29. Learning vs education:

A view beyond the divide

Akitav Sharma

©2025 Akitav Sharma, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0462.29

Abstract

This chapter offers a critical examination of institutionalised education and proposes a transformative model that re-centres the personal, contextual nature of learning. It contrasts the rigid, standardised practices of traditional systems with the lived experiences of learners, revealing how socio-cultural and economic structures often reduce education to capital accumulation, thereby deepening inequality. In response, the chapter introduces the concept of a ‘Curriculum for Innovation’ (CfI), a learner-centred framework grounded in principles of meaning-making, knowledge construction, and autonomy. CfI reimagines curriculum design as adaptable and responsive to individual contexts, positioning educators as co-constructors of learning rather than mere content deliverers. This approach seeks to bridge the divide between education and learning, fostering more equitable, meaningful, and innovative educational experiences.

Keywords: institutionalised education; personalised learning; personalised assessments; curriculum for innovation (CfI); learner autonomy; critical thinking; socio-emotional learning; life-long learning

Introduction

Learning is personal. No matter the content, context, or format of learning, it impacts the individual learner personally and within their lived context. Education, for the context of this chapter, is a product of complex and dynamic socio-cultural interactions and the selective utility embodied within certain ideas and foci of labour (human effort). These interactions lend credence to the content that is “worthy of being taught”, and thus, its inclusion within the curriculum.

Institutionalised education is a (generally) sequential process of exposure to educational activities that is offered by institutions that have any style/type of benchmark gatekeeping criteria to limit and regulate learner engagement. This education is often standardised and rarely acknowledges the deeply personal nature of learning (Apple, 1990; Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977; Bernstein, 1971; Lorde, 1984; Hill Collins, 1990).

Thus, to make sense to an individual and assist the individual in constructing a coherent and meaningful life narrative (Dewey, 1938; Freire, 1970; Vygotsky, 1978; Gilligan, 1982; Lorde, 1984), education must offer whatever is deemed “worth teaching” in a form and style that makes it “worth learning”. Thus, this chapter makes the case for redefining education as an integrated process of personally adapted and contextually relevant learning experiences.

The status quo

In its prevailing form, institutionalised education serves as a matrix of opportunities. At every level of the sequential process of education, institutions offer completion certificates, and for every benchmarked milestone of achievement an “equivalent” degree is conferred. With each level of completion (elementary, high school, undergraduate, postgraduate, PhD, post-doctoral…) and proficiency (grades), a concomitant sequence of opportunities are “presented” to the learner. If one desires, one may seek a job right after elementary school or high school, contingent upon what is offered. However, within the “real world” outside the classroom (the same real world that informs the creation and collation of the curriculum and its goals) opportunities are not fairly offered simply on the basis of educational achievement. Moreover, educational achievement—especially within the institutionalised context—is not solely dependent on the learner’s performance.

Education and the learner are constructed and exist within a stratified world order, and as such are both guided and constrained by the “rules of the world”. One of these rules is that access to opportunities is predominantly mediated by one’s existing forms of capital—be they cultural, social, or material (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988; Putnam, 2000; Hill Collins, 1990; hooks, 1994).

When coupled with real-world aspirations of the learners within an institutional context, levels of completion or achievement (proficiency) are often tied in with their real world impacts vis-a-vis the accumulation or possession (rarely, embodiment) of capital, whether through institutionalised credentials like degrees or diplomas or via technical training leading to information capital (Bowles & Gintis, 1976; Darling-Hammond, 2000; Lareau, 1987).

Thus, a stratified world offers stratified learning experiences, which, in turn, create stratified and standardised results. As a result, the socio-economic factors that should guide the educational focus often serve as the driving force behind it (Bowles & Gintis, 1976; Willis, 1977; Weiler, 1991). This further separates institutionalised education from its personal impact and leads to education becoming predominantly quantitative, assessing merit or the possession of “legitimate” knowledge rather than a nuanced understanding of human potential (Tilly, 1998; Freire, 1970; Noddings, 1984).

