40. Food for thought:

Pandemic hope

Hilda Mary Mulrooney

©2025 Hilda Mary Mulrooney, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0462.40

Abstract

The pandemic simultaneously exposed long-standing weaknesses and sparked necessary innovations in education. As teaching and learning shifted online, many staff and students experienced a diminished sense of belonging, highlighting the fundamental importance of human relationships in educational environments. Food, with its multifaceted personal and cultural significance, emerged as a powerful tool for fostering connection and community. During the pandemic, food-related projects helped enhance belonging among staff and students, illustrating how shared experiences around food can build stronger interpersonal bonds and deepen cultural understanding. This chapter explores how food can continue to serve as a meaningful route to strengthen connections and cultivate a more inclusive and supportive educational experience.

Keywords: pandemic; connections; belonging; food; hope; relationships

Introduction

At a dizzying speed during the pandemic, the world closed down. By mid-April 2020, an estimated 94% of learners in two hundred countries worldwide were affected by the closure of their educational institutions (UN, 2020). Young people were sentenced to classes online for an unknown length of time to protect those who were vulnerable. The world waited for a vaccine, but in the meantime, Higher Education had to continue to function. Most universities were ill-prepared to switch teaching and learning to online provision almost overnight. Lack of infrastructure and investment in digital connectivity were exposed (JISC & Emerge Education, 2022). Staff, many of whom felt ill-equipped to do so, were suddenly required to deliver material designed for the classroom online, often with little preparation, and even less confidence (JISC, 2021; Iivari et al., 2020). Working from bedrooms, dining tables, and kitchens, with members of their own families wandering in and out of shot and often simultaneously home-schooling or caring for others, Higher Education practitioners stepped up to the plate and did their best to support their students. This was at great cost; the requirement to keep going caused many academics to report a dramatic increase in their working hours (Wray & Kinman, 2021; JISC, 2021; Watermeyer et al., 2020; Longhurst et al., 2020).

In the myriad of arguments about whether and how students should be compensated for the disruption to their education (e.g., Weale, 2023; OIA, 2021, 2022, 2023), there has been little thanks, recognition, or reward for those lecturers, academic, technical and support staff who worked incredibly long hours to make this provision available (Watermeyer et al., 2021). Often lacking adequate facilities and even equipment to make the content optimal (JISC, 2021), they did their best, while simultaneously struggling with the same unknowns as their students. If they had not done so, students would have suffered even more disruption, since education would have closed down completely. This fact has been omitted from discussions about the impact on students.

Despite the difficulties it caused, the pandemic also had positive impacts within Higher Education. While exposing weaknesses—including digital poverty affecting staff as well as students—it allowed and even demanded rapid innovation, showing how things could be done differently. The digital skills of staff and students increased rapidly due to the move to online teaching, and the acquisition of such digital skills is essential for students (JISC, 2021; Vickerstaff, 2023). The use of technology within Higher Education has many advantages. The digital gains of the pandemic could be built on to shape future education, focusing on how students learn rather than solely the teaching methods used, and ensuring that the learning is designed for digital delivery (JISC, 2020; JISC & Emerge Education, 2022). The pandemic allowed traditional institutions an alluring glimpse of what might be possible, with time, with planning, with the right equipment, support and training for staff, and having prepared students and managed their expectations.

The need to connect

Whether learning is online, face-to-face or a blend of the two, something the pandemic really highlighted was the need for students and staff to connect and form relationships with each other and their peers (Curnock Cook, 2021). Sense of belonging fell throughout the pandemic in both groups (Gopalan et al., 2022; Tice et al., 2021; Mulrooney & Kelly, 2020), although this was not universal. For commuter students, those with a disability, those in paid work, and for some parents and carers, sense of belonging may have increased due to the improved accessibility and flexibility of online provision (Curnock Cook & Dunn, 2022). Given our understanding that developing a sense of belonging and connection includes four elements, namely social, academic, surroundings and personal space (Ahn & Davis, 2019), it is easy to see how the pandemic could negatively affect belonging. Lockdowns meant physical separation from one another while forming relationships online was more difficult. Students usually had their cameras off, often to preserve bandwidth, but the result for staff was the feeling that they were teaching “into the void”, faced with rows of anonymous avatars on screen and with no body language to read. Reduced interaction and engagement of students online was a major concern for staff (JISC, 2021). Our research within our large, post-1992 institution with a strong widening participation focus found that the first lockdown reduced the sense of belonging in staff and students, with both groups identifying physical presence on campus as important to developing this (Mulrooney & Kelly, 2020). Follow-up research suggested that staff and students had concerns about continued online teaching and learning and its impact on their relationships with each other (Abu et al., 2021). The question was, what to do about it?

