31 Later

Not until five years after the battle of Navarino was the independence of Greece formally recognized and the international situation regularized. The three allied powers, after failing to negotiate terms with the more suitable candidates such as Leopold of Saxe Coburg,* installed a son of King Ludwig of Bavaria, as Otho King of Greece. For the first years of its independence Greece was virtually a Bavarian colony.

In the years between Navarino and Otho’s accession the centre of the action moved from Greece to London, Paris, St. Petersburg, and Constantinople, as the powers bargained with one another and coaxed the Turks towards a settlement.

For years the Ottoman Government would not recognize the inevitable, that Greece was free, and that nationalism had arrived among the peoples of the Balkans. They stubbornly insisted on some settlement which would preserve the phantom of Ottoman sovereignty even when all power was lost. But without a fleet, active operations against the Greeks were impossible and, in any case, they were again involved in a desperate war with their old enemies the Russians. In 1828 the French Government persuaded the allies to permit a French expeditionary force to be sent to the Morea to arrange for the evacuation of the Turkish and Egyptian forces.

At the insistence of the allies the French forces were not permitted to operate outside the Morea, since it was by no means certain that the final settlement would award any other part of the country to Greece. Meanwhile the two belligerents continued to fight. The Greeks were fighting not now to win the war but to ensure that the new country incorporated as much territory as possible. In 1828 two expeditions were mounted with the specific aim of ensuring that areas which had borne their share of the Revolution should benefit from its success. Church led an army into north-west Greece, a region that had been firmly under Turkish control since the Battle of Peta in 1822. Fabvier led an expedition to Chios in the hope that the sufferings of the 1822 massacre should not appear to have been totally in vain. Characteristically the British Philhellene and the French Philhellene chose their battle grounds as far away from each other as possible.

Fabvier’s expedition was a failure for the usual causes and Chios remained a part of the Ottoman Empire for another eighty-four years. Church had some success in the north-west but his reputation as a general steadily diminished and he was fortunate to escape disaster. Lord Cochrane remained in Greek waters until the end of 1828, but the spectacular success for which he craved never came, and in the long success story of his life, Greece features as an embarrassing interlude. Only Hastings, patiently coaxing his defective steamship to work, achieved military success but he was killed in 1828.

After the arrival of the French expeditionary force in 1828 the excitement departed from the Greek war. Gradually the Philhellenes drifted off. Fabvier, still smarting from the humiliation of Church’s appointment, quarrelled with Capodistria over the future of his regular corps, the need for which had greatly declined since the arrival of the French army. He returned to France in 1829 where, after considering whether to arrest him as a traitor, the French Government joined the public and hailed and feted him as a national hero. He was reinstated in the French army, became a general, and was a prominent politician until his death in 1855.

The friends of the cause in Europe turned their attention to new topics. Edward Blaquiere was drowned in 1832 dashing off in a leaky ship on a characteristic mission to promote the liberal cause in Portugal. Jeremy Bentham took to sending long condescending letters of utilitarian advice to Mehemet Ali, an even less promising pupil than the Greeks. Colonel Sève, the much hated Frenchman responsible for training Mehemet’s troops, rose to be Generalissimo of the Egyptian Army and, as Soleiman Pasha, was to sleep in Napoleon’s bed at the Tuileries as a guest of King Louis Philippe and to be received by Prince Albert at Buckingham Palace.

A few Philhellenes remained in Greece after the war, as officers in the Greek army, lawyers or teachers, but their position was difficult. The Bavarians were disinclined to employ men who had taken part in the war unless they were exceptional in some way, and in the tempestuous politics of Greece purges were frequent. Hane, one of the volunteers of 1822, died in poverty and misery in 1844, having astonishingly survived death by violence or disease during the war. Two other Germans of the 1822 vintage, von Rheineck and Dr. Treiber, eventually rose to high positions in the Greek Army.

Gordon continued his intense love-hate relationship with Greece. He had left in disgust for a second time in 1827, but returned and decided to settle in the country. He built himself a house at Argos and devoted himself to collecting material for his accurate and comprehensive History of the Greek Revolution. During the 1830s he was Commander-in Chief of several expeditions aimed against the klephtic bands who had now reverted from patriots to their traditional role of bandits. He died on a visit to his native Scotland in 1841.

