3. Germany: Additional Investment Needs Require Reform of the Debt Brake

Katja Rietzler1 and Andrew Watt2

©2024 Katja Rietzler and Andrew Watt, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0434.04

In recent quarters, German public investment has increased slightly in real terms. However, this development is driven largely by special effects such as the reclassification of public transport companies and increased military spending. Additional investment needs are estimated to be as high as 1.4% of GDP, and cannot be met without a substantial reform of the debt brake. Economists have recently come up with numerous reform proposals, but there is still no political majority for a reform. While European fiscal rules do not require much fiscal tightening in Germany, they do constrain the use of credit to finance the necessary additional public investment. Instead of a big push, the more likely scenario is continued incremental progress, or “muddling through”.

3.1 Introduction

Insufficient public investment has been an issue in Germany for years (Dullien et al. 2020; Rietzler and Watt 2021 2022; Rietzler et al. 2023). With the Federal Constitutional Court’s ruling in November 2023, which came just as last year’s European Public Investment Outlook was being finalized, a boost to German public investment has become much more difficult. The court ruled that the transfer of €60 billion of unused credit authorizations to deal with the pandemic to the climate and transformation fund (KTF) was unconstitutional and thus void. A direct consequence of the court ruling was that the KTF lost about two-thirds of its reserves. In 2024, additional funding to cover feed-in tariffs for electricity from renewable sources will come from the reallocation of funds originally budgeted for the subsidization of new production sites of computer chips. With the break-up of the government, it is unclear whether the feed-in tariffs will in future be funded from the core budget as planned. The KTF might have to rely solely on current revenue from carbon pricing to support a wide variety of transformative investment from hydrogen networks to energy-efficient home refurbishment. The “climate allowance” to mitigate the social impact of carbon pricing, which was promised in the coalition agreement, has become extremely unlikely.

The court ruling has implications beyond the KTF. It also affects other off-budget funds, e.g., for rebuilding the infrastructure destroyed in the flooding of summer 2021 (Sondervermögen “Aufbauhilfe 2021”) or the economic stabilization fund, which was intended to subsidize electricity network fees that have increased due to the need for grid investments to enable the expansion of renewable electricity. Any such expenditure will now have to come from the core federal budget, increasing the fiscal pressure. At the same time, some off-budget operations to finance decarbonization investment at the level of the federal states are now equally under threat. The off-budget fund to finance the modernization of the armed forces (Sondervermögen “Bundeswehr”) remains unaffected by the court ruling, because it was established via an amendment to the constitution, requiring a two-thirds majority in both houses of parliament (Bundestag and Bundesrat).

This worsening of the fiscal room for manoeuvre has been exacerbated by high uncertainty due to permanent disagreement in the government and its eventual break-up. This comes at a time when substantial additional investment needs have been identified. In an update of their prominent study of 2019 (Bardt et al. 2019), the IMK and the IW Köln estimate the required additional spending for general government investment and investment grants at almost €600 billion over ten years (Dullien et al. 2024b). We discuss the estimated additional spending needs below.

