21 The New Apostles

The subject of religion caused embarrassment among the followers of Jeremy Bentham. Those who thought most clearly about his philosophy and who recognized the social forces at work in the England of the day were bound to be opposed to the influence of the Churches (which was at the time unusually reactionary) and were by conviction atheists. On the other hand, the kind of men who liked the absolutist features of Benthamite philosophy and were attracted by the prospect of brainwashing their fellow men on the pretext of doing them good, were naturally prone to the similar attractions offered by organized religion.

It was a cruel dilemma for the leaders of the movement, made worse by the circumstances of the 1820s. Right-wing forces, both Church and State, tended at that time to condemn liberal ideas as seditious and blasphemous, as if the two offences were synonymous, and had some success in keeping some people in obedience as a result. Jeremy Bentham, rather than risk his important programmes for such a marginal subject as religion, adopted the device of being extremely circumspect in his open references to religion and thus succeeded in removing the impression that he was opposed to it.

Soon it became acceptable to be both an eager Christian and a Benthamite. Blaquiere and Stanhope belonged to this group and from the beginning the London Greek Committee had a distinctly Christian bias. Greece was not only to be regenerated in terms of English utilitarianism but converted to English Christianity as well. As Stanhope himself declared when the first consignment of Bibles arrived: ‘They will save the priests the trouble of enlightening the darkness of their flocks. Flocks indeed! With the press and the Bibles, the whole mind of Greece may be put in labour’.1 An alliance was formed between the London Greek Committee and various Christian groups, principally the missionary societies, to propagate in Greece the eternal truths of Christianity as understood in contemporary England.

The dispatch of missionaries to the technologically more backward areas of the world was one of the symptoms of the increasing power and arrogance of Western Europe in the nineteenth century. Earlier centuries had been unashamed of simple military conquest and economic exploitation. Now, it was felt, some higher justification was required. Cultural imperialism became the fashion, and the missionaries were its storm troopers. Soon these narrow intolerant men were to play a part in extinguishing primitive societies all over the world. In Greece, as ever, things were different.

Before the outbreak of the Greek Revolution the Levant was perhaps the most intractable area of the world with which the missionary societies had to deal. The few missionaries who ventured into the Ottoman Empire had scant success. Since under the Ottoman system a man’s religion determined his place in the world, and it was their religion which gave the various national groups their identity, a change of religion was regarded by the authorities as a serious matter. Conversion to Islam was not discouraged for the able and ambitious, but attempts to convert Turks to Christianity could rightly be regarded as attempts to disrupt the social structure and were forbidden. For a Turk to renounce Islam was a capital offence. Jews were regarded by the Ottoman authorities as fair game and no impediment was put in the way of missions to them. But Jews proved to be almost impossible to convert. The Levant was sadly barren ground. The dozen or so authenticated examples of conversion all seem to have had unusual features and some were obtained by outright bribery.

With the establishment of British rule in Malta and the Ionian Islands, secure bases were available for missionary forays and gradually missionaries ventured further afield. Two Americans visited Asia Minor, Egypt, and Palestine in the early 1820s. The Germans penetrated to Georgia, and a Scottish expedition tried its luck in the Caucasus. The Rev. Joseph Wolff made numerous dangerous journeys all over the Levant in an attempt to convert the Jews. In spite of his repeated warnings that the Messiah was due to return in 1847—he and his wife intended to go to Jerusalem for the occasion—the various Jewish communities invariably greeted him with hostility and even from time to time tried to kill him. Wolff admitted that his immense efforts had resulted in almost total failure. From Malta the Rev. William Jowett made several visits to Greece and the Ionian Islands before the Revolution, but again with little success. In his book he examines the reasons for his failure and discusses ways in which missionary performance might be improved.2 Extirpation of the Moslems, he concluded magnanimously, was not the answer to the problem.

