6. Poets and their positions

©2025 Ruth Finnegan, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0428.06

In any consideration of oral poetry, one obvious question is: who are the poets? Who composes and performs oral poetry? The quick answer is that it can be almost anyone. An immense variety of people are, and are expected to be, poets in different groups and societies. Despite some confident pronouncements on the subject, there seems no one predictable pattern in type of personality, relationship of the poet to his society, or the economic and social rewards of poetry. The role of poet is occupied and envisaged in a variety of ways—from the official court poets of kingdoms in mediaeval Europe or Asia or recent West Africa, to a Malay or Inuit shaman, or an American preacher claiming poetic inspiration from the spirit, or the unpaid lead singer in a working group of canoeists or agricultural workers or prisoners. And yet the position of the makers of oral poetry is neither random nor totally unpredictable. There are recurring patterns found in widely separated parts of the world; and the opportunities and duties of the oral, as of the literate, poet are regulated by social conventions and coordinated with the social and economic institutions of his society.

It may be helpful to start with portraits of individual poets. Case studies can usefully give a preliminary illustration of the variety of oral poets, as well as an initial basis for exploring the still prevalent theory that oral poetry is composed anonymously, perhaps even ‘communally’, rather than by individual named poets. We also gain some idea of how poets themselves see their work, and of their interpretation of their role.

6.1 The poet: five examples

The first example is Velema Daubitu the poet and seer, at the village called The-Place-of-Pandanus (Namuavoivoi) in the island of Vanua Levu, Fiji. He was an old man in the 1930s, when Quain recorded and translated a number of his songs (published in 1942). Velema was the composer and performer of several kinds of poetry, but chief among them were heroic poems about the deeds of far-off ancestors who belonged to the legendary kingdom of Flight-of-the-Chiefs, from whom the present chiefs and their subjects believed they were descended. This was the most valued form of oral literature among the Fijians, and it was held that the appropriate person to compose them was a man who—like Velema—was seer as well as poet.

Fig. 6.1. A photo of Velema, traditional Fijian poet, spiritually inspired in trance. From B. H. Quain’ s The Flight of the Chiefs. Epic Poetry of Fiji (New York: J. J. Augustin, 1942).

When Velema was still a child, people began to notice in him the kind of personality and behaviour which made them feel he was destined to be a seer. They noted in particular his diffidence and his excitability, as well as his curiosity about serious things. Because of this Velema was chosen by his mother’s brother to succeed him as priest and guardian of the sacred objects of the village. Over many years Velema learnt from his uncle how to perform the rituals of his land group, and inherited the sacred war club and axe as well as the dancing spear—all of which played a part in his composition of songs. At the same time he was trained in the arts of singing and composition, and learnt the secret mysteries of communing with the ancestors, the inspirers of poems. He ‘learned how it felt to speak with them and even let them use his tongue to speak.’ (Quain, 1942, p. 14). In Fijian poetic theory, the ancestors teach and form the songs. This is believed to go further than mere inspiration: with the ‘true-songs’ or epic songs the ancestors themselves chant the songs as they teach them to the poet, and it is in their name that they are delivered.

During one of my sojourns at Flight-of-the-Chiefs

The-Eldest is calling

is the opening of one of Velema’s ‘true-songs’ (p. 21) in which the ancestor is speaking through Velema’s mouth, and describing how he himself was there in the ancestral home and observed the incidents of the poem which follows. These poems are given to Velema in trance or sleep. He acts only as the mouthpiece of his mentors: ‘he takes no personal credit for his composition, does not even distinguish between those which he has composed himself and those old ones which his mother’s brother must surely have taught him. All contribute to the glory of his ancestors’ (Quain, 1942, p. 14). Even the special liberties that Velema took with language so as to fit the musical and rhythmic requirements of the verse are attributed to the ancestors’ chanting. When Velema chose ‘archaic words from his own background, words which he alone understands’ (ibid. p. 16) so as to fit the rhythm, this too has the implied sanction of ancestral approval.

This insistence on the personal involvement of the ancestors in the poems is made more effective by the stylistic device of first-person interpolations into the epic narrative. From time to time the poet’s recounting of historic events is replaced, as it were, by the direct speech of one of the ancestral actors. This comes out well in the opening sections of one of Velema’s ‘true’ poems, where he describes how the gods of the mythical village of Flying Sand plot to attack Flight-of-the-Chiefs, the ancestral home of Velema and his compatriots. Their ancestor Watcher-of-the-Land discovers the plan, and after vainly trying to find a safe refuge for his friends, comes to Flight-of-the-Chiefs to warn their leader (The-Eldest) of the threatened attack. From time to time Watcher-of-the-Land speaks in his own person (printed in italics).

Those at Flying-Sand hold council;

They hold council there, those Gods of the Beginning.

They decide that Flight-of-the-Chiefs be eaten.

It stings, the foot of Watcher-of-the-Land;

And Sir Watcher-of-the-Land wails forth

So that Flight-of-the-Chief resounds.

And quickly I came outside.

I took up my staff.

I descended to the shore at Bua

I dived down to the Cave of Sharks.

Creeping, I explored the grotto

That those of Flight-of-the-Chiefs might be hidden there.

I crawled outward to the open sea.

I climbed to the village at Levuka.

There are shallows in the open sea,

And Watcher-of-the-Land dives again.

I dived among the white coral rock.

I climbed to the village at Peninsula.

I climbed upward again to Flight-of-the Chiefs.

I entered into The-Land’s-Beginning.

And there is the wailing of Watcher-of-the-Land

And it re-echoes through Flight-of-the-Chiefs,

And Watcher-of-the-Land stands up

And takes again his staff.

And quickly I came outside.

I climbed upward to The-First-Appearance. [a high cliff]

And Watcher-of-the-Land digs a hole

And he disappears down into the second depth in the earth.

And then Watcher-of-the-Land says:

‘The people of Flight-of-the-Chiefs be hidden here,

Then the Gods of the Beginning will find them.’

And Watcher-of-the-Land returns again.

I entered into It-Repels-Like-Fire. [his own village]

And Watcher-of-the-Land is weeping there.

And he takes up his staff.

And quickly I came outside.

And I hurtled downward to Flight-of-the-Chiefs

I hastened to The-Eldest.

Watcher-of-the-Land is weeping there

And now-The-Eldest asks:

‘What report from The-Land’s-Beginning?’

And now Watcher-of-the-Land answers:

‘Listen, then, the-Eldest:

Those at Flying-Sand hold council.

They decide that Flight-of-the-Chiefs be eaten.’

The most important and serious inspirers of poetry are the ‘true ancestors’ from whom Velema learns the heroic ‘true’ songs by virtue of his control of the ancient war club and axe. But there are also other spirits—like the Children of Medicine—who teach him the less serious songs. Velema is a participant in the special Children of Medicine cult, and through this and his possession of his ancestral dancing spear he is able to compose dances and dance-songs as well as serenades. These songs are comparatively short and less complex stylistically than the ‘epic’ poems. They raise fewer problems of composition, and are believed to be inspired by less revered spirits.

Velema not only practised his art in solemn religious surroundings, but took part in dance festivities and sometimes entertained an evening gathering with his songs. On these occasions he chanted the epic songs himself, accompanied by another old man who accompanied him as a kind of chorus. His long training and religious responsibilities made use of, rather than changed, his unusual and excitable personality. As he grew up, people came to recognise his strange talents, and to accept from him actions unacceptable in others, like brooding all day in the house or wandering too often alone in the forest. From a poet and seer, such behaviour was even expected. As Quain sums it up, ‘Though there are sceptics among modern citizens who suspect that the poet exaggerates the virtues of the heroes at Flight of-the-Chiefs, yet no one doubts the validity of his talent for literary rapport with the supernatural. His ancestral communications are the only bonds with the distant past’ (ibid. pp. 8–9).

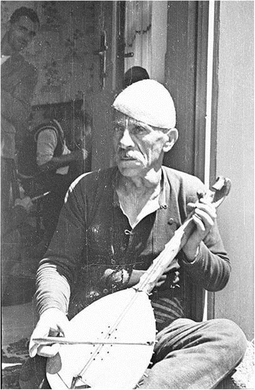

The second poet is the Yugoslav epic minstrel, Avdo Mededović. He has become famous through the researches of Parry and Lord, but throughout most of his life he directed his compositions to local audiences in rural Yugoslavia.

Fig. 6.2. A photo of Avdo Međedović, Slavic guslar player and oral poet. Wikimedia, https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/b/b2/Avdo_Me%C4%91edovi%C4%87.jpg

Avdo Mededović was born, lived and died in eastern Montenegro, in what is now Yugoslavia. His father and grandfather were butchers, and in his mid-teens Avdo began to learn their trade and, despite spending some years away from his home in the army, he ultimately married and settled down to follow them as village butcher. As a Muslim, he and his family were in great danger in the months just after the defeat of Turkey in the First World War, but he managed to survive and keep his butcher’s shop, and to spend the greater part of his life as ‘a quiet family man in a disturbed and brutal world’ (Lord, 1956, p. 123).

Avdo was born into a culture in which epic singers flourished, and grew up hearing the traditional themes sung in epic poems to the gusle (the one-stringed bowed instrument used to accompany singing). This rich tradition behind him provided him with much of the material for his poetry. But he also learnt his art from skilled singers, above all from his father.

