5. Dying of Happiness: Utopia at the End of this World

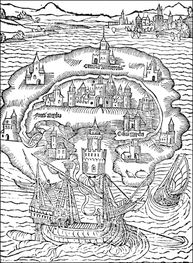

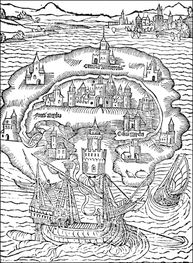

Figure 20. Thomas More, A Map of Utopia

And I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the former heaven and the former earth were passed away; and the sea was no more. And I, John, saw the holy city, the New Jerusalem, descending from God out of heaven, prepared like a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a great voice out of heaven, saying, Behold the tabernacle of God is with men, and he shall pitch his tent among them, and they shall be his people, and God himself shall be among them – their God. And he shall wipe away every tear from their eyes; and death shall be no more, nor grief, nor crying; nor shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away. (Revelation 21: 1-2)

Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of war, where every man is enemy to every man, the same consequent to the time wherein men live without other security than what their own strength and their own invention shall furnish them withal. In such condition there is no place for industry, because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving and removing such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

Thomas Hobbes

The world in general, and the US in particular, is riding a very fine tiger. Magnificent beast, superb claws, etc. But do we know how to dismount? You see this as a very unstable world and a very dangerous world [...].

John von Neumann

In Leviathan Hobbes sees man’s nature as tending to war, including civil war (Hobbes, [1651] 1998). The desirability of avoiding this leads to the acceptance of a clear need for the restraining agency of a social contract whereby the people give up some rights to a government or other authority thereafter responsible for preserving social order through the rule of law. Any abuses of power by this authority are to be accepted as the price of peace. The principle of separation of civil, military, judicial and ecclesiastical powers is rejected in favour of absolute rule. Hobbes’s influence on political thought has endured since the seventeenth century, and is reflected not only in the works of subsequent philosophers such as John Locke and Immanuel Kant, but also in much of the utopian and dystopian literature to be discussed now: in particular the belief in the causal link between rational, moral and political decision-making and self-interest. For Hobbes, ‘Leviathan’ was another term for the community or the commonweal. An odd choice of terminology, given the term’s original and subsequent common usage, in the Bible and in shared mythology, as a force of destruction (usually a sea-monster or a serpent). That dual semantic possibility becomes particularly captivating for the purposes of the discussion that follows of the establishment of more or less dictatorial rule by a few, as the path to social order, and as the only alternative to global anarchy and war.

At the opposite end of the spectrum to Hobbes’s endorsement of governmental autocracy, but equally disturbing, lie a variety of mainly right-wing libertarian factions which encompass American and British neo-liberalism and neo-conservatism, neatly summed up in the person and works of Ayn Rand. In her most well-known work of fiction, Atlas Shrugged, described by Gore Vidal as ‘nearly perfect in its immorality’ (Vidal, 1961), Rand, novelist, playwright and political philosopher admired by figures as influential as Ronald Reagan and Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the Federal Reserve of the United States from 1987 to 2006, depicts a dystopian world and the recipe for setting it to rights: a world ruled by the principle of ‘rational egoism’ (rational self-interest) in which the individual must exist for his or her own sake, rejecting the concept of self-sacrifice. For Rand, existing reality advantages the weak, unproductive an unintelligent because they benefit from the achievements of those at the top while contributing nothing to them. In Atlas Shrugged (Rand, 1957), the most creative scientists, artists and industrialists ‘stop the motor of the world’ by going on strike and retreating to a mountain hideaway where they set up an independent, self-sufficient economy. Without them, society collapses, opening up the possibility of starting a world from scratch which includes only the elite chosen among those who were there before.

The principle of creating utopia after a requisite selective wipeout will be further discussed below. In some scenarios, however, the perpetuation of serviceable subalternity underpins the existing social superstructure. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World is set in London in the ‘year of our Ford 632’ (AD 2540 in the Gregorian calendar, Huxley, 1977). Under this new social arrangement, the vast majority of the planet’s population is unified under one World State, a peaceful, stable society in which everything is provided for and everyone is happy. Natural reproduction has been done away with, and children are hatched in test tubes, decanted and raised in Hatcheries and Conditioning Centres. Society is divided into five castes created in these centres: Alphas, Betas, Gammas, Deltas, and Epsilons, each caste further split into Plus and Minus members. The highest caste is allowed to develop to foetal maturity prior to decanting from its bottle. The lower castes are subjected to chemical interference which arrests intelligence and physical growth to a greater or lesser degree. Alphas and Betas are the product of one fertilized egg developing into one foetus. Members of other castes are not unique but are instead created using the Bokanovsky process (not a reference to, but curiously an interesting homophonic echo of Kurt Vonnegut’s world-changing nihilistic philosophy of Bokononism, Vonnnegut, 1981) which enables a single egg to spawn hundreds of children: ‘standard men and women; in uniform batches […], the products of a single bokanovskified egg. […] You really know where you are. […] Millions of identical twins. The principle of mass production at last applied to biology’ (Huxley, 1977: 23). Words such as ‘mother’ and ‘father’ are now smutty terms or at best now defunct historical infelicities.

All members of society are predestined and conditioned as embryos and as infants for the functions they will perform as adults, and to accept the values that the World State idealizes, including (as in Fahrenheit 451) intense consumerism as the bedrock of social and economic stability. Absolute conformity is achieved by genetic modification and by social and pedagogical training (Elementary Sex, Elementary Class Consciousness, etc.), in the form of phrases repeated to children while they sleep (hypnopaedia).

Alpha children wear grey. They work harder than we do, because they’re so frightfully clever. I’m really awfully glad I’m a Beta, because I don’t work so hard. And then we are much better than the Gammas and Deltas. Gammas are stupid. They all wear green, and Delta children wear khaki. Oh no, I don’t want to play with Delta children. And Epsilons are still worse. They’re too stupid to be able to […] read or write. Besides, they wear black, which is such a beastly colour. I’m so glad I’m a Beta.’ (Huxley, 1977: 42)

And so on, with the relevant variations for each caste. Everyone consumes soma, a hallucinogenic drug that controls fertility and takes users on enjoyable, hangover-free vacations of altered consciousness. Sex is a recreational activity rather than a means of reproduction and is encouraged from early childhood. Only a few women can reproduce and do so only according to the State’s population requirements. Society is governed according to the principle that everyone belongs to everyone else. Notions of family, sexual competition, emotional and romantic bonds are obsolete, and any reference to them is subject to disapproval. Spending time alone is discouraged and any desire for individuality causes consternation on the part of the social group. In the World State, death is not feared. Everyone dies aged 60, having always lived in perfect health.

The conditioning system eliminates the need for professional competitiveness; each individual, in as much as the term has any significance, is bred to do a predetermined job and cannot desire anything else. Incurable dissidents are allowed to escape to securely contained geographic areas (Savage Reservations), where they lead primitive lives.

Problem Children

Bernard, the central protagonist of Brave New World, is a psychologist and an outcast. Although he is an Alpha Plus, something appears to have gone wrong during his incubation. He is shorter than the average for his caste, which gives him an inferiority complex. He defies social norms, despises his equals and is vocal about being different, on one occasion stating that he dislikes soma because he would rather be himself, sad, than another person, happy (an echo of John Stuart Mill’s dictum that it is ‘better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied’ (Mill, 1863: 14). While holidaying with Lenina, a Beta Minus woman, on Malpais (Bad Country) a Savage Reservation (the equivalent of a visit to the zoo or to a wild life park), Bernard, unlike Lenina, becomes interested in the aged, toothless natives (savages). While sightseeing, the couple encounters Linda, a woman formerly of the World State who has been living in Malpais for many years, after becoming separated from her group while on holiday. She has since born a son, John (later referred to as John the Savage) who is now eighteen. Bernard arranges permission for Linda and John to leave the reservation and travel with him back to civilization. Once there, John is treated as exotica and fêted as a pet, but Linda, too old to fit back into society, retreats into a permanent soma holiday. John, appalled by what he perceives to be an empty, wicked and debased society, isolates himself in a remote location, but becomes an object of curiosity, gawped at by tourists, and eventually hangs himself.

Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day (Levin, 1994) shares many common features with both Huxley’s dystopia and Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (Orwell, [1949] 1983). Levin’s narrative, like Huxley’s, is set in a seemingly perfect global society whose defining feature is also ethnic uniformity. In the single race called the Family there are only four names for men and four for women. Instead of surnames, individuals (members) are distinguished by a nine-character alpha-numeric code (nameber). Men do not grow facial hair, women do not develop breasts; reproduction is strictly controlled and sometimes denied. It only rains at night, everyone eats ‘totalcakes,’ drinks Coke and wears exactly the same thing. The world is ruled by a central computer, UniComp, structured according to the principles set out by revered rulers from the past: Jesus Christ, Karl Marx, Bob Wood and Wei Li Chun, the last two being possible references to real life figures such as Adolf Hitler or Josef Stalin and Mao Tse Tung. As in Brave New World, members are instructed as to where to live, what to eat, whom to marry, when (if at all) to reproduce, and which job they will be trained for. They are kept in a state of perfect physical health and psychological contentment by means of regular injections (‘treatments’) consisting of a combination of vitamins, contraceptives and tranquillizers, as well as by weekly meetings with a counsellor who combines the roles of mentor, confessor, and parole officer. Violations against other members (brothers and sisters) are expected to be reported at a weekly confession, either by the transgressors themselves or by others (out of loving concern for the ‘sick,’ deviant member). Compulsory daily television watching (in effect brain washing), as in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Bradbury,’s Fahrenheit 451, acts as a mechanism for inducing unity and community spirit. As in the latter two works, everyone dies at a specified age (in their sixties) for the good of the commonweal: a eugenicist phenomenon, which, as will be discussed, is one of the standard requirements for building utopia in the aftermath of apocalypse.

In This Perfect Day (Levin, 1994) the central character is Wei Li RM35M4419, as a child nicknamed ‘Chip’ by his nonconformist grandfather, Papa Jan, whom in many ways he resembles (‘chip off the old block’). In a world in which not only freedom but free will are suppressed, Chip never quite fits in, and in due course he is recruited by a group of dissidents. When he discovers the existence of islands to which (as is the case with Huxley’s Reservations) it is thought incurable members sometimes defect, Chip and Lilac, one of the members of the dissident group whom he loves, escape, eventually succeeding in reaching Majorca, one of the forbidden islands (re-named Liberty by its inhabitants). In due course Chip, like Bernard in Brave New World, discovers that the islands are in fact containment camps, used by UniComp as convenient repositories for persistent recidivists. Chip, like Winston Smith in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Montag in Fahrenheit 451 (Bradbury, 1976) and Kuno in ‘The Machine Stops’ (Forster, [1909] 2004), dreams of destroying UniComp and setting humanity free. In due course he succeeds in infiltrating UniComp, where he discovers that his life-long struggle to escape has in fact been a test which has now classified him as worthy of joining the ranks of the secretive Powers-That-Be: the programmers of UniComp, a group of men and women who rule through it and, thanks to advanced body-transfer technology (a new body when the previous one becomes too old), live lives of luxury much beyond the age of 62. After more than one year of seeming acceptance of his new life of privilege, Chip succeeds in blowing up UniComp and, leaving behind a humanity now ‘untreated’ and newly awakened to a freedom it does not immediately welcome, he sets off for Majorca, to join Lilac, whom he left pregnant and who he hopes will have stayed true to him.

Beyond Freedom

In the end, a variety of different circumstances may result in the large-scale collapse of social structures and human communities as narrated in film and fiction: natural disasters (acts of God), human error (unforeseen developments in scientific/military/demographic activity) or intentional agency (chemical, biological or nuclear warfare). Post-apocalypse, however, and irrespective of the original trigger, certain common patterns tend to emerge, and structure the emerging survival scenarios: the desire to re-build the world based on the principle of necessary change; the awareness of the dangers of repetition; and, paradoxically, the near-certainty that repetition will not only prove unavoidable but, in the emerging new statuses quo, it will exaggerate the factors that resulted in cataclysm in the first place (intellectual hubris; non-consensual community organization; belligerent inter-group relations; and the polyanesque inability to accept the need for envisaging and forestalling worst-case scenarios).

Defining Utopia

Albeit in some ways counter-intuitively, it is nevertheless possible to argue that the end of the world may be unleashed by arrival at a state of utopia. And in any case, just as apocalypse in the original sense of the term does not necessarily mean universal wipe-out but a stage towards a new beginning, the significance of the term utopia, too, is not necessarily restricted to the common parlance meaning of perfect social, communal or individual bliss.

It may be the case that, somewhere over the rainbow, skies are indeed blue, and that the dreams that you dared to dream really do come true. But it may be equally likely that, as in Gregory McGuire’s somewhat darker revision of utopia in The Wizard of Oz, somewhere, over the rainbow, ‘she [the Wicked Witch of the West] is there too, and the dreams that you’re scared to dream really do come true’ (Rushdie, 2008).

In P.D. James’s The Children of Men (James, 2000), already discussed, in a world where no children have been born for twenty-five years, where there is little to do, no danger of unwanted pregnancies and no future to plan for, one might expect that socially unregulated sex would have become a carefree universal pastime. The reality, however, is somewhat different: people have lost interest in sex, and the state has had to open pornography centres to encourage on-going sexual activity (in case fertility makes a comeback). In a world now peopled by the last generation of human beings, women under 45 undergo a gynecological examination and men have their sperm counted twice a year, in the hope that human life might not, after all, be doomed to extinction. Paradoxically, or perhaps not so, in the awareness that when they die they will not be missing out on anything because there will be nothing left, life becomes worthless for these dwellers at the end of the world. This problem will be examined in greater detail in a subsequent section.

Are You Happy yet?

In common usage the term ‘utopia,’ invented by Thomas More, has come to mean a place of perfection (More, [1516] 1980). Etymologically, however, it involves an in-built ambiguity which is also the central preoccupation at the heart of the on-going discussion. More’s term puns on the Greek outopos (no place) and eutopos (good place). If, as has been argued, a common trajectory of Western narrative – beginning with the basic plot outline of the Old and New Testaments, through the nineteenth century bildungsroman, to contemporary science fiction – leads from contentment (paradise), to disaster (the Fall), to dystopia (life on Earth following expulsion from the Garden of Eden) and finally to new beginnings (the first and second comings of Christ, the New Jerusalem), it may be wise to bear in mind More’s implied caveat: the perfect place may be nowhere (no place): either because it does not exist or because, as discussed in chapter 3, the new beginning ultimately may lead back to whatever it was that preceded apocalypse, with no significant change.

It may be Nice but We Don’t Know It yet

In Philip José Farmer’s To Your Scattered Bodies Go, the hero of the post-apocalypse explains to the other survivors that they must strive to endure because ‘the Unknown exists and we would make it Known’ (Farmer, 1971: 98). For Farmer, presumably, knowledge is both power and worthiness, and leads not to the Fall but to utopia, a new paradise. Apocalypse in this interpretation, hypothesizes an ending but also the beginning of a hitherto unknown possibility:

And I saw the dead, small and great, stand before God; and the books were opened: and another book was opened, which is the book of life. […]

And I saw a new heaven and a new earth: for the first heaven and the first earth were passed away; and there was no more sea. […]

And God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow, nor crying, neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away. (Revelation 20: 12-15, 21: 1-4, italics added)

On a more secular plane, commenting on Philip K. Dick’s Dr. Bloodmoney (Dick, 2007) Fredric Jameson argues that widespread nuclear destruction leads to the removal of corporate capitalism and opens the way to alternative social and economic possibilities which closely approximate another critic’s definition of utopia as a ‘Jeffersonian-style commonwealth beyond the bomb’ (Aldiss, 1975: 42). The problem at the heart of Jefferson’s thought, however, which both Jameson and Aldiss opt not to confront, but which will be addressed here presently, is that Jeffersonian utopias, like all other utopias, incorporate fundamental principles of self-contradiction, discrimination and autocracy that in the end erase the line separating them from autocratic dystopias. Jefferson (a slave-owning abolitionist), indeed, himself exemplifies a phenomenon common to almost all utopias: namely that under them, just like under any demagogy, all animals may be equal but some are almost always more equal than others.

