7. Audience, context and function

©2025 Ruth Finnegan, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0428.07

Oral poetry is subject to the same disputes as written literature about its role in society. The same questions arise that have been battled over for so long in the analysis (sociological and other) of literature. What is the relationship between poetry and society? Does oral poetry ‘reflect’ the society in which it exists? Does it form a kind of mythical charter, supporting tradition and the status quo? Or is it a force for social change, even a democratic weapon in the hands of the people?

Large questions of this sort—the typical concerns of the sociology of literature—are abstract and elusive. They cannot be avoided in any sociological approach to poetry, but to move only on the level of such abstract and vague questions can lead to frustration—or to tautology. Instead of trying to tackle them directly and in general terms it seems more illuminating to turn first to a consideration of the occasions on which oral poetry is performed and to some of the more obvious purposes and effects involved, and then to return to the general theoretical problems. Otherwise, it is easy to fall into the trap of trying to start from first principles and deduce theoretical and would-be general propositions which sound elegant in the abstract, but operate at several removes from the actual practice of oral literature.

7.1 Some types of audience

It is as well to begin with some consideration of the audience to which a piece of literature is directed and delivered. This is a factor sometimes neglected or taken to be merely secondary, particularly in the kind of study which concentrates on the structure and effect of the text or on the model of poet/writer as individual genius. But the nature of the audience is surely an important factor in the creation and transmission of literature. This is noticeably so in oral literature, for here the typical context is delivery direct to an audience. The audience, even as listeners and spectators—but some times in a more active role—are directly involved in the realisation of the poem as literature in the moment of its performance. It is never a mere afterthought which can be ignored throughout the major part of a theoretical analysis of the functions and contexts of oral poetry.

If delivery to an audience is indeed the characteristic setting for oral poetry, it has to be conceded that there are also occasions where there is no audience, and the performance is a solitary one. This is less typical (and seldom or never happens in the better known case of oral prose narrative) but it does occur. The Nuer and Dinka pastoralists of the Southern Sudan sing solitary songs as they watch their cattle. The cattle are perhaps a kind of audience—to the Nuer and Dinka they are indeed closely approximated to human beings—and some of the songs of praise to particular oxen might be regarded in this way.

But these are also songs in which an individual can represent to himself his view of his own role and of ‘the whole world of beauty around him’ (Lienhardt, 1963, p. 828). Among the Dinka

a person may find entertainment in singing to himself while walking along the road, herding in the forest, or tethering the herds at home. During the season of cultivation, many people can be heard, each singing loudly in his own field. In the stillness of the night, a mother may be heard singing any song as a lullaby at the top of her voice

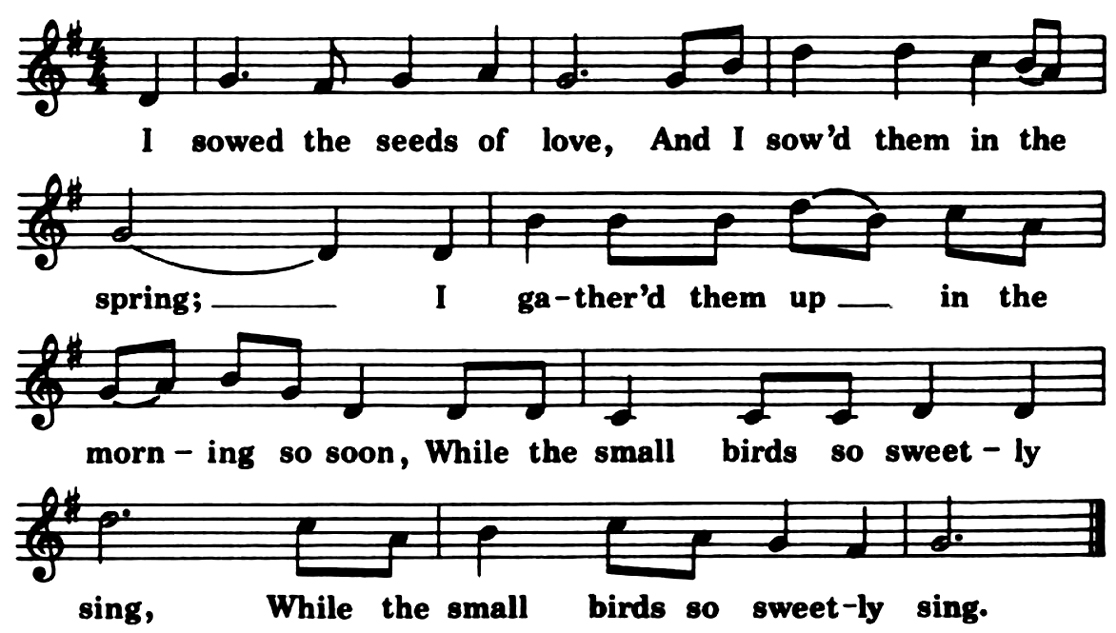

Again, the Inuit and Somali and Gilbertese and many others compose and practice songs in solitude as well as performing them in public. Solitary work songs are not at all uncommon (some lullabies may be a marginal case in the same category). There are songs for grinding corn, milking cows, working in the fields, paddling a boat—activities often carried out on one’s own. Again, there is the famous song which started Sharp off on his protracted collecting of English and American folk songs—when by chance he overheard the gardener John England quietly singing ’The Seeds of Love’ to himself as he mowed the vicarage lawn:

My garden was planted well

With flowers ev’rywhere;

And I had not the liberty to choose for myself

Of the flowers that I love dear. (bis)

The gard’ner was standing by;

And I asked him to choose for me.

He chose for me the violet, the lily and the pink,

But those I refused all three. (bis)

The violet I did not like,

Because it blooms so soon.

The lily and the pink I really overthink,

So I vow’d that I would wait till June. (bis)

In June there was a red rosebud,

And that is the flow’r for me.

I oftentimes have pluck’d that red rosebud

Till I gained the willow tree. (bis)

The willow tree will twist

And the willow tree will twine.

I oftentimes have wish’d I were in that young man’s arms

That once had the heart of mine. (bis)

Come all you false young men,

Do not leave me here to complain;

For the grass that has oftentimes been trampled under foot,

Give it time, it will rise up again,

Give it time, it will rise up again.

(quoted from Karpeles, 1973, pp. 93–4)

It is worth remembering these solitary settings, as a counter to the frequent emphasis on the public and community functions of oral literature. Sociologists of literature, in their reaction against the romantic models of the individual and, as it were, asocial poet, sometimes imply not only that the conventions and forms of literature are socially created but—an illegitimate but tempting next step—that all (oral) literature is attached to the public occasions of our lives. This is to forget the personal and contemplative side of literature—particularly characteristics of a number of these solitary songs. They remind us forcefully of the need to leave a place in our sociologies of literature for the human desire to formulate experience in pleasing words and to articulate ‘the secrets of the heart’ in aesthetic verbal form—and even if it is partly a matter of just warding off boredom in a long and tedious task, to do this with beauty and imagination.

In most performances of oral literature, however, an audience is involved. Sometimes the audience is really part of the performance itself, as in songs for choral singing, or is so at times, as when a lead singer performs partly as soloist, partly as leader in a joint singing with the audience. In such cases the audience participates directly in the performance. In other cases, which need to be distinguished, the occasion is a specialist one in that the demarcation between performer(s) and audience is clear, and the audience is functionally separate.

In discussing the functions and purposes of particular performances of oral poetry it can be useful to distinguish between these different kinds of audience. Even if they shade into each other, there is a difference in purpose and function between poetry delivered to and by a participatory audience and to an audience that is separate. Unfortunately this is just the kind of information often lacking in accounts of oral literature, so that the grander theories are often based on little detailed evidence.

