meets them stated as firm truth. If dogmatic speculations appear as incontrovertible facts, even in the writings of respected scholars, it is necessary to be able to set statements about oral poetry against this background of different approaches and assumptions. Otherwise it is difficult to disentangle which claims are controversial, which are attempts to build on modern empirical research, and which are plain wrong in the light of recent findings. It is often associations and connotations rather than the explicit positions which are hardest to pin down without some knowledge of the theoretical approach being taken for granted. Yet many of them have been influential in the interpretation of oral literature. It is all the more important to see what they are.

The main approaches considered in this chapter are (1) romantic and evolutionist theories (2) the Finnish historical-geographical approach (3) controversies in the sociology of literature and (4) the general sociological concept of a relationship between type of society and mode of communication (literary and other). The brief presentation of these here provides a background to discussions in later chapters of topics like oral composition, transmission, the position of poets, or the relation of poetry and society.

2.1 Romantic and evolutionist theories

The first group of theories has had a profound influence on the study of oral literature. They have radically affected not only scholarly analysis (particularly by evolutionist anthropologists and many folklorists) but also popular assumptions about the subject. These theories in part depend on an evolutionist approach—the idea that societies progress up through set stages with ‘survivals’ from earlier strata sometimes continuing in later ones. To understand the import of this, one must also bear in mind certain developments in western intellectual history.

The set of assumptions involved is closely related to certain strands in the romantic tradition in European thought in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (and in some respects up to the present); and in particular its expression in the romantic nationalism of the nineteenth century. ‘Romanticism’ is a wide term with a plethora of variegated meanings. I cannot embark on a detailed account here. But it is possible to point to an identifiable tradition of central significance for the study of oral poetry. This is the emphasis on the spontaneous expressive quality of art and the artist, beginning around the middle of the eighteenth century and fostered by the rise of ‘nationalism’ in the nineteenth. This intellectual tradition has had a deep influence on enduring assumptions about the nature of ‘oral literature’ specifically (often under the name of ‘folklore’) and about the nature of society/ies more generally).

Fig. 2.1. AI-generated image of a man standing in front of a tree in a book. Poetry, in the Romantic Wordsworthian view, is the product of nature and of the poet as the lone, remote, individual, outside society. AdobeStock, https://stock.adobe.com/uk/images/a-man-standing-in-front-of-a-tree-in-a-book/873325803

A central strand in romanticism is the stress on the expressive, emotional side of art and the genius of the artist himself. This is unlike previous approaches to the analysis of art which tended to stress its relation with audience and patron. The poet is now seen as the vehicle for spontaneous emotion which bubbles up through him in the form of a poem. The description of poetry in terms of passion, emotion, ‘inspiration’, ‘uttering forth’ and expressiveness, is common among nineteenth-century Romantic writers, and typified by Wordsworth’s famous description of poetry as ‘the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings’ (Preface to lyrical ballads, in Smith, 1905, p. 15).

Allied to this is the common idea of poetry as natural and instinctive. ‘Nature’ is opposed to ‘art’, so that the truest poetry is essentially spontaneous, artless and natural. As M. H. Abrams sums it up, this is closely connected with ‘the general romantic use of spontaneity, sincerity, and integral unity of thought and feeling as the essential criteria of poetry, in place of their neo-classic counterparts: judgment, truth, and the appropriateness with which diction is matched to the speaker, the subject matter, and the literary kind’ (Abrams, 1958, p. 102).

This approach has parallels in more wide-ranging theories about the nature of man and society. Rousseau, often regarded as one of the precursors of Romanticism, presents man as of natural and spontaneous goodness, untrammelled by the constraining non-natural bonds of society—‘Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains’—and in his educational writings he advocates a kind of ‘return to nature’. The interest in literary expressiveness adds a further dimension to general enthusiasm among many eighteenth-century writers for a return to the state of nature and the abolition of ‘society’. ‘Nature’ as opposed to ‘art’ has its parallels in the idea of ‘nature’ (or the natural individual) as opposed to ‘society’. As Lovejoy put it, ‘nature’ was supposed to consist in ‘those expressions of human nature which are most spontaneous, unpremeditated, untouched by reflection or design, and free from the bondage of social convention (Lovejoy, 1948, p. 238). In the romantic interpretations these attitudes to untrammelled, untamed ‘nature’ were applied to the theory of poetry so that in aesthetic terms too, the ‘natural’ or ‘simple’ came to be prized above ‘art’:

What are the lays of artful Addison,

Coldly correct, to Shakespeare’s warblings wild?1

In the Romantic view, the quintessence of emotional expression and natural spontaneity is found in ‘primitive’ language and culture. Poetry originates in primaeval expressions of emotion which are by nature expressed in rhythmic and figurative form. Further, ‘unlettered’ folk as well as far-off ‘primitive’ peoples are thought to represent the essence of the natural and instinctive poetic expression so valued by romantic writers. When Wordsworth wants to illustrate the ‘primary laws of our nature’ through poetry he chooses

humble and rustic life … because, in that condition, the essential passions of the heart … are less under restraint, and speak a plainer and more emphatic language; because in that condition of life our elementary feelings co-exist in a state of greater simplicity … because the manners of rural life germinate from those elementary feelings … and, lastly, because in that condition the passions of men are incorporated with the beautiful and permanent forms of nature.

(Wordsworth in Smith, 1905, p. 14)

Similarly, much eighteenth-century theorising about the origins of language and poetry stressed their fundamentally instinctive and natural qualities. Art first developed in ‘savage Life, where untaught Nature rules’, as John Brown summed it up in his Dissertation on the Rise...of Poetry and Music in 1763 (p. 27). The same sort of view is repeated by Gummere over a century later. Poetry was first found in ‘that aboriginal wildness, that ecstasy of the horde, first utterance of unaccommodated man … from this dancing throng came emotion and rhythm, the raw material of poetry’ (Gummere, 1897, reprinted in Leach and Coffin, 1961, p. 29), and ‘if we could catch a glimpse of primitive conditions, we should find poetry entirely ruled by the mechanical, the spontaneous, the unreflecting element’ (ibid., p. 28). His general view, expressed in typically romantic terms, was that the first origins of poetry in primitive cultures were ‘communal’ and characterised by ‘the lack of individuality, the homogenous mental state of any primitive throng, the absence of deliberation and thought, the immediate relation of emotion to expression, the accompanying leap or step of the dance under conditions of communal exhilaration’ (ibid., p. 27).