When philhellenism was at its height in England in 1824, the men of the London Missionary Society decided to turn their attention to Greece. When it was pointed out that the Greeks were already Christians, it was ruled that nevertheless they were eligible for conversion. The constitution of the Society, it was noticed, allowed it to help ‘heathen and other unenlightened countries’.3 Other British missionary groups soon joined in and a few American Christians made a contribution, but none of any other nationality. Sending missionaries, like sending newspaper printing presses, was an elaboration of philhellenism unthought of elsewhere in Europe.

The British Christians surveyed the plight of their Greek brethren with sadness tinged with disgust. All observers were of the opinion that the Greek Church was ignorant, superstitious, and corrupt. Although the Church still contained honest and educated men among its leaders, these were few and far between. And the gap between the educated few and the generality of bishops and parish priests in Greece was immense. The Greek Church like the Greek people was degenerate and in need of regeneration.

Surprisingly, it was seldom noticed that the Greek Church contained some of the few indubitable examples of the survival of a tradition from ancient times. Demeter, Artemis, and Dionysus, to give only the most obvious examples, had lost few of their ancient characteristics in the course of their transmogrification into St. Demetrius (or Demetra), St. Artemidos, and St. Dionysus.

The connection between Modern Greece and Ancient Hellas, which was the inspiration of so much philhellenic activity, evoked no sympathetic response from the British Christians. Pre-Christian civilization was of no interest. They were so determined to avoid saying a good word about paganism that they practised a kind of anti-philhellenism. One missionary coming across the magnificent standing columns of the Temple of Apollo in Aegina dismissed it as ‘an abominable fane’.4 To him all the Ancient Greeks were ‘sunk to the lowest grade of vice and woe’. Another claimed that the sight of Mount Parnassus left him cold until he recollected that the eye of St. Paul had rested on it and he could ‘hold a species of distant communion with him by means of this classical mountain’.5 The same missionary declared his faith that the honours of those who served God (meaning men like himself) would endure and increase in splendour when Classical Greece ‘will have sunk in eternal oblivion or be consigned to merited insignificance’.6 Another admitted sheepishly that, when he came upon a famous place, ‘it must not be denied that we stopped to gaze a moment…. But rarely did we go out of our way to gratify our classical curiosity’.7

In matters of religious controversy, the more trivial the point of difference and the more unascertainable the answer to the question, the more uncontrolled the passions and the more puffed-up the indignation. The British Christians followed the usual pattern in their differences with the Greeks. One of the missionaries, after detailing lovingly the full horrors of the errors of the Greek Church and clergy which he had discovered, summed up his conclusions, conclusions with which most of his colleagues would have agreed:

There is an Infernal originality in apostate Christianity; it is the master effort of the Prince of Darkness. The Church of Christ becomes the synagogue of Satan. An attempt is made to combine light and darkness; to bring Heaven and Hell into monstrous and impossible coalition; to mingle the Hallelujahs of Paradise with the shrieks of the lost world; to place God and Satan conjointly on the throne of the universe.8

The apparently more obvious topics of criticism were ignored. None of the missionaries, as far as can be ascertained, remarked on the fact that the Greek bishops and priests had exhorted their flocks to exterminate the Turkish and Jewish minorities and had, in many cases, taken the lead and personally assisted in piercing the bodies of their defenceless neighbours. The missionaries sometimes acknowledged a thrill of inquisitive horror when they addressed audiences known to have organized mass murders but they prudently confined their sermons to safer topics.

The prime method chosen for bringing about the regeneration of the Greek Church was to distribute the Bible. The Greeks who could read, it was noticed, had little difficulty in obtaining translations of ‘the ravings and poisonous productions’ of Rousseau and Voltaire.9 Since the Church in Greece was ‘impious, ignorant, lifeless’, one of the shocked missionaries asked, ‘Is it at all surprising that young Greeks educated in Italy, Germany, France, or England, should return to the classic land disciples of Alfieri, of Schiller, of Voltaire, of Lord Shaftesbury?’10 The Bible was to be the chief weapon against these hateful influences.

