9. Phenomenography and variation theory: The development of complementary traditions

©2025 Gerlese S. Åkerlind, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0431.09

As mentioned in Chapter 2, when Marton and Booth (1997) argued that experience of variation in a dimension of a phenomenon was essential in order to become aware of that dimension (or critical aspect) of the phenomenon, they set the groundwork for what has become known as the ‘variation theory of learning’. In brief (and non-theoretical language), this theory asserts that:

- Educationally desirable understandings of subject matter are marked by awareness of particular critical aspects of the object of learning.

- So, to achieve an educationally desirable understanding of an object of learning, students’ need to discern (or become aware of) these critical aspects.

- Discernment of the critical aspects requires students to experience variation in those aspects.

- But some patterns of variation are more likely to be discerned than others.

- In particular, variation is easier to discern when it occurs against a background of non-variance, or sameness. This means that, in patterns of variation, what is not varied is as important as what is varied.

- Designing learning activities to expose students to particular patterns of variation and invariance in critical aspects of the object of learning maximises the opportunity for students to discern those critical aspects, and thus achieve the desired understanding of the object of learning.

These assumptions enable an analysis of teaching and learning activities in terms of what is made possible for students to learn (or discern) about an object of learning, based on an analysis of the patterns of variation and invariance that students are exposed to during the learning activity. It also enables educational interventions, aimed at improving students’ learning by using variation theory to design lesson plans, analyse the enactment of those plans, and evaluate the impact on learning.

Meanwhile, all of this represents a divergence from the traditional scope of phenomenography, and in this way can be described as the development of a new, but complementary tradition, with a strong applied focus. Over time, the variation theory tradition has developed:

- additional theoretical assumptions about what is needed for discernment of critical aspects of an object of learning (Marton et al., 2004; Marton, 2015);

- a distinctive approach to research based on a ‘learning study’ design (Lo et al., 2004; Pang and Marton, 2003, 2005; Marton and Pang, 2006; Pang and Ki, 2016; Pang and Runesson, 2019); and

- extensive pedagogical applications in school settings and teacher education, also commonly based on a learning study design (Pang and Runesson, 2019; Kullberg and Ingerman, 2022; Kullberg et al., 2024).

This applied focus has meant that, unlike phenomenography, the variation theory tradition encompasses not only a research arm but also an applied arm, with much of the practice of variation theory being focused on pedagogical applications rather than empirical research—though both foci may also be addressed in the one study.

As indicated above, the strong applied focus has been built around one model of intervention in particular, the learning study, which will be described further below. Meanwhile, the practice of learning studies based on variation theory has developed its own adherents, scholarly communities and even a specialised journal, the International Journal for Learning and Lesson Studies (jointly focused on publishing research based on variation theory focused ‘learning studies’ and non-theoretical ‘lesson studies’), plus an associated conference hosted by the World Association for Lesson Studies. In this sense, variation theory as a tradition has developed as strong ties with the tradition of lesson studies as with the tradition of phenomenography.

This divergence from phenomenography in theory, approach to research, scholarly communities and applied practice has made it possible for some scholars to study and apply variation theory and learning studies with very little insight into the phenomenography tradition, and conversely, for other scholars to study and apply phenomenography with very little insight into the variation theory tradition. The outcome is that there are many researchers using phenomenography without much understanding of the variation theory tradition, and conversely, many using variation theory and learning studies without much understanding of the phenomenography tradition.

Nevertheless, I personally believe it is important for anyone interested in phenomenography, especially with the intention of using phenomenographic research outcomes for educational or developmental purposes, to be aware of the tradition of research and pedagogical application using the variation theory of learning that has developed during the 2000s. This is partially because the two traditions are inevitably theoretically intertwined, and thus shed light on each other, partially because phenomenographic research can be used empirically to inform learning studies and other applications of variation theory, and partially because pedagogical applications of variation theory can be used to enhance the educational implications of phenomenographic outcomes (and most researchers engage in phenomenographic research for educational purposes).

As there are many descriptions of variation theory and applications of the theory in learning studies already in the literature, I will not be focusing on describing the tradition in detail in this chapter, but instead describing how it has developed over time from its phenomenographic roots and highlighting its ongoing relationship with phenomenography, in particular the ways in which the two traditions complement each other.

Three components to the variation theory tradition

One difficulty in describing variation theory and its relationship to phenomenography is that the diversity of developments in variation theory can create confusion when talking about the tradition, because the same term, ‘variation theory’, can be used to represent quite different aspects of the tradition. In particular, the term can be used to refer to:

- the theory itself; and/or

- empirical research based on the theory; and/or

- pedagogical applications of the theory in teaching and teacher education.

This potential for confusion in what someone is referring to when they use the term ‘variation theory’ is something I have drawn attention to previously,

I draw this distinction because, although the tradition as a whole encompasses all three aspects of variation theory, on any one occasion, people referring to variation theory may be referring to just one aspect of the tradition. This can cause confusion for those coming to understand what the term means and when comparing variation theory to other traditions. (Åkerlind, 2018)

In addition, each of the three components of the variation theory tradition can also operate somewhat independently of the others. The theory itself can be discussed without including research or practice. Research can be conducted without necessarily having an impact on practice. Plus, practice can become somewhat divorced from research and theory, in that teachers who are applying variation theory in their lesson designs often do so without a sophisticated understanding of the theory itself or of research using the theory (Pang and Ki, 2016; Durden, 2018; Thorsten and Tväråna, 2023). This is because it takes some time and effort to comprehend the theory in a sophisticated way (even though it is possible to start thinking usefully about teaching and learning in terms of what is and is not being varied, without necessarily understanding the theory in full). Nevertheless, it is not always clear what people are referring to when they use the term ‘variation theory’.

This ambiguity in what is meant when people refer to variation theory becomes particularly confusing when trying to compare phenomenography with the variation theory tradition, as I do in this chapter—that is, it makes it difficult to be precise about which aspects of the tradition one is comparing phenomenography to. So, in this chapter I will use the term ‘variation theory’ to refer to the theory, ‘variation theory research’ to refer to empirical research using variation theory, ‘pedagogical applications of variation theory’ (or learning studies) to refer to practical applications in classroom teaching, and ‘the variation theory tradition’ to refer to all three uses of the term, variation theory.

Turning to a comparison with phenomenography, in contrast to the three components of variation theory, phenomenography has only two comparable components:

Theoretical assumptions

With regard to the epistemological and ontological assumptions of phenomenography and variation theory, as described numerous times throughout this book (in particular in Chapter 2 and Chapter 5), phenomenography in the 21st century is underpinned by the theoretical assumptions outlined in Learning and Awareness (Marton and Booth, 1997). These are the same theoretical assumptions that underpin the variation theory tradition (though there have since been further theoretical developments in variation theory, described below). In this way, the two traditions are forever theoretically linked.

In addition, Marton and Booth depict ‘learning’ as a change in awareness, making learning and awareness inherently intertwined. This raises a further point of potential confusion in use of the term, variation theory—i.e., variation theory of what?. Whilst the term ‘variation theory’ is almost uniformly seen as short for ‘variation theory of learning’, there is also a ‘variation theory of awareness’ expounded in Marton and Booth’s book, as I have argued previously (Åkerlind, 2018), which also represents a variation theory. The way in which ambiguity in the term ‘variation theory’ can cause confusion may be illustrated by a conference I recently attended. At one of the sessions, a doctoral student engaged in phenomenographic research introduced her research as underpinned by variation theory. Given the most common usage of the term, I anticipated a research project on the topic of learning. But this turned out not to be so. The student went on to describe variation theory in terms of the implications of experienced variation for awareness, rather than the implications for learning—and this is a perfectly reasonable use of the term ‘variation theory’. But the fact that ‘variation theory’ is typically used as a shorthand for ‘variation theory of learning’ created a misleading impression in the first instance.

