2. Coming of Age

(Southwick Park, Summer 1944)

©2024 Justin Smith, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0430.02

Southern England was enjoying a spring heatwave when ANCXF moved out of London on 26 April 1944 and were installed at Southwick Park, near Fareham in Hampshire, which was to be Admiral Ramsay’s HQ until September. Ramsay’s biographer, Chalmers, describes Southwick as:

A moderate-sized Georgian house in the ancient Forest of Bere, some ten miles north-west of the city [of Portsmouth]. It had been requisitioned by the Admiralty as the Navigation School, and having become a “stone frigate” was re-christened HMS Dryad in accordance with Service custom. Ramsay, being a countryman, was delighted with his new surroundings, for instead of picking his way along the crowded pavements of London, he could take his exercise in the forest glades and rhododendron groves of this beautiful park. 1

JEAN GORDON: Before we left London […] after being assembled and addressed by Rear-Admiral Creasy who wanted to “put us in the picture” for the next phase […] we were told of the strict security measures which would be enforced. Our whereabouts of course must not be known so the only address we could give our relatives would be “Naval Party 1645” and an Admiralty No. No diaries must be kept. No cameras, of course, and no telephone calls could be made to the “outside”.2

our Battle Headquarters at Southwick Park were in the heavenly country behind and a little to the west of Portsmouth. SHAEF was to bury itself in a dank, dark wood a mile away, while 21 AG was already concealed in the woods and copses around our park.3

‘BOBBY’ HOWES: 21 Army Group men put up their tents in the park where they were well screened from aerial view by the trees, and General Montgomery’s caravans were nearby whilst he took up residence in Broomfield House [on the Southwick estate, codenamed ‘LIMEKILN’]. General Eisenhower and his staff were a couple of miles away at SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) and all was ready.4

SHUTER: The Portsmouth area held the greatest concentration of shipping; provided the shortest sea passage—about 100 miles—to the Normandy beaches; and was to play the biggest part in the assault and subsequent support of the operation.

Arriving by train and bus, by lorry and by car, we took up residence in the big house and in the huts which were in neat rows outside the front door. There was not the least vestige of camouflage about those naval Nissens; they glistened in the sun! The Admiral’s flag was duly hoisted.5

Ramsay wrote to his wife:

I’ve a lovely large room as an office and a bedroom next door. The mess is in the library and is quite comfortable, though the food is very plain. The rest of the staff are frightfully squashed up, commanders and below sleeping in dormitories of twelve and sixteen; Wren officers in two-tier bunks, twelve in a room. Surroundings are nice and all are taking the discomforts in the right spirit…6

GORDON: Our quarters were in a brick-bungalow type building to the south-west of the main house. We slept in the usual double-berthed bunks with an “ablution block” of lavatories and wash-basins attached to the building. Close by was a surface air-raid shelter into which we had to go when there was a Red Alert, clad in our bell-bottomed trousers, a seamen’s jersey and tin hits, issued for the purpose. The raids were more alarming from the noise of the gunfire from the ships and gun emplacements in Portsmouth and on the surrounding hills than from bombs dropped by enemy raiders trying to fly up the Solent.7

About 150 Wrens slept and messed in huts on the grounds, and sixty Wren officers slept in three rooms at the top of Southwick House. Facilities were limited. There was one bathroom and one loo on the top floor. Tolerance and tidiness were essential, and mixed together, day staff and watchkeepers found sleeping in the day chancy. Still, to be out of London was wonderful, and we made lasting friendships.8

‘Ginge’ Thomas, as the later correspondence testifies, became Joan Prior’s closest Wren friend, although during their time at Norfolk House they had worked separately because Ginge was seconded to General Morgan. Four years Joan’s senior, before joining Swansea Corporation she had worked as a demonstrator for Imperial Typewriters, recruited for her incredible speed and accuracy—skills which served her well in ANCXF. Of their move to Southwick Park she recalled in 2004: ‘I have a very clear memory of sitting in the back of a lorry with my friend Joan Prior, holding on to our typewriters and duplicators’.9

GORDON: Our steel cabinets and office equipment, which we had packed up ourselves after normal duty before leaving London, arrived with us and was placed in Nissen huts erected alongside the main house on the north-eastern side on part of the driveway. Next to us was the Meterological hut with the “weather men”. The rest of the operational staff were in offices in Southwick House itself.10

Kathleen Cartwright recalls some disappointment at leaving the capital:

Most of the girls, having been in London for some time, were sorry to leave to go to a remote area and there were groans as the coach set off. However, being a cheery crowd, with the usual British spirit, everyone settled down to accepting a change of venue. The spirit was flagging somewhat when our destination was reached. We came to a pretty village consisting of about two dozen houses. Masses of barbed wire and an endlessly long drive brought us to a typically old type of English Manor house […] To the rear of the building were two long prefabricated sheds, still being prepared for us. The water was just being laid on and we had to scramble over planks to reach our respective quarters. I was quartered in a long narrow room with 14/15 double bunks down each side of a narrow space.11

Fig. 2.1. Wrens of ANCXF at Southwick House, Summer 1944, courtesy of the Royal Military Police Museum.

SHUTER: A spy could have had his fill in the Nissen huts whose owners all possessed copies of the operational orders.

When we first arrived the lighting and telephone installations were not yet completed so workmen were still roaming round […] One day an officer locked his hut when he left it at lunch time. On his return, however, he found a workman busy with his wiring, but standing on a chart, with one boot on the American assault area and the other on the British!

If I were a German the sudden appearance of rows of Nissen huts would in itself tell me that extra people were now living or about to live in those parts. But on one point those in charge of security were very firm: no one might walk at random across the grass, as tracks made in this way show in air-reconnaissance photographs. So we had to keep to the paths!

Sometime after we had arrived an unsightly barricade of barbed wire was slowly unwound round the house—protection against paratroops—but it was not completed until after the operation had been safely launched! However, as it happened, there were apparently no spies, no air reconnaissance, and no paratroops, so we came through unscathed…

The security people were also given a last minute cause for concern for, towards the end of May, various code words used in the operation appeared in the crossword puzzles of a daily newspaper! Overlord and Neptune—code names for the operation itself; Omaha and Utah—code names for the two American beaches; Mulberry and Whale—code names for the artificial harbours and one of its components. However, on investigation, it appeared that there had been no intended breach of security. But it did seem ominous at the time! I understand that the author of the cross-words was not aware of the significance of these code words. Probably he had overheard them used in conversation in the clubs. When you are eating, sleeping and living immersed in the atmosphere of an operation of this type, it becomes your life and so does its vocabulary…12

It need not be supposed that, with the production of the operational orders, the work was over for ANCXF. There was still much to do. It is one thing to launch an operation but the effort will be wasted if plans are not made to sustain the armies after the beachheads have been secured.13

CARTWRIGHT: We worked the same hourly watches as in London, and every third day we had a turn on night duty. After a particularly tiring night we would fall into bed exhausted, only to be awakened about an hour later when a case would be banged on to our feet. Under the bunks was the only place to keep our cases and when the stewards swept the room, they hurled the cases on to the beds, regardless of any occupants. Nicely dropping off to sleep again, we could be wakened by chattering as off-duty Wrens prepared to go on duty after lunch.

The less said about the food, the better— cheese and minced beef dishes. On night duty the only meal consisted of corn beef, with margarine, together with crumbly bread from which to make sandwiches, but there were flies creeping around all the time which was off putting. I was lucky to have received some jars of jam from home, but with wasps hovering around, it was almost impossible to eat it.14

Wren J.H. Prior, 41801

Naval Party 1645

Friday 19th May 1944

Dear Mother and Paddy,15

I have just received your letter written on the 17th and was so pleased to get it.

I don’t know why you haven’t heard as, as you say, I have written to you. However, I suppose by now you’ll have heard from me.

I am now almost used to being here and little by little our troubles are being smoothed away. The food situation which was grim for a while is now practically O.K. and we really mustn’t grumble.

The washing and bathing front is still very sticky and if you’re not very enthusiastic about it, this is a perfect Paradise. However, we in our cabin always manage to see the funny side of everything, and if there isn’t a funny side well we make one. Some time ago we had to get up in the night on account of a siren—a very rare occurrence, and you would have laughed. There are eight of us in a room which is not as large as your bedroom—nowhere near, and when we all tried to get up in the dark and all at once, things really started. After you’d been doing up your shoe for some time and wondering why your foot was moving around you discovered it wasn’t your foot at all but someone else’s. Then we had to hunt for steel helmets! At one stage we were all without exception underneath our beds groping wildly for these and each getting hold of shoes or slippers by mistake. The next problem was getting downstairs—and that is a problem! The staircase is steel, narrow and very twisty and you almost join a Suicide Squad when you descend even in daylight. After the descent in the middle of the night I thought seriously about applying for Danger Money. Needless to say I’ve fallen down them once, fortunately doing no damage, and Ginger trod in a fire-bucket which was cunningly tucked away in one of the many angles of the staircase, getting soaked almost to the knee in the process, but nevertheless we still come up smiling.

The other night we were roped in for fire fighting practice or something and the instructor having given us the details of where the bomb had fallen and just what it might do announced that the next step was to produce a stirrup pump and undo it and bring it into play, quicker than it takes to tell. He then dived for the pump himself and began to undo it. Well, we were all in hysterics, he just couldn’t get it undone. After about 3 minutes Elsie16, one of the eight in our cabin, tentatively suggested that the fire had got rather a hold by this time and how about it, and he said, “Oh, well, this wouldn’t really happen, it’s just that someone’s done it up the wrong way”. It may not sound funny, but believe me, we were just curling up with laughter.