Let’s not go there

The power and desire to define utopia (a good place), and to impose it globally, requires the identification of its antithesis, dystopia (a place of wretchedness), so as to avoid it. The concept of dystopia has preoccupied many thinkers: from C. Wright Mills’s vision of American social stratification and exclusion or Foucault’s panoptically invigilated carceral society, to the defeatism of numerous social commentators who have variously remarked on the present-day Disneyfication of global culture (‘a McDonald’s in every village,’ Mills, 1959). More unexpectedly, the same preoccupation with a potential loss of individualism informed Eisenhower’s warnings about the possible consequences of the expanding American military-industrial complex as the instigator of global conformism (Booker, 2001: 12).

Philosophers such as Jean Paul Sartre (Sartre, 1947) and Rosemary Jackson (Jackson, 1981) argue that fantasy (which in a broad sense can encompass science fiction, horror and utopian writing), is the genre within which the forbidden, the dreaded, the desired and the unutterable can be contemplated. If so, it may after all not be surprising that absolutist politics, translated as the dream of power – including global power or totalitarianism – may after all underpin utopian imaginings of a perfect world.

As regards a definition of an utopian imagined world, clearly, not only is one man’s meat another man’s poison (an expression which, taken literally, in any case dismisses the female half of humanity), but, given enough time, even one’s own meat of choice can grow stale. Historically, it has often been true that the occurrence of cataclysmic events in nations’ economical, political and territorial systems has not infrequently led the way to dictatorship under the guise of the only (final) solution to systemic instability. Utopia, taken to be the solution to scenarios of universal collapse, retains an affinity to destruction that links it to the catastrophic events that possibly made it desirable in the first place. And not unexpectedly, in response to the anarchy of the immediate post-apocalypse, the establishment of utopian order often exhibits some of the defining characteristics of dictatorship.

Definitions of utopia often reveal as much about their instigators as they do about the status quo they seek to replace. More worryingly, the utopian formula, just like the post-holocaust statuses quo discussed in chapter 3, ultimately tends either to repeat or reinvent, with minor modifications, the problems that triggered the original catastrophe.

Lies, Damned Lies and Utopias

The elimination of difference is, to a greater or lesser extent, the prerequisite of most utopian visions, and it is through this that their potential for autocracy becomes most clearly manifest. Brave New World (Huxley, 1977), This Perfect Day (Levin, 1994), Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, ‘The Machine Stops’ (Forster, [1909] 2004) and Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang (Wilhelm, 2006) all envisage worlds in which greed, selfishness, unfulfilled desire and polymorphous brands of misery are replaced by uniform human placidity. This is articulated with some eloquence by Wei, creator of the submissive global community under the rule of UniComp in This Perfect Day:

One goal, one goal only, for all of us – perfection, he said. We’re not there yet, but some day we will be: a Family improved genetically […]; perfection, on Earth and ‘outward, outward, outward to the stars.’ […] I dreamed of it when I was young; a universe of the gentle, the helpful, the loving, the unselfish. I’ll live to see it. I shall live to see it. (Levin, 1994: 304-05)

In Levin, Wei’s vision of a world population genetically created to be born perfect, is not quite achieved, and people must still be chemically controlled by means of weekly ‘treatments.’ In Atwood’s more fully achieved nightmare, Oryx and Crake (Atwood, 2004), that dream is already a reality. In the research laboratory aptly named Paradice, the genetically engineered Crakers are ready to begin re-populating the planet from tabula rasa, in the aftermath of a virus by means of which their creator, Crake – scientist turned quasi-divine destroyer and demiurge – sought, albeit failed, to annihilate the entire human species:

[W]ith the Paradice method […] whole populations could be created, that would have preselected characteristics. Beauty, of course; […] And docility; […] What had been altered was nothing else than the ancient primate brain. Gone were its destructive features […]. Hierarchy could not exist among them, because they lacked the neural complexes that would have created it. Since they were neither hunters nor agriculturalists hungry for land, there was no territoriality: the king-of-the-castle hard-wiring that had plagued humanity had, in them, been unwired. They ate nothing but leaves and grass and roots and a berry or two; thus their foods were plentiful and always available. Their sexuality was not a constant torment to them, not a cloud of turbulent hormones: they came into heat at regular intervals, as did most mammals other than man. (Atwood, 2004: 358)

The sacrifice of the individual’s right to difference and therefore freedom (including freedom from the obligation to be part of an enforced homogeneity within the autocracies variously depicted in the texts above) is a prerequisite in the pursuit of happiness. In Orwell, Winston Smith’s dissidence is uncovered and he is subjected to unimaginable torture which, with variations, is also par for the course in many other fictions of dictatorship. Orwell’s diabolical twist, however, consists in ultimately endowing Winston with the consciousness that, in the nonlife of lethal tedium that follows the horrors experienced in Room 101 (a place of à la carte despair where that which each individual most fears comes true), the relief of death (ironically also longed for by the inhabitants of Julian Barnes’s utopian Heaven, to be discussed) will only be granted after absolute defeat is acknowledged. In Orwell, this takes the form of a genuine return to conformity in the form of learning sincerely to love one’s Nemesis. Before being caught, both Winston and Julia mistakenly believed that the brutal hegemony enforced by Big Brother could not penetrate the innermost reaches of the self:

[They] can make you say anything – anything – but they can’t make you believe it. They can’t get inside you. […] They could lay bare in the utmost detail everything that you had done or said or thought; but the inner heart, whose workings were mysterious even to yourself, remained impregnable. (Orwell, 1983: 147-48)

They are, however, mistaken. The permanence of Big Brother requires more than outward conformism: it requires people to have the right opinions, and, more importantly even, the right instincts, ‘a loyal willingness to say that black is white when Party discipline demands this:’

But it means also the ability to believe that black is white, and more, to know that black is white, and to forget that one has ever believed the contrary. (Orwell, 1983: 182)

As in Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day, albeit with greater brutality, the Party seeks not to suppress dissidence but to ‘cure’ it; it is as interested in crimes of thought (‘thoughtcrime’) as in crimes of deed: ‘we do not merely destroy our enemies, we change them’ (Orwell, 1983: 218). Perfect, heartfelt conformity is the requirement for any utopia, however defined. Thus, in the end, it does not suffice that Winston betrays Julia: he must want to betray her. And likewise, the status quo can only afford to execute him when, rather than merely appearing to love Big Brother, he actually does:

We are not content with negative obedience, nor even with the most abject submission. When finally you surrender to us, it must be of your own free will. We do not destroy the heretic because he resists us: as long as he resists us, we never destroy him. We convert him, we capture his inner mind, we reshape him. We burn all evil and all illusion out of him; we bring him over to our side, not in appearance, but genuinely, heart and soul. We make him one of ourselves before we kill him. […] You are a difficult case [Winston. But… everyone] is cured sooner or later. In the end we shall shoot you. (Orwell, 1983: 219, 236)

And indeed, in the last devastating sentences of the novel, Winston attains his epiphany and gains entry into utopia which, in the nightmare universe of Big Brother, is defined as utterly sincere obedience and death:

Winston, sitting in a blissful dream, paid no attention […]. He was back in the Ministry of Love, with everything forgiven, his soul as white as snow. He was in the public dock, confessing everything, implicating everybody. He was walking down the white-tiled corridor, with the feeling of walking in sunlight, and an armed guard at his back. The-long-hoped-for bullet was entering his brain. […] But it was all right, everything was all right, the struggle was finished. He had won the victory over himself. He loved Big Brother. (Orwell, 1983: 256)

Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, is an extreme, distorted example of how utopia, in the sense of perfect contentment (unconditional acceptance of, and love for, that which forcibly controls us, be it God the Father or Big Brother), is not only difficult to imagine but, contradictorily, carries its own problems. But there are others, which even Orwell did not fully explore. For example, can utopia be trusted to be real or is it in fact a figment, a quasi-psychotic state with an inevitable wake-up call (Brave New World, Huxley, 1977; This Perfect Day, Levin, 1994; The Time Machine, [1895] 1982; ‘The Machine Stops’)? In addition, and even more disturbingly, if followed to its logical conclusion, a question remains as to whether, having reached utopia (imagined or even real), it can last forever.

