13. Hope Street:

Reimagining learning journeys

Laura Bissell and David Overend

©2025 Laura Bissell and David Overend, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0462.13

Abstract

This chapter explores an artistic exchange project between Glasgow and Mexico City that unfolded during COP26, the 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference. Situated within the framework of creative mobilities, the chapter examines how journeys—both physical and digital—can be reimagined as sites of learning, transformation, and hope. Drawing on the concept of learning journeys, it investigates how participatory and community-based experiences generate meaningful encounters and new ways of knowing. Through co-authored reflections, the chapter emphasises the experimental and generative potential of such exchanges, proposing them as hopeful responses to global challenges like the climate crisis. Ultimately, it argues for the value of creative adventures as a means of opening up alternative pathways for education, collaboration, and sustainable futures.

Keywords: climate; creative adventure; mobilities; performance; revaluing; walking art

Introduction: It begins and ends in hope

We are going on a journey now, for this place, but also for other places.

On this walk, you are invited to look, to listen, and to pause.

You are invited to reflect on the precarity of this place, of everywhere right now.

You are invited to hope.1

On 11th November 2021, we took a walk down Hope Street in Glasgow and returned along Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City. At the same time, over 5000 miles away, several other walkers took the same journey in reverse, walking through their own city and returning imaginatively through another. Both routes set off from and returned to a gold-painted shipping container, which was converted into a small studio space with a live connection for conversation and exchange. The project invited learners and educators in both cities to collaborate in response to global climate concerns at the time of COP26, the 26th United Nations Climate Change conference, which was held at the Scottish Event Campus in Glasgow. Against the backdrop of large-scale political diplomacy, policy and protest, this small-scale journey offered a model of hope for precarious times. It brought together participants from across continents, time zones and cultures, asking how we might travel together through troubled places towards better futures.

In our collaborative work for over a decade with our art-research collective Making Routes, we have convened a network and online resource for researchers and artists who are “on the move”, exploring journeys within their creative practice (Bissell & Overend, 2021). In this time, we have engaged in various forms of artistic research, conducted “performance fieldwork” (Overend, 2023), and been on many creative adventures, to use Brian Massumi’s phrase (2018). Building on this work, the Hope Street Walk (HSW) was programmed by Shared Studios’ Climate Portals at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland.2 Part of a global network of portals including others in Iraq, Palestine, Rwanda, and Uganda, the portals offer a model for learning in the context of dispersed networks of artistic practice. In creating the walks, we collaborated with sound artist Matthew Whiteside and worked in dialogue with Mexican curator Ciela Herce. Our contribution to this collaboration was a new text that took the form of an audio walk through Glasgow. This involved two alternating recorded voices set against an urban soundtrack, which showcased the contemporary city through shifts between historical detail, poetic reflection, and ecological context.

Fig. 13.1 The gold-painted shipping container outside The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland in Glasgow where the Climate Portals festival took place (image by Ingrid Mur, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

In this short chapter, we reflect on HSW as a hopeful journey. The processes of transformation and development experienced in educational, participatory and community contexts are frequently referred to as “learning journeys”. This co-authored piece takes that term literally, asking how physical and digital journeys in specific locations might bring about meaningful and hopeful change. For Sara Ahmed (2016, pp. 46–47), “hope is an investment that the paths we follow will get us somewhere”. This sentiment can be considered as we embark on a new learning journey: the hope is that we will begin at one point of understanding (A) and arrive somewhere different (B) with new insights, experiences and knowledge, gathered along the way. Emma Sharp and her co-authors (Sharp et al., 2021, p. 367) argue that agency leads to hope and that by providing learners with opportunities to be active citizens, they can be empowered by the understanding that “there is not one way to learn, think or do”. This approach encourages an experiential engagement with environmental “wicked” problems such as climate change, in which learners can travel with the problem at their own pace, building an understanding of their relationship to crises and precarity and finding their own agency within challenging environments.

The concept of a “pedagogy of hope” was coined by Paulo Freire (1992) to advocate a liberating, decolonised educational system. Freire (1992, p. 8) claimed that “there is no change without dreams, as there is no dream without hope”. The connection of hope to change is important. We are also influenced by bell hooks (2003), who further developed these ideas in Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope, arguing for democratic and inclusive education in the classroom and beyond. Within the context of HSW, a pedagogy of hope recognises and responds to the immediate environment including the conditions of crises and precarity that we encounter, aiming to cultivate imaginative capabilities and paving the way towards unknown possible futures (Lopez, 2022).

