29 Athens and Navarino

The Princess Lieven, wife of the Russian Ambassador to the Court of St. James charmed many of the great men of the age. This was partly due to her personal talents and partly because she had more influence over Russian foreign policy than her husband the Ambassador. The princess’s diplomatic qualifications were formidable. She had been the mistress of Metternich the Austrian Chancellor and was now one of the small set that shared the social life and the state secrets of George IV; she was a friend of Castlereagh and of Canning; and ‘more than a friend’ to Lord Grey.

In the summer of 1825 Princess Lieven paid a visit to Russia. On the night she was due to return to England she was hastily summoned to see Czar Alexander who was now living the life of a religious hermit away from St. Petersburg. The Princess was asked to see that a message about Greece, too delicate to be entrusted to any of the usual channels, was passed to Canning. The Czar said:

My people demand war; my armies are full of ardour to make it, perhaps I could not long resist them. My Allies have abandoned me. Compare my conduct to theirs. Everybody has intrigued in Greece. I alone have remained pure. I have pushed scruples so far as not to have a single wretched agent in Greece, not an intelligence agent even, and I have to be content with the scraps that fall from the table of my Allies. Let England think of that. If they grasp hands with us, we are sure of controlling events and of establishing in the East an order of things conformable to the interest of Europe and to the laws of religion and humanity.1

Alexander insisted that Russia would never make advances to England, but the British Government should understand that, if they made the first move, it would not be repulsed.

Princess Lieven duly passed the hint to Canning and he immediately realized that the long international deadlock was broken. Formal discussions were begun with the Russians about the settlement of the Greek question and were soon making progress. The death of the old Czar did not interrupt the work; in early 1826 the Duke of Wellington set sail for Russia to agree the final points; and on 4 April 1826 an Anglo-Russian protocol on the affairs of Greece was signed at St. Petersburg.

It consisted of only six short articles, but it was the most important move towards a settlement that had occurred during the five years of the Greek war. The two powers had at last recognized that they were well placed to take the initiative; Britain because of the repeated requests of the Greeks to take their country under her protection, Russia because she had an army on the Turkish frontier. They agreed that they would act together to seek a settlement by offering ‘mediation’ between the Greeks and Turks.

The foundation of the agreement was clause five, which declared that neither His Imperial Majesty nor His Britannic Majesty would look for ‘any increase in territory, any exclusive influence, or any commercial advantage for their subjects not open to those of other nations’. This article, provided always that His Imperial Majesty could be trusted, removed the danger that the Russians would invade Turkey and compel the Sultan to cede the Danubian Provinces and Greece or to make some arrangement which would be tantamount to the same thing. The protocol ended with an invitation to the other great powers to join in the arrangement. News now began to arrive that the Russian army on the Danube was being reinforced. Canning responded by strengthening the British naval squadron in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The protocol represented a considerable realignment in the politics of Europe. Russia had for the first time broken away from her alliance with the other absolutist powers, Austria and Prussia, and Metternich was furious. France, too, quickly recognized the fundamental change that had occurred. It was now obvious that, in the face of an Anglo-Russian alliance in the Levant, France could do little on her own. When therefore during the summer of 1826 the suggestion was made that France also might like to join the protocol in accordance with the sixth article, the overture was received sympathetically in Paris. Austria and Prussia remained obstinately aloof, but during the next year a long round of diplomatic negotiations converted the principles of the protocol into the Treaty of London signed by Britain, Russia, and France. The three great powers on whom the Greeks most depended were now united.

It is one thing to offer mediation, quite another to persuade the warring parties to accept it. The Greeks, who were still regarded internationally as rebels, seemed ready to settle on the basis of continuing to acknowledge Ottoman suzerainty provided all Turkish troops were removed from Greece and in any case they were in no position to argue; but for the Turks, the very existence of the protocol was anathema. When a government is putting down a rebellious province it has no need of ‘mediation’ from foreigners. Would the British Government accept Turkish ‘mediation’ in dealing with the Irish? Some excuse was necessary if the great powers were to intervene in matters which they had hitherto acknowledged as the exclusive concern of the Ottoman Government.

It was decided to hang the approach to the Turks on the stories that were circulating about Ibrahim’s declared intention to exterminate the inhabitants of the Morea and to repopulate the area with Egyptians. If the stories were true, Ibrahim’s methods seemed to be sufficiently different from the recognized usage of civilized powers as to make pressure from foreigners seem less improper. The ‘barbarization’ of Greece, as the alleged policy was called, could be said to be of general international interest even if the powers claimed no right to speak on behalf of the unfortunate Greeks who were to be barbarized. Canning was delighted with this suggested lead-in, since it was different from the type of approach which had been urged on the Government since the beginning of the war. There was to be no mention of the clichés of philhellenism, no claim to intervene on behalf of the Christians in the Ottoman Empire. As Canning himself wrote, he liked it the better ‘because it has nothing to do with Epaminondas nor (with reverence be it spoken) with St. Paul’.2 The powers were more likely to impress the Turks if they spoke with the familiar voice of self-interest than if they claimed some special virtue or consideration for the Greeks which Turks especially were unlikely to find convincing.

The three powers had a variety of means by which to put pressure on the Turks to accept ‘mediation’, but it soon became clear that they were not going to yield. Both the Ottoman Government in Constantinople and Mehemet Ali in Cairo denied categorically the stories about the intended ‘barbarization’ of the Morea, although making plain that they intended to settle the Greek Revolution in the traditional Ottoman way. The powers were therefore driven along a course of action which was vaguely implicit in the protocol and gradually became explicit. If the warring parties refused ‘mediation’, then they would have to be compelled to accept it. A hint of the possibility of violence began to appear and this bound the allies more closely together. If they did not act together, then Russia might decide to act alone, and this was something the two others could not accept. Russia insisted that, if the Turks did not accept mediation within a reasonable time, then the powers should instruct their naval forces in the Mediterranean to interpose themselves physically between the combatants and prevent any new reinforcements, Turkish or Egyptian, from being sent to Greece. These thoughts were gradually brought together and were finally made explicit in the Treaty of London of July 1827. A secret article, which was soon made public, committed the three powers, if necessary, to compulsion.

