1. Wrens’ Calling

(London, 1942–1944)

©2024 Justin Smith, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0430.01

The National Services (No. 2) Act of December 1941 was the first to conscript unmarried women between the ages of twenty and forty (later nineteen and forty-three) to undertake work in the war effort: in industry, agriculture or one of the uniformed services. Hannah Roberts writes that:

Early objections to the conscription of women gave way to a national sentiment that was overwhelmingly positive. […] Women who entered the women’s services were far from derided; instead, they were congratulated for doing so. […] Patriotism had a great impact upon all of the women’s services, which began to grow rapidly after 1941. Numbers of Wrens doubled between 1941 and 1942.23

Unlike the other women’s services, the WRNS did not take conscripts; volunteers went through a selection process. There was a widespread assumption (shared by many who applied and indeed their parents) that social class was a determining factor in vetting applicants.

For girls of my generation and background, who were not normally encouraged or expected to go to work in the way everyone does now, and therefore not encouraged to train for anything useful, the war was an opportunity for them to leave home, gain some sort of independence and do something interesting which was actually approved of by their “elders and betters”. Mothers of those days who would not have allowed their daughters to work in “unsuitable” occupations and had them chaperoned and constrained with, to us now absurd restrictions, thankfully allowed themselves to trust in the universally held belief that all would be safe in the gentlemanly embrace of the Royal Navy. And in this they were proved to be right, as a matter of fact.24

Another Wren, Audrey Johnson, recalls: ‘my mother had not wanted me to join the Land Army, because it would ruin my hands, neither had she wanted me to go into a munitions factory because she did not think I would like the type of woman there’. Such prejudices were widespread. Johnson confided to a friend, ‘If I joined anything it would be the WRNS. It’s the most difficult service to get into’. Furthermore, by aiming high, ‘if we were turned down for the Senior Service we could still apply for the WAAF, and if that failed there was always the ATS’. Despite her expectations of failure, Audrey, ‘the stepdaughter of a foreman engineer from Leicester’, was enrolled as a Wireless Telegraphist. Nonetheless, in her new environment she:

felt unsure, lonely and out of place and could not work out how I had been accepted for this service, that appeared to choose its entrants with such care. I had nothing they asked for, certainly no educational qualifications. I had a feeling I must be the only girl who had left school at fourteen. But I was not going to mention that to anyone, and night school elocution lessons had helped a bit.25

The example of Audrey Johnson shows that neither background nor qualifications were a barrier to her joining the Wrens, although aspirational ‘self-improvement’ may have played a part.

In order to ensure that the ATS (and in time the WAAF) got the necessary recruits, it was made clear that women would be allocated according to ‘the needs of the services’. To help facilitate this process, special entry requirements were laid down for the WRNS (which had a long waiting list for voluntary applicants). These were designed to ensure that a large proportion of optants would be ineligible for the Wrens and included proficiency in German, practical experience of working with boats, or a family connection with the Royal or Merchant Navy.26

Although the WRNS remained the smallest of the three uniformed women’s services, as Audrey Johnson and countless other examples show, in practice these criteria, if relevant at all, were only loosely applied. Nonetheless, the Ministry of Information (MOI) recruitment film WRNS (dir. Ivan Moffat, November 1941) presents initiation into the service from the perspective of the officer-class, fresh from Greenwich training college, but endowed with plenty of paternal Naval pedigree.27

Video 1.1. Film clip (0.51) from WRNS (dir. Ivan Moffat, Ministry of Information, November 1941). Film: IWM (UKY 344), courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/fc9155f9

Far from putting off applicants from humbler backgrounds, who like Audrey Johnson didn’t obviously belong to the Naval ‘club’ through family connections, recruitment films encouraged aspirational applicants. In some senses joining the services may have offered many young women, Joan Prior included, a fast-track to social mobility. Brenda Birney, ‘not having any affiliation with any particular Service’, decided like Audrey Johnson ‘to apply first to the WRNS and if they refused me I’d try the WAAF, leaving the ATS till the last. […] I was called for an interview for the WRNS when I was asked if I had any particular reason for wanting to join them. It didn’t occur to me that the correct answer to this was that my father, uncle or whoever, was an admiral, although this did cross my mind much later’.28 Birney’s recent office work experience meant she was chosen to be a Writer. Like many others of her background, on arriving at the training depot at Westfield College, Hampstead,29 she decided ‘It was the nearest I was ever to get to going to university. […] I was the best in the writers’ class. […] They looked on this as a crash course from which we would emerge after three weeks as fully fledged secretaries’.30

Of one of her interviewees, Barbara Wilson, Penny Summerfield reports: ‘as a middle-class young woman, she decided that she would have to join the WRNS, the most socially select of the available options’.31 Whilst Roberts’ evidence substantiates this perception ‘that the WRNS was the most admired’ of the women’s uniformed services, and ‘far more selective than the ATS’, she insists ‘this was based on the skills and abilities of the applicants, rather than their family backgrounds or social contacts’.32

Alongside a rapid increase in its recruitment, the period of 1941–1942 also saw an expansion of the roles women could perform in the Wrens. At the outbreak of war, ‘the WRNS was organised into two categories: one was “specialised branch”, which would cover office duties, motor transport and cooks; the other was “general duties branch”, for stewards, storekeepers and messengers’.33 By 1942, the quest to relieve as many men as possible from shore-based roles to serve at sea led Wrens to be trained in a range of highly-skilled tasks—some of which, such as Anti-Aircraft Target Operators were semi-combatant. Wrens became Air Mechanics, Torpedomen, Ordnance (Armourers), Radio Mechanics, Degaussing Recorders, Dispatch Riders, and ‘the most popular and symbolic of the WRNS categories’: Boats Crew.34 Wrens were also employed as Coders, Telegraphists, Cyphers, Signallers and Plotters.

Although Wrens could in theory choose a role, they were in practice directed according to the selection evaluation and the needs of the service. Priscilla Hext (Holman) ‘applied to join Boats Crew, but alas that category was full up. They offered several jobs, but none appealed so they gave me an aptitude test. […] Next day I was sent to see a Lieutenant Commander Royal Navy who told me that the test showed I had an engineering aptitude, so would I like to join the Fleet Air Arm as an Armourer?’.35 Roberts’ interviewee, Sheila Rodman, had worked as a ‘laboratory assistant and typist for James Neelam and Co. steelworks’ in her native Sheffield. Like Hext, she ‘was selected to train as a Wren Ordinance (Armourer)’ in the Fleet Air Arm.36 Hazel Russell (Hough) was:

a fully trained secretary, employed by an insurance company. In my spare time I drove a YMCA van to anti-aircraft gun and balloon defence sites in the north London area. Since I wanted to join the Services I decided to volunteer to join the WRNS and hoped that I could become a driver. […] I was then given a driving test and to my surprise was told that I had failed and they tried to persuade me to become a typist […] Fortunately they were considering the possibility of recruiting six Wrens’ […] [at] HMS Dolphin, the submarine base in Portsmouth harbour […] to replace the sailors who manned […] a simulator known as the Attack Teacher.37

She was accepted, promoted to Leading Wren and ran an Officer training programme in submarine attack, conducting maintenance of the simulator between courses.

Understandably much attention has been paid by writers like Summerfield and Roberts to the examples of women working in masculine roles during World War II, the contingent nature of this permission to transgress gendered occupations, their experiences of those freedoms, their limitations and risks, and the reactions from co-workers and family members. Indeed, interest in this phenomenon was manifest and widely publicised at the time, in the press, in MOI propaganda, in books and in films such as Millions Like Us and The Gentle Sex (both 1943). Peggy Scott’s 1944 celebration of female contributions to the war effort, They Made Invasion Possible trumpets: ‘they have taken over the men’s jobs in the Services, in the factories and the shipyards, on the railways and the buses, on the roads and on the land’.38 And her Wren examples feature Boats Crew, ‘the first woman Fleet Mail Officer’, Plotters, Wren Torpedo-Men (sic) and Signallers. Less attention is paid, then and now, to trained clerks and secretaries who served as Writers and Telegraphers in the WRNS. But for all those, like Brenda Birney and Joan Prior, whose work experience led them to become Writers, there are others whose potential to exceed their peacetime lot was identified in selection.

Roberts writes of Daphne Coyne, who ‘was discouraged from going to the WAAF recruiting office by her mother because the WRNS was seen as “THE service”’.39 Yet she:

came from a single parent family and had been working in a nursing home as a cook before joining the Wrens in 1940. Her expectation when going for interview was that she would become a cook or steward, as these were the only categories open at the time and mirrored her work experience. However, after beginning work as a messenger in a cypher/signals office she became one of the first Wrens trained to interpret radar signals. Clearly, the WRNS was more concerned about the ability of the people it employed than their social background.40

As Summerfield’s extensive oral history work demonstrates, family background and parental opinion were significant factors in shaping young women’s service aspirations. Yet her findings show ‘there were no simple determinants’—such as social class or the daughter’s/parents’ ages—on these decisions. Summerfield’s nuanced interpretation of her interviewees’ testimonies reveals ‘the process by which women’s family narratives positioned the self in relation to discursive constructions of wartime possibilities for young women. It reveals what different positions meant for the identity “daughter”.41 For Crang what underpinned these negotiations was a seismic disruption whereby pre-war concepts of the “dutiful daughter” clashed with wartime notions of the independent young woman serving the state’.42

Fig. 1.2. WRNS Recruitment Leaflet, private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London..

In order to understand how this sociological tension played out in the case of my mother, it is necessary to know something of her own family background. Joan Prior was born in Barking, Essex, on 24 May (then Empire Day) 1923. The youngest of the three surviving daughters of a retired brewer, Henry (Harry) Prior, and his wife Grace, Joan had the advantage of a private education over her elder sisters, Grace (called Geg) (1908–1992) and Bessie (1909–1984). Fourteen years separated Joan from her next sister Bessie; there were but seventeen months between Bess and Grace. Her elder sisters not only grew up side by side, and went to the same schools, but were married on the same day, 22 July 1933, the year of Hitler’s rise to power in Germany. As it happened, the occasion was more precipitous for the Prior family. A double wedding had been planned between the sisters, but their mother Grace, superstitious to a fault, rejected the idea as unlucky. So, they were married on the same day, at the same church, St Margaret’s Barking, two hours apart. Grace first, to Charles Snell; then Bessie, to Stanley Bones. The day went off without a hitch, much to everyone’s relief. Then, a month later, on 24 August, tragedy struck the Bones family. The husband of Stan’s elder sister Annie, John Spink, was killed in an accident at work. He was employed by Nicholson’s Gin-makers at their Three Mills distillery, Bromley-by-Bow. According to local newspaper reports, during a spell of hot weather he had been swimming in one of the large water tanks at the site and drowned. The inquest jury returned a verdict of death by misadventure. Grace Prior’s verdict was characteristic: ‘thank God we didn’t have that double wedding, or they’d have blamed us!’

