4. Digital Humanities and the First-Year Writing Course

Olin Bjork

Stanley Fish’s contention, in Save the World on Your Own Time, that “composition courses should teach grammar and rhetoric and nothing else” because “content is always the enemy of writing instruction” was provocation enough for a 2009 Modern Language Association (MLA) convention session on the relation between composition and the humanities.1 The first two panelists, John Schilb and Arabella Lyon, argued that, pace Fish, composition courses should not focus on writing itself, but rather on humanistic topics like political theory or philosophy.2 They agreed with Fish, however, that a first-year writing course—required at most American colleges and universities for students who do not “place out” through certain standardized tests—afforded little or no time to teach students to analyze the objects of digital culture, much less to use new media technologies.

This consensus flies in the face of a “Position Statement on Multimodal Literacies” approved by the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), which holds that “skills, approaches and attitudes toward media literacy, visual and aural rhetorics, and critical literacy should be taught in English/Language Arts classrooms.”3 More specifically, according to the “Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition” adopted by the Council of Writing Program Administrators (WPA), students should “understand and exploit the differences in the rhetorical strategies and in the affordances available for both print and electronic composing processes and texts.”4 Indeed, the trend in college-level classrooms, especially in the United States, is to focus neither on “form” (i.e., basic writing and speaking strategies), nor on “content” from the traditional, material humanities, but rather on communication modes, new media and contemporary culture. Jeff Rice argues that the rise of the field of composition studies since the 1960s, traditionally attributed to increasing theoretical sophistication both in scholarship and in classroom practice, is also highly correlated with “technological, visual, and cultural studies movements paralleling the field’s rebirth.”5

These movements are associated with interdisciplinary fields such as technology studies, visual culture and cultural anthropology whose theories and methodologies have become increasingly vital to scholarship in rhetoric and composition. Yet when it comes to writing pedagogy, the primary influence of these movements has been to bring new objects of study into the classroom that are then analyzed through more traditional rhetorical frameworks such as assumptions, appeals and fallacies. Increasingly, not only elective and upper-level composition courses but also first-year writing courses consist of sections with different “cultural studies” themes such as Emo, zombies, baseball, popular feminism or Harry Potter. Within these topics, as well as weightier ones such as immigration or globalization, a range of cultural forms involving multiple modes of communication (aural, visual, written, non-verbal) and media (TV, film, Internet, video games, print) are considered fair game for analysis.

In this respect, it appears that composition is moving toward digital humanities even as it moves away from the material humanities, or that the humanities, in becoming digital, have moved toward composition. But this supposition is at best only half true. In “The Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0,” Todd Presner, Jeffrey Schnapp and numerous other contributors observe that digital humanities has been moving in two different directions: “The first wave of digital humanities work was quantitative, mobilizing the search and retrieval powers of the database, automating corpus linguistics, stacking hypercards into critical arrays. The second wave is qualitative, interpretive, experiential, emotive, generative in character.”6 N. Katherine Hayles astutely connects this “first wave” to a field that, from the mid- to late-twentieth century, was known as humanities computing.7 Primarily based in traditional humanities departments or academic technology service units, humanities computing focused on scholarly activities such as text-based data entry and programming for stylistics, concordances and apparatuses. In the late 1990s, however, scholars at new humanities centers, institutes and offices formed in the blossoming of the internet opted to change the name of the evolving and expanding field to “digital humanities.” The name change, however, did not signal the end of the first wave and the start of the second; in the first of four articles surveying the field for Digital Humanities Quarterly, Patrik Svensson finds that most of the work self-identifying as “digital humanities” remains in the humanities computing tradition.8 This tradition, he argues, entails an instrumentalist view of technologies as “tools,” a focus on texts as primary objects of study, and text encoding and text analysis as privileged methodologies.

The other major area within digital humanities is new media studies (alternatively named digital media studies). This field, broadly construed, views technologies as objects of study, not just tools. Instead of material culture and digitized objects, new media scholars focus on digital culture and “born-digital” objects such as blogs, computer games, email lists, interactive maps, machinima videos, text messages, user-generated content and virtual worlds. Their approach to the digital tends to be more theoretical than methodological, bearing the qualities that Manifesto 2.0 associates with the “second wave.” Finally, whereas humanities computing has traditionally been a research domain for faculty, librarians, and technologists, new media studies is a growing area of both undergraduate and graduate education. New media studies programs make their institutional homes in departments as diverse as Architecture, Mass Communication, Computer Science, English and Film, although many practitioners in the field are specialists who do not teach in such programs.

The divide between humanities computing and new media studies within digital humanities roughly aligns with the divide between literature and composition within English studies. Whereas a significant percentage of humanities computing projects, if not the majority, have involved literature faculty, the use of computers in the teaching of writing seems to have a separate history from that of humanities computing.9 Today the subfield of composition studies known as computers and writing (or computers and composition) has more in common with new media studies. The fields share a more qualitative than quantitative research and teaching profile, pedagogical orientation and a view of digital objects and culture as worthy of study in their own right, not merely for what they reveal about material objects and culture. Perhaps most significantly, instructors of computers and writing, like their counterparts in new media studies, now tend to incorporate into their pedagogies student production of multimodal digital objects.

