4. The Cutty Wren

(Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Autumn 1944)

©2024 Justin Smith, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0430.04

Saint-Germain-en-Laye is a comfortable commuter town almost twenty kilometres west of Paris at the end of the A1 Réseau Express Régional (RER) line. Its royal history and grand terrace overlooking a languid loop of the Seine and its proximity to the Forest of St Germain have earned the commune its place alongside Versailles and Fontainebleau as one of the palatial satellites of the Ile-de-France. Following the Glorious Revolution of 1688 James II lived out his exile in the Château of St Germain. The 1919 Treaty of St Germain officially brought to an end the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Between 1940 and 1944, the occupying German forces made St Germain their staff headquarters and more than 20,000 Wehrmacht soldiers and officers were located in the town. The chief attraction of St Germain-en-Laye for the Wrens of ANCXF was the possibility, shore-pass permitting, of being on the Boulevard Haussmann in less than an hour. Yet the liberated Paris, notwithstanding the superficial charms it might have revived for the tourist flâneuse, was a city on its knees. Elspeth Shuter had a keen sense of this. Joan Prior’s discoveries were in the company of Ginge Thomas; by this time, they had become inseparable.

Shuter’s post-war memoir and Prior’s letters home provide the two most distinctive voices of this chapter. Their contrasts (born of differences in social class, age, experience and rank) are above all medium-specific: Shuter’s memoir is a reflective narrative; Prior’s letters are impressionistic and quotidian. They are equally passionate in conveying the extraordinary circumstances in which they find themselves (for both narratives are self-revelations too). Yet Shuter’s privileged position is not simply the perspective of the officer-class; it is that of looking back, if only from the vantage of Henley-on-Thames in October 1945, to the recent past. Prior’s letters are located in their present moment, are constantly negotiating the home-and-away shuttle of estranged correspondents, and above all in their reportage manage to recover the commonplace from the peculiarity of their situation. It is precisely their ordinariness that is striking. Finally, they also weave a web (as most wartime letters home do) of familial (and familiar) entanglements; these are the fine threads of attachment that make the fabric of family history.

4.1 Châteaux

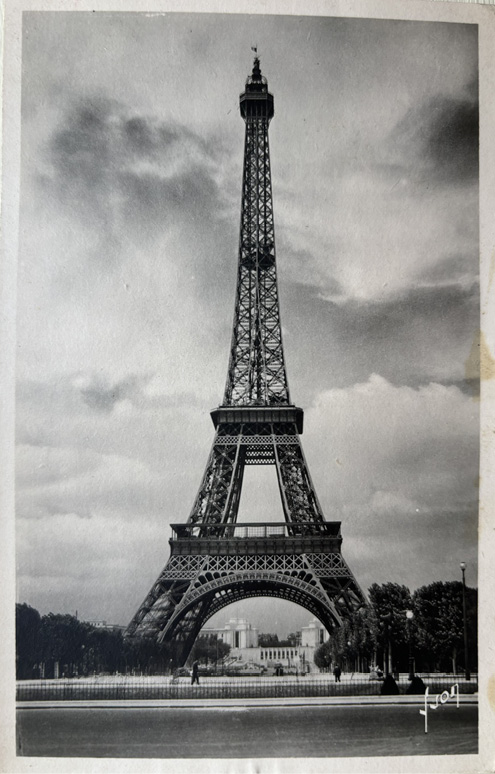

Fig. 4.1. Postcard of the Eiffel Tower, Paris. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

Wren J. H. Prior, 41801

Naval Party 1645,

c/o B.F.M.O.

9th October 1944

Yesterday I looked up at this with my own two eyes! What a thrill! Will tell you more about my visit to the gay city in my next letter to you. Incidentally, I’ve been in the middle of a letter to you for two days now & haven’t had a chance to finish it!

Lots of Love

From Joan Xxxx

Fig. 4.2. Château d’Hennemont, St Germain-en-Laye, May 1945. ‘With the British Navy in Paris. 12 and 13 May 1945, at the Headquarters of the Allied Naval Commander Expeditionary Force at St Germain-en-Laye’, Lieutenant E. A. Zimmerman, A 28586, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205159929

ELSPETH SHUTER: We arrived at St. Germain in good heart. The caravans, which formed our mobile HQ, were drawn up around a comfortable if hideous château.80 It was pseudo-medieval in the worst possible taste. It had castellations, turrets and a tower; awkwardly large French windows; and at one end a great top-heavy gable. Having been a German headquarters it was covered in a dead, muddy-green colour from top to toe. But the terrace and garden were a riot of zinnias, dahlias, asters, marigolds and those jolly little French begonias. It was nice to think that the Germans had planted them for themselves, and here were we to enjoy them!

The château was built on the top of a rise and the view from the tower was superb—undulating forest land in every direction. Sadly, we had left the real sea behind us in Normandy, but here a sea of trees lapped at the walls of the château. Trees billowing mile upon mile like the waves of a deep green ocean, on and on they rolled until lost in the blue of the distance. I decided that this was going to be a wonderful place.81

BERYL K. BLOWS: The Headquarters of the Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief Expeditionary Force was a vast château which had been the home of a Maharajah.82 Montgomery’s Headquarters were quite close; in fact, that is the reason we were there, although we could not explain this in answer to the many inquiries we had in the streets as to why the Navy was in Paris.83 We were in charge of the administration of all the Naval Parties on the Continent, and now our main job was to move the Port Parties up to Belgium.84

JEAN GORDON: By now we were of course part of “Overlord”85 though the Admiral was still Senior Naval Officer and in command of all French ports as well as the operations still going on between the UK and the French coast.86

MARGARET BOOTHROYD: The Château where we lived was at La Celle St. Cloud,87 and the one where we worked was some miles away in St. Germain, both suburbs of Paris. They had been used by the Germans and we had a wonderful time clearing all the Nazi memorabilia… pictures of Hitler, flags and pennants, making a great bonfire of them in the grounds. The large room at the Château in St. Germain was amazing. Alongside our basic teleprinters was still much of the beautiful pink and gold châteaux furniture, but we were asked not to sit on it or use the furniture.88

Elspeth Shuter had a rather different view of the contrast between their working and living châteaux:

If our Headquarters at St. Germain was hideous to look upon, so was the Wrennery a gem. About twelve miles away in the little village of La Celle St. Cloud, which hung on a hillside rising from the Seine, we lived in a renaissance château. It was of white stone and formal in design: long and low with a central doorway and the suggestion of a wing at each end. The château was only one room thick, the entrance hall leading straight through onto a broad terrace at the back. At least, the terrace was reached by two curving stone stairways and from it the view out over the sloping park land was charming. The château was in every way elegant.

The Wrens were quartered in stoutly built German huts and the Wren officers in the château itself. I shared a room with K and Barbara [Noverraz]. We had gone up in the world compared with the bare rooms of Granville! For here the walls were covered with a delightful printed linen, long velvet curtains hung at the well-proportioned windows, there were gilt and brocade chairs, built-in cupboards and a wood-burning stove. All we now needed from our camp valises were the beds, wash-basins, and our little buckets. On the back of our bedroom door was a notice signed “Adolf Hitler”! Even the toilet paper was torn-up German printed matter. It was satisfying to be so hot on the heels of the Germans and to use their printed matter thus!89

Fig. 4.3. Entrance to Le Petit Celle St Cloud, Bougival, Autumn 1944. Private papers of Mrs B. E. Buckley, HU_099999, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

‘BOBBY’ HOWES: We were billeted in two long wooden huts in the grounds of the Château. They were divided into cabins, a few individual and others holding five bunks. There was an ablution room at one end with a row of toilets and a row of washbasins with only cold water taps. Fortunately, our Quarters PO, Wren Dorothy Harvey, was able to obtain a field kitchen copper, which we could fill with cold water and heat by lighting a fire underneath. There was plenty of wood in the grounds of the Château. We had a canvas bath fitted into a wooden frame and this we set up on the floor. It was very draughty with Wrens coming to wash or visit the toilets and no privacy so we didn’t bath very often.90

SHUTER: The journey between St. Germain and La Celle St. Cloud was made, painfully, in a lorry. More stockings met their end in that lorry than I care to think about! It was a hazardous journey and we usually pitched in a heap on the floor rounding the first corner. Our insides were shaken to bits, and the clank and the rattle could be very trying. It was rather beautiful running along beside the Seine in the early—very early—morning. But the real consolation was in the waving, smiling populace. In Normandy, the people had been friendly enough when spoken to but otherwise impassive, even indifferent. Here they received us with joy. Children waved and gave the V sign. Very little ones, who knew no better, gave the Nazi salute. But after a time even this triumphal journey, done twice daily, began to pall, and so the last into the lorry was dubbed CWP—Chief Waver to the Populace—for each journey.91

BOOTHROYD: It was a fantastic time for us all, the French people were so glad we were there and nothing was too much for us. Whenever we walked through the gates of La Celle St. Cloud, people were waiting to greet us and invite us to their homes. We have many happy memories of different French families and were able to hear their trials in the war.