The concept of Nature as the prime force in ‘primitive’, ‘unlettered’ poetry was sometimes taken so far as to imply an organic and even ‘vegetable’ theory of poetic genesis. True literature—above all ‘primitive literature’—grew up of itself without conscious deliberation or individual volition, an idea given further force by the German romantic philosophers. Schlegel, for instance, opposes mechanical form—external and accidental—to innate ‘organic form’ which ‘unfolds itself from within, and reaches its determination simultaneously with the fullest development of the seed … In the fine arts, just as in the province of nature—the supreme artist—all genuine forms are “organic”’ (A. W. Schlegel, Viennese lectures on dramatic art and literature, published 1809–11, quoted in Abrams, 1958, p. 213). This botanical imagery, with its overtones of non-conscious automatic growth, is frequently applied to unwritten literature, from Baissac’s description of a Mauritian story as ‘cette fleur spontanée du génie de l’enfance’ (Baissac, 1888, p. vii), or Fletcher’s description of American Indian songs as ‘near to nature … untrammelled by the intellectual control of schools … like the wild flowers that have not yet come under the transforming hand of the gardener’ (Fletcher, 1900, p. ix) to John Lomax’s suggestion that cowboy songs ‘have sprung up as has the grass on the plains’ (quoted in Wilgus, 1959, p. 80), or Bronson’s more recent characterisation of folk song: ‘as natural as wildflowers’ (Bronson, 1969, p. 202).

This attitude to the ‘natural’ products of ‘primitive’ and ‘unlettered’ people, and to the ‘folk’, the ‘peasants’, and ‘the common people’ generally, often involved a sentimental and glamorising admiration. This received further encouragement from another frequent characteristic of Romanticism: a dissatisfaction with the current state of the world and a deep yearning for something other—‘for the remote, the unusual, the unattainable … it loves the past because it can no longer partake of the past; it loves the future because it can never arrive at the future’ (Anderson and Warnock, 1967, pp. 269–70).

Correspondingly, speculation about the primitive origins of poetry and language in ‘nature’, and the view of poetry as originally and ideally an instinctive, artless outburst of feeling, involves not just a theory about origins but a romanticising glorification of the ‘natural’, the ‘primitive’, and the ‘emotional’, and a reaching out to a supposed lost world in the past when man and his emotional expressions were free, integrated and natural.

This romantic approach did more than affect the analysis of oral literature as part of the general climate of opinion within which it was first closely studied. It also had an intimate connection with the rise of what was then called ‘folklore’ study (which normally at least included what is now termed ‘oral literature’ and was sometimes identified primarily with it). For one element in Romanticism has had direct influence on the development of studies of oral literature: the emergence of the romantic nationalism of the nineteenth and (to some extent) twentieth centuries.

The outburst of nationalism in Europe following the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars has often been remarked as one of the strands in Romanticism. Along with this went an emphasis on local origins and languages, accompanied by an enthusiasm for the collection of ‘folklore’ in various senses—what would now be called ‘oral literature’ (ballads, folk songs, stories) as well as ‘traditional’ dances and vernacular languages and ‘customs’. The political and ideological implications of this return to ‘origins’ are obvious, and the appeal was all the more forceful because of the Romantic stress on the significance of the ‘other’ and the ‘lost’, and the virtue of ‘unlettered’ and ‘natural’ folk both now and in the past.

The connection between the interest in folklore and the tenets of Romanticism may not be altogether clear. Indeed there are contradictions—not surprisingly—within the complex group of attitudes known as Romanticism. But the key strands in the approach to national and ‘folk’ literature are, first, the view of the artless spontaneity of such literature, and, second, the yearning for another, more organic and natural world from the analyst’s own. Hence that concept of literature among our ancestors, among contemporary ‘primitive’ peoples, and among unlettered and peasant ‘folk’ generally as arising spontaneously and without conscious volition on the part of those involved: a ‘natural growth’. It springs up of itself from deep, mysterious roots which can be traced far back in the history and inner depths of mankind. This sort of ‘folklore’—national epics, ballads, folk songs, local stories—seemed to mark a continuity with the longed-for lost, other world or organic and emotional unity, so that here contact could be made with the natural and primaeval depths, as distinct from the externally-imposed, mechanical and rationalist forms of the contemporary world.

In this complex of attitudes the idea of tradition plays a central role. For if such folk ways develop of their own accord and, as it were, naturally, without deliberate art, their continued existence and ‘tradit-ing’ through the generations without conscious acts of choice or even understanding by the traditors seems to follow. Thus one has the paradox—often noted—that the movement which laid such stress on the individual artist and his freedom should also be led to such deep belief in, and romantic respect for, ‘tradition’ and ‘the collective’. For all the apparent contradiction, the feeling that through folk popular art one could reach back to the lost period of natural spontaneous literary utterance as well as to the deep and natural springs of national identity was basic to the romantic attitude, and received extra force through ideological and nationalist references to ‘tradition’. It became accepted that there was a clear and valid distinction between learned, consciously composed literature and the kind of poems which—like the sources of the Finnish Kalevala—‘belong to a period of spontaneous epic production … popular or national … Poetry which gave rise to them is natural, spontaneous, collective, impersonal, popular: hence national in its origins and its developments’ (Comparetti, 1898, p. v). In the romantic approach the concept of tradition through the generations in relatively unchanging form plays a vital part.

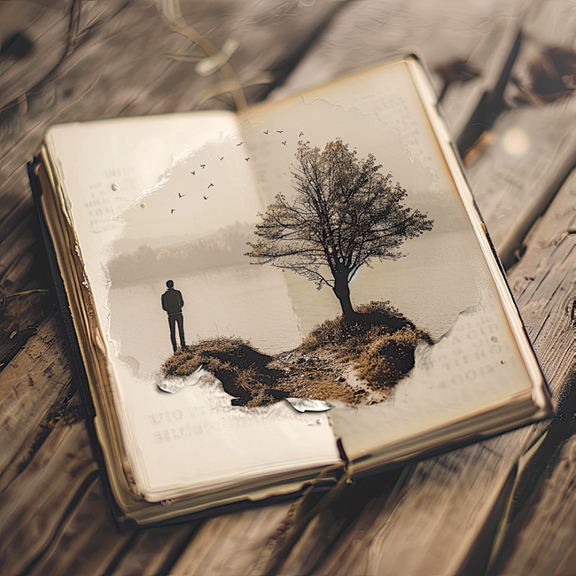

This is the background against which ‘folklore’ as a specialist study first began, around the middle of the nineteenth century. Clearly, there had been interest in the materials of folklore before that—for example, the publication of Grimm’s Household Tales, Keightley’s The Fairy Mythology or Scott’s Ministrelsy of the Scottish Border earlier in the century—but the emergence of ‘folklore’ as a named discipline is usually dated precisely to 1846, when William Thoms wrote a letter to The Athenaeum proposing a new name for what had hitherto been called ‘Popular Antiquities’ or ‘Popular Literature’:

Your pages have so often given evidence of the interest which you take in what we in England designate as Popular Antiquities, or Popular Literature (though by-the-bye it is more a Lore than a Literature, and would be most aptly described by a good Saxon compound, Folklore,—the Lore of the People)—that I am not without hopes of enlisting your aid in garnering the few ears which are remaining, scattered over that field from which our forefathers might have gathered a goodly crop.

(Thoms, 1846, p. 862)

Fig. 2.2. The cover of the 1846 issue of The Athenaeum journal, in which William Thoms famously coined the term ‘folklore’. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Athenaeum_1846_issue.jpg

He goes on to give examples of what he intends, suggesting that readers should note or send to The Athenaeum ‘some record of old Time—some recollection of a now neglected custom—some fading legend, local tradition, or fragmentary ballad!’.

