26 French Idealism and French Cynicism

At the time when Colonel Fabvier was given the task of organizing a regular force in the summer of 1825, another French soldier appeared at Nauplia. He was General Roche, a very different type of Frenchman. Although Roche’s military career, like Fabvier’s, had been spent in the service of Napoleon, he had accommodated himself to the restoration of the Bourbons in 1815. To Roche, the notion that there was a future in Bonapartism ten years after Waterloo and four years after the death of the Emperor was dangerous rubbish. He shared many of Fabvier’s liberal political principles and his hatred of the English, but at the same time regarded such men as Fabvier who had dared to take up arms against France as little better than traitors. Roche was the official agent in Greece of the Paris Greek Committee, a philhellenic organization not so far mentioned in the story. His presence at Nauplia was the result of a complex interaction of circumstances, and his brand of philhellenism had very different roots from Fabvier’s. As usual, concern for Greece was only part of his motivation.

The French Government until 1823 was mainly preoccupied with the situation in Spain. When that problem was neatly solved by invasion they were able to devote more attention to other foreign policy issues. And the success gave them a new confidence. Viewed from Paris, the Greek Revolution had taken a disturbing turn. From all points of view the British seemed to be in the ascendant. First there was the sensational expedition of Lord Byron and then the two loans on the London Stock Exchange. The appeals of the Greeks in the summer of 1825 to put their country under the protection of Great Britain seemed merely to confirm a tendency which was already plain—that Greece was going to be virtually a British satellite; that in yet another part of the world the French had been beaten to the post by their hated rivals across the Channel. In fact, as the reader will have seen, the impact of the British Philhellenes, even including Lord Byron, on the situation in Greece was extremely limited and certainly the influence gained was disproportionate to the resources and energy expended. But, as ever, by the time the news from Greece had been passed to European ears through the filter of distortion and preconception, the situation seemed otherwise. The French Government had also heard of another plan which was circulating in Greece at this time, to invite Count Capodistria from his retirement in Switzerland, to become President of Greece. On the face of it, this plan too was abhorrent since it was assumed (again wrongly) that Capodistria, who had earlier been the Czar’s foreign minister, must necessarily be the agent of some scheme to establish Russian domination in Greece. In any case, it was clear that both the British and the Russians had their supporters in Greece, and France appeared to be out in the cold. Something must be done to reassert the interest of France. With the failure of the schemes to establish French influence through the Knights of Malta, other policies had to be attempted.

At the beginning of July 1825 the British authorities in the Ionian Islands intercepted a letter which revealed that a French Philhellene recently arrived in Greece, Theobald Piscatory, was in fact a secret agent of the French foreign office. He had attempted to suborn Mavrocordato’s secretary, a Frenchman called Grasset, by offering him an important government post in France in exchange for information. Grasset had declined.1 It was also known that Piscatory had arranged to have a long conference on his way out with Capodistria in Switzerland and with a known Russian agent in Greece.

Piscatory’s mission was to explore an idea that had originally come from the Russian Government, that France and Russia should co-operate to settle the affairs of Greece to the exclusion of the British. The initiative failed mainly because Russia felt that she was entitled to what would later have been called ‘a free hand in Greece’. The Russians felt that since Austria had been given a free hand to solve the situation in Italy, and France had been given a free hand to solve the situation in Spain, it was now their turn to solve the Greek question by a military attack on Turkey. Besides disliking this idea, the French were aware, like the British, that the Russian Government’s intelligence about events in Greece itself was poor. For France the real rival was always Britain.

At the same time the British authorities were intercepting letters which gave evidence of a far more important French intrigue, a scheme to provide Greece with a French king. The princes of the French royal family featured prominently in French foreign policy at the time. The unfortunate boys were being hawked round the newly independent states of South America to any country that seemed inclined to accept French help. An extract from one of the early letters gives something of the flavour of how the Greek intrigue was planned. The writer of the (translated) letter was a Greek called Vitales whose imprudent correspondence had also revealed to the British much about the Knights of Malta. The numbers were intended to be a code but the British had little difficulty in identifying the chief characters.

