5. Transmission, distribution and publication

©2025 Ruth Finnegan, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0428.05

The question of how oral literature reaches its patrons can never be a mere secondary matter; for its very existence depends on its realisation through verbal delivery. Certain forms can perhaps be said to be retained purely in someone’s mind, through memorisation, but there must be some opportunity for him to pass this on through verbal recitation: otherwise the piece loses its existence and dies with him. This is not the case with written literature where a piece may remain in existence in written form over long periods of time and be rediscovered generations or centuries later. With written literature we can therefore partially divorce discussion of composition and content from the details of how it is/was transmitted and reached its various audiences. With unwritten literature these questions are central topics, intimately related to composition, content and authorship.

There is a further reason why the ‘transmission’ of oral literature needs special consideration. This is the crucial part this concept plays in the studies of many scholars concerned with oral literature, in particular the ‘folklorists’. For them ‘oral transmission’ is not only the central focus of much of their interest, but is often taken to be the most important defining characteristic of ‘folk literature’. Unless it undergoes at some point the process of verbal handing on through oral transmission a poem will not qualify as ‘folk poetry’ (see e.g. Boswell and Reaver, 1969, chapter 1; Dundes, 1965, p. 1ff; Utley in Dundes, 1965, pp. 8ff; Dorson, 1972, pp. 17 and 19). Some folklorists admit that this narrow definition must surely exclude some varieties of ‘oral literature’ (recently composed poems, for instance, which even if ‘oral’ in their composition and performance do not ‘sink into tradition’ or ‘pass into general oral currency’). But the folklorists’ delimitation of ‘literature orally transmitted’ is often assumed to cover the whole field of oral literature—or anyway the main field of interest to the scholar—and this aspect thus demands attention. The concept of ‘oral transmission’ is therefore inevitably of central importance.

Apart from the theoretical reasons for an interest in transmission and distribution, one is forced to notice such questions because of some of the striking facts discovered about the travels and distribution of some oral poetry. Far from only having an ephemeral and local existence through particular performances to a personal audience, certain oral forms are found in continuing and relatively unchanged existence over vast areas of the world and through long periods of time; and since the literature is oral, it has seemed reasonable to suppose that the prime vehicle for this transmission is, equally, oral.

Before entering into the various controversies about the nature and significance of oral transmission, it may be helpful to consider briefly some well-known instances of apparently lengthy oral transmission over space and time. These instances will be referred to later in the chapter in the context of the various theories and controversies that surround the subject of ‘oral transmission’.

5.1 Oral transmission over space and time: some striking cases

Perhaps the most striking and well documented cases are the stories so often termed ‘folktales’, that crop up throughout the centuries and throughout the continents in near-identical form—so far as plot and motif go.1 For many of these tales ‘life-histories’ of their transmission have been traced, and there is massive documentation of the occurrence of basic plots and motifs (notably in Thompson, 1955–8).

Less evidence of this kind has been collected for oral poetry—understandably more resistant to the kind of measurement and delimitation that is (arguably) possible for the content of prose stories. But there are still some remarkable instances of wide and lengthy transmission.

One example is that of the Gésar epic cycle. This tells the tale of Gésar or Kesar, the king of a legendary land named Glin. It is known in Central Asia, throughout Tibet, Mongolia and parts of China. The basic incidents of this long epic are the same throughout this vast area and apparently date back several centuries at least (Stein, 1959).

Fig. 5.1. Statue of King Gesar in Maqen County, Qinghai. Wikimedia, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/07/Statue_of_King_Gesar_%28cropped%29.JPG

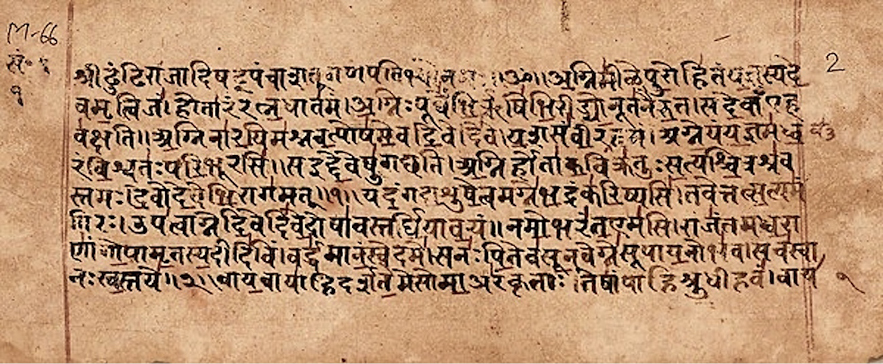

The Vedic literature of India provides an even more striking example of lengthy transmission. The Rgveda itself is said to have been composed around 1500–1000 B.C. and to have been handed down by oral tradition for centuries. The religious and liturgical nature of the text has, it seems, made verbal memorisation imperative, and it is claimed that even if all written versions were to be lost ‘a great portion of it could be recalled out of the memory of the scholars and reciters’ (Winternitz, 1, 1927, p. 34) and ‘the text could be restored at once with complete accuracy’ (Chadwick, 11, 1936, p. 463). This, if true, clearly represents an extraordinary emphasis on memory in Indian culture—for the Rgveda runs to about 40,000 lines (it consists of 10 books including in all over 1,000 hymns)—and would comprise a most remarkable instance of lengthy oral transmission over space and time.

If there is inevitably some speculation about the early history of the Vedic transmission, the evidence on certain more recent cases is much more solid. Here the best documented case is that of the transmission of certain English and Scottish ballads to America and Australia. The time involved is shorter than that claimed for the Vedic instance—centuries rather than millennia—but the facts are striking enough. Over a period of up to 300 years, popular ballads were handed on from generation to generation from the period when they were first brought out by immigrants from the British Isles, to the date in the twentieth century when they were noted and recorded by collectors. Some of the ballads arrived with later waves of immigrants and had a shorter (apparently) independent existence, but a number go back to the date when European immigrants first began to settle in America.

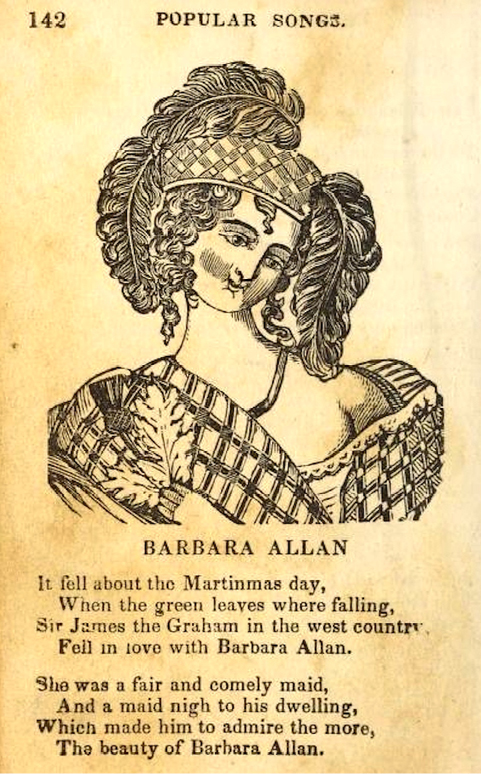

One of the best-known ballads is Barbara Allen. Here are two versions, the first, from a British source, dating back to at least the first half of the eighteenth century, and represented in Child’s classic collection of The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (no. 84). The second is one of the many variants collected by Sharp in the Appalachian Mountains of the American South in the early twentieth century, apparently derived from the first settlers in the area over many generations of oral tradition.

The likenesses in the two versions are impressive indeed. Sharp describes the isolation of the Appalachian Mountain region, and its consequent reliance on the culture brought with them by the early settlers from Britain

The region is from its inaccessibility a very secluded one … Indeed, so remote and shut off from outside influence were, until quite recently, these sequestered mountain valleys that the inhabitants have for a hundred years or more been completely isolated and cut off from all traffic with the rest of the world. Their speech is English, not American, and, from the number of expressions they use which have long been obsolete elsewhere, and the old-fashioned way in which they pronounce many of their words, it is clear that they are talking the language of a past day, though exactly what period I am not competent to decide

The local people were, Sharp argues, dependent for their knowledge of the ballads on long oral transmission: on what their ‘British forefathers brought with them from their native country and has since survived by oral tradition’ (p. xxviii).