Thoms’s suggestions were taken up with enthusiasm, and ‘folklore’ study and collection attracted wide interest throughout the century and later, fostered by romantic and nationalist attitudes to ‘traditional lore’, and the nostalgic belief that it was dying out and must be recorded before it was lost forever. ‘Fast-perishing relics’ was a common phrase and the accepted initial definition of ‘folklore’ was ‘study of survivals’. G. L. Gomme, for example, an important figure in the development of the subject, describes ‘the science of folk-lore’ as ‘the science which treats of the survivals of archaic beliefs and customs in modern ages’ (Gomme, 1885, p. 14) and similar remarks stressing the age, lengthy survival and ‘traditional’ nature of the objects of folklore study recur through the nineteenth century. Later, the anthropologist J. G. Frazer made the same assumptions when he spoke of survivals of ‘the old modes of life and thought’: ‘Such survivals are included under the head of folklore, which, in the broadest sense of the word, may be said to embrace the whole body of a people’s traditionary beliefs and customs, so far as these appear to be due to the collective action of the multitude and cannot be traced to the individual influence of great men’ (Frazer, 1918, I, p. vii).

Through the study of folklore, then, it was possible to reach back to the ‘age-old’ survivals that had been handed down from the ‘dim before-time’ by ‘oral tradition’, and thus to the ‘far-back ages’ when man was artless, natural and unbound by the artificial constraints of external mechanical society. Through this study, too, minority or despised groups could seek their supposed or claimed national roots; so the collecting of ‘folklore’ and ‘oral tradition’ went along with the upsurge of national feeling in the smaller European countries in the nineteenth century. We can see a similar process in the twentieth-century assertions of national identity: like the sponsorship of the Irish Folklore Institute and Irish Folklore Commission by the Irish government in the period following the establishment of the Irish Republic, or the emphasis on Negritude and the return to ‘our ancestral wisdom and folkways’ by some African politicians.

The approach to oral literature which connects it with the development of ‘folklore’ in the romantic and nationalist context is so dominant that as soon as one uses the term ‘unwritten’ or ‘oral’ or ‘folk’ literature, the whole series of assumptions crystallised in the term ‘folklore’ may rush into the mind.2 The various elements of the romantic interpretation are immediately evoked, and it is easy to take them as given and proved rather than the inheritance of one particular complex of ideas about the (wished-for) nature of society.

The common identification of ‘oral literature’ with ‘oral tradition’ thus becomes more comprehensible. ‘Oral literature’ (often assumed in this approach to be interchangeable with ‘folk art’, ‘folk literature’ etc.) is seen as arising in a spontaneous way and handed down, relatively unchanged, through unconscious ‘oral tradition’ into which conscious choice, judgement and ‘art’ do not enter.

These themes recur remarkably often in discussion of unwritten literature in this century as well. The supposed natural and artless quality is often emphasised. Fijian narrative poetry, for instance, is ‘totally unreflective, totally childlike’ (Leonard in Quain, 1942, p. vii), folk songs have ‘evolved unconsciously’ (Karpeles, 1973, p. 19) and the poetry of the ancient Germanic tribes of which some of the oldest remnants were, it is assumed, preserved and written down centuries later, ‘did not belong to the realm of conscious artistic creation’ (Rose, 1961, p. 5). An eminent authority can sum up ‘folk-song as it existed in the past’ as ‘an instinctive expression of the free artistic impulse in man, as natural as wildflowers’ (Bronson, 1969, p. 202). Cecil Sharp’s famous encounter with the gardener’s song ‘Seeds of Love’ showed him, his colleague Maud Karpeles writes, ‘the real significance of the folk-song tradition. It revealed to him the existence of a world of natural musical expression to which everyone, no matter how humble nor how exalted, could lay claim by virtue of his common humanity’ (Karpeles, 1973, p. 94). Similarly with ballads, whose study was part of the whole development of romanticism: they can be regarded as ‘non-art’, created by ‘the folk’ rather than individuals and characterised by a ‘lack of self-conscious formulations’ (‘The non-art of the ballad’, TLS, 1971), while ‘folksong’ is ‘the product of the spontaneous and intuitive exercise of untrained faculties’ and ‘the folk-singer, being un-selfconscious and unsophisticated and bound by no prejudice or musical etiquette, is absolutely free in his rhythmical figures’ (Vaughan Williams, 1934, p. 42). The same contrast between the natural quality of ‘primitive’ thought and the trained and conscious forms of civilised thinking crops up again in Lévi-Strauss’s opposition of la pensée sauvage to la pensée cultivée et domestiquée. It is a commonplace for writers on oral poetry under the title of ‘folksongs’ to claim, as in Karpeles’s An Introduction to English Folk Song, that the folk-song tradition is most noticeable among people ‘living close to nature’ (1973, p. 13). Again, the materials of ‘folklore’ (which includes ‘folk literature’) are said to constitute ‘the mythopoeic, philosophic, and esthetic mental world of nonliterate … or close-to-nature folk everywhere’ (Bayard, 1953, p. 9). Elsewhere ‘folklore’ is said to be ‘a precipitate of the scientific and cultural lag of centuries and millennia of human experience … deeply entrenched in the racial unconscious … Beauty [these primitive patterns] have because they were formed slowly close to nature herself, and reflect her symmetry and simplicity … the poetic wisdom of the childhood of the race’ (Potter, 1949, p. 401).

The communal and ‘folk’ element in unwritten (‘folk’) literature is also still commonly invoked as self-evident (even by those who reject more extreme theories of the communal origin of all such material). Folklore in general is ‘essentially a communal product’ (Kurath, 1949, p. 401) and the art (including literature) of primitive societies is ‘essentially communal’ (Kettle, 1970, p. 13), just as Polynesian myths and legends are ‘composite productions of the whole tribe’ (Andersen, 1928, p. 44), while ballads are ‘the voice of the people in the deepest sense in which that phrase can have meaning’ (Hendron in Leach and Coffin, 1961, p. 10).