Meanwhile the situation of the Greeks continued to deteriorate. After the fall of Missolonghi in April 1826, most of Roumeli, the area north of the gulf of Corinth, reverted to allegiance to the Turks, and a Turkish army advanced into Attica. The area held by the Greeks gradually contracted as they were pressed from the north by the Turks and from the south by the Egyptians. Then in August 1826 the town of Athens was retaken by the Turks although the Acropolis still held out. The Acropolis of Athens was now the last fortress in Greek hands in the way of a final Turkish advance towards the isthmus. To the leaders of the Greek Government it seemed vital that it should be held.

The eyes of the world at this moment of supreme crisis were therefore fastened on the most famous spot in all Greece. The Acropolis of Athens which contained the most impressive visible remains of the classical age* was now an island in a barbarian sea. The Greeks seemed to be defending not so much a fortress as a talisman of civilization itself, the hope of regeneration, and the symbol of the identity of the Ancient and Modern Greeks. The situation in 1826 had an uncanny superficial resemblance to the other supreme crisis of the Greeks in 480 B.C. when the Persians had sacked the city. The oriental barbarians were again in Athens. As in 480, the citizens took refuge on the island of Salamis. As in 480, their hopes lay mainly in their wooden walls.

The Greek Government decided to use the last forces at its command in an attempt to relieve the beseiged Acropolis, and the military history of Greece from the autumn of 1826 to the spring of 1827 is mainly concerned with operations designed to achieve this purpose.† In late August 1826 Colonel Fabvier felt that he must again entrust his regulars to battle even although he was still dissatisfied with their state of training. It was decided that he should attempt to fight his way to Athens from Eleusis in company with a large body of irregular palikars. This route was chosen in preference to the more direct road from the Piraeus because the rocky terrain afforded more protection against the Turkish cavalry.

The result was the same as in every operation during the five years of the war in which the Greeks had attempted to combine the two methods of fighting. As soon as the enemy appeared, the irregulars hurriedly took cover leaving the regulars in the lurch to defend themselves as best they could. Only Fabvier’s skill and the sound training which he had insisted on prevented a repetition of Peta. He extricated his little force to safety with the loss of a few Philhellenes and vowed he would never again fight in company with the irregulars. In October however, when Ghouras was killed by a stray bullet and it looked as if the Acropolis was about to surrender, Fabvier was prevailed upon to attempt another operation to cut off the Turkish supply route north of Athens, but again it proved impossible to co-ordinate the two types of forces. The irregulars, whose task was to hold the passes in Fabvier’s rear, failed to appear at the proper time and again the regulars and Philhellenes had to retreat hastily to avoid being surrounded.

Fabvier had now taken the field with his regulars four times, first at Tripolitsa shortly after he assumed command in July 1825, then at Euboea in February 1826, and now twice in Attica in the autumn. At Euboea his lack of success was due to the inexperience of his men, but he felt that on the three other occasions he had been let down by the irregulars. Perhaps, he began to wonder to himself, he had been deliberately let down just as in 1821 and 1822 the captains had deliberately discredited and destroyed the Regiment. Fabvier was well aware that it was only his own experience and coolness in crisis that had prevented his little army from being totally destroyed. He had achieved nothing, received no thanks, but had seen some of his old revolutionary comrades uselessly killed.

As the autumn of 1826 gave way to winter, Fabvier shut himself off in the fortress at Methana, his disgust and suspicion of the Greeks growing steadily stronger. He seemed more than ever determined not to endanger his little army again by trusting to the captains. Then in the middle of December the Greek Government sent a special envoy to Methana to beg his help for a very difficult task. A party of Greek troops had succeeded in entering the Acropolis at Athens to reinforce the garrison but, as a result, the fortress was running short of ammunition. Would Fabvier be willing, the Government begged, to try to run ammunition into Athens? Fabvier was touched and relented from his previous resolutions. He agreed to make the attempt, stipulating only that he should not be required to stay in the Acropolis.

On 12 December 1826 when the moon was up he landed at Phaleron with 530 regulars and 40 selected Philhellenes in the lead. Each man carried a sack of gunpowder. The intention was to throw the sacks to the Greek outposts and then retreat, but at the crucial moment the alarm was given and Fabvier and his men were obliged to charge with the bayonet and seek the safety of the Acropolis. They were now caught in a besieged fortress with no prospect of escape unless relief came from outside. Fabvier felt that he had again been betrayed; that he had been deliberately enticed into the Acropolis to remove him from the scene and to strengthen the garrison; and that the garrison deliberately roused the Turkish sentries outside if he gave signs of preparing to leave. The siege of the Acropolis of Athens became, more than ever, the focus of attention. If it were to fall not only would the way be open to the isthmus but Greece would have lost her best trained regular troops.

At this depressing moment Fabvier was subjected to a new mortification. The story was gradually substantiated that the Greeks intended to appoint an Englishman* to the chief command over his head. The prospect of Lord Cochrane’s arrival Fabvier could accept. Cochrane was a violent devil-may-care liberal of the type that Fabvier could almost admire despite his nationality, and in any case he was bound to confine himself to the sea on which the British were the acknowledged experts. But to appoint an Englishman to command the land forces was an insult which Fabvier would find it hard to forgive.

