Introduction by Roderick Beaton

1. See most recently David Brewer, The Flame of Freedom: the Greek War of Independence, 1821-1833 (London: Murray, 2001). There are also now two excellent short histories of Greece in modern times, which include chapters on the war. See Richard Clogg, A Concise History of Greece, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002) and Thomas Gallant, Modern Greece (London: Arnold; New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).

2. Franklin, Caroline, Byron: a Literary Life (London: St. Martin’s Press, 2000); MacCarthy, Fiona, Byron: Life and Legend (London: Murray, 2002).

3. Mazower, Mark, Salonica, City of Ghosts: Christians, Muslims and Jews, 1430-1950 (London: HarperCollins, 2004), pp. 159-79, see esp. p. 166 (referring to a slightly later period).

4. Dakin, Douglas, The Unification of Greece (London: Benn, 1972).

5. Burleigh, Michael, Earthly Powers: Religion and Politics in Europe from the Enlightenment to the Great War (London: HarperCollins (2005); Sacred Causes: Religion and Politics from the European Dictators to Al Qaeda (London: HarperPress, 2006).

6. Lidderdale, H.A. (edited and translated), The Memoirs of General Makriyannis, 1797-1864 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966). For a strong critique, in Greek, of the hold which the Memoirs have often exercised over the popular and literary imagination in Greece see Giannoulopoulos, Giorgos, Διαβάζοντας τον Μακρυγιάννη: η κατασκευή ενός μύθου [Reading Makriyannis: the Construction of a Myth] (Athens: Polis, 2003).

7. See respectively: Minta, Stephen, On a Voiceless Shore: Byron in Greece (New York: Holt, 1998); MacCarthy, Byron: Life and Legend (see note 2).

8. Potter, Elizabeth, ‘George Finlay and the History of Greece’, in M. Llewellyn Smith, P. Kitromilides, and E. Calligas (eds.), Scholars, Travels, Archives: Greek History and Culture through the British School at Athens (Athens: British School at Athens, 2008).

9. Ruth Macrides, ‘The Scottish Connection in Byzantine and Modern Greek studies’, St. John’s House Papers, 4 (St. Andrews, 1992), 1-21.

10. Elli Skopetea, Το «Πρότυπο Βασίλειο» και η Μεγάλη Ιδέα. Όψεις του εθνικού προβλήματος στην Ελλάδα (1830-1880) [The ‘Model Kingdom’ and the Great Idea. Aspects of the National Problem in Greece (1830-1880)] (Athens: Polytypo, 1988) and Alexis Politis, Ρομαντικά χρόνια. Ιδεολογίες και νοοτροπίες στην Ελλάδα του 1830-1880 [Romantic Years: Ideologies and Mentalities in Greece, 1830-1880] (Athens: Mnimon, 1993).

11. Histor was founded in 1990; Historein in 1999.

12. See, respectively: Kordatos, Yanis, Η κοινωνική σημασία της Ελληνικής Επαναστάσεως (Athens: Epikairotita, 1977) [1st edition: 1924]) and Svoronos, Nikos, Τo ελληνικό έθνος: Γένεση και διαμόρφωση του νέου Ελληνισμού (Athens: Polis, 2004).

13. Respectively: Antoniou, David, Η εκπαίδευση κατά την Ελληνική Επανάσταση, 1821-1827 [Education during the Greek Revolution, 1821-1827] (Athens: Parliament of the Hellenes, 2002); Elpida Vogli, «Έλληνες το γένος»: Η ιθαγένεια και η ταυτότητα στο εθνικό κράτος των Ελλήνων (1821-1844) [Nationality and Identity in the Greek Nation State (1821-1844)] (Heraklion: Crete University Press, 2007); and Gounaris, Vasilis, Τα Βαλκάνια των Ελλήνων. Από το Διαφωτισμό έως τον Α΄ Παγκόσμιο Πόλεμο [The Balkans of the Greeks. From the Enlightenment to the First World War] (Thessaloniki, Epikentro, 2007).

14. Clogg, Richard (edited and translated), The Movement for Greek Independence, 1770-1821: a Collection of Documents (London: Macmillan, 1976).

15. See indicatively Beaton, Roderick and Ricks, David (eds.), The Making of Modern Greece: Nationalism, Romanticism, and the Uses of the Past (1797-1896) (Aldershot: Ashgate, forthcoming, 2009).

1. The Outbreak

The facts of the initial massacres and counter-atrocities are mainly taken from Gordon and Finlay with a few details from other sources, e.g. Walsh. These authors are also useful for the causes of the Revolution, as is Douglas Dakin, ‘The Origins of the Greek Revolution’, History, 1952.

2. The Return of the Ancient Hellenes

For the effects of the classical tradition on eighteenth-century European civilization a still useful general guide is Gilbert Highet, The Classical Tradition, London and New York, 1949. For the development of literary conventions about the Ancient and Modern Greeks, see Spencer. The revival of Hellenism in Greece is illustrated in many of the old travel books (see note 3 below) and in such histories of Modem Greek literature as C. Th. Dimaras, Histoire de la Littérature Néo-hellénique, Athens, 1965.

1. Quoted in full in slightly differing versions in, for example, Green, p. 272; Gordon, i, p. 183; and Raybaud, ii, p. 463.

2. It is comparatively easy to trace the extent to which famous politicians, writers, and artists were influenced by the classics, and to make some assessment of the view which they held about life in ancient times. To make a judgement about the generality of educated public opinion, it is probably preferable to consider the works of the forgotten authors, the bad poets, and the schoolmasters, and particularly the best-sellers.

The influence of Fénelon’s Adventures of Telemachus, for example, must have been out of all proportion to its value or interest, great though that is. First published in French in 1699, it is said to have gone through twenty editions in that year alone. Thereafter it was reprinted year after year in every major town in France. It was used as a school book, to teach morals, to teach language and to teach history. It was abridged, selections were published separately, it was put into verse, all manner of illustrations were added. In France alone there were well over a hundred reprintings during the eighteenth century. Dozens of editions also appeared in English, German, French, Italian and other languages. Similarly, many thousands of European readers must have ploughed their way through Barthélemy’s Travels of the Young Anacharsis in Greece. It first appeared in French in 1788 and was regularly reprinted in the main European languages. New French editions appeared almost every year, usually simultaneously in quarto, octavo, and duodecimo to cater for a wide range of pockets. Another work of the same type, Lantier’s Travels of Antenor which was first published in 1796, was in its fifteenth edition by 1821. These were fictional works, in the style of novels but written not so much for the story as for the information and atmosphere about the ancient world which they contained.

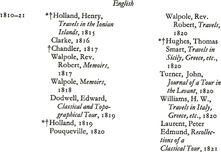

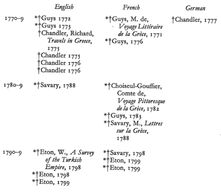

3. The following table gives an indication of the opportunities available in Western Europe to learn of the conditions of Greece in the half-century before the Revolution. I have listed the separate editions which I have been able to identify. Only books which contain some description of the condition of Modern Greece are included. I have not listed works which are confined to descriptions of the antiquities, picture books, or travel books which ignore the Greeks or mention them only incidentally. I give the title in the language in which the book was first published. Those marked with † consciously identify the Modern with the Ancient Greeks. Those marked * discuss or advocate the possibility of a revolution.