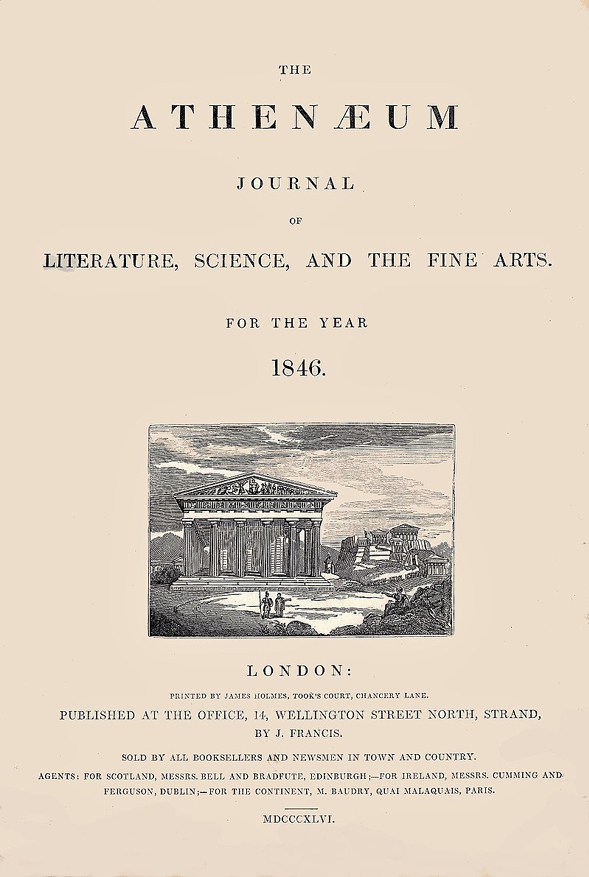

Intimately connected with the idea of the spontaneous and communal nature of unwritten literature is its continuing interpretation as oral tradition, as having been handed down over the ages. ‘Folk-memory’ is used to ‘explain’ the postulated continuity of some ‘oral tradition’ over many generations. For example, the ‘Daura legend’ among the Hausa is explained as ‘the crystallisation in the folk-memory of the peaceful union of the Berbers and Sudanese in the eleventh century which produced the Hausa peoples’ (Johnston, 1966, p. 113). In other cases oral tradition in more or less unchanged form is taken for granted as a natural and collective process, not needing further elaboration. Contemporary Ewe poems are described as ‘folk songs’ or ‘traditional songs’, and ‘known’ to be ‘almost as old as the Ewe people themselves’ (Adali-Mortty 1960), Hausa tales ‘lead right back into the mists of a remote past’ (Johnston, 1966, p. xlix) and the Wolof oral narratives told by Amadou Koumba draw ‘from his memory’ tales ‘that his grandfather’s grandfather had learned from his grandfather’ (Diop, 1966, p. xxiii). This sort of assumption is extrapolated into historical speculations about earlier oral literature. Some of the oldest epics in Persian literature are claimed to have been ‘handed down by men orally for some fifteen-hundred years’ (Boyce in Lang, 1971, p. 101), while the Gilgamesh poems, which were written down by the second millennium B.C. ‘probably existed in much the same form many centuries earlier’ (Sandars, 1971, p. 8). The assumed identity between ‘oral literature’ and ‘oral tradition’ comes out neatly in the indexes of many books where items of oral literature are jointly indexed under the general category of ‘oral tradition’.

Fig. 2.3. The Gilgamesh Dream tablet, 1732–1460 B.C. This dream tablet is a written version of part of the Epic of Gilgamesh in which the hero (Gilgamesh) describes his dreams to his mother, the goddess Ninsun. Iraq Museum, Baghdad. Wikimedia, https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gilgamesh_Dream_Tablet.jpg

Once the word ‘folk’ comes in too—as it does so readily in forms like ‘folk songs’, ‘folk poetry’ or ‘folk literature’—‘tradition’ is taken for granted as of central importance. Admittedly, there are controversies about the exact meaning of ‘folklore’, and many different suggested definitions: but in one survey of usages as recent as 1961 (Utley, 1961) the most common single characteristic was still ‘tradition’ and ‘traditional’. Here are some typical phrases from definitions of folklore by a series of authorities in the much-used Funk and Wagnalls Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology, and Legend (Leach, 1949, re-issued 1972): ‘the science of traditional popular beliefs, tales, superstitions, rhymes … essentially a communal product, handed down from generation to generation’ (G. P. Kurath); ‘traditional creations of peoples, primitive and civilized’ (J. Balys); ‘popular and traditional knowledge … has very deep roots … a true and direct expression of the mind of “primitive” man’ (A. M. Espinosa); while for the leading folklorist Stith Thompson, ‘the common idea present in all folklore is that of tradition, something handed down from one person to another and preserved either by memory or practice rather than written record’ (all quotations taken from entry under ‘Folklore’ in Leach, 1949, pp. 398ff). A similar emphasis is clear in S. P. Bayard’s conclusion that ‘one point upon which folklorists can safely be said to agree is that folklore is “traditional”’ (Bayard, 1953, p. 5). When oral or unwritten literature is, as so often assumed, just another way of saying ‘folk literature’, i.e. a species of ‘folklore’, it is small wonder that one essential characteristic of oral literature is assumed without question to be its ‘traditional’ quality.

The tone in which the assumed spontaneous, communal and ‘traditional’ nature of unwritten literature is expressed is still often that of the romantic and glamorised evocation of a far-off world, in keeping with the typical romantic yearning for the mysterious, organic and harmonious past. The words used are often emotive, and one often gains an impression that oral literature—‘oral tradition’—somehow takes place in a primaeval, natural context, where ‘the wisdom of our ancestors’ can be found and where natural emotions and expressiveness have free play, unlike the mechanical artificial bonds of our modern industrial world. ‘Oral tradition’ enshrines ‘Immemorial values and attitudes’ and can help us to fight the ‘waves of mechanization and depersonalization that threaten our life and thinking today’, as one folklore expert put it recently (The Times, 1971). Again an African writer speaks of ‘our rich, luxuriant folklore, whose roots strike deep into the earth … an incorporeal treasure... [which] has fed the mind through centuries, just as the parcel of inaccessible earth procures nourishment to the body’ (Dadie, 1964, pp. 203, 207). Writers on various forms of oral literature constantly make direct and indirect reference to the supposed ‘homogeneous’, ‘unsophisticated’, ‘communal’, ‘co-operative’ characteristics of the sort of culture where oral tradition or folk art ‘must have’ existed or ‘would naturally’ or actually ‘did’ thrive. ‘Folklore’, as one authority sums it up, is the product of ‘a homogeneous unsophisticated people, tied together not only by common physical bonds, but also by emotional ones which colour their every expression’ (MacE. Leach on ‘Folklore’ in M. Leach, 1949).

Besides the glamourising approach, there is also the dismissive one (often paradoxically combined with the romantic view), based on the premiss that ‘oral poetry’ or ‘folksong’ are not really suitable for sociological or even literary analysis. On the extreme view, ‘folklore’ or ‘traditional poetry’ is a’ survival’ from an earlier stage, a fossil preserved by unchanging tradition, not a part of functioning contemporary society or affected by conscious and individual actors. Even the less extreme view still tends to envisage oral poetry (under its categorisation as ‘folk literature’ or similar terms) as communal and ‘traditional’, unaffected by ordinary social conventions and differentiation. This relates to the whole idea that such literature represents ‘nature’ rather than ‘society’. Thus one consequence of the romantic interpretation was that those who embarked on consistent research on aspects of oral poetry—A. L. Lloyd, for instance—have tended not to receive recognition as serious scholars, while sociologists and literary scholars were in general encouraged to avoid oral poetry as a subject of academic study.

The whole romantic (and in places evolutionist) approach is pertinent to the subject of this book. Although much of the writing which adopts this approach refers to prose, poetry is often mentioned. The idea goes very deep that what is often described as ‘folk poetry’ or ‘folk song’ has come down through long ‘tradition’, and that it essentially belongs to the rural, natural and communal context so stressed by the romantic folklorist. As will already be evident, this approach is questioned in this book. Much of the detailed argument must be left to later discussion of, for example, the nature of transmission (chapter 5), of composition (chapter 3), the question of ‘individual’ as against ‘communal’ creativity (chapter 6), the functions and context of oral poetry (chapters 7 and 8) or the whole susceptibility of the subject to sociological and literary analysis (passim).