He in his turn had been deeply influenced by a famous singer of his own generation, Cor Huso Husein, who still had a prodigious reputation in the area. Cor Huso’s main characteristic was apparently the ability to ‘ornament’ a song, characteristic also of Avdo’s work.

Avdo’s capacity to compose and perform epic was enormous. Though it makes no sense in the type of combined performance-composition typical of Avdo’s art to try to calculate absolute figures of how many poems he ’knew’, it is noteworthy that he claimed to have a repertoire of fifty-eight epics. Parry and his assistant recorded thirteen of these in 1935 (to which must be added the recording of additional versions by Lord in 1950 and 1951). The result is 96,723 lines of recorded epic from Avdo’s singing alone. His longest single song contains 13,331 lines and represents over sixteen hours of singing time. From the mere point of view of quantity it is hardly surprising that Parry was so impressed by Avdo as a singer. As Lord puts it, ‘Avdo could sing songs of about the length of Homer’s Odyssey. An illiterate butcher in a small town of the central Balkans was equalling Homer’s feat, at least in regard to length of song. Parry had actually seen and heard two long epics produced in a tradition of oral epic’ (Lord, 1956, p. 125).

Avdo’s epic versions of stories tended to be longer than anyone else’s because of his ‘ornamentation’. He amplified the details, and elaborated what he had heard from others. He did not merely borrow ‘ornaments’ from other singers, for many came from his visualising the scene himself. As he once told Lord, he ‘saw in his mind every piece of trapping which he put on a horse’ (Lord, 1956, p. 125).

His ability to extend and ornament a song was well demonstrated in 1935, when he heard another poet, Mumin Vlahovljak sing the tale of Bećiragić Meho, previously unknown to Avdo. Mumin was a skilled singer and his song, a fine one, ran to 2,294 lines. As soon as it finished, Parry asked Avdo if he could now sing the ‘same’ song himself. At first he asked to be excused, because he did not wish to offend Mumin or take the honour away from him. When he was finally persuaded to sing, his version reached 6,313 lines, nearly three times the length of the ‘original epic’. ‘As [Avdo] sang, the song lengthened, the ornamentation and richness accumulated, and the human touches of character, touches that distinguished Avdo from other singers, imparted a depth of feeling that had been missing in Mumin’s version’ (Lord, 1968a, p. 78).

A similar example is his great epic The Wedding of Smailagić Meho. Avdo first heard a song on this theme read aloud from a written version. It had been published in a small songbook that Hivzo, the butcher in a shop next to his, had bought in Sarajevo. Hivzo had taught himself to read, and gradually read out the version to Avdo, making out the words slowly and painfully. The printed version had 2,160 lines—but when Avdo performed the song as one of his epic poems in 1935, it stretched to 12,323 lines.

This capacity to ornament and to introduce his own personal touches, sometimes reflecting insights obviously drawn from his own experiences, runs through all Avdo’s poems. It was this, rather than a superlative performance, that gave his poems such force, for his voice was not especially good (it was rather hoarse), and his accompaniment on the gusle was only mediocre. But in his poems he could convey the conventional themes of Slavic epic and his own personal commentary on them. He was dedicated to the themes and atmosphere of the epics he performed:

The high moral tone of his songs is genuine. His pride in tales of the glories of the Turkish Empire in the days of Sulejman, when it was at its height and when ‘Bosnia was its lock and its golden key’, was poignantly sincere without ever being militant or chauvinistic. That empire was dead, and Avdo knew it, because he had been there to hear its death rattle. But it had once been great in spite of the corruption of the imperial nobility surrounding the sultan. To Avdo its greatness was in the moral fibre and loyal dedication of the Bosnian heroes of the past even more than in the strength of their arms. These characteristics of Avdo’s poems, as well as a truly amazing sensitivity for the feelings of other human beings, ‘spring from within the singer himself. He was not ‘preserving the traditional’; Avdo believed with conviction in the tradition which he exemplified.

(Lord, 1956, p. 123–4)

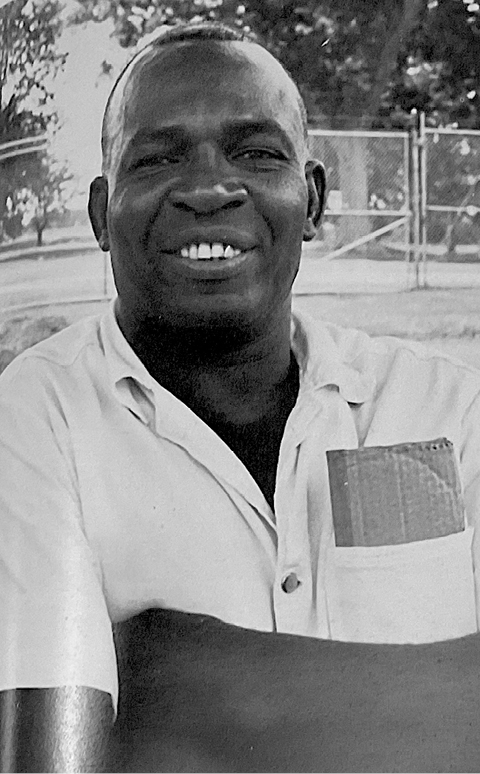

A very different example is the American prisoner Johnnie B. Smith. He had spent much of his life in Texas prisons and it was in prison that he had developed the songs through which, Bruce Jackson says, ‘he has woven an elaborate construct of images that brilliantly details the parameters of his world’ (Jackson, 1972, p. 144).

Fig. 6.3. A photo of Johnnie B. Smith, a life prisoner in Texas. From Bruce Jackson (ed.), Wake Up Dead Man: Afro-American Workings from Texas Prisons (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972).

When Jackson, researching on prison songs, met Smith in a Texas prison in the mid-1960s, Smith was in the eleventh year of a forty-five-year sentence for murder. It was not his first sentence, for he had three previous convictions for burglary and robbery by assault. Here he describes the murder:

I got out of here on those ten-year sentences, that robbery by assault. I lost my people while I was in here and I just felt like I was kind of in the world alone. I wanted to find me a pretty girl to settle down with and marry. I was thirty-five years old then. And I just wanted to marry and settle down. I left my home down at Hearn, Texas, other side of Bryant, and went to west Texas, out in the Panhandle country, to Amarillo. And I married a beautiful girl. She was about three quarters Indian, I guess. A lot of mixed-breed girls out there, ‘specially around Mexico and Oklahoma and Amarillo. I found me that pretty girl, the girl of my dreams I thought, and I had good intentions. But now, I fell in love with her, was what I did, and I got insane jealousy mixed up with love. So many of us do that. Lot of fellas in here today on those same terms. I was really insane crazy about the girl and I had just got out of the penitentiary and I was working, just trying to make an honest living and to keep from coming back. But I couldn’t give her all she wanted and she’d sneak out a little. That went to causing trouble. I was intending to get in good shape, but I hadn’t been out there long enough, not to make it on the square, you know. She wanted a fine automobile, she like a good time, a party girl, she liked to drink, she liked to dress nice. So did I, and so I was living a bit above my income. And she would sneak out to enjoy these little old pleasures and that caused us some family trouble. On a spur of the moment I came in one day, we had a fight and I cut her to death. And regret it! Because I loved her still and still do and can’t get her back.

Forty-five years is to all intents a life sentence. In prison on this long sentence Smith composed the poetry under his name in Jackson’s collection of Texas prison work songs.

This poetry takes the form of the solo part in songs designed to accompany the work prisoners have to do throughout the day. Some of these songs give small scope for originality. These accompany strictly metered work, in which the timing is critical for effective working and to avoid injury to co-workers—where several men are simultaneously chopping down a tree, for instance. In songs for work like this, the verbal element is relatively simple, with short lines and automatic repetition giving the lead singer time to prepare his next line. But for songs to accompany less strictly timed work—cane cutting or cotton picking for instance—there is more opportunity for the soloist. They tend to be more complex in text as well as in melody and ornament, and offer the soloist scope for experiment.

Smith was an effective leader in the strictly timed songs, and even there he set his own stamp on the words. But in the solo verses of songs for less rigidly metered tasks Smith had the fullest scope for originality. Jackson’s collection of non-metered work songs by Smith runs to 132 separate stanzas. Though the sections were often sung separately (and even sometimes given separate titles) Smith usually thought of them as really one song, and sometimes talked of them in that way.

His songs are very much a function of his surroundings and reflect his and his co-prisoners’ concerns. As Smith once said, ‘Guy down here, if he’s thinkin’ about anything at all, he’s thinking about his freedom and his woman’ (ibid. p. 37). Eighteen stanzas are indeed about ‘his woman’, and there are frequent mentions of places outside prison, in the world of freedom. But it is the negatives of his basic concerns that Smith is thinking more of—the constraints and bonds that keep him from his woman, and restrict his freedom. Thus many of the stanzas refer to the length of his sentence, or the possibility of escape, and there are constant references to the guards and the prison officials, to firearms and to sickness and death. As Jackson puts it,

The reason Smith (he is the most creative song leader I met; the statements here apply even more to the others) cannot dwell at any length on his woman or his freedom is that he does not really think of them so much as of their absence; he perceives the negative, and in his imagistic song-world there are no terms to present these feelings (for they are not things) directly. All he can do is deal with the devices of control: the number of years he has to do, the weapons of the guards, the presence of the guards, the existence of other places to which he has no access. To express both hope and longing, both his sense of self and his lack of control over that self’s movements, the singer is forced to document the concreteness of the enemy, the prison itself, because that is all that is concrete, and depend on rhetoric to return to his real themes.

