23. Embracing compassion: Nonviolent communication for transformative teaching and learning in higher education

Anna Troisi

©2025 Anna Troisi, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0462.23

Abstract

This chapter explores how compassion can be embedded into higher education teaching and learning environments through existing methodologies such as Nonviolent Communication (NVC) and design for change. Drawing on a case study from a Creative Computing undergraduate course, it examines the use of co-inquiry and relational feedback practices to support inclusive, dialogic learning spaces. Rather than introducing new roles or responsibilities, the approach recognises compassion as a teachable and learnable skill that shapes how feedback is communicated, how belonging is cultivated, and how decisions are co-developed. By shifting from reactive fixes to proactive and co-designed strategies, the work illustrates how relational methods can support pedagogical transformation, particularly in contexts marked by marginalisation and difference.

Keywords: nonviolent communication; co-inquiry; relational pedagogy; inclusivity; design for change; compassion; social justice

Embracing compassion: Nonviolent communication for transformative teaching and learning in

Higher Education

Over the years, I have come to recognise the importance of deeply caring for human interaction as a driving force, surpassing the mere pursuit of institutional key performance indicators (KPIs). This is a narrative that intertwines my passion for “Design for change” (Earley, 2023; Grabill et al., 2022), social justice, and compassion with institutional expectations, culminating in a compelling story of peace-making (Troisi, 2021).

In my role as the Course Leader for the BSc Creative Computing at the Creative Computing Institute (University of the Arts London), I have embraced an iterative co-inquiry strategy that actively involves various stakeholders in the educational process. Co-inquiry (Johnston, 2006; Dyer & Löytönen, 2011) represents a relational model for partnering with students that emphasises the importance of shared questions and fosters a strong sense of belonging (Bunting et al., 2020), underpinning the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL)1.

I aimed to cultivate an inclusive, student-empowered curriculum. Initially, the course had only a 50% satisfaction rate, but with collective improvements, we elevated this to 90% in 2020 and sustained it at 81.8% in 2023.

During the COVID-19 pandemic’s onset, my focus was on cultivating a learning space that was both flexible and inclusive, enhancing innovation, engagement, and playfulness. This period underscored the importance of connecting with students, acknowledging their diverse needs shaped by life stages, socioeconomic factors, disabilities, and marginalisation (Rosenberg, 2015). We leveraged compassionate language to better understand and meet these needs, finding it more effective than traditional communication methods.

It is a common practice to oversimplify the relationship between educators and students by assuming that students, as a collective group of learners, share a set of common expectations (Tomlinson & Imbeau, 2023; Wormeli, 2023). Often, we refer to students with the collective term “cohort”.2

Adopting successful practices borrowed from other Higher Education (HE) settings (e.g., actioning feedback, engaging in course committees, surveys etc.) to enhance students’ engagement holds potential, but it may not always yield the desired results. For example, feedback collected by students’ representatives and presented in course committee meetings may sometimes overlook the context, or the feedback may be delivered using language that could potentially elicit resistance from the Course Leader. To truly support the community and empower all of the individuals involved, it is necessary to design changes in the environment and relationships with individuals. In my work with students and staff, I shifted the perspective of teaching enhancement: rather than relying solely on ad-hoc solutions to address individual problems raised by students, I transitioned towards a holistic approach that draws inspiration from shared priorities within the teaching and learning community. The traditional view of “students versus educators” (Freire, 2020; hooks, 2014; Johnston, 2006) needed to be transformed into a more communal opportunity to work together harmoniously.

My interventions with the students were divided into three phases:

- Forging an inclusive environment that enabled co-design, social justice, and inclusion.

- Co-creation of a pedagogy model.

- Implementation of the pedagogy model.

This chapter will focus on the first phase listed above: the creation of an inclusive environment.

Adopting nonviolent communication in the BSc creative computing

In the initial phase, bridging the gap between defensive staff and frustrated students was challenging. To address this, I introduced both groups to Marshall Rosenberg’s Nonviolent Communication (NVC) framework (Rosenberg & Chopra, 2015). Marshall Rosenberg, widely recognised as a pioneer in nonviolent conflict resolution, has dedicated forty years to the development and application of NVC, helping communities, disadvantaged groups, and individuals foster partnership, care, and empathy. NVC focuses on empathising with individual feelings and needs to identify mutually beneficial actions (Rosenberg & Eisler, 2003; Lasater & Lasater, 2022; Morin et al., 2022; Kundu, 2022).