This Dream is not My Dream

Narratives that have addressed this last question include John Wyndham’s Trouble with Lichen (Wyndham, [1960] 1982) and Julian Barnes’s episode (or, tantalizingly, inconclusive half-episode), ‘The Dream,’ in History of the World in 10½ Chapters (Barnes, 1990). In Wyndham, as discussed already, a biochemist discovers, if not actual utopia, the secret of eternal life, or at least the means of radically slowing down the ageing process, thereby extending life expectancy indefinitely. One of Wyndham’s strengths as a writer lies in his ability to imagine unusual situations and explore their unintended consequences. In Trouble with Lichen the social and demographic consequences of a massively increased life span constitute the central preoccupation of the narrative, and typically he leaves us not with a facile solution to the problem but rather with questions still unanswered at the end. Paradoxically, and contrary to any acceptable utopian outcome, in Trouble with Lichen one obvious consequence (or problem) of finding the Elixir of Life is death: the non-viability of non-finite human existence in a world with finite resources.

Why Can’t You Just Be Happy?

A related problem revolves around the paradox that even if unproblematic utopia is achieved, it might eventually grow stale (at which point, by definition, it ceases to be utopia, and, because unchangeable, becomes a torment: Room 101). If so, achieving the dream of eternal life becomes ultimately a poisoned sweet: a recurrent theme in literature of all genres: from Edgar Allan Poe’s gothic short story ‘Ligeia’ (Poe, [1839] 2003), J.K. Rowling’s creation of Voldemort in the Harry Potter series (Rowling, 2000, 2008), Neil Gaiman’s cult comic book series, Sandman (Gaiman, 1991-2007), Julian Barnes’s satire, ‘The Dream’ (Barnes, 1990) to John Wyndham’s Trouble with Lichen, already mentioned:

‘I’m frightened […]. I don’t want it. I don’t want it.’ […] Me, going on and on and on. […] Everybody getting old and tired and dying, and jus’ me going on and on and on. It doesn’t seem exciting now […], I’m frightened. I want to die like other people. Not on and on – jus’ love and live and grow old and die. That’s all I want to do. (Wyndham, 1982: 67-68)

Only the mad or the bad can countenance non-finitude without stumbling into paradoxical self-destruction, or without at least desiring it, like Phil Connors, who in Harold Ramis’s Groundhog Day (Ramis, 1993), farcically seeks to escape entrapment in the perpetual present by repeated (and repeatedly failed) suicide attempts. In Wyndham’s Trouble with Lichen Zephanie comes to a conclusion not dissimilar to Barnes’s Heaven-entrapped hero, to be discussed: namely, that perpetual enjoyment of what you enjoy paves the path to satiation, to the inability any longer to desire, and thence to misery: ‘After a while, getting what you want all the time is very close to not getting what you want all the time’ (Barnes, 1990: 309). Similarly, in a clear Faustian pact, J.K. Rowling’s Voldemort, the most dangerous wizard in the world, curiously representative both of Satan and of the latter’s doomed business associates, seeks to buy immortality in exchange for his soul: he performs magic that rips it into seven different shreds and stores those fragments in external objects (horcruxes): ‘I, who have gone further than anybody along the path that leads to immortality’ (Rowling, 2000: 566). As with every dream that comes true only to betray itself, by separating himself from portions of his soul, Voldemort (previously Tom Riddle), becomes the architect of his own destruction:

‘A Horcrux is the word used for an object in which a person has concealed a part of their soul. […Y]ou split your soul […] and hide it in an object outside the body. Then, even if one’s body is attacked or destroyed, one cannot die, for part of the soul remains earthbound and undamaged. But, of course, existence in such a form…’

Slughorn’s face crumpled and Harry found himself remembering words he had heard nearly two years before.’

‘I was ripped from my body, I was less than spirit, less than the meanest ghost… but still, I was alive.’

‘… few would want it, Tom, very few. Death would be preferable.’ (Rowling, 2005: 464-65)

Rowling’s concept of the split soul which grants immortality to the earthly body albeit at a price, appears in a variety of myths including the Norse tale, ‘The Giant Who Had No Heart in his Body’ (Asbjørnsen and Moe, 1888) and is discussed in various myths in James Frazer’s The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (1993):

We have seen that in the tales the hero, as a preparation for battle, sometimes removes his soul from his body, in order that his body may be invulnerable and immortal in the combat. With a like intention the savage removes his soul from his body on various occasions of real or imaginary peril.

Thus the idea that the soul may be deposited for a longer or shorter time in some place of security outside the body, or at all events in the hair, is found in the popular tales of many races. It remains to show that the idea is not a mere figment devised to adorn a tale, but is a real article of primitive faith, which has given rise to a corresponding set of customs. (Frazer, 1922)

In Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, winner of several awards including the Nebula, the most prestigious prize in science fiction, Hob Gadling, the central character, not unlike the knight in Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (Bergman, 1957), meets Death and her brother Dream in a tavern in London in 1389, and on a whim is granted eternal life by the former. In the course of six episodes taking place over the centuries, Gadling meets Dream several times, the last time being in 1989. As the series progresses, we learn that in the aftermath of Dream’s death, Gadling is sometimes offered the option of death by Death herself, and on at least one occasion is tempted. Although he never actually takes up the offer, it becomes increasingly clear that eternal life may not after be as desirable as he had supposed.

This admittedly counter-intuitive problem is taken to its logical conclusion in Julian Barnes’s ‘The Dream,’ in which after a few millennia in Heaven, and faced with the prospect of an eternity of instantly gratified desires (perfect sex on demand, total gastronomic satisfaction, unfaltering scratch performance at golf, every possible wish automatically fulfilled, etc.) the protagonist asks to be allowed to die again, but this time without the option of going to Heaven. Ultimately, like almost every person since humanity began, he finds that in the end ‘Heaven’s a very good idea, […] but not for us’ (Barnes, 1990: 309).

The Problem with Perfection

Barnes’s scenario, like the other examples mentioned, takes the act of imagining utopia to an extreme which is also its negation. And in doing so it also echoes less explicit problems common to much utopian writing. John Carey’s panoramic survey of utopias (there are many different kinds and they seldom agree) defines utopia as the imaginary site of desire, and dystopia as a place of fear (Carey, 1999: i-xii). It is to be reasonably expected that dystopias should depend upon the destruction of whatever/whoever was in place beforehand. Dystopia and utopia, however, rather than necessarily antithetical, may be categorically contiguous. If being in a state of desire implies that that desire is not yet satisfied, the attainment of utopia (absolute contentment) must invariably require the abolition of human longing (for that which might be but which is not yet achieved). And the elimination of the ability to desire, even if not actually dystopian, may in fact be either equidistant from both dystopia and utopia, or else impossible, because, as Barnes’s hero discovers, in a place where your wishes are automatically fulfilled, the only impossible desire turns out to be the wish to become someone who never gets tired of eternity, which in turn may only be possible by means of ceasing to exist (obliteration): ‘you can’t become someone else without stopping being who you are’ (Barnes, 1990: 308); and stopping being who you are is dying, by any other name.

To count as a utopia, an imaginary place must be an expression of desire. [...] Anyone who is capable of love must at some time have wanted the world to be a better place [...]. Those who construct utopias build on that universal human longing. What they build may, however, carry within it its own potential for crushing or limiting human life. (Carey, 1999: xi)

By this reckoning, if all longing is satisfied, desire becomes meaningless, but so, therefore, does existence itself. It may be for this reason that visions of utopia often exhibit characteristics akin to the dissatisfactions of dystopia. Faced with limitless choice and guaranteed satisfaction, Barnes’s protagonist opts to have his favourite meal (a standard English breakfast) for breakfast, lunch and dinner throughout all eternity. The fact that he opts for eternal sameness (the same type of homogeneity/de-individuation imposed in the supposedly perfect but in reality nightmarish societies of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Levin’s This Perfect Day and Huxley’s Brave New World), rather than choosing optimum variety, illustrates Barnes’s paradox that while human existence may be defined by a longing for perfection, perfect happiness is incompatible with its attainment. Even perfect bliss (the abolition of unsatisfied desire), it would seem, leaves something to be desired. Like Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, or Timothy Findley’s Lucy/Lucifer in Not Wanted on the Voyage (who, rather than falling, ‘leapt’ away from Heaven where the weather was always nice, in search of somewhere where sometimes it might be stormy, Findley, 1987: 102), when humanity possesses perfection it longs if not for its antithesis, at least for something different (and by definition imperfect). Following on from Robert Browning’s plaintive ‘ah, but a man’s reach must exceed his grasp – or what’s a heaven for?’ (Browning, 1883: 184-93), it may be the case that whatever heaven is for, even it may not appeal, if it is forever. In Barnes the attainment of Heaven nullifies its essential definition. When all desire is fulfilled, there is nothing left not to die for.