In addition to the cannon, tools, and printing presses sent by the London Greek Committee in the Ann there was a consignment of 320 Greek Bibles and tracts. These were to be the responsibility of one of the artificers, the tinman Brownbill, called by Parry a ‘hypocritical canting methodist’11 and by Byron, ‘an elect blacksmith’.12 When the artificers, including Brownbill, decamped to the Ionian Islands, the books were left on Lord Byron’s hands. He had them piled up outside his room at Missolonghi and offered copies to his numerous visitors. But Byron was too intelligent and too tolerant a man to make a good missionary.

The missionary societies donated bundles of Bibles to the captains of British warships bound for Greek waters and urged them to distribute them. The chaplain of H.M.S. Cambrian, who was in Greece in 1825, found that it was almost impossible to find anyone who would accept a Bible as a gift. A British merchant in Salonika explained that he had disposed of only three out of a consignment of forty in four years. At Nauplia the chaplain discovered that there were already many more Bibles than anyone wanted and new consignments were still arriving. The Greek priests refused his offers by showing him the heaps they already possessed.13

But the work of religious regeneration needed more direct methods. It was Colonel Stanhope who first suggested that missionaries should be sent. He named as his first choice the Reverend Sheridan Wilson who was already engaged on the futile task of trying to convert the Maltese from Roman Catholicism. Wilson is described by one of his English fellow priests as a Methodist and ‘the most liberal of the sect I have met with’.14 Liberalism is in the eye of the beholder.

Wilson was the first missionary to be employed full-time in Revolutionary Greece. When the directors of the London Missionary Society ‘first turned a pitying eye on Greece’—as he explained—they began by establishing missionaries on the Ionian Islands. Already several missionaries had worked there and schools were established under their auspices in almost every town. The life was hard, two of the missionary wives died at their duty, but the missionary work had the full support of the British authorities in the islands.

It was quite another matter to venture alone into the anarchic conditions of Greece. Wilson himself was never lacking in courage. He was landed at Spetsae with his boxes of books just as night was falling on Christmas eve 1824. A Turkish fleet was in the offing and a stranger laden with unknown packages was bound to cause suspicion. ‘I was in the utmost danger of assassination the moment I set foot ashore’, Wilson explained later. ‘Three hundred eyes and three hundred more flashed fire upon me. But when I pointed to my boxes and stated the benevolent object I had in view, their hands let go the grasped yatagan’.

Wilson spent the first night ashore terrified that he was about to be murdered since his host pointedly kept his long knife by his hand as he slept. But the Albanians and Greeks of the island, whatever else they may have thought about this strange beardless English priest, concluded that he was harmless. Soon Wilson was up and about round the island. In each of the island’s forty warships he left two Bibles, one for the captain and one for the crew.

After a short stay he set off for the mainland and spent the next few months travelling all over Southern Greece. Often, as he reached a place that had been visited by St. Paul, he recalled that he too was an apostle to the gentiles. The church which St. Paul had planted still existed; it had ‘retained its apostolic purity till carnal ascetics, light-headed monastics, lucre-loving hierophants, lordly prelates, and scripture-neglecting professors obscured the glory of the temple’.

Soon Wilson was giving his hosts practical advice on how the apostolic purity could be restored. The monasteries, he declared, should be swept away; they were ‘hives of sanctimonious drones’. But most of his suggestions had more limited aims. At Spetsae he finally induced an old Greek to take a glass of wine during Lent after giving him a sermon on the theory of fasting. The old man drank the wine out of a mixture of respect and fear of Wilson. Obviously the missionary was not getting his point across. ‘This very man’ he commented indignantly later, ‘who durst not drink a glass of wine on Saturday night, I saw next morning playing at cards!’