A case like this provides such a striking instance of long transmission that it is tempting to take its apparent course as a model for the transmission of all oral literature. This has been a common reaction among some folklorists. Instances of the longevity of ballads within England too have been claimed as further evidence. Thus Sharp, on ‘the amazing accuracy of the memories of folk singers’

A blind man, one Mr Henry Larcombe, also from Haselbury-Plucknett sang me a Robin Hood ballad. The words consisted of eleven verses. These proved to be almost word for word the same as the corresponding stanzas of a much longer black-letter broadside preserved in the Bodleian Library.

The words of the ballad have since been reproduced in other books, e.g., in Evans’ Old Ballads, but, so far as I am aware, they have never been printed on a ‘ballet’ or stall copy, or in any form that could conceivably have reached the country singers. I cannot but conclude, therefore, that Mr Larcombe’s version, accurate as it was, had been preserved solely by oral tradition for upwards of two hundred years.

It would be easy to multiply instances of this kind without going beyond my own experience; but these are sufficient for our purpose. The accuracy of the oral record is a fact, though, I admit, a very astonishing one.

This view of the ‘amazing accuracy’ of the oral record fits certain widely-held views about the nature and transmission of oral poetry generally. Thus it can be asserted that ‘traditional ballads’ like Lord Randal or Chevy Chase have been transmitted in such a way that through them we have contact with ‘the product of the pre-literate rural community living in an atmosphere of beliefs and rituals of immemorial antiquity’ (Pinto and Rodway, 1965, p. 20), some of them transmitting beliefs ‘which must have grown from pre-Christian religion’ (Hodgart, 1971, p. 15). Similar comments, often with no evidence given, are made about instances from all over the world. The texts of Ob-Ugrian epics and songs, for instance, ‘have been transmitted orally for centuries’ (Austerlitz, 1958, p. 9), Inuit literature in Western Greenland was ‘orally handed down from “days of yore”’ (Thalbitzer, 1923, p. 117), and Indian ‘folksongs’ ‘have roots … [in] the depths of the past’ (Arya, 1961, p. 48); one ingenious account of the well-known rhyme ‘Eeny, meeny, miny, mo’ even derives it ‘from Druid days when victims were taken across the Menai Strait to the island of Mona for sacrifice’ (Boswell and Reaver, 1969, p. 72). For earlier periods too it has seemed reasonable to scholars to extrapolate from what they consider firm assumptions and make statements that, for instance, the oldest Icelandic poetry ‘must have lived orally in Iceland for generations before it was written down’ (Turville-Petre, 1953, p. 7) or that the Gilgamesh poems written down by the second millennium B.C. ‘probably existed in much the same form many centuries earlier’ (Sandars, 1971, p. 8).

A picture seems therefore to emerge of lengthy unchanging transmission over wide areas and/or through long periods of time as the expected mode of oral transmission. And the comparative evidence from the more recent ballad case seems to make it reasonable to assume this model for the earlier cases too, even where there is no direct evidence.

5.2 Inert tradition, memorisation or re-creation?

Evidence of lengthy transmission through space and time thus seems solid and straightforward, in cases like Anglo-American ballads or Vedic literature, and we seem to have arrived at an empirically tested generalisation about the nature of transmission.

But it is by no means certain that long transmission on the model of these instances applies to all cases of oral literature. It is important to ask whether other means of transmission and distribution are found. How far can a model based on the ballads and the Rgveda be extrapolated? And is it the correct one even for these cases in the light of modern scholarship? The whole topic of transmission is in fact more controversial than at first appears. Some of the different theories that have emerged will be surveyed briefly here. The approaches that need to be considered are (1) the ‘romantic view’ about the long transmission of oral poetry from far-back ‘communal’ origins; (2) the theory of oral transmission as essentially memorisation; and (3) the theory of transmission as a process of re-creation, an approach which overlaps with the oral-formulaic theory. (Discussion here must be brief; further details can be found in the references given, especially in Wilgus, 1959 and McMillan, 1964).

First, there is the extreme romantic approach which has had great influence in the whole field of oral literature and, in particular, in approaches to the transmission of ballads. This is exemplified, for instance, in the writings of Gummere.

In this view—discussed in its historical context in chapter 2—near word-for-word transmission over long periods (even centuries or millennia) is both possible and normal, and takes place by ‘pure’ oral tradition, uncontaminated by influence or interference from written or printed forms. Hendron’s portrait of the ballad singer and ‘folk singer’ has been echoed in many similar accounts: one who ’lives in a rural and isolated region which shuts him off from prolonged schooling and contact with industrialized urban civilization, so that his cultural training is oral rather than visual’ (Hendron in Leach and Coffin, 1961, p. 7). The origin of ballads and other ‘folklore’ is envisaged as communal rather than individual, and the text or song is passed on from generation to generation in a ‘state of mental sleep-walking’ as Bronson puts it (1969, p. 73). This type of transmission is the natural and normal process in ‘folk’ or oral literature generally.

There are several strands in this still popular view: the idea of communal origin; of independence of written transmission; of word-for-word reproduction; and of memorisation as the operative factor. These need to be treated separately.

The idea of communal composition has already been questioned in chapter 2; it should also be clear from the account of composition in chapter 3 that—except in a restricted sense—the concept is seldom accurate or helpful. This strand need not be further discussed. The question of the assumed independence of oral from written transmission will be taken up in section 4 on ‘”Oral transmission” and writing’, as will the validity of generalisations about the process of oral transmission, to be discussed at the end of this section. It may be said at once that there are reasons to doubt these assumptions of the romantic approach.

The concept of exact oral tradition from the long distant past is commonly held, implicit rather than explicitly argued, in much popular—and even scholarly—writing about ballads, ‘folksong’ and oral literature. It is sometimes supported by evocative terms like ‘folk memory’ or ‘immemorial tradition’, and by the view of ballads and other instances of ‘folklore’ as survivals or fossils which have come down to us from a distant past rather than instances of a living poetry.

As soon as one looks hard at the notion of exact verbal reproduction over long periods of time, it becomes clear that there is little evidence for it. Even with the Anglo-American ballad quoted earlier, it can be seen that the two texts of Barbara Allen, though close, are not verbally identical. The same goes for the sixteen versions of the ballad recorded in the Appalachian Mountains by Sharp, or the three versions of the ‘traditional words’ printed by Child. It is true that identical versions do exist—particularly when there is a printed copy to which, from time to time, orally transmitted ballads can be referred—and that word-perfect reproduction may often be the ideal held by singers. But, apart perhaps from the Rgveda, instances of identical transmission without the aid of writing over a long period are not easy to find, and it is the variability rather than the verbal identity of orally transmitted pieces that is most commonly noted. There are now few specialists, even among folklorists, who would argue that exact verbal transmission through oral tradition over long periods of time is typical of oral literature. The emphasis now and for some time in the past has been on ‘variants’, the differing verbal forms in which what is in some sense ‘the same’ basic piece or plot is expressed.

If the theory of exact verbal reproduction no longer commands support, that of memorisation as the basic process might still be acceptable. For memory can falter, and it is theoretically possible to account for variants in terms of faulty memorisation and degeneration. The emphasis on memorisation forms one strand of the extreme romantic view; but it also forms the basis of a theory of oral transmission not necessarily tied to other romantic assumptions and demands discussion in these terms also.

The theory goes back a long way, as does the corollary that texts are thus subject to degeneration due to imperfect remembering. Oral transmission is therefore, in this view, predominantly a deteriorating process. One influential statement of this theory—applied particularly to the British ballad—was in Sir Walter Scott’s introduction to his classic collection, first published in 1802, of Minstrelsy of the Scottish Borders. He points out that recited or written copies of these ballads’ sometimes disagree with each other and comments

Such discrepancies must very frequently occur, whenever poetry is preserved by oral tradition; for the reciter, making it a uniform principle to proceed at all hazards, is very often, when his memory fails him, apt to substitute large portions from some other tale …

Some arrangement was also occasionally necessary to recover the rhyme, which was often, by the ignorance of the reciters, transposed or thrown into the middle of the line. With these freedoms, which were essentially necessary to remove obvious corruptions, and fit the ballads for the press, the editor presents them to the public.

