Epilogue: Keeping Mum

©2024 Justin Smith, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0430.07

Into the closed mouth the fly does not get (epigraph in Joan Prior’s 1945 diary).

I’m sorry for the modern spy, she has a lousy deal,

The modern general’s very often lacking in appeal. (FISH)105

I come to her in white, and cry Mum; she cries Budget, and by that we know one another. (The Merry Wives of Windsor, 1623, v. ii. 6)

It has been the aim of this book to do two things. The first task was to gather archival sources, supported by secondary literature, in order to contextualise the cache of letters, photographs and documents left by my mother, to produce a narrative of the experiences of the Wrens of ANCXF, as far as possible, in their own words. The purpose of this enterprise was both to pay tribute to the substantial role of the WRNS in Operation Overlord and beyond, and to recount those events from a female perspective as a history of women’s war work.

The second task was more elusive and personal. This is also family history. And it is inseparable from the nature of the letter as historical evidence. The letter is not merely subjective; it is also performative, mercurial and ephemeral. It hides as much as it reveals. It is duplicitous. It is partisan. It is provocative. It is affective. I became fascinated by the epistolary performance of the young woman who would, much later, become my mother, in the act of becoming herself. Of making herself up. And I was intrigued by the nature of her relationship with Ginge and how she (re)presented Ginge, an orphan, to her family at home: my grandparents, aunts and uncles, who are themselves sometimes cast in pantomime roles. Ginge is an invention; never Phyllis. Ginge might almost be a codename in a racy wartime thriller by Johnny Mills.

Much has been made, in recent histories, of the secret war—the importance of code-breaking, espionage, underground resistance, propaganda, bluff and double-bluff. This intelligence war has had tremendous mileage, from Fleming’s Bond and Le Carre’s Smiley to the rehabilitation of Alan Turing, the derring-do of double-agent Garbo and a host of factual and fictional accounts of women working undercover. Practically, of course, this offers the opportunity to explore war dramatically through stories of individual bravery, heroism and ingenuity. The female sub-genre has proved particularly fertile, though its sexual politics invariably tread a dubious line between a progressive celebration of strength, courage and personal sacrifice and the salaciousness of sex as a weapon of subterfuge, portraying women as preternaturally devious—both qualities making them ideal spies. Not for nothing is the monumental tribute to the British SOE (Special Operations Executive) on the Albert Embankment, a bust of Violette Szabo. As Juliette Pattinson reminds us, its inscription ends with the words: ‘in the pages of history their names are Carved with Pride’ invoking the 1958 feature film made from R. J. Minney’s biography of Szabo.106 But, with no disrespect, this is the glamorous face of secrecy. I’m interested in its more prosaic form.

Just as there is a moral and philosophical distinction between causing death and not saving a life, so there is a difference between keeping a secret and not divulging knowledge. The former is fixated on the activity of protecting particular information from disclosure. The latter is a matter of disposition, which requires little attention to the differential value of knowledge. In fact, this demeanour is disinterested in the secret itself. In the era when the cause of freedom of information is locked in mortal combat with the ethics of personal data protection, the notion that there are things that are better left unsaid is quaint indeed. Yet that sense of profound propriety—the sanctity of the unspoken—made it relatively easy, in wartime, to ‘keep mum’. Self-censorship became second nature. War was just like sex: it was everywhere, but you didn’t talk about it. But, of course, keeping mum did not mean keeping quiet. It became the practised art of speaking freely yet saying nothing of significance. In this, my mother was a past master. It was a technique of self-presentation and evasion that she learnt as a wartime correspondent.

The use of the phrase in wartime propaganda caused controversy even at the time.107 First, in the series of Careless Talk Costs Lives campaign, was ‘Be Like Dad, Keep Mum’, which enraged the Labour MP Dr Edith Summerskill in 1940. She raised the matter in the House, cross-examining Duff Cooper of the Ministry of Information:

Dr. Summerskill asked the Minister of Information whether he is aware that the poster bearing the words “Be like Dad, Keep Mum,” is offensive to women, and is a source of irritation to housewives, whose work in the home if paid for at current rates would make a substantial addition to the family income; and whether he will have this poster withdrawn from the hoardings?

Mr. Cooper: I am indeed sorry if words that were intended to amuse should have succeeded in irritating. I cannot, however, believe the irritation is very profound or widely spread.

Dr. Summerskill: Is the Right Hon. Gentleman aware that this poster is not amusing but is in the worst Victorian music-hall taste and is a reflection on his whole Department?