The movement to teach students to be engaged producers and not merely informed consumers of digital culture reflects a shift in composition theory. In the 1990s, scholars such as Cynthia L. Selfe, Anne Frances Wysocki and Johndan Johnson-Eilola discussed new media under the rubric of literacy, arguing that digital forms challenge traditional notions of oral and print literacy and that we must now either discard the goal of literacy or accept the task of teaching multiliteracies, first articulated by the New London group.10 More recently, a younger generation of composition scholars, such as Collin Gifford Brooke and Jeff Rice, have sought to define a rhetoric of new media that would supplement or even replace the traditional canons of rhetoric, which they view as so firmly grounded in chirographic and print technologies as to have made that material base of communication invisible for centuries until it was revealed again by new media. The formulation of a rhetoric of new media distinct from that of older media not only justifies student digital projects but also entails a theoretical focus on contemporary high tech culture and a certain faddishness in computers and writing research and pedagogy. Brooke, for example, analyzes Wikipedia and the multiplayer online role-playing game World of Warcraft,11 while Rice practices a “hip-hop pedagogy” in which students simulate in their hypertexts some of the writing and sampling practices of graffiti and rap artists.12

The scope of computers and writing projects, in contrast to those in the digital humanities, tends to be constrained by three factors: the technical proficiency of undergraduates and instructors, the timeframe of a single semester or quarter, and the availability of hardware and software. Especially in the first-year writing course—where the curriculum often specifies a minimum page requirement and where instructors are under pressure to teach basic reading, writing and argumentation strategies, fitting in multimodal literacies when and if they can—only small-scale projects are manageable. In the 1990s, a “hyper-essay” or thematic webpage, usually hosted on a private server, was the standard assignment. Since the last decade, however, a movement in web-based application design known as Web 2.0, which enables user-created content and online platforms, has inspired a new direction for computers and writing assignments. Students now contribute text and static images to blogs and wikis, build spaces within virtual worlds such as Second Life (http://www.secondlife.com), and make movies and podcasts to share online. Technical barriers are diminishing as free and open source software and the latest smartphones, which can record audio and/or video, make their way into the hands of the average college student. In addition to reservations about quality, however, privacy or copyright issues often prevent or discourage the public sharing of student work on sites like YouTube or Flickr. Therefore, despite pedagogical rationales that emphasize the value of participatory media and interaction with a larger online community, many student Web 2.0 projects either remain protected within learning management systems or are hosted publicly for a limited time. Typically, however, such projects are not ends in themselves but lead to essays, presentations, or ePortfolios in which students defend their design choices in rhetorical terms.

Humanities Computing for Computers and Writing

In the third and final paper at the 2009 MLA session on composition and the humanities, my colleague John Pedro Schwartz and I followed up professors Schilb and Lyon by stressing the largely untapped potential of humanities computing practices and technologies for computers and writing.13 We sought to avoid promoting innovation for innovation sake and instead articulate a rationale that would appeal to the widest swath of composition scholars and instructors, even those determined never to engage in digital pedagogy. When considering the research orientation of humanities computing, it had occurred to us that among the seemingly limitless teaching outcomes of first year-writing courses is the inculcation of basic research skills. Composition textbooks draw a distinction between primary and secondary research and between qualitative and quantitative research. The first of these dichotomies tends to be well treated both in the textbooks and in the courses themselves, though the balance leans toward secondary research. To teach secondary research, instructors will typically assign at least one essay topic necessitating moderate to heavy citation, train students to document and evaluate sources, and take them to the library and/or have a librarian visit the class. Another course project may involve such primary research techniques as surveying students or interviewing administrators. In regard to the second binary, however, neither the textbooks nor the courses tend to apply it to student work. Although researchers in the field use quantitative methods, the bulk of the scholarship is qualitative, and in the interest of simplification and practicality this bias becomes magnified in the classroom to the point that the distinction becomes academic. This state of affairs is problematic because the first-year writing class is supposed to prepare students for future writing experiences, and many of these students will major in highly quantitative, primary research fields.

Based on this diagnosis, we argued that importing primary and quantitative research methods from humanities computing would serve as a corrective for the first-year writing course. Of course, traditional categories are less viable in a digital context—is a digitized primary artifact a primary or secondary artifact? A weakness of digital humanities is that it under-theorizes the transformation of material objects into digital objects. As an example of the field’s inattention to digital codes as opposed to material ones, Hayles points to the documentation of a flagship digital humanities project, the William Blake Archive (http://www.blakearchive.org):

Of course the editors realize that they are simulating, not reproducing, print texts. One can imagine the countless editorial meetings they must have attended to create the site’s sophisticated design and functionalities; surely they know better than anyone else the extensive differences between the print and electronic Blake. Nevertheless, they make the rhetorical choice to downplay these differences. For example, there is a section explaining that dynamic data arrays are used to generate the screen displays, but there is little or no theoretical exploration of what it means to read an electronic text produced in this fashion rather than the print original.14

It is debatable whether the Blake editors would consider their “rhetorical choice” to be a choice at all, for it would be difficult for them to underscore such differences and still assert, as they do, that the site is an archive of Blake’s works. While humanities computing, as typified by the Blake Archive, tends to treat the digital surrogate as the material original, new media studies tends not to create digital surrogates. Composition studies, therefore, is well positioned to fill the gap by tracking how digitization modifies the rhetorical situation and properties of an artifact. As for the already somewhat tenuous and expedient distinction between quantitative and qualitative research, the two approaches may blend together in any particular digital humanities project. The Blake Archive, for example, offers both qualitative and quantitative applications and tools. Far from being an obstacle to pedagogy, these definitional quandaries can provoke productive class discussions.

