44. If the tomatoes don’t grow, we don’t blame the plant:

A reflection on co-created CPD sessions for staff reimagining education and the impact on their daily practice

Mâir Bull, Stephanie Aldred, Sophie Bessant, Sydney-Marie Duignan, and Eileen Pollard

©2025 Mâir Bull et al, CC BY-NC 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0462.44

Abstract

This case study reflects on the co-design and delivery of a series of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) sessions for teaching staff, aimed at reimagining education and enhancing educator wellbeing. The sessions modelled creative practice and active learning, exploring themes such as creative and playful pedagogies, object-based learning, sensory teaching experiences, and techniques for effective use of voice and body language. Insights from the first workshop were captured in a video1 animated by recent graduate Kalon Smith (2023). Using the metaphor of Higher Education teachers as tomato plants, the study highlights the need for a nourishing educational ecosystem, with a particular focus on the vital role of educational developers in supporting teacher growth and flourishing.

Keywords: creative practice; wellbeing; active learning; reimagining; CPD (continuing professional development)

Introduction

Fig. 44.1 “Tomato Plants” (image by Kalon Smith, Manchester Metropolitan University, 2023, CC BY-NC 4.0).2

During the co-design of a series of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) sessions for teaching staff at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), we (a group of educational developers) reflected on the analogy: if the tomatoes don’t grow, we don’t blame the plant. Let’s assume that the tomato plants are teaching staff, the tomatoes are students, and the soil and other environmental conditions are Higher Education (HE) and the wider educational landscape. Tomato plants cannot produce juicy tomatoes if they have too little water, sunshine, or nutrients. So why are teaching staff routinely held accountable for any, or indeed all, of the problems related to student outcomes? This emphasis on performativity in England, reinforced by HE marketisation (Jones, 2022), has created a culture of blame and a worrying decline in staff health and wellbeing (Wray & Kinman, 2021; Jayman et al., 2022).

Ken Robinson (2022; and Robinson & Robinson 2022) characterised this crisis in education more broadly as paralleling how we have treated the natural world; an overemphasis on homogenisation, outputs, and productivity. Like the decline in our natural environments, our one-size-fits-all model of modern “factory” education has led to a decline in the health of our educational environments and a diminished experience for staff and students. Inspired by the works of Robinson, and his daughter Kate (Robinson, 2022; Robinson & Robinson, 2022), we set about designing CPD sessions underpinned by creative practice and active learning, that explored educational approaches such as play, object-based learning, sensory experiences, building confidence and presence through drama skills, and connecting to the natural environment. We wanted to support and nurture our tired, stressed, and overworked “tomato plants”, to help them reimagine not only their teaching approaches, but also the broader HE ecosystem and their place within it. This reflection summarises these co-designed sessions, considering how educators can be empowered with specific tools to make a difference to their daily practice and their wellbeing.

10% Braver Teaching

Vignette 1

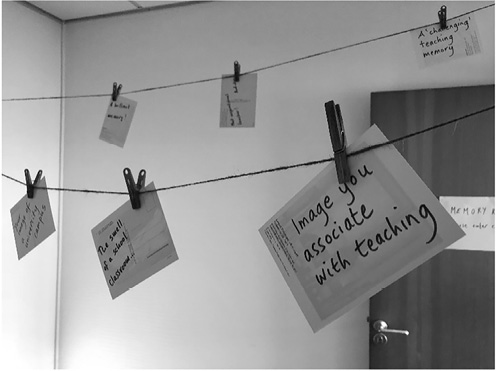

I pushed open the door to the memory room, realising I was holding my breath I felt a child-like sense of curiosity. Postcards were pegged on washing lines criss-crossing the room. Some were front facing, depicting art from a broad spectrum of styles, others revealed their written sides saying things like “your first lecture” and “a challenging teaching memory”. Music was playing, calm but uplifting. I loved how evocative the space was and instantly I felt flooded with memories.

Our starting point: “10% Braver Teaching” workshop

As a group of educational developers, we felt passionately about Robinson’s (2022) reframing and wanted to respond with an offer for colleagues to reimage education. We borrowed the phrase “10% Braver” from WomenEd (Porritt & Featherstone, 2019), a feminist movement sweeping the globe, predominantly in schools but now in HE. Although WomenEd is about connecting and giving a voice to aspiring and existing women leaders, its tagline “Being 10% Braver” is about being empowered to try new things—the idea is that even being 10% more courageous, stepping a little out of one’s comfort zone, can often make a big difference. We therefore designed a workshop that called on colleagues to be 10% Braver in their teaching—to experiment, to be playful and creative, and to consider how these methods could impact their teaching and wellbeing. The invite to attend went out across our institution, although more colleagues from our Arts and Humanities, and Health and Education faculties took up the voluntary places. Within this cohort, there was a wide variation in experience including those with over a decade in the classroom, to those new to teaching, some having transferred from industry recently.