We were regularly issued with cigarettes, chocolate and biscuits. Usually we ate the chocolate and biscuits then gave the cigarettes to our French friends. Two families named Nordling and Bochley were very kind to us and invited us to their homes. We spent much time wandering around the Palace of Versailles, which I think was free to us, and we enjoyed so much of Paris.92

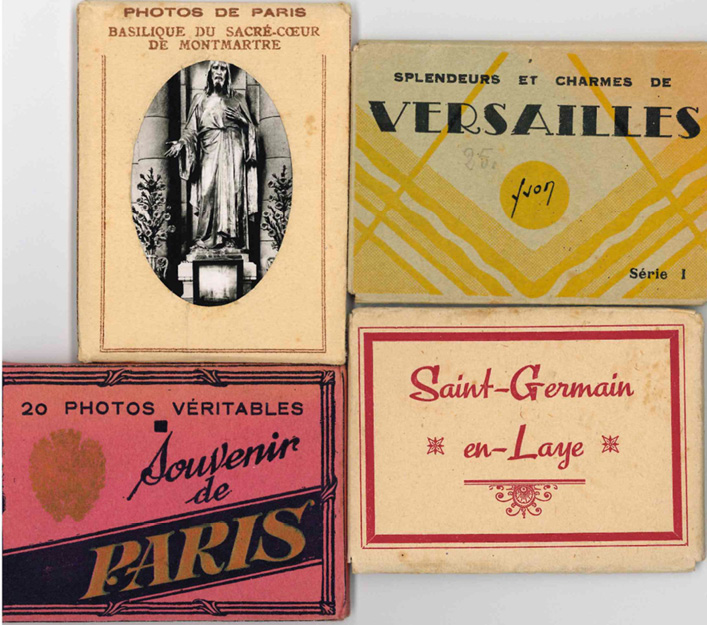

Fig. 4.4. Montage of souvenir photo packs (90x70mm). Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

Tuesday 17th October 1944

Dear Mother and Paddy,

Here I am again, snatching a few moments to say hallo and how are you once more.

Since last I wrote to you I’ve been to Paris on an “organised tour” sounds good doesn’t it? Well, it was good. We went almost everywhere in such a short space of time I must try to tell you all about it.

We visited some of the places which I visited on my unorganised tour so I won’t bother you with that and of course a good deal of it I can’t tell you because it consisted of views. That is to say we stood high up and saw the whole city from various angles.

One thing which did impress me though was that we went through Montmartre right up to the highest point in Paris which is L’Eglise de Sacre Coeur which being translated is the church of the Sacred Heart. It’s the loveliest church I’ve ever seen and I’ll try to go there again. I can’t hope to describe it so I bought some photographs which I’m enclosing although even they don’t do justice to it. Each altar is of marble inlaid with gold and other precious stones in various colours and they have to be seen to be believed.

Another place we visited was Notre Dame which is very lovely indeed. I’m hoping to go to a service there some day but I doubt whether I shall get there.

I’m afraid we couldn’t wander about at will and so did not have an opportunity to shop, but my goodness the shops did look exciting and marvellous. If at all possible Ginge and I will try to shop there, but there again these things are doubtful. We had tea at the NAAFI which is an enormous hotel and is very comfortable indeed.

To-morrow afternoon Ginge and I have the afternoon off but haven’t yet decided what we’ll do. We thought it might be a good idea to have a photograph taken as several of the boys have had theirs done in a nearby town93 and they’ve turned out rather good. However, we’ll see to-morrow.

On Sunday we had the afternoon off but it poured with rain—literally streamed down and I went and curled up with a book by the wireless in our rest room. It’s a lovely old room built as an extension to our mess. It was built of course by the Germans who were here before us and I must say it’s most attractive. All round the walls are low backed seats fixed to the walls like an old settle you know, wooden and carved, and above are very stiff compressed cardboard panels which a budding German painter has made use of. Each panel depicts a German dancer or musician in Tyrolean costume or some other such native dress and they’re very attractive. The fireplace is an enormous wide-chimneyed affair brick built and very cosy and we burn logs—great logs which stretch right up the chimney—on it.

I don’t think I have any more news at the moment, so will cease for a while and finish this before I go back to Quarters tonight.94

Want this to catch the post now, so will write when I reach the office again.

Lots of love

From

Joan

Xxxx

Elspeth Shuter did not share Joan Prior’s enthusiasm for Germanic décor, despite their improved circumstances:

Our standard of living had also risen at St. Germain. The interior was as excruciatingly bad as the outside had promised. It was a jumble of neo-Gothic carving hanging like fretwork; great baronial fireplaces; draperies of cloth of gold; great chandeliers; tiled bathrooms and a sweeping marble stairway—but it was comfortable. We had solid German desks to work at, cupboards whose fronts went up and down like a roll-top desk, and there was a profusion of deep armchairs. The Germans evidently believed in solidity and they had done themselves well!

I had a desk in the Staff Office.95 Other members of the staff shared another big office known as “Operations”.96 But their room was painted grey and faced north, while ours had gay yellow brocade walls and the sun and light streamed in all day. There were tall double windows and a balcony on two sides of the room. Our chums, who lived on the cold grey side of the building, used to drop in for a gossip or to get warmed through by the sun. Out of deference to “Operations” we called ourselves the 2nd XI and we were a happy team. Quite a lot of schoolboy fun used to flash round the office on a bright morning. There was the pilot who, despite a merciless running commentary from the rest of us, held long conversations in French with Monsieur le Directeur des Phares.97 Then there was Ducky, an American colleague, who was a great joy.98 He always got his signals about two hours after we did. Several of us would discuss and dispose of a hot piece of news and then, when it was all forgotten, Ducky would get the same signal. After a few minutes he would start to read the same thing out to us as hot news! Then we would gently tell him that it had all been disposed of hours before. “Oh,” he would say, “How did you know? The signal has only just come in!” Bless you, Ducky!

Ducky was certainly a personality and, therefore, an asset to the office. For one thing, he got American sweet rations, which were lavish compared with ours—and he shared them generously! He used an electric razor and as it would not work in his sleeping quarters he used to shave in the office! How visitors’ eyes used to pop out of their heads when they heard the burr, burr, and saw Ducky absorbed in his task. He would finish off his toilet by chasing the odd bristles that had been missed by the razor with a pair of eyebrow tweezers! To do this he twisted his face into the most amazing contortions.

I became quite air-minded while in the 2nd XI as our team also included a Coastal Forces liaison officer who incidentally, during the occupation had flown low over Paris dropping a tricoleur on the Arc de Triomphe.99 He had a great welcome whenever he went into Paris. The Parisians had been very touched by that act. Then there was V who kept us well informed on all the latest lavatorial gossip!100 (Note: Lavatorial gossip is navy slang for the latest, official or unconfirmed, news).

Soon after we arrived at St. Germain one of the male members of the 2nd XI was exploring our room: opening cupboards and peeping in. He turned a door handle, it opened, and he found himself in the middle of an immense and slippery white tiled floor. Then he heard a voice say that it wouldn’t be long. Looking wildly round he saw to his horror that a head was peeping at him from over the edge of a bath at the far end of the room. He was in the Wren officers’ bathroom!

Our palatial bathroom was a great joy to us. But it was a preposterous room really—so vast—and the many long mirrors were heated so that they never misted over! The bath was the deepest I have ever seen which was quite lucky if we were going to have unexpected visitors. Owing to the tiling everywhere, voices echoed and carried from the bathroom into the 2nd XI. We overheard many amusing conversations, but the funniest of all was the chorus that would rise to a crescendo when a number of people got back from an afternoon in Paris:

“Oh my dear! How marvellous! Not Chanel No.5? But how simply MARVELLOUS!”

“We went absolutely everywhere; we saw absolutely everything […] It was simply marvellous!”

“It was wonderful; it was marvellous. No, I can’t explain, it was just marvellous!”

“What? Oh no! we didn’t go inside, but it was simply marvellous all the same.”

“It was a marvellous view, I can’t describe it. But it was just marvellous!”

“Oh my dear! Really? How simply marvellous!”

COS—the Chief of Staff101—overheard a conversation like this one day when in the 2nd XI. He was very tickled and later teased the offenders with an extremely good imitation, and “Oh my dear! How simply marvellous!” became a byword.102

4.2 Paris

We were so fortunate for we could go into Paris from 1300 to 2100 if we got a pass. The shops were lovely, at least to our eyes. We were particularly interested in those beautiful shops which sold wonderful perfumes: Elizabeth Arden, Chanel etc, etc, all lovely to see. We were told the American soldiers had bought up Chanel No.5 when they arrived. It was always a sore point with the English lads that the Americans had so much to spend.103

‘GINGE’ THOMAS: I remember going into Paris on the metro quite often, we would visit Galeries Lafayette and other wonderful places. I loved the Sacre Coeur and went there very often.104

GORDON: Paris, though over-populated with the influx of the Allied forces, seemed comparatively empty as there were so few civilian vehicles about. Instead of taxis there were little covered carts pulled by bicycles and some chic ladies drove themselves in very pretty horse-drawn equipages with basket-work carriages. They bowled along to the Bois de Boulogne and sat outside the few cafes and restaurants left open to them.

I and Jeanne Law attended a fashion show by Paquin. As it was a cold day we were wearing our duffel coats and, in our uniforms, caused more stir than the models, who themselves came over to examine our apparel. A few days later duffel coats, smartened up and “feminised” (ours were strictly Naval) were in the shops in Paris.105

SHUTER: I shall never forget my own first afternoon in Paris. It was late September; the air was crisp, but a warm sun shone out of a vivid sky. The trees in the boulevards were tossing off their leaves—gold and red. The beauty of Paris struck me afresh—what a spaciously planned city! It was clean, sparkling, almost dazzling that September afternoon. Undamaged by war, it was en fête. Flags added to the gaiety: not stuck out of windows willy-nilly as in England, but elegantly draped or fluttering, each one place with careful thought and in perfect taste. They glowed richly against the cool coloured buildings. In fact the whole city, dappled as it was in bright sunlight, seemed to be shouting for joy. It was infectious, soon we too were shouting for joy.