While NVC has been extensively applied in various contexts such as restorative justice (Hopkins, 2012), primary and secondary schools (Jančič & Hus, 2019; Hooper, 2015), and nursing schools (Nosek et al., 2014; Lee & Lee, 2016) with measurable results, recorded examples of its application in HE are limited. This presented an exciting opportunity for exploration and innovation in this area.

Introduction to the students and lecturers

In approaching the implementation of NVC, I highlighted shared interests in personal growth and wellbeing. In an interactive lecture, students used a live polling platform to anonymously share thoughts and pose questions.

During the lecture, I introduced practical tools for communicating effectively and expressing requests that can be heard.

One of the tools presented was the NVC process, which involves four key components:3

- The concrete actions/facts we observe and understand as affecting our wellbeing.

- How we feel in relation to what we observe.

- The needs, values, and desires that create our feelings.

- The concrete actions we request to enrich our lives (Rosenberg & Chopra, 2015).

The essence of this process lies not in the specific words used but in the consciousness of these four components. Students used the four NVC components as guidelines to structure their feedback to lecturers. As 40% of the students involved had English as a second language, I provided printouts listing feelings and needs,4 which not only broadened students’ emotional awareness but also improved their communication skills and English language proficiency for more effective self-expression.

This method fostered an environment conducive to authentic expression and compassionate listening among the students, and we used the lists of feelings and needs for role play, debates, and roundtables.

To further improve the learning environment, I analysed anonymised feedback provided by students, identifying barriers to compassionate communication from educators’ perspectives. Rosenberg (2015) identified certain elements of life-alienating communication, including moralistic judgments, making comparisons, denial of responsibility, and communicating desires as demands.

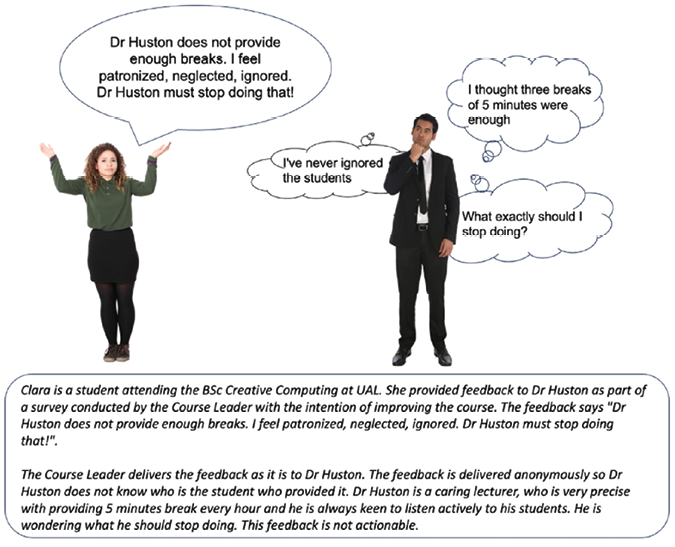

Alienating feedback often triggers defensive reactions from educators who may overlook the human element involved. In Figure 23.1 there is an example of feedback that presents judgemental and life-alienating components.

The word “enough” in Clara’s feedback can be problematic because it lacks specificity. When she states, “Dr. Huston does not provide enough breaks”, it leaves room for interpretation and does not indicate what she believes would be an adequate number of breaks. This lack of specificity could make it difficult for Dr. Huston to understand exactly what Clara is requesting or suggesting. Clara’s use of the phrases “I feel patronised, neglected, ignored” does not refer to inner feelings, as they fall into the category of what are often called “faux feelings” or “pseudo-feelings”. These are not genuine feelings but rather judgements or interpretations of a situation or actions; therefore they are not seen as a concrete observation.

Fig. 23.1 In the vignette, there is an example of feedback given to a lecturer that contains life-alienating connotations. This feedback is not actionable and could provoke negative feelings in the lecturer as well as pushback as a response (image by author, CC BY-NC 4.0).

Following the four steps explained above, students and staff were able to present their requests and assess the likelihood of achieving a win-win solution.