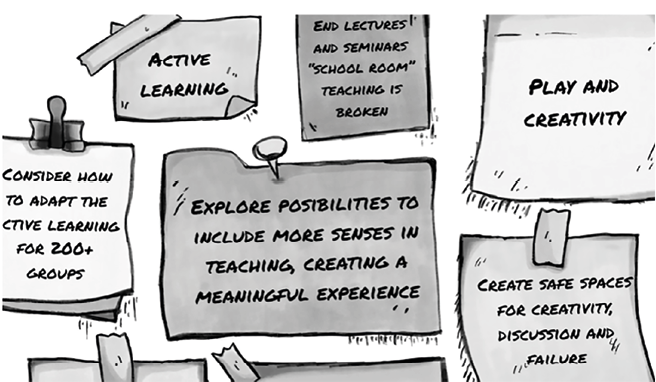

In the workshop, staff moved in a carousel around experiential activities. We wanted to practise what we were preaching and nurture a creative experience where colleagues could touch, smell, see, hear, and even taste during the session. For example, in one activity staff constructed plant cells with scented playdough (pictured below, in Figure 44.3), reflecting on where tactile tasks could be used in their own disciplines, and the value of working collaboratively with students on playful learning experiences. In another part of the space, colleagues chatted about the ingredients of a creative workplace and broader macro factors, whilst mixing, pouring, and tasting in a group cooking task. This exercise generated a range of discussions about experiential learning and relational pedagogy, but also the power of food in creating a sense of community and belonging.

The vignette above describes a participant’s experience in one of the activity spaces, “The Memory Room”. This small space was emptied of furniture and instead string cross-crossed just above eye-height. On the washing lines were postcards depicting works of art on one side, with memory stimuli on the other, for example “your first teaching memory”, “your favourite teaching moment”, and “the smell of a classroom”. Light instrumental music was playing, and participants entered either individually or in pairs, to move around the space and consider the memories it triggered for them. Outside the room, sofas and chairs made a comfortable space for colleagues to chat freely about their responses and listen to others’ reflections.

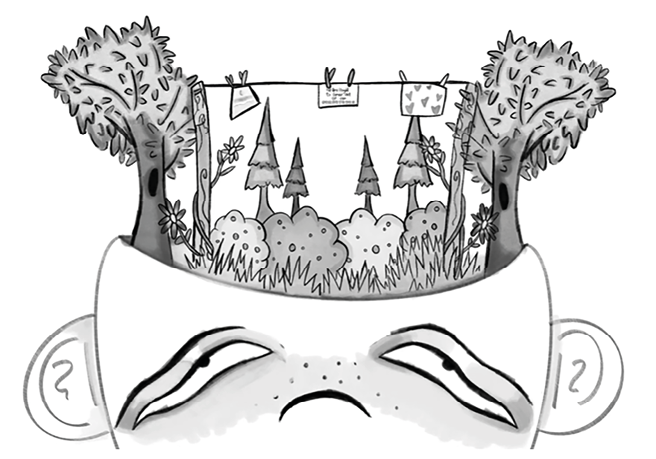

Fig. 44.2 “Burn Out” (image by Kalon Smith, Manchester Metropolitan University, 2023, CC BY-NC 4.0).3

The soil components

As the groups interacted with the activities, they reflected on the ingredients of the “soil”—and how they would like to reimagine their own educational practice. This led, perhaps inevitably, to a critique of the meso and macro factors that influence education. The crucial factors for any organisation wishing to nurture creative processes and outputs (in other words healthy soil) are summarised here:

a) organisation-wide supports; (b) psychological safety; (c) recognition of the value of intrinsic motivation; (d) sufficient time; (e) autonomy; (f) developmental feedback (including the freedom to fail and try again); (g) creativity goals (Amabile et al., 2012 in MacLaren, 2012, p. 162).

The above provided a crucial framework for us when planning the next wave of CPD sessions for staff. However, it was important for us as workshop leaders to recognise that we can encourage staff to reimage education, but education is only part of a much larger system that needs to be reformed to truly reinvigorate the soil for our tomato plants. Jean Anyon (2005) asserts that the macroeconomic policies, controlling such things as minimum wage, affordable housing, and social benefits, create complex limiting circumstances that education cannot singularly overcome. What we can all do though is reimagine with “critical hope”. Critical hope is described as “developing the individual and collective spirit to imagine future possibilities and fostering the energy to continually create transformative spaces of action in order that they might be realised” (Danvers, 2014, p. 1239). Or, as Angela Davis would say, our place is in the struggle.