This is evident in the opening of his song ‘No More Good Time in the World for Me’

No more good time, buddy, oh man, in the wide, wide world for me,

‘Cause I’m a lifetime skinner, never will go free.

Well a lifetime skinner, buddy, I never will go free,

No more good time, buddy, in the wide, wide world for me.

Lifetime skinner, skinner, hold up your head,

Well you may get a pardon if you don’t drop dead.

Well you may get a pardon, oh man, if you don’t drop dead,

Oh well lifetime skinner, partner, you hold up your head.

I been on this old Brazos, partner, so jumpin’ long,

That I don’t know what side a the river, oh boy, my home is on,

Don’t know what side a the river, oh man, oh boy, my home is on,

‘Cause I been down on this old river, man, so jumpin’ long.

Well I lose all my good time, ‘bout to lose my mind,

I can see my back door slammin’, partner, I hear my baby cryin’.

Yeah, I’m a hear my back door slammin’, man, I hear my baby cryin’,

I done lose all my good time, partner, I’m ‘bout to lose my mind…

There is a full account of Smith’s style and the way he built up his own individual insights and imagery in a traditional framework in Jackson’s book (1972, esp. pp. 143ff). Despite his obvious talent and creativity, Smith felt that it was his circumstances rather than his own application that generated his poetry.

Now these songs, we can, you know, you stay here so long, a man can compose them if he want to. They just come to you. Your surroundings, the place, you’re so familiar with them, you can always make a song out of your surroundings. I read about some great poetry, like King David in the Bible, he used to make his psalms from the stars and he wrote so many psalms. A little talent and surroundings and I think it’s kind of easy to do it.

The fourth example is the Inuit poet, Orpingalik. Although we do not know much about his life or his economic position qua poet, his articulateness about his poetry and his greatness as a poet in the eyes of Inuits and foreigners make him an interesting member of this group of brief case studies.

Orpingalik was a member of the Netsilik group of Inuits in the interior of the Rae Isthmus area of northern Canada, which was visited by Rasmussen in his great expedition through Inuit country in the early 1920s. Our knowledge of Orpingalik’s personality and poetry derive from the publications in which Rasmussen reported his findings from that expedition.

Orpingalik—’He-with-the-willow-twig’—was a man of mature years when Rasmussen met him, with several full-grown sons, a daughter, at least one grand-child, and a wife, Uvlunuaq (‘The-little-day’), who was herself a notable poet. Orpingalik himself was accepted by local people as outstanding in many ways: ‘a big man’. He was a great hunter—important to an Inuit group living under the constant threat of starvation if the game on which they depended eluded them. He was also a strong and deadly archer, and ‘the quickest kayakman of them all when the caribou herds were being pursued at the places where they crossed the lakes and rivers’ (Rasmussen, 1931, p. 13).

Orpingalik was revered as a shaman as well as for his physical skills. Hewas an angakok who could communicate with the spirits in seance, and he had his own guiding spirits who had chosen him of their own volition and whom he could summon through their spirit songs and commune with in the special metaphorical shaman’s language. As shaman he was versed in the intellectual and poetic traditions of his people—he recounted many tales as well as poems to Rasmussen during his visit—and was also the personal possessor of many magic songs and spells. These belong to him alone, and no one else had the right to use them. Even Rasmussen could not record them free, but paid Orpingalik in kind ‘giving him in return some of those I had obtained from Aua [another shaman].’ (Rasmussen, 1927, p. 161). Control of these spells added to Orpingalik’s prestige and power: they enabled him to catch seals, to hunt in a strange country, to injure his enemies and, as in this one, to kill caribou unscathed

Wild caribou, land louse, long-legs,

With the great ears,

And the rough hairs on your neck,

Flee not from me.

Here I bring skins for soles,

Here I bring moss for wicks,

Just come gladly

Hither to me, hither to me.

But the power of a shaman could rebound too—or so it seemed in Inuit eyes—and Orpingalik’s life held suffering as well as leadership and prestige. Only a year before his meeting with Rasmussen, Orpingalik and his youngest son Inugjag had met disaster, and all his power and skill as shaman had not availed to save his son’s life. He and lnugjag had been ferrying their possessions over a wide river on an icefloe when the swift current suddenly caught the floe and overturned it. Orpingalik and his son were immediately sucked under.

When Orpingalik at length came to himself he was lying on the bank, half in the water, with his head knocking against a stone. The pain brought him to his senses, and a glance at the sun told him that he must have lain unconscious a long time. All at once the catastrophe became vividly clear to him and he began to look for his son, whom he found a little way further down the river. He carried him up to the bank and tried to call him to life with a magic song. It was not long before a caterpillar crawled up on the face of the corpse and began to go round its mouth, round and round. Not long afterwards the son began to breathe very faintly, and then other small creatures of the earth crawled on to his face, and this was a sign that he would come to life again. But in his joy Orpingalik went home to his tent and brought his wife to help him, taking with him a sleeping skin to lay their son on while working to revive him. But hardly had the skin touched the son when he ceased breathing, and it was impossible to put life into him again. Later on it turned out that the reason why the magic words had lost their power was, that in the sleeping skin there was a patch that had once been touched by a menstruating woman, and her uncleanness had made the magic words powerless and killed the son.

Other Inuits explained the incident differently. They pointed out that the ice floe would not normally have capsized—’it was as if the floe suddenly met with some resistance that forced it down under the waters of the river’—and that the cause of the disaster was magic words that had rebounded on their master after Orpingalik had tried to kill another shaman. He turned out to be more powerful than Orpingalik and the evil spell turned back against its maker: since it could not kill Orpingalik himself—for he too was a great shaman—it took his son’s life instead. ‘For a formula of wicked words like that must kill if there is any power in it; and if it does not kill the one it is made for, it turns against its creator, and if it cannot kill him either, one of his nearest must pay with his life’ (Rasmussen, 1931, p. 201).1

So the position and insights of a shaman among the Inuit involved hazards and suffering as well as prestige. They could not help, either, to save Orpingalik’s other son, Igsivalitaq, from the bitterness of long exile from his family after he had murdered a hunting companion in a fit of temper. He had to live as an outlaw in the mountains, cut off from his people. His mother Uvlunuaq described the pain of his deed and his exile in a long poem

When message came

Of the killing and the flight,

Earth became like a mountain with pointed peak,

And I stood on the awl-like pinnacle

And faltered,

And fell!

(Freuchen, 1962, p. 283)

We must set Orpingalik the poet against this background of experience and suffering. For him his songs were his ‘comrades in solitude’, and ‘all my being is song’ (Rasmussen, 1931, pp. 16, 15). Rasmussen thought him the most poetically gifted man he had met among the Netsilik Inuit, with a luxuriant imagination and most sensitive intelligence (ibid. p. 15). Orpingalik was always singing when he had nothing else to do, and felt that his songs were a necessity to him, as much so as his breath: part and parcel of himself.

How many songs I have I cannot tell you. I keep no count of such things. There are so many occasions in one’s life when a joy or a sorrow is felt in such a way that the desire comes to sing; and so I only know that I have many songs. All my being is song, and I sing as I draw breath.

(ibid. p. 16)

One of his most famous songs he called My breath, for, as he explains ‘it is just as necessary for me to sing it as it is to breathe’ (p. 321 ). He composed the poem when he was slowly recovering from a severe illness. He reflects on his present helplessness and reminisces about the past when he was strong and a hunter who could save the village from famine while his companions still slept. Into his poem he pours his despondency and self-questioning as he struggles to regain his strength and vigour.

My Breath

This is what I call this song, for it is just as

necessary to me to sing it as it is to breathe.

I will sing a song,

A song that is strong,

Unaya—unaya.

Sick I have lain since autumn,

Helpless I lay, as were I

My own child.

Sad, I would that my woman

Were away to another house

To a husband

Who can be her refuge,

Safe and secure as winter ice.

Unaya—unaya.

Sad, I would that my woman

Were gone to a better protector

Now that I lack strength

To rise from my couch.

Unaya—unaya.

Dost thou know thyself?

So little thou knowest of thyself.

Feeble I lie here on my bench

And only my memories are strong!

Unaya—unaya.

Beasts of the hunt! Big game!

Oft the fleeing quarry I chased!

Let me live it again and remember,

Forgetting my weakness.

Unaya—unaya.

Let me recall the great white

Polar bear,

High up its back body,

Snout in the snow, it came!

He really believed

He alone was a male

And ran towards me.

Unaya—unaya.

It threw me down

Again and again,

Then breathless departed

And lay down to rest,

Hid by a mound on a floe.

Heedless it was, and unknowing

That I was to be its fate.

Deluding itself

That he alone was a male,

And unthinking

That I too was a man!

