3. Liberation

(Granville, September 1944)

©2024 Justin Smith, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0430.03

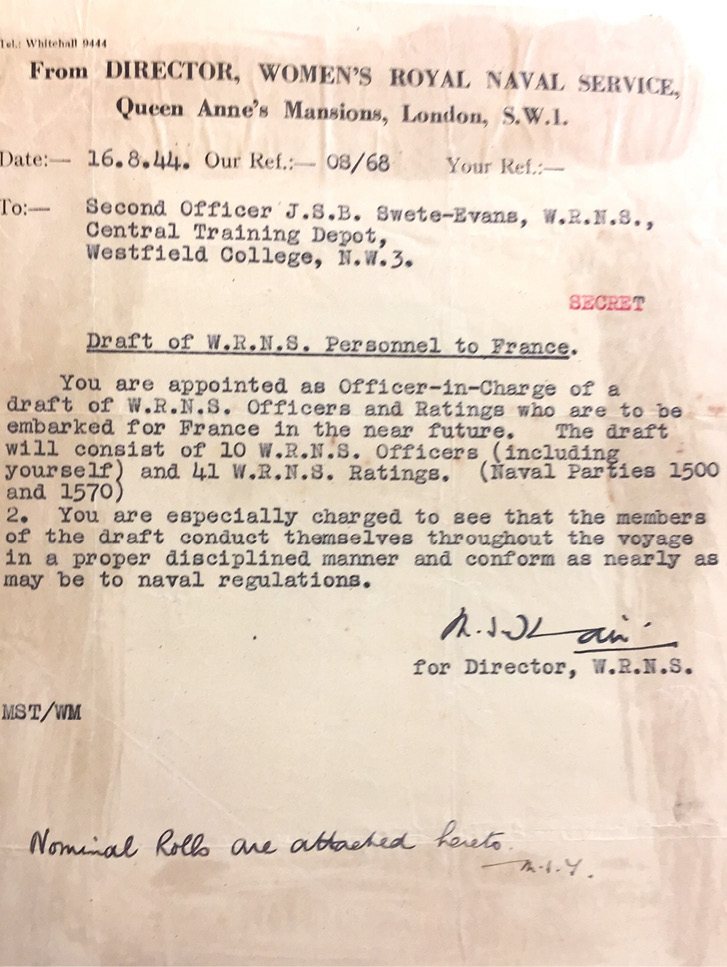

Fig. 3.1. Order from Director of WRNS to J. S. B. Swete-Evans (2/O Wren), 16 August 1944. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

The Headquarters of ANCXF and the naval parties on the Continent needed WRNS staff badly, and a month after D-Day the Deputy Director Welfare, Superintendent Goodenough, crossed to France to inspect accommodation and see whether suitable arrangements could be made.1

Wrens were not compelled to serve overseas, and some declined the opportunity. But, by the time of D-Day, it was not entirely voluntarily either. Crang records that whilst ‘women over twenty-one were eligible to volunteer, with parental consent needed for those under that age’, by 1943, because the demand exceeded the supply of volunteers, the Admiralty ‘placed a liability for compulsory service overseas on “mobile” WRNS officers and ratings over the age of twenty-one, except in cases where this would cause “undue hardship”’.2 And, Roberts writes, ‘compared to the other women’s auxiliaries, the WRNS had a much larger proportion of servicewomen in foreign locations […] [where] the biggest roles were for writers, wireless telegraphists, domestic branch and stores workers’.3 Supply was not a concern for ANCXF however. Indeed, Ramsay wrote to his wife as early as 11 July 1944: ‘we have so many Wrens now with us that the question of whether conditions will permit of taking them too looms large’.4 The majority was only too keen. But not all were chosen.

In many overseas theatres volunteers were screened closely, as one of Roberts’ interviewees attests. Jean Matthews, a coder at Bletchley Park, attended a selection board where she was ‘questioned for her suitability’ before being posted to Ceylon. She reflected, ‘they were very careful [about] who they sent abroad’. And she was asked by the Chief Officer ‘what her parents thought about it’.5 Joan Prior’s mother, Grace, told her exactly what she thought about her twenty-one-year-old daughter signing up to go to France. But Joan, with her father’s blessing, defied her. As Summerfield concludes, ‘the emphasis on a father’s approval of a daughter’s war work could leave […] a disappointed mother in the shadows of the account’.6 Joan’s first letters home from Granville allude to this tension.

Joan had never been abroad. For Wrens from more privileged backgrounds who had holidayed in Europe before the war, like Second Officer Elspeth Shuter, the privations of travel courtesy of the Royal Navy and the devastation and hardship they encountered on the far shore provided a stark contrast with their peacetime experiences. For Joan and many others, there was nothing with which to compare what awaited them. Yet their reflections and observations cannot entirely disavow a touristic gaze upon the dishevelled seaside town of Granville. Nor can they quell the spirit of liberation that was in the air. Indeed, as the testimony which follows shows, the Wrens of ANCXF manifested an almost carnal desire to follow in the footsteps of the men whose fate they had helped to design, not just to put themselves in their shoes, but to embody them.

Although Joan had revisited France on a commemorative tour of 1994, in the company of other veterans, the far side of the Cotentin peninsular, out on a limb, had not been on their itinerary. She returned with a pouch of photographs, of beaming genteel ladies and elderly uniformed gents, seated at tables, posing between the courses of another French civic lunch. When I took my mother back to Granville in 2004, at the summer’s end of the sixtieth anniversary year, it was already too late to rekindle memories by recognition. The walls were silent. We wandered the streets of the oblivious town, searching fruitlessly for something that was long lost.

3.1 Embarkation

MARGARET BOOTHROYD: Just a short time after the 6 June lists went up for volunteers to go to France. Some teleprinter operators would be required to join Headquarters as the Allies pressed forward on the Continent. Many put their names on the list and so did we, and the suspense was terrific while we waited for the names of those accepted to go over to France to be posted on the notice board.

There were around twenty teleprinter operators needed, and those not accepted just wept. How pleased Laura and I were to be amongst those going. Wrens under 21yrs had to get their parents written permission, so Laura’s parents obviously gave their permission for her to go abroad in the same way as mine did.7