For the moment, two general points can be made about this approach (or set of approaches).

It is illuminating, in the first place, to set the assumptions involved against the historical background and intellectual movement in which they were formulated. This brings home that these are indeed assumptions, related to particular historical currents, and do not necessarily arise from solid empirical evidence. These assumptions should be regarded as at least open to question, and in principle testable by the findings of empirical research.

The other point is that folklorists too are now beginning to question some of these assumptions. In American folklore, for instance, there has been an increasing interest in urban and contemporary forms, in individuals’ varying styles, or in the change of function of a particular literary piece over time; there is a growing acceptance that these things are important and relevant to folklorists, who have also questioned some of the traditional assumptions. A recent influential statement by Ben-Amos, for instance, raises pertinent questions about the ideas of ‘communality’ and ‘tradition’ (1972, pp. 7–8). He suggests that the framework of preconceptions held by folklorists in the past has interfered with the understanding of the subject: ‘These attempts to reconcile romantic with empirical approaches actually have held back scientific research in the field and are partially responsible for the fact that, while other disciplines that emerged during the nineteenth century have made headway, folklore is still suffering growing pains’ (1972, p. 9). When to this is added the growing interest by a number of sociologists and folklorists in modern ‘popular culture’ and the ‘mass media’—topics which partially overlap with contemporary oral poetry—it can be seen that the romantic approach, still deeply influential, is at least in part being questioned, even rejected, by some who, a generation ago, could have been expected to have been its strongest exponents.

I have thought it worth while to treat the background to this approach in more detail than the others because of its profound and continuing influence on the whole study of oral literature. It is part of the widely accepted stock of ‘what everyone knows’ about oral literature. And until one recognises that these assumptions are assumptions belonging to one particular approach and are not as yet necessarily proved it is difficult to carry out any empirical study without potentially misleading preconceptions.

2.2 The ‘historical-geographical’ school

A second approach that has been very influential in the study of oral literature is the so-called ‘historical-geographical’ school. This approach first became pre-eminent in Scandinavia (hence its frequent description as the ‘Finnish’ school); it was later taken up by American folklorists and now has a widespread influence. It has concentrated particularly on oral prose narratives—usually termed ‘folktales’ in this school—but the repercussions of the method, together with its implicit assumptions, have affected the approach to oral literature generally (again under the title of ‘folk literature’).

Scholars of this school take some particular literary item—most often a story—and try to trace its exact historical and geographical origins, then plot its journeys from place to place. Their interest is in reconstructing the earlier ‘life history of the tale’, working back to the first local forms, hence to the ultimate archetype from which, it is argued, these local variants all derive, in much the same way as later manuscript forms of a written piece can be traced back to an original manuscript archetype. For example, one particular plot—the ‘root motif’—which tells how a crocodile was misled into releasing his hold on a potential victim’s foot when told it was a root, has been traced from its African and American variants back through Europe and finally to India (Mofokeng, 1955, pp. 123ff). Similarly ‘the star husband tale’—the marriage of two girls to the stars followed by a successful escape—has been studied in its many variants over a wide area in the United States and Southern Canada with its origin postulated as somewhere in the Central Plains (Stith Thompson, in Dundes, 1965, pp. 414ff).

To aid the process of recognising the ‘same’ tale in its various guises at different places and times, folklorists of this school have laid great emphasis on developing systems of classification. Plots, motifs and episodes have been classified and labelled, so that any given item can be isolated, identified and followed by a systematic mapping of its occurrences, and hence the eventual tracing of its origins. In this way all the variants of a tale can be collected and divided into their various components, so that finally the ‘life history’ of that particular tale can be established. The most monumental of the systems of classification is Stith Thompson’s massive Motif Index of Folk Literature (6 volumes, 1955–8), but the general interest in classification and typologies runs through all the work of this school, and beyond. Any collection of tales was deemed incomplete—in fact not even to have started on the process of analysis—if it did not include references to the relevant types in Thompson’s Motif Index, and, where possible, comparative material on occurrences of the same types elsewhere.

This approach to the study of ‘folk literature’ is perhaps a method rather than a theoretical construct involving a set of explanatory assumptions. But in practice it has acquired a number of implicit assumptions about the nature of oral narrative and a general emphasis on certain aspects of literature. These have washed off onto the study of oral literature more generally (including oral poetry).

The first characteristic is the emphasis on the content of literature. Plots, episodes and motifs are assumed to provide the substance of literature, with the implicit conclusion that these constitute the literary piece involved, what essentially defines it. No account is taken of factors like performance, occasion for delivery, social context or function or, indeed, the varying meanings that the same words may have for different audiences. For the historical-geographical analysts the content as defined and classified in standard typologies is what matters and what gives the essential reality of the piece: ‘subjective’ characteristics like local meaning or social context are, for their purposes, irrelevant.

To play down the social context and mode of performance of oral literature is to give a very truncated picture of its nature and essence. Even with written literature, to ignore the social background and public to which it is addressed gives a misleading view of its significance. And with oral literature, the import of a particular piece can scarcely be discovered from the textual content alone, without some attention to the occasion, audience, local meaning, individual touches by the performer at the moment of delivery, and soon. The concept, furthermore, of the diffusion of particular plots and motifs throughout the world is often stated in such a way that the active force seems to be the motifs and texts themselves rather than the performers or audiences of the oral works in question. The creative role of local poets or the effect of a participating audience in helping to mould a traditional motif into a new and unique literary act is played down in favour of an almost botanical concentration on the collection and classification of ‘types’ and their distribution. Thus the active part played by local participants in a given oral literature tends to be overlooked.

The method is clearly more difficult to apply to poetic than prose texts, for with poetry it is harder to argue that the essence of the piece lies in the subject-matter—in certain ’motifs’, say—and that the language in which this is expressed and the style the poet chooses are of secondary importance. A few folklorists have tried to pursue a version of the historical-geographical method with ‘folk songs’, and have attempted to reconstruct the travels of particular poems. Hugh Tracey, for instance, (in Dundes, 1965) tries to trace an old lullaby sung in Georgia in the United States to Zambezi a century earlier, while Archie Taylor (1931) finds that the song Sven i Rosengård came originally from the song Edward which travelled from Britain to Scandinavia; and questions have often been pursued about the origins and travels of European and American ballads (e.g. Brewster, 1953, Wilgus, 1959).

The general notion that content and its transmission are of the first import has often led to an underestimate of the significance of style or of the personal contribution of the individual poet. But by and large this method has not often been applied directly to the analysis of poetry, so that the massive collecting of texts inspired by this approach has tended to pass poetry by. This is one reason for the widespread impression that unwritten folk literature consists mainly of prose narratives—‘folk tales’—and has little place for poetry.