In our paper, we used the term “quantitative” to refer to research that uses computation to sort or process data and generate a list of hits, table of results, graphical representation, etc., and “qualitative” for research that uses computers primarily for their storage, linking and multimedia display capabilities, relying primarily on human processing of content. Humanities computing projects, unlike those in new media studies, tend not to be qualitative in the sense of delivering a rich multimedia experience to the user. This tendency is noted by Svensson, who ascribes it to the field’s textual focus and lack of investment in human-computer interface design.15 But the field also faces legal and ideological barriers on the path to multimodality. Since most artifacts created after 1922 are still under copyright, the great bulk of films and music are off-limits to those digital humanists who seek to digitize and publish cultural heritage materials, and consequently the texts and images contained in their electronic archives are often presented as pages that could (and often did) appear in a old book or manuscript. Furthermore, the humanities computing community is philosophically committed to publishing with open web standards, such as CSS, HTML, and XML. This policy is quite feasible when the content is static text and images. However, when the content includes rich media such as animation, audio, and/or video, until recently there have been few reliable open source equivalents to proprietary technologies, such as Adobe Flash, which combine expensive development environments with free browser plug-in players.

The landscape is rapidly changing, however. Third party plug-ins are no longer necessary to display rich media in the latest browsers, and free and open source software for reading, writing, and publishing rich media is beginning to appear. One such product is Sophie (http://sophieproject.org), which is distributed by the Institute for Multimedia Literacy at USC. Sophie is designed for collaborative authoring and viewing of rich media “books” in a networked environment. Sophie books combine text with notes, images, audio, video and/or animation. Sophie offers server software for collaborative online authoring, an HTML5 format for multi-device publishing, and comment frames for discussion within the books.

Sophie has already been used in classroom projects. Sol Gaitán of the Dalton School in New York developed a Sophie book for her AP Spanish students so that they could explore the direct influence of particular flamenco music styles on Federico García Lorca’s poetry.16 In an Introduction to Digital Media Studies class at Pomona College, Kathleen Fitzpatrick’s students selected texts that they had read together for class and turned them into Sophie books.17 In terms of goals, Gaitán’s project shares with humanities computing the use of the electronic edition as a means of yielding insight into material objects and culture; in this case, Lorca’s poetry. Conversely, Fitzpatrick’s assignment uses the electronic edition in order to yield insights into digital objects and culture; in this case, Sophie books.

What might Sophie projects look like in a writing classroom? Schwartz and I contended that a qualitative humanities computing practice such as electronic editing could be adapted to achieve the traditional goals of composition pedagogy. Creating digital editions of speeches, books and essays from oral and print sources can reveal the rhetorical differences between digital and material culture. Students could select an argumentative text from the public domain, or for which rights have been waived—say, the Lincoln-Douglas debates—and use Sophie to create an electronic edition of the text annotated with notes, images, audio, video and/or animation. It might also include a rhetorical analysis of the text, either in the form of textual annotation or a separate section of the book. The comment feature would encourage fellow students to provide feedback on annotation and to debate points made in the rhetorical analysis. Upon completion of the edition, students might write an essay reflecting on their design decisions and the different mediatory and rhetorical properties and situations of the oral debates, the material records and their own digital edition. The first activity—design of an electronic edition of a canonical text—is typical of humanities computing. The second activity—rhetorical analysis and discussion of a text—is typical of computers and writing. The third activity—reflection on media and interface design—is typical of new media studies.

To complement such a qualitative research project, writing instructors can assign a quantitative research project to expand the analytical repertoire of their students from the rhetorical analysis of exempla to the computational analysis of corpora. Ideally, combining these two forms of analysis will allow students to become not only “close readers” but also “distant readers,”18 no longer content with supporting their insights on culture and rhetoric solely with examples from individual texts. Students need not, as in humanities computing, study digitized material texts; they can turn instead to corpora of digital cultural production. In a text-mining project, students would use text-analysis tools to look for patterns and anomalies, and then report on their findings. This process would give students a new perspective on language and rhetoric as well as experience in using quantitative research methods and writing a technical report, activities that many of them will engage in later, both in college and in their careers.

In its most general application, the term text mining refers to the extraction of information from, and possibly the building of, a database of structured text. The term text analysis (or text analytics) is roughly synonymous with text mining but tends to be preferred in the case of natural language datasets with comprehensible content and well-defined parameters.19 Many composition teachers have been exposed to text analysis through plagiarism detection tools like Turnitin (http://www.turnitin.com), which compares student submissions to previous submissions stored in databases as well as to online sources, or through pattern analysis tools that perform preliminary scoring of student or applicant essays. Search engines like Google, meanwhile, can be used to mine thematic subsets of the web. In a 2009 Kairos article, Jim Ridolfo and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss discuss a composition exercise informed by their theory of “rhetorical velocity,” which in this instance means the extent, speed and manner in which keywords and content from government, military and corporate presses show up in news articles. Students select phrases from a recent press release and search for these phrases on the web as well as on the Google News (http://news.google.com) aggregator site. They then compare their results with the original release and discuss how the content was recomposed, quoted and/or attributed by the news media.20