In other words, there is a ‘variation theory of awareness’ described in Learning and Awareness, as well as a ‘variation theory of learning’. These are not separate theories, but the same theory, with the variation theory of awareness also able to be applied to learning, on the basis that learning represents a change in awareness. Nevertheless, in this chapter, I will continue to refer to the variation theory of learning by its shorthand, variation theory, because that represents standard practice in the tradition.1

Empirical research

In terms of the approach to empirical research taken by the two traditions, although there are differences in method, what is more significant is that they ask different research questions (Pang, 2003; Rovio-Johansson and Ingerman, 2016; Åkerlind 2015, 2018; Kullberg and Ingerman, 2022). Generically, phenomenographic research asks, ‘What are the collective range of ways of understanding a particular phenomenon?’. And, in the 21st century, also asks, ‘What critical aspects of the phenomenon are discerned (and not discerned) within those ways of understanding?’. Variation theory research then asks, ‘What pedagogical design would maximise students’ chances of discerning those different critical aspects?’.

So, there is a logical and complementary flow in research foci between the two traditions. This has led to many research studies using variation theory that draw on preceding phenomenographic research into students’ understandings of particular subject matter, to help identify the critical aspects of the object of learning that need to be highlighted during pedagogical interventions based on variation theory. (Though there are also other ways of identifying critical aspects that have developed in the tradition, as described below.)

Pedagogical applications

With regard to pedagogical applications, although many researchers conduct phenomenographic research with the explicit aim of subsequently applying the outcomes, the actual process of application lies outside the realm of phenomenography itself. This is in contrast to the variation theory tradition, where application is an inherent part of the tradition. Thus, one very explicit difference between the phenomenographic and variation theory traditions is the focus on direct pedagogical applications of research and theory in the variation theory tradition, but not in the phenomenography tradition.

For those in the scholarly community, the focus on practical implications for teaching and learning in applied situations has become a defining feature of the variation theory tradition. In an open-ended survey I conducted with participants at the 2022 and 2024 phenomenography and variation theory conferences in Stockholm and Uppsala,2 I asked participants: “What interests you about variation theory?” and “How do you use variation theory?”. (The term, variation theory, is here being used to refer to the tradition associated with the theory, not to the theory per se.) Although three different ways of understanding variation theory emerged, all twenty-one responses focused strongly on the applied nature of the tradition, with variation theory variously described as:

- a practical tool for teaching;

- an analytical tool for teaching; and

- a theoretical tool for teaching.

1. A practical tool for teaching—The first way of describing variation theory focuses on the concrete and practical value of the tradition for improving teaching and learning. For example,

I’m interested in variation theory because of its direct practical value. Teachers will indeed change their practices of teaching in classrooms when they understand variation theory. I’ll use it to improve classroom teaching. (Response 4)

2. An analytical tool for teaching—The second way of describing variation theory focuses on the mechanisms by which the improvements to teaching and learning are made, in terms of identifying critical aspects of the object of learning, particular patterns of variation and invariance of critical aspects, and/or increasing differentiation in students’ understanding of the object of learning. Sometimes responses in this category explicitly refer to these ideas as useful for analysing teaching (which then provides an approach to planning, explaining and evaluating teaching), but at other times this is implicit rather than explicit. For example,

What interests me is how it guides teaching through creating patterns of variation and invariance. I use variation theory to first define the object of learning by its critical aspects for the target group. Then by developing teaching methods where patterns of variation and invariance changes to best lead to learners being able to discern the changed [varied] and unchanged [invariant] aspects [of the object of learning]. (Response 1)

3. A theoretical tool for teaching—It is only in the third way of describing variation theory that the learning theory itself comes to the fore. For example,

I first learned about variation theory in one of the first courses I took in graduate school. It was the first learning theory that I have ever learned and it caught my attention because of its versatility. It explains how learning occurs and what learning conditions are necessary for learning to occur. In other words, it provides pedagogical reasoning as to why some students learn better and some do not. What is more intriguing is its direct application in teaching. Teaching instructions can be crafted drawing from variation theory which can be useful for teachers, and variation theory can be used to evaluate how effective a lesson is. All of this is obvious in the Learning Study approach. (Response 15)

The distinctive difference between Categories 2 and 3 is that, in Category 2, variation theory is seen as improving teaching by providing a set of theory-informed practices for teachers to follow. In contrast, in Category 3, variation theory is seen as improving teaching by providing a theoretical basis for pedagogical reasoning. So, in Category 3, the focus is on the value of the theory itself for teaching and learning. Whereas, in Category 2, the focus is on the value of the teaching and learning practices that were developed from the theory. In addition, as can be seen from the quote above, the understanding represented by Category 3 is inclusive of that represented by Category 2, making Category 3 the more complex understanding of variation theory.

Some responses in Categories 2 and 3 referred to using variation theory for educational research as well as teaching. However, the emphasis was still on implications for teaching and learning.

Development of the variation theory tradition from its phenomenographic roots

As previously described, variation theory and its implications for learning were first described in Marton and Booth’s (1997) Learning and Awareness, based on an analysis of the cumulative outcomes of three decades of phenomenographic research on learning. Although the theory had not been given a specific title at this stage, Marton and Booth emphasised the significance for learning of the experience of variation:

What we are arguing is that it is possible to specify certain conditions that are necessary for learning of the kind we are interested in having take place [defined in quote below]. Whatever teaching method one may use…it must address certain features of the learner’s experience—a structure of relevance and a pattern of dimensions of variation—if it is to bring about certain qualities in their learning. (p. 179)

In the following year, Bowden and Marton (1998) published The University of Learning, which further developed the implications of variation theory for teaching and learning. Again, the title ‘variation theory of learning’ was not explicitly used, but was strongly implied (e.g., ‘the theory of learning’, ‘the variation theory’).

What this whole line of reasoning is about is that discernment is a defining feature of learning in the sense of learning to experience something in a certain way. Variation is a necessary condition for effective discernment… When some aspect of a phenomenon or an event varies while another aspect or other aspects remain invariant, the varying aspect will be discerned. (p. 35)

Together these two books formed the departure point for research based on variation theory and for pedagogical applications of the theory to the teaching and learning of disciplinary content or subject matter—though substantial further developments in variation theory continued to emerge over time, as described below.

From pedagogical observations to pedagogical interventions

Early research based on variation theory involved analysing naturally occurring pedagogical situations and documenting the variation in critical aspects of a particular object of learning spontaneously introduced by teachers during a lesson (e.g., Rovio-Johansson, 1999; Runesson, 1999 [as cited in Marton 2015, p. 184, with the original in Swedish]; Marton and Morris, 2002; Marton and Tsui, 2004). A common approach was to focus on different instances of teaching the same subject matter, followed by analysis of student learning outcomes based on the variation students were exposed to in each teaching situation. Such studies demonstrated learning outcomes in line with the variation to which students were exposed.

Having empirically validated the tenets of variation theory and its implications for teaching and learning over a series of studies, the variation theory tradition increasingly expanded its focus to pedagogical applications, thus developing a strong applied focus in addition to its research focus. This move to applied practice was facilitated by major government funding initiatives, initially in Hong Kong when Ference Marton was on a visiting appointment there (Lo et al., 2004), but also in Sweden where Marton was usually located.3 And by the early 2000s, the primary focus of variation theory research had moved from observing to manipulating pedagogical situations through educational interventions. This took the form of guiding teachers to introduce theoretically desirable patterns of variation and invariance in critical aspects of the object of learning, as described below.