You say that 50 [Villévêque leader of the Orleanists in the French chamber] and 52 [Roche] will come from the friend’s brother [reference unknown] to fetch him bringing the necessary funds for the purchase, and that if this had taken place when the friend proposed, the operation would by this time have been terminated, and thus 39 [Russia] 36 [Austria], and 35 [France] would have remained dalla provista of 29 [Duke of Nemours]. But now we must of necessity have patience, [and] I continue to hope that my offers will have the preference…. The concurrents are already at work and it behoves me to be secret. When it is made known, everything will be concluded or at least the plan will be adopted. Up to the present time it seems that my offers and proposals seem to be well regarded and listened to by those charged with the affairs who are 5 [Constantine Botsaris] and 6 [Colocotrones] and they ordered two persons only, 53 [Ainian] and 57 [Tricoupes] to speak with me. They afterwards will speak with the above-mentioned 5 [Botsaris] and 6 [Colocotrones] who will fix what is best to be done. What this is I cannot say as yet, but the idea was up to the day before yesterday that two persons should go to verify what has been written by 50 [Villévêque] and offered by me and that 30 [Duke of Orleans] should accept for 29 [Duke of Nemours] without opposition on the part of 35 [King of France]. I must now repeat to you how much I am embarrassed by 52’s [Roche’s] proceedings but that I shall do as well as I can for our interests. Let us now see what is to be done if 50 [Villévêque] or 52 [Roche] should arrive here with the earnest money….2

The British watched the development of this scheme for over a year, piecing it together from such obscure fragments as the extract quoted. To recount its vicissitudes in detail and explore the motives and interactions of the main participants would fill a volume. The chief features can however be briefly stated. The Duke of Orleans (later to be King Louis-Philippe of France) formed a focus of opposition in Restoration France for various groups who were opposed to the policies of the King. The Duke of Orleans was not at this time actively plotting to usurp the throne from the senior branch of the House of Bourbon, but naturally the King kept a watchful eye on him. The Duke of Nemours was one of Orleans’ sons, then aged eleven. Under the plan this unlucky boy was to be made King of Greece in exchange for active French help in one form or another but, since a regency would be necessary, control of the country would lie effectively in the hands of the French royal family. The various Greek leaders, especially Mavrocordato, gave indications from time to time that they were in favour of the scheme, but their main motive was simply to encourage as many ties as possible with Western European interests in the hope that the powers would eventually come to Greece’s rescue.

At the time when the Orleanist party, including General Roche, were active in France and in Greece, trying to gather support for their plans, an astonishing change was occurring in French public opinion. During 1825 when public opinion in England was growing weary of philhellenism, a new movement was on the march in France. And the French philhellenic movement was to reach its greatest strength in 1826 at the very time when the English Philhellenes—following the scandal of the loans—were at their lowest point. The French movement was the last and greatest manifestation of militant philhellenism during the Greek War of Independence.

Apart from localized efforts by the professors and churchmen in 1821 and 1822, the first philhellenic organization in France was founded in 1823. It was a sub-committee of the Société de la Morale Chrétienne,3 a philan thropic organization devoted to charitable purposes and social reform, such as the abolition of slavery, improving the conditions in prisons, aiding orphans, the abolition of the death penalty, and the abolition of gambling. Like their colleagues in the London Greek Committee, the first French Philhellenes were men of liberal ideas not particularly interested in the Greeks as Greeks but drawn to take an interest because of their general political outlook.