The historical and geographical folklorists have always stressed the existence of large numbers of variants—the ‘same’ plot or episode is expressed in varying words in a way typical of the transmission of a tale through ‘oral tradition’. But even so, the emphasis on general textual content to the exclusion of social context reminds one of the exclusive emphasis on the text in some literary criticism. The idea that having got ‘the text’ one then has the essence of the piece one wishes to study, and that other considerations are at best secondary and perhaps wholly irrelevant has had a great influence on the study of oral literature. It has meant that, until recently, investigators have felt largely satisfied with recording text after text, while including nothing on detailed social background, personality of the composer and performer, methods of reward, nature of audiences and so on—all the questions which would normally arise in the sociology of literature. Once the assumption is made that ‘the text is the thing’, these other questions fade into insignificance.

Fig. 2.4. An illustration of Anansi the spider by Pamela Colman Smith, 1899. Anansi is the subject of numerous tales throughout West Africa which spread prolifically to the Caribbean; this is an example of the historical geographical theory. Wikimedia, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Anansi#/media/File:Anansi-34.png

It will be clear that assumptions associated with this school have had great influence on the analysis of oral literatures and that some of them are controversial. They have been questioned by sociologists generally (perhaps particularly by the British school of functionalist anthropologists), and also in a number of analyses of particular instances of oral literature. A. B. Lord, for instance, in his classic work The Singer of Tales (1968a, first published 1960) has made plain the importance of the creative act by performer composer in Yugoslav oral epic, and has argued that the concept of the correct or original text is inapplicable to oral poetry, where each performance produces a unique and individual poetic creation (this is described further in chapter 3).

Similarly recent research in America has uncovered the complex interplay in ‘folk poetry’ and ‘folk song’ between ‘tradition’ on the one hand and the individual creator, local audience and social context on the other (e.g. Stekert, 1965, Wolf, 1967, Glassie et al. 1970, Abrahams, 1970a). And the interest in performance by some recent American folklorists, with their view of folklore as ‘a communicative event’ involving social interaction has explicitly involved both a rejection of the ‘Finnish’ school of folklore—‘It is becoming trite to criticise the much criticised Finnish method; but there is no doubt that part of our troubles may be traced to it’ says Paredes (Paredes and Bauman, 1972, p. ix)—and a questioning of the importance of the concepts of ‘oral transmission’ and ‘oral tradition’ (Ben-Amos, 1972, p. 13). All in all, there is much to query in the approach of the historical-geographical school, but some knowledge of its influence is necessary for an understanding and assessment of the often unspoken assumptions in many authoritative publications.

2.3 Sociological approaches and the sociology of literature

So far the approaches discussed tend to be regarded as part of the development of ‘folklore’—ones which would be familiar to every folklorist but are usually felt to be beyond the scope of the social scientist. But there are also approaches and controversies normally accepted as central to the sociology of literature but which are, in turn, often ignored by folklorists. One question for sociologists of literature has long been: just what role does literature play in society? Does it reflect the current culture and social order with more or less directness? And if it does, is this reflection selective, or does it cover ‘the whole’ of society? Or does literature go beyond a passive role like ‘reflection’ and play an active part in the working of society?

These questions point to aspects neglected in the previous approaches. In the work of some analysts, the reflecting role of literature is taken for granted (that of the Chadwicks, for instance—see chapter 8 below). Others stress the active and functional aspect of literature. Several have described how literature can play a part in the maintenance of social control or the socialisation of children through the ‘lessons’ it teaches. Similarly poems like hymns, secret society songs, or initiation verse can be shown to contribute to the solidarity and self-awareness of certain groups and hence, often, to a maintenance of the status quo. This aspect is brought out by functionalist writers—anthropologists like Malinowski or Radcliffe-Brown and their followers—and, in a different way, by the Marxist critics who have pointed out that literature can function as a ‘tool of the ruling class’, propagating its ideas and interpretations. In reply, other analysts have pointed to the part literature often plays in social and intellectual change. This used to be a common view of authors: they take the lead in cultural progress, and formulate new ideals and deeper insights. More recently the detailed role of particular literatures and their manifestations has been much discussed. Marxists see literature as a potential weapon in ‘the class struggle’—hence their interest in ‘popular literature’, ‘the people’s songs’ and so on. Others point out how, say, political songs can make an impact during an election campaign, how satirical writings can undermine, even topple, established authority; or how new ideas and policies can be consciously propagated through popular literary forms. From the point of view of the social scientist, literature is a social and not just a private phenomenon, far less a ‘natural’ and quasi-botanical one, and it is therefore subject to the kind of investigation relevant in the analysis of any social institution. That this involves controversy is certain, but it is controversy about the kinds of social-scientific questions often ignored in the other approaches.

In much work on oral literature it has seemed easy to overlook such controversies, and to take one or other answer for granted as the only possible one, as if the wider controversies about literature as a social phenomenon do not apply in this field. Thus a number of writers (including some sociologists and social anthropologists) have taken it for granted that oral literature can best be analysed in functional terms. It is then interpreted as primarily either reflective or else as upholding the status quo, a role which British functionalist anthropologists particularly emphasised. The aesthetic and ‘play’ element tended to be brushed aside as irrelevant to proper sociological analysis, and the study of the detailed functions of particular literary pieces and genres—potentially heterogeneous and changing—neglected in favour of one monolithic generalised theory about the expected function of oral literature. Another common conclusion concerns the ‘democratic’ nature of oral literature: it is assumed to be the possession of ‘the people as a whole’. This assumption is particularly strong when the term ‘folk literature’ is used (as it often is). It seems to be implied in the term itself that it ‘belongs to all the people’, is ‘the wisdom of the people, the people’s knowledge’ (Sokolov on ‘folklore’, 1950, p.3) or (of ‘folk music’ or ‘folk song’), that it is ‘a democratic art in the true sense of the word’ (Karpeles, 1973, p. 11) and so on.

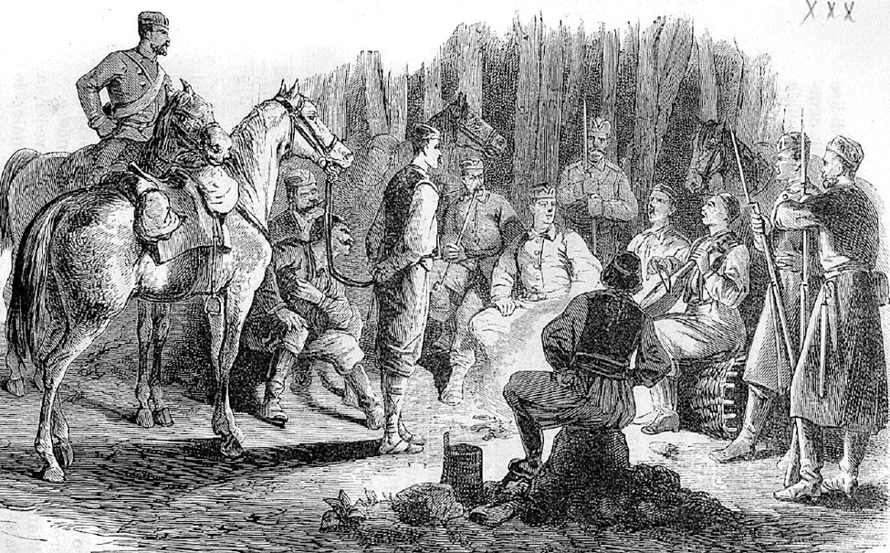

Fig. 2.5. An illustration of people listening to Guslar song about the death of Lazar, during the Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–78), at an encampment in Javor. This shows that oral poetic performance is a social and communicative event. Wikimedia, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/