It is important to note, however, that the move to pedagogical interventions continues to include pedagogical observations, with a clear distinction drawn in the variation theory tradition between the ‘intended’, the ‘enacted’ and the ‘lived’ (or experienced) object of learning (Marton et al., 2004). The ‘intended object of learning’ is what teachers intend for students to learn during a lesson, and is reflected in the lesson plan that has been designed using variation theory. The ‘enacted object of learning’ reflects the lesson as actually delivered, which is not always the same as planned, and this enacted object of learning can only be determined through pedagogical observation. Meanwhile, it is the enacted, not the intended, object of learning that is most relevant to students’ learning. But at the same time, not all students will experience the enacted object of learning in the same way. This leads to the ‘lived object of learning’, which is what students actually experience about the object of learning during the lesson. This is likely to vary amongst students, and can only be determined through evaluations of student learning after the lesson delivery.

The object of learning is a key concept in the variation theory tradition, so deserves a little explanation. In many ways, the ‘object of learning’ in the variation theory tradition parallels the ‘phenomenon’ in the phenomenographic tradition, in that they are each the focus of attention in their respective traditions. And indeed, the object of learning may sometimes be equivalent to a phenomenon, in the sense of representing a particular way of understanding a disciplinary concept or subject matter—but this is not always the case. Objects of learning may also represent a particular critical aspect of a way of understanding, or a particular capability for acting4 (on the understanding that “powerful ways of acting originate from powerful ways of seeing—Marton and Tsui, 2004, p. 7). The object of learning is often simply defined as ‘what is to be learned’ in any one lesson, and while this is accurate, it does not make clear that not just the content, but also the nature, of what is to be learned can vary across situations. Kullberg et al. (2024) provide a more meaningful description of what an object of learning may consist of:

[An object of learning] may be characterized as a target capability (defined as what a learner is able to do as a result of learning). … Further, an object of learning can also be characterized as a meaningful whole, as a phenomenon that it is possible to discern and explore… using, for example, phenomenography. (pp. 15–16)5

Development of particular patterns of variance and invariance of critical aspects during pedagogical interventions

Marton and Tsui’s (2004) Classroom Discourse and the Space of Learning marked the first book to be published based on the variation theory of learning, consisting primarily of a collection of educational interventions inspired by variation theory.6 As described above, the key tenet of variation theory is that, to achieve the desired understanding of subject matter, students’ need to discern certain critical aspects of that subject matter. And in order for this discernment to take place, students need to be exposed to variation in those critical aspects.

But it is possible to be exposed to variation without necessarily experiencing, or discerning, that variation. Based on the studies in this book, Marton et al. (2004) were able to identify particular ‘patterns of variation’ that were regarded as especially effective in making variation in critical aspects visible to students, in particular that variation is more likely to be discerned when it occurs against a background of sameness, or invariance. On this basis, what is not varied in a pedagogical situation becomes as important for students’ discernment as what is varied.

Four patterns of variation and invariance were recommended by Marton et al.: contrast, generalisation, separation and fusion.

- Contrast—this is because, in order to experience something as something, we must experience something else to compare it with.

- Generalisation—this is because, in order to fully understand something, we must experience varying instances of that thing.

- Separation—this is because, in order to experience particular critical aspects of a phenomenon, and to be able to separate these critical aspects from other aspects of the phenomenon, we need to experience these aspects varying while other aspects remain invariant.

- Fusion—this is because, in order to take all of the critical aspects of a phenomenon into account at the same time, they must be experienced as varying simultaneously, in relation to each other.

The order in which these patterns are experienced is also important: contrast needs to precede generalisation; and separation needs to precede fusion.

This initial recommendation of four patterns of variation became refined over time to just three: contrast, generalisation and fusion. I have not seen an explicit explanation of the removal of ‘separation’ from the list of desirable patterns of variation in the literature, but my understanding is that it is on the basis that the pattern of ‘contrast’ in and of itself enables ‘separation’. That is, the notion of ‘separation’ relates to the importance of varying each critical aspect separately, or one at a time, in order to help students discern that particular critical aspect, but the mechanism by which each critical aspect is varied is through the pattern of ‘contrast’.

As described by Marton and Pang (2006) discernment of a critical aspect requires experiencing variation in that aspect, and this requires experiencing different values along the associated dimension of variation. For example, in order to discern colour as a critical aspect, one must experience different colours, which represent different ‘values’ along the dimension of colour. In this way, varying two or more values within a critical aspect using the pattern of ‘contrast’, creates variation along the critical aspect and provides the opportunity for students to become aware of that variation and thus discern the associated critical aspect.

So, whilst separation of the different critical aspects of an object of learning remains an important concept in variation theory, in practice, separation does not require its own pattern of variation, but is achieved through contrast. Kullberg et al. (2024) explain that “Separation of a critical aspect can be made using two patterns of variation, contrast or generalization” (p. 26, authors’ italics), as shown in Table 9.1.

Table 9.1 Patterns of variation and invariance (adapted from Kullberg et al.,

2024, p. 26)

|

Critical aspect |

Other aspects |

||

|

Separation* |

|

varied |

invariant |

|

invariant |

varied |

||

|

Fusion |

varied |

varied |

*Separation, in the form of contrast and generalisation, needs to occur for each critical aspect separately, before bringing all critical aspects together in fusion

Another factor in the reduction from four to three recommended patterns of variation is that there was a move away from describing the recommended patterns in conceptual terms (as above) to describing them in more mechanistic terms, i.e., in terms of what was varied and not varied (as seen in Table 9.1), and this shift in focus allowed for only three, not four, patterns of variation.7

Meanwhile, the conceptual linkages between the original four patterns of variation helps explain differences in descriptions of practice within the variation theory research literature. Whilst some studies describe desired variation in terms of the original four patterns (contrast, generalisation, separation and fusion—e.g., Marton et al., 2004; Marton and Pang, 2006; Pang and Ki, 2016); others do so in terms of just three patterns (contrast, generalisation and fusion—e.g., Marton, 2015; Kullberg et al., 2024), and yet others, in terms of only the two main patterns of separation and fusion (e.g., Pang and Marton, 2007; Åkerlind et al., 2014). Although this variation in practice may appear confusing on the surface, in fact, all three ways of describing desired patterns of variation are consistent with Table 9.1.

Similarly, many learning studies introduce the pattern of ‘contrast’ without explicitly introducing subsequent ‘generalisation’ before moving on to ‘fusion’. This is equivalent to those studies that apply just two patterns of variation, separation and fusion, because contrast facilitates separation. In trying to understand this variation in practice, it is important to remember that student experience of an object of learning is not limited to what occurs in the classroom. Students bring different prior experiences with the object of learning to the classroom and may also engage in ‘imaginative variation’ (imagining varying instances of the object of learning in different scenarios), both during and after the lesson. So, it is often anticipated, at least implicitly, that generalisation of critical aspects may occur spontaneously amongst students once they have discerned the critical aspect through contrast. And because contrast needs to precede generalisation, it is natural that contrast becomes the first point of focus in pedagogical interventions.

Development of the model of ‘learning study’ for pedagogical interventions

The growing emphasis over the 2000s on using the variation theory of learning to inform educational interventions was accompanied by the introduction of ‘learning study’ as a key design for interventions and research using variation theory in classroom practice (Lo et al., 2004; Pang and Marton, 2003, 2005; Marton and Pang, 2006; Pang, 2006). The model of ‘learning study’ was developed from the Japanese model of ‘lesson study’ (Pang and Marton, 2003, 2005; Lo et al., 2004; Pang 2006; Pang and Lo, 2012; Pang and Runesson, 2019). Both models involve small groups of schoolteachers working together collaboratively to improve the design of individual lessons on particular subject matter. The teachers jointly devise a common lesson plan, then one of them teaches the lesson whilst others observe, and subsequent student learning outcomes are evaluated. The teachers then meet again to collaboratively reflect on the design, enactment and outcomes of the lesson, then use these reflections to develop a revised lesson plan. This is then taught by another teacher from the group, and so the cycle continues, usually for two to three rounds.