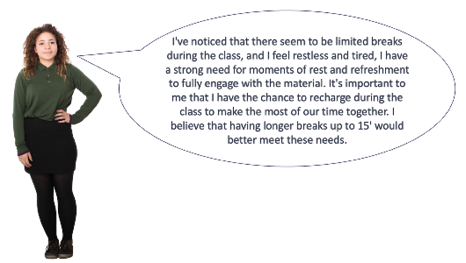

Clara’s example illustrates how to compassionately frame feedback for constructive dialogue (see Figure 23.2).

Fig. 23.2 In this example, Clara learned how to provide compassionate feedback that is actionable (image by author, CC BY-NC 4.0).

With the training provided to the students, they become able to provide compassionate feedback (Troisi, 2022, 11:45) to the lecturers. In the example of Clara, she is using the tool of starting her feedback with the words “I’ve noticed that”. This is a neutral and non-judgemental way to introduce feedback. It suggests that Clara is making an observation rather than passing judgement or blame. This approach encourages open and constructive communication. Clara is also using feelings centred on herself. This is a key aspect of NVC and can significantly contribute to avoiding blame. When Clara expresses her own feelings (such as feeling concerned), she takes ownership of her emotions. This means she acknowledges her emotional response without attributing it to someone else’s actions or intentions. By using “I” statements when expressing feelings, she avoids sounding accusatory. Clara articulates her need for moments of rest and refreshment to fully engage with the material. This focus on needs underscores what is essential for her wellbeing and effective learning. She concludes by making a clear and specific request for longer breaks of up to fifteen minutes. This request is actionable and provides a potential solution to address her needs.

In this example, by structuring her feedback in this way (observation, feelings, needs, request), Clara promotes understanding, empathy, and collaboration. Her approach encourages a productive conversation that can lead to mutually beneficial solutions, all in accordance with NVC principles.

Beyond improving the learning environment, students unexpectedly extended compassionate language to their design practices and debate styles, emphasising social justice and generative disagreement.5

Introduction to the lecturers and course leaders

I streamlined staff involvement by focusing on compassionate feedback techniques in meetings with lecturers and CLs, emphasising the distinction between observation and evaluation in communication.

For instance, saying “you are too precise” conflates observation with evaluation, implying excessive precision from the speaker’s perspective. It reflects a judgement about the person’s behaviour, suggesting that they pay too much attention to detail or accuracy, which may not always be seen as a positive trait depending on the context.

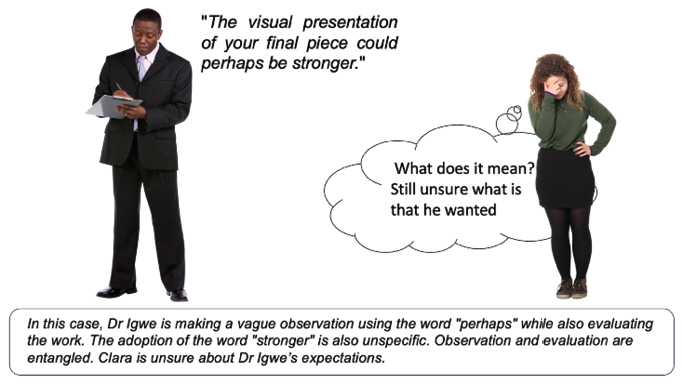

When providing feedback on a student’s work, it is essential to offer constructive evaluation without using judgemental language (Hill et al., 2023, p. 41). Issues can arise when observation and evaluation become entangled, leading to potentially unhelpful or even detrimental feedback.

In the feedback example (Figure 23.3), using the word “perhaps” introduces an element of evaluation and uncertainty. It implies a judgement that the visual presentation could be “stronger” but doesn’t provide a clear, objective observation of what specifically needs improvement. A judgemental tone can detract from a purely neutral and constructive intention. When we judge, we create a disconnection between us and the students. Additionally, students may start to believe that their work should only please the lecturer, which is risky and unjust.

Fig. 23.3 Dr Igwe’s expectations are unclear and the feedback is not actionable by the student (image by author, CC BY-NC 4.0).

It is risky because students who aim to please their tutor may not develop essential decision-making skills. It is unjust because all students, especially those from underrepresented groups or marginalised backgrounds, should have the opportunity to express themselves without feeling the need to please a tutor. This approach fosters their confidence, sense of purpose, and inclusion within the learning community.