This anecdote is instructive of the family’s mental landscape, dominated as it was by the paranoid fears of their mother. But it wasn’t that she didn’t have cause for anxiety. Grace and Harry Prior had lost their first-born daughter, Winnie (b. 1905), to rheumatic fever at the age of eleven in 1917. Beyond their grief at burying a child blooming with life in Rippleside cemetery, life (and death) went on: the end of the Great War brought the Spanish flu. With two other daughters under ten, a household to run and a husband working (and drinking) all hours at Glenny’s Brewery, Grace Prior soldiered on as best she could. But in 1921 the trauma surfaced and she broke down. The doctor advised Harry Prior they should try for another child: a replacement. Joan was born a fortnight before her mother’s fortieth birthday and was immediately doted upon. Within a couple of years her elder sisters, both good at arithmetic, left school and found employment: Geg became a cashier at Bright’s butchers in Barking, Bess a ledger keeper at Eastick’s in the City. By the time Joan was ten, her sisters were married. Their mother could lavish all her attention on Joan. And she did.

If this sketch provides an idea of the family’s emotional temperature, the second factor that is important is their social position. As the depression hit Britain in 1930, the Priors’ lives changed. Harry Prior, following in his father’s footsteps, had risen from drayman’s boy (at fourteen) to head brewer at Glenny’s on a decent wage. But at the end of 1929 the company announced a takeover by Taylor, Walker & Co. Ltd, with the sale of fifteen pubs in Barking, Dagenham and Romford and the closure of the Linton Road brewery. There were thirty employees, nearly all of the older ones like Harry Prior (approaching fifty) being shareholders, and they were assured of ‘just and generous compensation’.43 The Priors invested this money into a succession of moderately unsuccessful small businesses, including corner shops and tobacconists in Barking, Walthamstow, Chadwell Heath and Hornchurch. They also funded their sons-in-law, Charlie Snell (an electrician) and Stan Bones (a haulage driver), to buy a garage—an enterprise which fell through. Despite their lack of entrepreneurial acumen, the family could afford annual holidays (to the West Country and the Isle of Wight) and, from the age of eight, to educate Joan privately, at Napier College, Woodford. These aspirations were entirely in keeping with their resolutely Conservative politics. During the school summer holidays in the early thirties, Joan would be sent away on the Great Western Railway from Paddington to Cardiff, where she stayed with Aunt Lucy (Grace Prior’s sister-in-law) and her daughter Peggy, ten years Joan’s senior. It was always said this was to give Aunt Grace ‘a break’.44

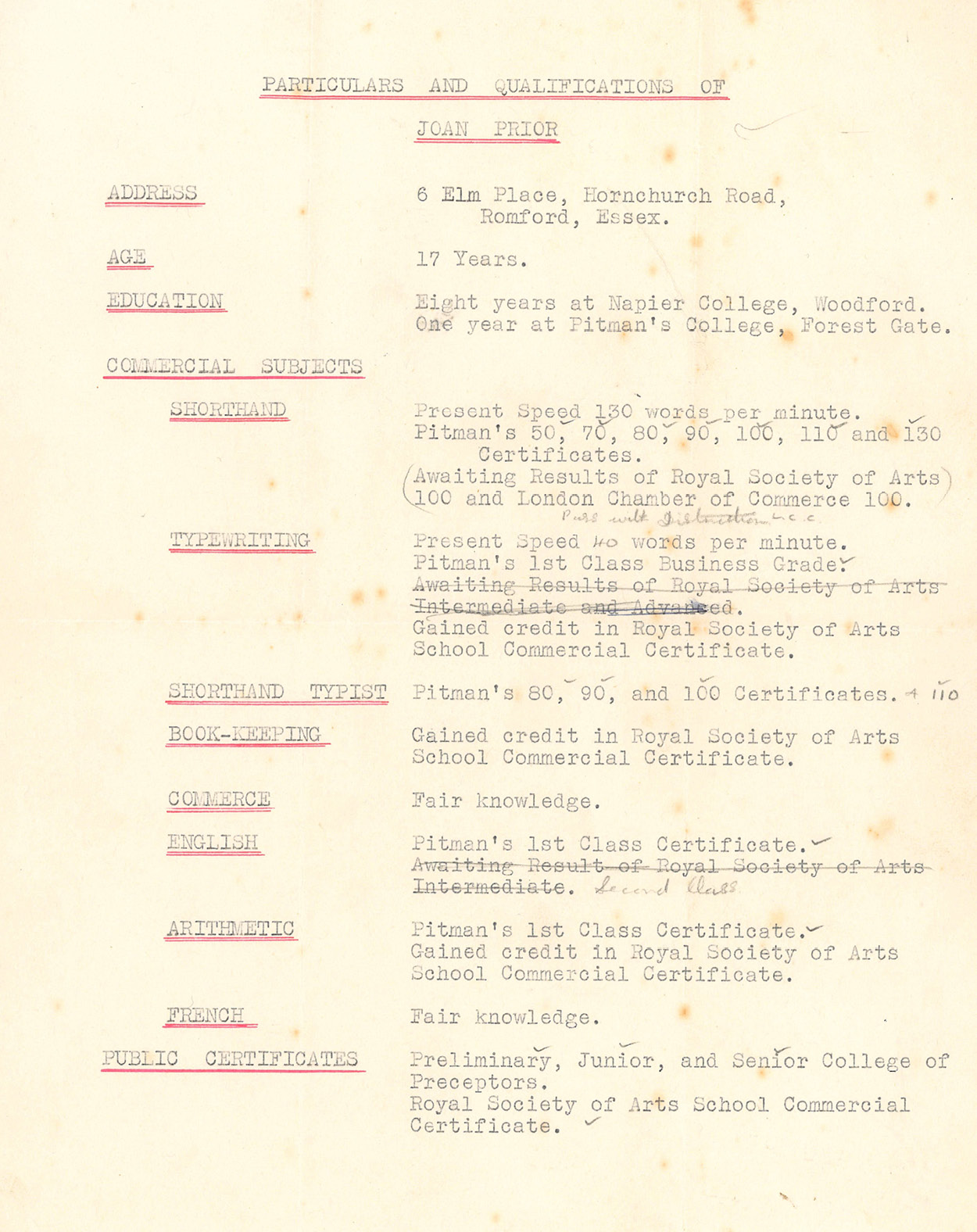

Fig. 1.3. The Curriculum Vitae of Joan H. Prior, 1940. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