But while lesson studies do not adopt any particular theoretical basis to designing and evaluating the lessons, simply using teachers’ own sense of professional best practice, learning studies introduce a theoretical underpinning to the model in the form of variation theory, which is used to guide the lesson design, evaluation and revision process. So, unlike lesson studies, learning studies are theoretically based.8 In this way, learning studies combine all the professional development power of teacher collaborative work and teacher action research (in the same way as lesson studies), but also incorporate the additional power of a basis in learning theory. Over time, the learning study design has come to dominate both research and pedagogical applications of variation theory.

Early learning study research took the form of quasi-experimental studies, comparing the learning outcomes for students in ‘experimental’ vs ‘control’ (i.e., learning study vs lesson study) learning designs. The impact of introducing variation theory into learning design was typically dramatic, for example, 70% of the variation theory group vs 30% of the control group achieving the desired understanding of the object of learning (Pang and Marton 2003, 2005). However, the first-order perspective adopted in this approach to research formed a marked departure from the second-order perspective adopted in phenomenographic research.

Whilst this quasi-experimental design to empirical research using learning studies continues as one strand of research, not all learning studies take a first-order perspective. Over time, three different methods for evaluating learning outcomes in learning studies evolved (Pang and Ki, 2016; Pang and Runesson, 2019), with the second method currently the most common:

- comparison of the learning outcomes from ‘experimental’ vs ‘control’ teaching situations, along the lines of quasi-experimental studies (as described above);

- comparison of learning outcomes between iterative cycles of the learning study (i.e., between each cycle of a teacher delivering the planned lesson), along the lines of action research cycles; and

- a variant of the learning study approach in which the group of teachers deliver the planned lesson simultaneously, rather than sequentially, and the learning outcomes are compared on the basis of the lesson as enacted, along the lines of design experiments.

Contributing to the professional knowledge of teachers

As already mentioned, much of variation theory research and application are built around a learning study design. Not only does this design have a powerful impact on student learning, but the professional development impact reported by teachers is also substantial, described as adding extra depth to their understanding of the nature of teaching and learning, and also to their understanding of the relevant subject matter (Pang, 2006; Åkerlind et al. 2011, 2014; Rovio-Johanssen and Ingerman, 2016; Pang and Runesson, 2019; Durden, 2020).9 Consequently, the professional learning benefits to teachers started to become an additional focus of the variation theory tradition, including in teacher education (Pang and Runesson, 2019; Durden, 2020; Kullberg et al., 2024).

A recent outcome of this focus is a book on conducting learning studies using variation theory that is specifically designed for teacher practitioners, Kullberg et al.’s (2024) Planning and Analyzing Teaching. In addition to describing learning study as a way to improve students’ understanding of particular objects of learning, the authors encourage the collation and wider dissemination of the outcomes of learning studies as a way of developing the professional knowledge of teachers. Documenting the outcomes of learning studies in this way is seen as providing a cumulative source of development of professional knowledge about the teaching and learning of disciplinary subject matter, in terms of:

- critical aspects of the subject matter that students need to discern to achieve desired understandings;

- powerful patterns of variation and invariance that teachers can introduce into lesson design to help students discern these critical aspects; and

- examples of particular learning activities that can be used to create those patterns of variation.

Although I should also note that, even from its earliest inceptions, learning studies were expected to include documentation and dissemination of outcomes as a step in the process (Lo et al., 2004), to enable professional learning benefits to be shared with other teachers.

Identifying critical aspects of the object of learning in

learning studies

Learning study interventions in pedagogical practice have often used a preceding phenomenographic analysis of the relevant object of learning to identify the critical aspects that need to be focused on during the intervention. This may be done by drawing on a pre-existing phenomenographic study relevant to the object of learning, or by analysing interviews or qualitative pre-tests of student understanding of the object of learning as the first stage of the learning study. This approach maintains a methodological, as well as theoretical, link between the phenomenography and variation theory traditions.

However, there is a down-side to doing this, in that grounding learning studies in a preceding phenomenographic analysis also maximises the resources needed to implement the learning study model in schools. As a consequence, less resource-intensive methods of identifying critical aspects have emerged over time, to better encourage spread of the model. For example, critical aspects of learning objects are also commonly identified based on teachers’ existing professional knowledge, combined with reflections on learners’ responses during learning activities and pre-lesson tests of understanding (Pang and Ki, 2016; Pang and Runesson, 2019; Holmqvist and Selin, 2019; Kullberg et al., 2024). Such methods not only have the advantage of being less resource-intensive than a phenomenographic study, but also being more grounded in the day-to-day practice of teachers. In this way, such methods also better match the professional culture of teachers, by building on teachers’ professional subject and didactic knowledge in a way that is likely to enhance uptake of the learning study approach.

At the same time, however, these methods also allow teachers to search for critical aspects without necessarily having a good understanding of the nature of a critical aspect and the epistemological assumptions underlying variation theory (Pang and Ki, 2016; Durden, 2018; Thorsten and Tväråna, 2023). This makes it almost inevitable that critical aspects that are identified by teachers based on their professional knowledge and analysis of learners’ responses will be constituted in a less rigorous way than would eventuate from a phenomenographic analysis. As a consequence, the relative value of a teacher-led identification of critical aspects vs identification of critical aspects through a phenomenographic study of the object of learning has become a topic of debate in the variation theory literature (e.g., Pang and Ki, 2016; Thorsten and Tväråna, 2023).

Another difference in the way the two traditions identify critical aspects is that variation theory research and practice places a greater emphasis on identifying different values along a critical aspect or dimension of variation than does phenomenographic research. This is clearly illustrated in a study by Holmqvist and Selin (2019), where a phenomenographic analysis and a variation theory analysis were undertaken on the same data and with respect to the same phenomenon, thus allowing a direct comparison of the outcomes (see Tables 9.2 and 9.3)

Table 9.2 Outcomes of an analysis of the concept of ‘learning’ using phenomenography (adapted from Holmqvist and Selin, 2019, p. 6)

|

Critical aspects of ‘learning’ |

|

|

A: Experiencing something new |

Extended skills |

|

B: Something you do |

Process |

|

C: An advantage for future challenges |

Investment |

|

D: A knowledge object that is acquired |

Object |

|

E: A relationship between requirements for learning |

Causal relationship |

|

F: Judging what learning is |

Attributes |

Table 9.3 Outcomes of an analysis of the concept of ‘learning’ using variation theory (adapted from Holmqvist and Selin, 2019, p. 7)

|

Critical aspects of ‘learning’ |

|

|

The learner |

|

|

Learning activities |

|

|

Sources of learning |

|

|

Forms of content/ knowledge |

|

|

Outcome of learning |

|

The outcomes of the phenomenographic analysis (Table 9.2) show discernment of a different critical aspect of learning associated with each qualitatively different way of experiencing the concept of learning. But different values of each critical aspect are not specified. In contrast, the outcomes of the variation theory analysis (Table 9.3) identify a number of specific values for each critical aspect. These values represent the ways in which that critical aspect can be experienced as varying. In addition, unlike the phenomenographic analysis, the critical aspects of the concept of learning have been identified without explicitly linking each critical aspect to a specific way of experiencing learning.