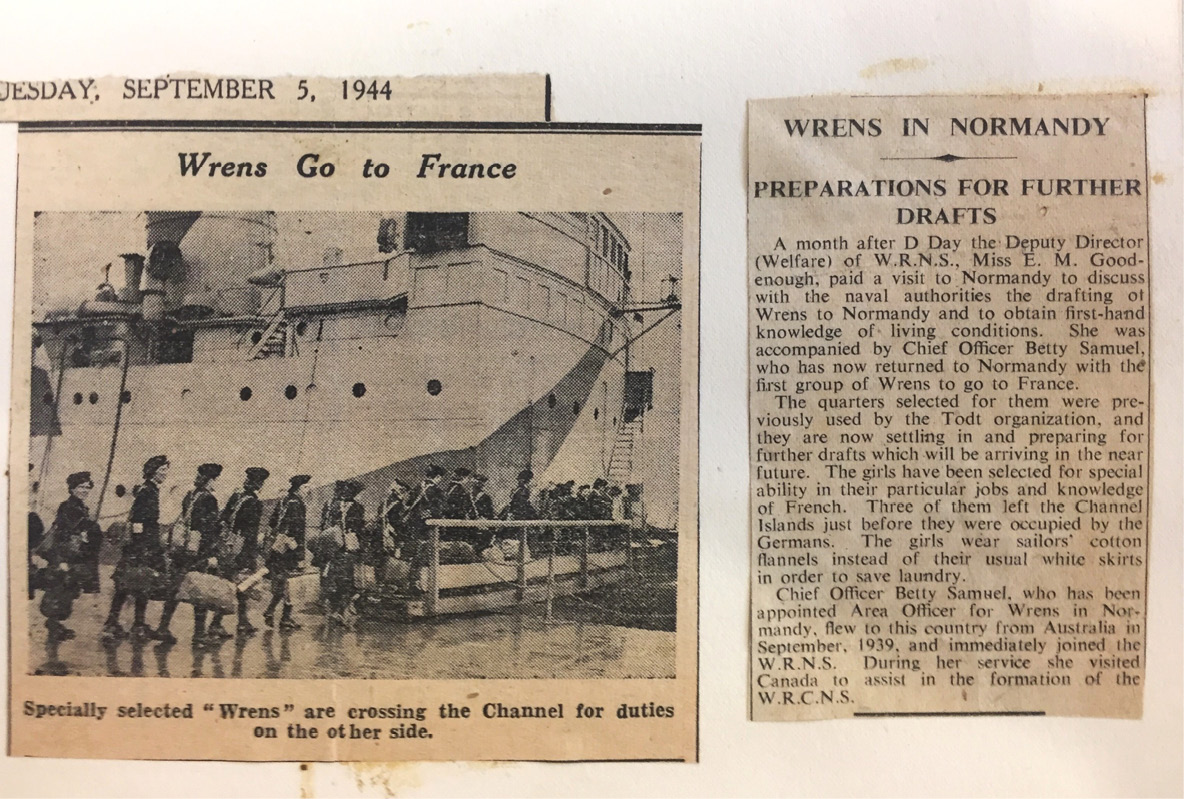

JEAN GORDON: In September, those Wrens who had volunteered for Overseas service were sent on embarkation leave before going across with the HQ to Normandy from where Admiral Ramsay would, as ANCXF, continue to direct operations.8

FANNY HUGILL: The effects of bad weather and reverses in the field delayed our move to France.9 Early contingents of Wrens sailed during August, and the full staff moved to Granville on the Cotentin Peninsula early in September.10

Fig. 3.2. Contemporary newspaper reports of Wrens embarking for duty in France. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

ELSPETH SHUTER: An advance communications party and the officers and ship’s company of the good ship HMS Royal Henry, which was to sail us through France, had gone before.11

‘Bobby’ Howes was in the advance party:

We left Portsmouth at night by destroyer and crossed to Arromanches, where we transferred to a landing craft which took us alongside the Mulberry Harbour. A 15cwt truck was waiting for us and it was a long, dusty ride along bombed roads to Granville on the West coast.12

SHUTER: Then at the beginning of September, the Headquarters’ Staff of the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief Expeditionary Force, moved across to France. We went in dribs and drabs over a period of a week or so. ANCXF still functioned from England when the move started. However, after a few days the communications system on the far shore was established and in working order. Key personnel were there to speak with the voice of ANCXF. Then Admiral Ramsay himself crossed over and the command went into action from Granville in Normandy.13

On 8 September—D plus ninety-four—I too crossed to France. It was much too long after D-Day for my liking! If I had had my way I should have been over early on walking the beaches in search of wrecked and damaged craft. But alas, being a woman I would have been a beastly nuisance!14

Fig. 3.3. Wren officers departing for France, September 1944. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

GORDON: Our journey to France started, for some reason, in Whale Island,15 where we spent the night. We were awakened next morning, like everyone else, with “Show a leg there, wakey, wakey, wakey”, over the loud-hailer. We then embarked, in charge of our kit, but not carrying it as it consisted of enormous green canvas kit bag nearly as big as ourselves, containing a canvas bath, bucket, bed and bed-roll. In another bag, nearly as big, were out “personal” effects, consisting of our uniforms, including bell-bottoms and jerseys and duffel coats and wellington boots, and as many personal garments as we could stuff in. No civilian clothes allowed however. We had gas masks, tin hats, and each had an enamel mug, knife, fork and spoon. My gas mask with tin hat and my “eating irons” attached, fell off the back of our lorry early on in France, and I suffered miserably from the loss of the latter, and had great difficulty in explaining the disappearance of the tin hat and gas mask to a disbelieving Purser two years later, when I was demobbed.16

BOOTHROYD: We were taken to Portsmouth Dockyard and further equipped for our journey. Bell bottom trousers, square-necked tops, navy blue shirts and jersey, fawn duffle coat along with all the green canvas equipment normally provided for Officers and previously described. Getting everyone equipped and off to France must have been a tremendous job. We had our embarkation leave and were home for a fortnight. Following the D-Day landings there were a number of set-backs and the Germans fought hard to hold their ground. The city of Caen was difficult to capture. When we left Southwick we were very excited and looked forward to the journey. After embarking we “stood off” the Isle of Wight overnight and then made a run for it across the channel, early morning. We had boat drill and the Matelots took great delight in saying, “Last time across a boat sank here or there”, but we weren’t in the least impressed. I don’t remember myself or my friends expressing any fear whatsoever. Our age, the job we had been called to do and the excitement all played a part in our being completely confident. The thought of going into the unknown, or death never crossed our minds... we always thought we were on the winning side.17

Fig. 3.4. Wrens boarding an LSI, September 1944. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

3.2 Channel passage

As Crang notes circumspectly, ‘the despatch of sizeable numbers of servicewomen overseas brought to the fore the question of trooping arrangements for the women’s services’.18 Beryl K. Blows had the opposite difficulty: ‘I was the only woman to sail in the LSI Queen Emma, which I am afraid somewhat inconvenienced the ship, but everyone was helpful, especially the Secretary, a Lieutenant RNVR whom I met nine months later in Germany’.19

Shuter found the whole experience thrilling:

This crossing was to be one of the greatest memories of my life. We went on board HMS Brigadier, an LSI—Landing Ship Infantry—during the afternoon. In peace time our LSI was one of the cross-Channel packets running the night crossing from Newhaven to Dieppe. We were quite a big party of Naval officers, Wren officers and Wren ratings. The captain of the ship and his officers did everything to make us welcome and comfortable. I was shown the saloon fitted with bunks which was to house the Wrens, officers and ratings. There were profuse apologies because the accommodation was limited and we would have to sleep altogether. What did it matter? […] And the Wrens, many of whom had not been out of England before, were delirious with excitement.20

Gordon’s first impressions were less conducive:

We embarked into what must have been some sort of cross-channel steamer. Our quarters were below and had bunks in two tiers round a living space with a table at which we ate. Whatever male personnel had recently occupied it left the blankets unmade, and a smell of stale tobacco smoke.21

Wren officers like Shuter were able to rise above this:

Felicia and I were asked up to the Captain’s cabin. We received more apologies for the poor accommodation. But sitting there and sipping our drinks, we told our host that we couldn’t imagine what could have been more pleasant…

Towards midnight I went below to see the Wrens. They were all in bed—in their nighties—just as if they were safe in their beds at home, and apparently devoid of any fear of enemy action. What implicit faith in the Royal Navy! I remembered vaguely having seen an AFC which said that Wrens at sea must sleep in their bell-bottoms. But my request that they should get into their slacks was met with consternation on all sides. Most of them had packed them away in their heavy luggage! I had visions of the ship being torpedoed and of dozens of flimsily-clad Wrens mustering on deck. We had been issued with natty little life-jackets that you could wear quite flat, even inflating them after you were in the water. With groans I got them into these life jackets—most of them had no idea how to put the things on. I must admit that I hadn’t much idea either, but by the time I had inspected and instructed thirty odd Wrens I was a dab at the job. Oh, they were resentful at being made to sleep in the wretched things!