The only books of consequence which attacked the philhellenic conventions of the time were Cornelius de Pauw, Recherches Philosophiques sur les Grecs, Berlin and Paris, 1787; English translation 1793; and Thomas Thornton, The Present State of Turkey, two editions, 1807. De Pauw had never visited Greece.

3. The Regiment

The sources for the history of the Regiment are sparse compared with later periods. Some useful material can be found in Byzantios, Raybaud, Persat, and Humphreys’ First Journal.

The anonymous author of an interesting series of articles in the London Magazine for 1826 and 1827, entitled, ‘Adventures of a Foreigner in Greece’, was also one of the earliest volunteers. I have attributed the authorship of this piece to the Italian Brengeri who is named by Gordon, i, p. 459, as one of the four Philhellenes who endured the first siege of Missolonghi. The siege is described from his own experience by the author of the articles. Also, it is known from other references in the Gordon Papers that Brengeri was a Roman and that he came to England, both points shared by the author of the articles.

1. Quoted in the Examiner, 1821, p. 232.

2. Ibid., p. 372.

3. Ibid., p. 689.

4. Ibid., p. 372.

5. Ibid., p. 456.

6. Ibid., p. 631.

7. Quoted ibid., p. 632.

8. Raybaud, i, p. 422.

9. Humphreys, First Journal, p. 29.

10. Brengeri, i, p. 462.

11. Aschling, p. 28.

12. Raffenel, i, p. 10.

13. For example Brengeri, i, p. 462. Hypsilantes himself encouraged this rumour. Humphreys, First Journal, p. 55.

14. Examiner, 1821, p. 242. This story is noticed in an enthusiastic philhellenic letter by Alexander Pushkin of March 1821. See The Letters of Alexander Pushkin, ed. J. Thomas Shaw, Bloomington and Philadelphia, 1963, i, pp. 80 ff. Pushkin joined a masonic lodge in part to help the Greek cause and his friend Karlovich Küchelbecker seriously considered volunteering, but by 1824 Pushkin was disillusioned.

15. See his Mémoires.

16. See his First Journal.

17. Emil von Z. See Byern, p. 108. This Philhellene cannot be definitely identified with any of the Poles whose names are known.

18. Mierzewsky, killed at Peta. Elster, Fahrten, p. 319.

19. Raybaud, i, p. 269.

20. Brengeri, i, p. 466.

21. Ibid., pp. 462 ff.

22. Humphreys, First Journal, p. 40.

23. Voutier, Mémoires, p. 171.

24. Christian Müller, Preface. The two Englishmen are described as Mr. N. and Mr. S.

25. Not identified. Raybaud, i, p. 367.

26. Identified only as G. Raybaud, i, p. 368.

27. Brengeri, i, p. 467.

4. Two Kinds of War

Again, the main philhellenic sources are Brengeri, Raybaud, Persat, and Humphreys, First Journal.

1. See, for example, Brengeri, i, p. 469.

2. Raybaud, i, p. 290.

3. Examiner, 1821, p. 632.

4. Phrantzes, quoted by Finlay, Greek Revolution, i, p. 263.

5. Humphreys, First Journal, p. 28; Raybaud, i, p. 397.

6. Brengeri, i, p. 469.

7. Gordon who saw the aftermath dared not describe the horrors in his history (i, p. 245). He did, however, relate his experiences to Dr. Thomas whom he met at Zante soon afterwards and they were reported to London. Colonial Office Records 136/1085 reproduced as an Appendix to Humphreys, First Journal.

8. This surprising detail is asserted emphatically by Brengeri, ii, p. 41, and there is no reason to doubt it.

9. Persat, p. 100.

10. Wilhelm Boldemann from Grabow in Mecklenburg. LeFebre, p. 9, specifically says he committed suicide. Others say he was left to die of neglect.

11. LeFebre, p. 21.

5. The Cause of Greece, the Cause of Europe

The books by Dimakis and Dimopoulos discuss the reaction of the French press to the news from Greece during the Revolution. One of the main sources for the state of public opinion is the pamphlet literature, and I have tried in Note 7 to enumerate these works and draw a few general conclusions.

1. Many contemporary writers give examples of the transformation of the news, e.g. Aschling, Raybaud, and Waddington. Sir William Gell published his Narrative of a Journey in the Morea in 1823 specifically to combat the false newspaper stories.

2. Examiner, 2 July 1826, quoting Sismondi.

3. Elster, Fahrten, pp. 219 ff., recalling a quotation from Goethe’s Faust.

4. See Note 8 to Chapter 26.

5. See Irmscher, Arnold, and Gaston Caminade, Les Chants des Grecs et le Philhellénisme de Wilhelm Müller, Paris, 1913.

6. Translated from Constitutionnel, 26 July 1821, quoted by Dimopoulos, p. 60.

7. Translated from de Pradt, De la Grèce dans ses Rapports avec l’Europe, Brussels, 1822.

The pamphlet literature published in Western Europe during the Greek War of Independence is huge. All but a tiny proportion of these works were intended to promote the Greek cause. A full bibliography is gradually being built. Copies of most of the titles are not to be found outside a handful of libraries and the sentiments of such works are predictably uniform. It might be useful, in any case, as an indication of public opinion, to have the following table of the numbers of pamphlets which are known to have been published in the three main European languages. I have included only political pamphlets and appeals published as separate works in their own right, excluding histories, memoirs, biographies, books of verse and articles in magazines and newspapers. When a pamphlet went into a second edition or was translated I have counted these as if they were new works. The great majority (except in England) had apparently one edition only, although one or two especially influential works went to as many as four editions. It is difficult to draw more than very general conclusions from the figures. The practice of conducting political argument by pamphlet was not equally developed in the countries concerned and they cannot be directly compared. In addition it is easier to be confident that the English and French figures are nearly complete, since many of these were printed for national distribution in London or Paris, than it is with respect to the German pamphlets, which were published independently for small circulation in several cities. Nevertheless, the figures do seem to illustrate a few points about the state of public opinion. They seem to confirm, for example, the success of the censor and the disillusionment with philhellenism in the German-speaking countries which occurred after the return of the early volunteers; and the astonishing revival of philhellenism which occurred in France alone in 1825 and 1826. They also seem to lend weight to the view that philhellenism was not as strong in England as in Continental Europe.