The practical steps for remaining critically hopeful within this struggle concern building in ongoing space for individual reflection on what gives you nutrition as an educator. Is this in reading and writing, perhaps through dialogue with others, or regularly attending events and conferences? Whatever it might be, it is crucial to make sure that some aspect of this wellbeing activity is scheduled into your calendar or diary each week, preferably each day, maybe using a particular or significant colour-code. Once you have decided on what gives you nutrition, it is worth then considering how you will make time, for example, using Pomodoro or other creative time management techniques.

Fig. 44.3 Images from 10% Braver Teaching workshop (images by author, CC BY-NC 4.0).

10% Braver Colleagues

Vignette 2

When the end of module feedback came through, I read bland comment after bland comment. But something in the pit of my stomach knew worse was coming… and then three insulting statements appeared including “this unit was a complete waste of time”. I was so incredibly embarrassed and feared what might happen next. My chest hurt and all I could think was how much effort I had put in across the year, in more areas than I could list, yet it all seemed to pale into nothingness in light of these student comments.

A follow up series of events:

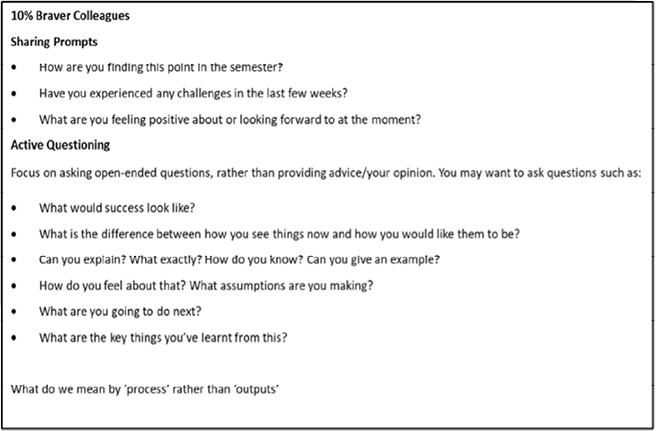

“10% Braver Colleagues” lunch and share

One unexpected insight from 10% Braver Teaching was that, however much colleagues enjoyed the interactive exercises, they repeatedly emphasised how much it meant just to get together in person and talk. Several people shared very personal and emotional experiences, some even cried. As a result, and as a low-key way of continuing the conversations, we decided to host an informal “Lunch and Share” hour towards the end of each month. We used the handouts below to guide colleagues who attended and took it in turns to share with the group.

Fig. 44.4 A handout from 10% Braver Colleagues, 2023 (CC BY-NC 4.0).

The practice was linked to Reg Revans’ famous Action Learning Sets, which he used when he was director of education at the National Coal Board in the 1940s: “He proposed that in a changing world people should be masters in the art of posing questions as nobody knows what is going to happen next” (Johnson, 1998, p. 296). In an age of climate crisis, ChatGPT, Brexit, rising costs-of-living, and inflation and a world recovering economically, emotionally, and spiritually from a devastating pandemic, we really are now living in a time where nobody knows what is going to happen next. But it helps to talk, and as one participant said, it was “amazing to have the space to talk and reflect”.

We considered 10% Braver Colleagues and some of the experiences educators have reported over the years in various institutions, as illustrated by Vignette 2. We decided to focus on two key discussion points in particular: reframing and wellbeing.

Reframing and wellbeing

Linet Arthur (2009) analysed staff responses to negative student feedback using the memorable “Shame, Blame, Tame, Reframe” model. She found that staff who felt little agency and influence tended to feel shame and/or would blame the students. Staff who had more agency would either try and “tame” or “reframe” the situation. Reframing can involve mature reflection, professional dialogue and rethinking, for example: context, content, level, student expectations, programme-level factors, assessment alignment etc. To reframe the issues raised by unsatisfied students, we would argue that a humane environment is required, and this is what we aim to facilitate in all our workshops too: support, trust, and importantly time to reflect, and this reflection will in turn lead to growing self-awareness. This self-awareness is a powerful attribute, which encompasses “cognitive, imaginative, creative, lingual, emotional and somatic dimensions of the individual” (Yeatman, 2022, p. 251).