I think the Wrens regarded the crossing as a joy-ride and I thanked my lucky stars that I had not been born to be an Administrative Wren Officer. For when I went to bed that night a small deputation was waiting to ask if they could go up on deck as they were so hot! “What next?” I thought: “A pleasure cruise, was it?” And one girl travelled in a brand new pair of shoes! Wren shoes are always diabolically hard for the first three weeks. […] Poor dear, she was limping around with her heels hanging out of the backs before we arrived.

In the early hours we slipped out of the Spithead, two other LSI in company, and escorted by HM ships Lapwing and Narborough.22

GORDON: We sailed that evening. Many were sea-sick and when we woke at night cockroaches scuttled in their thousands from the light of our torches across the floor and the bulkheads close above our faces! We sailed in convoy, guarded by armed naval craft.23

‘GINGE’ THOMAS: My most vivid memory of crossing the Channel was hearing the ship’s Tannoy blaring out, over and over again, Bing Crosby singing “Would you like to swing on a star?”.

SHUTER: At first light I was up on deck. The Brigadier was cleaving through the water. We led the column followed by the other two LSI, while on each quarter our escorts were keeping guard like faithful watch-dogs. A thrill of pride went through me as I looked at the little convoy, silver grey in the morning light.

Feeling a great sense of security now that it was light, I told the Wrens that they could take off their life-jackets as long as they carried them. As the chill drained out of the morning light I began to think that I had been awfully fussy the night before. It seemed so safe now as the sun began to climb into the sky. Then, quite suddenly, came the voice of the First Lieutenant from the bridge, “Second Wren, will you see that your girls are now wearing their life-jackets. We are entering the danger zone!” I couldn’t look a Wren in the eyes for fear of seeing reproach for the night spent in unnecessary misery.

Fig. 3.5. Wrens on deck, travelling to France, September 1944. Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans, Documents.14994, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

It must have been about eight o’clock when we first made out the coast of France showing hazily on the port bow. It was Le Havre which at that time was still held by the Germans.24 Then we heard the noise of aircraft. Soon bombers from England were milling overhead until the heavens were throbbing with the roar of their engines. They seemed to circle over us before starting the run in to bomb Le Havre. It was most exciting. The little blob of land we had seen on the horizon soon disappeared behind a pall of smoke, and the bombs that fell short threw up great plumes of water. Other bombs were jettisoned quite near us and it was as if we were surrounded by giant whales at play.25

GORDON: In passing Le Havre […] we watched our own planes bombing it and were ordered below and “battened down”.26

SHUTER: There was never a dull second. We were now overtaking LCT and LST convoys, and ships returning to England were passing us. I dashed in delight from one side of the ship to the other. Then I had to tear myself away and go to breakfast.

3.3 Landfall

SHUTER: On coming on deck again there was land stretching away on the starboard beam. Now we were seeing the east coast of the Cotentin peninsular and somewhere in front of us lay the assault area, though it was not yet visible. I realised we were just about in the position in which the assault forces had been when, on the morning of D-Day, I had crept into the plot to see how things were going. How exciting it was! Ninety-four days ago, and now the Allies were beyond France racing for the German border.

I gazed at the horizon ahead and gradually the blur of a great city began to appear—once again I could see factory chimneys! It was of course the British Mulberry harbour at Arromanches distinguishable by the towers of the spud pierheads—one vast concentration of shipping spread upon the sea. We strained our eyes—now we could make out the concrete walls of the harbour and the individual shapes of the ships anchored outside. A big convoy of ocean-going troopers was anchored off the harbour and, within, the funnels and masts of many ships showed tall above the harbour walls. The port was working to capacity.27

GORDON: On arrival on the “Far Shore”—the name always used in the plans as much for ease of reference as security—an amazing sight met our eyes. As far as one could see along the coast there were naval craft of all types, steaming back and forth and unloading their cargoes of weapons, supplies and personnel onto the beaches via the “Mulberry Harbour”, now in place with all its floating piers, “Gooseberries”, “Whales” and “Beetles”. We excitedly identified most of the installations and ships whose names had been familiar to us on paper during the last year. It was a thriving, busy port with all the accompanying noise and bustle.28

SHUTER: We too dropped anchor outside the harbour and, fascinated, I watched the ferry craft—my ferry craft!—loaded with troops and stores disappear inside the harbour entrance to be off-loaded at the pierheads. Then our turn came. We disembarked into an LCT bobbing alongside the Brigadier. Slowly we passed through the harbour mouth and there lay our artificial port—Port Churchill as the French affectionately called it! It seemed to be exactly as it had been planned and laid out in the model we had kept behind locked doors in Norfolk House. In those days, I had looked at the model and had tried to visualise how the real thing would appear, and I had failed. The difficulties and hazards, the problems of production, the shortage of suitable tugs for towage—all these troubles and others lay between the model and reality, and it didn’t seem possible that we could win through. But, we had won through for now I was seeing reality!29

This dramatic landfall, so intricately planned and so often imagined by the Wrens themselves, was worked over time and again in their shared memories like clumps of French knots in the Overlord Embroidery.

THOMAS: Near the coast of France we had to disembark onto landing craft, and then we landed on the wonderful Mulberry harbour. We had typed about it hundreds of times but were now seeing it for the first time.30

BLOWS: It was a thrilling moment to see actually in use the harbour on which I had last seen men working day and night at the main south coast ports, and without which such success could not have been achieved.31

GORDON: We were transferred with our office equipment, including the steel cabinets, onto a landing-craft to be taken to the Mulberry so that we could get ashore. As this was flat-bottomed it heaved and rolled with the swell and we were able to experience a very little of what it must have been like for the assault forces.32

Fig. 3.6. Wrens of ANCXF on board an LCI preparing to land at Arromanches, 8 September 1944. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

SHUTER: The harbour walls reached out—great curving, protecting arms—and enclosed a vast millpond in their embrace. While outside the waves fretted and broke against the walls covering them with spray, sucking back again defeated and deep green with jealousy.

We landed at a pierhead, the whole structure lifting slightly with the swell. Cranes were working, lorries being loaded, men were giving orders, and tanks and vehicles moving away in a long, continuous stream. We were packed into cars and joined the procession bumping down the great length of the swaying pontoon causeway—and so onto dry land. Thus it was we landed in France!33

BOOTHROYD: When we arrived off the Normandy coast rope netting and ladders were thrown over the side and we actually clambered down this from the ship onto the Mulberry Harbour at Arromanches and then went by transport across country to Granville.34

GORDON: In due course we landed on the Mulberry and were driven over the floating piers (waved at and cheered by anyone who caught sight of us!) and landed in Arromanches.35

Hugill recalls, ‘[we] landed at Arromanches on a beautiful morning. A fleet of lorries and cars awaited us, and the sound of the tyres on the ramp of the Mulberry harbour is something I shall never forget’.