The Society confined itself entirely to charitable works. In particular it played an important part, along with the Swiss and South German Societies, in sending to Greece the refugees from Russia who had been herded across Europe in great misery in 1822. Sending these wretched victims of distant upheavals to Greece was to do them no service, since in a land thousands of miles from their homeland they had no friends and no means of earning a livelihood. But the charitable work was done in good faith and no one doubted at the time that they would be better off in Greece. Although the Society made no secret of its sympathy with the cause of the Greek Revolution, it was scrupulously careful to do nothing which could be interpreted as giving active support to the revolutionaries. As one of the reports declared:

The philhellenic committees of England, Germany etc. send to the Hellenes officers, armaments, ships, munitions of war etc. Our committee, which is purely philanthropic, will send them (or at least solicit for them) books for their libraries, schoolmasters for their schools, ploughs for their devastated fields, machines and patterns for their factories, directions and advice for all their establishments of public utility.4

The Christian Moral Society collected in all about £300. But already by the end of 1824 it had passed its peak. Public opinion was now demanding more active, warlike measures in favour of the Greeks. In February 1825 was founded the Société philanthropique en faveur des Grecs,5 usually known as the Paris Greek Committee. Many members of the old Christian Moral Society who had been engaged in the relief work came over to join the new committee and it soon outstripped its parent. During the next three years the Paris Greek Committee collected over one and a half million francs, about £65,000 at the current rate of exchange, nearly six times the amount collected by the London Greek Committee during its period of pre-eminence. The Committee became the centre for renewed philhellenic activity all over Western Europe. It sent men, equipment, and money to Greece in quantities which had an important effect on the outcome of the war, and was undoubtedly the best organized and most effective of all the militant philhellenic movements to arise during the war.

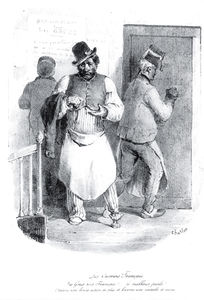

22. French workers contributing money for the Greek cause.

The inscription reads ‘The Greeks are French! Misery speaks! Let us do one more good thing and drink one bottle less‘.

23. French children playing at Philhellenes, lithograph by Charlet, 1826.

The children’s banner reads ‘Grenadiers Grecs, 1re Batt[alion]’. The shields carry the inscriptions ‘Grek’ and ‘Achille’. The enemy banner reads ‘Camp des Turcs.’ The caption reads ‘Vous ferez le Carnage des Turcs, mais vous ne tapperez pas par terre.’ [‘You may make carnage of the Turks but will not hit the ground’]

It is strange that philhellenism in France should not have begun to make a major impact until 1825, four full years after the outbreak of the Greek Revolution. No explanation is fully satisfactory. Part of the reason lay in the attitude of the French Government, which turned increasingly to Greece after the invasion of Spain, and in particular in the efforts of the Orleanists and others to promote their schemes for a French King of Greece. Yet while the shift of emphasis on the part of the French Government from tolerance of philhellenism to more active encouragement was no doubt important, the Government never departed from its sister policy of support for Mehemet Ali. Other causes must be looked for and, as with so many episodes in the history of philhellenism, the influence of Lord Byron is never far away. Much of the stimulus for the upsurge of philhellenism in France in 1824 and 1825 can be attributed to the story and mythology of Lord Byron’s pilgrimage to Greece and his death at Missolonghi.6

French literature in the early nineteenth century was perhaps more influenced by the poetry and the life of Lord Byron than by any other foreigner. Byron’s influence in France was as great as in England and if much of his poetry was misunderstood and the popular view of his character was hopelessly distorted, that is the fate (and the mark) of great men. The depth of the impression which Byron was making in France was not realized until his death was announced on 18 May 1824. A flood of books of poetry on the death of Byron were hurriedly printed—no less than fourteen separate works in 1824 alone. The Opéra immediately arranged for a new tragedy to be prepared on the theme. The students of Paris are said to have spontaneously put on mourning and spent the rest of the fateful day tearfully reading aloud passages from the poems of the great hero. Reprints of his works and reproductions of his (long-since romanticized) portrait were rushed through the presses. Commemorative medals were struck. An exhibition of a picture of the death of Lord Byron by a Greek artist drew large crowds. It is said to have shown the body of the poet stretched out on a bed. An observer records that ‘The sword which Childe Harold had drawn for the cause of the Greeks is hanging on the base of a statue of Liberty. The lyre whose sounds had sustained the sacred fire of independence is thrown near the coffin of the modern Tyrtaeus: its strings are broken. The shadows of some kneeling Greeks surround the death-bed of their noble defender’.7