A simple form of text analysis that some writing instructors employ is the tag or word cloud, which visualizes information based on the metaphor of a cloud. The cloud consists of words of different sizes, with the size of each word determined by the frequency of its appearance in a given text. On many blogs and photo-sharing sites, a script automatically generates a word cloud based on the blog entries or image tags. Wordle (http://www.wordle.net) is a free online tool that allows users to generate a word cloud from a text and edit its colors, orientations, and fonts. By making word clouds from their papers, writers can gain a new perspective on issues of diction (see Figure 1). The developers of Wordle describe it as a toy, and indeed word and tag clouds function more as artistic images than as sophisticated informational displays. In a ProfHacker blog entry, Julie Meloni calls Wordle “a gateway drug to textual analysis.”21

Figure 1. Wordle of Bjork and Schwartz’s 2009 MLA Convention paper.

True textual analysis calls for a more powerful tool and a larger corpus. In a 2009 first-year writing course at Georgia Tech, David Brown taught his students to use AntConc (http://www.antlab.sci.waseda.ac.jp/antconc_index.html) and the Corpus of Contemporary American English or COCA (http://corpus.byu.edu/coca/). AntConc is a freeware concordance program named after its creator Laurence Anthony, a professor of English language education at Waseda University in Japan. The software is frequently used to assess or research corpora of student writing.22 Instructor Brown’s students used AntConc to search for linguistic features in the COCA corpus and wrote papers reporting their findings. With over 425 million words drawn from American magazines, newspapers and TV shows, COCA may be “the largest freely available corpus of English,” as its documentation claims. Some students went beyond the call, comparing features of COCA to those of corpora derived from Twitter, personal blogs and online reviews. In a follow up assignment, each student assembled a corpus of his or her own academic writing and used AntConc to compare linguistic features of this corpus to a corpus of other students’ writing as well as a corpus of published academic prose. Students learned to use Part of Speech (POS) tags to search for grammatical patterns within these corpora.

Beyond teaching research methods, Schwartz and I concluded that bringing qualitative and quantitative digital humanities projects into a first-year writing course would further several additional disciplinary and curricular aims. First, the combination would entail both a focused and a panoramic view of either humanistic content, such as the politico-philosophical discourse that Schilb and Lyon advocate, or cultural studies content, which is increasingly the predilection of composition pedagogy. Second, linguistic text-analysis could potentially be a more effective approach to learning about sentence structure than Fish’s content-free writing pedagogy, which involves language creation, sentence diagramming and syntax imitation.23 Third, digital editing would facilitate the teaching of multimodal literacies and the composing in electronic environments advocated by the NCTE and the WPA respectively. Finally, the assimilation of humanities computing practices by computers and writing, and vice versa, would help bridge the divide between literature and composition, adding coherence to the discipline of English studies.

Teaching Digital Humanities in the Writing Classroom

The 2009 MLA session on composition and the humanities was well attended and there was much discussion following the papers. Scott Jaschik covered the session for the online daily Inside Higher Ed with an article titled “What Direction for Rhet-Comp?”24 Among the comments posted below the article, a reader questioned by what right MLA served as the forum for this question as opposed to a rhetoric and composition conference like the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC). Though a major conference, CCCC is more specialized than MLA, incrising the odds that some potential directions might not be considered there. The Computers and Writing conference, meanwhile, did not have a panel on their field’s relation to digital humanities until 2011.25 Having presented at the MLA five times since 2005 on topics related to computers and writing and/or digital humanities, I have found that it is one of the few venues where diverse humanities fields regularly cross-pollinate. The 2012 MLA convention bore the fruit of these transactions; there were almost twice as many sessions on digital approaches to literature, art, culture or rhetoric as there had been in any of the previous seven years. The spike prompted Stanley Fish to write three New York Times blog columns bemoaning the digital awakening of mainstream literary studies. In the second of these columns, Fish argues that non-linear, multimodal, and collaborative Web 2.0 textuality works against conventional notions of authorship and asks, “Does the digital humanities offer new and better ways to realize traditional humanities goals? Or does the digital humanities completely change our understanding of what a humanities goal (and work in the humanities) might be?”26 In the third column, Fish answers his own questions with regard to text mining, a method that he feels changes our understanding of literary analysis because it is not “interpretively directed,” rather you “proceed randomly or on a whim, and see what turns up.”27

As of the 2009 MLA convention, neither my co-presenter nor I had fully put into practice our theory that the methods of digital humanities could be used in the classroom to realize not only traditional humanities goals but also traditional composition goals. However, in the summer of 2010 at Georgia Tech, I had the opportunity to teach a first-year writing class on the theme of digital humanities to fresh high school graduates enrolling for an intensive six-week semester. The major projects in the class were a qualitative research project and a quantitative research project. For the qualitative project, students selected a single humanities text and turned it into a multimedia edition with annotations, images, and audio or video. For the quantitative project, students assembled a corpus of humanities texts, which they then mined with electronic text-analysis tools to find patterns or anomalies.

In these projects, students were confronted with challenges familiar to digital humanists engaged in similar endeavors. As editors and hypothetical publishers of their editions, students needed to learn about copyright and use only those texts, images and clips that had been released to the public for reproduction and redistribution. Some students chose texts from the public domain, while others excerpted from copyrighted texts or selected materials published under Creative Commons licenses. As quantitative researchers, meanwhile, they were tasked with constructing a valid research hypothesis, selecting representative data, extracting relevant results from this data and assessing their findings. In both projects, students had to employ open-source software: Sophie 2.0 and AntConc respectively.