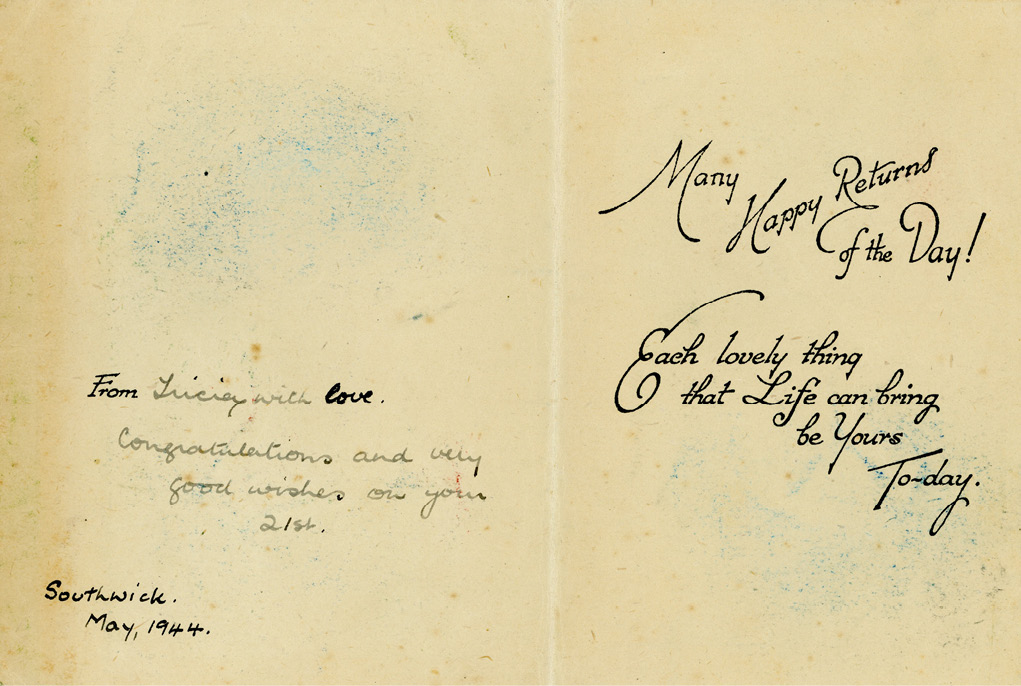

I’m awfully pleased that you’re sending me a cake, although I do feel rather mean at taking your rations, but I had been feeling rather flat about the whole thing, until your letter arrived and then I told one or two of the girls, including my pals in the cabin and they insist that my 21st must not go by unnoticed, so goodness knows what sort of a party I’ll have, but I know I can rely on them to think of something bless them. Thank Geg17 for icing it for me, it makes such a difference to the appearance of it, and in fact thank you all.

Thanks for sending on Ron’s two letters which I was very pleased to get.18 He seems to be back at base again after being at the front, because the last letter I had was dated the 1st April and these were dated 30th April and 1st May, so that he’s been away about a month. However, he continues to be O.K. although I think he’s rather worried about his Dad. I don’t know whether he’s heard from home or not, but he says “Judging by what you say, Dad doesn’t seem to be improving etc,” as though what I said was all he had to go by.

I’m so glad your neck is better Dad and hope you don’t have any more trouble with it.

Thanks too, for sending the Sunday Express so that I could read Sitting on the Fence.19 It’s the only newspaper we ever see, so you can tell it’s in great demand.

Work still remains pretty hectic and most days there’s someone in the office from 7-30 a.m. until about midnight, although we only do a late duty every three nights, so it’s not so bad as it sounds. When you’re in early—at 7-30—you get two hours off from 1 until 3 in the afternoon which is rather nice, as if the sun’s out it’s very pleasant. Jo20 and I are early together, and we usually go for a spin on our bikes to one or other of the neighbouring villages and back. Apart from the discomforts and not being able to get home, I love it here as the country is so beautiful and at this time of the year there’s such a lot doing in the way of farming.

Gosh, this typing is pretty awful, but I’m having to rush it to get it to press in time. Life here, is always rushing for something or other. When lunchtime arrives to-day, we’ll rush lunch and then rush a bath, as it’s our bath day to-day, and if we leave it till to-night we’ll have had it as the water will either be all hot and no cold or vice versa, or even yet another alternative—as with last night—there’ll be no water at all!

By the way, if Bessie21 ever sees Richard Hudnut “Three Flowers” Vanishing Cream (which I doubt), could you ask her to get it please. Oh, no, never mind, I’ll write to Bess when I’ve finished this and ask her myself, then I can thank her for getting my Daily Mirrors, etc.

I’ve written to Geg and the children and I also wrote to Charlie22 this week, so I suppose by now they’ve heard from me.

I hope all are keeping well and not doing too much work—a thing I never believe in—and keeping smiling. We’re hoping not to be so cut off from the world now, as Jo’s wireless has arrived and we’re going to try to fix it up tonight.

Last Wednesday, Betty23 and I were half-day and we went into the nearest large town24 and went to a cinema in the afternoon and had a very pleasant meal in the evening. We saw Bob Hope and Paulette Goddard in “The Cat and the Canary” and another film with Betty Hutton which we’d seen, “The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek”. It was quite a pleasant change.

This morning Ginger and I have been as greasy and oily as a couple of E.R.A.s25 or stokers, as we’ve been cleaning the duplicating machine which was thick with black ink and grease. However, once more we’re clean and so’s the machine, praise be.

I think that’s all the news now, so I’ll say Cheerio, and God bless and thanks for everything.

With love from

Joan xxxx

P.S. Stroke Jimmy26 for me.

Fig. 2.2. Birthday card from Tricia Hannington (Wren) to Joan Prior, Southwick Park, 24 May 1944. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

HOWES: I was billeted at South Lodge next door to the village pub called The Golden Lion. My room was in the attic! Our work area was in the cellar at Southwick House where a telephone exchange had been installed together with teleprinters. The cellars were a series of whitewashed tunnels with arches leading off in different directions—one to the boiler room for central heating, then off to the left the teleprinter room, and on the right the telephone exchange. This was a very large room with a concrete floor. The telephone exchange was down the centre with my table facing it. There were fourteen positions for operators and the switchboard was equal in size to a civilian exchange serving a town of 45,000 people.

The most important Officers had “Clear the Line Facilities” which meant that we had authority to interrupt calls for them if the person they wanted to speak to was already engaged. When they called a blue lamp glowed beside their number on the board. The Exchange was manned by an equal number of Wrens and men of the Royal Signals Corps, 21 Army Group. As the Royal Navy was the Senior Service I was in charge and I have to say that the men accepted me very well. There was a daily roster of watches and a rest room where everyone could take a rest without going off duty. The drinking of tea or smoking was strictly forbidden because the board was constantly busy.

All the telephones of the Top Brass had scramblers attached, and in conducting a conversation involving secret information the caller would ask: “can you scramble?”. If the answer was yes they both switched on their scramblers and the conversation sounded like Donald Duck talking to anyone trying to listen in.27

Patricia Blandford was a Second Officer Wrens in charge of telephone switchboards at the nearby Under Ground Head Quarters (UGHQ) Fort Southwick. This subterranean network of tunnels buried in the chalk of Portsdown Hill was accessed ‘down a steep flight of concrete steps (149) into a steel-lined tunnel. There was a large room with plotting tables, and small tunnel-shaped rooms equipped with teleprinters and switchboards, offices with desks and filing cabinets, a galley and wardroom, dormitories and wash-rooms […] I made frequent trips to Southwick House to train switchboard personnel there. Red-capped Military Police were everywhere and it was quite obvious that something special was going on’.28

GORDON: Though most of the plans had been completed and the Orders gone out, so that the typing pool was much reduced in size and many of the messengers drafted elsewhere, there was still a lot to do and we in the Registry were still kept very busy dealing with papers on the “build-up” and “turn-round” of the Naval craft which would be transporting all the supplies and personnel to the Assault Forces long after D-Day itself.29

MARGARET BOOTHROYD: The teleprinter room was in the cellar of the house and there was a chute down which messages came from upstairs. We had a direct line to the Admiralty and the work was very, very busy and tiring too. We worked three eight-hour watches through the twenty-four hours, which was quite hard. We found working through the night difficult at first and just had breakfast then fell into bed. Following a nightwatch we then worked in the evening of that same day. Then next day in the afternoon, early morning the following day and then night watch on that same day, so it was very tiring.30

CARTWRIGHT: The teleprinter room was a hive of activity and we could never relax for one moment as we sent signal after signal in connection with the coming most important event of our lives— the liberation of Europe and the end of the war. Whatever the discomfort, no-one objected; everyone was too intent on their work and the small part we were playing in this moment of history. I welcomed the change from routine when I was transferred for a short time to the deciphering room, which overlooked the official courtyard at the front of the building. We witnessed the arrival and departure of some very important and high-ranking officials. I shall always remember glancing outside upon hearing a jeep stop with a squeak of brakes. Out stepped “Monty” (General Montgomery). He glanced towards our window and raised his hand in salute. He looked so cheerful and friendly— such a busy person and yet he found time to acknowledge us with a wave. He wore a long grey pullover and his famous beret— nothing to signify the importance of his position. Shortly afterwards, General Eisenhower stepped out of his car— followed by his little dog! Next came Air Marshall Tedder— he was so tall and stately— immaculate in his blue Air Force uniform. We became quite used to seeing these important leaders and on one occasion, Winston Churchill passed on his way to the control room. With all these comings and goings we realised that the invasion was very close indeed.31