Unaya—unaya.

I shall ne’er forget that great blubber-beast,

A fjord seal,

I killed from the sea ice

Early, long before dawn,

While my companions at home

Still lay like the dead,

Faint from failure and hunger,

Sleeping.

With meal and with swelling blubber

I returned so quickly

As if merely running over ice

To view a breathing hole there.

And yet it was

An old and cunning male seal.

But before he had even breathed

My harpoon head was fast

Mortally deep in his neck.

That was the manner of me then.

Now I lie feeble on my bench

Unable even a little blubber to get

For my wife’s stone lamp.

The time, the time will not pass,

While dawn gives place to dawn

And spring is upon the village.

Unaya—unaya.

But how long shall I lie here?

How long?

And how long must she go a-begging

For fat for her lamp.

For skins for clothing

And meal for a meal?

A helpless thing—a defenceless woman.

Unaya—unaya.

Knowest thou thyself?

So little thou knowest of thyself!

While dawn gives place to dawn,

And spring is upon the village.

Unaya—unaya.

(ibid. pp. 321–3)

Besides his powers as poet and shaman, Orpingalik also had the ability to reflect self-consciously on the process of poetic composition and the functions of poetry. He had many discussions with Rasmussen about the significance of song both as an outlet for sorrow and anxiety and as a herald of festivity. He also explained how he conceived of a poem being born in the human mind, a passage interesting enough to quote once more

‘Songs are thoughts, sung out with the breath when people are moved by great forces and ordinary speech no longer suffices.

Man is moved just like the ice floe sailing here and there out in the current. His thoughts are driven by a flowing force when he feels joy, when he feels fear, when he feels sorrow. Thoughts can wash over him like a flood, making his breath come in gasps and his heart throb. Something, like an abatement in the weather, will keep him thawed up. And then it will happen that we, who always think we are small, will feel still smaller. And we will fear to use words. But it will happen that the words we need will come of themselves. When the words we want to use shoot up of themselves—we get a new song.’

(ibid. p. 321)

Most detailed descriptions of individual oral poets are of men. There are references to women poets too, but these tend to be more generalised, and it seems that it is less common for specialist poets to be women. But one expert woman poet about whom we know a good deal is the American singer, ‘Granny Riddle’, acclaimed by folklorists and public alike as a ‘folksinger’. Her memories and songs were recorded on tape by Roger Abrahams and published in 1970 as A Singer and her Songs.

Almeda Riddle was born in 1898 in the Ozarks, Arkansas, and spent most of her life in the region. Her father was part-Irish (his mother’s people had come to America from Ireland) and he lived first from timber-working, then farming. He was also a singing master and enthusiastic singer: ‘He sang all the time. He’d go into any community that we went into, and if they didn’t have a singing class, he immediately taught a ten-day school. Those that could pay him, paid him, and those that couldn’t, couldn’t’ (Abrahams, 1970b, p. 6). He himself was accustomed to using written versions—’he sang most of his songs from the books’ (ibid. p. 6)—and in this way helped to form his daughter’s musical experience. She says ‘Every morning before breakfast … I don’t ever remember a time that he didn’t sit down with his book and sing a song or two. And after supper each night, he’d always sit down and sing awhile. And from the time I can remember, I got ‘round and sang, too. I knew my notes before I knew my letters’ (ibid. p. 6).

Her mother, by contrast, relied more on oral transmission, and passed on to Almeda Riddle a number of songs she had learnt from her own mother. Of one song, ‘My mother [said] she had learned that from her mother and her mother said she could remember her own mother singing it to her. And I am now singing it to my great-grandsons. And as her own mother came from Ireland, she supposed she learned it in Ireland’ (ibid. p. 42). Other songs she learned from members of her mother’s family, or from a wide circle of friends and acquaintances—for, as she describes it herself, Almeda Riddle had a ‘passion’ for collecting songs.

Not surprisingly, Almeda’s method of learning and performing songs used both written and oral sources from the start. She clearly had a remarkable verbal memory and very quickly picked up songs she heard. But at the same time she liked to keep a written record—what she termed ‘ballets’—and from an early age had a large collection of written texts.

In her recollections, Almeda Riddle speaks vividly of the effect her early upbringing had on her development as singer. Her father’s influence, in her account, was the strongest of all, but it is clear that singing also formed part of her family life generally, and of much contemporary life around her. She used to sing with her sister and school friends, or creep in to listen to older girls singing ballads. When she and her future husband were courting, they used to sing and discuss singing together: ‘We’d sit on the back porch and talk of books we’d read or things we’d seen or of songs we knew. Sometimes we’d just sing’ (ibid. p. 67).

Singing often accompanied work—it went with sewing or spinning or making soap—and Almeda Riddle says that one reason she can remember so many songs was that she used to sing them to her cow as she milked. Song was also associated with the Primitive Baptist church of which she was a member, and a number of her songs were learnt there.

Her life was interspersed with tragedy. After only nine years of marriage, her husband and baby were killed in a cyclone in 1926, and she returned home to her father’s farm with her three small children. An experience that in some ways affected her even more deeply was the death of her elder sister Claudia, with whom she used to sing.

One of the earliest remembrances I have in life was playing with my sister, Claudia, who was four years older than I. We were rocking our dolls to sleep and singing to them. My father, who was a singing teacher, always sang with us a while almost every night before bed time. I don’t remember the songs we sang while Claudia was with us, but I do remember she sang very well and had a beautiful face, long golden hair, and a very sweet voice. She died after only three days’ illness in August before I was six years old. I do remember the day she was taken sick quite well. We sat out in a peach tree in the backyard and sang and ate half-ripe peaches. She said she was getting cold, so we went inside. She was put to bed with a chill, what at that time, 1904, was no unusual thing in Arkansas. There was so much of what people called chills and fever—malaria. And she died the third day of her illness, after two more chills. I had what I guess you would call today a ‘mental breakdown’, and my father had to take me out in the woods with him each day. And for many months I remember I would only cry and say No when I was asked to sing.

(ibid. p. 5)

Despite this, her passion for singing and song collecting continued, and in later life this was recognised by folksong collectors throughout the United States, who dubbed her ‘Granny’, for by her sixties she was already a great grandmother. She sang for commercial recording companies2 and with well-known bands as well as for local and family audiences, ‘folk festivals’ and university concerts.

Her repertoire covered both her favourite ‘classic’ ballads, as she called them—mostly those included in the Child canon, like Barbara Allen, The Four Marys, Lady Margaret—but also some popular songs of the day, and even songs she had based on printed texts in newspapers or developed from recitations. Though she apparently laid great store on her songs being old and belonging to authentic tradition in some sense, she was by no means a passive traditor only. She explains herself how she changes a song in certain ways while singing, even though she dislikes the idea of over dramatising her performances: ‘Now, it’s scarcely ever, if you sing a song from memory, that you’ll sing it exactly word for word each time. You’ll probably change a word here and there, which keeps it changing. This is true of all songs, the classic songs and other kinds’ (ibid. p. 117). Her musical interpretations are noted for their richness and individuality. She uses variations to enhance the meaning of her story, so that almost every verse has its own nuances in actual performance. As one observer explains, ‘She not only cultivates meaningful texts but creates a rich flexibility within the tune to accommodate the changing speech from stanza to stanza’ (Foss in Abrahams, 1970b, p. 162).

In what she calls the ‘classic songs’ she emphasises that she is less prepared to make changes than in what she regards as newer songs. In the classics, she insists on keeping the ‘meaning’ as it has come to her even when she makes verbal changes

The words, you know, are fluid … they might change this way or that, but never the meaning. I wouldn’t consciously change the words of a song, and I’d be very careful not to change the meaning. But now I might sing you ‘Barbara Allen’ today one way, and I have at least six or eight versions of that, so tomorrow some of this version or that might creep in.

(ibid. p. 120)

With other songs she is more prepared to claim a piece as her own. Her account of the way she worked out her own interpretation of Go tell Aunt Nancy is worth quoting at some length.

Well, ‘Go tell Aunt Nancy’ is not a classic; it’s my own version. Most of it I wrote … for the kids, and just to sing it to them ... This arrangement of mine, I never heard of it except we kids just made it up, and sang it along as a child. Probably it’s not any more authentic than I am … The first of that I heard was as a child. A little girl, Merty Cowan, sang that. I was very small, first school. And then my mother sang some verses of this. I guess the original is really the old goose who was always in the millpond. But I’ve always sung where she was killed by a walnut, definitely—the walnut hit her on the top of the head and killed her. Aunt Nancy’s goose, and I remember as a child having some fierce arguments with school children over this song. Now, Merty Cowan sang it, the first time I heard it. She sang it as Aunt Nancy, and a walnut killed it. This was an older girl. I was about six, and I got it into my mind like that. Now these other verses have been picked up along the way from other children’s versions of ‘Aunt Nancy’ and from my mother’s. I remember one fight I had about the way she was buried and the way that the old goose ‘died in the millpond, standing on her head’. And I said it definitely was Aunt Rhody’s goose and not Aunt Nancy’s. And so, I still say Aunt Nancy’s goose was definitely killed by a walnut. She didn’t die in the millpond.

