12. “The art of conversation”: Educational guidance practitioners and support for distance-learning students

Oliver Burney, Jennifer Hillman,

Mark Kershaw, Stephanie Newton,

Elizabeth Shakespeare, and Sean Starbuck

©2025 Oliver Burney et al, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0462.12

Abstract

This chapter addresses the critical issue of connection in Higher Education in the post-pandemic era. While hybrid learning, virtual campuses, and remote teaching have expanded educational access, they have also, paradoxically, contributed to feelings of disconnection among students and staff. As universities begin to explore the role of artificial intelligence (AI) in guidance services, questions remain about how technology can enhance—rather than replace—human connection. This piece draws on a dialogue session with Educational Advisers at the Open University (UK) who provide telephone-based guidance to distance-learning students in STEM. Through collective reflection on guidance practices and engagement with relevant literature, the chapter offers insights into the art of telephone-based guidance conversations, highlighting the enduring value of human connection in educational support, to create a pedagogy of hope.

Keywords: educational guidance; distance-learning; telephone guidance; guidance principles

Introduction

The Open University (OU) is one of the largest providers of distance-learning Higher Education (HE). More than 2 million students have studied with the OU over the last fifty years, and the university has a current body of approximately 5000 tutors. The institution also has a long history of providing telephone educational guidance to students; traditionally this took place within the faculties and more recently it moved to teams of Educational Advisers situated in each of the four Student Recruitment and Support Centres (George, 1983; Tait, 1998; Hilliam et al., 2021). Educational Advisers work within the Information, Advice, and Guidance (IAG) continuum of support, as part of a wider student support team for students and enquirers. In our organisation, guidance is defined as follows:

The process of helping enquirers and students with more complex needs to explore issues that may present a barrier to successful study. Practitioners will encourage enquirers and students to assess appropriate options and make decisions that are in their best interests and will facilitate learning and progression (The Open University, 2022).

The institutional IAG framework helps to differentiate advice from guidance, which is, ideally, impartial rather than directive. A large part of the Educational Adviser role is to help students navigate their options in relation to teaching, learning, and assessment processes and policies; this necessitates referrals and liaison with other specialist teams. In their guidance practice with students, Educational Advisers work primarily by telephone—either reactively via an inbound telephone service or via a pre-arranged outbound telephone appointment. Interactions may be a one-off discussion, or part of a continuous dialogue with repeated contact over a prolonged period. The service is accredited by Matrix (UK IAG Quality Standard) whose definition of guidance is supporting “the specific needs of the individual”, which may involve either “a session or series of sessions between an individual and a skilled and trained advisor” (Matrix, 2021).

In the wider international context of HE, guidance takes varying forms. One survey of practice across fifteen EU member states conducted over two decades ago found that guidance was traditionally being used to support student degree/module choice at the pre-entry and induction stage, but—at the time—careers guidance was “the fastest-growing area” (Watts & Esbroeck, 2000, p. 17). A more recent piece compared guidance practice in Denmark and China. In Denmark, guidance included both counselling and career planning, whereas in China a typology of three main forms was found, encompassing employability, careers, and mental health (Zhang, 2016). The importance of guidance in supporting student success is well documented (Sewart, 1993). A study at Università Roma Tre found causal links between the provision of guidance and academic achievement (Biasi et al., 2018). There is a strong consensus in the literature that, however they operate, guidance services support students’ agency to consider their options and empower decision making—especially when they encounter study and personal setbacks (Colas-Bravo et al., 2016; Määttä & Uusiautti, 2018). Other pieces have demonstrated the role of guidance in supporting HE students from underrepresented backgrounds to move into graduate career pathways (Cullen, 2013, cited in Hooley, 2014, p. 38). Common to most guidance service models is, perhaps, something akin to Freire’s (1994) Pedagogy of Hope (and later bell hooks, 2003), where the focus is enabling individuals to pursue their goals (Zhang, 2016)—or, in Danish, vejledning (leading someone on their way).