Building connections online—the potential of food

How could connections be built online? While the IT and pedagogy staff worked hard to show us the potential of different programmes and teaching approaches, I thought about food. I am a nutritionist and dietitian by background, so my interest was not limited to a desire for the next meal. Food was shown to be a source of comfort to many during the pandemic (Lasko-Skinner & Sweetland, 2021); not surprising when everything else in our lives had changed. I thought about the fact that everyone has to eat, so food is both universal and intensely personal. We all experience food differently—think of foods you like, and your associations with them. They are unlikely to be exactly the same for those around you. Food has multiple meanings for people—it is not simply a means of transmitting calories and nutrients to the body. What we eat sends messages about who we are; our values, our experiences, our cultures, and even our religious and personal beliefs (Lupton 1994; Rozin, 2005; Williams et al., 2012). Food is a physical necessity but also acts as a metaphor—connecting us to people, places and times, demonstrating friendship, welcome and acceptance, and highlighting personal and cultural identities.

Food to build a sense of belonging

In the first lockdown, I decided to try using food to build a sense of belonging among staff and students at my institution. I invited them to share with me recipes that were personally meaningful to them, and to tell me why they mattered. This project was called Cultural Food Stories. I created an online questionnaire, which included statements derived from the literature on belonging (Yorke, 2016; Ribera et al., 2017) and asked participants to rate them, using a five-point Likert rating scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. Participants were asked for basic demographic data (e.g., age range, gender, disability status), how long they had been at the university, and whether they were staff or student members. They were also asked whether taking part in the project had affected their sense of belonging. Staff and students were invited to participate online via their university email addresses. A total of 45 participants (28 students, 15 staff and 2 who did not state which group they belonged to) took part, 12 of whom were also interviewed. The majority (73.8%) said that taking part had increased their sense of belonging, none stated that it had decreased it, and this was not affected by demographic characteristics (Mulrooney, 2021). A total of 49 recipes and stories were shared, and I created an online recipe book with the stories, the recipes and the three words participants used to describe what food meant to them.

In the academic year 2021–22, I again used food to engage staff and students, this time exploring the values that food-related images chosen by participants exposed. I invited submissions of food-related images, together with why those images had been chosen and what made them meaningful to the participants. The images could be photographs taken by participants, or images they had found online or in magazines. The only criteria were that the images had to relate in some way to the food, and no identifiable individual could be included. Demographic information was collected to see if this affected responses. Participants again rated their level of agreement with a series of statements related to belonging (Yorke, 2016; Gehlbach, 2015; Gehlbach & Brinkworth, 2011) and food-related statements, using the same five-point Likert rating scale as previously. They also assessed whether their participation had affected their sense of belonging at the university. Images and stories were shared by 90 participants (23 staff and 67 students), 13 of whom were also interviewed. The sense of belonging at the institution was increased in 39.0% of staff and 49.3% of students, and decreased in none (Wojadzis & Mulrooney, 2023).