Of the two projects, the qualitative was less successful from a technical standpoint due to the limitations of Sophie 2.0. Although I had tested this software on my own computer, the participating students had just purchased brand new laptops with the latest operating systems on which Sophie 2.0 was not verified to be compatible. On many of these machines, Sophie 2.0 was so bug-ridden and liable to crash that I had to lower the expectations for media and interactivity. Students struggling with the software also had less time to write annotations explaining and analyzing the text of their editions. Although I had intended the project to suggest the rhetorical possibilities unleashed through the interplay of different modes and media, it instead illustrated a problem plaguing free and open source software: the lack of a developer base extensive enough to adequately debug and update the software.

The qualitative project did, however, deliver on some of its pedagogical objectives. Students learned to apply the principles of intellectual property, the fair use doctrine, and the public domain. They also developed rough and ready distinctions between an edition, a text, and a work. If not all of the students were advanced enough to be insightful editors and annotators, most of them learned to appreciate the power that editing and annotation exert over a text. Some demonstrated awareness of the gulf between their multimedia presentation of the text and its original context. For example, the text that one student used in her edition of Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech to the 1775 Virginia Convention (see Figure 2) was reconstructed after the orator’s death based on the accounts of audience members. Although the student did not acknowledge that the text is at best a close approximation of the speech’s verbal content, she was appreciative of the different rhetorical situation of a speech versus a book. In her rhetorical analysis, she argued that the speech is light on evidence and narrative details but heavy on pathos and ethical appeals because Henry recited his address from memory and at any rate his audience was familiar with the facts of the case. To provide a sense of the original context, her edition includes clips from an audio reenactment on LibriVox and a contemporary illustration of Henry rousing the delegates. If the student had pursued the differences further, she might have noted that since the user of her edition can read the electronic text with or without the audio voiceover and open the annotations that supply the missing historical facts, the work has been completely transformed by the editor in order to accommodate an audience for which it was never intended.

Figure 2. Student’s Sophie Book example. This edition of Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death,” as displayed in the Sophie Reader application, includes a column for annotations to the right of the primary text. On this page, the student has provided an excerpt from an audio rendition of the speech as well as an image of the site where the speech was first given.

AntConc proved to be more reliable than Sophie 2.0. Although AntConc is relatively up-to-date and bug free, as of 2010 the documentation, consisting of a “readme” file and an “online help system,” was not as accessible as the Sophie 2.0 website’s combination of video screencasts and step-by-step textual instructions with screenshots (helpful video tutorials and a brief manual have since been added to the AntConc website). The AntConc readme, like most specimens of the genre, combines a text-only format with a matter-of-fact writing style. The online help system, meanwhile, reproduces the how-to portion of the readme while adding a few smallish screenshots. This documentation, though technically sound, assumes an audience familiar with the basics of corpus linguistics and therefore points up another problem plaguing free and open source software: the lack of documentation suitable for the uninitiated.

In order to use AntConc and other quantitative tools successfully, my students read Svenja Adolphs’ Introducing Electronic Text Analysis.28 This book was recommended to me, along with AntConc and the other resources used in the project, by David Brown, a colleague at Georgia Tech with a background in computational linguistics. Whereas Brown’s first-year writing course projects, briefly described in the previous section, were spread out over most of a fifteen-week semester, I had just three weeks to spend on electronic text analysis. Consequently, I decided not to cover the more exact techniques such as chi-square, log likelihood, mutual information, and POS tagging, instead limiting coverage to more straightforward concepts such as collocates, frequency, keyness, n-grams, semantic prosody and type-token ratio. This more limited analytical framework proved difficult enough for the students to master, especially since Adolphs’ book, while perhaps the most accessible introduction then available in print, is pitched to an advanced undergraduate or postgraduate audience with a basic knowledge of statistics.

For the quantitative assignment, students formulated a research question or hypothesis and then constructed a specialized corpus of plain text documents on which they could test their hypothesis. Unlike a general corpus, a specialized corpus is not representative of a language but rather of a certain type of discourse such as that of a particular profession, individual, generation, etc. Students used their specialized corpus as a target corpus to compare against a larger reference corpus. The most common choices for a reference corpus were COCA, which was described in the previous section, and the Corpus of Historical American English or COHA (http://corpus.byu.edu/coha), which contains 400 million words drawn from American fiction, magazine, newspaper, and non-fiction writing. Both of these resources were created by Mark Davies, a professor of corpus linguistics at Brigham Young University, and funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Although their frame-based interface has some usability issues, COCA and COHA are well documented with explanations and examples. At the time of this assignment, the Google Books Ngram Viewer (http://books.google.com/ngrams/), which fronts corpora drawn from books written in Chinese, English, French, German, Hebrew, Russian and Spanish, had not yet been released. Davies argues that COHA, though many times smaller, is superior to Google’s American English corpus for research because his site provides more versatile and robust searching techniques and more reliable and rigorously structured data.