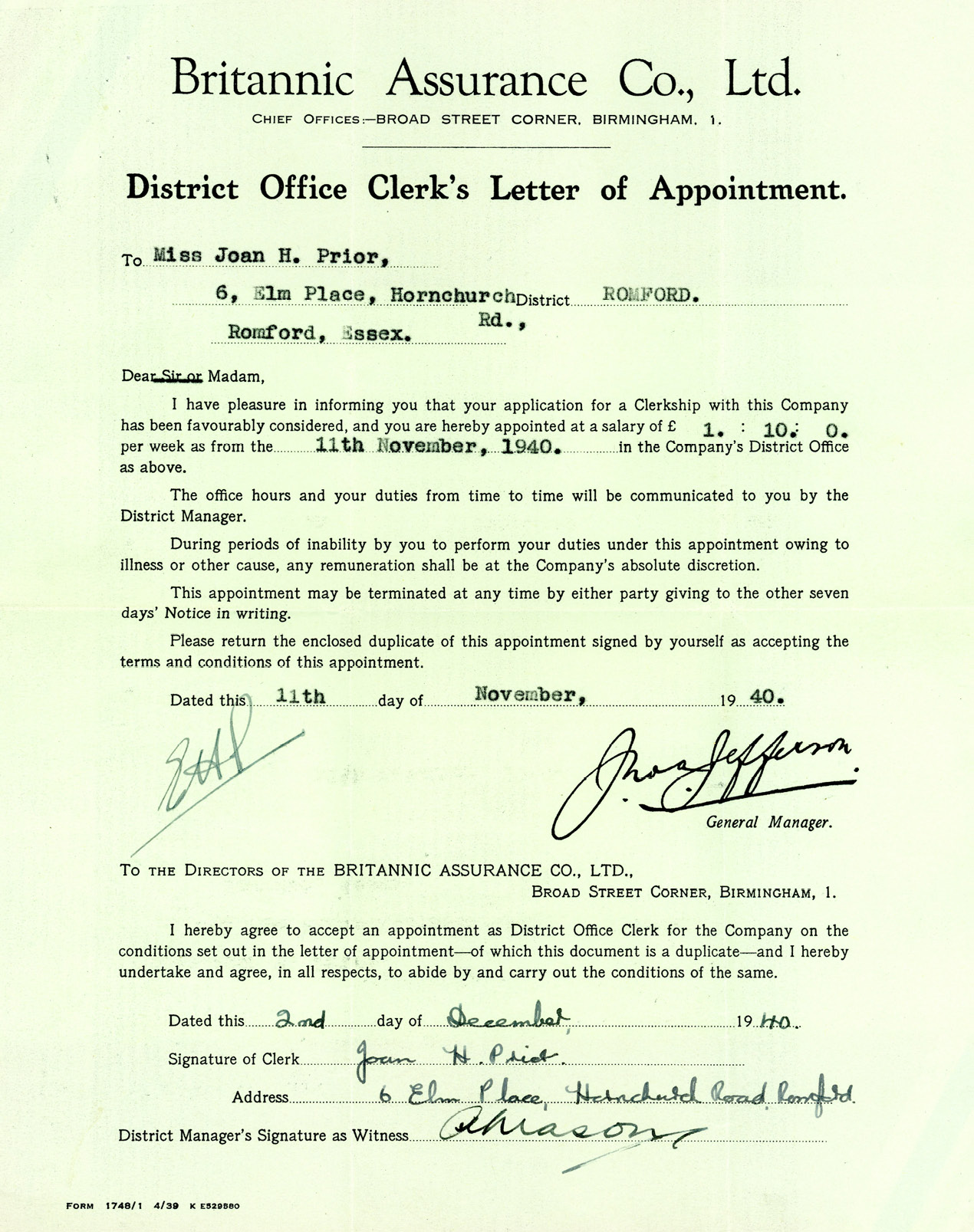

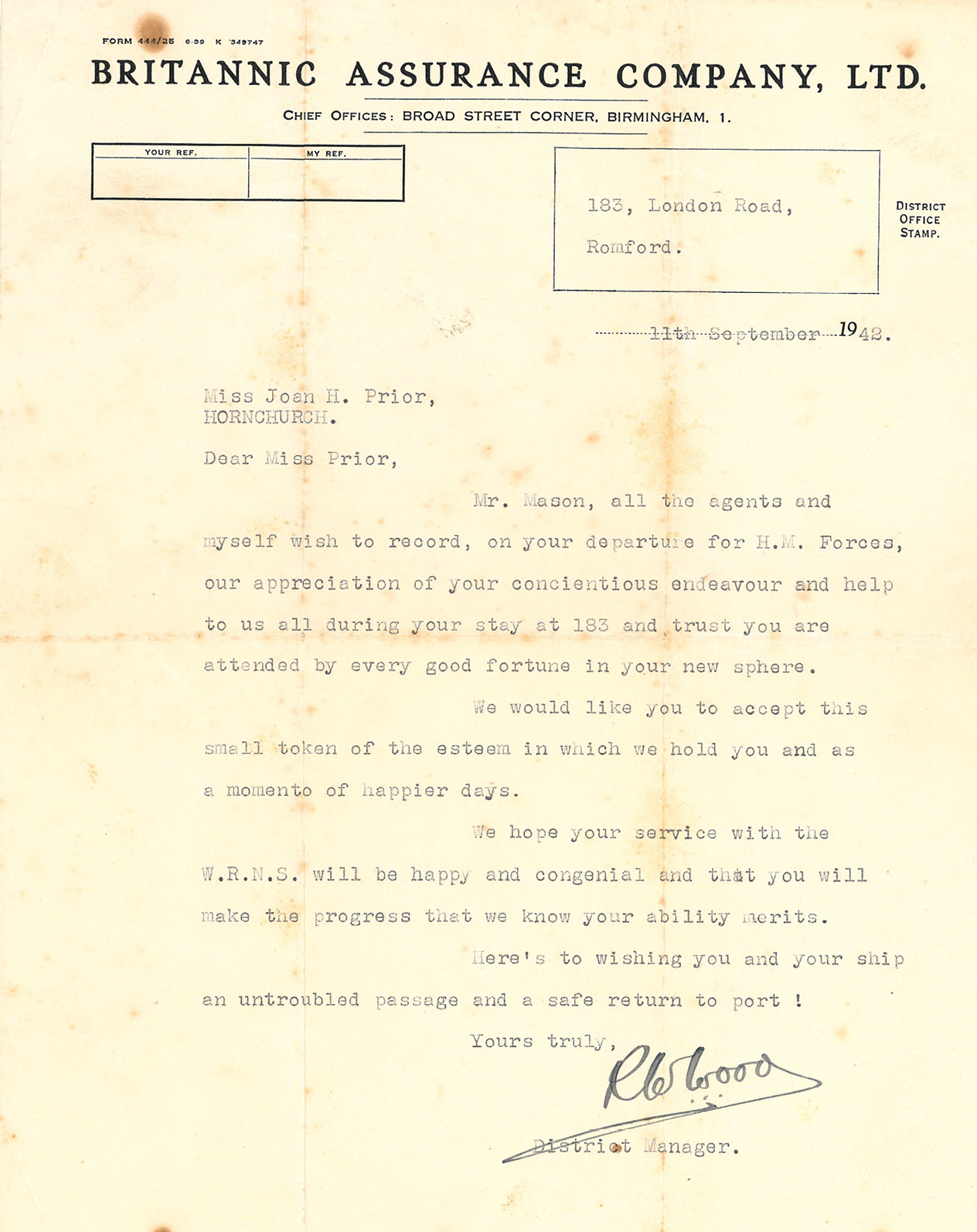

When she left Napier in 1939, Joan completed a year-long shorthand-typing course at Pitman’s Secretarial College at Forest Gate from which she obtained excellent certificates of proficiency. By then war had come. Joan initially found employment with an insurance company at Regis House, King William Street, on the north side of London Bridge. But in the full force of the Blitz in the late Summer of 1940 the daily commute had become increasingly perilous. Despite the large air-raid shelters under Regis House in the disused King William Street tube station, Grace Prior’s fears for her daughter’s safety became unendurable. Her mother engineered a position for Joan with the local branch of the Britannic Assurance at their office in Romford, closer to home. For a while, things settled down. But by late 1941 her mother’s protectionist instincts were increasingly at odds with Joan’s spirit of independence which was fuelled by the new Act of Conscription. If Joan must serve, she should apply to the senior service.

Fig. 1.4. Britannic Assurance Co. Ltd, Joan H. Prior, letter of appointment, 11 November 1940. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

Grace Prior’s calculations were stratified according to her own finely calibrated prejudices. Her Victorian snobbery had been cultivated over a lifetime of graft and circumspection. And her bigotry, like all bigotry, was rooted in insecurity: fear of others. The daughter of a bootmaker who gambled his family to ruin, as a girl she sold newspapers for her mother outside Upton Park station. She clung to an unfounded belief that their family was descended from nobility and had claim to a pedigree from which, by some mysterious quirk of fate, they had been cruelly disinherited.

It was a grand myth, but it fed a genuine sense of superiority. So, when it came to her youngest daughter’s duty to her country, working in a factory or on the land was out of the question—the ATS were no better than they should be, and WAAFs romantically susceptible. By swift process of elimination, only the senior service, the Royal Navy, might offer the chance to rub shoulders with a better class of person.

Grace Prior, in arriving at this answer, had much in common with Jean Gordon’s wartime mothers sketched above. Yet shared assumptions afforded little comfort to Grace. This still meant Joan leaving home. Who would look after her then? Joan’s desertion would surely worry her mother to an early grave (she died aged eighty-five in 1968). It would tear her nerves to shreds. As certain as night followed day she would suffer another breakdown, like the breakdown she had after Winnie’s death.

Fig. 1.5. Letter from R. W. Wood, District Manager (Romford), Britannic Assurance Co. Ltd, to Miss. Joan H. Prior, 11 September 1942. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

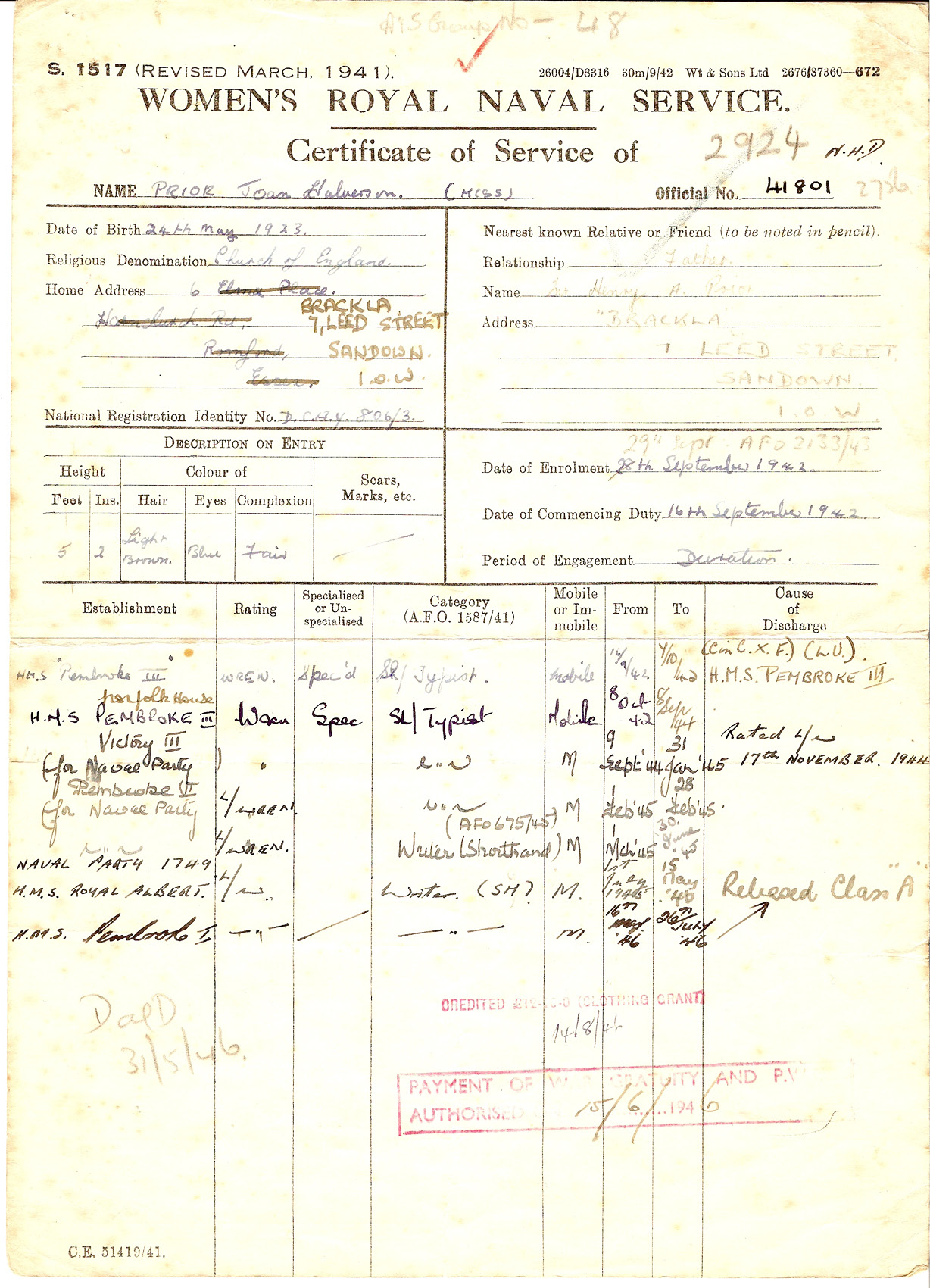

First, they would sell up the shop in Hornchurch and move in with Bess and Stan in Hulse Avenue, Barking. Then they should go to the country, Grace and Harry. That was it. If Joan was going away, so would they. They would go down to Somerset to her sisters-in-law Lucy and Ida. To the country. They would be safer there. Far away from the bombs and the sirens and the ack ack that tore through her soul night after night, as if it were directed at her in person. And Joan would come home on leave, whenever she could, of course. And of course, she promised, she would write. Yes, she would write. So it was that in September 1942, at the age of nineteen, Joan Prior joined the Women’s Royal Naval Service as a Writer.

Fig. 1.6. WRNS Service Record, Joan H. Prior, 41801. Private papers of

Joan Halverson Smith.