George Finlay, who had come first to Greece in 1823 to worship at the feet of Lord Byron, finally decided to make his home in the country. Throughout his long life an intense romantic philhellenism struggled in his breast with a bitter cynicism against the Modern Greeks. He fought back the romanticism, but he remained bewitched. He wrote a long history of Greece from its conquest by the Romans until his own day which has a touch of Gibbon about it.

Henry Lytton Bulwer (later Sir Henry), who had been sent on the abortive mission to Greece by the London Greek Committee in the autumn of 1824, became violently pro-Turkish in the Greek-Turkish questions later in the century. David Urquhart (later Sir David), who had fought in the later campaigns and whose brother was killed in Crete, also became a noted mishellene. Doctor Julius Millingen, Lord Byron’s physician who changed sides in 1825, was a well-known figure in Constantinople for nearly fifty years and acted as personal physician to successive Sultans. His son, who called himself Osman Bey, was one of the pioneers of modern obscene antisemitic literature.

Greece continued to be racked by civil strife and much of the history of the early years of the Greek kingdom is concerned with the attempts of governments dominated by Europeanized Greeks to impose national unity on the captains. In 1831 the Hellas and the Karteria were destroyed as a deliberate act of spite in an outbreak of civil war. Capodistria was assassinated in Nauplia by a disgruntled Greek who saw himself as a latter-day Harmodius or Aristogeiton. Of the original complex of ideas which had contributed to the Revolution, the imported notion of regeneration made steady progress and eventually vanquished all others. Its only rival was the notion of re-establishing a Greek Empire in the Eastern Mediterranean, the ‘Great Idea’ which regularly reappeared at times of international crisis.

During the nineteenth century the warlords and brigand chieftains were gradually brought to heel under the authority of the Government at Athens, and in time most Greeks came to believe that they were, in fact, the same as the Ancient Greeks. The seventeen hundred years or so between the Emperor Hadrian and the outbreak of the Revolution in 1821 came to be looked upon as a regrettable, even shameful interlude in the country’s history. If in any respect Greece did not appear to be a fully mature Western European state with all the appurtenances of national culture and identity, the blame could always be put on the past and especially on the Turks.

32. A Greek Officer of Nauplia in 1825.

a. Eugène de Villeneuve

b. Sir Richard Church

33. Philhellenes who survived the conflict often had their portrait painted wearing the costume that had been adopted as the Greek national dress.

In 1830 the German historian Fallmerayer published a theory that the Ancient Greek population had been ousted by Slavic immigrants in the in the early middle ages, and that the Modern Greeks were mainly of Slavic race.1 Fallmerayer’s ideas were looked upon as a deadly heresy, and the supposed identity of the Ancient and Modern Greeks became a question of intense political feeling.

Innumerable measures were introduced to emphasize the link with the remote past. Ancient names were resurrected or devised for the coinage, for offices of state, for ranks in the army and navy, for the law. The streets of Athens were named after the famous and obscure men of antiquity whose names have been handed down. It became customary to call Greek children after ancient heroes in preference to saints.

Few signs were allowed to remain in Greece to show that the country once contained a large Turkish minority. The minarets and mosques were destroyed. The Acropolis of Athens was stripped of everything but its ancient remains and rendered a lifeless desert. The marvellously impressive Frankish tower which had stood at the entrance to the Acropolis for hundreds of years was knocked down without regret. An interesting structure on the top of the pillars of the temple of Olympian Zeus, perhaps the hermitage of some Byzantine stylite, was removed as being non-ancient and therefore not respectable. Only shortage of money prevented the Parthenon from being ‘restored’ and rebuilt as part of the campaign to emphasize the alleged continuity of the Hellenic race.

The Greek language is one of the undeniable links between Ancient and Modern Greece, representing a largely unbroken tradition. But that was not considered enough. The Modern Greeks must learn to speak the language of Pericles, or if that seemed too difficult, at least a language purged of foreign accretions, with the ancient words replacing the modern and a simplified ancient grammar. Generations of hapless school children were unsuccessfully inculcated with different versions of ‘purified’ Greek.*

Attempts to replace the unwieldy purified versions used in literature and for official purposes with the ordinary speech of the people, known as demotic, were regarded as blows directed against the feeble unity of the country and its life-giving national myth.2 There were riots in Athens following the publication in 1902 of a demotic version of the New Testament. Those who advocated the abandonment of the unequal struggle to popularize the pure language have been accused at various times of being traitors to the country and to the Church, freemasons, and tools of the Panslavists. In modern times the charge was sympathy with Communism, with strong anti-Slavonic overtones. In the twentieth century the battle for a more general use of demotic seemed to have been almost won when the Colonels, none of whom was personally at home with the pure language, renewed the attempt to ‘correct’ the speech of the whole nation an attempt which led to the abandonment of the artificial language after democracy was restored. In innumerable ways the life, culture, and politics of Modern Greece are still profoundly influenced by the men who inhabited the country in ancient times.