Nothing is Perfect

A related problem in certain considerations of utopia refers to the probable unreality of it, and the possibility that apparent perfection is actually its opposite, namely a gigantic confidence trick. Philip K. Dick’s novel, Time out of Joint (Dick, 2003) addresses the possibility not only that perfection is not attainable but that, when you think you have attained it, what awaits is instead the inevitable discovery that the world is even more flawed than might have been feared. In Time out of Joint the central character, Ragle Gumm, discovers that what he took to be reality is in fact a fabricated stage setting which duplicates the reassuring 1950s reality of his childhood. Gumm eventually learns that in effect the date is 1998, a time when the Earth and the Moon are involved in a war of independence waged by the lunar colonies. Unbeknownst to himself, Gumm possesses the extra-sensory ability to predict where lunar nuclear strikes will be aimed. This knowledge is tapped into when he plays (and always wins) a supposed newspaper quiz (along the lines of spot-the-ball puzzles) that asks the question ‘where will the little green man be next?’ The fictitious town created for him – similar to that in The Truman Show (Weir, 1998) – provides a safe environment in which he is able to perform this task without any awareness either of what he is doing or of the military purposes for which his gift is being used. In the end, both Gumm and Truman manage to escape, the former to the Moon colonies and the latter by stepping outside the gigantic stage set of the fictitious town and over the cardboard ‘horizon’ into the real world.

In Kurt Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan (Vonnegut, 1999), much as in Time out of Joint (Dick, 2003), The Truman Show (Weir, 1998), This Perfect Day (Levin, 1994), ‘The Machine Stops,’ The Penultimate Truth (Dick, 2005), The Simulacra (Dick, 2004) and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (Adams, 1979), or indeed the Old and New Testaments, individuals,’ or even the whole of humanity’s existence is the product of Deus ex machina manipulators; a concept later used with mass market appeal in the unprecedented box-office smash trilogy The Matrix, The Matrix Reloaded and Matrix Revolutions (Wachowski Brothers, 1999, 2003, 2003). In these three films, preposterous plot lines involve abundant Biblical allusions (including, as in the The Terminator series, the insistence on trinitarian references). Of note is for example the central casting of a saviour (aptly named Neo), who in the final instalment lays down his life to free humankind from the Matrix: a computer-generated simulated reality created as a device for pacifying humanity in a world controlled by machines which, in the early twenty-first century, had taken over the world in order to use human beings as bio-fuel.

Other than Jehovah’s Eden, most of the pseudo-demiurgic worlds described above are classifiable as utopias in the sense that with some exceptions they are, at least from the point of view of their creators, ideal settings, ‘good places,’ or, as the terminology of current political discourse would have it, ‘fit for purpose.’ The purpose in question refers of course to the requirements of each of the overlooking demiurgic powers: in Dick’s Time Out of Joint (Dick, 2003) the military establishment; in Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide (Adams, 1979) the mice running the laboratory experiment; in Levin’s This Perfect Day (Levin, 1994) the tiny minority of about one hundred ‘programmers’ who exercise world domination; and in Weir’s The Truman Show (Weir, 1998) the producer of a soap opera serving the interests of corporate profit.

There is a common thread running through these and other understandings of utopia. First, utopia is utopian only according to the parameters of the relevant power hierarchy (in the works mentioned above, the government, the mice, the ruling establishment, the producer of the show). Second, utopia is only achievable at the price of exclusion or elimination (of difference, of dissent and of the concept of a democratic entitlement to Truth). And third, utopia is only maintainable through the elimination of individual autonomy in favour of despotic control.

In Plato’s ideal Republic and in his Symposium, for example, an over-arching definition of good and bad or right and wrong sets out a series of imperatives: the banishment of artists and poets; the causal link of goodness and beauty, ugliness and wickedness; the necessity of censorship; the desirability of eugenic practices; and the idealization of paedophilia (sex between adult men and young boys of unspecified age) within an ideology that brooks no argument. Similarly, the protagonists/ subjects of the various plots (in both senses of the word ‘plot’) detailed above are impotent against the underpinnings of their existences: they have been removed from reality, cast into someone else’s narrative and disenfranchised from the exercise of free will by existential scripts of monumental proportions, predetermined by someone other than they themselves.

Happiness Beyond End-Time

The latter is also true in re-constructed worlds following apocalypse: Dr. Bloodmoney (Dick, 2007), This Perfect Day (Levin, 1994), Brave New World (Huxley, 1977), The Chrysalids (Wyndham, [1955] 1984), The Kraken Wakes (Wyndham, [1953] 1980), The Day of the Triffids (Wyndham, [1951] 1984), Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang (Wilhelm, 2006), Earth Abides (Stewart, 1973) and numerous other works.

Possibly the most dystopian of all scenarios, curiously, is absolute resolution (and therefore, in theory, fully-achieved utopia) as illustrated by Wim Wenders’s Until the End of the World (Wenders, 1992). The film takes place in late 1999 and the threat posed by technology (nuclear annihilation, in this instance brought about by error rather than terror) underlies the plot. An out of control nuclear satellite is in imminent danger of re-entering the atmosphere and contaminating large areas of the planet. Disorder ensues, with large numbers fleeing the likely sites of impact. The central protagonist, Claire Tourneur, escapes the congestion created by the fleeing population by driving off the motorway, and subsequently encounters a hitchhiker seemingly in flight from an undisclosed pursuer. Claire falls in love with the fugitive (Sam) and subsequently discovers that he is the son of a scientist, who has absconded with one of his father’s prototypes from a top-security research project. Multiple government agencies and some bounty hunters are in pursuit to recover it.

The prototype is a device for recording and translating brain impulses — a camera for the blind, but subsequently perfected as a device to record human dreams. Until the End of the World both embraces technology and rejects it as a force for potential global destruction, a problem that echoes all of the plots discussed above. Although Wenders’s film ultimately privileges the centrality of human relationships, it sees them nonetheless as inseparable from their technological context. The title possibly alludes to the ideal of a romance capable of lasting through all time, and although this ideal is not achieved, some human relationships do endure, occasionally with the aid of technology: Claire and Sam, for example, overcome the hardship of separation and nurture love and communication by means of a variety of futuristic and not-so-futuristic technological innovations. On one occasion, for example, Claire tracks down Sam’s location via computer when he uses his credit cards, and follows him around the world in order to satisfy her desire to know more about him. Contradictorily, it is the seductive capabilities of technology (the dream images have an addictive effect and incapacitate the users of the device for normal life), rather than the destructive ones (the nuclear threat), that ultimately destroy the film’s primary relationships between husband and wife, parent and child, or lovers. Thus, an ostensibly benign technological innovation ultimately introduces a greater menace than nuclear Armageddon, and although Claire eventually overcomes her addiction to the dream images, her relationship with Sam is irreparably damaged. In the end, the characters discover they no longer have homes to return to and must either flee the earth or seek a nostalgic past, in order to escape stagnation and achieve transitory redemption. The final images of the film show Claire in flight from a world fallen into widespread alienation, decay and corruption. She lives completely alone aboard a satellite, literally disconnected from the Earth (free from the laws of gravity) and works for an ecological protection organization, Greenspace. She is also cut off from the rest of humanity, contact being carried out via satellite. James Berger interprets the ending of the film as depicting Claire metamorphosed into a ‘high-tech angel protecting the Earth from pollution,’ but also as ‘the transparency, the technological “natural,” the post-apocalyptic cipher who has gone through the neuro-video event of primary process to become the presiding genius of the next millennium’ (Berger, 1999: 46-47).