1.1 Mill Hill

Dame Vera Laughton Matthews, Director of the WRNS during World War II, wrote:

The opening of the great depot at Mill Hill by Mr. A.V. Alexander, First Lord of the Admiralty, in May 1942, was a landmark in WRNS history. [...] Many distinguished naval personalities were present […] in the audience but my chief memory is of the rows and rows of Wrens who packed the great hall and the high galleries. In speaking to them I said that in the Navy one talked about ‘a happy ship’ and that atmosphere was made not only by those at the top but by every individual; each Wren who passed through the depot would leave something of herself behind in the atmosphere which would affect those who came after.45

Fig. 1.7. The former WRNS Training Depot at Mill Hill shortly after its opening as the Headquarters of the Medical Research Council in 1950. Image courtesy of Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo. https://www.alamy.com/medicines-back-room-boys-in-their-new-headquarters-at-mill-hill-london-on-march-21-1950-having-waited-ten-years-for-it-to-be-opened-due-to-the-war-the-building-was-used-by-the-admiralty-during-the-war-as-a-training-centre-for-wrns-the-exterior-of-the-new-building-which-will-house-the-research-workers-in-their-experiments-and-tests-ap-photo-image519356228.html

Mill Hill, on The Ridgeway in North London, had been built as (and later became) the National Institute of Medical Research. Following its requisition in March 1942 by the Royal Navy, it was christened HMS Pembroke III and established as the central training depot, with a capacity of 900.46 All new recruits entered the service as Probationers for basic training and their category of work was established at the end of the induction. As Roberts records:

The WRNS was the only women’s auxiliary that did not provide uniforms straight away. The issuing of a uniform at the end of two weeks’ initial training was seen both as a reward and achievement for many women. This protocol reinforced the perception that only the hardest working and most suitable would make it into the service.47

Indeed, Virginia Nicholson is one of many writers who report the widely shared view that preference for the WRNS over the other women’s services was down to the appeal of its uniform.48

Wren Angela Mack remembered that this spirit of rigour and exclusiveness was conveyed in an introductory lecture given by a ‘fierce’ naval officer:

He made it very clear that it was our duty to defend our country to the nth degree, if necessary to our last breath. We were exhorted to give one hundred and twenty per cent of our best every moment of every day to live up to the great tradition of the Royal Navy. Much was made of the fact that we would be part of the Navy and not an auxiliary service as were the ATS and WAAF.49

Roberts suggests that ‘much was done in the first two weeks to put off those new recruits not cut out for a life in the WRNS’. She cites Wren M. Pratt whose ‘most vivid recollection of this period is of scrubbing endless flights of stone stairs with cold water and carbolic, while others were assigned to kitchen chores. It was hardly surprising that many girls threw in the towel during that fortnight!’50

Another new recruit, Margaret Boothroyd, wrote of their Mill Hill days:

This was our first glimpse of Wren life. Here we were Pro-Wrens, and we were given a bluette overall, a garment we wore for the first few days. We were then given a medical check, including a hair search for head-lice—we were very annoyed about that—then a meal. I still remember very clearly being given sausage and very thick ships’ cocoa, which I didn’t think went together very well. I met Laura (Mountney, later Ashley) that first day and we were together for the rest of our service in the WRNS.

We were shown to our sleeping quarters (cabins instead of bedrooms, bunks instead of beds, galley, not kitchen etc) and shown how to make our bed, envelope-style sheets and blanket, and the blue-white bedspread, which had a ship’s anchor on it, this must be the right way up or the ship would sink!!

During those first few days we were interviewed to find out in which Section we were to work. We were all put into Divisions and really it was very much like being back at school. We had various lessons in classrooms learning the Navy jargon, badges and ranks. As for working and scrubbing, personally I did none and I don’t think Laura ever did any either. My job was polishing a very long corridor, which was already very highly polished! Others cleaned cutlery etc.

Fig. 1.8. Notes on naval abbreviations taken by Joan Prior on 21 September 1942 during her first week of basic training at Mill Hill (HMS Pembroke III). Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

During our time at Mill Hill we were issued with a jacket, skirt, navy raincoat and greatcoat, hat, two pairs of shoes, gloves, three white shirts and a black tie. Wrens (I think it was the only service to do this) were given a sum of money per day in our pay to buy our own undies, pyjamas etc, which was very much appreciated; we got a clothing coupon allowance to buy these.51

Phyllis ‘Ginge’ Thomas arrived from Swansea where she had worked as a typist in the Town Clerk’s Office:

I had only been to London once in my life, and I felt absolutely terrified when I arrived at Paddington Station. I was on my own, and there was so much hustle and bustle! There were notices up that advised the Wrens on where to gather, and I was soon helped into an army lorry and taken to Mill Hill for my two weeks’ basic training. There was no guarantee that you would become a Wren at the end of the training—they could reject you if they didn’t think a service life would suit you.

The fortnight at Mill Hill was something I’ll never forget. There were about 850 of us, all doing different things. In the mornings we did the most laborious tasks. I think I cleaned more bathroom taps in those two weeks than I have in my life since! At the end you had to do a test in whatever field you wanted to enter—shorthand typing, in my case.

I passed the test and was posted to Norfolk House, St James’s Square, to a job which turned out to be one of the joys of my life.52

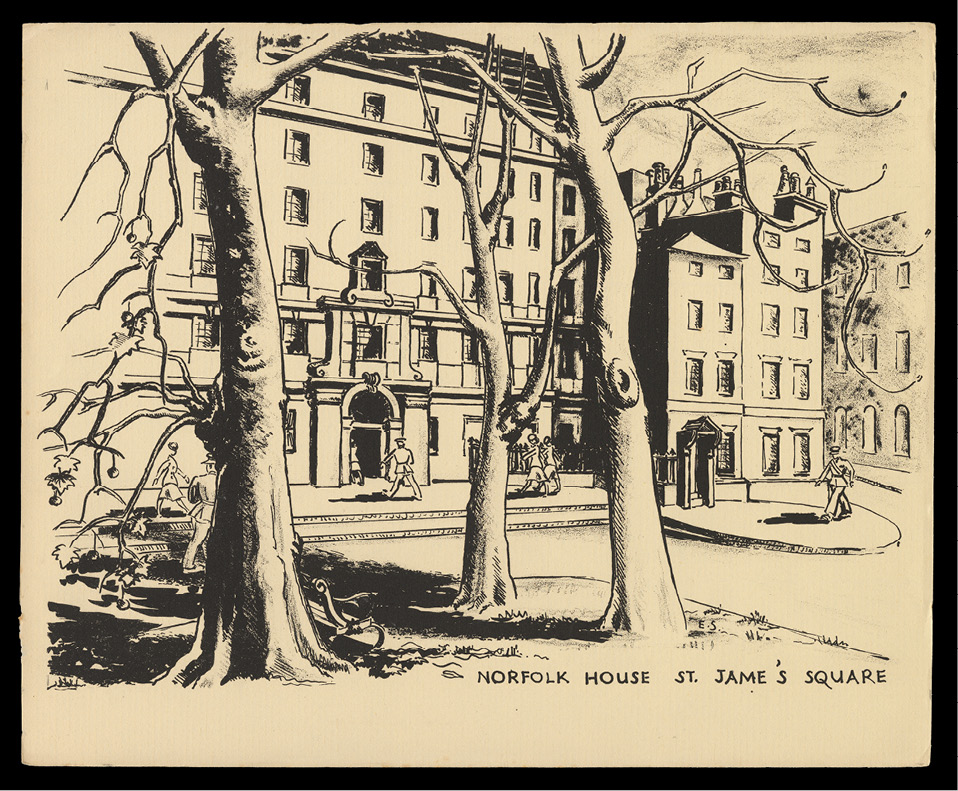

1.2 Norfolk House

On 8 October 1942, Wren Joan Prior 41801 was also sent to Norfolk House—once the seat of the Lloyds Bank board, soon to become the headquarters of Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC). Here, at Norfolk House, the real work began. Wrens Prior and Thomas joined the typing pool run by Leading Wrens Patti Harmer and Di Parnham, based in room 410. However, for some weeks after the Wrens’ establishment at St James’s, daily square-bashing remained a ritual drudgery until Rear-Admiral Creasy (who succeeded Commodore John Hughes-Hallett as head of the Naval Staff of COSSAC) decided this was wasting valuable time and wrote to the Admiralty to tell them so.

In March 1943, Lieutenant General Frederick E. Morgan was appointed as Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander. Morgan’s job, to derive from a number of extant staff studies a coherent plan for a cross-channel invasion, received the gloomy benediction of Field Marshall Sir Alan Brooke: ‘of course it won’t work, but it’s your job to make sure it bloody well does work’. Embarking upon this monumental strategic mission, Morgan commented with wry Churchillian humour: ‘never were so few asked to do so much in so short a time’.53

‘Ginge’ Thomas was soon seconded from the Naval section to work for General Morgan:

Norfolk House was alive with people from all three services and from different nationalities. I was originally assigned to the naval section, but after a few days I was sent “on loan” to a different section. I went to meet a man called General Morgan, the Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander, or COSSAC. The Supreme Allied Commander hadn’t yet been appointed, and I soon realised that it was General Morgan who was responsible for planning the assault on the Continent.

The first time I met him was in a huge room with maps covering the walls. He was sitting behind a desk, and said, “Sit down sailor.” He then dictated some letters to me. That was the beginning of what turned out to be not only a wonderful job, but a wonderful friendship as well.

My first impressions of the general was that he was quite tall, with fair hair and almost boyish looks, with a lovely soft voice—very easy to take dictation from. He was very friendly.

I went everywhere with General Morgan, notebook in hand. I took dictation, typed letters, and took notes at staff meetings.

At the time, General Morgan was working on the plans for the D-Day invasion, so my work was extremely interesting—although at the start, I must admit, it was a little bit beyond me. We all realised that it was very hush hush, and very important, but at the beginning I didn’t quite understand what was happening. It was also a little bit frightening, because I never thought I would be involved in anything so important. Whether the invasion plans would be successful was a big worry in my little mind.

General Morgan was a workaholic. I don’t think there were ever times when I was there and he wasn’t. He was very energetic and hard-working, which I suppose he needed to be to head an operation of that size. I think he even had a bed at the office. He always apologised to me if we had to work long hours.54

GORDON: Before the COSSAC plans were approved in July 1943 a skeleton staff in Norfolk House was already beginning to research and plan for the invasion of France. As it was clear that the bulk of the assault forces and the build-up would inevitably come from Portsmouth, the C-in-C Portsmouth became the Allied Commander designate for the invasion. The staff was called the “X” staff and Commodore J. Hughes-Hallett was chosen to lead it as Chief of Staff (X) to C-in-C Portsmouth.

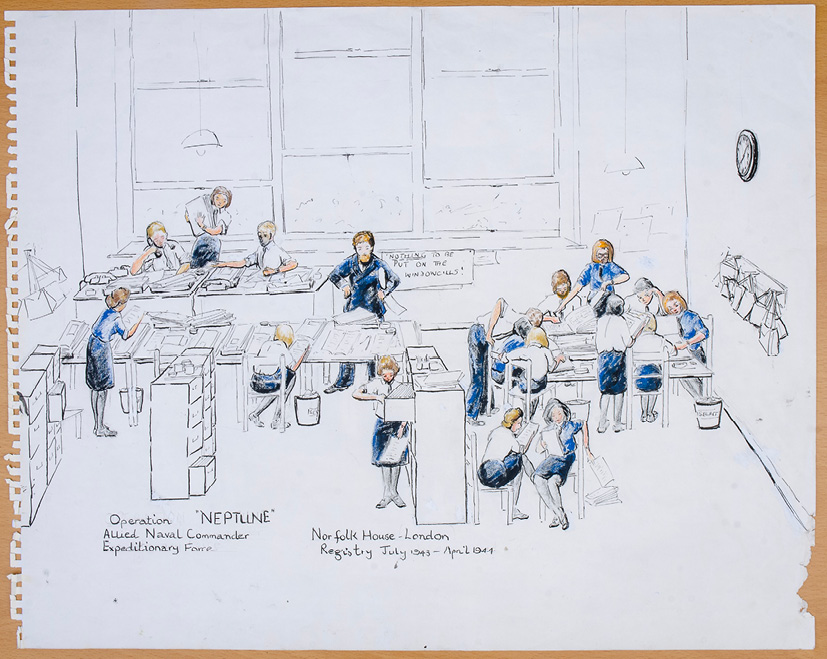

I joined this Staff at about this time and became part of the Registry where the Writers (clerks) worked in a room on the ground floor. To begin with, most of this secretarial staff were those who had been working on Operations TORCH and HUSKY, the North Africa and Sicily landings. There was a Chief Petty Officer (an energetic and articulate Irishman) in charge, about ten or fifteen Wrens, a desk or two, a telephone and a number of steel cabinets and the inevitable In and Out trays and wastepaper baskets. As this relatively small staff was engaged in “winding up” TORCH and HUSKY as well as beginning to deal with papers and documents for the (X) Staff, everyone found themselves doing whatever work was required, with newcomers like myself being taught their duties at the same time.