And children like the way it’s done now, and it’s recorded like that. That’s just Granny’s version of’ Aunt Nancy’ and I think it’s nobody else’s. I’ve sung that thing so long that I don’t remember where it all comes from …

Go tell Aunt Nancy, go tell Aunt Nancy,

Go tell Aunt Nancy, her old grey goose is dead.

The one that she’s been saving, one that she’s been saving,

The one that she’s been saving, to make a feather bed.

Down come a walnut, down come a walnut,

Down come a walnut and hit her on the head.

Go tell Aunt Nancy, poor old Aunt Nancy,

Go tell Aunt Nancy the old grey goose is dead.

The gander is weeping, gander is weeping,

The gander is weeping, because his wife is dead.

Her goslings all crying, and weeping and peeping,

Her goslings all crying, their mammy they can’t find.

Down come a walnut, down come a walnut,

Down come a walnut and hit her on the head.

Go tell Aunt Nancy, poor old Aunt Nancy,

Go tell Aunt Nancy her old grey goose is dead.

Go tell Aunt Nancy, go tell Aunt Nancy,

We took her in the kitchen and cooked her all day long.

And she broke all the forkteeth, broke all the forkteeth,

Broke all the forkteeth, they weren’t strong enough.

Broke out Grandad’s teeth, broke all Granddad’s [sic] teeth,

Poor old Granddad’s teeth, the old grey goose was tough.

Go tell Aunt Nancy, go tell Aunt Nancy,

Go tell Aunt Nancy that the old grey goose is tough.

Go tell Aunt Nancy, go tell Aunt Nancy,

Go tell Aunt Nancy, we hauled her to the mill.

We’ll grind her into sausages or make her into mincemeat,

Grind her into sausages, if the miller only will.

She broke all the sawteeth, broke all the sawteeth,

Broke all the sawteeth, it was not strong enough.

Broke all the sawteeth, tore down the saw mill,

Broke up the circle saw, that old grey goose is tough.

Go tell Aunt Nancy, go tell Aunt Nancy,

Go tell Aunt Nancy, we know this is a shock.

But go tell Aunt Nancy, poor old Aunt Nancy,

Go tell Aunt Nancy we buried her under a rock.

Go tell Aunt Nancy, go tell Aunt Nancy,

Go tell Aunt Nancy the old grey goose is dead.

Down come a walnut, down come a walnut,

Down come a walnut and hit her on the head.

(ibid. pp. 1 17–20)

Granny Riddle’s success as a ‘folksinger’ seems to be due to her abilities as a performer and interpreter as much as to her powers of original composition—insofar as these can be distinguished. But to her what is of explicit and first importance is not her performing skill but the songs themselves, ‘classic’ or otherwise: these she regards as of enduring value. Typically she ends the tape-recorded account of her life with the words

So that’s all there is about my songs and myself. And as far as I’m concerned, that’s a good deal too much about me—and maybe not enough about the songs. But I’ll tell you one thing: I’ve sung ever since I remember. I intend to sing as long as God gives me a cracked-up voice to do it with. And I intend to sing these songs. But my own greatest, pushing ambition is to get all of the songs I know either on tape or in book form and leave it. Free for anybody that wants to use it. And you can sign that: Granny Riddle.

(ibid. p. 146)

Collectors of oral literature have not always taken much interest in individual poets, so there is a relative dearth of material on the personalities and careers of individual poets. Even so, there are others who could have been described here if space permitted. There was the famous nineteenth century Somali poet Sheikh Mahammed ‘Abdille Ḥasan for instance, better known to European historians as the ‘Mad Mullah’ and leader of the fighting Dervishes (Andrzejewski and Lewis, 1964, pp. 53ff). Among women poets one could mention the opulent Moorish poet in Mauretania, Yāqūta mint ‘Alī Warakān, who can support a comfortable well-furnished house from her art, and is efficient at guarding her own songs from piracy by others and ready to sing her own praises

From what ruby, O Lord of the throne, is Yāqūta?

From the source of pearl and ruby she is fashioned…

She is the full moon, but without a blemish in it…

(Norris, 1968, p. 53)

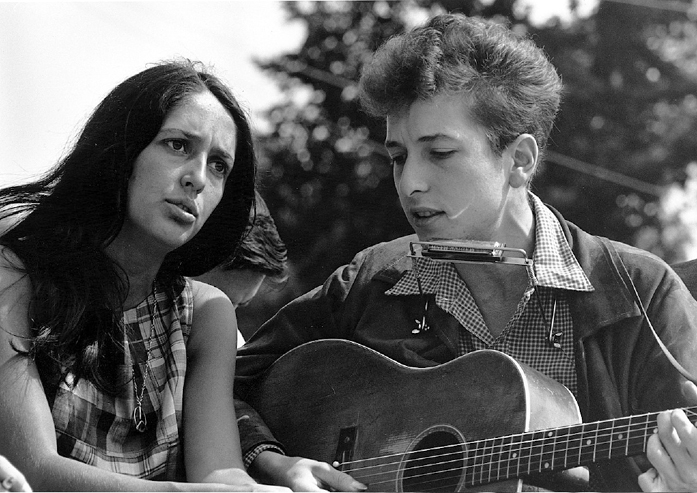

There is the flirtatious Maori poet Puhiwahine who died in 1906, the daughter of the poetess Hinekiore, who was both skilled in traditional poetic forms and prepared to innovate in poetry from new experiences and contacts—famous not only for her poetry but also for her personality and many love affairs (Jones, 1959–60). Again, there are studies of recent oral poets, like Larry Gorman, Leadbelly, the Beatles, or Bob Dylan.

It is probably clear from the portraits given here that something is known about individual oral poets, and that further knowledge would be useful for what it tells us about modes of oral transmission and composition, local theories about poetry and the role of poets, as well for the help it provides in testing older theories about the anonymity of oral poetry or the communal and basically un-individualised nature of oral composition.

Something of the variety of the poet’s personality, training and circumstances emerges from this glance at a few creators of oral poetry. This variety is the main point to emerge when one tries to compare the positions and activities of oral poets throughout the world. But there are also common ways in which societies have come to arrange their literary institutions, and the activities of poets can thus be seen to fit, quite often, into recurrent patterns. Though these are not comprehensive or exclusive, it is illuminating to glance at some of them.

6.2 Some types of poets: specialists, experts and occasional poets

In some societies the role of poet is a specialised one—at any rate for the poet of certain approved kinds of poetry. There are the priest-poets once found widely throughout Polynesia, the highly trained and honorific poets of Ruanda or Ethiopia and the recognised high-status grade of fili in early Ireland. In these cases the practice of poetry (of a particular kind) fits with other honoured institutions in the society—most often religious or political. Like the Fijian Velema, the practitioners of this poetry have an approved position consistent with the recognised values and power-structure of the society.

This is particularly obvious with the praise poets often attached to the courts of rulers. In the Zulu kingdoms of South Africa, every king or chief with pretensions to political power had his own praiser or imbongi among his entourage. At the more elaborate courts of West African kingdoms, there were often whole bands of poets, minstrels and musicians, each with his specialised task, and all charged with the duty of supporting the present king with ceremonial praise of his glory and the great deeds of his ancestors. The old and powerful kingdom of Dahomey had a whole series of royal orchestras, while in Hausa states teams of praisers included musicians and singers with their own royal titles permanently recognised at court. In Hawaii a poet termed the ‘master-of-song’ (haku-mele) was attached to a chief’s court, with the duty of composing ‘name chants’ to glorify the exploits of the chiefly families as well as transmitting and performing older praise poems and genealogies handed down from previous poets (Beckwith, 1951, p. 35). Court poets are common in aristocratic or hierarchical societies, from the poets of mediaeval Wales, Ireland and Scotland to the early Tamil bards or the minstrels of nineteenth-century Kirghiz sultans.3

In these contexts, the role of poet is often highly skilled and involves specific training. This may involve personal apprenticeship to a qualified practitioner. The Fijian Velema was taught his craft by his maternal uncle, who at the same time passed on to him the authority and mystique of a seer and priest. Or the apprenticeship may—as with the Ifa oracle priest poets in Southern Nigeria—involve a course of learning in which the novice goes to a number of qualified experts, often over several years, before he is considered to have mastered his craft. Training of poets is a fairly common pattern, found in places as far apart as mediaeval Ireland and Scotland, Polynesia and Central Africa, and shows the seriousness with which the acquisition of poetic skill and knowledge is locally regarded.

This is taken even further, with the institution of a fully organised ‘school’ or official system of training. This is not uncommon even in largely non-literate societies. The Maori ‘school of learning’ is an example. This was a house, often specially built, in which selected youths of well-born parents were formally taught the traditional poetry and sacred knowledge of the priest-poets. There were grades of proficiency through which the candidates could pass, and moving upward depended on passing examinations conducted by expert teachers (Best, 1923). Similar formal training for poets in schools for the well-born was common in the major islands of Eastern Polynesia (Luomala, 1955, p. 45). Again, there is the training in poetry received by the high-status poets in Ruanda under the overall supervision of the president of the poets’ association. There were Druidic schools in Caesar’s Gaul, mediaeval Irish bardic schools and schools of rhetoric designed to train the Ethiopian dabteras poets in the art of qene composition.