But enough is known to delineate tentatively some common situations, as far as the audience is concerned. First, there is the situation where almost all those present are involved in the performance. This can be a total involvement, as when the oral poetry takes the form of joint choral singing or praying, but more often it is a matter of one (or perhaps two) people taking the lead and the rest of the group joining in responses or refrain. In this situation, as with oral art generally, there is no set list of aims and functions, and there seems to be almost infinite variability in the purposes such oral poetry can achieve for its joint performers and audience. There are, however, certain commonly recurring patterns.

In one of these, the joint performance of oral poetry expresses and consolidates the cohesiveness of the group of performers. This is obvious, for instance, with political ‘protest’ songs in contemporary America and Western Europe. Jointly sung verses like

We shall overcome

We shall overcome

Just like the tree that stands beside the water

We shall overcome

or the Swahili trade union song in East Africa

We do their work, bring them in their money

Clothes sprout on them through the efforts of the workers

…So let us unite and crush the employers

(Whiteley, 1964b, p. 221)

help to draw the participants together and make them aware of forming a ‘movement’ as well as articulating a particular view. Or it may be a matter of accepting membership in a jointly-working group, not necessarily opposed to outside bodies, like the daily hymn still chanted by Japanese workmen at the Matsushita Electric.

Let’s put our strength and mind together,

Doing our best to promote production,

Sending our goods to the people of the world,

Endlessly and continuously,

Like water gushing from a fountain.

Grow, industry, grow, grow, grow!

Harmony and sincerity!

Matsushita Electric!

(Macrae, 1975, p. 16)

Parallels are easy to find in religious as well as political contexts: Methodist hymn-singing, songs at political rallies, the joint performance of special initiation songs by groups of initiates, school songs, liturgical chanting, party political songs, and many others.

Work songs are a particularly clear example of the way in which oral poetry can create excitement and aesthetic pleasure in a participatory audience doing tedious or even painfully laborious work. This comes out in many descriptions of work songs and their functions. It is described particularly vividly in a recent collection of Hebridean ‘waulking’ songs—songs sung by women engaged in the heavy job of ‘waulking’ or beating home-made cloth to shrink it and give it an even texture. This was exhausting work, but the women were elated and light-hearted on these occasions. An eye-witness and participant from the end of the nineteenth century describes the scene

The web, saturated with the soapy water, was laid loosely upon [a makeshift table], and forthwith the work began. All seemed full of light-hearted gladness, and of bustle and latent excitement, and as each laid hold of the cloth, with their sleeves tucked up to the shoulders, one could see the amount of force they represented … These good women, with strong, willing hands, take hold of the web, and the work proceeds, slowly at first, but bye and bye, when the songs commence, the latent excitement bursts into a blaze.

(Mary MacKellar, quoted in MacCormick, 1969, p. 12)

This atmosphere of enjoyment and excitement in the midst of exhausting work must surely be ascribed at least in part to the songs. In this Hebridean case, the songs were often quite long and elaborate—not all work songs are short and crude. They included love songs, panegyric, and narrative poetry, sung sometimes in unison, sometimes with the group following and repeating a soloist’s words. One relatively short one is Far away I see the mist, translated from the Gaelic in MacCormick’s edition

Far away I see the mist,

I see Ben Beg, Ben More as well,

I see the dew on grassy tips.

Heard ye how my woe befell?

The traveller broke, the sail was rent,

Into the sea the mast it went,

The gallant boatmen further fared.

O would my father’s son were spared—

My mother’s son ‘tis makes my woe,

He breathes not in the wrack below,

No raiment now his body needs,

His foot no covering but the weeds

Hearty fellows be ye cheerful,

Let us prove the tavern’s hoard,

Fetch the glass and fill the measure,

Tossing bonnets round the board,

Banish sorrow unavailing,

The dead come not to life with wailing.

(MacCormick, 1969, p. 155)

Other work songs may have words which seem less elaborate, but give scope for originality and for enjoyment in a different way: they give a soloist the opportunity to improvise and adapt to the needs of the moment and the audience the chance to participate, whatever the new words initiated by the leader. Many of the songs designed to go with strictly timed work seem to be of this kind, the emphasis on repetition going well with the needs of a participating and working group. Lloyd quotes a typical ‘one-pull shanty’ of this kind

A Yankee ship came down the river.

Shallow, Shallow Brown.

A Yankee ship came down the river.

Shallow, Shallow Brown.

And who do you think was master of her?

Shallow, Shallow Brown.

And who do you think was master of her?

Shallow, Shallow Brown.

A Yankee mate and a limejuice skipper.

Shallow, Shallow Brown.

A Yankee mate and a limejuice skipper.

Shallow, Shallow Brown.

And what do you think they had for dinner?

Shallow, Shallow Brown.

And what do you think they had for dinner?

Shallow, Shallow Brown.

A parrot’s tail and monkey’s liver.

Shallow, Shallow Brown.

A parrot’s tail and monkey’s liver.

Shallow, Shallow Brown.

(Lloyd, 1967, p. 302)

In all these cases, the performers themselves are a kind of audience. Thus we must look in the first place at the influence on them for the direct effects of the performance of oral poetry—the way that it alleviates or rhythmically encourages and co-ordinates their work—rather than at the level of Society at large.

These poems with participatory audiences can enable the performers somehow to control their environment by capturing it in words. This is not the kind of point that can be proved or measured but it is hard to deny its significance. Jackson finds it in the songs which Texas prisoners sing as they labour:

The songs have one other function. I am not so sure of it that I can list it with the clear and definite group of functions above [supplying rhythm for work, helping to pass the time and providing an outlet for tensions and frustration], but I am interested enough in it to offer it here as a suggestion: the songs change the nature of the work by putting the work into the worker’s framework rather than the guards’. By incorporating the work with their song, by, in effect, co-opting something they are forced to do anyway, they make it theirs in a way it otherwise is not.

People contending with boredom or oppression or grief can control or come to terms with it by expressing it in the literary form of a poem. This must in a measure be true of all oral art (though it may apply somewhat differently to the poet and/or performer than to a merely listening public); with a participatory audience such significance is likely to be shared widely with the whole performing group. Again, therefore, it is worth asking who and of what kind the audience is.

In a number of oral poems, the participating singers are trying to control their environment in a more direct and active way. In a sense this is true of most religious songs for joint singing, particularly those with an emphasis on salvation or on the blessings of this or another world, but it is most noticeable in political songs. Election songs have become very important in modern Africa since the late 1950s. In these songs—which are sometimes written down but basically circulate by oral means—the singers often state their political policies, and in doing so both reinforce their own beliefs and ensure that all members of the movement have a mastery of their political aims and the means needed to achieve them. One infectious calypso in the 1962 elections in (then) Northern Rhodesia made sure that the voters understood the electoral machinery:

Upper roll voting papers will be green.

Lower roll voting papers will be pink.

|

Chorus |

Green paper goes in green box. Pink paper goes in pink box. |

(Mulford, 1964, pp. 134–5)

The leader-chorus pattern can be particularly effective in this context, and seems to be commonly used in elections when leaders wish to involve and stir up loyalty from a largely illiterate electorate. This comes out clearly in another election song from Northern Rhodesia, when the African National Congress took up ill-defined popular grievances and articulated them into definite aims in a party programme, carrying the participatory audiences with them. In this song the soloist sings in his own person and involves the audience all directly in the chorus.

One day, I stood by the road side.

I saw cars passing by.

As I looked inside the cars

I saw only white faces in them.

Following the cars were cyclists

With black faces.

They were poor Africans.

|

Refrain |

The Africans say, Give us, give us cars, too, Give us, give us our land That we may rule ourselves. |

I stood still but thinking

How and why it is that white faces

Travel by car while black faces travel by cycle.

At last I found out that it was that house,

The Parliamentary House that is composed of Europeans,

In other words, because this country is ruled by

White faces, these white faces do not want

Anything good for black faces.