The sensation caused by Byron’s death drew French attention to the situation in Greece, but quickly a romantic philhellenic movement took off on wings of its own. The books of verse on Greek themes published at this time are numerous. As ever, many were by authors who never again attempted to write poetry. All the old themes were there, comparisons between Ancient and Modern Greeks, the war of the Christians against the infidel barbarians, the call to fight a new crusade. The name of the great romantic poet itself entered the convention of romantic philhellenism. Poets began to call Greece the land of Homer and Byron. The name of Missolonghi which had been virtually unknown in Western Europe before 1824 now carried more exciting associations than Athens or Sparta or Corinth. The Battle of Peta was similarly transmogrified. Poems on the theme ‘The Strangers in Greece’ or ‘The Philhellenes’ made it appear that the events of 1822 had been a great adventure.8

The uniformity of sentiment in these poems is their most surprising characteristic. There must still have been large sections of the population to whom philhellenic themes were not yet banal. Nothing is lost in the translation of this typical extract from a poem on the volunteers setting sail from France to fight for Greece, Liberty, and Religion:

Arise, Parthenon receive your heroes,

Your sacred ruins serve them as a tomb,

Take up your chisels, O Daughters of Memory,

Engrave their obscure names in the temple of glory!

For to die for the cross and for liberty

Is the supreme glory,

It is to die for humanity,

It is to die for God himself !!!9

In a few of the poems the authors convey something of the attempts of frustrated Bonapartists to stage a revival of their cause by their exploits in Greece. Fabvier and his followers were of course the heroes to be compared with the great men of antiquity. The shade of Leonidas was commonly introduced to give advice to his latter-day imitators. Théophile Féburier, who visited Greece as a volunteer, published a poem ‘Corsica, the Isle of Elba, the Greeks, and Saint Helena’10 in praise of Napoleon and the Napoleonic officers who gave their help to Greece when the sovereigns of Europe refused to do so. Byron’s sympathy with Napoleon was not overlooked and the names of the two men were frequently linked. As another poet wrote:

Two heroes, of their time, the light and the flame,

Came, sang, conquered, reigned, languished!

Far from their native land they took their soul.

Saint Helena! … Missolonghi.11

The news of the destruction of Missolonghi in April 1826 sent a thrill of horror all over Europe. But whereas in England the main result was to deliver a virtual coup de grâce to the flagging Greek bonds, in France it led to a further immense intensification of philhellenic feeling. The name of Missolonghi became one of the great rallying cries of the nineteenth century and not a few who responded to it believed that Lord Byron had died in the destruction of the town. It was at this time that Victor Hugo wrote his famous ode ‘The Heads of the Seraglio’, in which he imagines the heads of the heroes of Modern Greece exposed at Constantinople. The name of Missolonghi resounds through the poem until the fateful message arrives ‘Missolonghi n’est plus’. On this occasion too the unknown Alexandre Dumas began his long career with a philhellenic dithyramb sold for the benefit of the Greeks.

In the Paris of 1825 and 1826 it must have been difficult to escape the influence of the friends of the Greeks. In October 1825 there opened at the Académie Royale de Musique a lyrical tragedy The Siege of Corinth with music by Rossini. In November, at the Théâtre Français, was the first performance of Pichald’s tragedy Leonidas. In the box of the Duke of Orleans were two young Greeks, the sons of the Greek Admirals Canaris and Miaulis, sent to France for education at the expense of the Greek Committee, and taken to the theatre to promote the cause in the same way that Blaquiere had taken his Greek boys to the Stock Exchange in London. The author, when his play was printed shortly afterwards, admitted that his huge success was due to the wave of feeling on behalf of the Greeks. For the French, he said, Greece was a second fatherland and the audience was not so much applauding the exploits of the ancient Leonidas as the modern Leonidas, Marco Botsaris.