Fig. 13.2 A participant undertakes the Hope Street Walk in Glasgow on 11th November 2021 (image by Ingrid Mur, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

In the lead up to the Climate Portals festival, the impact of the pandemic was palpable; Mexico City was in lockdown, disrupting our collaboration. The process was not smooth, but like with any journey, we learned along the way and we were able to share the work on the evening before the final day of the COP26 conference. HSW attempted to evoke a sense of the specific streets of the two cities while also acknowledging that these sites themselves are microcosms of the wider issues facing humanity. As one of Scotland’s most polluted streets, Hope Street was a symbol for human impact, abandonment, climate change, and precarity. As an approach to learning, the project placed small scale local detail against the large scale “hyperobjects” of climate, economy, and deep time (Morton, 2013). This relationship between situated experience and overwhelming planetary phenomena was a key concern of this project. This encouraged a critical and imaginative engagement with the urban environment that made connections across scale and then facilitated a cross-continental exchange that established a global context for hopeful journeys. The walk enacted a conceptual shift from the tangible and observable features of the route to the issues being addressed at COP26, suggesting that seeds of change could be found between the cracks.

Creative adventures

The buddleia, the butterfly bush, growing out of windows and along ledges, silhouetted on the skyline, whisper of hope.

The pigeons nestled in loft spaces, biding their time, murmur of hope.

The grasses poking through pavements, seeking the sunlight, hum of hope.

The seabirds hovering high above the urban landscape, shriek of hope.3

To emphasise the artistic, experimental and generative qualities of this journey, we refer to “creative adventures” that have the potential to open up new pathways of discovery and understanding. Massumi (2018, p. 99) uses this phrase to argue for a continual process of moving on, of relocating value from fixed states to a “self-driving processual turnover”. Informed by this project of revaluation, HSW asks where we place value and, in the context of decarbonisation, how journeys can be reframed and reimagined for their positive and progressive potential.

As a model for “poor pedagogy” (Masschelein, 2010), HSW heads out into the streets, directing the gaze to the cracks in the parapets where hardy flora grow. This approach aligns with Cal Flyn’s (2022, p. 323) Islands of Abandonment, which rejects the various doomsday scenarios for our planet:

I cannot accept their conclusions. To do so is to abandon hope, to accept the inevitability of a fallen world, a ruinous future. And yet everywhere I have looked, everywhere I have been—places bent and broken, despoiled and desolate, polluted and poisoned—I have found new life springing from the wreckage of the old, life all the stronger and more valuable for its resilience.

It is significant that Flyn observes signs of hope between the cracks, requiring a sensibility to the immediate environment and an ability to look closely at the detail of ostensibly ruinous places. This attention to tiny details and an approach to careful, detailed observation characterised both the Glasgow and Mexico City walks.

The audio walks of the two sites vary considerably, with a sunny daytime Mexico City contrasted with a dark, rainy evening in Glasgow. Nevertheless, some parallels and convergences, as well as differences and departures, emerge through the spoken texts.

Fig. 13.3 A participant of Hope Street Walk passes a bus stop advertising the UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) (image by Ingrid Mur, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

“Glasgow” derives from the Gaelic phrase for “Dear Green Place”; however, there is little green in the grid-like streets of the city, with occasional wildflowers that have self-seeded and taken root on buildings or that poke through gaps in the pavement. In contrast, the audio walk to and around Chapultepec Park, Mexico City’s biggest park (which is “huge, even bigger than Central Park”), notes that “it has been raining a lot, it is green, which makes it even more beautiful”. The Mexico City guide walks along the major thoroughfare leading up to the park gates, while the Glasgow audio draws attention to the little lanes leading off Hope Street, which are described as “the spaces in between, the city’s crevices, its wrinkles”. These differing scales, of wide, open avenues and alleyways squeezed between buildings offer contrasting insights into the architectures and geographies of these specific city locations. Both audio experiences refer to the smells and presence of food outlets: in Mexico City there are parlours selling junk food, Mexican souvenirs, ice cream; and in Glasgow, the restaurants and takeaways tell the stories of “migration, globalisation, fast food and convenience food and lunchbreaks and unrecyclable coffee cups that will end up in landfill”.

This abundance of detail that characterises these concurrent walks has an established precedent in both walking art and education research. Walking promises “a corporeal brushing with the ‘real’ and ‘immediate’ (as well as ‘ever-shifting’)” aspects of its site (Whybrow, 2005, p. 19). The approach recalls Walter Benjamin’s “revalorisation of the everyday and insignificant” (Beaver, 2006, p. 81) in which revaluation of apparently insignificant details represents a way of engaging with the world that recognises the importance of individual material relationships. In HSW, walking is a method of revaluation, in which the city is reframed and recast as a site for hopeful exploration in the context of unprecedented climate change. The suggestion is that we need to adventure creatively in order to locate and interpret the signs of hope that line our streets and circle overhead.

Towards a hopeful pedagogy

We are close now, under the bridge, underneath the arches.

Pause before you cross Argyle Street. Look back up Hope Street, the path you have just walked.

Hope Street is a microcosm: Pollution, abandonment, climate change, precarity.