(Scott, 1802, I, pp. cii–ciii)

In his ‘Introductory remarks on popular poetry’, which he added in the 1833 edition, he develops this theory even more clearly

Another cause of the flatness and insipidity, which is the great imperfection of ballad poetry, is to be ascribed less to the compositions in their original state, when rehearsed by their authors, than to the ignorance and errors of the reciters or transcribers, by whom they have been transmitted to us.

The more popular the composition of an ancient poet, or Maker, became, the greater chance there was of its being corrupted; for a poem transmitted through a number of reciters, like a book reprinted in a multitude of editions, incurs the risk of impertinent interpolations from the conceit of one rehearser, unintelligible blunders from the stupidity of another, and omissions equally to be regretted, from the want of memory in a third.

(Scott, ed. Henderson, 1902, I, pp. 9–10)

This theory has remained in circulation ever since, and—as McMillan shows (1964)—has recent adherents. It was widely held at the beginning of this century and was thus summed up by John Robert Moore in 1916:

There are certain factors at work in the mind of the singer to destroy or to sustain his memory of the ballads. In the first place, there is a natural tendency to oblivescence, by which things of a year ago tend to make way for things of the present moment. Again, changes take place in the meaning or pronunciation of words, thereby obscuring the singer’s memory. Similarly, words which lack associative significance are likely to drop out and be replaced by something else, especially in the case of proper names and obsolete words. Lastly, the memory of the singer is weakened by the loss of one accompanying feature of the ballad, as the dance, the tune, or the background of the story, or by the loss of a sympathetic audience or of the custom of singing … The ballad-singers are unable to create anything equal to the songs which they have received…

(Moore, 1916, pp. 387, 389, quoted in McMillan, 1964, p. 301)

The theory of oral transmission as predominantly a degenerative process, with its key factor as memorisation is easy to question. Some of the factors which make memorisation as the central process look implausible have been discussed in chapter 3, in the context of composition. These are the effect on performance of occasion and audience, the creative role of the poet, and the finding of the oral-formulaic school, in Yugoslavia and elsewhere, that composition-in-performance is often involved. The present tendency among ballad scholars is to reject memorisation-with-degeneration-as the sole process at work—and to stress the element of ‘recreation’ in oral transmission discussed below.

Nevertheless, there is something to be said for the memorisation theory and it is over-extreme to reject it out of hand (under the influence of the oral-formulaic school, for instance). There are cases in which memorisation does seem to be one central process involved in transmission. It is obviously likely to play an important part where composer and reciter are not the same person, as with some Somali and early Irish poetry (and other cases mentioned in chapter 3). It also enters in-though over a shorter time span—where a poet memorises the words he had himself created in a process of prior composition, or in joint performances by a number of people.

This comes out particularly clearly in work on Anglo-American ballads. It has been suggested that here is a cultural tradition where, in contrast to Afro-American culture, there is relatively greater emphasis on memorisation and exact reproduction, and less on re-creation and improvisation (Abrahams and Foss, 1964, p. 12). Moreover in any tradition there will be some individuals who are primarily uncreative in verbal terms and, so far as they take part in the transmission of actual texts, tend to pass on forms in much the shape they received them—though perhaps in an imperfect form due to imperfect remembering. Even in the Anglo-American tradition not all singers are of this kind, and it is easy to instance creative and original poets. But in considering the processes of transmission and distribution it would be misleading to focus only on the creative composers, and neglect the more ordinary ‘traditors’.

It is relevant to recall the research on ‘remembering’ carried out over fifty years ago by F. C. Bartlett in his psychological experiments ‘on the reproduction of folk stories’. He discovered that both where individuals after an interval reproduced a story they had been told and where the stories were passed along a chain of participants there were many changes, to such an extent that the original was often drastically altered, or even entirely transformed by the end. Incidents in the story were often changed by being turned into something familiar, and then rationalised to make sense of the new versions where omissions produced in the transmission had made the existing version nonsensical or unfamiliar; or particular words, phrases or events which ‘stood out for the teller’ persisted while other elements dropped out (Bartlett, 1920, reprinted in Dundes, 1965). This process will be recognised by anyone who has played the ‘whispering game’ at parties, where the first in a long line has to whisper a memorised sentence to the next player, and so on down the line. The final sentence is often very far from the initial one—a neat illustration of the changes that can occur in at least one type of oral transmission.

So it is plausible that variants and changes in Anglo-American ballads can be attributed to faulty memory, mishearing or misunderstanding by singers who might otherwise have transmitted the song exactly as they heard it. The church in Lord Lovel, for instance, is often St Pancras, and it is reasonable to suppose that this may have been the original wording: but it also appears as St Pancreas, Pancry, Pancridge, Panthry, Pankers, Patrick, Bankers, Peter, Varney, Vincent, Rebecca, King Patsybells and others (Coffin, 1950, p. 3). Consider also what happened to the (presumably) original refrain ‘Savory (or Parsley), sage, rosemary and thyme’. This has been changed by ballad singers who did not understand or fully learn the refrain to a number of different variants:

Save rosemary and thyme.

Rosemary in time.

Every rose grows merry in time.

Rose de Marian Time.

Rozz marrow and time.

May every rose bloom merry in time.

Let every rose grow merry and fine.

Every leaf grows many a time.

Sing Ivy leaf, Sweet William and thyme.

Every rose grows bonny in time.

Every globe grows merry in time.

Green grows the merry antine.

Whilst every grove rings with a merry antine.

So sav’ry was said, come marry in time.

(cited in Abrahams and Foss, 1968, p. 18)

Other processes of change have been identified by folklorists who have studied memorisation in the oral transmission of the Anglo-American ballad tradition (see especially Abrahams and Foss, 1968); these may well have parallels elsewhere. One is rationalisation: when part of a song is misunderstood or forgotten, the result can be gibberish, and the singer may then try to turn the resultant nonsense into sense, as in the rationalisations of the refrains just mentioned. Again, large portions of an oral poem—as distinct from the smaller verbal elements just mentioned—can be misheard or forgotten, and here it is often what is regarded by particular singers as the ‘emotional core’ of a poem that is remembered, and the rest to some degree forgotten.

While it is, by now, hard to accept memorisation and forgetting as the key factors in oral transmission, the processes just mentioned are obviously important in certain circumstances and it would be misleading to ignore them. Lord’s dictum that oral poetry is never memorised, or Hodgart’s claim that ‘every singer is both a transmitter of tradition and an original composer’ (Hodgart, 1971, p. 14) go beyond the evidence.

But re-creation and re-composition theories now take the foreground in discussions of oral transmission. This approach too dates back some way. In 1904, Kittredge put it clearly in his introduction to the Child ballads

As it [the ballad] passes from singer to singer it is changing unceasingly. Old stanzas are dropped and new ones are added; rhymes are altered; the names of the characters are varied; portions of other ballads work their way in; the catastrophe may be transformed completely. Finally, if the tradition continues for two or three centuries, as it frequently does continue, the whole linguistic complexion of the piece may be so modified with the development of the language in which it is composed, that the original author would not recognize his work if he heard it recited. Taken collectively, these processes of oral tradition amount to a second act of composition, of an inextricably complicated character, in which many persons share (some consciously, others without knowing it), which extends over many generations and much geographical space, and which may be as efficient a cause of the ballad in question as the original creative act of the individual author.

(quoted in McMillan, 1964, p. 302)

Gerould too emphasised that ‘variation cannot possibly be due to lapses of memory only’ (1932, p. 184). He points out that many singers have been unable to resist the impulse to make alterations even though their memories have been extremely accurate…

I see no reason why we may not believe that some of the verbal variants, which we regard as worthy of admiration, may not be the work of persons with an instinct for playing with rhythmic patterns in words, of Miltons who though inglorious have not been content to remain mute. Such an individual would make changes unconsciously because he could not resist the impulse to experiment.