Capital accumulation has definite and tangible merits and serves as a near irreplaceable form of incentive for continued educational engagement. However, reducing all education to just this mechanistic process undermines its holistic impact (Nussbaum, 1997; Gilligan, 1982; Spivak, 1988). Further complications within the educational processes (and oversimplification of educational outcomes as discrete capital outcomes) arise when educational practices are implemented through large-scale, centralised mechanisms. In this (current and prevalent) scenario, institutionalised education paradoxically perpetuates the social inequities it aims to mitigate, especially when it operates outside the contextual needs of learners (Apple, 1990; Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977; Westheimer & Kahne, 2004; Lorde, 1984; Hill Collins, 1990; Fine, 1991). The problem statement(s), thus, can be articulated as such.

What is worth learning? What is worth teaching? Who decides the worth?

If we look to educational experiences (especially those offered by degree granting institutions), we can conceive of education that leads beyond mere capital acquisition/possession. Education can become (for each learner) a facilitating process of assimilation and embodiment of all forms of capital, a transformative pathway for individuals to derive or construct meaning for themselves (Freire, 1970; Mezirow, 1991; Vygotsky, 1978; hooks, 1994).

A way forward: “Curriculum for Innovation” (CfI)

Institutionalised education, especially as mandated and implemented through centralised policy decisions, is often far removed from learners’ lives and contexts, oversimplifies learning into measurable/standardised outcomes, reduces educational outcomes to a matter of capital acquisition, and, in almost all instances, exacerbates the social inequalities it’s meant to alleviate (Apple, 1990; Bourdieu, 1986; Bowles & Gintis, 1976; Freire, 1970).

This section outlines a curriculum design that is rooted in many diverse theories and bodies of human knowledge. It is a single attempt to generate a cohesive epistemological framework to offer learning experiences that are personally adaptable and contextually relevant. As such, through its demonstration, it implies that many other frameworks can be created that are relevant to any other contexts and derive from bodies of knowledge that are considered ‘worthy’ within those contexts.

The following epistemological framework is built upon a few axioms.

Axiom 1) Meaning is central to human life (and the narratives of selfhood).

Axiom 2) Meaning can be constructed.

Axiom 3) Agency is fundamental to the construction of meaning.

Axiom 4) Learning is Personal.

Axiom 5) Education can be personalised.

A few inferences that can be drawn from these axioms and previously established ideas are presented below.

Inference 1) Any process or activity that engages the individual/ a collective, especially when crafting/imbibing narratives, must be meaningful for the actor/participants.

Inference 2) The utility/value of every lived experience can be correlated to the act of meaning. If meaning can be obtained, all engagements can be made meaningful. Through active cognition, the learner can be guided towards the acquisition/construction of a ‘personal’ meaning.

Inference 3) If the cognitive engagement with an activity or process can be reinforced by metacognitive inquiry and acknowledgement of a ‘personal meaning’, then the activity/process becomes a learning activity/process.

Inference 4) The person (and their personhood) is a fundamental variable within the learning-teaching process. As the person changes (change in one person over time/ when considering different people), so do the teaching-learning requirements.

Inference 5) Educational processes are not equivalent to learning processes until they have been personalised and adapted to the individual learner’s context and lived experiences.

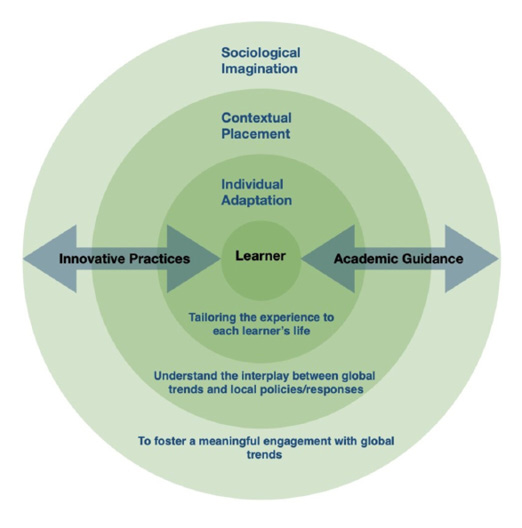

Fig. 29.1 Cfl framework (Curriculum for Innovation, image by author, 2022, CC BY-NC 4.0 (image may not be used for training machine learning or artificial intelligence systems)).