3.2 Recent Developments in Public Investment

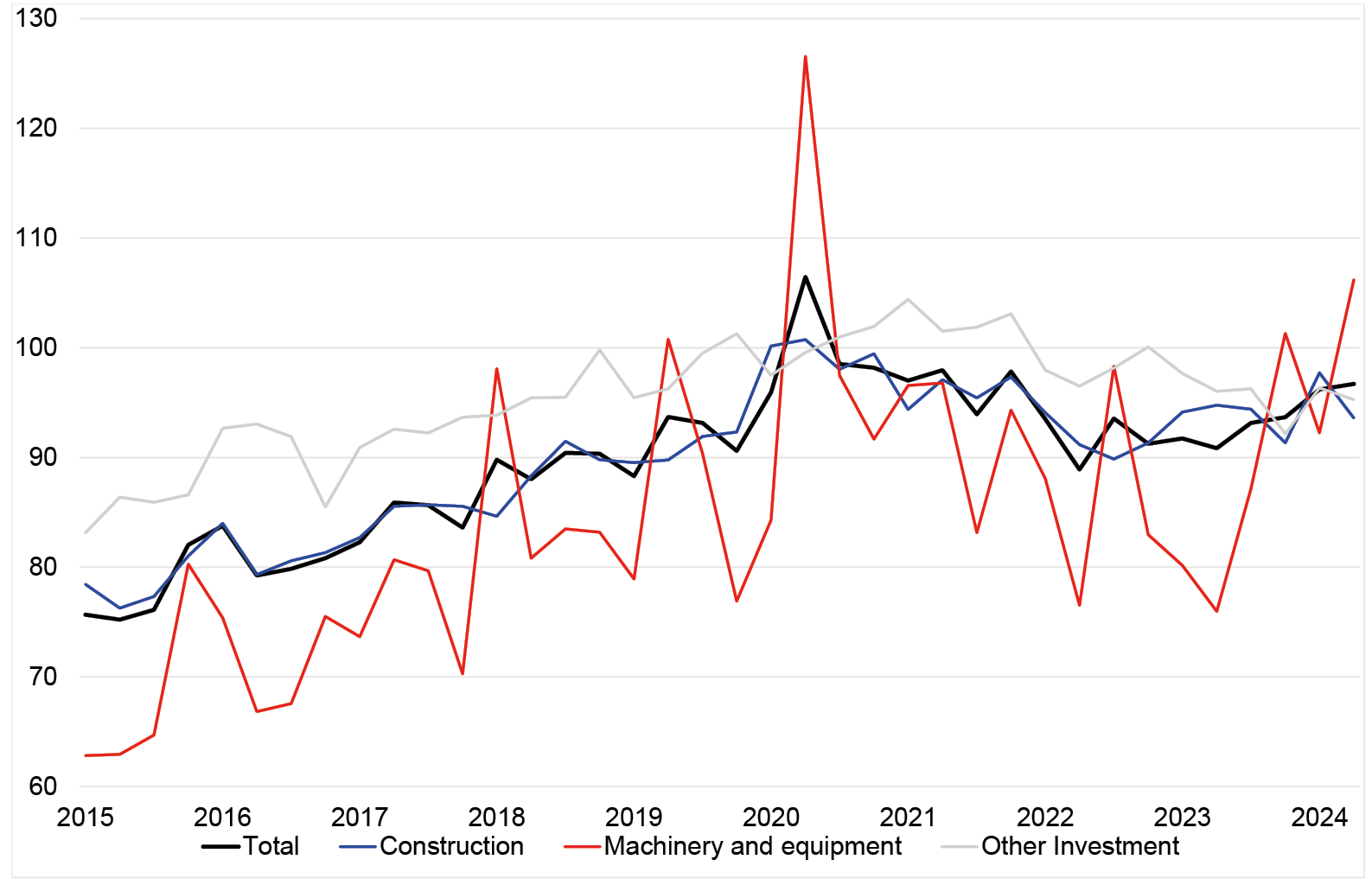

After a pronounced decline in 2021 and 2022 and stagnation in early 2023, real government gross fixed capital formation has risen somewhat since the second half of 2023, but still has not regained the peak of 2020. There has been a marked increase of investment into machinery and equipment, while construction investment fluctuated around a slightly positive trend, and the decline in other investment (mostly intellectual property) seems to have stopped (Fig. 3.1).

There are two main drivers behind the strong increase in investment into machinery and equipment: increased military spending from the extrabudgetary armed forces fund (Sondervermögen “Bundeswehr”) and investment into vehicles for local transport at the state and municipal levels. With the introduction of the heavily subsidized “Deutschland-Ticket”, a Germany-wide local transport ticket, all state-owned local transport companies were reclassified into the government sector—increasing public investment. Under pressure to consolidate the budget, the federal government that introduced the ticket is now increasingly reluctant to provide the necessary funding. Therefore, the ticket price will increase by more than 18% in 2025 and long-term financing remains uncertain, hampering the transition to a more climate-friendly transport system.

Fig. 3.1 Real government gross fixed capital formation by type (Index: 2020=100). Source: Destatis, seasonally and calendar adjusted.