Yes, Paris was delirious with colour. The swirling leaves; the fluttering flags; the streets filled with gaily painted bicycles: blue, yellow, red and green. And the brightly coloured clothes of the women! Vanished was the Parisian dressed quietly, if beautifully, in black. The gendarmes blew their whistles and bicycle bells chorused. The city gave us a warm, gay smile of welcome.

Oh! The fun of it all. The joyousness of Paris in her liberation is common knowledge now. But at the time it burst upon us without warning. We were enchanted. We were intoxicated!

Impossible ever to forget the defiant spirit of those bicycles! They were fitted with bright-coloured saddle bags and decorative dress guards. The girls cycled in gay, full-pleated skirts many of them tartan; these they coyly arranged over the back of the saddle before mounting. Some of the bicycles had little trucks on pneumatic wheels hitched on behind. I thought of the English effort—a shopping basket on a small, badly-running wheel which you push along with a walking-stick handle. How difficult we make things for ourselves in England!

Then the taxis! A bicycle with a side-car looking like a perambulator with a brightly-coloured hood. The “fare” sat in the baby carriage and the taxi drive peddled, charging more to go up the Champs Elysées than he did to go downhill! But the most ingenious thing was a glimpse I had of a man and a woman sitting side by side in what I thought to be a very small motor car. But on looking again, showing under the running board were two pairs of feet solemnly peddling round and round.

And the women’s hats! They were monstrous. They stood about eighteen inches high, or so it seemed: richly-coloured turbans or narrow top-hat shapes. Of course, veils, feathers and flowers were in profusion. Sometimes a whole bird, wings outstretched, rested on the brim! We were told that throughout the Occupation the Germans had slavishly copied the Paris fashions, and so these hats had been devised to pull their legs.

Earrings were equally exotic. Made of sequins, feathers, glass, semi-precious stones, or starched lace, they swung almost to the shoulders. Gloves and shoes were also gay—in face, whatever their suffering, the women of Paris had determined that the Germans should know nothing about it.

The shop windows were as beautiful as ever and full of luxuries: hand-painted crèpe-de-chine scarves; sumptuous leather handbags; silk undies and silk stockings. But they were an impossible price. Cosmetics and parfum were the real joy to us. They were in all their pre-war glory and not expensive when we first arrive in Paris. But prices were to rise to unattainable heights later.

That afternoon Barbara and I raced madly from shop to shop greeting and being greeted. There was much shaking of hands. To many people, we were the first British women to be seen in Paris as the city was in the US sector. The people seemed genuinely delighted to see us. We got presents of lipsticks, fountain pens and propelling pencils! K and another Wren officer were embraced by one old lady. The tears were streaming down her face as she kissed them on both cheeks murmuring “Mes belles Libératrices; mes belles Libératrices!”

What a never-to-be-forgotten afternoon! We returned to St. Germain exhausted with excitement, but with a warm glow round our hearts. It had been touching to be given such a great and genuine welcome. Yes, my dear, it really was simply marvellous! Yes, it really was.

Later we were to learn that the Paris we saw that happy afternoon was but a brave façade which hid hunger, hardship and poverty. The shop windows were bright with luxuries, but essentials were unobtainable. There was no guarantee that Parisians would get their allowance of rationed foodstuffs. There was no security. Inside, the big shops were in semi-gloom owing to the shortage of electricity and, if you went to the hairdresser, you couldn’t get your hair dried as the power did not come on until the evening—after the shop had closed! Yes, the gay city we had seen was actually deep in suffering.

All the same, the French had no real conception of Britain’s war effort—or of the work that our women were doing. They asked us why we were in the Navy. We explained proudly that we were volunteers but added that even if we had not been we should have been conscripted into something else by then. We described how British housewives were working part-time in factories and running a home as well. They shook their heads in disbelief. We insisted; they looked incredulous. They were unable to visualise such complete mobilisation. Our country was working in a way that was beyond their comprehension. Later in the autumn, Mr Churchill made a statement in the House of Commons quoting figures which showed just what our women had been doing. Several times after that I was stopped in the street and asked questions by French people and congratulated on Britain’s war effort. They were certainly envious of us but, above all, deeply grateful. Never once did I come across resentment because in 1940 we had been lucky enough to be saved by a narrow strip of water. It was always gratitude, overwhelming gratitude to us for keeping up the fight in those dark and bitter days. I liked the French for this, it would have been easy enough for a proud people to feel jealousy and resentment.

4.3 Entente Cordiale

SHUTER: Soon after our arrival, our marines played a football match against St. Germain. The town did the honours royally, and after the game did they have tea and buns? Oh no, the teams were floated in champagne! I couldn’t help a chuckle as, at that time, we had only been able to get vin ordinaire for the officers’ mess! The Mayor explained with great relish the history of that champagne. A French collaborator had delivered a large consignment to the Germans. Then the Germans had fled hastily before they had had time to drink the wine, but they had paid for it. So, the Mayor confiscated the champagne and the money, and the collaborator was thrown into prison. Thus the town got the champagne free, and the collaborator lost his money and his freedom!

This football match was a great event as a number of our staff (including Wren officers in their berets—fit to melt the heart of any Frenchman!) went down to watch. One perplexed little Frenchman, talking to a senior naval officer, remarked, “But you English are so funny; now why do you take the trouble to put your mistresses into uniform?!”

At least that was the story when it reached me. I seized on it as an important clue, for it threw some light on to the “Mystery of the Charwomen”. French women, who had worked in the château for the Germans, also did the cleaning for us. On going into the office each morning, we had at first been greeted with: “Bonjour Madame!” Then, after a few days, when they knew we all went back to La Celle St. Cloud each night, the morning’s greeting changed to: “Bonjour Mademoiselle!” When I questioned one of the chars about this she laughingly explained that in France when someone of my age was unmarried, she was called “Madame” out of courtesy. That is as may be; but why switch back to Mademoiselle after a few days? I am sure I did not grow visibly younger under the influence of good French wine! At least, not with quite such rapidity.106

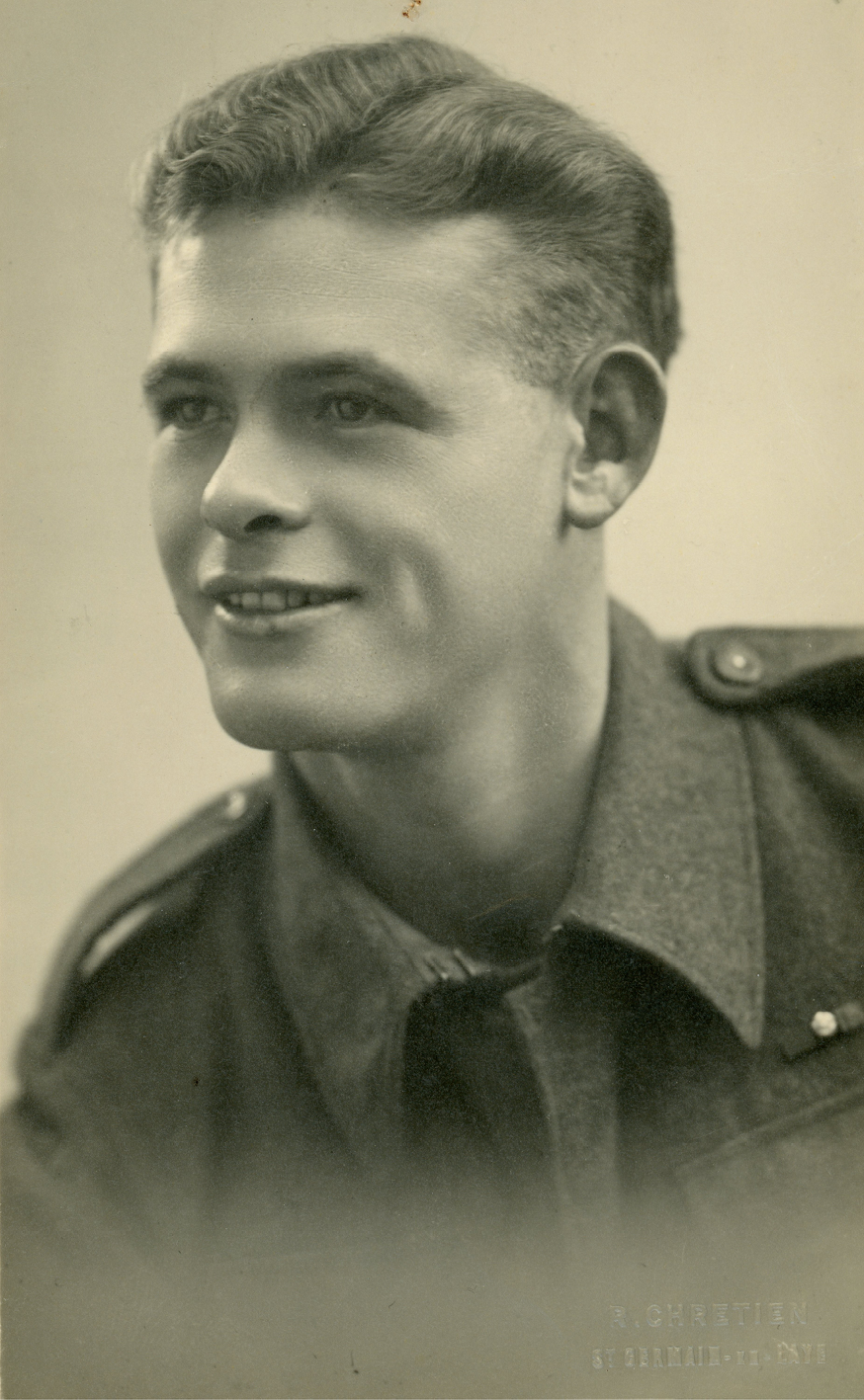

Fig. 4.5. George Mellor, RM (studio portrait, St Germain-en-Laye, 1944). Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

Friday 20th October 1944

Dear Mother and Paddy,

I have just received your letter dated 17th October and thanks a lot for same. I hope you will excuse this typing but I’m in such a hurry that I won’t bother to correct any mistakes that may arise.