(Rhodes, 1962, p. 19)

An extended form of the basically participatory audience occurs when a group is relatively self-sufficient in itself and has no sustained audience outside, but nevertheless throws out occasional comment for the benefit of someone outside the group who is assumed or invited to listen in at that point—a temporary and occasional audience. This is not uncommon. Texas prison work songs are primarily sung by and for the working prisoner group, who constitute the primary audience. But there are also references to guards or prison officials who appear to be listening. Similarly, political songs may be sung mainly as an expression of solidarity or joyful participation by a united group, but are also secondarily directed to occasional bystanders or assumed opponents: think, for instance, of the enthusiasm which Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament marchers in England in the late 1950s gave to the songs they had been singing all along when they found they were marching past potentially interested spectators; or the way Mau Mau supporters in Kenya stood up with extra fervour for the tune of the British National Anthem—their European opponents did not know that new subversive words in Kikuyu had been set to the tune, and merely remarked on the apparently increased loyalty of the Kikuyu to the crown (Leakey, 1954, pp. 72–3). Here again, one can only detect the possible functions of friendly teasing, protest, attempted confrontation, conscious persuasion, deception or aggressive solidarity by identifying the primary and the temporary audiences, and the likely effects on them.1

Another situation—overlapping with the first, but distinct enough to be noted as a commonly recurring pattern—occurs where the performance of oral poetry is part of a ceremony associated with one of the recognised turning-points of social and personal life. These are the performances that in many societies accompany weddings, funerals, coronations, initiations, the recognised events of the farming or pastoral year, even military rituals and legal proceedings. In societies with complex forms of specialisation affecting the arts, oral poetry at such ceremonies is sometimes by professionals or experts performing to clearly separate audiences; but in the situation I am distinguishing here songs are primarily performed by members of the social group immediately associated with the ceremony, with a larger public directly or indirectly involved and in some sense acting as audience. These amateur-dominated occasions are common even in our own society where professionalisation of the arts has in other contexts gone a long way.

One characteristic example can be taken from the ceremonies associated with death among the Limba of Sierra Leone. Here both the initial notification and mourning of the death and, later, the actual burial are marked by the lavish performance of oral poetry in the form of song. This is primarily initiated and led by a close woman relation of the dead man, supported by other women closely connected with the family. The songs go on for hours, and can be heard clearly through the rings of thatched huts that, till recently, constituted many Limba villages. The performance is like the participatory audience situation in one respect, for the group are singing for themselves—but differs in that they have an audience in the other inhabitants of the village who see and hear the singing going on in their midst.

This is not a trivial or theoretical difference, for the presence of this relatively permanent outside audience in the village is a significant factor in analyses of the function of the oral poetry which clusters round the fact of death, and plays a part in making it a public and not just a private event. The prevalence of song on such occasions serves to mark them out as special and significant in social life. Poetry has been said to italicise or put in inverted commas, and this is indeed one of its functions here. Just as special forms of dress or of ritual in other contexts set some act or occasion apart from everyday life, so does the performance of oral poetry here. It helps to give meaning and weight to the event both for the participants and also for the village as a whole—the audience who hear the mourning songs going on among them. Part of this whole process, italicised as it is by poetry, is the public recognition in and through the ceremony of the new social status of both deceased and bereaved.

In this way a whole range of functions can be performed through the delivery of oral poetry at a Limba death, some mainly affecting the participating singers, others essentially dependent on the wider audience. There is the sense of consolation and of significance experienced by the performers themselves, as well as the satisfaction of carrying out the due social obligations at this time of crisis for the group. For the village generally, the event is marked out with due solemnity and attention largely by virtue of the performance of oral poetry. It is claimed as a special responsibility by the close-knit group who take the lead, and also spread abroad as a significant event for the whole wider audience.

Another variant of this kind of situation occurs when the performance of poetry and song expresses or resolves hostilities between individuals or groups. At weddings, for instance, the relatives of bride and groom sometimes sing in turn, ‘getting at’ each other with both the opposing group and, presumably, the other attenders at the wedding acting as an audience; and rivalries between Kirghiz families often used to find expression in the aitys or public song competitions (Chadwick and Zhirmunsky, 1969, p. 329). Again, in Inuit song duels, long and biting poems of derision are composed and performed: ‘Little, sharp words, like the wooden splinters which I hack off with my axe’, as one poem puts it (quoted in Hoebel, 1972, p. 93). The singer most applauded is the winner—though he is likely to get little but prestige from his victory.

It is customary to identify the effects of such activities as expressing hostility (which may be latent rather than explicit) and rendering it more innocuous by ventilating it. But we need to bear in mind the situation and the likely mood and nature of the audience. One can surmise that entertainment and amusement are also likely to play a part in such performances.2 Indeed we know that the East Greenland Inuits carry on song duels for years ‘just for the fun of it’ (Hoebel, 1972, p. 93). Political songs are sometimes used in a kind of duel situation too. The 1959 federal elections in Western Nigeria were characterised by this kind of interchange. The supporters of the NCNC party (symbolised by a cock) and the Action Group (a palm tree) sang against each other, mocking each others’ symbols.

Action Group

The cock is sweet with rice,

If one could get a little oil

With a little salt

And a couple of onions—

O, the cock is so sweet with rice.

NCNC

The Palm tree grows in the far bush.

Nobody allows the leper to build his house in the town.

The palm tree grows in the far bush…

Action Group

Never mind how many cocks there are.

Even twenty or thirty of them will be contained

In a single chicken basket,

Made from the palm tree.

(Beier, 1960, pp. 66–7)

Sometimes the primary audience consists basically of a single person. This is the third common situation. It can be illustrated by Merriam’s account of Bashi singers in the Kivu area of the Congo. Girls working on a plantation were dissatisfied with their conditions, but did not feel able to raise this directly with their employer. But they did seize the opportunity of singing a song about their grievances in his presence, and so the complaints they did not wish to raise formally were expressed indirectly.

We have finished our work. Before, we used to get oil; now we don’t get it. Why has Bwana stopped giving us oil? We don’t understand. If he doesn’t give us oil, we will leave and go to work for the Catholic Fathers. There we can do little work and have plenty of oil. So we are waiting to see whether Bwana X will give oil. Be careful! If we don’t get oil, we won’t work here.

(Merriam, 1954, pp. 51–2)

The convention by which things can be said in a poetic medium that could not be uttered in a more ‘direct’ form, is a widespread and interesting one. It is as if expression in poetry takes the sting out of the communication and removes it from the ‘real’ social arena. And yet, of course, it does not—for the communication still takes place. It is a curious example of the conventions that surround various forms of communication in society, where, even if the overt ‘content’ remains the same, the form radically affects the way it is received—whether or not it is regarded as a confrontation, for example.

The way that expression in songs and poems can be conventionally regarded as not offering the same direct challenge as prose communication is very widely documented. In the Texas prison songs, references—even derogatory references—to prison officials are regarded as acceptable in song even when they could never be articulated directly in what, for this purpose, is classified as ‘real life’. This is a common pattern throughout the American South, where it is a long-standing convention for Black Americans to express in song insult and hostility that could not be spoken (Jackson, 1972, pp. 126, 193). Again, social conventions often make it difficult for complaints by a wife about her husband (or, perhaps less often, the other way round) to be expressed directly, but are not infrequently voiced in song. A Maori woman, for instance, who was accused of being lazy by her husband often retaliated by composing a song about it (Best, 1924, p. 158) while among the Mapuche of Chile, where women normally held a subordinate role, it was accepted that wives blew off steam about marital problems in a song. It was incumbent on the husband whose faults were thus publicised to take it in good part. This comes out in the following Mapuche exchange, when the wife in her song publicly hints that her husband is a thief and wrong-doer.

Wife’s song

I dreamed of a fox.

It was bad for me,

but there is no help for it now,

since that is the way it turned out to be.

Man’s reply

Things are not as bad as you have said,

my little cousin (wife).