Vera Laughton Matthews reported:

Rear-Admiral Creasy, Admiral Ramsay’s Chief of Staff, told me how he found the Wrens ‘too thick on the ground’ as he described it—so he went round asking, ‘Watch on or Watch off?’ He was frequently met by ‘Watch off, Sir, but please may I stay?’ But he was adamant and said, ‘No, off you go’.32

CARTWRIGHT: It was a hectic life but pretty soon we became accustomed to sleeping in snatches. To compensate, however, the weather was glorious and in our free time, we were taken by liberty boats (marine lorries) to spend a couple of hours on Hayling Island and to enjoy the sands and sea. The only occupants of the Island were members of the forces, as the civilian population had been evacuated. On occasions, also, we managed to get a lift into Portsmouth and visited the cinema. When jeeps passed us on the roads we could always rely on a lift by the friendly American allies, but all the same it was better to travel in numbers!33

BOOTHROYD: We made good use of our free time, the grounds were lovely in the springtime and there was a lake and an old boat, but we decided not to try it! In spite of all that had been said earlier, we were finally allowed out of the grounds and liberty boats went into Portsmouth. One night we went to Southsea Pier to hear Joe Loss and his orchestra. Shortly after this the Pier closed and was used for landing wounded from France to hospitals nearby.

We, Laura and I, favoured Cosham and went to cafes sometimes for Welsh rarebit or just tea and cake and had a general look around the area. Sometimes we went sunbathing to Southsea or to Hayling Island. Generally we stayed around Southwick Village, where we played tennis, sketched or just went for a walk. One day Laura and I met an American airman who turned out to be the pilot of General Eisenhower’s personal plane. He wanted to take us up for a spin, but we daren’t go... I wish we had now!34

I went once to Portsmouth for a haircut and once to see a boyfriend on his way through—he was in a destroyer. I once went out in the Solent in a DUKW. With a friend, I hitched a lift to a village a few miles away where an uncle lived. He and my aunt greeted us without surprise and provided a good tea. He wrote to my mother saying I’d looked well and happy, but he knew better than to ask where I had sprung from or what I was doing. Southwick village provided a shop or two, but there was little to buy. A small ration of sweets and cosmetics were sold in the establishment. We sometimes went into Fareham or Cosham as one or two of the Naval Officers came from those parts and had relations living there. There were no dances, but the odd film show.35

BLANDFORD: We had many happy times at social gatherings at the Golden Lion in the village of Southwick, where the front bar, known as the “Blue Room”, had been unofficially adopted as an Officers’ Mess. The locals were wonderful people and always very polite; they went about their daily business as though we weren’t there.36

GORDON: At about this time, for some reason I believe to encourage us, the Wrens in the Secretariat and their Officer in charge, one of the Admiral’s Assistant Secretaries, and our Chief, were taken by road to Selsey, which was a barbed-wire and Restricted Area, where we were received by a Naval Party whose offices and accommodation seemed to be the beach huts and holiday houses on the front, and taken out in DUKWs (amphibious lorries which drove straight off the beach and into the water and then became waterborne and manoeuvrable as craft) out to sea, mercifully calm, to land on some huge pier-like constructions swinging majestically at anchor above us. They were hollow and we stepped on board them and stood in interested groups on the bottom deck with the huge sides and top deck towering over us, whilst the Officer lectured us on their use. We nodded in the dawning knowledge that these were parts of the “Mulberry” whose conception and construction we had been following on paper for the past year!37

SHUTER: One evening I was driven over to Selsey. The sight that greeted us was beautiful and breath-taking. The stretch of coast was opalescent in the evening light and there, shimmering and pearly, an idyllic factory city floated on the surface of the sea. It had the quality of a mirage—too convincing not to be true, and yet, no smoke, no sign of life. From the clearness and precision of line I felt that I must be gazing at an architect’s drawing through a stereoscope, so solid, so simple of line, so impersonal, yet bathed in a golden warmth as if washed in lightly with a brush. An architect’s dream come true.

The Park off Selsey Bill was one of the great assembly anchorages for Mulberry harbour units. The closely anchored phoenix units had a simplicity of line that you would find in a three-dimensional model of factory buildings. The illusion was completed by the tall chimney effect of the towers of the spud pierheads. My factory city was illusionary; but the Mulberry harbour units were hard fact. We drove silently back to Southwick overawed by the boldness of conception and by the hazards of the task that lay before the men of the Mulberry harbours.38

HUGILL: Southwick Park resembled a village, with streets lined with huts, tents and caravans. Everything was sign-posted, busy and orderly, with redcaps directing the traffic. As watchkeepers, we were able to be out in the perfect summer weather. We rolled our sleeves up and our stockings down and sunbathed on the roof. Letters from home took three or four days. Our families had no idea where we were—and knew better than to ask. And of course we had no access to a telephone. Leave, other than compassionate, was non-existent, and we worked a seven-day week. This was hard enough for us; the strain the senior officers were under showed on their faces, but rarely in their tempers.39

SHUTER: Tension grew during these weeks and nerves became a little frayed, although we drank in the beauty of the Spring through the open doors of our huts… The month of May produced endless days of the most perfect invasion weather—blazing blue skies and zephyr-like breezes. It was impossible not to dwell occasionally on the splendid start the operation would have had if the original target date had been kept.

After the winter in London it was pure enchantment to gaze at the fat buds of the trees blazing like jewels in the sun, or to stand in a sea of cowslips and take in deep breaths of their warm, musky scent. The smells and scents of that Spring are in my nostrils now. The park itself was quite perfect. It had a lake, made complete by a little boat with a lugsail; a glorious open view of the downs with the feeling of the sea just beyond; there were fields of corn, meadows of pasture and, everywhere you turned, the most splendid trees each eagerly spreading out its leaves to the warmth. What more could anyone ask? It was life-giving after a day in a Nissen struggling with telephones and signals, to stroll round the stilly quiet lake in the evening. In London the staff had scattered at night to its own homes. But here we lived and worked together […] I was with the grandest staff it is possible to imagine and they proved delightful company.

The most popular walk was once round the lake and I had many pleasant walks with my quickly expanding circle of chums. Yes, they were nice people. But on one occasion I was almost suffocated by suppressed laughter. I was doing the round of the lake with a young and earnest naval officer. He was delighted with the country like the rest of us. Chatting away to me he presently said, “It is wonderful really what you can see by just walking round this lake. Why I’ve seen wrens, tits and other signs of the wild life that abounds…” Being a Wren I read the wrong meaning into this perfectly innocent remark, and I started to gurgle with laughter. But, on seeing that my companion had not realised the ambiguity of his remark and that he was now looking at me in some surprise, I turned the laugh, rather lamely, into a cough—and left it at that. He was, after all, very young.40

BLANDFORD: In early Spring 1944 large numbers of vehicles and men were coming into the area. One of my friends told me of the day she had seen soldiers in full kit scaling the chalk pit (later, I realised why). Soon, tanks were parked along the roads, half-hidden in the hedgerows; it seemed as if every space in the countryside was filled with soldiers, tanks and equipment.41

BOOTHROYD: During those weeks coming up to the actual D-Day landings many important faces came to the “War Room”, the nerve centre of the invasion plans: the King, George VI, and Winston Churchill came often, and there were regular meetings between General Eisenhower, General Montgomery and Admiral Ramsay. Secrecy was of the essence and it still amazes me now as I think back of the tremendous responsibility we were given, but, at the time, life seemed normal and we took everything in our stride.42

Fig. 2.3. Admiral Ramsay with General Eisenhower at Southwick House, June 1944. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

Wren J.H. Prior, 41801

Naval Party 1645

c/o G.P.O.

Monday 29th May 1944

Dear Mother and Paddy,

Well, my birthday has truly come and gone, and all things considered I had a really good time. In the afternoon after I wrote to you, Betty and I went into a town some 20 miles away and had a really delicious tea and then went to a cinema to see “My Favourite Wife” with Cary Grant, Irene Dunne and Randolph Scott and “The Shipbuilders”. 43 It was a very good programme and we thoroughly enjoyed it. The weather was marvellous and we walked part of the way back. When we arrived back in the cabin, they all insisted on retiring to the local for to drink my health which we did in Shandy.44 It’s quite a pleasant little place inside with cool flagstoned floors and old prints on the walls and roses climbing outside. The roses here are out—are they at home yet?

The cake was simply wonderful! Everyone loved it and we cut it crosswise so that everyone in the office had a piece and I still had half the cake left. On the 25th we were late duty and we didn’t finish until 3-30 a.m. and I’m glad to say the cake came in very handy then as we began to get peckish.

Sorry, must stop for a while now as work had appeared.

Am continuing this in the lunch hour, sitting on a lovely daisy-covered lawn, walled in by the rhododendron bushes.