Though there was an air of restrained excitement and one became aware that there was something very important afoot, everyone remained calm and courteous towards each other and were always ready to explain in great detail what was going on and to what each paper referred. So that by being so early “on the ground floor” I was able to listen and learn and to grasp from the beginning the essential details of the workings of a Naval Registry dealing with Secret or restricted papers and documents, and was duly promoted (Writer). Plans have to be written down and orders and instructions have eventually to be put on paper, and Senior Planning Officers need an efficient Secretarial department to do this for them. Someone had to be trusted, but then in fact eventually the whole of the Forces of the UK were involved in some way or another in the putting together of this Plan and the training, transportation and supplying of the ships and craft and personnel who were to take part, so just about everyone had a secret to keep—and it was a big one.

Basically, every paper and document referring in any way to Wartime plans and operations are designated Secret, or Most Secret, the latter being changed to Top Secret when the Americans became so heavily involved. Therefore, the security of these papers must be very carefully organised, and a process is evolved to make it possible to know the exact location and distribution of every paper at all times, even when circulating within the building to the Staff Officers for their information, comment or action.

To this end, every paper is recorded in a large book or Register with a serial number. From there it circulates to whichever Staff Officer needs to see it. It returns to the Registry before it goes to the next person, each name being entered and crossed off in turn. The Wren Messengers collected the papers from the Officers’ Out trays and put them in the In trays, being careful of course to return them each time to the Registry. Thus, in theory, the location and destination of every paper could be found by looking in the Register.

Before, however, a paper or document circulated, the relevant file—“docket” or “pack” in Navy language—had to be attached to it with circulation instructions, any reference “tabbed up” and any other relevant material, such as maps, photographs or signals attached. Thus, it circulated with the “whole story” and the Plans’ detailed development attached to it. After circulation it was “packed away” and the pack put into a steel cabinet until required again.

Papers of course were also given “pack numbers” but as they were all filed under subject matter the Pack Writers, of whom I became one, had to know and understand to what subject the paper referred and collect up and cross-reference any other relevant papers or packs. If they were circulating they could be intercepted at the Register or taken from the steel filing cabinets, but often a paper arrived with a new subject-heading, one which was difficult to identify as it was referred to only by its code name. For instance, one had to know that “Mulberries” were artificial harbours, but so also were “Gooseberries”, and “Whales” and “Beetles” were part of them too. If one were suddenly asked for a paper on “The loading of Phoenixes into DUKWS” for instance, one had to remember that Phoenixes were concrete caissons (and what are caissons?!) and DUKWS were amphibious lorries and there could be a different pack for each, all cross-referenced. As it was not a good thing to write too much down, we had to commit a lot of code-names to memory and to help us we were sometimes sent down to watch a new film on some just-invented secret weapon being shown to the Senior Officers in the basement.

To begin with the files were roughly divided into Sections of Operations, under Prue Nesbitt: Personnel (Margaret Burden), and Training (myself and an assistant, Jeanne Law, as this was the largest section). As the Plan became more complex and detailed, however, and all the files became part of one big operation with subjects divided and sub-divided into manageable parts, all closely over-lapping, we found ourselves each with about three four-drawer cabinets of files—roughly over a hundred each—to be understood and if possible memorised, often remembering the number of the pack as well, which made it more easily found in the Register. Quite a lot of detective work went into our daily duties as often Officers took circulating papers and packs with them in discussion with another, forgetting to inform the Registry. Also, Officers would require packs or papers on subjects whose official name they didn’t know, and we would spend a long time trying to identify and locate a paper on “something about soldiers being trained on waterproofed vehicles at Poole”. This would turn out to be the training of some Army regiments on DD tanks and we might have to get the paper from 21 Army Group or Combined Operations, which involved using the scrambled telephone, or it was circulating with another paper called merely “DD Tanks”. When the Admiral or any of the Chiefs of Staff wanted a paper or one came in marked “immediate”, or there was a Combined Chiefs of Staff Meeting, papers had to be found and prepared in double-quick time, as all these took precedence and were done instantly. A backlog of papers inevitably built up and one stayed later and later every evening “packing away” papers which had temporarily finished circulation.55

About a month after Jean Gordon commenced duties at Norfolk House, on 27 August 1943, Second Officer Elspeth Shuter arrived from Combined Operations Headquarters:56

In the Navy you rarely seem to arrive at a new job and find that you are expected. This was no exception. There were two brothers on the naval staff in Norfolk House—both were secretaries—and of course I had to go and say my piece to the wrong brother. Not that it made much difference when I had eventually found the right brother, as nobody had any idea what to do with me! […]

At this time the Naval Staff […] working under Rear-Admiral Creasy, consisted of no more than about fifteen highly qualified naval officers. My only qualification was that I had been playing about with landing ships and craft—on paper—at Combined Ops during the mounting of the North African and Sicilian operations.57 So it was into the midst of this extremely able planning staff that I had been plunged. True, there were already two Wren officers running the signal distribution. But in the Navy signal officers are a law unto themselves and thus escape suspicion. No wonder then that there was much head scratching and doubts as to the value of a WRNS officer on the staff. I was passed from one to the other, each read the letter I had brought, looked at me dubiously and sent me on to someone else! I came at last to the Staff Officer in charge of Landing Ships and Craft—short title: SOLC—who said at once that he would take me on as his assistant. I am always grateful to him for accepting me so happily. Thus, in this haphazard way, I had the good luck to become Assistant Staff Officer, Landing Ships and Craft—short title: A/SOLC—on the finest staff I could ever wish to know.

But it did not strike me in that way to begin with […] Those first days were very dreary. We seemed to be suspended in a vacuum waiting for the verdict of the Quebec Conference. 58 I could find no work to do (a situation that is always unsatisfactory: but one that is agony in a new job). I knew all too well that my presence was resented and my morale sank.

However, the Overlord plan was sold to the big chiefs at Quebec. The members of the staff who had been at the conference returned and once again the place hummed with activity. The target date for the operation was at that time 1 May 1944—only eight months distant—and there was much to be done.

Yes, the work involved was colossal. From the naval point of view it included the berthing and assembly of the greatest Armada of all time. Five naval forces, each capable of lifting a fully equipped assault division to the far shore, had to be mounted and trained. Two artificial harbours had to be created—literally created—and plans made for their assembly at the chosen sites. The supply and maintenance of the Army, once it had been put on the beaches, had to be carefully considered. All these and many other problems had to be tackled and solved during that autumn and the following spring.

Earlier in the planning stages of Overlord the Navy had said—no doubt with a thump of the table—that artificial harbours could be constructed on the far shore. At the time the idea seemed so fantastic that the Army wrote a skit on the plan called “Operation OVERBOARD”. In this a great deal of fun was poked at the Navy, especially over their artificial harbours. Suffice it to say that late in the Spring, 1944, the security boys suddenly realised that operation Overboard—which had received a wide circulation—was very near the truth. Even the imaginary date, which was 32 May 1944, was exactly the same thing as 1 June 1944, which was by then the target date of the real operation. Great efforts were made to recall copies of Operation Overboard and to establish the author. Anyone possessing a copy was singularly unhelpful in the matter. It was all too rich a situation!59

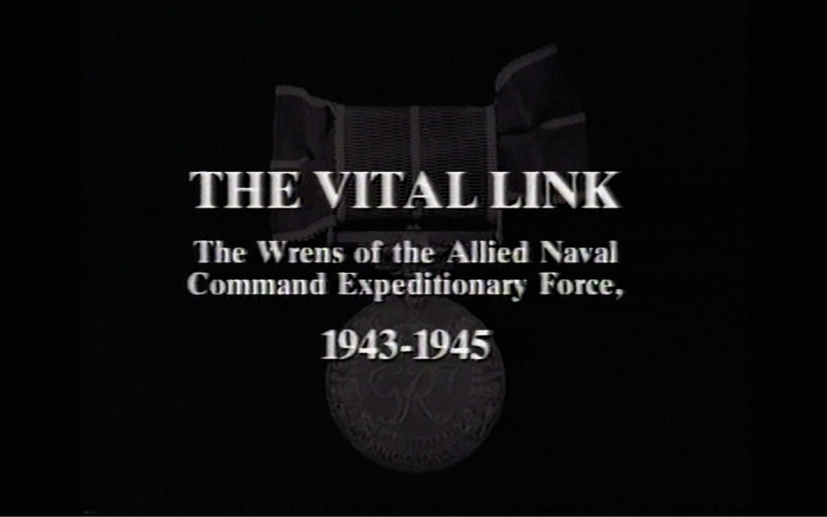

But security was no joking matter, as one of my mother’s anecdotes recalls. After the heavy casualties suffered by the Canadian landing troops in the disastrous Dieppe Raid of 19 August 1942—attributed by some, in part, to a security breach—the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, insisted on all Combined Operations planning employing an exclusively WRNS secretariat. The Wrens were, he said, ‘the only birds that wouldn’t sing’.60 Extensive research has been unable to verify the attribution of this quotation, so the epithet remains apocryphal.Nonetheless, the utmost necessity of complete security around the planning of Overlord was impressed upon the small team of Wrens from the start, as Joan Smith’s testimony for The Vital Link (1994) makes clear.61

Video 1.9. Film clip (00.22) from The Vital Link: The Wrens of the Allied Naval Command Expeditionary Force, 1943-45 (dir. Chris Howard-Bailey, Royal Naval Museum, VHS recording, col., sound, 1994), courtesy of National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth. ©National Museum of the Royal Navy.

https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12434/1979f4dc

In London, they were told they might be tailed by the Secret Service. The information they were privy to could never be divulged, even after the war. These secrets should be taken to the grave.