First and foremost I ought to explain the “rush” about life these days. As I believe I told you, one of the girls who works individually for an officer is sick and I’m doing her work. Well, I’m afraid it keeps me busy all day every day and I just don’t get a minute to type a letter to you in the office, and as you know I haven’t a fountain pen so writing outside office hours is tricky. However, I keep trying to get five minutes and this is one time when I’ve succeeded.

I’ll answer your letter first and then talk about me.

I see you are at Mag’s again and am glad in a way as she does make you so welcome doesn’t she.107 I’ll address this to Aunt Lucy’s as I see you’re returning there on 23rd and by the time this gets home you’ll be back.108 I expect you do want to get back home how and I should think with the winter coming on Somerset—or at least Burtle—isn’t very attractive as there are no trees to speak of and you miss all the lovely tints which make Autumn in the country so worthwhile. I hope Mother is looking as fit and well as when I saw her last—she did look so much better and not so thin either. When you get to Barking, Mumsy, you mustn’t get ill and thin again—even if you have to take Cod Liver Oil and Malt to keep you plump! And above all try not to worry too much about me—believe me they watch us with an eagle eye to see everything’s O.K. You might not credit it, but since we’ve been out here we’ve all had another medical exam, although we had one before we came, just to make sure and I’m O.K. still. The food is as good as ever and if anything I’m putting on weight, although I wouldn’t swear to that as I’ve no means of testing my weight here—praise be.

Last Saturday, Ginge and I had the afternoon off and we went into a nearby town109 and had our photographs taken, seaman’s jerseys and all!!! I must tell you all about it. We went into the shop (one of the boys named George110 had had his taken and had shown us and it looked so nice we thought we’d go to the same place) and a man came out and we exchanged pleasantries and then tried to tell him we wanted our photos taken. We couldn’t seem to make him get the gist of it, however, so Ginge pointed to one of the many photographs on the walls and then pointed to us (here I must tell you that she’d indicated a very attractive young girl photographed in a scanty swim-suit) whereupon he broke into a broad smile said that he understood and he was so pleased and all the rest of it and told us to go to No.46 Rue […] (the name of a street). We came out and looked at each other and of course began to roar with laughter. However, we decided to try it and walked along (almost in fear and trembling) and to our relief found on entering that it was a very nice studio. A woman came forward and we explained what we wanted and discovered that we couldn’t order less than 6 postcards (artful creatures). That was O.K. but then she said that it would come to 180 francs each, that is 18 shillings which would be 3/- per postcard. Now George told us that his had only cost 150 francs, so I asked her if that was the cheapest she could make it and she said it was. Then, I had a bright idea and went through the photographs she had of people who’d already had them done and found George. I pointed to him and said “150”. She laughed then and asked if he was a friend and I said he was so she said that we could have ours done for 150 too! It just shows you, you just can’t trust them at all. Two or three times I’ve had similar experiences and by arguing and refusing to pay I’ve got things cheaper.

I don’t think 15/- is at all bad for 6 postcards as he took a great deal of trouble over them and although I don’t know what they’ll turn out like I’ve seen other people’s and they’ve been good. We’ve to call for them on 26th October so now we can hardly wait.

Well, after that, we went to the local sports stadium and watched the Marines play football against the Naval and Marine officers. The Marines won 2—0 but who wouldn’t with Ginge and I to cheer them on!

On Thursday (that’s yesterday) we worked all day as per usual and in the evening we had a dance at Quarters. We had a very mixed crowd—Sailors, Marines, Soldiers and Airmen—and it was very good fun indeed. Quite informal and amusing but good fun.

To-night I’m late duty and to-morrow I think I’m going to a social, but haven’t quite made up my mind yet whether the laundry can wait another night.

Well that’s about all the recent news of me and my doings. Have had a letter from Bessie by the way, she writes often to me.

In my last letter I was so rushed for time that I didn’t tell you much about the organised tour we made of Paris. In fact I can’t remember now quite what I did tell you. I know I sent you some photos of the Church of the Sacred Heart, but I can’t remember what else I told you. I’ll mention one or two things now so if I’ve told you before, please forgive.

Oh, Duty calls, so I must leave this for a moment.

Back again, for a bit. Now, I was going to tell you more about Paris wasn’t I, well I think if I want this to catch to-night’s post I’d better postpone it for another letter and get this one off minus.

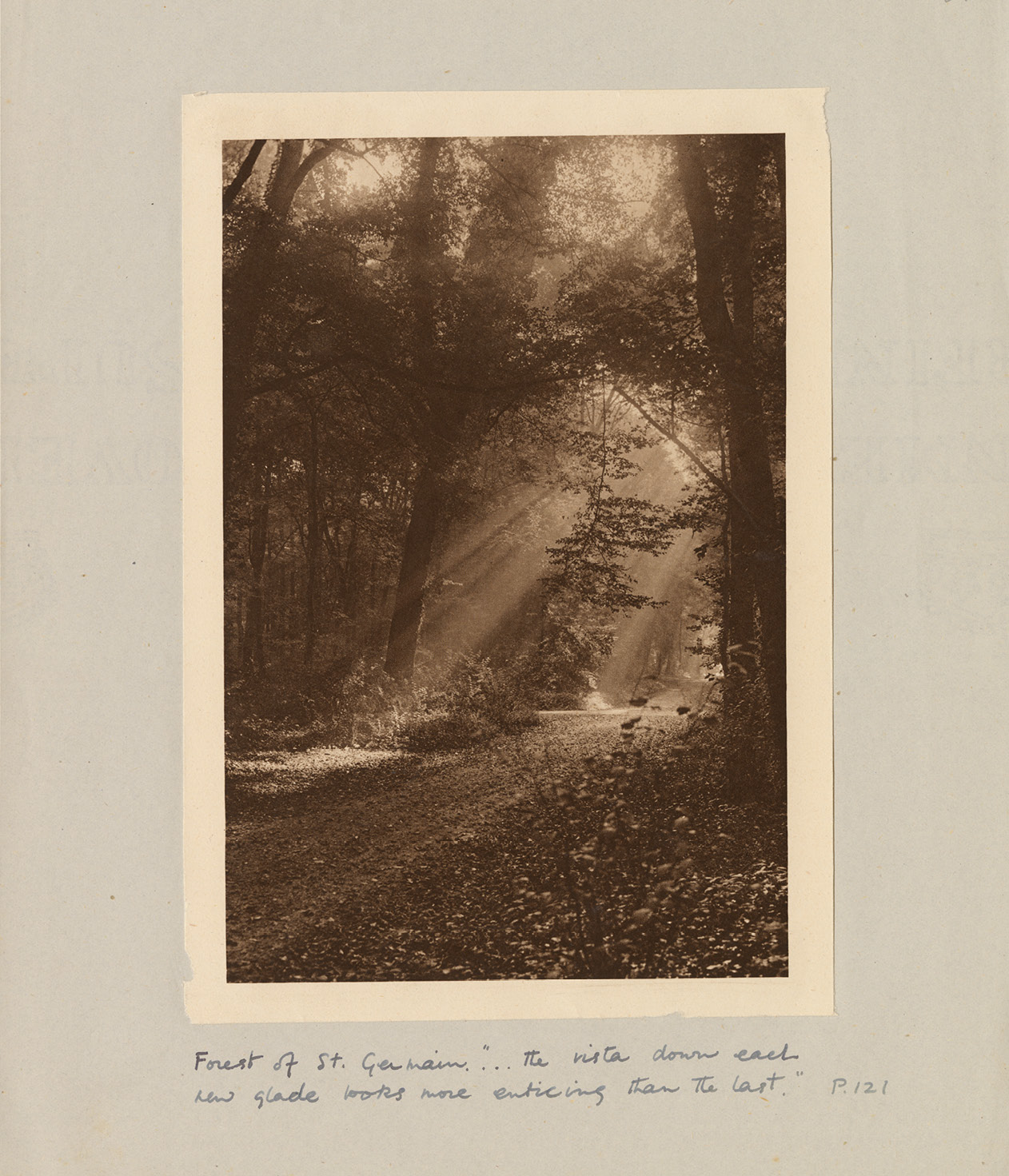

The trees here now are lovely, I do wish you could see them. Ginge and I went for a walk in the woods in the grounds of the Château where we work, in the lunch hour to-day and it was amazing. We particularly noticed that at one time we looked down and were walking on a carpet of fallen leaves—coloured rusty brown. The next time we noticed them they’d changed completely and were yellow and gold. Then we looked a bit further on they were red and pink and later on still they were green! It just depends on the type of tree you see, what colour the leaves are when they fall, but it will give you some idea of the wonderful colours the countryside here is wearing. I’ve never seen anything like it in England, indeed I haven’t. Everywhere there are trees, in every street on every corner and I love them so.