Wilson regularly insisted on the need to say grace at meals. The Greeks who were used to making the sign of the cross on these occasions were solemnly warned about the iniquity of this superstition. Profanation of the Sabbath, one need hardly add, was also a topic that caused great concern.

‘“Captain Anthreas” said I, “you should not sing songs on Sunday”—“Why afendi?”—“It is wicked”—“But what must I do?”—“Sing psalms.”’

The music of the Greek Church, he found, was ‘intolerably nasal, full of most unmeaning and unedifying repetitions’. He discussed how it could be reformed with one of the bishops and the bishop promised that it would be done. But when the bishop demonstrated the new system, Wilson could only comment, ‘Though I felt the condescension of this simple bishop, yet I honestly expressed to him my painful impression that his country had changed rather the character than the airs’. To explain what sacred music should really be like he sang him a little hymn:

Gentle stranger, fare you well!

Heavenly blessings with you dwell!

Blessings such as you impart,

To the orphan’s bleeding heart.

Gentle stranger, fare you well!

Heavenly blessings with you dwell!

Sometimes Wilson’s bland narrative unconsciously gives a glimpse of a more robust response to the missionary’s self-assured advice. ‘The Greeks … are ungallant enough to salute gentlemen before ladies. “We English,” said I, “always take the ladies first.” “Well,” replied one of the party, “we never do.”’ Such wilful unapologetic ignorance was difficult to condone.

It never occurred to Wilson to doubt that the ideas and customs current among his small English Christian sect in 1825 represented eternal truth and perfect morality. A man who brought such gifts to the Greeks need not underestimate himself. At one of his Sunday schools two Greek brothers presented themselves and gave their names as Leonidas and Lycurgus. ‘Only imagine,’ Wilson remarked, ‘Leonidas and Lycurgus in a Sunday school! … Ah! I have said as I thought on those two dear boys, if your celebrated namesakes had enjoyed your privileges—had they sat at the feet of Jesus, what a happy land Lacedaemon might have been!’ By sending him to Spetsae, he declared on another occasion, the British Churches had conferred ‘grace’ on the island. ‘Yet by me you only paid your debts. From the learned ancestors of the modern Greeks, Britain received the writings of a Homer, a Plato, a Basil, and is repaying in these latter days her ancient obligations’. There can have been few besides himself who thought that the Rev. Sheridan Wilson was a fair exchange for Homer or Plato or even for Basil.

Wilson was the first missionary in Greece, but he was soon followed by other clergymen of other denominations sent by other missionary societies. Whatever the differences in dogma and doctrine that separated these men, they all seem to exhibit, in varying proportions, self-righteousness, insensitivity, intolerance, pomposity, and stolidity. Nothing they saw pleased them—perhaps occasionally the weather or the scenery but never the people and certainly not the classical remains. Even the colourful little jackets of the Greek women, one clergyman expostulated, were ‘Staysless’ and ‘positively indecent and disgusting’.15 Sometimes one gets the impression that the missionaries were competing with one another to see who could compile the longest list of Greek superstitions or who could find the grossest example. For all their talk of Christianity and for all their hard work in establishing mission schools, they showed hardly a spark of charity. Even their fellow countrymen felt that the ‘utter unprofitableness of these gentlemen cannot be sufficiently pointed out’16 and the Rev. Joseph Wolff, the missionary to the Jews, felt obliged to pass some criticisms on his fellow missionaries. It was said that they would arrive in the Levant knowing no language but English and that they seldom got beyond the stage of language training. One who was learning Greek at Tenos, gave up his missionary work to marry a local girl; another, who was intended for the interior of Asia Minor, decided instead to settle in the more congenial atmosphere of Smyrna; a third quietly pursued his own studies in order to equip himself for a post on his return to England.