If I have done anything wrong, it’s all over now.

Only on you do my eyes gaze.

Let everything bad be ended.

Wife’s counter-reply

Just now, dear cousin (husband),

I have heard what I wanted to hear from your own lips.

Now my heart is restored to its proper place.

If you do what is right,

I shall love you more than ever.

(Titiev, 1949, pp. 8–9)

Sometimes the presence of a secondary audience, as it were, can be important in these cases. The song or poem may be directly against one person as the primary audience and the one the poem is designed to affect, but the presence of a wider audience who overhear the communication can also be significant—as in the Mapuche case just quoted where interested auditors joined the wife in pressing her husband to mend his ways. The secondary audience forms the background of potential support against which the singer or speaker tries to reach the primary target. When two Yoruba women have quarrelled, they vent their enmity by singing aloud at each other in public places like the washing area where other women will hear them (Mabogunje, 1958, p. 35). Again, the verse directed against the Chopi youth trying to seduce a young girl was designed to stir up public opinion as well as express a rebuke in the acceptable medium of poetry.

We see you!

We know you are leading that child astray…

We know you!

(Tracey, 1948, p. 29)

It has frequently been pointed out that one way in which subjects can exert sanctions against their rulers is through poetry. This too gives the possibility of saying things which are normally unacceptable (often with additional conventional requirements about the permitted speaker and occasion). Thus the Somali poet could address a poem to a local sultan who was trying to assume dictatorial powers; with the backing of the wider audience of the poem, it finally led to the sultan’s deposition.

The vicissitudes of the world, oh ‘Olaad, are like the clouds of the seasons

Autumn weather and spring weather come after each other in turn ...

When fortune places a man even on the mere hem of her robe, he quickly becomes proud and overbearing

A small milking vessel, when filled to the brim, soon overflows

(Andrzejewski, 1963, p. 24)

A similar device was used by Yoruba singers to give instructions to the local Mayor of Lagos. Cast in the form of a piece of popular dance music and ostensibly praising the Mayor Olorun Nimbe, it gives firm advice about the way he should act.

I am greeting you, Mayor of Lagos,

Mayor of Lagos, Olorun Nimbe,

Look after Lagos carefully.

As we pick up a yam pounder with care,

As we pick up a grinding stone with care,

As we pick up a child with care,

So may you handle Lagos with care.

(Beier, 1956, p. 28)

Parallels to this type of communication are very widespread, from the Chopi and Hottentot poetic attacks on chiefs in Africa (see Finnegan, 1970, p. 273ff) to the early Irish poets’ satires on rulers, which were thought powerful enough to raise blemishes on the victim’s face—and ‘a man with a blemish shall not reign’ (Knott and Murphy, 1967, p. 79).

Praise of rulers and other patrons can be regarded in the same light. The poem is directed at one known person (occasionally a small group), who forms the primary target, but with a larger audience who are expected to hear and applaud. Here again sentiments can be expressed not normally considered appropriate in straightforward prose or the medium of everyday conversation—the lengthy and hyperbolic praises involved would be too fulsome or too tedious to be readily acceptable in a more ‘ordinary’ medium—for instance, this extract from the panegyric of the famous Zulu king Shaka:

…He who is alone like the sun;

He who bored an opening through the Chube clan,

He came with Mvakela son of Dlaba,

He came with Maqobo son of Dlaba,

He came with Khwababa son of Dlaba,

He came with Duluzana from among the Chubes…

(Cope, 1968, p. 104)

and so on through 450 lines.

This is beautiful and elevating in poetry and doubtless did much to commend the poet to the ruler, to fortify his own pride in his actions, and to stir up and consolidate the admiration of the attendant audience for their ruler—but in everyday conversation it is less likely to be appealing or effective. Similar situations are found all over the world where court poets flourish. The primary audience may be the ruler, but the poems are given meaning and effect by the wider audience of those present during his performance.

In all these contexts the poet’s communication with his intended primary audience is facilitated by the common convention that sentiments can be communicated through poetry that would be impertinent, boring or embarrassing in more direct form. Lovers exchanging passionate declarations of love or invitations to secret meetings, children mocking a teacher, beggars importuning wealthy passers-by, or wandering singers, like the Hausa, veiling aggressive attacks and abusive demands for payments in the acceptable medium of poetry—all perform in a context made possible by the social convention that communication in poetry is not just abuse, or immodesty, or flagrant begging, but an acceptable and pleasing social activity.

With situations of these kinds, it is easy to see the social function they perform in terms of social pressures and sanctions against rulers and others, or subtle and oblique communication, and these functions have frequently been commented on. But when one takes the contexts and audiences into account, especially the secondary audiences often involved, it becomes obvious that there are also elements of aesthetic pleasure and sheer enjoyment. It is, after all, the aesthetic setting which makes this type of special communication feasible, and clothing the message in appealing or magnificent or witty language gives spice and effect to the whole occasion.

This aesthetic aspect is usually taken for granted, and left for us to guess at from a knowledge of the general context. A few writers have commented on it directly. It comes out clearly, for instance, in Green’s description of Ibo singers. Here songs are used as a direct sanction to coerce an offender. One woman had refused to pay a fine levied on her for a false accusation. The other women went in a group to her house to sing and dance against her. The songs were explicitly obscene—another instance of poetry as a medium for the normally unsayable—and had the effect of making the offender pay her fine. So far, the aim and effect of the songs are clear. But this was not all there was to it; sheer enjoyment was also involved, both for the participatory audience and for any bystanders.

As for the women, I never saw them so spirited. They were having a night out and they were heartily enjoying it and there was a speed and energy about everything they did that gave a distinctive quality to the episode. It was also the only occasion in the village that struck one as obscene in the intention of the people themselves. Mixed with what seemed genuine amusement there was much uncontrolled, abandoned laughter. There was a suggestion of consciously kicking over the traces about the whole affair.

(Green, 1964, pp. 202–3)3

One other situation is worth drawing attention to. Here the audience is clearly and specifically separate from the performer(s) and is present mainly, or largely, to listen to a performance. This kind of situation is worth special attention, for amidst the frequent comments on the functional aspects of oral art and its role in an actual social context, it is easy to forget that the performance is sometimes a specialised activity, explicitly valued as an end, with a special time and place set aside for its enjoyment.

Contrary to the once-prevalent theories about the communal or utilitarian nature of art in non-industrial societies (or elsewhere), such specialized situations are fairly common. It is clear in a number of accounts that enjoyment or entertainment were from the audience’s point of view the main purpose of oral performances. Take, for instance, Vambéry’s description of Turkoman performances by the heroic poets, bakhshi, in the nineteenth century:

On festal occasions, or during the evening entertainments, some Bakhshi used to recite the verses of Makhdumkulil. When I was in Etrek, one of these troubadours had his tent close to our own; and as he paid us a visit of an evening, bringing his instrument with him, there flocked around him the young men of the vicinity, whom he was constrained to treat with some of his heroic lays. His singing consisted of certain forced guttural sounds, which we might rather take for a rattle than a song, and which he accompanied at first with gentle touches of the strings, but afterwards, as he became excited, with wilder strokes upon the instrument. The hotter the battle, the fiercer grew the ardour of the singer and the enthusiasm of his youthful listeners; and really the scene assumed the appearance of a romance, when the young nomads, uttering deep groans, hurled their caps to the ground, and dashed their hands in a passion through the curls of their hair, just as if they were furious to combat with themselves.

(Vambéry, Travels, p. 322, quoted in Chadwick, III, 1940, p. 175)

Kara-Kirghiz singers too were valued for their power to stir the enthusiasm and admiration of the audience, who came specially to hear them. The Russian traveller Venyukov heard one of the most famous of these minstrels in 1860:

He every evening attracted round him a crowd of gaping admirers, who greedily listened to his stories and songs. His imagination was remarkably fertile in creating feats for his hero—the son of some Khan—and took most daring flights into the regions of marvel. The greater part of the rapturous recitation was improvised by him as he proceeded, the subject alone being borrowed usually from some tradition. His wonderfully correct intonation, which enabled every one who even did not understand the words to guess their meaning, and the pathos and fire which he skilfully imparted to his strain, showed that he was justly entitled to the admiration of the Kirghizes as their chief bard!