Guslar_singing_of_the_death_of_Lazar

%2C_at_an_encampent_in_Javor.jpg/1024px-Guslar_singing_of_the_death_of_Lazar%2C_at_an_encampent_in_Javor.jpg

Yet to any self-conscious sociologist of literature, these points about the detailed functions and the extensiveness of distribution of particular literatures or genres are all questions at issue. The answers given by the researcher may depend partly on the general theoretical position he takes up on such issues—though such a position needs to be a conscious choice between possible alternatives rather than mere unconscious assumption. Even more, it must depend on the results of empirical investigation into the facts of a given literature. Sometimes a wide range of disparate and changing functions can be detected and the examples studied may or may not lend support to the established order. And contrary to the preconceptions of many folklorists, certain items which they would classify as ‘folk literature’ turn out to be closely identified with one particular group (perhaps a powerful monopolistic elite of trained poets) and only in a very extended sense to be a possession of ‘the society’ or ‘the folk’ at large, on a spontaneous and necessarily un-self-interested product of the people as a whole.

These questions are given further discussion later, particularly in chapters 7 and 8. The point to notice here is that they are questions and have to be treated as such.

2.4 Two ‘ideal types’ of society and poetry

The final approach to be considered here has been implicit at several points earlier. This is the approach basic to much classic sociological theory, in which two models or types of society are postulated, standing in contrast to one another. This is explicitly formulated in the writings of Durkheim and has been echoed by other theorists since. On the one hand, there is the model of ‘primitive’ or ‘non-industrial’ society: small-scale and homogeneous, conformist, ‘oral’ rather than literate, communal, dominated by religious and traditional norms and the ties of ascribed ‘kinship’; un-selfconscious, and probably more ‘organic’ and ‘close to nature’ than ourselves—or at any rate untouched by the mechanisation and advanced technology of our society. Opposed to this is the model of modern industrial society—secular and rational; heterogeneous; dominated by the written word and oriented towards achievement and individual development; and at the same time highly mechanised and specialised, typically bound together by artificial rather than ‘natural’ and ‘organic’ links.

The opposition of these two models has, in various forms, run through the writings of sociologists and anthropologists for a century or so, from the classic expositions of Durkheim or Tönnies to those of Parsons, Merton or Redfield. It is a dichotomy between two basically differing types of society that has had profound influence in sociological writing and has coloured the attitude of sociologists both in their construction of theories about society and in their assessment of the institutions existing in the so-called ‘primitive’ type.

The repercussions of this basic dichotomy have influenced the interpretation of the role of oral literature by both sociologists and folklorists. It is not logically necessary, even accepting the two models at their face value, that oral literary forms should occur only in the ‘primitive’ type of society. But the assumption is easily made, and once it is made the supposed characteristics of the society wash over onto the whole assessment of oral literature. Generalisations like that of Notopoulos become plausible: ‘the society which gives birth to oral poetry is characterised by traditional fixed ways in all aspects of its life’ (1964, p. 51), or Hendron’s characterisation of the typical ‘folk singer’: ‘he lives in a rural or isolated region which shuts him off from prolonged schooling and contact with industrialised urban civilization’ (in Leach and Coffin, 1961, p. 7).

In such statements, the ‘primitive’ context is seen as the most common and, as it were, ‘natural’ context for oral poetry. Like the society in which it occurs, oral poetry can be assumed without further inquiry to be un-selfconscious, communally rather than individually oriented, and produced in a homogeneous setting with little or no specialisation by poets or audiences. Similarly, oral poetry in such societies can be assumed to be ‘natural’ and artless, arising from spontaneous emotion rather than conscious art. Furthermore, oral literary forms occurring in other contexts, in societies with partial or mass literacy, can be assumed to be not the ‘natural’ form, but an aberrant and unusual type. This can be ignored as untypical or explained away as merely ‘transitional’, perhaps a ‘survival’ from the ‘primitive’ oral type of society, its ‘natural’ setting.

Not all sociologists would take this extreme line, and when the assumptions involved are stated explicitly would be likely to question them. But this set of assumptions implicitly underlies the attitude of many sociologists to oral literature and helps to explain why many have thought it not worth studying. While the emphasis in sociological theory on these two opposing models of society continues and is reinforced in elementary textbooks and university teaching, this implicit assessment of the nature and setting of oral literature is likely to remain influential.

When these assumptions are brought into the open, it is clear that they are questionable. In the present context, they can be tested on two main fronts: first, the postulation of the ‘primitive’ or ‘oral’ type of society as the primary setting for oral literature; and second, the general validity of these two contrasting models of society.

Anyone looking at the research on oral literature, and the various collections of texts now available will find that the typical ‘primitive’ society is not necessarily the most common setting. It is not in fact more ‘normal’ for oral literature to be practised in such society.

This comes out in ways that make the point more than a definitional one about how widely one uses the term ‘oral’; and this throws new light on the distribution of unwritten literature.

First, most of the examples of oral literature which we possess and analyse have not been collected from pure ‘primitive’ cultures. In practice it is rare for collectors and recorders to operate except in conditions that to some extent run counter to the extreme ‘primitive’ society. True, there are rare and partial exceptions, but by and large our recorded examples of oral literature in so-called ‘primitive’ cultures could never have been made in the first place without the use of writing and/or some penetration by foreign observers, and without the presence of at least some administrative, missionary or educational services. We are so ready to picture our oral items as coming from some ‘uncontaminated’ and ‘primitive’ oral stage of culture, that we ignore the conditions in which our examples were for the most part actually recorded: written down by schoolboys for their missionary teachers, painfully dictated by oral practitioners prepared to spend time with foreign researchers or to travel to an urban and scholarly centre, or observed by visitors complete with back-up apparatus and train of hangers-on. This is not to denigrate the methods or achievements of early or recent collectors. But to pretend that most collections were made in a pure and primitive type of culture is simply untrue.

It can, of course, be retorted that the conditions in which oral pieces have recently been collected are merely contingent, and nothing to do with the real nature of oral literature which is presumed to have existed for millennia in the ‘pure primitive state’ before writing was invented, and for even longer in areas of non-literacy before recent penetration by European literate traditions. This is true. But for detailed scholarly investigations we can scarcely afford to spend over-long on speculation about what must or might have been so in the past. We have to analyse the examples of oral literature we do have access to, either directly or in texts or recordings. One has to face the unromantic truth that few or none of these are directly recorded from the extreme type of primitive culture envisaged in the common dichotomy.

There is in any case great variety among indigenous cultures themselves. Certainly there are wide areas in which (until fairly recently) people had basically no contact with the written word: Melanesia for instance, the interior of New Guinea, the Native Australians, or many of the American-Indian groups. But a large number of the cultures most readily classed as ‘primitive’ lived at least on the edges of a literate tradition. It is easy to overlook this, but one need only cite the influence of China, with its learned civilisation, over vast areas of Asia; the effects of Arabic learning and the religion of ‘the Book’ in many parts of Africa; or the impact of Roman and Christian learning on oral and vernacular forms in mediaeval Europe. It has to be accepted that a number of the cultures normally classified as primitive have had generations or centuries of contact with literacy, and that the examples of oral literature we study are as likely to come from a culture of this kind as from one traditionally untouched by any experience of literacy.