Life here never had a dull moment and a couple of days ago we were informed at lunchtime that we were to move our living quarters the same evening. This we did and now live some half-hour’s drive from the office to which we travel in an Army lorry. But oh, I’d love you to see where we live, you’d love it! It’s a lovely old pile (I can’t tell you the name, of course) and is built on the lines of a small castle with turrets and archways and wide panelled halls and oh such lovely old sweeping staircases. Of course, I haven’t had time to explore it yet, but it stands in beautiful grounds and when I get my next half day I’ll take a look around it.45

Yesterday and to-day the weather is just the way I like it—very, very hot!

The blossom here this year is lovely. Mauve wisteria and red and white may and chestnut candles all bloom in profusion.

No more news at the moment, so will sign off.

With heaps of love from

Joan xxxx

SHUTER: As they days passed some people found themselves less busy than they had been for many months. Things were beginning to pass out of our hands, out of our control. My own department seemed as busy as ever. We were watching, urging and coaxing the last stragglers on their way round the coast to join their assault forces now assembled and amassed in the South of England. We were also setting up a system whereby we hoped to be able to keep track of the 4,266 landing ships, craft and barges of the allied invasion fleet. They would soon be on the move now. Once unleashed, they would be set in perpetual motion. […] It was a frightening thought.46

HUGILL: As D-Day approached, the pressure of work eased. Some members of staff moved on to take up their forward positions, and the weather was wonderful. The typists completed the typing of Operation Overlord, over 1,000 pages of printed foolscap, and on Whit Sunday, many of us found time to go to Church in Southwick Village. At Admiral Ramsay’s suggestion, two cricket matches between the chaps and girls were organised on a nearby, grassy field, with only the square hastily mown. Admiral Ramsay and the Senior Mess took on the Wren officers and beat them by four wickets. Ramsay himself made sixteen runs but noted in his diary that he was “very stiff.” One of the girls was a lethal underarm bowler’.47 [This was a Wren Officer called Mary Adams, whose wicked delivery broke the nose of a hapless officer-batsman]. ‘Bobby,’ Howes says: ‘it reminded Rear-Admiral Creasy of the Armada before which Drake played bowls on Plymouth Hoe.48

SHUTER: It did seem as if we were going in battle in traditional English style. Not quite bowls on Plymouth Hoe, nor the playing fields of Eton, but a blend of the two very suitable for a combined operation.49

HUGILL: On 30 May, Admiral Ramsay found time to speak to about sixty Wrens of the Secretariat, to thank them for their hard and good work. This is something that those who were present have never forgotten. The Admiral’s attitude to his junior staff was always impeccable, and, with hindsight, I’m sure that his friendliness and good manners were copied by all our seniors. We were a truly happy ship.50

BLANDFORD: By the first day of June, men were sitting in convoys of parked vehicles. Some sat in groups on the grass playing cards. Others were writing letters, presumably to their loved ones. They all seemed in very good spirits and would wave as we drove past.51

HOWES: In early June all personnel were called to a meeting to be told that Operation Overlord was about to begin. They were reminded of the need for strict secrecy and security and all leave was cancelled.52

SHUTER: It was about this time that we were impounded—cut off from the world! Until this moment I had never been able to realise that Overlord was really going to happen. This cutting-off from the world seemed in some way to set a seal on it. Overlord was going to happen as surely as the sun rises or the moon sets. Yes, Overlord was inevitable. The planning had become fact. Endless calculations on paper had been converted into men and material. It was indeed a solemn thought. But everyone was outwardly cheerful and spirits were high. We felt that we had given of our best and we awaited events with confidence.

It is hard to appreciate the power that lies in your pen when you work out invasions on paper. The work becomes part of your daily life—just another job to get done to the very best of your ability. Then suddenly it is no longer on paper but has become a vast armada of ships, material and of trained men.

The thought suddenly chilled my spine; it clutched at my sickened stomach. Who was I to have had a part, even a tiny part, in this great responsibility? Oh God! Please may be we not have overlooked one vital link, one small detail.

But at the end of the month the weather broke. Cold winds lashed at us and the sky became overcast and gloomy.53

BLANDFORD: The weather at the beginning of June was very stormy. Dark skies, high winds and heavy rain—it was more like November. During this time I was not allowed to go home: every position on the switchboard had to be constantly manned, with internal calls heavily curtailed due to Overlord planning.54

GORDON: Tension mounted as the days went by. Since the beginning of June we watched the arrival at Southwick House of all the Chiefs of Staff in consultation with Admiral Ramsay and though we did not know the actual date, we knew that because of the tide and weather there were actually only a few choices. This had of course been discussed earlier in the plans but now that the weather became a vital factor and began to deteriorate we realised that a great many of the forces assembled in ships and craft as far as the eye could see from the top of Portsdown Hill in the Solent and were also in assembly areas in other ports all along the south coast, must soon sail. Some in fact had already done so and sea-sickness amongst the fighting men—a lot of discussion had gone into which was the best pill available for them to take—was only one of the worrying factors to be taken in account. Besides which, there were terrible problems of towing and of small craft in high seas, and the problems of other vital operations which had to take place in the vanguard of the main assault.55

SHUTER: At 1200 on 1 June 1944, the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief, Expeditionary Force, assumed the operational command of the Neptune fleet and the general control of all movement in the Channel. Excitement rose to fever pitch.

D-Day had been agreed upon for 5 June and a complicated machine swung slowly but relentlessly into motion. Stores, vehicles and troops began to move to forward areas and a steady even stream flowed down to the hards. Loading had begun. The machine must be kept turning over evenly, the flow must be maintained, steady and continuous. One little check would cause endless repercussions, alterations to time-tables and widespread re-organisation. This gigantic yet delicately balanced monster of organisation gained in momentum. From the Nore to the Bristol Channel loading was in full swing. Ships, worthy old-timers that were to be sunk on the far shore to form breakwaters had already sailed from the north of Scotland—and they began the drama of D-Day.56

BOOTHROYD: During the days up to the 6 June the parkland and lanes nearby were filled with troops, tanks, jeeps and other equipment. A huge NAAFI57 canteen was set up to serve the troops. While we were off duty, we stood and waved to many of the men as they moved off to the beaches and to embarkation.58

By this time the operations room on the ground floor in Southwick House had become the nerve centre. Beryl K. Blows remembers:

The Liaison Officers (RAF, US, ARMY etc), sat with their backs to the wall, facing the wall plot, 59 at small individual tables, squeezed together each with a telephone on his desk.

The large table plot was in front of the big windows—daylight was taken advantage of but the windows were of course blacked out at dusk. The room became very hot when it was crowded. Officers never removed their jackets and the majority smoked. Ventilation was minimal’. The regular staff comprised ‘one Wren Plotting Officer, two Wren Plotters, both probably Leading Hands, one Junior Naval Staff Officer, probably a full Lieutenant, one Duty Commander RN, and three or four Liaison Officers’ who were ‘not present all the time. […] There was a small standing switchboard in the room, awkwardly placed in front of the door, operated by a Wren Telephonist. Many others came and went all the time: Wren Cypher Officers, Wren Coders. People looked in constantly and the room got very crowded. Attempts were made to limit numbers. Anyone not actually on duty or with business there was discouraged. But there were many visitors. […] There was a Senior Officers’ Mess adjacent to the Ops Room, so Senior Officers (Admirals, Generals) often looked in to check en route to eat, or after a meeting or before going to bed.

Fig. 2.4. ‘Headquarters Room, Southwick Park, Portsmouth, June 1944’, watercolour painting, by Barnett Freedman, Art.IWM ART LD 4638, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/10043

Furniture was very ordinary, workaday type officer tables and chairs. Telephone wires trailed everywhere, coming out of the floor. Signals were deciphered or decoded elsewhere, brought in and added to the appropriate clipboard.

The plots, wall and table, were “picture” plots as opposed to “operations plots”. In other words, the plots at Southwick were a record of information obtained elsewhere. This came through by telephone from other operations rooms along the coasts, which in turn had received the radar reports from the chain of radar stations taking readings from their screens. Years of practice had perfected the system. We used chinagraph pencils on Perspex. Our telephone technique and speed of marking were impressive. Ordinarily, the plots would be updated at regular, precise intervals, perhaps half-hourly, but during an operation or flap this could be increased to every ten minutes. Information could be marked in grid co-ordinates or in cross-bearings. Additional data from other sources was constantly being added and slow-moving convoys would be marked up hourly. Every call was logged in previously ruled-up notebooks. Each convoy or ship on its own had a distinguishing mark, originating from the port of departure or initial radar siting. Thus, the early convoys of blockships sailing slowly from Scotland retained their mark all the voyage, progress having been plotted throughout. ETD and ETA times would have been on a wall board. These marks were very informative, containing letters and serial numbers. “A” for Allied, “E” for Enemy, “U” for Unknown or Unidentified, followed by a number, followed by the direction it was heading. The composition of the convoy had been known at the time of sailing, how many merchant ships, escorts, air cover etc. All this information was logged and available in case of query or attack and the plotters could answer questions readily. Changes in the composition of convoys, breakdowns, came through by signal.