Well, will say Bye-bye for now. If I get time will write to-morrow. Until then, God Bless, take care and keep smiling.

Lots of love

Joan xxxx

SHUTER: The French were warmly hospitable and invitations poured in. But there still seemed to be some doubt as to what Wrens really were. Our Quarters Officer had an invitation for some Wrens to go out to tea. The hostess had a little girl, nine years old, so she asked if she could entertain girls of about the same age—it would be such company for her little daughter!

K and I made some delightful friends. A professor of English and his wife. They lived in exquisite apartments in the Hôtel Vendôme. It had been the house of the Duc de Vendôme at the time, I believe, when James II lived in the palace at St. Germain. At their home we were able to enjoy real music for the first time in years. They had friends who played the piano, the violin and the violoncello, and one lad was a clever composer. We spent delightful evenings in their company. Monsieur and Madame were Anglophiles. Madame told me with pride how she had never looked a German in the face throughout the Occupation. Winston Churchill was their hero because in their darkest hour in 1940 when no Frenchman had yet come forward to lead France, it had been Mr Churchill who had spoken to them and offered France so much. For the same reason the Americans were less popular than the British because, from the French point of view, the Americans had failed them, the world, and the cause for freedom by not entering the war when France was stricken down. We had long and interesting talks and often found that we were taking the French or American side against the Anglophiles. They described how they had listened to and clung to “Ici Londres” throughout the years of occupation; how they had picked up the reports of the Normandy landings from English broadcasts and how the news had been passed from house to house; people weeping and laughing in their joy. We were bombarded with questions about England. Were the buses still painted red in London? Was London badly damaged? Were we short of food and clothes? Madame was delighted when I took her some coffee, she clutched a cake of soap to her bosom, but she almost wept when I took her half a pound of tea. They were delightful friends, but they were filled with despair over the state of their country, failing to see how it would ever rise again. “France,” they said, “lay stunned. If only they had a strong government like us. If only they had a Churchill!” I found that I loved the French that I met. They were stimulating company and quick to see humour in the same things that we do. I felt tinglingly alive when I was with them.

4.4 Social life

SHUTER: Early in October we had a house-warming at La Celle St. Cloud. The whole of the officers’ mess was asked—and nearly everyone came! So we were over a hundred all told. Just before the party began the light in the bar-room failed. Hastily we collected together some candles and the atmosphere of the party was enhanced. It really was rather a lovely sight. A snow-white cloth on the table (one of Sister’s sheets!), and a row of candles down each side. The cask of wine, mellow in the candlelight. The gentle flames reflected a thousand time in the rows of glasses. The stewards in white flitting to and fro, their faces illuminated, then lost again in shadow.

We had a lovely big room for parties and this evening it was riotous with flowers. A log fire burned in the great open hearth. Our staff never needed entertaining, things always went with a bang from the start. In lots of ways I enjoyed that party more than any other, maybe partly because it was the first to which the staff came in full force. It was so nice to have all our friends gathered together and to see them shedding their gravity and soon looking happy and carefree—and it was all done on a cask of vin ordinaire! We called it giggle-juice; it certainly provoked much happy laughter and no ill effects. That night the consumption averaged out at two pints a head! We danced, we laughed, we played oranges and lemons, and we were happy.111

GORDON: Paris, into which we could travel (free on the Metro) in our spare time, was entirely taken over by the Allies and many of their restaurants and hotels made into clubs and recreational areas for the mass of servicemen and women now arriving. We were not allowed to eat their food, of which indeed there was very little, but of course wine was easily available, and those Wrens who were not used to it, which was most of us, and who went out with the Americans, who were also unused to wine and mixed it freely with the spirits they could get from their PX stores, often came back to quarters very much the worse from drink.112

SHUTER: I got the urge to see the night-life of Paris out of my system early on. I enjoyed it; it was a new experience. But once I had tasted of it and the novelty had worn off, I never wanted to go again.

We went to the Casino de Paris when it re-opened for the first time after the liberation. We had a box on the edge of the stage which was quite an experience in itself. The audience was almost entirely French and I enjoyed it all very much. Later, I went to the Folies Bergères and this time the audience was almost entirely American. The compere spoke in English as well as in French. I should love to go behind the footlights in that theatre and see the stage machinery. I have never before seen such wonderful scene changing. The stage effects were colossal, and when the performers were dressed at all they wore the most sumptuous costumes—spreading crinolines; costumes of ostrich feathers and of flowers; silks, brocades and velvet. We certainly had not seen such things in England for a long time—if ever. But despite all this I did not enjoy that evening. In the undress parts the GI’s cat-called and whistled. They shouted: “Go on, kiss her!” and “Get on with it, kid!”, until I felt wretchedly, miserably, uncomfortably naked myself.

Despite the lavish productions the theatres were unheated and, when the curtain was lowered, the whole auditorium was lit by one huge blatant bulb hanging from the middle of the ceiling. The girls of the Folies Bergères struck one night demanding heating or more clothes. Of course they got the heating. A country seems ill indeed, or gravely in need of help, when it allows the production of expensive materials and fantastic luxuries if, at the same time, its people are starving to death and dying of cold. Poor France!

Another night we danced at the Lido. The atmosphere was good: it was gay—and French. The cabaret was excellent. The funny men were funny; the tableaux and dancing girls quite beautiful. Some of the tableaux were deliciously nude and in perfect taste. I could sit and enjoy them as an art student enjoys a good life model.113 They gave me real aesthetic pleasure—and there were no cat-calls! But I went another time to a night-club in Montmartre. I enjoyed the evening because I was with delightful people. But the cabaret was the most sordid and distressing affair I have ever seen. The girls wore little bits of tinsel or sequins so arranged that they looked most consciously naked. Much more so than if they had had absolutely nothing on at all. They were flat-chested or grossly pendulous; thin and scraggy, or fat and flabby. They were pathetic. All had faces of stone, fixed in a stretched smile, or just dead. One had an appendix scar and another the long mark of a caesarean. No glamour about that cabaret. Poor dears, I wanted to wrap them up in nice warm blankets and send them home. Once again we had penetrated beyond the dazzling shop window and had glimpsed the inner despair, the utter wretchedness and misery of the city. After that, I never again dabbled in the night-life of Paris.114

Wednesday 25th October 1944

Dear Mother and Paddy,

Once more it seems ages since I last wrote and I honestly haven’t had a spare second. I’m trying desperately to write this now and will get what I can written before I’m sent for to get on with to-day’s effort.

By the way, I’ve just finished a letter to Bess, and have told her the news up to last Sunday. As she says you are going home shortly I’ve asked her to let you see that letter and I’ll continue this one from here and she can read it.115 I didn’t want to have to send a joint letter if I could help it, but I’m afraid until Kay116 comes back to take over her job again I’ll have to do it that way.

There, you see, it’s now the 27th! But good news at last, Kay has come back to-day and for the first time in ages I can really settle down and have a good old chat to you.

Well, last Monday we were Duty and Ginge and I had a couple of hours off in the afternoon and we went into the nearest town to look round the shops. My dear people are so helpful in the shops here, they don’t mind how much bother they go to and they don’t seem to mind when you don’t buy anything, unlike the shop assistants at home. Anyway we ended up by Ginge buying some cough sweets at a chemists. In the first place we didn’t know how to ask for same and I knew the French for sweet so we said that and then coughed. We stood in front of the poor little proprietor and coughed pitifully—we even began to feel sorry for ourselves—until in desperation he brought forth a box of cough lozenges and gave them to us! He wouldn’t let us pay, wouldn’t hear of it as we had such bad coughs!

On Tuesday I was lucky enough once more to be able to visit Paris and took the opportunity of doing some Christmas shopping. Honestly once you’ve shopped there, London is just dull. The shops themselves are beautifully built and inside the art of display achieves perfection. In one enormous store there is a ground floor and then the other floors are built up in tiers, sort of gallery fashion so that from them you can look right down through the middle of the building to the ground floor.117 And the wonderful lighting and fittings. In the Beauty Department there they had miniature counters for every well known brand of cosmetic with the name written over the top so that if you always used Coty beauty preparations you just went there and every Coty product was there.

Elizabeth Arden have a simply wonderful Beauty Salon—it’s really worth going there just to see it. The floor is carpeted in rich purple relieved with flowers in pastel shades of pink, green and blue, and the walls are cream and silver. The curtains are sheer and flesh coloured and all the fitments mirrored so that they reflect the light.

Coty too have a lovely shop in the Rue de la Paix as also have Richard Rudnut—this’ll please Bessie because she needn’t hunt for same any more. In the same street Mappin and Webb have a shop and also Alfred Dunhill. I bought, too, some Christmas Cards which though out of the ordinary I hope will be O.K. I didn’t really think I’d send any, but Xmas isn’t Xmas really unless you do, so I’ve changed my mind and hope that these I’ve got will do.