(quoted in Chadwick, III, 1940, p. 179)

The details of such occasions naturally vary, but the general pattern, in which a poet addresses himself specifically to an audience who are present to enjoy his poetry is a common one. The audience may at the same time be drinking, dancing, or otherwise relaxing—but the poetry being delivered in speech or song is often a central part of the entertainment involved. This sort of occasion occurs all over the world, from the ‘singing pubs’ or fireside literary circles of Ireland (Delargy, 1945, p. 192) to home gatherings in the Yugoslav countryside where men come from the various families around to hear an epic singer perform, or the coffee houses in Yugoslav towns where the minstrel must please his audience with exciting and well-sung heroic tales so as to reap a reward from listeners who have come into town for the market (Lord, 1968a, pp. 14–15). The same general pattern is found in the fairly common contexts of poetic competitions, where single poets or contending groups of performers compete to gain greater applause than their opponents from the audience and thus be declared the winner. Such competitions are found all over the world, from Central Asia and Japan to Africa and Polynesia.

In the case of a performer like Avdo Mededović or the Kirghiz ‘chief bard’ it is easy to see such occasions as primarily ‘aesthetic’, comparable to concerts or poetry recitals in our own culture where the purpose is the appreciation of an artistic performance. But it is not always easy to delimit the specific purpose of a set occasion (even in our own culture people have a variety of reasons for attending such performances), still less all the possible functions. Certainly, many of the occasions on which there is a specific audience assembled to hear one or more performers are, arguably, describable as specialised and deliberate ‘artistic occasions’. But there are also contexts where this aim may not be specifically differentiated from others, or where the aim is overtly of some other kind—religious say, or political. Hearing the chanted sermons in the American South described by Rosenberg, the outsider may wish to analyse the aesthetic and poetic characteristics of the chants, but the audience comes for religious reasons, ‘to hear the Word of God’. Or take the Northern Rhodesia party songs again. In the election campaign meetings of 1962, songs formed a recognised and popular part of mass meetings, and were, we assume, one inducement to large numbers to attend. Mulford describes a typical rally by the UNIP party

Thousands were packed in an enormous semi-circle around the large official platform constructed by the youth brigade on one of the huge ant hills. Other ant hills nearby swarmed with observers seeking a better view of the speakers. Hundreds of small flags in UNIP’s colours were strung above the crowd. Youth brigade members, known as ‘Zambia policemen’ and wearing lion skin hats, acted as stewards and controlled the crowds when party officials arrived or departed. UNIP’s jazz band played an occasional calypso or jive tune, and between each speech, small choirs sang political songs praising UNIP and its leaders.

Kaunda will politically get Africans freed from the English,

Who treat us unfairly and beat us daily.

UNIP as an organization does not stay in one place.

It moves to various kinds of places and peoples,

Letting them know the difficulties with which we are faced.

These whites are only paving the way for us,

So that we come and rule ourselves smoothly.

(Mulford, 1964, pp. 133–4)

In these situations, obviously, different effects can be accomplished by the poems and their performance: economic transactions (between audience and poet), expressions of hostility and consequent consolidation of contending groups, the transmission of religious forms or political view points, and so on. But from the point of view of the audience, the central aim is surely enjoyment. This need not be categorised in reductive terms as ‘mere entertainment’. This enjoyment embraces, for instance, the delight of Yugoslav audiences in the beauty of diction, delineation of character and evocation of high heroic deeds in a glorious and remote world by a minstrel like the great Yugoslav singer Avdo Mededović, or the satisfaction of Tongan islanders in unravelling the skilful metaphors with which contending bards assailed each others’ work, poems ‘laden with two or three strata of meaning’ (Luomala, 1955, p. 33), or the Marquesans’ appreciation of the intellectual contests of their own bards (ibid. p. 4, 8) or Kirghiz audiences’ delight in the polished diction of their minstrels where ‘every adroit expression, every witty play on words calls forth lively demonstrations of applause’ (Radlov, Proben, v, p. iii translated in Chadwick, III, 1940, p. 179). It is tempting in the search for the more abstruse ‘functions of art’ to neglect this kind of reaction and to brush aside, as too obvious to mention, the element of enjoyment and aesthetic appreciation. But to play down this aspect is to forget what must often be the primary interest of the audience.

These patterns of audience involvement bring home to us how important it is to ask questions about the nature and wishes of the audience to which a performance is directed. As with the recurring patterns of relationship between the role and activities of poets (above chapter 6), it would be a mistake to regard these common situations as separate and distinctive categories, or to erect them into theoretical typologies. There is plenty of overlap between the various situations delineated here, and those discussed are not an exhaustive list. All that is claimed is that it is illuminating to see that these are commonly occurring patterns, and that we need to identify the nature and situation of the audience in any analysis of the supposed ‘functions’ of any particular oral poetry.

7.2 The effect and the composition of audiences

The audience, it is now clear, affects the nature and purpose of performances of oral poetry in various ways. There are also two further questions worth asking: first, the direct effect which the audience may have on the poem at the actual time of performance; and second, the way the audience is itself selected.

As for the first, it is clear that audiences do often have an effect on the form and delivery of a poem. Of course, the nature of the likely audience influences all literature, but with oral literature there is the additional factor that members of the audience can take a direct part in the performance. This is obvious in the case of a participatory audience, or in the fairly frequent situation where a basically specialist solo performance is supplemented by the audience joining in the choruses or responses. There are also the cases where (as described in the chapter on composition) the restiveness or receptiveness of the audience affects the length or brevity of the delivery of a piece, or when the presence of certain individuals or groups leads a poet to gear his presentation of, say, events or genealogies to please them. In mediaeval Chinese ballad singing, audience-reaction was a significant part of the whole performance.

In the case of a Chinese story-teller ballad, the relationship between the originator and his audience is so essential and so tight that the existence and the shape of the production is directly dependent on the audience’s reaction. The interpretation gap between the creator and the reader has, in the case of Chinese story-teller literature, disappeared because the story-teller is forced by his profession to foresee his client’s expectations, wishes, and moods and to react to them, though they may be very changeable indeed. Either the story teller knows and reacts to his audience with skill, is successful, and earns his livelihood, or he misjudges them and fails. So in a certain sense audience reaction is not a passive but an active, creative factor in the Chinese story-telling.

(Doleželová-Velingerová and Crump, 1971, p. 13)

This involvement by the audience—even when the audience is primarily separate rather than participatory—sometimes extends to verbal prompting or objections by individual listeners. In Yoruba hunters’ songs (ijala), for instance, other expert ijala performers are often present. If they think the performer is not singing properly, they will cut in with a correction, beginning with a formula like:

You have told a lie, you are hawking loaves of lies.

You have mistaken a seller of àbàri for a seller of ègbo4

Listen to the correct version now.

Your version is wrong.

For the sake of the future, that it may be good.

In self-defence, a criticised ijala-chanter would brazenly say:

It all happened in the presence of people of my age.

I was an eyewitness of the incident;

Although I was not an elder then,

I was past the age of childhood.

Alternatively the chanter may reply by pleading that the others should respect his integrity.

Let not the civet-cat trespass on the cane rat’s track.

Let the cane rat avoid trespassing on the civet-cat’s path.

Let each animal follow the smooth stretch of its own road.