SHUTER: I gazed and gazed at that wonderful harbour; at the still, imprisoned water; at the mass of anchored shipping; at the ferry craft scurrying to and fro; at the busy pierheads; at the long causeways; at the continuous flow of traffic and, above all, at the very vastness of it all. I wanted to have it indelibly written on my mind, for with the capture of real ports to the north, ports that were nearer to our armies, the Mulberry harbour would soon have served its purpose.36 Then the units that went in the making would be towed away again, and once more Arromanches would slip back into being a quiet little Normandy fishing village.37

3.4 On the road

GORDON: We were then transported in large lorries—or Naval Transport Vehicles (Personnel). They had benches and were covered in an awning which could be removed in hot weather and closed in cold. They were quite difficult to climb into in fairly tight skirts and were dusty and noisy.

We were driven down the “Red Ball Convoy Route” which the main roads supplying the Front Line was called.38 This again was a hive of activity with vehicles of all kinds trundling down it and taking precedence over us (while we waited in a siding to let them pass). As we travelled we saw some of the devastation of war in the blackened wrecks of tanks and big guns and other vehicles by the roadside, and the ruins of buildings and the great gaps torn in the “bocage” by the tanks.39

HUGILL: The long drive to Granville was like a royal progress. We waved and waved. Battle-hardened as we were by the effects of bombing at home, we were shocked to see the devastation of so many French towns and villages.40

SHUTER: The drive from Arromanches across to Granville on the west side of the Cotentin peninsular was intensely interesting. Great dumps of stores spread out on either side of the road for mile upon mile. The white dust was inches thick. The roads were solid with heavy army vehicles. We met a column of German prisoners marching along in the dust. I felt I was in the thick of the battle!

We skirted Bayeux and soon we were entering Saint-Lô. This was the first time that I had seen the result of carpet bombardment. It will be remembered that when the Americans broke out of their bridgehead the Germans were resisting in Saint-Lô. Warning was sent to the civilian population exhorting them to leave the town. Then Saint-Lô was devastated by heavy air bombardment and the next morning the Americans moved into the town. We were driving through it now. Perched on a hill it had once been a charming little town. Now there was not a house that was not in ruins. The west end of the church lay sprawled into the market square. Everywhere was complete desolation and utter ruin. It was formidable! I had never seen such utter destruction. Never. Saint-Lô had only been a little town but now it did not exist at all. Two Americans were travelling in our car. They were very upset by the sight and they instinctively turned up their collars and slumped down in their seats, lest the few inhabitants should see them.41 We, the Allies, had been waging total war round Saint-Lô, fighting for our lives. If the destruction of the town had been necessary, then there was nothing to be ashamed of—it was a tragedy, but not a crime—and yet we felt that we were looking upon an act of criminals. It is one thing to hear someone else say that a place has been totally destroyed, but it means something more when you have seen it for yourself.42

Fig. 3.7. Photograph of Saint-Lô, September 1944. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000026, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

THOMAS: I remember travelling through Saint-Lô, and being astonished at the amount of damage there had been to the place. I was used to bomb damage because Swansea had been badly damaged, but the devastation here was breathtaking.

As we travelled through Normandy, troops would stand outside their tents waving at us—they probably didn’t see many girls around there!’43 That was a thought echoed by Elspeth Shuter’s friend Barbara Buckley: ‘the French threw flowers and opened windows. We sat on the back of a jeep, waving. We were delighted. We could see what sort of conditions they were in. They saw we were women and did not expect that. They seemed surprised.44

3.5 Views of Granville

GORDON: Eventually we arrived in the town of Granville on the [far side of] the Cherbourg peninsular, where Naval HQ was set up and where we took up our quarters in vacated houses in the main street. They were clean and well-swept and empty, but ours had apparently been a “delousing” centre for captured German prisoners before we occupied it.

Before going to bed we had of course, by torchlight, to unpack our kit bags and assemble our beds—not easy (but worse trying to get them back later into the bags!), and then go down to the Mairie in the centre of town to eat and to collect a bucket of water each, as this was the only source of water. One became quite adept at washing the whole of one’s person (again by torchlight) in one canvas bucket, being careful to remove a mugful for one’s teeth first.45

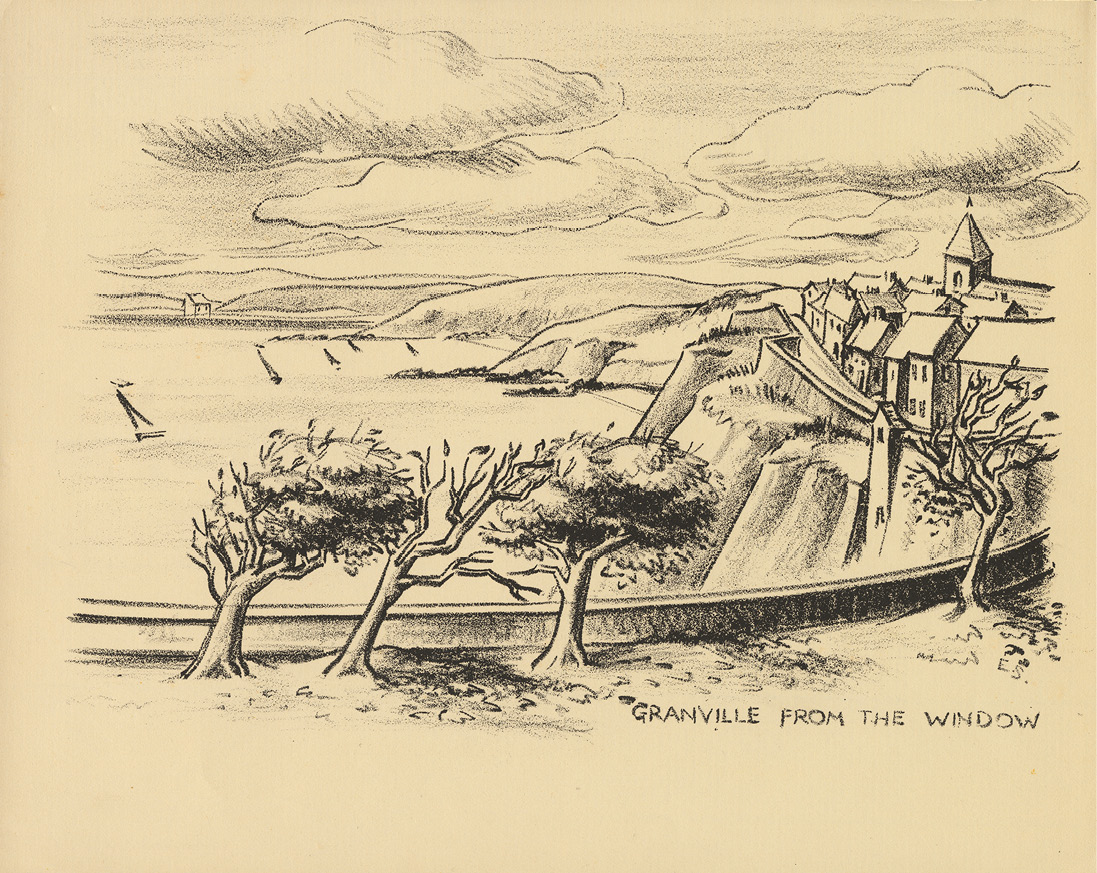

SHUTER: Granville was enchanting and very little damaged. The old town clung together on the top of a high rocky promontory thrusting out into the sea. There was a glorious open sweep of coast to the north and, on a fine day, Jersey (still occupied by the Germans) was clearly visible. To the south we looked down onto the fascination of a harbour and port, and beyond to the new town of Granville lying at the foot of the rock. Beyond again, the coast stretched south to the Bay of Mont St. Michel.46