Exhibitions of pictures were held for the benefit of the Greeks. A charge was made for admission and sometimes pictures were sold. Delacroix’s famous ‘Scenes from the Massacres of Scio’, inspired by the Chios massacre of 1822, was exhibited at the Salon in 1824 where it was bought by the King for the Louvre. Several of Delacroix’s pictures were shown in the exhibitions arranged for the Greeks in May 1826, mostly from Byronic themes, such as ‘The Combat of the Giaour and the Pasha’, ‘A Turkish officer killed in the mountains’. The magnificent ‘Greece expiring on the Ruins of Missolonghi’ came later. At the exhibition arranged for the Greeks in September 1826 Scheffer’s ‘Taking of Missolonghi’ and Colin’s ‘Massacre of the Greeks’ could be seen. The print shops were full of portraits of Fabvier and the usual patriotic handbills adapted to Grecian themes—tearful mothers and beautiful maidens bidding farewell to soldiers off to the wars, returning heroes being decked with wreaths, usually with a few ruined columns and a turban or ataghan worked into the composition to point up the context.

Concerts were held in various towns in France to raise money for the cause. We hear too of balls, raffles, and amateur theatricals. A lemonade dealer gave a day’s profits. In Paris a fashionable jeweller put on sale, for the benefit of the Greeks, brooches in the shape and colours of the Greek flag. The ladies of Paris are said to have divided out the city and made a door-to-door collection.

Books on Greece tumbled from the presses. Over one hundred and twelve new titles in French can be counted for 1825 and 1826—histories, memoirs, verses, pamphlets, brochures, appeals. At least three different works were published under the title Histoire de la Régénération de la Grèce. Increasingly there could be seen on the title pages of new publications the words Vendu au profit des Grecs, ‘Sold for the benefit of the Greeks’.

All the usual philhellenic themes appear in these books as well as the peculiarly French accretions, nostalgia for Napoleon and the ill-concealed dislike of the English. The most influential was probably the short pamphlet by Chateaubriand, Note on Greece, first published in 1825.

‘Will our century,’ he demanded, ‘watch hordes of savages extinguish civilization at its rebirth on the tomb of a people who civilized the world? Will Christendom calmly allow Turks to strangle Christians? And will the Legitimate Monarchs of Europe shamelessly permit their sacred name to be given to a tyranny which could have reddened the Tiber?’12

Chateaubriand had, like Byron, visited Greece in his younger days before the Revolution. Like Byron his book of travel experiences had reflected the literary philhellenic ideas of the time, but unlike Byron Chateaubriand was a major politician in his own right as well as a man of letters.

This huge enthusiasm in favour of the Greeks which swept France in 1825 and 1826 was surveyed with satisfaction by the illustrious men of the Paris Greek Committee. The movement which they had encouraged and nurtured had grown beyond their most ambitious hopes. And despite the vast extension of activity all over France, the Paris Committee remained indisputably in control. In contrast with the London Greek Committee, which always rested on a narrow political base, the Paris Committee gradually extended its membership and influence to an ever wider spectrum of opinion.13 The Committee was brilliant with famous names. The Duc de Choiseul, the Duc de Broglie, the Duc de Dalberg, the Duc de Fitzjames, the Comte d’Harcourt, the Comte de Laborde, Generals Sébastiani and Gerard, the banker Lafitte, the publisher Didot, Benjamin Constant. The Marquis de Lafayette had fought alongside George Washington in the War of American Independence and had proposed the design of the tricolour in 1789 on the outbreak of the French Revolution. Originally the Committee seems to have been largely composed of Liberals and Orleanists, but with the accession of Chateaubriand, who had served as Foreign Minister to the restored Bourbons, it became a national movement. Napoleonic generals and lifelong Republicans joined their names with devoted supporters of the Restoration. Not the least of the effects of the Greek War of Independence was the part it played in bringing about a reconciliation between the bitter political divisions of Restoration France.