|

Online resources for Fig. 3.1 are available at |

|

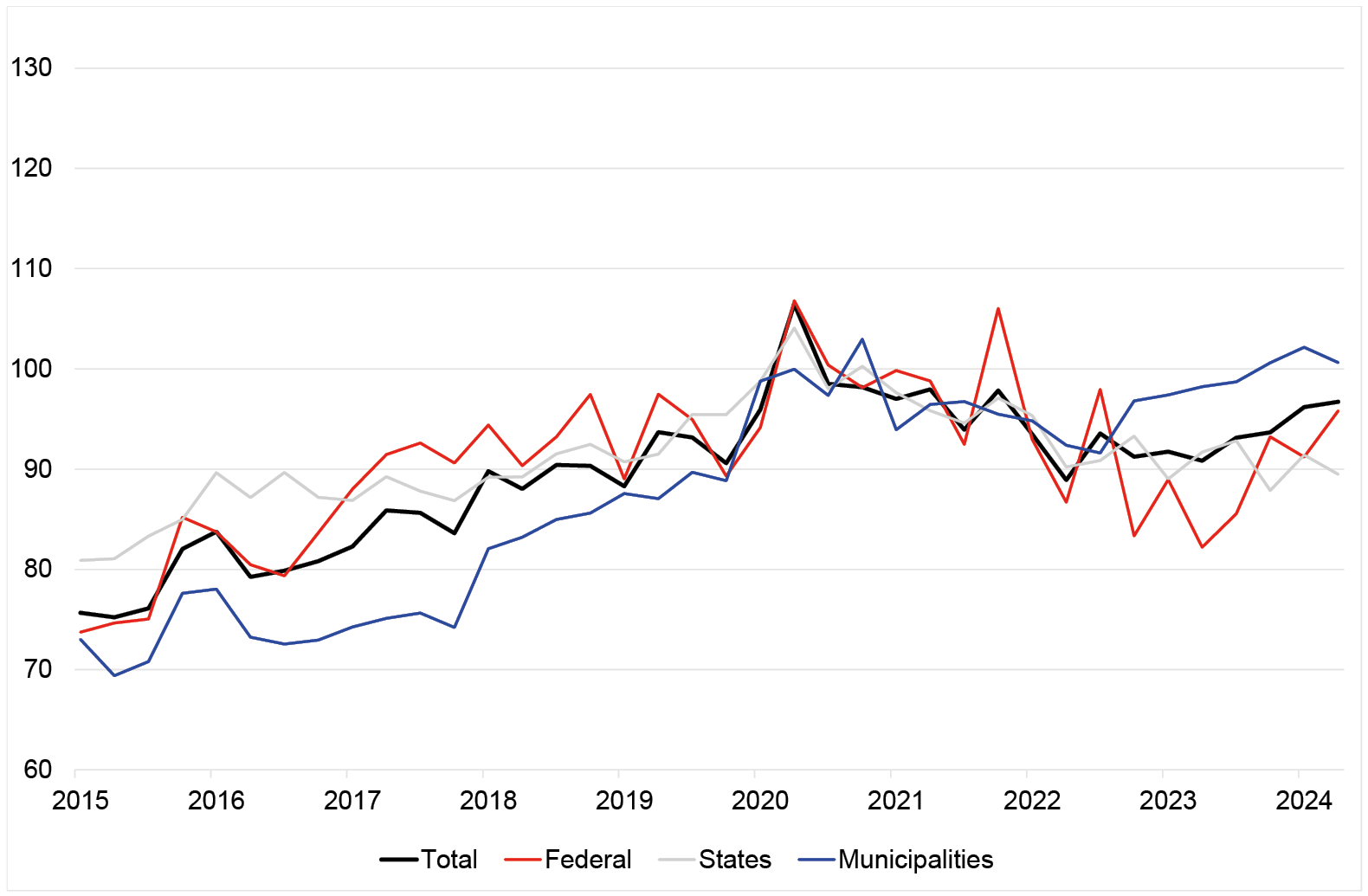

Looking at government subsectors, the slight upward trend in real investment can be attributed to the federal and municipal levels (Fig. 3.2). Investment at the state level has been weak recently, as the rise of investment into machinery and equipment has been offset by plummeting investment in construction as well as intellectual property. The municipalities, which account for almost 40% of public gross fixed capital formation (down from around 50% in the early 1990s) have sustained a strong expansion of their investment since the end of 2022, despite the massively increased price level of construction activities, which account for more than 80% of municipal investment.

Fig. 3.2 Government gross fixed capital formation by level of government (Index: 2020=100). Source: Destatis, national accounts, seasonally and calendar adjusted, adjustment of subsectors by IMK, social security excluded due to negligible amount.

It is unlikely that the relatively strong first half of 2024 marks the beginning of a new upward trend for public investment. At the federal level, much of the additional dynamic comes from defence spending out of a limited extra-budgetary fund (€100 billion over several years). The investment activity of the states is fluctuating at a reduced level. Both federal and state governments are under pressure to comply with the debt brake, which allows very limited credit financing for the federal government and hardly any for the states. The municipalities may not be able to sustain their strong investment activity due to rising pressure from increased wage costs and high social spending, while expected tax revenues have just been revised further downwards for all levels of government (BMF 2024b). A recent survey among municipalities with more than two thousand inhabitants reports an increasingly pessimistic outlook. They suffer both from a lack of funds and non-financial barriers to investment such as excessive bureaucracy, limited capacity of construction firms, and insufficient staff (Scheller and Raffer 2024). According to this survey the investment backlog of the municipalities rose further to a total of €186.1 billion in 2023 despite sustained efforts.

An additional problem is the persistence of regional disparities in public investment. Since 2011, when regional data for the whole government sector became available, Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg, and Saxony consistently showed investment per capita above the German average, whereas in North Rhine-Westphalia, Saarland, Brandenburg, Lower Saxony, and Rhineland-Palatinate it has been consistently below average. Regional disparities are therefore widening, as wealthy states can invest in their infrastructure, raising their growth potential, while poorer states are increasingly left behind.