Combining all these inferences, one can design broad epistemological frameworks to model curricular designs that are personally adapted and contextually relevant. As a demonstration, one such epistemological framework (CfI) and a derived curricular design has been presented here. The CfI framework (visualised as a mind-map herein) aspires to stimulate a deeper engagement between the learner and their world, while also scaffolding it within the zeitgeist. The purpose is not merely to impart knowledge but to foster personally meaningful interactions that enrich students’ understanding of their world and themselves. Within this framework, education transitions from being an institutionalised outcome driven process to a dynamic ecosystem where students are active constructors of knowledge (Freire, 1970; Vygotsky, 1978; Lave & Wenger, 1991).

The role of the teacher/facilitator

Educators, in this milieu, are not mere instructors but facilitators, collaborators, and co-learners, harmonising the symbiotic exchange of ideas and knowledge (Dewey, 1938; hooks, 1994; Noddings, 1984). The role evolves to providing short expert introductions to core disciplinary ideas upon which activities are designed to foster individual and collaborative learning through active participation.

Apropos, educators must be trained to view learning as a multifaceted personal process that encompasses individual (cognitive and metacognitive) and collective activities. Learning involves a self-structured progression through the development and deployment of self-efficacy beliefs, and as such becomes a self-directed journey. The educator, thus, can be freed from clerical assessments of learner performance, if we design assessments that are personal and introspective and aligned with each learner’s unique journey and particular needs (Mezirow, 1991; Darling-Hammond, 2000).

Assessments

Learner engagement and performance can (and must) be judged. However, the standardisation of assessment outcomes as the norm is a result of logistical limitations instead of a heuristic classification/design. To judge engagement, learners can be guided through personalised metacognitive prompts to elicit their reactions, reflections and meaning-making processes. As a standard form of assessment, contextualised individual and group “case-based learning exercises” (CBLE) can be crafted by each learner on the basis of their metacognitive responses. This two-part assessment design can offer a deeper view into individual learning processes and offer the degree of personalisation that is missing from the prevalent forms and models of assessment. (i) Personalised metacognitive prompts and (ii) CBLE based upon the learner’s metacognitive responses.

To further check for proficiency for specialised disciplinary engagements, broad based, critical thinking enabled, tests can be designed and deployed for groups of students.

Content delivery/format

Anticipated Universal Acceptance (instead of retrospective fixes for improved inclusion and diversity) is inherent within the curricular design. To maximise our utilisation of all new-age technologies, the content can be offered in diverse formats and styles, ranging from texts, audiobooks, and gamified digital media to recorded/interactive lectures. The framework, thus, expands the nature and format of the educational experience, ensuring it is more reflective of learners’ varied needs and personal contexts (Hill Collins, 1990; Lorde, 1984; Nussbaum, 1997).

Emphasised within this design are crucial future-ready skills: critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, digital literacy, adaptability, collaboration, contextual awareness, self-awareness, and socio-emotional learning. Technology is employed both as a learning tool and a subject to be mastered, enabling learning to extend beyond the classroom walls (Freeman et al., 2017; Prensky, 2001).

Intended learning outcomes

By anchoring the learning outcomes to real-world relevance, the curriculum can guide learners in drawing connections between education and their personal lives, thus enriching their understanding of both (Bowles & Gintis, 1976; Willis, 1977; Weiler, 1991).

In order to classify these learning outcomes in the analytic traditions, we define sociological imagination, contextual engagement, innovative practices and behaviours, and personalised academic guidance as the key segments within which the curricular knowledge is transacted.

Why sociological imagination?

In an era of accelerating change, how we perceive the world around us—our worldview—shapes not only our individual futures but also the future of our communities. With a focus on fostering deep engagement with global trends and hyper-localised/personal contexts, learners can be nudged towards the crafting of personal narratives that enable them to “make sense” of the world around them. This view, as studied in sociology as the sociological imagination, is a truly worthy outcome of education. If a learner can make sense of the deep socio-cultural/economic/political undercurrents that operate globally, then this outcome of the education can be assumed achieved.

This can be greatly facilitated by a steady introduction to concepts from Humanities, Social and Physical Sciences (or simply put, from all branches of human knowledge and thought). A suggestive list of topics can possibly include key economic theories and debates, such as universal basic income, social economics, and macroeconomic theories to educate learners about market theories and the interplay of capital in shaping societies.