The provision of guidance in our setting at the OU certainly aligns with this. As a distance-learning provider without prerequisite qualifications from students or “entry grades”, the OU student body is diverse with many students being from what are often considered “non-traditional” backgrounds. For example, across May and June 2023, the average age of students engaging with the guidance service in the Faculty of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) was thirty-seven years old. Our data analysis has found that in the same period, 70% of the students we supported had a declared disability, 47% had mental health needs, and 45% were living in areas in the bottom two quintiles of the index of multiple deprivation. Here, then, we aim to share and shed light on the principles of telephone guidance in our unique context.

What follows in the next section of this chapter is a conversation convened over video conference among four practitioners and two supporting managers from the guidance service in STEM. Our focus was to consider the principles of guidance practice in the context of distance learning, in the broadest sense. The ensuing discussion has been transcribed and lightly edited, with the objective of providing readers with a picture of our conversation as it happened organically.

Educational advisers in conversation

Principles of telephone guidance

Elizabeth Shakespeare: As a guidance practitioner, what have you found to be the most important principles of guidance when supporting distance-learning students over the telephone?

Sean Starbuck: The most important thing is creating the space. At a campus university, that might be a separate corner of a room, or an office. Over the telephone it is setting out our stall that we are here to spend time with someone and, of course, that is part of the contract that we create with them about the time we have and how we can use it.

Mark Kershaw: I agree with Sean about the creation of space; it’s about creating the right environment for a guidance conversation to take place. Alongside that, for me, is trying to break down the thought of any power relationship that might be assumed within our conversation, or between a student and the university. Through language, we create a space in which students feel comfortable in talking about their situation, their aspirations, their problems, their needs, etcetera, and feeling it is a collaborative space.

Stephanie Newton: Like Mark, I think we try as far as we can to set ourselves apart from the university and that we do not represent a particular agenda. It’s trying to give that unbiased approach to helping them feel comfortable and open-up in guidance conversations.

Sean Starbuck: If we imagined this visually, we would be walking side by side with the student.

Oliver Burney: I agree. One of the principles we use and try to convey is: I believe in your potential. I’m here to help you to express yourself, get somewhere and get to some actions. You’re accepting of the whole person and welcome them even with their issues or problems. With distance-learning students, you realise they’re sitting in their house. You’re trying to make that more present, that moment, they’re in their house, doing whatever they’re doing. You can hear the dog barking. You notice those things because it’s important to it being a real experience, where students bring their whole selves, rather than something transactional between two people.

Holistic guidance at a distance

Elizabeth Shakespeare: The reality of our work is that students are in their home situation and surrounded by their things, or at work, or some other personal context. How does that shape your guidance practice? Working over the telephone, how do you ensure you consider this student holistically in the context of their wider environment and lives?

Mark Kershaw: Using something like the helicopter approach where using language you travel through the layers of perception up to a point where you get to that sense of this is my motivation. This will. This is why I’m here. Using both visualisation and metaphor are colourful ways of exploring ideas over the telephone.

Oliver Burney: That’s one of the challenges with telephone guidance is making it memorable.

Stephanie Newton: The telephone can be less inhibiting for some students – more so than video call even—in that they feel a bit more anonymous. However, it makes it a very different experience for us because we can’t see the person in front of us, so we can’t pick up on those visual clues about how they might be feeling. We have to do a lot more listening and questioning than you might have to do in person.

Mark Kershaw: On this note, I just want to share an anecdote about that from a personal perspective. I popped into my local pub a few weeks ago and they were having a Motown event. I went in there and it was like I’d walked into a bar in Alabama. The pub went silent, and I felt I was being looked at. That’s the thing about the phone, I find my race becomes irrelevant and it makes me feel more confident that I don’t feel I’m being judged. Perhaps it is the same for students. That any visible characteristic that they feel might be a barrier to connection or communication is not.

Oliver Burney: That’s anonymity, isn’t it? Which is disinhibiting, I think.

Emancipatory guidance practice and its challenges

Jennifer Hillman: One principle we haven’t discussed is the extent to which guidance should or could be empowering students. Almost a decade ago, the case was made for the need to develop new, more “emancipatory” approaches to guidance in the careers sector (Hooley, 2015). What do you consider to be the relationship between educational guidance in HE/adult learning, and social justice?