(Gerould, 1932, p. 187)

To emphasise this re-creative aspect is not to suggest creation from nothing. Rather—as in the oral-formulaic approach—there is a stock-in-trade of themes, plots, phrases and stanzas on which the ballad singer (or other poet) can draw, and through which he can impose more—or less—originality on his composition. There are, for example, many stock phrases and episodes which occur and recur throughout the ballads, and seem not to belong to particular ballads but to form a traditional pool at the ballad singer’s disposal. Thus the same refrains appear in a number of different ballads, and as Coffin puts it ‘names, phrases, lines, cliches, whole stanzas and motifs wander from song to song when the dramatic situations are approximately similar’ (Coffin, 1950, p. 5). Fair Ellen or Fair Eleanor can be the heroine of almost any song and Lord Barnard, Barbara (Allen), Sweet William, and Lady Margaret are always coming in as names for ballad characters. Stock phrases and episodes are very widespread. Coffin gives some instances

A person who goes on a journey dresses in red and green or gold and white (see Child 73, 99, 243, and others); a man receiving a letter smiles at the first line and weeps at the next (see Child 58, 65, 84, 208, 209); roses and briars grow from lover’s graves (see Child 7, 73, 74, 75, 76, 84, 85); a person tirls the pin at a door, and no one is so ready as the King, etc. to let him in (see Child 7, 53, 73, 74, 81); a story begins with people playing ball (see Child 20, 49, 81, 95, 155); etc. These and many similar and soon recognizable lines crop up in every part of the country and appear in almost any song with the proper story situations.

Such variations, which have long been noted by ballad scholars, could be explained as devices by which a singer can cover up ‘his lagging memory’ or as deviations from the original authentic form of the ballad—the kind of ‘distortions’ that inevitably occur in a long chain of memorised trans mission. But it is now more common to interpret them in the light of the Parry-Lord approach, according to which there is no one ‘correct’ original; each ballad is created as a unique piece by a process of simultaneous composition/performance. The approach works with the ballads, which clearly have much in common with other oral narratives in their use of stock episodes and phrases (it seems over-precise to call them ‘formulae’): the kind of ’commonplaces’ which, as Jones says in an illuminating article which brings out this aspect, ‘freed [the singer] from the restrictions of memorization’ and enabled him ‘to compose rather than merely transmit’ (Jones, 1961, p. 103). Through these set pieces, the ballad singer can vary and adapt the basic story, can in a sense compose, if he wishes, as well as transmitting. Consider, for instance, the many variants of the first two lines of The Unquiet Grave—one of the ballads accepted as ‘traditional’ in Child’s definitive collection which it is surely reasonable to attribute to individual re-creation rather than merely ‘faulty memory’.

The wind doth blow today, my love,

And a few small drops of rain.

How cold the wind do blow, dear love,

And see the drops of rain.

Cold blows the wind o’er my true-love,

Cold blow the drops of rain.

Cold blows the wind today, sweetheart,

Cold are the drops of rain.

Cauld, cauld blaws the winter night,

Sair beats the heavy rain.

How cold the winds do blow, dear love!

And a few small drops of rain.

Cold blows the winter’s wind, true love,

Cold blow the drops of rain.

(quoted in Gerould, 1932, pp. 171–2)

Again, a common episode in ballads has someone looking over a castle wall and seeing a variety of happenings (according to the needs of the story).

The queen lukit owre the castle-wa,

Beheld baith dale and down,

And ther she saw Young Waters

Cum riding to the town.

The same commonplace is varied to beautiful effect in The Bonny Earl of Murray:

Lang will his lady

Look ower the castle down,

Ere she see the Earl of Murray

Come soundin through the town.

(quoted in Jones, 1961, p. 104)

Stock phrases, lines and topics of this kind abound in British and American ballads. Johnie Scot is recorded in at least twenty versions. Though the basic story (essentially that of a rescue) remains the same, there are many differences—not just of verbal details. In some, only one message is sent for Johnie telling of his sweetheart’s imprisonment, while in other versions there are two messages (one from Johnie calling his love, the other from her explaining why she cannot come). The message incident itself can be extended to as many as ten stanzas in one version, whereas in other versions it takes eight, seven, five or four or even less. Versions having the same number of stanzas do not necessarily treat the incident in the same way. Here are three variants:

O Johnie’s called his waiting man,

His name was Germanie:

‘O thou must to fair England go,

Bring me that fair ladie.’

He rode till he came to Earl Percy’s gate,

He tirled at the pin;

‘O who is there?’ said the proud porter,

‘But I daurna let thee in.’

So he rode up and he rode down,

Till he rode it round about,

Then he saw her at a wee window,

Where she was looking out.

‘O thou must go to Johnnie Scot,

Unto the woods so green,

In token of thy silken shirt,

Thine own hand sewed the seam.’

Version E used only two stanzas:

‘Odo you see yon castle, boy,

It’s walled round about;

There you will spye a fair ladye,

In the window looking out.’

‘Here is a silken sark, lady,

Thine own hand sewed the sleeve,

And thou must go to yon green wood

To Johnie, thy true-love.’

Finally, and perhaps not least effectively, Version J used only a stanza and a half:

(The lady was laid in cold prison,

By the king, a grievous man;)

And up and starts a little boy,

Upon her window stane.

Says, ‘Here’s a silken shift, ladye,

Your own hand sewed the sleeve,

And ye maun gang to yon green-wood,

And of your friends speir na leave.’

(Jones, 1961, pp. 109–10)

Variation in ballads can extend beyond this kind of verbal change and affect the characters and scene of the story. Local heroes or settings are often introduced in ballads. Thus the ballad better known as Lord Randal becomes one about Johnnie Randolph in Virginia where the illustrious Randolph family lived; in a cowboy version of Barbara Allen the scene shifts to the prairie, while the same ballad in a New York village makes Barbara a poor blacksmith’s daughter and her lover the richest man in the world (Coffin, 1950, p. 3).

The changes sometimes affect the basic plot. One version of Barbara Allen was circulating in the Smoky Mountains earlier this century in which the lover recovers instead of dying, and curses Barbara Allen; she dies, and he dances on her grave. This version was composed by a local singer, fiddler and ballad-maker, John Snead. He reworked the ballad and gave it a different ending because, as he said, ‘that dratted girl was so mean’. His version caught on locally, and started circulating as a ballad in its own right, and preferred to versions based on the more common story (Leach, 1957, p. 206).

Again the ‘traditional’ framework of the well-known story in Gypsie Laddie in which a noble lady leaves her comfortable life to flee with her Roma lover, became in a West Virginia version a tale set in a local context and with local names, about ‘Billy Harman whose wife had gone off with Tim Wallace, Harman’s brother-in-law. Wallace was very ugly and the wife very pretty. She never came back; he did’ (Coffin, 1950, p. 12). The result is a ballad in which some episodes included in other versions are left out—the meeting with the elopers, and the scorning of the husband—but one which presents its own self-sufficient story.

The older models of transmission in terms of exact reproduction or (fallible) memorisation cannot easily account for this extent of variation—and certainly not for deliberate changes like John Snead’s reworking of Barbara Allen. The most recent trend in ballad scholarship is to interpret this variability as one instance of the potentialities of any oral poetry—the possibility that it will be changed in the course of performance (see e.g. Jones, 1961; Buchan, 1972; Hodgart, 1971).

Fig. 5.2. An illustration of Barbara Allen visiting her dying suitor, printed circa 1760, from Barbara Allen’s Cruelty or The young Man’s Tragedy (author unknown). Wikimedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbara_Allen_(song)#/media/File:Barbara_Allen’s_cruelty;_or,_the_young_man’s_tragedy._To_the_tune_of_Barbara_Allen._Fleuron_N015486-1.png

This new view of variation in ballads is explicitly based on the findings of Lord and Parry and the ‘oral-formulaic school’, so the emphasis is very much on the concept of ‘composition’ rather than on ‘transmission’. As was argued in chapter 3, the extreme and exclusive version of the Parry-Lord theory is questionable and we cannot accept entirely Hodgart’s comprehensive claim that ‘no two versions of a ballad are ever exactly alike; and every singer is both a transmitter of tradition and an original composer’ (Hodgart, 1971, p. 14). But the oral-formulaic theory brings some insights. It does now seem clear that ballads must be understood as sometimes subject to the same range of influences towards change due to the individual personalities of singers, local events, the creative impulse stirred by the performance itself and the nature and circumstances of the audience. Bringing the analysis of ballads into touch with comparative work on oral poetry elsewhere suggests that, as far as transmission goes, ballads are not a special category but are subject to the same blend of memorisation and (possibly more frequently) of variability in performance that one would expect from studies of the composition and transmission of oral poems generally.