Sir Richard Church† had seen almost as much fighting as Fabvier.3 As a young officer he had taken part in the invasion of Egypt in 1800, and from then until the peace of 1815 he was in numerous campaigns, often under fire and several times wounded. It was during this period that he first made the acquaintance of the Greeks. He took part in the capture of Zante, Ithaca, and Cephalonia in 1809 and was seriously wounded in leading the assault on Santa Maura in March 1810. While he was stationed in the Ionian Islands he raised a regiment of Greeks, the Duke of York’s Light Infantry, and led them with outstanding success. When he left the Ionian Islands on leave in the summer of 1812 he was presented with several letters of gratitude by his men, praising him in terms usually reserved for the safety of obituary notices. He won the affection of men from all parts of Greece which neither he nor they could ever forget. In particular, the first of forty signatures in one of the letters of eulogy was that of Theodore Colocotrones who had experienced his first taste of Western ways in the Duke of York’s Greek Light Infantry.

Church’s success in the Ionian Islands was recognized in London and he returned with a mandate to raise a second Greek regiment and with plans to employ them on the Continent in the great allied offensive against Napoleon. In 1814, however, the Turks protested successfully to the British Government that it was a breach of their sovereignty to recruit troops in Greece and the regiments were disbanded.

Church was by now more Greek than the Greeks and looked forward to the day when the revolution against the Turks would come. He became spokesman for the Greek cause in London and was asked to brief the British delegation at the European Congress of 1814 on the situation in the Ionian Islands. His efforts no doubt played a part in the decision, when peace finally came in 1815, to retain the islands under British protection.

In 1817, with the approval of the British military authorities. Church entered the service of the restored Bourbon King of the Two Sicilies in the rank of major-general, and for the next three years he applied himself vigorously and successfully to the suppression of brigandage in Southern Italy. Endowed with power of summary execution which he did not hesitate to use, Church restored the authority of the government over the provinces of Apulia. ‘A few months were sufficient’, he himself reported, ‘to totally destroy the assassins and brigands, and to break up the different revolutionary societies, to receive the submission of their chiefs and the surrender of their arms’.

After this success Church was appointed in 1820 to the command of the army in Sicily and he soon began to understand why that island had remained obstinately ungovernable since the fall of the Roman Empire. Before his programme of pacification had really started, however, the constitutionalist revolution broke out. Church attempted to maintain the royalist cause but he was attacked by a mob, arrested, and imprisoned. After six months his release was secured and he returned to England, but he was soon back in Naples after the rebellion had been put down.

When the news of the outbreak of the Greek Revolution arrived in 1821, Church ‘sighed to be with them’ and immediately chartered a small vessel and set off. He got as far as Livorno before he was persuaded that it would be unwise to go without money or adequate preparation. He nevertheless felt guilty that the old commander of the Duke of York’s Greek Light Infantry was not fighting in Greece. Because he had known something of the Greeks’ plans for revolution before it started, Church never doubted that he should be their leader, and wrote:

One great and sublime idea occupies me and renders me insensible to everything else…. Conceive the great glory of my being instrumental toward the Emancipation of Greece…. The banner that I gave them floats in front of the Grecian armies, but the recreant general is absent, lost in the pleasures and extravagances of the Neapolitan capital.

The Greek deputies in London approached him several times with offers of command in Greece, but although his commitment to their cause was total, for years no agreement could be reached. In part this was probably due to worries about money. It is no light matter for a family man to give up regular pay and the prospect of a pension to fight in a cause officially disapproved of by his own government. The first negotiation seems to have fallen through because the deputies could not pay Church enough. On a later occasion, however, when money from the loan was plentiful, the deputies seem to have offered him too much. No doubt they had in mind their recent experience of the appetites of Napier and Cochrane, but Sir Richard Church was a different cast of Philhellene. The implication in their invitation that he would be principally interested in his salary, offended him deeply. He protested vehemently that he was eager to go, that he was ready ‘to sacrifice everything to the cause’, and that they had only to invite him and he would rush to their side.

26. ‘Regeneration of the Greek Parnassus’.

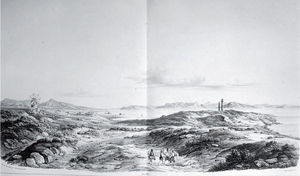

27. A French view of the Battle of Athens, 1827.

28. Athens as it actually looked at about this time.

29. The Port and Temple at Aegina.

Why then, the reader of his correspondence is often tempted to ask, if Church felt so passionately about going to Greece, did he not go instead of wasting time in fruitless recriminations. It is a poor lover who is prepared to spend five years in the preliminaries. The explanation lay in Church’s attitude to the war. He felt that he had a very special place among the Greeks which they ought to recognize. He wanted desperately to go, but he would only go if he was asked properly, formally, by the Government of Greece and by the other leaders. Nothing less than an official invitation would do, but he was quite ready to spend time engineering one. At last early in 1827 he received a flattering letter of invitation from the Government in Nauplia dated 30 August 1826, which had been carefully contrived by the ever-resourceful Edward Blaquiere. Colocotrones added his own message in a letter in September:

My soul has never been absent from you—We your old comrades in arms… are fighting for our country—Greece so dear to you!—that we may obtain our rights as men and as a people and our liberty—How has your soul been able to remain from us? … Come! Come! and take up arms for Greece, or assist her with your talents, your virtues, and your abilities that you may claim her eternal gratitude!

Thus reassured that he would be welcomed and properly treated in Greece, Church decided to go, but even so proceeded slowly, choosing to appear in Greece in the capacity of a private traveller before committing himself further.