Mr. Cooper: I always thought that Victorian music-halls were then at their best.

Dr. Summerskill: Is the Right Hon. Gentleman aware that if he goes to modern music-halls, he will find that this kind of joke is not indulged in and that this suggests that he is a little out of date for the work he is doing?108

Then, there followed in 1942, ‘Keep mum—she’s not so dumb!’, attributed to artist Gerald Lacoste. An attractive reclining blonde female is featured at the centre of a social circle of officers from each branch of the Armed Forces. According to The National Archives, the ‘image [was] intended for officers’ messes and other places where the commissioned ranks met. At the end of May, Advertiser’s Weekly noted that “sex appeal” had been introduced in the form of a beautiful spy, who they insisted on “christening Olga Polovsky after the famous song”’.109

The campaign was intended to issue a pejorative warning that ‘when in the company of a beautiful woman, remember that beauty may conceal brains’.110 But the implication was far more crude: a man might reasonably assume that most attractive women are dumb blondes, but some might actually be treacherous spies. At best, while you may be able to trust your fellow officers to be discreet, you can’t trust a woman to keep a secret.

If my mother did not give much away about her wartime service, she didn’t throw much away either. She was a hoarder. And for that I am grateful. Thanks, mum, for keeping so much.

Fig. 7.1. ‘Keep Mum she’s not so dumb’, MOI Careless Talk Costs Lives campaign poster, 1942, INF 3/229, courtesy of The National Archives, London. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3454442.

Mum’s the word. It is a Middle English word. It appears in Langland’s Piers Plowman. Its etymology suggests a connection with mumming and miming. From whence, mummers’ plays and pantomime (from the Italian commedia dell’arte) or dumbshow. Gestures without words.

The tradition of mummers’ entertainments does have words, but the dialogue and dramaturgy are of a very simple form. Each of the archetypal characters self-presents to the audience; their entrances and exits are not motivated by narrative but each character introduces the next. Their main dramatic engagements are comic-violent tableaux. The victim of each staged fight is restored to life by the magical ministrations of a doctor. Thus, the central theme, as far as it goes, may be said to be death and resurrection. But the adversaries are pantomime goodies and baddies, St George representing England and his assailants stereotypical infidels (the Turkish Knight) and traditional enemies (the Noble (French) Captain). In some versions, these warring historical characters are framed by their unlikely ‘parents’, Father and Mother Christmas. Each duel fought is preceded with the dictum: ‘a loven’ couple do agree/To fight the battle manfully’.

As the Isle of Wight antiquarian William Henry Long noted, in his introduction to that island’s own version of the Christmas Play, ‘Father and Mother Christmas appear in old great coats, the latter wearing an old bonnet and skirt. They walk in bending, and as if decrepit through age, with the backs of their coats well stuffed with straw. This is necessary, as during the performance they furiously belabour each other, Father Christmas wielding a cudgel, and Mother Christmas a formidable broom’.111 Thus the defence of the realm enacted by St George’s sword is parodied as conjugal strife in the manner of Punch and Judy: an international conflict played out as domestic violence.

Thomas Pettitt’s research into the ‘pre-history of the English mummers’ plays’ suggests that:

The overwhelming majority of the folk-drama performances recorded and described in the last couple of centuries—the mummers’ plays—are winter-season calendar customs (All Souls, Christmas, New Year, Easter) involving perambulations of the community by small groups of local men, who, disguised or costumed, entertain the households they visit with an in part semi-dramatic show, in return for which they receive largesse in the form of refreshment or money, the latter sometimes devoted to financing a feast for the mummers and their associates on a separate occasion. Within a typology of auspices, therefore, the mummers’ plays belong alongside other seasonal house-visit begging customs (quêtes) such as Souling, Thomassing, Clementing, Pace-egging, and the like, from which they are distinguished by the semi-dramatic elaboration of the show offered to the households visited.112

As such, these events may be considered to represent both an affirmation of the Rabelaisian spirit of misrule, Mikhail Bakhtin’s carnivalesque, and their paradox—the recuperation of the social order.

There is a stage in the battle with dementia when the forces of present consciousness finally give up the fight and begin the long, slow retreat into memory. Joan’s father, Harry Prior, reinhabited his younger self. His first staging post was one of the succession of tobacconist’s shops they had run at Chadwell Heath, after he took early retirement from the brewery. He sat in his tartan dressing-gown with a blanket over his knees; the family—Grace Prior, Bess and Stan, Joan and Ron—gathered around his chair in the geriatric ward of the hospital. ‘Well,’ he’d say at last, ‘It’s no good me standing here talking, time’s getting on. I’d better go and lock up the shop’.