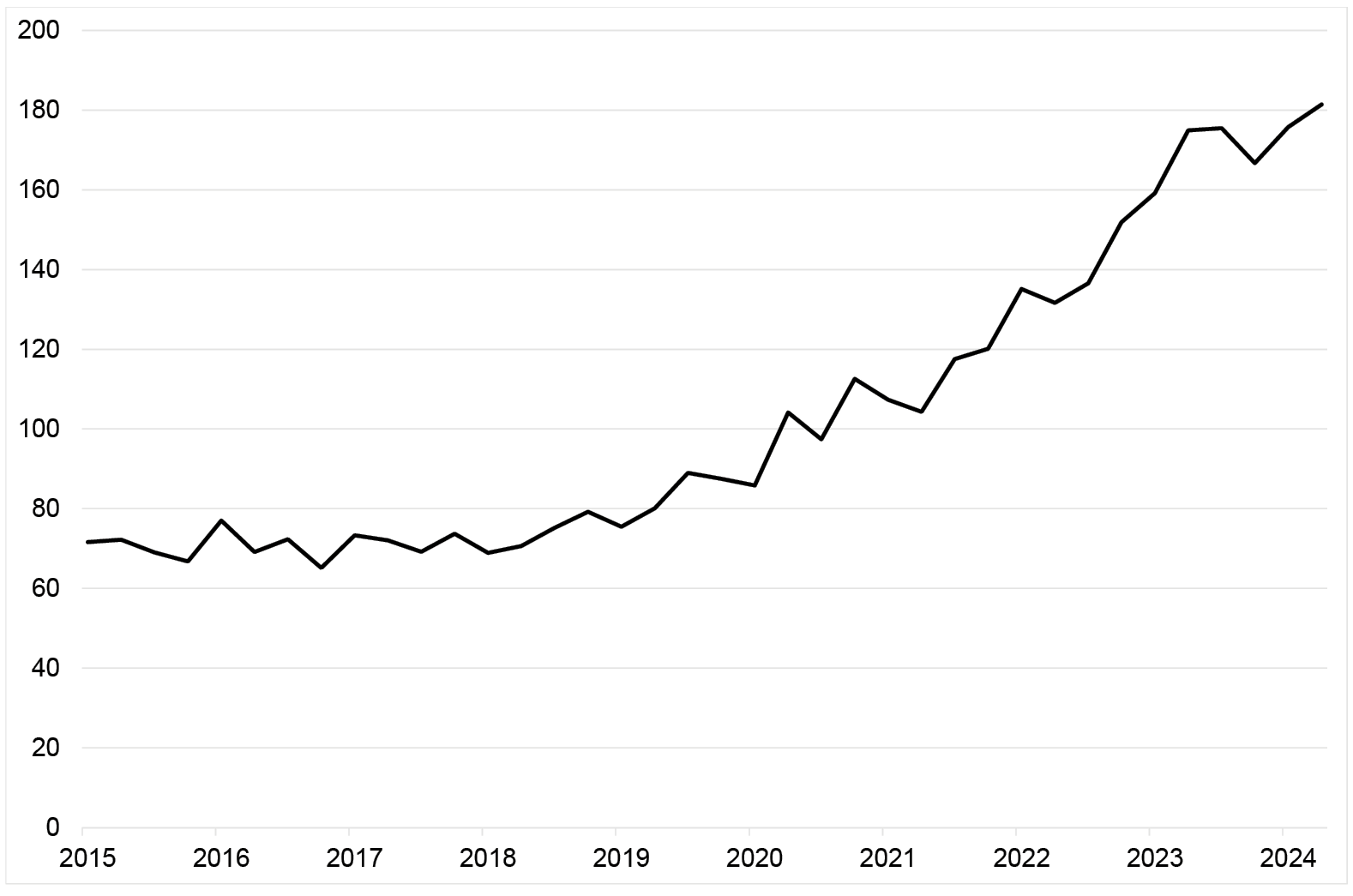

While there has been limited progress in direct public investment, government investment grants to other sectors have skyrocketed in recent years and amounted to €61.1 billion in 2023. Even in real terms, investment grants more than doubled between the first quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2024 after having been flat for years (Fig. 3.3). As the figure shows, the evolution of investment grants has lost some momentum in recent quarters. The strong rise reflects, among others, grants from the “Climate and transformation fund” as well as grants by municipalities to local businesses.

Fig. 3.3 Real Government Investment Grants (Index: 2020=100). Source: Destatis, national accounts, price adjustment (deflator of gross fixed capital formation) and seasonal adjustment by IMK.

|

Online resources for Figs. 3.2 and 3.3 are available at |

|

Cross-country comparisons of public investment need to be treated with caution, due to definitional differences (such as how motorways are financed). Still, as the European Commission notes in its spring economic forecast (European Commission 2024a: 46), Germany has recorded one of the smallest percentage-point increases in public investment (as a share of GDP) of all EU Member States between 2019 and the forecast for 2024. At under 3%, its investment-to-GDP ratio is now the second lowest in the EU after Ireland, having been overtaken by several countries, in particular, southern and eastern European countries.