I afforded the students broad leeway in constructing their corpora of humanities texts. Of the 23 students in the course, 13 worked with corpora drawn from rock and roll, hip-hop and other popular music genres. The majority of these students were not so much interested in identifying genre characteristics, which at any rate would have been difficult to accomplish experimentally, as they were in comparing artists or bands, so their target corpora were usually divided between two or more datasets each representing the music lyrics of a single artist or band. Of the remaining ten students, four focused on political speechmakers, four on novelists, one on the linguistic relation between Shel Silverstein’s children’s books and his writings for adults (including features in Playboy), one on the historical discourse surrounding marijuana, and one on a year of football sports-writing at the official athletics websites of Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia.

Although I was flexible about content, I prompted students to explain their selection criteria to show that their corpus was a representative dataset sufficient to their research question. Unfortunately, the criteria of representativeness, which I had internalized and therefore lacked the foresight to cover, proved slippery for many of the students. In some cases their incomprehension may have been feigned due to constraints on time or technical knowledge—some students were not able to assemble a corpus comprised of a prolific band’s lyrical discography or a writer’s oeuvre, let alone a representative sample of a musical or literary genre, and therefore claimed that they had chosen a random subset. A truly random subset is, of course, difficult to achieve and nearly impossible to verify, opening up the researcher to suspicion of selection bias. In these cases, I usually asked them to select a reproducible sample, such as singles or bestsellers, and modify their research questions accordingly. But in other cases students simply were not prepared, in a rushed context, to comprehend that a researcher could not draw valid conclusions about, for example, the difference between nineteenth and twentieth-century writing simply by comparing language differences between a few novels by Charles Dickens and John Buchan.

The students then tested their hypotheses through electronic text analysis. For most students, this analysis did not extend beyond comparisons of keyword frequency between and within their target and reference corpora. I was surprised to find that many of the students, all of whom were planning to major in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) disciplines, had difficulty with the concept of frequency; instead of statistical frequency, which is a rate, they would compare the absolute number of instances in one dataset to the absolute number of instances in another dataset even when these datasets were of unequal sizes. For some, the problem was solved by working in percentages instead of frequencies, but writing instructors should consider incorporating a primer on statistics when teaching quantitative analysis to humanities students or first-year STEM students.

The project was not entirely quantitative or objective—students often generated quantitative data based on qualitative premises and in any case they were to make highly subjective interpretations of their results. In one of the more successful studies, a student compared Sylvia Plath’s juvenilia, a set of poems written before Plath’s marriage to the poet Ted Hughes in 1956, to Ariel, the book of poems she wrote between her separation from Ted Hughes in 1962 and her suicide in 1963. Hypothesizing that Plath’s language would be darker in Ariel, the student used AntConc’s word list feature to identify words common to both datasets as well as those that had a high keyness, that is, those that were either unique or partial to one dataset. The student found that “negative” words such as dead or black were common in both datasets and surmised that Plath’s life must have been bleak ever since her father’s untimely death when the poet was just eight years of age. Yet the student unexpectedly discovered that “positive” words, such as white or love, tended to appear in negative contexts in Ariel but not in the juvenilia.

Such a qualitative judgment acquires an analytical foundation in the concept known as semantic prosody, which Adolphs defines as “the associations that arise from the collocates of a particular lexical item—if it tends to occur with a negative co-text then the item will have negative shading and if it tends to occur with a positive co-text than it will have positive shading.”29 A text-analysis tool like AntConc can generate, filter, and sort a list of collocates, which are words that appear within a given span (or word count) to the left and right of one or more instances of a user-defined keyword or phrase. These instances, when presented in a column flanked on each side by their respective co-text, or span of collocates, form a Key Word in Context (KWIC) concordance. In her book, Adolphs offers an extended example of how to perform electronic analysis of a literary text using this technique and the concept of semantic prosody.30 She begins by displaying a random sample from a KWIC concordance of the word happen in the spoken-word Cambridge and Nottingham Corpus of Discourse in English. She then observes that the word tends to be collocated with words that convey uncertainty or negativity, such as something or accident. She then moves to a KWIC concordance of the verbal phrase had happened from Virginia Woolf’s novel To The Lighthouse and shows that this form of happen has a strongly negative shading and occurs more often when the narrative reflects the mindset of Mrs. Ramsay rather than that of one of the more confident male characters.

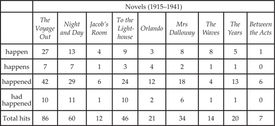

Following up on Adolphs’ example, one of my students expanded Adolph’s investigation of the verb happen to a corpus of all nine of Woolf’s novels, hypothesizing that instances would increase as the publishing history drew nearer to the date of her suicide in 1941. This hypothesis rests, of course, on the premise that the degree of negative and/or uncertain points of view in Woolf’s novels can serve as a barometer of the author’s own state of mind. The student found that instances of the four different tenses she examined actually decreased in Woolf’s last three novels (see Table 1). She then compared the collocates of the verb in Woolf’s novels to those in COHA, her reference corpus, using the time range 1910–1940, and found that Woolf’s are proportionally more likely to convey uncertainty as opposed to negative or positive events. The student cleverly concluded that if the decrease in the use of the verb means that Woolf was assuming greater control of her life, or becoming resigned to her fate, then a follow-up researcher should find that the collocates in her later novels express less uncertainty.

Table 1. Student’s table of four different tenses of the word happen. Not taken into account in this table is the relative length of these nine novels, the last three containing less than half as many words on average as the first three. This difference in word count, however, does not quite flatten out the trend suggested here.