Most of this discussion has concentrated on the British and American ballad, where the best case for long oral transmission based on memorisation and/or the force of inert tradition has often seemed to be found (apart from the Rgveda). But similar analyses can be made of other cases that might seem to lend support to the romantic view. The Gésar epic, for instance, circulating so widely in Tibet, China and Mongolia, is not confined to a static and exact text, for

la création poétique est continue du seul fait du caractère médiumique du barde. Elle respecte toujours le cadre donné, mais peut, en improvisant, le déborder ou le crever à l’occasion. L’épopeé est une oeuvre vivante qui s’enrichit encore, ou s’est encore enrichi tout récemment, de nouveaux chapitres, sans parler des variations dues à l’omission ou à l’addition de thèmes et récits par des conteurs plus ou moins informés.

(Stein, 1959, p. 586)

Here, as with similar cases, the overall structure of incidents as well as certain conventions of phrasing recur again and again; but transmission of the poems in the form of finished oral art—as literature—has to take into account other factors besides the passive handing on of some ‘oral tradition’. The creative role of whole series of individual poets and performers has also to be remembered.

This applies even in an instance where one would expect little creative adaptation and which is sometimes cited as a good example of long-lasting ‘oral tradition’—nursery rhymes and children’s verse. Of course, memorisation and more or less exact transmission are sometimes involved, and some basic forms and motifs are known to have a long history. But this does not rule out variability; this is clear from a large number of examples which are difficult to explain in terms of ‘faulty memorisation’. Here for instance are a few of the Irish versions of what many of us know as ‘How many miles to Babylon?’

County Louth version

How many miles to Babylon?

Three score and ten.

Can I get there by candle-light?

There and back again.

Here’s my black (raising one foot),

And here’s my blue (raising the other),

Open the gates and let me through.

Belfast version

How many miles to Barney Bridge?

Threescore and ten.

Will I be there by candle-light?

Yes, if your legs are long.

If you please will you let the king’s horses through

Yes, but take care of the hindmost one.

Dublin version

How many miles to Barney Bridge?

Threescore and ten.

Will I be there by Candlemas?

Yes, and back again.

A courtesy to you, another to you,

And pray fair maids, will you let us through?

Thro’ and thro’ you shall go for the king’s sake,

But take care the last man does not meet a mistake.

(Marshall, 1931, p. 10)

Besides Babylon and Barney Bridge, other places that appear are Bethlehem, Aberdeagie, Burslem, Curriglass, Gandigo, Hebron and Wimbledon (Opie 1955, p. 64). A large number of variants on other well-known rhymes can be found in the Opies’ well-documented Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes.

So even in the apparently tradition-bound sphere of children’s verse, creation and re-creation is to be found. Add to this all the other examples of re-creation and re-composition in performance pointed out by scholars all over the world, above all by those inspired by the researches of Milman Parry and Albert Lord: the overall picture that emerges is that though themes and forms persist, and though transmission by exact memorisation does sometimes occur, to describe the transmission of oral poetry in terms only of exact and inert oral tradition is incorrect.

There remains the difficult case of the Rgveda. It has been claimed by generations of Indian scholars that its transmission over centuries and millennia has been essentially due to exact memorisation. This is a strong claim and, if justified, would provide an unparalleled instance of the exact oral transmission of an extremely long text—around 40,000 lines in all—over an enormous expanse of time. The religious and liturgical context of the text lends some support to this interpretation, for this is the kind of circumstance that puts a premium on exact rendition. In addition, it seems that in Indian tradition, in contrast to that of the west, writing was held in low regard—even regarded in some respects as impure—and ‘extra ordinary importance accorded to memory’ (Staal, 1961, p. 15). Staal explains the process of Vedic transmission and its underlying idea that the words, which are one with the meaning and themselves sacred, should be preserved for the world and for posterity.

In this sense the ṡrotriya who recites without understanding should not be compared with a clergyman preaching from the pulpit, but rather with a medieval monk copying and illuminating manuscripts, and to some extent with all those who are connected with book production in modern society. To the copyists we owe nearly all our knowledge of Antiquity, to the reciters all our knowledge of the Vedas.

(Staal, 1961, p. 17)

Accuracy was not just ensured by the strict training and supervision of reciters, but enjoined as a religious duty: by reciting the sacred Vedic literature correctly, man contributed to the divine plan. The whole background of religious belief and training, therefore, served to uphold the accuracy of memorised oral tradition.

Certain doubts occur, however. First, can we in any case be certain about this exact transmission over many centuries of time? There is no external written evidence about the exact form and content of the Rgveda in, say, 1000 or even 500 B.C. (and, if there were written versions within the tradition, how could one be sure that writing did not play some part in the process of transmission?); and the ‘archaic’ nature of the language, sometimes cited, cannot be regarded as definitive evidence of the original date of final composition or of the text’s having remained unchanged in all respects over the centuries (on this see also chapter 4, section 4). The essential contention about the Rgveda is that it was directly inspired: with some later works it is collectively known as śrti or ‘heard’, because it is deemed to have been divinely dictated. For someone working within this culture, this must seem as solid a piece of evidence for the lengthy and exact transmission of Vedic literature as belief in the Bible as ‘The Word of God’ did to Biblical scholars suspicious of the higher criticism of Biblical texts. Statements by priests or poets (or even by their foreign admirers) about the long tradition which lies behind their words cannot—as sociologists know only too well—always be taken at their face value, and further evidence always needs to be sought. Long and unchanging oral transmission over the centuries used to be claimed for all traditional Indian literature, but it is now apparently accepted that this does not necessarily apply to some of the ‘later’ less sacred pieces. It is possible that a similar re-thinking of the evidence may take place in the case of the Rgveda also. There is also the possibility (discussed later) that writing may have played a larger part than is sometimes recognised in the process of Vedic transmission. The overall conclusion must be that, while the evidence seems to point to a remarkable degree of exact oral transmission of a very lengthy text over a long period of time, the argument is not closed and further detailed examination of this case might prove illuminating.

One is forced to the conclusion that there is, after all, no single process of ’oral transmission’—no universal ’laws’—applicable to all oral poetry (or all oral literature). Rather, a number of different elements may be in play: exact verbal transmission (as, apparently, with the Rgveda and perhaps with other religiously sanctioned texts like the cosmological poetry of Hawaii); memorisation (often fallible) as with a number of versions of Anglo-American ballads, popular hymns, some Zulu and Ruanda panegyrics and so on; and several variants on the themes of re-creation, re-composition, or original composition-in-performance on the oral-formulaic model. In any one case, different elements among these, or different combinations of them, may be in play in a way that cannot be predicted simply from the nature of the piece concerned.

It is impossible, therefore, to predict in a given instance what the detailed form of oral transmission is likely to be. The earlier hope that, by further study of oral transmission and careful checking of results we may ‘eventually arrive at a generally acceptable theory’ (McMillan, 1964, p. 309) must be abandoned. There are too many variables involved—not only the different elements so far as memorisation is concerned, but also the variations attaching to differing cultural traditions, different poetic genres, changing historical circumstances, the specific occasions of delivery and the differing personalities of poets and ‘transmitters’ themselves. We can no longer assume that generalised theories about oral transmission universally apply: that it is always through inert tradition; or always through memorisation, faulty or otherwise; or, as in some recent claims, always composition-in-performance. The truth is more unromantic. This is that despite the clear evidence of the widespread distribution of certain themes, plots and forms, the means by which they are actually worked out as literature and distributed orally to their audiences has to be discovered by detailed and painstaking research rather than assumed in advance on the basis of generalised models based on earlier theories.

I have spent so much space on this question whether exact oral tradition over long periods is the normal process for the transmission of oral poetry because romantic views about ‘oral tradition’ are still so prevalent, both in popular understanding and even in many assumptions by scholarly researchers working in related areas; and the idea that there is one proven mode of ‘oral transmission’ is at first sight so attractive and plausible. Until these ideas are challenged, it is difficult to make a dispassionate appraisal of what is known of the differing ways in which oral poems are transmitted and distributed to their audiences.

The purpose of this discussion has thus been largely negative: to raise questions about assumptions sometimes taken for granted. But it has also emphasised certain more positive points. First, so far from there being one ‘normal’ means for the transmission of oral poems, there are in fact a number of different ways in which this can take place, depending among other things on historical circumstance, the poet, the performer, the audience and the type of poem. Secondly, even when themes and basic forms are very stable, verbal variability and originality in oral performance are extremely common, and almost certainly more typical than unchanging transmission, even though the extent of memorisation as against originality cannot be predicted in advance from some universal theory. And third, questions of transmission very quickly lead into the discussion of composition and creativity—the two aspects are so closely linked that in this discussion of transmission it has proved impossible not to recur constantly to points previously considered under the head of ‘composition’.