‘But Dad,’ they’d say gently, ‘You’re not in the shop now’.

‘What are you talking about?! I lock up every night. D’you think I don’t know where I am?!’ he would retort, indignantly.

At last his regression took him back to childhood. His schoolboy days. Suddenly, he burst into tears. ‘Dad, what on Earth’s the matter?’ Sobbing inconsolably, eventually he’d say, through quivering lips, ‘That boy stole my cap and he won’t give it back!’.

My mother wasn’t temporarily transported like her father. Her last articulated memories remained just that, recollections of her past. But she recalled the same scene from adolescence over and over again, as if returning to something unresolved. It was the day in Cardiff when she visited the City Hall with Aunt Lucy and, later, got caught with Peggy in a downpour in Roath Park. Something about a group of boys. Her rendition of the scene grew increasingly vague, as if glimpsed through thick fog. Further questioning triggered nothing. Yet something happened that day that marked her for life. I will never know what it was.

It would be easy to paint a picture of the care home as a demeaning psychiatric ward scarred by under-funding, staffed by immigrant slave labour with a poor grasp of English on zero-hours contracts and presided over by an SS-style matron played, as in the lurid Pete Walker exploitation horror caricature, by Sheila Keith. Or, more moderately, in Play for Today manner, as a drab exercise in British social realism characterised by meaningless ritual, miscommunication and utter, life-draining tedium. Nothing happens, endlessly.

But it was not like that where mum was. The rooms were light and airy, the décor modern but homely. Here privacy is respected. Occupational therapy is meaningful and constructive. Food is excellent. Staff are professional, dedicated and respected. Birthdays are never forgotten. Individual interests are catered for. Music is used creatively. There are no voices that call out ceaselessly in the night: ‘Nurse! Nurse! When’s my daughter coming?’ They looked after mum well. I had no complaints. In short, as a departure lounge for death, it couldn’t be faulted.

In any case, mum had already left in many respects. She had no voluntary control over her body and had long since lost the ability to bear her own weight. Immobile, apart from the involuntary twitches and contortions her limbs rehearsed as a symptom of the Lewy body form of dementia, she spent most of her time in bed, levitated by an air-filled mattress. Her sight and hearing were poor, but her wiry little frame still had a pointless tenacity in its grip on life. She had no cancer; her heart was strong. She had to be fed a non-solid diet, but her appetite was undiminished. Physically, at least, she was not giving up anytime soon.

But mentally, it was a different story. Her eyes glazed over. There was no recognition. No visual response to any external stimulus, visual, physical or aural. On occasion, perhaps, there was the most fleeting, distant trace of a flicker of attention, triggered by a voice: her devoted carer bringing her meals or medication; very occasionally, perhaps, mine. But we were calling to her from a long way off by then, across a vast ocean of emptiness, from another world. Where she is there is no language that we would understand. At her most animated she issued guttural noises that sometimes, briefly, coalesced into a rhythmic pattern, or strange ‘ah, ahs’ that might have the remotest cadence of a melody. Like the faintest echo of a song. Yet these utterances always appeared random, purposeless and without connection to mood, discomfort, physical pain, need. They were unchanging, never motivated by desire or distress. And she slept for long periods. Quite contentedly, as ever. Childlike, almost, at ninety-seven.

This, then, is the last rite of passage for a generation for whom war was the finishing school of youth. At Christmastime the home always made a special effort. The decorations are lavish, there are presents all round and the kitchen pulls out all the stops in providing traditional fare. Carol singers visit during Advent and the local curate brings Christmas communion, accompanied by a female chorister who plays electric piano for the hymns. Last year, on Boxing Day, a local amateur drama troupe came in to perform the Isle of Wight Christmas Boys’ mummers’ play in the main lounge. They were a well-meaning if motley crew, and what may have been lacking in the casting department, and the learning of lines, was redeemed by the gusto of a performance that was not short on commitment. And, like much folk art, the text is as forgiving as its audience. The residents who were able to follow this surreal intervention in the afternoon, encouraged by their carers, clapped and cheered. One white-haired lady, with polished rosy cheeks, definitely officer class, cried, ‘Bravo! Encore!’ as if she were at Glyndebourne (and perhaps she was). And in the entertainment that ensued, St George gave an enthusiastic rendition of ‘The Road to Mandalay’ in perfect military Mockney, which prompted requests for ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ and ‘Pack Up Yer Troubles’. By this time the Turkish Knight (a music student and son of the local hospital’s Registrar) had sat down at the piano, and the capers concluded with ‘If You Were the Only Girl in the World’ and ‘We’ll Meet Again’, summoning a collective, quavering vibrato. Some, who had no voice left, mouthed the words silently; others who’d forgotten the words hummed the tunes. The young carer who held my mother’s hand throughout, couldn’t hold back her tears and fumbled in her pocket for a tissue. Mum, cosseted in her special padded chair, had remained impassive during the performance, but was roused to make some audible guttural noises in the songs. It was conceivable she was trying to join in. Then, as the final applause descended into a hubbub of chatter, and tea was handed round, she opened her eyes briefly and looked into the invisible space of the middle distance and said, quite clearly, ‘Yes, yes, I know’. Then, as swiftly, the veil descended and she was gone again. ‘And what do you know?’, her carer asked hopefully. But it was too late. And in any case, that wasn’t what Joan had meant.