German |

English | ||

1821 |

16 |

14 |

2 |

1822 |

15 |

23 |

10 |

1823 |

4 |

10 |

10 |

1824 |

10 |

4 |

6 |

1825 |

22 |

2 |

-- |

1826 |

31 |

3 |

3 |

1827 |

14 |

1 |

-- |

------ |

------ |

------ | |

112 |

57 |

31 |

8. J.-G. Schweighauser, Discours sur les Services que les Grecs ont rendus à la Civilisation, Paris, 1821.

9. Giraud de la Clape, ex-étudiant en droit, Appel aux Français en faveur des Grecs, Paris, 1821.

10. For the early philhellenic movements in Britain see Penn and Dakin.

11. Rev. T. S. Hughes, An Address to the People of England in the Cause of the Greeks, London, 1822.

12. Thomas Lord Erskine, A Letter to the Earl of Liverpool on the Subject of the Greeks, London, 1822.

13. Address in behalf of the Greeks, Edinburgh, 1822.

14. Rev. T. S. Hughes, Considerations upon the Greek Revolution, London, 1823.

15. Charles Brinsley Sheridan, Thoughts on the Greek Revolution, London, 1824.

16. Quoted in Booras, p. 159, and elsewhere.

17. Larrabee, p. 55.

18. Ibid.

19. For the politics of philhellenism in Prussia and elsewhere in Germany, see Irmscher.

20. From the English translation, The Cause of Greece, The Cause of Europe, published anonymously in London in 1821.

21. Translated from Karl Iken, Hellenion, Leipzig, 1822.

22. Quoted by Barth and Kehrig-Korn, p. 95.

23. Translated from the second edition of Wilhelm Traugott Krug, Griechenlands Wiedesgeburt, Leipzig, 1821.

6. The Road to Marseilles

1. Some details of the eight expeditions are given in Appendix II. The members who have given accounts of their experiences are

Authors | |

St. Lucie: |

Bellier de Launay, Koesterus, LeFebre. |

Pegasus: |

Kiesewetter, Treiber. |

St. Marie: |

Byern, Harring, Krøyer, Lieber, Lübtow, Rosenstiel, Stabell, Schrebian, Striebeck. |

Madonna del Rosario: |

Feldhann. |

La Bonne Mère: |

Albert Müller, Stauffer, Elster, Jourdain. |

Duchesse d’ Angoulême: |

Dannenberg, Lessen, Author of Tagebuch, Tübingen 1824. Author of Tagebuch, Dinkelsbühl, 1823. |

Félicité Renouvelée: |

Bollmann. |

St. Jean Battiste: |

Kotsch, Gottfried Müller. |

Most of these authors describe their journeys to Marseilles. There is also useful material in Jarvis, who set off in a Swedish merchant vessel.

2. Elster Fahrten, i, p. 219.

3. Kiesewetter.

4. Schrebian.

5. Feldhann. The book was published from letters. Feldhann himself was killed at Peta.

6. Author of Tagebuch of Dinkelsbühl.

7. Dannenberg.

8. Harring. Harring survived his experiences in Greece and on his return resumed his career as painter, poet, and dramatist in Italy, Switzerland, Germany and elsewhere. He served for a time as an officer in the Russian army but by the early 1830s he had become a professional revolutionary. Thereafter he moved restlessly from country to country through Europe, South America and the United States, constantly being driven out by the authorities. Half genius, half madman, he eventually committed suicide in London in 1870 by eating phosphorus matches.

9. Translated from Krøyer, p. 1.

10. Harring, p. 13.

11. Penn, quoting Morning Chronicle, 9 November 1821.

12. Ibid.

13. Gottfried Müller, p. 67.

14. Charles Tennant, A Tour through Parts of the Netherlands, Holland, Germany etc., London, 1824, ii, p. 96.

15. Krøyer, p. 22.

16. Ibid., p. 27. Their names were Remi and Brugnatelli.

17. Rothermel.

18. Hochgesang.

19. Franz and Benjamin Beck who both died at Missolonghi in November 1822.

20. The twin brothers Fels from Leipzig. One, an apothecary, was killed at Peta; the other, a merchant’s clerk, survived the battle but later returned to Greece and died at Missolonghi in September 1824. Deiss, a sixteen-year-old from Weimar, died of disease in 1822 at Anatoliko.

21. Josef Wolff, killed at Peta.

22. Benoit. According to Bellier de Launay, he later joined the Turks but he was one of the authors of a curious letter begging a passage home from the French Navy, quoted in Le Maître from the French naval archives, and we may doubt Bellier’s story.

23. Wilhelm Heinrich Seeger, killed at Peta. His brother also died in Greece.

24. Johann Andreas Staehelin.

25. Albert Müller.

26. Johann Kohlermann.

27. Heinrich Stammler, committed suicide in Greece, July 1822.

28. Mignac, who killed Baron Hobe in the duel at Comboti (see p. 96) and was himself killed at Peta.

29. Friedrich Sander, killed at Peta.

30. Unidentified. Described by Harring, p. 17. Probably Krusemark, killed at Peta.

31. Said to be the wife of Onate who came in the Madonna del Rosario. Elster and Albert Müller also mention the wife of Toricella setting off dressed as a man; she was said to have died in Greece before Peta.

32. Descheffy, killed at Peta.

33. Eduard von Rheineck who confided this detail to Collegno during the siege of Navarino in 1825. Rheineck never returned to Germany but, unlike most of his contemporaries, lived out a long and successful career in Greece and now lies in a magnificent tomb in Athens cemetery.

34. von Katte was the name he used. His real identity is unknown.

35. Johann Jakob Meyer, one of the most famous of all Philhellenes. He set up a dispensary at Missolonghi, married a Greek girl, and adopted the Greek Orthodox religion. He became editor of the Greek Chronicle established by Stanhope and died in the fall of Missolonghi in April 1826. See pp. 187 and 242.

36. Frank Abney Hastings. See Chapter 29.

37. The fullest accounts of the Alepso incident are Tagebuch of Dinkelsbuhl, Lessen, and Tagebuch of Tubingen.

38. Elster, Fahrten, i, p. 231 reports some of the details. The French naval officer was Jourdain who was later to be closely involved in the affair of the Knights of Malta. His own book contains little autobiographical information. The commander of the Greek Navy was Scholl.

39. This incident is described in numerous accounts, for example, Elster, Harring, Stabell, Striebeck, Krøyer.

40. Krøyer.

41. For Normann’s earlier career see Byern and the short biography by Albert Schott in Taschenbuch für Freunde der Geschichte des Griechischen Volkes, Heidelberg, 1824.

42. Feldhann, killed at Peta.

43. Examiner, 1822, p. 72.

44. The four Frenchmen were Persat, Micolon, Delaurey, and Paulet. The incident is described from the French side by Persat. There are descriptions of the same incident from the German side by Dannenberg, by the author of the Tagebuch of Tübingen, and by Lessen.

45. LeFebre, p. 29.

46. Bollmann.

The main documents relating to the history of Chios have been published in a magnificent set of volumes by Philip Argenti. The Massacres of Chios, London, 1932, transcribes the chief contemporary accounts of the massacre in the diplomatic archives of several countries. Many of the details of events in Constantinople are supplied by Walsh and Waddington.

8. The Battalion of Philhellenes

The chief sources for this chapter are the authors listed in Note 1 to Chapter 6 together with Brengeri, Raybaud, and, where he can be trusted, Voutier.

1. This incident, which happened when the St. Jean Battiste arrived, is described by Gottfried Müller and Kotsch.

2. See, for example, Byern, p. 58.

3. Lieber’s narrative breaks into Latin at this point (p. 73) to spare the blushes of his female readers who were presumed not to have the education to understand it.

4. See, for example, Stabell, p. 21.

5. Gottfried Müller, p. 158.

6. Georg Grauer, a lieutenant from Württemberg, who came in the St. Marie.

7. Karl von Descheffy, killed at Peta.

8. An unidentified Alsatian.

9. Both Moring and Mulhens are recorded as duelling with d’André who claimed to be a marquis.

10. Stabell, pp. 40 ff.

11. Striebeck, p. 95.

12. Stabell, p. 50; Striebeck, p. 100.

13. Gustav Reichard from Vienna. Other accounts say from Frankfurt.

14. Hans von Jargo, a lieutenant from Berlin.

15. Anemat.

16. Hastings Diary, 6 July 1822. Hastings Papers.

17. The number is variously estimated. Striebeck, p. 154, gives two hundred and twenty. Stauffer, p. 53, gives as many as three hundred.