These points are reinforced if we turn to a more detailed discussion of some ways in which oral poems can be distributed and thus reach their audiences.

5.3 How do oral poems reach their audiences?

Some of the means of diffusion have already been touched on in the discussion of ballads. Emigrants sometimes take their songs with them when they travel and sing them with varying degrees of adaptation and new composition in the countries to which they go—as happened with British ballads in America or Australia, or perhaps with African songs brought by slaves to the American South and to the West Indies. Or they are transmitted along trade-routes, like those between Scotland and Scandinavia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, areas whose ballads show close resemblance. Detailed studies of this type of historical diffusion have been carried out by theorists of the historical-geographical school, like Archie Taylor’s tracing of the ballad Edward from its British source to its wide spread occurrence in Scandinavia (Taylor, 1931). In other cases, the transmission is within a single culture; when this is over a protracted period it is often backed by religious authority, as with the transmission of liturgical forms (like the Credo or Magnificat) within Western Christianity or the Rgveda in India. When there are strong religious sanctions on continuity there is less likelihood of variation (though it is not impossible) and diffusion is often relatively straightforward, largely through memorisation reinforced by frequent reiteration in formalised situations (and not in frequently by writing). In other cases, there is not the same sanction on continuity, and how far transmission becomes an aspect of composition is not predictable in advance: it depends on a range of factors like the occasions on which the pieces are delivered, the personality of the performer/poet, the function(s) of the oral poem in question, and the range of variation accepted within a given community.

It is more illuminating to turn from the often speculative studies of lengthy transmission so beloved by romantic theorists and scholars of the historical-geographical school, to consider the more detailed ways in which oral poems are distributed through space, as it were, and on a much shorter time-scale. Basically this comes down to a consideration of the occasions on which poems are delivered to audiences and thus realised as oral literature.

The simplest case is presented by poetry performed communally—by a group singing for themselves rather than for an audience. Work songs are typical. In so far as these songs are relatively unchanging, within short periods at least, the singers learn them through being members of the group, and reinforce their knowledge by singing them. This applies to other songs mainly performed through choral singing—songs like The people’s flag, God save the Queen or well-known hymns in own culture, the secret society songs ritually sung by initiates in West African groups like the Limba, jointly sung children’s songs, Irish pub songs, or Aranda dance songs in Central Australia. In these cases the emphasis tends to be on memorisation, and transmission is at the face-to-face level within the group. Changes in group membership, with individuals taking knowledge of particular songs with them and, if accepted, teaching them in new groups can lead to such songs having quite a wide distribution at times. Though the tendency in these cases of group singing is towards memorisation rather than individual originality, this is not always rigidly the case, and new compositions do arise—it is obvious they must do, since the songs have to have a beginning somewhere.

It is probably more common, however, with work songs (and many other group songs) for the whole group not to sing all the song but for there to be solo lines or stanzas for a leader. Here the opportunities for individual composition can be extensive—depending on the context and form. The kind of creativity illustrated in Jackson’s account of originality in work songs among Black prisoners in Texas has been widely documented elsewhere. He shows how the lead-singer uses many phrases and partial lines from traditional prison songs, but by this means can compose his own personal verses. Sometimes this involves little more than ‘slotting-in’ appropriate names into formulaic lines or re-assembling new songs from accepted phrases, but others can use even the prison work song context to produce highly creative work: ‘They sing not only well-known lines and stanzas, but they add many of their own or vary the existing ones. J. B. Smith is such a song leader … Working within a traditional framework and using some traditional elements, he has woven an elaborate construct of images’ (Jackson, 1972, pp. 34, 144). Thus even in the largely choral songs—and so at the simplest level of the work song—it is hard to keep questions about transmission and distribution wholly separate from composition.

Fig. 5.3. The Limba musician Karanke Dema leads a chorus of singing farm workers in northern Sierra Leone. Photo by Ruth Finnegan, 1961.

This is even more clear when we move to the other extreme: the distribution of oral poems by a highly specialised poet delivering his compositions as a special performance to a gathering of admirers. This type of occasion is widely documented throughout the world from the Kirghiz and Kazakh epic minstrels of the Soviet Union or the Yugoslav guslari to the Zulu praise poets, Irish ballad singers or Fijian heroic poets. The picture we are given in The Odyssey of the rhapsodist’s performance is very similar, and many have speculated that Homer himself—whoever he was—used to perform to groups of listeners in much the same way. A common pattern here is for the poet to engage in the kind of simultaneous performance and composition analysed by Radlov, Parry and Lord. So, although in a sense transmission is involved, in that the poet may be working with known themes and plots and composing within a traditionally accepted system of conventional patterns of various kinds, the composition and performance of a uniquely shaped piece meeting the requirements of a specific occasion, audience and performer’s personality are really more in question than ‘transmission’ of an already existing piece. Insofar as performance of this kind involves the unique realisation of a particular oral poem, the term ‘publication’ is here better than ‘transmission’ or even ‘distribution’.

Not all public recitations by specialist poets follow this model of blended composition and performance. There is also the opposite case—with shades of difference in between—when the composition takes place separately from the performance, and may even be by a different person from the reciter who merely learns and delivers it. Examples of this type of transmission were described briefly in chapter 3. Here it does make sense to speak of ‘transmission’. Not much detailed research documents the process by which poetry is transmitted in this way. But at times, this method of transmission can result in remarkably widespread and rapid distribution of poems once composed. In Somalia, for instance, partly owing to traditional nomadic patterns of movement, poems ‘spread very quickly over wide areas’ (Andrzejewski and Lewis, 1964, p. 45), and this is nowadays accelerated by modern means like trains or lorries, for the singers and teachers of such songs still sometimes travel throughout the country, as wandering minstrels did at a slower pace in the past. The radio is also becoming an increasingly frequent medium for this type of distribution.

Electronic transmission is no abnormal or odd context for oral poetry; indeed radio is becoming extremely important both in industrial and (perhaps even more) in developing countries as a vehicle for oral poetry. We hear of classical and contemporary oral poetry being broadcast over Somali radio, of the Mandinka ‘Sunjata epic’ being transmitted over both Radio Dakar and Radio Gambia, religious lyrics being broadcast by Radio Ghana, or mvet songs by Yaoundé radio; and of course ‘folk ballads’ and ‘folk poetry’ as well as pop songs are now widely propagated in western industrial society by radio and television. Thus by means of face-to-face recitations by travelling minstrels and poets, and by mass broadcasts to wider audiences, poems that have been—more or less—formed by prior composition can be transmitted widely to various audiences by the poet himself or by reciters who have learnt the text from the composer or other performers.

Sometimes the performance of a poem following prior composition by the poet takes the form of a carefully-rehearsed set-piece concert, rather than frequent recitations by performers throughout a wide area on what could be dubbed the Somali model. One example of this is the performance that sometimes follows after the long process of careful composition by the Gilbertese poet described in chapter 3. After the song has been composed the poet, Grimble tells us, then teaches it to those who will perform it, a group as much as two hundred strong. They learn the words ‘phrase by phrase’ and develop the dance to go with it. The rehearsals are elaborate and protracted affairs:

As each passage becomes known, the experts sketch out the appropriate attitudes, which are tried and retried until satisfaction is reached. There are interminable repetitions, recapitulations, re visions, until the flesh is weary and the chant is sickeningly familiar. But from a ragged performance of ill-timed voices and uncertain attitudes, the song-dance becomes a magnificent harmony of bodies, eyes and arms swinging and undulating in perfect attunement through a thousand poises, to the organ tone of ten score voices chanting in perfect rhythm. Then dawns the poet’s day of glory.

Clearly the music and dance play a significant part in such performances, and so long rehearsals are necessary for their effective rendering—but this does not make the performance any less significant as the occasion when the poet’s verbal composition is delivered, in the setting locally accepted as suitable, to the local audience: it is indeed ‘the poet’s day of glory’. Grimble does not record how frequently performances like this took place or how often the same poem was delivered in this way—but it seems reasonable to guess that such a large scale event was not repeated with great frequency, even if the poem was also sung informally in more personal contexts.