The Rev. John Hartley, who was in Greece from 1826, was said to be an exception and there is no doubt of his vigour. But Hartley was a man who was more happy in being anti-Turk than pro-Christian. Like the Rev. Thomas Hughes, the philhellenic pamphleteer, Hartley was a survival of an earlier age when the Christian/Moslem confrontation seemed to be the most important international question of the day and when religious hatred was a respectable policy. Hartley was disposed to argue that the cruelties which the Turks had undergone at the hands of the Greeks and the bloody internal dissensions of the Ottoman Empire were the just retribution exacted by God for their failure to become Christians.17

By the late 1820s there were a dozen or so missionaries, English and American, operating in and around Greece. All the main denominations had their man to condemn and confuse the Greeks in accordance with their own especial doctrines. Virtually every town of Revolutionary Greece and every island in the Aegean was visited and numerous Lancastrian schools were established.

But the most important method of regenerating the Greek Church remained the distribution of books, 1 June 1825 was, according to the Rev. Sheridan Wilson, ‘a memorable day, a happy one for poor Greece’. On that day, after his visit to Greece, Wilson set to work a Greek press at Malta and it ran almost continuously until 1834, printing nothing else but improving works in Greek. Apart from the Bible, the Mission Press published no less than thirty-six titles.

All ages and levels of education were catered for. Numerous simple religious story books were translated: The Ladder of Learning, The Life of Robert Raikes, Tommy and Harry, The Cabin Boy, Well-Spent Penny, and Jailor’s Conversion. Watts’ Divine Songs were translated into Greek lyrics. The Pilgrim’s Progress was said to be a great favourite. For the more highly educated Keith’s Evidences of Prophecy was translated and another work, The Clergyman’s Guide, was specially composed, containing a life of St. Paul, an address to missionaries published by the Scottish Missionary Society, commentaries on the Epistles from the most up-to-date scholars, a Sacred Chronology, notes on ancient and modern philosophers, and much else besides. A version of metrical psalms was published complete with music. There were also Anglo-Greek grammars, spelling books, Greek arithmetic books, and many others.

It was an impressive accomplishment. In addition, books in Greek, mainly Bibles and tracts, continued to arrive in ships direct from England and from the United States. The Americans also established their own press at Malta ‘which never sleeps’. The Missionary Societies in England were delighted. As one of the reports stated explicitly,18 the number of copies of the Bible distributed was the best measure of the success of their missionary efforts.

But something strange was occurring which the Societies had not noticed. In early 1825—that is before the mission press at Malta began printing—it had been difficult to find anyone willing to accept a Greek Bible as a gift. The market was already glutted. Now a remarkable change had occurred. There seemed suddenly to be no limit to the number of volumes that the Greeks would take. Not only would they accept them, they would even pay for them. One missionary sold four hundred copies of the New Testament in Aegina in four days and five hundred in Hydra in the same space of time. Others described how people came on immense journeys to buy from them and how they were surrounded by children begging for books. The number of Greek books distributed in Greece and the Aegean area was immense. It is impossible to compile complete statistics, but the order of magnitude can be illustrated by tabulating a few claims made at random by some of the missionaries.

16. The head of Ali Pasha displayed to Ottoman officials and to a member of a European Embassy. Ali, his two sons, and his grandson, were put to death in 1822, and their heads buried in a row outside the walls of Constantinople. In the 1970s, I photographed the fi ve tombs, each with the distinctive turban that befi tted his rank, but they appear to have since been destroyed in road widening.

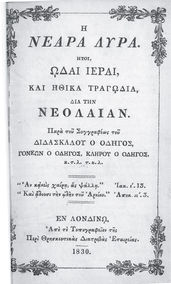

17. ‘Youth’s lyre’.

Title page and two typical illustrations from Neara Lyra [in Greek] London 1830.

English verses, mainly religous and didactic, translated into modern Greek, printed in London, and distributed by British and American Christian missionaries in Greece and the Ionian Islands. Little effort was made to accommodate either the words or the illustrations to local conditions.