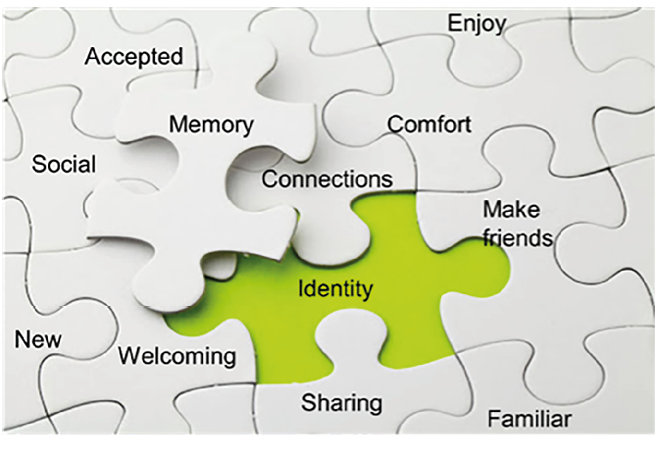

Both projects aimed to enhance the sense of belonging in staff and students, and both did. Intensely personal and moving stories were shared. Themes common to both projects centred around food as a link to people, places and occasions, which was particularly poignant in the early part of the pandemic when people were physically separated. For example, the recipes shared were chosen in memory of family occasions (e.g., parties, weddings), a honeymoon trip, meals shared with specific people like grandparents and parents, and foods that linked participants to their countries of origin, none of which could be visited at that time. The multiple roles of the food identified in the work, many of which related directly or indirectly to belonging and connection, are shown in Figure 40.1:

Fig. 40.1 Key themes identified from interviews in Cultural Food Stories (Mulrooney, 2021, CC BY-NC 4.0).

An i-poem (Gilligan et al., 2003), written from the transcript of one participant in the Cultural Food Stories project, demonstrates the role of food in the pandemic and how it evoked memories of specific people, emotions, culture and belonging:

…food in my culture,

Feel like you belong to that group and this joy,

Those I cannot see at this time,

Reminds me of her.

The projects were carried out at very different times in a period of intense global, national and individual change. Cultural Food Stories was carried out in the first lockdown, when we could only leave our homes once a day and go only short distances. No one could meet family or friends other than those we lived with. The greater sense of belonging induced by taking part in the project was unsurprising in that context, and the importance of food as a mechanism of connecting with others was highlighted. The second project, carried out a year later, was when the vaccine had been developed and the world was slowly moving back towards “normal”. Able to leave home and meet albeit still with precautions and avoiding large groups, Higher Education institutions had opened again. In my own university, small classes were held on campus while large group teaching remained online, so while better than the previous year, the situation was still unusual and the standard crowds on campus were absent. Many participants spoke of how they had adapted their usual food-related customs to the pandemic. Rather than celebrating important religious or cultural events by bringing food to each other’s homes and eating together, they prepared the dishes and ate together online, connected to each other through the ether by their shared values and their food customs, but unable to be physically together. This speaks to our enormous human capacity to adapt, to accommodate, and to innovate. It also speaks to the multiple values of food in our lives, and I would argue, the potential to use food within education to enhance and explore belonging.

How else can food be used to enhance belonging in Higher Education?

There are many ways to do this, some involving actual food. Opportunities to eat together, to have a potluck where individuals bring their own dishes to an event to share, may be constrained by health and safety concerns. If they are not, they offer valuable opportunities to talk together about food, and to discuss and understand other cultures and food beliefs. In a diverse and multicultural institution such as my own, this is invaluable. Even if this is not possible, the sorts of projects I carried out are possible and no special nutritional knowledge is required. Developing institutional cookbooks gives an insight into the diversity of students and staff at an institution, but also demonstrates an interest in knowing what matters to them. My suspicion is that it is being asked about something that matters personally to individuals, that contributes to their sense of belonging, suggests that institutions have an interest in people as individuals, and this matters to them. This is illustrated by quotes from some of the participants:

It is very special to take part in a project that involves both students and staff using the universal medium of food to bring everyone together. Food brings people together in so many different ways and for so many different occasions. It is fun to share traditions, recipes and really interesting to hear other people’s stories (Mulrooney, 2021).

I loved taking part in this project man, good luck! (Wojadzis & Mulrooney, 2023).