I wish that you Mother and Bessie and Grace could see the shops with me. They’re honestly like something I’ve never seen before. I don’t know why either, that’s what puzzles me. Except perhaps it’s just that they’re Parisian. The various little glass cases and windows will sometimes be a mist of cobwebby tulle with a hat or a powder compact or a pair of exquisite gloves in the centre of it. And you never see a powder bowl or compact or purse or handbag on its own. There’s always a wonderful swansdown power puff tied with satin ribbon or a silk handkerchief or scarf with it. The packings too for things like powder and perfume are such as you never see at home. Even an ordinary box seems to have something different and exclusive about it.

One thing I notice over here is that they’re not in the least short of paper for wrapping, or paper bags. In one shop I went in I bought three different quite small things and had a separate bag for each! They’re quite strong thick paper too. And lovely tinselly string from tying up parcels, or thick corded silk in some shops.

On Wednesday I stayed in and coped with dhobeying and washed me too!

On Thursday (that’s yesterday) I went with several of the girls from the office to an R.A.F. Social. It was the second one I’d been to and was very enjoyable. They had music and singing and games and a spelling bee and a quiz and all sorts of things like that and in fact in was an extremely pleasant evening with a very nice crowd of boys.

Oh, another event yesterday! Ginge and I went into town in the afternoon and collected our photographs! Personally I don’t think either of them is good. They both look rather posed and artificial especially about the mouth they looked awfully made up for us. Still I’m enclosing one for what it’s worth and hope that perhaps later on I’ll have another done in collar and tie this time and that it’ll be better.

Oh, and another thing I meant to tell you was that Ginge and I went into a shop the other day which sold umbrellas and leather wallets and bags and that sort of thing because Ginge wanted to get Kenn a wallet.118 While we were waiting to be served a lady was buying an umbrella and she spoke to us and said that she was English and had been caught over here when war broke out and had been a civil prisoner or something. Anyhow she gave us her address and told us to go round for tea whenever we liked. We haven’t been there yet, but must go one day because she seemed so pleased to see us and I expect wants all the latest news about the old Country. She herself came from Sussex.

Yesterday as we were coming back to the office we met a man on a bicycle who stopped and presented us with some grapes! They were delicious and it was so unexpected.

I think that about covers the news up to date and thank goodness I’ve caught up with myself at last.

Will write again soon, and this is a promise, but until then, God bless and look after yourselves won’t you.

Lots of love

From Joan xxxx

P.S. What d’you think I can get for Stan & you Paddy for Xmas? Awful shortage of things for men here.

Fig. 4.6. Joan Prior (studio portrait, St Germain-en-Laye, October 1944). Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

SHUTER: Sometimes in the afternoon I had the most lovely walks with my chums in the forests that surrounded us. It was grand to swing along at a good pace, often in silence, with beauty on every side. French forests are so wonderfully well looked after. Broad paths lead for miles and miles between beautiful well-grown trees. At intervals these paths are intersected by others. At each of these “étoiles”, for so they are called, you are torn by indecision as the vista down each new glade looks more enticing than the last! Those walks, the first real exercise for months, are one of my happiest memories.

Fig. 4.7. Forest of St Germain, Autumn 1944. Private papers of Miss E. Shuter, Documents.13454_000041, courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, London.

In November, Barbara left the staff for good.119 Her going left a horrid gap in our life, especially in our dorm. Never again did K and I have quite so much laughter at night, nor sit on our beds quite so helpless with mirth. Barbara was a very vital person and her high spirits had been infectious. We missed her greatly.

But by now the French wine had imbued everyone with the festive spirit. Wine is surely the keynote to the difference of temperament between our two nations! There was a positive orgy of parties. Once a week we had a guest night with a band and dancing. I looked forward to Bomps-a-daisy which was the signal for jackets off and enjoy yourselves!

If a party ever looked as if it might be a bit sticky to begin with then “One-O” (as we affectionately called our unit officer) and I always met together beforehand.120 Then into action we went, advancing from a whisky base! There was the time that a General from SHAEF was the guest of honour. I was sitting next to him and in trying to entertain him I told him of the stupendous spectacle to be seen down in the valley. The Germans had made a very good job of blowing up a railway viaduct. Enthusiastically I described it, for to me, viewed disinterestedly, it had great aesthetic value. The permanent way looked like a great, gleaming serpent writhing in its death agony as it lay slithering away into the bottom of the abyss. The General stared at me for a moment, then turned and talked to his other neighbour for the rest of the meal. Afterwards, I was told that he considered railway communications in France to be his biggest headache! However, I felt that even Generals should not allow their appreciation of the aesthetic to become blunted by work. I was to meet him again several months afterwards. We were introduced. He looked hard at me and said, “We have met before, I think.” “Yes Sir, we have,” I replied, rather amused.

Then CNAO121—Chum John to me—organised a banquet in honour of the French Admiralty. The guests included six women of the Service Féminin de la Flotte. It was the greatest fun, that party. We ate, we drank, we had toasts, we danced and we sang French rounds well on into the night. Next day, Chum John had a letter of thanks from a darling little French Admiral who had been the guest of honour. In his letter he said that he had found the Wrens altogether “séduisantes”. We rushed for a dictionary and found: séduisant = tempting, fascinating, charming, seductive. Good enough we thought!122

THOMAS: We had a wonderful time in France […] and were treated like lords and ladies—wonderful food, wonderful entertainment in the camps. We were invited by the French to lots of functions, and sometimes dinner would take about three hours because the food would come in about seven different courses.123

SHUTER: Later the French Admiralty asked us to a party. Plate after plate of the most delicious paté, sausage and such like appeared before us. I decided that with the acute food shortage in Paris we were being given a cold supper. But I was uneasy. I had been caught once before, so I asked my neighbour for a menu. The worst had happened! I was completely full and we had only just finished the “hors d’oeuvres variés”. Uniform, with its tight waistband, is not ideal for a banquet. There was nothing for it but to unzip the top of my skirt! This caused much merriment, so I assured my neighbours that it was an English custom for showing appreciation of a meal!

One of the happiest parties was one given by COS in the Admiral’s château.124 This house had a lovely sweeping stairway. Irresistibly, I slid down the baronial bannisters! When half way down, I realised that the rest of the party was still at the top of the stairs and roaring with laughter. A skirt is not ideal for bannister-sliding. However, there seemed nothing for it but to go on, gripping the banisters tightly and hoping for the best. I was nearly blistered by friction. What we do for England! Yes, our parties were great fun.

Fig. 4.8. Postcard of the Château St-Léger, Admiral Ramsay’s private residence. Private papers of Joan Halverson Smith.

Friday 3rd November 1944

Dear Mother and Paddy,

Once more I’m on the air again saying that I’m fine and well and happy.

I do hope all is O.K. with you, and was very pleased to receive your letter written on 24th October.

With regard to Ron’s Xmas present, it’s very difficult to get things for men out here. I could get a pipe and a pen, but outside of these two things there doesn’t seem anything obtainable that he hasn’t already got. Anyway, next week on my afternoon off I’ll shop and see what I can do, although I think it’s a bit late now for Xmas presents really.

I’ve managed to get most of the presents for the women of the family, but men are such a problem here. I say, that sounds bad, I mean gifts for men are tricky.

Since last I wrote nothing momentous really happened until yesterday when Ginge and I had our hair permed! I expect you’re all surprised, but really mine had grown to the state where it was on my collar, (which is not admired by the powers that be) and the odd ends underneath were as straight as Nature intended the whole thing to be. Ginge also had masses more than the Service said was good for her, so we hied us into Paris and then the fun started.

We were ushered upstairs into a lovely salon where there were about a dozen chairs and a wonderful view out onto the street below. You honestly do things the comfy way in France because we sat down in these leather easy chairs which were on a swivel so that you could turn around and look in a mirror or alternatively at the rest of the room, or again out into the street. That was the first novelty. The next was that our hats and coats and parcels were removed to a cloakroom and we were made comfortable by a charming French girl. We were then received by M’sieur who spoke excellent English and who produced an enormous pair of scissors and began snipping. He announced that to suit my face my hair had to be ‘built up’ so not knowing quite what to expect I said “Have it your own way, chum” or words to that effect, closed my eyes and prayed hard. In due course we were both shorn to his satisfaction and then our hair was fixed in rubber grips and then curled as per usual and then (more then than that about this paragraph) he popped on a sort of little clipper thing and Bob’s y’r uncle. Suddenly off went an alarm and the whole thing was over. I had hardly realised that this was ‘it’. There’s no machine or being strung up to gadgets about it at all! It’s really amazing. What also amazed me was that we hadn’t yet had our hair washed and so I asked him about this and he said they never washed it before a perm because the hair then retained its natural grease and oil and so the perm was never harmful to the hair. I thought it a good idea. In case we got a little heated while this was going on, however, they gave us a pretty little fan to use—so sweet, and so French! The next thing, of course, was having the hair washed. This again, was unlike anything I’ve ever known before. We sat before a wash-basin, but with our back to the basin with the neck resting comfortably on a fixture and the head well back. It was then washed all the water etc. ran down a metal chute away to the back. It’s a marvellous idea because you don’t get your face or neck wet in the least and are reclining comfortably all the time. After this we had a friction. This is a head and scalp massage with perfume—I smell of it yet! Then the hair is set with pins and the waves pushed in but no combs used and under the dryer you go. During this part of the proceedings the electricity failed (this is always happening over here) and for about five minutes we sat in the dark just waiting, then on it came again and all was well. When it was dry, my dears, instead of taking the pins out by hand they just waved a little gadget over the top of your head and it had a magnetic tip and all the pins flew out of your hair and stuck to the end of it! We were more than amused and were in fits. At the end of all this, the hair was brushed with a dear little brush, till it shone and then combed and set. Well, ‘s’all I can say about that, except that my hair and Ginge’s looks all the better for it and most everyone likes it. We are thinking of having our photo taken again so if we do you’ll see how you like it (or not!).