Volumes printed and distributed |

Period | |

Wilson |

240,200 |

1825-1834 |

Hartley |

32,000 |

1826-1836 |

Brewer |

32,000 |

1827-1828 |

Barker |

2,500 |

Four months in 1830 |

Total |

306,700 |

This list is far from exhaustive. There are records of numerous other distributions for which no numbers are given. The total Greek population in the areas visited was probably not more than about a million and a half. There was thus probably at least one Greek book distributed for every two adult males and, of course, only a small fraction of Greeks were literate. It is clear that the missionaries, by their distribution of religious books, were practising cultural saturation bombing.

None of the missionaries found it surprising that there should be this sudden and apparently insatiable Greek demand for religious books. It was simply noted that, in 1826, ‘Greece began to show an ardent thirst for missionary co-operation’. Perhaps, but it might have occurred to even the most optimistic that this was not a complete explanation. Travellers visiting Greece before the Revolution had traversed the length of the country without seeing more than a few dozen printed books in the whole course of their travels. It was prima facie unlikely, to say the least, that thousands of wild Greeks and Albanians should now find a sudden interest in the Life of Robert Raikes, let alone evince an eager desire to purchase a small library of similar works.

The explanation was simple. Anyone who had any real interest in the manners of the country could have discovered the answer if it had occurred to him to ask the question. Paper was a rare commodity in Greece and a valuable one. A twist of paper making a cartridge for the coarse gunpowder could improve the safety and perhaps the accuracy of the primitive muskets used by most of the Greeks. Among the stores sent with Parry in the Ann were forty reams of fine paper and thirty reams of coarse paper specifically intended for making cartridges for small arms and cannon. There can be no doubt that the vast majority of Greek books sent by the missionaries went straight into personal armouries. The fact was specifically noticed by at least one traveller.19

It was explained regretfully to the Reverend Sheridan Wilson when he inspected the paltry school library at Tripolitsa that many of the books had been torn up to provide cartridges, but it never seems to have occurred to him—or to any of his fellow missionaries—that their own productions were destined for a similar fate. A charitable observer might conjecture that the missionaries knowingly accepted a high wastage rate on the theory that the effort would be worthwhile if only a few shots of the barrage hit their target. But all the evidence suggests that the missionaries sincerely believed that the crowds of despised Greeks who showed such interest in their books genuinely wanted to read them (or to have them read aloud to them). If the missionaries did have their suspicions, they did not report them to the sponsoring societies in England who continued to measure their success by the numbers of books distributed.

Insensitivity to one’s surroundings, however, is not necessarily a disadvantage to a missionary. Like Colonel Stanhope before them, the missionaries by their single-mindedness, their energy, and their absolute lack of doubt in the value of their activities, could not fail to accomplish something. There is no record of their having made converts. They had no success in substituting English customs and superstitions for the indigenous varieties which they found so appalling, but, with a few exceptions, they worked hard. Many Greeks did undoubtedly gain the rudiments of an education from schools established by the missionaries. As the numbers of the missionaries built up during the late 1820s and as more and more mission schools were established, it was natural that their influence should grow. For some years after the end of the war a few of the best men enjoyed a high reputation in Greece as teachers and genuine philanthropists, but the period was short-lived. As soon as the Greek clergy realized that the mission schools might prove a threat to their own authority, they were doomed. The famous school in Athens run by the Rev. John Hill, an American, survived for many years but only on the condition that religious subjects were not taught, and most missionaries felt that they could not help Greece on such terms. Later, the new state enacted that children of Greek orthodox parents could only be educated in schools controlled by the Greek priesthood. Soon the mission schools were closed or compelled to confine themselves to educating foreigners. And so the old-fashioned customs of the Greek Church—even including the survivals from pre-Christian times—were woven into the fabric of regenerated Greece. The influence of the new apostles, for all their high hopes and professions of faith, proved to be as ephemeral as the efforts of the other friends of the Greeks.