However future teaching and learning takes place, the reinvention of learning so that the digitalisation of teaching and learning enhances relationships within and between staff and students has been called for (Schleicher, 2020). Focusing on student engagement and the quality of their learning experience is key (Sohail, 2022), and a sense of connection and belonging contributes to this. Humans are social creatures. The links formed with others are not only personally important but also enhance learning and attainment (Thomas, 2012) as well as staff satisfaction (Szromek & Wolniak, 2020). We could look at the move online necessitated by the pandemic through the lens of despair, something we had to fight through to get back to “normal”. Alternatively—ideally—we could also see it as a badge of hope, highlighting the importance of human connections within education, whether forged in person, online or both.

Steps toward hope

- Recognise and address the loss of belonging experienced by staff and students during periods of enforced online learning.

- Prioritise the cultivation of human relationships and community as a central aim in educational practices, however that education is delivered.

- Integrate food-related projects and initiatives as a means to foster connection, belonging, and cultural exchange within educational settings.

References

Abu, L., Chipfuwamiti, C., Costea, A. M., Kelly, A. F., Major, K., & Mulrooney, H. M. (2021). Staff and student perspectives of online teaching and learning: implications for belonging and engagement at university—a qualitative exploration. Compass, 14(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.21100/compass.v14i3.1219

Ahn, M. Y., & Davis, H. H. (2019). Four domains of students’ sense of belonging to university. Studies in Higher Education, 45(3), 622–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1564902

Curnock Cook, M. (2021). Rebuilding diverse student communities is at the top of vice chancellors’ post-Covid agenda. WONKHE. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/rebuilding-diverse-student-communities-is-at-the-top-of-vice-chancellors-post-covid-agenda/

Curnock Cook, M., & Dunn, I. (2022). From technology enabled teaching to digitally enhanced learning: a new perspective for higher education. HEPI. https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2022/11/04/from-bricks-to-clicks-why-and-how-higher-education-leaders-must-seize-the-opportunity-for-digitally-enhanced-learning/

Gehlbach, H. (2015). User guide. Panorama student survey. Panorama Education. https://www.panoramaed.com/panorama-student-survey

Gehlbach, H., & Brinkworth, M. E. (2011). Measure twice, cut down error: A process for enhancing the validity of survey scales. Review of General Psychology, 15(4), 380–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025704

Gilligan, C., Spencer, R., Weinberg, McK., & Bertsch, T, (2003). On the listening guide: A voice centred relational method. In P. M. Camic, J. E. Rhodes, & L. Yardley (Eds.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp. 157–172). American Psychological Association.

Gopalan, M., Linden-Carmichael, A., & Lanza, S. (2022). College students’ sense of belonging and mental health amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adolescent Health, 70(2), 228–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.10.010

Iivari, N., Sharma, S., & Ventä-Olkkonen, L. (2020). Digital transformation of everyday life–how COVID-19 pandemic transformed the basic education of the young generation and why information management research should care? International Journal of Information Management, 55,102183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102183

JISC. (2020). Reimagining blended learning in higher education. JISC. https://web.archive.org/web/20231105064944/https://beta.jisc.ac.uk/guides/reimagining-blended-learning-in-higher-education

JISC. (2021). Teaching staff digital experience insights survey 2020/21 UK higher education (HE) survey findings. JISC. https://repository.jisc.ac.uk/8568/1/DEI-HE-teaching-report-2021.pdf

JISC & Emerge Education. (2022). From technology enabled teaching to digitally enhanced learning: a new perspective for HE. JISC. https://beta.jisc.ac.uk/reports/from-technology-enabled-teaching-to-digitally-enhanced-learning-a-new-perspective-for-he

Lasko-Skinner, R., & Sweetland, J. (2021). Food in a pandemic. Demos and the Food Standards Agency. https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/fsa-food-in-a-pandemic-march-2021.pdf

Longhurst, G. J., Stone, D. M., Dulohery, K., Scully, D., Campbell, T., & Smith, C. F. (2020). Strength, weakness, opportunity and threat (SWOT) analysis of the adaptations to anatomical education in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Anatomical Sciences Education, 13(3), 301–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1967

Lupton, D. (1994). Food, memory and meaning: the symbolic and social nature of food events. Sociological Review, 42(4), 664–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1994.tb00105.x

Mulrooney, H. (2021). Food for thought: A pilot scheme exploring the use of cultural recipe and story sharing to enhance belonging at university. Practitioner Research in Higher Education, 14(1), 60–71.