The Committee was at first very circumspect in its activities, declaring that ‘it had no other object but to serve the cause of humanity and religion’. Much emphasis was put on the educating of Greek children and the redeeming of captive Greeks from the slave markets. By the beginning of 1825, however, it was preparing to send volunteers and military supplies to Greece. General Roche was sent ahead to prepare the way for their arrival. These military expeditions, which represent the main achievement of French philhellenism, will be described later. At the beginning of 1826 the Committee began to publish a regular bulletin on its activities and this was a skilful vehicle of propaganda. News from Greece was printed and details were given of the expenditure of the Committee’s funds. The Committee took to publishing lists of subscribers to the cause and recording the various activities in support of the cause going on all over France. There are few better stimulants to benevolence than the sight of other people’s names lauded in print for their charitable donations. Soon, long lists were appearing of subscriptions from all walks of life all over France: a tailor giving ten francs, a tanner three francs, a hairdresser contributing 160 francs from a collection made during a hairdressing course, a printer giving his services free for the printing of appeals. General Lafayette subscribed 5,000 francs, Casimir Périer 6,000, the House of Orleans 16,000, the Masonic Lodges 7,927.50. ‘An illustrious traveller in Florence’ gave 20,000 francs. The bulletin carefully recorded the establishment of subsidiary committees, at first only in France but soon elsewhere in Europe. The Paris Greek Committee found itself at the head of a vast movement which by mid-1826 had spread over much of Continental Europe. Russia, Austria and Italy remained obstinately closed apart from a few donations sent out, but philhellenism revived in several cities where it had died out or been stamped out in 1822 or 1823. In parts of Germany previously intolerant governments now turned a blind eye. Philhellenism suddenly became fashionable. If the great noblemen of Restoration France were encouraging the cause, could it really be a danger to minor German states? In Sweden the King’s sister donated a large sum and set up an association of Swedish women to campaign for the Greeks. In the Netherlands there was a notable revival. Even in Prussia, whose Government had been among the most hostile in 1821 and 1822, the mood changed. The subscription list for Berlin was headed by the name of the Queen.

The Swiss Greek Societies, some of which had continued to exist since the early days of the war, played their part in the general revival. In the first years they had happily taken their lead from the South Germans. They then transferred their support to the British. It was only logical to continue their quiet good work under the guidance of the new giant in Paris. The Swiss Societies now had a dynamic leader, the banker Eynard, who journeyed all over Western Europe collecting money for the cause.

The Paris Greek Committee was not all that it appeared. Colonel Stanhope, who attended one of their meetings in April 1825, was solemnly assured by General Sébastiani that there was no question of any rivalry with Britain. The agent of the Paris Committee, General Roche, had, he explained, been specifically instructed on the point. ‘This sentiment’, declared Stanhope, ‘was worthy of a lofty-minded Frenchman’.14

In fact the prime purpose of General Roche’s visit to Greece was to promote the Orleanist intrigue. Although nominally the agent of the Paris Greek Committee, his real master was the Duke of Orleans. The open instructions which he carried specifically prohibited him from indulging in political activities, but he also had secret instructions from the Duke of Orleans. These had been approved by the French Government and were known to only a few members of the Committee (including, incidentally, General Sébastiani). The Paris Committee, like any organization built on contributions from the simple, the honest, and the inexperienced, was an easy prey to unscrupulous leaders.

More than any other philhellenic organization, it was used by the Government as an instrument of its foreign policy. The London Committee had been unashamedly nationalistic and some of its members discussed policies from time to time with members of the British Government. But with the Paris Committee a deliberate attempt was made to take over the direction of the whole movement. The majority of members remained in ignorance that the Committee was under the control of the Government. Certainly the thousands of Frenchmen who donated money did not suspect that the allegedly charitable organization composed largely of opposition statesmen was being used as a front by the French foreign office.

It would be interesting to know whether the French Government gave funds. In 1825 it began to give other forms of support. The restrictions at Marseilles, from which no philhellenic expedition had been allowed to sail since the ill-fated German Legion in December 1822, were quietly lifted. No restrictions were put on the purchase and export of arms intended for the Greeks. The recruitment of volunteers went on undisturbed. Returning Philhellenes were no longer watched by the secret police as suspect revolutionaries, but permitted to give public accounts of their experience in order to boost the cause. Although the intimate nature of the connection between the Committee and the French Government was not known, the Government was not averse to swimming with the current of public opinion and making it appear that it was sympathetic to the cause of the Greeks.