The night before we had a dance at our Quarters sort of Hallowe’en and the hall was beautifully decorated. We had big cut-out bats suspended from the lights and large black spiders (not real, of course) and masses of lovely autumn-tinted leaves, some from a creeper outside being especially lovely—pale yellow and pink turning a lovely warm clear red. This looked lovely, but I think it looks even lovelier as it grows spilling over an old grey stone wall. I must say everyone went to a great deal of trouble to make the decorations apt even going so far as to hollow out a pumpkin and make eyes and nose and teeth! Proper Hallowe’en it was!

I’m now continuing this on 5th November—Guy Fawkes’ Day and I’m determined to celebrate it even if it only means striking a couple of matches and holding them till they burn out! Yesterday afternoon I went into the small town nearby and armed with a shopping list I tried to do the errands for several people in the office. My goodness, what a day! I went to a photographer’s to collect photos of one of the Marines here, and a wedding group was in process of being taken and of all things they wanted me to be in the group! Of course, I refused but had a nasty moment at first. However, I collected the photographs and all’s well that ends well. This afternoon, I’m going to watch a football match and if anything exciting happens at that will let you know in my next mailbag.

I think that about ends news of me for the moment, so will hie me back to answering your letter.

Fred certainly has had a good apple crop this year, and I for one could just eat one now.

Now that you have gone back to town I shall expect you, Mother, to maintain the good progress you have made, so don’t let me hear to the contrary. I know you wouldn’t tell me, but don’t let me hear from any source! You must take care, not wear yourself out, and above all don’t worry.

I have not yet received Charlie’s address from Bessie, but have now received a letter from him, so it’s O.K. I have replied to him and sent him a photograph incidentally. I’m sorry he’s been drafted out there—it must be deadly and he must be very worried about Grace too.125

Guess that’s about all now, all my love and God bless you all. My love to Bess and Stan and I’ll write them again later. Please all take care of yourselves and don’t worry about me as I really am well and happy.

Lots of love from

Joan xxxx

4.5 Operation Infatuate

SHUTER: During October many of the staff had been busy with the plans for the assault on Walcheren. The Army was already approaching the island from the direction of South Beveland which lies to the east. Two assault forces had been built up and trained in the Portsmouth command. One consisted of LCA and minor support craft; these were to ferry the army across the Scheldt for the assault on Flushing. The other force, which was mounted at Ostend, consisted of LCI(S), LCT and major support craft. Their job was to land the troops at Westkapelle on the extreme western tip of the island. This was to be a hazardous undertaking as the western end of the island, guarding the mouth of the Scheldt, was one of the most heavily fortified stretches of coast in all Europe—in all the world. The landing was to be supported by the RAF and by naval bombardment from HM ships Warspite, Erebus and Roberts.

Three weeks before the assault the RAF successfully breached the dyke in the vicinity of Westkapelle. The sea swept in through the gap flooding the hinterland. It was opposite this gap in the dyke wall that the Army was to be landed. Conditions of heavy mud caused by the flooding were anticipated so amphibious vehicles were to be used wherever possible. Unfortunately, it was also necessary to take some tracked vehicles.

A few days before the operation was due to be launched, Admiral Ramsay and his Staff Officer Plans set off in the caravans of our mobile headquarters. They were to join up with the Army headquarters—Canadians—who were responsible for the Army side of the plan.

Once again the weather was against us. The visibility promised to be so bad that the RAF could not guarantee their support. However, despite this, and having weighed up the pros and cons, the Army decided to “go”.

The landings in the Flushing area went well and with few casualties in the initial stages. But the assault on Westkapelle was a different story. It was to be an epic of cold-blooded courage.

On the morning of the assault the RAF was grounded by the weather conditions over the airfields although, ironically, visibility in the assault areas was fair. Oh, the cruelty of it! If only those aircraft had been able to get into the air. The result was that some of the heavier targets had not been neutralised by air bombardment before the craft went in. But even this was not all. The bombarding ships were also shorn of their accuracy as their spotting fighter planes were also unable to reach the target area.

Thus it was that at 0900 on 1 November 1944, those gallant little support craft, their guns inadequate to neutralise the heavier shore batteries, tackled the searing fire of this strongly defended area quite alone. Flak, rockets, shells were hurled at the enemy. They went in firing and continued to fire until their own guns were silenced or until their crews were killed or wounded.

The two LCG(M) beached themselves and engaged the enemy at close range until they could fire no more. It was a deadly duel between the 17-pounder guns of the craft and the 4” and 6” shore batteries that they were so valiantly engaging. One LCG(M) was sunk as she lay beached. The other, its guns silenced, retracted, but sank soon after.

Under cover of the supporting fire the troop and vehicle carrying craft slipped in and beached in the gap. The soldiers and their equipment went ashore. Owing to the mud great difficulty was experienced in getting the tracked vehicles through the breach and onto the dyke wall. The amphibians did better. But slowly, very slowly, the craft were called forward for unloading. It was a situation calling for the utmost degree of self-control and courage. A few more, then a few more. The rest waiting while all hell was let loose around them.

The support craft, maimed and bleeding, kept at it throughout the forenoon—Lilliputians attacking giants—their guns striking terror into the hearts of the men manning the shore batteries. Blindly, instinctively, the Germans kept firing at the craft that were attacking them. Had they directed their fire at the other craft quietly and steadily landing our troops we should probably not have made the day. As it was, after a fierce and deadly battle, our army established itself. The RAF were able to get into the air in the afternoon and new heart was put into our men.

At 1230, after three and a half hours of gruelling fire, our beloved little craft, their job done—and well done as never before—withdrew and those that were still afloat limped back to Ostend. I suppose the support squadron would have been surprised if they had known that a Wren officer in the middle of France was yearning over them like a mother. My heart was filled with pride, but oh, it was sore indeed. To me it seemed that no courage could have been greater than that of the soldiers and sailors of Westkapelle.

After a few days of hard and bitter fighting, Walcheren was ours. The Scheldt could now be swept and soon the great port of Antwerp would be humming.126

4.6 Armistice Day

BOOTHROYD: The day Mr Churchill and General de Gaulle visited the Arc de Triomphe, Laura and I left St. Germain after morning watch and went to Paris. We had heard they were coming and thousands of people were there. We did not intend to get caught up in the crowds but were swept along without choice. Thankfully we managed to stay together and managed to get a good view of both men laying wreaths at the tomb of the Unknown Warrior—a day to remember.127

SHUTER: Mr Winston Churchill was to visit Paris on 11 November 1944. He was to drive up the Champs Elysées to the Arc de Triomphe for the service to be held at the tomb of the Unknown Warrior, and afterwards to return to the saluting base for the march past of Allied troops.

I was determined to be there among the French crowd so that I could watch their reactions when they realised that Churchill, who meant so much to them, had come over to be with them on such a day. For it was a great day to them—their first free anniversary of 11 November since 1939.

I begged a lift in a jeep and the four or us took up our stand on the Champs Elysées about half way between the Arc de Triomphe and the saluting base. The security measures were amazing—at least, amazing to me born and bred in the orderliness of England. American army police in their white helmets were standing, a few yards apart, on the roofs of all the buildings lining the route—a row of snowdrops outlined against the sky! The French crowd was excited: they knew Général de Gaulle was to be there—more they did not know.

A roar of cheering sounded in the distance. It swelled and rippled up the Champs Elysées. It still wanted a few minutes to eleven o’clock. They were coming! Big cars roared past.

“Vive de Gaulle!”, the crowd shouted.

Then they caught sight of Mr Churchill as the cars flashed by.

“Church-eell! Church-eell! Monsieur Church-eell is here! Vive Church-eell!”. They shouted; they cheered; they stamped; they screamed the good news at each other; they laughed; they wept. A little lady in front of me, a black spotted veil over her face and smelling strongly of garlic, turned and, clutching hold of my hands, asked if it really was Mr Churchill who had passed. I said it was. We all shook hands excitedly. With a flourish the other Wren officer (who was shorter than I) was given a stool to stand on! Oh, it would have been worthwhile to travel a thousand miles to share their pleasure.

Then, a sudden hush swept over the crowd; we were rooted where we stood—the two minutes’ silence.

Now cheering started again. This time at the top of the Champs Elysées. “They are coming!”, the crowd cried. And, down the middle of the avenue, walking slowly, came Général de Gaulle and Mr Churchill. The crowd waved and shouted, clapped their hands and stamped again with delight. “Vive de Gaulle! Vive Church-eell! Vive Church-eell!” And Mr Churchill gazed around him at the crowd, which was now half-mad with joy, and he looked very happy. I was more than delighted with the reception. It was colossal!