Reframing and wellbeing discourses have informed our planning for the next series of workshops. We are more mindful of the pace of the sessions, as one of our participants summarised that they loved the session but would have liked more time to “digest” and consider the tools. We are advocates for creative teaching methods and the notion that these have a positive correlation with student engagement and staff enjoyment; however we do recognise that not everyone may be in the right space, metaphorically, to embrace new pedagogies—it takes time for the tomato plants to grow and develop after all. Therefore, encouraging colleagues to consider their own needs and the extent to which they can experiment or embed techniques such as play, experiential learning or object-based learning, for example, will be crucial to the success of the next wave of CPD sessions.

Fig. 44.5 “Thoughts” (image by Kalon Smith, Manchester Metropolitan University, 2023, CC BY-NC 4.0).

The Secret Teacher

Vignette 3

“Oh I’m definitely going to try that”, exclaimed a staff member enthusiastically. I had just demonstrated the “hip drop”—a secret weapon in teaching that very slightly adjusts your posture, still tall with feet shoulder-width apart but with a slight drop of the hip that pushes the weight to one side. It’s so minor that most don’t consciously notice the change, but it’s incredibly powerful, communicating confidence without aggression. The room buzzed excitedly as colleagues tested postures in pairs, reflecting on the look and feel of the poses.

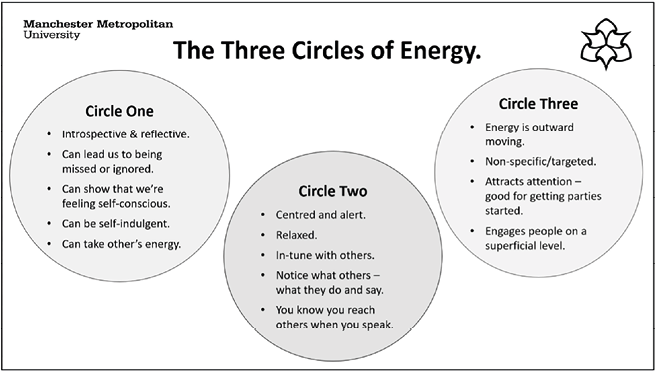

The discussions from teaching staff that followed the previous workshops indicated an energy and desire to use more creative methods; however, some felt their classroom confidence was holding them back from being “10% Braver”. The request was for a wider toolkit that would empower staff, foster student engagement and build a positive classroom culture—so we created “The Secret Teacher” workshop, using drama practices to explore teacher presence, in particular voice, body language and space. One of the activities encouraged staff to reflect on Patsy Rodenburg’s (2017) Three Circles of Energy (pictured), and how the demeanour in each circle would affect students and their levels of engagement. The circles of energy prompted some interesting analysis; staff identified with a range of the descriptions, either recalling real experiences or considering the potential impact of the behaviours on their own wellbeing and enjoyment of teaching, as well as on students’ learning.

Fig. 44.6 Three Circles of Energy (after Patsy Rodenburg, 2008) (image by authors, CC BY-NC 4.0).

Fig. 44.7 Photograph from The Secret Teacher workshop (image by authors,

CC BY-NC 4.0).

Theory aiding reflection

Psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan’s (2009) self-determination theory maintains that human motivation comprises the innate psychological need for competence, autonomy, and relatedness. Lucy Crehan (2016, p. 52) defines “relatedness” as like “social capital”, the value and strength of human relationships. Relatedness is not just about staff–student relationships though, but staff–staff interactions too, with opportunities to share ideas, learn from one another and build professional trust being seen as vital (Crehan, 2016). On reflection, these concepts of competence, autonomy, and relatedness were crucial themes of our workshops too.

True learning happens when we try new things—when we practise something, see how it goes, and then try it again. Pedagogical practices that encourage metacognition and active reflection are built on this premise (Rempel, 2022).

In “The Secret Teacher” session, opportunities for social interaction, building relationships, and fostering confidence were woven throughout. We used humour and play as useful tools, along with storytelling (of “failures” too, of course) and experimentation. These ingredients helped to foster “mattering”. Gordon Flett (2018, p. 5) states that mattering “captures the powerful impact people have on us and it reflects the need to be valued”. In addition, Flett (2018) outlines that the person who matters is resilient and engaged, but without mattering people are prone to intense stress. Moreover, racialised colleagues and those from a range of marginalised backgrounds face additional barriers to feeling they matter in a HE context (Ahmed, 2012).