Such cases are interesting for what they show about the old theories about the possibly ‘communal’ nature of oral literature, and the part played by the ‘folk’ in its creation. There are reasons for abandoning parts of these theories, but there remains the genuine point that, with oral literature, the audience can take a direct part in its realisation. There are participatory audiences, for one thing, and then, over and above the way in which any face-to-face audience is likely to affect the manner and content of the poetry, there is the accepted convention in some contexts that members of the audience can intervene directly. In the sense of audience involvement, oral literature is more open than written literature to direct group influence on what might otherwise be considered the individual creative genius of the poet.

But one must not labour the point overmuch. In particular, those who have seen this potential involvement of the audience as a sign of the ‘democratic’ or’ popular’ nature of oral poetry are assuming that they know the precise nature of the audiences involved—and that these are indeed ‘popular’. This leads to the second question: the nature and extent of the audiences.

It is sometimes assumed, rather romantically, that the audiences of oral poetry are necessarily ‘popular’—the public at large—and that knowledge of a particular oral literature is widely diffused through the society. This is not true (see chapter 6, section 3). For though oral literature cannot have the ‘private’ and ‘silent’ aspect found in the circulation of written literature, and is always ‘public’ and ‘hearable’ by others in its very essence, this does not mean that in a given case the audiences are unrestricted and attendance open to all in the society. In fact, occasions and performers are conditioned by convention, and audiences too are restricted in constitution and distribution.

This is so even with the simplest participatory songs. The work-songs of one occupational group are not always known by others; initiation songs are often separated into those for men and those for women; and adults usually do not know the words of the latest craze among children’s songs. Similarly, praise poetry may be heard widely throughout a society, but the rich and powerful to whom it is primarily directed are likely to hear it more frequently. Again, how far specialist poets are prepared to make a living by travelling throughout the country and how far they attach themselves to the main centres of wealth and urbanism obviously decides which audiences are likely to benefit from their performances.

The frequent comment that poetry can act as a social sanction by the people against their rulers looks different if—as is sometimes the case—these poems are delivered primarily by poets, themselves members of the establishment, to audiences largely made up of those permanently associated with the court. We often have little evidence on the question of how wide an audience has access to such poetry. It is easy to repeat, for instance, the common claim that ballads speak for ‘the people’ (e.g. Hodgart, 1965, p. 11)—but which people? when? and is the meaning and role of the ballads the same for all sections of the potential audience?

Again, to claim that certain songs are ‘for the folk’ inevitably requires a definition of ‘the folk’. For a collector like Greenway ‘the folk’ of modern industrial life are no longer agricultural labourers but modern industrial workers—but he explicitly excludes college students (Greenway, 1953, p. 9); so the provenance of his ‘folk songs’ is not so wide as one might at first suppose. Similarly, the emphasis in the United States on ‘protest’ and ‘left-wing’ songs do not of themselves demonstrate ‘democratic’ or ‘popular’ functions for such poetry: to prove this one would have to consider both the performers and the audiences involved, and show that the circulation was not confined to limited social groups. It is not unfair to quote the cynical verse commenting on the political movement associated with ‘protest songs’ and The Peoples’ Song Book

Their motives are pure, their material is corny,

But their spirit will never be broke.

And they go right on in their great noble crusade—

Of teaching folk-songs to the folk.

(Quoted in Wilgus, 1959, p. 229)

Even with the apparently public and open transmission of certain types of oral poetry by modern mass media, audiences may in practice be restricted, and different sections will react differently to the same performances. The oral poems classified as ‘pop songs’ in Britain, for instance, are listened to primarily by one age group, and ignored or actively repudiated by most others. This may be self-selection rather than arbitrary restriction by an outside force, but it imposes as real a limitation on the likely audience. It is a selective process fostered and maintained by social expectations—conventions which may be more effective (because voluntary) than an official order or government censorship.

Similarly, it is easy to make a contrast between the obscurity (hence restricted circulation) of certain written literature and the more open nature of oral literature, whose successful performance depends on the audience appreciating and understanding. This is true. But even primarily non-literate audiences can consist of initiates and intellectuals, and the circulation of oral poetry may sometimes take place within circumscribed limits. In a general way many initiation songs are of this kind—like the Makua song-riddles, full of allusions that only initiates can understand—and so are a number of religious poems whose esoteric content and language confine them to an audience of devotees. This type of restriction was taken very seriously in parts of India, where there was ‘the rule that no non-Brahman should recite or hear the Vedas, and this was and is respected by the other castes’ (Staal, 1961, p. 33). Similarly, among the Native Australians of Central Australia, the sacred songs could be sung only by men, and in some cases ‘the women and children were … not permitted even to listen to them on pain of death’ (Strehlow, 1971, p. 637). Again, some poets may use esoteric or even foreign language unknown to their audience—like the use of Latin over many centuries, the minstrel use of Mandingo for song over wide areas of non-Mandingo West Africa, or the ‘special language’ used by early Irish poets. Even when a formally different language is not used, full understanding of the meaning of certain types of poetry is sometimes deliberately restricted. This was typical of the aristocratic poetry of Polynesia, where the riddling and figurative form of expression was ‘to exalt language above the comprehension of the common people, either by obscurity, through ellipsis and allusion, or by saying one thing and meaning another’ (Beckwith, 1919, p. 41). Strehlow explains how this was a common feature of Aranda poetry in Central Australia:

The special form of Aranda verse increased its effect. Because of the varying ages of the singers it was an advantage that the words sung should be obscure, so that young untried men, who had only recently been initiated, could not from the singing of licentious verses draw the wrong and unwarranted conclusion that they had the approval of their tribal elders to satisfy their drives in real life as well as in a symbolic ceremony. Most of the particularly ‘dangerous’ verses of this sort were, as I have pointed out earlier, hidden from the young men; others had harmless meanings attributed to them when they were being explained to the untried and the immature. The full meaning of each verse had to be brought out by the accompanying oral tradition; and its old guardians saw to it that no one was told the full truth until his personal conduct had proved him to be a man amenable to strict discipline. Clearly, ‘censorship’ to protect the morals of the young was not unknown even in a ‘primitive’ community!

So oral poetry is not necessarily widely and democratically diffused through the people; its distribution and audience may in practice be restricted, and its form such as to strengthen the current power structure of society rather than undermine it.

Oral literature does often circulate more publicly and openly than much written literature. Against this, one must set the mass production of printed books to which it is possible in principle for huge numbers of people to have access; contrast this in turn with the restricted audiences to whom (apart from the recent development of radio and television) oral poetry tends to be delivered. Oral literature is dependent for its realisation on performers and audiences, and these are often more restricted than the more naive views of non-industrial societies as essentially ‘communal’ and ‘open’ would have us believe. Here again it is essential to look both at the type of performers and poets involved and at the nature of the audience in each case.

7.3 The purpose and meaning of poetry: local theories

A further point worth noting is the significance of local interpretations, of a poem or of poetry generally. This too needs to be considered, not just the role of poetry in general terms, abstracted from the particularities of the culture in which it occurs.

People trying to analyse the role of poetry have often been tempted to concentrate on objective-sounding terms like ‘function’ or ‘effects’. The focus has thus been the consequences which, seen from the outside, poetry (or poetic activity) can be seen to have for the society in general, or for particular groups or individuals within it—whether or not these consequences are locally perceived as such. Sociologists have been drawn more to this ‘external’ aspect—particularly functional anthropologists—while exploration of the local interpretations of the meaning of poetry or the local philosophy of art tend to be taken up by those interested in ‘the arts’. The dichotomy between these approaches has never been complete, and many sociologists and anthropologists have seen the need to understand local interpretations, whether of poetry or anything else. Recently there has been increasing awareness among sociologists of the importance of the ‘meanings’ that people attach to their actions and to the world around them, and a renewed sense that to look at the role of any social action only from the outside in so-called ‘objective’ or ‘generalisable’ terms is seriously to diminish our appreciation of the complexity of reality and of the resources of the human imagination.