It is easy to see why the prospect of his arrival should have annoyed Fabvier. If anything is more exasperating than to be constantly reminded of a famous predecessor, it is to be constantly assured that he is coming back. And then Church was an Englishman most of whose life had been spent in fighting the great Napoleon, and who had personally taken part in the last harsh campaign in 1815 in the South of France when the few surviving pockets of Bonapartist resistance had been mercilessly crushed.

Most unattractive of all was Church’s service to King Ferdinand of Naples, whose pay he drew right up until January 1827 when he set sail for Greece. How could a man who served one of the most hated and most despotic regimes of Europe claim to be a fighter for liberty? One man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter, one man’s brigand is another man’s patriot, as his old friend Colocotrones might have explained to him. The Bourbon Government in Naples, like most dictatorships, found it expedient to pretend that its political opponents were criminals, to lump together carbonari and liberals with bandits and vendettists, and Church was quite content to carry out the Government’s orders according to the simple notions of military justice, priding himself on never putting a man to death without a court martial. It never seems to have occurred to him that there might be a contradiction between suppressing liberty in the Two Sicilies and fighting for it in Greece. His commitment was entirely and exclusively to Greece and in this sense he can be regarded as one of the few true Philhellenes. He fought for Greeks as Greeks and Modern Greeks at that, not for liberty or for religion or for the sake of Homer, Plato, et al. But how could Fabvier and his little army of failed revolutionaries, French and Italian, regard such a man? His life had been devoted to destroying everything they held dear. Colonel Pisa, the leader of the Italian exiles and commander of the Company of Philhellenes, had personally fought against Church’s forces in Sicily in 1820.

At the beginning of December a rumour suddenly swept Greece that new help was at hand: thirty thousand troops, it was said, were on their way from Bavaria. In fact there was a grain of truth in the story, but only a grain. The number of Bavarians who had come to join the fight for Greek independence was twelve.

Colonel Karl Hleideck,4 often called Heidegger, was a new type of Philhellene. He was an officer of the Bavarian army and the party of officers, sergeants, and military doctors whom he led were directly under his command. They wore Bavarian uniform and they had been officially and openly sent by King Ludwig, as a direct philhellenic gesture. It was a gesture which could be made by only a small power with few interests at risk in Turkey. The great powers, however much they interfered in one another’s affairs, always carefully respected the proprieties. They took care never to support their Philhellenes to the extent of endangering their position in Turkey and their support was always, if necessary, disavowable. Ludwig’s grand gesture was to produce a handsome dividend later when, in the absence of anyone more suitable, the powers chose Ludwig’s son Otho to be the first King of Greece.

Heideck’s description of his first encounter with the Greeks in December 1826 could, with a few changes, be an account of one of the early German Philhellenes. In four years the essentials had not changed. Heideck was shocked when on being introduced to the members of the Government he found them crouching on the floor in oriental style and he noticed with horror a huge louse on the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. Nevertheless he proceeded to present his letter of introduction and to outline his plans. He had come because of Bavaria’s sympathy to the Greek cause; he had money and arms; he and his men would raise a force of Greeks and teach them tactics; he already had a system in mind and was eager to begin; he had no self-interest to promote and would happily serve under the Greek commanders; he would not even (a new point) write articles for newspapers.

To Heideck’s surprise, the Government in a short speech of appreciation, seemed unenthusiastic and gave no word that they accepted his offer. He was affronted when Dr. Bailly, an agent of the French Philhellenes, tried to warn him against the Greeks and told him to take his time and look around. Such words from a Philhellene! Bailly, Heideck concluded, must have a personal grudge against Fabvier. Soon afterwards Heideck was taken aside and it was explained why the Greeks had turned down his offer. If he was allowed to raise a force of Greeks, he was told, many men would join, they would accept uniforms and arms but, as soon as they were ordered out to fight, they would desert and join the palikars. Heideck, the Greeks explained, would be angry, he would lose all his money and his equipment, he would have to report his disappointments and failures to the King of Bavaria, and the Greek cause would suffer as a result. Heideck, much perplexed, decided to accept the advice to wait and look around.

In December, too, the frigate Hellas eventually arrived from the United States bringing, among other things, the armament for the Perseverance which had arrived three months earlier. At last Greece had two powerful vessels which might be put to use immediately. Hastings was asked to remain in command of the Perseverance, which was known henceforth by her Greek name of Karteria. The Hellas was put under the control of a commission of admirals from the islands.

The obvious strategy was to exploit the sea power which the two ships provided to make another attempt to relieve the siege of the Acropolis. Communication with Fabvier was maintained by carrier pigeon and it was learnt that water was short. The fortress could not hold out much longer. An elaborate plan was therefore drawn up to make use of all of Greece’s forces in a desperate attempt to raise the siege. The Hellas was to blockade the north coast of Attica, the Karteria was to give artillery support off Piraeus, and two bodies of troops were to land on the south of Athens and advance on the city.

The command of the operation was entrusted to Colonel Gordon who agreed to provide some of the money. Since his return to Greece in the spring, Gordon had insisted that he was not a Philhellene but a travelling gentleman who happened to be interested in Greek affairs. He cruised around in his yacht flying the British flag spending on any worthwhile cause he could find the remnants from the loan money with which he had been entrusted by the Greek deputies in London. He was thoroughly disgusted with the senseless quarrelling and armed clashes among the Greeks and vowed that he would not rejoin their service until Lord Cochrane arrived. In February 1827, however, when the various Greek leaders pressed him to take command of the operation to relieve the Acropolis, he could not refuse and agreed to provide money from his own fortune. Heideck consented to serve under his orders.

