5. Women and the Visual Arts

Rosalind P. Blakesley

In 1800, the French artist Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, then resident in St Petersburg, was elected an honourary free associate of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. The first woman painter to be honoured in this way, the artist responded by painting what she later considered to be the best of her many self-portraits and presented it to the Academy, where it hung in the Council Chamber until 1922 (Fig.1).1 Vigée-Lebrun depicted herself at work on a portrait of Empress Maria Fedorovna, who was not only consort of the Emperor of all the Russias, but also an artist in her own right. Conveniently marking the start of the period under consideration in this book, the painting could be construed as testament to the achievement of women artists in Russia at the time, as Vigée-Lebrun celebrates acceptance into the bastion of the Russian artistic establishment by depicting herself carrying out a prestigious Imperial portrait of another woman artist. The painting’s composition could be seen to enforce this multi-layered reading of female artistic agency. The planar structure, in which the outline of Maria Fedorovna hovers above the shadow which Vigée-Lebrun casts on the canvas, might be read as a metaphor for the established, professional woman artist both standing apart from, and buttressed by, amateur practice. At the same time, the way in which both sitters look directly at the (female) artist who painted them sets up a dialogic encounter between women, which subverts the more familiar objectification of female subjects for a male gaze.

Fig. 1 Marie Louise Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Self-portrait (1800) The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

Yet any inference from Vigée-Lebrun’s painting that women artists were an established part of the cultural fabric of Russia would be misleading. With the exception of the occasional acclaimed foreigner or woman of Imperial status, female practitioners of painting, sculpture, or architecture were practically invisible in Russia at the time. Denied access to the formal artistic education provided by the Academy as well as to any official routes of exhibiting and selling their work, they tended to produce amateur work in media such as watercolour and pastel which was enjoyed in the domestic rather than the public sphere. The same was true of music and theatre, where women tended to focus on those forms of song, instrumental works, or amateur dramatics suitable for performance in the home, as Philip Bullock and Julie Cassiday explore in their chapters here. As far as the upper classes are concerned, it would be simplistic to draw too clear a correlation between gender and amateurism, as throughout the first half of the nineteenth century painting and drawing, like literature, were practised by noblemen as much as by noblewomen almost exclusively as dilettantes, as professional work was deemed beneath them. Nonetheless, recognition for female artistic achievement outside the home was negligible. Even Vigée-Lebrun, a portraitist of international repute, was given only an honorific title by the Academy, as the formal rank of Academician, which would have been appropriate to her status and experience, was not granted to women at the time.

By 1917, however, women were not only practising as professional artists, but, in the likes of Natal’ia Goncharova, Ol’ga Rozanova and Liubov’ Popova, constituted a powerhouse within the Russian avant-garde. Research on Russian women artists has focused understandably on these and other women who emerged in the final decades of Imperial rule and played a vital role in the formal innovation and move towards abstraction for which the avant-garde is famed. Indeed, if Russian art historians have been relatively slow to engage critically with the nature of women’s artistic production in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, they have come into their own in their scholarship of the avant-garde. It is important, nonetheless, to consider the earlier period of relative inactivity as much as the high-profile artists at the dawn of the twentieth century, as charting the transition of women artists in Russia from marginal figures to world-renowned practitioners raises significant questions about the role of women in Russia’s creative and cultural life. In this chapter the balance is deliberately weighted in favour of the nineteenth century, whose women artists have suffered from relative scholarly neglect, though the iconic artists of the pre-revolutionary period receive due mention.2 A recurrent theme is the relationship between painting and the applied arts – an opposition which has been fundamental to feminist art history in general, as women were long excluded from the institutions which taught and supported the fine arts, but excelled in applied arts and crafts. As Alison Hilton noted in her seminal essay of 1996, this issue acquires especial resonance in Russia where the change in status of women artists from an outsider minority to a central force was closely linked to their activity in the applied and decorative arts, as these foreshadowed the move in the revolutionary period to integrate art into everyday life.3 Much Western scholarship has accordingly been driven by the desire to rehabilitate areas of art and design in which Russian women flourished, rather than labouring a male standard in the ‘higher’ arts against which women artists are found wanting. Taking its cue from such concerns, this account charts shifting tensions between the categories of fine and applied arts in order to shed light on certain habits of mind which have influenced the production, consumption, and interpretation of Russian women’s art.

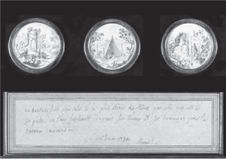

Maria Fedorovna (1759–1828), Vigée-Lebrun’s subject in her self-portrait, offers an interesting starting point. Born and educated in Germany as Princess Sophia Dorothea Augusta Luisa of Württemberg, she took the name Maria Fedorovna on her conversion to the Russian Orthodox faith, and moved to Russia after her marriage to Grand Duke Paul (later Paul I) in September 1776. There, she became a stylish and influential patron of the fine and decorative arts at Pavlovsk, the palace which Catherine the Great had commissioned for Paul and his wife in 1781, as well as an accomplished artist in many different media. If her early work involved the sort of still-life painting in pastels which was customary of many aristocratic women, Maria Fedorovna soon went beyond the subjects and techniques expected of her sex, securing tuition with an Academy professor (the German medallist and engraver Karl Leberecht) and acquiring her own lathe in order to fashion cameos, medals, engravings, and decorative objects in ivory, amber, and other semi-precious stones.4 Particularly thought-provoking are a set of drawings of architectural monuments at Pavlovsk and Tsarskoe Selo which Maria Fedorovna mounted onto buttons in 1790, and presented in a frame to Catherine the Great (Figs. 2 and 3). There is an intriguing dialectic at play here between different art forms and their gendered associations. Architecture, represented by various follies and temples in a classical Greek style, was an historically male preserve. (That depicted here was largely the work of Charles Cameron, the Scottish architect employed by the Empress at Tsarskoe Selo and subsequently commissioned to design the palace and many of the garden structures at Pavlovsk.) Its figuration in drawing – an acknowledged and respected component of the fine arts – was the work of another man, as Maria Fedorovna’s drawings are copies of originals by the miniaturist François Viollier. In copying one man’s drawings of another man’s architecture, Maria Fedorovna’s work might thus seem derivative, with an inferred deference to the greater originality and artistic prowess of men. Yet she uses her sources to create an entirely new artistic artefact in the form of the buttons which, as part of costume and dress as well as an applied art, speak to interests and pursuits typically associated with women. A process of gradual transformation is under way, negotiating a visual journey from the masculine connotations of the architecture to a highly inventive, feminine art form.

Fig. 2 Grand Duchess Maria Fedorovna, three Imperial buttons comprised of drawings in graphite on vellum of architectural features in the gardens of Pavlovsk Palace and Tsarskoe Selo, mounted in gold frames with rims chased in a laurel leaf design. Part of a set of twenty-two buttons placed in a gilded wooden frame with a hand-written dedicatory inscription and presented to Catherine the Great (1790). Lot no. 424, The Russian Sale,

Sotheby’s, London, 1 December 2004.