I had already signed the form that says ‘Do Not Resuscitate’, ready for when the time came. But COVID came first, swiftly and callously. The cabinet-in-crisis decided the elderly could be sacrificed—that generation who had given up their youth long before. Restrictions on funeral arrangements dashed her long-held wishes for the military honours to which the Association of Wrens entitled her with a Royal Navy guard of honour. In the event, it was just me and mum at the crematorium, the coffin draped with a white ensign. So, two years later, the year of her centenary, the family held a memorial service and organised, belatedly, the committal of her ashes at sea.

The deposition is conducted by a RN Chaplain on board a Fleet tender that sails from Portsmouth Harbour at 14:30 every Wednesday. The Directorate General Royal Naval Chaplaincy Service provides precise guidance for funeral directors regarding the preparation of the casket:

- The ashes should be packed initially in a strong plastic bag of sufficient gauge to prevent tearing. The bag should then be place in a named rectangular container made either of solid wood or veneered chipboard.

- To ensure that the casket will sink immediately it is committed to the sea it must be neatly drilled with holes of no less than ½” diameter in the bottom and on both sides, also below the casket lid.

- The casket should be weighted inside with some form of heavy metal so as to achieve a total weight of 15lbs for a casket of the approximate dimensions of 10” x 7” x 5” and pro rata for a casket of a larger size.

- To prevent damage in transit the contents, including the weight, should be securely packed to prevent any form of movement and the removable lid or base should be securely fastened with countersunk screws of not less than 1” in length.

When it comes to death, one wouldn’t expect the Royal Navy to be anything other than eminently practical. After all, it wouldn’t do to have the casket washing up on the far shore, inscrutable as an archive, like a message-in-a-bottle in indecipherable shorthand.