It was a bold scheme. One force was to land at Eleusis and attempt to do what Fabvier had failed to do in the autumn—advance on Athens over the rocky terrain to the north. At the same time another force under Gordon’s direct command would secretly land at Phaleron, which is almost the nearest point on the coast to Athens, and surprise the besieging Turks.

The command of the Eleusis force which included a detachment of regulars was entrusted to a recently arrived French Colonel called Bourbaki. He came originally from Cephalonia, but had spent his life in the French army and was a convinced Bonapartist under suspicion by the secret police. To the amusement of more experienced Philhellenes, Bourbaki, who was now fat and unathletic, put on a splendid Albanian costume covered with gold braid, with pistols in his girdle and a jewelled sword.

At first the operation seemed to proceed according to plan. Bourbaki and his men landed at Eleusis and prepared to march towards Athens. Then at midnight two days later Gordon and his troops were put down by the Karteria at Phaleron only a mile or two from their objective. But this operation, like so many others, foundered on the deep-seated differences between the Europeans and the Greeks. Despite orders to preserve silence and secrecy, as soon as the palikars were safely ashore at Phaleron, they started to fire off their muskets out of high spirits to relieve their tension and to announce their arrival to their friends in the Acropolis. The Turks were of course immediately aroused and were able to attack Gordon’s forces before they could move from their bridgehead. Disaster seemed certain and Gordon, rightly, wanted to re-embark since an advance on Athens was now out of the question. The Greeks in several days of severe fighting maintained the bridgehead and regarded the affair as a great victory although nothing of any strategic value had been achieved. The Karteria proved herself in bombarding the Turkish positions but her engines failed at a critical moment and only Hastings’ skill and seamanship prevented her from being destroyed.

Meanwhile, Bourbaki and his force also repeated the same mistakes and misunderstandings which had occurred whenever Europeans and Greeks had fought together throughout the war. They were caught on the plain by the Turkish cavalry and the irregulars immediately fled. Bourbaki and his regulars were left exposed and were cut to pieces. Over 500 men were lost, one of the biggest disasters in battle (as distinct from massacre) of the war. Bourbaki himself was killed, his jewelled weapons and golden dress making him the favourite target. Two other Frenchmen and a German doctor5 were captured alive but their heads were soon added to the general trophy.

At the end of February Gordon gave up his command in disgust. He did, however, recommend to the Greek Government that Heideck should be given a chance to attempt to cut off the Turkish supply line to the north by landing a force on the north coast of Attica and attacking the fort at Oropos. But Heideck had no more success than Fabvier or Gordon. A force of about 500 men was transported to Oropos mainly in the Karteria and the Hellas, but when they landed and attacked the fort it proved too strong for them and they had to retire with losses.

Meanwhile, Greece was slipping into anarchy. At Nauplia, the nominal capital, one captain was in possession of the fortress and another of the town. Sporadically their armed bands would clash and sometimes the guns of the fortress would be turned on the town. It was a shot from the fortress during one of these encounters that killed young Washington in July 1827. The Government had to move out, first to the fort in the bay and then to the islands, but as the area of Greece declined, the number of her Governments increased. Colocotrones established his own supporters at Castri and claimed that they formed the legitimate National Assembly. The islanders had also split up, one party led by the former president Conduriottis, was established at Hydra and was planning to attack by force his opponents who were established on the neighbouring island of Poros. Naval operations against the Turks had virtually ceased. Each of the leaders of the Greek Revolution struggled to ensure that, if by some good fortune Greece survived, he would be near the head of affairs.

On 23 February 1827 Colocotrones’ assembly opened its session at Castri. Shortly afterwards the followers of the old Government convened their rival assembly at Aegina. The two quarrelling island parties were physically restrained from fighting by the British naval squadron and gradually they attached themselves to one or other rival governments. Meanwhile, the signs of famine became increasingly obvious.

The Greeks had never lacked for advice that they should settle their differences and pull together for the benefit of the nation as a whole. Edward Blaquiere, who had attempted the role in 1823 and again in 1824, now reappeared in Greece for the third time and thrust himself confidently into the political argument. Blaquiere’s main task was to ensure that the way was well prepared for the imminent arrival of Lord Cochrane and of Sir Richard Church, but he had prudently ascertained the views of the British Government before he left England.

Blaquiere bustled ceaselessly between the rival Greek Governments trying to persuade them to sink their differences. He was unsuccessful but he did establish a fund of information about their views which was to be of value later. He also contacted the party in the Ionian Islands which, under the guise of being a charity, was working to have Capodistria invited to Greece. Blaquiere was able to establish that all the main parties and Governments would now be willing to accept Capodistria as leader of Greece in preference to any of themselves. He knew too that, contrary to earlier fears, this outcome would not be rejected by the British and French Governments since they had come to accept that Capodistria would not be simply a tool of the Russians. As far as the Greeks were concerned, Capodistria had certain huge advantages. Not only was he the only Greek political figure of any reputation or experience outside Greece, but he had never been in Greece. None of the Greek leaders knew him personally and he had no political debts. To the powers Capodistria seemed to be the only man with an European background who had a chance of holding the country together.

On 17 March 1827, the long-awaited Lord Cochrane at last arrived in Greece with his pitiful little navy of the brig Sauveur and the two yachts. His reading of the fifty books on Greece during his enforced wait in France had taught him the appropriate sentiments for such occasions. After his first sight of the Acropolis he noted in his journal:

The Acropolis was beautiful. Alas! What a change! What melancholy recollections crowd on the mind. There was the seat of science, of literature, and the arts. At this instant the barbarian Turk is actually demolishing by the shells that now are flying through the air, the scanty remains of the once magnificent temples of the Acropolis.