So, based on the comparison provided in the Holmqvist and Selin study, at this point in the development of the two traditions, phenomenographic analysis places less emphasis on identifying the different values of each critical aspect, but more emphasis on linking the different critical aspects to different ways of experiencing than do analyses based on variation theory. This is consistent with common practice across learning studies more broadly, where it is not unusual for critical aspects to be identified by noting what is spontaneously being varied (and not varied) by students in pre-tests and classroom interactions, without necessarily clarifying the relationship between these critical aspects and specific ways of understanding the object of learning. At the same time, there is a focus on identifying different values along each critical aspect, which may then be used in lesson design to form a ‘contrast’ with each other and thus provide the opportunity for students to discern variation in that critical aspect.

The greater focus on identifying the different values of a critical aspect in variation theory research and practice has also led to a change in terminology. Initially in the variation theory literature, critical aspects were commonly also referred to as critical features (e.g., Marton et al., 2004). But in his 2015 book on Necessary Conditions of Learning, Marton selected the word ‘feature’ to be used to refer to a ‘value’ of a critical aspect (rather than to the critical aspect itself). This change in terminology may be a source of confusion for some phenomenographers, because an ‘aspect’ of a phenomenon has commonly also been referred to as a ‘feature’ of a phenomenon in the phenomenographic literature. Nevertheless, to maintain consistency between the phenomenography and variation theory traditions, and reduce potential confusion for readers of the two literatures, I think it is desirable for phenomenographic research to follow the same terminology for the values of a critical aspect as that used in variation theory research and reserve the word ‘feature’ for different values of a critical aspect.

Variation theory in higher education

So far, variation theory based learning studies have primarily been undertaken in school rather than higher education settings, with a few exceptions (e.g., Rovio Johansson and Lumsden, 2012; Rovio-Johansson, 2013; Åkerlind et al., 2011, 2014). Why is this? There is an obvious potential for variation theory to be applied in higher education (Bowden and Marton, 1998; Marton and Trigwell, 2000; Åkerlind, 2015). Plus, there are many people interested in phenomenography within higher education, so one would expect that the potential to extend that interest to learning studies and the variation theory of learning would also be present. So, why has it not happened? As someone who has tried to extend interest in phenomenography to interest in variation theory and learning studies in higher education (and so far largely failed), I have a perspective on this.

Schools have a common (often national) curriculum that runs across institutions, irrespective of the individual teachers involved. But this is not the case in higher education, where individual teachers typically have the power to set their own curriculum for the courses they teach (even if within certain parameters). This makes finding groups of teachers who are able to work on a common object of learning much easier in school education than in higher education. In addition, for teachers to dedicate time to actively engage in their own professional development as a teacher is well-accepted at school level, but much less so in higher education. Particularly in research universities, expectations of professional development in teaching are relatively low, with professional development in research much more highly valued. This makes institutional support for and teacher willingness to engage in resource-intensive approaches to teaching development much harder to find in a higher education than a school context.

Airi Rovio-Johansson is one of the few other researchers who has conducted learning studies in higher education (e.g., Rovio-Johansson, 2013; Rovio-Johansson and Lumsden, 2012), and she draws similar conclusions in Rovio-Johanssen and Ingerman (2016). Here, they describe a methodological obstacle to the cyclical nature of learning studies in higher education, in that it is possible to go through one round of collaborative lesson design, implementation, review and revision, but not the additional rounds normally expected in learning studies.10

However, in a bachelor programme, there are consecutive courses, and the order can’t be changed. Students move on to the next course. From the teachers’ perspective, there is no possibility to finish the learning study cycle in the way it is done for instance in the compulsory school. In order to apply the learning study cycle according to the learning study model, in higher education, there is a need for several methodological as well as contextual time adjustments. (p. 266)

I experienced the same difficulty with my own learning study in higher education (Åkerlind et al., 2011, 2014), where a second round was definitely needed in order to implement what teachers had learned from the first round; yet another round was not possible for another twelve months, and this was then not possible due to funding limitations.

The relationship between the phenomenography and variation theory traditions

Despite the differences between the phenomenography and variation theory traditions that I have described in this chapter, the two traditions continue to complement and enhance each other in many ways, as I will describe further below. But before I describe my own view of the relationships between them, I would like to describe how others see the relationships, based both on what is written in the literature and on responses to a small survey that I conducted. It is clear from both sources that there is not one universal view of the relationship between the two traditions (as any phenomenographer would expect), though there are some agreed upon elements.

Views from the research community

As part of the open-ended survey of participants at the phenomenography and variation theory conferences I described above, I also asked, “How would you describe the relationship between phenomenography and variation theory?”. I received twenty-one responses to the question, amongst which four inclusively expanding ways of understanding the relationship were evident:

- variation theory developed from phenomenography;

- variation theory has a theoretical focus, while phenomenography has a methodological focus;

- variation theory has an applied focus that phenomenography does not have; and

- variation theory focuses on variation ‘within’ ways of experiencing, while phenomenography focuses on variation ‘between’ ways of experiencing.

1. Development from phenomenography—The first way of understanding the relationship focuses on the historical connection between the two traditions, in that phenomenography both pre-dates variation theory and also provided the foundational research from which variation theory developed. For example:

Phenomenography is where the variation theory comes from. In other words, variation theory is drawn from phenomenography. (Response 8)

VT developed later, as part of the work of trying to tease out the learning theory involved in phenomenography. (Response 17)

2. Theoretical vs methodological focus—The second way of understanding the relationship contrasts the two traditions as having different, but complementary, foci. For example:

Phenomenography is methodological whereas variation theory is theoretical in nature. (Response 15)

I see VT as providing a theoretical framework for the development of phenomenographic work. … I see them as developing together and separately, with contributions to be made in their respective domains of theoretical and methodological advancement of the field of studying variation in human experiences. (Response 3)

3. Applied pedagogical focus—The third way of understanding the relationship positions variation theory as providing something additional to phenomenography, in terms of its usefulness for guiding classroom teaching. For example:

I also see Variation Theory as phenomenography implemented in the classroom. A powerful toolbox for teachers to consider when planning their teaching... (Response 6)

Variation theory also provides theoretical tools for practitioners (not only researchers) to design and analyze and improve teaching and students’ learning. (Response 16)

4. Variation within and between ways of experiencing—The fourth way of understanding the relationship again draws a contrast between the two traditions in a complementary way, with phenomenography seen as unpacking variation ‘between’ ways of experiencing, whilst variation theory unpacks variation ‘within’ a way of experiencing, in terms of different critical aspects that are discerned within particular ways of experiencing something. For example:

Phen is about variation between ways of understanding. VT within ways. (Response 10)

Whereas phenomenography is interested in finding the different ways that a phenomenon can be experienced, VT is concerned with the internal structure of the phenomenon and how that can be used to help reveal critical and necessary conditions for learning… (Response 12)

Phenomenography studies variations in the ways people experience a given phenomenon, while variation theory focuses on “what is a way of experiencing a phenomenon” and the distinctions between different ways of experiencing. (Response 14)

Although different words are being used in these quotes, the underlying meaning of the words are all strongly related. I have grouped them into one category because a focus on the ‘internal structure’ (or internal horizon) of a way of experiencing a phenomenon, on ‘what is a way of experiencing’ and on ‘necessary conditions for learning’ all involve a focus on identifying the variation ‘within’ a way of experiencing, in terms of the dimensions of variation, or critical aspects, of a phenomenon that need to be discerned in order to experience something in a certain way. Additional ways of describing this focus that were seen in the survey responses included that variation theory focuses on ‘what makes it possible for people to experience something’ and on ‘what should be learned’.