However, at the same time as it was actively encouraging the French Philhellenes, the French Government was faced with the decision what to do with its older policy of support for Mehemet Ali. The consolidation of French influence in Egypt had been pursued as occasion offered ever since Bonaparte’s expedition in 1798. It was connected with the deeprooted French dream of building a position in the Middle East to match the British in India. In the 1820s the fruits of the policy had at last begun to appear. Mehemet Ali, in return for French technical and economic help, seemed quite ready to listen to the advice of the French Government. Everyone knew that Drovetti, the French consul in Cairo, was not there to look after French citizens in distress or to help exporters with the customs formalities. He was one of the most powerful men in the land.

The trouble with this kind of exclusive relationship is that the client government tends to make increasing demands on its patron. In particular, the clients usually develop an insatiable appetite for military equipment and for military assistance.15 A willingness to arm a client state is the ultimate test of international friendship, and to arm a state openly is the ultimate kiss of approval. Mehemet Ali understood these matters.

The European officers who had first brought Mehemet’s army up to a European standard had been recruited privately without active French Government participation. Colonel Sève, the most famous, went to Egypt long before the Greek Revolution; Mari and Gubernatis were former Philhellenes, the rest were Italian refugees. Then in the summer of 1824, when it was already known that the Egyptians were going to invade Greece, Mehemet Ali made a formal proposal to the French Government that they should send a military mission to help complete the training of his new armies.

It was an embarrassing request. As long as Mehemet’s armies were devastating Arabia or the Sudan, no one in Europe was likely to care very much, but Greece! The French tried to warn Mehemet not to involve himself in Europe—Crete possibly but not the Morea, where he was bound to meet all sorts of obstacles from the great powers. But this was a point on which French advice was definitely not going to be taken.

What then should the French do? They found themselves in a common foreign policy dilemma. They were conscious of the strong position they had built up in Egypt and of the strong influence which they exercised over Mehemet Ali. Was it worth putting their huge investment at risk by refusing Mehemet’s request for a military mission? Or should they continue to help him in the hope that they would continue to exercise influence, perhaps restraining influence?

They chose the latter. In November 1824 the mission which Mehemet Ali had requested set sail from Marseilles. It consisted of two generals, Boyer and de Livron, and six other officers. They were recruited secretly by a French General acting on behalf of the Government and their names were cleared in advance with the French foreign office. The French Consul in Egypt was given detailed instructions about the purpose of their mission. In a memorable example of diplomatic disingenuousness General Boyer was told that ‘the interests of Egypt are so linked to those of France that to serve one is to serve them both’.16 When they arrived in Egypt, the French officers were careful to confine their activities to the training of the Egyptian armies and to refuse absolutely to follow them to Greece.

The fact that the French Government had approved the mission to Egypt was, of course, not for publication. To the French public, borne along by the gathering tide of philhellenism and congratulating the Government for its belated recognition of their cause, these men were simply renegades, traitors, unspeakable mercenaries. Some of the officers felt a sense of disquiet at the strange mission to which their patriotic duty had led them and took these charges to heart. They argued unconvincingly to themselves that, since they were only instructors, they had no responsibility for the subsequent actions of the army which they were instructing. The French Government felt that the only thing to do when one has gone too far is to go further. Through 1825 when Ibrahim was devastating Greece, they continued to allow arms and men to go to Mehemet Ali. A list of new officers to join Boyer was under consideration in the French foreign office at the time of the fall of Missolonghi and the Government was still apparently happy to continue the policy right up until the autumn of 1826 when Mehemet Ali himself dismissed General Boyer and brought the mission to an end.