With a publicly recognised and specialised role, poets have often become a power in their own right. They help to uphold the authority of state or religion—which gives them their own position—and also sometimes keep a firm hold on their monopoly by conducting their own examinations or other controls over the entrance of new recruits. This is the case with Maori and Ruanda poets. Succession to the powerful positions which poets may hold is not infrequently hereditary, so that powerful dynasties of poets can establish themselves, sometimes forming a recognised and dominant grade within society as with the Marquesan and Mangarevan master bards in Polynesia, the privileged early Tamil minstrels, the early Irish or Scottish poets and perhaps the Brahmanic reciters of the sacred Vedic literature.

Among these more specialised types of poet, there is often a split between reciters and composers. This is especially so when the delivery of the poem involves a group of specialists working together—the West African orchestra, for instance, or Mangarevan song groups, who must to some extent rehearse their performances. It is particularly common with specialist religious poets preserving a conservative tradition where, in theory and often in practice, they are delivering or interpreting traditional material. This is so, presumably, with many transmitters of Vedic literature in India, just as it can also be said of the priests and ministers who carry on and disseminate the literary heritage of the Christian Church, some of which must be classed as a kind of oral poetry. Some praise poets learn the praises of older rulers from previous poets, and may do little more than preserve these in their public recitations, reserving their newer compositions for more recent events. But there are also cases of a joint performer/composer role, and even with the more powerful and specialised type of poet, there seems to be no absolute need for this further specialisation into reciter as distinct from composer.

One corollary of the special status of such poets is the return they get from practising their craft. Sometimes they are mainly (even perhaps fully?) supported by it and so can be regarded as professionals. A king’s maroka praise teams in Northern Nigeria rely heavily on their position for their livelihood: ‘they are allocated compounds, farm-lands, and titles by the king, who may also give them horses and frequently provides them with clothes, money, or assistance at weddings, as well as with food’ (Smith, 1957, p. 31). Mediaeval Scottish bards built up powerful hereditary families with extensive lands (Thomson, 1974, pp. 12ff) and the Irish court poet expected lavish generosity and ‘an estate of land of the best kind and an abode near his chiefs court’ (Williams, 1971, p. 3). Their earlier counterparts, the fili or ollam, could expect the reward for a poem to be reckoned in cattle or horses. When poets formed a special hereditary class or caste (as sometimes, for example, in Polynesian, Indian and Gaelic society) their economic as well as their socio-political status were related to the practice of their art, and their right to land and other capital possessions followed from this.

Considering the authoritative position often held by such poets, it is not surprising that the view of the poets’ role held by them and by members of their culture often involves reference to a higher sanction underlying their words and position. This is particularly so for poets with religious authority. It is common for the poet’s words to be attributed to some power beyond him. Velema’s poems were composed by some ‘true ancestor’; the Vedic scriptures were divinely revealed rather than composed by human poets, and the hymns of the great Zulu prophet and founder of the Church of Nazareth, Isaiah Shembe, were felt to have been directly imparted to him by God. Many other instances of this emphasis on inspiration in early Europe as well as recent oral literature elsewhere are recorded in Nora Chadwick’s analysis, Poetry and Prophecy (1942). The claim to divine inspiration in the production of poetry is likely to assist such poets to retain their positions of power or prestige.

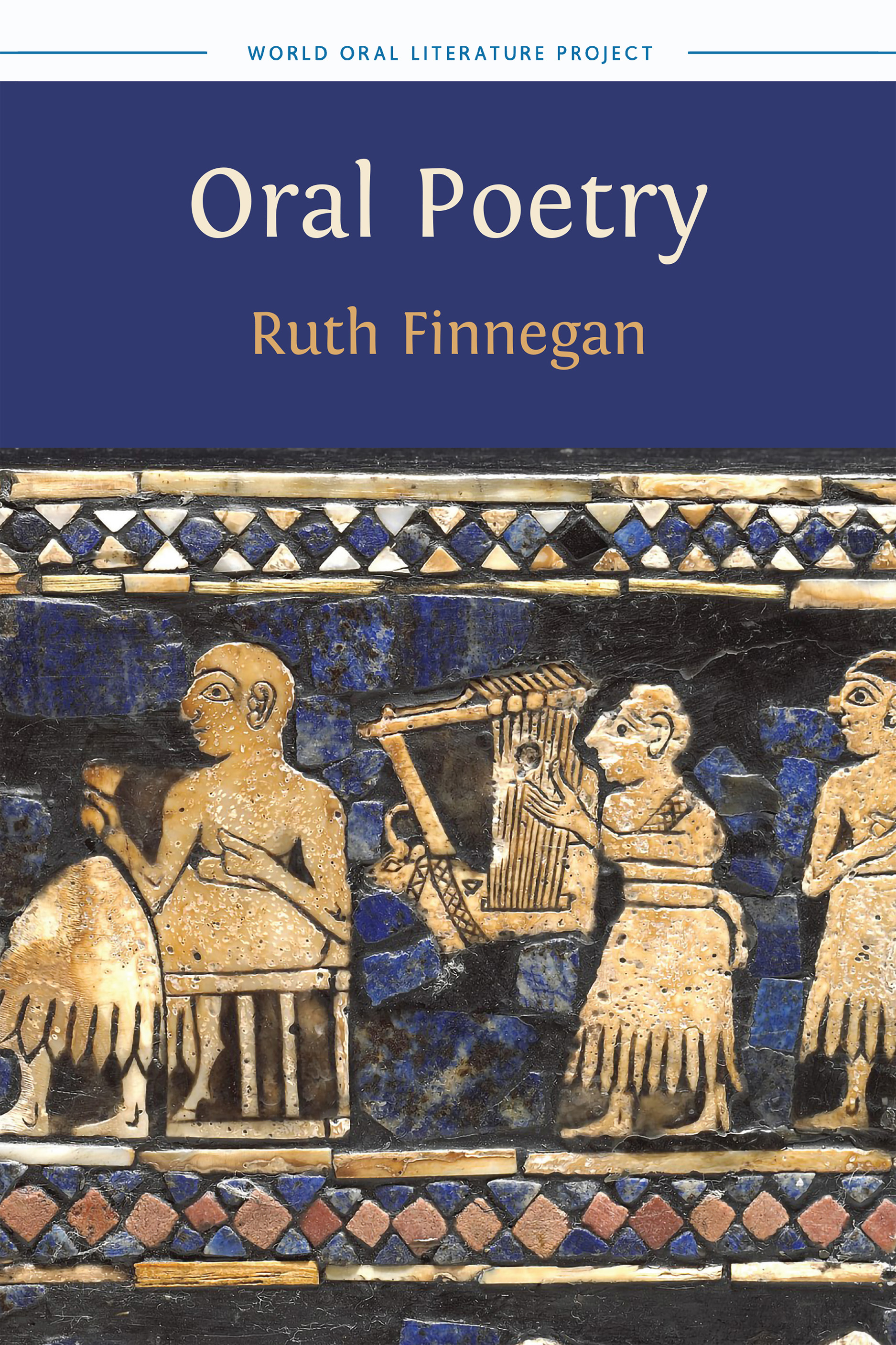

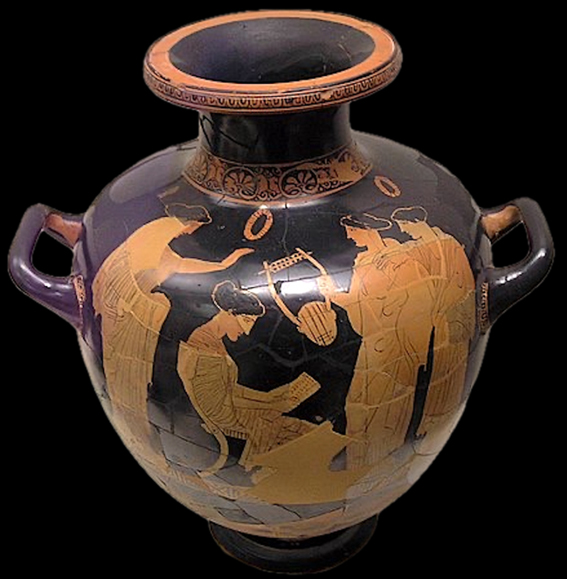

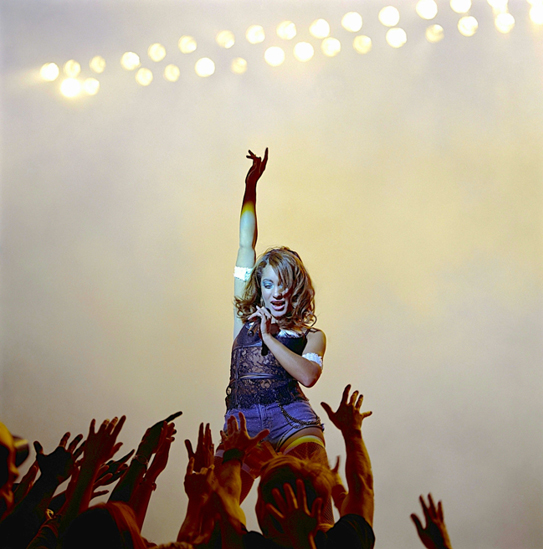

Fig. 6.4. Oral poets of yesterday and today:

6.4.1. A photo of a tablet with pre-cuneiform writing from the Uruk III era, late 4th millennium B.C. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:P1150884_Louvre_Uruk_III_tablette_%C3%A9criture_pr%C3%A9cun%C3%A9iforme_AO19936_rwk.jpg

6.4.2. Depiction of a lyre player and singer on the Standard of Ur, circa 2500 B.C. British Museum. Wikimedia, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Standard_of_Ur#/media/File:Ur_lyre.jpg

6.4.3. Sappho, archaic Greek poet, inspired ancient poets and artists, including the vase painter from the Group of Polygnotos who depicted her on this red-figure vase, circa 440–430 B.C. Wikimedia, https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:NAMA_Sappho_lisant.jpg

6.4.4. A painting of the third-century Chinese emperor Shi Chong listening to the music of his concubine Lüzhu, famous composer of musical settings for poems. Hua Yan. 1732. Golden Valley Garden. Shanghai Museum. Wikimedia, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Shi_Chong#/media/File:Golden_Valley_Garden,_Hua_Yan.jpg

6.4.5. Troubadours, illustrated in The Olomouc Bible, Part I, 1417. Scientific library, Olomouc. Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Troubadours_berlin.jpg

6.4.6. A Romani man sitting in the desert with a drum in Pushkar, India. Unsplash, https://unsplash.com/photos/a-man-sitting-in-the-desert-with-a-drum-9Mj1qB3AgYk

6.4.7. Mural depicting a scene from Mongolian Epic of King Gesar, circa third century B.C. Wikimedia, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Epic_of_King_Gesar#/media/File:Gesar_Gruschke.jpg

6.4.8. Photo of a rock singer. Unsplash, https://plus.unsplash.com/premium_photo-1664302642672-d22412d44b1e?auto=format&fit=crop&q=80&w=875&ixlib=rb-4.0.3&ixid=M3wxMjA3fDB8MHxwaG90by1wYWdlfHx8fGVufDB8fHx8fA%3D%3D

6.4.9. Joan Baez and Bob Dylan, celebrated American folksongsters. Wikimedia, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Joan_Baez#/media/File:Joan_Baez_Bob_Dylan.jpg

6.4.10 Portrayal of the sixth-century Arabian poet and warrior Antarah ibn Shaddad, famous composer of orally transmitted poetry. Wikimedia, https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Antarah_ibn_Shaddad#/media/File:Antarah_on_horse.jpg

6.4.11 Ruth Finnegan, contemporary British-Irish oral poet. Photo by

Louise Langley.

6.4.12 Thomas Forest Bailey, an Australian performance poet. ©John Hunt.

6.4.13 Yoruba dancing singer and chorus. Photo by David J. Murray, 1972, University of Ibadan campus.

A second common type of poet could be called the free-lance and unattached practitioner. Admittedly the distinction can never be clear-cut; for even the most aggressively individualistic poet may form part of the power structure of a society, and what counts as an official role from the point of view of one group (say, a group of Ifa worshippers) may seem more like commercial self-interest from another (say, by certain Christian sects among the Yoruba). Nevertheless the rough distinction is useful: between poets who can rely on relatively permanent and accepted patronage as part of the political and religious establishment, and those who make a living by the effectiveness of their appeal to a succession of potential patrons.

Wandering poets and minstrels who live on their art and their wits are common in many societies. The mediaeval European poet-musicians are one well-known example, or the Moorish troubadours of modern Mauretania, and professional Tatar minstrels on the Central Asian steppes. It is also common in West African kingdoms: itinerant Hausa praise singers, unattached to an official court, can make a living by moving round the villages, picking on wealthy and powerful men to ‘praise’ in return for gifts in cash or kind. The attempt by the object of the songs to avoid paying the required largesse is likely to result in hurtful and derogatory ‘praise songs’, so the victim pays up. Similar power was held by the special ‘caste’ of poets in the Senegambia region known as griots. As holders of the hereditary rank of poet, these griots had special impunity: they had the right to insult anyone and—like the Moorish troubadours—to switch to out spoken abuse if they failed to get a reward of the expected size. Poets with this power are naturally feared (even despised) as well as admired and patronised, and hold an ambiguous position in society.

Not all free-lance poets take this aggressive route to their commercial objective. The Kirghiz minstrels work more subtly on a wealthy patron’s susceptibilities. Though they make a living by going from feast to feast, singing in honour of the host and for the delight of the guests, they take care to gauge the interest of the audience and compose effective and elaborate panegyrics to their patrons without appealing directly for largesse. It is worth quoting Radlov’s vivid description of these performances once more

One sees from a Kirghiz reciter that he loves to speak, and essays to make an impression on the circle of his hearers by elaborate strophes and well-turned expressions. It is obvious, too, on all sides that the listeners derive pleasure from well-ordered expressions, and can judge if a turn of phrase is well rounded off. Deep silence greets the reciter who knows how to arrest his audience. They sit with their head and shoulders bent forward and with eyes shining, and they drink in the words of the speaker; and every adroit expression, every witty play on words calls forth lively demonstrations of applause.

Since the minstrel wants to obtain the sympathy of the crowd, by which he is to gain not only fame, but also other advantages, he tries to colour his song according to the listeners who are surrounding him ... The sympathy of the hearers always spurs the minstrel to new efforts of strength, and it is by this sympathy that he knows how to adapt the song exactly to the temper of his circle of listeners. If rich and distinguished Kirghiz are present, he knows how to introduce panegyrics very skilfully on their families, and to sing of such episodes as he thinks will arouse the sympathy of distinguished people ... It is marvellous how the minstrel knows his public. I have myself witnessed how one of the sultans, during a song, sprang up suddenly and tore his silk overcoat from his shoulders, and flung it, cheering as he did so, as a present to the minstrel.

(Radlov, Proben v, pp. iii, xviiif, translated in Chadwick, III, 1940, pp. 179

and 184–5)

The Yugoslav poets such as Avdo Mededović do not make a direct appeal for reward in their singing. But such a singer can make, if not his full livelihood, at least some profit from his songs. In Avdo’s Yugoslavia, the singing of epic poetry formed the main entertainment of the adult male population in villages and small towns, and people were prepared to give the poet a reward in return for pleasure. The coffee houses in the towns were places where a singer could make money (as well as getting his audience to buy him drinks). During the period of Ramadan most Muslim coffee houses engaged a singer several months in advance, paying him a basic fee and organising a collection from the guests at the time of the performance (Lord, 1968a, pp. 14ff). So popular Yugoslav epic singers could attain semi-professional status and make some profit from time to time even though (except for those who were beggars) they were not professional singers in the sense of depending on their art for their livelihood.

The views such poets hold of their role vary a great deal. One would expect less stress to be laid on inspiration than in the case of poets with religious authority. This is so, in that the direct sanction of a poet acting as mouthpiece for the spirits in the authoritative religious system of the society is not here in question. But stress on the personal inspiration of the poet, even sometimes on his prophetic insight, is often found among free-lance poets, and is an aspect of the role which naturally adds to acceptability (and thus the likelihood of profit). This view may go alongside deliberate and professional training—which in some senses it might seem to contradict. Among the peoples of Central Asia, where the free-lance poet receives the most specialised training, it is believed that

the art of poetry is a kind of mysterious gift bestowed on the person of the singer by a prophetic call from on high. The biographical legend of the singer’s call is much like that of Caedmon, the first Anglo-Saxon poet, and has been taken for fact by the majority of the epic singers in Central Asia and South Siberia, both Turkic and Mongolian. The future manaschi, for example, is visited in a dream by the hero Manas and his forty followers, or by his son Semetei, or by another of his famous warriors, and is handed a musical instrument (the dombra) and commanded to sing of their deeds If the chosen singer disregards this call, he is visited by illness or severe misfortune, until he submits himself obediently to their will.

(Chadwick and Zhirmunsky, 1969, pp. 332–3)

Similarly the long practice and the knowledge of conventional runs and motifs that lie behind the art of an accomplished Kirghiz minstrel, is played down in his own account of his role where he stresses inspiration rather than deliberate art: ‘I can sing any song whatever; for God has implanted this gift of song in my heart. He gives me the word on my tongue, without my having to seek it. I have learnt none of my songs. All springs from my inner self’ (Radlov, Proben v, pp. xviff, translated in Chadwick, III, 1940, p. 182).

The training of these free-lance poets is seldom as formal as that sometimes arranged for official poets. It is common for singers to work at learning their craft in a personal and informal way. Potential Yugoslav singers like Avdo Mededović, for instance, begin by picking up the themes and stylistic conventions of the epic poems unconsciously by listening to others, then later start to try to sing for themselves. One singer explained how he learnt his art.

When I was a shepherd boy, they used to come for an evening to my house, or sometimes we would go to someone else’s for the evening, somewhere in the village. Then a singer would pick up the gusle, and I would listen to the song. The next day when I was with the flock, I would put the song together, word for word, without the gusle, but I would sing it from memory, word for word, just as the singer had sung it … Then I learned gradually to finger the instrument, and to fit the fingering to the words, and my fingers obeyed better and better … I didn’t sing among the men until I had perfected the song, but only among the young fellows in my circle (družina) not in front of my elders and betters.’