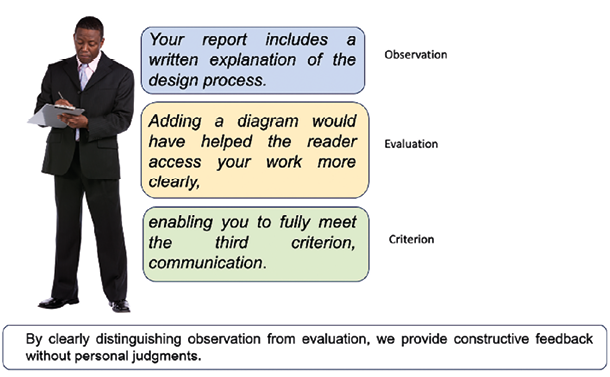

By adhering to NVC principles and offering specific observations detached from evaluations, feedback becomes more effective and promotes empathy and cooperation in communication (see Figure 23.4).

When coaching lecturers, I also explored the importance of acknowledging our feelings while providing feedback. Sometimes, when we encounter work that shows a lack of engagement, frustration arises. This frustration can touch personal areas of confidence related to being an effective lecturer. It is essential to recognise that external factors, such as tiredness or personal issues, can also influence our feedback writing process. By acknowledging our feelings, we can approach feedback with greater empathy and understanding.

Fig. 23.4 Example of compassionate feedback presented without personal judgement (image by author, CC BY-NC 4.0).

My team suggested that we should check that our feedback is specific, neutral, and objective before being released to students. Working with lecturers, we realised that using the first person in feedback can shift the focus away from the student’s work and on to the tutor’s personal expectations. Therefore, we all agreed that feedback should be centred on the student’s piece of work, not the lecturer’s thoughts.

In our pursuit of precision, we also examined the use of specific wordings and their potential effects on students. The outcome of the work done with the lecturers and CLs is summarised in Table 23.1.

Table 23.1 The table shows the main outcome of the workshop I provided to the lecturers, where we analysed feedback given to the students in the previous years and provided guidelines to ourselves.

From empathy to empowerment

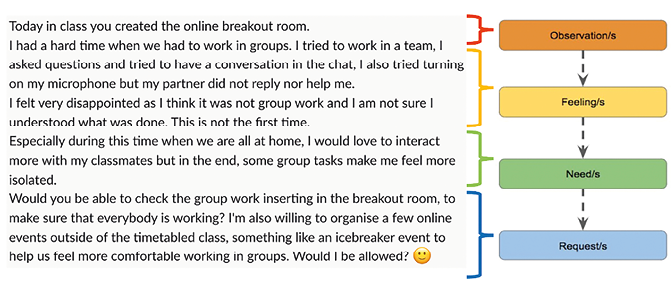

Students and staff, practising compassionate communication, shared a commitment to a compassionate community ethos. This led to increased confidence in formulating requests that were likely to be heard (see example in Figure 23.5).

The impact of this approach on the student community extended to various interconnected areas, including students’ agency in the curriculum and assessment, engagement, inclusion, partnership, employability skills, and wellbeing.

Students were not used to acquiring communication skills as part of their learning at university and some students commented on the importance of being able to be heard in workplaces once they graduated. It was positive to see that they could identify the potential impact of adopting non-judgemental language that would help with employability and general confidence.

Students offered positive feedback, incorporating new keywords such as “needs”, “involved”, “feelings”, “openness”, “friendly environment”, and “closeness”, reflecting their appreciation for staff’s time management and attentiveness to “hear” them. This showed that the students had shifted their approach towards a more empathic, professional, and reflective one.

Fig. 23.5 An example of a student’s feedback given to the CLs around problems in online sessions during the pandemic. The feedback is structured following the NVC communication framework (image by author, CC BY-NC 4.0).

Students became adept at evaluating the course with a professional and constructive approach. Together, we developed a model of delivery known as the “adapted flipped class”, which had significant benefits for student inclusion and accessibility to learning materials. The adoption of NVC helped tailor assessments to accommodate disabled students, who felt more confident and open in sharing their thoughts and ideas; in particular, we provided students with options in terms of the format of the presentation of their work (from presentation to dialogue, to posters, etc.).