Since the two student projects described above involved traditional humanities materials, a writing instructor who leans more toward cultural studies might find greater inspiration in a third project that tracked historical change in the collocates of the word marijuana and a few of its many and sundry synonyms. This student speculated that since the 1960s, attitudes toward the drug have become increasingly more positive. His study, though flawed, seemed to support this hypothesis, and could be taken as a first-year student’s version of an emerging form of scholarly inquiry that the authors of a 2010 Science article term culturomics, or the “quantitative analysis of culture.”31

After obtaining and interpreting their results, students proceeded to the final step in the assignment: writing up their research. Whereas the qualitative Sophie editions were accompanied by an analysis, in a standard essay format, of the rhetorical and mediatory aspects of the edited text, their quantitative visualizations called for a technical report format. This genre is rarely taught in high school science courses, let alone in English, so I prepared the students by showing them examples of college-level literature essays, lab reports, and social science papers. We discussed the general differences in content, writing style, and document design and came to the conclusion that a digital humanities report should probably be an amalgam divided into sections corresponding to each of these types in varying degrees. The format would consist of four sections: introduction, methods and results, discussion, and conclusion. While the first and last of these sections could be interpretive, the numerical data in the methods and results section had to be presented in as empirical a fashion as possible and the specifics of these results objectively analyzed in the discussion section. This procedure emulates some of the best practices of writing in STEM and social science disciplines. Digital humanities thus provides a rationale and opportunity for composition instructors to expose their students to aspects of technical writing processes alongside the argumentative and expository writing processes practiced in the discipline of English studies.

Although some students were unsettled by what they saw as the technical and open-ended nature of these assignments, most were pleasantly surprised to be learning, in an English class, how to conduct quantitative research and report on their findings. As a composition teacher and a digital humanist, I was surprised by how much time had to be devoted to preparing students for these projects yet pleased by the unexpected insights they gained, through editing and linguistic analysis, not only into matters of language and rhetoric but also into humanities content. As for Stanley Fish, he might be taken aback to discover that even first-year students are capable of using text mining to pursue a hypothesis, not merely to dig one up.

In the two years since I taught the course, the affinity between computers and writing and new media studies has grown. Increasingly, software and even search engines are seen as sites of “procedural” or “algorithmic” rhetorics.32 More akin to humanities computing is student tagging of digitized primary materials, such as those in the Library of Congress Flickr Pilot Project.33 Text analysis, meanwhile, is appearing more frequently on lesson plans.34 Although rhetoric and composition scholars are beginning to receive NEH digital humanities start-up grants, most of their proposals describe archiving or publishing projects that seem to fall within familiar humanities computing territory.35 The 2012 grant guidelines, however, call for “scholarship that focuses on the history, criticism, and philosophy of digital culture and its impact on society.”36 This change is promising for both computers and writing and new media studies, but until that glorious day when the word pedagogy appears in the guidelines, college teachers should advocate that at least some of the projects benefit students, even those in a first-year writing course.

Footnotes

1 Stanley Fish, Save the World on Your Own Time (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 44, 46.

2 John L. Schlib, “Turning Composition toward Sovereignty,” and Arabella Lyon, “Composition and the Preservation of Rhetorical Traditions in a Global Context” (papers presented at the MLA Annual Convention, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, December 29, 2009).

3 Multimodal Literacies Issue Management Team of the NCTE Executive Committee, “Position Statement on Multimodal Literacies,” National Council of Teachers of English (approved November, 2005), http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/multimodalliteracies.

4 Council of Writing Program Administrators, “WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition” (adopted April, 2000; amended July, 2008), http://wpacouncil.org/positions/outcomes.html.

5 Jeff Rice, The Rhetoric of Cool: Composition Studies and New Media (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007), 17.

6 Todd Presner and Jeffrey Schnapp et al., “Digital Humanities Manifesto 2.0,” University of California, Los Angeles, May 29, 2009, http://manifesto.humanities.ucla.edu/2009/05/29/the-digital-humanities-manifesto-20/.

7 N. Katherine Hayles, How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 24–27.

8 Patrik Svensson, “Humanities Computing as Digital Humanities,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 3, no. 3 (2009): paras. 1–62, http://digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/3/3/000065/000065.html

9 Gail E. Hawisher, Paul LeBlanc, Charles Moran, and Cynthia L. Selfe, Computers and the Teaching of Writing in American Higher Education, 1979–1994: A History (Norwood: Ablex, 1996).

10 See for example Cynthia L. Selfe, “Technology and Literacy: A Story about the Perils of Not Paying Attention,” College Composition and Communication 50, no. 3 (1999): 411–36; Anne Frances Wysocki and Johndan Johnson-Eilola, “Blinded by the Letter: Why Are We Using Literacy as a Metaphor for Everything Else?” in Passions, Pedagogies, and 21st Century Technologies, ed. Gail E. Hawisher and Cynthia L. Selfe (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1999), 349–68; see also New London Group, “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures,” Harvard Educational Review 66, no. 1 (1996): 60–92. The New London Group coined the term “multiliteracies” to describe a pedagogical response to a changing, globalized communication landscape where literacies of sound, image, and electronic textuality would become equally important, if not more so, than traditional print and oral literacies.