Writing after the war, Commander Kenneth Edwards, author of Operation Neptune (1946), observed of these WRNS: ‘I knew of no instance of even the smallest lapse of security in spite of the fact that the majority of them had access to all TOP SECRET papers from the beginning’. 62

Admiral Ramsay’s biographer, Rear-Admiral W.S. Chalmers shared this opinion: ‘integrity was a tradition of this fine women’s Service, and there was never the smallest lapse of security either in conversation or at work’.63

Elspeth Shuter remembers, affectionately, that the looser tongues in the office tended to be male:

Our staff was famous for its loud and carrying voices. How the plan ever remained a secret I cannot think. Except that I never remember hearing the actual landing area or the date mentioned in words. Of all the nice stories I know about loud voices this is the nicest. The Secretary, on the side of the house responsible for Naval Administration during the pending operation, was worried because he had not been allowed to start the Administrative orders. He was in with his Admiral one day, trying to persuade him to attend more operational meetings the better to keep in the operational picture. The Admiral replied that it was not necessary for him to attend meetings as he could hear all he wanted to know of the operational picture through the wall. “Listen”, he said, “They are talking now…” The room was hushed and through the wall came:

“Poor Sec. Admin is itching to begin his administrative orders but that old boffin next door won’t let him get going!”

I like to think that the orders were started the next day…64

THOMAS: During the time I was at Norfolk House, an appeal went out to the public to send in postcards of the coast of Normandy, maps, Michelin Guides or any other information that might help with the planning of the operation. Although I didn’t personally have anything to do with sorting out the information that was sent in, I remember the rooms with postcards stuck on the wall.65

SHUTER: All the offices had large maps of the north coast of France on the walls. Ours used to be covered with finger-prints all over the proposed invasion beaches. They were left by our many visitors demonstrating some crazy point that some crazy person had just suggested at a quite crazy meeting. Conscientiously, after one of these map-beating demonstrations, I used to go and make finger-prints on other parts of the map! In fact, so security-minded did I become, that every so often I would make a tour of the offices after everyone else had gone home and busily I planted my finger prints up and down the French coast anywhere, everywhere, other than the assault area. I hoped that in so doing I would diddle the fifth columnist—if there should be one!66

BERYL K. BLOWS: As a young and nervous Third Officer, I was appointed Personal Assistant to Rear-Admiral Tennant, on the staff of ANCXF at Norfolk House.67 […] On my first Monday morning, in my very new uniform complete with new black silk stockings, I reported for duty and, after the usual introductions, was handed a yellow duster. Thoroughly bewildered, I was taken into an inner, inner room, through locked doors. On a vast kitchen table was a relief model, beautifully made, and complete with houses, roads and the five beaches of the Overlord coast. I was shut in with my duster and told to dust. Alone, I stood and concentrated on a mental picture of the outline of the map of France—the shape of the Cherbourg peninsular eventually gave the clue. I set to work but couldn’t reach the centre without kneeling on the table, and caught my stocking on the spire of a church—Arromanches as I discovered later.68

Looking back, Third Officer Fanny Hugill recalled:

Many of the Wrens were very young—straight out of school—I was only twenty-one myself. But our standards were high. After years of war and knowing that we were trusted and our contributions valued, it was unthinkable that we would spill the beans—any beans.69

soon realised that the work was of great secrecy and importance and that we were the Headquarters for the Allied Naval invasion of Europe. We received and transmitted many signals in connection with “Overlord” referring to Mulberry Harbour, Pluto Pipe Line, etc and much information which became news items after the successful liberation of Europe. When a “top secret” message came through on our teleprinter it had to be sealed and stamped by the duty officer and then delivered to Admiralty House by whoever had received it on their machine. We were working eight-hour watches involving mornings, afternoons and nights.70

Fig. 1.10. Drawing of Norfolk House, St James’s Square, by Elspeth Shuter. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000010, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

THOMAS: I was living at a nurses’ hostel between Chalk Farm and Belsize Park at the time,71 and would travel to Leicester Square or Piccadilly Circus on the tube every morning. From the station there was the jostle of walking down the Haymarket, and by the time I got there, Norfolk House would be buzzing with activity. I didn’t work shifts, but I would generally be there all day and if the general wanted to work in the evening I would stay late and be taken home by his driver. I was never allowed to go home on my own late at night.

There was no such thing as a typical day—the work depended on whatever was going on. I usually had to attend the Chief of Staff’s conferences in the morning and evening, and the rest of the time I dealt with anything the general wanted answered or typed. After the morning meetings everything had to be typed up for the evening, and after the evening meetings everything had to be typed for the following morning, so there was very little time off. We often worked into the early hours of the morning.72

GORDON: With the appointment of General Montgomery to 21 Army Group and the decision to land initially five instead of three divisions, the task of the Naval Force had become much larger and it was thought that C-in-C Portsmouth would be too burdened with his duties in the Port to be commander of the Naval Expeditionary Force as well. So Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay became Allied Naval Commander Expeditionary Force (ANCXF) and Rear-Admiral Creasy became his Chief of Staff and both arrived at Norfolk House.

Their orders were the “safe and and timely arrivals of the assault forces on the beaches, the cover of their landings, and subsequently the support and maintenance and rapid build-up of our forces ashore”, and this was further extended “to carry out an offensive from the UK to secure a lodgement on the Continent from which further offensive operations can be developed. This lodgement must contain sufficient port facilities to maintain a force of 26–30 divisions and to enable this force to be augmented by follow-up formations at the rate of 3–5 divisions a month”. The Naval part of this operation was christened “Operation Neptune” and was the responsibility of the Naval Commander Admiral Ramsay. The overall plan for the lodgement of the Allied Forces after the initial landings and assault was called “Overlord” and General Eisenhower was appointed as Supreme Allied Commander, with Generals Montgomery and Bedell-Smith under him, and Air Vice Marshall Leigh Mallory the Air Commander. Commodore Hughes-Hallett, Chief of Staff (X) left Norfolk House for duties elsewhere when Admiral Ramsay was appointed ANCXF, and Admiral Creasy his C.O.S. But not before he had conceived the first idea of the “Mulberry” Harbour.

There followed, naturally, a big expansion of the original “X” staff at Norfolk House. Experts and specialists on every aspect and requirement of the plan arrived and set up their offices. The Mulberry expert Commodore McKenzie arrived. PLUTO, the plan to lay a pipe line under the ocean from the far shore, with all its CONUNDRUMS etc arrived too. The Signals sections grew, the Loading and Logistics Department with all its mass of paper, the Hydrographer, the experts on Landing Craft, Hospital Ships etc etc, to co-ordinate the many training of personnel and weapons and the devising of new operations to be planned to put into practice for the overall plan.

The Registry had by now moved to a large room on the first floor. The Wrens from TORCH and HUSKY had mostly left to take up commissions and their CPO had gone, thankfully, back to sea.

We had a new CPO in charge, D.H. Bennison, a quiet young man of twenty-eight who was always courteous, calling us by our surnames with the prefix of Miss or Mrs. He was “Chief” and had complete control of the situation and patiently guided us through with unerring efficiency. He would confront any member of the Staff on behalf of one of his Wrens whom he thought had been wrongly criticised. He had a younger PO to assist him, and together they opened all the incoming mail and decided what must be done. The Wrens on the Register, now extended to at least three books, were also expanded in numbers. There seemed to be hundreds of Wren Messengers who never seemed to sit down at all. Downstairs there was a typing pool, “manned” entirely by Wrens, which swelled in size daily. They typed and re-typed plans for all operations, orders for ships and craft and Naval parties’ establishments and installations, logistics and loading tables etc, etc. Everything they typed had to be checked before being “run off” on hand-operated Gestetner machines, and during all working hours there would be Wren typists asking anyone they could find “Will you check me, please?”, or huddled together with anyone willing to check their copy. Whenever there was a “flap” on to get orders out, generally late at night, everyone available went downstairs to help them collate into sets and staple together the mounds of papers of Orders to be sent out.

Sometimes it was necessary to go to the floor above ours to extract a paper from the US Navy Registry. Here we were always greeted with evident pleasure. Their officer, in fact, greeted every Wren with “Hi there Petoonia, howya bin?”. Though their Registry was equipped with a lot of complicated-looking gadgetry, extracting what we wanted was a lengthy procedure. In reverse, they expressed a gratifying astonishment at the speed with which we were able to help them, generally from memory. I think the difference was that we were supposed to know exactly what was going on and work from that knowledge, whilst they were not “in the picture” and had to rely on office procedures.

Fig. 1.11. A sketch of the Registry, ground floor, Norfolk House, St James’s Square, by Jean Gordon. The D-Day Story Collection, 1986/227, courtesy of the D-Day Story, Portsmouth. © Portsmouth City Council. https://theddaystory.com/ElasticSearch/?si_elastic_detail=PORMG%20:%201986/227&highlight_term=Jean%20Gordon

Along the corridor was the Despatch Department where Wrens dealt with the complicated procedure of packaging up, sealing and receipting any papers which had to be sent out. Quite early on in the planning of Neptune, when the receipts for Top Secret papers were duly returned to their senders, consternation was expressed by the recipient because a Wren had written her rank, as required, against her signature when receiving them, and no Naval rating was supposed to see or handle restricted papers! This posed a temporary dilemma, as to commission all the Wrens in the building, including the Messengers, would have produced not only a lengthy hiatus, but have aroused some unwelcome interest into what was going on at Norfolk House. However, this was soon overcome by a letter sent to all concerned with described us as “hand-picked and of the utmost integrity”. Whilst the first might not have been strictly accurate, the latter was, I think, eventually proved to be true. At about this stage, I believe, we all solemnly signed the Official Secrets Act!

Security was of course as tight as the circumstances allowed. We all had passes to be shown to the Security men at the door. At the end of working hours often, as time went on, long after midnight, the steel cabinets had to be locked and the keys returned to the Duty Officer. Every bit of paper, including blotting and scrap paper, had to be put away in the cabinets or disposed of into the waste paper baskets marked “Secret” which had to be emptied by the Messengers or the last person to leave. This was called “Secret Waste” and there was a small room in the building into which it was tipped and where anyone after duty volunteered to go and sit on the floor amongst the paper (and in the early hours several mice!) to do a stint of removing all pins and metal tags—paper clips were not used as they were not secure and might attach other papers to them—which would have damaged the pulping machine. Though all the Wrens working on operation Neptune and Overlord must have known something about everything that was being planned, especially the Pack Writers, and had read or heard the code names, there was so much paper moving about that no one person had the time, or indeed the need, to read it all.73

Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay had served as Commander-in-Chief at Dover and had earlier masterminded the Dunkirk evacuation, commissioning and choreographing the myriad small boats that rescued numbers of marooned allied service personnel far in excess of the original plan. As Edwards records, in May 1942 Ramsay was ‘temporarily relieved of his command and summoned to London. His absence from Dover was at that time intended to be only temporary, but he did not return to that command, for from that time on he was fully engaged in the planning and execution of amphibious operations’.74 From 25 October 1943, Ramsay:

was appointed Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Force, with the short title of ANCXF. This appointment was, in a sense, a supersession of the Commander-in-Chief at Portsmouth [Hughes-Hallett] who had, since April, been considered as the naval Commander-in-Chief designate for the invasion. It was made necessary, however, because a study of the “COSSAC Plan” made it abundantly clear that invasion in the Bay of the Seine area on the scale contemplated would impose such a strain upon the resources of Portsmouth and the neighbouring ports that it would be physically impossible for the Commander-in-Chief in that area to assume any additional duties. Moreover, it was even then obvious that the task of the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief of the Expeditionary Force would be so great and so onerous that it would call for the full powers of a man of exceptional ability.75

When Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay (together with his Staff Officer Plans, Commander G. W. Rowell—‘SOPO’) arrived as Allied Naval Commander Expeditionary Force at the end of October 1943, and ANCXF was established independently of COSSAC, General Morgan remained on the staff but was assigned to the role of intelligence coordinator. The planning for Overlord was now assumed by the three service commanders: Montgomery (Army), Tedder (Air Force) and Ramsay (Navy). It was the responsibility of the Naval part of the operation, code-named Neptune, with air support, to put the landing forces and their equipment on the Normandy beaches, and to maintain their supplies. In this unbelievably complex logistical task, Ramsay’s resolute eye for detail was guided by the strategist’s understanding that success depended on planning to the nth degree.