This type of carefully-rehearsed performance is not unique to the Gilbert Islands. The Chopi of southern Africa spend long periods working at the joint music and words which make up the nine-to eleven-movement orchestral ŋgodo dance which certain skilled and known musicians compose anew about once every two years (Tracey, 1948, pp. 2ff), and a number of other deliberately rehearsed occasions are recorded for the performance of oral literature in Africa (Finnegan, 1970, pp. 103–4, 269f). And of course rehearsals of ‘jazz poetry’ in Western Europe, or of dramatic performances in many parts of the world rest on similar long preparation and the co-operation of numbers of people, and result not in multiple distribution of the poetry involved but, more often, in just a few performances (for with oral as distinct from written literature, later revivals after a protracted period are unlikely). The exceptions are when there are groups of professional or semi-professional players who either command a sufficiently large and varied public to give a series of repeated performances or (more likely except in highly populated urban areas) travel the country in a troupe performing known pieces from their repertoire—like the travelling Malay story-tellers, and perhaps the strolling players of mediaeval Europe. Thus repeated distribution to changing audiences can take place. Cases such as these, as well as the long-rehearsed Gilbertese performances, show how wide of the mark are older assumptions about some uniform and ‘natural’ form of distribution of oral literature.

Enough has been said to illustrate the basic contention of much of this chapter—that oral poetry is not distributed and transmitted by a single means that can be automatically assumed in advance of tile evidence, but takes place in different ways. Some other processes of distribution should be mentioned briefly before I move on to oral/written interaction and how this enters into the distribution process.

In one common situation topical and ephemeral poems, usually short, ‘catch on’ in a community and pass from mouth to mouth, often in an incredibly short time, to become widely popular (or popular within a particular group of people) and then, often, to be forgotten again. This phenomenon is well known with ‘pop’ songs in the west (where word of-mouth transmission is supplemented though not replaced by broadcast media, records and tape) but it also occurs widely in less industrialised contexts—among the Ibo and Tiv of Nigeria for instance (Finnegan, 1970, pp. 266, 279–80). This sort of transmission is often informal and perhaps ultimately depends on face-to-face and unorganised contact (despite the commercial backing given to it in some western contexts).

There is also the not uncommon situation where oral poems are delivered in the context of a public duel or competition. Inuit taunting songs are famous examples of this, when two hostile singers work off grudges and disputes through both traditional and specially composed songs which ridicule their opponents. The winner is the singer most loudly applauded (Hoebel, 1972, pp. 93ff). In this case the distribution to listeners depends on formally organised occasions when these songs—whether previously prepared or not—are delivered.

The same goes for the widely held poetic competitions where the emphasis is (in varying degrees) on display and poetic accomplishment rather than on resolving or maintaining hostilities. Organised competitions by poets used to be held in several areas of East Africa. In Tanzania, for instance, two singers, each with his own supporting group, sometimes decided to compete on an agreed day. They taught their followers new songs of their own composition and on the day the competition was won by the group which drew the greatest number of spectators. On other occasions the local Sultan arranged the competition and acted as umpire between the two sides, each of whom tried to find out their opponents’ songs in advance so as to prepare suitably insulting and sarcastic replies (Finnegan, 1970, p. 103). Similar song competitions were widespread among Polynesian poets (Chadwicks, III, 1940, pp. 415, 462) and Russian poets like the Kazakh and Kirghiz (Chadwick and Zhirmunsky, 1969, p. 329). Japanese court poetry too was often ‘published’ at poetry matches (utaawase). These were at first informal and purely for entertainment, but were later conducted according to very formalised rules and even developed into the special form of a ‘poetry match with oneself’ (jikaawase) in which ‘the poet took two roles and played a kind of poetic chess with himself, sending the results to a distinguished judge for comment’ (Miner, 1968, p. 31). Poetry competitions and duels thus provide yet another organised mode through which the process of publication and distribution of oral poetry can take place.

Another pattern worth notice is that which can result from the exertion of political authority. It may seem odd to single out political and propaganda songs for special mention here since any poem can have a political flavour and the most propaganda-oriented song can, in turn, give enjoyable or humorous effects far beyond the originators’ intentions. But any consideration of how poems are distributed must involve specific mention of situations where the main role in such distribution is not, as it were, played by commercial motives or the attraction of aesthetic and recreational appeal but is deliberately organised by political authorities for their own purposes.

The radio is a much used vehicle by governments with largely illiterate populations, and one medium is oral poetry—such as the songs used in the Indian government’s birth control campaign, or the patriotic songs broadcast by Arab radio stations during the 1973 Middle East War. On a less public but equally effective level are the poets and reciters encouraged by government or political parties to give performances of poetry designed to put their own case—the various singers, for instance, hired by opposing political parties in the Western Nigerian elections in the 1960s, or the Tanzanian government’s appeal to musicians in 1967 to help propagate its new policies of socialism in their songs (Finnegan, 1970, chapter 10), or the aqyn bard in Kazakhstan who travels the country to laud the new Soviet leaders and their policies (Winner, 1958, pp. 157ff). Enthusiastic supporters of particular groups or policies may make it their business to see that their view is well represented in song. One instance was the campaign of the local R.D.A. (Rassemblement Démocratique Africain) against the French government in Guinea in 1954–5. The campaign was greatly assisted by songs in praise of the R.D.A.’s symbol (the elephant) and its leader Sékou Touré. The final success of the R.D.A. was partly due to this effective propaganda, unwittingly aided by the French administration who tried to disperse the apparent agitators (‘the vagrants’) and send them home.

They were piled into trucks, and sent back to the villages. R.D.A. militants tell of their delight at these free rides. The overloaded open trucks carried many R.D.A. supporters on impromptu propaganda tours. This is what they chanted on their trip:

They say that the elephant does not exist.

But here is the elephant,

The elephant no one can beat.

(Schachter, 1958, p. 675)

Many parallels can be found in the industrialised west, such as Irish ‘rebel’ and IRA songs, or left wing ‘protest’ songs. The various types of praise poems of local rulers may not be subject to quite such deliberate distribution among the people, but in highly organised states like, say, the Muslim states of West Africa or Polynesian kingdoms of the Pacific, it is hard not to believe that the performance and reception of these panegyrics were not actively encouraged by those in authority.

The various means of distribution mentioned here have been put forward in the most schematic way. Obviously each of the contexts mentioned has possible variations which shade into each other. And there are specific forms of distribution that could not be covered in a quick survey like this, though they share aspects with the types mentioned—forms of performance like the Ibo taunting songs sung outside a victim’s hut, cowboy songs around a camp fire, or a lover’s solitary serenade to his beloved. There are also cases where ‘transmission’ and ‘distribution’ are not involved, but rather there is a unique performance of a particular oral poem by an individual poet. But enough has been said to show the wide variety of ways in which oral poems reach their audiences and are (on occasion) transmitted over space or time.

Awareness of these many possibilities makes one realise how many questions are opened up by considering not only the traditional problem about ‘transmission’ over long periods of time, but also the more general topic of the manifold ways in which oral poems are distributed and ‘published’. The romantic theory turns out to be not only mistaken in its assumptions that there is a single mode of transmission for oral poetry, but also to be unfruitful in that concentrating primarily on one mode of transmission draws attention away from other equally interesting possibilities.

5.4 ‘Oral transmission’ and writing

One difficulty about the romantic view was mentioned earlier, and must be considered further. This is the assumption that lengthy transmission of oral poetry such as the Gésar or Gilgamesh epics, the Rgveda or—the case par excellence—Anglo-American ballads is likely to have taken place by some pure ‘oral tradition’ untouched by influence from written and printed sources. Allied to this, one sometimes finds the view that writing is incompatible with, or even destructive of, oral literature. Carpenter in his study of the Homeric epics is categorical that writing kills oral literature, for ‘the spread of literacy has remorselessly been destroying the oral literary forms and only the lowest cultural levels preserve their preliterate traditions’ (Carpenter, 1958, p. 3). Evidence for this is suggested in statements like that of the old woman who was the source for several of the ballads in Sir Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border: ‘There war never ane o’ ma sangs prentit till ye prentit them yoursel’, an’ ye hae spoilt them awthegither. They were made for singing an’ no for reading; but ye hae broken the charm now, an’ they’ll never be sung mair’ (Hogg, 1834, p. 61). Lord too sees the ‘oral’ and the ‘literary’ techniques as ‘contradictory and mutually exclusive’ and holds that once the idea of a set ‘correct’ text arrived ‘the death knell of the oral process had been sounded’ (Lord, 1968a, pp. 129, 137).