Anything unusual could be spotted by the plotters and senior staff alerted. Updating the plot took precedence over everything and everybody, thus: “Excuse me, Sir, the 1430 positions are coming through”. One plotter logged the message, repeating back the information aloud. The second girl marked the plot. The Plotting Officer transferred anything needing to be shown on the wall plot. She oversaw all the data gathering in the room and took her turn doing other peoples’ jobs when necessary, answering unmanned phones etc.60

Fig. 2.5. D-Day Wall Map, Operations Room, Southwick House, NMRN 2017/106/379, courtesy of National Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth. ©National Museum of the Royal Navy.

Wren J.H. Prior, 41801

Naval Party 1645

c/o G.P.O.

Friday 2nd June 1944

Dear Mother, Paddy and all at home,

Here we are again, all merry and bright!

Since our move which I have previously told you about, life has been going along very smoothly if busily.

We have been enjoying what might be called a heatwave and expect you have too, although it seems to have broken a little now. On Tuesday I had an afternoon off and the weather was wonderful. I went back to our Quarters and changed into my shorts and ankle socks and lay on the lawn and sunbathed for a while. Then I went for a walk into a nearby village61 across the fields and returned in time for supper which we took out on the lawn and had picnic fashion. It’s the queerest picnic I’ve ever had—we had kippers and lots of bread-and-butter and peach jam and tea! After supper we played tennis and then early to bed for a change.

I thoroughly enjoy the drive to and from the office each day as we go through some beautiful country past endless thatched cottages with the roses in bloom round the doors and old brick walls covered with wisteria and drooping laburnum blossoms. How are the roses at home? Are the new ones we bought out yet? And all the packets of seeds Mum and I bought in Woolworth’s?

I’m awfully sorry to hear that Mr. Smith is now suffering pain and although it doesn’t seem right to say it, hope he doesn’t hang on much longer in what must be agony.62

I have received a letter from Charlie and also one from Bess and one from Grace and will answer them all as soon as possible.

Yesterday, I had the surprising pleasure of receiving the letter from Bill which you sent on.63 He is now in New Britain in the South-west Pacific where it rains all day and all night he tells me. He also enclosed some snaps of himself and of Brisbane. His mother has now apparently moved to Southampton but he doesn’t give me her address, so I can’t write to her.

I think that’s the limit of my news now except to say that I am keeping very well and hope you are all O.K.

Cheerio for now, with lots of love

From

Joan xxxx

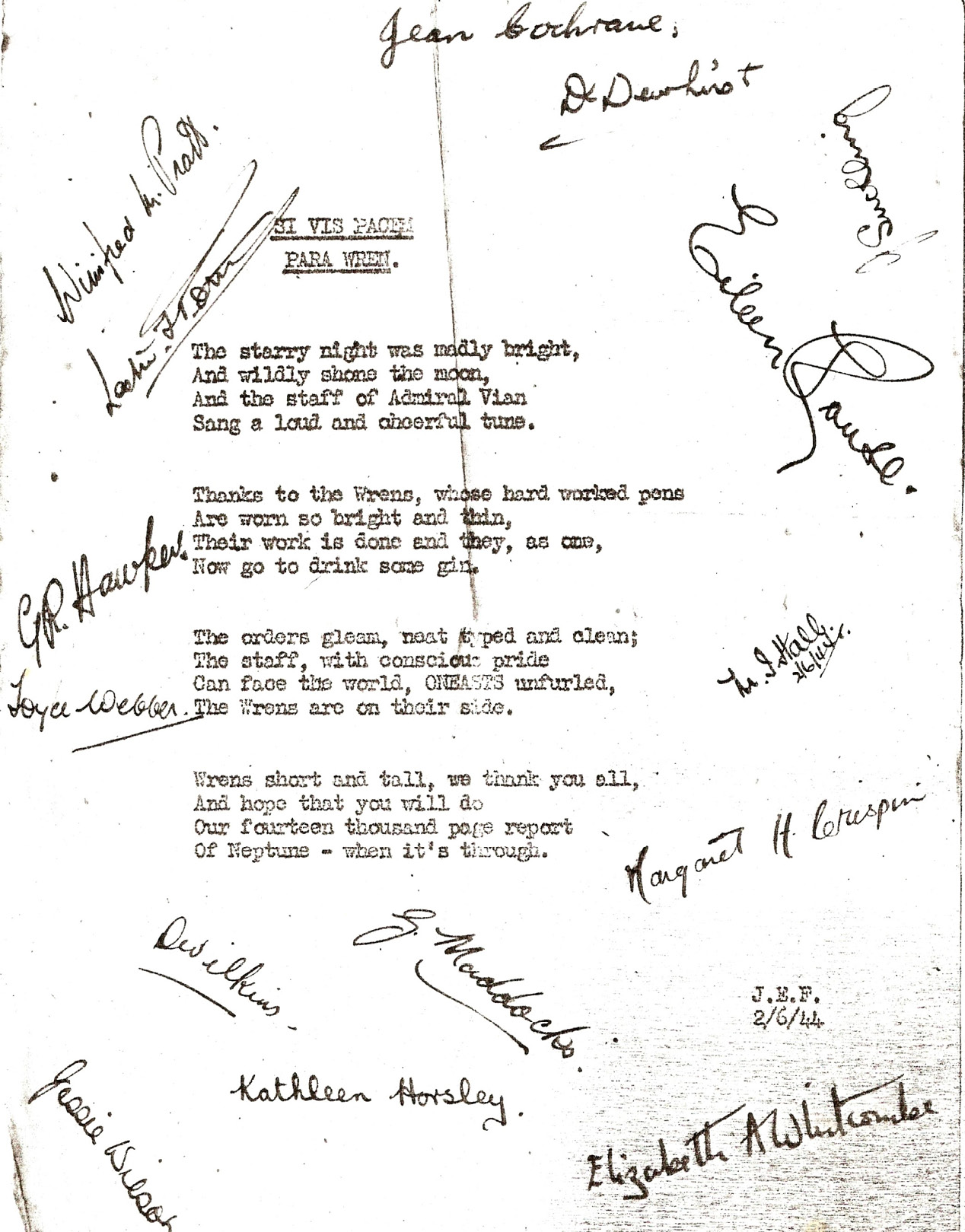

Fig. 2.6. ‘Si Vis Pacem Para Wren’, poem by J. E. F., 2 June 1944, signed by Wrens of ANCXF at Southwick Park. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

SHUTER: On 2 June the weather forecast for D-Day was not favourable, low cloud which would be bad for the air, both airborne troops and the aircraft supporting the landings, seemed likely.

Early in the morning and again on the evening of 3 June the Supreme Allied Commander, the Allied Commanders-in-Chief, their right-hand men and the meteorological experts met together in our Headquarters. The weather forecast for D-Day, the 5 June, was still gloomy. Thus, in the event, despite man’s science and knowledge, despite his planning and organisation, the weather held the whip-hand.

If humanly possible a postponement would be avoided. There is no knowing what will happen if a great machine composed of human elements is suddenly checked. Above all, it is bad for the morale of troops, keyed to fever pitch, to have to suffer a postponement. The stoutest hearts are bound to falter and spirits to droop if men are cooped up for hours in a landing craft lying at anchor.

At 0415 hours on 4 June the men, on whom the decision rested, met again. In view of the still unfavourable weather forecast for 5 June, but on the promise of an improvement for 6 June, it was reluctantly agreed to postpone the operation for twenty-four hours. Thus the dreaded brake was applied to the mighty movement machine.64

GORDON: We stayed up most of the night of 4 June in the hut next to the Meteorological Hut listening, watching and waiting white they and the Chiefs of Staff came to the decision to postpone the Operation. With the knowledge that we had of what this would mean, we spent a worrying day thinking of that massive, waiting Armada, each craft with its own special difficulties brought about by the delay.65

BLANDFORD: Forty-eight hours before the landings, there was a total silence on the switchboards, except for the C-in-C’s personal line. Everyone was at their positions, just waiting and waiting. With the terrible weather continuing, the atmosphere in UGHQ was very tense.66

THOMAS: I vividly remember the day before the start of the invasion. The weather was dreadful, and I remember a meeting being called with a meteorologist, I think his name was Stagg.67 He said there would be a gap in the weather and if we didn’t seize the opportunity, we would have to wait another three weeks.68

SHUTER: Conditions of tide were such that the operation could only be carried out over a period of a few days. If the weather remained unsuitable throughout this time then the operation would have to be postponed until the middle of June. Imagine the complications that would arise in such an event! The seals on operational orders had been broken, men had been briefed. Thus, the whole invasion force would have to remain impounded throughout this period of waiting. Hundreds of thousands of men living on top of each other under increasing tension. Think of the effect on morale. The administrative headache would be intolerable. Surely the good God wouldn’t send this to try us?

On the evening of 4 June our great leaders met again. The weather promised for 6 June still showed some improvement. Naturally the Army wanted to go. But could the Navy guarantee to take it there, and the Air give its planned support under the prevailing weather conditions? These were the factors upon which the decision rested. Accepting the promise of improvement given by the meteorologists the Navy and the Air agreed the undertaking. The final responsibility rested with General Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander. A great man if ever there was one. He had had many desperate decisions to make during the war and this one must have been the most vital of them all. He decided to launch the operation.

Thus a courageous decision was taken, a decision on which the whole course of the war and the lives of thousands of men depended. Thus it was that D-Day became irrevocably 6 June 1944.

Indecision, the most exhausting of all mental states, was at an end. The tension eased. We were committed! Operation Overlord was “on”, and now no power on this earth could stop it. We all felt a lot better.