Such visual playfulness apart, the buttons have an important documentary function, as they provide a rare record of the appearance of Pavlovsk before a fire devastated the palace in 1803. They also offer an insight into the dynamic between Maria Fedorovna and her mother-in-law, not least in the inscription which they bear: ‘Ces boutons sont presentés à la plus chérie des Mères par celle qui est à ses pieds en vous suppliant d’agreér ses Voeux et ses hommages pour la journée d’aujourd’hui. Le 25, Juin 1790 Marie F.I’.5 Relations between the two women were far from easy: Paul was openly antagonistic towards his mother and Catherine tested Maria Fedorovna’s forbearance to an extreme when she took the couple’s two oldest sons, Alexander and Konstantin, away from their mother to be raised under the Empress’s own supervision. Maria Fedorovna, nevertheless, regularly presented her mother-in-law with examples of her artistic work, especially that which depicted subjects close to the Empress’s heart, such as cameos and silhouettes of family members, or – as with the buttons – the landscape architecture of Catherine’s estates. Such gifts were often accompanied by respectful and affectionate texts. In keeping with contemporary notions of the importance of women as nurturers and peace-makers within the home – values which had been strongly impressed on Maria Fedorovna during her childhood and upbringing in Germany, and which in Russia were enforced by the clergy at times, as Vera Shevzov shows in her essay here – the Grand Duchess thus used her creative work as a form of diplomatic offering to foster good familial relations within the Imperial court. Certainly, her artistic endeavour in no way transgressed any norms of social behaviour, but instead sat comfortably with the conservative family values which Maria Fedorovna upheld.

Along with her daughters and the offspring of certain academic professors, Maria Fedorovna was one of only a handful of women receiving tuition from members of the Academy of Arts at the time – a privilege which reflected her status as wife of the heir to the Russian throne.6 Other than drawing lessons in the few existing educational institutions for girls, or tuition under private art tutors in wealthy households, there was little formal artistic training available to Russian women. However, students at the Smol’nyi Institute for Young Ladies of the Nobility, which Catherine the Great had established in 1764, were taught painting, drawing, how to work with clay and the craft of turning on a lathe in which Maria Fedorovna excelled (these alongside other prized female accomplishments such as music which were ‘designed to improve the marriage prospects of girls from the nobility and gentry’, to quote from Bullock’s chapter).7 From the final quarter of the eighteenth century, although they were unable to study there, women were also able to submit examples of their work to the Academy, which might respond by awarding an official title, a medal, or dispensation to pursue related professional work. In 1796, Maria Fedorovna’s daughters Elena and Aleksandra, who studied under the renowned portraitist Orest Kiprensky, each presented the Academy with a wax profile portrait in relief depicting, respectively, Peter the Great and Catherine the Great as Minerva.8 Marking the annual celebration of Catherine’s accession to the Russian throne, these works were an act of homage to the Empress rather than a quest for official recognition from the Academy: the celebration records noted Catherine’s delight at being depicted as Minerva and as Peter’s successor by her granddaughters, who were only eleven and twelve years old at the time.9 But other women, professors’ daughters among them, were granted the right to teach on the basis of works submitted to the Academy and in 1812, Marfa Dovgaleva became the first woman known to be awarded an Academy medal, winning a second-class silver medal for her proficiency in engraving.10 (Such was the importance of academic recognition that in 1869, Pelageia Zhukova petitioned the Academy for a copy of the certificate confirming her right to teach after the original was lost in a house fire.)11 Little of these women’s work survives, and the brief mention in Academy records of their submissions is often all we know of their careers. Even A. M. Bakunina, who in 1835 became the first Russian woman artist to be sponsored to travel abroad (in her case as a scholar of the Imperial Society for the Encouragement of the Arts), disappeared almost without trace. If they pursued a career in the visual arts at all, most women worked as art tutors for children in aristocratic households. Academic recognition certainly gave no guarantee of future success, as the case of Mariia Kurt, the wife of a St Petersburg merchant, attests. In 1839, Kurt was made an Unclassed Artist (the lowest of various titles which the Academy awarded at the time) and was firmly set on an artistic career, writing to the Academy: ‘having studied painting for ages, all my aspirations are focused on attracting the attention of the public and, sooner or later, counting myself among the profession of Russian artists’. Yet twenty-six years later, by which time she was in her mid-seventies, Kurt was still supplicating the Academy for financial aid, suggesting that her hopes of earning a living as a professional artist had not been realized.12

Fig. 4 Ekaterina Khilkova, The Interior of the Women’s Department of the St Petersburg Drawing School for Auditors (1855). State Russian Museum,

St Petersburg.

Fig. 5 Christina Robertson, Portrait of Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna (1841). The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

The 1840s, however, witnessed a turning point in the artistic education of women in Russia. A growing number began to frequent the Academy in the capacity of ‘free attendants’ (vol’noprikhodiashchie), who were excluded from official competitions and exams, but could win medals and awards.13 A few women also attended the few small art schools which were appearing in the provinces, though they tended to be related to the men running these schools.14 More formally, in 1843 the Stroganov School of Drawing in Moscow opened a drawing section for women, complementing the teacher training and instruction in the applied arts that it already provided; and the St Petersburg Drawing School for Auditors, founded by the Society for the Encouragement of the Arts in 1840, established a separate women’s department in 1842. This facility offered the most comprehensive, officially-sanctioned artistic training for women in Russia to date, though it still lagged well behind developments in France, where the state-funded Ecole Nationale de Dessin pour les Jeunes Filles had been founded in 1803.15 In a report to Nicholas I of May 1842, the Minister of Finance Count Egor Kankrin argued that the initiative at the Drawing School for Auditors would be of use in training women ‘not only to be self-sufficient workers, but also, in their capacity as wives and mothers, to be future helpers and educators of men’.16 Such views sat well with the tsar’s own views on women’s education at the time, and he appointed his daughter, Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna, as the department’s first patroness. Girls could enrol from the age of twelve, but had to be accompanied from the age of fourteen until such time as they married, whereupon they could come once more on their own. Classes took place twice a week and largely followed the same programme as that set for male students, with the exception of ‘technical drawing’, which was not deemed appropriate for women. Conversely, female students studied ‘landscape drawing’ which was forbidden the men, on the grounds that the relative ease of the exercise could lead them to ‘inaccuracies and superficial drawing’. Girls and women from the upper classes were freely admitted, while those of lower social status had to acquire special permission to take part. When the department opened on 24 September 1842, fourteen women had enrolled, comprising the daughters of a nobleman, three civil servants, two townsfolk (meshchane), two army captains and one colonel, an archpriest, a doctor, a court servant, a coppersmith and a ploughman. By December that year the number had swollen to forty and by 1846 there were 169 attenders, of whom 112 came from the nobility and 28 from the merchant class (this preponderance of students from the upper classes setting the pattern for many years). The following year women featured on the list of the school’s prize winners for the first time. Teaching faculty later included figures as renowned as Ivan Kramskoi, the Realist painter who spearheaded the famous student revolt against the Academy in 1863 and set up an independent commune of artists known as the Artel khudozhnikov. (Significantly, women were welcome at the social and artistic gatherings which took place every Thursday at the Artel.)17 Such instruction was solid enough to launch many women on careers as drawing teachers, just as the conservatoires were to produce a large number of female music teachers in later years (see chapter six).

Ekaterina Khilkova’s painting of 1855 provides a vital visual record of activities in the women’s department at the St Petersburg Drawing School for Auditors, just over a decade after classes began (Fig. 4). With the exception of one man on the far left, whose role is unclear, all of the figures in Khilkova’s painting are female and women, in fact, provided instruction as well as attending as students (Khilkova herself worked as a drawing teacher there for a while, as well as in other women’s educational institutes). There are also indications of a pedagogic methodology that revolved around two distinct teaching models: study lithographs (then a popular form of instruction), which are pinned to the walls and displayed above the desks; and classical models in the form of the different orders of column capital arranged along the far wall and the cast of the celebrated antique statue Laocöon glimpsed through the open door. It is clear that students were encouraged to draw from these models to acquaint themselves with their formal properties and expressive language, as a copy of one of the lithographs lies on a desk to the right and a seated figure on a stool in the end room appears to be sketching the Laocöon. Another woman in the foreground, flanked by two others, seems to be drawing either an image of, or an actual bas-relief of, a decorative motif, but the applied arts are otherwise absent from Khilkova’s painting. It may be that these were taught in another room, and the vignette with the bas-relief was included here as a token of the curriculum’s inclusion of the applied and decorative arts. There is no sense, however, that the students’ energies were directed towards the sort of craftwork deemed appropriate for women. On the contrary, the focus on the study of the human head, and on classical models, suggests a clear ambition to master some of the more demanding skills required of a successful draughtsman or painter.