Mulrooney, H. M., & Kelly, A. F. (2020). COVID-19 and the move to online teaching: Impact on perceptions of belonging in staff and students in a UK widening participation university. Journal of Applied Learning and Teaching, 3(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.37074/jalt.2030.3.2.15

OIA (2021). Annual report. OIA. https://www.oiahe.org.uk/media/2706/oia-annual-report-2021.pdf

OIA (2022). Annual report. OIA. https://www.oiahe.org.uk/media/2832/oia-annual-report-2022.pdf

OIA (2023). OIA statement in response to high court judgment in student group claim. OIA. https://www.oiahe.org.uk/resources-and-publications/latest-news-and-updates/oia-statement-in-response-to-high-court-judgment-in-student-group-claim/

Ribera, A. K., Miller, A. L., & Dumford, A. D. (2017). Sense of peer belonging and institutional acceptance in the first year: The role of high-impact practices. Journal of College Student Development, 58(4), 545–563. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2017.0042

Rozin, P. (2005). The meaning of food in our lives: A cross-cultural perspective on eating and well-being. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behaviour, 37(Suppl 2), S107–S112. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60209-1

Schleicher, A. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on education: Insights from Education at a glance 2020. OECD. https://web.archive.org/web/20200928140501/https://www.oecd.org/education/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-education-insights-education-at-a-glance-2020.pdf

Sohail, M. (2022). Online learning: What next for higher education after COVID-19? World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/online-learning-higher-education-covid-19/

Szromek, A. R., & Wolniak, R. (2020). Job satisfaction and problems among academic staff in higher education. Sustainability, 12(12), 4865. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124865

Thomas, L. (2012). Building student engagement and belonging in higher education at a time of change. Final report from the What Works? Student Retention and Success programme. https://s3.eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/assets.creode.advancehe-document-manager/documents/hea/private/what_works_final_report_1568036657.pdf

Tice, D., Baumeister, R., Crawford, J., Allen, K., & Percy, A. (2021). Student belongingness in higher education: Lessons for Professors from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 18(4). https://doi.org/10.53761/1.18.4.2

United Nations (2020). Policy brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. United Nations. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-education-during-covid-19-and-beyond

Vickerstaff, B. (2023). Why digital soft skills are crucial to graduate success and HE digital transformation. JISC. https://beta.jisc.ac.uk/blog/why-digital-soft-skills-are-crucial-to-graduate-success-and-he-digital-transformation

Watermeyer, R. P., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: Afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. Higher Education, 81(3), 623–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

Watermeyer, R. P., Shankar, K., Crick, T., Knight, C., McGaughey, F., Hardman, J., Suri, V. R., Chung, R. Y.-N., & Phelan, D. (2021). ‘Pandemia’: A reckoning of UK universities’ corporate response to COVID-19 and its academic fallout. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 42(5-6), 651–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2021.1937058

Weale, S. (2023). UK students seek compensation for COVID-affected tuition. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/may/24/uk-students-seek-compensation-for-covid-affected-tuition

Williams, J. D., Crockett, D., Harrison, R. L., & Thomas, K. D. (2012). The role of food culture and marketing activity in health disparities. Preventive Medicine, 55(5), 382–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.12.021

Wojadzis, O., & Mulrooney, H. (2023). Using food-related images to explore food values and belonging in university staff and students. New Directions in the Teaching of Natural Sciences, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.29311/ndtns.v18i1.4110

Wray, S., & Kinman, G. (2021). Supporting staff wellbeing in higher education. Education Support. https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/x4jdvxpl/es-supporting-staff-wellbeing-in-he-report.pdf

Yorke, M. (2016). The development and initial use of a survey of student “belonginess”, engagement and self-confidence in UK higher education. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(1), 154–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2014.990415