But 5 June, or D minus one, is a day I would not live through again for all the gold in the Bank of England. As the meteorologists had predicted, the weather was diabolical. The wind gathered in strength and the sea became rough. The sky was heavy with clouds. The day was chill and bleak.

We knew that no major landing craft, let alone tiddlers, would be sailed coastwise and empty on such a day. And yet, that evening, not only major craft but minor craft—forty-foot LCM and LBV (converted Thames barges)—were to set out to cross a wide expanse of angry Channel and they were very heavily laden—in some cases cruelly overloaded.

“Oh God,” we thought, “Are all our months of careful planning, are all the fruits of man’s ingenuity to be proved impotent against the hand of Nature?”

Our hearts bled for the gallant men setting out on this perilous voyage—and there was nothing we could do for them, nothing. It was out of our hands, events were moving forward remorselessly.

Our Commander-in-Chief was an inspiration throughout that day. His self-control was absolute. His courage was in his calmness.69

THOMAS: On the night of 5 June 1944, we didn’t go to bed because we knew the invasion would be happening in the early hours of the next morning. We went out to watch the gliders being towed over to the continent. I vividly remember the sound of the aircraft. We all knew where they were going, but we didn’t know what would happen when they got there. It was a very emotional and worrying time.70

CARTWRIGHT: On 5 June we were told by the Commander that the invasion boats had set sail for Europe. On that evening I was on night duty and knew that it was the most memorable occasion of my life. At midnight, the Commander told us that in twenty minutes our first airborne troops would land in Normandy.71

SHUTER: The night wore on. We heard the roar of heavy bombers passing overhead. We looked at each other. The softening-up bombardment of the assault area! The Air Force had not been grounded by the weather and the fleet had sailed! The weather experts had been right—the weather was improving. Oh, joy!

Later we heard dull distant thuds and crumps. We dashed outside, and from the ramparts we could see the flashes of exploding bombs as those bombers let go their load. Ah, this was the invasion all right! Those flashes came from the assault area. Nothing prosaic about those flashes: there was heat, there fire.72

HOWES: I was Duty Petty Officer on the night of 5 June. It was remarkably quiet and after the previous cancellation because of adverse weather, the operation was under way. For once the operators had time to chat amongst themselves, wondering if their boyfriends had sailed off to France and how long it would be before they met again. Would we be going to France too? Would we get any leave beforehand? Would the invasion succeed? How bad would the casualties be? All of these thoughts were bandied about, helping to pass the time—it was a very long night.

Because of the use of scramblers we could only anticipate what was happening, but a call from General Omar Bradley at about 0200 hours gave us cause to hope that everything was going to plan. The RAF had bombed the coastal batteries between Le Havre and Cherbourg and gliders had landed Airborne Divisions behind the coastline of Normandy.73

SHUTER: On returning to Southwick House I stole into the operations room half-expecting to hear that the assault forces had been scattered, perhaps by the weather, perhaps by the enemy. How could such a great Armada remain unmolested and undetected? But the room was not tense with battle. The watch was tranquilly drinking its cocoa! Reassured, I forced myself to look at the great wall plot and there, inside the lee of the Contentin peninsular, were the five lengthening lines representing the assault forces—intact, and as yet unobserved! Only two hours to go and they would be there. Oh, thank you God!

To me it seemed a miracle. Relief spread through my body in a warm glow and I climbed into bed feeling light as air.74

CARTWRIGHT: The office seemed chilled with expectance and no-one could speak, for I am sure that waiting for news is almost as bad as taking part! One could imagine all the dangers and what a risk was being undertaken and the lives of our brave invaders being so much at risk. I thought of my folks at home, soundly asleep, little knowing of the momentous occasion taking place and I offered silent prayers on behalf of all those taking part. Our first official news came through in the early hours from the Augusta and the Scylla75— all was being carried our according to plan.76

Fanny Hugill ‘was on watch in the Operations Room for the night of 5/6 June. We were all subdued. Admiral Creasy, the Chief of Staff, kept watch and Admiral Ramsay went to bed, to be called at 5am if all was well. So it was, but the wind howled and the shutters rattled all night long’.77

BLANDFORD: Early in the morning of 6 June, our waiting was ended. Officers of the three services were standing around in groups and the strain showed on their faces. I had been on duty for forty-eight hours, with just short naps, and felt very tired. Suddenly, one of my young Wrens shouted, “Ma’am, Ma’am! Something is coming through!” The red light on the panel glowed brightly […] I rushed to the position and listened. There it was—the long-awaited code word which meant so much. They were through at last. A cheer went up and many young girls shed a tear. Maybe a boyfriend was over there—it was a very emotional moment.78

BLOWS: On the night in question, most of the top brass went to bed—late. The Duty Commander and Captain Dickie Courage would of course have been present, and the Met people would have been coming in and out from their own office.79

HOWES: By the end of the Middle Watch we received news that everything was going well and at 0630 hours the first seaborne troops were landing on the beaches.80

BLOWS: Breakfast next morning was cheerful—so far so good, but we wouldn’t have talked shop. First news reports of the Allied landings were coming through on the wireless.81

HUGILL: At 8am I went off watch and in to breakfast, to hear Alvar Liddell announce on the wireless that the invasion had begun. I should have gone to bed, and indeed I lay down, but I couldn’t sleep and went for a walk. Later that day King George VI broadcast to the nation—a very solemn king, urging us all to pray for peace.82

HOWES: I finally went off duty at 0800 hours, and then at about 0930 came the BBC announcement of the landings. The Mess echoed to an almighty cheer—after all the planning the beginning of the end was in sight, our lads were in France and we had been part of it! […] I walked down the tree-lined drive to Southwick House where the red squirrels were playing, very tired but very happy, and climbed thankfully into my bed in the attic of South Lodge.83

GORDON: On the morning of 6 June the Wren stewards who had stayed on as part of HMS Dryad and did our “messing” for us, told us at breakfast, did we know that there had been a landing by the Allies in Normandy? It was of course a great moment and there was an air of relief and congratulation amongst all at Southwick Park.84

SHUTER: It was good that morning—the morning of D-Day—to hear the wireless blaring forth to the world the news of the successful opening of the so-called Second Front. We tried to imagine what it meant to the average Englishman who had not known when it was coming—and what the reactions of the French people would be. But above all: what were the Germans feeling? […]

The assault did indeed contain an element of surprise we had hardly dared to hope for in the Normandy landings. This was in some measure due to the unfavourable weather, but even more to the success of the cover and deception plan. The Germans were certain, as we had intended they should be, that a large force was approaching the Channel ports to the north-east, so realistic were the devices employed in their deception…

Thus the invasion forces met with no enemy interference on their way to the assault area. And, incidentally, despite the ugly weather, only a very small percentage of craft and barges were lost in the crossing. Bless them, the brave little things. I was so proud of them, as proud as a mother would be […] Yes, phase one, the assault, was undoubtedly an unqualified success.

The staff looked as if it had been re-born that morning. We had been so immersed in the pre-invasion atmosphere, which had grown round us insidiously, until we had been held prisoner almost without knowing it. But, with the successful landing of the assault troops, we realised that round one had been won by us. The shackles that had held us slipped to the ground, we felt almost free again; free to breathe, to sleep, to enjoy the fresh air. The strain of the last few months had been intense. We realised now just how great that strain had been.85

CARTWRIGHT: The night following the invasion I was not on duty, but during the evening I watched the hundreds of gliders being towed across to France and felt very proud indeed to have helped, even in such an insignificant way, towards the culmination of such a great operation.

Within a matter of days our teleprinters were all connected to the ones in Normandy which were manned by the Marines and in between messages we were able to glean a little of what life was like on the other side of the Channel.86

BLANDFORD: I can still remember the thrill and relief of hearing the voices of our lads from that far Normandy shore.87

BLOWS: I recall quite vividly the sensations of pride, fear, rejoicing and loneliness we WRNS Officers experienced. […] Proud of the possession of knowledge, as yet unknown to the world, that after four years of captivity, Europe was about to be freed, proud of knowing in work and play the gallant men who were to carry out this tremendous task; fearful of what might befall our many naval friends, whom for a year we had helped plan and rehearse the Invasion, rejoicing that this great day for which so many had patiently worked and waited was actually upon us.

And a sense of loneliness—for the docks which the night before we had seen filled to capacity with ships of all shapes and sizes, in their bareness were now hardly recognisable, and the desks in the shore establishment, so recently filled by many officers of the Combined Services often for 18 hours of the day, stood empty. Corridors, once filled with thousands of copies of Operation Neptune orders typed by Wrens, had been cleared, the last amendment made, and the last order given to our Landing Craft.88

SHUTER: By D plus one the beaches had been secured and soon supplies were pouring in through the beachheads. On one beach the Americans, who had been unfortunate enough to encounter a German division on night exercises on D-Day, had had a tussle. But now all were well established, and in a few days the Mulberry harbours were beginning to take shape. The old-timers had been sunk in position. Outside them, the walls of the great harbours made up of the Phoenix units, which had been towed across and sunk exactly in the correct positions, were nearly complete. Things were going well.89

HUGILL: Within about three days, a trickle of staff who had crossed with the first waves of ships returned, bearing as trophies gifts for the Mess of Camembert cheese and Armagnac spirits. They filed their reports and returned to Normandy.90

BLOWS: Now our job turned from an operational to a domestic role. Telephone messages and letters had to be dispatched to anxious wives, parcels of newspapers and mail sent off by the fastest possible means to our ships at sea. We now had time for chores and letter writing (such things had been neglected for months), but we had little inclination to do either, and would have given much to bring back the ships and crews, and life with its tense though swift tempo.91

A watch was long—eight or ten hours. We ate before and afterwards and minimal refreshments were taken, outside the Ops Room (no cups inside). We worked in three watches (ie every third night on). No special celebration was in order after D-Day. We were all too well aware of the possible deterioration in the weather and the unpredictability of the enemy response. In any case, we were working under great pressure. Sleep could be difficult. Sixty Wren Officers in three bedrooms. Double-decker bunks. We had no expectations of privacy or right to quiet during the day. But we slept!92

SHUTER: Then on 19 June, which was D plus thirteen, a great storm blew up and it raged for three long days.