Shuter remembered with a shudder that:

Any major adjustment made by any one of the authorities concerned sent repercussions shivering through the others which were felt down to the smallest planned detail. […] No one who has not tasted of combined operational planning—joint planning—can appreciate the difficulties and Overlord was no exception. Perpetual striving for agreement was called for between our Navy, Army, Air Force, the Ministry of War Transport, the comparable American bodies and various other authorities involved. […] It needed cool, calm men with an infinite capacity for work; the patience of Job; the self-restraint of a super-man, and an unfailing sense of humour. Luckily we had just such men. Despite all our troubles the plan was well in hand by December 1943. Then we struck a sticky patch.

It must have been about Christmas time that Field Marshall—then General—Montgomery left the Eighty Army in the Mediterranean and came home to take over the command of 21 Army Group. 21 AG was too large a body to be housed in Norfolk House but they worked nearby at St Paul’s School, Hammersmith.

General Montgomery took one look at the Overlord plan and demanded two additional assault divisions. Consternation reigned. It was comparatively easy for the Army to produce the troops, presumably they would just be going in earlier than had been originally intended. But for us it meant additional ships and craft for two assault forces. It meant more staffs and crews; more training, more assembly and berthing facilities; more escorts, more minesweepers, and the survey of additional beaches.

Within a few days of General Montgomery’s return General Eisenhower arrived to take up his appointment at Supreme Commander. I believe he took one look at the tenseness of the situation and very wisely went on leave!76

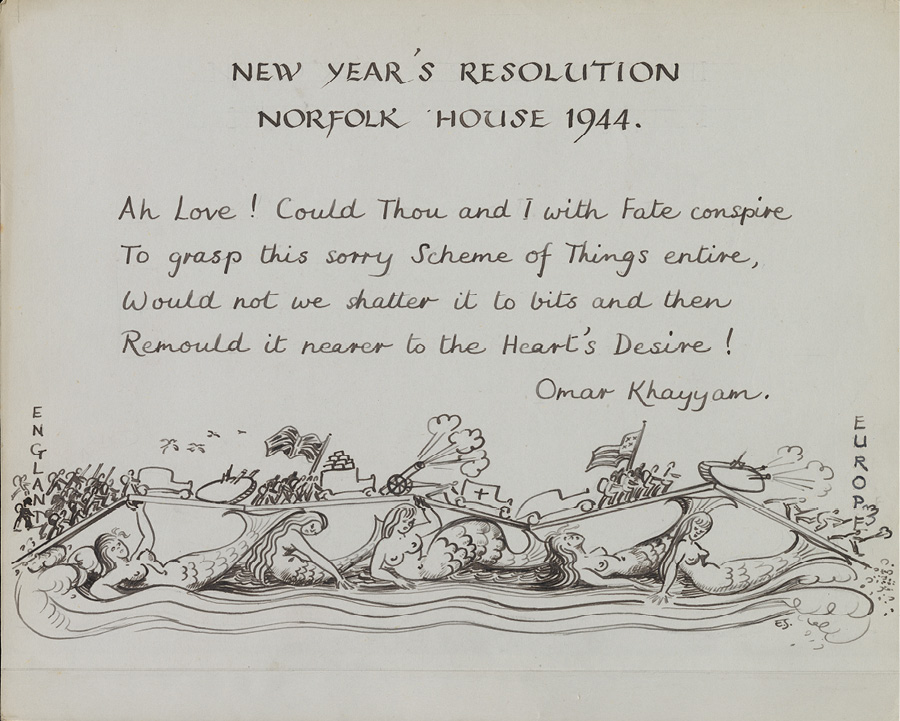

Fig. 1.12. ‘New Year’s Resolution Norfolk House, 1944’. An illustration by Elspeth Shuter. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000012, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

The nightmare that followed lasted for weeks. Were the beaches suitable for a broadened front? Could the shipping be found? Could the men be trained in the time? Was it feasible? Was it really desirable? Events have shown that it was feasible and was desirable. But chaos reigned while the question was thrashed out.

During these wretched weeks of indecision while discussions were taking place on the highest level we couldn’t afford to sit idle. So during this time planning proceeded in triplicate. Anything done had to give the answer for a three, a four and a five divisional assault front. It was an exhausting and trying time. But even under this additional strain I never saw our staff obstructive, uncooperative or bad tempered. They were great. Always they took the broad view—the success of the operation as a whole.

By the beginning of February the joint plan became firm on the basis of a five divisional assault front. In the original plan approved at Quebec there were to have been one American and two British assault forces. Now two new assault forces, one American and one British, had been conceived and now had to be born. In addition each of the allies still had one follow-up assault force which was to land on the second tide of D-Day as agreed in the original plan. Seven assault forces in all!

To ease the situation it was agreed that the assault on the Mediterranean coast, which had previously been planned to synchronise with the Normandy landings, should be delayed. It was now that it was also agreed to make the Normandy target date the first of June instead of the first of May. This gained us an additional shipping from the Mediterranean as well as an extra month’s new production both from this country and the United States. It also gave four more precious weeks in which to train the new forces.

We had kept abreast as far as possible by planning in triplicate, but naturally the writing of the naval plan itself had been held up during this period of indecision. For all this, under great pressure, our outline Naval Plan was out by the middle of February, and the detailed Naval Plan a fortnight later. To achieve this the staff, down to the last Wren rating, had shown a splendid understanding of the word “work”. But despite these efforts and because of the increase in the size of the assault it was never possible to catch up the lost weeks entirely. This had serious repercussions which finally resulted in those who took part in the operation being overwhelmed with sheets of amendments to their operational orders.

Work rose to a crescendo during the Spring 1944. It reached the stage when you didn’t expect to start any of your own work before seven o’clock at night. I only had some appendices to produce for the operational orders. How people who were writing the orders and were responsible for tying up the detail ever stayed the course was a miracle of endurance. The day was spent in coping with an ever-increasing stream of signals, visitors, and the incessant ringing of the telephone. It was exasperating work always calling for adjustments and amendments. Concerning detail, nothing seemed to stay the same for two days, two hours or even two minutes together. More often than not I used to arrive home towards midnight. As I walked from the tube to my bed-sit I would find that I was sobbing gently to myself through the black-out. I was not unhappy; it was just nervous exhaustion from the countless irritations of the day’s work.77

GORDON: Though most of us lived in WRNS quarters dotted about London, some Wrens came to work from their homes and of course all had weekend leave from time to time. Then listening to one’s older relations and other civilians pontificating, as everyone did, about when and where the “Second Front” should take place was quite a strain. At some stage I remember being with my sister on leave in Brighton, a restricted area of course, and seeing what she described as “aircraft carriers” passing across the horizon. Something warned me not to contradict her, for though I had not yet seen them myself, these were parts of the “Mulberry” being towed to their assembly areas.78

THOMAS: The atmosphere in Norfolk House was very focused. Everyone seemed to be concentrating on the job, so there were no little cliques standing around and talking. There was always a feeling of confidence among the staff—there had to be, with an operation of that magnitude. Everything depended on getting it right. We knew that the lives of thousands of troops were at stake.

Everyone worked very long hours, often well into the evening. There were no rigid office hours and no clocking on. You just worked when you had to work, and left when you were told to go.

There was certainly no official leave, and I don’t think I went home to Swansea once in the twelve months I worked on the invasion plans. I had the weekends off, and sometimes visited my cousin in Shaftesbury from Friday night until Monday morning. I would usually spend most of my time there catching up on sleep!79

GORDON: There were, of course, besides Admirals Ramsay and Creasy, many high-ranking officers working in the building, but except for when on the rare occasions Naval Captains and other senior officers could be seen queuing with the rest of us for their ration (one each) of an unexpected consignment of oranges or bananas, one’s duties confined on mostly to the Registry and the people there. Going down in the lift very late one evening, I was joined in it by Admiral Ramsay, who was astonished at the late hour I was working. He had, of course, been working too. Some days later a book appeared in which we had to sign on and off duty. This was supposed to regulate our working hours (most of us were by then doing an average of eighty hours a week) to a reasonable number, but inevitably I suppose, it became a means of disciplining us, by the Wren officer in charge, who was not allowed beyond the low barrier which contained us in the Registry, for being late in the morning—until “Chief” intervened! A “normal day” was supposed to be from 9am to 6.30pm. This seldom ended before 7 or 8pm, and often stretched after midnight. Then there were other days when one came in later and stayed later, or had an afternoon off—in theory. There were often long Friday to Monday, or short Saturday pm to Monday am, weekends when one could go home, taking one’s ration cards of course (and stealing a basinful of sugar from Wrens quarters if one could dodge the Wren stewards). Lunch hours were generally a sandwich and a mug of tea fetched from the canteen and taken at one’s desk—though sometimes it was possible to get out for lunch with a lunch voucher to the value of 1/-3d. Lyon’s Corner House did quite a good one for this, and if you saved them up you could have quite an expensive meal. I once did this at the Berkeley Buttery, much to the embarrassment of the friend I was lunching with and the rage of the waiter who had to count them up! When we got back to quarters, at all hours of the night, having stepped over the sleeping bodies of people sheltering in the Tubes, we found even the “late supper” we had ordered was inedible. There was always demerara sugar (laid for breakfast), bread and cheese, and sometimes a pan of congealed Naval cocoa on the stove. This is what I mostly ate during that year and some of us got very fat and some even got ill.

In spite of our late working hours, we were still expected to take our turn at fire-watching in the quarters, sitting up all night waiting for the siren to “man” a stirrup pump on the roof. At Norfolk House we were also on a fire-watching rota and had to stay the night there and work the switchboard in the basement to alert those still working in the building.

Despite the importance of our work, we were all young and had the usual high spirits of normal girls, and there was a lighthearted atmosphere, and hilarity, such as when with the windows open in summer, a gust of wind blew some Top Secret papers out onto the street below and we had to yell to the doorman to secure them while we rushed down to get them.