Khilkova’s image is carefully constructed, with good knowledge of the rules of perspective (the striped carpet on the left rather crudely emphasizing this), and the confident placement of figures in an interior setting. The rendition of the different materials of the women’s outfits is also convincing, from the silken texture of the skirts, to the lace of the collars and the diaphanous white blouse in the centre. One might, nevertheless, perceive limitations to her work in the similarity of the facial expressions and postures; in the polished but unadventurous use of paint; and in the lack of excitement to the composition as a whole. Here, though, the feminist art historian would caution against linking qualitative evaluations to gender on the basis of visual evidence in one painting alone. Is Khilkova’s work really inferior to that of her male peers, or simply typical of the vast majority of Russian interior painting at the time? Similar questions might be asked of Sof’ia Sukhovo-Kobylina (1825–67), who in 1854 overcame the obstacles posed by both her gender and her higher social class to become the first woman to win the Academy’s top award of a gold medal (an event which she chose to commemorate on canvas) and subsequently set up a fashionable studio in Rome.18 The few surviving landscape paintings for which Sukhovo-Kobylina was feted may show little innovation in terms of technique or style, but was not the same true for most contemporary male landscape artists?19 In other words, the very ordinariness of the paintings of Khilkova and Sukhovo-Kobylina (both of which won academic medals) can serve as an index of their achievement in meeting the expectations of the artistic establishment at the time. Among women, only Christina Robertson (1799–1854), a Scottish artist who worked in St Petersburg from 1839 to 1841 and again in the late 1840s, stood out for her parade portraits of Russia’s aristocratic elite for which she became one of the highest paid portraitists in the Russian capital. The subject of extensive research by Elizaveta Renne, Robertson specialized in full-length state portraits of Imperial women (Fig. 5), in which the evocative brushwork of the outfits, the suggestiveness of the poses and the combination of grandiose architecture and intimate detail, established Robertson’s success in her chosen genre. (Robertson became only the second woman painter, after Vigée-Lebrun, to be elected an honorary free associate of the Academy of Arts in 1841.)20 Otherwise, Russian women’s contribution to the fine arts until the mid-nineteenth century (which largely entailed painting alone, as women’s work in sculpture or architecture was practically unheard of) is noteworthy for the circumstances of the producer and for its typicality, rather than for any marked originality or aesthetic impact which set it apart.21

From the late 1850s a different picture began to emerge. In 1857 and 1858, Natal’ia Makukhina and Julie Hagen-Schwarz (1824–1902) were elected Academicians of Portrait Painting, the title which had been unavailable to Vigée-Lebrun half a century before. Hagen-Schwarz, the daughter of a German Balt artist, seems to have enjoyed particular success in official circles, winning a three-year foreign scholarship from the Cabinet of His Imperial Highness in 1853, despite already being resident in Rome and having spent much of her career to date living and studying in Western Europe.22 A rare extant work is Young Italian with Pistol in Hand of 1851–54 (State Tret’iakov Gallery, Moscow), which forms part of a group of paintings produced by mainly academically-trained artists from various European countries who studied or worked in Italy in the first half of the nineteenth century. There, they were inspired by the strong Italian light and by the different customs that they encountered to produce local portraits and scenes of everyday life in a distinct style, which became known as the ‘Italian genre’. Highly popular with Russian artists after Karl Briullov’s excursions in the genre in the 1830s, the Italian genre was characterized by an emphasis on regional character and by strong tonal contrasts, both of which are manifest in Hagen-Schwarz’s painting. There is a particularly strong affinity between her work and that of Vasilii Shternberg, such as Card-playing in a Neapolitan Hostelry (1840s, State Tret’iakov Gallery, Moscow), notably in the attention to costume and facial hair and in the pronounced chiaroscuro.23 That Hagen-Schwarz produced her painting after the heyday of the Italian genre suggests that her work was relatively conservative. However, her canvas does not comfortably meet either the ‘lyrical’ or the ‘festive’ categories into which a recent scholar has divided the Italian genre.24 Rather, it evinces a moody, menacing air in keeping with the critical realism that was emerging among Russian artists of the 1850s and 1860s, placing Hagen-Schwarz’s work in the interstices between two very different approaches to genre painting at the time.

Judging from her correspondence, Hagen-Schwarz later produced over five hundred portraits, between 1872 and 1898.25 These are almost all now lost, which may suggest that they were of little aesthetic interest, though it might equally illustrate the struggle which women still faced to have their work appreciated and preserved. Their access to artistic training in the school system certainly remained firmly gendered, as the Ministry of Education’s statute on women’s gymnasiums and progymnasiums of 1870 reveals: the only compulsory subject with any reference to the visual arts was ‘needlework essential for practical application in the home’, while drawing was offered as an elective subject.26 The final three decades of the nineteenth century, nevertheless, marked a period of increasing opportunity, activity and recognition for women artists in Russia. In 1868 Mariia Ivanova-Raevskaia (1842–1912), a recipient of the title of Unclassed Artist, set up a school of drawing and painting in Kharkov, Ukraine, whose students were soon winning special mentions and medals for the works that they submitted to the Academy’s exhibitions.27 Ivanova-Raevskaia deviated from orthodox teaching methods by encouraging her pupils to study drawing and painting simultaneously (rather than mastering the skill of drawing before working in paint, as was normal academic practice) and by prioritizing the study of anatomy: her application to the Academy for material assistance in opening the school requested not the drawings and studies for students to copy, which were standard fare at the time, but a skeleton and a skull.28 Such an approach raised no hackles at the Academy, which elected Ivanova-Raevskaia an honorary free associate in recognition of her teaching activities in 1872. By then, the status of women within the Academy was subject to intense debate, and the Academy finally agreed to admit women as full-time, fully-registered students in 1873.29 The Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture followed suit, admitting growing numbers of women both as full-time students and as auditors from the 1870s onwards.30

The path of women students at the Academy was far from smooth, as I have discussed elsewhere.31 While initially taught alongside male students, from 1876 they were segregated into women-only classes, which provided a more limited curriculum than that available to the men. Further restrictions were imposed in 1884, when the number of women permitted to study in the Academy in any one year was limited to fifty, of whom only twenty-five could be registered as full-time students, the other twenty-five attending as auditors, without being formally registered or taking official examinations. Such developments mirror those in women’s education more widely in late nineteenth-century Russia, in which initial decisions in favour of women’s access to tertiary education or vocational training were later tempered or rescinded, particularly after the clampdown on institutes of higher learning which followed the assassination of Alexander II in 1881.32