The impact on students from marginalised backgrounds across four cohorts was evident in their active participation in debates and on open days, and, most importantly, in their confidence as learners.

![Rounded rectangular white panel with a thin navy outline containing two italicised student quotations in black. The first reads, “a great environment to learn how to collect feedback from peers and communicate [...] to find a suitable resolution. These skills are great to have when moving into the employment sector.” After a large blank space the second quotation reads, “The engagement with our uni became higher each year for me because it became more of a friendly place than just a university.”](image/fig-23-6.png)

Fig. 23.6 Students’ feedback given during their studies (image by author, CC BY-NC 4.0).

Students valued this unique educational approach in a sector often seen as prioritising profit over student growth and well-being. Before concluding I would like to share a student’s note of gratitude, expressing a wish for HE to embrace compassion empowering individuals to be their authentic selves (Figure 23.7).

Fig. 23.7 Student’s feedback after graduation (image by author, CC BY-NC 4.0).

Conclusions

The integration of Nonviolent Communication (NVC) within the BSc Creative Computing course at the Creative Computing Institute has been a testament to the “design for change” philosophy, transitioning us from a conventional pedagogy to one that values empathy and inclusion, and the empowerment of our academic community. By replacing reactive measures with proactive, co-designed strategies, we have witnessed a remarkable enhancement in student experience and initiated a significant cultural transformation.

The theoretical framework of NVC has proved instrumental in transcending educational boundaries, equipping students with compassionate communication skills vital for both personal growth and professional success. This chapter is not only a reflection of a shift in educational practice but also an actionable guide for those committed to fostering environments that prioritise social justice and compassion.

The future of NVC in HE holds many opportunities for nurturing individuals who are resilient, empathetic, and conscious of the social fabric that binds us. It invites educators to see beyond the curriculum, to the heart of teaching as a conduit for creating a just and compassionate society. As I conclude, I encourage educators to consider “design for change” as a beacon in their journey towards transformative teaching and learning, setting in motion a cascade of positive change well beyond the classroom walls.

Steps toward hope

- Recognise compassion as a learnable and teachable skill that can meaningfully shape the culture of teaching and learning in higher education.

- Design inclusive, student-centred learning environments using established methodologies, such as design for change, to support co-design approaches that promote trust, mutual respect, and a shared commitment to compassionate communication across teaching, feedback, and curriculum design.

- Shift from reactive solutions to proactive, collaborative strategies that centre compassion and empower students and staff alike.

References

Bunting, L., Hill, V., Riggs, G., Strayhorn, T., White, D., Stewart, B., Thomas, L., Williams-Baffoe, J., Jethnani, H., & Moody, J. (2020). Why belonging matters [audio podcast episode]. Interrogating spaces. UAL Teaching, Learning and Employability Exchange. https://interrogatingspaces.buzzsprout.com/683798/4795271-belonging-in-online-learning-environments

Dyer, B., & Löytönen, T., 2011. Engaging dialogue: Co-creating communities of collaborative inquiry. Research in Dance Education, 12(3), 295–321.

Earley, R. (2023). Complexity, compassion and courage: Towards a holistic systems model for female-led design for change. In Welcoming differences in textile & clothing and beyond (pp. 18–23). Audasud. https://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/id/eprint/20111/

Freire, P. (2020). Pedagogy of the oppressed. In Toward a sociology of education (pp. 374–386). Routledge.

Grabill, J. T., Gretter, S., & Skogsberg, E. (2022). Design for change in higher education. JHU Press. https://doi.org/10.1353/book.100174

Hill, V., Broadhead, S., Bunting, L., da Costa, L., Currant, N., Greated, M., Hughes, P., Mantho, R., Salines, E., & Stevens, T. (2023). Belonging through assessment: Pipelines of compassion. QAA Collaborative Enhancement Project 2021.

Hooper, L. I. P. (2015). An exploratory study: Non-violent communication strategies for secondary teachers using a quality learning circle approach. University of Canterbury.

hooks, b. (2014). Teaching to transgress. Routledge.