It is thus relevant at this point to say something about local views of the nature and purpose of poetry. This is, by definition, not a subject that can be treated in general terms. The whole point is the uniqueness of many such views, bound in as they are with local religious beliefs, particular social experience and symbolism, local theories of psychology, and so on. All I can do here is to illustrate some of the kinds of views that are held on these topics. But even a few examples will help to convey how significant this can be for the study of a particular oral poetry. It also establishes, contrary to some older assumptions, that non-literate like literate people can reflect self-consciously on the nature and purpose of poetry.

The genesis of poetry is often seen in terms of ‘inspiration’—though where this inspiration is believed to come from varies. This is obviously relevant to the understanding of local views about the nature—and hence the purpose—of poetry and of particular forms. Thus the outside analyst may note the ‘oral-formulaic’ structure of Black American chanted sermons, or their integrative function for the audience; but for the congregation itself ‘when the preacher is giving a sermon the words come directly from God’ (Rosenberg, 1970a, pp. 8–9). This conviction obviously affects how these chanted poetic sermons are received by their audience and thus their specific effect. Again, the members of the hunters’ society among the Yoruba of Nigeria regard the god Ogun as their special patron, and many of their ijala (or hunting) songs are connected with the worship of Ogun as well as with popular entertainment. The views of participants in this society about the nature and genesis of poetry are consonant with this background, as will be clear from the following comments on ijala songs by members of the society

No hunter can validly claim the authorship of an ijala piece which he is the first to chant. The god Ogun is the source and author of all ijala chants; every ijala artist is merely Ogun’s mouthpiece.

Certainly there are new ijala chants created by expert ijala-chanters from time to time. The process of composition is intuitive and inspirational; it springs from the innate talents of the artist. The spirit, the genie (alujannu) of ijala-chanting teaches a master chanter new ijala pieces to chant. The god Ogun himself is ever present with a master chanter to teach him new ijala.

It is often through inspiration that ijala artists compose new ijala chants. They receive tuition from the god Ogun in dreams or trances.

(Quoted in Babalọla, 1966, pp. 46–7)

Songs which are believed to derive from a divine source of this kind are likely to affect their audience otherwise than songs seen as primarily due to the personal gifts of an individual singer.

Inspiration can also be through a dream. One of the most famous Inuit poems—the Dead man’s song—is presented as if by the dead man himself, but ‘dreamed by one who is alive’, by the poet Paulinaoq. This interpretation of the genesis of songs is strongly held by the Toda of southern India: Emeneau includes a whole section of ‘Songs dreamed’ in his collection. In one case a woman ‘dreamed’ her song in which two dead men speak. In another a man was said to have dreamed a poem about a mother lamenting her forced departure from her child (she had died when her baby was only one month old, and the dreamer’s wife was caring for the child). The dreamer awoke from his dream before the song was finished; but, though it was the middle of the night, he roused everyone to hear him sing the 34-line song

O my child!

O child that does not know how to talk! O child that does not know the places! …

The child that I bore is crying…

I have sat, forsaking my child.

I have sat, forsaking my buffaloes.

Any understanding of the effect of this song as it was sung and of the nature of poetic composition as understood by the Toda must take account of the assumption that songs can on occasion be ‘dreamt’ and can provide a channel of communication with the dead.

Dreams are also thought significant for poetry among the Native Australians of Arnhem Land. Here the so-called ‘gossip songs’ by contemporary oral poets are composed and delivered on the understanding that ‘the songman merely repeats songs given to him in dreams by his personal spirit familiar’—even though in practice a good songman is naturally ‘alert to all the gossip and song potential for miles around’ (Berndt, 1973, pp. 48–9; 1964, p. 318). The sacred Arnhem Land song cycles, too, are believed to come originally from the mythical time of the ‘Eternal Dreaming’, and the poet is seen as in direct contact with the ancestral spirits in dream: it is from them that he ‘receives’ the words and rhythms. ‘The songs are the echo of those first sung by the Ancestral Beings: the spirit of the echo goes on through timeless space, and when we sing, we take up the echo and make sound’ (Berndt, 1952, p. 62). It is partly because of this interpretation that performance can have the effect that Berndt describes.

The songs, since they ‘belong’ to the divine Beings, give the ritual an atmosphere of reality, in the sense of veracity, and a deep consciousness of affiliation and continuity with these Beings themselves. Sacred songs, sung on the ceremonial ground by hereditary leaders, in conjunction with ritual and dancing, and in the presence of religious symbols or emblems, vividly reflect and re-inspire the religious emotions of all who hear them.

(ibid. p. 62)

Inspiration does not always come from outside the poet. Sometimes his own powers are stressed; ‘not all men can make songs’, as the Hopi poet Koianimptiwa pointed out (Curtis, 1907, p. 484). This is clear in the case of the Dinka of the southern Sudan. They see the composition of poetry as something rather akin to lying (i.e. making fictions). A man is a ‘liar’ (alueeth), though in a less derogatory sense of the word than usual, if he is distinguished in singing or dancing or any aesthetic field:

Every young man and woman is considered an alueeth by virtue of preoccupation with aesthetic values, and such an evaluation is not really a criticism to the Dinka. It is a critical praise which the Dinka regard as a compliment on the lines of the expression ‘It’s too good to be true’.

Composition of a song is seen in somewhat the same way. To compose a song is called’ to create’ (cak); to tell a lie is to’ create words’ (cak wel). Cak is also applied to creation by God. In all these meanings is a common denominator of making something which did not exist.

Consonant with this theory of poetic composition, the Dinka see their poems as closely connected to, and arising from, the particular circumstances of their origin. Songs are known to be based on events and to have been composed with the purpose of influencing people with regard to these events. Even when the owner himself does not compose his own song, but goes to an expert, it is still shaped to his purpose. He has to supply to the expert the

detailed information about his situation and particularly the aspects he wants stressed. The glorious or glorified aspects of his lineal history, the relatives or friends he wants to praise and the reasons for doing so, the people he wants to criticize and the reasons for criticism are among the many details that are usually included in the background information.

The Dinka therefore see their songs not ‘as abstract arrangements of words with a generalized meaning far removed from the particular circumstances of their origin’ (p. 84)—a not uncommon view in modern English and American critical theory—but rather as something designed to bring about changes and play an effective part in social life.

Songs everywhere constitute a form of communication which has its place in the social system, but among the Dinka their significance is more clearly marked in that they are based on actual, usually well known events and are meant to influence people with regard to those events. This means that the owner whose interests are to be served by the songs, the facts giving rise to that song including the people involved, the objectives it seeks to attain whether overtly or subtly and whether directly or indirectly, all combine to give the song its functional force. This cannot be fully understood through the words alone whether spoken, sung, or, as is now possible, written. The words of the song, their metaphorical ingenuity, and their arrangement contribute to this force, but to appreciate the functional importance of the song, words must be combined with the melody, the rhythm, and the presentation of the song for a specific purpose.

When I used occasionally to read poetry and was asked what I was reading, I used to say I was reading songs; it was always asked then what sort of songs—prayers, war songs, courting songs, or songs for singing when accompanying a bull. Eventually I decided to call poems ‘sitting songs’ which at least suggested some sort of a purpose which they might serve … I had great difficulty, even with people whom I had accustomed to the idea, to convey that words of a song could be separated from its music, for everyone is not thinking of the ‘meaning’ of what he sings, a meaning which could be paraphrased in some way.

(ibid. pp. 84–5)

Unless we appreciate this Dinka interpretation of the nature and purpose of poetry, we cannot understand how their songs can be so effective in bringing about change and affecting actions and relationships.

How far such local theories about poetic genres and purpose are accepted by everyone in a local audience is perhaps impossible to say in any given case. Certainly views about the nature of poetry itself, as well as taste for particular details, are liable to vary between individuals, and to change over time, and between generations differences make themselves felt. But it seems fair to suggest that even if not totally shared by everyone, local theories of the kind described by Deng for the Dinka or Babalọla for Yoruba ijala poems provide a more fruitful starting-point for the analyst interested in the role and effects of such poetry than assuming that it must necessarily be represented according to some model of poetry implicitly assumed by the foreign observer. Often enough the general framework is at leas intelligible to most people present, while leaving room for shades of interpretation within it—as with the Fijian heroic poet Velema where the details may be queried, but not the underlying poetic theory of divine inspiration.