Yet regardless of such limitations, by the end of the century women were increasingly prominent in both numbers and achievement at the Academy. They found a valuable champion in Il’ia Repin, the great Realist artist who welcomed women into his studio at the Academy as soon as he began to teach there in 1894. Particularly significant is that Repin allowed women to work from female models alongside men, as photographs and paintings of sessions in his studio in the 1890s confirm.33 This countered the almost complete exclusion of women from the genre of the nude life-study, which was a practice deeply embedded in the high-art establishment. (In America, such was the strength of feeling surrounding female contemplation of the naked body that Thomas Eakins was forced to resign as head of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1886 after exposing women students to a nude male model.) Graduates of Repin’s studio included Ol’ga Della-Vos-Kardovskaia (1875–1952), whose Portrait of Anna Akhmatova conveys a compelling sense of introspection in the poet’s arresting profile; and Elizaveta Zvantseva (1864–1921), who set up an art school in Moscow and, later, St Petersburg, which numbered Valentin Serov, Lev Bakst, and Kuz’ma Petrov-Vodkin among its teachers and Ol’ga Rozanova among its pupils. Like Repin, Zvantseva also employed female nude models in the life classes held at her school. The same period produced Russia’s first great woman sculptor, Anna Golubkina (1864–1927), who, following a stint as Rodin’s assistant in Paris, won commissions as high-profile as a bas-relief for the façade of the Moscow Art Theatre.34 Entire articles on women artists began to appear in the Russian press. High-born women in the capital city set up the First Ladies’ Art Circle (1882–1917) and the St Petersburg Society for the Encouragement of Female Artistic and Craft Work (1892–1914), both of which supported women artists by organizing practical studio sessions, exhibitions, trading outlets and social gatherings at which lectures, tableaux vivants and musical or theatrical performances would take place.35 These initiatives had a central philanthropic purpose to raise money for struggling artists and their families, the beneficiaries of which included none other than Mikhail Zoshchenko, the writer who later acquired unrivalled popularity for his satirical observation of the incongruities of modern Soviet life.

These various developments in Russia set up an interesting comparison with practices elsewhere. In France, women – though usually rich women – had been admitted to some professional studios from the 1830s and were able to study nude models in a few ateliers from the late 1860s and at the Académie Julian (the famous commercial art school established in Paris in 1868) from 1873.36 Social conventions persuaded Rodolphe Julian to set up separate studios for women at the Académie Julian, as had been the case at the Russian Academy, but women in his establishment continued to enjoy similar training to that offered to the men.37 In contrast, the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris (France’s main, state-sponsored school of fine arts which dated from the seventeenth century) did not admit women until 1897. In England, a Government School of Art for Females had been established in 1859 and women were permitted to attend the Royal Academy from the 1860s, but their exclusion there from life-drawing classes barred their progress in any form of narrative painting (those life models that they were finally allowed to study in the 1890s were carefully draped) and mixed classes were not established until 1903.38 The Academy in St Petersburg, then, was far from reactionary, as concerns official artistic education for women, compared to its better-known European counterparts. On the contrary, in admitting women almost a quarter of a century before its august French predecessor and allowing mixed classes (albeit intermittently), it was arguably at the forefront of state provision in women’s fine art education.

The burning question is whether we should construe women’s acceptance into the Academy as a victory; for by the time they were admitted the institution was in disarray. Shaken by the Revolt of the Fourteen in 1863, when fourteen students had left their alma mater in protest of the limitations of its medal competitions, the Academy had been further undermined by the Society of Travelling Art Exhibitions whose members, the Peredvizhniki, developed a popular Realist style. As they finally achieved full acceptance at the Academy, women were thus gaining access to an institution which was widely seen as moribund and retrograde (an irony which, as Germaine Greer has observed, was equally the case in France).39 In Russia, the proximity of the dates of the formation of the Society of Travelling Art Exhibitions (1870) and the admission of women to the Academy (1873) is particularly conspicuous. Did the Academy vote to include women precisely (if tacitly) as part of their strategy to counteract the success of the Society, which did not admit a woman artist, Emiliia Shanks, until 1894? (Shanks, who had exhibited with the Society since 1891, was a popular candidate, winning one more vote in the election of members that year than the acclaimed artist Valentin Serov – fifteen, to Serov’s fourteen). 40 In the absence of firm evidence, we can only hypothesize on the Academy’s motives, but the acceptance of women would have helped maintain healthy application and admission figures during the first flush of the Peredvizhnikis success. Moreover, the supposition that the Academy may have been actively courting women is supported by the minutes of a council meeting of 1876, which noted that the number of female applicants would increase ‘once they find out that a separate section of women’s classes has been established’.41 As for the women themselves, we are largely ignorant of their awareness of and response to the Academy’s fluctuating reputation. It is nonetheless telling that, despite changes in academic policy and approach, which ranged from the inclusion of women to far-reaching reforms in 1893, many women still elected to study in private studios abroad.42 Perhaps those with neither the money, nor the opportunity to travel, chose to hold their counsel, for the Academy remained the only place in Russia where they could acquire an official and comprehensive education in the fine arts.43

If the relative benefits of the fine art training offered to women by the Academy are up for debate, women’s practice in the applied and decorative arts in the final quarter of the nineteenth century was thriving. Spearheaded by Alison Hilton, Wendy Salmond and other scholars in the United States, such work has become the subject of outstanding research in recent years.44 Particularly remarkable were the female patrons and artists, many of aristocratic background, who set up and managed ambitious initiatives to revive the cottage handicraft activities that in Russia are known as kustar crafts. This kustar production, which ranged from objects as practical as ploughs and nails, to traditionally feminine handicrafts such as lace-making and weaving, formed a vital part of the peasant economy. Under pressure from Russia’s rapid industrialization (see chapter two) and the migration to the cities and cheap factory goods which resulted, however, the kustar industries were in serious danger of decline. Galvanized by the threat to the peasant craft heritage which such a situation presented, women in cities and more distant provinces opened workshops to revive and nurture traditional craft skills. Most famous are the activities at the estates of Abramtsevo, near Moscow and Talashkino, near Smolensk, which have been explored in depth. Yet there is a welcome new focus on little-studied aspects of women’s work at these communities, such as the vibrant personal enamelling practice of Mariia Tenisheva, the patron and chatelaine at Talashkino.45 Wendy Salmond has also brought critical attention to lesser-known enterprises, such as the embroidery workshops which operated in the village of Solomenko in Tambov Province from 1891–1917.46 In providing training and employment and simultaneously encouraging high-quality handicraft, these and other workshops created an important intersection between artistic endeavour and social work.

The most influential woman associated with the kustar revival was Elena Polenova (1850–98), who had studied in the women’s department at the St Petersburg Drawing School for Auditors (under Kramskoi from 1864 and again in the late 1870s) and directed the workshops at Abramtsevo from 1885. Inspired by vernacular architecture and peasant artefacts, which she collected for a museum on the estate, Polenova formulated designs for carved and painted furniture and decorative objects which would appeal to modern aesthetic sensibilities. Realized by local men and boys in the woodwork and joinery workshops, these found a ready market in Moscow and beyond and played a major role in the commercial viability of the Abramtsevo project. Frustrated by the lack of time for personal creative exploration, however, Polenova left the workshops in 1893 to focus on her own work, primarily in the fields of embroidery (she contributed designs to the Solomenko workshops) and graphic design. Highly articulate about her need to be a working, earning artist and about professionalism in the visual arts in general, Polenova was vocal in her frustration at the difficulties in getting exhibited with the Peredvizhniki.47 At the end of the century, however, her work in many media featured prominently in the exhibitions of the World of Art group and its associated journal, which dedicated a lengthy article to the artist and held a retrospective after Polenova’s untimely death from a brain tumour in 1898.48 In her monograph of 1952, Elena Sakharova anticipated by half a century the current enthusiasm for Polenova’s work.49 Indeed, Polenova is now acclaimed as a major force in Russian modernism for the variety of her creative experience, the brilliance of her sense of pattern and rhythm in illustrations and other graphic work, the inventiveness of her visual interpretation of folktales, as well as her stylized plant and animal motifs and the wide application of her designs.50