18. See especially Byern, p. 144. Friedel eventually established himself as an engraver in London and married the sister of Hodges, one of the artificers at Missolonghi with Lord Byron.

19. Waldemar von Qualen, killed in Thessaly in 1822.

20. See especially Byern, p. 135.

21. For the establishment of the Battalion see especially Striebeck, p. 208, Kiesewetter, p. 16, Schrebian, p. 112, Byern, p. 99, and Raybaud, ii, p. 238.

22. Raybaud, ii, 242.

9. The Battle of Peta

1. Rev. Robert Walsh, Narrative of a Journey from Constantinople to England, 1828, p. 63.

2. Vincenzo Gallina. See Raybaud, ii, p. 167.

3. These incidents are related by Mengous, pp. 185 ff., and Elster, Fahrten, i, pp. 328 ff.

4. Brengeri, iv, p. 340.

5. There are several accounts of the duel between Hobe and Mignac, the fullest in Elster.

6. Johann Bohn.

7. C. W. Van Dyck, a captain of cavalry. He returned safely to Holland.

8. Monaldi. See especially Brengeri, iv, p. 347.

9. Johannsen.

10. The wife of Toricella.

11. The best first-hand accounts of the battle are Raybaud, Brengeri, and Kiesewetter.

12. I include the following:

German |

Seeger |

Mignac |

Bahrs |

Stael Holstein |

Seguin |

Beyermann |

Suri |

Viel |

Dieterlein |

Süssmilch |

|

Eben |

Teichmann |

Poles |

Eisen |

Wetzer |

Dieselsky |

Fels |

Wolff |

Dobronowski |

Feldhann |

Kosinsky | |

Heise |

Koutselewsky | |

Kaisenberg |

Italian |

Miolowitch |

Krusemarck |

Batilani |

Mierzewsky |

Lasky |

Briffari |

Mlodowsky |

Lauricke |

Dania |

Paulowsky |

Lucä |

Fozzio |

Tabernocky |

Mandelslohe |

Mamiot |

|

Maneke |

Plenario |

Swiss |

Nagel |

Rocini |

Chevalier |

Oberst |

Tarella |

Koenig |

Oelmeier |

Tassi |

Wrendli |

Ohlmeier |

Tirelli |

|

Range |

Toricella |

Dutch |

Rüst |

Viviani |

Huismans |

Sander |

||

Sandman |

Hungarian | |

Schmidt |

French |

Descheffy |

Schneide |

Chauvassaigne |

|

Schröder |

Frêlon |

Mameluke |

Seeger |

Guichard |

Daboussi |

13. Karl Weigand from Würtzburg, Friedrich Schweicart from Baden, and probably Deiss, a schoolboy from Weimar at this time.

14. The brothers Benjamin and Franz Beck.

15. J. Winterholler.

16. H. Pruppacher from Zürich.

17. Known only as Johann.

10. The Triumph of the Captains

This chapter is mainly taken from the usual sources for the general history of the war, especially Gordon, Finlay, and Waddington. The account of the fall of Nauplia by Kotsch, who was present, contradicts the usual version in some particulars. Brengeri gives an interesting account of the first siege of Missolonghi.

11. The Return Home

Almost all the surviving Philhellenes who left accounts of their experiences devoted a good deal of their book to their adventures on the way back from Greece: e.g. most of the authors referred to in Note i to Chapter 6, plus Brengeri; Humphreys, First Journal; Persat; Aschling.

1. Elster, Fahrten, ii, p. 35. The names of the two dead Philhellenes are given as Bollini and Daminski. Elster’s account is, however, very fanciful at this point and is contradicted by more reliable sources.

2. Stabell, p. 89.

3. Striebeck, p. 234.

4. Gottfried Müller, p. 46.

5. Elster.

6. Kotsch, p. 60

7. Lieber mentions the Italian and two Frenchmen without identifying them. The doctor from Mecklenburg, Boldemann, has already been referred to (Note 10 to Chapter 4). The other German from Hamburg mentioned by LeFebre as committing suicide may be the same as the dancing master said by some to be from Rostock, Heinrich Stammler.

Dannenberg, p. 120, mentions the Wurttemberg officer who tried to kill himself. He gives his name as H—n, perhaps Hahn. C. M. Woodhouse, The Philhellenes, London, 1969, p. 121, suggests that the malaria which infected the area immediately north of the Gulf of Corinth produces acute depression in its victims, which often leads to suicide.

8. See, for example, Lieber, pp. 66, 113; Schrebian, p. 68.

9. Finlay, Adventure. This article is written in the first person and contains a number of points intended to make the reader think that the anonymous author is George Finlay himself, but he was not in Greece at the time. A letter from Finlay to the editor of Blackwoods of 21 September 1842 (National Library of Scotland MSS. 4061) claims that ‘the facts happened as nearly as they are narrated and the persons whose names occur would almost feel inclined to vouch for the perfect accuracy of the tale’.

10. Monaldi. See p. 97.

11. Brengeri, iv, p. 351.

12. Unidentified. Kotsch, p. 27.

13. Dannenberg, p. 207.

14. For example Mari and St. André. See pp. 89 and 235.

15. August Christian von Schott, step-brother of Albert Schott, President of the Stuttgart Greek Society.

16. Waddington, p. 1.

17. Aschling, p. 88

18. Examiner, 1822, p. 551.

19. I include the following: Aschling, Stabell, Christian Müller, Lieber, Schrebian, LeFebre, Bollmann, Dannenberg, Kiefer, Koesterus, Lessen, Kotsch, Rosenstiel, Stauffer, Kiesewetter, Anonymous of Dinkelsbuhl, Anonymous of Tubingen, translations of Christian Müller published in London and Paris, a translation of Lieber published in Amsterdam, and a translation of Stabell published in Leipzig. The work by Gottfried Müller published in Bamberg is of the same type but since it did not appear until 1824, I have omitted it. There were also numerous warnings in the newspapers, e.g. by Baron Wintzingerode at Munich.

12. The German Legion

The main source for the fortunes of the German Legion is the querulous account by Kiefer who was a member of the expedition. Other details are supplied by Gordon, Millingen, Stanhope, Kotsch, and N. Speliades Άπομνημονεύματα, Athens, 1851, i, pp. 344 ff.

1. Lieber, p. 157. In the United States he became a distinguished political philosopher and university teacher. He was the founder of the Encylopedia Americana.

2. A copy of Kephalas’ proclamation is reproduced in Statuts dela Societad d’ajüt per ils Grecs in Engadina, 1822.

3. The anonymous author of the Tagebuch published at Dinkelsbühl in 1823.

4. Amand Gysin.

5. Gottfried Müller, the Philhellene who survived, related this incident. He

mentions that his companion who died, Georg Dunze, had never left Hamburg, his native town, before he came to Greece.