The whole assault area, being in the lee of the Cotentin peninsular, was well sheltered from the south-west—the quarter from which winds, or even a summer gale, can be expected at this time of year. But the gale of 19 June blew up from the north-east, and it blew with a strength which could not have been anticipated in June. It was a freak.

All the beaches were at the mercy of wind and sea. The British area was slightly more fortunate than the American. But throughout the length of the assault area ships, men and material were at the mercy of that cruel and angry gale driving in upon them. They were defenceless. Ships were driven ashore; and craft, vehicles and wreckage were flung up on the beaches well above high water mark. Great was the loss sustained. The Mulberry harbours which had been taking form with a success we had not dared to hope for, were damaged—the American one so badly that it was abandoned. [But by now] the armies were well established some miles inland, and the artificial harbours were sufficiently progressed to provide a great deal of shelter, and, in the case of the British one, to survive.

But even so, Fate had dealt a cruel enough blow. After what seemed an eternity the storm blew itself out and those on the far shore were able to assess the damage. Immediately came the cry for more ferry craft—those used in unloading from ship to shore. The stream of supplies to the Armies must be maintained at all costs!

Commander-in-Chief Portsmouth’s splendid landing craft team did wonders. The few barges and minor craft still stranded on this side of the Channel were quickly collected together and delivered to the far shore. In addition LCT93 of the Shuttle Service were held over there and used for ferrying duties.94

GORDON: After D-Day the work in the Registry somewhat abated and with the easing of the year-long tension we found it difficult to keep awake! We often fell asleep at our desks and on the grass outside the Nissen hut, but we were able, through the papers still coming in, to watch the progress of the landings closely. But it meant more free time and we were able to cycle in the surrounding countryside, sail on the lake, picnic on Hayling Island, and go to the cinema in Portsmouth (walking back from Cosham).95

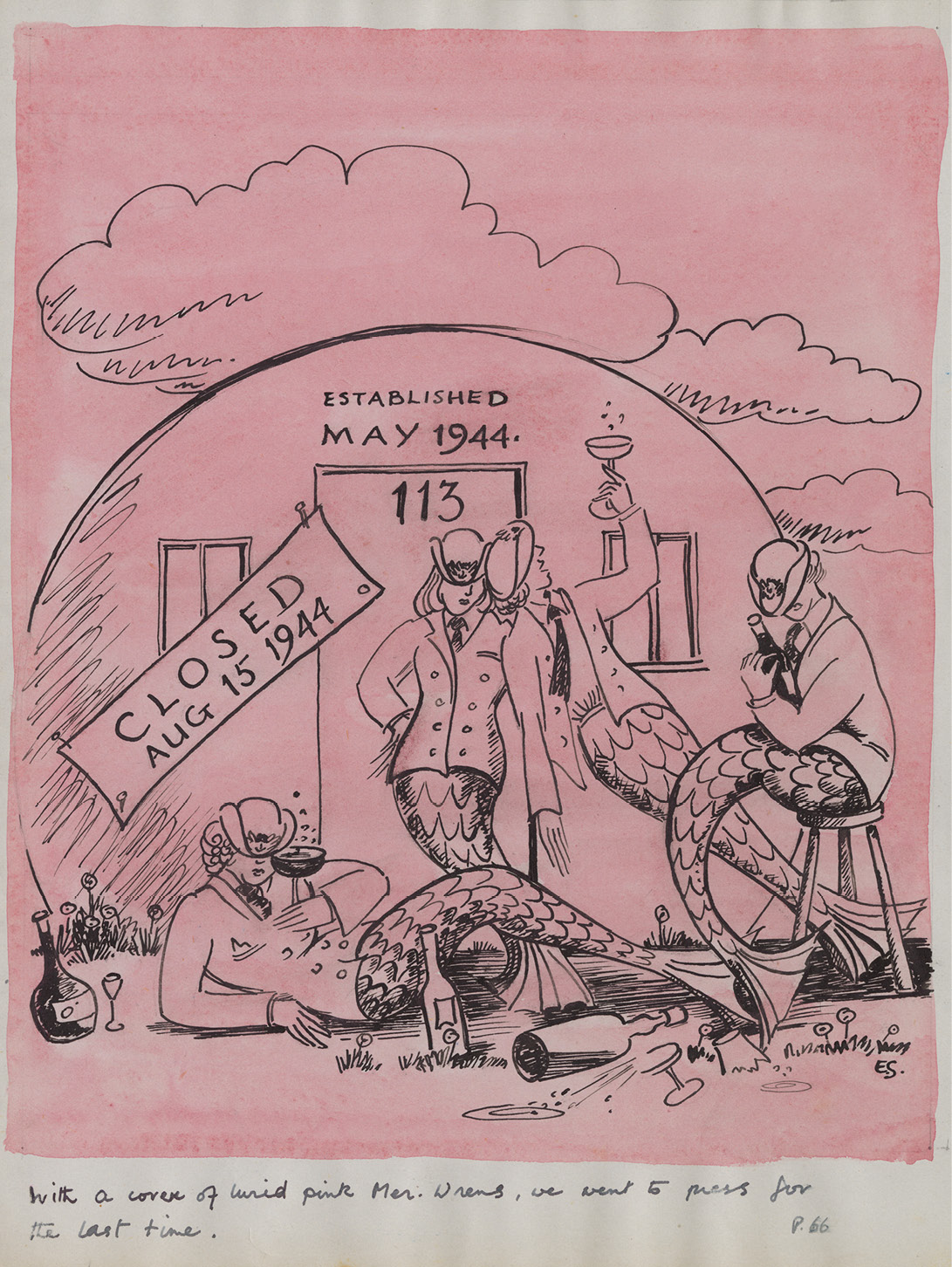

SHUTER: At the beginning of July, Hut 113 had settled into a steady routine, and at last we were able to arrange that everyone got away for an afternoon each week. The fact that the team was having no break from the monotonous and intensive work had been very heavy on my conscience.

So it was that early in that month, a chum and I went down to Portsmouth. We rode across the harbour in the ferry and saw our craft at close quarters for the first time! We snooped around the harbour and went to Gosport, Gilkicker and Lee-on-Solent. Going back on the ferry we fell in with a red-bearded Commander. He was charming, and asked us to dinner on board his ship. It was the first social outing for months and it brought home to us the fact that we were suffering from a total immersion in work. Our host dined and wined us extremely well and we purred in our comfortable chairs feeling as sleek as a couple of kittens […] We finally left the dockyard in a mellow state having drunk of the best during the evening—gin, a fine dry sherry, hock and port. Thank you, sir, that evening did us a power of good.

That afternoon spent in the harbour brought home to me just how much we were missing as we sat glued to our desks in our hut. […] I was now determined that my team should “get to sea”. But in the Navy there is nothing more difficult—if you are a Wren! Then it was that the Army came to our rescue. Each morning an Army launch went around the anchorages in the Solent and Spithead. They said they would be delighted to take a Wren or two along with them. The team in Hut 113 went first, and later Wrens went from other departments.

It was pure enchantment to spend the morning taking in lungfulls of good sea air, to feel the spray, to taste salt on the lips and to brace yourself against the wind. This was being alive!

The launch wove in and out between the anchored shipping; from battleships to landing craft; liners to coasters. They were all there—the ships we knew so well on paper! MTB roaring out of the harbour in a cloud of spray.96 The simple lines of an LSD into which small craft swim, then the water is pumped out, and they are in a dry dock in which they be repaired or carried to their destination. Liberty ships bearing the names of US Senators with the most amazing pin-up girls painted round the funnels, the curve of the funnel emphasising the rounded form of a beautiful blonde! Train ferries, tugs and tankers. The thrill of a Sunderland flying boat landing on the water. Yes, these trips were quite the nicest thing that happened while we were at Southwick.

Of course, we were not living under ideal conditions at this time. In our dorm there were twelve Wren officers sleeping in double-deckers—bunks one on top of the other—and there was barely room to squeeze between them. But we had many good laughs. Our wit always seemed at its most succinct during air raids. […] While at Southwick we were visited by doodle-bugs.97 For one or two nights they snorted over at regular intervals. One night in particular we heard one murderously near. It seemed to shake the house as it passed over. K and I sat up in our bunks.

“Praise the Lord and keep the engine running,” we murmured, and immediately felt awful cads. Then it disappeared over the tree tops spitting out fire as it went. Of course, the guns all round sounded like hell let loose. A marine sentry got excited and blazed away at it with his rifle. Fortunately for us, he was not a good shot.