Conceptual aside:

Notions associated with a focus on variation within a way of experiencing

The phrases used in the survey responses representing Category 4 are also commonly seen in the variation theory literature, i.e., that the variation theory tradition focuses on:

- variation within a way of experiencing;

- the internal horizon (or structure) of a way of experiencing;

- what is a way of experiencing;

- what makes it possible to experience something;

- necessary conditions for learning; and

- what should be learned.

On the surface, it is not obvious how all of these notions are conceptually related, so I will unpack that here. As described in Chapter 5, an analysis of the ‘variation within a way of experiencing’ highlights different critical aspects of the phenomenon that are discerned within different ways of experiencing it. The set of critical aspects (including the ways in which they relate to each other and to the phenomenon as a whole) constitute the ‘internal horizon’, or structure, of each specific way of experiencing. In this sense, it is the discernment of particular critical aspects of a phenomenon (and the relations between those critical aspects) that defines ‘what a way of experiencing is’.

Meanwhile, discernment of a critical aspect occurs through the experience of variation along that aspect (or dimension) of the phenomenon, and it is this variation that explains ‘what makes it possible to experience something’. So, ‘necessary conditions for learning’ consist of exposure to variation along each of the critical aspects that learners need to discern in order to experience an object of learning in the desired way. This means that ‘what should be learned’ are the critical aspects needed to experience the learning object in a particular way.

In this sense, a specific way of experiencing may be defined in terms of what critical aspects of a phenomenon are discerned and focused on simultaneously, different ways of experiencing may be explained in terms of different critical aspects of the phenomenon that are discerned and focused on simultaneously, and what is to be learned may be described in terms of particular critical aspects of the object of learning that need to be discerned and focused on simultaneously.11

This is why I have said that all these phrases indicate, as a minimum, awareness of variation within a way of experiencing. With more data (or more detailed data) further distinctions in ways of understanding the relationship between phenomenography and variation theory might become apparent within this grouping of responses, but with these data I think it is appropriate to group them together into one category.

The different ways of seeing the relationship between phenomenography and variation theory that emerged from the survey are also reflected in the literature, as I will describe below. But there is a fifth way of understanding the relationship (which accords with my own way of understanding) that I will also present.

Views from the literature

Whilst everyone agrees that the variation theory tradition arose out of the phenomenographic tradition (in line with the first way of describing the relationship represented in my survey), this may be understood as simply a chronological development, in the sense of phenomenography preceding variation theory chronologically, rather than as the two traditions sharing common epistemological foundations or a shared knowledge interest. When thought of as a chronological connection, the shared foundations can be seen as merely historical and of little relevance to how variation theory is practiced today. Whilst when thought of as an epistemological connection, the traditions can be seen as having the potential to inform each other. So, simple statements in the literature that variation theory arose out of phenomenography can be understood in different ways.

Some authors go on to explain that variation theory arose from the analysis of decades of phenomenographic research on learning (e.g., Kullberg and Ingerman, 2022). However, the focus on phenomenographic research in such descriptions allows for a distinction to be drawn between empirical research (associated with phenomenography) on the one hand and theoretical assumptions (associated with variation theory) on the other. This distinction is commonly expressed in the literature and is fundamental to the second way of describing the relationship represented in my survey, where the phenomenography tradition is seen as primarily methodological and the variation theory tradition as primarily theoretical in nature.

In line with this view, because the variation theory tradition developed directly from the analyses in Marton and Booth’s (1997) book on Learning and Awareness—a book that can be seen as primarily about learning (e.g., Kullberg and Ingerman, 2022), even though it is also about phenomenography—this has led to some authors describing the theoretical components of the book as more relevant to the variation theory tradition than to the phenomenography tradition (e.g., Rovio-Johansson and Ingerman, 2016; Pang and Ki, 2016). This reflects the view that the phenomenography tradition continues to be fundamentally an empirically based approach, whilst the variation theory tradition is theoretically based.

Whilst I agree that the foundations of phenomenography are empirical, and the foundations of variation theory theoretical, phenomenography has since developed strong theoretical underpinnings, and the practice of variation theory strong empirical elements. For instance, the lesson study model that is so common in applications of variation theory is more empirically than theoretically grounded. (That is, whilst variation theory brings a theoretical basis to the enactment of the lesson study model as a learning study, the model itself is not theoretically based.) So, this distinction is really only applicable to the starting point of the two traditions, not to the breadth of ways in which they are practiced today.

The third way of understanding the relationship between the phenomenography and variation theory traditions focuses on the ways in which variation theory is applied in the classroom. There is no doubt that this is indeed a central difference between the two traditions, especially since development of the learning study model. In principle, distinguishing between the two traditions on this basis does not require any assumptions about how related or unrelated they are theoretically, but in practice, this distinction commonly still builds upon the second way of understanding the relationship (as seen in the survey responses), with phenomenography seen as more empirically focused and variation theory as more theoretically focused.

The fourth way of understanding the relationship places the focus of difference on an interest in variation between ways of experiencing vs within ways of experiencing. This is reflected in early descriptions of the difference between phenomenography and variation theory, starting with a key paper by Ming Fai Pang in 2003 on Two Faces of Variation. Pang describes the two traditions as linked by a common focus on variation, but on different aspects (or ‘faces’) of variation. Pang describes traditional phenomenography as descriptive and methodologically oriented, with research that asks, “What are the different ways of experiencing [a] phenomenon?” (p. 2), and I would add, ‘How are these ways of experiencing related to each other?’. This focus on variation that constitutes collective experience, is described as representing the ‘first face of variation’ in the phenomenographic tradition (i.e., the variation between different ways of experiencing).

He contrasts this with the extension to phenomenography represented by the variation theory tradition (at that early point still referred to as ‘new phenomenography’) which asks, “What is a way of experiencing a phenomenon?” and “How do different ways of experiencing something evolve?” (p. 3). This focus on variation that constitutes a specific way of experiencing, in terms of the critical aspects or dimensions of variation discerned, is described as representing the ‘second face of variation’ (i.e., variation within a way of experiencing). This includes theoretical questions about what it means to say someone is experiencing something in a particular way. And in a pedagogical situation, these theoretical questions have implications for the practical questions of ‘What is to be learned?’ and ‘What are necessary conditions for learning to take place’, because “What critical [aspects] the learner discerns and focuses on simultaneously characterises a specific way of experiencing that phenomenon” (p. 6).

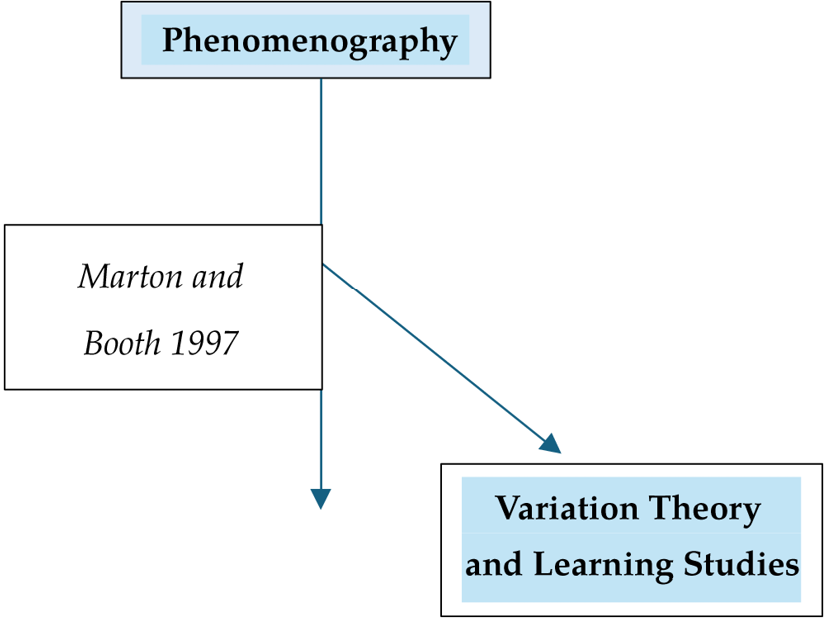

An underlying perspective evident in much of the literature as well as all four ways of understanding the relationship between phenomenography and variation theory represented in my survey is that the phenomenographic tradition is regarded as continuing largely unchanged from its beginnings. From this perspective, the publication of Learning and Awareness is seen as initiating the variation theory tradition, but being largely irrelevant to phenomenography. This perspective is represented visually in Figure 9.1.