6. Millingen, p. 28.

13. Knights and Crusaders

The attempts of speculators to persuade the Greeks to accept loans are described by Dakin, and there are numerous references in Levandis, Dalleggio, the Colonial Office records and elsewhere. The affair of the Knights is described in detail by Jourdain, who was personally deeply concerned.

1. British Library Additional Manuscripts 30, 130, f. 73.

2. References to the later activities of the Knights are in Lauvergne, Hodges, and Blaquière, Second Visit. See also G.-J. Ouvrard, Mémoires, Paris, 1827, iii, pp. 353 ff.

14. Secrets of State

The British interception service at this period is described in Kenneth Ellis, The Post Office in the Eighteenth Century, London, 1958. The Ionian Island interceptions are among the Colonial Office Records. Some of the most important documents are in Dakin’s collection, British Intelligence. Quotations from the French secret police archives which show the concern with philhellenism are given in Persat and Débidour.

There are interesting references in M. Froment, La Police Dévoilée depuis la Restauration, Paris, 1829, and Le Livre Noir de MM. Delavau et Franchet, Paris, 1829.

For philhellenism in English literature Spencer is an excellent guide, and much of the story of the British Philhellenes is given by Dakin.

1. There is much about Gordon in Dakin, British and American Philhellenes.

2. Hastings’ papers are in the Library of the British School at Athens. Finlay’s Biographical Sketch is the fullest account, see also Chapter 28.

3. Jarvis’ papers are published. See also Chapter 30 for Jarvis’ later activities in Greece.

4. Humphreys, First Journal and other works.

5. Haldenby does not appear in Dakin’s list. He is described by the author of the Tagebuch of Tübingen. It is also clearly Haldenby who is described by Came, pp. 533 ff.

6. Hausmann from Colmar.

7. E. His full name is unknown, Carne, pp. 545 ff.

8. N. and S. Christian Müller, p. 6.

9. Hoistin mentioned by Elster, Fahrten, ii, p. 32. I doubt whether he existed.

10. Finlay, Adventure. See Note 9 to Chapter 11.

11. C. Brinsley Sheridan, Thoughts on the Greek Revolution. Pamphleteer XLVIII, 1824, p. 424 ff.

12. Talma, p. 7.

13. Quoted by Gordon, ii, p. 85.

14. Printed prospectus among Gordon papers.

15. Charles Brinsley Sheridan, The Songs of Greece, London, 1825, p. 98.

16. Henry Renton to Gordon, 22 February 1825, Gordon Papers.

17. Thomas Moore, Memoirs, Journal, and Correspondence, London, 1853, p. 88.

18. Bowring to Hobhouse 24 December 1823. British Library Additional Manuscripts 36, 460 f. 178.

19. Examples from which the quotations are taken are in The Works of Jeremy Bentham, edited by John Bowring, Edinburgh, 1843, and Dalleggio.

16. Lord Byron Joins the Cause

For the details of Byron’s life there is no substitute for Marchand who has made best use of the original documents.

1. Blaquiere to Reeves to be passed to Lord Liverpool, 28 October, 1823. British Library Additional Manuscripts 38, 297 f. 166.

2. Blaquiere to Byron 28 April 1823. Copy sent to Gordon by Bowring with the news that Byron had told the Committee that he would proceed instantly to Greece if the accounts contained in Captain Blaquiere’s letter were confirmed in his next communication. Gordon Papers.

3. This incident is described in Gamba and in letters by Byron. The two men cannot be identified for sure, although one was perhaps Adolph von Lübtow who was later killed at Missolonghi.

4. Trelawny and Hamilton Browne.

17. ‘To Bring Freedom and Knowledge to Greece’

The official papers of the London Greek Committee are in the National Archives at Athens. They were used by Penn and a short account of some of the more interesting documents is given by E. S. De Beer and Walter Seton in The Nineteenth Century, September 1926. There are many relevant documents among the Gordon papers including copies of some of the Committee’s papers.

See also Gamba, Parry, Millingen, Bowring, Stanhope, and, among later writers, Dakin and Marchand. These works also provide the main sources for the following three chapters.

1. Blaquiere to Hobhouse from Marseilles, 27 March 1823. British Museum Additional Manuscripts 36, 460 f. 24.

2. Byron to Bowring 12 May 1823. Quoted in Thomas Moore: Letters and Journals of Lord Byron, London, 1830, ii, pp. 655 ff.

3. See Note 1 to Chapter 15.

4. Parry is one of the best of the contemporary accounts. He was assisted in writing his book by Thomas Hodgskin. See my note, ‘Postscript to The Last Days of Lord Byron’, Keats-Shelley Journal, 1970.

5. William Gill, E. Fowke, James Grubb, W. Watson, J. M. Hodges, Robert Lacock, James Hampton, and Richard Brownbill.

6. Hon. Leicester Stanhope, Press in India, London, 1823, p. 193.

18. Arrivals at Missolonghi

1. This conclusion is explicitly confirmed by Trelawny, Recollections, p. 201.

2. The War in Greece, 1821; Greece in 1824, 1824.

3. Quoted in Marchand, iii, p. 1136.

19. The Byron Brigade

1. Gamba, p. 157.

2. Ibid., p. 201.

3. There were at least two Philhellenes called Sass. According to the ships’ lists Adolph Sass came in the Félicité Renouvelée and Karl Sass came in the Duchesse d’Angoulême. For Adolph see Barth and Kehrig-Korn, p. 214, and Parry, p. 57. There is a tombstone at Missolonghi said to be of Gustav Adolph Sass who died in 1826, and there is some evidence that a Swede called Sass was drowned there in 1826.

Borje Knöss, ‘Officiers Suédois dans la Guerre d’lndépendance de la Grèce’ in I’Hellénisme Contemporain 2me série, 3me année, Fasc. No. 4, pp. 319 ff., quotes letters of 1824 and 1825 from contemporary Swedish newspapers allegedly by Adolphe de Sass who is said to have died in 1829.

4. Dakin, British and American Philhellenes, sets out most of the information that can be gleaned about this group.

5. Larrabee, pp. 145 f.

6. Maitland to Colonial Secretary, Colonial Office Records, CO. 136/1086 f 379.

7. Barth and Kehrig-Korn, p. 118.

8. Ibid., p. 175 from Treiber.

9. Ibid., p. 177.

10. Millingen, p. 183; Walsh, i, 172; Wilson, p. 485; Literary Life and Correspondence of the Countess of Blessington, ed. R. R. Madden, London, 1855, ii, p. 127; several letters are quoted in Blaquiere, Second Visit. See also the remarks of Charles Armitage Brown quoted in The Keats Circle, ed. Hyder Edward Rollins, Harvard, 1948, i, pp. lvii f

11. Palma, p. 2.

12. Krøyer, p. 84.

13. Treiber, p. 130.

14. Bulwer, p. 123.

15. Emerson, Letters, i, pp. 39 ff. Compare Howe, Letters and Journals, pp. 98f. and p. 112. Wright’s travelling companion, Railton, was at work on The Antiquities of Athens begun by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett.

16. Wilson, p. 495. Incidentally Wilson’s chronology goes wrong at this point in his book. He could not have seen the body of Lord Byron at Zante at the end of his Greek tour of 1824 as he says.