Later, when we knew we were going over to France, we used to practise the Can-Can in a state of semi-undress—supposed to indicate French influence—but always with our three-cornered hats cocked well down over one eye. The dance was done to the accompaniment of:

“We’ll do the Can-Can

At Port-en-Bessin!”

and only stopped when, exhausted by laughter and exercise, we threw ourselves down on our bunks.

Fig. 2.7. Illustration of Hut 113 by Elspeth Shuter. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000019, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

The liberation of Paris on 25 August was a great and stirring event. Paris, the heart of France, was free!

That evening, I saw our French Naval Liaison Officer setting off for his solitary evening walk as usual. It seemed too bad that he should be alone on such a night. Paris is Paris, and his heart must have been there. So later we went over to his cabin and asked him to an impromptu party to celebrate the great event. It was a great “shebang” we had in our funny little square ante-room—a room the size of a pocket handkerchief—which was all we possessed as a place to sit in. We toasted the Contre-Amiral, we sang the Marseillaise (badly, I’m afraid), and we danced. Everyone was caught up in the happy and spontaneous atmosphere. The Navy was limbering up!

At the beginning of September […] we said good-bye to Admiral Creasey, to the Navigator and the Hydrographer, both of whom had often made me laugh thus helping me through bad patches, and to many others I was sorry to leave behind. And with a wave of farewell, ANCXF picked up its skirts and crossed daintily over to France. And something of the gaiety of the night of the liberation of Paris seemed to go with us.98

1 Rear-Admiral W. S. Chalmers, Full Cycle: The Biography of Admiral Sir Bertram Home Ramsay (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1959), pp. 209–210.

2 Jean Gordon (Irvine) (Leading Wren), ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’, unpublished personal testimony, D-Day Museum Archive, Portsmouth, H670.1990/5.

3 Elspeth Shuter (2/O Wren), ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’, Documents.13454, Imperial War Museum, London.

4 Mabel Ena ‘Bobby’ Howes (PO Wren), interview, Frank and Joan Shaw Collection, D-Day Museum Archive, Portsmouth.

5 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

6 Chalmers, Full Cycle, p. 210.

7 Gordon, ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’.

8 Hugill, ‘A Wren’s Memories’.

9 Phyllis ‘Ginge’ Thomas (Leading Wren), ‘Ginger Thomas’s D-Day: Working for Cossac’, WW2 People’s War, A2524402, 16 April 2004. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/02/a2524402.shtml

10 Gordon, ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’.

11 Kathleen Cartwright (Wren), ‘My experience of life in the Wrens’ (contributed by Huddersfield Local Studies Library), WW2 People’s War, A2843840, 17 July 2004. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/40/a2843840.shtml

12 The unassuming culprit, Daily Telegraph compiler Leonard Dawe, who was headmaster of the Strand School, was interrogated by MI5, but the case was dismissed as a remarkable coincidence.

13 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’

14 Cartwright, ‘My experience of life in the Wrens’.

15 Grace and Harry Prior. Joan invariably called her father ‘Paddy’ after a family visit to a play at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, called Let Paddy Do It.

16 Elsie Cheney (Wood).

17 Joan’s elder sister Grace Snell (1908–1992) was affectionately known in the family as ‘Geg’ (perhaps because their mother’s name was also Grace).

18 Ronald Smith (1920–1973) was Joan’s fiancé from Barking. Like many sweethearts during wartime, enforced separation and combat risks had put their relationship on hold for the duration of hostilities. A private in the 1/4th battalion Essex Regiment, Ron had arrived in Egypt in October 1941, saw action at El Alamein in 1942 and took part in the invasion of Sicily in 1943. By March 1944, his company was engaged in the Italian Campaign as part of the 4th Indian Infantry Division at the third battle of Monte Cassino (15–23 March), under constant fire for five days and nights on the notorious Hangman’s Hill. Following this action, the 1/4th battalion withdrew to Wadi Villa and remained there until 2 April with some local leave in nearby Venafro and Benevento. The division then moved to the Adriatic front and arrived at Consalvi on 9 April. The battalion remained in the line there or in reserve at Orsogna until the end of May.

19 ‘Sitting on the Fence’ was a regular wartime column by humorous feature-writer Nathaniel Gubbins in the Sunday Express newspaper.

20 Fellow Wren Joanna Day.

21 Bessie Bones (1909–1984) was Joan’s middle sister.

22 Charles Snell (1910–1966) was the husband of Joan’s sister Grace. An electrician by trade, he served with the Royal Engineers in Sierra Leone.

23 Fellow Wren Betty Currie.

24 Portsmouth. Censorship restrictions forbade the naming of places.

25 Engine Room Artificer.

26 The cat!

27 Howes, interview.

28 Patricia Blandford (2/0 Wren), oral history interview recorded April 1991, transcript in the D-Day Museum Archive, Index Key 2001.687/DD 2000.5.2

29 Gordon, ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’.

30 Margaret Boothroyd (Wren), ‘In the Wrens with Laura Ashley’, WW2 People’s War, A2939646, 23 August 2004. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/46/a2939646.shtml

31 Cartwright, ‘My experience of life in the Wrens’.

32 Dame Vera Laughton Matthews, Blue Tapestry (London: Hollis & Carter, 1948), p. 236.

33 Cartwright, ‘My experience of life in the Wrens’.

34 Boothroyd, ‘In the Wrens with Laura Ashley’.

35 Beryl K. Blows (3/O Wren), Unpublished Personal Testimony, D-Day Museum Archive, Portsmouth, AW ID. H679.1990.

36 Blandford, oral history interview.

37 Gordon, ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’.

38 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

39 Hugill, ‘A Wren’s memories’.

40 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

41 Blandford, oral history interview.

42 Boothroyd, ‘In the Wrens with Laura Ashley’.

43 Winchester. This programme was showing at the Theatre Royal which was a full-time cinema.

44 The Golden Lion, Southwick village.

45 Soberton Towers, Droxford, ten miles north of Southwick in the Meon Valley. This 1905 folly, built by Colonel Sir Charles Brome Bashford, was requisitioned in December 1943 as WRNS accommodation to serve HMS Mercury, home of the Royal Navy Signals School at Leydene House, East Meon. See Chris Rickard, HMS Mercury: Swift and Faithful (East Meon History Archive, 2006). https://www.eastmeonhistory.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/History-of-HMS-Mercury.pdf

46 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

47 Hugill, ‘A Wren’s memories’.

48 Howes, interview.

49 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

50 Hugill, ‘A Wren’s memories’.

51 Blandford, oral history interview.

52 Howes, interview.

53 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

54 Blandford, oral history interview.

55 Gordon, ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’.

56 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

57 Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes.

58 Boothroyd, ‘In the Wrens with Laura Ashley’.

59 The wall plotter made of cork board with small block pins to indicate and plot the movements of different groups of craft in their progress across the Channel, was installed in the Operations Room at Southwick House in May 1944. It was manufactured by a subsidiary of Triang Toys, International Model Aircraft, at their works in Wimbledon. The unfortunate workman who came to install it was required to remain at Southwick House until after D-Day, because it was considered too great a security risk to allow him to depart with the knowledge he had gained of the operation during installation.

60 Blows, unpublished personal testimony.

61 Droxford.

62 William George Smith (1872–1945) died at his home, 15 Park Avenue, Barking, on 11 June 1944.

63 William George Howell Porter (1923–1992). Singapore-born pen-pal. Joan and Bill had been classmates at Napier College, Woodford Green, before the war. Bill served in the Royal Australian Air Force. Their correspondence continued throughout the war.

64 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

65 Gordon, ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’.

66 Blandford, oral history interview.

67 Group Captain James Stagg, RAF, SHAEF’s meterologist.

68 Thomas, ‘Ginger Thomas’s D-Day: Working for Cossac’.

69 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

70 Thomas, ‘Ginger Thomas’s D-Day: Working for Cossac’.

71 Cartwright, ‘My experience of life in the Wrens’.

72 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

73 Howes, interview.

74 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

75 USS Augusta and HMS Scylla were the flagships of the Western (US) and Eastern (British) Task Forces of Operation Neptune, under the command, respectively, of Rear-Admiral Alan G. Kirk, USN, and Rear-Admiral Sir Phillip Vian, RN.

76 Cartwright, ‘My experience of life in the Wrens’.

77 Hugill, ‘A Wren’s memories’.

78 Blandford, oral history interview.

79 Blows, unpublished personal testimony.

80 Howes, interview.

81 Blows, unpublished personal testimony.

82 Hugill, ‘A Wren’s memories’.

83 Howes, interview.

84 Gordon, ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’.

85 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

86 Cartwright, ‘My experience of life in the Wrens’.

87 Blandford, oral history interview.

88 Blows, unpublished personal testimony.

89 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

90 Hugill, ‘A Wren’s memories’.

91 Blows, unpublished personal testimony.

92 Ibid.

93 Landing Craft, Tank

94 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.

95 Gordon, ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’.

96 Motor Torpedo Boat.

97 Hitler’s V1 flying bombs, soon known as ‘doodlebugs’ or ‘buzz-bombs’, began their aerial attacks of targets in London and the South East of England on 13 June 1944 and continued to be a menace until their launch sites in France and the Netherlands were overrun by the advancing allied armies.

98 Shuter, ‘Private papers of Miss E. Shuter’.