Fig. 9.1 One view of the relationship between the phenomenography and variation theory traditions, in which Learning and Awareness is seen as having had no impact on phenomenography

However, it is obvious from my frequent references throughout this book to 21st-century phenomenography, that I disagree with this perspective (see Chapters 2 and 5 in particular). The understanding represented in Figure 9.1 is no doubt reinforced by the fact that pre-21st century approaches to phenomenography are still being practiced and published in the 2000s. However, as one of the cohort of doctoral students engaged in phenomenographic research at the time Learning and Awareness was published, I am very aware of the ways in which we attempted to incorporate the ideas in the book into our practice of phenomenography, and the resulting changes in approaches to phenomenographic research that took place during the 2000s that I have described throughout this book.

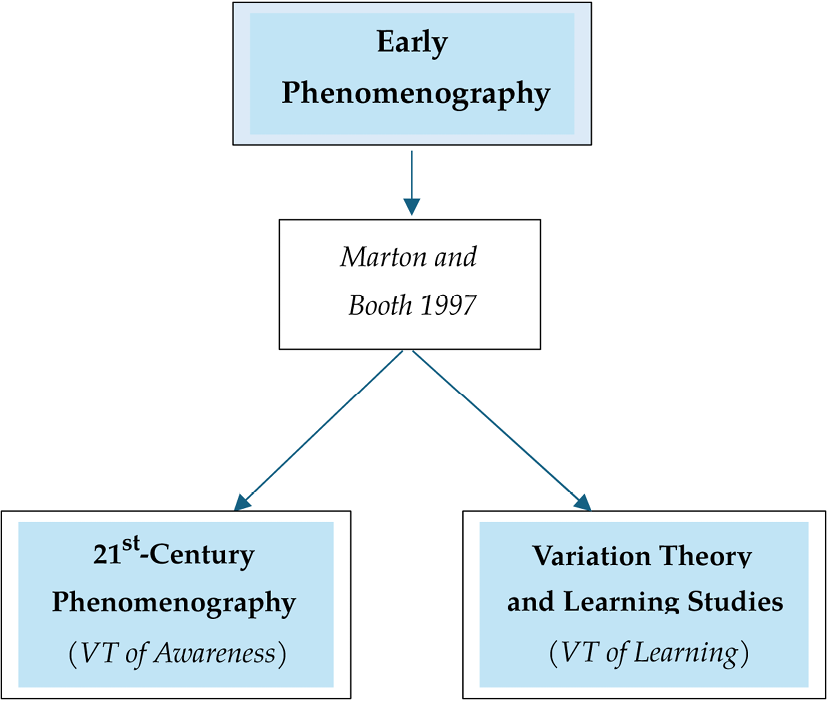

So, I would now like to present a fifth view of the relationship between phenomenography and variation theory (my own view), which is that Learning and Awareness was as influential on the phenomenography tradition as on the variation theory tradition, that Marton and Booth outlined not just a ‘variation theory of learning’ but also a ‘variation theory of awareness’ in their book, with the variation theory of awareness going on to underpin future developments in the phenomenography tradition, and the variation theory of learning going on to underpin future developments in the variation theory tradition. This perspective is represented visually in Figure 9.2.

Fig. 9.2 An alternative view of the relationship between the phenomenography and variation theory traditions, in which Learning and Awareness is seen as having had a profound impact on phenomenography

From this perspective, both variation theory and phenomenography (as it has developed during the 21st century) share common theoretical foundations based in Learning and Awareness, plus a common interest in identifying variation within ways of experiencing, as well as what is needed to move from a less complex to a qualitatively more complex way of experiencing. This way of understanding the relationship between phenomenography and variation theory may also be seen in the literature, in that any researcher who has ever used phenomenographic research to identify the critical aspects of different ways of experiencing a phenomenon is, at least implicitly, expressing this way of experiencing the relationship between the two traditions, because they are focusing on variation within as well as between ways of experiencing (see Chapter 5). I have also explicitly asserted this relationship in my own learning studies and discussions of the relationship between phenomenography and variation theory (Åkerlind, 2008, 2018; Åkerlind et al., 2011, 2014).

Lastly, indications of this view of the relationship between phenomenography and variation theory was also evident in one response to the survey described above, initially obscured by the ambiguity of the term, variation theory. Usually, the term is taken to refer to the variation theory of learning, but in this case, I think the respondent is referring to what I have called the variation theory of awareness, which they describe as ‘variation theory in phenomenography’.

Phenomenography is the empirical examination of the variations in how people think about the world, with the goal of identifying and characterizing the qualitatively different ways of experiencing a specific phenomenon. Variation theory in phenomenography further organizes the results of a research study into a two-dimensional outcome space, which articulates the aspects or specific features of a phenomenon that individuals are aware of and pay attention to, as well as the variations or distinctions in how each of these aspects are experienced by different individuals. Together across multiple aspects, the outcome space represents a hypothesis based on a set of logically related descriptions that define the qualitatively different ways of experiencing the phenomenon by different individuals. While outcome space existed as a concept before the advent of variation theory, I think variation theory helps operationalize the idea of an outcome space into something more structured. (Response 9)

In this quote, the respondent distinguishes between phenomenography and ‘variation theory in phenomenography’ in a similar way to which I have distinguished between phenomenography of the 1970s–1990s and phenomenography of the 21st century throughout this book. So, instead of being a description of the difference between the phenomenography and variation theory of learning traditions, as it initially appeared, I think this response is a description of the difference between phenomenography before and after incorporation of the theory of variation that was presented in Learning and Awareness. This response provides a further example of the ambiguity of the term, variation theory.

Meanwhile, if I were to add this way of understanding the relationship between phenomenography and variation theory to my list of ways of understanding presented above, it would be:

- variation theory is underpinned by a variation theory of learning, while phenomenography is underpinned by a variation theory of awareness.

The relationship in summary—complementary theoretical, applied, empirical and educational relationships

The four ways of understanding the relationship between phenomenography and variation theory represented in the survey tended to focus on differences between the two traditions. However, the fifth way of understanding places as much emphasis on commonalities as differences, with both traditions seen as sharing a common theoretical foundation in the variation theory of discernment outlined in Learning and Awareness and a common interest in identifying variation within ways of experiencing, as well as what is needed to move from a less complex to a qualitatively more complex way of experiencing.

At the same time, there are also differences, but I would describe these as complementary differences, allowing the two traditions to address different aspects of a mutual knowledge interest in the role of variation in human experience. As stated by respondent 3 in the survey,

I see them as developing together and separately, with contributions to be made in their respective domains… of the field of studying variation in human experiences. (Response 3)

So, the complementary differences between the phenomenography and variation theory traditions can also be seen as complementary contributions to a larger field or knowledge interest. I would group the complementary foci of phenomenography and variation theory into five areas in particular: (1) theoretical; (2) applied; (3) empirical; and (4) educational, including (5) the level of education where each tradition makes its greatest contribution.