Polenova was far from the only woman to make an impact with the World of Art group. On the contrary, it is with the advent of this famous galaxy of artists that coalesced around Sergei Diaghilev in fin-de-siècle Russia that women began to constitute a critical mass in the vanguard of Russian art. Mariia Vasil’evna Iakunchikova (1870–1902: not to be confused with her relation by marriage, Mariia Fedorovna Iakunchikova, who ran the Solomenko workshops) shared Polenova’s mental and creative flexibility, working in media ranging from painting, embroidery and poker-work to book and toy design and orchestrating the celebrated Russian handicraft section at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900.51 Zinaida Serebriakova (1884–1967) probed gender stereotypes in her intimate self-portraits, in which the artist traces a fluctuating binary of artist/model and mother/wife by depicting the rituals of self-adornment and domestication that can weave through a woman’s life.52 Particularly notable is the contribution of women to printmaking and book design, in which the likes of Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva (1871–1955) and Elizaveta Kruglikova (1865–1942) excelled. Both women played a critical role in the transformation of printmaking from a technique largely appreciated for its reproductive qualities, to an autonomous art form esteemed for its own expressive potential and aesthetic peculiarities. These and other areas of graphic design figured among the most fertile fields of artistic exploration at the turn of the century and were seized on and pushed in ever more innovative and daring directions by members of the avant-garde. Indeed, the flair for pattern and structure, the stylized, linear approach and the flat use of colour, which characterized the best graphic design of the period, spilt over into other areas of women’s artistic endeavour. Suffice to mention Natal’ia Goncharova’s costume designs for the Ballets Russes, Aleksandra Ekster’s sets and costumes for theatre and film and the textile designs by Varvara Stepanova and Liubov’ Popova, as well as the ground-breaking non-objective painting for which all four women are famed.53 Indeed, the only sphere of the visual arts in which women did not make a critical contribution at this time was architecture, a subject unavailable to them until the Women’s Polytechnical Courses opened in 1906 and the Academy finally admitted women to its architecture department in 1908.54

The reception afforded to women artists in early twentieth-century Russia was mixed. At an extreme, Goncharova was put on trial for obscenity in 1910 after exhibiting paintings of female nudes – an event which, in Jane Sharp’s brilliant analysis, illustrates an attempt by the courts to discipline a woman for venturing into a genre of painting that was the exclusive domain of men. For Sharp, ‘Goncharova’s identity as a woman and as a producer of images of female nudity was seen as contradictory, and her behaviour therefore as criminally “sexed”’.55

Other commentators were openly enthusiastic, but even they struggled to reconcile the strength and novelty of the women’s output with their gender and resorted to investing the women with ‘masculine’ traits. Thus, Iakov Tugendkhol’d wrote of Goncharova: ‘Her personality, as strange as it seems, is more masculine than feminine. […] The basic characteristic of Goncharova’s talent is her masculine, sharp, energetic expressivity. […] In essence, her analytic abilities dominate her gift for synthesis; her masculine eye dominates over her feminine lyricism’.56 Konstantin Somov, a stalwart of the World of Art group, shared Tugendkhol’d’s belief that powerful, visual expression and the fact of being female were largely incompatible, writing of Iakunchikova in 1902: ‘She is now an interesting artist, which is a great exception for women. She draws well, has a fine feeling for colour which is assez personelle. Her technique is masculine’.57 As Helena Goscilo and Elena Kornetchuk, authors of one of the more penetrating articles on contemporary Russian women’s art, observe: ‘then, as now, “masculine” operated as the standard Russian code word for excellence, so the statement intended a compliment, however backhanded and condescending’.58 Notions of originality were so firmly gendered that the only way these commentators could accommodate forceful innovation in a woman artist was by equating her to a man.

In contrast, and thanks in no small part to the momentum of feminist art history, the final three decades of the twentieth century witnessed a surge of interest in the women of the Russian avant-garde – a development which owes as much to books, exhibitions, and reference works on women artists as it does to Russian studies.59 The 1990s marked a particular watershed, starting with Miuda Yablonskaya’s Women Artists of Russia’s New Age, 1900–1935 of 1990 and culminating (at least in terms of international exposure and publicity) with Amazons of the Avant-Garde, the large travelling exhibition dedicated to Ekster, Goncharova, Popova, Rozanova, Stepanova and Nadezhda Udal’tsova, which the Guggenheim Museum, New York, organized in 1999/2000.60 Grappling with the issue as to why these artists achieved the heights of artistic expression and influence which they did, John E. Bowlt argued in the exhibition catalogue that we cannot use the linguistic trope of repression and submission common to discourses on women’s art elsewhere, as the Russian ‘amazons’ enjoyed freedoms in their personal, creative and social lives which were unknown in the West. This is not to deny the practical obstacles and critical aggression which they faced (Bowlt himself mentions the reviewer of Goncharova’s 1913 retrospective for whom ‘the most disgusting thing is that the artist is a woman’.)61 But women in Russia’s pre-revolutionary avant-garde benefited from the relative absence of gendered, professional jealousy in their immediate milieu; from supportive creative partnerships which did not subordinate the work of the woman to that of the man, as was – and is – often the case; and from the availability of spaces of experimentation in the form of studios, theatres, exhibitions, performances, installations and street events. Their extraordinary creative energy was thus bolstered by places and systems of support, both practical and emotional, which had been long denied their sex. That Amazons of the Avant-Garde focused on studio painting to the exclusion of these artists’ formidable output in applied art and design, nevertheless, perpetuated those hierarchical distinctions which have militated against female artistic recognition. Indeed, the exhibition’s remit stands as a stark reminder of where our values still lie.

The twenty-first century looks set to continue to interrogate the distinctive nature, production and context of Russian women’s art. In 2002, the State Russian Museum in St Petersburg held a vast retrospective of Goncharova’s oeuvre,62 and the same year the State Tret’iakov Gallery in Moscow held the first exhibition in Russia dedicated to the work of women artists from the fifteenth to the twentieth centuries. The Tret’iakov exhibition made significant inroads in the quest to recover the work of neglected women painters of the nineteenth century, though its decision to concentrate on ‘visual art proper, i.e. painting, sculpture and graphics, avoiding a wide area of feminine creation – decorative applied art’ again ratified the age-old hierarchy between the fine and the ‘lesser’ arts (though, paradoxically, the exhibition included an entire section on fine needlework in ancient Russia).63 In the West, women artists were integral to the 2002 exhibition on The Russian Avant-Garde Book 1910–1934 at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, which reiterated the significance of this non-fine-art medium in modern art. Three years later, Jane Sharp set a new benchmark in the critique of Russian women artists in Russian Modernism between East and West: Natal’ia Goncharova and the Moscow Avant-Garde (2005), which argued for Goncharova’s centrality in reclaiming Russia’s ‘Eastern’ cultural heritage.64 Christina Kiaer and Margarita Tupitsyn have also produced important new intellectual frameworks for the study of pre- and post-revolutionary women artists as well as, in Tupitsyn’s case, pioneering work on contemporary women’s art.65

Of particular import is Tupitsyn and Kiaer’s collaboration on the exhibition Rodchenko & Popova: Defining Constructivism, which opened at Tate Modern, London, in 2009. If in 1999, the sex of the artists determined the conceptualization of Amazons of the Avant-Garde, a decade later the gender difference between Popova and Rodchenko was no longer prioritized. Rather, Popova was presented along with Rodchenko as one of the signal artists of the Russian avant-garde and given an equal platform for the presentation and critical discussion of her work.66 The value of this relative inattention to sexual difference is a moot point. What provides the most profitable route for the exploration of women’s art – an emphasis on their distinctiveness, as in the Amazons exhibition, or the projection of parity, as in the Rodchenko and Popova show? Whatever the case, the sex of Russian, women artists and their supposedly unique characteristics will continue to shape assessments of, and responses to, their work. For Yablonskaya, writing in 2002, ‘the peculiar predisposition of women to visual analysis of reality has its own characteristic features that are no less valuable than those shown by men. The penetrating sensitivity of women, the sharpness of their intuitive reactions, the powerful and diverse structure of their sensations, particularly of the tactile ones, are the qualities especially valuable for creative activity’.67 At the same time, the liberation of a woman artist in Rodchenko & Popova from methods of display predicated on gender, heralds new avenues of enquiry, in which the apparent specificities of the female sex, if not disregarded, are at least downplayed. Such shifts of focus may portend ever keener concern to give women artists and their work the same level of exposure and critical enquiry as that afforded to men.