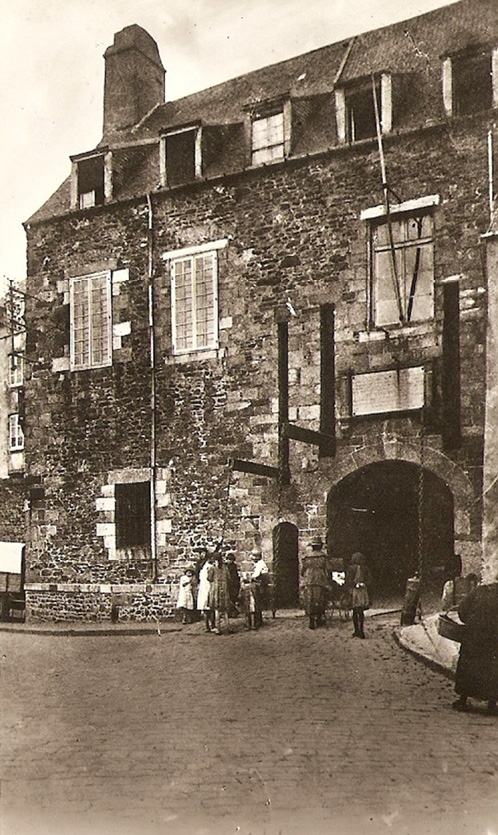

HOWES: Until the main party arrived we lived in a French guesthouse and had meals with the American GIs in the casino which was great as their food was good. Then were told to move into an empty Medieval village called Hauteville which was surrounded by a very high wall and entered by a portcullis bridge.

Fig. 3.8. Postcard of the gateway to the Hauteville, Granville. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

The main party were due to arrive that day but they didn’t turn up. So we four Wrens chose an empty house in a side street and barricaded ourselves in a room on the second floor with our kitbags. We slept on the floor with our gasmasks as pillows and covered by our duffel coats, ever mindful that the Germans were just across the water in the Channel Islands. What a relief when the Main Party arrived next day.47

BOOTHROYD: Each time we moved, all we needed was an empty room and out came the bed, bedding, chair, washbasin, bath (never used) although we did have baths! Bucket and kitbag and we were set up. We had been issued with a tiny stove, biscuits, a small pack of dehydrated food and tiny sachets of Nescafé (the first I had seen). Laura [Mountney] and I were given this empty room in a house in a street just inside one of the huge stone gateways into the old walled part of Granville. We worked in a large factory type building further around the harbour. The field teleprinters were set up and work began. We did have a little time to look around Granville and later some places around St. Malo.48

Fig. 3.9. View of the Wrens’ quarters (left) and barracks (distance) on le Roc de Granville. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

HUGILL: Arriving at Granville, we viewed our filthy quarters in houses only recently vacated by the Germans. Before erecting camp beds, we opened the windows and washed the floors. There was little electricity, and, not allowed to drink the water, we got a taste for the plentiful wine. The beach was not mined, so we paddled, and the pretty little casino, which only recently entertained the enemy, was in full swing.49

SHUTER: The Americans were busy in Granville getting the port into working order. While we were there the Casino was opened as an Officers’ Club. The atmosphere should have been alright, it seemed to be decorated in the traditional white and gold, you sat in rich red velvet chairs, an American band played dance music—but there was something garishly dead about the place. I hated it. Perhaps the black-out, which did not allow the tall French windows to be open to the terrace and the sea, nor any sound of the sea to be heard above the tuneless blare of the band, was the cause of the depressing gloom that pervaded the place.

There was one ill-fated party at the Casino. I was not there but I was a witness to the devastating effects next morning. That evening the Casino had been supplied with cognac which was captured Wehrmacht stock. And it was bad stuff. Next morning a sea of faces, in varying degrees of greenness, mustered for the staff-meeting. One of the staff, who was all behindhand, sat sorting his signals during the meeting. As he read them he placed them on his foot which was crossed over the other leg. The meeting progresses and the pile of signals grew higher and higher. Fascinated I watched, waiting for the whole pile to topple over! Cognac was given a wide berth after that experience.50

BOOTHROYD: There were some women around the town with shaven heads, mostly wearing scarves. We were told these had fraternised with the Germans. Now this does not seem a great crime and for some of those women, circumstances must have been very difficult, but in 1944 we were absolutely amazed that anyone would have wanted to have anything to do with a German. Granville—at any rate the part we lived in—was quite desolate when we arrived. There were still dead bodies around and many derelict properties, some had been bombed, but the French were glad that for them the war was over and soon they returned to their homes, shops opened and the church once more tolled its bell.51

Fig. 3.10. Postcard of The Casino at Granville, in pre-war days. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

SHUTER: The Headquarters of ANCXF were in the barracks at the extreme seaward end of the headland. I felt that I had got to sea at last! For if you looked up quickly from your work and straight out through the open windows, there was nothing between you and the sparkling blue sea, and your lungs were filled with the clean salt air. I was happy to be there—very.52

GORDON: We could walk to work in the Naval HQ which was in a large French barracks directly overlooking the sea. From the sea wall we watched the Germans on the Channel Islands opposite through binoculars.53

SHUTER: A steep street, clinging to the edge of the cliff, climbed up from the port to the old town. It then swung in under the great portcullised gateway set in the rock face. Once inside, the noises of the lower town and the sounds from the harbour dropped from you. You were in a hushed, deserted place, the silence broken only by the clatter of your own shoes or by a peal of Wrens’ laughter. For we, the Navy, were the only living things in that sleeping place.

We were quartered in the dignified early renaissance stone houses. They were gems with their fine doorways and exquisite panelled rooms. The Wren officers, rightly or wrongly, lived in a Nunnery! K and I shared an attic which was reached by tortuous spiral stairs. The house was built high on the edge of the rock and, leaning from the window, we looked straight down into the pool of the harbour—just as you might lean over the edge of a wall and look straight down into its still depths.

The old town had been cleared of its inhabitants when the Germans were in occupation. But while we were there the local people began to trickle back, their possessions piled high on handcarts. During our stay a service was held in the little old church that crowned the promontory. This was the first time that the church had been used since the Germans had arrived in 1940. A little procession, bearing the statue of the Virgin in their midst, climbed the steep streets singing as they came. Little girls in white carried bunches of flowers and the women were in the local costume with stiff, white starched headdresses. It was quite a simple little procession and somehow touching.

Fig. 3.11. ‘The local people began to trickle back, their possessions piled high on handcarts’. Private papers of Mrs B.E. Buckley, HU_099996, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

Fig. 3.12. ‘The local people began to trickle back, their possessions piled high on handcarts’. Private papers of Mrs B.E. Buckley, HU_099995, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

We lived and worked under conditions more austere than any we had met with before. We had come over to France with great, green canvas camp valises. Everything in mine was now in use—camp-bed, canvas chair, canvas bucket, washbasin and bath. For there was no furniture left in the houses of the old town. In the barracks we sat on camp stools working at narrow army tables—and the roof leaked! With a plop! Plop! The rain used to splash down onto the floor behind me. Our uniform too had gone to action stations. Even the Wren officers wore battle blouses crowned by berets, with the cap badge worn saucily over one eye. We were in the American sector and so we lived on US rations, and very good they were. We had fruit juice with our breakfast and snow white bread. But the dehydrated potatoes made me feel almost in the front line!54

GORDON: As we were in an American “zone” we were victualled by them, another hardship as their “hard tack” biscuits—instead of bread—had a sweet taste, there was no tea, and too much salty “pork and beans” and peanut butter in their rations. All came out of tins of course or was the new dehydrated food which had recently been devised. It was our first taste too of “instant coffee”.55

Fig. 3.13. ‘Granville from the window’, sketch by Elspeth Shuter. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000032, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

BLOWS: We lived by candlelight at this small peace-time holiday resort, in a somewhat bomb-scarred French house. Water had to be collected from tanks outside the house, and a bath was out of the question.