Sceptics … suspect that the poet exaggerates the virtues of the heroes … yet no one doubts the validity of his talent for literary rapport with the supernatural … the poet’s ecstasy thus [for his listeners] determines the events of history … Natives at The-Place-of-Pandanus trust the ancestral communications of seers so perfectly that those who dispute of even recent history refer to them for solution. Through such communion forgotten genealogies of the last generation can be known again with certainty.

In considering local evaluations of the success or failure of poetic compositions it is helpful to know of these underlying poetic theories, which may differ from our own. Thus the idea—held by the Dinka and many others—that music and presentation may be as important as ‘meaning’ implies a particular stress on criteria relating to performance and delivery rather than, as so often with written poetry, primarily on text and content. The local evaluation of a song among the Dinka must also take account of the purposive quality of Dinka songs: ‘A good song should move the audience toward its objectives. A war song must arouse a warlike spirit and a dance song must excite the dancers. If the objective of the song is to win sympathy in a sad situation, both the words and the music should be effectively sad’ (Deng, 1973, p. 93). Deng shows how these criteria influence the Dinka in their sense of what is or is not a good song (Deng, 1973, pp. 91ff) consonant with their view of the nature of poetry.

By contrast Yoruba hunters judge ijala songs more by what they conceive to be the ‘accuracy’ of the singer’s words and the wisdom expressed in the song—since his words are assumed to have been directly taught him by the god Ogun—allied to the musical and performing ability with which he conveys the god’s utterances effectively to his audience (Babalọla, 1966, pp. 50ff).

Judging the effect of a particular piece of oral poetry on an audience can thus never be a simple matter, even for someone with deep knowledge of local conventions. To understand the effect fully one would need to know the ‘meaning’ locally attached to the particular characteristics of the poem as well as to poetry generally, the mood of the audience, the social and historical background, the appreciation of certain modes of delivery, and so on. All too often these are aspects about which observers tell us little, while they hasten on to generalise about the over-all ‘functions’ of poetic forms in a particular society. Because it is difficult to assess exactly how a poem is being received, this omission is not altogether surprising. But it is worth saying again that for a full appreciation of the effect and context of poetry in any culture, some attention must be given not just to obvious topics like occasion, audience or performers, but also to local ideas about the genesis, purpose and meaning of poetry.

7.4 Some effects of oral poetry

This discussion of audiences and the effects which performances tend to have on them has concentrated on obvious points and situations. But these straightforward purposes and effects are the ones to consider first—and they often get forgotten in sociological theorising. It is only after considering these aspects that it is sensible to move on to more generalised or abstract speculation.

The main point to emerge is the variety of effects oral poetry can have—an obvious point, once stated, but easy to overlook, given the attraction of monolithic theories of the social functions of literature. The effect a piece of poetry is likely to have depends not on some absolute or permanent characteristic in the text itself, but on the circumstances in which it is delivered, the position of the poet, and perhaps above all on the nature and wishes of the audience. To class We shall overcome as a ‘protest song’ and assume that its ‘function’ is to effect a political purpose, ignores the fact that for some audiences and in some cases it may be primarily listened to for entertainment, or sung (by a participatory audience) just to while away the time or as a kind of ‘work song’ to accompany a march.

The same poem delivered in different circumstances or to different audiences may well have a correspondingly different effect. We know, for instance, that the Ainu epic Kutune Shirka was recited sometimes at religious ceremonies and sometimes when time simply lay heavy on peoples’ hands, like waiting for fish to bite or by the fire at home on a winter night (Waley, 1951, p. 235). The very same Hawaiian songs which were first used during the hardships and oppression of war-time as outlets for frustration and a channel for informal social protest, were after the war used for purely recreational purposes (Freeman, 1957), while in contemporary Britain the same song by immigrant Punjabis can be used both to ‘set toes tapping from Southall to Smethwick’ with its racy beat on festive occasions, and to express the bitterness of the solitary Asian wife left isolated in a strange land by her ‘overtime’ husband who works day and night

I don’t want your fridge, your colour TV.

I’d rather have you at home with me.

The nights are cold in this heartless land;

My husband, God help me, is an overtime man.

(Mascarenhas, 1973)

This multi-purpose potential in poetry is more pervasive than usually supposed. Indeed, the same poem on the same occasion can play different roles for different parts of the audience. It is common for poetry to be used as a veil for hidden political purposes: thus Mau Mau songs in Kenya set to well-known hymn tunes played an important part in the political movement, where to the European establishment they seemed merely to express religious sentiments; while many Irish ‘love songs’ about Dark Rosaleen or Kathleen Na Houlihan convey a political rather than a sentimental message to some listeners. And for the Somali independence movement, Andrzejewski describes how the compressed imagery of the balwo love lyric was turned to use in the struggle for independence in the later 1950s.

The cryptic diction of the balwo was well suited for the purpose: satire and invective could easily be hidden in an apparent love poem. In public, or even on the government-controlled radio, a poet could say with impunity:

Halyey nim uu haysw oo

Hubkiisu hangool yahaan ahay.

I am a man who is assailed by a huge wolf

And who has only a forked stick.

If challenged by a suspicious censor he could say that the wolf represented his despair in love, while the sophisticated members of his audience would interpret the image as describing the defencelessness of the Somali nation in face of the military might of foreign powers.

(Andrzejewski, 1967, p. 13)

This contextual and relativist approach to the analysis of the effects of oral poetry does not mean that one must never generalise about the functions likely to be fulfilled, only that in indicating general patterns one cannot count on establishing absolute truths or avoid the need, with particular poems or genres, to enquire in detail about context, performer and audience. Indeed there are some very common patterns, many of which cut across the classification in terms of audience given in an earlier section.

Oral poetry, for instance, frequently serves to uphold the status quo—even to act as the kind of ‘mythical’ or ‘sociological charter’ which Malinowski emphasised as one function of oral prose narrative (Malinowski, 1926, pp. 78–9, 121). Court bards strengthen the position of rulers, poets act as propagandists for authority, the accepted view of life is propagated in poetic composition and, when poets are an established group, their own power and interests are often fortified by their performances. The social order is also maintained through the performance of poetry in ceremonial settings, where established groups express solidarity and social obligation in song. But the same processes can equally have effects disruptive of the settled social order; for songs can equally well be used to pressurise authority or express and consolidate the views of minority and dissident groups. The likely effectiveness of such poetry is demonstrated by the frequency with which it has been discouraged or banned by government—from the Irish authorities’ harassment of nationalist singers during the nineteenth century (Zimmerman, 1967, p. 51) to the Nigerian military rulers’ banning of political songs in 1966.

One of the most widely occurring occasions for poetry and song is in relaxation after work. Working parties in fields or forests or factories commonly end their sessions with a period of singing: this is documented from all over the world, from Sotho or Limba cultivators to Tatar hunters or the relaxed singing as groups of people travel home after the serious business of watching a football match. Beneath all cultural differences one underlying theme and purpose in these occasions is surely recreational. It constitutes both an ‘act of sociability’ (as Malinowski put it) and a means of recreation after work.

Other commonly found effects of performances of oral poetry include rituals of healing; ventilating disputes (either intensifying or resolving them); exerting social sanctions against offenders or outsiders; communicating in an oblique but comprehensible form truth which could not be expressed in more ordinary ways; providing for the articulation of man’s imaginative creativity; realising a desire to grasp and express the world in beautiful words; adding solemnity and public validation to ceremonial occasions; providing comfort and some means of social action for the bereaved or oppressed…