17. See Doris Langley Moore, The Late Lord Byron, London, 1961.

18. The Life, Writings, Opinions and Times of the Right Hon. George Gordon Noel Byron … by an English Gentleman in the Greek Military Service, and Comrade of His Lordship, London, 1825.

20. Essays in Regeneration

The principal source for Stanhope’s activities is his own book and the quotations are from Stanhope, except where otherwise noted. The Stanhope Papers show that he drastically edited the material for his book.

1. See, for example, Gordon, ii, p. 180.

2. Sir William Gell, Narrative of a Journey in the Morea, London, 1823, p. 303.

3. Gordon, ii, p. 121.

21. The New Apostles

The main sources are Anderson, Brewer, Hartley, and especially Wilson. The curious work by Kennedy throws light on the point of view of the missionaries, and also incidentally reveals something of the charm of Lord Byron. There is much of interest in Larrabee. Quotations are from Wilson except where otherwise noted.

1. Stanhope, p. 105.

2. Rev. William Jowett, Christian Researches in the Mediterranean, London, 1824, p. 255.

3. Wilson, p. 203.

4. Ibid., p. 338.

5. Hartley, p. 4.

6. Ibid., p. 5.

7. Anderson, p. 31.

8. Hartley, p. 79.

9. Wilson, p. 400.

10. Ibid., p. 207.

11. Parry to the London Greek Committee, 24 February 1824. Gordon Papers.

12. Thomas Moore, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron, London, 1830, ii, p. 721.

13. Swan, i, pp. 189 f; ii, p. 34.

14. Ibid., i, 103.

15. Swan, i, p. 141.

16. Slade, ii, p. 459.

17. Hartley, p. 35.

18. Fifteenth Report of the British and Foreign Bible Society, p. 212, quoted in i, p. 190.

19. Slade, ii, pp. 462 f.

22. The English Gold

For the loans, see especially Dakin, Levandis, and Bartle; for the economic background, Leland Hamilton Jenks, The Migration of British Capital to 1875, New York and London, 1927.

1. Jenks, op. cit., p. 49.

2. Figures from the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, June 1878, pp. 313 ff.

3. Bowring to Hobhouse, 24 December 1823. British Library Additional Manuscripts 36, 460 f. 178.

4. Blaquiere, Greek Confederation, p. 28.

5. Blaquiere, Greek Revolution, p. 302.

6. Ibid., p. 302.

7. Ibid., p. 302.

8. Ibid., p. 301.

9. Ibid., p. 305.

10. Ibid., p. 303.

11. Ibid., p. 303.

12. Blaquiere, Second Visit, p. xiv.

13. Quoted by Levandis, p. 15.

14. Examiner, 18 December 1824.

15. Ibid., 22 February 1824.

16. Bowring to Gordon, 21 June 1824. Gordon Papers.

17. Bowring to Hobhouse, 18 July 1824. British Library Additional Manuscripts 36, 460 f. 242.

18. Humphreys to Gordon, 17 August 1824. Gordon Papers.

19. New Monthly Magazine, xii, 1824, p. 515.

20. Bulwer.

21. Examiner, 5 March 1826.

22. Waddington, p. 1.

23. Blaquiere, Greece and Her Claims.

24. Quoted by Bartle, p. 70, from a MS. in the John Rylands Library.

25. Bartle, p. 71.

26. Quoted in Quarterly Review, January 1827.

23. The Coming of the Arabs

1. Wilson, p. 273.

2. Gordon, ii, p. 182.

3. See, for example, Stanhope, p. 376; Bulwer, p. 116.

4. Talma, p. 10.

5. Wilson, p. 274.

6. Finlay, Greek Revolution, ii, p. 39.

7. There is a full biography of Sève by Marie E. Aimé Vingtrinnier, Socman Pacha, Paris, 1886. Several contemporary writers give further details, notably Lauvergne and Swan.

8. For Doctor St. André see J. S. Mangeart, Souvenirs de la Morée, Paris, 1836, p. 29.

9. Collegno’s diary of the siege of Navarino, Ottolenghi, pp. 242 ff.

10. Swan, ii, p. 240.

11. See William St Clair, Trelawny, the Incurable Romancer, 1974, published after the first edition of the present work, which takes account of the important article by Lady Anne Hill, ‘Trelawny’s Family Background and Naval Career’ in the Keats-Shelley Journal, 1956. Trelawny’s own books and letters have to be treated with scepticism. The most prominent other romantic Byronists of this period are George Finlay in his early phase and William Humphreys—see especially the lush descriptions in the latter’s Adventures of an English Officer. There are some revealing passages in that strange compilation, Sketches of Modern Greece by a Young English Volunteer.

12. There are numerous accounts of the affair in the cave. Documents in Jarvis leave no doubt about the plot. Humphreys, Adventures of an English Officer, confirms the outline of Trelawny’s own account.

13. Quoted by William Mure, Journal of a Tour in Greece, Edinburgh and London, 1842, i, p. 167.

14. MacFarlane, ii, p. 53.

15. Emerson, Picture of Greece, i, p. 282.

16. Alphonse Nuzzo Mauro, La Ruine de Missolonghi, Paris, 1836, p. 16.

17. Quoted by W. Alison Phillips, The War of Greek Independence, London, 1897, p. 203.

24. The Shade of Napoleon

For the life of Fabvier see especially Débidour who had access to much primary material. Other details are in Davesiès de Pontes and Grasset. A pamphlet published in Paris in 1828, De l’Empire Grec et du Jeune Napoléon, throws an interesting light on the aspirations of the Bonapartists in Greece. The author argues that an independent Christian empire should be established as a bulwark against the Russians. To survive, such an empire would need a stiffening of European immigrants and these could be provided by the warlike Bonapartists and failed revolutionaries of Europe. The son of Napoleon could be appointed emperor, so ensuring that the new state did not fall too far under the influence of any of the great European powers.

1. Humphreys to Gordon, 21 December 1823, Gordon Papers.

2. Stanhope, p. 27.

3. Villeneuve, p. 9.

4. Le Livre Noir de MM. Delavau et Franchet, Paris, 1829, iii, pp. 347 ff.

Gibassier was put to death by the Turks after being captured near Athens in 1827.

5. Ibid., Froment, La Police Dévoilée depuis la Restauration, Paris, 1829, i, p. 168. Bourbaki was killed near Athens in 1827.

6. Berton was met by Humphreys. See Humphreys, Adventures of an English Officer.

7. Howe (Letters and Journals, p. 250) was present at Bonaparte’s death on board the Hellas.

25. ‘No Freedom to Fight for at Home’

The title of this chapter is taken from a poem which Lord Byron sent to Tom Moore about his own activities in support of the Italian liberals in 1820:

When a man hath no freedom to fight for at home,

Let him combat for that of his neighbours;

Let him think of the glories of Greece and of Rome,

And get knock’d on the head for his labours.

To do good to mankind is the chivalrous plan,

And is always as hotly requited;

Then battle for freedom wherever you can,

And, if not shot or hang’d, you’ll get knighted.

First-hand accounts by Italian Philhellenes are surprisingly sparse. I have used those of Brengeri, Pecchio, and Palma. Gamba’s book is concerned solely with his first visit to Greece. Collegno’s diary of the siege of Navarino is in Ottolenghi. There are also passages of especial interest in Morandi.