“And yet, everywhere I have looked…”4

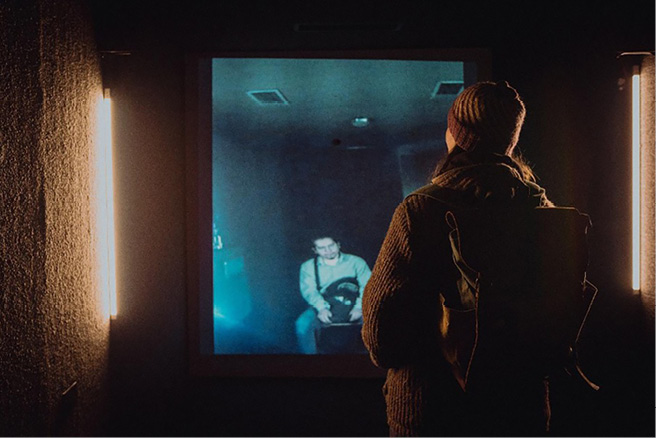

Walking two cities simultaneously places the small scale in broader geo-political and environmental contexts. The walks therefore operate through a displacement of the walker from the academy into the city outside (Masschelein, 2010). The position of the shipping container outside a Higher Education institution emphasised this approach, which literally invited the Glasgow participants to leave the safety and warmth of the building to take a walk through the city. This journey then moves into a mode of imaginative revalorisation—looking again with creativity and hope—through what Massumi (2018, p. 99) refers to as the “processual turnover”, emphasised through the performance of the audio walk. Next, the outward walk is transposed across continents when walkers retrace their steps and attend to another place as they are invited to make connections and comparisons between the cities. Finally, the conversation that takes place in the shared studio (in this case outside the entrance to a Higher Education institution) enacts a return to a place of learning, in which reflection, consolidation, and integration might take place.

Fig. 13.4 The participants of the Glasgow and Mexico City walks meet in the Shared Studio climate portal (image by Ingrid Mur, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

Walking down Hope Street takes us further than might be assumed…

Walk down Hope Street,

And perhaps Hope Street can take us elsewhere.5

HSW was a journey down one street in Glasgow that invited imaginings of other people and places. It encouraged the “art of noticing” (Lowenhaupt Tsing, 2015) and sought a recognition of what can be read as global in the local. It sought to draw attention to one microcosm in an attempt to acknowledge a wider ecology of connections and experiences. Our intention is to develop this enquiry about the positive and progressive potential of journeys within artistic educational contexts. Like Ahmed (2016, pp. 46–47), we believe that “hope is an investment that the paths we follow will get us somewhere”. By mapping the creative potential of journeys onto “learning journeys” in the form of designed curricula, we intend to evaluate the ways in which “creative adventures” can open up new routes, discoveries and knowledges. This is our hope.

Steps towards hope

- Consider setting up artistic exchange projects between institutions and cities to foster creative mobilities. Emphasise the experimental and generative potential of these exchanges as hopeful responses to global challenges like the climate crisis.

- Advocate for “creative adventures” to open up alternative pathways for education, collaboration, and sustainable futures.

- Reimagine physical and digital journeys as sites of learning, transformation, and hope.

- Harness participatory and community-based experiences to generate meaningful encounters and new ways of knowing.

References

Ahmed, S. (2016). Living a feminist life. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11g9836

Beaver, C. (2006). Walter Benjamin’s exegesis of stuff. Epoché: The University of California Journal for the Study of Religion, 24(1), 69–87.

Bissell, L., & Overend, D. (2021). Making routes: Journeys in performance 2010–2020. Triarchy.

Flyn, C. (2022). Islands of abandonment: Nature rebounding in the post-human landscape. Penguin.

Freire, P. (1992). Pedagogy of hope. Continuum.

hooks, b. (2003). Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. Routledge.

Lopez, P. J. (2022). For a pedagogy of hope: Imagining worlds otherwise. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 47(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2022.2155803

Lowenhaupt Tsing, A. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

Masschelein, J. (2010). E-ducating the gaze: The idea of a poor pedagogy. Ethics and Education, 5(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449641003590621

Massumi, B. (2018). 99 theses on the revaluation of value: A postcapitalist manifesto. University of Minnesota Press. https://doi.org/10.5749/9781452958484

Morton, T. (2013). Hyperobjects: Philosophy and ecology after the end of the world. University of Minnesota Press.

Overend, D. (2023). Performance in the field: Interdisciplinary practice-as-research. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-21425-7

Sharp, E. L., Fagan, J., Kah, M., McEntee, M., & Salmond, J. (2021). Hopeful approaches to teaching and learning environmental “wicked problems”. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 45(4), 621–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2021.1900081

Whybrow, N. (2005). Street scenes. Intellect Books.

1 Text from Hope Street Walk by Laura Bissell and David Overend.

2 The Climate Portals festival was led by the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland alongside three creative partners: Shared Studios, Scottish Ballet, and Harrison Parrott. The festival connected with global partners in Bamako, Erbil, Gaza, Nakivale, Mexico City, and Kigali.

3 Text from Hope Street Walk by Laura Bissell and David Overend.

4 Text from Hope Street Walk by Laura Bissell and David Overend.

5 Text from Hope Street Walk by Laura Bissell and David Overend.