Periodically, we went through Gas Drill, when everybody in the building at the sound of a warning bell sat solemnly at their desks or went about their duties wearing their gas masks! Communication with each other was difficult, punctuated by the loud “raspberries” emitted from the contraption by anyone breathing too fast, and made much worse by the gales of giggles which ensued. Answering the telephone presented its own problems, and whoever was at the other end of an incoming call must have used their imagination quite creatively in deciphering what was going on!

Though one of the telephones was “scrambled” we could make and receive outside calls on the others quite normally and make our free-time arrangements. Often young men we knew in other arms of the services rang us up to say they had got some unexpected leave, and we generally knew it was because they were about to be embarked on some operation or training which was in our files. Neither of us would have discussed this of course.

Except for occasional encounters in the lift at Norfolk House […] one did not often meet Admiral Ramsay or other Senior Officers face to face. They had their own appointed offices and rest areas and so did we, and there was no opportunity for mixing. But the atmosphere of an HQ such as ANCXF is set by the conduct expected of each other from top to bottom, and it was clear from the very beginning that this was to be of a high standard. Though Admiral Ramsay himself must have been a man of great dynamic energy and vision (he had organised the rescue of the BEF from Dunkirk in the “little ships”, and was afterwards known as “DYNAMO”, the name given to the operation), he appeared to us whenever we met him in the lift, to be a quiet, dignified man who spoke and listened to us with evident interest and courtesy. But he set a pace himself of relentless dedication to the task in hand. People worked punishing hours without question, staying late until a job was properly done and completed. It was necessary, of course, but no one had to be told. On the contrary, concern was expressed by the Admiral himself at the long hours the Wrens were working and he tried to regulate them.

Admiral Creasy seemed to be a much more “outgoing” character with a breezy sort of approach. He gave us a stirring talk before we left for Southwick Park.

Captain Moore, our direct “boss” in the Registry, as the Admiral’s Secretary, was often approached on our behalf by our Chief PO and seemed always fair and reasonable in his supervision of our general conduct and duties. “Compassionate” leave was always granted without question.

The Chiefs of Staff, although we generally knew they were in the building, kept their arrivals and departures as inconspicuous as possible for obvious reasons, but the “pace” generally quickened on their arrival. Busy Staff Officers with huge responsibilities and masses of work to be got through in a limited time, occasionally became impatient. Many of them had already served in many operations at sea; some were still suffering from the effects of this. One Officer, suffering from a stomach ulcer, always had a bottle of milk under his desk. Others sometimes got impatient with Wrens who could not produce the pack or paper they wanted immediately. We were not, after all, entirely familiar with nautical nomenclature and technical terms: “my dear girl, you must know what hards are!”,80 and then realising, “no, why should you?”, and apologies. After all, an enterprise such as the one on which we were all working was a unique experience for everyone and we certainly, like many of the RNVR and RNR Officers and men, had to learn it as we went along. But in the main we were welcomed and appreciated.

Many of the Wrens had had the advantages of a higher education than that of the young men they were replacing to go to sea. Some had had a good secretarial training or held a job before they joined, and officers who had suffered the efforts of stoker81 doubling as typist in small ships must have been glad of the change!

We called all officers “Sir” and saluted them. Both compliments could, if necessary, be used to one’s advantage in attracting or repelling attention! They called us “Wren” and then our surname if they knew it—and they mostly tried to learn them. They did not use our Christian names on duty. This produced a formal and disciplined atmosphere necessary to the serious urgency of the task on which we were all engaged.82

By this stage, life at Norfolk House had become an intense ritual indeed. Wrens worked around the clock, forty-eight hours on and twenty-four off. They kept a washing kit and a change of clothes at the office. They ate routinely at Lyon’s Corner House and The Trocadero, sometimes Vega. Ramsay held staff meetings morning and evening to plot progress, with operational staff conferences held every Friday afternoon. There was a regular succession of high-ranking officials passing through the doors: Eisenhower, Montgomery, Leigh-Mallory, Tedder, Mountbatten. The complex choreography of the massive sea-borne assault eventually resulted in orders published in volumes four inches thick, running to some 1,100 pages.83

Our operational orders were finally in print about the middle of April. From then on it was a question of making as few alterations as possible as any change meant yet another amendment to be put in by hand when the orders were opened on the eve of the operation. Towards the end of April we quietly packed our bags and disappeared into the country.84

1 Foreword to Eileen Bigland, The Story of the WRNS (London: Nicholson & Watson, 1946), p. ix.

2 Chris Howard-Bailey (dir.), The Vital Link: The Wrens of the Allied Naval Command Expeditionary Force, 1943–45, VHS recording (Portsmouth: Royal Naval Museum, 1994).

3 WW2 People’s War: An archive of World War Two memories—written by the public, gathered by the BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/about/

4 Phyllis ‘Ginge’ Thomas (Leading Wren), ‘Ginger Thomas’s D-Day: Working for Cossac’, WW2 People’s War, A2524402, 16 April 2004. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/02/a2524402.shtml

5 Fanny Hugill (Gore-Browne), (3/O Wren), ‘A Wren’s memories’, Ramsay Symposium, Churchill College, Cambridge, 6 June 2014, Finest Hour 125, Winter 2004–05, p. 19. https://winstonchurchill.org/publications/finest-hour/finest-hour-125/a-wrens-memories/

6 In later years, Fanny Hugill (1923–2023) was a devoted supporter of remembrance anniversaries and memorial tributes to Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay (a statue erected at the signal station at Dover Castle in 2000, and a plaque at Château d’Hennemont—now the Lycée International de Saint-Germain-en-Laye—in 2017). She ‘served as “chairman” of the WRNS Benevolent Trust, was a trustee of several other charities and in 2016 was appointed to the Legion d’Honneur’ (Times obituary, 11 October 2023). Her papers, together with those of her late husband Lieutenant-Commander Tony Hugill DSC, Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (1916–1987) are held at the Churchill Archive Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge.

7 Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force.

8 Penny Summerfield, Histories of the Self: Personal Narratives and Historical Practice (Abingdon & New York: Routledge, 2019), p. 15.

9 Annette Kuhn, Family Secrets: Acts of Memory and Imagination (London: Verso, 2002), p. 127.

10 Janet Gurkin Altman, Epistolarity: Approaches to a Form (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1982), p. 4.

11 Jenny Hartley, Millions Like Us: British Women’s Fiction of the Second World War (London: Virago, 1997), p. 126.

12 Eva Figes (ed.), Women’s Letters in Wartime, 1450–1945 (London: Pandora, 1993),

p. 13.13 It should be noted that any spelling or punctuation errors in original sources have been left uncorrected in quotations.

14 Ibid., p. 15.

15 Franz Kafka, Briefe an Milena, quoted in Altman, Epistolarity, p. 2.

16 Summerfield, Histories of the Self, p. 37.

17 Quoted in ibid., p. 38.

18 Ibid., p. 39.

19 Ibid., p. 44.

20 Figes, Women’s Letters in Wartime, p. 9.

21 Tamasin Day-Lewis, Last Letters Home (London: Pan Books, 1995), p. 3. Whilst this fact is indeed true, scholarship on epistolary communications continues to adapt to changing technologies, as work by, for example, Margaretta Jolly and Liz Stanley demonstrates. See Jolly, M. and Stanley, L., ‘Epistolarity: Life after death of the letter?’, Life Writing, 32: 2 (2017), 229–233.

22 Day-Lewis, Last Letters Home, p. 2.

23 Hannah Roberts, The WRNS in Wartime: The Women’s Royal Naval Service 1917–1945 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2017), p. 99.

24 Jean Gordon (Irvine) (Leading Wren), ‘Training in Portsmouth’, unpublished personal testimony, D-Day Museum Archive, Portsmouth, H670.1990/1.

25 Audrey Johnson, Do March in Step Girls, quoted in Christian Lamb, I Only Joined for the Hat: Redoubtable Wrens at War (London: Bene Factum Publishing, 2007), p. 30.

26 Jeremy A. Crang, Sisters in Arms: Women in the British Armed Forces during the Second World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), p. 36.

27 Ivan Moffat (dir.), WRNS (Ministry of Information), November 1941 (Imperial War Museum, UKY 344). https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1060006265

28 Brenda Birney, The Women’s Royal Naval Service: A World War Two Memoir (privately published, 2016), p. 2.

29 Westfield College, Hampstead was opened in April 1941 as a London-based WRNS ratings training centre, in addition to the regional ports’ depots at Devonport, Chatham, Portsmouth and Liverpool (Roberts, The WRNS in Wartime, p. 129).

30 Birney, The Women’s Royal Naval Service, pp. 3–4.

31 Penny Summerfield, Reconstructing Women’s Wartime Lives (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), p. 50.

32 Roberts, The WRNS in Wartime, p. 112.

33 Neil R. Storey, WRNS: The Women’s Royal Naval Service (London: Bloomsbury/Shire, 2017), p. 31.

34 Roberts, The WRNS in Wartime, p. 107.

35 Lamb, I Only Joined for the Hat, p. 93.

36 Roberts, The WRNS in Wartime, p. 134.

37 Lamb, I Only Joined for the Hat, pp. 59–60.

38 Peggy Scott, They Made Invasion Possible (London, New York, Melbourne: Hutchinson & Co., 1944), p. 7.

39 Roberts, The WRNS in Wartime, p. 113.

40 Ibid., p. 116.

41 Summerfield, Reconstructing Women’s Wartime Lives, p. 70.

42 Crang, Sisters in Arms, p. 30.

43 Glenny’s Brewery Ltd, Wikipedia: http://breweryhistory.com/wiki/index.php?title=Glenny%27s_Brewery_Ltd

44 Lucy May Child, 1888–1980, married Grace Prior’s closest brother, Justin Joshua Simeon Steele (1880–1927) who had served in the Welsh Regiment in the Boer War. They had a son, Justin ‘Arthur’ (1911–1940) and a daughter Margaret ‘Peggy’ (1914–1988), before he went off to Flanders, where he contracted syphilis. After the First World War he returned to his employment as a porter with the Great Western Railway at Cardiff station, rising to foreman before his deteriorating mental health resulted in him being committed to Whitchurch Mental Hospital where he died of dementia paralytica in 1927 at the age of forty-six. In 1935, Lucy married one of Justin’s workmates, Bert Arthur (1874–1960). She was forty-six; he was sixty-one. When Bert retired (aged 65 in 1939), they moved with her daughter Peggy, to Bert’s native Catcott, on the Somerset Levels. Lucy’s son Arthur (also a railway porter at Cardiff) stayed behind, but died of bronchial pneumonia in February 1940, aged twenty-eight. Joan Prior spent summers with Aunt Lucy in Cardiff before her remarriage.

45 Dame Vera Laughton Matthews, Blue Tapestry (London: Hollis & Carter, 1948), p. 190.

46 Roberts, The WRNS in Wartime, p. 129.

47 Ibid., p. 130.

48 ‘Again and again women cite uniform as being the key factor in their choice of service’. Virginia Nicholson, Millions Like Us: Women’s Lives in the Second World War (London: Penguin Books, 2011), p. 145.

49 Angela Mack (Wren), quoted in Crang, Sisters in Arms, p. 49.