In part, this is because these countries have benefited from financing from the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) and other EU funds to a much greater extent than Germany. As previous editions of the EPIO have emphasized, the RRF plays only a marginal role for Germany, contributing €28 billion over six years. On top of this, there have been delays in the originally scheduled payment of tranches from the RRF because planned milestones have not been (fully) reached (Bundesrechnungshof 2023: 12 ff.). Apart from the initial so-called “pre-financing” that was made available, Germany has submitted only one payment request (as of July 2024). The European Commission in its European Semester report on Germany described the implementation of the RRF as “significantly delayed” (European Commission 2024b: 29).

3.3 Additional Public Investment Needs Remain High

It is true, of course, that there is no simple and generally agreed basis for determining the necessary or the optimal size of the public capital stock, and thus the gap compared to its current level. Yet orders of magnitude can be derived from coupling cost estimates with political commitments to achieve certain goals (such as reducing delays in rail transport) and government commitments (such as meeting climate goals). Taking this approach, five years ago a team of researchers produced an estimate—€460 billion over ten years—which has become a reference point in the German public debate (Bardt et al. 2019). This analysis has recently been updated (Dullien et al. 2024b) and its findings are summarized here.

The revised estimates were necessary to take account of substantial changes since the first analysis. These relate, on the one hand, to the costs in nominal terms of the investments and to legal or other changes that place additional demands on the extent or urgency of transformation. Set against these forces pushing up the investment bill are those investment projects that have, in the meantime, been completed.

Clearly, the inflationary shock of 2022/2023 has increased the (nominal) cost of any given project, whereby it is not so much consumer prices, but rather construction that is decisive: the index of construction costs is roughly 40% higher than in 2019. The tightening of national and European environmental (especially decarbonization) standards and targets, and the impact of the war in Ukraine on energy supply—which demands a faster rollout of renewable energy—and a population boost—with more than one million Ukrainians migrating to Germany since 2022—have substantially increased the investment need. As in 2019, estimates of investment needs were taken from the literature and adjusted for price increases where necessary or actual investment if data are available. Unlike in 2019, current operational spending (e.g., for running kindergartens) is not included in the 2024 study.

The offsetting impact of the projects implemented during the last five years is generally rather modest, so that the ten-year public investment need is now assessed to be just under €600 billion, around one third higher—in nominal terms—than five years ago. While nominal GDP has also increased significantly, €60 billion per year presents a substantial, but far from overwhelming, 1.4% of 2024 estimated GDP. However, this amount is additional to the capital spending that is actually planned.

As in Bardt et al. (2019), the focus is on the investment needed to ensure the modernization of the economy towards a green growth model. This is one reason for why military investment requirements—however important they may be from a political perspective—have not been taken into account. Dullien et al. (2024b) offers an assessment of the order of magnitude of current investment needs, without providing an exhaustive list.

Table 3.1 summarizes the main areas of required spending. Publicly financed decarbonization measures and improvements to infrastructure at local government level, including local public transport, account for a little more than one-third of total spending needs each. Around 10% of the total, €60 billion, would be required to develop the rail network. Sums just under €40 billion each are estimated to be required for education (especially university buildings),3 public support for housing construction and refurbishment, and for trunk roads and motorways. As the federal government has made good progress in the expansion of the broadband and 5G networks in recent years, and more investment is foreseen in budget planning, no additional investment need remains in this field.

Table 3.1 Required spending for Public Investment and Government Investment Grants, in € billions, over ten years, 2024 prices. Source: Dullien et al. 2024b. Table 1, own translation.

|

Measure |

Investment need |

|

Infrastructure at local government level |

|

|

Local government infrastructure |

177.2 |

|

Expansion of public transport |

28.5 |

|

Education |

|

|

All-day schooling |

6.7 |

|

Renewal of tertiary education facilities |

34.7 |

|

Housing |

|

|

Public sector share |

36.8 |

|

Long-distance transport infrastructure |

|

|

Rail network |

59.5 |

|

Road/motorway network |

39 |

|

Climate mitigation and adjustment |

|

|

Decarbonization (public sector share) |

200 |

|

Local government adjustment measures |

13.2 |

|

Total |

595.7 |

These estimates are referred to by the European Commission in its Country Report for Germany, where, among other policies, higher public investment is called for (European Commission 2024b: 10).

3.4 Increasing Pressure to Reform the Debt Brake

As mentioned above, following the Federal Constitutional Court’s ruling in November 2023 on the second federal budget amendment of 2021, which declared the federal government’s reserve operations in extrabudgetary funds unconstitutional, it has increasingly become obvious that it is impossible to comply with the debt brake, while simultaneously integrating more than one million refugees into German society and the labour market, and investing enough into the green transformation of the economy and the modernization of German infrastructure. Apart from being problematic on theoretical grounds, tax-financing of the needed investment is a political non-starter, particularly as the conservatives (CDU and CSU) who lead in the polls favour tax cuts.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been repeated reform proposals for the debt brake (e.g. Braun 2021; Deutsche Bundesbank 2022), but the reform debate did not gain traction until after the court ruling in November 2023. Since then, prominent economists have come forward with various proposals.