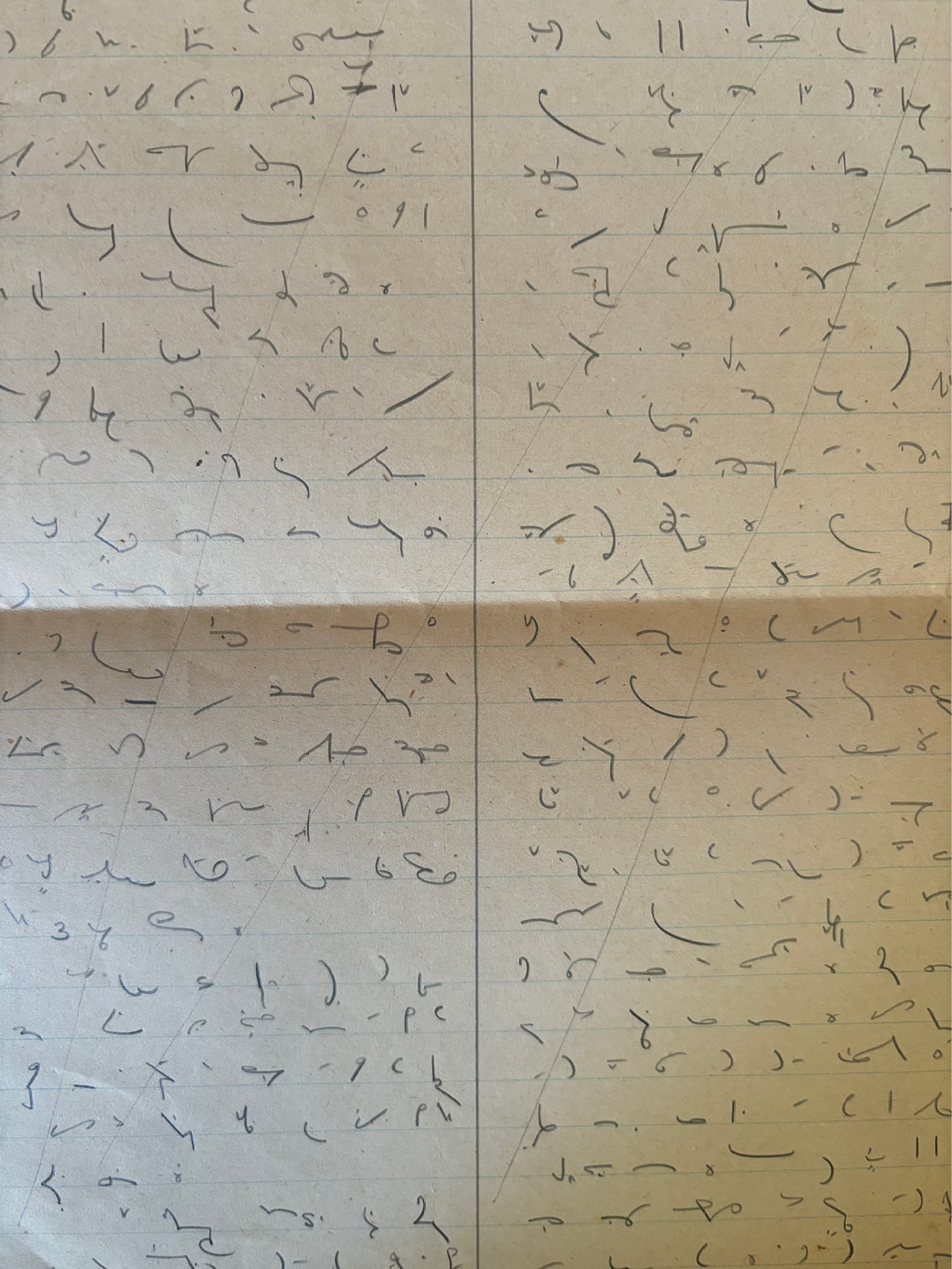

Fig. 7.2. A page from Joan Prior’s shorthand notebook. Private papers of

Joan Halverson Smith.

1 Northern Germany as far as the Bavarian and Austrian Frontiers: Handbook for Travellers (Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1910). https://archive.org/details/northerngerma00karl/page/38/mode/2up?ref=ol&view=theater&q=Minden

2 Foreign Office and Ministry of Economic Warfare, The Bomber’s Baedeker: A Guide to the Economic Importance of German Towns and Cities, 2nd edn (London: Foreign Office and Ministry of Economic Warfare, 1944). The Leibniz Institute of European History (IEG).

3 ‘The final stages of the Naval War in North-West Europe’, supplement to The London Gazette, Tuesday 6 January 1948, number 38171.

4 Phyllis ‘Ginge’ Thomas (Leading Wren), in Chris Howard-Bailey (dir.), The Vital Link: The Wrens of the Allied Naval Command Expeditionary Force, 1943–45 (VHS recording, Royal Naval Museum, 1994). Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth.

5 Jeremy A. Crang, Sisters in Arms: Women in the British Armed Forces during the Second World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), p. 199.

6 Ibid., p. 198.

7 Beryl K. Blows (3/O Wren), ‘A Wren in Europe’, unidentified press cutting (p. 47); Janet Sheila Bertram Swete-Evans, ‘Private papers of Miss J. S. B. Swete-Evans’, Documents.14994, Imperial War Museum, London. https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/1030014798

8 Janet Sheila Bertram Swete-Evans, ‘Sheila Swete-Evans papers, 1889–1988’, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University, Durham, NC. https://find.library.duke.edu/catalog/DUKE003167710

9 ‘In Holland when our transport halted we were much distressed when Dutch people came to us and begged for food. We had been issued for the journey with the usual “hard rations”—3 packs each of breakfast, lunch and dinner, of which breakfast was by far the best containing a hard lump of porridge (to be watered down and heated or could be eaten whole as a biscuit), instant coffee, biscuits and a packet of lavatory paper. There had been much swapping around of these luxuries en route as some people preferred 3 breakfasts and others the bar of chocolate which the lunch contained. When the Dutch appeared we had to be ordered not to give them all our day’s rations’. Jean Gordon (Irvine) (Leading Wren), ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’, unpublished personal testimony, D-Day Museum Archive, Portsmouth, H670.1990/5.