Theoretical focus—As I have argued previously, the theory of variation and discernment outlined in Learning and Awareness presents not only a ‘variation theory of learning’, the underpinning of the variation theory tradition, but also a ‘variation theory of awareness’, which is of great relevance to the phenomenographic tradition. So, I see phenomenography in the 21st century as sharing a foundational theoretical relationship with the variation theory tradition, in terms of their shared epistemological assumptions. It should be noted, however, that the variation theory tradition has since developed further theoretical assumptions, in the form of different patterns of variation and different perspectives on the object of learning (as described above).

In addition, both 21st-century phenomenography and the variation theory tradition focus on identifying variation within a way of experiencing, in terms of identifying the dimensions of variation, or critical aspects, discerned within each way of experiencing. In phenomenographic research, this within-category variation is then used to further elucidate its traditional focus on variation between ways of experiencing (variation at the collective level), and what critical aspects need to be discerned in order to move from one way of experiencing to a qualitatively different way (as described in Chapter 2

and Chapter 5). This shared analytic framework enables the critical aspects of phenomena identified in phenomenographic research to potentially be used within learning studies whenever there is a matching object of learning.

Applied focus—Although phenomenography commenced with an applied interest, in the sense of a desire not just to understand “why are some people better at learning than others” (Marton, 1994, p. 4424), but to use that knowledge to improve teaching and learning (as described in Chapter 2), applications of the outcomes of phenomenographic research in the classroom have always represented an additional step separate from phenomenography itself. In contrast, applications in the classroom are inherent to the way the practice of the variation theory tradition has developed, in particular the large emphasis on learning studies. So, it is generally acknowledged that the variation theory tradition has a stronger applied focus than the phenomenography tradition.

Empirical focus—Empirically, phenomenography has maintained its initial focus on investigating human experience from a second-order perspective. In contrast, the applied focus in variation theory research has meant that second-order perspectives focused on the experience of students have become intermingled with first-order perspectives focused on demonstrating the pedagogical effectiveness of learning studies. So, unlike phenomenographic research, both second- and first-order perspectives can be seen in variation theory research.

Educational focus—Whilst variation theory research and practice is entirely focused on education, phenomenographic research is not. Although phenomenography arose in an educational setting and has most commonly been used to research educational topics, there has also always been a strand of pure knowledge interest, with phenomenographic research also being undertaken to better understand human collective awareness (as described in the next chapter). As a consequence, phenomenographic research is undertaken in fields outside education and has the potential to inform social science research more broadly (also discussed in the next chapter).

Level of education—Even within the field of education, the phenomenography and variation theory traditions make their main contributions at different levels of education. Internationally, phenomenography is better known amongst researchers in higher education than in school education, whereas for variation theory it is the opposite. This is not due to an inherent difference between the two traditions, but to historical and cultural reasons.

Historically, the first phenomenographic studies happened to be conducted with university students. Further, these early studies provided a basis for the distinction between deep and surface approaches to learning that subsequently became famous in higher education (Marton and Säljö, 1976). This had a major impact on higher education research and pedagogical practice, especially in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. As described by Biggs and Tang (1999), “this series of studies struck a chord with ongoing work in other countries; in particular with that of Entwistle in the UK and Biggs in Australia” (p. 61), which probably also explains the particular popularity of phenomenography in the UK and Australia (just as the Hong Kong and Swedish government funding initiatives described above explain the particular popularity of variation theory and learning study in Hong Kong and Sweden.)

The spread of variation theory, in contrast, was facilitated by government funding initiatives in school education (Lo et al., 2004; Kullberg and Ingerman, 2020). These initiatives were focused on curriculum reform at primary and secondary school level, and not tertiary or university level. They also occurred at a time when interest in Japanese lesson study was spreading internationally, and the connection of variation theory to the lesson study model through the creation of learning studies then formed part of this spread (Pang and Runesson, 2019). Meanwhile, lesson study was also primarily associated with school education, not higher education.

To conclude this chapter, I summarise the complementary foci I have discussed in Table 9.4, below.

Table 9.4 Complementary foci of the phenomenography and variation theory traditions

Chapter summary

This chapter describes the tradition of ‘variation theory’ research and practice that arose out of phenomenographic research. Originating in theoretical descriptions of the role of variation in discernment outlined in Learning and Awareness, a ‘variation theory of learning’ was developed, with an associated tradition of researching and applying the theory in the classroom. Over time, these empirical and pedagogical applications of variation theory became strongly based in the model of ‘learning studies’, developed from the better-known model of ‘lesson study’.

The chapter also describes the ways in which the phenomenography and variation theory traditions differ from and complement each other. Whilst views of the relationship between the two traditions vary, I have argued that they have a complementary relationship marked by similarities and differences in the areas of theoretical, applied, empirical and educational foci. In particular, they are underpinned by common theoretical assumptions about the role of variation in discernment and experience, derived from Marton and Booth’s (1997) Learning and Awareness. These common assumptions mean that phenomenographic research has the potential to inform the identification of critical aspects of objects of learning, which can then be utilised in learning studies. Meanwhile, learning studies have the potential to maximise the educational impact of phenomenographic research, through pedagogical interventions based on the outcomes of that research.

Having strongly focused on phenomenography’s contribution to teaching and learning in this chapter, in the next and final chapter of this book, I look beyond phenomenography’s usefulness for educational research and consider what it has to offer the broader social sciences. Whilst phenomenography is best known within the field of education, there has always been an additional strand of ‘pure’ phenomenographic research designed to investigate human collective awareness of significant social phenomena. In Chapter 10, I describe phenomenographic research that lies outside the educational arena, and the potential of phenomenography to make a greater contribution to other fields of research.

1 Nevertheless, it is fair to say that I think it would reduce confusion if standard practice in the tradition changed, and that the tradition started to be routinely referred to in the literature as ‘variation theory of learning’ rather than just ‘variation theory’—in recognition that there is also a variation theory of awareness associated with phenomenography.

2 I would like to thank Malin Tväråna for her assistance in identifying a sample for the survey.

3 This explains why Sweden and Hong Kong form the primary sites of variation theory research and practice, although it has also spread more broadly.

4 The term ‘capability’ is used in recognition that, just because one is capable of a particular way of acting, that does not mean that you will choose to engage in that way of acting on every occasion. In addition, just because one is capable of a particular way of understanding in certain situations, does not mean that you will experience that same understanding in every situation.

5 Rovio-Johansson and Ingerman (2016) also provide a useful discussion of different ways of defining the object of learning.

6 Though many of the examples in Marton and Tsui (2004) showed simplistic understandings of variation theory amongst the teachers involved, in line with my earlier comment that teachers using variation theory do not always have a sophisticated understanding of it.

7 Although hypothetically there is a fourth pattern—critical aspect ‘invariant’ and other aspects ‘invariant’—this pattern is not recommended by the variation theory of learning because it involves no variation (Marton, 2015; Kullberg and Ingerman, 2022).

8 Because the definition of a learning study (in contrast to a lesson study) is that it is theoretically-based, learning studies may also be conducted based on theories other than variation theory, but variation theory is the most common theory used.

9 Although the impact of learning studies on the sophistication of teachers’ understanding (not just students’ understanding) of the object of learning is not an explicit aim of learning studies, that it occurs is not surprising from a phenomenographic perspective, which assumes there will be variation in ways of understanding a phenomenon amongst any group—including a group of subject experts.

10 At least two, hopefully three, rounds are regarded as desirable (Marton and Pong, 2013).

11 Hence, the intense focus of the variation theory tradition on identifying and discerning critical aspects of an object of learning.