The five-person Council of Economic Experts, although characterized by frequent differences of opinion and minority votes, issued a unanimous proposal to increase the scope for structural deficits up to the limit of the Stability and Growth Pact of 1.5% of GDP—from 0.35% for the federal government and 0% for the state governments, if the debt-to-GDP ratio is low (i.e., below the Maastricht reference value of 60%). Thus, this approach would not help to enable immediate credit-financed investment, as Germany’s debt-to-GDP ratio was 62.9% at the end of 2023. In addition, the Council of Economic Experts demands that the cyclical adjustment method should be made less procyclical and a transition period should be allowed for after severe crises (SVR 2024). A group of three leading economists proposed an amendment to the constitution to establish a public investment fund exempted from the debt brake. Like the fund for the armed forces and all other substantial reforms of the debt brake this would require a two-thirds majority in both houses of parliament (Fuest et al. 2024). Economists at the IW Köln propose a transformation fund along the lines of the fund for the army to finance the decarbonization of the economy (Hüther 2024; Hentze and Kauder 2024). The IMK argues in favour of a golden rule of public investment, as it works in the long term and ensures that additional debt is used for investment. It is also more transparent than enabling yet another off-budget fund (Dullien et al. 2024a).

Several proposals made before the court ruling have also received renewed attention, such as the reform concept of the Deutsche Bundesbank (2022). Its main focus is an improvement to the cyclical adjustment method that would tackle forecast errors, but includes a number of other reform proposals that would widen fiscal room for manoeuvre, such as reducing the positive balance in the debt brake’s control account4 instead of directly paying off debt taken up during the COVID-19 and energy crises, or a higher limit for new debt as long as the debt-to-GDP ratio is low. This could be combined with investment requirements. The scientific council of the Ministry of Economy and Climate Protection (Wissenschaftlicher Beirat des BMWK 2023) recommends what it calls “Goldene Regel Plus” (golden rule plus). Under this regime, net investment would be exempted from the debt brake. To prevent policy makers from declaring any spending as investment, an independent institution would have to confirm the investment character of the envisaged spending. This is what the “plus” stands for. Recently, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has also argued in favour of a higher debt ceiling, a demand it had already made in last year’s report on the annual Article IV consultations. According to the IMF, the debt ceiling could be lifted to about 1% of GDP (IMF 2023: 14).

3.5 Scope for More Investment under the Reformed EU Fiscal Rules?

As we have seen the current German national fiscal rules constitute a serious constraint for a meaningful expansion of public investment. Germany is, of course, also bound by European fiscal rules. These have just been reformed and are now to be applied, following a period in which, in response to the COVID-19 and energy crises, the rules had been suspended. What are the implications of the new European rules for public investment in Germany in the coming years?

As discussed in more detail in the Introduction to this volume, the new rules mark a substantial change (on the following, see Darvas et al. 2024). The main operative indicator is government spending, adjusted for cyclical items (such as unemployment benefits) and any changes to tax policy. Each country is subjected to a debt sustainability analysis (DSA) by the European Commission. On this basis a country-specific path for bringing the debt ratio down to levels considered sustainable is set with a four-year horizon (adjustment period). This can be extended to up to seven years to the extent that countries can show the EU Commission (and, ultimately, their peers on the Council) that their reform and investment programmes are such that they will raise potential output (and thus debt-carrying capacity) or address common EU goals or country-specific recommendations. Importantly, unlike in the national rules, the scope to put spending items, such as for the military, in shadow budgets is strictly limited under EU rules.

At the insistence not least of the German government, three so-called safeguards were added out of a fear that the rules would otherwise permit too great a degree of discretion to the Commission, particularly in classifying spending as growth-enhancing investment and thus prolonging the adjustment path. The safeguards are as follows: 1. fiscal adjustment cannot increase during the adjustment period (no backloading); 2. the debt ratio must decline by at least one percentage point a year in countries with a debt ratio above 90% of GDP, and by 0.5 percentage points for those with a debt ratio between 60 and 90% (debt sustainability safeguard); and 3. there must be at least a 0.4 percentage point annual adjustment of the primary structural balance if the structural deficit is currently more than 1.5%, with a four-year adjustment period, or a 0.25 percentage point adjustment for a seven-year period (deficit resilience safeguard). These safeguards risk reintroducing, for high-debt and high-deficit countries, the tendency towards pro-cyclicality and the limits to public investment that the reform sought to overcome. The third safeguard also smuggles the unobservable structural deficit back into the rules, which it had been intended to exclude.