________________

This essay is dedicated to Alison Hilton, whose insightful research and intellectual generosity have supported so many scholars of Russian art. I am also grateful to Wendy Salmond, Jordana Pomeroy, and Jane Sharp for their many helpful comments and advice.

1.See Pierre de Nolhac, Madame Vigée Le Brun, peintre de la reine Marie-Antoinette, 1755–1842 (Paris: Manzi, Joyant and Co., 1908). For Vigée-Lebrun’s experiences in Russia, see Vospominaniia g-zhi Vizhe-Lebren: o prebyvanii ee v Sankt-Peterburge i Moskve 1795–1801, ed. by Damir V. Solov’ev (St Petersburg: Iskusstvo-SPB, 2004).

2.In broad surveys of Russian art, Jeremy Howard alone has made women artists prior to the late nineteenth century a focus of his work. See Jeremy Howard, East European Art 1650–1950 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 97–119.

3.Alison Hilton, ‘Domestic Crafts and Creative Freedom: Russian Women’s Art’, in Russia, Women, Culture, ed. by Helena Goscilo and Beth Holmgren (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1996), p. 347.

4.For Maria Fedorovna’s activities as an artist and patron, see Dmitrii F. Kobeko, ‘Imperatritsa Mariia Fedorovna, kak khudozhnitsa i liubitel’nitsa iskusstva’, Vestnik iziashchnykh iskusstv, II, 6 (1884), 399–410; Imperatritsa Mariia Fedorovna, ed. by Sergei V. Mironenko and Nikolai S. Tret’iakov (Pavlovsk: Art-Palas, 2000) and Rosalind P. Blakesley, ‘Sculpting in Tiaras: Grand Duchess Maria Fedorovna as a Producer and Consumer of the Arts’, in Women and Material Culture, ed. by Jennie Batchelor and Cora Kaplan (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), pp. 71–85.

5.‘These buttons are presented to the most beloved of mothers, by one kneeling at your feet beseeching you to accept her wishes and respect on this day, today 25th June 1790 Marie F.I’. Catalogue of The Russian Sale, Sotheby’s, London (1 December 2004), p. 262.

6.It is reasonable to suppose that Elizaveta and Sofia, the daughters of the professor of sculpture, Nicholas Gillet, and Ekaterina, the daughter of Karl Leberecht, received some form of artistic education thanks to their personal connections, as they feature in Academy records, in 1774 and 1807 respectively. See Sergei N. Kondakov, Iubileinyi spravochnik Imperatorskoi Akademii khudozhestv, 1764–1914, 2 vols (St Petersburg: P. Golike and A. Vil’borts, 1914), II, 69, 112.

7.Elena F. Petinova, Freiliny ee Velichestva: portrety vospitannits Imperatorskogo vospitatel’nogo obshchestva blagorodnykh devits Dmitriia Levitskogo (St Petersburg: Avrora, 2000), p. 16. For the Smol’nyi Institute under Maria Fedorovna’s direction, see Nikolai P. Cherepnin, Imperatorskoe Vospitatel’noe obshchestvo blagorodnykh devits: istoricheskii ocherk, 1764–1917, 2 vols (Petrograd: Gosudarstvennaia tipografiia, 1914), I, 297–620.

8.P. N. Petrov, Sbornik materialov dlia istorii Imperatorskoi S.-Peterburgskoi Akademii khudozhestv za sto let ee suchchestvovaniia, 3 vols (St Petersburg: Gogenfel’den and Co., 1864), I, 351–52.

9.See Iskusstvo zhenskogo roda: Zhenshchiny-khudozhnitsy v Rossii XV-XX vekov, ed. by Lidia I. Iovleva (Moscow: State Tret’iakov Gallery/Creative Laboratory INO, 2002), pp. 68–69.

10.See Petrov, Sbornik materialov, II (1865), 36.

11.Russian State Historical Archive, St Petersburg (RGIA), fund 789, opis’ 14, delo 18-Zh, pp. 1, 1, ob, 2.

12.RGIA, fund 789, opis’ 14, delo 110-K, ff 1, pp. 1, 6.

13.For the Academy’s increasing recognition of women artists in the early 1850s, see Rosalind P. Blakesley, ‘A Century of Women Painters, Sculptors, and Patrons from the Time of Catherine the Great’, in An Imperial Collection: Women Artists from the State Hermitage, ed. by Jordana Pomeroy, Rosalind P. Blakesley et al. (London: Merrell Publishers in association with the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington DC, 2003), pp. 70–71.

14.Aleksandra Venetsianova studied at the school that her father, Aleksei Venetsianov, established on his estate in Tver Province and Ekaterina Demidova and Elizaveta Nadezhina attended their father Afanasii Nadezhin’s art school in Kozlov, Tambov Province. See Nina Moleva and Elii Beliutin, Russkaia khudozhestvennaia shkola pervoi poloviny XIX veka (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1963), pp. 313, 382–83.

15.For the Ecole Nationale de Dessin pour les Jeunes Filles and its emphasis on teaching vocational skills in industrial design, see Tamar Garb, ‘“Men of Genius, Women of Taste”: The Gendering of Art Education in Late Nineteenth-Century Paris’, in Overcoming All Obstacles: The Women of the Académie Julian, ed. by Gabriel P. Weisberg and Jane R. Becker (New York: The Dahesh Museum in association with Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey and London, 1999), pp. 121–23.

16.Elena Antonova-Borovskaia, ‘Zhenskoe khudozhestvennoe obrazovanie v Rossii’, Russkoe iskusstvo, II (2010), pp. 124–29 (125).

17.For these and other details of the women’s classes in the St Petersburg Drawing School for Auditors, as well as the careers of some of the women who studied there, see Antonova-Borovskaia, ‘Zhenskoe khudozhestvennoe obrazovanie v Rossii’, pp. 124–29.

18.Many artists wrote of the hospitality that they received in Sukhovo-Kobylina’s Italian home, and of their impressions of her work. For further information, if still scant, on her life and work, see Varvara Ponomareva and Tatiana Zuikova, ‘Sof’ia Vasil’evna Sukhovo-Kobylina’, Russkoe iskusstvo, II (2010), pp. 131–34.

19.For examples of Sukhovo-Kobylina’s work, including a landscape, a self-portrait and the artist’s visual record of receiving her gold medal at the Academy, see Iskusstvo zhenskogo roda, pp. 77–79.

20.For Elizaveta Renne’s work on Robertson, see ‘A British Portraitist in Imperial Russia: Christina Robertson and the Court of Nicholas I’, Apollo (September 1995), pp. 43–45; ‘Christina Robertson in Russia’, in Christina Robertson: A Scottish Portraitist at the Russian Court, ed. by Amanda Farr (Edinburgh: City Art Centre, 1996), pp. 14–29; ‘Pridvornyi khudozhnik Kristina Robertson’, Nashe nasledie, 55 (2000), 35–37 and ‘Bridging Two Empires: Christina Robertson and the Court of St Petersburg’, in An Imperial Collection, pp. 87–99.