It was the intention of the Greeks who assembled at Argos in July 1829 to confer the Order of the Saviour of Greece upon all the Philhellenes who had taken part in the war. They also intended to record their names in a book of remembrance and to erect a monument to the dead in a church at Missolonghi. But even in providing memorials to express their eternal gratitude—a theme which had featured in innumerable philhellenic poems and addresses—the Greeks did not come up to expectations. The promised lists were not drawn up and soon the names of many of the Philhellenes were forgotten.

The casual visitor might remark upon the tomb of Müller at Nauplia3 or wonder about Marius Wohlgemuth who carved his name flanked with torches of liberty so prominently on the wall of the Theseum in 1822,4 or about Ducrocq who whiled away the time during the siege of the Acropolis in 1826-7 by carving his name on a column of the Parthenon,5 but there was no one to tell him who these men were, why they had come to Greece, or what they had done.

In May 1841 a few former Philhellenes gathered in the Roman Catholic Church at Nauplia for the dedication of a simple monument. It was built by the French Philhellene Thouret and can still be seen. It consists of a miniature triumphal arch of black wood across the doorway of the church. The workmanship is crude, the lettering uneven, the spelling poor, but the total effect is gloomily impressive. The inscription is in French, ‘To the Memory of the Philhellenes who died for Independence. Hellenes, we were and are with you’. On the columns are inscribed the names of two hundred and seventy-eight Philhellenes who had been killed in the war or had died in Greece, with the places where they died. Some of the names are repeated more than once, many are corrupted, or wrongly transcribed. Gordon who died in Scotland has somehow crept in. First names and titles are given but these are not always known or correctly recorded. Against one name it is noted admiringly that he suffered thirty-four wounds. Over fifty places in Greece are recorded as containing the bones of some Philhellene, soldier, student, runaway, disappointed lover, mercenary, adventurer, impostor, romantic, revolutionary, philanthropist, traitor to the Greeks, traitor to the Turks, duellist, suicide.

Plans were made at various times to erect a more permanent monument to the Philhellenes. Research into names was undertaken but the monument was never built. In 1861 the European colony at Athens was asked to name a few Philhellenes who deserved to be commemorated among the Greek heroes of the War of Independence.6 They chose Byron (British), Fabvier (French), Meyer (German and Swiss), and Santa Rosa (Italian), and these names were officially received into the Greek Pantheon. The story of the Philhellenes had itself now passed into myth; reinforcing the myths about Greece which the Philhellenes themselves had found so cruelly disappointing.

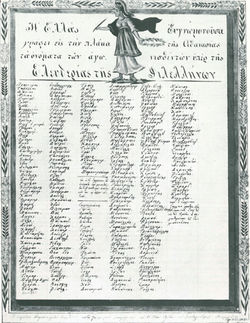

34. ‘Free Hellas thanks the Philhellenes’.

Prepared by direction of the Greek general Makryannis, 1839, to accompany illustrations of the war by the local artist, Panayotis Zographos, presented to the sovereigns of the three allied protecting powers. The inscription translated reads ‘Hellas, in gratitude, writes on the tablet of Immortality the names of the Philhellenes who struggled for [her] Freedom’. From H. A. Lidderdale, The War of Independence in Pictures (Birmingham 1976), with a discussion.

35. The monument to the Philhellenes in the Roman Catholic church at Nauplia.

Footnotes

* Leopold obtained the throne of Belgium, which was set up under the protection of the powers when it broke away from the Netherlands.

* The vocabulary and grammar were changed, not the pronunciation. Present-day Greeks are inclined to insist that the modern pronunciation was used in ancient times even though this implies that the bleat of classical sheep (βή βή) sounded like ‘vee vee’.