Germany’s current situation is that it has a debt ratio (on EU definitions) only just above 60%, a current deficit of 1.6%, and a structural balance within the limits of the deficit resilience safeguard. As a consequence, the DSA-based rule is the constraining factor. According to an analysis by Bruegel (Darvas et al. 2024: 5ff.), based on current EU-Commission economic forecasts (Spring 2024), Germany will need to achieve a structural primary surplus of 0.4% at the end of the four-year adjustment period and just 0.1% if the adjustment is extended. This implies a very modest tightening (around 0.1 percentage points) over the four-year horizon and a broadly neutral stance if the seven-year adjustment is granted. What this means for the recommended push to higher public investment is, on the one hand, that it can be assumed that this would enable the seven-year adjustment period to be claimed and granted. However, the need to maintain the structural balance, more or less, at its current neutral stance implies that any additional public investment would need to be balanced by either spending cuts or tax financed. It is a small comfort that, according to Bruegel’s calculations, the fiscal constraint would have been tighter under the recently replaced rules.

In June the European Commission issued its first assessment under the new rules. Germany was not among the twelve countries for which an excessive deficit procedure was opened. The exact fiscal trajectory and adjustment needs communicated to the government have not been made public. However, statements by the former finance minister suggest that they are consistent with the Bruegel analysis, implying a very marginal tightening but no scope for substantially higher public investment, unless they are tax-financed.

All in all, we can conclude that the new rules are an improvement on the older ones, and they will not force Germany into a substantial policy tightening. Although the rules allow for a slightly looser fiscal stance than during most of the past thirty years, they do place tight constraints on a substantial push for higher deficit-financed public investment (Paetz and Watzka 2024).

3.6 Outlook: No Sufficient Majority for Substantial Reform of the Debt Brake

With the decision to reapply the debt brake already in 2023, the federal government unnecessarily used up more than three quarters of the general reserve of €48.2 billion generated from surpluses before the pandemic (BMF 2024a). Otherwise, this would have increased the fiscal space in coming years. The remaining amount is to be spent in 2024, so that, from 2025, the reserve is exhausted. With lower expected tax revenues and high social spending, not least for refugees, there is little room for manoeuvre for any future government. Provisional budget management will further limit the scope until a budget for 2025 is passed. In the current frail economic situation this may be better than outright spending cuts, but it is not sufficient to move Germany forward.

The most probable scenario for the near future is a continued muddling through with no great boost to public investment. While some state leaders of the Christian Democratic Union (currently an opposition party in the federal parliament, but likely to lead the next government) have spoken in favour of reforms to the debt brake, the party leadership is still reluctant. A substantial reform of the debt brake is now ruled out before a new federal government is in place and might not happen at all, as a two-thirds majority would be required in both houses of parliament. Even in the event of a reform, the European fiscal rules continue to impose constraints. Thus, the overall outlook is bleak.

References

Bardt, H., S. Dullien, M. Hüther, and K. Rietzler (2020) “For a Sound Fiscal Policy: Enabling Public Investment”, IMK Report 152e, March, https://www.imk-boeckler.de/fpdf/HBS-007619/p_imk_report_152e_2020.pdf

Braun, H. (2021). “Das ist der Plan für Deutschland nach Corona”, Handelsblatt, January 26, https://www.handelsblatt.com/meinung/gastbeitraege/gastkommentar-das-ist-der-plan-fuer-deutschland-nach-corona/26850508.html

Bundesministerium der Finanzen, BMF (2024a) “Vorläufiger Abschluss des Bundeshaushalts 2023”, Monatsbericht des BMF, January, https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Monatsberichte/2024/01/Inhalte/Kapitel-3-Analysen/3-2-vorlaeufiger-abschluss-bundeshaushalt-2023.html

Bundesministerium der Finanzen, BMF (2024b) “Abweichungen des Ergebnisses der Steuerschätzung Oktober 2024 vom Ergebnis der Steuerschätzung Mai 2024 ”, Anlage 2 zu Pressemitteilung 15 des BMF, https://www.bundesfinanzministerium.de/Content/DE/Downloads/Steuern/ergebnis-167-steuerschaetzung-02.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=6

Bundesrechnungshof (2023) “Bericht nach § 88 Absatz 2 BHO an das Bundesministerium der Finanzen zur Steuerung und Kontrolle der Umsetzung des Deutschen Aufbau- und Resilienzplans”, Bonn, December 8, https://www.bundesrechnungshof.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Berichte/2024/umsetzung-darp-volltext.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3

Darvas, Z., L. Welslau, and J. Zettelmeyer (2024) “The Implications of the European Union’s New Fiscal Rules”, Policy Brief 10/24, https://www.bruegel.org/system/files/2024-07/PB 10 2024.pdf