21.The only woman sculptor to achieve renown in Russia before the late nineteenth century was Marie-Anne Collot, the Frenchwoman who came to St Petersburg with Etienne-Maurice Falconet when he was commissioned by Catherine the Great to sculpt the equestrian monument to Peter the Great. See Irina G. Etoeva, ‘“Brilliant Proof of the Creative Abilities of Women”: Marie-Anne Collot in Russia’, in An Imperial Collection, pp. 77–85 and Alexander M. Schenker, The Bronze Horseman: Falconet’s Monument to Peter the Great (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003), pp. 111–16 and passim.

22.Gosudarstvennaia Tret’iakovskaia galereia: katalog sobraniia, ed. by Ian V. Bruk and Lidia I. Iovleva (Moscow: Skanrus, 2005), III (Zhivopis’ pervoi poloviny XIX veka), 90.

23.See Plenniki krasoty: Russkoe akademicheskoe i salonnoe iskusstvo 1830–1910-kh godov, ed. by Lidia I. Iovleva (Moscow: State Tret’iakov Gallery/Skanrus, 2004), p. 148.

24.Ekaterina A. Bobrinskaia, ‘Ital’ianskii zhanr v russkoi zhivopisi pervoi poloviny XIX veka’, in Plenniki krasoty, pp. 138, 142.

25.Ludmila A. Markina, ‘Woman Artists in Russia: from the Baroque to the Modern’, in Iskusstvo zhenskogo roda, pp. 59, 323.

26.See Russian Women, 1698–1917: Experience and Expression. An Anthology of Sources, compiled by Robin Bisha, Jehanne M. Gheith, Christine Holden and William G. Wagner (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2002), p. 183.

27.For the Kharkov School, see Kondakov, Iubileinyi spravochnik, pp. 238–42. Ivanova-Raevskaia’s school was reorganised in 1896 as the Kharkov City Painting School, which in turn became the Kharkov Art-Technical Institute in the early Soviet era. See Howard, East European Art, p. 112.

28.RGIA, fund 789, opis’ 14, delo 1-Iu, p. 8 and Nina Moleva and Elii Beliutin, Russkaia khudozhestvennaia shkola vtoroi poloviny XIX-nachala XX veka (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1967), pp. 153–54.

29.Sbornik postanovlenii Soveta Imperatorskoi Akademii khudozhestv po khudozhestvennoi i uchebnoi chasti s 1859 po 1890 god (St Petersburg: Tipografiia D-ta Udelov, 1890), p. 181.

30.Nina Dmitrieva, Moskovskoe uchilishche zhivopisi, vaianiia i zodchestva (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1951), p. 109.

31.Blakesley, ‘A Century of Women Painters, Sculptors, and Patrons’, pp. 74–75.

32.See Richard Stites, The Women’s Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860–1930 (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1978), pp. 168–73 and Christine Johanson, Women’s Strugglefor Higher Education in Russia, 1855–1900 (Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1987), pp. 95–103.

33.See Hilton, ‘Domestic Crafts and Creative Freedom’, p. 350; G. I. Pribul’skaia, ‘Repin i Akademiia khudozhestv. Po materialam biografii khudozhnika’, in Il’ia Efimovich Repin: k 150-letiiu so dnia rozhdeniia. Sbornik statei, ed. by Vladimir Leniashin (St Petersburg: State Russian Museum/Palace Edition, 1995), p. 104 and Alison Hilton, ‘“Bases of the New Creation”: Women Artists and Constructivism’, Arts Magazine, 55.2 (1980), 42.

34.Golubkina trained at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture from 1890–94 and at the Academy from 1894–95. On her work, see Aleksandr Kamenskii, Anna Golubkina: lichnost’, epokha, skul’ptura (Moscow: Izobrazitel’noe iskusstvo, 1990); Édouard Papet, ‘“La poésie de l’antiquité nationale”: céramique émaillée et bois sculpté en Russie, 1890–1914’, in L’Art russe dans la seconde moitié du XIXe siècle: en qu te d’identité (Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2005), pp. 344–50; Ol’ga Kalugina, Skul’ptor Anna Golubkina: opyt kompleksnogo issledovaniia tvorcheskoi sud’by (Moscow: Galart, 2006) and Ol’ga Kalugina, ‘Moskovskaia akademiia Anny Golubkinoi: k 100-letiiu masterskoi skul’ptora’, Russkoe iskusstvo, II (2010), 138–43.

te d’identité (Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2005), pp. 344–50; Ol’ga Kalugina, Skul’ptor Anna Golubkina: opyt kompleksnogo issledovaniia tvorcheskoi sud’by (Moscow: Galart, 2006) and Ol’ga Kalugina, ‘Moskovskaia akademiia Anny Golubkinoi: k 100-letiiu masterskoi skul’ptora’, Russkoe iskusstvo, II (2010), 138–43.

35.See, for example, Andrei I. Somov, ‘Zhenshchiny khudozhnitsy’, Vestnik iziashchnyk iskusstv, I, no. 3 (1883), pp. 356–83 (which focuses entirely on foreign women artists) and Anon, ‘Russkie khudozhnitsy’, Niva, 1 (1891), 16–18. On the First Ladies’ Art Circle and the St Petersburg Society for the Encouragement of Female Artistic and Craft Work, see Dmitrii Severiukhin, Staryi khudozhestvennyi Peterburg: rynok i samoorganizatsiia khudozhnikov (St Petersburg: Mir, 2008), pp. 344–50.

36.For French painters who taught women in their ateliers, and for early opportunities for women to study from the nude, see Germaine Greer, ‘“A tout prix devenir quelqu’un”: the women of the Académie Julian’, in Artistic Relations: Literature and the Visual Arts in Nineteenth-Century France, ed. by Peter Collier and Robert Lethbridge (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994), pp. 40–45, 54. For women’s access to life drawing in France more generally, see Tamar Garb, ‘The Forbidden Gaze: Women Artists and the Male Nude in Late Nineteenth-Century France’, in The Body Imaged: The Human Form and Visual Culture Since the Renaissance, ed. by Kathleen Adler and Marcia Pointon (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp. 33–42.

37.See Greer, ‘“A tout prix devenir quelqu’un”’, pp. 53–54 and Catherine Fehrer, ‘Women at the Académie Julian in Paris’, The Burlington Magazine, 136, no. 1100 (November 1994), 752–57.

38.Hilton, ‘Domestic Crafts and Creative Freedom’, p. 351.

39.‘When women were clamouring for the right to attend the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, they were struggling to board a sinking ship’. Greer, ‘“A tout prix devenir quelqu’un”’, p. 57.

40.Tovarishchestvo peredvizhnykh khudozhestvennykh vystavok: pis’ma, dokumenty 1869–1899, ed. by Sofiia N. Gol’dshtein, 2 vols (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1987), II, 387, 445. For an example of Shanks’ work, see Iskusstvo zhenskogo roda, p. 105.

41.Minutes of the Academy Council meeting of 27 February 1876: Sbornik postanovlenii, pp. 181–82.

42.The Académie Julian proved particularly popular, attracting Marie Bashkirtseff from 1877–81, Ekaterina Zarudnaia-Kavos from 1885–86 and Mariia Iakunchikova from 1889–92. For rising interest in the Ukrainian Bashkirtseff (Mariia Bashkirtseva, 1858–84), see Jane R. Becker, ‘Nothing like a Rival to Spur One On: Marie Bashkirtseff and Louise Breslau at the Academie Julian’, in Overcoming All Obstacles, pp. 69–113; The Journal of Marie Bashkirtsef, translated by Mathilde Blind (London: Virago, 1985); Colette Cosnier, Marie Bashkirtseff: un portrait sans retouches (Paris: Pierre Horay, 1985); Marie Bashkirtseff: peintre et sculpteur & écrivain et témoin de son temps (Nice: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1995) and Hilde Hoogenboom, ‘The Famous White Box: The Creation of Mariia Bashkirtseva and Her Diary’, in Gender and Sexuality in Russian Civilisation, ed. by Peter I. Barta (London: Routledge, 2001), pp. 181–204.