1. Brengeri, vi, p. 84. The name is supplied from Persat, who was involved in the project on his return from Greece.

2. Memoirs of General Pepe, London, 1846, iii, p. 251.

3. Brengeri, i, p. 466.

4. Ibid., vi, p. 91.

5. Letter of Rossaroll, 10 December 1824, CO. 136/33 f. 28.

6. Palma, p. v.

7. Pecchio, Picture of Greece, ii, p. 10.

8. Millingen, p. 241.

9. Dalleggio, p. 121.

10. Froment, op. cit., i, p. 278.

11. For example, the author of Sketches of Modern Greece, i, p. 216.

12. Quoted in Œuvres de M. Victor Cousin, Paris, 1849, iii, p. 414.

13. Palma, p. vii.

14. Pecchio, Picture of Greece, ii, pp. 190 ff.

15. Ibid., ii, p. 7.

16. Morandi, pp. 75 ff.

17. Dalleggio, p. 124.

18. Collegno, Rossaroll, Santa Rosa, Palma, Romei, Barberis, Barandier, Aimino, Morandi, Ritatori, Isaia, Gambini, and Ferero are all said to have received a death sentence. Pisa, Porro, Pecorara, Pecchio, Andrietti, and Giacomuzzi may also have been condemned.

19. Hahn, quoted in Barth and Kehrig-Korn, p. 199.

20. Georges Douin, Une Mission Militaire auprès de Mohamed Aly, Cairo, 1923, p. 4.

21. Most of the details about Romei and Scarpa are extracted from correspondence among the Colonial Office records, the more important of which are reprinted in Dakin, British Intelligence. Scarpa was met in Crete before the invasion by R. R. Madden (Travels in Turkey, London, 1829, i, p. 172), and his name appears among the defenders of the Acropolis in 1827.

22. Dakin, British Intelligence, pp. 50 ff.

23. Gordon, ii, p. 199.

24. Ibid.

25. Collegno’s diary in Ottolenghi, pp. 242 ff. Collegno gives the Pole’s name as Schutz. The same incident seems to be referred to by the author of Sketches of Modern Greece, ii, pp. 39 ff., who says the Pole—a former Philhellene with a long white beard, whom he calls Statoski—told Collegno ‘For forty years I have bared my arm for liberty and never gained a para’.

26. Villeneuve, pp. 120 f.

27. Pecchio, Picture of Greece, ii, p. 274.

28. Gordon, ii, p. 257.

29. Calosso appears in the Thouret-Fornezy list of Philhellenes as having taken part in the Battle of Chaidari in 1826. For his later career see MacFarlane, ii, pp. 175 ff. and Slade, i, pp. 132 ff. The destruction of the Janissaries is described by Walsh.

26. French Idealism and French Cynicism

The development of French policy towards Greece is discussed in Dakin, British and American Philhellenes and Dakin, British Intelligence. The general context is described in Harold Temperley, The Foreign Policy of Canning, London, 1925. On aspects of French philhellenism see Isambert, Asse, Dimopoulos, and the Documents of the Paris Greek Committee.

1. Dakin, British Intelligence, pp. 104 ff.

2. Ibid., p. 29.

3. For this society see Jean Dimakis, ‘La Societé de la Morale Chrétienne de Paris et son action en faveur des Grecs’, Balkan Studies, volume 7, 1966.

4. Quoted, ibid.

5. The growth in the activities of the Paris Greek Committee can be easily followed in their bulletin, Documents relatifs à l’état present de la Grèce.

6. See Asse and Edmond Estève, Byron et le Romantisme Français, Paris, 1907.

7. Quoted, ibid., p. 120.

8. The books of verse which were published in France during the Greek War of Independence on philhellenic themes provide an interesting indication of the state of public opinion. Most of the titles were collected by Asse, but others are known from other references. The following table gives an indication of the numbers. Only books published separately in their own right are included—innumerable other philhellenic poems were published as part of larger collections and in reviews and newspapers. The numbers by themselves give a guide to the ups and downs of public interest which rose to a peak in 1826. The fascination with Lord Byron and with Missolonghi can also be seen from the frequency with which they are mentioned in the titles.

Number of books |

Number which mention Byron in the title |

Number which mention Missolonghi in the title | |

1821 (after the outbreak of the Revolution) |

10 |

— |

— |

1822 |

18 |

1 |

— |

1823 |

5 |

— |

— |

1824 |

30 |

14 |

— |

1825 |

20 |

3 |

1 |

1826 |

40 |

2 |

13 |

1827 (until Navarino) |

16 |

1 |

3 |

—-- |

— |

— | |

TOTAL |

139 |

21 |

17 |

9. Translated from J. J. Hosemann, Les Etrangers en Grèce, Paris, 1826.

10. Feburier.

11. By Beauchène, quoted by Asse, p. 99.

12. Note sur la Grèce, Paris, 1825.

13. The best source is the Documents from which many later accounts are derived.

14. Stanhope, p. 483.

15. For the history of the French Military Mission in Egypt, taken mainly from the French archives, see Georges Douin, Une Mission Militaire auprès de Mohamed Aly, Cairo, 1923.

16. Ibid., p. 137.

17. Again the main official papers about the provision of the warships have been published by Georges Douin, Les Premières Frégates de Mohamed Aly, Cairo, 1926.

27. Regulars Again

The main sources are Débidour; Documents; and Dakin, British Intelligence.

1. Larrabee gives most of the story of Washington from original sources such as Howe, Journal, and Swan. A copy of a fragment of Washington’s own diary is in the Gennadios Library, Athens, the original MS. being now in private hands.

2. Translated from version in Swan, ii, p. 156.

3. Dakin, British Intelligence, p. 77.

4. Letter from Arnaud, 19 October 1825, Colonial Office Records, CO. 136/33, volume 2, f. 544.

5. Davesiès de Pontes, pp. 23 ff.

6. Marcet and Romilly. See Manet.

7. Gordon, ii, p. 299. Characteristically, Gordon does not mention himself by name.

8. Letter from Arnaud, 19 October 1825, Colonial Office Records CO. 136/33, volume 2, f. 544.

9. Correspondence among the Gordon Papers relates to Gordon’s successful attempt to have Justin’s narrative suppressed. It is likely that Gordon himself made use of it for his story. See Gordon, i, p. 504, where he refers to the ‘Ms memoirs of a Philhellene then serving in Crete’.

10. Schack, p. 9.

11. Harring, quoted in Barth and Kehrig-Korn, p. 88. Byern describes his second visit in his own book.

12. Jourdain, ii, p. 212; Villeneuve, pp. 115 ff.

13. Young Garel was said (Millingen, p. 291) to have distinguished himself as flag-bearer at Navarino in 1825. His father was killed at Athens in 1827.

14. Voutier, Mémoires.

15. Raybaud, ii, p. 275 and elsewhere. Persat also remarked on Voutier’s romancing but his book was not published until much later.

16. Millingen, p. 63.

17. Gordon to Robertson, 18 December 1826. Gordon Papers.

18. Chardon de la Barre.

19. General Dubourg. Schack, p. 79.

20. Documents, June 1826, p. 61.

21. Heideck, p. 35.

22. Legracieux, who had worked on the Courrier Français. Killed near Athens 1827.

23. Schack.

24. C. D. Raffenel, killed Athens 1827. Some accounts give the Philhellene different Christian names but the identity seems to be established.