Sean Starbuck: This is something that I’ve tried to integrate into my day-to-day practice. We have to be conscious of our mindset and suspend judgement. Students can present in a way that it feels that that they’re facing an uphill battle or there’s very little progress or there’s the conditions in which they’re working within, which are making things very difficult for them to succeed or to inch towards their goals. Many students haven’t had the opportunity to reflect; guiding them to see where their strengths are in other parts of their lives and how they apply to study, you’re almost building that wall from scratch, brick by brick.

Mark Kershaw: I’m conscious of the creation of this whole industry of self-help and housing all the possibility of change within the individual as opposed to society. I think much of my work tends to be around the individual and trying to help the individual to develop, adapt and change. But I know there are all sorts of structural impediments to success, and all my conversations with the students aren’t going to change those. I remember in the 1980s in careers guidance, there was some dismissal of the structural barriers to career progression (Roberts, 1977). Obviously, things have changed but I feel I am still working at an individual level. Currently I am acknowledging that there are barriers and collaborating with the student to show that there are ways that we can perhaps navigate the way through together. I need to think about how I challenge those structural impediments and how guidance can help to breakdown some of those barriers.

Sean Starbuck: I think sometimes our role as a default can feel too neutral. Not that I want to take a directive approach as my default, but a student’s path is going to be easier to navigate if they don’t have lots of social structural factors working against them. By offering the same approach for every student, that’s an inequality in itself, isn’t it?

Stephanie Newton: I’m reflecting on what you were saying about not necessarily treating everyone the same. We might sometimes think of our role as helping empower students to become more independent learners and help them find ways to do things themselves. But, like Sean says, I think we do sometimes need to advocate for students. It’s also imperative that we are having these wider conversations to find out what is actually a barrier for an individual and not making assumptions based on what we think we know.

Oliver Burney: I see this issue of social justice and guidance as potentially unlocking us as a resource, where we as practitioners are ignited by the justice of the situation, I suppose. I think that this is only in its infancy in terms of my own practice. But education is one of the places where that social justice happens; it bubbles away and then eventually it grows, doesn’t it? We should be thinking of our students as driving change. If we’re supporting students to stay on course, they’re investing in their future. And we are part of the optimism of investing in their future.

Sean Starbuck: I also think guidance has a unique role in that because we’ve all had those conversations with students where you realise this is the first time they have allowed themselves to vocalise something. That’s a radical thing because society doesn’t tend to give people that space. That’s not what’s seen as worthwhile or productive because it’s intangible. It’s often immeasurable. But the things that students can tell us after a conversation with us, you can see the growth.

Elizabeth Shakespeare: This is something that they take with them in the way that they face the world, and the way they think about themselves in the world. That’s one of the most precious things that we can do for them. That does make me feel hopeful.

Some (hopeful) principles for remote educational guidance

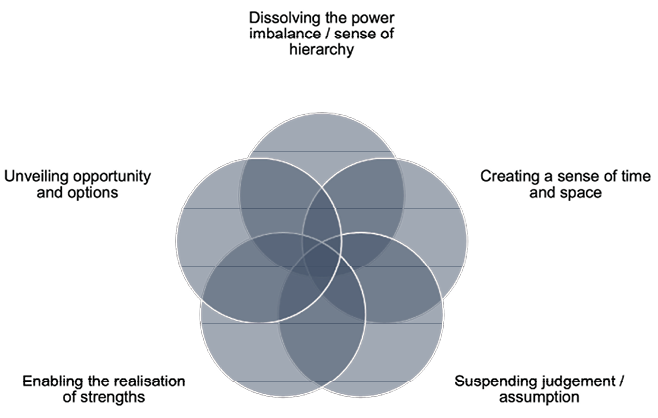

Like all good guidance conversations, our discussion was the starting (not end) point for designing action and reflection. The excerpt above captures our thoughts – in the moment—about our telephone guidance service for a largely “non-traditional” student demographic. If we were to visually distil the conversation above and capture the elements of what we seek to do as practitioners, it might look something like Figure 12.1 below. As a set of guidance principles, it is neither comprehensive nor complete, but it is rooted in our shared values about the role guidance plays in a more hopeful educational experience at university.

Fig. 12.1 A visual representation of our live reflections “in conversation” (image by authors, CC BY-NC 4.0).

Cutting across our conversation was the sense that guidance practice has often been about helping individuals to navigate structural or societal systems that do not work well for them rather than addressing the macro issues. However, we began to explore the place of a low-tech or “old-tech” telephone conversation in this (Simpson, 2000).