(Lord, 1968a, p. 21)

Quite often the Yugoslav neophyte chooses some particular singer, often his father or uncle or a well-known local singer, to follow most closely (Lord, 1968a, p. 22). This style of training tends to be informal and personal, but involves the deliberate ‘learning of a craft’.

Occasionally even free-lance poets had access to more formalised training, either through specific apprenticeships or in organised schools. Professional training was usual for instance, with Central Asian tale-singers. Zhirmunsky describes the system of training for Uzbek singers.

The most prominent singer-teachers had several pupils at a time. Training lasted for two or three years and was free of charge; the teacher provided his pupils with food and clothing, the pupils helped the teacher about the house.

The young singers listened to the tales of their teacher and accompanied him on his trips to villages. At first, under the teacher’s guidance, the pupils memorized the traditional passages of dastans and epic cliches, and at the same time learned how to recount the rest of the poem through their own improvisation. The end of the training was marked by a public examination: the pupil had to recite a whole dastan before a selected audience of tale-singers, after which he received the title of bakshy with the right to perform independently.

In the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, in the Samarkand district of the Uzbek Republic, especially famous for its tale-singers, there were two famous schools which were by far the most important centres of epic art: the schools of Bulungur and of Nuratin. Two outstanding folk-singers of our times belonged to these schools: Fazil Yuldashev (1873–1953) and Ergash Jumanbulbul-ogly (1870–1938). The Bulungur school was especially known for its heroic repertoire (Alpamysh), the Nuratin school for its performance of folk romances. Their styles of performance differed correspondingly: the style of the former was more severe and traditional, that of the latter more lyrical and ornamental in accordance with the nature of its romantic subjects. The relative artistic ‘modernism’ of the Nuratin school must probably be explained by the stronger influence written literature had over it, which can be traced back to Persian romantic epos through Tajik or Uzbek chap-books (kissa). Ergash and the majority of his teachers were literate people (as indicated by the word molla, usually added to their names), who had received fundamental Moslem elementary education.

The centre of the Nuratin school was Kurgan, a small village, the birthplace of Ergash. Despite the fact that only seven patriarchal ‘large families’ lived in the village, well over twenty folk-singers could be found there by the middle of the twentieth century, whose names have been recorded by the Uzbek folklorists on the information given by Ergash and the village elders. Ergash’s father and two uncles were outstanding tale-singers, as well as his two younger brothers and his great-grandmother, the woman tale-singer Tella-kampir. Such ‘dynasties of singers’ in which poetic talent was passed on from one generation to another, were well known among other Central Asiatic peoples.

(Chadwick and Zhirmunsky, 1969, pp. 330–1)

Free-lance poets are clearly of many different kinds, some hereditary, others not. Some depend on the direct approach in order to gain their main livelihood from poetry, others merely supplement their income by their art. Some rely on face-to-face performance; either drawing their public to hear them in situ or themselves travelling to their audience. Others, nowadays, use the radio as an alternative source of income and dissemination, like contemporary Somali poets and Mandinka griots in Africa, performing in both traditional and modern vein. Or, like Bob Dylan or the Beatles, they make use of the whole range of modern telecommunications: tapes, gramophone records, radio and television. What they all share is the recognition by their society—or of sufficient groups within it—that their craft is a specialist one, worthy of an individual’s spending many years to acquire and practise it, and deserving reward in whatever currency is locally offered. The value thus attached to the learning and practice of poetic art, and the consequent specialisation of the poet’s role, is not at all the picture of the organisation of oral literature sometimes held: of a communal, undifferentiated and anonymous activity with no opportunity for the development of the specialist individual poet, still less economic profit.

There are also poets—and perhaps this is the largest category—who are less specialised than those already discussed, and cannot be said to depend largely (and certainly not primarily) on their art, but who are nevertheless in some degree recognised as expert. Such poets often co-exist with more professional poets—the Hausa local and occasional singer for instance, practising in the same society as the official court poets and professional free-lance minstrels—while in societies or groups which do not have the poetic interest or the economic resources to support a distinct group of professional or semi-professional poets, these more occasional poets are the main exponents of the art.

Such poets often appear on ceremonial occasions when convention demands poetry and song, rather than on occasions specifically devoted to entertainment as such. These occasions are often crucial points in the social life cycle. Funerals often need music and poetry, and it is common for certain individuals recognised as particularly skilled—often but not always relatives—to be asked to assist in the mourning. Women dirge singers among the Akan of Ghana take on the responsibility for singing or intoning laments during public mourning. Though all Akan girls were expected to show some skill in composing and performing dirges to sing at relatives’ funerals, some women were recognised as particularly expert and had a larger repertoire than usual (Nketia, 1955, pp. 2ff). Again, the rituals of initiation or marriage often demand the assistance of an expert singer. Among the Limba of Sierra Leone there are no professional or near professional poets, but there are recognised experts specialising in different genres of song: songs for the stages of initiation (separately for male and female initiation); different types of funeral songs, each with their own names and styles; songs and declamations for memorial ceremonies; and songs to go with phases of the farming cycle throughout the year. For attending and performing at such ceremonies the expert poet/singer often receives some small fee or, at the least, generous hospitality from those organising the ceremony. With the more specialised poets (for in Limba culture some occasions, especially memorial ceremonies, demand greater expertise in their singers than others), large gifts may be forthcoming from the hosts.

Though poets like these are less highly specialised in terms of economic position or formally organised training, this does not mean that their art is less carefully structured or their poetic insight and detachment necessarily less. Take, for instance, the Luo nyatiti singer in East Africa. His speciality is the lament song, and he appears at funerals, which the Luo celebrate on a grand scale. He makes an appearance partly for social and personal reasons—relationship to the deceased or to help out a neighbour—and partly to make a collection from the large and admiring audience he is likely to find there. He composes and performs his songs for the occasion, drawing on accepted themes of honour and mourning for the deceased. Such songs are relatively conventional and soon forgotten; but sometimes a gifted singer, especially moved by sorrow, composes a song in advance with special care and intensity, devoting much time and concentration to it. The song may be so admired that he is asked to sing it again, after the funeral. When he does so, the poem often gains in detachment and depth—’being freed from the solemnity of a funeral [it] may rove from the fate of a particular individual to that of other people, and finally to the mystery of death itself’ (Anyumba, 1964, p. 190).

Again, Inuit poetry is famed for its insight and careful composition. And yet, among some groups of Inuits a measure of skill in composition was expected of everyone, and while expert poets were admired they did not hold official or professional status.

Every Inuit, therefore, whether man or woman, can not only sing and dance, but can even in some measure compose dance-songs. Distinction in this field ranks almost as high as distinction in hunting, for the man who can improvise an appropriate song for any special occasion, or at least adapt new words to an old song, is a very valuable adjunct to the community. Certain individuals naturally possess greater ability than others; their songs become the most popular and spread far and wide. But there are no professional song-makers, no men who make the composition of songs their main business in life.

(Roberts and Jenness, 1925, p. 12)

One has to set against this background the art of an outstanding poet like Orpingalik: a recognised and admired expert, but not economically or socially set apart by virtue of his skill.

Besides performing at recurrent ceremonies or creating songs for their own or others’ enjoyment, poets sometimes compose or perform in virtue of their membership of particular associations or interest groups in a society. Societies like the Yoruba hunters’ society, the Ghanaian military association of the Akan, or the Hopi flute societies have special music or poetry associated with them and one or more members who are skilled exponents of it. Here the poet performs largely in fulfilment of his social obligation as a member, though he may also derive some small material profit from his performance.

One of the roles often taken by the kind of occasional poets considered here is that of lead singer with a choral group, the position filled by the Black American poet Johnnie Smith. The soloist who takes the lead in antiphonal or responsorial patterns with a chorus can create poetry of real originality and depth, as we have seen. It may not be so clear that this context for the practice of poetry is extremely common. From work songs by prisoners in Texas, Indian road-makers, or Limba peasants in their rice fields, to wedding songs and dance songs and public entertainment throughout the world, lead singers perform and compose their poems, usually with little or no material recompense.

As amateurs, such poets often have no formal training. Their method of learning is likely to be through the informal process of watching and listening, and gradually absorbing the conventions appropriate to different genres of song in their differing contexts. A child growing up in Ireland is likely to hear the typical eight-line stanza and traditional tunes from his earliest years, and when he comes to sing himself to find it natural to compose and perform within these conventions. Similarly Yoruba children grow up with an increasing awareness—of the potentialities of ‘their tonal, metaphor-saturated language which in its ordinary prose form is never far from music in the aural impression it gives’ (Babalọla, 1966, p. v). A member of traditional Hawaiian culture is likely to be socialised from an early age into the kind of playing on words and complex figurative expression so important in his oral poetry.

These poets are not highly specialised professionals, and might not be noticed in an account of the economic and social division of labour. They tend to make the same kind of living as people around them—farmers, industrial workers, fishermen, building labourers, prisoners, housewives—and have no recognised status or high reward. But they perform an important role in publicising and realising the art of poetry. This is so in whatever society they practise, but most noticeably in cultures where professional and specialised poets are lacking.