11 Colin Gifford Brooke, Lingua Fracta: Toward a Rhetoric of New Media (Cresskill: Hampton Press, 2009).

12 Jeff Rice, “Writing about Cool: Teaching Hypertext as Juxtaposition,” Computers and Composition 20 (2003): 221–36.

13 Olin Bjork and John Pedro Schwartz, “What Composition Can Learn from the Digital Humanities” (paper presented at the MLA Annual Convention, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, December 29, 2009).

14 N. Katherine Hayles, My Mother Was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts (Chicago: University of Chicago press, 2005), 91.

15 Svensson, “Humanities Computing as Digital Humanities,” paras. 46, 51.

16 Gaitán’s book, along with other examples of Sophie in action, are available for download from the “Demo Books” section of the Institute for the Future of the Book website, http://www.futureofthebook.org/sophie/download/demo_books/.

17 For Fitzpatrick’s 2010 course syllabus, see http://machines.pomona.edu/51-2010/; for the Sophie assignment, see http://machines.pomona.edu/51-2010/04/02/project-4-sophie/.

18 This distinction between “distant” and “close” reading first appears in Franco Moretti, “Conjectures on World Literature,” New Left Review 1 (2000): 54–68.

19 For a discussion of teaching text analysis in the humanities classroom, see Stéfan Sinclair and Geoffrey Rockwell’s chapter, “Teaching Computer-Assisted Text Analysis: Approaches to Learning New Methodologies.”

20 Jim Ridolfo and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss, “Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery,” Kairos 13, no. 2 (2009), http://www.technorhetoric.net/13.2/topoi/ridolfo_devoss/.

21 Julie Meloni, “Wordles, or The Gateway Drug to Textual Analysis,” ProfHacker, The Chronicle of Higher Education, October 21, 2009, http://chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/wordles-or-the-gateway-drug-to-textual-analysis/.

22 At the 2012 Computers and Writing conference in Raleigh, North Carolina, a group from the University of Michigan gave an AntConc workshop titled “Using Corpus Linguistics to Assess Student Writing.” For an example of a study using AntConc to research a corpus of student text, see Ute Römer and Stefanie Wulff, “Applying Corpus Methods to Writing Research: Explorations of MICUSP,” Journal of Writing Research 2, no. 2 (2010): 99–127.

23 Fish, Save the World on Your Own Time, 41–49; see also Stanley Fish, How to Write a Sentence and How to Read One (New York: Harper, 2011).

24 Scott Jaschik, “What Direction for Rhet-Comp?” Inside Higher Ed, December 30, 2009.

25 Cheryl Ball, Douglas Eyman, Julie Klein, Alex Reid, Virginia Kuhn, Jentery Sayers, and N. Katherine Hayles, “Are You a Digital Humanist?” (Town Hall session of the 2011 Computers & Writing Conference in Ann Arbor, Michigan, May 21, 2011), http://vimeo.com/24388021.

26 Stanley Fish, “The Digital Humanities and the Transcending of Morality,” Opinionator, New York Times, January 9, 2012, http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/09/the-digital-humanities-and-the-transcending-of-mortality.

27 Stanley Fish, “Mind Your P’s and B’s: The Digital Humanities and Interpretation,” Opinionator, New York Times, January 23, 2012, http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/01/23/mind-your-ps-and-bs-the-digital-humanities-and-interpretation.

28 Svenja Adolphs, Introducing Electronic Text Analysis: A Practical Guide for Language and Literary Studies (New York: Routledge, 2006).

29 Ibid., 139.

30 Ibid., 69-73.

31 Google Books Team et al., “Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books,” Science 331, no. 6014 (2011): 176–82.

32 “Procedural rhetoric” is the title of the first chapter of Ian Bogost’s Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007), a new media studies book that helped inspire a software studies movement in computers and writing. John M. Jones gave a paper on “Algorithmic Rhetoric and Search Literacy” at the 2011 Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Advanced Collaboratory Conference in Ann Arbor (Michigan, December 13, 2011)—his slides and notes are available at http://www.slideshare.net/johnmjones/algorithmic-rhetoric-and-search-literacy-hastac2011.

33 See Matthew W. Wilson, Curtis Hisayasu, Jentery Sayers, and J. James Bono, “Standards in the Making: Composing with Metadata in Mind,” in The New Work of Composing, ed., Debra Journet, Cheryl E. Ball, and Ryan Trauman (Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press, in press), http://ccdigitalpress.org/; see also “Library of Congress Flickr pilot project,” http://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/collections/.

34 For an example of an assignment using the Voyeur text analysis tools, see Michael Widner, “Essay Revision with Automated Textual Analysis,” Digital Writing and Research Lab’s Lesson Plans, http://lessonplans.dwrl.utexas.edu/content/essay-revision-automated-textual-analysis.

35 See, for example, Cheryl E. Ball, “Building a Better Back-End: Editor, Author, & Reader Tools for Scholarly Multimedia,” https://securegrants.neh.gov/PublicQuery/main.aspx?g=1&gn=HD-51088-10; Shannon Carter, “Remixing Rural Texas: Local Texts, Global Context,” https://securegrants.neh.gov/PublicQuery/main.aspx?g=1&gn=HD-51398-11.

36 NEH Office of Digital Humanities, “Digital Humanities Start-Up Grants,” http://www.neh.gov/grants/odh/digital-humanities-start-grants/.