The fact that French officers were actively supporting Mehemet Ali could be concealed or explained away. The officers were expected to carry the ignominy of the Government’s policy personally as part of their duty to France. No doubt the French Government felt that sending a clandestine mission to Egypt was a neat solution to their problem, at the same time preserving their influence and avoiding political embarrassment at home. But no sooner had the mission arrived in Egypt than Mehemet Ali began to make other, even more embarrassing requests. He had decided, he said, that if he was going to conquer Greece then he would have to wrest naval superiority from the hardy sailors of Hydra and Spetsae and destroy them as he had destroyed Psara. What he needed was a fleet. Several modern French warships had recently visited Egypt and their captains had been delighted to show them off to the admiring pasha. In December 1824 Mehemet proposed formally to General de Livron that he should be supplied with two frigates and a brig of war of an exactly similar type to the most modern vessels in service with the French Navy.17

Again the French Government was faced with the dilemma whether to go on with their policy of support or to draw back. The French Admiralty advised that the construction of the vessels requested by Mehemet Ali could not be disguised as merchant-ship building, that only the French navy could supply the requisite skills and materials, and that to accept the contract was bound to be seen as a pro-Turkish gesture, but the Government decided to take the risk. It seemed such a big step to risk breaking with Mehemet and such a small step to provide just a little more help. After all, smaller vessels had already been built for him in France without attracting much notice beyond some fist-waving by the German Philhellenes of 1822. That, admittedly, was before the Egyptian entry into the war, before the destruction of Crete, and of Psara, but by now the French Government was firmly committed to the policy of supporting both sides. At the end of April 1825, that is after news had arrived of Ibrahim’s successful landing in the Peloponnese, the decision was taken to build Mehemet the three warships he had requested. Work began at once in a commercial shipyard at Marseilles and secret instructions were sent to the naval authorities at Toulon to give all the help that was needed.

As the French Admiralty had expected, despite all precautions, the destination of the warships building at Marseilles could not be kept secret. Throughout 1826 the contradictions in French Government policy towards the war in Greece could be more clearly seen at Marseilles than anywhere else. Two ships flying the Greek flag, the Spartiate and the Epaminondas, were received with enthusiasm by the crowds as the Amphitrite had been in England. Expedition after expedition of Philhellenes, French and Italians, left to the sound of cheers and stirring military music. The Marseilles philhellenic committee arranged a ceremony to mark their dispatch of a ceremonial sabre to Fabvier and of a silk banner to Notho Botsaris and the Suliotes, the brave defenders of Missolonghi. Yet all the while everyone knew that behind the walls of the dockyard warships were being built to enable Ibrahim and his Arabs to conquer (and, it was generally believed, exterminate) the Greeks.

Feelings ran high. In the middle of July, when indignation was at its highest following the news of the fall of Missolonghi, an attempt was made to set fire to one of the frigates in the yard. It was a feeble, amateurish effort and little damage was done, but it caused the Government a momentary scare. Rumours of conspiracies flew about. Perhaps the Philhellenes were revolutionaries in disguise—carbonari, Bonapartists, or liberals devoted to violence? The city authorities reminded the citizens of Marseilles that the prosperity of their city depended upon the Levant trade and on shipbuilding—arson against Egyptian ships was bad for business. An investigation was launched but no plot could be discovered. The attempt appeared to have been made by one man, Charles Beaufillot, a Philhellene who had already left for Greece.

On the date set for the launching of the second frigate, 12 August 1826, the authorities prepared themselves for expected trouble. Troops and extra gendarmerie were brought in to guard the yard. The situation remained ominously quiet but, when the moment of launch came, the ship did not enter the water but stuck fast in the mud. Sabotage was at once suspected and the police received word that there was another plot to set fire to the ship, but nothing untoward occurred. A week later a second attempt was made to launch her, but this time the vessel keeled over completely and came to an undignified and helpless halt lying on her side half in and half out of the water.

Whether this was an act of sabotage, an act of incompetence, or an act of God was never established, but it had the effect of delaying the completion of the vessel by many months and adding greatly to her cost. She eventually set sail in April 1827 to join the Egyptian fleet. Fourteen French naval officers were on board to act as instructors. Other vessels and naval officers went later. These officers, like General Boyer and his colleagues in Egypt, loyally played their part in carrying out the policy of France, even though this meant going to war against other French officers who were loyally carrying out the policy of France on the other side.