Apart from differences in the degree of contact with literacy, societies can also be grouped according to the degree of specialisation in literary activity. In some there is very little—thus fulfilling assumptions about the undifferentiated ‘primitive’ type of society so far as literature is concerned. But in others there is a definite tradition of literary and intellectual specialisation. In such cultures there may be a conscious learned tradition in which literary specialists deliberately train new recruits into their acquired skills—the poetic training in Ruanda in Central Africa, for instance (Kagame, 1951, chapter 9), the Maori ‘school of learning’ (Best, 1923), the Uzbek singer-teachers (Chadwick and Zhirmunsky, 1969, p. 330) and perhaps the early Irish poetic schools (Chadwick, 1932, pp. 603ff). These often involve careful control over recruitment and, sometimes, monopoly over particular types of literary productions. They are far from the unconscious and undifferentiated kind of culture assumed as the characteristic context for oral literature. This is not a matter of the odd exceptional case; a large proportion of recorded oral literature—for instance the vast corpus of oral epic poetry from Central Asia—comes from this kind of context.

One can also question the whole formulation of these two contrasting types, as put forward in classic sociological theory. Either as empirical generalisations, or as abstract ‘models’, these two postulated ‘types’ of society surely now need a critical re-assessment. Do societies of the kinds postulated actually exist, and if so how widely? And if the types represent conceptual models only, are these illuminating or misleading ones? The study of oral literature can lead to doubts of their validity and usefulness. These doubts have been expressed by other sociologists in more general terms. Lemert puts it well in the context of one particular implication of this typology.

It is theoretically conceivable that there are, or have been societies in which values learned in childhood, taught as a pattern, and reinforced by structured controls, served to predict the bulk of the everyday behavior of members and to account for the prevailing conformity to norms. However, it is easier to describe the model than it is to discover societies which make a good fit with the model ... It is safe to say that separatism, federation, tenuous accommodation, and perhaps open structuring, are at least as characteristic of known societies of the world as the unified kind of ideal social structure based on value consensus which impressed Durkheim, Parsons, and Merton.

(Lemert, 1967, p. 7)

Add to this the increasing knowledge we have gained from the work of anthropologists and others about the diversity of forms that ‘non-industrial’ and ‘Third World’ societies can take, and it becomes an issue to be faced whether sociologists should not now radically rethink the basic dichotomy between models of society on which so much earlier writing was based. It is a real question whether they have not become more misleading than illuminating.

With this in mind, it is interesting to hark back to the earlier discussion about romanticism and the assumptions of romantic thought in the nineteenth century. It is worth remembering that much of the classical sociological theory which has so influenced later generations was formed in this period. It too bears the impress of precisely the same kinds of assumption. It is not difficult to detect the same romantic evocation of the natural and organic ‘state of nature’, untrammelled by the mechanical and artificial bonds of today, in the models produced in scholarly writings of the time. This is evident in many of the classic formulations of what has been termed ‘the sociological tradition’ (Nisbet, 1970). There is Tönnies’s Gemeinschaft with its collective ‘harmony’ based on ‘folkways’ and ‘folk culture’ and rooted in ‘imagination’, in contrast to the rational arbitrary nature of Gesellschaft, based on ‘thinking’ and liable to lead to ‘the doom of culture’ unless one can revivify the ‘scattered seeds—and again bring forth the essence and idea of Gemeinschaft’; Durkheim’s societies with low division of labour and emphasis on the collective as against those which are more ‘rational’ and where ‘tradition has lost its sway’; or the Marxist view of the simple, unchanging and communal nature of pre-capitalist society in contrast to the exploitation involved in ‘civilisation’ with the increasing division of labour. In these great dichotomies between different types of society postulated by the classic social theorists and most often perpetuated today under the terms of ‘traditional’ as opposed to ‘modern’, one can see the continuation of the romantic tradition, accompanied by some of its emotive associations.

Tracing intellectual antecedents and congeners is not in itself an indication that certain formulations are wrong. But it does remind us of the need to ask ourselves whether certain generalisations (in this case about types of society) formulated at a particular time and place and in a certain cultural context are necessarily and universally valid, however many respectable followers have repeated and transmitted them since. Certainly, so far as the study of oral poetry is concerned a close look at the assumptions involved is very much overdue.

I have not tried to give a comprehensive account of the many different theoretical positions taken up in the study of literature. Even the briefest historical survey of these would have had to consider many not mentioned here—like the psychological interpretations based on Jung and Freud, ‘communication studies’ and semiology, ‘structuralism’, the whole ‘Parry-Lord’ school (discussed further in chapter 3), the various controversies within ‘literary criticism’ and so on. Again a full account would have to mention the many excellent studies of oral literature carried out in the nineteenth century and earlier this century (like the Chadwicks’ monumental work, research in Eastern Europe, and collections and analysis by scholars and amateurs all over the world). Rather than trying to provide such a summary (which can to some extent be found elsewhere e.g. Bascom, 1954, Dorson, 1963, Andrzejewski and Innes, 1972, Wilgus, 1959, Jacobs, 1966, Greenway, 1964, chapter 8; also Finnegan, 1974b), my aim has been to elucidate certain themes underlying the approaches to oral literature that are persistently influential yet often unrecognised. Because of this they can impede understanding and research by implying that assumption is fact. Once these assumptions are explicitly recognised as such, they can become useful stimuli rather than hindrances to future research.

|

|

Fig. 2.6. The covers of two books portraying two contrasting approaches to oral poetry: as a tribal, uncreative, non-individualistic routine in a jungle (cover image of the Oxford University Press’s edition of Finnegan’s Oral Literature in Africa, 1997); as a sophisticated, individual, creative act in the real world (cover of the same book, this time fully illustrated, 2012, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0025).3

This preliminary discussion suggests that we are more ignorant of some of the general processes involved in oral literature and its social contexts than many confident early assumptions allow; and in particular that the kinds of generalisations which suggest that all ‘oral poetry’ necessarily belongs to one single ‘type’ rather than including many diverse manifestations can prove to be misleading rather than helpful.

1 From Joseph Warton’s The Enthusiast (1970), a poem often quoted as the first clear manifestation of romanticism.

2 ‘Folklore’ does not exactly coincide with the term ‘oral literature’. Whatever the controversies about its exact meaning, all scholars, it seems, agree that it includes (most of) what could be termed ‘oral literature’ and the majority would probably see oral literature as comprising a major part of ‘folklore’.(For further discussion of the controversies over the exact delimitation of the field of folklore see essays in Dundes, 1965).

3 It is indicative of the changing approach over a generation to compare the dark, jungle-immersed, stereotypically ‘tribal’ image of Africa with the lively, aesthetic, and extremely individual Mandingo singer—covers for the very same book but, forty years later, vastly different in concept.