25. Perhaps Rigal. Byern, pp. 236 ff. Etienne was killed near Athens in 1827.

26. Palma, p. 291. According to Millingen, p. 54, British seamen deserted in 1823 and 1824 to join Lord Byron’s brigade.

27. Lassberg known as Wolf and Schaffer known as Reinhold, both killed at Athens 1827. Barth and Kehrig-Korn, pp. 216 ff.

28. Von Vangerow. See Gosse, Lettres, p. 25.

29. Barth and Kehrig-Korn, pp. 233 ff.

30. Wohlgemuth. See Byern, p. 250. Another Wohlgemuth came in 1822.

31. Letter of Fabvier, 10 May 1826. Roma, ii, pp. 189 ff.

32. Pecchio, Picture of Greece, ii, p. 76.

33. Slade, i, p. 135; MacFarlane, i, p. 517.

34. September 1826 in Aegina. Howe performed the autopsy.

35. Morandi, pp, 74, 77.

36. Miller, p. 143.

37. Names unknown. Hahn, quoted in Barth and Kehrig-Korn, p. 24.

38. Roma, ii, pp. 189 ff.

28. A New Fleet

The fullest account of the events surrounding the ordering of the steamships and the frigates and of their performance is Dakin, British and American Philhellenes.

1. A sketch of Hastings’ life was published by Finlay in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 1845. Hastings’ papers came into Finlay’s possession after his death and are now in the library of the British School at Athens.

2. Reproduced as an appendix to Finlay, Greek Revolution.

3. The development of philhellenism in the United States is described in Booras, Cline, Earle, and Larrabee from whom most of the following section is drawn.

4. Howe’s estimate. Historical Sketch, p. 446.

5. For American dealings with the Turks and the career of George English, see Finnie.

6. The affair of the frigates is described by Dakin, Earle, and Lepandis. Many of the details are derived from the controversial pamphlets of the time, William Bayard, An Exposition of the Conduct of the Two Houses. .., N.Y., 1826; Alexander Contostavlos, A Narrative of the Material Facts…, N.Y., 1826; John Duer and Robert Sedgewick, An Examination . ., N.Y., 1826; A Vindication of the Conduct and Character of Henry D. Sedgewick, N.Y., 1826; H. D. Sedgewick, Refutation of the Reasons assigned by the Arbitrators, N.Y., 1826; and especially Report of the Evidence and Reasons of the Award between Johannis Orlandos and Andreas Luriottis, Greek Deputies, of the one part, and Fe Roy, Bayard and Co. and G.G. and S. Howland, of the other part. By the arbitrators, N.Y., 1826.

7. For the life of Lord Cochrane see his own, The Autobiography of a Seaman, London, 1860; E. G. Twitchett, Life of a Seaman, London, 1931; Christopher Lloyd, Lord Cochrane, London, 1947; and Warren Tute, Cochrane, London, 1965. For Lord Cochrane’s activities in Greece see especially the work by his nephew, George Cochrane, Wanderings in Greece.

8. Slade, i, p. 182.

9. MacFarlane, i, p. 197.

10. Dakin, British Intelligence, p. 45.

29. Athens and Navarino

For the diplomatic developments which led to the Battle of Navarino see Crawley, and Harold Temperley, The Foreign Policy of Canning, London, 1925. For the operations near Athens see Dakin, British and American Philhellenes, and Debidour, as well as the general histories. Some new details are in the journal of Thomas Whitcombe, published since the first edition of the present work.

1. Quoted Temperley, op. cit., p. 346.

2. Quoted Crawley, p. 55.

3. For the career of Sir Richard Church see Dakin, British and American Philhellenes, Lane-Poole, and the curious work by E. M. Church. Church’s papers are in the British Library.

4. For Heideck’s expedition see Heideck. For the false rumours see the letter from Heideck to Eynard, 4 November 1826, Colonial Office Records, CO. 136/42, f. 16.

5. Gibassier, Gasque, and Bohn. The French naval commander in the area made a plea for them to be spared.

6. Described in Dakin, British and American Philhellenes.

7. Letter of Hastings, 11 September 1826, Hastings Papers. ‘Mr Thompson alias Critchley died of bilious fever 8 September’.

8. Described in Dakin, British and American Philhellenes.

9. Howe, Letters and Journals, p. 235.

10. For these incidents see Miller, p. 163; Woodruff, p. 87; Post, p. 195. Hesketh had visited Greece in 1823 and 1824 and worked with Byron. See also Finlay, Hastings, p. 508.

11. I include the following:

Vitsche |

Hungarian | |

Berlin |

Woirion |

Georg |

Bourbaki |

Marc | |

Clement |

German |

Lasso |

Darmagnac |

Becker |

|

Dujurdhui |

Bohn |

Spanish |

Florence |

Bruckbacher |

Lanzana |

Garel |

Lassberg |

Riviero |

Gasque |

Schaffer |

|

Gibassier |

Schweicard |

Italian |

Inglesi |

Seiffart |

Pecorara |

Ledoux |

Zimmermann |

Ritatori |

Lefaivre |

||

Legracieux |

Corsican |

Swiss |

Parat |

Balzanni |

Doudier |

Raffenel |

Galdo |

Rival |

Rigal |

Gambini |

|

Robert |

Marseilleisi |

Belgian |

Passano |

Oscar |

12. Frankland, i, p. 312.

30. America to the Rescue

1. Much information about the Swiss relief activities is in the Documents of the Paris Greek Committee. See also Rothpletz, Eynard, and Penn, Philhellenism in Europe.

2. Finlay, Greek Revolution, ii, p. 128. Korring was said to be 6 feet 7 inches tall. He took part in the campaign in Western Greece in 1828 but his palikars mutinied against his attempts to impose discipline and shut him in an oven. He died of disease at Patras in 1829.

3. Finlay, Greek Revolution, ii, p. 158.

4. See Jarvis; Dakin, British and American Philhellenes; and Larrabee.

5. Dakin, British and American Philhellenes; Earrabee.

6. Howe, Letters and Journals; Dakin, British and American Philhellenes; Larrabee.

7. See Earle, Booras, and Cline.

8. Dalleggio, p. 221.

9. For American policy towards Turkey after Navarino see Finnie.

10. The descriptions and quotations about the American relief work in Greece are taken from Woodruff, Post, Miller, and especially Howe, Letters and Journals. Larrabee is a useful secondary source.

31. Later

1. J. Phil. Fallmerayer, Geschichte der Halbinsel Morea, Stuttgart and Tübingen, 1830.

2. For the development of the Modern Greek language and the politics surrounding it, see Robert Browning, Medieval and Modern Greek, London, 1969.

3. Rev. Richard Burgess, Greece and the Levant, i, p. 257.

4. This can still be seen.

5. See Ernest Breton, Athènes, Paris, 1862, p. 139. The name of Ducrocq can still be made out but not the rest of the inscription quoted by Breton. Ducrocq was killed in a naval action in December 1827. On the same column of the Parthenon it is also still possible to read the carved name of the French Philhellene Daubigny who was also in the Acropolis during the siege.

6. Letter of Church to Finlay, 20 November 1861, Finlay Papers.