Until the End of the World sets up a dialectic of apocalypse as cataclysm synthesized into revelatory epiphany. But if at the end Claire is presented as a space-age guardian angel, even so the resolution reached is characterized by a dimension of alienation that Booker likens to Foucault’s disciplinary (carceral) society and he himself calls routinization:

Routinization is closely related to […] conformism […] the way in which, under modern capitalist society, every aspect of life becomes regimented, scheduled and controlled for maximum economic efficiency. (Booker, 2001: 17)

The Bliss of Non-Difference

Fredric Jameson (Jameson, 1984) argues that fantasy and science fiction articulate a desire to escape routinization and alienation. If so, they may also sometimes provide a path through that which is most feared, thus safeguarding arrival at a state of safety beyond apocalypse which one might define as utopia. If apocalypse was brought about by the unleashing of unbridled force (terror), of randomness (error), and of the forces of chaos, utopia requires absolute, highly regulated conformism. By the same token, under utopia, the price of nonconformism (the freedom to be different) is unhappiness and ultimately punishment, writ small, large or very large (global), something which accounts for its forcible elimination in many of the works discussed. In Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith is the distillation of the misfit, a rebel without a clearly identified cause, who deviates not in the name of any particular agenda (he has no plan for an alternative society) but simply because he cannot do otherwise. Ultimately, from the point of view of the status quo but also of himself, since he is unable to effect change his unhappiness has only one solution, namely the abolition of the very essence of what he is, followed by non-being. After being tortured into submission to the will of Big Brother, Winston dies happy because he no longer exists in any real sense. Instead, he has learnt to love that against which he had previously defined himself, which had destroyed his mind and which will now destroy him.

In Orwell, as in any other utopia, there is always an unquestionable truth, even if, as for example under the watchful eye of Big Brother, that truth is re-written when convenient (double talk). Within this utopia, as in Brave New World (Huxley, 1977), Fahrenheit 451 (Bradbury, 1976) and This Perfect Day (Levin, 1994), all, with the exception of those who are ‘sick,’ have abdicated individuality and surrendered to mass-produced and quality-controlled emotion, ranging from love for Big Brother to all-surround TV and organized daily sessions of Hate. Similarly, in Brave New World (Huxley, 1977), following the logic of This Perfect Day (Levin, 1994), everyone, from the most hubristic Alpha to the lowliest Epsilon, is happy to be just what they are. And in Fahrenheit 451, extreme versions of homogenized culture and chemical treatments anaesthetize the masses into submission, such that only a coincidence of unlikely events can lead to temporary failure in an otherwise smooth operation.

Once, books appealed to a few people, here, there, everywhere. They could afford to be different. But then the world got […] double, triple, quadruple population. Films and radios, magazines, books, levelled down to a sort of paste pudding norm […]. Many were those whose sole knowledge of Hamlet was a one-page digest in a book that claimed: now at least you can read all the classics; keep up with your neighbours. […] We must all be alike, […] everyone made equal. (Bradbury, 1990: 91-95)

In Huxley, Levin and Bradbury alike, sameness is enforced by drugs or censorship or both, supposedly for the good of all: ‘We’re the Happiness Boys […]. We stand against the tide of those who want to make everyone unhappy with conflicting theory and thought’ (Bradbury, 1990: 68-69).

In This Perfect Day, Chip’s propensity for dissent may be due partly to a congenital flaw (manifested also in his having one green and one brown eye) but its full potential is awakened initially as the result of the teachings of a destabilizing agent, Papa Jan, his grandfather, who is one of the old, never fully ‘normalized’ generation dating back to pre-unification (amalgamation of global social regulation under the control of one vast computer). Papa Jan initially urges the young Chip to try thinking something different in the days just before his monthly treatment, when its effects are at their weakest, and in doing so sets his grandson on a path towards irremediable misfit. The pros and cons of individuality are later clearly articulated by a group of untreated rebels:

And that’s what we are offering you,’ Snowflake says; ‘a way to see more and feel more and do more and enjoy more.’

‘And to be more unhappy; tell him that too. […] There will be days when you will hate us,’ she said, ‘for waking you up and making you not a machine. Machines are at home in the universe; people are aliens.’ (Levin, 1994: 73)

A preoccupation clearly of its time as much as ours, and also vented in H.G. Wells’s depiction of the childlike Eloi in The Time Machine: happy, carefree, semi-moronic creatures, ultimately doomed to extinction (Wells, 1982).

Experiments in futuristic reality follow a much earlier tradition which surprisingly predated these science fiction works by one hundred years and reached extreme expression in E.M. Forster’s ‘The Machine Stops’ (Forster [1909], 2004). A decade earlier, even, than Forster’s short story, Edward Bellamy’s utopian novel of 1888, Looking Backward, tells the story of Julian West, a young American who falls into a deep, hypnosis-induced sleep and wakes up more than a century later. Julian finds himself in the same location, in Boston, but in a totally changed world. It is the year 2000 and, like Washington Irving’s Rip van Winkle, who goes to sleep while America is still one of George III’s colonies and wakes up to discover it is now an independent republic, Julian, too, finds that during his slumber the world has changed in many ways, not least as regards widespread political arrangements. In the year 2000, the US has been transformed into a Socialist utopia. The novel outlines Bellamy’s complex thoughts about how a future world might be improved. In the year 2000, the young protagonist finds a guide, Doctor Leete, who shows him around and explains all the advances of this new age (a convenience consumer culture which includes drastically reduced working hours for people performing menial jobs, and facilities such as instantaneous delivery of goods from stores to homes). Unlike the nightmare scenarios of Brave New World (Huxley, 1977), This Perfect Day (Levin, 1994), The Children of Men (James, 2000), and Oryx and Crake (Atwood, 2004), people do not automatically die when they reach a certain age, merely retire (with full benefits) aged 45. The productive capacity of America is communally owned, goods are equally distributed to all citizens, and, anticipating ‘The Machine Stops’ a decade later, all mod. cons. including classical music and religious sermons are piped into homes through cable telephone. With reference to Bellamy’s work, David Ketterer suggests that ‘the possibility that man has attained a new evolutionary plane, the belief that the characters believe their highly technological world to be a utopia can only realistically imply a dystopian society in which the citizens have evolved, or rather devolved, into machines’ (Ketterer, 1974: 113), with all the consequences that that entails, as discussed in chapter 4. Be that as it may, clearly, in both Irving’s and Bellamy’s narratives, at the heart of these would-be utopias, lies the urge for defining sociopolitical change.

In general, whether utopia is the outcome of a political impetus for change (in the two texts just discussed), a gigantic conspiracy with an ulterior motive (world domination in Brave New World, Huxley, 1977; This Perfect Day, Levin, 1994), the manifestation of a State-instigated defensive strategy (Dr. Bloodmoney, Dick, 2007) or corporate profit (The Truman Show, Weir, 1998), in general what we are left with seem to be largely unsatisfactory and unpersuasive scenarios of existential anaesthesia doomed to ultimate failure.

The Dark Side of Utopia

Under the new regime established in The Children of Men (James, 2000), drastic measures have been taken to pacify citizens and maintain the illusion that a comfortable life will be possible in the years to come. By decree of the Council of England, every citizen is required to learn skills such as farming, which they might need as the last generations of humans gradually die out. Foreign immigration is encouraged for the purposes of hard manual labour, but immigrants are forcibly repatriated at the age of sixty. As is the case in other utopian/dystopian writings, native citizens are not permitted to become a burden to the community by reason of age or infirmity: among the elderly and the sick, the privileged few are put in nursing homes. The rest must choose between unassisted deaths at home, state-assisted suicide, or death through participation in one of the regularly-held ceremonies of Council-sanctioned drownings known as The Quietus. Utopia, the New Jerusalem, can only be set up after the unfit have been eliminated.

And he that sat upon the throne said, […] He that overcometh shall inherit all things; and I will be his God, and he shall be my son.