Our discussion began with us thinking aloud about the experiential aspects of guidance. In our remote work, we necessarily enter the student’s home or work environment and (albeit via the telephone line) wider life. We shared the experience of connecting with distance-learners to create a memorable interaction where the student is never “passive” (Gendron, 2001, p. 77) and where guidance “connects meaningfully to the wider experience and life of the individuals who participate in it” (Hooley, 2014, p. 57). We played with the idea that there is something profoundly disinhibiting about telephone conversations for both students and staff, observing the equalising impact of the telephone—where sharing things like ethnicity, or social-economic setting become a choice, not a default. Here our anecdotal commentary is tentatively supported by usage data: in May 2023, for example, we found a higher proportion of STEM students from racially minoritised backgrounds accessed guidance support through telephone contact than by email—a difference of 8% points. Other studies have found examples of student preference for telephone contact with tutors (Croft et al., 2010).

We reflected on the way the telephone requires us to interact differently than we might do in person in order to be able to convey our fundamental belief in the strengths and abilities of the student. We addressed how we each navigate the tension between a necessarily broad “helicopter” approach (Arthy, 1999) allowing us to see and “unpick” wider and deeper issues being raised, with the requirement to be boundaried and structured. As others have noted, “effective use of the telephone requires, and therefore encourages, discipline […] The lack of access to visual cues can be compensated by greater attention to aural cues” (Watts & Dent, 2002, p. 4).

Like other practitioners who have thought about the application of a pedagogy of hope outside of formal classroom teaching, we have started to see the place of the telephone guidance conversation in “unveiling opportunities for hope, no matter what the obstacles may be” (Freire, 2004, pp. 2–3, cited in Van Hove et al, 2012, p. 46). Our musings concluded with some thoughts about whether there is a place for a less neutral model of guidance where practice is about challenging—rather than navigating—the structural “obstacles” themselves. Here, our guiding principles or model for telephone guidance would also include the emancipatory power of advocacy as a feedback loop to the institution.

Broadly speaking, we recognise that in the remit of our roles, guidance has a functional role: unlocking an open and inclusive education for students and ensuring their academic success. Ultimately, however, “in conversation” we collectively began to see guidance as an end unto itself in supporting the realisation of strengths and developing lifelong critical and reflexive skills in our students. What we hope to have foregrounded in sharing our reflections is the simple power and implicit hopefulness of the guidance conversation.

Steps toward hope

- Prioritise fostering genuine human connections in hybrid and remote learning environments to counteract the disconnection amplified by virtual campuses and social media.

- Explore the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in guidance services as a tool to enhance, rather than replace, empathetic and human-centred support.

- Leverage human-based guidance conversations to provide continued personalised support tailored to students’ academic and personal needs.

- Encourage collective reflection and collaboration among Educational Advisers to refine guidance practices and share effective strategies.

- Engage with literature on guidance services to inform best practices and continually improve support systems in Higher Education.

References

Arthy, D. (1999). A cultural analysis of parachutes, regulators, and helicopters in career planning. Australian Journal of Career Development, 8(3), 1–8.

Biasi, V., De Vincenzo, C., & Patrizi, N. (2018) Cognitive strategies, motivation to learning, levels of wellbeing and risk of drop-out: An empirical longitudinal study for qualifying ongoing university guidance services. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 8(2), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.2478/jesr-2018-0019

Booth, R. (2006). E-mentoring: Providing online careers advice and guidance. Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning, 10(1), 6–14. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/147951/

Colas-Bravo, P., Gonzalez-Ramirez, T., Conde-Jimenez, J., Reyes de Cózar, S., Antonio Contreras-Rosado, J., & Villaciervos-Moreno, P. (2016). Counselling and guidance in European higher education for inclusion. ECER Conference Proceedings, Leading Education: The Distinct Contributions of Educational Research and Researchers. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307477264_Counselling_Guidance_in_European_Higher_Education_for_Inclusion

Croft, N., Dalton, A., & Grant, M. (2010). Overcoming isolation in distance learning: Building a learning community through time and space. Journal for Education in the Built Environment, 5(1), 27–64. https://doi.org/10.11120/jebe.2010.05010027

Cullen, J. (2013). Guidance for inclusion: Practices and needs in European universities. European Commission.