10 ‘In Minden our Naval HQ was a large modern building which had been the Melitta factory. Around it were factory buildings where hundreds of foreign nationals had been forcibly put to work by the Germans at the machines they contained. These were now useless of course, having been battered by the Germans before they left’. Ibid.

11 Chris Madsen observes that ‘the central location was within driving distance of Eisenhower’s new headquarters at Frankfurt, the Control Commission’s military and civilian divisions at Hanover, and Montgomery’s headquarters at Bad Oeynhausen. Requisitioning surrounding houses for accommodation, the Royal Navy transformed the industrial site into HMS Royal Henry. Additional personnel, including a large number of Wrens, arrived from London to complete the staff’. Chris Madsen, The Royal Navy and German Naval Disarmament, 1942–1947 (London & Portland: Frank Cass, 1998), p. 92.

12 Gordon, ‘Southwick Park & Normandy’.

13 Secretary Ted Grant.

14 Ginge’s exceptional qualities as a shorthand-typist of great speed and accuracy had been recognised early on in her service when she was seconded to work for General Sir Frederick Morgan at Norfolk House. In many ways, Joan Prior was happy to ‘play second fiddle’ in their relationship, both at work and leisure.

15 A.Sec Bobbie Walker.

16 Commodore Hugh Webb Faulkner, DSO, CBE, RN (1900–1969).

17 Joan’s Royal Marine friend Ken Philbrick whose father had been diagnosed with diabetic meningitis.

18 Bill Porter, RAAF. Joan’s pen-friend was still on active service in the Pacific.

19 It is interesting that Joan considers the Wrens’ social role as a sort of moral imperative. Clearly, that personal feeling was encouraged by a weight of cultural expectation.

20 The Entertainments National Service Association (ENSA) provided entertainment at home and overseas for the British armed forces.

21 Alibi (1942), was a crime film directed by Brian Desmond Hurst based on a French novel by Marcel Achard.

22 Peschke Flugzeug-Werkstätten office stationery.

23 This epitomises Joan’s recognition of the unforeseen opportunities that wartime service had afforded a young woman of her background.

24 The Red Shield Club canteens were established during World War II by the Salvation Army.

25 Kaiser Wilhelm I-Denkmal, Porta Westfalica. Doubtless unbeknown to Joan Prior and her comrades, the hill on which the monument stands concealed an underground munitions factory which the British Army destroyed using high explosives on 23 April 1946.

26 Die Wittekindsburg, Porta Westfalica.

27 Sandown, Isle of Wight, where Bess and Stan holidayed with friends.

28 The 2nd Battalion Warwickshire Regiment based at Petershagen also kept an unlikely mascot: an antelope by the name of Bobbie, as several photographs at the Imperial War Museum’s collection testify.

29 A reference perhaps to the US P-47 Thunderbolt fighter plane.

30 Charlie Snell, Joan’s elder sister Grace’s husband, was still with REME in Sierra Leone.

31 Bill Porter’s father, William George Porter (1896–1974), served as His Majesty’s Coroner, Singapore. On 12 February 1942 he was appointed to the Special Security Unit. After the fall of Singapore, he was interned by the Japanese, initially at Changi, and was subsequently transferred to the Syme Road, Internment Camp. He survived and was returned to England in November 1945 for medical treatment before resuming his position as HM Coroner in Singapore in early 1946, a position he held until his retirement in 1951.

32 Reckitt’s Blue was a popular laundry dyeing agent for enhancing white fabrics.

33 The Commanding Officer of HMS Royal Henry (as their ‘stone frigate’ was called) was Commander Nathaniel Greer Leeper, RN.

34 Surely a remarkable act of largesse!

35 Bob ‘Nobby’ Snell (Charlie’s brother) and his wife Florence were expecting a baby. This suggests that Flo had been through previous unsuccessful pregnancies.

36 Ron Smith’s unit was now back in the UK, awaiting demobilisation, but Joan speculated that a weekend pass might be all he could manage. In the event, they were able to spend five days together.