Gum boots and battle dress were the rig of the day, for our rapidly advancing tanks had made havoc of the Normandy roads. […] We had anxious moments too, when the supply of candles ran out, and when a pig started eating our underclothes from the line.56

SHUTER: We had felt that when we left England the work would fade away. But this was not so. Two operations were being planned: NESTEGG and INFATUATE. “Nestegg”, the proposed assault of the Channel Islands, was being mounted from the Plymouth Command. It was later abandoned as the pre-assault bombardment would have been so costly in civilian lives. It is no good “liberating” anyone if you have to kill them in the act. “Infatuate” was the proposed assault on the island of Walcheren. This was now necessary to secure entrance to the Scheldt and to the great port of Antwerp. The value of Antwerp was immeasurable as it had been captured almost intact and, by its position, it would offer the shortest supply line to the Armies.57 So we were busy deploying our assault ships and craft to meet the requirements of these two operations. At the same time we had to take care that the rate of the Build-up was maintained. It was agreed that the ships and craft required for “Nestegg” should remain in the Shuttle Service, but that they should be held at a few days’ notice for the operation. A new force—Force “T”—was formed and trained for “Infatuate”.58

Ramsay’s command was also responsible at this time for establishing a system for repairing and restoring to operation captured deep water ports as soon as possible. What hadn’t been bombed by the RAF had been mined and blocked by German sabotage initiatives, to thwart the Allies’ invasion supply lines. Cherbourg, which had been captured on 27 June, was the first, where the team led by Commodore T. McKenzie, the Principal Salvage Officer on the staff of ANCXF had the port operational by early September.59

In gaps between work in the office, Joan Prior had begun writing home soon after her party’s arrival. A letter dated 10 September is the first surviving report, but clearly not the first to have been sent. The missing letters themselves may not have been received, which might explain her mother’s reported anxiety. By her account, a lot has happened already. As will become characteristic of her epistolary style, Joan is replying to her parents’ family news as well as relaying her own activities. This balancing act was vital to the success of correspondence of service men and women writing home.60 Her concern here is for their safety as Hitler’s V2 rockets supersede the V1 flying-bomb campaign. From the start, Joan’s day-by-day resumés are typical of her letters. In later life, if you asked her what she’d been doing, she would begin: ‘well, on Monday…’. As a young woman, already the more she wrote the less she was saying. Her wartime letters were subject to censorship of course; but self-censorship was the prevailing force. It was always about what was left unsaid, reading between the lines. But what endures most vividly is her prosaic sense of wonder, on the threshold of this brave new world.

Wren J. H. Prior, 41801

Naval Party 1645,

Berks

Sunday 10th September 1944

Dear Mother and Paddy,

Here I am once more, and must endeavour to remember all that’s happened since last I wrote—I don’t know whether I’ll succeed, but here goes.

I wrote you on Tuesday, well on Wednesday Kenn and Ginge and Ken61 and I (the two Kenneths are Marines and are very nice boys indeed) went into a town a few miles from our Quarters and spent the afternoon there.62 We bought gifts for the boys to send home to their mothers and sisters, like perfume powder, and lipstick etc. and I bought some face powder there for Bessie’s birthday. Then came the loveliest find of all as far as Ginge and I were concerned. We saw in a shop window some tiny little coloured coats-of-arms of the various French departments and towns which had small links at the top and could be attached to a chain. There-upon we were swept into the shop and we each chose about a dozen of these together with a bracelet to fix them onto and as I type this I’m proudly wearing the complete thing. The boys fixed them on for us while we were buying cosmetics etc. and on one occasion we came out of a shop to find them surrounded by French kiddies all intently watching the procedure!

In the evening, we held a Dance at our Quarters to which all the Marines were invited, and we had a very enjoyable evening, except when the French band couldn’t be made to understand the sort of music we wanted and played all sorts of queer tunes!

I’m afraid it’s now Wednesday 13th and I’m endeavouring to get on with this letter to you, but when I have to stop it sort of breaks the trend of thought so to speak.

On Sunday I went to Paris! What a thrill! I’ve wanted to go there ever since I landed on French soil and at last managed it. We saw the Arc de Triomphe, walked down the Champs Elysees, visited the tomb of Napoleon, saw the Eiffel Tower and Louvre and all sorts of things.

It’s a very lovely city, well laid out, clean and almost every street of importance is wide and tree-lined and just now with the leaves turning colour they look wonderful. The fashions are incredible—the hats fantastic! They’re tall and queer-shaped and are the vivid colours imaginable. The suits here are being worn with long tailored jackets and short knife-pleated skirts. The latter seems to be a popular thing just now as most of the frocks are close fitting well below the hips and then froth out for about 8 inches in knife pleats sometimes of an entirely different shade. I don’t know whether these fashions will ever become popular at home but at least the French women can wear them and get away with it.

There, I’ve just had another interruption and now it’s Thursday 14th—I’ll just never get this letter finished and posted to you I know.

On Monday, Ginge and I decided to do some washing so we had supper quickly and dashed back to our cabin, sorted out all the things we had to wash, grabbed our canvas buckets and went to fetch the hot water. To do this we had to walk some way through the trees, along the terrace, down a flight of stone steps, across another open stretch and so into the Mess. To our joy the water was hot—it’s usually the reverse—so we trailed all the way back to our cabins this time carrying the hot water with us. We were just longing to get down to this dhobeying,63 in fact we could hardly wait and things seemed to be going so very well we just couldn’t believe our luck. Then the first tragedy happened. Just as we’d got our clothes nicely dipped in the hot water—out went the lights! There was a scuffle of feet and a good deal of mumbling and out of nowhere came two candles. These were lighted (when we found the matches) and we could just discern faint outlines then, because by this time it was quite dark outside. I could see Ginge rubbing away and Ginge could see me. What we neither of us could see was what we were washing and whether we were getting it clean. Anyhow, with true Wren philosophy we decided to give each thing that came to hand a time limit, we rubbed for say 5 minutes and then dipped and then rubbed again and then wrung it out and put it in a towel for the time being. At the end of about an hour the lights functioned once again and we were able to see the results of our efforts. Just as well you weren’t there because I’m afraid some of the things weren’t too clean, especially hankies. How would you like to do the weekly wash under such conditions? Still we get a laugh out of it really.

On Tuesday I was “Duty Wren” and part of my duties was to “man the library”. There I found a very good book entitled “Polonaise” and dealing with the life of Chopin which I am endeavouring to read, but only manage about three lines just before the light goes out at night.64

Last night we were Duty Watch and didn’t get back to our quarters until about 9–15 so on the whole I think I’ve managed a very rough summary of me and my doings in the past week.