Cochrane presented himself to the Government at Poros where he was given a huge welcome. The next day Colocotrones invited him to go instead to his rival Government at Castri. Again Cochrane knew the proper philhellenic response: he quoted to Colocotrones the famous passage from the first Philippic in which Demosthenes exhorts the Athenians to lay aside their differences and unite against Philip of Macedon. Cochrane declared emphatically to both groups that he would do nothing unless they united.

A week before Cochrane’s arrival, Sir Richard Church stepped ashore in Greece. He naturally made first for the Government of his old friend Colocotrones at Castri. ‘Our father is at last come,’ Colocotrones declared in presenting Church to his men. ‘We have only to obey him and our liberty is secured’. Church however insisted that he was a travelling gentleman and would take no part in the war while the two governments were at odds.

Since neither of the two saviours would act without the other and each government had a saviour of its own, offers of mediation were soon made. After a good deal of patient diplomacy it was agreed that the two rival assemblies should meet on neutral ground and elect a new leader. Damala, the ancient Troezen, was chosen since it was almost physically half way between Aegina and Castri. In March and April a series of conferences were held in a lemon grove near the ancient ruins. After numerous setbacks, threats of resignation and attempts at treachery, agreement was at last reached on three important points. On 10 April Lord Cochrane came ashore for the first time, took an oath of loyalty before the assembled Greek leaders, and gave his promise to fight until Greece was free. On 11 April the Greeks proclaimed Capodistria (in absentia) President of Greece for seven years. On 15 April Sir Richard Church accepted appointment as Commander of the land forces and a new Greek title corresponding roughly to ‘Generalissimo’ was invented for the occasion. Greece now had leaders, their main qualification for office being in each case their total lack of experience of Greek conditions.

A month had passed in these discussions and the Acropolis of Athens was still under siege. Cochrane and Church both tried to treat Fabvier with consideration, sending him encouraging letters and offering their co-operation, but Fabvier never responded to kindness. Despite his total dependence on the new arrivals for any hope of being relieved—and even of escaping alive—his characteristic reaction was sarcasm, implying that the Greeks were holding back out of cowardice although they outnumbered the enemy by about three to one. Fabvier also announced that the men in the Acropolis could not hold out for more than a few days longer and this was a deliberate exaggeration intended to mislead.

Cochrane decided that an immediate operation should be mounted to relieve him and various methods were considered. In the end the plan chosen was remarkably similar to the ones that Fabvier himself and then Gordon had attempted before his arrival, namely an advance simultaneously from the neighbourhood of Eleusis and from the bridgehead near Phaleron, with the Hellas and Karteria providing off-shore support.

It was to be on a larger scale and new bodies of troops were specially recruited in the islands. Everything seemed to be set for a great decisive battle and Greeks and Philhellenes arrived from all parts of Greece to play their part. At last all quarrels between the Greeks and the rivalries between the Europeans seemed to have been set aside. The Moreotes would fight alongside the hated Hydriotes, the regulars with the irregulars.

The Philhellenes were now united as never before. A commission had been set up to control the money arriving from Europe. It represented the philhellenic committees of Paris, Berlin, Dresden, Munich, Geneva, and the other Swiss Cantons. Heideck and his Bavarians co-operated unreservedly with Church. Gordon agreed to command the artillery.

New volunteers arriving from Europe usually preferred to join the land forces. Fabvier’s force inside the Acropolis was almost entirely French and Italian, but the regulars outside, although still mainly French and Italian, now also contained Germans, Swedes, Swiss, and others.

The Greek Navy on the other hand now took on a distinctly Anglo-American appearance. Cochrane had brought with him a few dozen British and American naval officers and seamen, some of whom had been with him in South America. Other Americans came in the Hellas. Captain St. George6 had assumed his patriotic name to ensure that Lieutenant Hutchings could continue to draw his half-pay from the Royal Navy and would not be prosecuted under the Foreign Enlistment Act on his return. Mr. Thompson,7 who died on the voyage out in the Karteria, was really a naval officer called Critchley. Lieutenant Kirkwood was a pseudonym for Downing.8 These English were good sailors and fearless as everyone recognized, but they seem also to have been brutal and mercenary. Other Philhellenes were aghast at the ease with which they adopted the Greek practice of killing off prisoners, outdoing the Greeks in their atrocities.9 They gained a reputation for violence and drunkenness.*

In announcing his intention to relieve the siege of the Acropolis, Lord Cochrane tried to put into effect the methods that he had used successfully in the past. Addressing the Greeks through an interpreter, he produced a huge blue and white flag with an owl in the middle which he had bought at Marseilles. A thousand dollars, he promised, would go to the man who raised the flag on the Acropolis, and ten thousand dollars would be divided among the men who would accompany him. Church, on the other hand, behaved as if he was at the head of a European regular army with headquarters and staff. He installed himself in one of the yachts offshore so as to be able to keep in touch with the different elements of his motley army and seemed determined to give most of the orders in writing. Soon the Greeks began to accuse him of being a yacht-General afraid to set his foot on the land.

Towards the end of April 1827 the preparations seemed to be complete and the forces began to land at the bridgeheads. On the 25th Cochrane himself went ashore and saw an engagement in which the Greeks overran some of the Turkish outposts near the coast and killed about sixty men. That day he wrote confidently to the Government, ‘Henceforth commences a new era in the system of Modern Greek Warfare’, but three days later he was disproved in one particular at least. About 200 Turks and Albanian Moslems had been surrounded and were induced to surrender on terms. As soon as they emerged, however, the Greeks attacked them and one hundred and twenty-nine men were massacred on the spot. Chaos ruled for hours until the leaders restored order by shooting down some of the Greeks, but an advance on Athens was now impossible for the time being. To the more experienced Philhellenes such as Gordon, who watched the massacre through his telescope, the fault lay entirely with Church and Cochrane who refused to listen to any advice from men with experience of Greek conditions. Cochrane himself was deeply shocked and threatened to give up the attempt to relieve the Acropolis, but he was persuaded to give it one more try. Already in his few weeks in Greece he had become cynical and sarcastic, implying strongly in many of his pronouncements that, with a little pluck, the Greeks could have relieved the Acropolis long ago.