37 Royal Army Medical Corps.

38 Kenn Walsh, RM.

39 Joan Prior’s first experience of flying.

40 Ken Philbrick, RM and Tommy Atkins, REME.

41 USAAF Boeing B-29 Superfortress ‘Enola Gay’ dropped ‘Little Boy’ atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

42 Joan’s sister Grace Snell and her children David, Terry and Jacqueline.

43 USAAF Boeing B-29 Superfortress ‘Bockscar’ dropped ‘Fat Man’ atomic bomb on Nagasaki.

44 Fellow Wren Tricia Hannington.

45 W. H. Auden, ‘Musée des Beaux Arts’ (1938), Another Time (London: Faber & Faber, 1940).

46 One, in fact: Northolt.

47 Carlo Pinoli’s Italian restaurant, 17 Wardour Street, London.

48 The London Passenger Transport Board.

49 The new Chief of Staff was Commodore R. M. J. Sutton, RN.

50 As Hannah Roberts reports, ‘at the end of the war the Admiralty was unwilling to maintain the WRNS’ on the grounds of cost. However, this view was challenged (still on economic grounds) ‘in March 1946 by the personnel department’s view that women could be useful to release men for higher value work’. The WRNS in Wartime: The Women’s Royal Naval Service 1917–1945 (London: I. B. Tauris, 2017), p. 218. Joan Prior was clear in illustrating that while Wrens who had been employed in roles predominantly carried out previously by men were surplus to requirements, administrative duties were an area where the Wrens’ worth was seen to be of greater value, i.e. traditionally female roles.

51 Surely, although surprisingly perhaps given its Nazi propagandism, Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938).

52 The Priors and Boneses were negotiating to buy a hotel in Sandown, Isle of Wight, on the basis of Bess and Stan’s reconnaissance holiday in July.

53 The original of this letter is handwritten, rather than typed—Joan’s usual habit.

54 Combined tetanus and enteric prophylactic.

55 John Fitzmaurice Mills, Lieutenant, RNVR (1917–1991).

56 This semi-fictional memoir, entitled ‘Double Seven’, set in Suez, the Libyan desert and Sicily, survives in fragments across three of Joan Prior’s shorthand notebooks. Although Mills was a naval construction engineer with expertise in explosives and demolition, his autobiographical fiction may have appealed to Joan because it followed the same Allied path and theatre of operations in which Ron Smith’s Essex Regiment was engaged.

57 ‘The final stages of the Naval War in North-West Europe’, Supplement to The London Gazette, Tuesday 6 January 1948, number 38171.

58 Jo Stanley, A History of the Royal Navy: Women and the Royal Navy (London: I. B. Tauris in association with the National Museum of the Royal Navy, 2018), p. 107.

59 Dame Vera Laughton Matthews, Blue Tapestry (London: Hollis & Carter, 1948), pp. 246–250.

60 Postcards by Mabel Lucie Attwell, popular kitsch illustrator and a favourite of Joan’s.

61 Regulating Transport Officer.

62 The Navy’s replacement of demobbed Wrens with men was clearly underway.

63 Released in the USA as They Drive by Night (dir. Raoul Walsh, 1940).

64 The author, Lieutenant Johnny Mills.

65 Lyons’ Corner Houses, famous for their ‘nippy’ waitresses.

66 Stan Bones’s sister Millie’s husband, George Rawson, died on 10 December 1945. See Chapter 5, footnote 26.

67 Stan Bones’s sister-in-law.

68 A Date with Nurse Dugdale was a popular radio comedy series of 1944 starring Arthur Marshall as an efficient and officious nurse battling amidst hospital chaos.

69 Robb Wilton was a famous film and radio comedian who specialised in deadpan Lancastrian procrastination.

70 Bob and Flo Snell had a son, Laurence Alan Snell.

71 British Empire Medal.

72 Cousin Peggy Cox, daughter of Grace Prior’s sister-in-law Lucy Arthur.

73 A 1945 Powell and Pressburger film starring Wendy Hiller and Roger Livesey.

74 The leading German film company, UFA, had its Berlin and Potsdam studios taken over by the occupying Soviet forces in April 1945. This was an attempt to establish a western base for UFA and its headquarters was at the Schloss Varnholtz between 1945 and 1949.

75 Hansel & Gretel (1893) is an opera by the German composer Engelbert Humperdinck.

76 Grace and Harry Prior and Bessie and Stan Bones were about to move to Sandown, Isle of Wight.

77 Lieutenant Mills was released on 14 February 1946.

78 Harry Prior’s birthday was 5 February.

79 Tommy Atkins, REME.

80 ‘Brackla’ was the name of the hotel in Leed Street, Sandown, Isle of Wight, which Bess and Stan Bones had taken over with the assistance of Grace and Harry Prior. Joan joined them once demobbed.