But the fearful, and unbelieving, and the abominable, and murderers, and whoremongers, and sorcerers, and idolaters, and all liars, shall have their part in the lake which burneth with fire and brimstone: which is the second death. (Revelation, 21: 7)

So it is nice, then, but only for some, and then only for a while. You cannot make an omelette without breaking eggs. The construction of utopia always comes at a price, which from Plato’s ideal Republic and the ruthless John of Patmos in the Book of Revelation to Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (Huxley, 1977), via approaches as disparate as those of the Fabians and the Nazis, involves a lot of clearing up of old detritus prior to the inauguration of paradise. Whether or not the implications of this cleansing involve scenarios of the end of the world, in Judaeo-Christian understanding (fundamentalist predictions of the Rapture, the idea of a Day of Judgment) as well as in much science fiction, utopia usually represents the endpoint of apocalyptic literature. And as David Ketterer argues, such literature is concerned with ‘the ultimate creation of other worlds which exist, on the literal level, in a credible relationship (whether on the basis of rational extrapolation and analogy or of religious belief) with the “real” world, thereby causing a metaphorical destruction of that “real” world’ (Ketterer, 1974: 13).

Not only is utopia, therefore, a relative concept (one size clearly does not fit all, as demonstrated by Montag, Chip, Winston Smith, and Kuno) but, moreover, the process of imagining it whether in myth, culture, science or political thought, always comes with significant caveats: specifically, the prerequisite of the cleansing out of the prevailing status quo, the elimination of elements in it deemed to be undesirable, and the abdication of both free will and the entitlement to choice. The wider complexities of the concept of utopia, therefore, must be considered with particular regard to the common thread linking diverse and sometimes antithetical implications of utopianism’s original political, ethical and ethnographic paradigms.

The Big Spring Clean

As already suggested, utopia, from Plato to the Russian Jewish writer Ayn Rand (via the Aryan Nazi Valhalla whose vision Rand disturbingly mirrors), can only begin after undesirable elements have been eliminated. Plato’s ideal Republic, for example, required the exclusion (by unspecified means) of numerous categories of undesirability (artists, poets, the sick, the ugly and nonconformists, to list but a few).

The move from individual exclusion to death, thence to genocide and from the latter to global annihilation as the ultimate purge, arguably, involves steps which are too small (imperceptible) for comfort. With regard to genocide, H.G. Wells’s vision of utopia in Anticipations, for example, concluded that quality life on Earth could only be preserved by means of the extermination of the entire populations of Africa and Asia (Wells, 1999), and more than fifty years before Hitler’s Final Solution, many distinguished members of the respected Fabian Society (including names such as George Bernard Shaw, whose reputation, like Wells,’ astonishingly, remains unsullied to this day) were strong supporters of eugenics as an instrument of social progress.

Wells, not now in the guise of purveyor of science fiction but in his self-appointed role as philosopher-architect of the future, argued in all seriousness that utopia could become a reality only by means of state regulated and enforced reproduction (‘wifehood [being] the chief feminine profession’ and ‘the efficient mother who can make the best of her children [… being] the most important person in the state,’ Wells, 1999: 174).

Even more drastically, he went on to elaborate the necessity for genocide:

It has become apparent that whole masses of human population are, as a whole, inferior in their claim upon the future to other masses […]. [T]he men of the New Republic will hold that the procreation of children who, by the circumstances of their parentage, must be diseased bodily or mentally […] is absolutely the most loathsome of all conceivable sins. […] And how will the New Republic treat the inferior races? How will it deal with the black? How will it deal with the yellow man? How will it tackle that alleged termite in the woodwork, the Jew? Certainly not as races at all. […] It will tolerate no dark corners where the people of the Abyss may fester […]. And […] those swarms of black, and brown, and dirty-white, and yellow people, who do not come into the new needs of efficiency?

Well, the world is a world, not a charitable institution, and I take it they will have to go. [… I]t is their portion to die out and disappear.

The men of the New Republic will not be squeamish […]. They will have an ideal that will make killing worth the while; like Abraham, they will have the faith to kill. (Wells, 1999: 163-78)

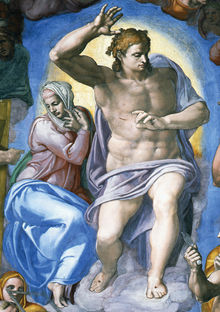

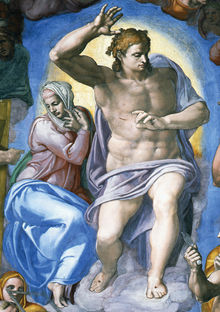

Figure 21. Michelangelo Buonarroti, Christ as Judge of the World

While in his nonfictional polemics, Wells defended the genocidal policies, (outlined above) in some of his novels, including The War in the Air (Wells, [1907] 2005) and A Modern Utopia, he indicates that following a Last War, a new stage in history will be inaugurated leading, in due course, to ‘the dream of a world’s awakening’ (Wells, 2005: 369): not quite like Francis Fukuyama’s end of history, but also not absolutely unlike it, since it, too, envisages a world globally converted to the basic ideology and sociopolitical structures of the West.

Fukuyama’s thesis is at worst foolish, but elsewhere things can get nasty. In Timothy Findley’s Not Wanted on the Voyage (Findley, 1987), a re-writing of the Noah’s Ark episode in Genesis, prior to embarking on a journey that will signal the end of one world and the beginning of another one, the law-abiding Dr. Noyes, in an echo of other final solutions, orders his sons to kill Lotte, a mentally handicapped child. In Not the End of the World (McCaughrean, 2005), a re-writing for children of the same Biblical episode, friends’ and neighbours’ supplications are ignored by Noah who, in his determination to act by the (Lord’s) book, lets them drown. Likewise, in Earth Abides (Stewart, 1973) Christian principles inform the actions of the community patriarch, who, although admittedly with mild regrets (which however are effortlessly overridden by a needs-must certainty), condemns a mentally disabled young woman to death lest she should give birth to similarly damaged offspring. In this enduringly popular novel whose affinity to the logic of Hitler’s Germany is never remarked upon by a loyal public, Evie is eliminated on the breathtakingly level-headed grounds that it would be bad for the community if her defective genes were passed on.

In the end, however, as suggested above, if all else fails, war always remains as a short cut to the implementation of utopia. Which brings us back to where we began this discussion: end-of-century, end-of-millennia, end-of-time cultural mind sets, which, by way of more or less bloody epiphanies, undertake the enterprise of imagining sometimes unwelcome, not-always-so-new beginnings.

Millenarian fear and desire both involve the ability to imagine cataclysm: in the case of the former as a cause, and in the case of the latter, as a means to an end. The logic of a purge prior to a new beginning can be detected in the earnest reasoning of prominent opinion-formers and decision-makers over the centuries, including some of those at present empowered with the means to actually bring it about. The belief in an imminent near-global wipe-out (the necessary first step towards a return of God to Earth for the purpose of the salvation of the deserving happy few) is usually assumed to be the province of a lunatic religious fringe, extremists in far-flung outposts of monotheism, from fundamentalist Christianity to Jihadist Islam. More worryingly, however, a 1984 survey found that 39% of Americans believed that Biblical predictions of global destruction by fire referred to nuclear war (Seed, 2000: 57). And in connection with this, Hal Lindsey’s widely-read The Late Great Planet Earth of 1970 (Seed, 2000: 57) argued that the Christian fundamentalist faithful need not worry about nuclear war because at the relevant moment they will be ‘raised in the air to embark on the ultimate trip’ (Jews and other religious groups need not apply), meet Christ and return with him, in the aftermath of nuclear holocaust, to re-build the New Earth.