Hopkins, B. (2012). Restorative justice as social justice. Nottingham Law Journal, 21, 121. https://www.iirp.edu/images/pdf/DOPHTU_From_Restorative_Justice_to_Restorative_Culture.pdf

Jančič, P., & Hus, V. (2019). Constructivist approach for creating a non-violent school climate. In S. G. Taukeni (Ed.), Cultivating a culture of nonviolence in early childhood development centers and schools (pp. 147–168). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-7476-7.ch009

Johnston, J. S. (2006). Inquiry and education: John Dewey and the quest for democracy. SUNY Press.

Kundu, V. (2022). Promoting nonviolent communication for a harmonious communication ecosystem. In V. Kundu, Communicative justice in the pluriverse (pp. 43–58). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003316220-4

Lasater, J. H., & Lasater, I. K. (2022). What we say matters: Practicing nonviolent communication. Shambhala Publications.

Lee, M., & Lee, S. B. (2016). Effects of nonviolent communication (NVC) program consist of communication ability, relationship and anger in nurses. Journal of the Korea Society of Computer and Information, 21(10), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.9708/jksci.2016.21.10.085

Morin, J., Gill, R., & Leu, L. (2022). Nonviolent communication toolkit for facilitators: Interactive activities and awareness exercises based on 18 key concepts for the development of NVC skills and Consciousness. PuddleDancer Press.

Nosek, M., Gifford, E. J., & Kober, B. (2014). Nonviolent communication training increases empathy in baccalaureate nursing students: A mixed method study. Journal of Nursing Education, 53(11), 611–615. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v4n10p1

Potter, M. K., & Kustra, E. D. (2011). The relationship between scholarly teaching and SoTL: Models, distinctions, and clarifications. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 5(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2011.050123

Rosenberg, M. B., & Chopra, D. (2015). Nonviolent communication: A language of life: Life-changing tools for healthy relationships. PuddleDancer Press.

Rosenberg, M. B., & Eisler, R. (2003). Life-enriching education: Nonviolent communication helps schools improve performance, reduce conflict, and enhance relationships. PuddleDancer Press.

Tomlinson, C. A., & Imbeau, M. B. (2023). Leading and managing a differentiated classroom. Ascd.

Wormeli, R. (2023). Fair isn’t always equal: Assessment & grading in the differentiated classroom. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781032681122

Troisi, A. (2021). Teaching peace: Place-making for digital curricula. In Inclusive policy lab education and digital skills: A conversation event. The Open University. https://doi.org/10.21954/ou.rd.17212997.v1

Troisi, A. (2022). Non-violent communication: Opinion and evaluation [audio podcast episode segment]. In L. Bunting, V. Hill, & G. Riggs (Producers), Interrogating spaces (11:45). UAL Teaching, Learning and Employability Exchange. https://interrogatingspaces.buzzsprout.com/683798/11480939-compassionate-feedback

1 SoTL is a growing field in post-secondary education that uses systematic, deliberate, and methodological inquiry into teaching (behaviours/practices, attitudes, and values) to improve student learning (Potter & Kustra, 2011).

2 The use of the word “cohort” to refer to a student year group draws on military language. In ancient times, a cohort denoted a military unit within a Roman legion. Over time, the term transitioned into English, where it was used in translations and writings about Roman history. Gradually, “cohort” evolved to encompass any body of troops and later extended to signify any group of individuals sharing common characteristics. By employing military language to describe students in an educational context, there is a concern that it oversimplifies the relationship between students and educators, implying that they share a homogenous set of expectations. In reality, each student is a unique individual with diverse needs, experiences, and perspectives, which should be acknowledged and respected in fostering an inclusive and compassionate learning environment.

3 It is important to mention that the four key components are not meant to be addressed in a specific order and the practice will give space to move back and forward from one to another to explore the best way to investigate personal views and feelings and communicate with compassion. However, when I started working with the students, I helped them to follow the order indicated. I noticed that having a precise framework helped, in particular, students with learning differences to feel more confident. After practising, the students were able to detach from the specific order and make of the framework something more fluid that was also applicable to relationships outside the university environment.

4 A variety of comprehensive resources detailing feelings and needs for the practice of NVC are accessible online; for our purposes, I’ve opted to employ the compilations found at https://groktheworld.com/

5 The term “generative disagreement” refers to a form of disagreement that is productive, leading to growth and mutual understanding rather than conflict or stagnation.