Freire, P. (2004). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Gendron, B. (2001). The role of counselling and guidance in promoting lifelong learning in France, Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 6(1), 67–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596740100200091

George, J. (1983). On the line: Counselling and teaching by telephone. Open University Press.

Hilliam, R., Goldrei, D., Arrowsmith, G., Siddons, A., & Brown, C. (2021). Mathematics and statistics distance learning: More than just online teaching. Teaching Mathematics and its Applications: An International Journal of the IMA, 40(4), 374–391. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hrab012

hooks, b. (2003). Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. Routledge.

Hooley, T. (2014). The evidence base on lifelong guidance: A guide to key findings for effective policy and practice. European Lifelong Guidance Policy Network.

https://repository.derby.ac.uk/download/

a6dd8f619ce81d6c66ffa3d216a83b0f3a09fd538ab7645f28677a98255b74b5/

2365010/elgpn-evidence.pdf

Hooley, T. (2015). Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery: Self-actualisation, social justice and the politics of career education. International Centre for Guidance Studies, University of Derby. https://repository.derby.ac.uk/

download/

97a1f77f605e4ead9f2c7dcf61bf75a8a382733d07b6a0e6a116d5c85b994f8f/

890289/Hooley%20-%20Emancipate%20Yourselves%20from%20Mental%20Slavery.pdf

Määttä, K., & Uusiautti, S. (2018). The psychology of study success in universities. Routledge.

Matrix (2021). People, professions, and resources: Quality standards for information, advice and guidance services: A review of the literature. Matrix. https://matrixstandard.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/matrix-lit-review-final.pdf

Office for Students (2022). Students should expect high quality teaching, however courses delivered—OfS responds to blended learning review. OfS. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/ofs-responds-to-blended-learning-review/

Roberts, K. (1977). The social conditions, consequences, and limitations of careers guidance. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069887708258093

Sewart, D. (1993). Student support systems in distance education. Open Learning, 8(3), 3–12.

Simpson, O. (2000). Supporting students in open and distance learning. Kogan Page.

Tait, A. (1999). Face-to-face and at a distance: The mediation of guidance and counselling through the new technologies, British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 27(1), 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069889908259719

The Open University (2022). Information, advice and guidance policy. https://help.open.ac.uk/documents/policies/information-advice-and-guidance/files/29/iag-policy.pdf

Uusiautti, S., Hyvärinen, S., Kangastie, H., Kari, S., Löf, J., Naakka, M., Rautio, K., & Riponiemi, N. (2022). Character strengths in higher education: Introducing a Strengths-Based Future Guidance (SBFG) model based on an educational design research in two northern Finnish universities. Journal of Psychological and Educational Research, 30(2), 33–52. https://research.ulapland.fi/en/publications/character-strengths-in-higher-education-introducing-a-strengths-b

Van Hove, G., De Schauwer, E., Mortier, K., Claes, L., De Munck, K., Verstichele, M. & Thienpondt, L. (2012). Supporting graduate students toward a “pedagogy of hope”: Resisting and redefining traditional notions of disability. Review of Disability Studies, 8(3), 45–54. https://www.rdsjournal.org/index.php/journal/article/view/91

Vidal, J., Diez, G., & Viera, M., J. (2003). Guidance services in Spanish universities. Tertiary Education and Management, 9, 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025879519725

Watts, A., G., & Dent, G. (2002). “Let your fingers do the walking”: The use of telephone helplines in career information and guidance. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 30(1), 17–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/030698880220106492

Watts, A., & Van Esbroeck, R. (2000). New skills for new futures: A comparative review of higher education guidance and counselling services in the European Union. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 22, 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005653018941

Westman, S., Kauttonen, J., Klemetti, A., Korhonen, N., Manninen, M., Mononen, A., Niittymäki, S., & Paananen, H. (2021). Artificial intelligence for career guidance – current requirements and prospects for the future. IAFOR Journal of Education: Technology in Education, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.22492/ije.9.4.03

Zhang, Z. (2016). Lifelong guidance: How guidance and counselling support lifelong learning in the contrasting contexts of China and Denmark. International Review of Education, 62, 627–645. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-016-9594-1