Figure 22. El Greco, The Opening of the Fifth Seal of the Apocalypse

Much more worryingly, in the must-read essay pithily entitled ‘Armageddon,’ Gore Vidal describes how the belief in the need for a tabula rasa wipe-out prior to a new beginning was also espoused by such influential voices as James Watt, Ronald Reagan’s Secretary of the Interior, and by Reagan himself, his presidential finger, of course, at all times poised on the nuclear button. Vidal summarizes the rationale whereby, as Watt explained to the American Congress in 1981, the end of the world could be relied upon to happen sooner rather than later (‘I do not know how many future generations we can count on before the Lord returns,’ Vidal, 1989: 192):

Christ will defeat the anti-Christ at Armageddon […]. Just before the battle, the Church will be wafted to Heaven and all the good folks will experience Rapture […]. The wicked will suffer horribly. Then after seven years of burying the dead (presumably there will be survivors), God returns, bringing Peace and Joy, and the Raptured ones. (Vidal, 1989: 103-04)

Gore Vidal knew whereof he spoke: some years earlier, Reagan, then Governor of California, had stated:

All of the other prophecies that had to be fulfilled before Armageddon can come to pass. In the thirty-eighth chapter of Ezequiel it says God will take the children of Israel from among the heathen where they’d been scattered and will gather them again in the promised land. That has finally come about after 2,000 years. For the first time ever, everything is in place for the battle of Armageddon and the Second Coming of Christ. […] Everything is falling into place. It can’t be too long now. Ezequiel says that fire and brimstone will be rained upon the enemies of God’s people. That must mean that they will be destroyed by nuclear weapons… (Reagan quoted in Vidal, 1989: 108-09)

Reagan was the most powerful but also only one of an estimated twenty million Americans who believe in the Rapture, although there is some confusion as to whether the Children of Israel (Jews) are the ones who will be saved or exterminated. In view of the general religious and ethnic likes and dislikes of the proponents of the Rapture, however, extermination is the more likely option, followed by a drastic revision of the term ‘Children of Israel.’ Be that as it may, as far back as 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev was so troubled by the American President’s happy supposition that ‘we may be the generation that sees Armageddon’ (Berger, 1999: 135), that he provided a gentle reminder that ‘planet Earth was the only likely venue for the continuity of humanity and that it would be a pity to lose everything through war, or, more likely, accident.’ (Vidal, 1989: 111)

All as It Ought to Be

The Rapture envisaged by evangelical Christian fundamentalism has a species similarity to the fictional universes achieved after suitable social cleansing or even absolute discarding of the old world/universe in works such as Brave New World (Huxley, 1977) and Tau Zero (Anderson, 2006) respectively. In the resulting utopia, as under the average dictatorship, human difference comes to be regarded as at best an inconvenience and at worst a sickness, treatable, eradicable or genetically modifiable in the name of the preservation of authorized forms of happiness.

‘Heat conditioning,’ said Mr. Foster.

Hot tunnels alternated with cool tunnels. Coolness was wedded to discomfort in the form of hard X-rays. By the time they were decanted the embryos had a horror of cold. They were predestined to emigrate to the tropics, to be miners and acetate silk spinners and steel workers. Later their minds would be made to endorse the judgement of their bodies. ‘We condition them to thrive on heat,’ concluded Mr. Foster. ‘Our colleagues upstairs will teach them to love it.’

‘And that,’ put in the Director sententiously, ‘that is the secret of happiness and virtue – liking what you’ve got to do. All conditioning aims at that: making people like their inescapable social destiny.’ (Huxley, 1977: 31)

The Ideology of Utopia: What Goes Round Comes Round

Aside from the ethical problems raised by any utopia (the need to cull weakness or even mere difference), utopianism has further inbuilt requirements that, however, paradoxically also threaten the very possibility if its existence. In other words, that which must be in place if utopia is to be established is also that which may lead to its undoing. If the basic sine qua non of utopia is conformity and homogeneity (a hatred of difference or of ‘mutants’), a straightforward Darwinian logic dictates that should conditions change, a non-variant status quo may be doomed to extinction.

What if I Say No?

Another obstacle to utopia, which stems from the imperative of homogeneity, is a fundamental characteristic of human nature, namely its contrariness (the urge to differ), the satisfaction of which can be a prerequisite to existential well-being. In Machado de Assis’s short story, ‘The Devil’s Church’ (Assis, 1987), the Devil decides to break God’s theological monopoly and establishes his own church, based on the worst instincts of humanity (greed, envy, selfishness, violence). The corporate take-over fails when a beleaguered Satan comes to realize that after his new faith’s initial success, its long-term survival is threatened by the fact that its members are increasingly guilty of clandestine virtue practiced by stealth. The despondent Wrong-Doer begs an amused God for an explanation and is told that there is none, other than the eternal contradictoriness of human nature (Assis, 1987). This being so, if conformity is an essential component of utopianism, either humanity itself has no place in utopia or the latter is doomed to failure at the hands of its customers. Julian Barnes’s beneficiary of heavenly utopia, in the end asks to be allowed to die (again, and this time with no option of an Afterlife): anything – even death – it would appear, is better than having all one’s wishes fulfilled in perpetuity, because if whatever one asks for the answer is always ‘yes,’ how can one enjoy the bliss of saying ‘no’?

The contemplation of existing versions of utopia often leads to the unpalatable realization that utopias, from Plato’s The Republic to Margaret Atwood’s Gilead, require despotic rule and the uncompromising elimination of dissent. More disturbing even than that fact, for the contemporary speculator, is the possibility that, faced with the choice between unhappiness, war, hunger and social unrest on the one hand, or assenting, obedient contentment on the other (the comfortable living-deaths of the placid members of the herd in Huxley, Bradbury and Levin), one may experience justifiable perplexity. In Ira Levin’s This Perfect Day everyone is good (‘a universe of the gentle, the helpful, the loving, the unselfish,’ Levin, 1994, 305) and life is comfortable. So why not? Why not agree to anything for an easy life? Perhaps John Stuart Mill’s verdict on the relative levels of satisfaction and dissatisfaction in pigs and men was wrong after all. Even if he were right in adding that if either the fool or the pig are of a different opinion it is because they only know their own side of the question, it may be true (albeit disturbing) that in the end it does not matter. Happiness is happiness and misery is misery, and both philosophers and pigs can only begin (but also, we would add now, end) where they find themselves. Might the pig have the better deal after all? We may never know for certain, but we ought to at least consider that possibility.

Philip K. Dick’s predictably eccentric take on this problem in The World Jones Made (Dick, 2003) is set in a post-holocaust world drawing away from the brink of a destruction that originated in a variety of conflicting fundamentalisms. In Machado de Assis, the eternal contradictoriness of human nature was what ultimately obstructed the Devil’s agenda (his pyrrhic victory ultimately amounting to no more than the reduction of God himself to a position of moral relativism). In Jones’s world, the new status quo’s response to destructive fundamentalisms secure of their various monopolies over Truth, is to implement a mandatory kind of pluralism which makes it illegal to proclaim any belief as being right. Ironically, this postmodern paradise of enforced relativism gives rise to a population hungry for clearly identified dictates, even at the price of enforced submissiveness to demagogy. As is the case in Levin, Bradbury, Huxley, Orwell and most of the other works discussed, the most disturbing conclusion – one which carries implications for the life of any community – may be that in the end, the majority of human beings has no use for freedom. (As an illustration of this, it should be noted that the percentage of the electorate that vote in any given election in both the UK and the US at present is at most between 50% and 60%.)

The Luxury of Saying No

If, as Carey would have it, ‘the aim of all utopias [...] is to eliminate real people’ (Carey, 1999: xii), the puzzle still remains as to why bliss, because enforced, artificially induced and/or non-optional, is inevitably worse than freely-willed choice entailing either occasional or omnipresent misery (Socrates vs. the pig). Is it really better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all? Really? Can we truly understand why Julian Barnes’s hero preferred obliteration to perfect bliss? And in any case, isn’t free will in the end the luxury of the fundamentally non-needy? Does the concept carry semantic validity anywhere below the breadline? An answer in the negative to any of these questions, of course, paves the way to demagogy, but the questions, nonetheless, ought to be asked. Life’s a bitch and then you die, or even, according to the Barnesian and Orwellian oxymorons, you die but only if you are extremely lucky. Most utopias approach the question of free will through its negation in exchange for guaranteed stability, and the desirability of the latter is not uncommonly emphasized by preceding periods of acute uncertainty, threat or upheaval. It is in light of the possibility or reality of social disintegration that certainty, even at the price of ruling totalitarianism, becomes the accepted rule. And following the implementation of this rule, the past is, if necessary, re-written, and the future graven in stone (until further notice):

[…] no written record, and no spoken word, ever made mention of any other alignment than the existing one. At this moment, for example, in 1984 (if it was 1984), Oceania was at war with Eurasia and in alliance with Eastasia. In no public or private utterance was it ever admitted that the three powers had at any time been grouped along different lines. Actually, as Winston well knew, it was only four years since Oceania had been at war with Eastasia. But that was merely a piece of furtive knowledge which he happened to possess because his memory was not satisfactorily under control. Officially the change of partners had never happened. (Orwell, 1983: 34)