Equally vital are ideas from social sciences like social stratification and opportunities (the interplay of capital, merit, and upward socio-economic mobility), human geography, and ideas from culture and gender studies. These can help students develop a more comprehensive understanding of the various social dynamics that impact their lives.

Sociologically informed, case-based learning exercises can offer an integrated view of methods to contextualise abstract theories within real-world scenarios, providing a bridge between academic knowledge and its practical applications.

Why contextual placement?

While understanding that some global forces and causal relationships can add a worldly meaning to learning experiences, this meaning does transfer to the learner through their uniquely specialised context. The emphasis is on helping students identify how global trends specifically impact their lives. It also seeks to help them understand how these global trends interact with local policies and responses, ranging from the national to neighbourhood levels. For example, an ongoing geo-political conflict might be local for some learners while for others it may be a global trigger impacting fuel costs or instigating local acts of civil disobedience that might result in state-sponsored crackdowns.

This can be greatly facilitated by a steady introduction to concepts from humanities, and social and physical sciences (or simply put, from all branches of human knowledge and thought). Specifically, policy analysis as a way to understand governance and control is crucial. Students can explore how global trends impact local policies that shape the larger socio-economic context of their lives. Moreover, if institutionalised education is to accommodate the learner’s needs, it must also accommodate the leaner’s understanding of the process itself. Hence, a bird’s eye view of institutional education, focusing on its structure, goals, and socio-cultural influences is necessitated. This will further assist learners in understanding the dynamics of capital returns of institutionalised education.

The final necessary exposure is that of the process of cognition itself, especially how it is impacted by the ecological systems within which the learner exists. This entails recognising cognitive development as an active process, to which end the curriculum incorporates the study of proximal processes and explores how various forms of capital possession affect learning outcomes.

Why individual adaptation?

While the learner can be guided towards making sense of the world, and their unique placement within their neighbourhoods/localities, they have to be sufficiently empowered and skilled to craft their selfhood (self-authorship). This can be achieved by offering directed metacognitive prompts to assess their personal values (virtues), behavioural trends, and degree of capital possession and embodiment. These exercises help generate a comprehensive learner profile, providing insights into each student’s unique learning needs. With these insights, each learner can develop self-efficacy beliefs and engage meaningfully with learning (and life).

Why learn innovative practices and behaviours?

The corpus of human knowledge has grown and fragmented into many disciplines over the last five millennia. As such it is practically impossible for any one individual to possess all of what humans have uncovered/invented/ learnt. However, a broad reading of history coupled with topics from sociology, psychology, and organisational management can offer learners an opportunity to understand and personalise “innovation”. This involves promoting social innovations, technological advancements, and collaborative engagements among students. Students are also encouraged to create their own case studies, offering practical applications for theoretical learning.

Alongside learner exposure, the curriculum also promotes institutional innovative practices that can foster individual innovation. These include building a learning organisation, fostering teacher professional development (for the educators and facilitators), and creating a fearless organisation that encourages out-of-the-box thinking.

Why personalised academic guidance?

Once the learner begins the personal process of meaning-making (“assessed” through metacognitive prompts and CBLE design), they can be guided towards the process of “best-fit” decision-making. This process is the penultimate step of educational achievement. With frequent and scaffolded (including metacognitive) exposure to activities across spectrums of research and development, policy analysis and action, entrepreneurial ventures, organisational management, or higher education routes, learners can be assisted in making best-fit choices for themselves.

Education is greater than the sum of its parts!

If the process of learning is transacted effectively, then one can reason that the one true product of the process will be a love of, fascination with, and excitement about (or the very least an absence of aversion to) learning. If this outcome can be achieved then the educational processes won’t have failed the learner. The curriculum outlined above builds on the importance of continuous learning by offering avenues for a personally adapted and contextually relevant assessment of skills/values/behaviours/capital.