The 6 May was set for the next attempt and the operation was planned as almost a repeat performance of Gordon’s disastrous expedition in February. The Greek forces, mainly irregulars but with a small contingent of regulars and Philhellenes to act as spearhead, were to land near Phaleron at night and advance directly on Athens from the south. The plan or variants of it had now failed on three occasions and it now failed again. The irregulars using their traditional methods built little redoubts to give themselves cover from which to fire and did not respond to an order from Church to go to the aid of the forward column. The Greek forces were scattered and when the Turkish cavalry appeared they were cut to pieces. 700 dead were left on the battlefield and 240 more were taken prisoner and put to death. Many more would have lost their lives if the Turks had not abandoned themselves to a riotous victory celebration and so allowed numerous survivors to be evacuated.

Cochrane reported tersely to the Government that ‘the use of the bayonet would have saved most of those who fell on this occasion and would have rendered unnecessary those redoubts which delay the progress of your arms’. In other words, if the Greeks had not been Greeks but disciplined European troops, then the dispositions which Cochrane and Church made might have been successful. It was an apologia which might have been made by General Normann about the Battle of Peta.

The day after the disaster Cochrane sailed away to Poros. He sent a letter to the naval commanders of the powers to say that all hope of relieving the Acropolis was now lost, and urged them to try to prevent a massacre. This had its effect. On 5 June, after complex negotiations in which the commander of the French naval squadron took part, an agreement was reached whereby the Acropolis should be surrendered to the Turks. The Greeks and Philhellenes of the garrison were escorted to Phaleron and taken in French warships to the Greek camp. They were lucky to escape with their lives. Fabvier still haughtily refused to co-operate with Church and in July he retired again with his men to Methana nursing his resentment against Greeks and English alike.

The names are known of forty-two Philhellenes—nineteen Frenchmen, eight Germans, five Corsicans, three Hungarians, two Spaniards, two Italians, two Swiss, and one Belgian—who lost their lives in or around Athens during the few months leading to the surrender.11 A few died of disease or were killed by sporadic shooting within the Acropolis and others were killed in the unsuccessful operations of Fabvier, Gordon, and Heideck. The majority were killed on 6 May, the day of the final disaster, when only four survived out of twenty-six Philhellenes who took the field.

Most of the casualties were men who had arrived in the great French philhellenic movement of 1825 and 1826, but there were still two survivors of the German Legion to be numbered among the dead, and one man who had been at Peta. Among the wounded was the brother of the Whitcombe who had taken part in the assassination attempt on Trelawny in the cave in Mount Parnassus in 1825. The British Ambassador in Constantinople later visited the Seraglio to inspect the exposed trophies and especially to identify a head with a fair beard thought to be that of an English Colonel. It had in fact belonged to Colonel Inglesi, an officer of Cephalonian origin.12

With the loss of the Acropolis it seemed only a matter of time before the last corner of Free Greece was overrun, although the Turks showed no hurry to mount an offensive. The main hope of the Greeks now lay in the powers although it was doubtful whether their attempts at ‘mediation’ could now save them. In July the Treaty of London was signed, which committed Britain, Russia, and France to intervene actively if their proposals were not accepted within a limited time, but the Turks were unlikely to yield now when complete success in Greece seemed within their grasp. The Greek leaders eagerly accepted the terms of the armistice proposed in the Treaty but it is impossible to observe an armistice unilaterally. Instead, they decided to try to restart the war in as many parts of Greece as possible. If the powers were successful and it was decided that Greece should become independent, then the question of boundaries would at once arise. Many captains were uncomfortably aware that they could hardly claim to be included in Free Greece if they were actively co-operating with the Turks. Plans were made to try to rekindle the war in Western and Central Greece and to renew the fighting with Ibrahim in the Morea.

Lord Cochrane meanwhile attempted to keep the war going at sea, but it was no easy task to take on two modern navies, one of which was under the direction of French naval officers. Cochrane realized that his only effective weapon was his reputation and he tried desperately to find some spectacular imaginative stroke that would transform the war such as he had accomplished in South America. In June he suddenly set off with the Hellas and the Karteria to the north-west corner of the Morea, an area of no apparent strategic importance at that moment in the war. Cochrane had heard that the Turkish Pasha was in the area in a small ship and he hoped by a lightning raid to capture him alive and negotiate the freedom of Greece in exchange for his release. The Pasha was not captured although it was a near-run thing. His harem was captured, but harems, although useful, are of little value for political bargaining.

30. The entrance to the Acropolis of Athens, by the Bavarian Philhellene Karl von Heideck, 1835.

For decades later visitors commented on the scars made by the gunfire, and how they exposed patches of bright white on the former honey-coloured patina of the marble, a feature of the appearance of the monuments that was much reduced in the twentieth century.

31. The French entering the ruins of Tripolitsa in 1828.

Cochrane next made a sudden dash across the Mediterranean and on 16 June appeared off Alexandria itself, the great new naval port of Egypt in which Mehemet’s fleet lay at anchor. ‘One decisive blow’, he announced, ‘and Greece is free’, and so with luck it might have been. But the fire ships which were sent into the harbour burned out before they reached their target, and the Greeks refused to obey Cochrane’s order to attack. Instead of striking a decisive blow Cochrane was forced to retire, pursued by the Egyptian fleet. It was clear, however, from the way that Mehemet’s sailors conducted the pursuit that they were prudently ensuring that they would not catch up or come within range. Again Cochrane’s reputation was his defence. On their way back to Alexandria the Egyptian ships encountered the Karteria whose engines had, as usual, broken down but they gave her a wide berth. Again it was only reputation which prevented her from being sunk or captured. Cochrane, on his return to Greece, continued the psychological warfare by sending another letter to Mehemet Ali telling him that he would be back.