Dullien, S., T. Bauermann, L. Endres, A. Herzog-Stein, K. Rietzler, and S. Tober (2024a) “Schuldenbremse reformieren, Transformation beschleunigen. Wirtschaftspolitische Herausforderungen 2024”, IMK Report 187, January, https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/283062/1/p-imk-report-187-2024.pdf

Dullien, S., S. Gerards-Iglesias, M. Hüther, and K. Rietzler (2024b) “Herausforderungen für die Schuldenbremse. Investitionsbedarfe in der Infrastruktur und für die Transformation”, IMK Policy Brief 168, https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/imkpbrief/168-2024.htm

Dullien, S., E. Jürgens, and S. Watzka (2020c) “Public Investment in Germany: The Need for a Big Push”, in F. Cerniglia and F. Saraceno (eds), A European Public Investment Outlook. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 49–62, https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.0222.03

Deutsche Bundesbank (2022) “Die Schuldenbremse des Bundes: Möglichkeiten einer stabilitätsorientierten Weiterentwicklung”, Deutsche Bundesbank, Monatsbericht, April.

European Commission (2024a) “European Economic Forecast Spring 2024’, Institutional Paper 286, May, https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/document/download/c63e0da2-c6d6-4d13-8dcb-646b0d1927a4_en?filename=ip286_en.pdf

European Commission (2024b) “2024 Country Report – Germany”, Commission Staff Working Document, SWD(2024) 605, June 19, https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/document/download/0826d6c6-4c97-44be-8b9e-1a0b5c4361c8_en?filename=SWD_2024_605_1_EN_Germany.pdf

Fuest, C., M. Hüther, and J. Südekum (2024) “Folgen des Verfassungsurteils: Investitionen schützen. Vorteile eines Sondervermögens”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, January 12, https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/folgen-des-haushaltsurteils-investitionen-schuetzen-19440915.html

Hentze, T., and B. Kauder (2024) “Reformansätze für die Schuldenbremse”, ifo Schnelldienst 2/2024, 13–15, https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/sd-2024-02-haushaltspolitik-reform-schuldenbremse.pdf

Hüther, M. (2024) “Ein gesamtstaatlicher »Transformations- und Infrastrukturfonds« zur Stabilisierung der Schuldenbremse”, Wirtschaftsdienst 104(1): 14–20.

International Monetary Fund, IMF (2023) “Germany. Staff Report for the 2023 Article IV Consultation”, June 28, IFO, https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/CR/2023/English/1DEUEA2023001.ashx

Paetz, C., and S. Watzka (2024) “The New Fiscal Rules: Another Round of Austerity for Europe?”, IMK Policy Brief 176.

Raffer, C., and H. Scheller (2024) KfW Kommunalpanel 2024. Frankfurt am Main: Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, https://www.kfw.de/PDF/Download-Center/Konzernthemen/Research/PDF-Dokumente-KfW-Kommunalpanel/KfW-Kommunalpanel-2024.pdf

Rietzler, K., and A. Watt (2021) “Public Investment in Germany: Much More Needs to Be Done”, in F. Cerniglia, F. Saraceno, and A. Watt (eds), The Great Reset: 2021 European Public Investment Outlook. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 47–62, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0280.03

Rietzler, K., and A. Watt (2022) “Public Investment in Germany: Squaring the Circle”, in F. Cerniglia and F. Saraceno (eds), Greening Europe—2022 European Public Investment Outlook. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 41–53, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0328.03

Rietzler, K., A. Watt, and E. Jürgens (2023) “Germany Lacks Political Will to Finance Needed Public-Investment Boost”, in F. Cerniglia, F. Saraceno, and A. Watt (eds), Financing Investment in Times of High Public Debt–2023 European Public Investment Outlook. Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, pp. 51–68, https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0386.03

Sachverständigenrat zur Begutachtung der gesamtwirtschaftlichen Entwicklung, SVR (2024) “Die Schuldenbremse nach dem BVerfG-Urteil: Flexibilität erhöhen – Stabilität wahren”, Policy Brief 1/2024, https://www.sachverstaendigenrat-wirtschaft.de/fileadmin/dateiablage/PolicyBrief/pb2024/Policy_Brief_2024_01.pdf

Wissenschaftlicher Beirat beim BMWK (2023) Finanzierung von Staatsaufgaben: Herausforderungen und Empfehlungen für eine nachhaltige Finanzpolitik, Gutachten des Wissenschaftlichen Beirats beim Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Klimaschutz (BMWK). Berlin: BMWK, https://www.bmwk.de/Redaktion/DE/Publikationen/Ministerium/Veroeffentlichung-Wissenschaftlicher-Beirat/gutachten-wissenschaftlicher-beirat-finanzierung-von-staatsaufgaben.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=14

1 Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK).

2 European Trade Union Institute (ETUI).

3 The estimated investment backlog for school buildings is included in local infrastructure.

4 The debt brake’s control account records over- and underperformance during budget execution. There is currently a positive balance of €49.2 bn (BMF 2024a).