Conclusion

To encapsulate, the Curriculum for Innovation embodies a holistic, student-focused philosophy of education, a dedication to diversity and personal evolution. By offering a diverse, adaptable curriculum that fosters deep personal engagement with complex, interconnected global trends, this educational model aims to prepare students for a future characterised by continuous change. It goes beyond academic knowledge, focusing on the development of innovative behaviours, adaptability, and individualised guidance, creating lifelong learners capable of navigating the complexities of the modern world.

Author’s remarks

The ideas presented are not just “thought experiments”. Over the last four years, segments of the curricular design have been implemented for learners aged 5–27 years, pursuing a wildly wide variety of disciplines and learning outcomes. They were all successful in achieving their desired learning outcomes, even though none of those outcomes were causally chased. They consistently scored in the top 10% of their respective institutional cohorts, and learnt to manage their expectations and engagement through autonomous meaningful engagement with the content matter, demonstrating the sprouting of self-efficacy beliefs. This classroom programme was highly resource intensive, and fundamentally impossible for one facilitator to manage with class sizes exceeding ten learners. A case could be made for increased facilitators per class, but effective CBLE management necessitated fragmenting the whole into smaller learning groups of ten to twelve learners each for every facilitator present.

However, recent events (the development of open-source LLMs and generative AI tools) have made it possible to replicate and concurrently deploy this epistemological/curricular model to a much larger learner base, tailored to each context, culture, or linguistic paradigm. All the tools necessary for such an ambitious project are available, although disjointed as “tech products”. It is a matter of adapting/repurposing them to facilitate learning and augment general human intelligence (especially before we unleash artificial intelligence upon ourselves) by fostering learner autonomy and self-efficacy beliefs. The development of this specialised “learning companion” is underway.

Steps toward hope

- Evaluate current educational paradigms to identify gaps between learning and education.

- Implement personalised teaching methods that cater to individual learning styles.

- Develop strategies to address socio-cultural and economic influences on education.

- Shift to a Curriculum for Innovation (CfI) that offers personalised, contextually relevant learning experiences.

- Encourage educators to act as facilitators of knowledge construction rather than focusing solely on content delivery and assessment.

References

Apple, M. (1990). Ideology and curriculum. Teachers College Press.

Anyon, J. (1980). Social class and the hidden curriculum of work. Journal of Education, 162(1), 67–92.

Bernstein, B. (1971). Class, codes and control. Routledge.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139–148.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life. Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241–258). Greenwood Press.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1977). Reproduction in education, society and culture. Sage.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Harvard University Press.

Collins, P. H. (2000). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v8n1.2000

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Kappa Delta Pi.

Fine, M. (1991). Framing dropouts: Notes on the politics of an urban public high school. SUNY Press.

Freeman, A., Adams Becker, S., Cummins, M., Davis, A., & Hall Giesinger, C. (2017). NMC/CoSN Horizon Report: 2017 K–12 Edition. The New Media Consortium.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

Gillborn, D. (2005). Education policy as an act of white supremacy: Whiteness, critical race theory and education reform. Journal of Education Policy, 20(4), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v8n1.2000

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice. Harvard University Press.

Giroux, H. (1988). Teachers as intellectuals: Toward a critical pedagogy of learning. Bergin & Garvey.

Harding, S. (1991). Whose science? Whose knowledge? Thinking from women’s lives. Cornell University Press.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling society. Harper & Row.

Lareau, A. (1987). Social class differences in family-school relationships: The importance of cultural capital. Sociology of Education, 60(2), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v8n1.2000

Lather, P. (1991). Getting smart: Feminist research and pedagogy with/in the postmodern. Routledge.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Lorde, A. (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and speeches. Crossing Press, 1984.

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass.

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. University of California Press.

Nussbaum, M. C. (1997). Cultivating humanity: A classical defense of reform in liberal education. Harvard University Press.

Oakes, J. (1985). Keeping track: How schools structure inequality. Yale University Press.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(1), 1–6

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford University Press.

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? Macmillan.

Tilly, C. (1998). Durable inequality. University of California Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Weiler, K. (1991). Freire and a feminist pedagogy of difference. Harvard Educational Review, 61(4), 449–475. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.61.4.a102265jl68rju84

Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 237–269. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v8n1.2000

Willis, P. (1977). Learning to labor: How working-class kids get working-class jobs. Columbia University Press.