Then suddenly, in one day, Greece’s survival was assured. On 20 October 1827 the combined squadrons of Britain, France and Russia carelessly destroyed the combined Turkish and Egyptian fleets in the bay of Navarino. For four hours until darkness fell the guns roared in the last great battle of the sailing ship era. When dawn broke next morning only twenty-nine out of the Turkish-Egyptian fleet of eighty-nine vessels were still afloat and they were badly damaged. About eight thousand men had been killed or drowned. On the allied side some ships had suffered damage but none was sunk. One hundred and seventy-six men had been lost.

The Battle of Navarino, despite all later attempts to glamorize and justify it, was the result of muddle. The allied powers who had signed the Treaty of London in July, which committed them if necessary to physical intervention, did not expect that force would be necessary and discussions were started with Mehemet Ali to try to persuade him to withdraw his forces from Greece. The naval commanders of the allies, however, were expected to enforce a policy on which they had only been given the most general instructions. They were to be neutral and yet to prevent the Greeks and their enemies from fighting—a virtually impossible mandate. Admiral Codrington, the British naval commander who acted as Commander-in-Chief of the allied squadrons, frankly favoured the Greeks and maintained a benevolent liaison with Cochrane, Hastings, and Church, which went far beyond the dictates of neutrality. He permitted and even encouraged them to continue and extend the war, although this was forbidden by the Treaty. With Ibrahim, on the other hand, he was more strict and he instituted a blockade of the Turkish and Egyptian fleets in the bay of Navarino.

Crisis management was not then studied in the Royal Navy, and the word escalation was probably unknown to Admiral Codrington. Nelson’s captains were not accustomed to defusing complex situations or to peacekeeping operations. Yet when all allowances are made, the affair was handled with astonishing lack of regard for the consequences.

On 20 October the allied fleets entered the bay, not with any direct hostile intent but to ensure that they could, if necessary, prevent the Turkish and Egyptian fleets from leaving. A rumour had been heard on the allied side that the Turks might sail to attack Hydra and, on the Turkish side, that their forces in the Northern Morea were being hard pressed by Cochrane and Church. It seemed certain that the Turkish fleet would try to leave Navarino and suspicion on both sides was intense. As the allied fleets entered the bay, a boat was sent to investigate the Turkish fire ships which were apparently being prepared for use. This boat was fired on with musket fire. Another larger boat was therefore sent to lend assistance but it too was fired upon. At this point two of the allied ships began to provide musket fire to cover the boats but this caused one of the Egyptian ships to fire its guns. Thereafter, as they say in the navy, the action became general. In other words every man in the five fleets struggled to kill or to avoid being killed without any further regard to the rights and wrongs of the situation.

The Philhellenes of Europe greeted the news of Navarino with rapture. At last the great powers of Europe had done what they had been urged to do since 1821, to join in the war for liberty, religion etc., and attack the enemies of Greece; but it is no light matter to destroy the fleet of a friendly power without any very clear reason. The Russians alone were delighted as the battle gave them an excuse long wanted to declare war on Turkey and prepare to invade the Balkans. The French were at first embarrassed before deciding to ride on the tide of congratulation and adopt an openly pro-Greek policy.* The British Government had the courage to admit embarrassment, but did so without grace. Admiral Codrington was relieved of his command but not avowedly for his action at Navarino, and in a speech from the throne the battle was officially mildly regretted as ‘an untoward event’.

It took many years of patient diplomacy to rebuild the international order. In Greece itself, however, the significance of the battle was recognized at once. It was now impossible for the Turks to win the war. Without a fleet to reinforce their troops and to attack the Greek island bases, Greece could not be reconquered. A corner of the mainland and a few of the islands were in the hands of a band of self-seeking quarrelling leaders but it was enough. Greece was free.

Footnotes

* The British obtained a firman from the Porte requiring that the monuments of Athens should not be damaged in the fighting. It was given as a bonne bouche at a time when the Turks were obstinately refusing all the requests of the British Ambassador on more important matters. The monuments survived with only slight damage from the war, but this happy result was due more to inadequate weaponary than to respect for the firman.

† See map on p. 284.

* Actually he was an Irishman.

† His Hanoverian Knighthood was bestowed in 1823 for services with the allied armies in 1813.

* On one occasion at the beginning of 1828 one of the officers of the steamship Epicheiresis, Hesketh, was involved in a drunken brawl with a Frenchman on board Cochrane’s yacht. He drew a knife and in the mêlée killed a Hydriote sailor by mistake. Lieutenant Kirkwood was promoted to the command but a few months later he too was involved in an incident. The British and Americans at Poros were used to meeting three times a week for a heavy drinking session. Kirkwood, returning home very late one night, mistakenly rapped on the door of the house of one of his neighbours thinking he was at his own lodgings. When eventually the Greek answered, Kirkwood still did not realize what had happened, but thinking the man was his servant he began to abuse him for being so slow. A quarrel broke out and Kirkwood drew his sword and killed the man.10

* The leader of the French naval mission to Mehemet Ali, Letellier, was present at the battle. The other officers were prudently taken off by the French admiral when the crisis first developed so as to relieve them of the prospect of having to fire on French ships. Letellier also would have been taken off if there had been time.