I’ve been much busier than usual during the past week as one of the girls here who works individually for an officer has been away and I’ve been doing her work. She certainly has a full-time job as I’ve hardly had a minute to spare, but it’s quite interesting and I’ve enjoyed it really.

Please, please could you let me have Charlie’s address?65 I do want to write to him and haven’t the remotest idea where to send a letter.

I do wish Grace and the kiddies hadn’t gone back to London.66 They were comparatively so safe where they were and I know that London is still at the receiving end of quite a few nasty ideas and shall worry about them being back. I expect Charlie will worry a lot too and I do think they should have stayed where they were for just a wee bit longer.

I don’t know anything about being home for Xmas as leave hasn’t been mentioned yet and of course we can’t really expect it—after all it’s not as though we’re in need of the rest or anything as we’re so very well looked after and at the moment the prospect is very dim of anything like that. However, I’ll bear in mind the compact and will most certainly buy one for her. I’m glad she said what she wanted as then I shall be sure it’ll be welcome—it’s so difficult to get people something they really want, so if Grace or Bess or indeed anyone Mother knows I shall send something to can be persuaded to tell me, I’d be grateful.

My love to Ida67 and to all at Trevale68 and of course to Mag and Fred69, not forgetting you both. God Bless and don’t worry about me please.

Lots of love from Joan. xxxx

* * *

Thursday 14th September 1944

Dear Mother and Paddy,

Last night I received your letter dated 10th September which meant it only took three days, so the mails here are looking up definitely.

I must say I was a little hurt at Mother’s attitude as I’m afraid it isn’t always possible for me to write and furthermore because of this, not possible for me to explain. You understand enough about the sort of work I’m on to know this by now, but I’m really sorry to know that it did cause you so much worry. In any case you end by saying to write once every week. Previously you say that you had waited eight days for a letter—well, that’s only one day over a week after all.

However, once more I apologise, though I still can’t explain, and please if in future a delay does crop up, try not to worry too much, although I know it must be difficult for you and is only natural.

As you say, the doodle-bugs certainly seem to be a thing of the past now and I shall write to Grace at 21 Glenny70; then Mrs. Snell can read them too.

I’m sorry the weather wasn’t too good for Mr. Snell as it makes such a difference down there doesn’t it?

It’s a good thing they’re starting on the repairs to the house isn’t it?71 I expect you’ll be able to go home quite soon, and although I think it did you both good to spend these past weeks down at Burtle, with the winter coming on it perhaps wouldn’t be so good.

In view of what you say about going over to Joyce’s I’m addressing this letter there in the hopes that it gets there quicker that way, although I sent the last letter on Sunday to “Trevale”.

Give my love to Joyce and Ivor, also Don and Jean, and you can pass on all the news to them, for me.72

Since I wrote to you on Sunday nothing much has happened here. We’ve been issued with a marvellous little set of things there’s a camp bed, a bucket, a bath, a chair and a wash-basin all in green canvas and pale varnished wood and all collapsible. We’ve been given a canvas hold-all and they all fold up into almost nothing and pack away in this. We’ve been told to mark them as they will be our property after the war! We’ve also got a few bedclothes, but whether the same goes for them or not I don’t know. However, they’re very useful and the bed quite comfy.

Yesterday Ginge and I went into town and shopped. At least we looked at the shops. We both bought a lipstick but that’s all. It’s a quaint little place with twisty narrow streets and dozens of little dark shops. I certainly wouldn’t like to go there without an escort—thank God we’ve got the Marines with us to look after us.

It struck me as being particularly funny to see all the Marines drinking lemonade, but they won’t touch the spirits or liqueurs over here as they say they’re bad for the stomach and I suppose they should know.

The sea here is wonderful—it’s so clear that it’s transparent and when the tide’s in you can lean over the sea wall and see the beach at the bottom of the sea and every now and then the weeds or shells at the bottom—and the colour, it’s a sort of blue-green but more green than anything. It’s really lovely!

A funny thing we noticed during the lorry ride from our port of disembarkation to here was that the cows in the fields here are not like ours they’re sort of woolly. Their coats are shaggy and sort of like teddy bears—all cuddly looking. It’s so queer, but rather nice all the same.

I have received my bank book and thanks a lot for sending it. Naturally, I haven’t used it yet, but I think they told us to bring them in order to bank the balance of pay we don’t spend. Quite honestly, there’s really nothing much to spend money on here, but I’m not banking any yet until we get paid again, as I don’t know when that will be and don’t want to put it in only to take it out later.

I’m glad that Mother received the money. I sent it the morning we left as we were not allowed to bring any English notes with us and that was all I had left besides the money I’d changed into francs and I didn’t know what to do with it. I knew I owed the victualling money which I’d promised, so just sent it all in the hopes it would reach you.

I understand that poor old England is now receiving the rocket business and wonder if Barking is getting its share of them now that the “doodle-bugs” have ceased. I do hope not, especially as Grace has gone back with the kiddies and I expect others are returning too.

Give my love to Mag and Fred if you see them, I’ll drop them a post-card today to wish them well and to let them know I’m still in the best of health and spirits.

I had a letter from Bessie the same day as I had one from you and am afraid I haven’t had time to reply yet, but will do so today if poss. She said she’d received the parcel which I sent home with odds and ends in on the day that we left, but had not yet received my bicycle. I do hope she has by now as I’m rather worried about it.

She told me that Grace had heard from Charlie saying that he’d arrived safely but she didn’t know where.

Last night by the same post as I had your letter I had one from Ron and one from Bill.73 From what I can gather Ron is now away from his Battalion and is awaiting posting somewhere. I don’t really understand what he means, but I gather that he might get a Base job or something even though he says he’s still A.1.74 Bill of course is as happy as ever, he always is, and has sent me a postcard which he captured from a Jap officer—nothing on it of course, but just a sort of Japanese scene. He as always wants another photo of me and I honestly can’t remember which one I sent him last. Can you?

I wish you could see me in my sailors’ flannels. I’m afraid they don’t go down very well with the boys, and they certainly don’t go down well with us. They’re too funny for words.

You’d laugh too at the French people here. In one part of the town—where we’re billeted—it was deserted until recently, but now the population is drifting back. You’d think they’d start to put the houses in order but not a bit of it—they collect in groups of about a dozen or so and then down on their hands and knees and start weeding the streets and the pavements! Still I suppose they know what they’re doing, and the streets certainly need weeding.

Don’t worry about me, although we have the difficulties that I’ve mentioned above, we really do look on them all as fun and help each other out and make the best of things like that. I’m still well clothed, well fed, sleep in a comfortable, clean warm bed every night and good companionship (especially bless Ginger for this). I suppose to sum up you could say we’re well and happy in spite of everything.

By the way, although I’ll do my very very best not to let there be a gap in communications between you and I, we understand we’re going to continue our gypsy-like existence in another place of residence, so it’ll be pack bags and we’re off, once more! I don’t know the details yet, but if I pop up in yet another place, don’t be surprised.

Well, I think I’d better close now as work has appeared on my desk.

God bless and keep you both. Will write again soon.

Lots of love

from Joan

xxxx

SHUTER: While in Granville a few of us got hold of a truck and went “swanning” to Mont St. Michel. It was a perfect afternoon. That lovely, unique place was unchanged—except that it was empty of tourists! Mère Poulard was still tossing her foamy omelettes—and they were still the same exorbitant price! The narrow climbing street still had its bric a brac shops. I bought some small pieces of Quimper pottery, and it was very expensive. We climbed to the monastery but here there was a change, for the guide shook us by the hand and explained that as were the first English to visit them for so many years there would be no charge! We wandered round the ramparts. The vast expanse of sand, sea and sky that surrounded us had the same inexpressible luminosity that I remembered so well. Mont St. Michel is a jewel set in mother o’ pearl. It is an exquisite thing and I was happy to find it untouched by the war.