81 Netherfield Gardens is a residential road in Barking, Essex.

82 Wren Jean Howard, not Irvine.

83 As Madsen reports, ‘the First Sea Lord demanded major reductions in establishments and personnel by April 1946. Consequently, the position of British Naval Commander-in-Chief Germany officially came to an end. On 15 March Burrough handed over command to Vice-Admiral Sir Harold T.C. Walker, RN, who adopted the designation of Vice-Admiral Commanding British Naval Forces Germany. […] Burrough reviewed the Royal Navy’s achievements in control and disarmament of the Kriegsmarine during his tenure […] with great satisfaction’. Chris Madsen, The Royal Navy and German Naval Disarmament, pp. 144–145.

84 From London’s Waterloo Station to the Isle of Wight, via Portsmouth (train and ferry).

85 Jimmy the cat!

86 Ventnor, Isle of Wight. A coastal resort town to the south of Sandown and Shanklin.

87 Stan’s widowed sister Millie and her daughter Margaret.

88 Crang, Sisters in Arms, p. 201.

89 Ibid., p. 202.

90 ‘The Reinstatement in Civil Employment Act of 1944 obliged employers to offer both servicemen and women the civilian jobs they had occupied immediately before their war service on terms and conditions no less favourable to them than if they had not joined the forces’. Ibid., p. 201.

91 Joan left Minden for the last time on Wednesday 15 May, travelled via Calais to Dover, thence to Chatham on 16 May for medical and was given 13 days’ leave. She travelled to Sandown, Isle of Wight, to be reunited with her family. She returned to Chatham for demobilisation on Friday 31 May.

92 Royal Marines.

93 Who had previously invited Joan to his quarters for tea.

94 A delegation of officers from Minden had attended the Nuremberg Trials where Wrens performed a variety of roles including transcription and translation.

95 The Mumbles lifeboat disaster of 1903.

96 Ginge’s fiancé Clark was also named Thomas.

97 Penny Summerfield, Reconstructing Women’s Wartime Lives, p. 260.

98 Maryanne C. Ward, ‘Romancing the ending: Adaptations in nineteenth-century closure’, The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association, 29: 1 (1996), 15–31 (18).

99 Ibid., 17.

100 Yet as Penny Summerfield notes, ‘any problems of readjustment which servicewomen might have had were rendered invisible […] and were marginalised in the parliamentary discussions of demobilisation in November 1944’. Summerfield, Reconstructing Women’s Wartime Lives, pp. 257–258.

101 Nevil Shute, Requiem for a Wren (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1955); Agatha Christie, Taken at the Flood (London: Collins Crime Club, 1948); Rosamunde Pilcher, Coming Home (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1995).

102 Edith Pargeter, She Goes to War (London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1942).

103 Summerfield, Reconstructing Women’s Wartime Lives, p. 262.

104 Ibid., p. 285.

105 From a poem ‘I’m sorry for the modern spy’, attributed to ‘FISH’. Janet Sheila Bertram Swete-Evans, ‘Sheila Swete-Evans papers, 1889–1988’, Rubenstein Library, Duke University, Durham. https://find.library.duke.edu/catalog/DUKE003167710

106 Lewis Gilbert (dir.), Carve Her Name With Pride (1958); Juliette Pattison, ‘“A story that will thrill you and make you proud”: The cultural memory of Britain’s secret war in occupied France’, in British Cultural Memory and the Second World War, ed. by Lucy Noakes and Juliette Pattinson (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), pp. 133–154 (p. 149).

107 ‘Keep mum—she’s not so dumb’, The National Archives, London. Catalogue ref: INF 3/229. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C3454442.

108 Hansard, Vol. 371, Wednesday 7 May 1941. https://hansard.parliament.uk/commons/1941-05-07/debates/8297352e-62c8-4414-ad5b-78362685dd96/Poster. For a fuller account of the Careless Talk Costs Lives MOI campaign see Jo Fox ‘Careless talk: Tensions within British domestic propaganda during the Second World War’, Journal of British Studies, 51: 4, (2012), 936–966.

109 The National Archives, London. http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/theartofwar/prop/home_front/INF3_0229.htm. For the song, see Mudcat. https://mudcat.org/@displaysong.cfm?SongID=10087

110 Ibid.

111 W.H. Long, A Dictionary of the Isle of Wight Dialect (Newport: G.A. Brannon & Co, 1886), p. 100.

112 Thomas Pettitt, ‘This man is Pyramus: A prehistory of the English mummers’ plays’, Medieval English Theatre, 22 (2000), 70–99 (72–73).