The march past was very fine. Madame de Garlic and I exchanged the names of the French contingents for those of the British and American. With bands playing they came—tramp, tramp—in a never-ending stream. The Garde Républicain; the Royal Navy; Général Koenig, the liberator of Paris, at the head of his men. What an ovation for him! The RAF, who meant so much to the French. They had a great reception. The British Army, the American Army, French sailors, British sailors and Americans—all were represented. On and on they came. The Chasseurs Alpins, marching with a quick running step; North African troops, a rich note of colour; the Gardes Mobiles, fine sombre men. To the skirl of a pipe band, with kilts swinging, came the Canadian Scottish. The crowd was delirious with excitement. Général Leclerc’s men; more clapping, more cheering. What a pageantry of colour, and bands playing from top to bottom of the Champs Elysees—and still more came.

Pleased with our morning, we slipped away. But I was determined to go into Paris again in the evening to see how the city was celebrating after more than four years of German occupation.

The Arc de Triomphe was flood-lit for a few hours. What cared they about the black-out on such a night? Wanting to see the reactions of the ordinary citizen we went to a little café in the Place Blanc.

What fun it was! A small band with violins, accordion and drums was playing, and everyone was laughing, eating and drinking. We too ordered drinks. People were asking the band to play special things, so Peggy wrote something on a slip of paper, signed it “Une Matelotte Anglaise!” and passed it up. There seemed to be some discussion. The band crowded together, read the note, talked, argued and looked in our direction. Suddenly Peggy gasped. She had remembered that her composer was now considered to have been a collaborateur! We quite expected to be run out of the café. The band shook their heads—but they smiled. Perhaps it was alright after all. Then, with a roll of drums, they stood up and solemnly played “God Save the King”. The talk died on people’s lips. There was silence. Everyone stood up. We went on standing for a long time as the band had now broken into the “Star Spangled Banner”. Then followed “La Marseillaise” and the Belgian national anthem.

After that we were toasted. Drinks appeared mysteriously on our table and everyone seemed very happy. Then a tough looking Frenchman came in. We took one look and christened him Monsieur le Black Marketeer. He threw money around—drinks everywhere! Then he saw us and in a loud voice ordered the band to play our national anthem. We all screamed that we had just had it. But he was not to be put off and we all stood up again while the national anthems were played through a second time! More drinks all round. What an evening! What an entente cordiale! The evening had surpassed all expectations. I wonder why I am so happy in a French atmosphere?128

Saturday 11th November 1944

Dear Mother and Paddy,

Here I am once more, dears, more or less continuing the letter I’ve just finished to Bessie and Stan.

However, I’ll stop my news and answer your latest letter first. First and foremost, thanks a lot for keeping the mail coming, not only you, but Bessie as well—it is so nice to hear such a lot and to know that you’re both O.K. in these worrying days at home.

I’m glad you had a comfy journey up from the country129 and wish I could have had tea with you when you returned! What a lot we should have had to chat about. I’ve been thinking it might be an idea to keep my letters so that I could explain things which sometimes have to be obscure owing to the demands of the censor—but it’s up to you really. If you don’t fancy doing so, don’t bother.130

I too wish I could see Mother now, as she’s looking so well. I’ll never forget how well she looked on my last leave. Now you must keep it up, Mother and not take any backward steps! I expect you both feel glad to be back at home though especially now that the winter’s coming on. Now that you’ve come home I must drop a card to all the Somerset folk occasionally just to let them know everything’s O.K.

I think that’s about all in answer to your letter so you now continue with my news.

On Friday, Ginge and I were late duty and we had time off in the afternoon from 1 till 5 o’clock. We had lunch and then walked down to the nearest town and had our photographs taken.

My dears, the funniest things happen here. We were crossing the market place and suddenly an old woman shot across the road and rush up to Ginge and seized both her hands and said to us “Are you English?” (all this in French of course). We said we were, whereupon she seized me round the neck and covered me with kisses and kept saying “Thank you very much for liberating us” as if we’d done it personally! She then repeated the same procedure with Ginge and still keeping hold of our hands enthusiastically chattered on in French about how much she liked the British. We tore ourselves away eventually, our faces crimson and disappeared as fast as we could—it was all most embarrassing!

Then, not long afterwards, an old man passed and said “You take care, you catch cold”. We didn’t quite understand this, as although it was a cold day we were well wrapped up, so we said “Pardon” and he repeated the same phrase, so we said “Oui” and went on. The only thing we could conclude was that it was his only phrase in English or something! Everything happens to us!

To-day, being Armistice Day, there are celebrations all over the country on a large scale. In this same nearby town,131 there was a parade in which our Marines took part, so this morning Ginge and I set out to watch same. We walked into the park and followed the crowd. There were dozens of people walking very determinedly in one direction so we went too. We arrived at the spot in time for the “Marseillaise” and then suddenly everyone began to run.

It really was the most extraordinary business! They were all running in the same direction—from whence we’d just come, incidentally—and there were boys and girls, young men and young women, grey haired old ladies—all tearing along at a terrific rate. Old men—one in particular just in front of us had a dog which snapped at people’s ankles as they overtook him—even one old man in a bath chair was wheeling himself along. Well, we thought, must be something doing so we joined in. This all took place in the park so it was something like a glorified cross-country run, over lawns, through masses of leaves, in between trees, people threading their way in and out with amazing rapidity—just as if every Saturday morning they always did this! Boys in coloured uniforms—the equivalent of our Boy Scouts I should think—charged along carrying long wooden poles—I tell you, it was fantastic. However, nothing daunted we panted along. I did think once that we might hitch a lift from the old chap in the bath chair, but decided after a moment’s thought that I could out-run him. Well, we ended up where we’d come in, in front of a lovely old château, where the crowds were beginning to line the roads. We had a camera with us and Ginge was going to take a snap of the boys as they came along if she could, so we didn’t want to get too far back. Knowing us, or should I say me, we managed to get in front and stay there! Everyone was wearing Red, White and Blue ribbons and badges and pictures of General de Gaulle and General Leclerc and goodness know what. People swarmed round, climbed railings and trees and in fact wormed their way everywhere—it was too amazing for words. At last along came a contingent of what I should imagine was the equivalent of our Chelsea Pensioners. They were resplendent in silver helmets (looked quite like firemen really) and shuffled along followed by a French band. As the latter speaks for itself I won’t comment on it. Then came the American military band headed by the most ridiculous drum-major I’ve ever seen. Rhythm wasn’t the word! If he’d had a scarf instead of a mace he might have been doing the rumba! The Yankees marched at their usual casual rate, and then—came the Royal Marines in blues! Our boys from the camp. They easily outshone any of the others there and Ginge and I went out in front of the crowd and Ginge took two shots of them. Whether the snaps will come out or not we don’t know as they were moving all the time. Still, we’re hoping. Then came matelots in blues and then more Marines in khaki. After that we more or less joined on the end of the parade so that we’d get through the gates without having to push through the crowd, and when they were all lined up outside we took another snap. We then came back to the office where I’m now typing this.

By the way, we’ve discovered a little shop in the town where we can buy an Overseas Edition of the Daily Mail. It’s only one sheet and there’s not overmuch news but at least it’s in English!

Well, now I’m afraid it’s Sunday—just like that. I posted the letter to Bess yesterday so perhaps they won’t both arrive together after all. To-day there’s the heaviest frost ever. Everything is white and it does look really lovely. I wish you could see the countryside here—I think we must surely be in one of the loveliest parts of France for it’s so beautiful.

I was glancing through a Picture Post this morning which P.O. has sent to him from home, and there’s a long account of cider making in Somerset in it. I read it all and could just imagine Fred and Ivor collecting the apples and making the cider!

This afternoon I’m again going to cheer for our team in a Football Match against the French—turning into a regular football fan these days, but at least it’s good clean fun.

By the way, did you get the little packet of photographs which I sent home to you? They showed views of the Basilique de Sacre Coeur. I don’t remember you acknowledging them and so I wonder if you got them or if they went astray in the post, although they shouldn’t have done so as all our mail is censored here before going through Post Office channels.

Even though we’re half-way through November there are still roses blooming in the gardens of the Château! I think it’s incredible. Still for the past two mornings we’ve had heavy white frosts, so I don’t suppose any of the flowers will last much longer. It’s such a pity because the dahlias were still looking wonderful. There don’t seem to be many chrysanthemums in the gardens around here although there are quite a few in the florists.

By the way, have I told you about our horse? I don’t seem to remember telling you, so here goes. Ginge and I do for a “constitutional” every lunch hour. Helps walk down our lunch, and provides us with amusement. In a field near our place of work is a dear little red horse with a white blaze on his nose and we talk to him every day. When we come along now he runs to the railings and pushes his head through and muzzles in our hands. He’s so sweet and knows us very well now.

Am rapidly coming to the “must eat” stage now and so will close and dash to lunch. It’s usually chicken on Sunday, so I’m hoping. Take care of yourselves and God Bless you both.

All my love, From,

Joan xxxx

Fig. 4.9. Photograph taken by Phyllis ‘Ginge’ Thomas of Royal Marines parading through St Germain-en-Laye, Armistice Day 1944. ‘Ginge and I went out in front of the crowd and Ginge took two shots of them. Whether the snaps will come out or not we don’t know as they were moving all the time’. Private papers of

Joan Halverson Smith.

4.7 Landing craft