The people of Normandy looked rosy and well. In fact, I don’t believe that materially they had been so very much troubled by the war until the Allies passed that way. Now it was impossible to get their produce into Paris, and so butter, eggs, milk, cream and cheeses were plentiful. I had a meal in a little café in Granville that was a poem! Although I felt guilty when I thought of the people of Britain with their tightened belts.

It was an unpretentious café and, in England, you would have passed it by as a “pull up for carmen” serving strong brown tea and solid meat pies. But this café in Granville gave us a meal that was a dream. There were four of us—and the company was good. The meal started with omelettes of four eggs each (but we could have had a dozen eggs each if we had wished). With the omelette there was a great plate of sliced tomato swimming in vinegar and well-seasoned, French fashion; lashings of golden Normandy butter and that delicious, slightly sour, rye bread. This was a meal in itself; but we had not started yet! The omelettes were followed by a huge pink langouste and thick, rich mayonnaise. And all the time there was good white wine and much laughter. Gâteaux: pastries covered with sliced apple in syrup followed and with them a large bowl, repeat BOWL, of whipped cream was set in front of us! We ate the pastries French fashion: dipping them into the cream, taking a bite and then piling another dollop of cream onto the pastry. And when the gâteaux were finished we ate spoonfuls of cream by itself! It was heaven! But the meal was not yet over, for now a great round Camembert cheese appeared before us and the dish of butter was replenished. And it was not some beautiful dream—it was all quite real!

After the meal we walked along the little esplanade. It was the time of the grande marée; the waves were beating against the sea-wall;75 every now and again we felt the salt spray in our faces, and we walked to the sound of the sea. It was a good evening indeed.

3.6 On the road again

SHUTER: Before the end of September—after an all too short time by the sea—we once again packed our belongings and moved forward. Our new Headquarters were to be in St. Germain-en-Laye, just to the west of Paris.76

GORDON: Everywhere we went in France we were feted by the “liberated” people, who waved to us and cheered as we went by in our lorries. When we travelled up through the towns and villages which had been part of the battle areas, around Caen where a lot of the heaviest fighting had taken place, it was very moving to see how the people climbed out of the rubble of their ruined homes to wave and cheer us.77

SHUTER: I travelled from Granville to St. Germain in a brake. It was an interesting journey as we passed through the battlefields of Normandy. The choice of routes lay between the road through Caen or the one through the Falaise gap. We plumped for Caen as we had heard terrible accounts of the damage the town had suffered.

We skirted along the Southern edge of what, I suppose, had been Caen. The road had been cleared by bulldozers. We passed between banks of rubble, twelve feet high in some places—and that was all that was left to be seen. Just rubble.

Looking back over our shoulders at the heart of the town we were relieved to see that buildings and churches were still standing. But the part of Caen that we passed through was more totally destroyed than anything I had ever seen before. Even the city of London had burnt out shells of buildings left to point reproachful fingers at the sky. Sâint-Lo had been laid in ruins, but it had been possible to trace the form of the battered buildings. But this was shapeless, utter and complete annihilation.

Fig. 3.14. Panel 30, The Struggle for Caen, Overlord Embroidery, courtesy of The D-Day Story, Portsmouth. © Portsmouth City Council.

Liberation, unfortunately, often meant total destruction and a phrase grew up. If you passed a village that showed signs of war but was repairable, you remarked drily, “Not properly liberated, that!”, or if you saw total destruction: “Um, that has been well liberated”. However, taking our drive as a whole, the scars of battle were not as great as I had expected. Once the Falaise gap had been closed our armies had moved fast, so fast that there was little destruction in their wake. 78 But Normandy (and in particular, Calvados), the ports of Brittany, and the Channel ports, had paid the price of liberation—and they paid dearly—but it was to be the price paid for nearly the whole of France.

On our journey the roads were thick with great convoys of army traffic streaming in both directions. The route was lined by notices announcing that the roads had been cleared of mines as far as the hedges. If you needed for a moment during the course of the journey to find a screen from the constant stream of traffic, you were apparently in danger of detonating a mine—no doubt with tragic results!

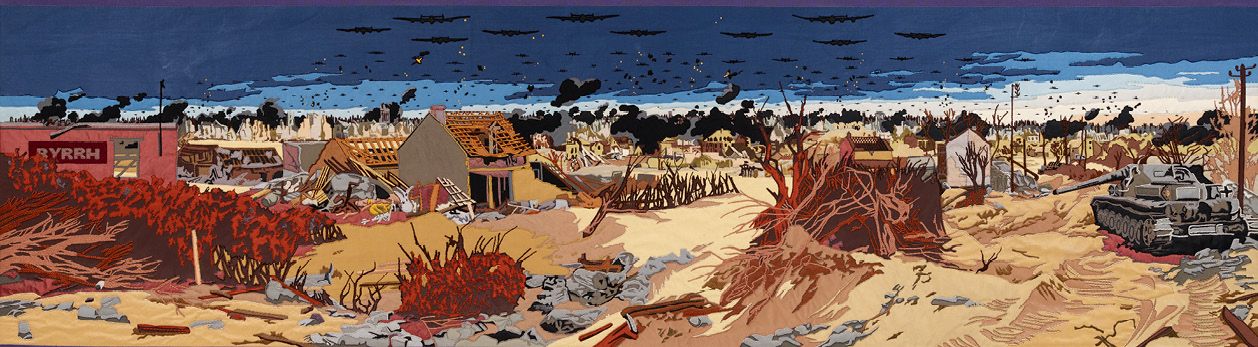

Lunch-time! The dust and the thunder of heavy vehicles were unbearable. So we decided to turn off the main road. Immediately, we were enfolded in the peace of a fresh, green countryside. We found a darling village. Not the straight, rather shabby streets that flank the main roads of France exhorting you to drink BYRRH;79 but placid houses, an inn and a church clustered round a small village green. It was more typical of England than of France.

We had wine at the inn and lunch from our American rations which were carefully done up in their camouflaged packs. The meal was delicious: chopped ham in an easy-to-open tin, delicious biscuits, chocolate, and cigarettes and matches were all included. After the meal, and remembering the mines, I decided to explore the garden. I have never laughed so much! Talk about pin-ups—every inch of the walls of the cabinet was covered with religious pictures and cut-outs of white and gold tinsel angels! I could have spent an hour, spell-bound by those fascinating walls!

The rest of the journey was uneventful but I was thrilled with the Bailey bridges that we crossed. Constructed by Sappers in a very short time they can carry the heaviest traffic. And yet they look like a child’s Meccano suddenly grown to full size.

Fig. 3.15. Postcard of the beach and promenade, Granville (sent home by Joan Prior from St Germain-en-Laye). Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

Sunday 8th October 1944

Dear Mother & Paddy,

This is one of the photos I promised you, and I’d like you to keep it for my album please. It was such a nice place I’d like to have this reminder of it. I’m keeping well and happy & will write as soon as possible a nice long letter, but I’m very busy here these days. Until then, God bless and look after you.

Lots of love

From Joan xxxx

Already, Joan Prior was making her own archive.