Detailed evidence tells strongly against both facets of this general view. In practice, interaction between oral and written forms is extremely common, and the idea that the use of writing automatically deals a death blow to oral literary forms has nothing to support it.

The following section gives brief instances of this claim. These instances also fill out the sketch already given of the distribution and publication of oral poetry—for, the reader will already have gathered, writing sometimes plays a part in this process even in largely oral literature.

Fig. 5.4. Ancient Rigveda manuscript, Mandala 1, Hymn 1 (Sukta 1), lines 1.1.1 to 1.1.9 (Sanskrit, Devanagari script). The Rigveda, too, circulates in the written as well as spoken medium. Wikimedia, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Rigveda#/media/File:1500-1200_BCE_Rigveda,_manuscript_page_sample_i,_Mandala_1,_Hymn_1_(Sukta_1),_Adhyaya_1,_lines_1.1.1_to_1.1.9,_Sanskrit,_Devanagari.jpg

The essential point in this context is that writing has been in existence for a longer period and over a wider area of the world than is often realised. The image of the non-literate, untouched and remote ‘primitive society’ goes so deep in western thinking over the last few centuries that it is easy to think that it was only in certain favoured areas of, say, western civilisation that writing has for long played a significant part in society; and that elsewhere (with perhaps some slight recognition of certain achievements in the Far East) writing has been introduced recently as a foreign innovation brought by western penetration. This is seriously misleading. It is true that many groups in Africa, Australia or the Pacific were almost entirely illiterate for many years (and the overall adult illiteracy rate for the world as a whole is reckoned by UNESCO as still around thirty per cent) and that for some cultures their first serious contact with reading and writing was through Christian missionaries and later through colonial administrators. But it is not true that most of the ‘developing’ world had no contact with writing until two or three generations ago? As Jack Goody sums it up

At least during the past 2,000 years, the vast majority of the peoples of the world (most of Eurasia and much of Africa) have lived … in cultures which were influenced in some degree by the circulation of the written word, by the presence of groups or individuals who could read or write … It is clear that even if one’s attention is centered only upon village life, there are large areas of the world where the fact of writing and existence of the book has to be taken into account, even in discussing ‘traditional’ societies.

Writing is not an abnormal or oddly ‘extraneous’ phenomenon even in a society whose main channels of communication may be oral, and which is characterised by the development of oral rather than written literature. One would expect, in fact, that in many such societies written forms would, from time to time, be used in the process of transmitting, composing or memorising forms of oral literature. This indeed is precisely what one finds.

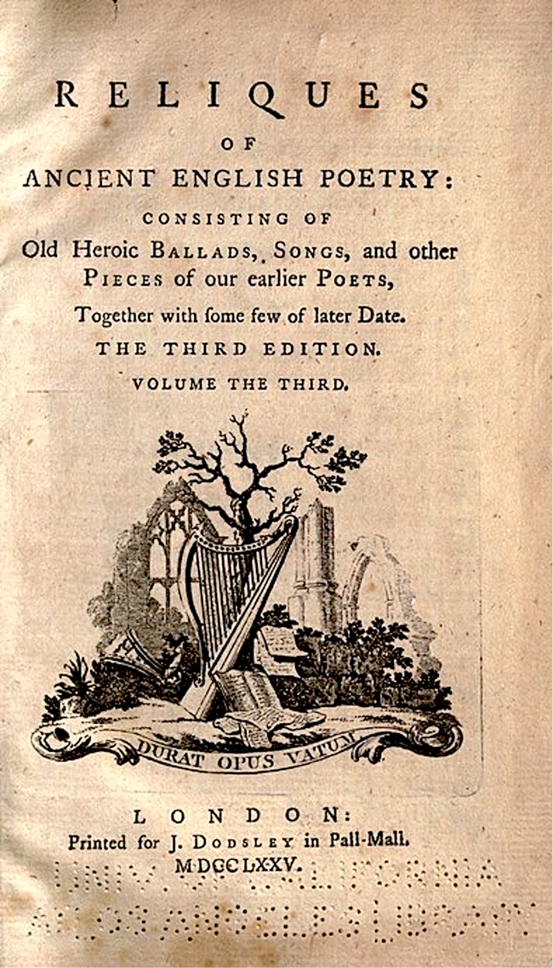

Fig. 5.5. Title page of the third edition of Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry (1775). Wikimedia, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Reliques_of_Ancient_English_Poetry#/media/File:Relicsofanciente03perciala_0007.jpg

Take, first, the British and American ballads. It is clear that there was and is constant interaction between written and oral forms. A distinction used to be made between ‘traditional’ ballads (like Lord Randal or The Elfin Knight) which were taken to have originated and been transmitted orally as far back as mediaeval times, and the later ‘broadside’ or ‘street’ ballads which specifically began in printed form, but then sometimes became accepted into the ‘oral tradition’. Though there is some truth in this distinction, a clear differentiation in terms of mode of transmission does not hold up. Many ‘traditional’ ballads have much in common with earlier literary romances and lais (e.g. Hind Horn from the Horn cycle of romances, Thomas Rymer directly from a fifteenth-century poem about Thomas of Erceldoune, King Orfeo a reworking of the Middle English lai Sir Orfeo) and have themselves inspired later literary poems, particularly by romantic poets. Similarly many street ballads have connections with ‘traditional songs’, for one way in which ballad printers acquired material for their texts was to send their agents into the country to collect the words of songs being sung there. In turn, some literary poems are based on earlier street ballads—Campbell’s Ye mariners of England, for instance, is clearly inspired by Martin Parker’s seventeenth-century street ballad Saylors for my money (see Pinto and Rodway, 1965, pp. 19 and 221ff).

Another apparent distinction—between street ballads and ‘proper’ literature—cannot be pressed very far either, for there was continual interchange between the two from the sixteenth century. A number of well-known English poets are known to have written ‘street ballads’. Marlowe’s Come live with me and Raleigh’s reply, for instance, were printed together anonymously on a single broadsheet. Again, in the corpus of poetry attributed to or deriving from Burns, it is almost impossible to draw a clear line between what is oral and what written: some poems perhaps originated from popular poetry crystallised and written down by Burns, others were perhaps originally conceived by him but now circulate orally in various renderings. Here and elsewhere clear-cut distinctions in terms of transmission cannot be applied.

The ‘broadside’ ballads are a particularly instructive instance of the interaction in distribution between written and oral modes. In England around the early sixteenth century, ballads were distributed in broadside form: at first on single large unfolded sheets of paper in ‘black letter’ (or gothic) type, later in various formats, including the ‘chapbooks’ (or pamphlets of 8–16 pages) and the small collections of songs or ballads known as ‘garlands’. They were designed for wide distribution and cheap sale, and printed in very large numbers. A nineteenth-century ballad about a particularly sensational murder ran to 250,000 copies (Laws, 1957, p. 39). Several hundred ballad printers are known to have practised throughout the British Isles (in the first ten years of Elizabeth’s reign alone, at least forty publishers of ballads are mentioned in the incomplete records of the Stationers’ Company) and all in all ‘ballads were printed and circulated in enormous numbers’ (Rollins, 1919, pp. 258–9).

The main way in which these broadside ballads reached their public was by ballad singers going around the towns or countryside singing samples of their wares, and trying to sell broadside sheets. They were a familiar sight at fairs and markets, and broadsides were among the common stock carried by pedlars throughout the country. In the cities, ballads were sold both by street singers and in small shops and stalls. The initial distribution and publication was thus a mixture of print and performance, with the ballad singer actually performing samples of his ballads to entice people to purchase them. After that, it seems clear that the ballads often circulated orally, with people singing the currently popular ones, or adopting and adapting their own favourites—so that many ballads which started as printed broadside texts then circulated largely through oral means, subject to the variability and re-composition so common in oral literature. This oral transmission in turn sometimes mingled with written distribution, for there is no reason to suppose that popular singers eschewed all contact with the printed versions of their songs, and it is known that singers sometimes wrote down words in manuscript ballad books to assist them (Laws, 1957, p. 44).