Conclusion

As educational developers, our role is to collaborate with and support individual academics, and the wider university, aiming to enhance the student learning experience. We are a vital component of the soil and the HE ecosystem that nourishes the tomato plants and supports them to yield fruit. If we want to reimagine education, we also need to reimagine educational development; this small experiment in one university is one step closer to doing that. Through the workshops outlined in this case study, we have aimed to move away from one-hour, online, lunchtime sessions, squeezed between meetings and focused on the latest HE agenda, to somewhere more creative, open, playful, sensory, emotional, and honest. In these sessions we weren’t talking about graduate outcomes, good honours, awarding gaps, or ChatGPT—this was a space for imagining how university education could be different and how educators’ lives could be better nourished. Some of the more practical tools we hope that we have equipped our tomato plants with, include: confidence to try more creative and playful pedagogies; inspiration to use objects and sensory teaching experiences; and recognition that time and space to reflect on “how things are going” needs to be built into weekly schedules, and that techniques for effective use of voice and body language, enhancing our “teacher presence”—are vital for combating those “imposter syndrome” feelings and giving us a greater sense of ownership and peace in our classrooms.

This was an excellent workshop which has left me enthused. I have been teaching for over 15 years and sessions like this are a great opportunity to stop and reflect on my practice and think about what I can do better (Workshop participant feedback, The Secret Teacher).

Fig. 44.8 “Moving Forward” (image by Kalon Smith, Manchester Metropolitan University, 2023, CC BY-NC 4.0).

Steps toward hope

- Develop professional development opportunities that not only advocate but demonstrate playful pedagogies, sensory experiences, and dynamic teaching techniques.

- Support educator wellbeing through a nourishing ecosystem.

- Recognise and cultivate the conditions—both institutional and relational—that enable teachers to thrive, using metaphors like the tomato plant to reframe support strategies.

- Position educational developers as central agents in creating environments that foster teacher growth, creativity, and resilience in Higher Education.

References

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Duke University Press.

Anyon, J. (2005). Radical possibilities: Public policy, urban education, and a new social movement. Routledge

Arthur, L. (2009). From performativity to professionalism: Lecturers’ responses to student feedback. Teaching in Higher Education, 14(4), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510903050228

Crehan, L. (2016). Clever lands. Unbound.

Danvers, E. (2014). Discerning critical hope in educational practices. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(6), 1239–1241. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.939604

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2009). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Flett, G. L. (2018). The psychology of mattering: Understanding the human need to be significant. Academic Press.

hooks, b. (2014). Teaching to transgress. Routledge.

Jayman, M., Glazzard, J., & Rose, A. (2022). Tipping point: The staff wellbeing crisis in higher education. Frontiers in Education, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.929335

Johnson, C. (1998) The essentials principles of action learning. Journal of Workplace Learning, 10(6/7), 296–300. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/362655899_Tipping_point_The_staff_wellbeing_crisis_in_higher_education/citation/download

Jones, S. (2022). Universities under fire: Hostile discourses and integrity deficits in higher education. Palgrave Macmillan

MacLaren, I. (2012). The contradictions of policy and practice: Creativity in higher education. London Review of Education, 10(2) 159–172. https://uclpress.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.1080/14748460.2012.691281

Porritt, V., & K. Featherstone (Eds.). (2019). 10% braver: Inspiring women to lead education. Sage.

Rempel, H. G. (2022). Building in room to fail: Learning through play in an undergraduate course. The Journal of Play in Adulthood, 4(2), 138–161. https://doi.org/10.5920/jpa.1020

Robinson, K. (2022). A future for us all—Sir Ken Robinson [video]. YouTube.

Robinson, Ken, and Robinson, Kate. (2022). Imagine If… Creating a future for us all. Penguin Books.

Rodenburg, P. (2017). The second circle: How to use positive energy for success in every situation. W.W. Norton & Company.

Smith, K. (2023). 10% braver teaching [video]. YouTube.

Todoist. (2023). The pomodoro technique: Beat procrastination and improve your focus one pomodoro at a time. Todoist. https://todoist.com/productivity-methods/pomodoro-technique

Wray, S., & Kinman, G. (2021). Supporting staff wellbeing in higher education. Education Support. https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/x4jdvxpl/es-supporting-staff-wellbeing-in-he-report.pdf

Yeatman, A. (2022). The good of the whole: An idea of education for the twenty-first century. In M. W. Apple, G. Biesta, D. Bright, H. A. Giroux, A. Heffernan, P. McLaren, S. Riddle, & A. Yeatman (Eds.), Reflections on contemporary challenges and possibilities for democracy and education. Journal of Educational Administration and History. 54(3), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2022.2052029

1 Throughout the 10% Braver Teaching workshop Manchester Met graduate, Kalon Smith was busy sketching, capturing the salient themes from the day and then bringing them to life in an animation (Smith, 2023)—his illustrations also feature in this case study.

2 See full video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EYuOEpQqUBw

3 See full video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EYuOEpQqUBw