43.For independent institutions where women could receive an artistic education in late nineteenth-century Russia, see Aleksei Novitskii, Istoriia russkogo iskusstva, 2 vols (Moscow: V. N. Lind, 1903), II, 518–19.

44.See, for example, Alison Hilton, Russian Folk Art (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995); Wendy Salmond, Arts and Crafts in Late Imperial Russia: Reviving the Kustar Art Industries, 1870–1917 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996) and Karen Kettering, ‘Enamels from the Moscow Workshop of Mariia Semenova’, The 49th Washington Antiques Show: Women of Metal (2004), pp. 81–88.

45.See Jesco Oser, Mir emalei kniagini Marii Tenishevoi (Moscow: private publisher, 2004). For Tenisheva’s life, see Larisa Zhuravleva, Kniaginia Mariia Tenisheva (Smolensk: Poligramma, 1994).

46.Wendy Salmond, ‘The Solomenko Embroidery Workshops’, The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, Russian/Soviet Theme Issue, 5 (1987), 126–43.

47.See Polenova’s correspondence with Pelageia Antipova, Sergei Ivanov, and Mariia V. Iakunchikova in Vasilii Dmitrievich Polenov, Elena Dmitrievna Polenova: khronika sem’i khudozhnikov, ed. by Elena V. Sakharova (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1964), pp. 382, 450, 455.

48.‘E. D. Polenova’, Mir iskusstva, II/18–19 (1899), 97–120.

49.Elena Sakharova, Elena Dmitrievna Polenova, 1850–1898 (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1952).

50.For a recent account of Polenova’s oeuvre, see Kristen M. Harkness, ‘The Phantom of Inspiration: Elena Polenova, Mariia Iakunchikova and the Emergence of Modern Art in Russia’, PhD thesis, University of Pittsburgh, 2009. For appreciation in Britain of Polenova’s work, see Rosalind P. Blakesley, ‘“The Venerable Artist’s Fiery Speeches Ringing in my Soul”: The Artistic Impact of William Morris and his Circle in Nineteenth-Century Russia’, in Internationalism and the Arts, ed. by Grace Brockington (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2009), pp. 96–99.

51.See Mikhail Kiselev, Mariia Vasil’evna Iakunchikova 1870–1902 (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1979).

52.See Alison Hilton, ‘Zinaida Serebriakova’, Women’s Art Journal III/2 (1982/83), 32–35; Tatiana A. Savitskaia, Z. Serebriakova: izbrannye proizvedeniia (Moscow: Sovetskii khudozhnik, 1988); Zinaida Serebriakova: pis’ma, sovremenniki o khudozhnitse, ed. by Valentina Kniazeva (Moscow: Izobrazitel’noe iskusstvo, 1987) and Alla Rusakova, Zinaida Serebriakova, 1884–1967 (Moscow: Iskusstvo-XXI vek, 2006).

53.For textile and clothing designs, see Natalia Adaskina, ‘Constructivist Fabrics and Dress Design’, The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, Russian/Soviet Theme Issue, 5 (Summer 1987), pp. 144–59.

54.Wendy Salmond, ‘Training and Professionalism: Russia’, in Dictionary of Women Artists, ed. by Delia Gaze, 2 vols (London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997), I, 119. Salmond’s article (115–21) remains the richest account in English of the education of Russian women artists. For women’s architectural training more generally, see Nina Smurova, ‘Iz istorii vysshego zhenskogo arkhitekturnogo obrazovaniia v Rossii’, Problemy istorii sovetskoi arkhitektury (Sbornik nauchnykh trudov) (Moscow: TsNIIP gradostroitel’stva, 1980), pp. 110–18.

55.Jane A. Sharp, ‘Redrawing the Margins of Russian Vanguard Art: Natalia Goncharova’s Trial for Pornography in 1910’, in Sexuality and the Body in Russian Culture, ed. by Jane T. Costlow, Stephanie Sandler and Judith Vowles (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1993), p. 98.

56.Iakov Tugendkhol’d, ‘Vystavka kartin Natalii Goncharovoi’, Apollon, 8 (October 1913), 72: cited in Sharp, ‘Redrawing the Margins of Russian Vanguard Art’, pp. 120–21.

57.Letter from K. A. Somov to A. A. Somov, Paris, 1897, in Konstantin Andreevich Somov. Pis’ma, dnevniki, suzhdeniia sovremennikov, compiled and annotated by Iu. N. Podkopaeva and A. N. Sveshnikova (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1979), p. 61.

58.Helena Goscilo and Elena Kornetchuk, ‘Canvassing Gender: Recent Women’s Art’, in Iskusstvo zhenskogo roda, p. 169.

59.Exhibition catalogues include Women Artists 1550–1950, ed. by Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1976), which included Bashkirtseff, Goncharova, Udal’tsova, Ekster, Rozanova and Popova; and those of broader scope, such as International Arts and Crafts, ed. by Karen Livingstone and Linda Parry (London: V&A Publications, 2005), which included works by Polenova and Tenisheva. For reference works, see Dictionary of Women Artists: An International Dictionary of Women Artists born before 1900, ed. by Chris Petteys (Boston, Mass.: G. K. Hall & Co., 1985) and especially Dictionary of Women Artists, ed. by Delia Gaze, which contains substantial entries on many of the women mentioned in this account.

60.As examples, see Miuda Yablonskaya, Women Artists of Russia’s New Age, 1900–1935 (New York: Rizzoli, 1990); Dmitri Sarabianov and Natalia Adaskina, Popova, translated by Marian Schwartz (London: Thames and Hudson, 1990); Aleksandr Rodchenko. Varvara Stepanova. Budushchee – edinstvennaia nasha tsel’, ed. by Peter Never (Munich: Prestel, 1991); Georgii Kovalenko, Aleksandra Ekster. Put’ khudozhnika. Khudozhnik i vremia (Moscow: Galart, 1993); Dmitrii Sarab’ianov, Liubov’ Popova (Moscow: Galart, 1994) and N. A. Udal’tsova: zhizn’ russkoi kubistki. Dnevniki, stat’i, vospominaniia, compiled by Ekaterina Drevina and Vasilii Rakitin (Moscow: RA, 1994).

61.John E. Bowlt, ‘Women of Genius’, in Amazons of the Avant-Garde. Alexandra Exter, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, Varvara Stepanova, and Nadezhda Udaltsova, ed. by John E. Bowlt and Matthew Drutt (New York: Guggenheim Museum Publications, 2000), pp. 24–26.

62.Natal’iia Goncharova. Gody v Rossii (St Petersburg, Palace Editions, 2002).

63.Iskusstvo zhenskogo roda, pp. 11, 34–51.

64.Jane A. Sharp, Russian Modernism between East and West: Natal’ia Goncharova and the Moscow Avant-Garde (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005).

65.See, for example, Margarita Tupitsyn, ‘Unveiling Feminism: Women’s Art in the Soviet Union’, Arts Magazine (December 1990), 63–67 and Christina Kiaer, Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2005).

66.If Popova’s identity as a woman artist within constructivism is not foregrounded in the exhibition, it is addressed in the catalogue. See Christina Kiaer, ‘His and Her Constructivism’, in Rodchenko & Popova: Defining Constructivism, ed. by Margarita Tupitsyn (London: Tate Publishing, 2009), pp. 143–59.

67.Miuda Yablonskaya, ‘A “New” Phenomenon? An Essay on Systematization’, in Iskusstvo zhenskogo roda, p. 134.